After beating West Ham United, Sevilla travelled to Madrid as Rayo Vallecano awaited. Before the game, Andoni Iraola’s side had not won in the last eight La Liga games and they were still looking for the first league win in 2022. However, things did not go easily for the guests, as Vallecano resisted very well, and even gave Julen Lopetegui’s team a very tough 90 minutes. At the end of the match, Sevilla only recorded three shots according to Wyscout – the lowest in this season – they even had more attempts against opponents such as Real Madrid and Barcelona.

This tactical analysis would explain why Sevilla struggled at the Campo de Fútbol de Vallecas.

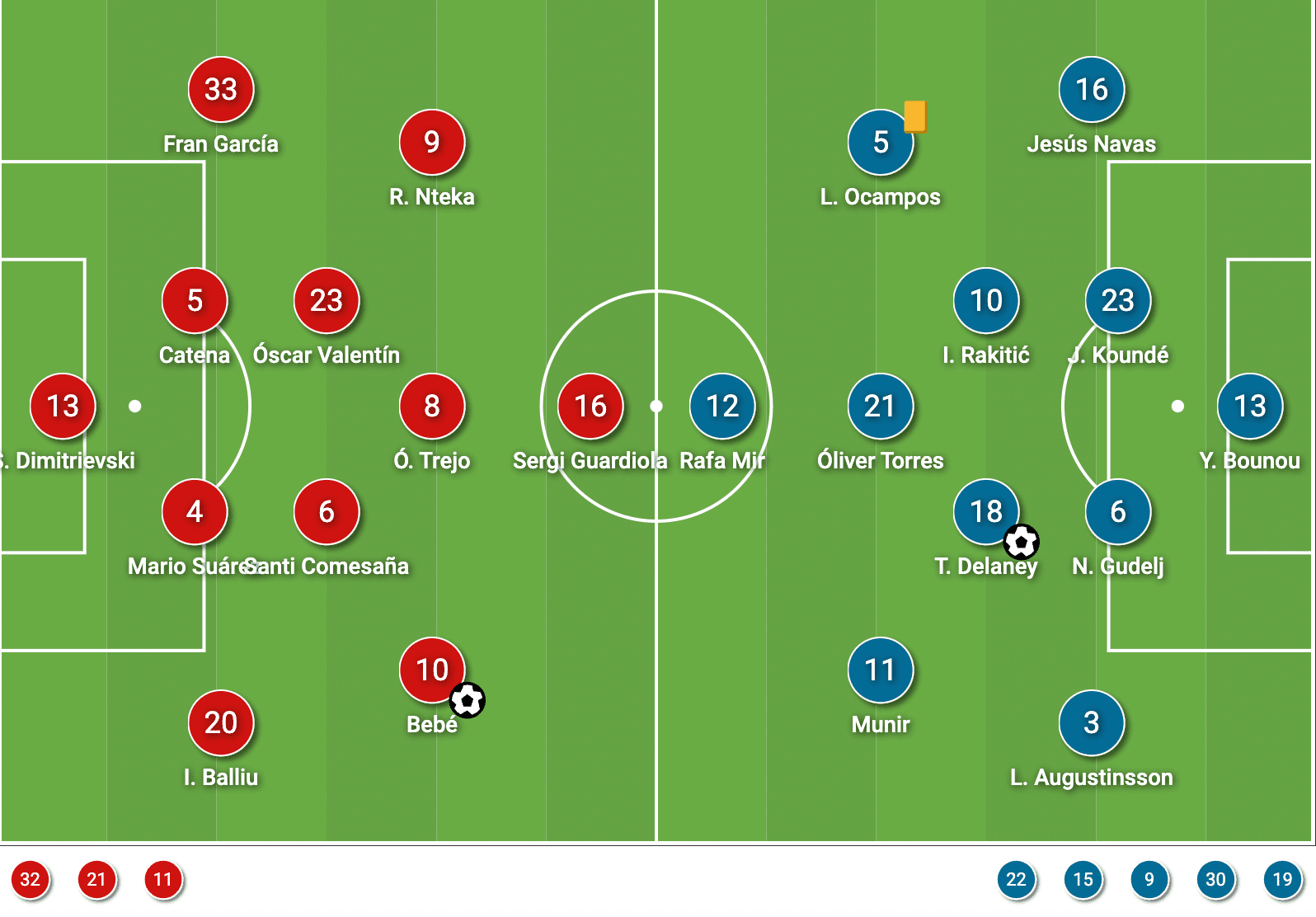

Lineups

Iraola’s Vallecano lined up in a 4-2-3-1 shape, but that could also become a 4-4-2 without possession when Óscar Trejo joined Sergj Guardiola in the first line. They had a few changes from the Cádiz loss, Luca Zidane, Esteban Saveljich, Álvaro García, and Isi Palazón made way for Stole Dimitrievski, Alejandro Catena, Randy Nteka, and Bebé.

Sevilla were missing Fernando Reges, Diego Carlos, Papu Gómez, and a few first team players, but they still managed to put a strong team in this game, although Nemanja Gudelj had to pair up with Jules Koundé as the centre-backs. Lopetegui also made some changes after the midweek victory, Ludwig Augsitnsson, Óliver Torres, and Rafa Mir, Thomas Delaney, and Ivan Rakitić were all fresh players who did not start against West Ham.

Ineffective Sevilla rotations

As usual, Sevilla’s game structure includes large scales of rotations in the offensive phases, and with many players dropping to the ball. They wanted to create numerical superiority to establish dominance with these rotations, but in this game, they almost never take the game to their own hand because something was missing in their attack.

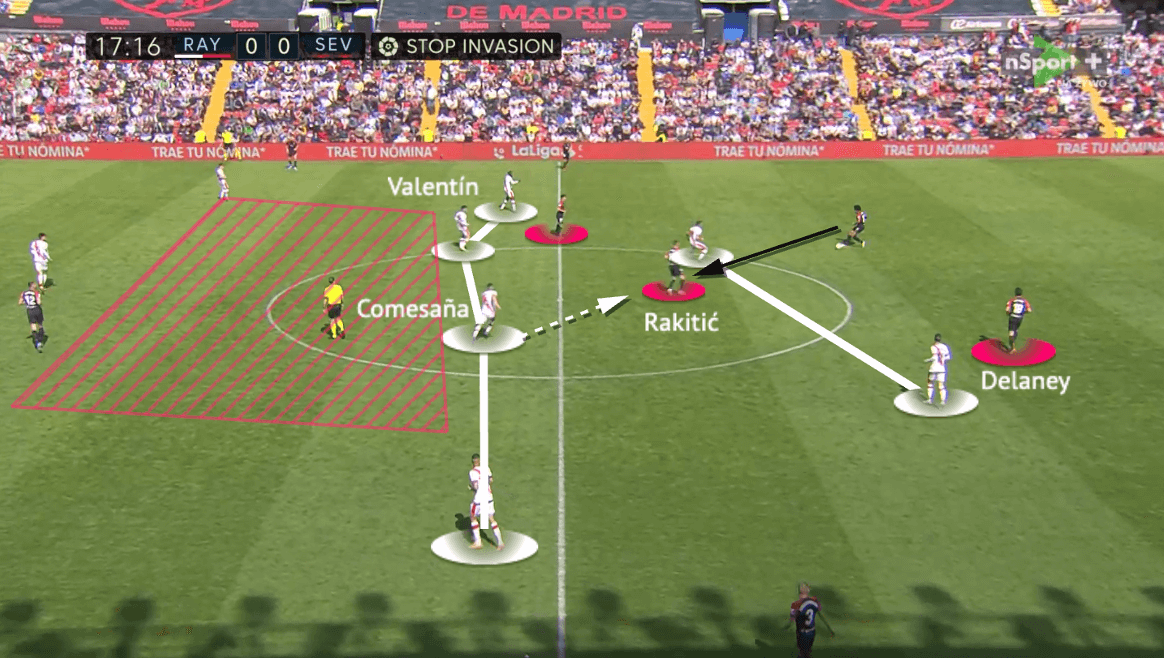

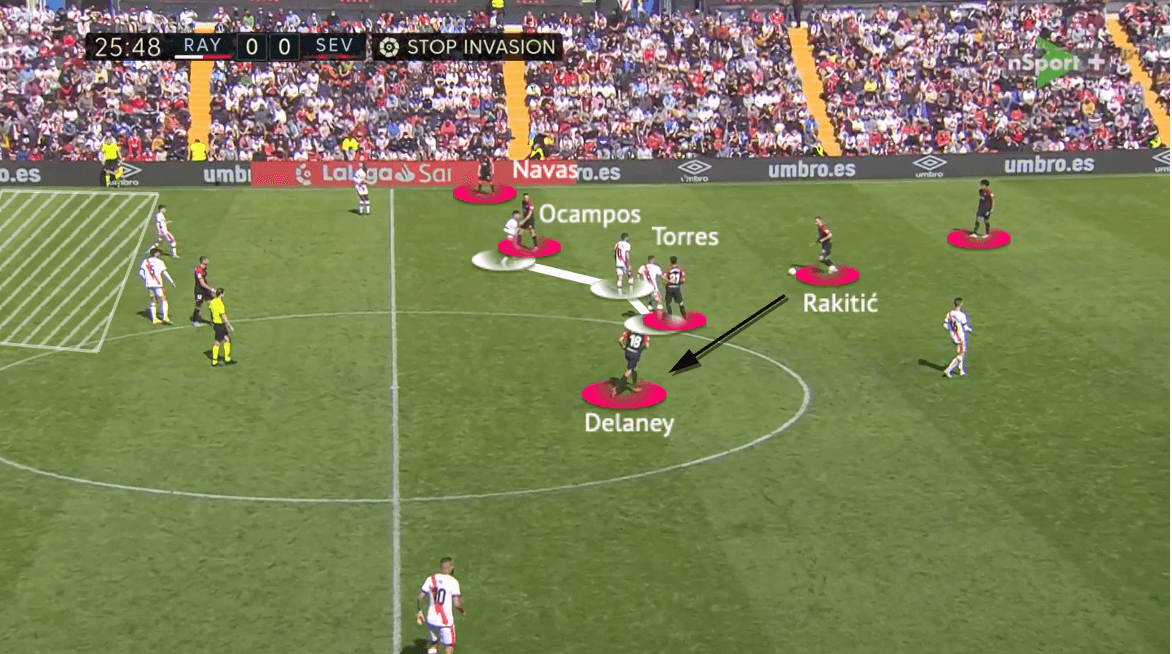

Since Sevilla players rotate and constantly adjusted their positions on the change, their attack could be dynamic when players from different positions move in and out and around the opponents. For example, Delaney always dropped to the first line in the construction phases, this created some sort of 3v2 overload against the Vallecano 4-4-2, allowing Koundé to play more in the right half-spaces.

But there was also a downside with when many players dropped deep, the team could lose its balance from a positional perspective. Since the opponents knew the Sevilla players have moved out, that means no one was behind, that gave them the confidence to step up to press and stick tight with the dropping players – this would make things difficult.

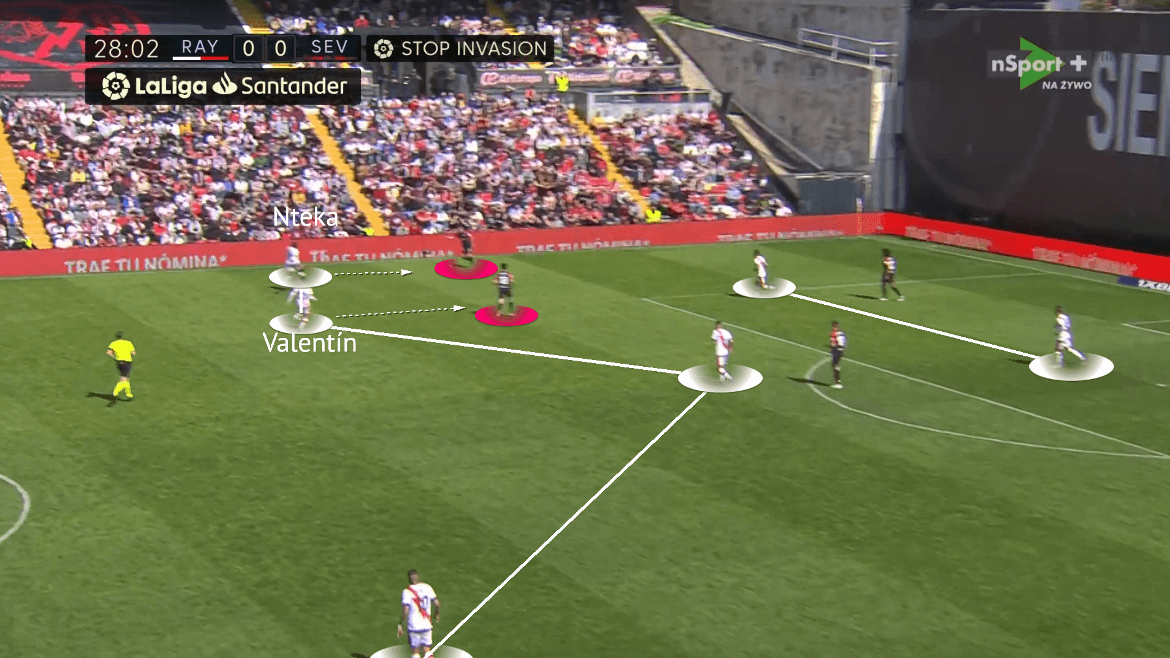

For example, Delaney dropped out in the above image, and Torres moved into the parallel zone with Rakitić. That means all Sevilla midfielders were in front of the Vallecano midfield line, so Santi Comesaña and Óscar Valentín could get on very tightly. Since the Sevilla midfielders were not the type of players who turned when that happened, they almost never beat the first line cleanly in the process.

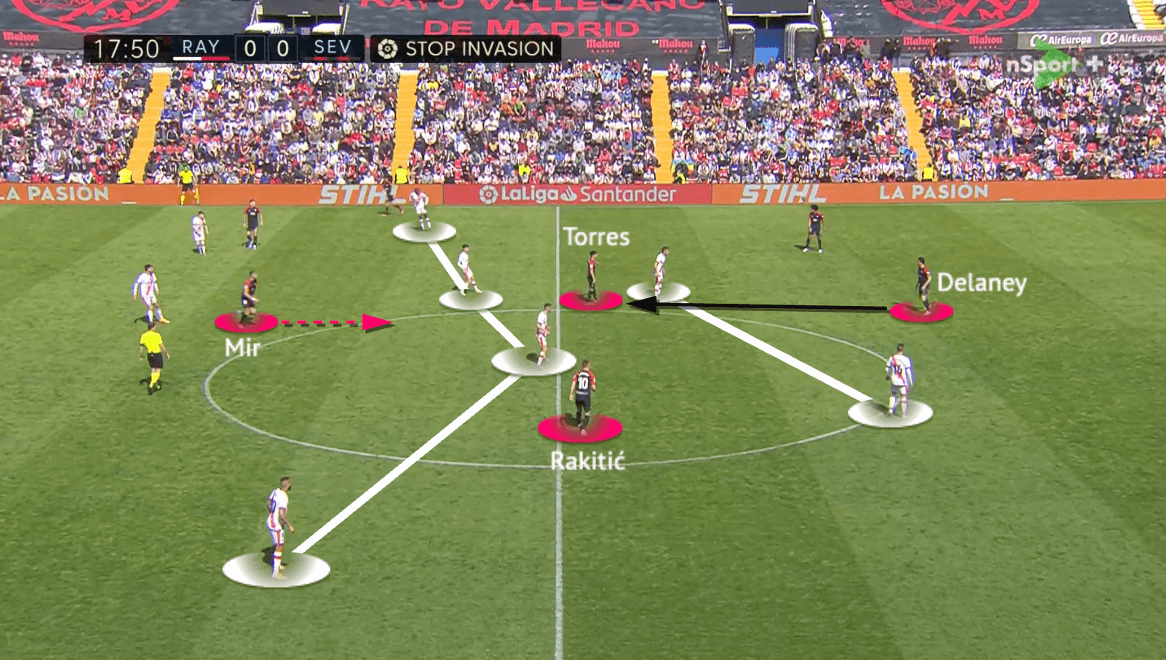

On a few occasions, the solution of the above problem could be offered by the striker dropping behind the Vallecano second line, as Mir did above to be the extra man in the midfield. However, things did not really work out well because they were also missing other elements in the attack.

In this game, the Sevilla wingers did not make correct decisions about when to go behind and when to drop in, that messed up the structure a bit and gave the opponents more confidence when Vallecano realized there was no threat behind at all. At the beginning, Catena and Mario Suárez might be conservative at stepping up, but they grew more aggressive as the game continued, knowing that the ball would not go behind.

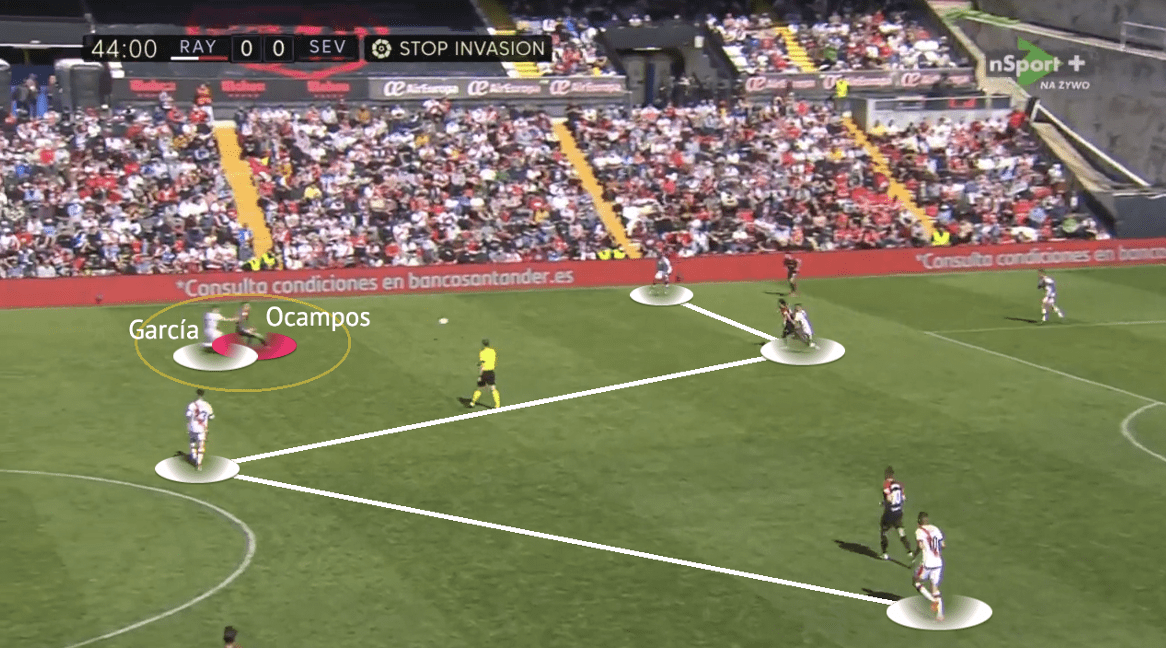

In the above screenshot, when Mir dropped, Ocampos (RW) was rather static and that would not help the attack.

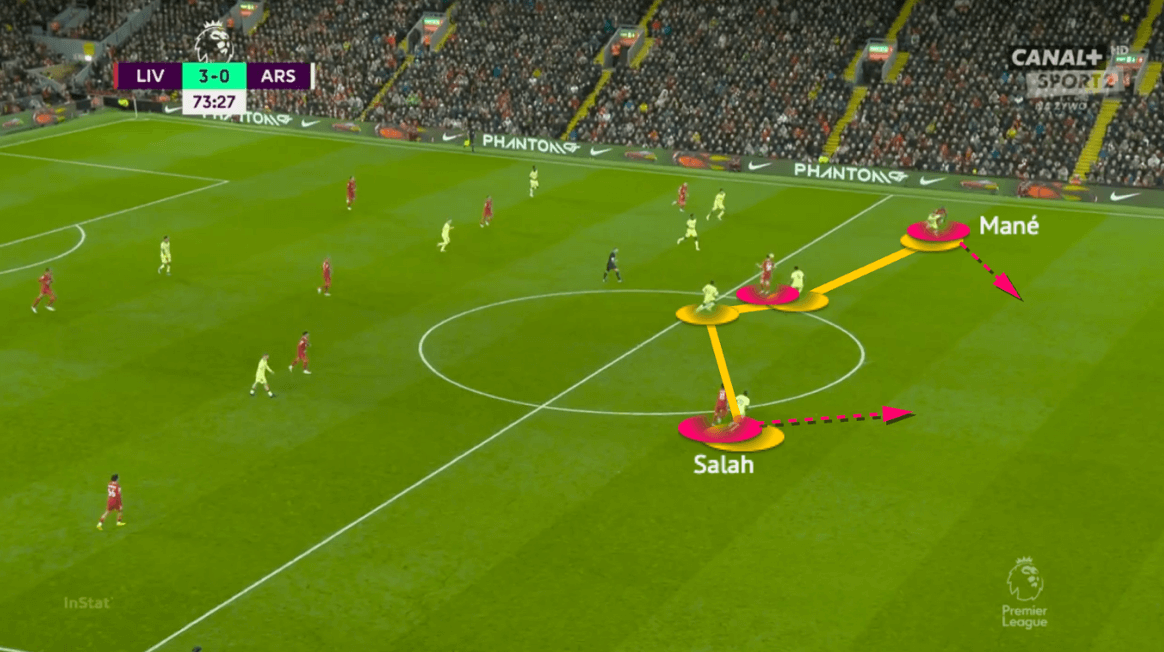

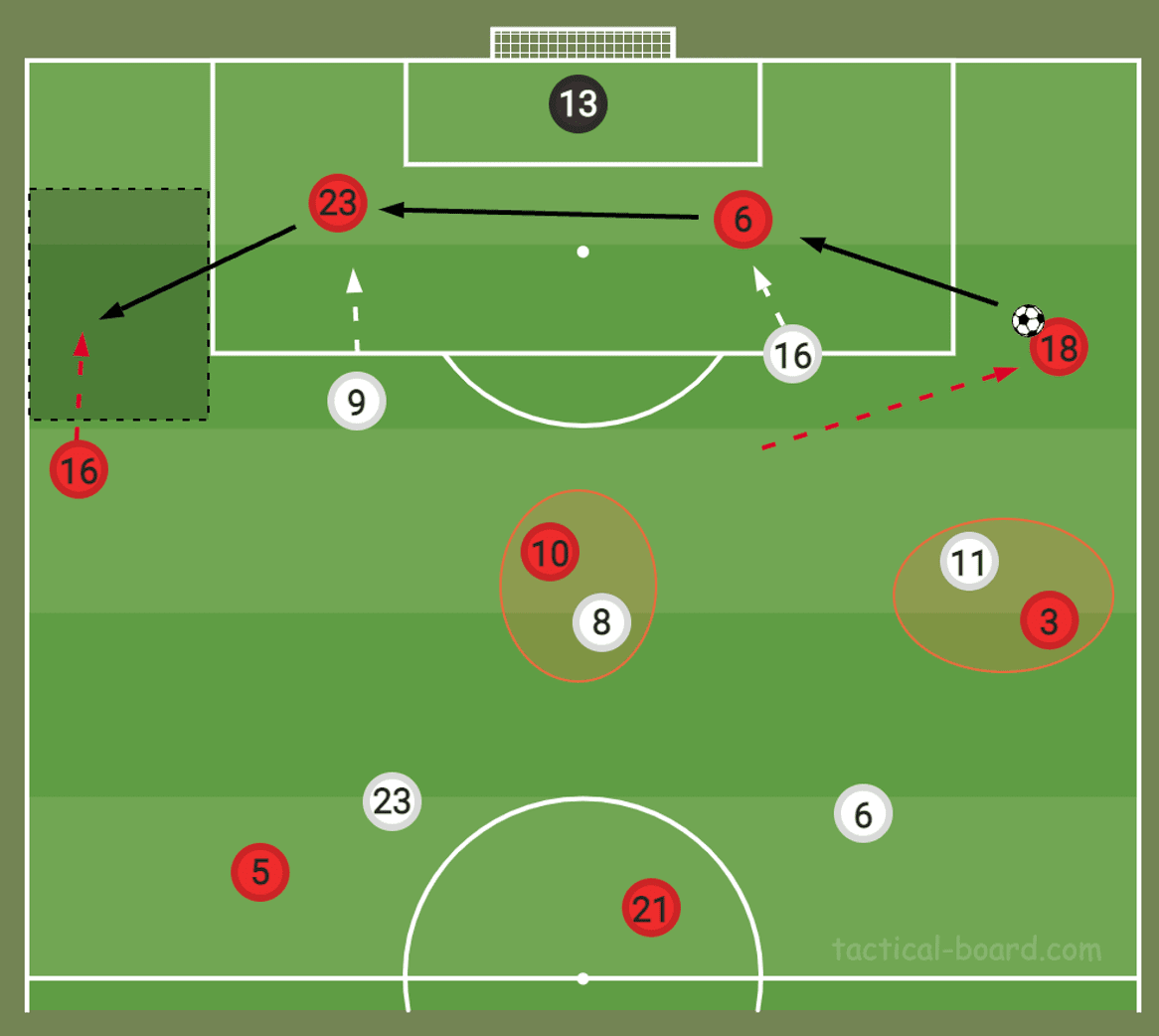

When talking about the false-9 role, Liverpool are one of the best team with this tactic. We take a goal of Jürgen Klopp’s side against Arsenal as a reference to show the differences between Sevilla wingers and Liverpool wingers.

Here, in the above picture, when the false-9 dropped into the midfield and pulled the centre-backs out of position, you could see Mohamed Salah and Sadio Mané coordinate by going behind diagonally into spaces behind the centre-backs. With their good pace to beat the full-backs, they arrived to exploit that space to create the goal.

By contrast, Munir El Haddadi and Ocampos did not make the same run as Salah and Mané did above to penetrate the defence. Even they tried to receive behind, the forward runs were not well-timed or not going to the right direction.

On a few occasions, Sevilla managed to reach the free player in the midfield, but their passes after beating the first line were very disappointing. Torres got a few chances to progress the attack, but his long passes were not doing any harm since Sevilla did not have presence behind in the right timing.

In the above situation, it was Delaney who became the free player to play the forward pass, but you could also note Ocampos’ position, he was deep, Jesús Navas was deep. Sevilla were had a bunch of players crowding in the midfield but there was no one posing threat in spaces behind, or in spaces between the lines.

Vallecano’s amazing press

We mentioned the rotations of Sevilla were missing a few details in the above analysis, but that was not the only reason to explain the record-lowest shot figure in the season. In fact, Iraola’s men did really well without possession, they ran and ran relentlessly to keep the intensity until the last minute, keeping the press and avoiding falling into a low block. They also adapted to the Sevilla rotations to minimize their threats.

In the build-up, Sevilla were actually doing okay in the first period of the game. There were a few occasions which Koundé solved the press very well with his individual skillsets, allowing his side to bypass the 4-2-3-1 pressing.

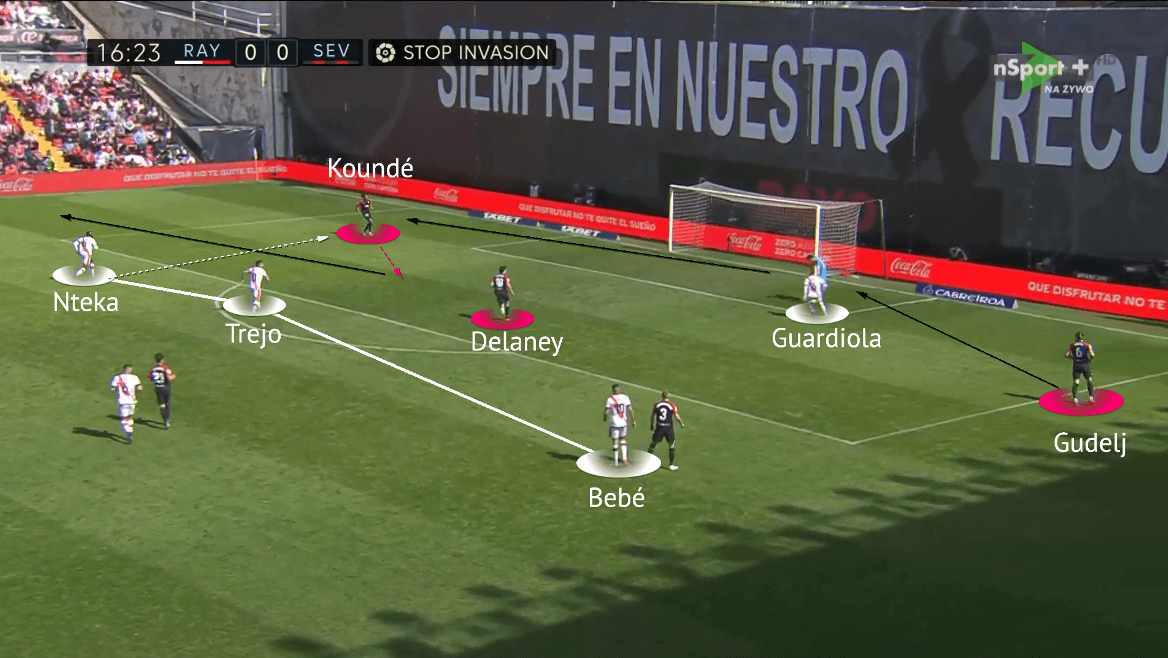

The above image demonstrates the situation. Sevilla had Delaney very deep to fix Trejo in the centre, then, they use Bono to circulate the attack from side to side. In this Vallecano 4-2-3-1 press, Nteka would go for Koundé vertically, but he was not accessing the Sevilla centre-back and let him escape.

The above screenshot would give us a better picture of why that could be a problem in Vallecano’s pressing. If the left-winger in a 4-2-3-1 pressed Koundé, and let him escape, there was one closing down the dropping player in the dark zone. García could not jump out that far because Ocampos was around, and Valentín was not expected to move away from the centre to press a deep full-back out wide. Meanwhile, since Sevilla had players fixing Trejo in the centre, there was no one to stop Navas when Koundé solved Nteka’s pressing. Of course, Vallecano wingers were disciplined to fall back immediately after Sevilla advanced the attack, but tactically it was not optimal because the opponent had a clear solution to beat the press.

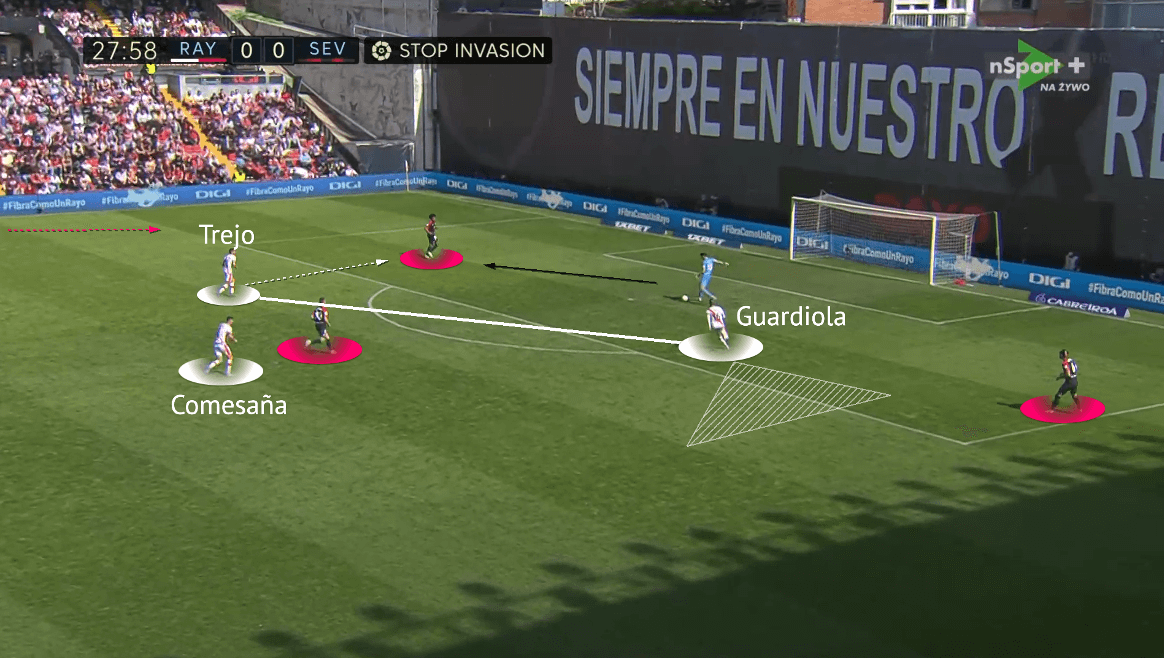

But very quickly, Vallecano adapted to the opponents and slightly adjusted the pressing shape, shifting from a 4-2-3-1 to a 4-4-2. So, Guardiola could still lead the press by pressing from one side laterally, forcing the opponent to go one side to the other and block the circulation route. Then, it was NOT the left-winger jumping out to press Koundé, instead, it was Trejo, the 10’s job to do it. Then, to pick up the deep Sevilla midfielder such as Rakitić, Comesaña moved up to close him. The Vallecano 6s were more often spreading in alternative horizontal zones as Valentín was deeper to cover. You could interpret it as a 4-1-3-2 conceptually if that represented the situation better.

Of course, as shown in the above image, Koundé could still make that pass to outside even though Trejo was pressing him.

But there was a difference if the left-winger was deeper initially. Sevilla could drop with different players in that outside space of Koundé, but Nteka would be waiting for that, the above screenshot was one of the scenarios. Hence, Vallecano had good controls in that zone and on that dropping player, and they could put pressure on the receiver whenever that pass was made.

In case Sevilla had another dropping player, such as Navas in the centre to support here, Valentín, the covering midfielder would jump out to cover, knowing that the opponents could not loft the ball to Mir in those situations.

Most of the Vallecano problems were on Koundé’s side because the Sevilla centre-back was really good and comfortable on the ball, but Iraola’s defenders were doing enough to close spaces and handle different situations.

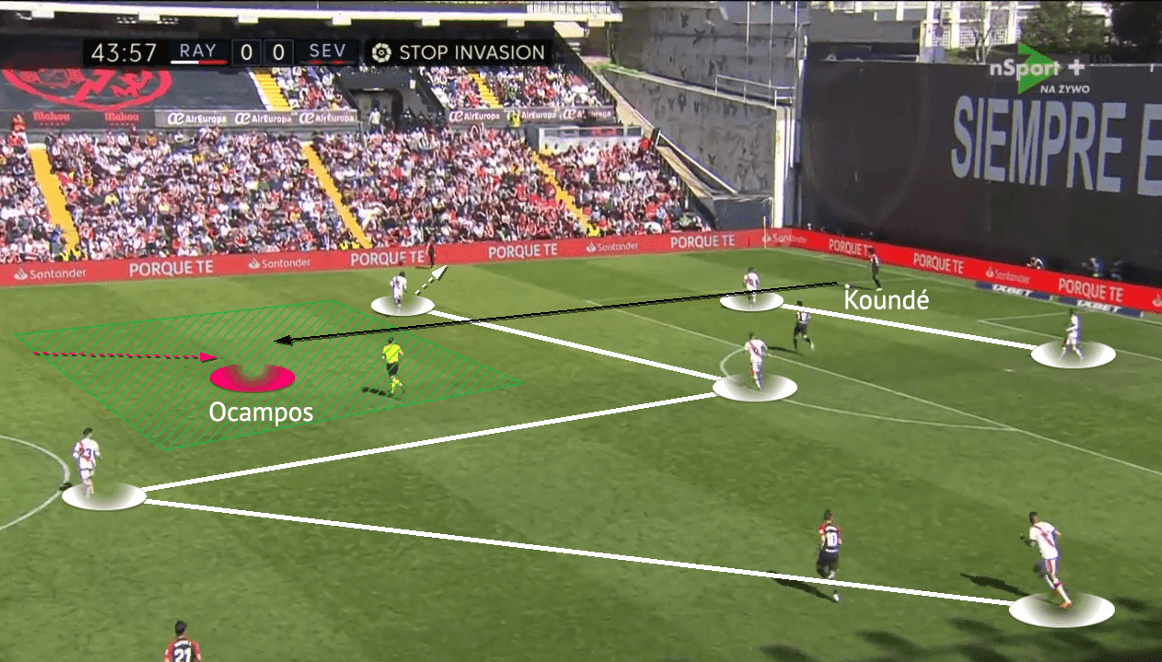

The above image shows an alternative solution of Koundé, that’s something a top-class defender could do, adapt the game and raise different questions to the opponents. This time, the Frenchman defenders spot Nteka was dragged away by the wide players early, and that gap between Nteka and Trejo was a clear vertical passing lane because Delaney invited the Vallecano 10 to press high as well. Then, Sevilla had Ocampos dropping deep into green spaces to receive.

But Sevilla almost never beat the first line cleanly, and they suffered when the first pass went out. Vallecano were so aggressive and they never let the opponents receiving with spaces to turn or do something. Here, when Ocampos dropped, he could not get rid of García, and he could not even turn in this situation.

The relentless efforts of Vallecano should be given huge credits because they kept the pressing intensity until the last kick of the game and Sevilla never take control. It was even more impressive as players with Guardiola (30) and Trejo’s (33) age were also able to run in most of the game.

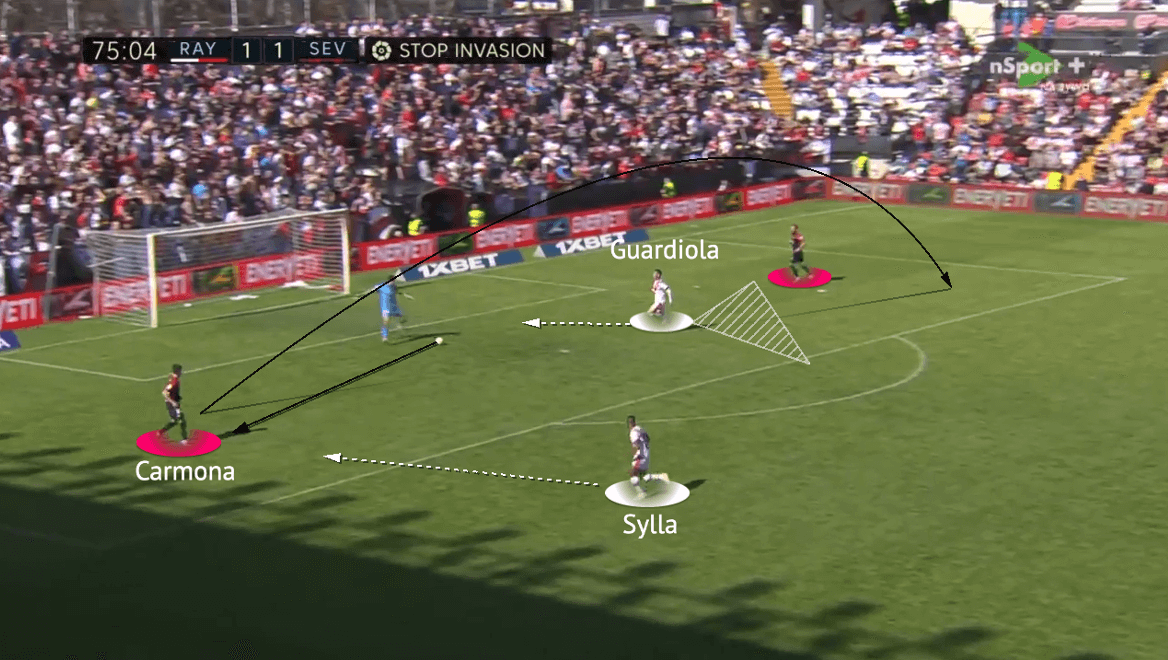

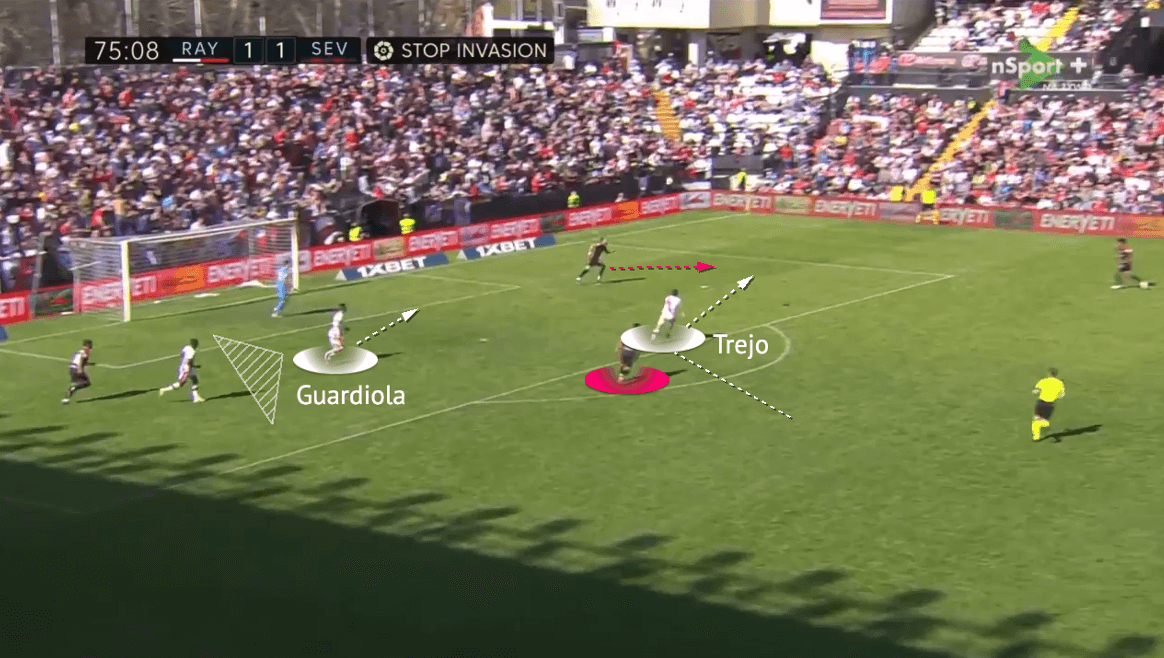

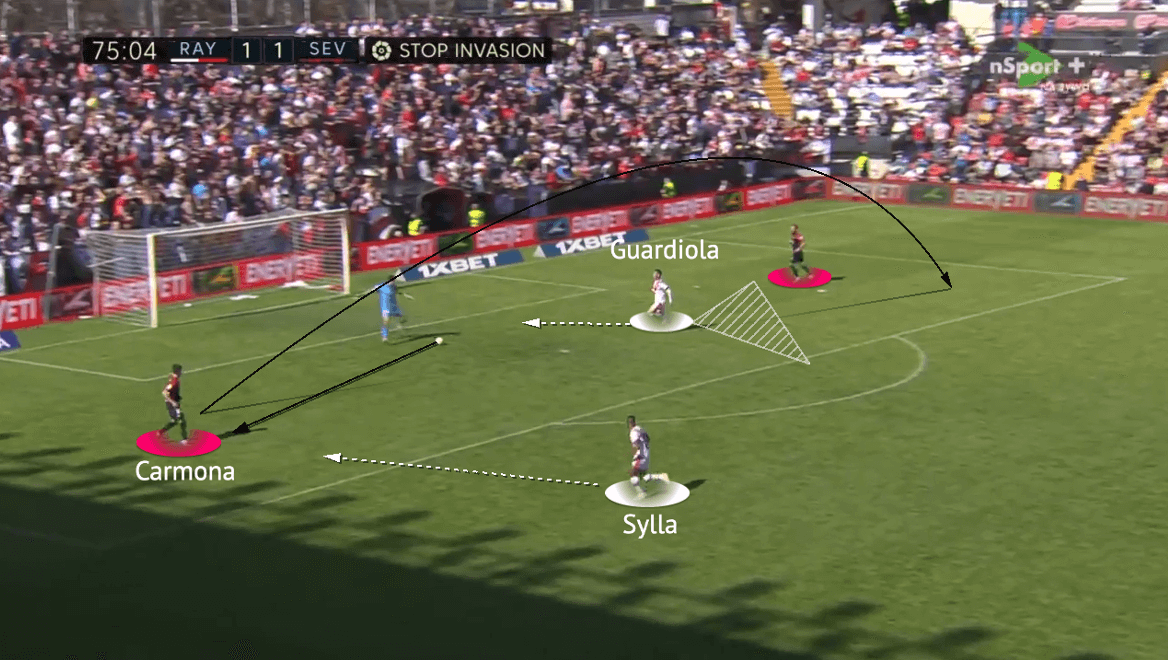

This example is from the last period of the game, Sevilla already switched to a back three by that time, but Vallecano kept pushing and pushing as Guardiola pressed laterally to force them play. Then, when the pass went to José Carmona, Mamadou Sylla jumped out to press continuously.

Then, you could see the incredible pressing. As Trejo marked the dropping midfielder, he was also high in the press, after Carmona switched with an inaccurate lofted pass, the Vallecano skipper went all the way, and Guardiola already went back to block the central passing lane again. And Vallecano actually had a turnover inside the Sevilla box, this was how Iraola’s men generate threat by counter-attacks in high areas.

Conclusion

As we have shown in this analysis, the stalemate of this game was a result of Sevilla’s ineffective positional structure and Vallecano’s good pressing. As inspired by Marcelo Bielsa, Iraola’s side also had very high pressing intensity and the relentless runs they made without the ball was key. They did not give the opponent chances to dictate throughout the game. However, the result was cruel, because they were still fighting for the first La Liga win in 2022.

Comments