Lech Poznań are looking to bounce back to the top of the Ekstraklasa following a disappointing league campaign last season. Although the performances weren’t good enough, they still managed to make history by reaching the quarter-finals for the first time, where in the UEFA Europa Conference League, they were defeated by Fiorentina. The Polish giants have now sold key player Michał Skóraś to Club Brugge and have already crashed out of Europe during the qualification phase.

Just four weeks into the season, Lech Poznań have already caught the eye in a slightly negative manner. Just this season, they have so far faced 27 corners. Of the 20 corners directly crossed in, opposition teams managed an effort on goal from 8 of them. Disregarding the miskicked corners, which barely made it off the ground, Lech Poznań have allowed opponents to attack their goal with shots 47% of the time following direct balls being crossed in. This is not good enough for any side, let alone one aiming to challenge for a league title. Conceding, on average, a big chance from corners every game, or once every other game, is only a sign of worse things to come unless something changes sooner rather than later.

In this tactical analysis, we will look into the tactics behind Lech Poznań’s defensive corner setup, with an in-depth analysis of how their system has been exploited early on in the season. This set-piece analysis will examine why this method has been ineffective, how opposition teams can continue to attack them, and offer a solution to prevent so many chances from being created against them.

Current Structure

The current defensive setup for corner kicks by Lech Poznań has been consistent and identical for nearly every corner kick so far this season. The structure shown below uses five zonal defenders, three man-markers, and two players outside of that, whose role is to pick up second balls and to close down short corners.

Using a staggered line of zonal defenders helps Lech gain territory inside the box incrementally by forcing the attacking side to attempt to attack deeper areas of the box. With the outswinging corner, there is no threat for the ball to curl into the space behind the furthest zonal marker away from the goal.

The staggered setup is aligned with the natural curve of the ball, meaning that if the first zonal defender misses the ball or cannot reach it, the second defender has sight of the ball and is in a better position to clear the ball, as the ball is curving away from the goal. This is the case for each of the four defenders in a line, where, by the point where the ball may be too far from the fourth defender, it will be in a difficult position to score from. If the cross is aimed between the goal and the staggered line, there is a zonal defender by the front post to clear the ball away.

With the zonal defenders planted, three man-markers remain, whose role is to disrupt any attackers from being able to attack the ball unopposed. Then two players are left to react to second balls and begin potential counterattacks.

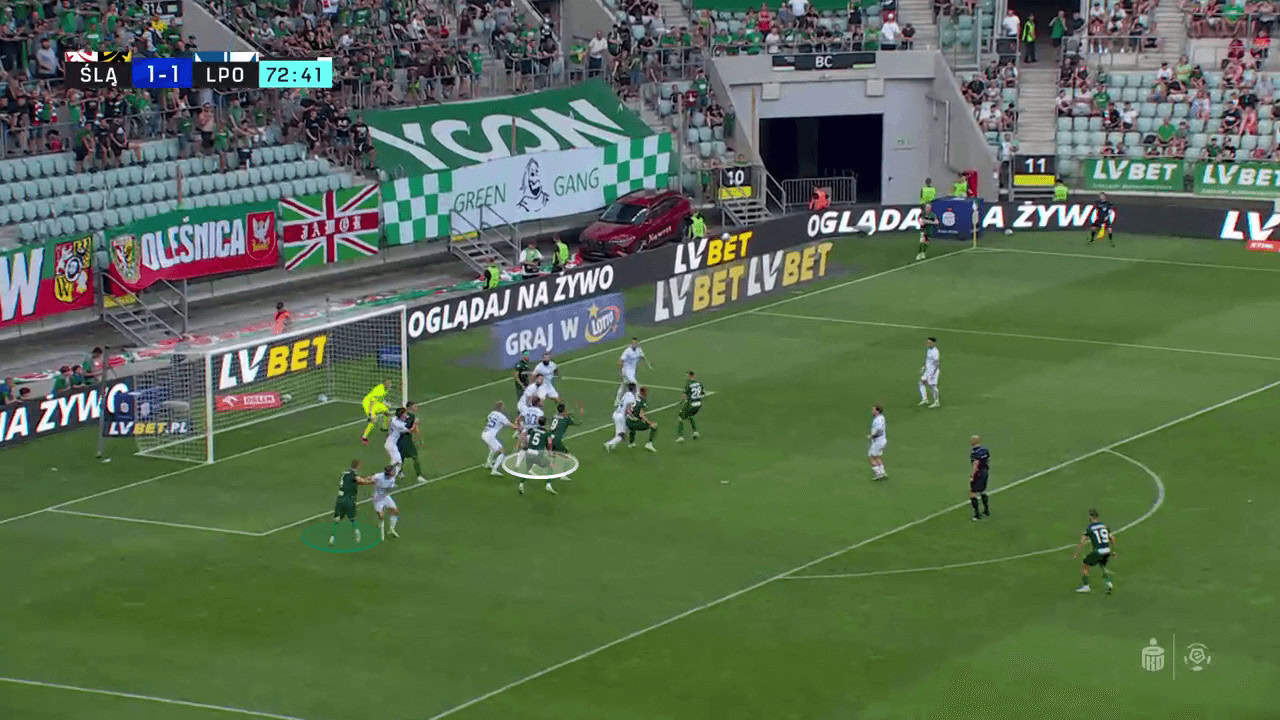

Lech Poznań’s setup has resulted in the individual man markers struggling with their jobs for several reasons. Firstly, as seen in the above example, the three players were often left outnumbered, and due to the free space some attackers had, it was difficult for the man marker to defend in such an open space.

Furthermore, in the example below, we can see multiple problems with the individual decisions of man markers. The defender highlighted in the white circle can be seen struggling with the basics of man-marking. Although the attacker hasn’t done anything to gain separation, the defender’s failure to stay tight to his assigned player means the attacker can attack the ball without resistance. The defender is too busy looking at the ball and forgets to keep close to the attacker, allowing him to run up to the ball without even attempting to put him off.

In addition, the attacker highlighted in the green circle can be seen with a clear path to attack the goal. The defender attempted to stay goalside, but when he glanced at the ball, the attacker can sprint past him and have a clear path to attack the goal with. Another issue stems from the defender’s inability to remain tight with the assigned attacker. Attackers can attack the ball unopposed due to the poor marking of individuals.

Potential Vulnerabilities

As defined above, the system comes with many potential flaws and opportunities to exploit by opposing teams. These vulnerabilities were nearly all exposed inside the first four weeks of the season after only 20 corners were crossed in. After such a limited number of games, having this many weaknesses from set plays is a cause for concern and should be changed before more teams start to take notice.

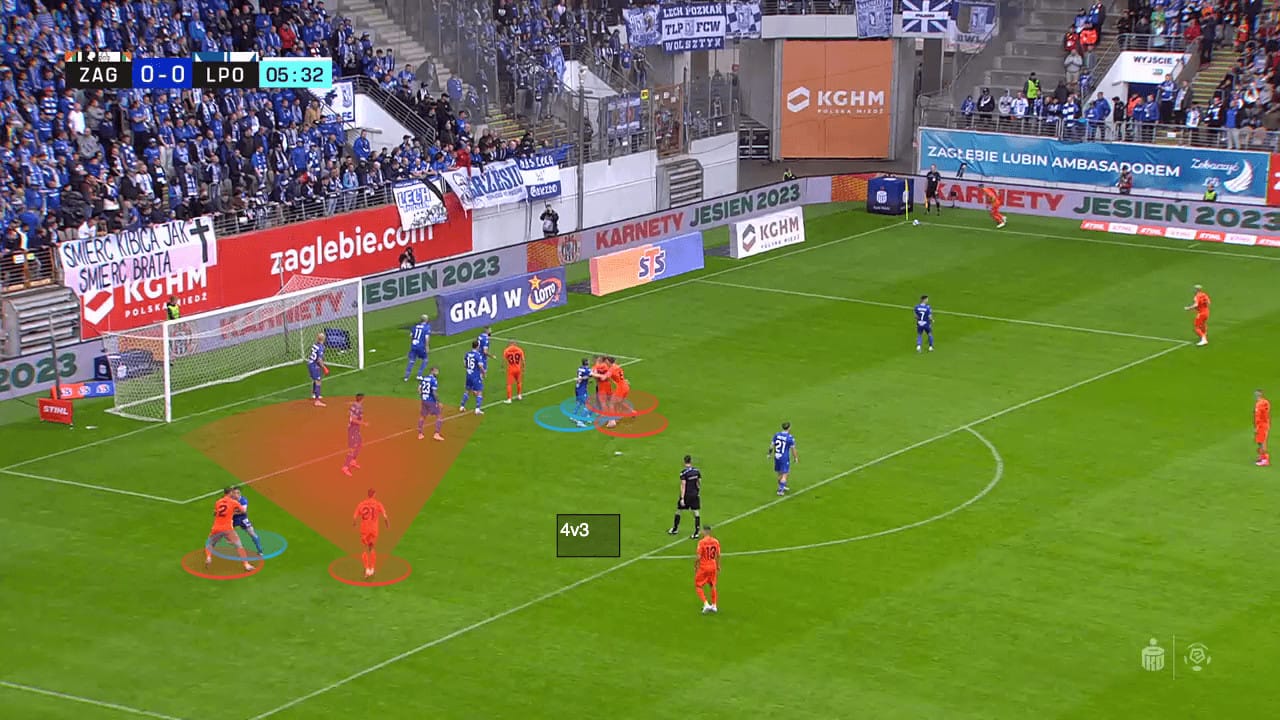

Firstly, the most common problem with zonal heavy defensive setups is the fact that many attackers can be left unmarked inside the box. Opposition teams have constantly been able to outnumber the man-marking group of defenders, which leaves some attackers unmarked and able to attack the ball unopposed. The attackers who aren’t marked gain the advantage by possibly attacking the ball without any disruption. Attackers can time the run-up to the ball so they can attack it with speed and judge its flight to attack it at its highest point. Being able to have a sprinting run up to the jump helps to increase the chance of winning the aerial duel over a defender who jumps from a static moment and then increases the likelihood of scoring the header as they can head the ball more powerfully than if a defender was trying to stop them.

Furthermore, with the small number of defenders man-marking players, it is easy to isolate defenders to make them defend over larger spaces inside the box. In the image below, the attacking unit of four is split into two groups of two. In doing so, we can see a 2v1 at the back half of the box, where one defender has a massive amount of space to defend while another attacker is entirely free to attack the six-yard box.

Another significant issue that comes up with an underloaded group of man markers is that attackers can gang up on individual defenders. 2v1‘s situations can be commonly created, which allows attacking teams to have complete freedom in deciding what space to attack and who should attack it. Lech Poznań may think that marking the most threatening players out of the game and leaving the least threatening players free will suffice; however, that is not always the case.

With these overloads, opposition teams can create these 2v1 scenarios and use weaker aerial players to distract or block defenders in order to create space for the strongest aerial players. Without sufficient man-marking numbers, Lech Poznań are highly vulnerable during corners, mainly because of the ability to oppose teams to deliver the ball to the strongest headerers regularly.

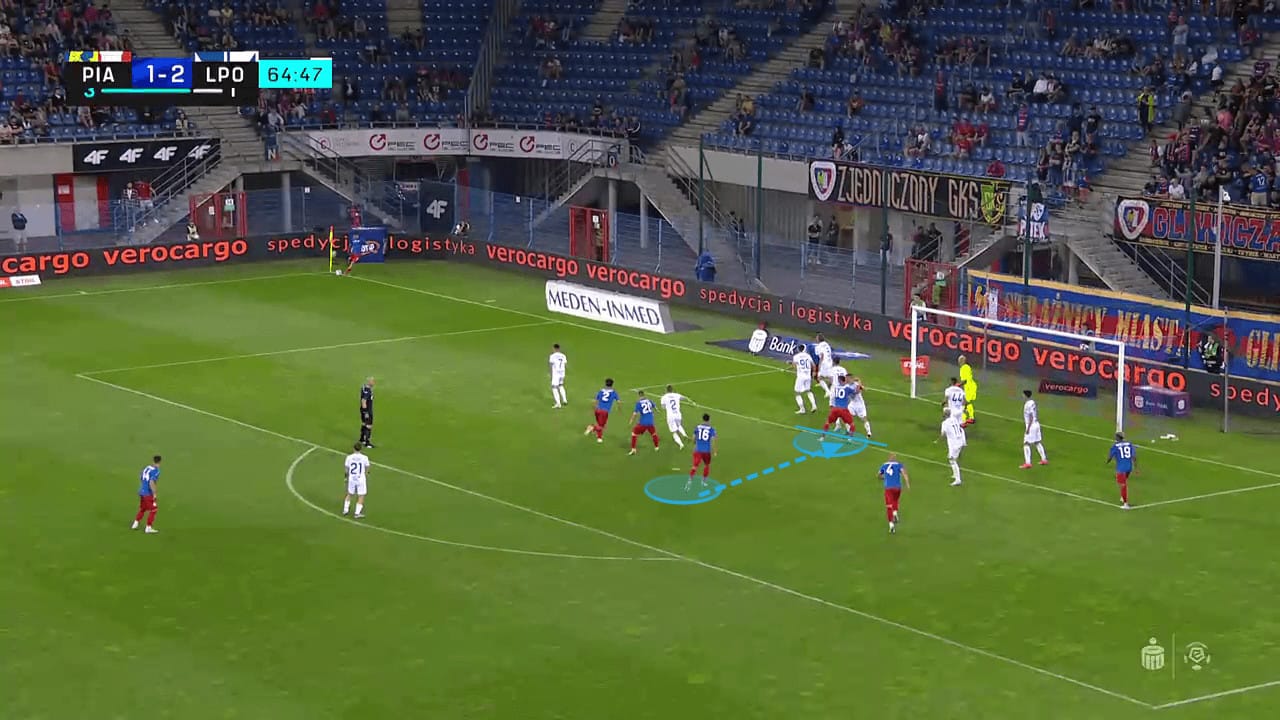

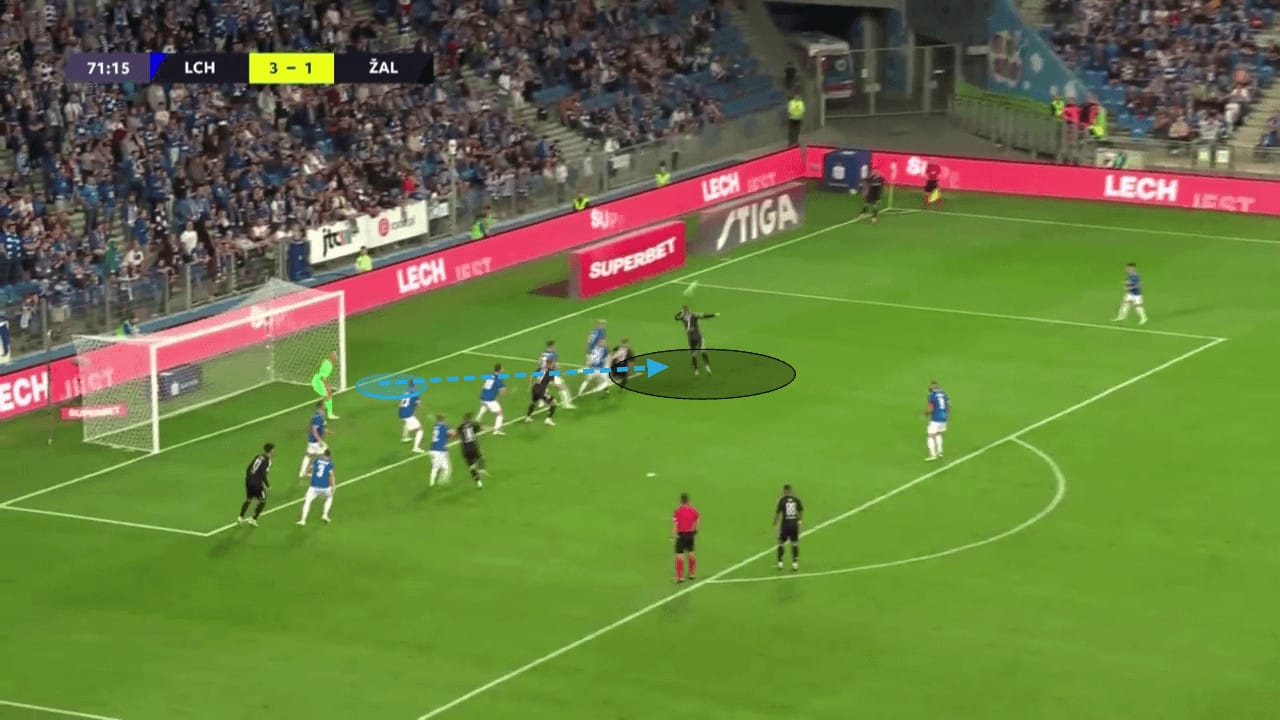

As seen in the image below, a free attacker can perform a screen from the defender’s blindside, allowing the marked attacker to attack the unmarked six-yard box.

As mentioned above, a problem that arises with a large number of attackers being unmarked is that they are able to perform screens freely. With Lech Poznań’s predictable and ineffective setup, it is even easier to set up these screens with so many static targets (zonal markers).

Opposition teams know each week where five players will be every time, and with their static positioning, performing these screens is simpler as defenders have more difficulty evading the screen when they aren’t on the move. This also allows opposition teams to plan the points at which they would attempt to penetrate the six-yard box and prepare the runs of the free players positioned deeper.

The image below shows the screen being performed on the six-yard line, which creates plenty of space for an attacker from deep to attack the open space. There is also a screen on the front post zonal marker in order to provide another option for the corner taken.

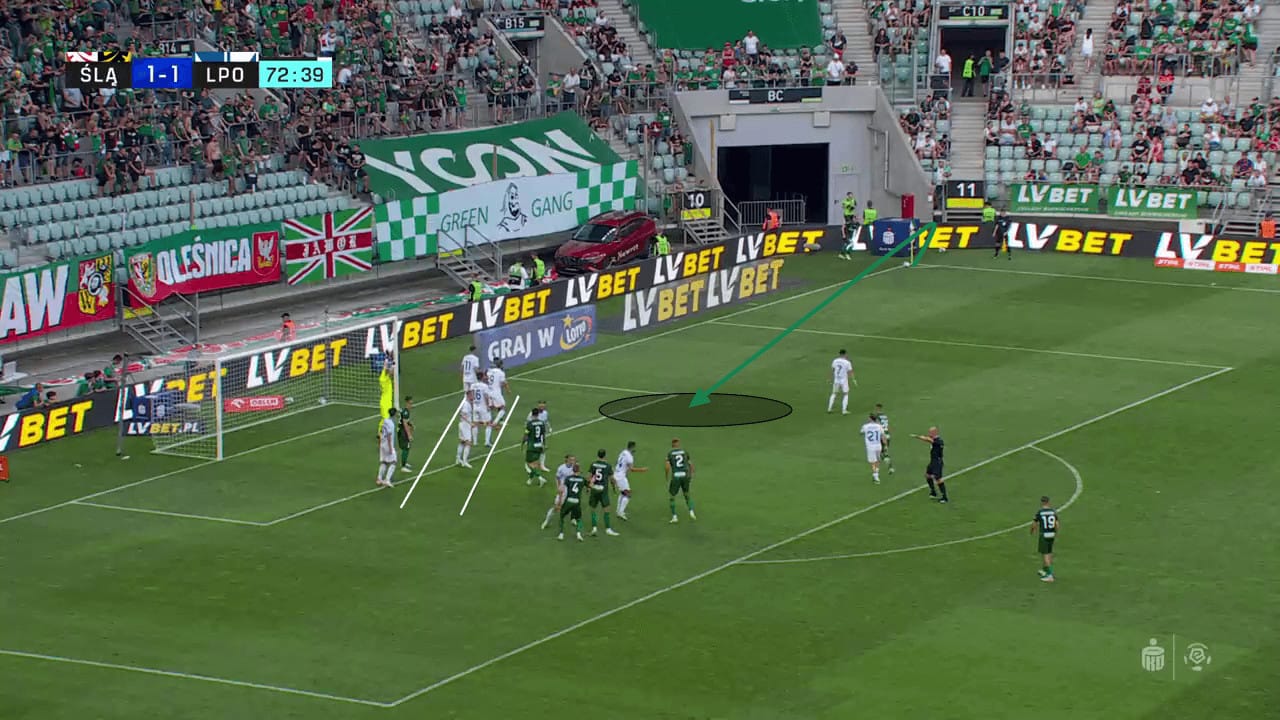

One slight issue that Lech Poznań have also come up against is their inability to adjust depending on the corner taker’s preferred foot. Against outswinging corners, a staggered defensive line can be effective as the zonal defender’s action, whether successful or not, is irrelevant.

If they miss the ball, the defender behind them will be there to get rid of it. However, with an inswinging corner, it becomes harder for defenders to judge whose job it is to step out to the cross. This can leave space, as shown in the image below.

If the cross is aimed inside the six-yard box, there is a possibility one of the nearer zonal defenders misses the ball, and it may go through the gap between them and into the space at the back post.

This open area by the near edge of the six-yard box leaves Lech Poznań vulnerable to this type of cross. Even though this area may not be highly valued, Lech is exposed to a different kind of cross. From this point, Lech are vulnerable to being exposed to near-side flick-ons, where the ball can be flicked on into the six-yard.

Flicking the ball into the six-yard box from a corner can completely unsettle and disorganize zonal defences, no matter how much of a defensive presence there is. Teams have easy access to the near side of the six-yard box, meaning they can make the first contact with a smaller amount of attackers in that area, making it possible to overload the back side of the six-yard box to increase the likelihood of winning the second ball.

Summary

The tactical analysis has detailed why Lech Poznań’s defensive set play setup has been ineffective. The lack of man-marking has left Lech vulnerable to various ways they could be exposed, and they have already been exposed on numerous occasions in their opening four weeks.

Lech Poznań are a reasonably dominant team in the league, but points could slip away if they continue to give away clear chances from set plays. Increasing the number of man-markers and higher concentration levels from those individuals could improve their defensive record. However, it would have to come at the cost of reducing their counterattacking threat.

This is a risk that Lech Poznań have to assess, but considering their strong attacking options, there is no point in giving away free goals at the prospect of a chance to counterattack a side where they still have 90 yards to travel before scoring.

Comments