Lazio are coming off the back of a last-minute equaliser scored by goalkeeper Ivan Provedel in the UEFA Champions League group stage opener against Atletico Madrid. Although the goal came from a second phase during a corner kick, Lazio have been underwhelming from corners since Maurizio Sarri’s arrival at Stadio Olimpico. Since the start of the 21/22 season, Lazio have only scored 11 goals from corners, averaging five a year, and a large portion of the blame lies in their stubborn attitude, using the same two routines in each game, at least in recent memory. While the corners have some clear intentions behind them, neither routine is highly effective, and relying on something unreliable leads to unsurprising results.

In this tactical analysis, we will look into the tactics behind Lazio’s offensive corners, with an in-depth analysis of how their main two corner routines have been used. This set-piece analysis will examine why these routines have had some bright signs, why it hasn’t been effective, and the steps Lazio can take to become more threatening from set plays.

In Swinging Routine

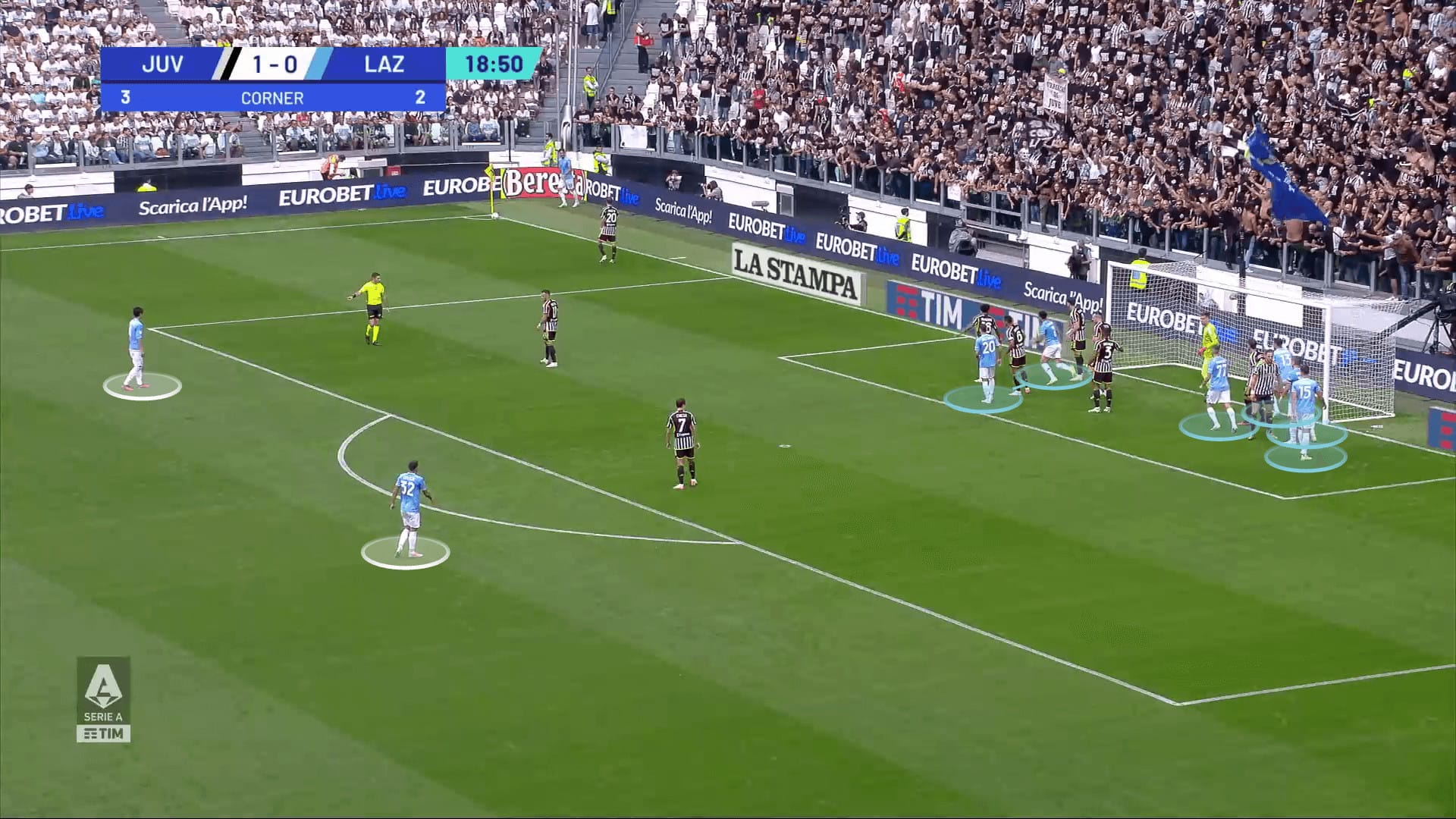

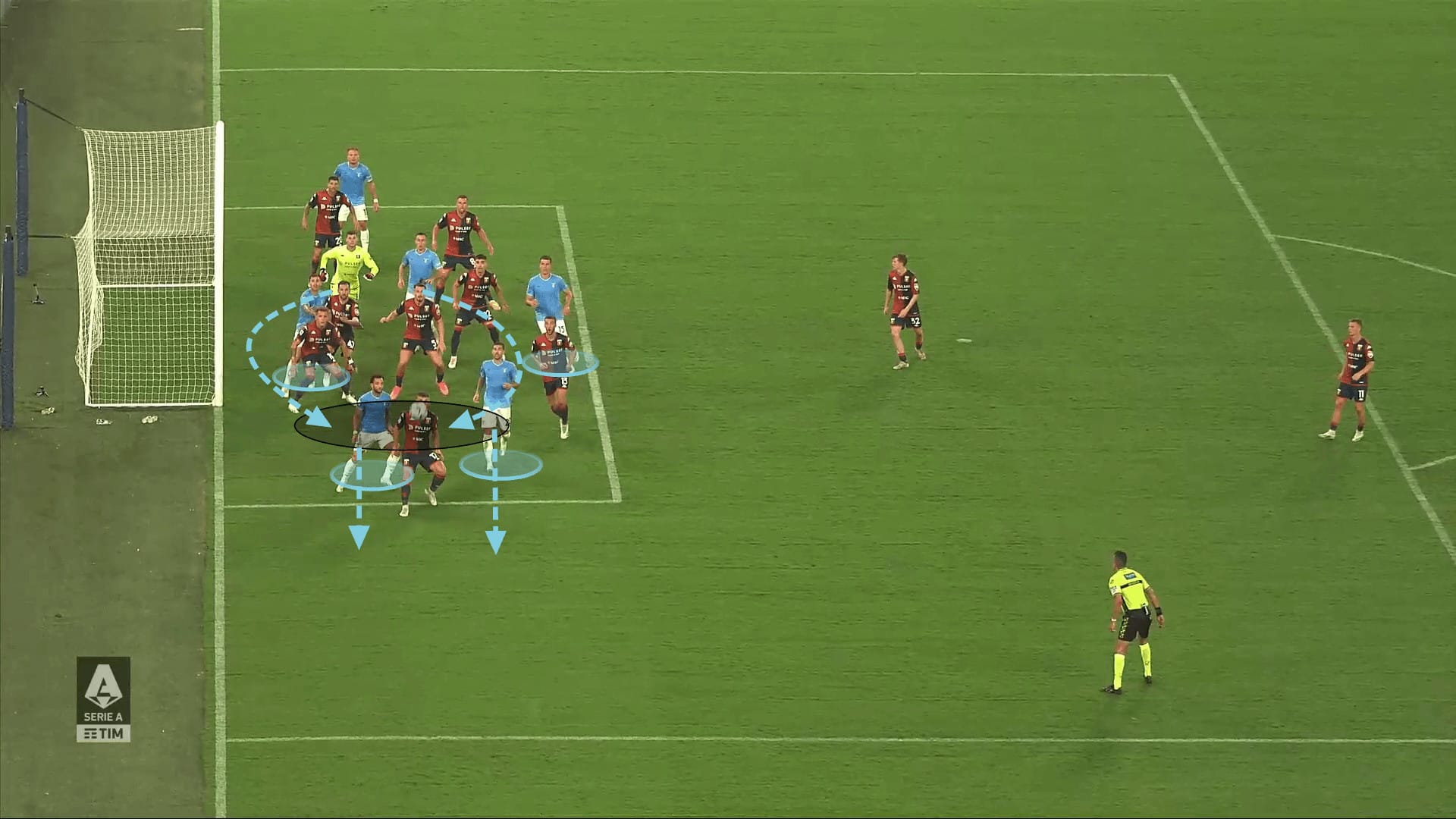

With corners won on the left-hand side, Lazio’s only routine they have utilised has involved the crowding of the six-yard box. As seen in the picture below, two attackers start by the front post; two are located just behind the goalkeeper, while the other two start by the back post. Two players are left on the edge of the box, whilst one player sits deeper, near the halfway line.

From this starting position, we can see each player’s runs pictured below. The two attackers at the front post make decoy runs towards the ball in order to drag their markers away from the front post, which is the primary target. The two attackers start by the goalkeeper and make curved runs into the space vacated at the front post. The run starting from behind the defender’s shoulder means that the Lazio attackers are able to move without being spotted over their first steps, so they can accelerate into the space without the defenders being able to stay tight to the runners.

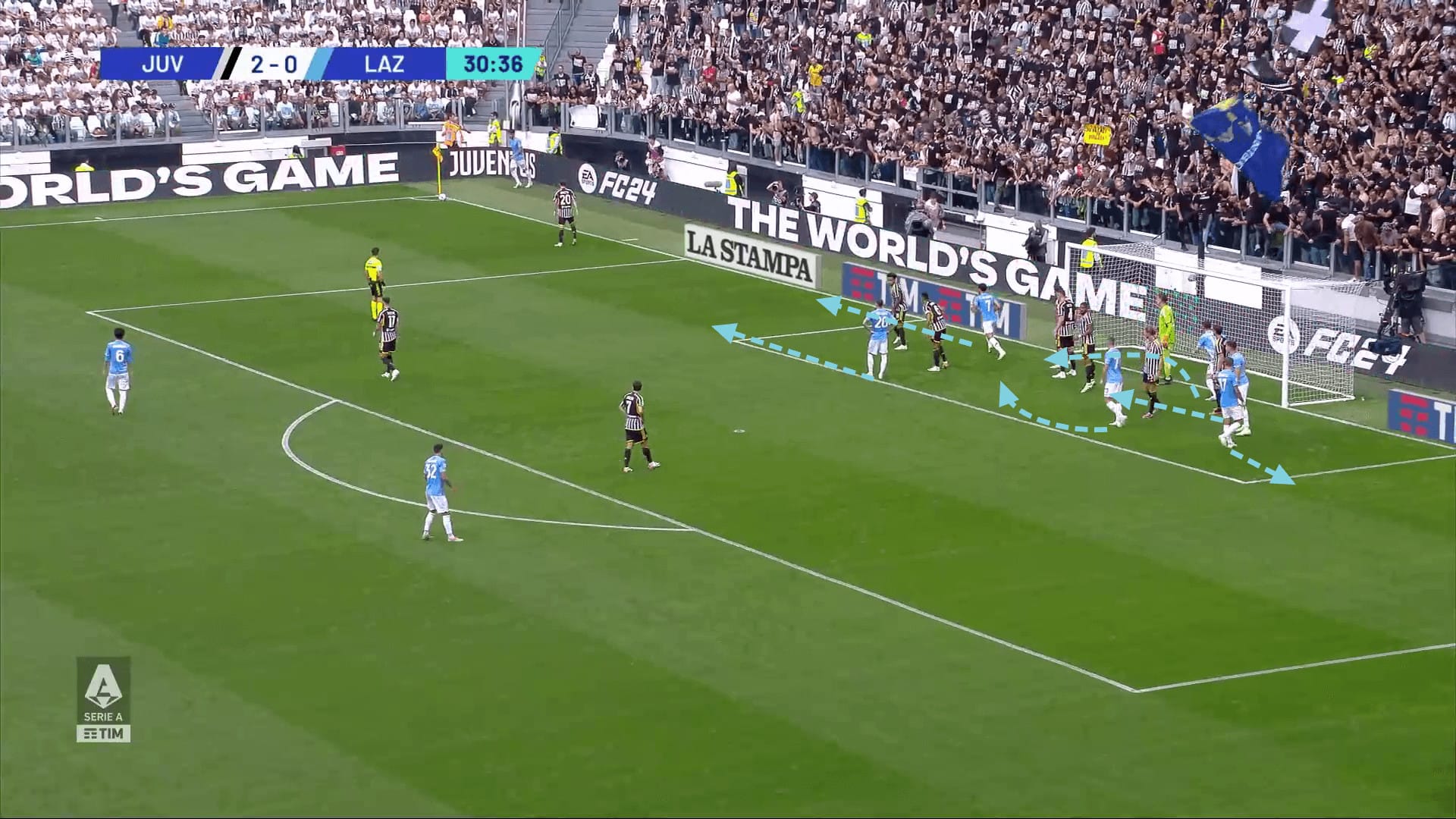

From the alternate angle, the space made by the decoy runs can be seen inside the shaded area, where the defenders have followed the attackers away from the six-yard box. The deeper attackers, who attempt to attack the space at the front post, curve their runs to minimise the chance of their runs being blocked by running through open spaces, whether inside the goal or around the six-yard line.

The angle of the run isn’t too relevant with these two players, as their only role is to redirect the ball towards the goal, and power on the header isn’t necessary as the header will be attempted from fewer than six yards. Obviously, attacking a header from a wider position would be more beneficial, with the attacker being able to see the goal whilst attacking the ball, but the close proximity of the header to the goal means that the attackers already have a good idea of where the goal is in relation to their position.

Lazio always leaves one player at the back post who can sweep up any ball. Whether a corner is overhit or missed by the attackers by the front post, the player at the back is always there to put the ball back across the box to give the attackers a second chance at heading the ball. This player at the back post can also get onto the end of rebounds or any sort of second balls that may land in his area.

Problems and Solution’s against the Zonal Defending System

The problem with crowding the six-yard box with attackers is that it invites opposition teams to use heavy zonal defending systems, as the only threat is in the six-yard box. Also, only using one routine for every corner from the left-hand side allows teams to predict what will happen and change their defensive setup to counter Lazio’s routine. As we know, Lazio attempt to attack the space at the front post, and so does any opposition team.

To combat this, opposite teams can crowd the front post area so that even if a player follows a decoy run away from that area, numerous players are still in that zone, ready to clear the ball. With three zonal defenders, it becomes tricky for any attacker to find space in that area. If a corner is delivered with more power, towards the further side of the six-yard box, the goalkeeper is ready and off his line, waiting to claim the lofted cross.

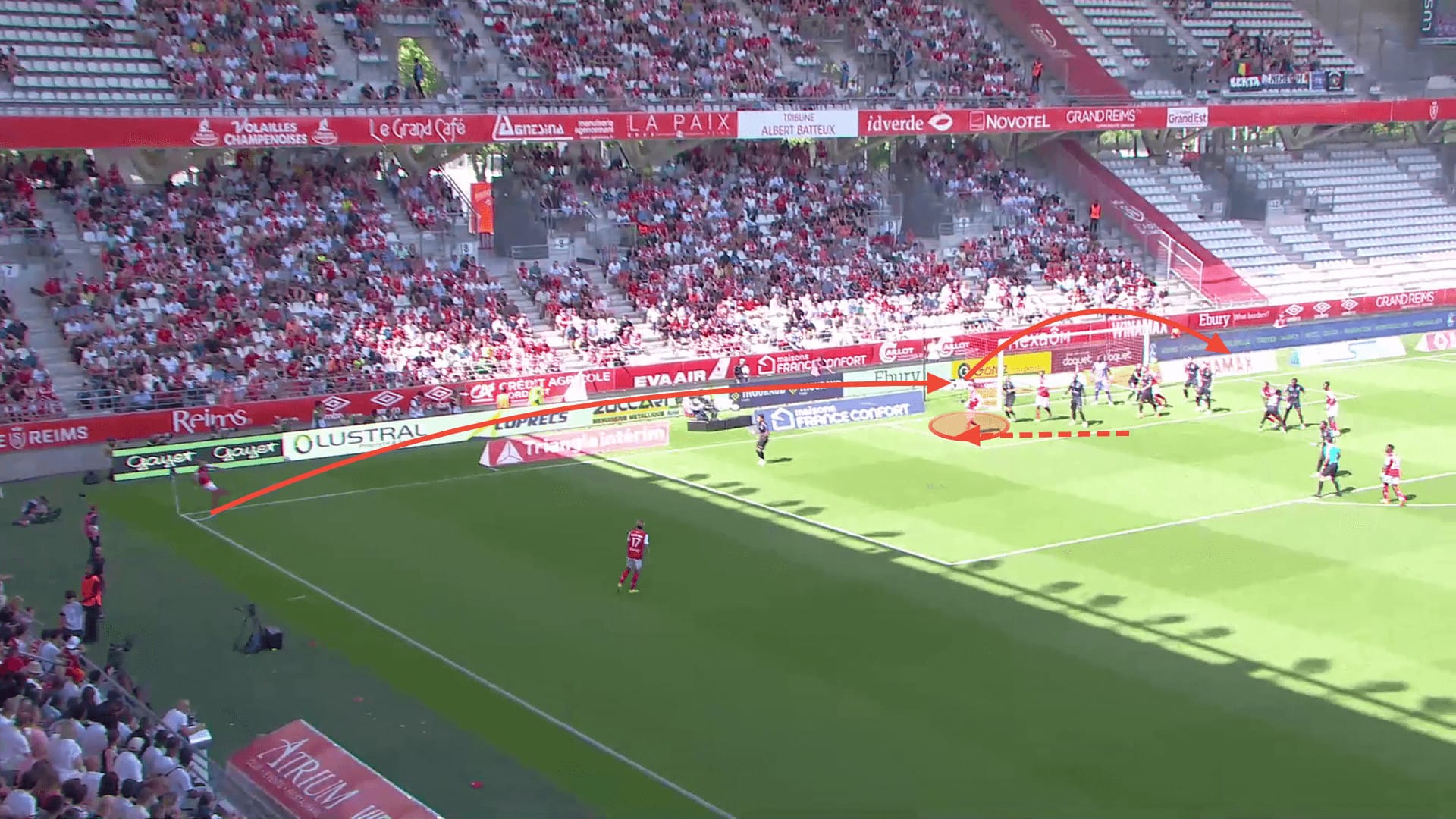

There are several ways in which Lazio could vary their routine, to appear as if they will do what they usually do, but alter their routine as the corner is taken. One variation Lazio can use is inspired by Stade Reims, who uses flick-ons to move the zonal block and create chances on the second ball.

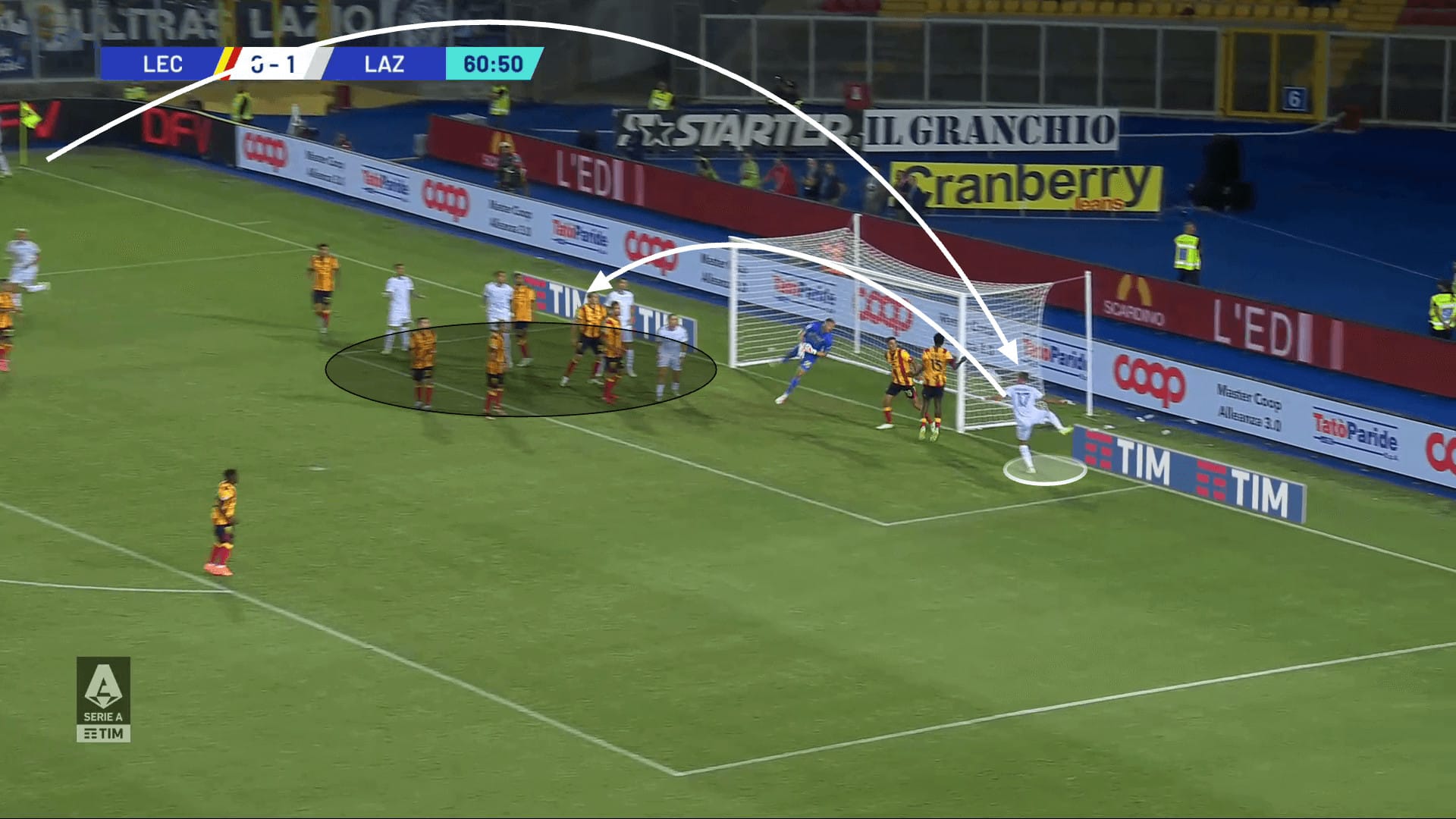

As seen in the image below, a decoy runner away from the six-yard box is used just like Lazio does. With this similarity, Lazio can use variations whilst seeming like they will do their usual routines, which can fool opposing teams into a false sense of security.

With the corner aimed at the usual decoy runner, the player has more space to perform the flick-on as his role usually doesn’t involve attacking the ball, so defenders have less urgency to track the run. The entire zonal block naturally moves towards the ball as the ball is crossed short, which creates additional space at the back side of the six-yard box, where a runner from deep could attack the space unmarked.

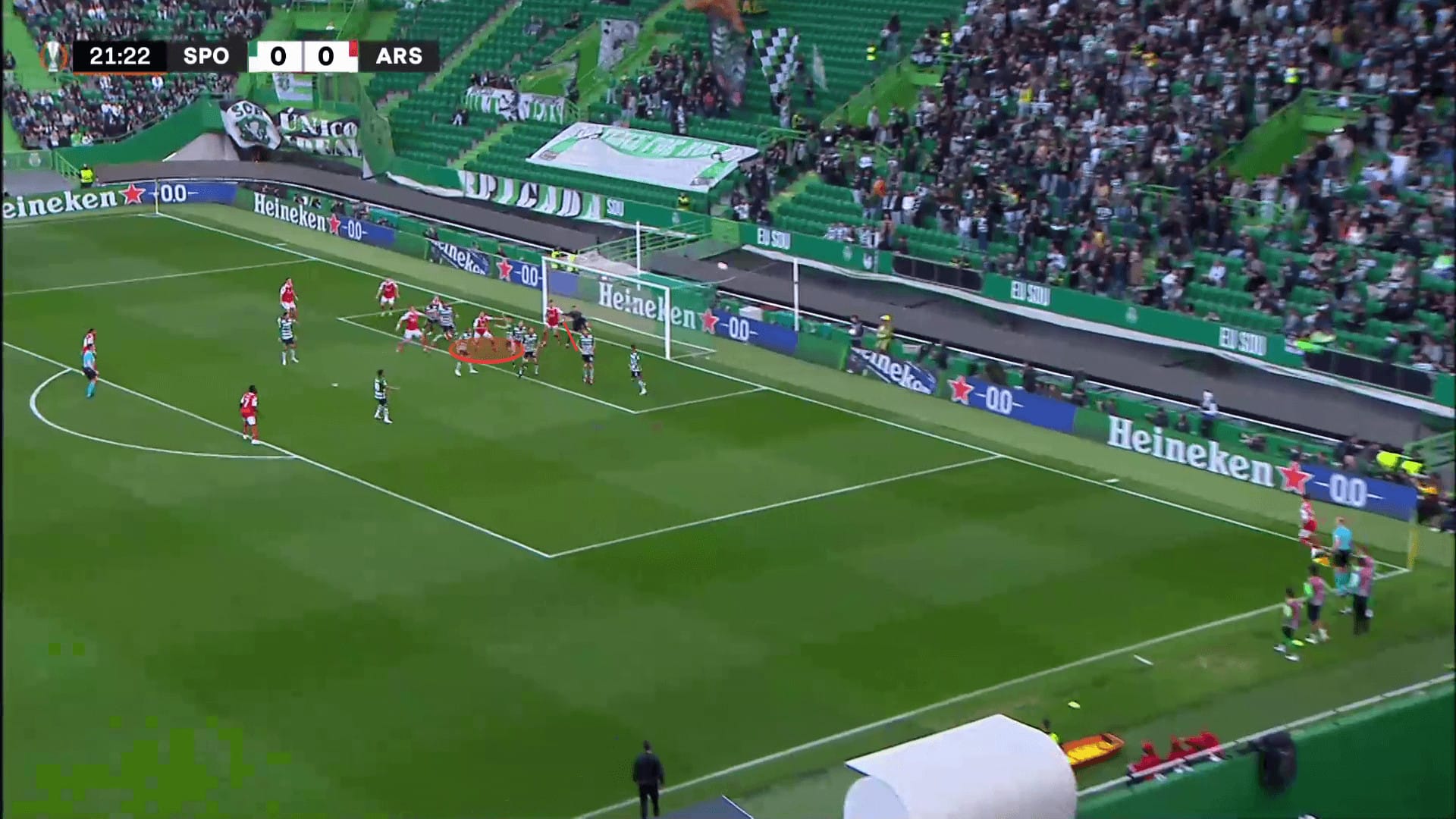

Another side Lazio can take inspiration from is Arsenal, who also crowd the six-yard box with the starting positions. To give the player attacking the space at the front post additional space, Arsenal utilise two screens on the zonal defenders, preventing them from being able to step up and clear the ball. The only task for the corner taker is to deliver the ball over the first zonal defender, and the attacker doesn’t have to worry about a defender coming up behind him to compete for the aerial duel.

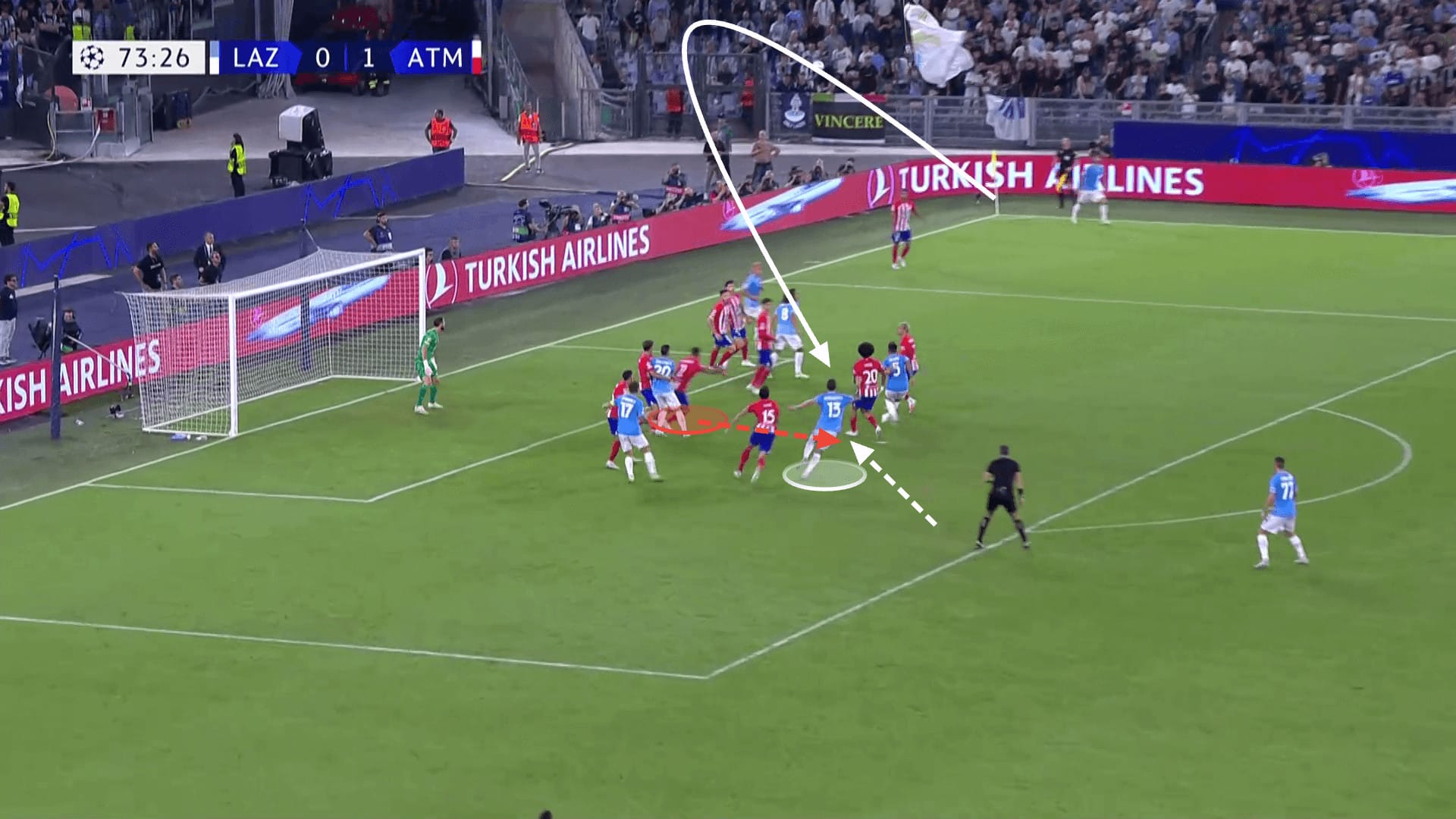

Another way it is possible to vary the routine is by blocking the keeper to prevent him from coming off of his line. Stopping the goalkeeper means the ball can be delivered into the six-yard box and to an area nearer the back post.

Although in the example, there is no clear space or advantage for the attacker, having the ball land so close to the goal means that the attackers do not need a significant advantage in the aerial duel, as power on the header isn’t vital.

This routine leaves the defender and attacker with a 50/50 duel, where an attacker with a strong aerial presence only has to get a small contact on the ball to redirect it to the goal, with the goalkeeper having no time to react to the shot.

Out Swinging Routine

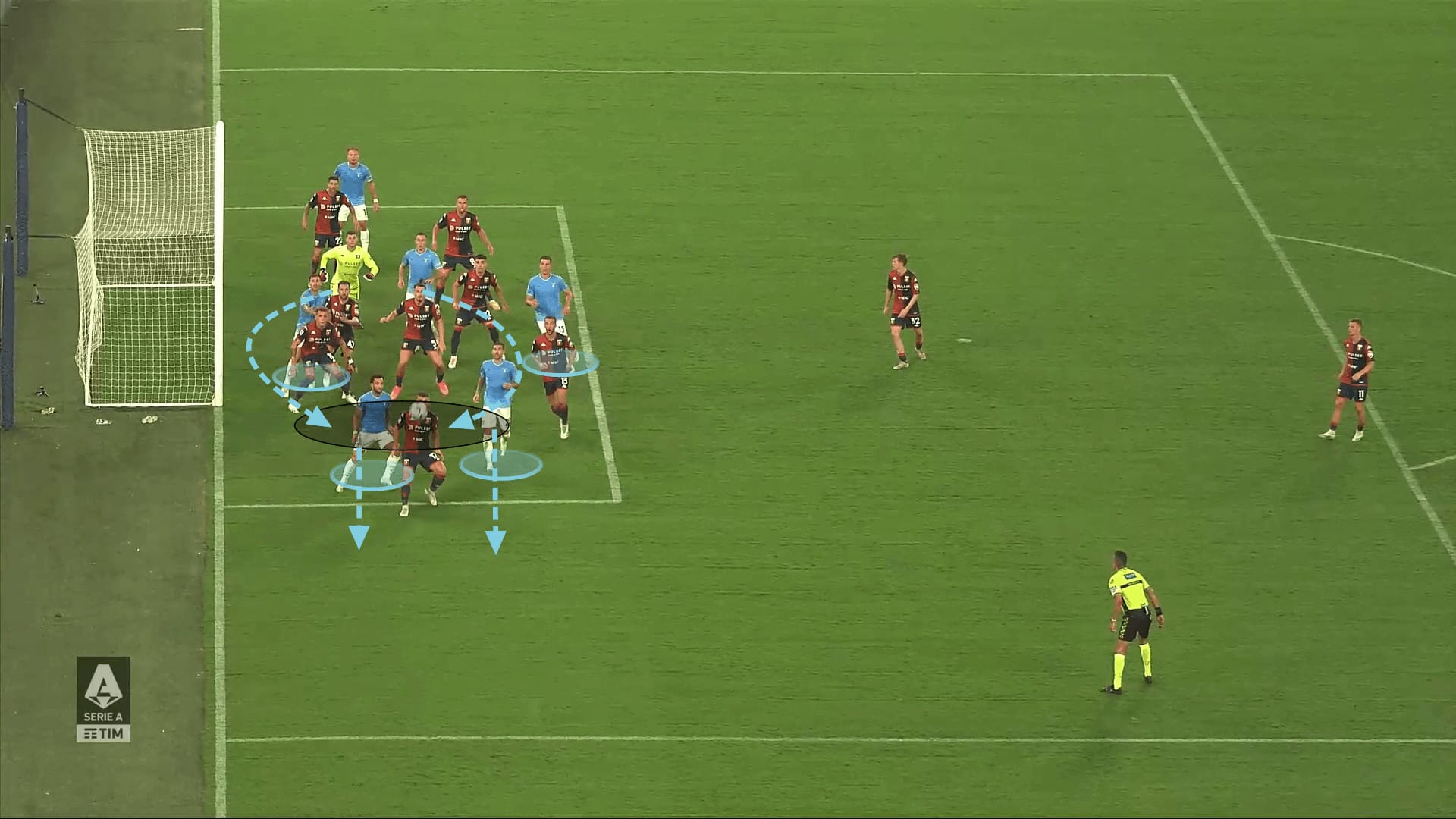

Lazio uses an entirely different yet similarly stubborn routine from the right-hand side. They employ around four or five attackers in a deeper position, ready to attack the ball around the penalty spot, whilst one player screens a zonal defender on the six-yard line. This method can reliably lead to chance creation.

However, consistency in the corner delivery into a tiny and precise area just in front of the screen is necessary for this to work. This precision leaves unrealistic expectations on Luis Alberto, as the margin for error is minimal in this current setup.

Flaws of the System

One issue with this setup is that any corner aimed towards the near side of the six-yard box, or any corner delivered in flat, will be cleared by near-side zonal defenders. No screen on the close zonal defender means that Luis Alberto is forced into making a higher, looped cross towards the penalty spot.

However, the issue that comes with the looped cross is that it gives time for zonal defenders to vacate their position to attack the ball. With only one screen on a zonal marker, multiple other zonal defenders have plenty of time and space to attack the cross, even if it is far from their starting position, due to the trajectory of the cross. For this routine to work, the cross must be delivered as flat as possible whilst clearing the first zonal defenders to prevent the deeper defenders from having time to attack the ball.

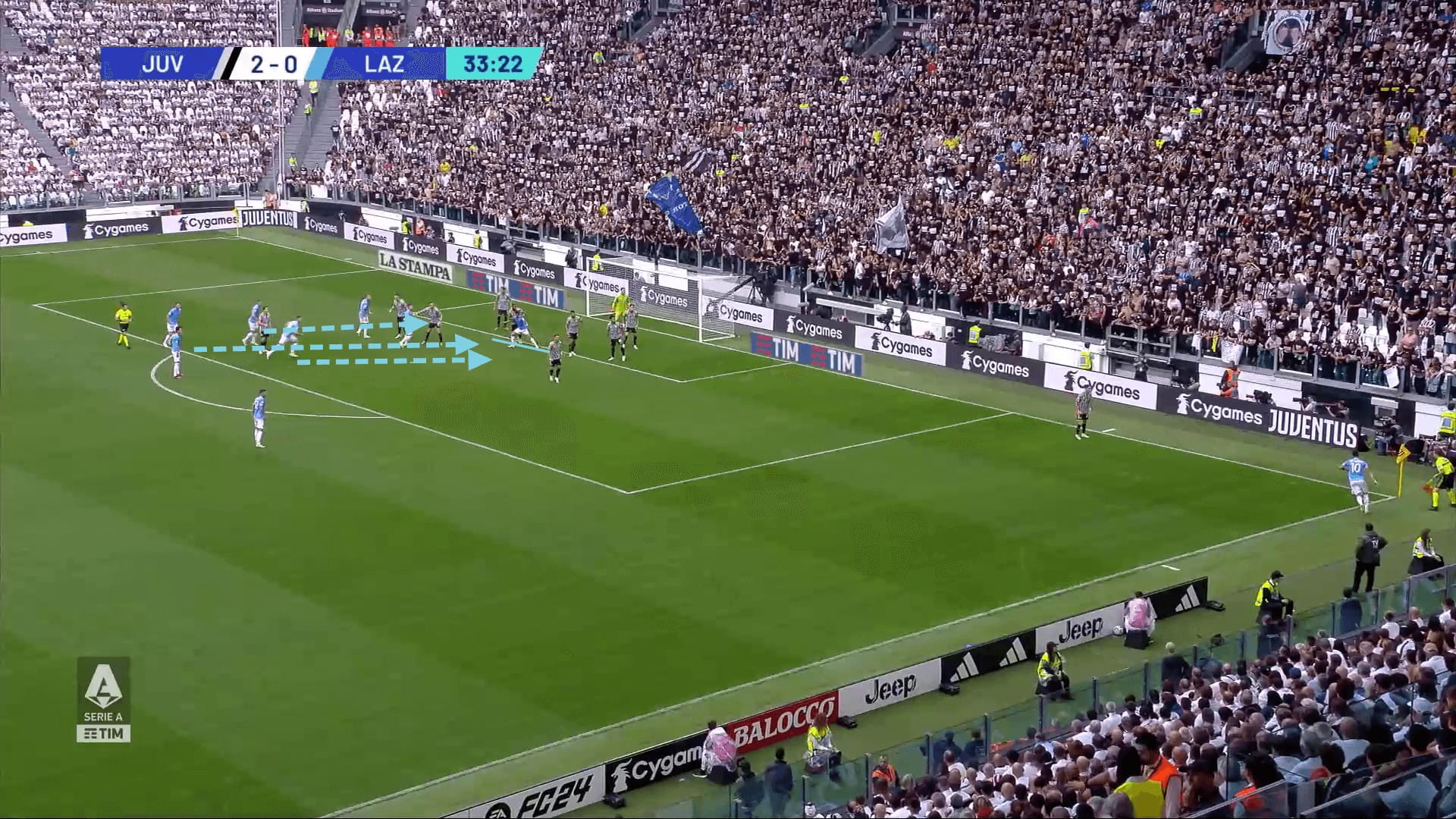

One final issue with the routine used is the lack of collaboration in the attacker’s movements. The player highlighted in blue is the target for the corner, but the image below shows him competing in an aerial duel with three opposition defenders. The players highlighted in white can be seen having a clear role, with one player performing a screen on the zonal defender and one attacker covering the back post for rebounds.

However, the issue is that three attackers are highlighted in grey, whose roles are nearly irrelevant. These three players attack different parts of the box or attempt to drag defenders away; however, with Lazio’s corner being so similar each week, they know it is doubtful the ball will be delivered anywhere else but the penalty spot.

As a result, they are creating space in areas that won’t be attacked. Lazio would be better off giving each of these three players a clear role to increase the time and space the real target player has to shoot the ball.

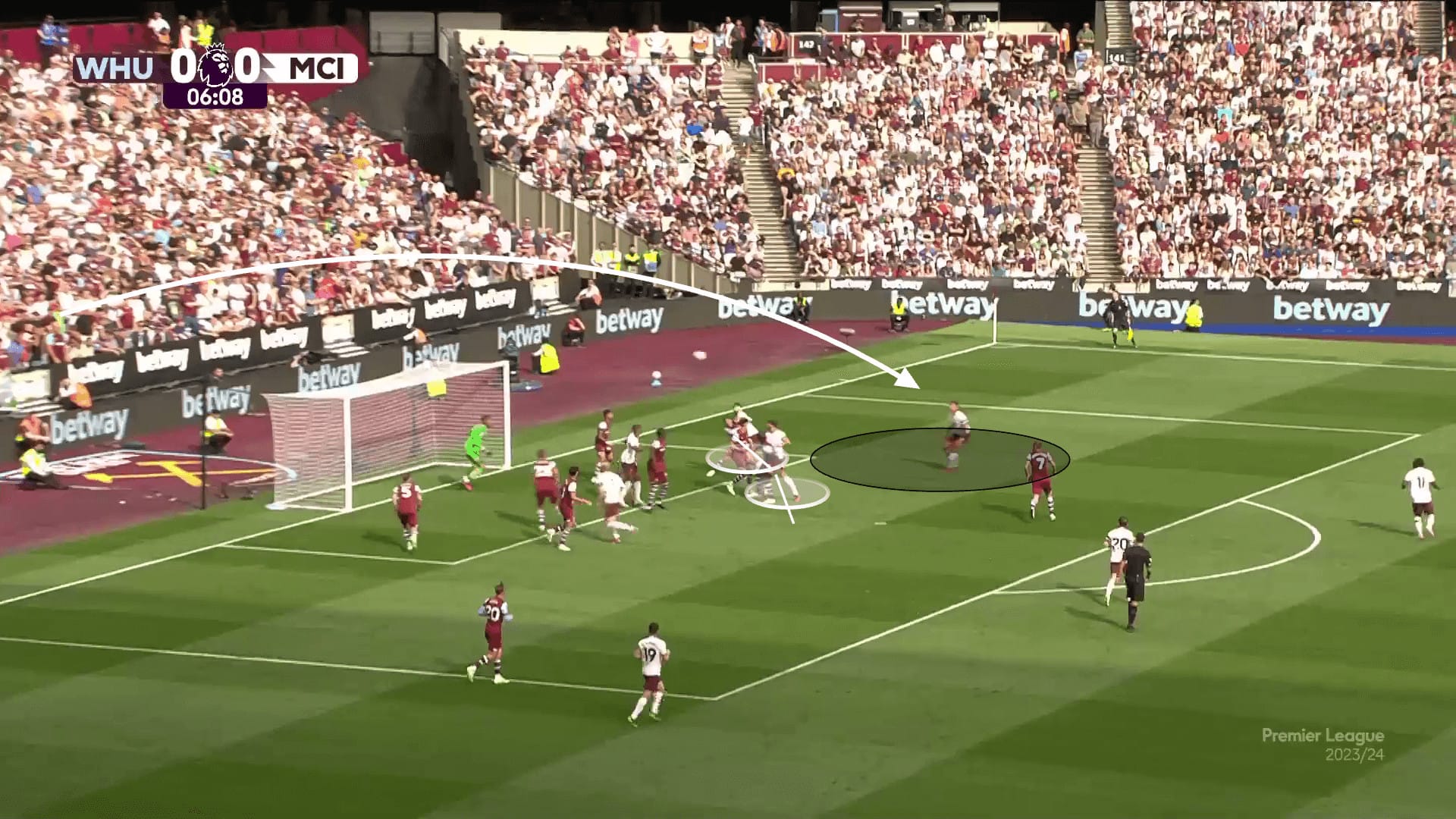

One way in which a deep attacker can be given more time and space is through the addition of screens, like Manchester City have been doing so well this season. The example below shows two attackers set up a screen on the nearest defenders to the target player.

This then gives Rodri all the time in the world to adjust his position to be able to attack the ball optimally. Man City successfully demonstrates how to use screens to make floated crosses still effective and also portrays that a corner doesn’t have to be aimed into the six-yard box to create a clear-cut chance.

Summary

This tactical analysis has demonstrated the different ways in which Lazio attempt to create chances from corners and the difficulties they face as a consequence of a lack of variety in their corners. We have offered potential variations for Lazio to use to remain unpredictable from corners, and the variety of corners will help make each routine more effective, as teams won’t be able to prepare for any routine confidently.

Comments