The weekend of Saturday 12th September saw La Liga football return once again. On Sunday, it was the turn of Valencia to begin their 2020/21 campaign with a match against local rivals Levante at Estadio de Mestalla. Los murcelagos struggled last season, finishing outside the top four for the first time in three seasons as they scrambled to ninth. Levante on the other hand finished in an impressive 12th position – their highest finish since returning to La Liga in 2017.

Valencia supporters felt alienated by owner Peter Lim in the offseason, with his brutal handling of the club. They sold Ferran Torres to Manchester City, Francis Coquelin to Villareal, and Rodrigo to Premier League new boys Leeds, and heading into their season opener, had opted not to sign any replacements. Levante, on the other hand, made a few small signings to enhance squad depth, and with no departures, fans will be hoping head coach Paco López can lead his team to a top-half finish this season. This tactical analysis will explore how both teams approached what was, for the most part, a close game, and ultimately provide an analysis as to how Valencia managed to secure a victory.

Lineups

Javi Gracia opted for a 4-4-2 formation, in which he gave a debut to 17-year-old English winger Yunus Musah, with Gonçalo Guedes occupying the other wing. Maxi Gómez, who was Valencia’s top scorer last season, led the line with Lee Kang-In. Geoffrey Kondogbia partnered Vicente Esquerdo in the middle. Their back four was Daniel Wass, Gabriel Paulista, Eliaquim Mangala, and José Gayà.

Levante also started with a 4-4-2. Jorge Miramón and Carlos Clerc occupied the full-back positions, with Óscar Duarte and Róber Pier as centre-backs. Nemanja Radoja partnered José Campaña in the centre of midfield, and Gonzalo Melero and Enis Bardhi started out wide. José Morales and Sergio León started up front.

Valencia (4-4-2): Domenech; Wass, Gabriel, Mangala, Gayà; Musah, Esquerdo, Kondogbia, Guedes; Gómez, Lee

Levante (4-4-2): Fernandez; Miramón, Duarte, Pier, Clerc; Campaña, Radoja, Melero, Bardhi, Leon, Morales

Early Levante press

It was clear that López didn’t want his opponents to settle, ordering his men to press high from the outset. Their PPDA of 9.5 for the game exemplifies this desire, but López will have been especially pleased with the start Levante made. Following a high press from the centre, Levante won possession back and scored inside 40 seconds.

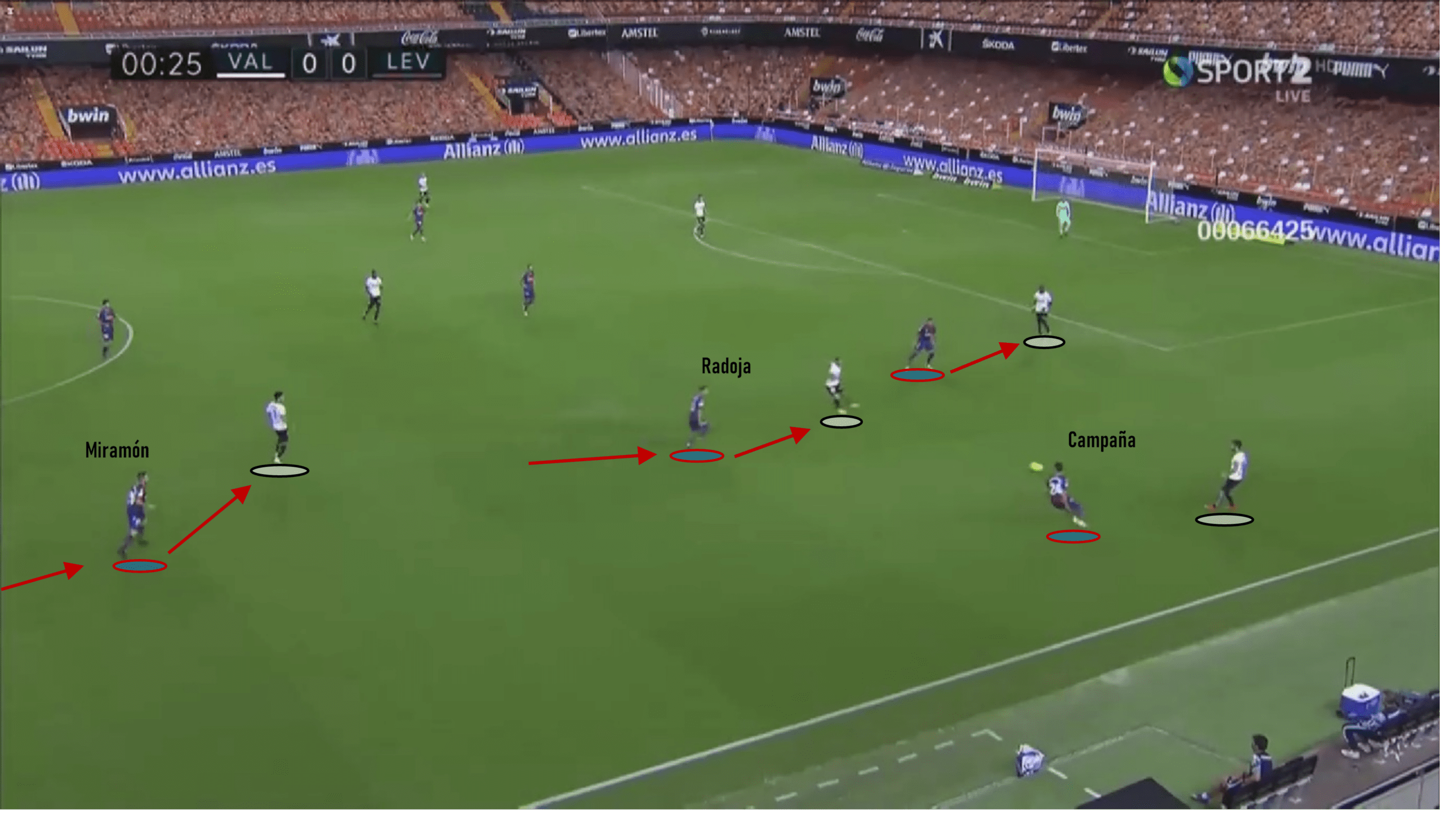

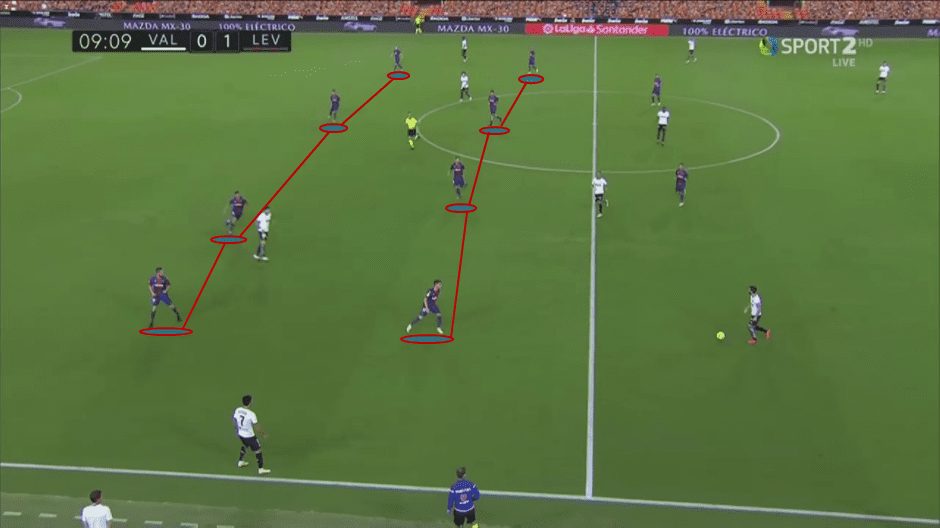

After the ball went back to Gayà, Campaña came high and wide in order to pin him back. From here, we can see below that León pushed higher than the attacking line to prevent the ball from going to the centre-back. This triggered Radoja to come in from midfield to shut down Esquerdo. The ball went to Esquerdo but Radoja was too close to him. Radoja, therefore, won back possession which released Morales who, after some fancy footwork, tucked the ball away to reward Levante for their high-energy start.

Note also in the still above how Miramón reacted to Radoja’s high press. He stepped into midfield to shut down the man Radoja just left, giving even fewer options to the man on the ball for Valencia. This high pressing tactic is tiresome but effective. One drawback is it does involve players often leaving their positional base in order to intensely close the man on the ball and his options. However, in an attacking sense, it worked well for Levante with 53.3% of their 75 recoveries occurring in a medium or high area of the pitch.

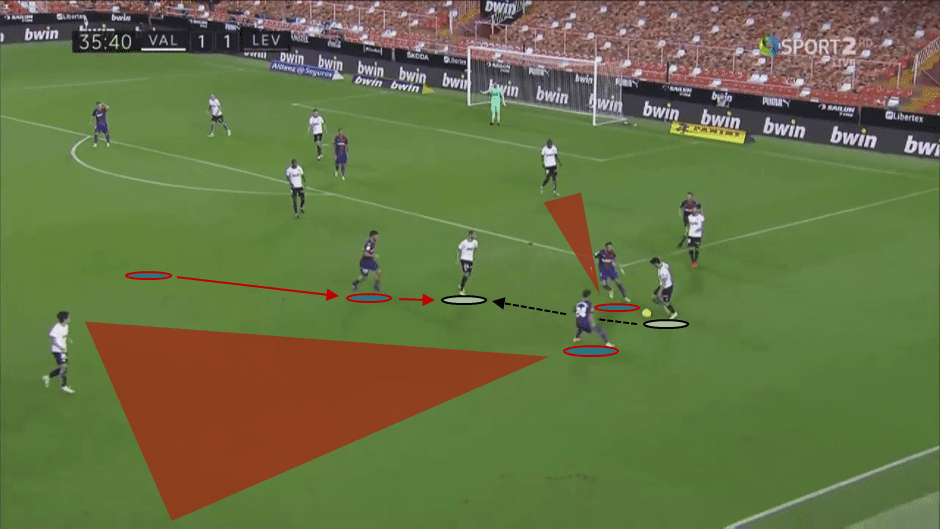

Levante’s second goal arose from a counter-press in a similar area. Instead of retreating after losing possession, the Levante players sought to win the ball back before Valencia settled. We can see below the crowding of Guedes by Campaña and Morales. The press was clever, as the two men shut off all passing angles besides one – in which the receiver was closed by Melero. Melero again had left his positional base in order to execute the press, but after he won the ball back, he shifted it to Morales who did the rest. While vacating your position can be dangerous, an orderly press like Levante’s (40% of their recoveries came from positional pressing) can bring numerous benefits, which they realised as they went 2-1 up.

Valencia struggle for possession

Gracia’s men only managed 44% possession in the match and found it difficult to retain the ball throughout. While Levante’s high press was a factor in this, a lot of the issues can be attributed to the poor movement of Valencia’s central midfielders. In a 4-4-2 system, it is pivotal that the men in the centre remain fluid and available for the ball so as to build up effectively.

This is especially crucial when your wingers often take up high starting positions too. As a result, Valencia struggled to play through the lines. 16% of their passes were long, whereas it was just 4% for Levante. They also only had an 81% pass accuracy and a disappointing 62% of their possessions lasted under 10 seconds.

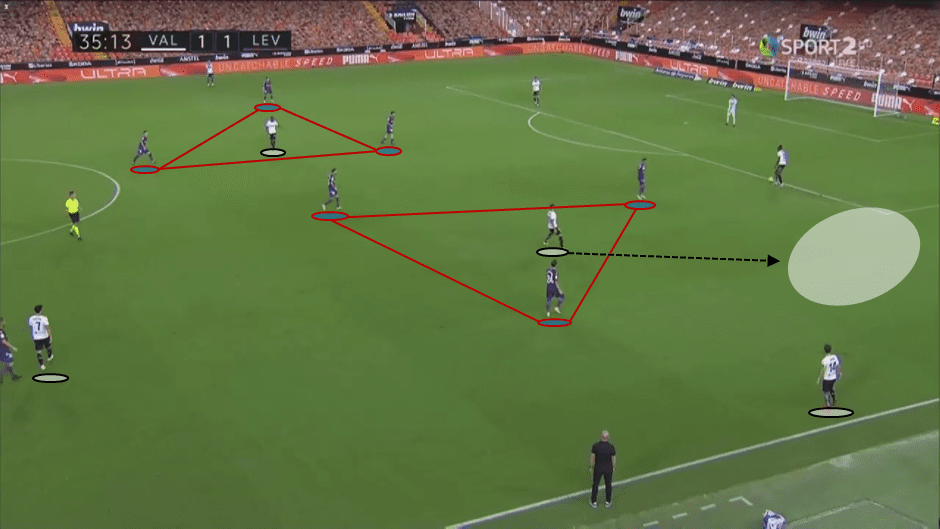

The still below shows Valencia attempting to build-up play with substitute Mouctar Diakhaby in possession. Kondogbia and Esquerdo are placed in-between two triangles of Levante players. While this is a good positional press from Levante, the laziness of Valencia’s midfield duo prevents them from keeping possession in an assured manner. Both men are directly behind an opposition player and therefore offering no option to Diakhaby. One solution could involve Esquerdo dropping into a deeper, left-back position as highlighted. This would drag Levante players out of the central area and allow either Guedes some space to come deep and receive or Gayà to push on down the wing. Instead, Diakhaby hit a long pass that went out for a throw.

Valencia found themselves in a similar position in the still below. Despite leading at the time, the game was far from over and Valencia should have been doing all they could to get a fourth. This time, the duo was Kondogbia and Uroš Račić, but the result was very much the same.

Both men found themselves somewhat splitting the diagonal line joining two Levante players. Not only were they invisible to the man in possession, but they had someone behind them ready to engage should the receive the ball also. Kondogbia did look to shift to the right to give an option, but was telegraphed by the Levante striker.

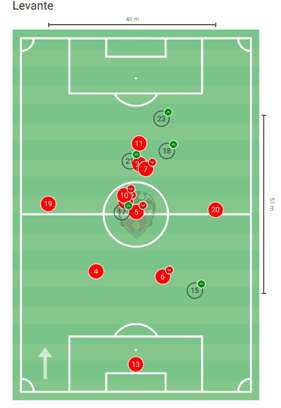

As this problem repeated itself throughout the match, what became obvious was Valencia’s need for a midfielder who is able to sit deeper, between the centre-backs, and keep things ticking over. To facilitate this, a switch to a 4-3-3 would have been hugely beneficial. Instead, Valencia’s midfield pair received just 44 of 276 accurate passes. Valencia have more than enough attacking quality, so can afford an extra man in the middle. While the sitter would have a lot of the ball, it would allow the other two centre-midfielders to pull into the half-spaces in order to receive the ball and turn. This would’ve been a potent response to Levante’s rigid 4-4-2, but instead, Valencia struggled to keep the ball throughout, and they allowed Levante to defend as narrow as they did – their average position map from the match is shown below.

Levante’s defensive setup

Aside from the press, it was clear that Levante wanted to condense the pitch and squeeze the play. They employed a very high defensive line to try and crowd Valencia out and win the ball back quickly. Having already touched upon Levante’s high press and Valencia’s lack of space in the middle, an analysis of the Levante ‘squeeze’ will display how both of the two prior points occurred.

In the still below, Levante’s 4-4-2 is obvious. Interestingly, despite the Valencia ball carrier being by the halfway line, all Levante players are behind the ball. When the height of the defence is considered also, we can understand why Valencia struggled for possession in the central areas, and ended up with 16% of their passes being long. They were often forced to look long and in-behind, but Levante had two centre-backs who believed in their pace. It is, again, a risky tactic. While it can result in the recovery of possession in a dangerous area, you also leave a lot of space behind the defenders which can be exposed by a good progressive pass or run.

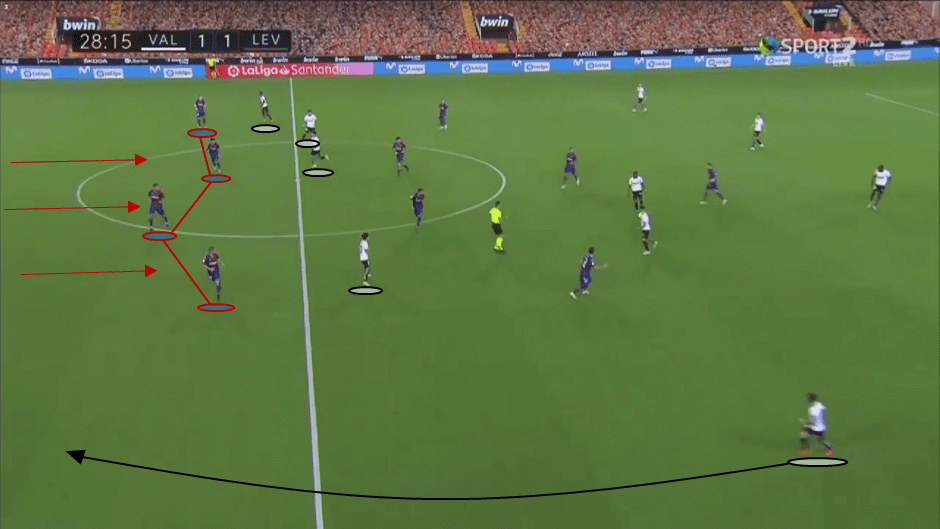

Levante’s defenders were keen to stick to this tactic religiously. Even if, as shown below, the forward players were out of position following a failed recovery attempt, the back four would still remain high and horizontal. The still below presented a far more dangerous situation than the one above. Both wingers had tucked in to support the press, leaving the defence unprotected and exposed (note the four Valencia players behind the Levante midfield).

But instead of deciding to acknowledge the danger and drop, Levante’s defence remained high. Note the space ahead of Gayà at the bottom of the picture which was left by Campaña who joined the press. In the frame above, Campaña is deep and wide, nullifying such threat, whereas the still below really exposes the dangers of a high press and high line.

Startlingly, if Valencia did manage to successfully negate the high line and force Levante back, Levante would begin to lose all sense of defensive structure. Considering the immense desire to stick to their high line, it was surprising to see such a lack of defensive planning in the final third. Instead of retaining a shape – like the high line – they all would crowd the man in possession, disregarding any sense of positional responsibility and somewhat ignoring any opposition runners.

The still below displays Gayà driving forward with the ball and Guedes outside of him. Immediately, four Levante players stormed around him in an attempt to shut him down. While this tactic could overwhelm a technically inept footballer, Gayà could simply remain calm and slot the ball through to Guedes who could deliver a cross. By trying to make life harder for the man on the ball in the final third, Levante often made the job of those not on the ball far easier. Four men are not required to shut down one player, so either Campaña or Miramón could’ve simply tracked Guedes and prevented him receiving the ball. Ultimately though, Levante’s defensive fallibilities would be their downfall.

Valencia exploit the press

Valencia’s second-half attacking display was far more inspiring than their first. Gracia had noticed the means by which Levante approached the game and managed to adapt his team accordingly. One notable change was the increased license he gave Gayà to attack. If Gayà took up a more advanced position early in the build-up, the Levante right-winger would be left with a dilemma: he could track Gayà, therefore abandoning the group press; or he could allow Gayà to run free in order to preserve the pressing shape.

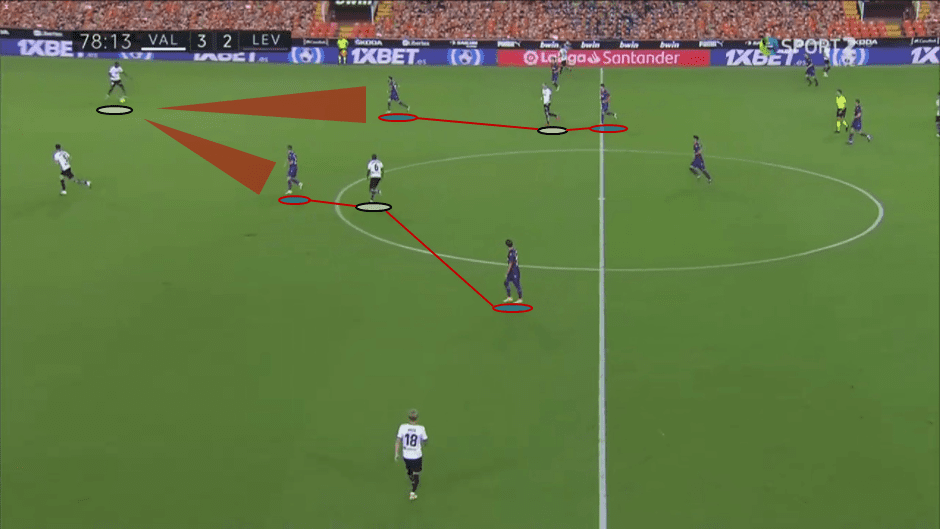

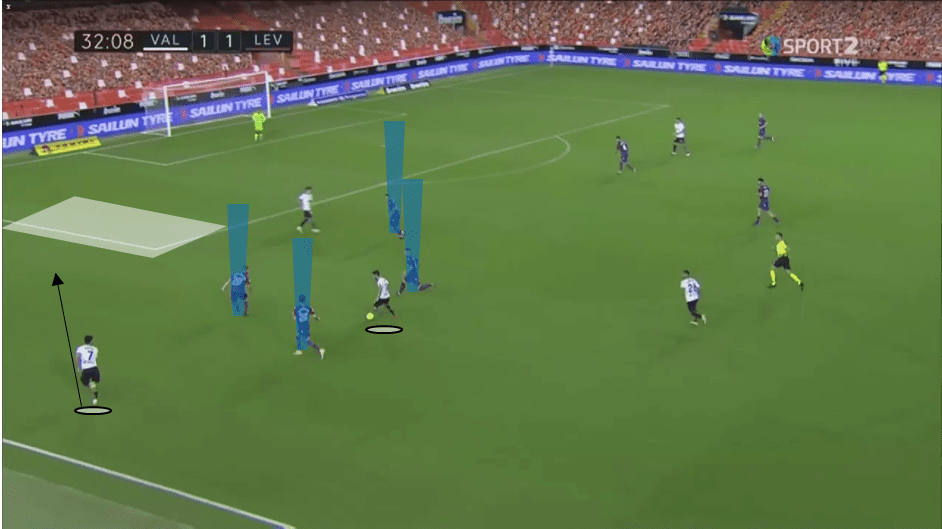

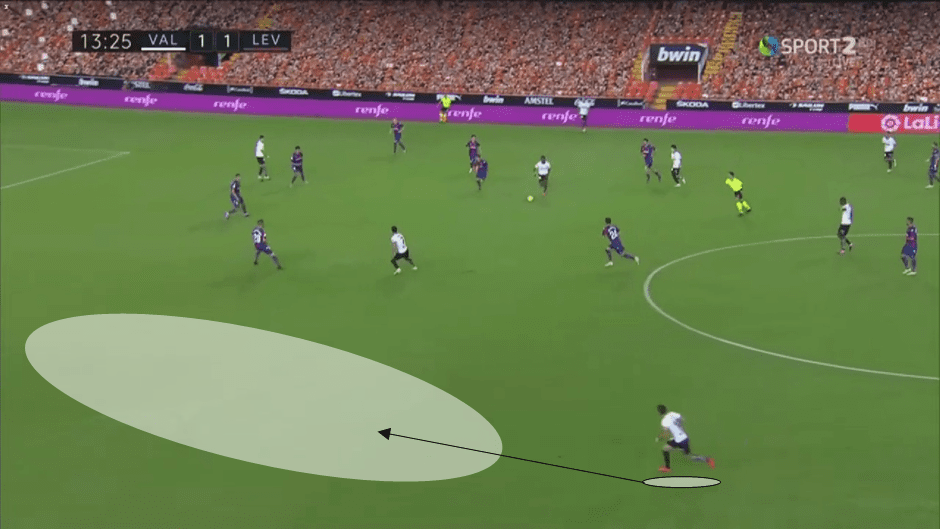

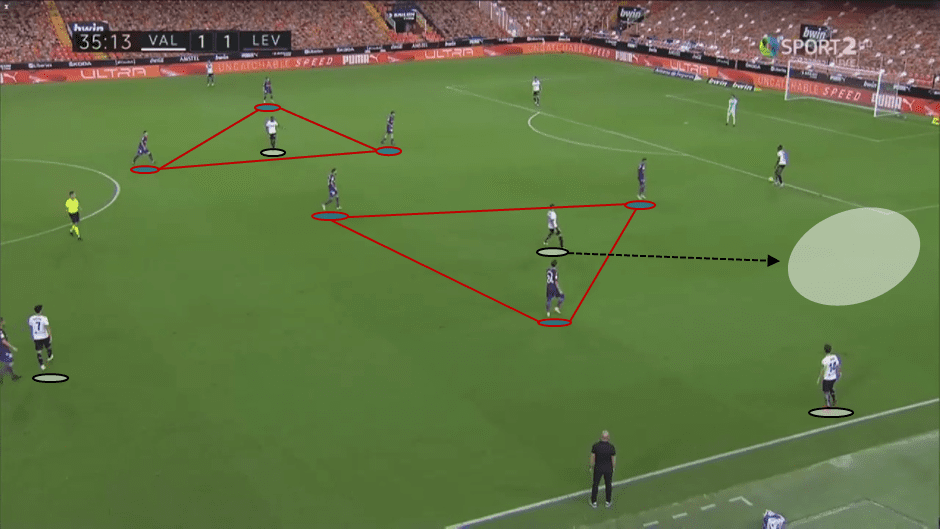

In the end, this resulted in Gayà being much more of an attacking threat than in the first half. He frequently found himself in wide space which he could freely attack due to Levante’s high, narrow defensive line. The space awarded to him is shown below. While the picture is from the first half, this occurred far more in the second.

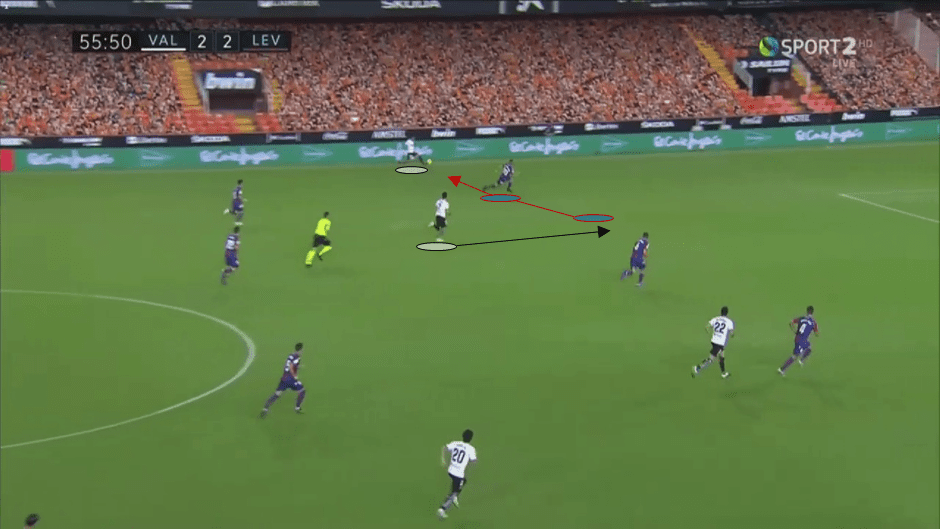

By getting higher, Gayà, who made the most progressive passes for Valencia (6), could also more effectively link up with the left-winger to create chances. With height and width, Gayà was often left open by Levante’s defenders, especially if he was on the blind side. A quick switch to Gayà would result in the right-back scrambling to get wide and close him down. What this allowed was the left-winger (in the case below, Guedes) to make his run in-between the right-back and centre-back in-behind. The still below displays this about to happen.

Again, as Gayà began high, the opposition winger ignored in favour of the press, which in turn created an overload for Valencia. They got a lot of joy down the left-hand side in the second half as a result of this. Valencia averaged 0.42 attacks per minute in the second half compared to 0.28 in the first.

Valencia exploit the high line

The above was an example of Valencia adapting to exploit the chaotic press of Levante, but they also directly managed to exploit their high line too. With an awareness that they weren’t keeping possession efficiently enough in the centre of the pitch, Gracia instructed his men in the second half to look for switches of play and long balls in behind the defence. As a result of these changes, Valencia accrued an xG of 1.75 in the second half compared to 0.32 in the first.

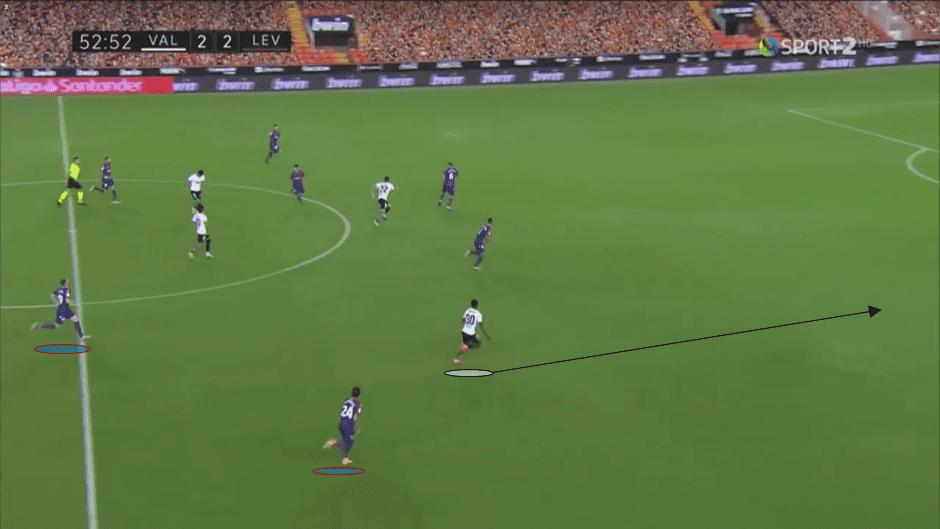

With left-back Clerc way out of position in the centre of the field, and Campaña scrambling back, the still below displays the space Musah was able to attack frequently in the second half of the game. Guedes comfortably put the youngster through on goal, one of their 8 through balls in the game, and he unluckily hit the crossbar. This was early in the second half however and a display of the weaknesses of Levante’s defensive setup. Perhaps the players weren’t fit enough to execute such an intense game plan for 90 minutes, but López’s failure to address the defensive frailties (bearing in mind they blew two leads in the first half alone) was what brought Levante down.

Valencia took the lead on 75 minutes after some shoddy defending both out wide, allowing a cross, and in the box, allowing an easy shot. Levante didn’t manage to get going again, and in stoppage time Valencia took advantage of Levante’s poor defensive display one final time.

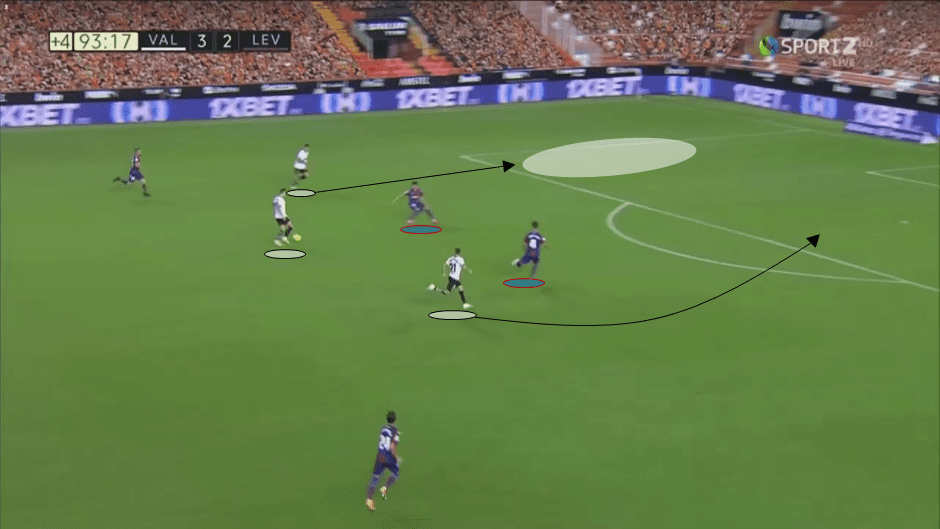

After substitute Denis Cheryshev intercepted a sloppy pass in midfield, he drove forward with two men in support. Despite the retreats of Levante’s outnumbered defenders, the Russian international easily shifted the ball to the left to Gómez, whose shot rebounded off the post to an unmarked Manu Vallejo. It was another example of the tired and lazy defending that characterised the football match, and it led to Valencia ending up as 4-2 winners.

Final remarks

This analysis showed that in a game dominated by damning defensive displays, Valencia’s pace and quality going forward was too much for Levante. Owing to the erroneous defensive performances, it would always be a case of who could outscore who. Despite an impressive showing from Morales, Levante didn’t possess enough attacking quality to put the game to bed while on top.

Credit must be given to Javi Gracia however, who altered his team’s tactics at half time and was able to exploit a Levante side who had no answers. While there is still a lot to work on for Valencia, four goals and a victory puts them top of La Liga. Levante, on the other hand, will need to drastically improve if they want to build on last season’s 12th place finish.

Comments