After a narrow win against Alavés in their opening match, Manuel Pellegrini’s Real Betis played Real Madrid as their second La Liga fixture. On the other hand, Zinedine Zidane’s side travelled to Benito Villamarín on Saturday looking to get their first domestic win of the season, after playing a goalless draw against Real Sociedad in their season opener.

Although the tie saw a red card an own goal and a match-deciding penalty, there were certain tactical patterns that helped Real Madrid overcome Betis in their home. In this tactical analysis, we’ll look the line-ups, how Real Madrid’s dynamic backline shaped their build-up, and how Betis’ build-up tactics looked like compared to their rival’s. This analysis will also look at how Betis’ press varied with Real Madrid’s dynamic approach at the back.

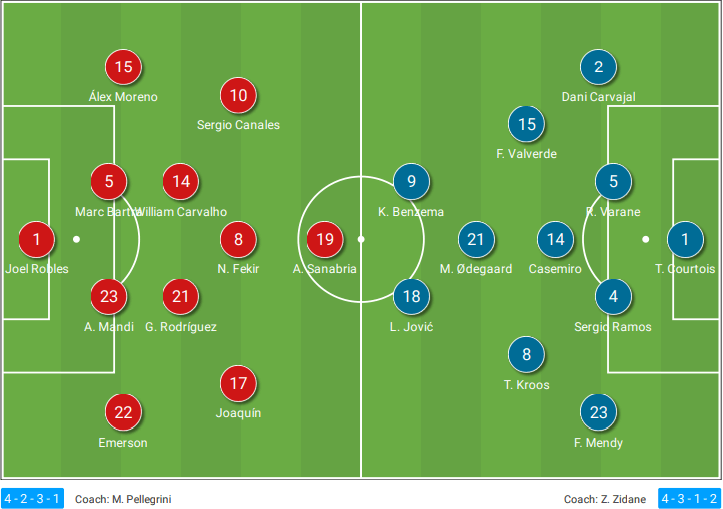

Line-ups

Real Betis went with their signature 4-2-3-1, with Nabil Fekir starting as a number ten behind Antonio Sanabria. Joaquín started from the right in an advanced midfield of three, whereas Guido Rodríguez and William Carvalho started as the double pivot ahead of the back four.

For Real Madrid, the 4-3-1-2 formation accommodated Luka Jović and Karim Benzema playing in front of Martin Ødegaard. Toni Kroos, Fede Valverde and Casemiro formed the midfield three ahead of Madrid’s defensive line.

Madrid’s dynamic shape in build-up and the width

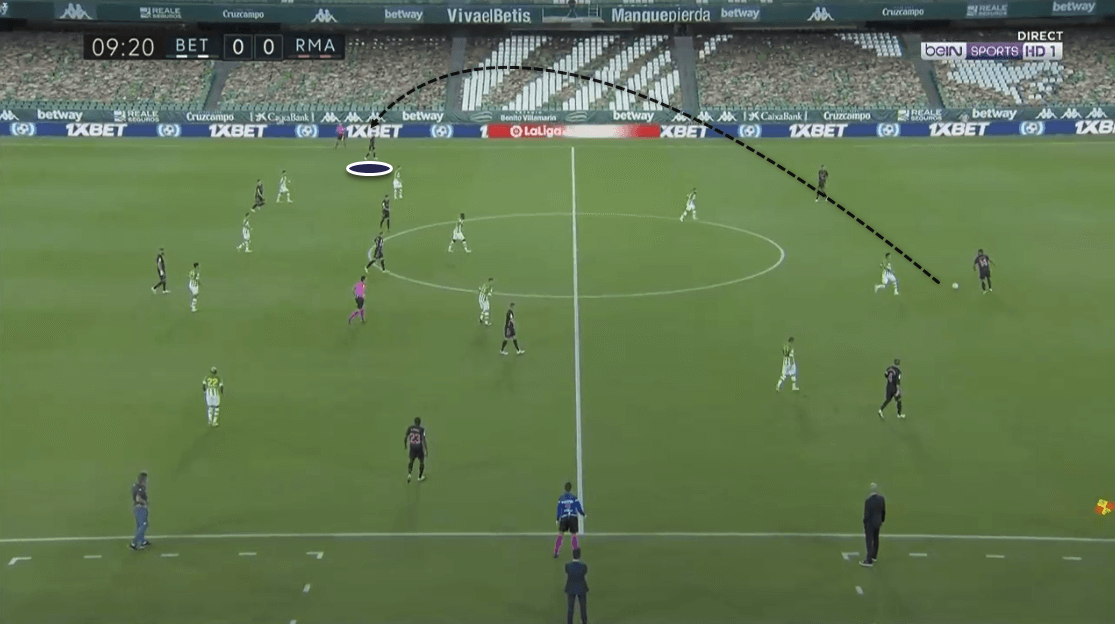

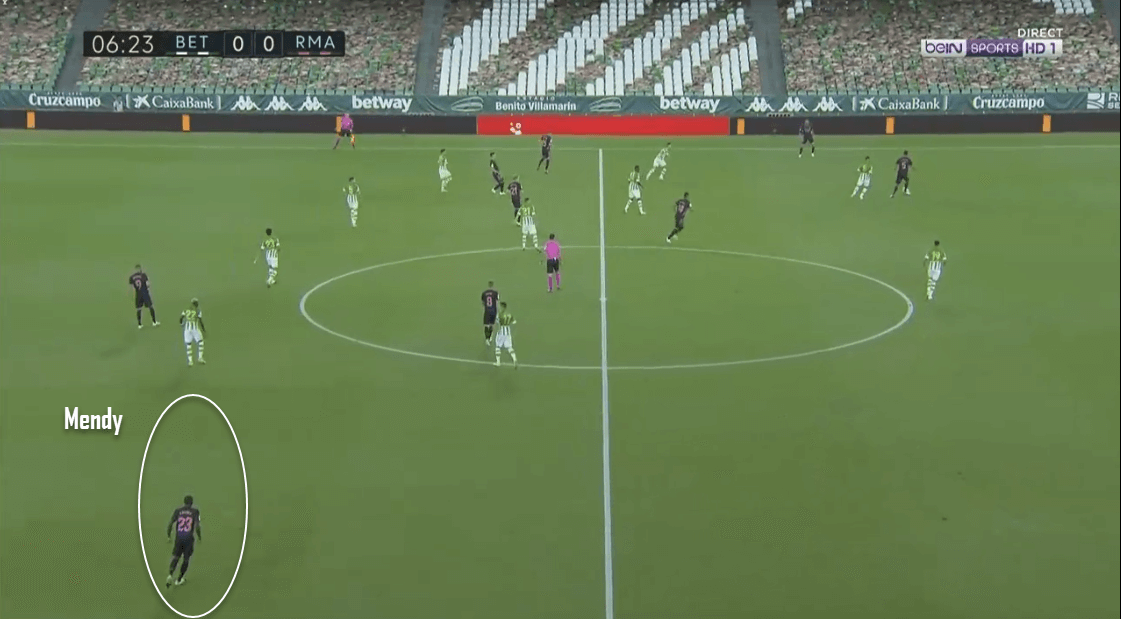

Real Madrid regularly pushed their full-backs higher up the pitch and made use of both Kroos (deep-lying playmaker) and Casemiro (defensive playmaker) to complete their backline on possession. Both the players were used to either cover the wide space or to tug inside the centre-backs to create a back three. All these movements were done to cover spaces and create an extra passing option in the build-up.

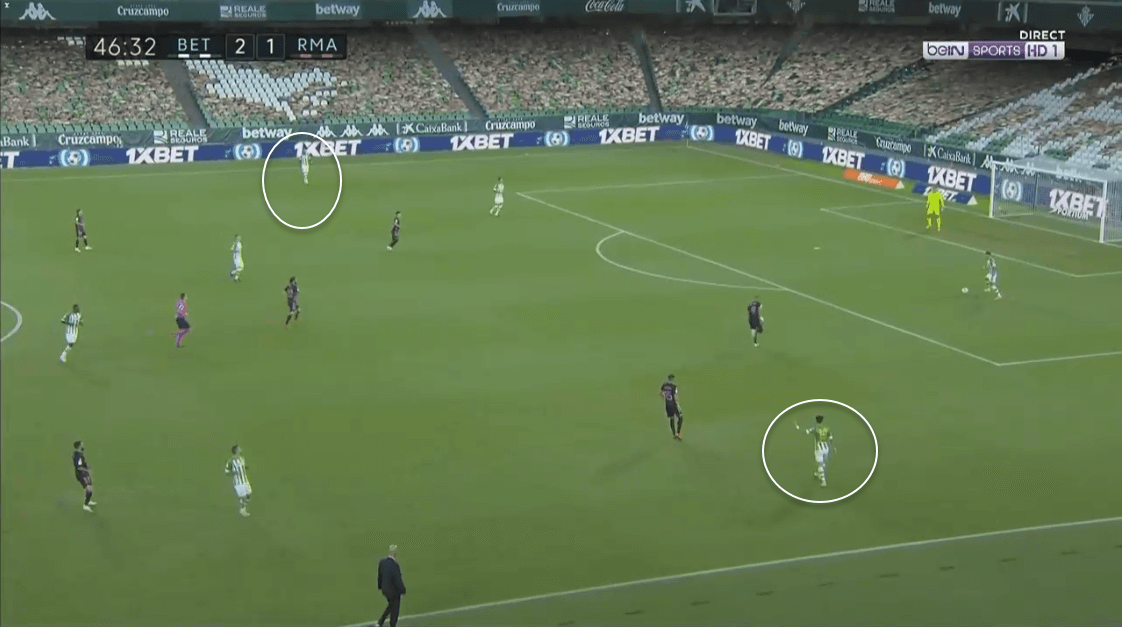

Like we can see here, Casemiro comes in between Raphaël Varane and Sergio Ramos to form a back three. Real Madrid used this scheme to build-up with long balls, usually targeting the wider side. As a result, the fullbacks were in the receiving end for most occasions, like what followed the sequence:

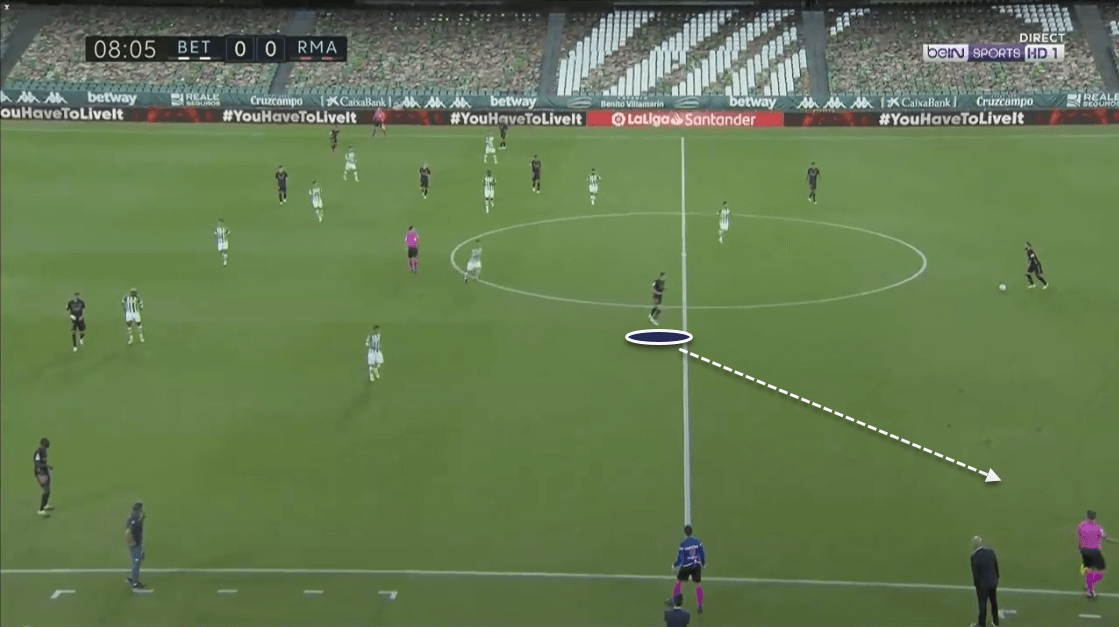

Similarly, the deep-lying playmaker, Kroos was involved in bringing the ball out from the back in a different manner. Kroos usually occupied the left side, helping the two centre-backs when Casemiro was in a relatively advanced position. In build-up, this helped a lot, as Kroos was able to both carry the ball ahead or direct a pass towards Ødegaard or Valverde.

In this instance, Mendy is allowed to always remain ahead and receive balls to make wide runs. In the build-up, this liberty to Mendy meant Benzema and Jović were offered a more central role, usually within the opposition area. Since a similar trait was given to Dani Carvajal, the right-back, the right side also was properly occupied.

Kroos’ role in these situations was to come deep and fetch balls, in order to find passing options, or drive forward all on his own. Like in the instance below, where Kroos turns and creates a free pass receiver, Ramos.

Also, what we can notice is Kroos has made two opposition players commit to him, releasing Ramos to receive and move forward in space.

Since we’ve already taken a look at how full-backs were pushed higher and how the midfield and back functioned in the build-up, now let’s look at how things worked for the Blancos as they moved forward.

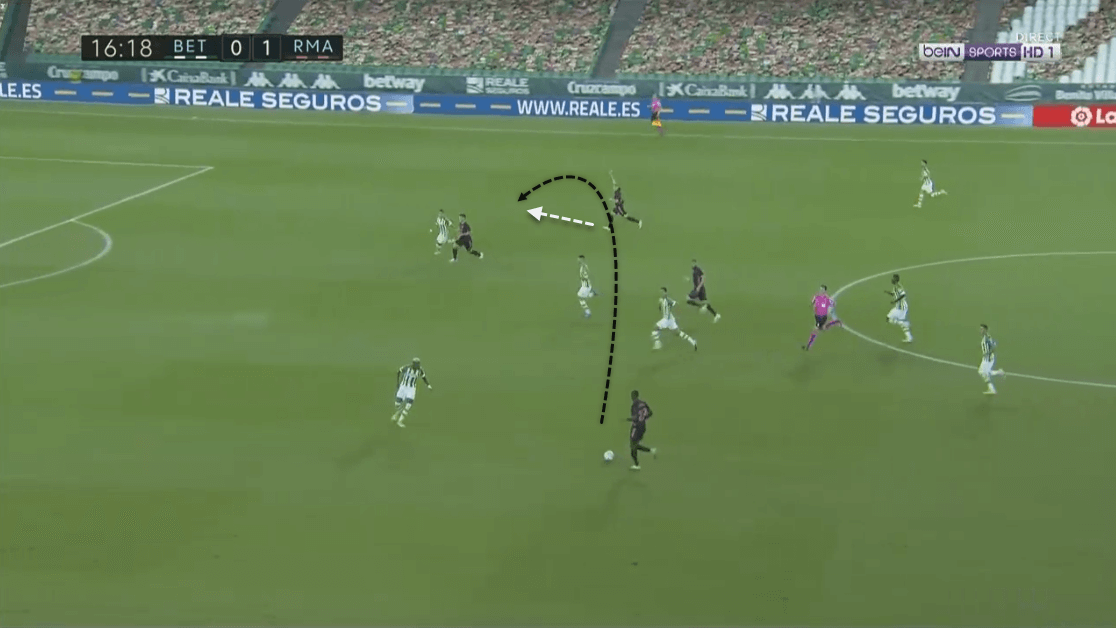

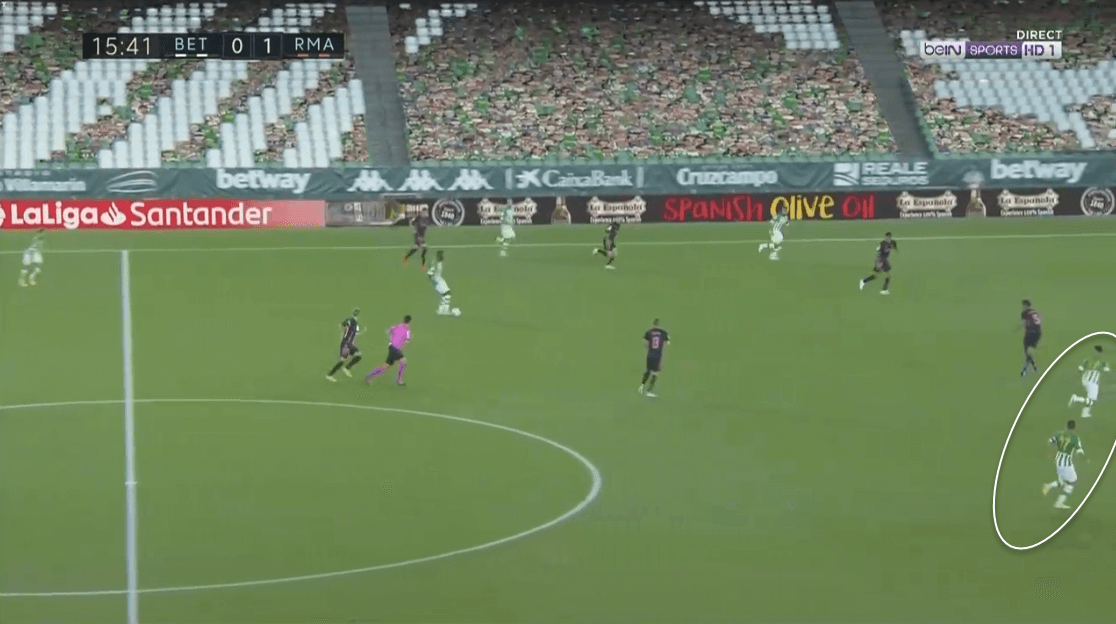

Ferland Mendy was allowed to make runs and cross; however, Real Madrid made use of diagonal balls to stretch the opposition and find alternatives to attack. In this case, the exchange of long passes between the two full-backs was apparent.

Like an instance from the 16th minute, when Mendy makes run but spots the movement on the other flank, hence using the slight bit of extra space that is available to the run-making player. Movement and patterns like these were visible throughout Madrid’s attacking moves.

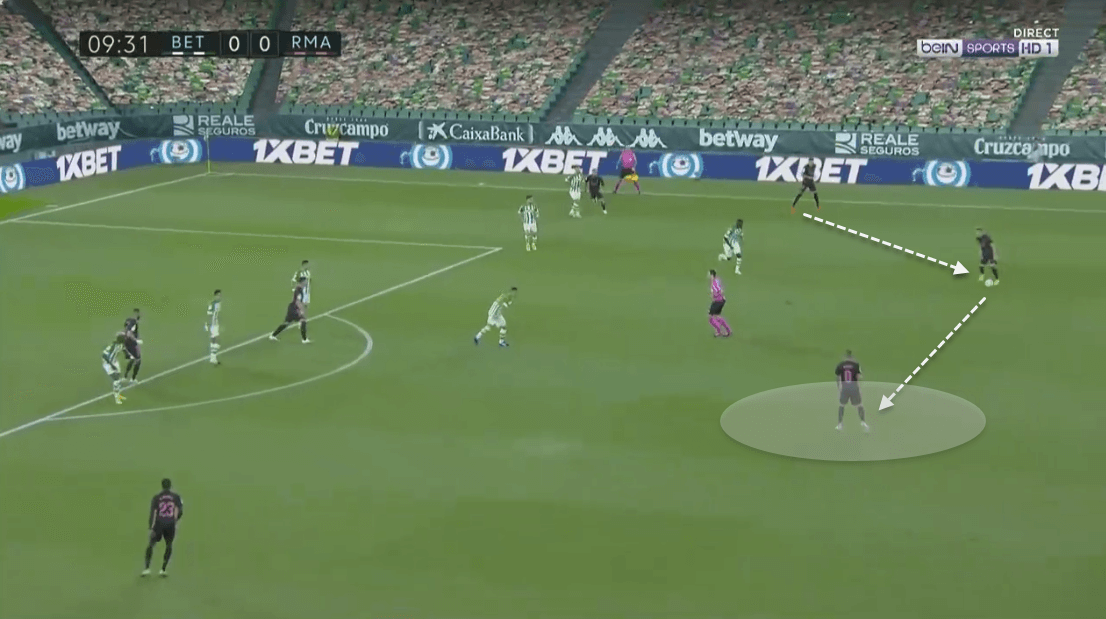

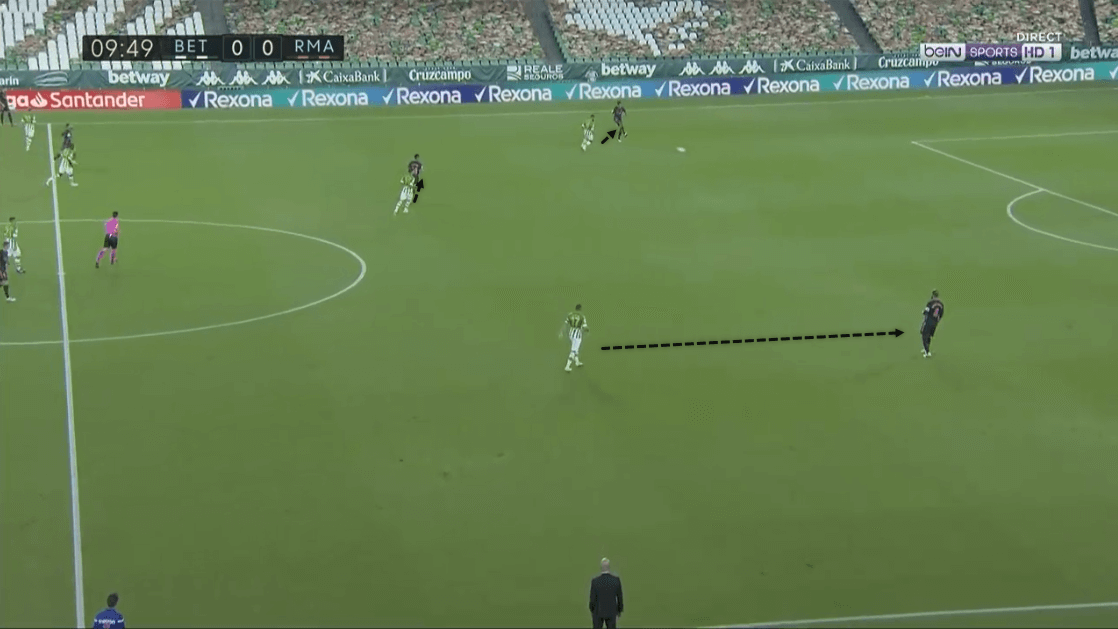

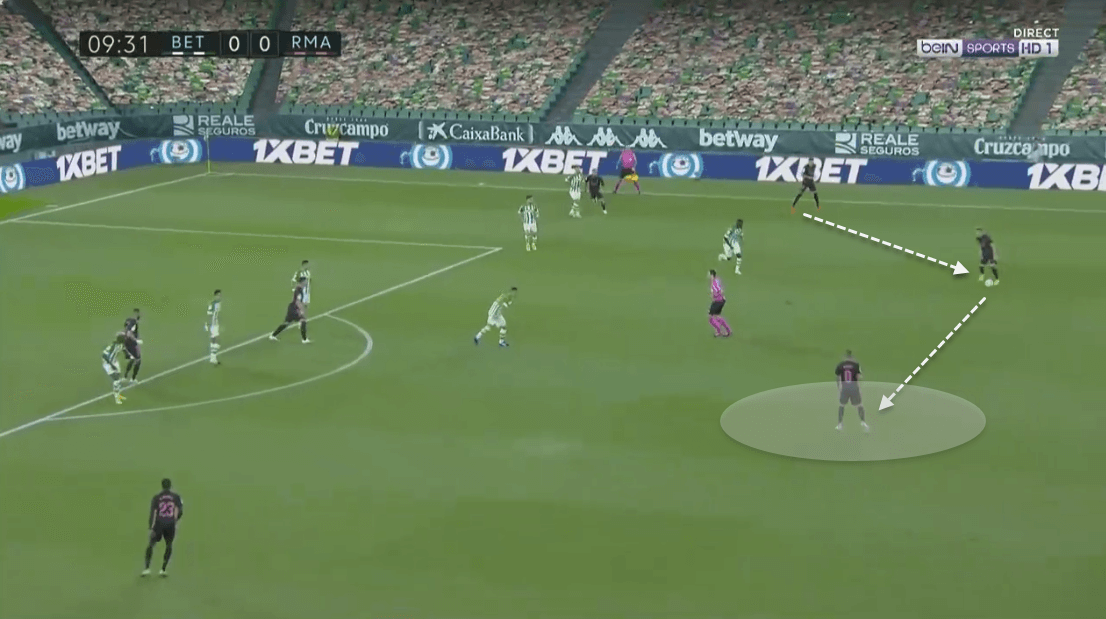

In addition to the exchange of long balls between the wide players, Madrid tried to use their midfielders to switch plays into space. The presence of four players in advanced areas – two forwards and two wide full-backs – forced Betis to defend in numbers and deploy players in wide, which opened space for the midfielders to operate freely. Like an instance from the 9th-minute shows below, when the ball comes to Kroos from Valverde, he has acres of space to make a forward run, or to pass it to Mendy, who has even more space than he does.

Although both switches were a part of Zidane’s plan for the night, the switch from Mendy to the right side was more prominent. As a result, 55% of Madrid’s attack came from the right side, and the side obtained an xG of 1.54 from 17 attacks through the right flank.

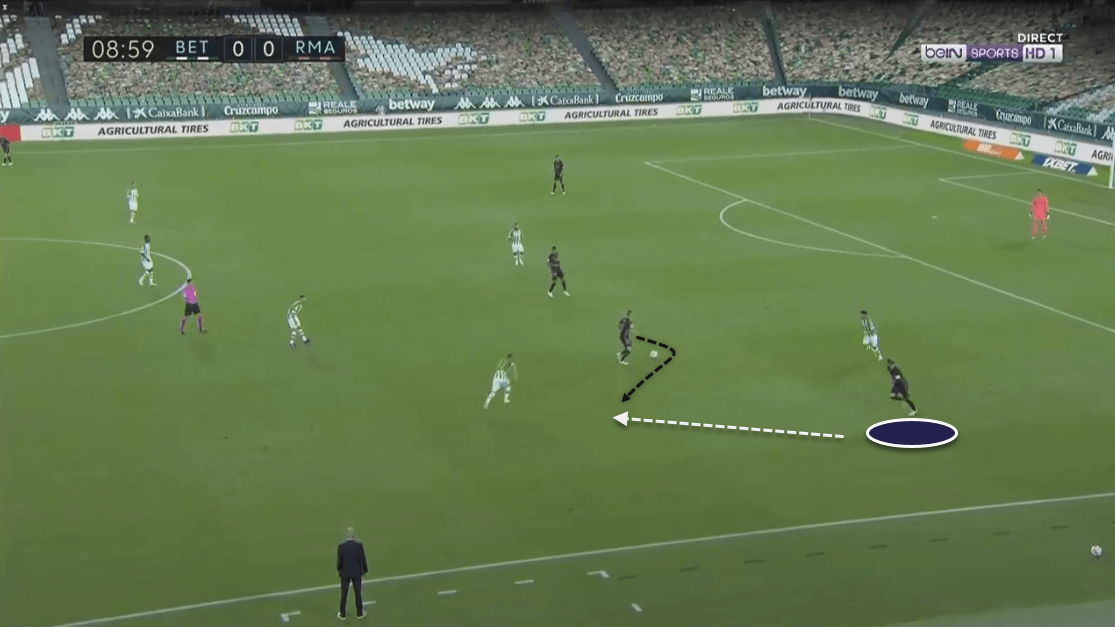

Betis’ varying press to counter Madrid’s build-up

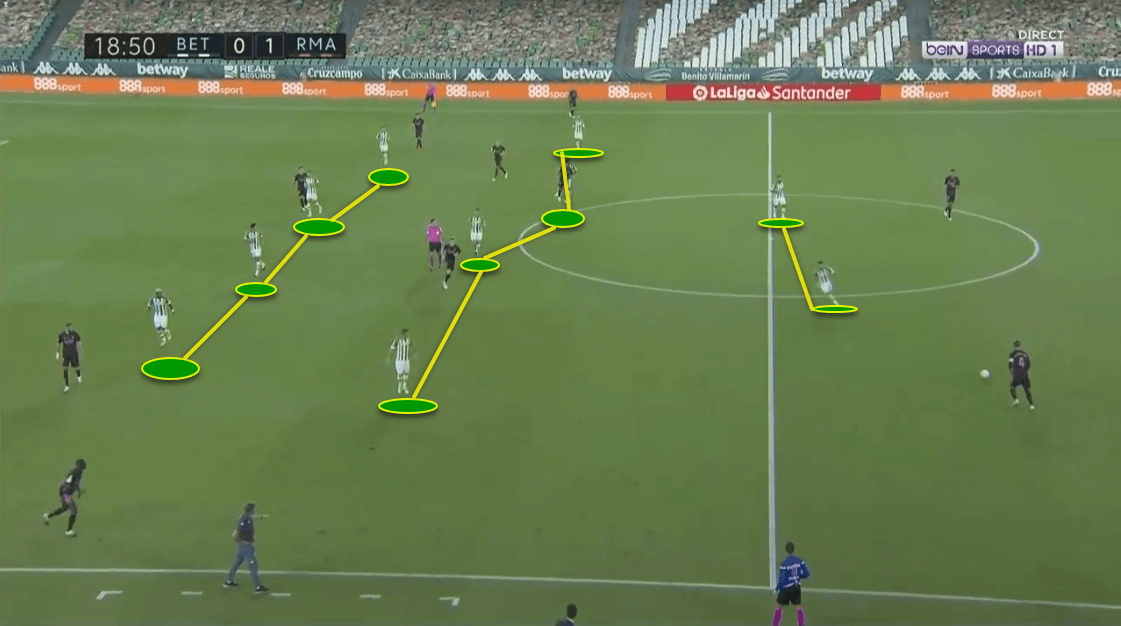

Since Madrid’s backline and the whole shape was dynamic during the build-up, Real Betis tried out some adaptive approach to get the ball off Madrid players and keep the pressure on. Hence, despite starting as a 4-2-3-1 side, the front line constantly kept changing, depending on how Madrid approached their build-up.

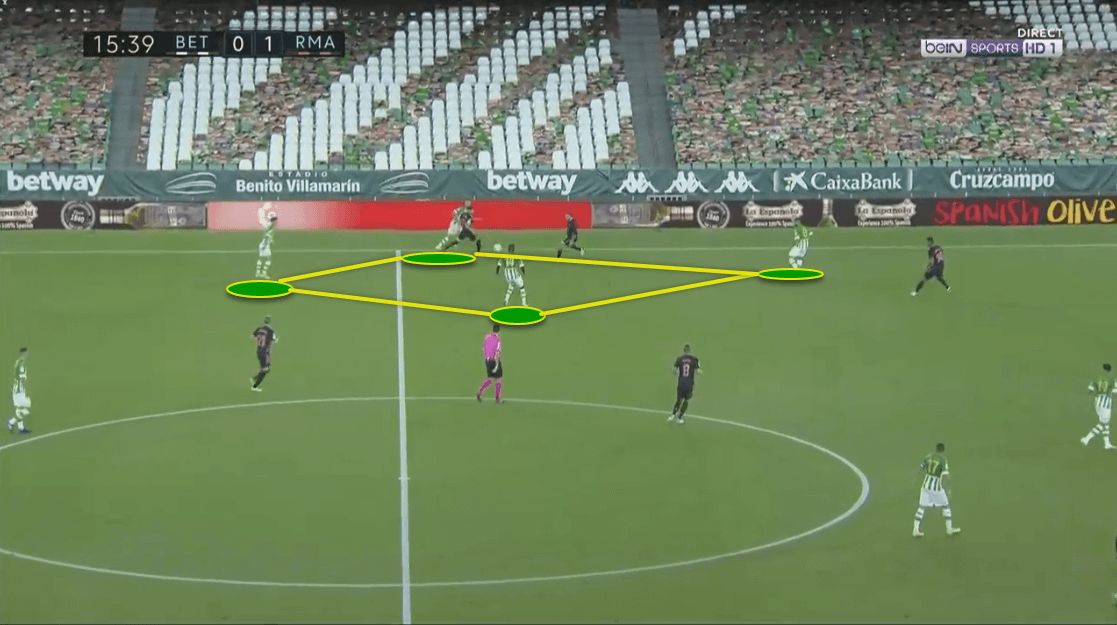

Generally, the off-the-ball pressing shape was a flat 4-4-2, and a mid-block was formed. The side maintained a compact shape vertically, with efforts to limit Madrid’s penetration. Additionally, 4-4-2 gave Betis chance to counter Madrid’s approach of playing through the wide sides, as they looked to occupy the wide channels with four players both in the midfield and the backline.

However, the plans weren’t as successful as they were meant to, as we can clearly see the passing lane to Mendy open up.

The shape, however, changed when Madrid switched to a three-man backline, unlike the picture. The main motive behind Madrid’s switch to the three-man line was to involve a midfielder by playing from the back. When they did this, Real Betis deployed a three-man press upfront, attempting to further push Madrid in their own half. The relative intensity of press during situations like these were high as well.

One can easily see everyone getting covered in the backline, with three players involved in Betis’ press. The goalkeeper came into play during these situations as Madrid tried to delay the momentum to find spaces or better players to pass forwards. This approach worked, and Betis were able to limit Madrid during these situations. Lapses in territorial coverage, especially towards the wide areas, nullified the advantage that Betis created in these situations ultimately. After being limited to 10 men 20 minutes into the second half, Betis approached with a 4-4-1, making them unable to cover spaces and press relentlessly.

Betis’ build-up and the preference towards the left

Real Betis’ shape favoured them to play relatively wide and then converge towards Sanabria. Hence, the build-up involved a lot of wide work in the midfield and the back, rather than in the advanced areas. However, the central spaces in midfield were a key area where Betis tried and succeed in playing out.

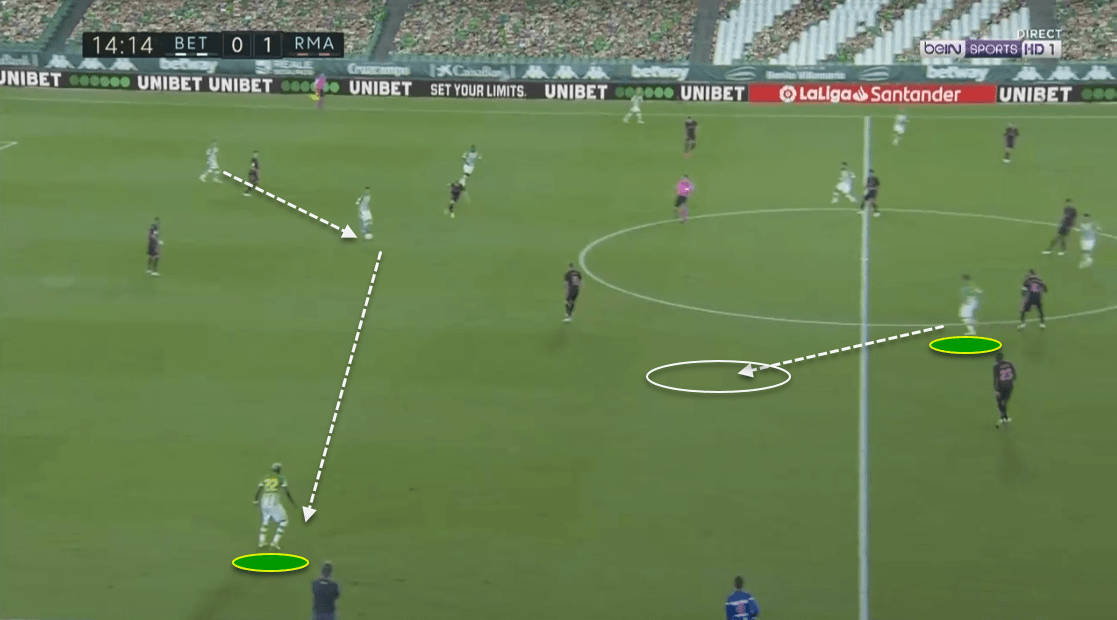

Like we can see above, the central Rodriguez drops deep in space, and he gets the ball after Emerson receives and directs it to him. In addition, these moves helped Betis to round up and form overhauls in the wide areas. For instance, on this occasion as well, Rodriguez’s movement attracts players towards his left, hence leaving space for the others to play in the space quickly.

As a result of movements like these, Betis tried to build-up from the wide and had men in abundance in those pockets.

When Madrid tired to win ball by getting more involved in the overhauls that Betis formed, they had to withdraw a player from a more central area, due to which Betis could now converge with a pass to the innermost player in the overhaul. Hence, in both cases, with or without opposition players, Betis were looking to progress and converge. In situations like above, the main methods of converging were targeting the two strikers, who are making central runs.

One of the most pivotal roles was played by full-backs in this process. Unlike Madrid’s approach, the fullbacks were used as wide components in the back rather than in the advanced positions. This meant that the wide midfielder always had an extra player to pass backwards when he had multiple opponents closing him down.

Like we can see above, Madrid’s press spreads when the full-backs are deployed wide in a deep position, unlike Madrid who used one of their central midfielders to compensate for full-backs in the upper half of the opposition area.

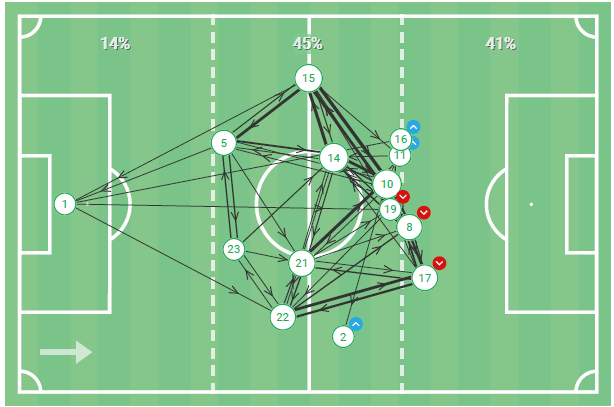

To sum up, Betis’ efforts of converging to their forward via functional wide areas was quite successful, and their pass map is evident of this fact.

Another thing to notice is the thickness of lines converging from the left compared to passes from the right. As players like Nabil Fekir, comfortable in carrying and passing the ball, operated from the left, attacks and passes started predominantly from the left. In addition, the right side was dominated by players like Joaquín and Emerson, known for their acceleration and runs rather than passes.

Conclusion

Although Madrid emerged victorious and their campaign to defend their title from Barcelona looks to have kicked off, Betis’ efforts really pushed them to their limits. With adaptive tactics and formative gameplay, Betis might be heading to a stable performance for the rest of their season.

Comments