In this La Liga midweek fixture, Valencia took on Sevilla at the Mestalla. The guests were without their head coach, Julen Lopetegui, who had COVID-19 symptoms on Wednesday, and also six players were out of the game due to injury. While Sevilla are chasing Real Madrid and establishing their top-four status, only one point was acquired in this fixture as José Bordalás made good tactical adjustments to bring his team back into the game.

This tactical analysis explains the dynamic change of the game, and the positional tactics of Sevilla that helped them to control the game.

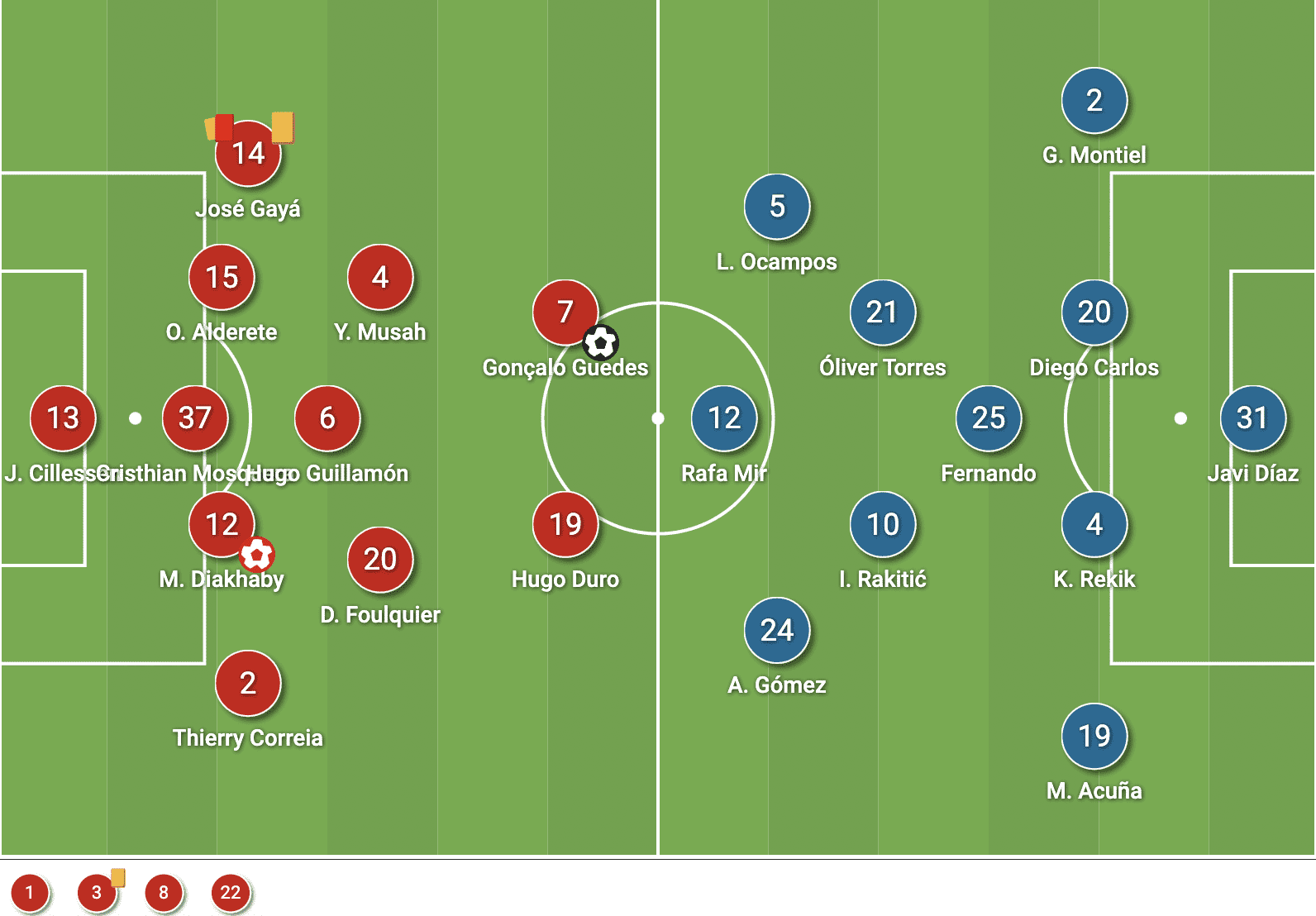

Lineups

Valencia did not start with the trademark 4-4-2 of Bordalás, although they reverted to that formation later on. Several changes were made after the heavy loss to Real Madrid: Maxi Gómez, Hélder Costa, Daniel Wass, and Cristiano Piccini were dropped as Hugo Duro, Dimitri Foulquier, Thierry Correia, and the 17-year-old Cristhian Mosquera started.

Without the likes of Jesús Navas and Jules Koundé, Sevilla paired up Diego Carlos and Karim Rekik as the centre-backs. They also rested Joan Jordán and played Ivan Rakitić in the midfield trio, the other two players started with him were Fernando Reges and Óliver Torres.

Positional fluidity of Sevilla

Lopetegui spent seasons at Los Nervionenses to transmit his football philosophy to the players, and the effects were clear as the team was no longer represented by formations and numbers on the match. They wanted to have the ball, move the ball, and use the space, and to dominate the oppositions, the players had good knowledge on the principles of plays, and this allowed a large scale of positional interchanges in the offensive phases. That created a strong dynamic with different tasks were presented to Valencia, which the opposition were unable to solve until Bordalás made significant tweaks around the half hour mark.

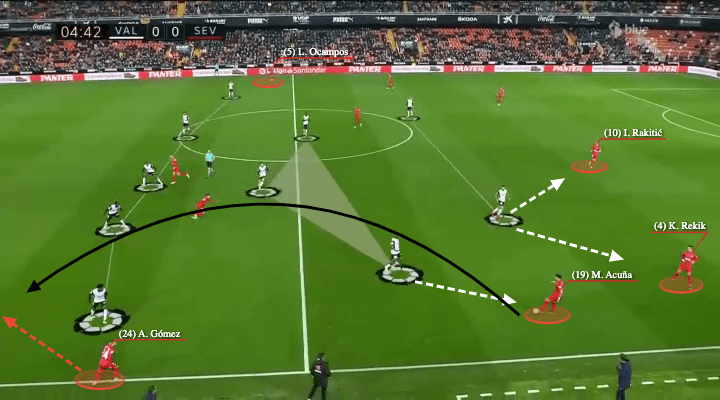

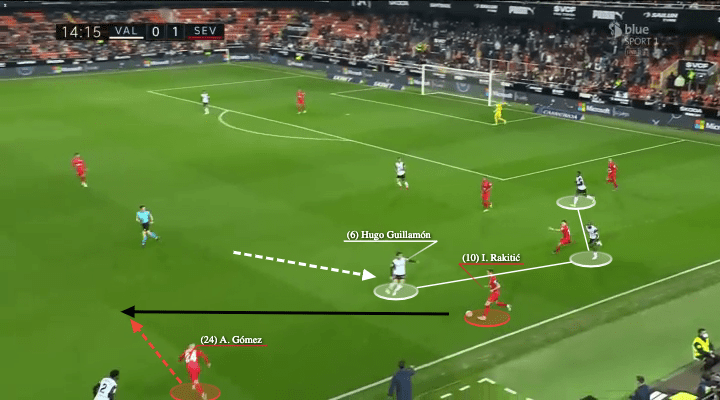

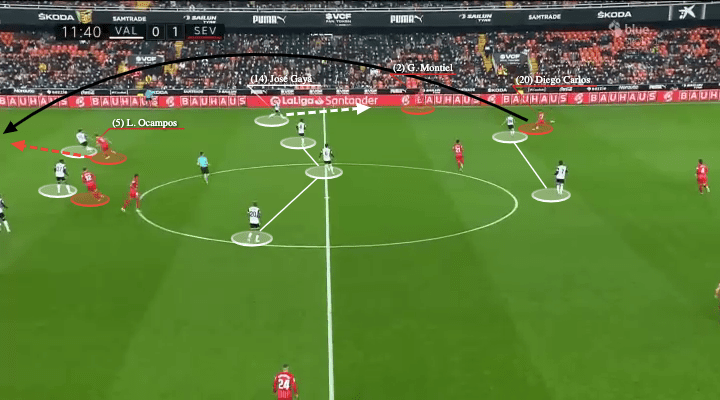

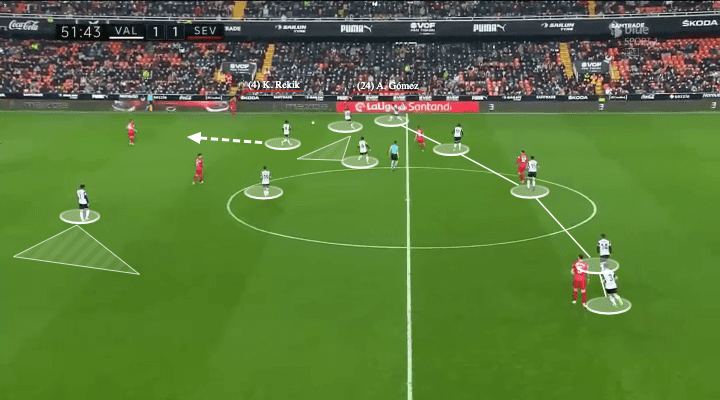

At the start of the game, Valencia defended in a 5-3-2 formation with the backline staying together. The wing-backs are fixed by the high and wide wingers of Sevilla (Papu Gómez & Lucas Ocampos in the above image), so they would not jump out to close the wide spaces. But the lines are vertically compact in general, so there are not many spaces for Sevilla to play behind the midfield. More accurately, it was a 5-1-2-2 as the main role of Hugo Guillamón was to cover, he stayed deep to defend the diagonal spaces behind partners.

Sevilla players were interchanging positions at the beginning, in this scenario, Rakitić dropped between the centre-backs to make it a back three, constituting a 3v2 advantage in the first line. However, this pressing from Valencia’s 8 was successful since the position of striker was great, he was between Karim Rekik and Rakitić to bait two passing lanes. Marcos Acuña recognized the potential dangers of going backward or lateral, so he just kicked the ball forward for Gómez to run behind, but the Argentinian was not famous for his pace and ability of making forward runs, Correia had no problem with it.

If Valencia went for a high press, they wanted to press the opponents in one side, man-mark all the passing options around the ball very tightly, so there was no space to get out. The strikers might not be initiating the press, but they must be in a position that could chase the backward pass when Sevilla made it.

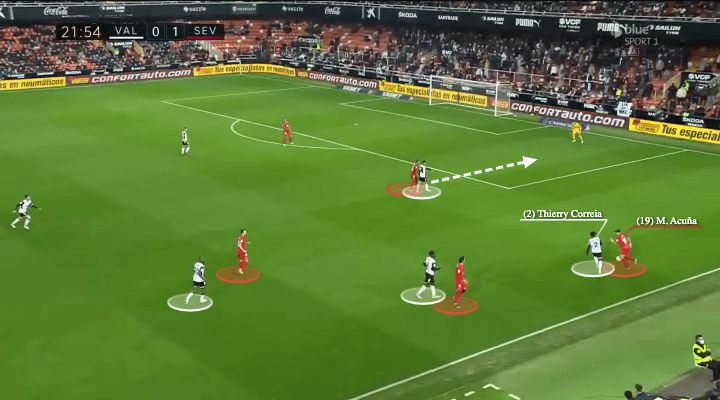

The above scenario was a successful high press of Valencia, as Correia was aggressively jumping onto Acuña. Meanwhile, the other two midfielders were closing Rekik and Rakitić by sticking to them tightly, and Duro was baiting that backward pass, Acuña was left without options and the ball was recovered easily by Valencia.

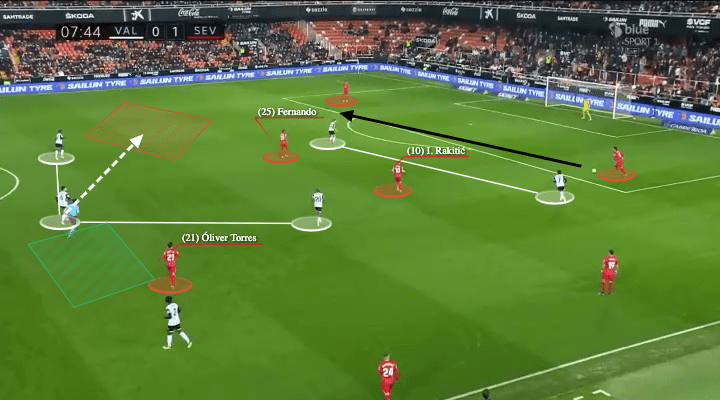

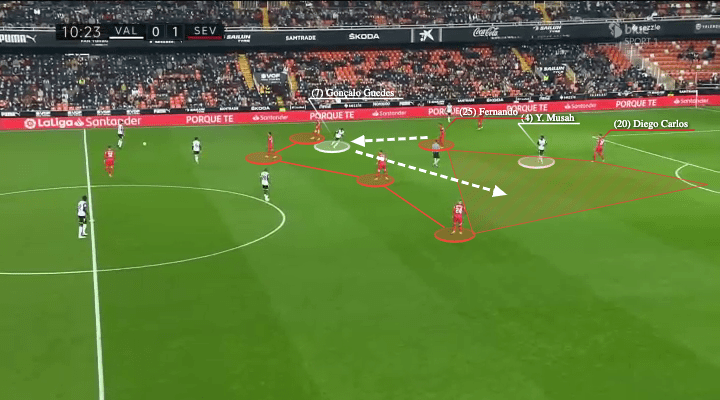

But when the positional interchanges of Sevilla became complex, involving more players in the build-up, Valencia struggled to adapt because the backline did not close spaces enough. That resulted in the front players were under a numerical deficit during the press, and the opponents capitalized on that to beat the press easily.

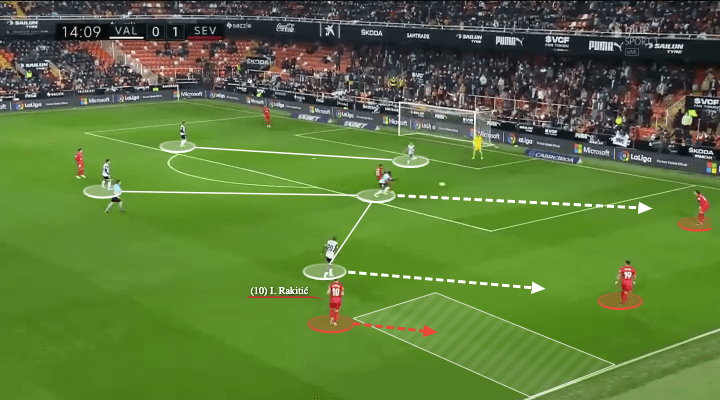

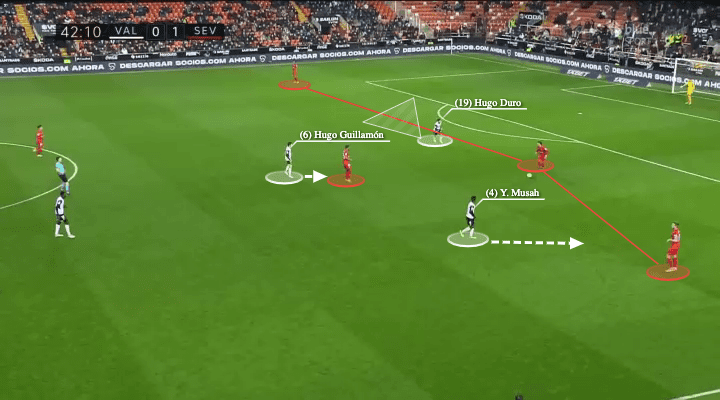

In the above situation, after sequence of passes, Yunus Musah jumped out to press Rekik from the centre. Simultaneously, Foulquier also pressed Acuña to make it a 2v2 in the wide spaces, but the distance to travel was quite large so he was unable to close the angle of the receiver on time.

Since Gómez pinned the wing-back in the last line, there was no one else to protect the wide spaces if Sevilla had the third player on the left side build-up. Rakitić saw the defensive behaviours of the opponents, so he just moved into the white space where he ended up behind of Foulquier.

Since Foulquier could not close Acuña’s angle, the Sevilla left-back managed to reach Rakitić, and now, the press was broken. Valencia reacted with Guillamón to cover that wide space by moving from the inside, but again, the distance to travel was too big, he could not close the angle of the receiver.

Sevilla perceived the spacing in the opposition block very well as Gómez now dropped from a higher position, and had the autonomy to go inside because the central spaces very vacated by Rakitić already. The movement suited him as he was a right-footed winger, when he went inward, the angle and visual area perceived were optimal and Sevilla could go and confront the last line of Valencia. His marker, Correia, was engaging from a vertical angle, that’s why he could not stop Gómez from going inside.

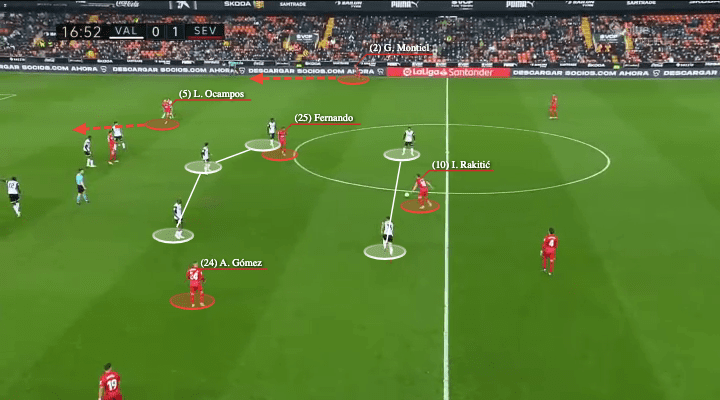

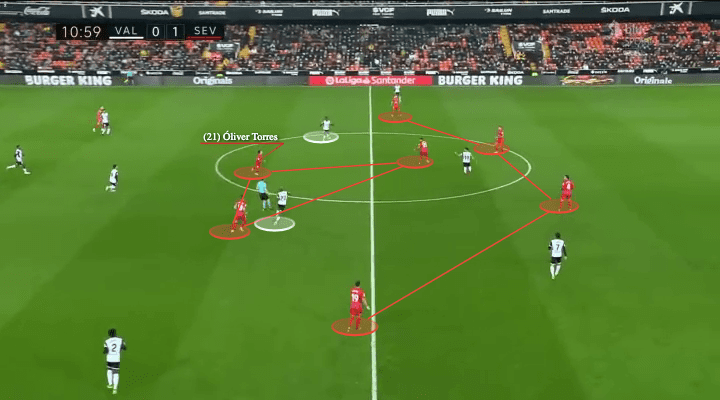

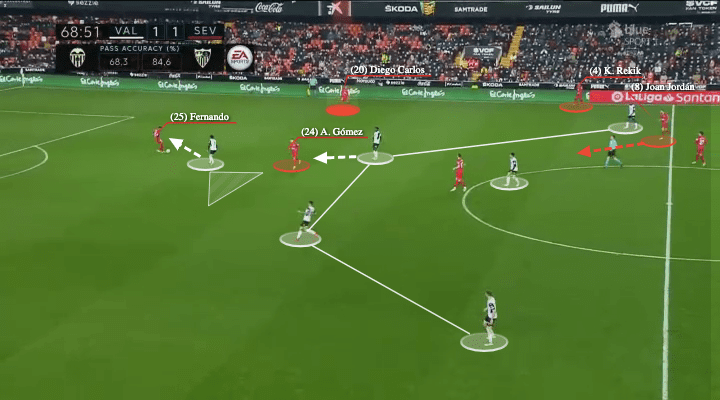

The Sevilla midfielders rotated a lot to come up with different shapes, exploiting the loose Valencia press. In the above situation, it was an asymmetrical 4-2-3-1 as the right-back was high, Acuña was deep, and Rakatić dropped alongside Fernando. The Valencia first line did not pay too much attention to the players behind as their role was to press the centre-backs.

But the 5-1-2-2 shape of Valencia became an issue as Guillamón was covering to much ground. Initially, Torres cleverly stayed on the lateral spaces of the Valencia 6, which was also the spaces behind Foulquier. When the ball moved, Torres would eventually become a free player behind the second line as Guillamón must go to the left side and cover Musah on the other side. That was the clever part of Sevilla’s midfield shape because Foulquier could not recover position in limited time.

Sevilla used the left flank as their strong side at Mestalla and they exploited the structural issue of Valencia’s 5-1-2-2. The pressing from the hosts would be unsuccessful when the wing-backs could not close the wide spaces, and they were outnumbered in the first two lines. Los Nervionenses were able to control the game in the early stages by moving the ball to stress the opponents.

In the above screenshot, Gómez pinned Correia again with his high and wide position. So, when Foulquier pressed from the centre, he was without help. The direction of the press did not mean too much because the Sevilla 8 (Rakitić) has moved out of the formation to play, so he was facing the opposition goal as Foulquier did not defend that space in front of him. This became a 2v1 that allowed Acuña and Rakitić to cancel the press from Foulquier with simple passes between the duos.

Apart from playing short passes, Sevilla were also direct because they would search for the attacking depths behind the defence. It was a useful strategy to push the last line backward as Valencia did not set the last line too deep, they could find spaces behind.

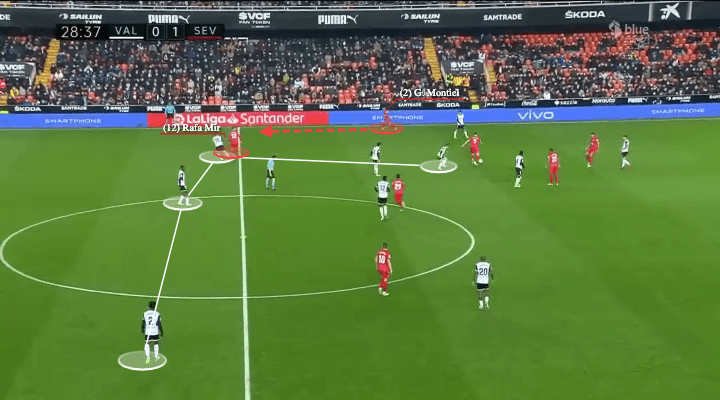

When Sevilla played with a 2-1 shape, the player in the centre can have some time to play as the Los murciélagos strikers did not close that space between them enough. The guests also occupied the Valencia 8s in deeper spaces as Fernando would go higher in such a case, with Gómez coming infield as well. Sevilla also used Gonzalo Montiel quite high in the wide spaces, so Ocampos had some freedom to play closer to the goal frame.

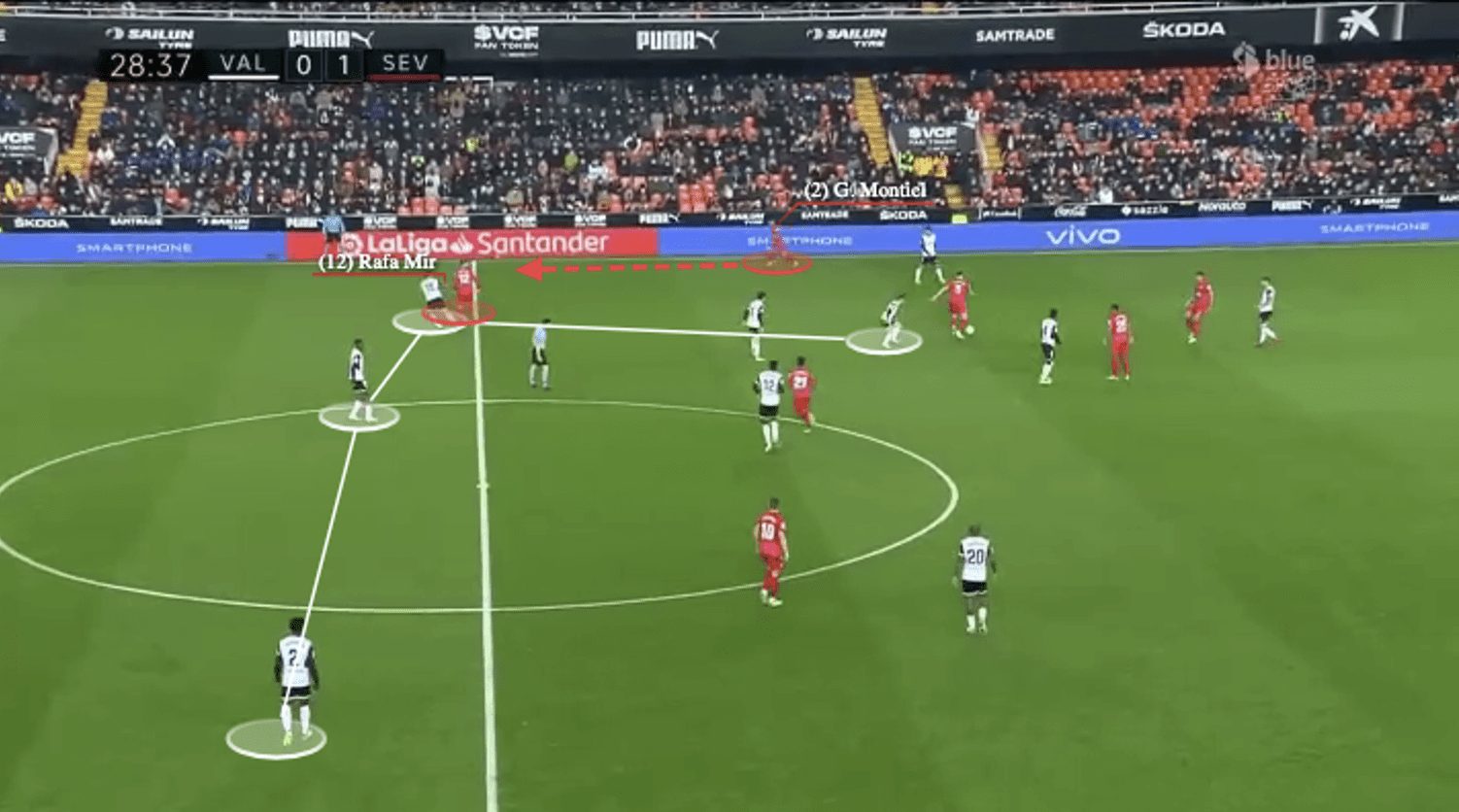

In this game, Diego Carlos was a bit too impatient as he played the ball long at times even the condition was not ready yet. In the above situation, it was alright because the runner was presented. With Montiel staying wide to drag the Valencia wing-back out (José Gayá), and Rafa Mir orienting himself towards one defender for pinning, Ocampos had a 1v1 opportunity to outpace Omar Alderete. The runs from behind mostly came from the right side in the first half as Ocampos had that awareness to go behind and receive in spaces.

Comparatively, Gómez on the other side tended to receive the ball at his feet as he possessed less pace. The Argentine international would move out of his position in the second phase, using Acuña’s high position to get rid of Correia. In the above screenshot, you could see the Valencia’s three-man midfield line was lacking the horizontal coverage to defend the wide spaces. Whenever they needed to press with the midfielders, the distance to travel was too big. While Gómez received, he could turn and face the opposition goal very easily as the opponents could not close the red space, Sevilla dictated very easily.

Bordalás’ 4-4-2 & 4-3-3

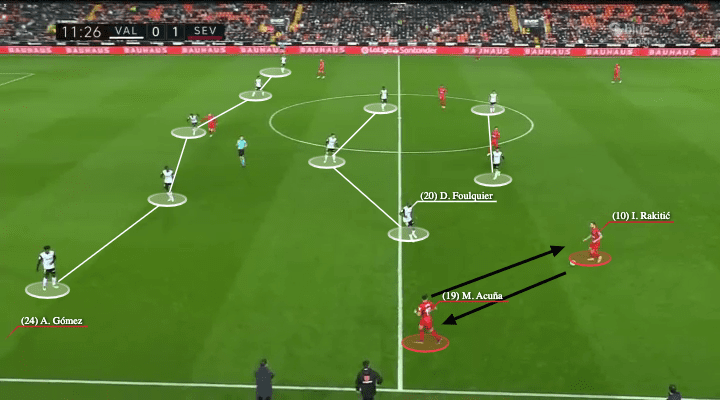

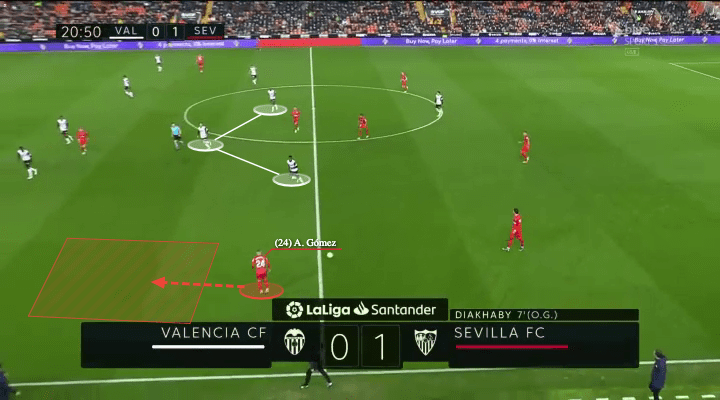

Because of the structural issues pointed out in the above situation, Bordalás reacted quickly and made some adjustments to the formations. Valencia changed into a 4-4-2, then, a 4-3-3 which helped the team to press better with one more player in the midfield.

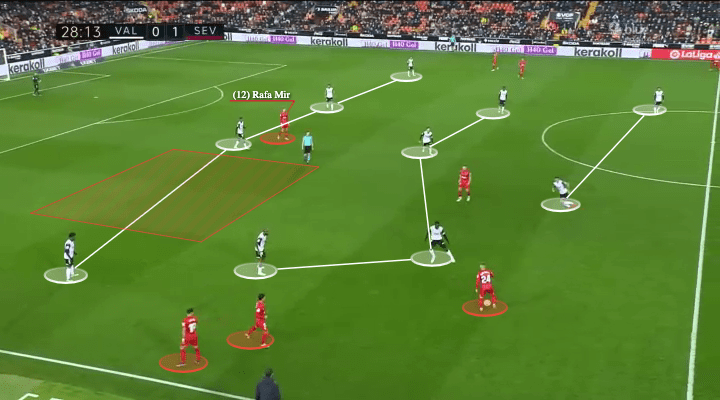

Bordálas released Mouctar Diakhaby from the last line, and he becomes another 6 as a partner of Guillamón in the 4-4-2. The wingers were Musah and Foulquier and they stayed narrow in the midfield as well. It was a good tactic to encounter Sevilla’s approach. The opponents dropped many players outside of the formation, so Los murciélagos should to close space earlier before they arrived at the final third.

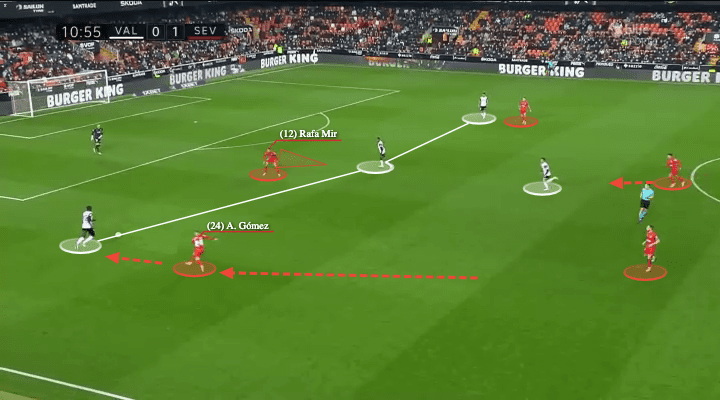

In the above situation, it was Gómez to play in the midfield again, they also had Torres and Acuña on the same flank, but note that they were also lacking the runs to attack spaces behind on this side, as a result of the position of players. So, it makes sense to push Diakhaby out in the press and let him close Gómez in the half-spaces. Also, leaving the orange spaces big was not a major concern given Mir was not Youssef En-Nesyri, he rarely runs into that space and he did not possess the pace to beat the centre-back either.

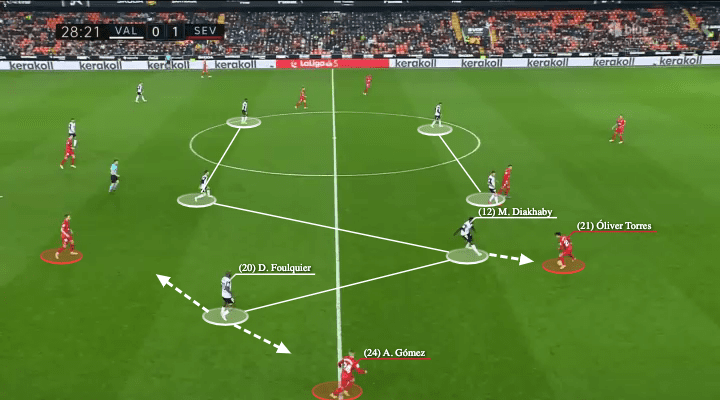

Therefore, Valencia’s press disrupted the rhythm of Sevilla when they confronted the ball higher. In the above image, Diakhaby was very high in the press again, he was going for Torres and blocked his forward passing angle. Given the narrowed passing lane, it was easier for Foulquier to defend the space behind Diakhaby, while keeping an eye on Gómez. Furthermore, Sevilla even could not go diagonally to the midfield as the Los murciélagos strikers were deeper, they could only circulate the ball outside of the Valencia block but not going inside them.

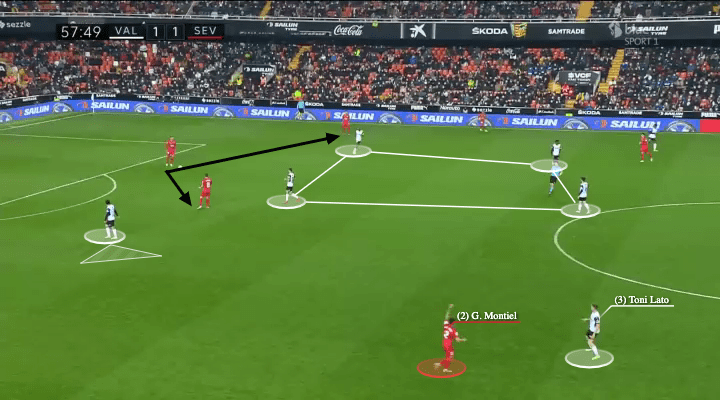

If Sevilla were to attack, the shift of formation would be a concern when they were defending spaces behind. With only four men at the back, it was easier to separate the defenders and create isolations. Here, Gayá followed Ocampos to the midfield, and Mir occupied the ball-side centre-back as usual. Consequently, Montiel could go high and wide to receive a long behind the last line when the Valencia winger did not track him.

But then Bordalás tried to cover that weak spot again by adjusting the defensive shape again. This time, the shape was more like a 4-3-3 with Musah coming high to press on the right side. The main role of the lone striker, Duro, was to block the switch and made Sevilla playing to Musah’s side. To counter Montiel’s forward run and threat on the right flank, Gonçalo Guedes defended very deep as the left-winger, but this was a temporary solution only because Bordalás would not have wanted his best attacker staying far away from the opposition goal.

Also, as shown in the above image, Guillamón had more courage to press the “1” of Sevilla’s build-up because he knew there was cover behind. With these changes, Sevilla found themselves more difficult to play in the closing stages of the first half.

Valencia’s attacks

Valencia had some issues in terms of chance creations in this game with a 0.56 xG from 10 shots. First of all, they were very direct in the first half but the condition reaching the advanced areas was not good enough, while they were also lacking the quality in the final third to generate more clear-cut opportunities.

Therefore, the pressing of Sevilla was rather simple, and they kept more players in their own half. The striker mainly blocked the passing lane between centre-backs to make sure Valencia could not move the ball from side to side, Mir also kept an eye on the goalkeeper to press the backward pass.

Then, the winger would jump out to press the wide centre-backs, getting close to force them play as Gómez did above. Valencia played with a 3-1 shape, but the deep Guillamón was not tightly marked as he might be a decoy to pull the Sevilla midfielders out of positions. Then, the guests would be missing a player in the second ball battles. In this case, Torres did well by being alert of the long ball, and he did not go too far with Guillamón.

The strategy of Valencia in the first half was to separate the opposition centre-backs. Specifically, they wanted to exploit Carlos’ side with more movements and attacks coming from that flank. The strikers took up alternative roles as Guedes would play deeper at times to try pulling Carlos out, and Duro was higher to pin Rekik down. Then, given it was a 2v2, they separated the centre-backs and would be able to create the gaps to exploit.

In the above example, Guedes drifted wider to receive the ball and Carlos came out to follow him, with Duro’s position keeping Rekik on the other side, Musah was the player to make a deep run and exploited that gap. If Rekik went covering the run, Duro would be left without marking until Acuña narrowed that space down.

It was also very similar when Valencia attacked with the long and direct football. This was in an indirect free-kick in the midfield, Guedes inclined himself to the left side to bring Fernando away from the centre, then, he dropped and made the run into the centre where the red space was created. That was also the space in front of Carlos, since Musah was high to dominate that space around the centre-back, the Brazilian had troubles if he was going to deal with both players.

A fresh Valencia

The best part of the game was how Bordalás kept changing his tactics to pose questions on Sevilla. During the halftime, maybe the guests were talking about the back four in the locker’s room, but the Los murciélagos came out with a flexible formation between a four and a five-man defensive line. That was a very successful move as it blew up the confidence of Sevilla, and Valencia were the stronger side in the first period of the second half.

Sevilla made some changes as well by using Jordán to replace Acuña. Fernando was dropped as the centre-back, and Rekik moved to the left-back position.

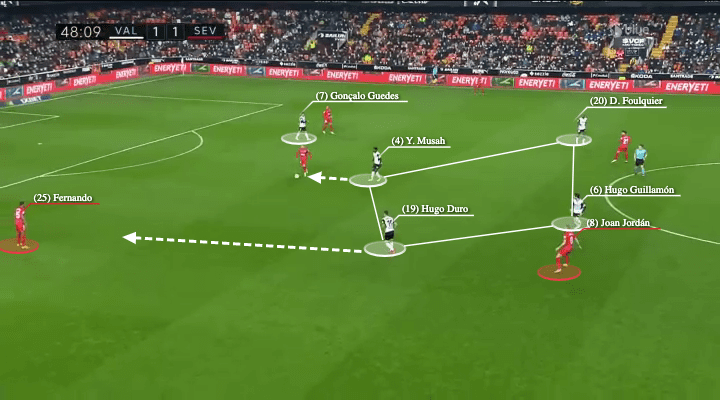

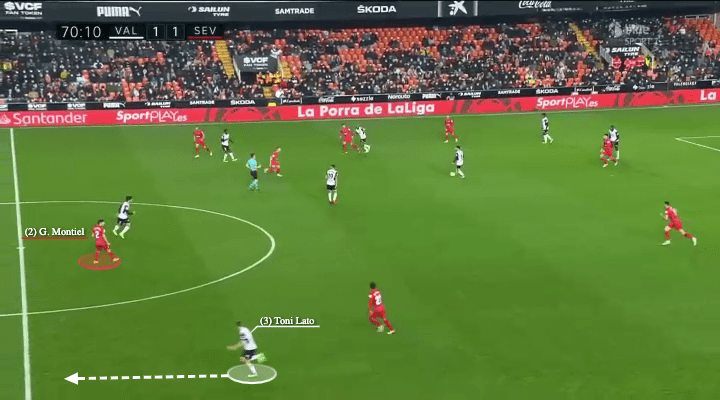

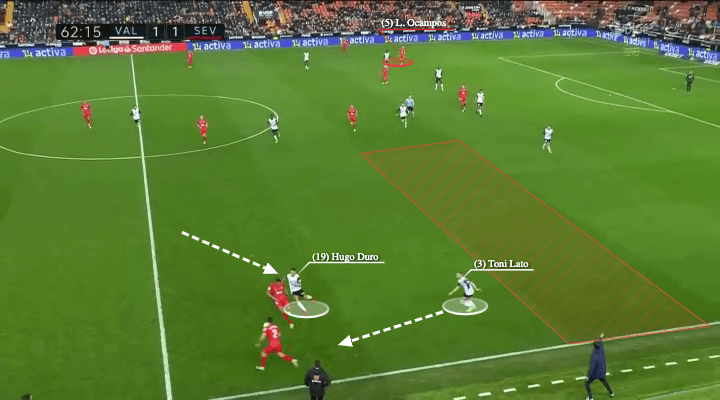

Bordalás gave very specific instructions on the player. Firstly, he moved Guedes back as a striker to keep his best man in the attacks and the counter-attacks, the Portugese international did not have to initiate the press, all he did was to block the passing lane between the centre-backs. To cope with Montiel’s threat on the right side, the substitute coming in: Toni Lato played on the left side. His job was simple, which was keeping an eye on Montiel, if the Sevilla right-back moved forward, track him. If the target stayed deep, press him. Then, the threat of the opposition right flank was mostly cancelled.

Hence, the Valencia formation was somehow switching between a 5-D-1, a 5-1-3-1, or a 4-1-4-1. In the above scenario, Montiel was high and Lato was marking him, so it looked like a back five. Another change was to establish a stronger “pressing & cover” relationship in the centre, with the other three players being authorized to press high, Guillamón was staying deeper to cover the other midfielders. This new shape allowed Valencia to handle Sevilla’s approach to drop multiple players in the construction phases.

In this scenario, Guedes blocked Carlos, so they kept Sevilla in one side. Then, Musah jumped out to press the “1” to force a lateral. Valencia would then continue the press by the midfielder from deep, Duro was a midfielder in the second half and he could press Fernando. The most important of the 5-D-1 or the 5-1-3-3 was the cover provided behind the second line, as Guillamón could immediately catch Jordán when Duro could not cover the Sevilla 8.

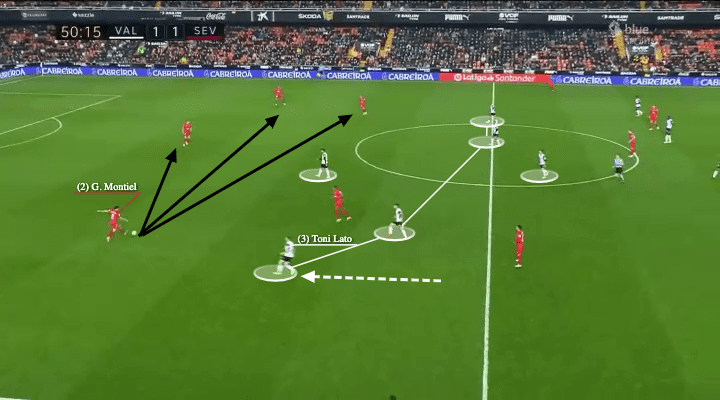

The problem of Sevilla was their football was not really progressive even dropping multiple players in the construction phases. Here, Valencia became a 4-1-4-1 as Lato came out to press Montiel. Although the Argentine right-back had as many as three passing options on the left side, but none of option was progressive. So, even the ball went to the left side, Sevilla did not break the lines and more work must be done to advance the ball forward.

The difference of this new back five system was the wide defending. Bordalás was aware of the Gómez situation in the first half, and his side were more aggressive in those situations after the break. They would still let Sevilla come and Gómez drop, but the wing-back would be closing that space by marking Gómez tightly. Also, the right midfielder, Foulquier moved out to press in the wide zone earlier, so he closed Gómez’s diagonal/lateral space and stopped him dribbling inside. While there was not many choice, Gómez played it backward which triggered the Valencia press.

Another unsung hero in these cases was Guillamón. The Valencia 6 must position himself correctly to close the central spaces and half-spaces, so the pass from the left-back could not go inside. The hosts closed one side well in the second half and the positional strategies of Sevilla did not work.

The problem of Sevilla might be the players are moving too much. Sometimes when they rotated, the occupation of several key areas was lost in the process and the structure was imbalanced. For example, they could not break the lines in the centre because they did not have the presence behind the first line. Then, the ball was likely to go to the sides as it was difficult to break two lines with one pass.

In the above example, the formation of Valencia was not important, as Lato just did his defending on Montiel as explained. The remaining of the pressing bloc was on the right side, with Guedes closing the passing lane to Fernando, Sevilla were forced to play in one side again, and the manipulation of the second line was missing as the players were spreading too wide, vacating spaces in the inside. Again, neither Rekik nor Jordán was a progressive option here.

Sevilla had some serious issues after coming back from the dressing room, they lost the rhythm to play and there were so many cheap mistakes. While some of them were attributed to the player’s individual errors, some might also be explained from a tactical perspective. It was out of the same reason; the players were running too much, and the positional structure collapsed.

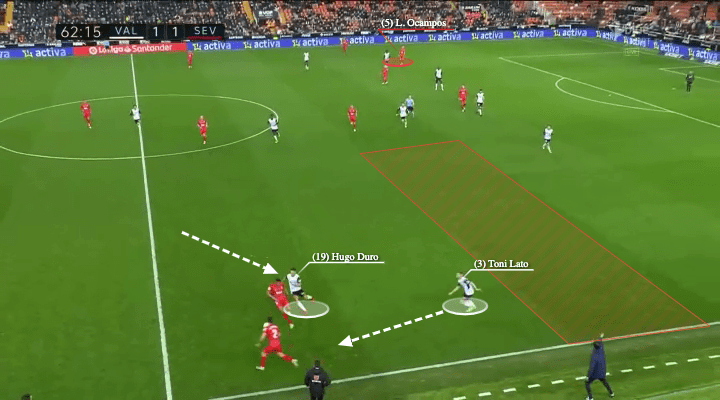

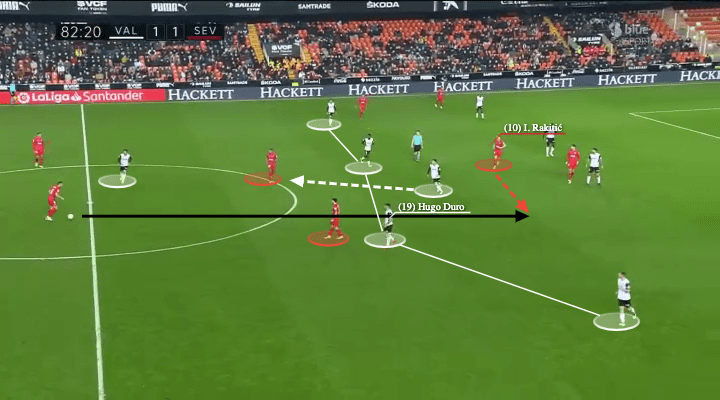

For example, they had a dangerous counter-attack conceded as Fernando gave away a soft pass in the above situation. The former Manchester City man could have done better of course, but it happened because of a structural issue. Sevilla involved more players on the left side, trying to run through the right-back and right centre-back, and this time Ocampos travelled from one side to the other to make that movement. As a result, when the ball went back from the left to the right, Sevilla did not have the occupation of red space, there was no option provided behind the last line as well. If Ocampos was the winger to stay high and wide, then he should not leave, but we are not sure about the exact role given to the player so it might not be his fault. So, Fernando had no choice and he messed up with Montiel. Credited should also be given to Duro, who chased Fernando all the way to force the error. The Uruguayan player adapted quite well from being a striker to being a hard working midfielder.

Sevilla moved again

After a terrible start in the second half, Sevilla came up with several solutions although we do not know they were from the instructions on the bench, or it was the improvisation of players. They had better control with these changes and gained more threat after the introduction of Tecatito Corona.

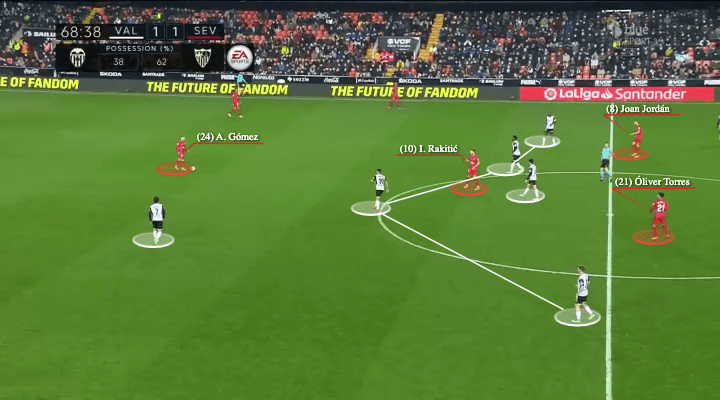

Before being subbed off, there were a few occasions which Gómez dropped very deep, even to the outside of the formation to receive. This ended up being a good condition for Sevilla’s attack as the midfielders were staying higher, they could manipulate the second line. In the above image, Jordán and Torres were behind of the second line, while Rakitić could stay higher instead of moving out and deep to the left half-spaces.

After some seconds later, Valencia tried to press but the presence of Gómez in the build-up became the key to break the defence. While Guedes was pressing Fernando to force him going to the left side, Sevilla were not afraid of doing so because their 8 would press Gómez, 6 was on Rakitić, and the right-winger (Foulquiera) came inside to mark Jordán.

In this new positional structure, the two centre-backs stayed in the same vertical half, with Gómez inviting the opposition midfielder to press him in the centre, no one else from Valencia could press Carlos in wider spaces. They had rooms to play and move to force the ball forward.

To handle the 1v1 situation of Lato and Montiel, Sevilla also changed a bit by inverting the right-back into the centre to help him getting rid of the marker. In the above scenario, it was Duro to who marked Montiel as Lato was not supposed to go into the centre by far. Then, there was a domino effect as now the Valencia 6 (Guillamón) shall press the player in front of him, as Duro was unavailable now. Sevilla capitalized on that by freeing Rakitić between the lines, as the former Barcelona man just moved laterally to offer a vertical option. After drawing Guillamón out, the spaces in front of centre-backs were lacking protection and Sevilla accessed that very easily.

But this is a two-sided coin as the inside positioning of Montiel vacated the wide spaces. The opponents could target the spaces left in the outside and make runs to exploit. For example, Valencia counter-attacked with Lato’s forward run on the left side, where Montiel could not cover as he was in the centre initially, the costs could be potentially very big.

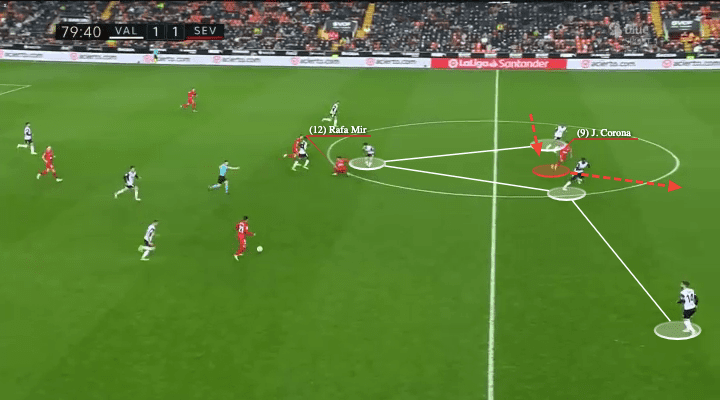

As we mentioned in the above analysis, Sevilla made more runs behind on the left side. Gómez’s roaming position was good, but the coach wanted the injection of pace in that area, so Corona came in to replace the Argentine attacker. Corona made an impact and his energetic runs on the right side forced Bordalás to change again. Bordalás replaced Correia with Marcos André the right defender looked more tired in the second half, he could not cope with the runs. Hence, Foulquier played as the right defender.

Some runs of Corona were very dangerous and resulted in goal-scoring opportunities, the above image was not one of them but that shows how the substitute compensated the striker. Mir was more a target, and he could pull the centre-back out when there was an aerial duel, then, Corona could sneak infield to make a run behind the remaining centre-back, that was a simple separation. Corona made runs in the outside spaces in general, but he also shows his threat to goal if spaces were presented in the centre.

Conclusion

This is one of the most tactical and dynamic matches I have analyzed this season, when one side changed and adapted, the other side very quickly came up with something new to counter. As our analysis summarized above, there are at least six to seven clear changes throughout the game. Both teams had the chances to take the win but neither side were able to convert their chances in the second half, but one point each should be a fair result after concluding the overall performances.

Comments