Under Brendan Rodgers, Leicester City had two great seasons as top-four challengers and consecutive appearances in the UEFA Europa League. While they reinforced with the likes of Patson Daka, Ryan Bertrand, Jannik Vestergaard, and Boubakary Soumaré, they have failed to reach the same standard as they did before. After 23 Premier League games, they were the 11th of the league with two games in hands to play than most of the teams, but they are not near to the European competition seat.

Leicester conceded 50 goals in 2020/21, but the number of goals against is already 43 at this stage of the season – their defence is clearly not as solid as they were. If we delve into the distribution of their conceded goals, their corner defending is a very big problem. Last season, the Foxes only conceded nine corner goals in 53 games in all competitions; while they played 37 games in 2021/22 so far, they have 12 conceded corner goals. Their vulnerability of corner defending was obvious, and Rodgers also knew this through his analysis of the game.

However, even with the Foxes trying different tactics to defend dead balls, not much has changed. This set-piece analysis is a scout report that explains how Leicester struggled in their corner defending this season.

Mixed system

At the beginning of the season, Leicester just set up the defensive corners with a mixed approach very similar to other good teams in the league. They would have four to five zonal defenders to guard the six-yard box, and some man-markers to mark the identified threat of the opponents. This approach was not successful because they have been conceding corners, we are providing some examples below to illustrate.

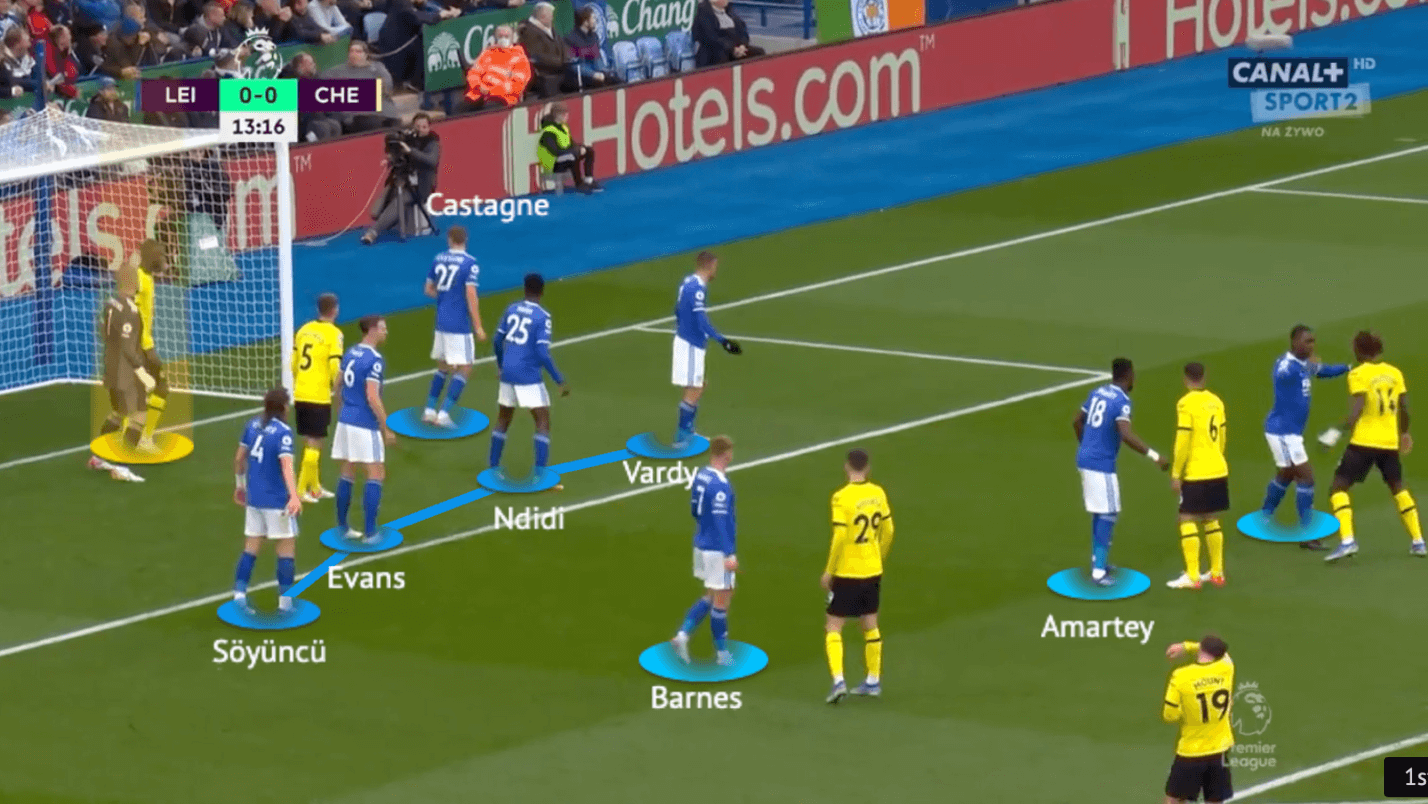

Firstly, we showed Antonio Rüdiger’s goal at the King Power Stadium. Leicester had five zonal defenders three to four man-markers, and a goalkeeper closer to the goal line. The four-man zonal chain included their best players in the air, such as Jonny Evans and Çağlar Söyüncü in the centre of the six-yard line. They also had Timothy Castagne and Wilfred Ndidi as a part of the zonal system.

Soumaré and Daniel Amartey are players possessing some physical qualities, they were assigned as the man-markers alongside with Harvey Barnes. However, Chelsea used a good strategy to create the goal, Rüdiger’s beginning position is close to Kasper Schmeichel.

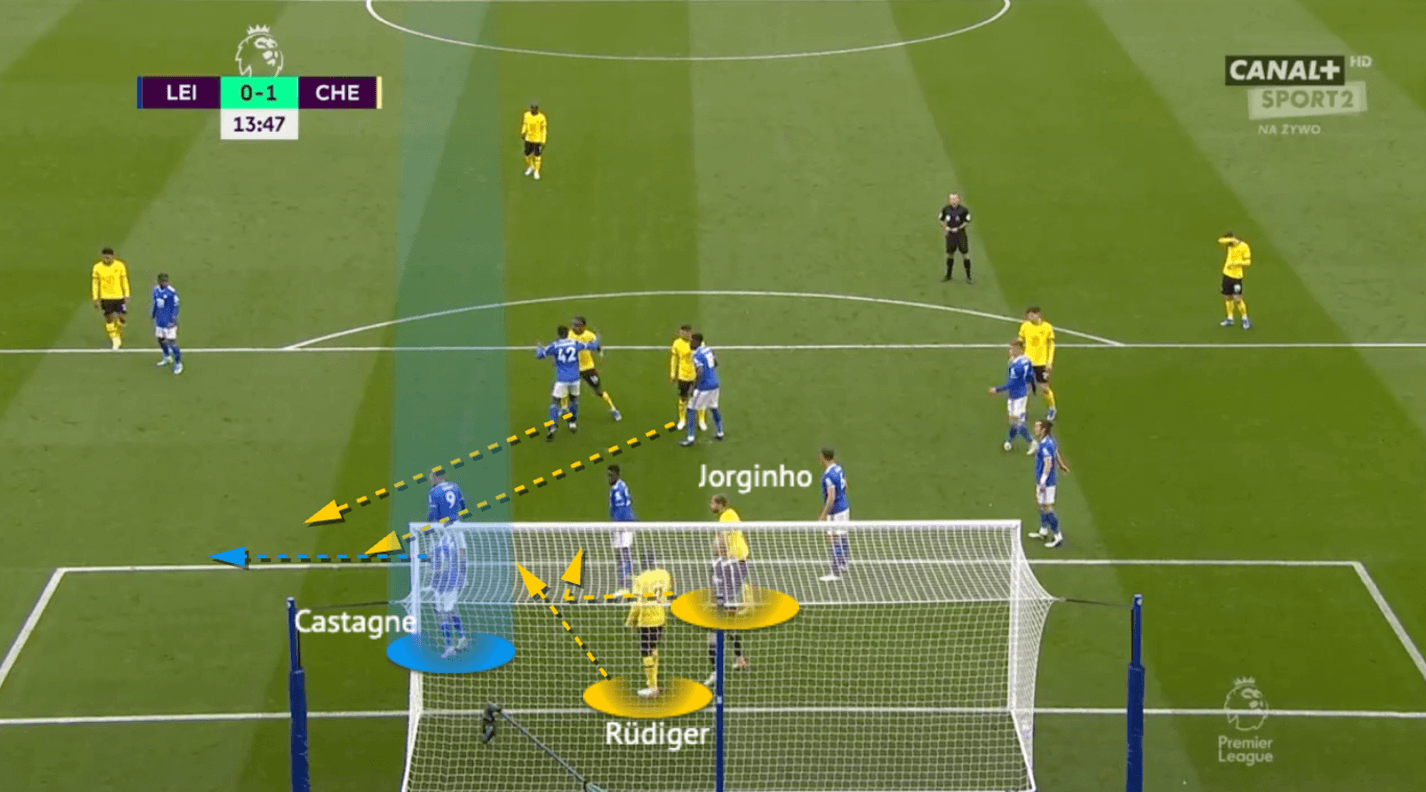

When the move began, the two deep players of Chelsea attacked the front side, Leicester defended that by using both man-markers plus two zonal defenders. As we see in the image, Jamie Vardy reacted to the movement and stepped up to the endpoint of Thiago Silva’s deep run. That means his distance with Ndidi increased, the gap in the zonal chain was bigger.

Meanwhile, Jorginho, who initially positioned himself between the zonal chain and Castagne, very cleverly sneaked in front of Ndidi as a screener, separating the Nigerian defender and Rüdiger.

As a result of Vardy’s impatience to move early, the screener to prevent Ndidi from closing the gap, Rüdiger scored a great free header in that position. Who is responsible for that space? Leicester had three players around but none of them could compete, not even jumping together with the German defender.

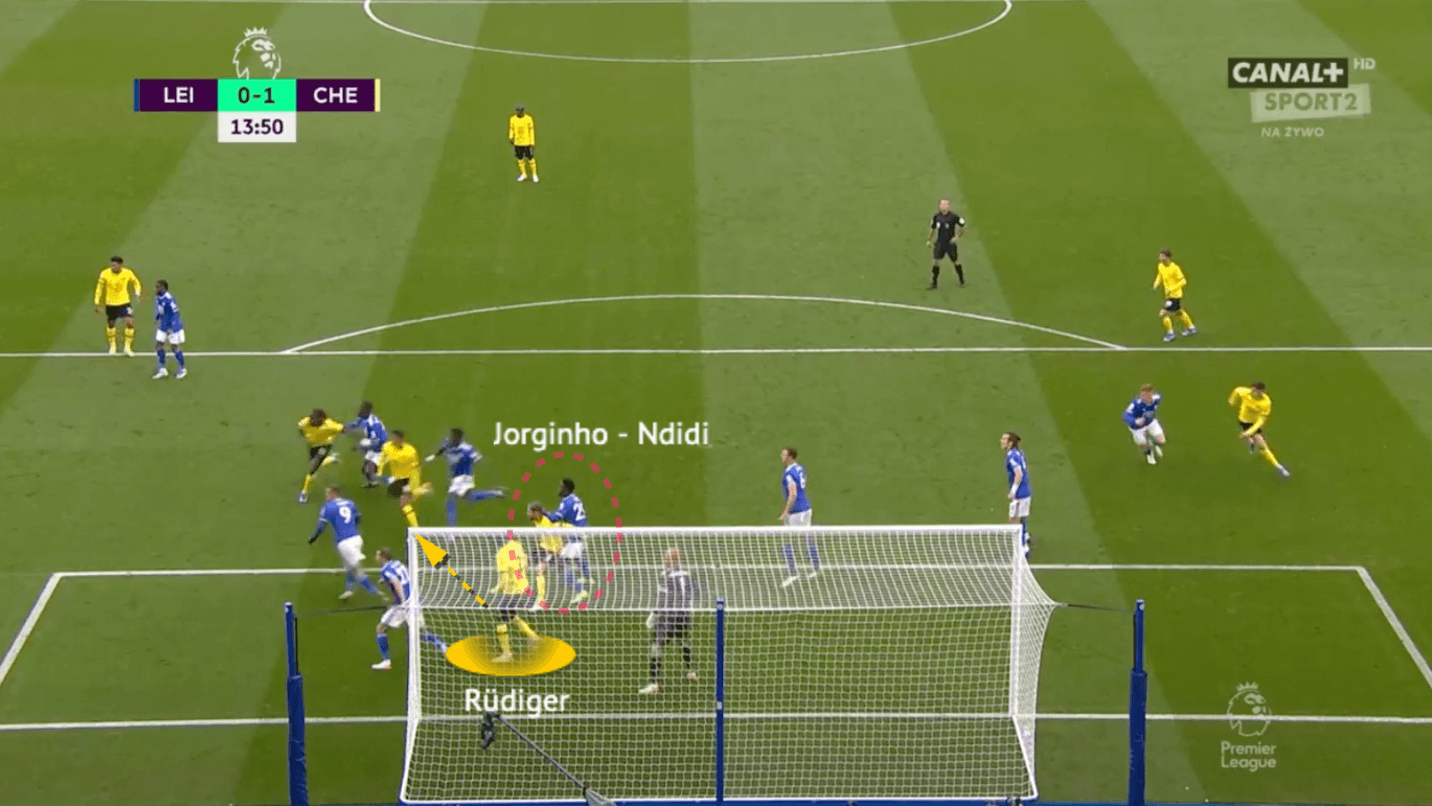

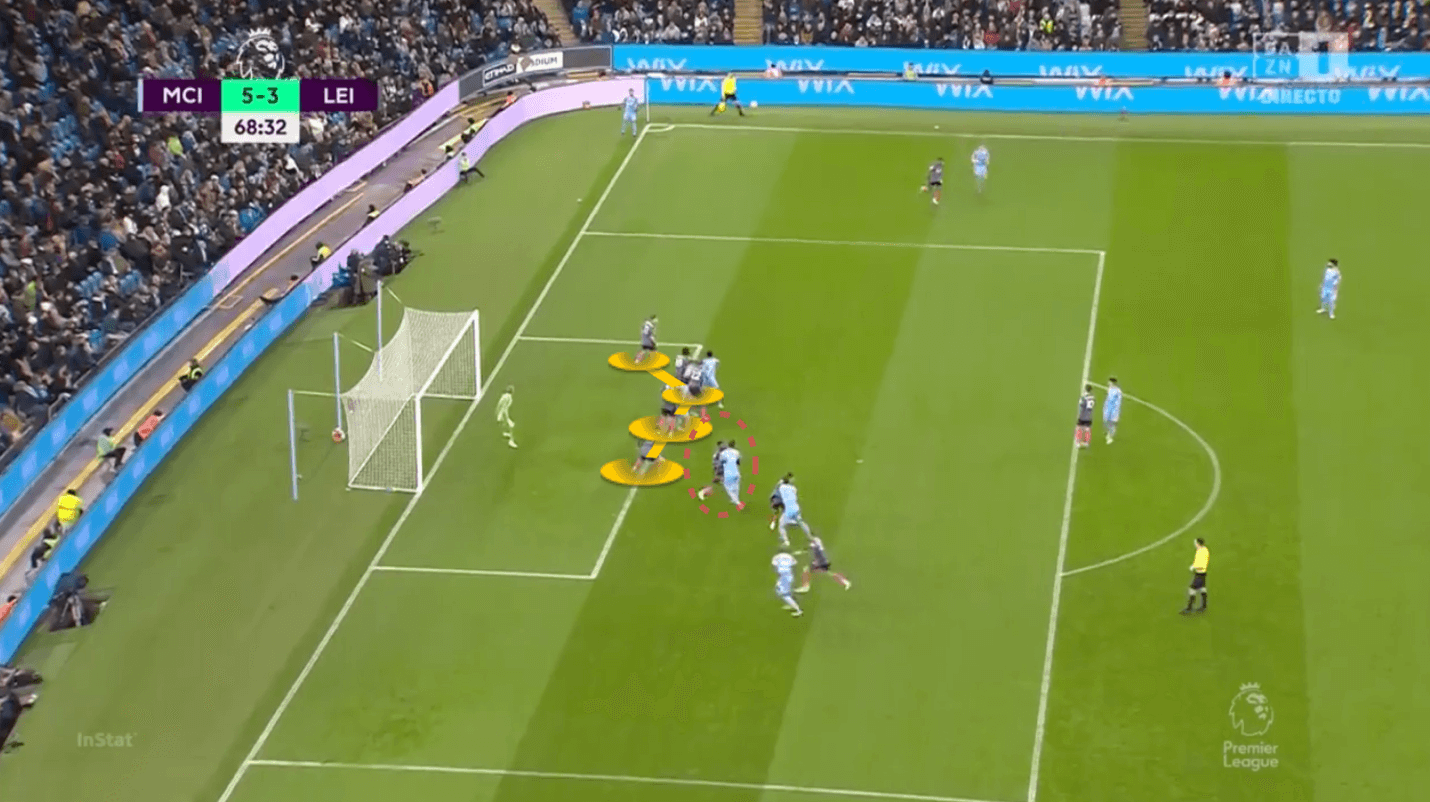

In the away game which they lost 3-6 to at the Etihad Stadium, they conceded some corner opportunities again and that triggered Rodgers to make big changes in the system. Let’s see what happened in Aymeric Laporte’s goal.

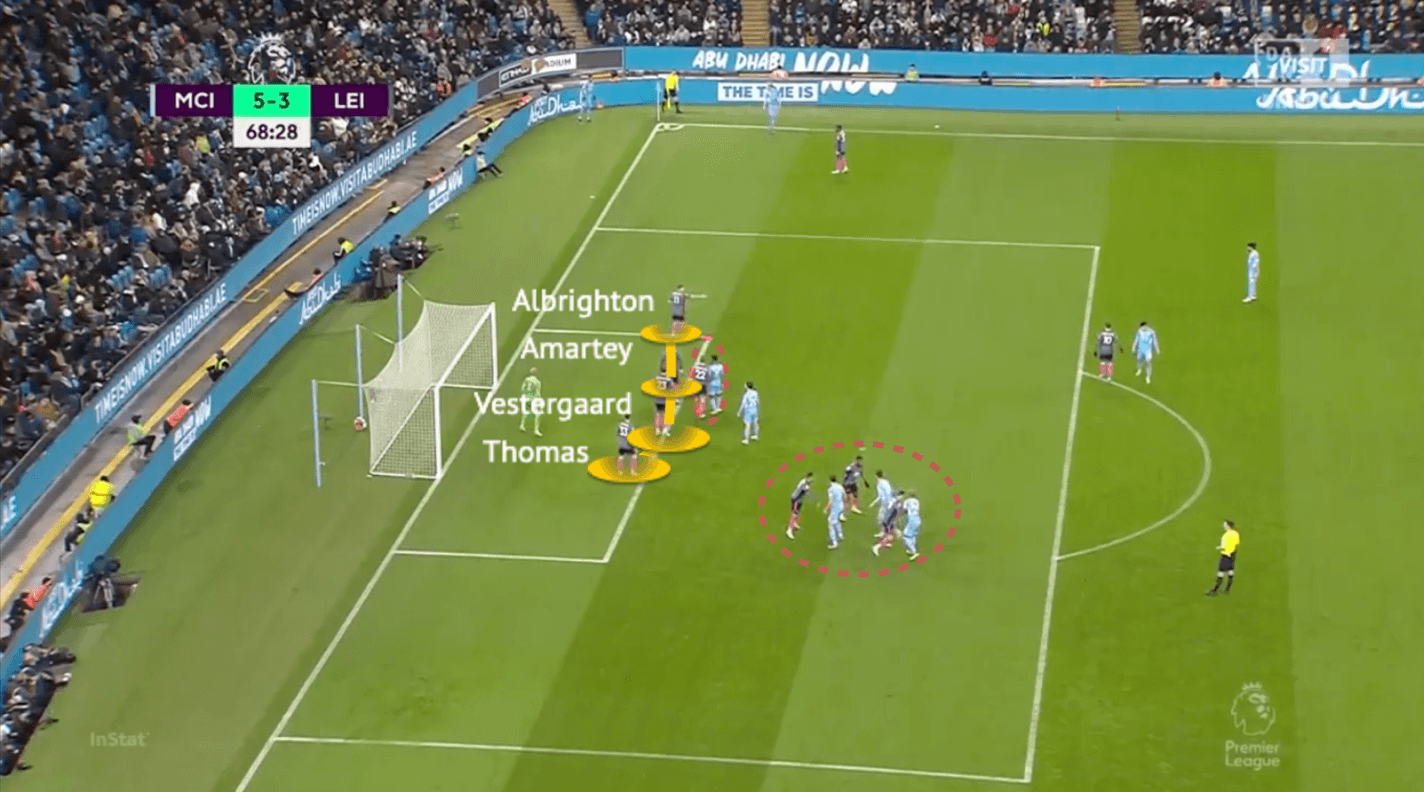

This time, the four-man zonal chain was formed by Marc Albrighton, Amartey, Vestergaard, and Luke Thomas because the other centre-backs are all injured. City had two players two disrupt the zonal chain and the other three players attacking from deep, matched by three Leicester man-markers.

Let’s focus on Laporte, his marker was Kelechi Iheanacho, who was also tall but possessed less upper body strength. The City defender was going to attack the last defender of the zonal chain. Iheanacho was still with him in the above image.

But then, when Laporte attacked the ball, Iheanacho was not even jumping together, he was still on the ground. And the zonal defender was not defending that space either, because he was in a relatively static posture before the ball arrived. Unlike Laporte, who came with speed after a short-distance sprint, it was difficult for the zonal defenders to compete.

Adding post player(s)

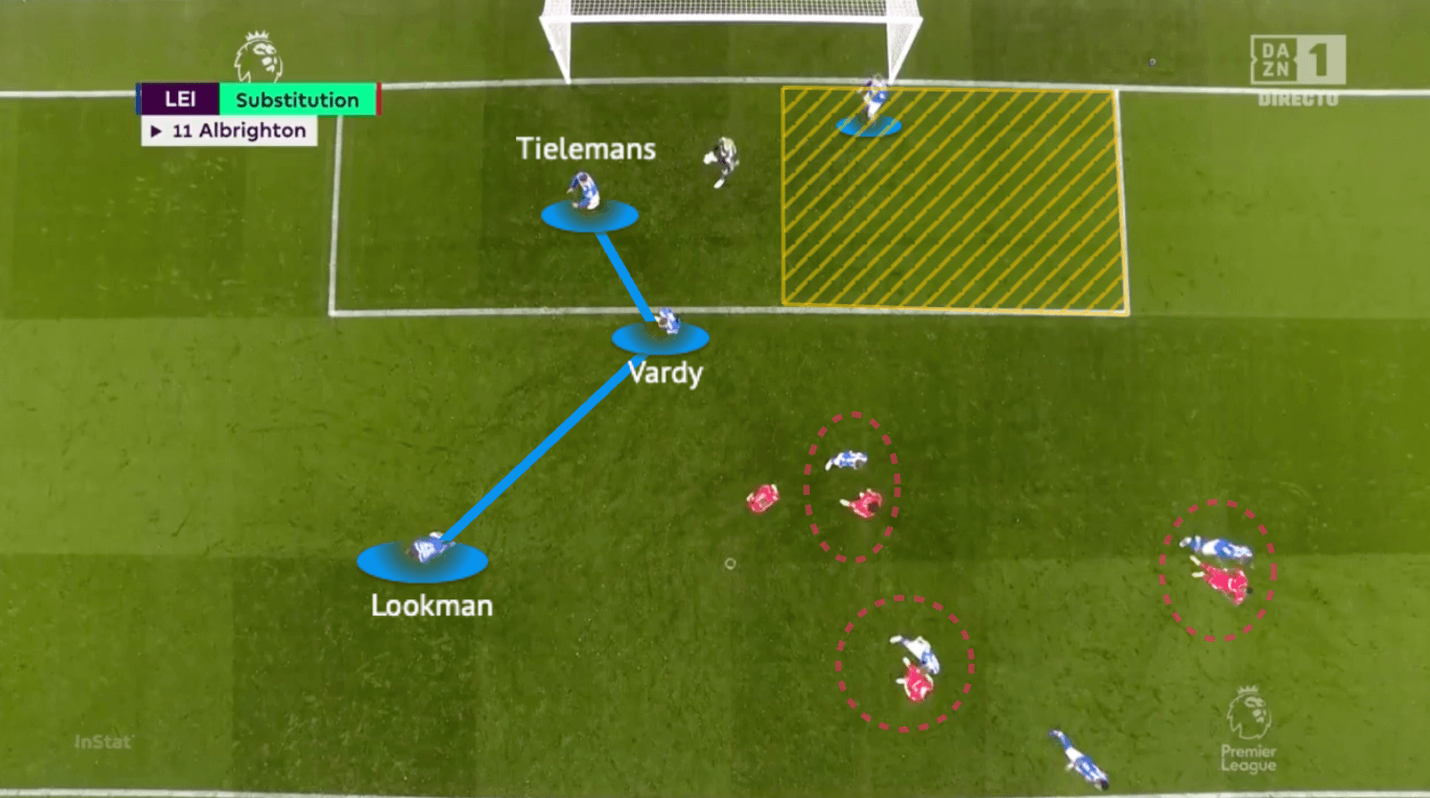

Rodgers tried to change the personnel in the mixed approach. Since the zonal chain could not defend the space, he even remove the centre-backs from it and use Söyüncü as a man-marker. But these changes did not help either, so Rodgers had a big change in the defensive corner system. No more zonal chain, as post-players were added.

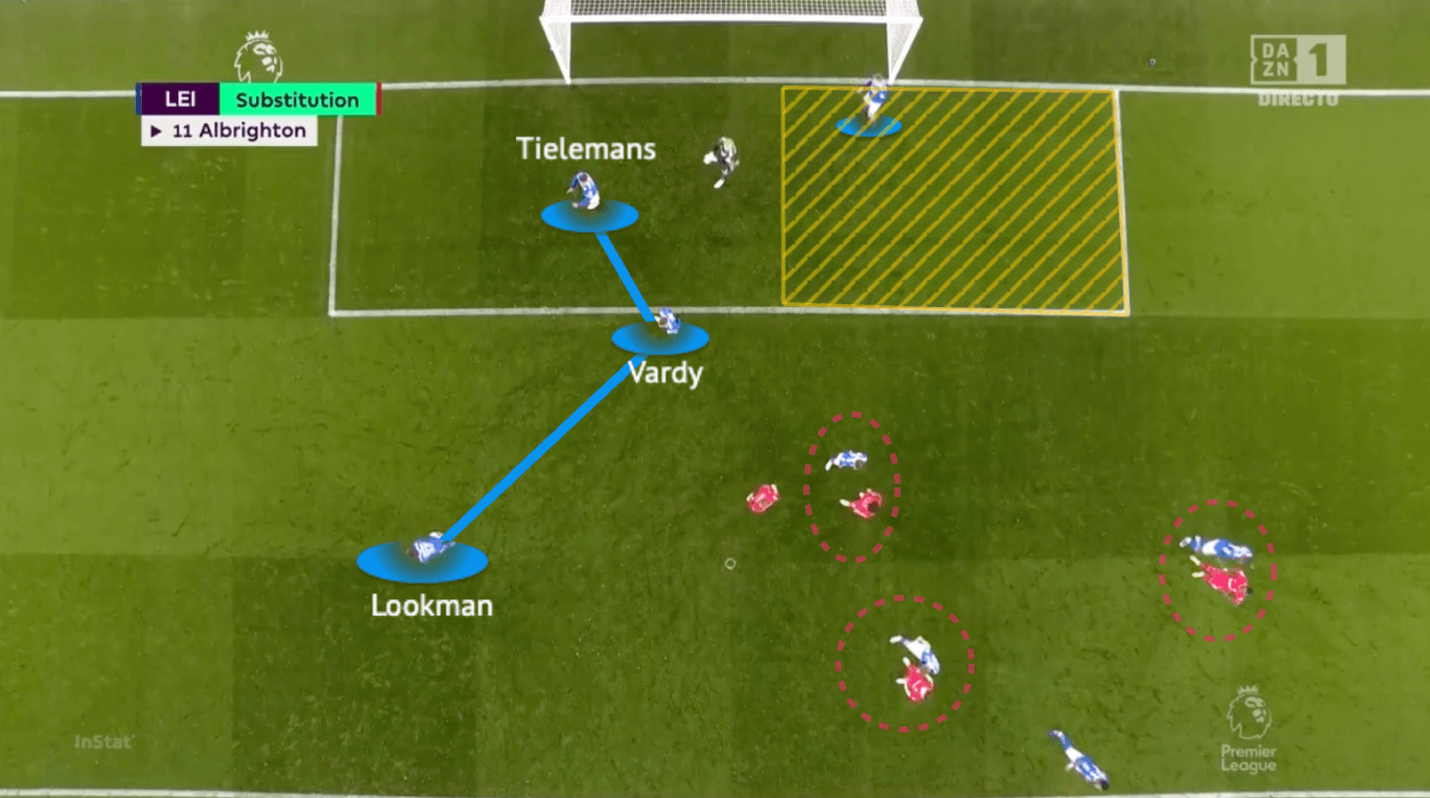

Since the zonal chain was ineffective, this was removed and now the zonal defenders were more like a vertical chain. They spread in three vertical zones to defend the ball near side, but none of them are good in the air (Ademola Lookman, Vardy, and Youri Tielemans above). The best aerial defenders were sent to man-mark the opponents.

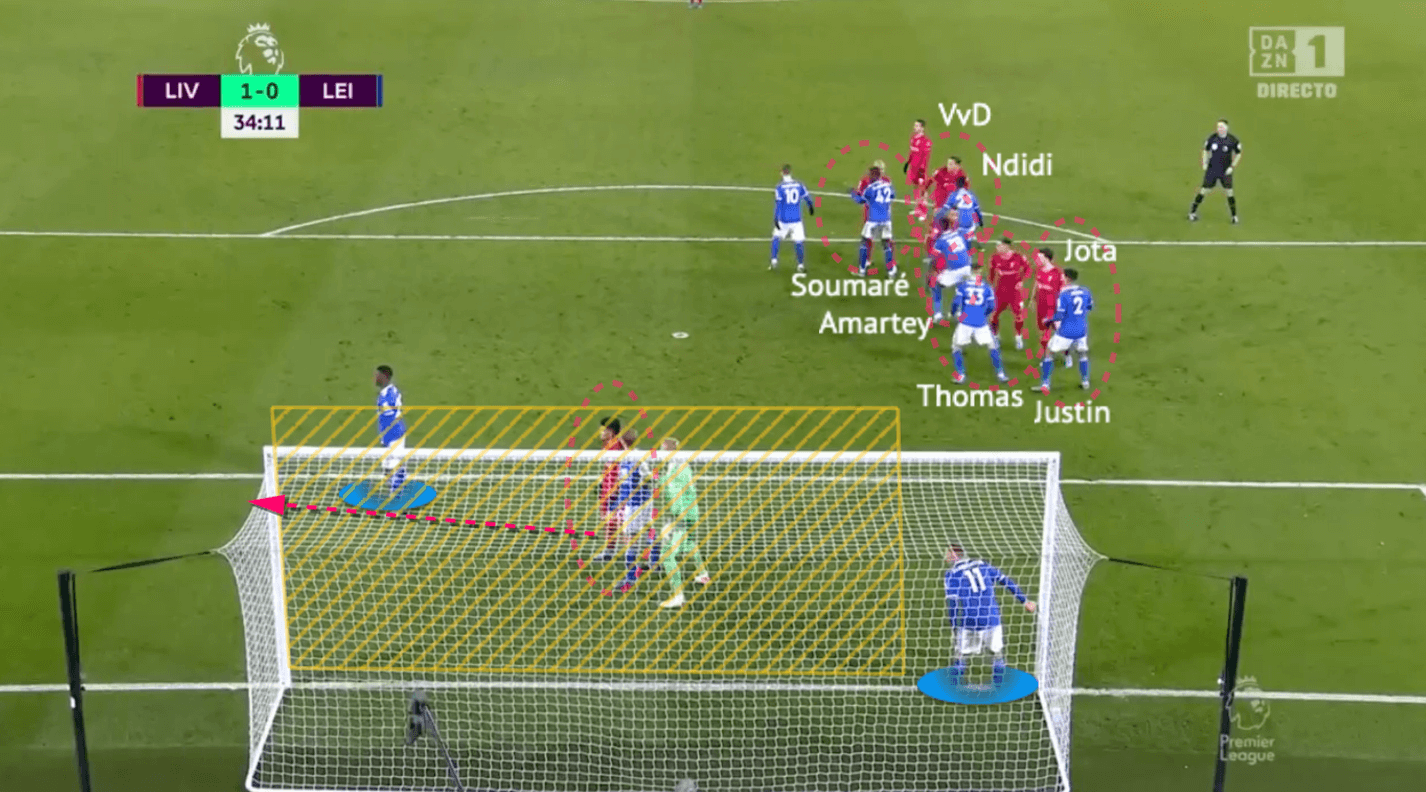

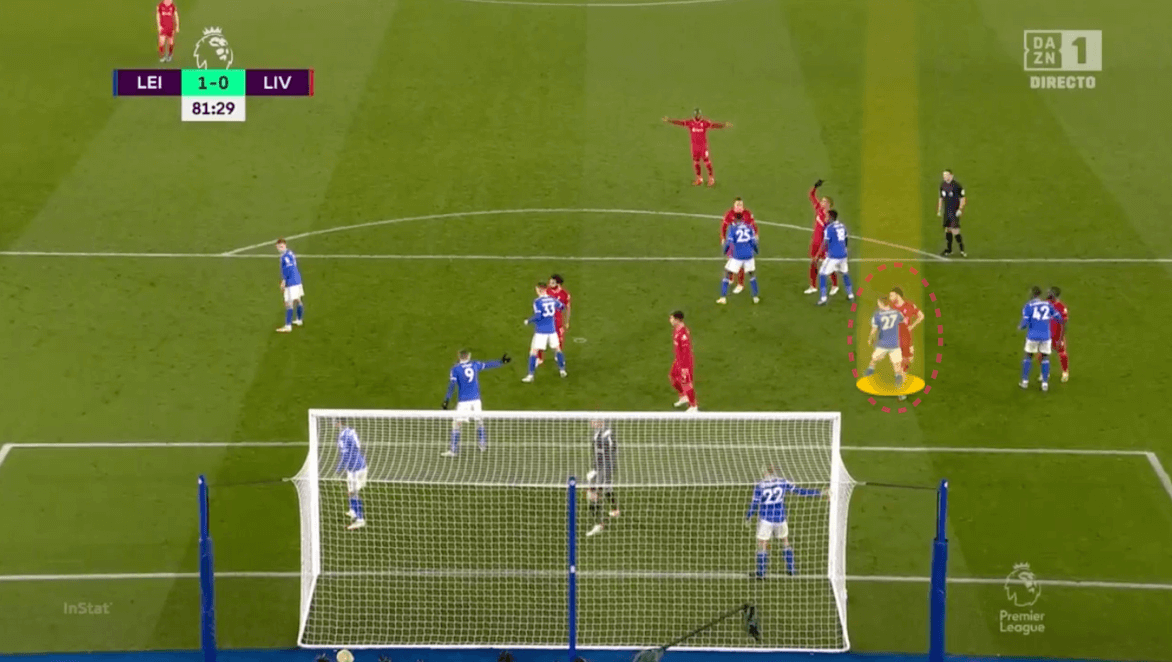

The above image from a higher angle shows a good picture of how Leicester’s new structure looks like. Apart from the zonal defenders, there was one player guarding the far post, without anyone in the near post. This is because Liverpool mostly delivered outswingers in the corners, with Andrew Robertson on the left and Trent-Alexander Arnold on the right side. If the opponents used inswingers, there would be two post-defenders.

However, the keeper is farther away from the goal line now because they also expected the post player to only stay under the frame, instead of defending spaces as a zonal defender. The yellow zone is the goalkeeper’s punching area and now Schmeichel is tasked to cover larger spaces in the defensive corners.

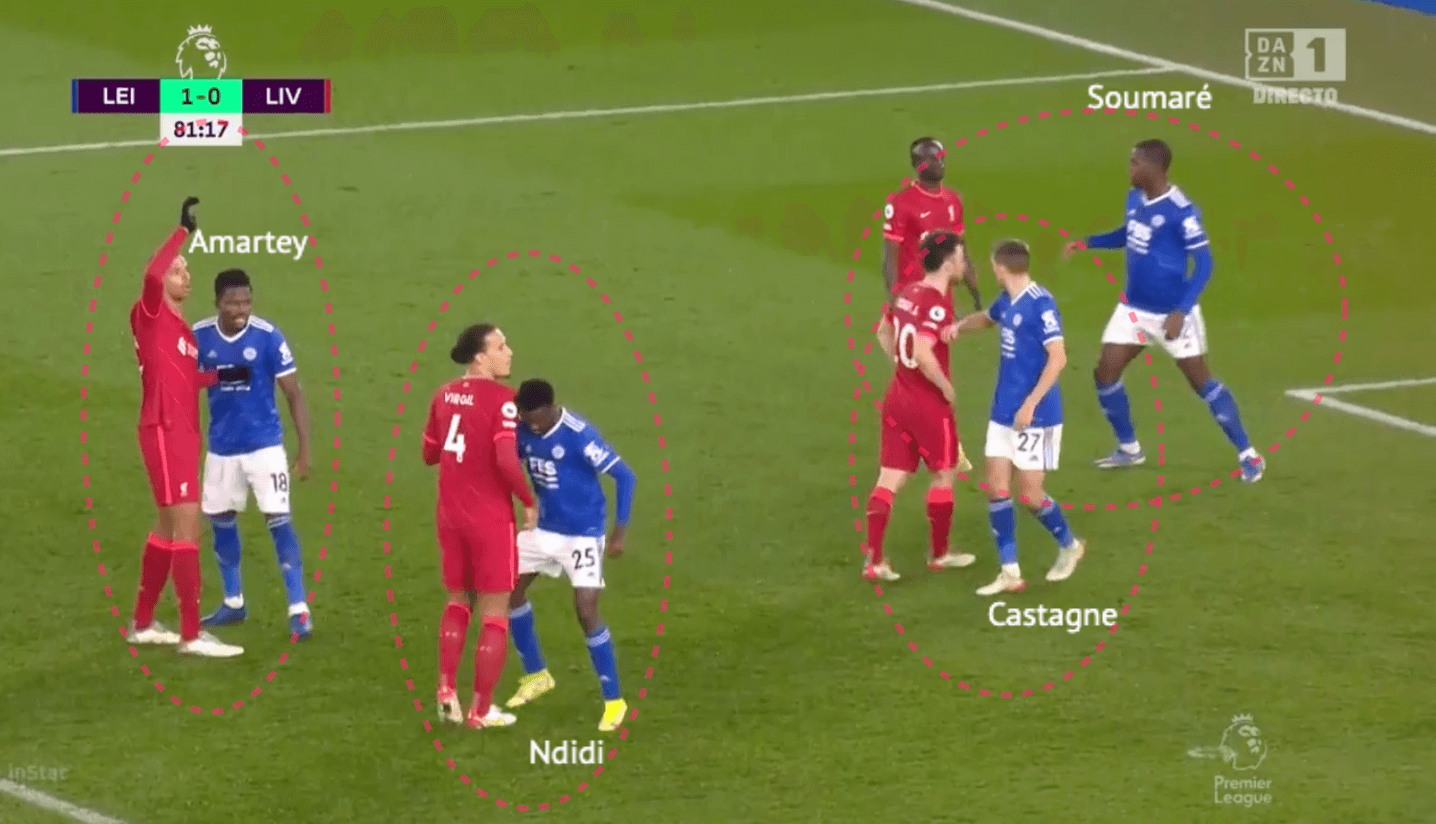

The strongest defenders, including the centre-backs, are no longer part of the zonal system. They all went out to man-mark an opposition. As we have shown in this image, Ndidi and Castagne became the man-markers to mark the physical and mobile targets of Liverpool: Virgil van Djik, and Diogo Jota.

The intention of deploying post players, are usually because you do not believe the ball can be won in the first aerial duel. Therefore, there was a player guarding the post to clear attempts on the goal line. On some occasions, Leicester did have a defender protecting the goal and helping them to prevent the ball from going in.

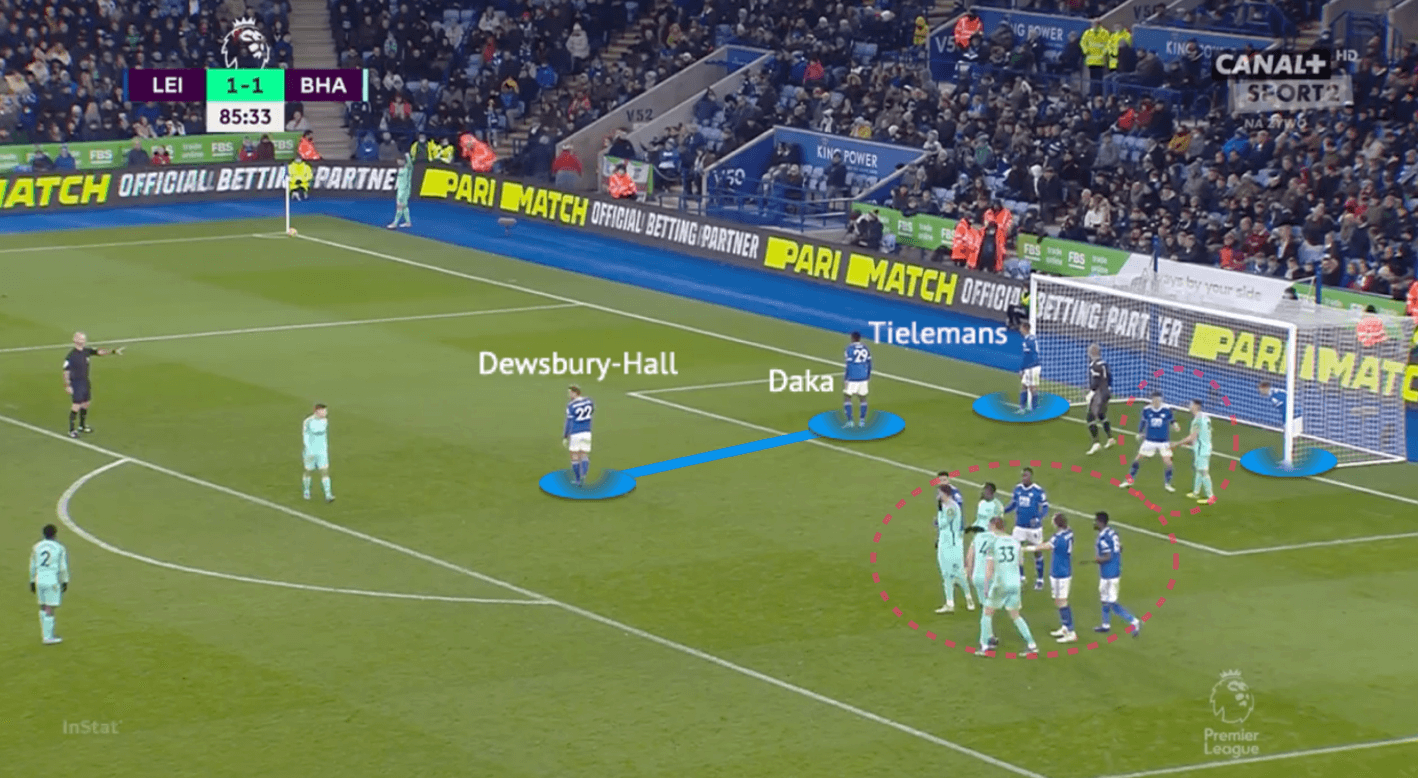

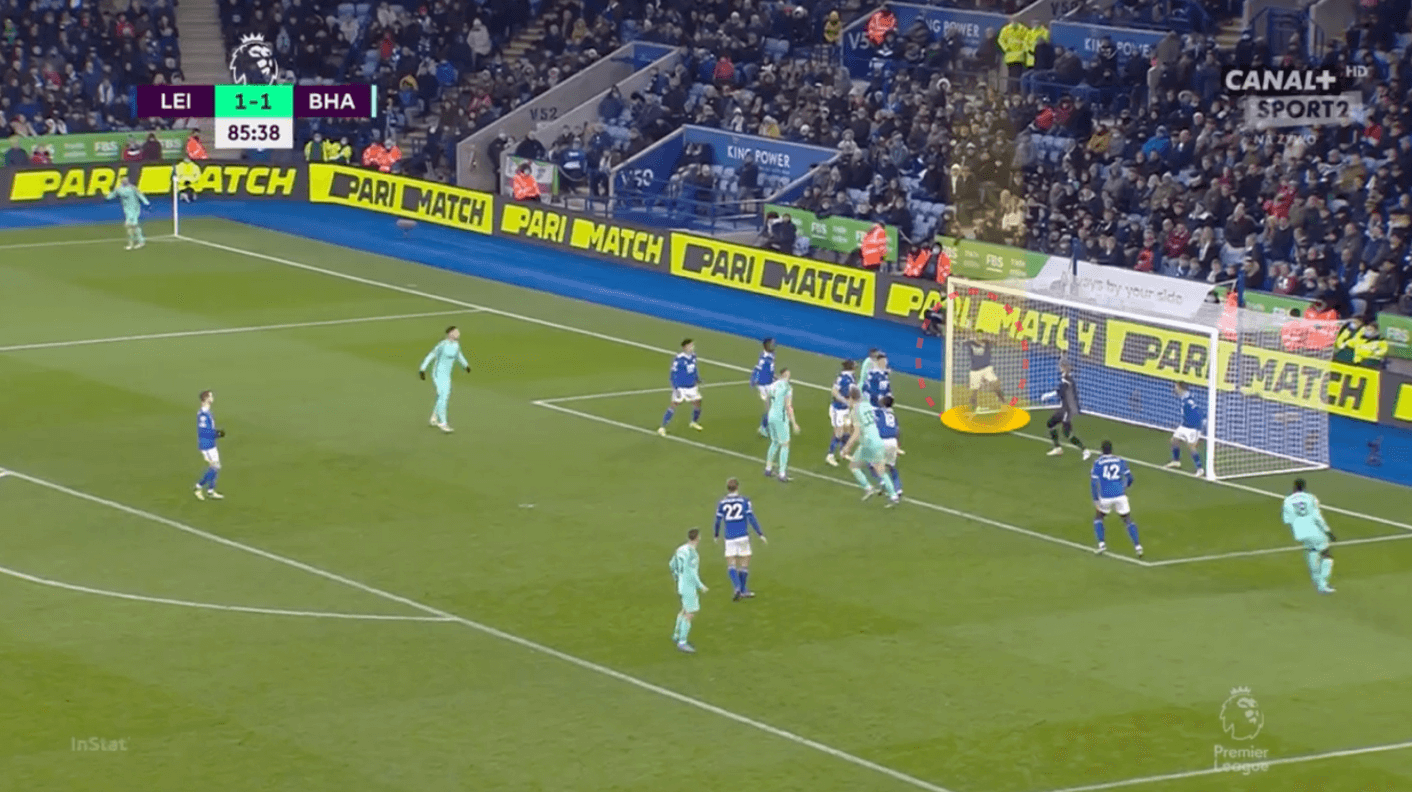

For example, Brighton took the corner with an inswing delivery, so there were two players guarding each post. The zonal vertical chain was formed by two players only, Daka, and Kiernan Dewsbury-Hall. Neither of these two players were strong defenders in the air, as Leicester deployed their strongest players as man-marker to cover the Brighton group on the far side. Tielemans was the post-player who stayed at the near post.

But they eventually lost the first duel, here was a situation which the post-defender came to rescue. The ball was headed towards the goal and left Schmeichel without any reflection, but Tielemans’ defensive positioning helped him to clear the danger off the line, which is an expected outcome of the shift of approach.

The logic of this change was Leicester was they assumed the zonal defenders and man-markers were less capable of winning the first aerial duel, so they rather took another preventive measure by putting more players under the goal frame. However, this was not the antidote because teams also came up with strong measures to counter, which we are going to explain below.

Exposing the six-yard line

Recently, in the successive games against Nottingham Forest, Liverpool, and West Ham United, the defensive woes of Leicester was back again they conceded one corner in each game. Although the system was new, the opponents also came up with other plans to exploit. Because now there was no more zonal chain in the system, the six-yard line became very exposed and the opponents often targeted that area to attack.

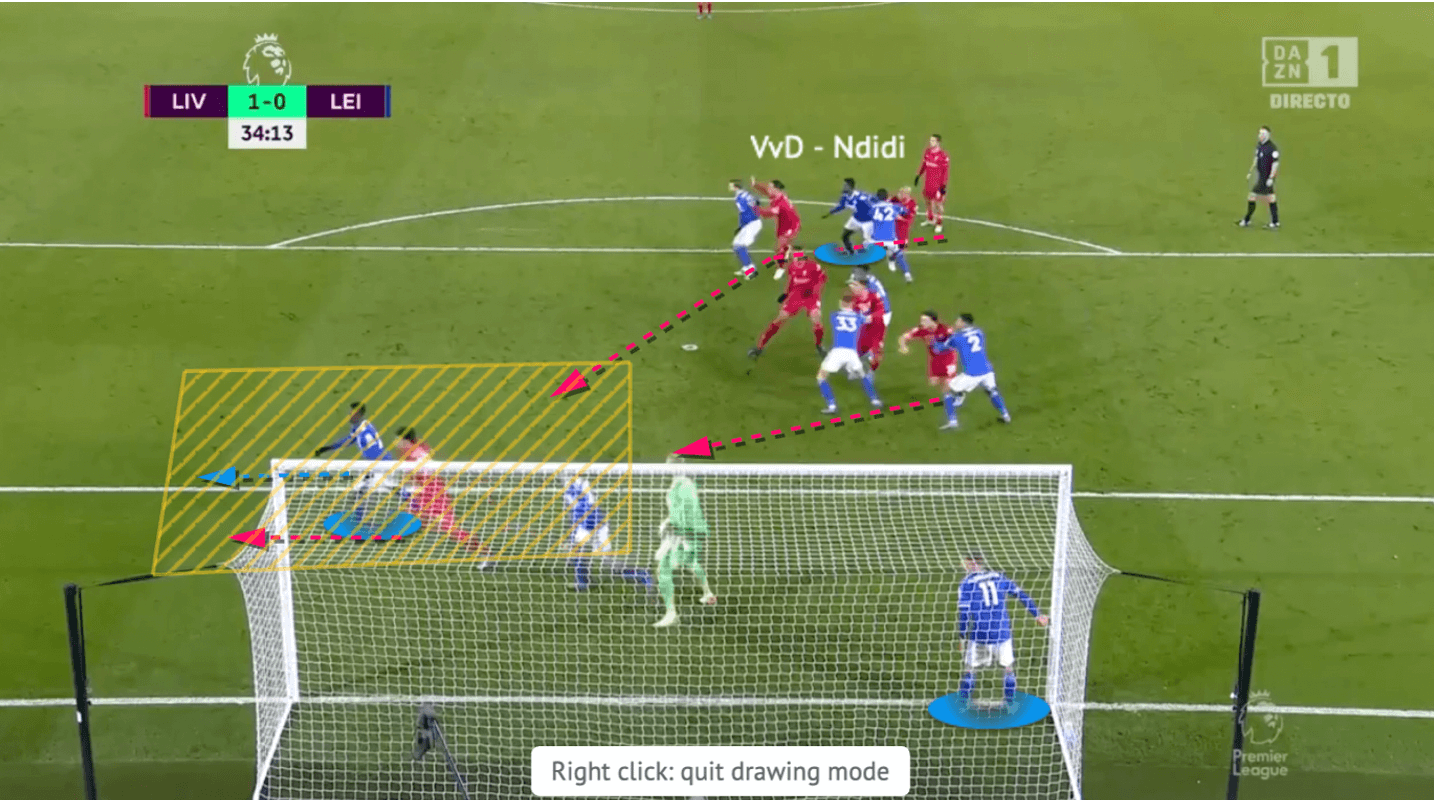

Leicester have been conceding goals and opportunities when their opponents exploited the six-yard line, the deliveries waws travelling to that zone and it was exposed defenders in it. The opponents also knew Schmeichel is going to cover a larger space, so it was easy to counter by placing a blocker to limit the movements of the keeper. Here, Liverpool put one player to bring the man-marker in front of Schmeichel initially, which created traffic and hindered the Schmeichel’s route if he was going out to punch.

But the Liverpool player in the six-yard box was also a decoy, when the delivery came, he would dash to the front post to fix the zonal defender’s attention, so Daka was not in a position to defend the six-yar box. The yellow zone was very exposed because Albrighton was the post-defender, it was only the keeper and Daka defending that space.

Liverpool also had a group of man-markers in deeper areas, which they vacated spaces in the centre and around the penalty spot so there were routes to run.

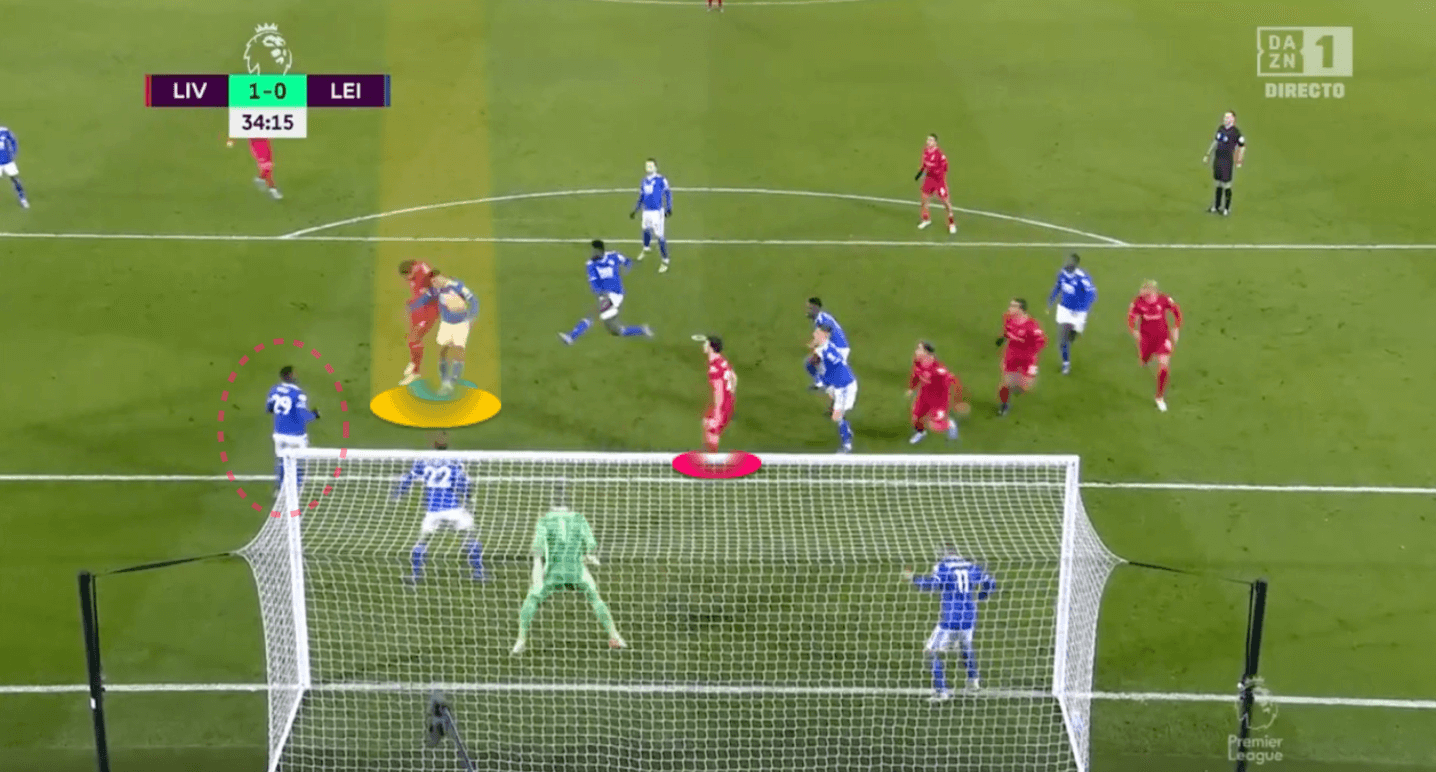

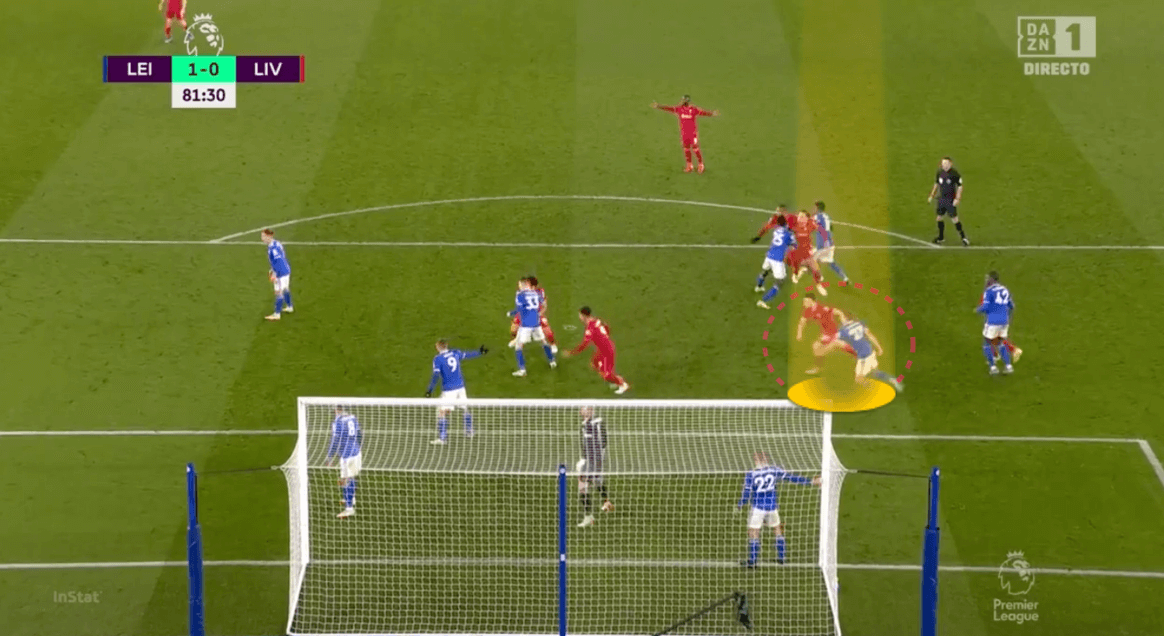

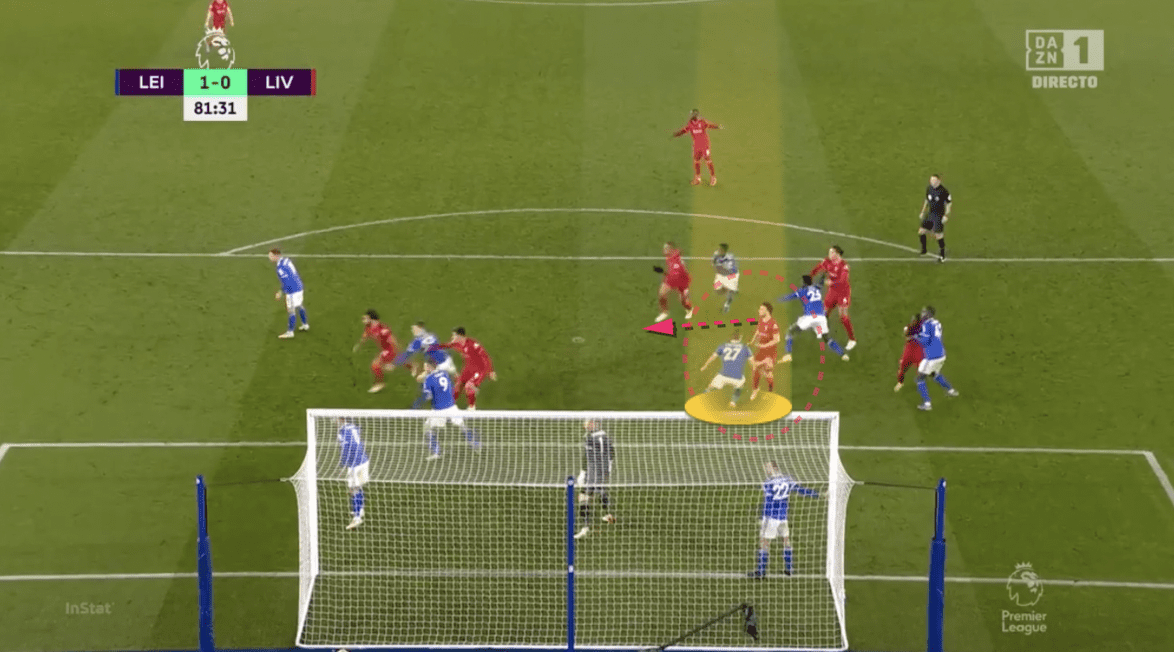

Then, you could see how quick van Dijk was able to get rid of his marker (Ndidi). When the Dutchman centre-back bypassed James Maddison, Ndidi was not even close to him. Apart from van Dijk, Jota was another player who attacked that yellow space, which was unprotected because the only zonal defender was taken away so easily. If he was defending that space, should he be that reactive to the runner to a larger extent?

If the opponent got away with the man-marker in this way, there was no pre-designed defender to handle the situation because there was no zonal defender, the defensive side must purely rely on the individual ability of each player’s 1v1 defending. Now Leicester was actually closer to a man-oriented scheme than a mixed or zonal system.

Here, since Daka was dragged away by the early runner, James Justin improvised by giving up his target (Jota), and competing with van Dijk because that was the instant danger. Expectedly, Justin was late to jump because he was not in the position before the ball arrived. Schmeichel made the first save, but unable to stop the Jota bounce. The Portuguese international was unmarked because Justin left him. Throughout the time, the post-player (Albrighton) could do nothing and watch the ball going in.

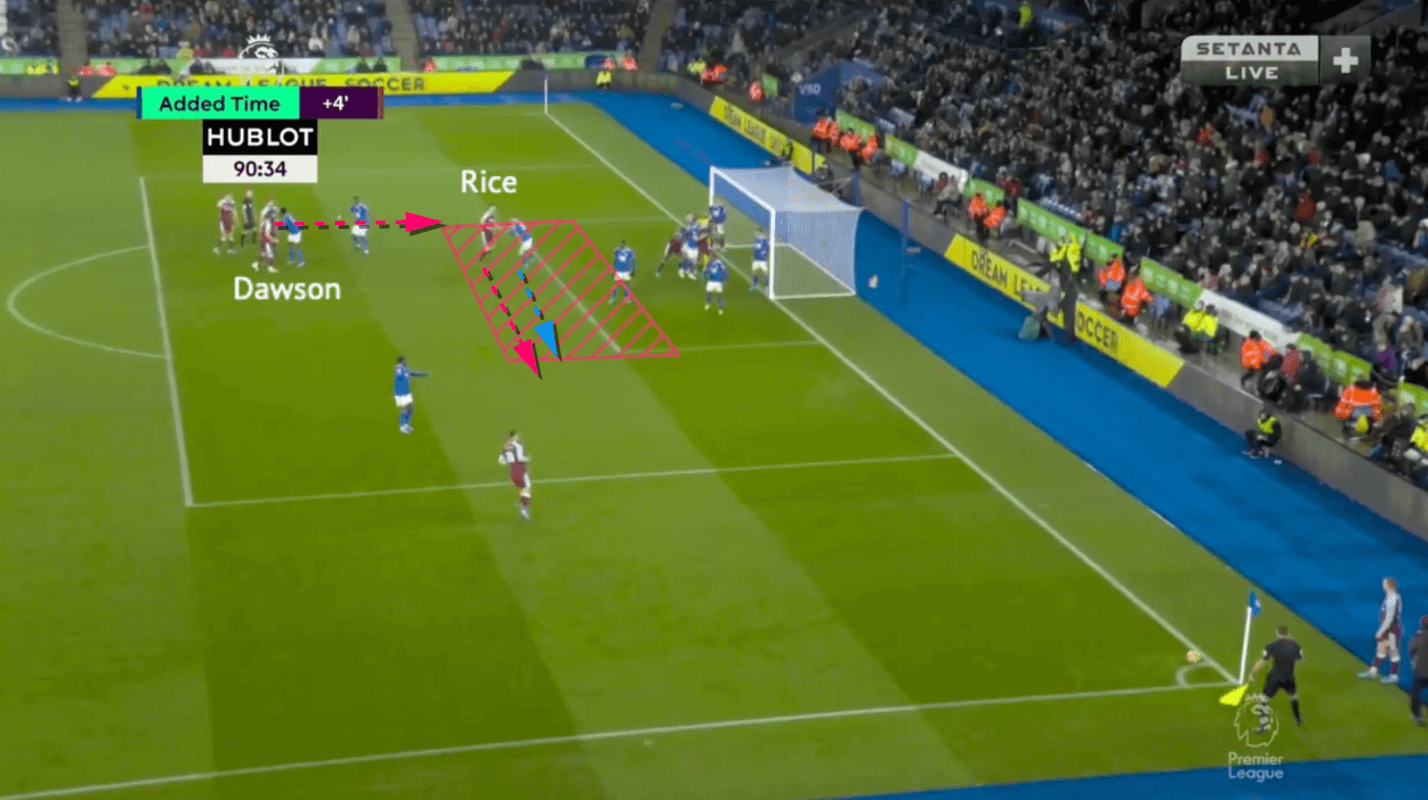

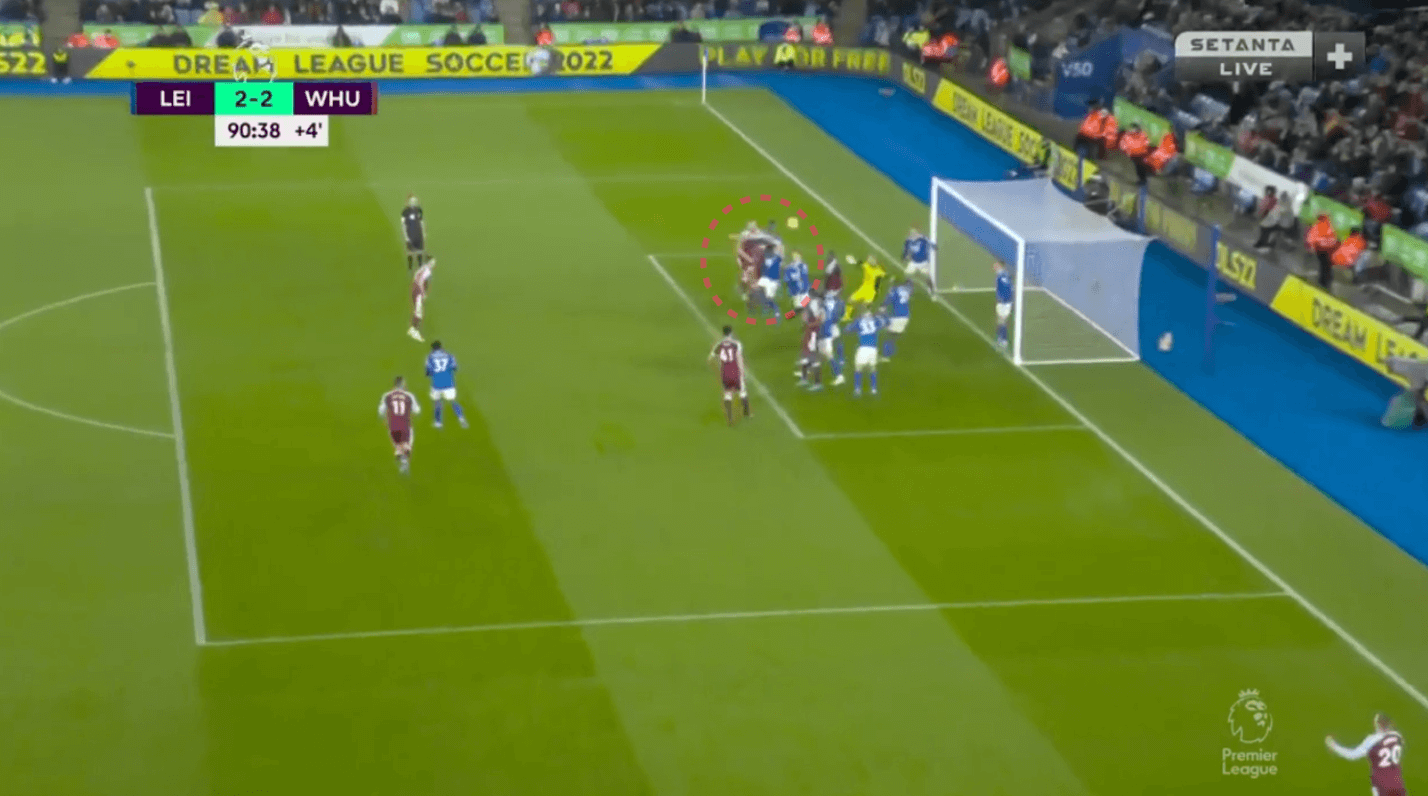

Knowing that Schmeichel has an important role in Leicester’s spatial coverage, West Ham also placed some players in front of the keeper to cause traffic. These two players also dragged the respective marker, making it extremely crowded around the keeper, Schmeichel could not come out to intervene even the delivery might be close.

Then, it was about the six-yard line we highlighted. Similar to Liverpool, the Hammer also delivered the ball into this space because that is the closest and most opened space towards the goal. With one simple lateral movement from Declan Rice to open up that space.

In the above image, Craig Dawson, arrived from deep to meet the delivery in that space. The distance was too close and hardly could the keeper react, let alone he was surrounded by several opponents.

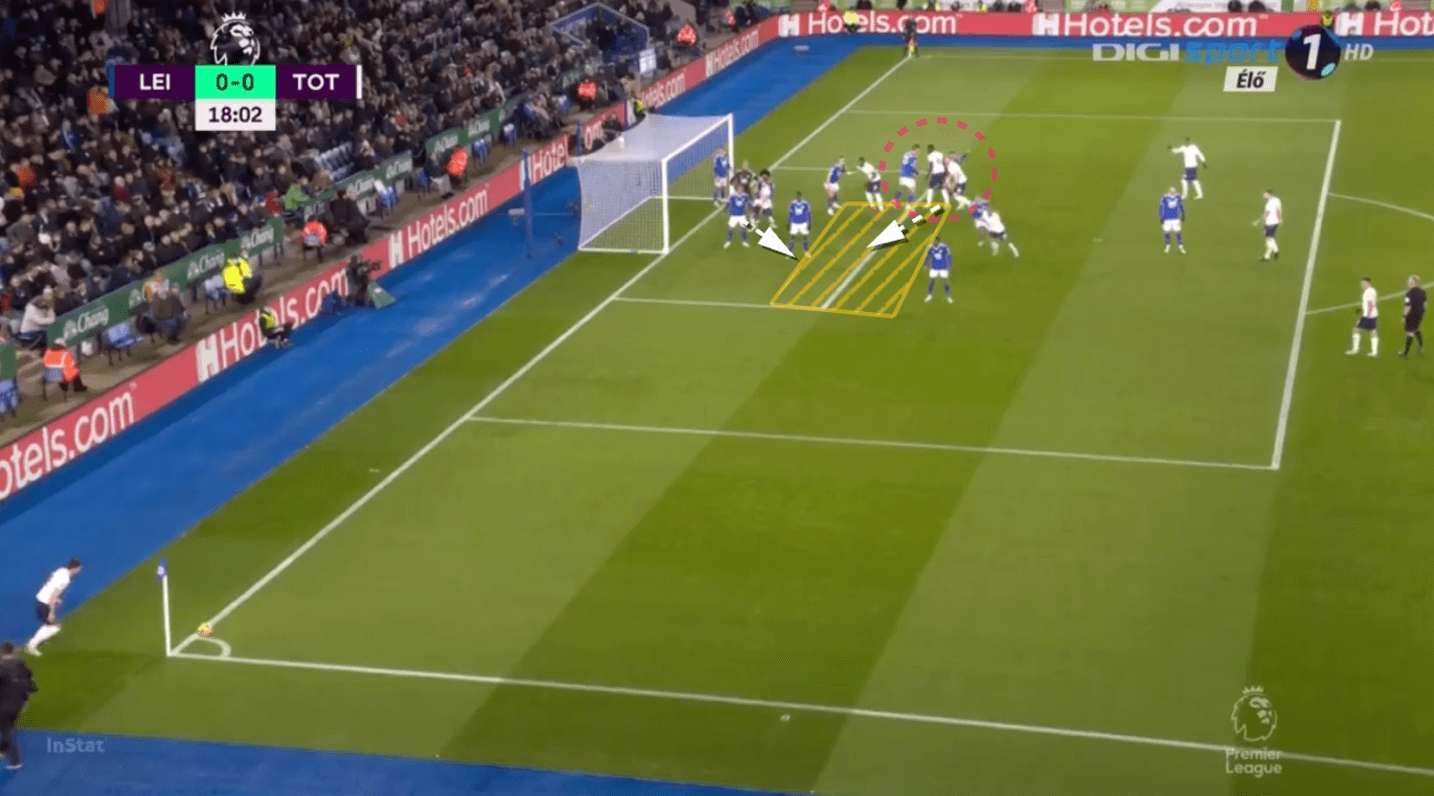

In the game against Tottenham, even Leicester did not concede the goal, it was also the same space that cost a dangerous opportunity. Framed in yellow, Tottenham vacated that space by the starting positions of players, Leicester could only let them because most players were man-markers now.

Then, with strategies such as blockers and screeners, creating traffics, Harry Kane arrived with a clear contact with the ball.

But man-marking is the real issue

After all descriptions on how Leicester adopted different systems to defend the corners but without clear improvements, maybe it was time to think again, what is the “real” issue in the team? We guessed the Foxes identified the issue as the zonal chain was not capable of defending spaces, so they removed the chain and increase the number of man-marker, plus the use of post-player(s) to simplify the system.

But after these experiences, we might conclude that the issue of Leicester’s corner defending were the weak man-marking de facto. How could the opponents be reaching those goal-scoring positions (i.e. six-yard line) that easily?

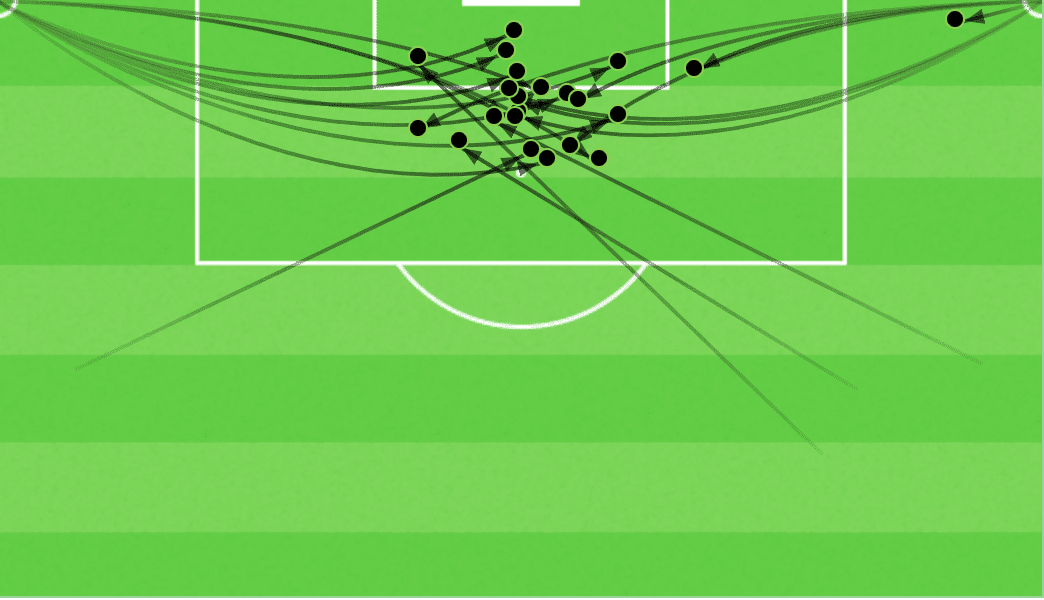

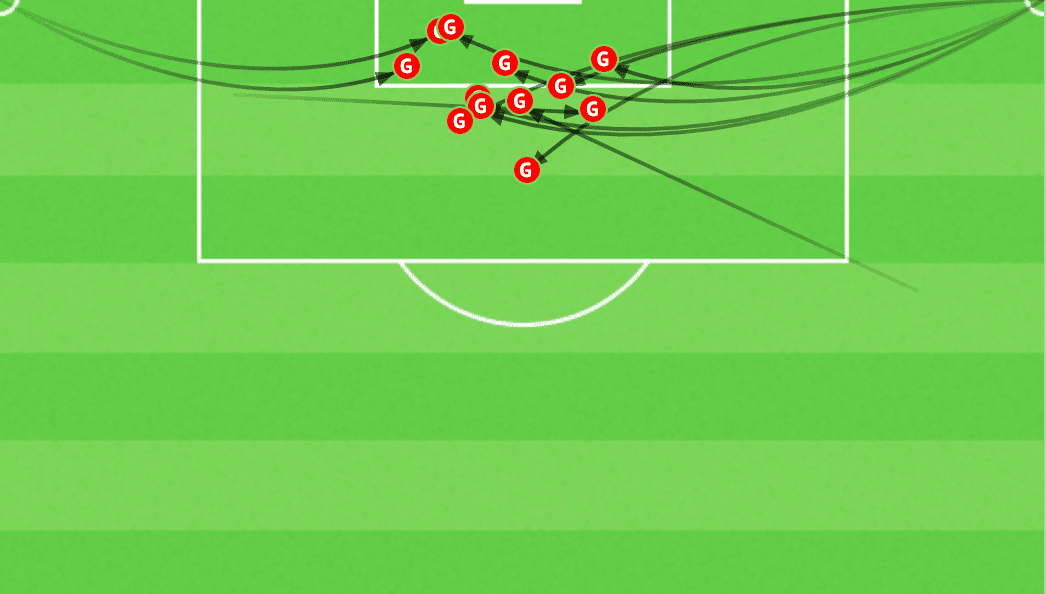

By looking at these graphs of Leicester, you could see how Leicester struggled in the defensive corners.

This is the shots conceded graph all defensive corners in their last 10 games. The positions they conceded the shots were at the centre, with a high proportion in the six-yard line, where the xG could be highest compared to spaces around the penalty spot.

If we looked at all their conceded goals in 2021/22 defensive corners, the most catastrophic area is around the same space we pointed out above. Only one of them

Hence, the question of Leicester’s corner defending is not about the zonal chain or spatial defence. For me, it is more about the man-markers, how could they lose the target that easily? Or, should there be any means to stop the oppositions from getting into those dangerous positions, especially now we saw a lot of the opponents began the runs from deep, that means they arrived in that area to attack the cross, not pre-occupying the space – there should be the way(s) to stop their arrivals.

We are showing two more opportunities they conceded this season under both systems, which reach the same conclusion, their problem is the very loose man-marking, plus a bit of lacking discipline in the zonal chain.

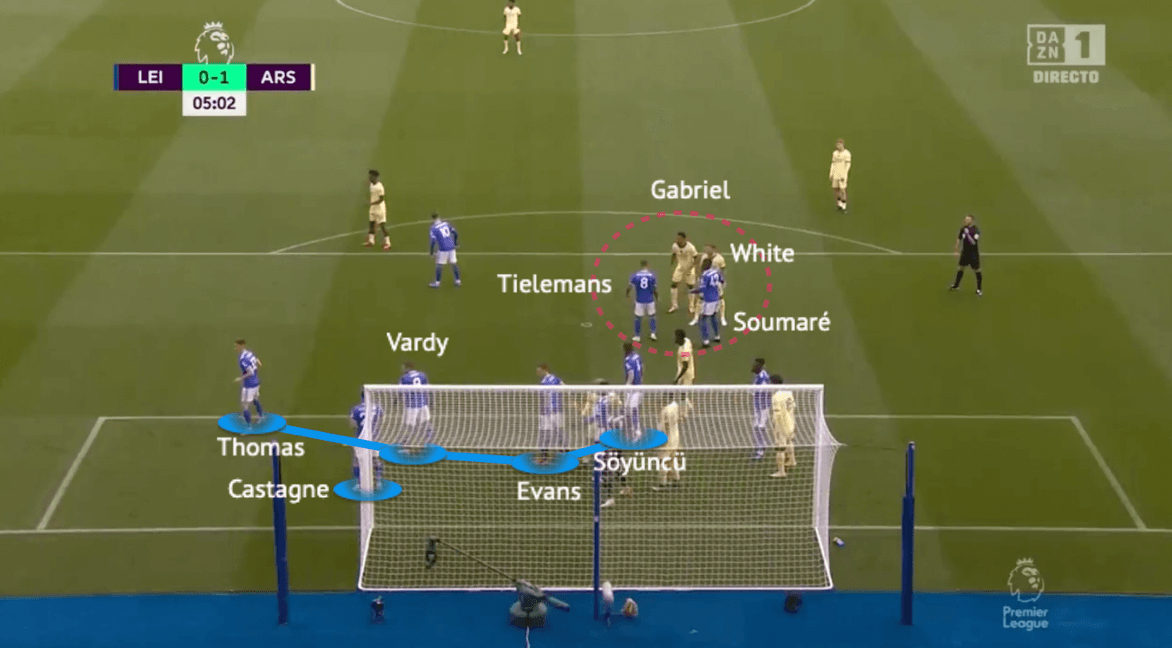

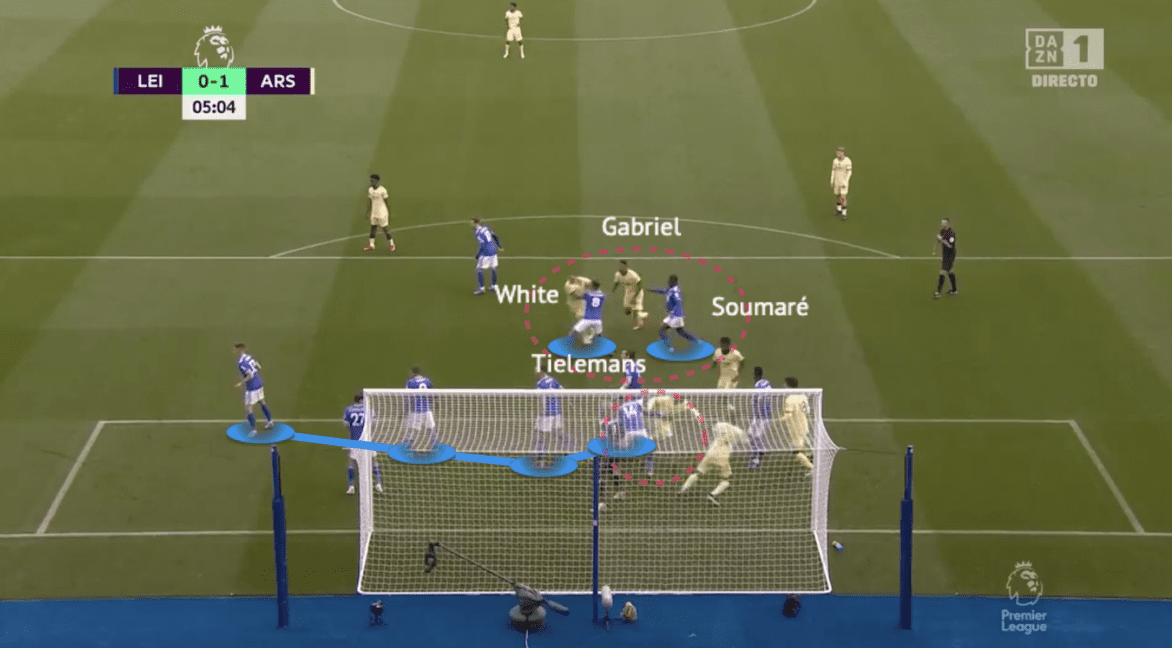

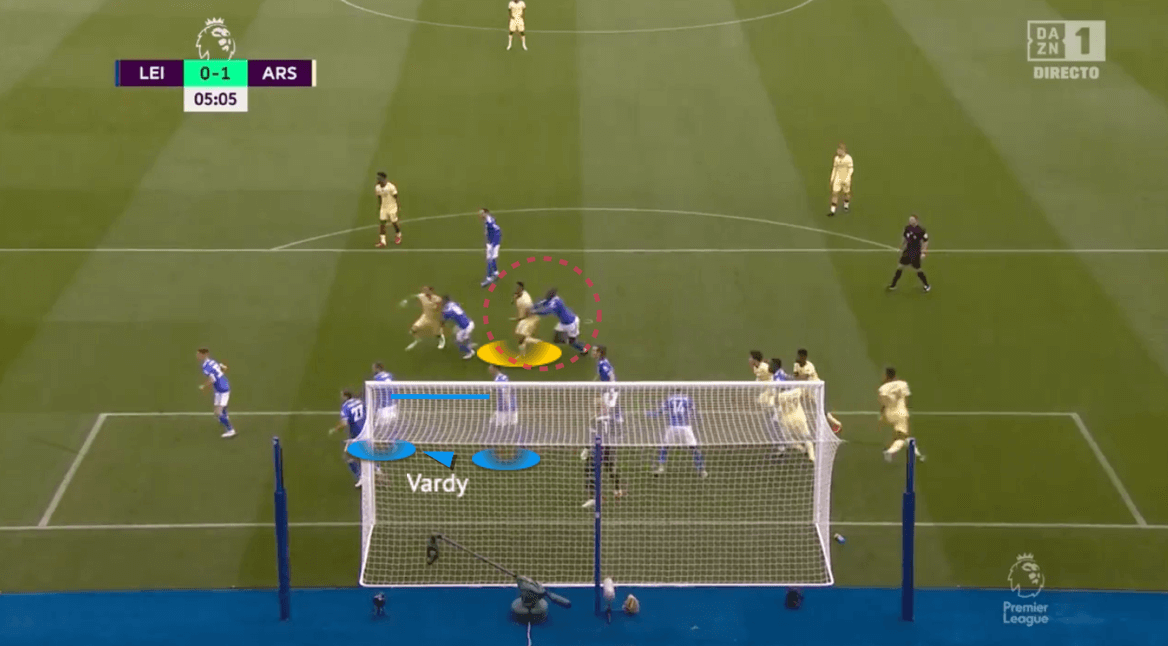

They conceded to Arsenal very early with the mixed approach this season. The zonal chain was formed by Thomas, Vardy, Evans, and Söyüncü, while Tielemans and Soumaré were the man-markers, dealing with the most dangerous opponents (Ben White and Gabriel Magalhães.

Arsenal attacked by the diverse timing to move, White first, so they moved Tielemans away and opened a lane for Gabriel to run. When the Brazilian centre-back was on his way to attack the cross, very early and before reaching the penalty spot, Soumaré already lost Gabriel.

This is what you can expect. Gabriel dominated a better position to attack the cross in front of the man-marker, Soumaré was not even close to jump with him.

Another player missing might be the zonal defender, the first one or two players in Leicester’s zonal chain always moved forward before the ball arrived. That increased the horizontal spaces between each player within the chain, and the opponents usually scored from there.

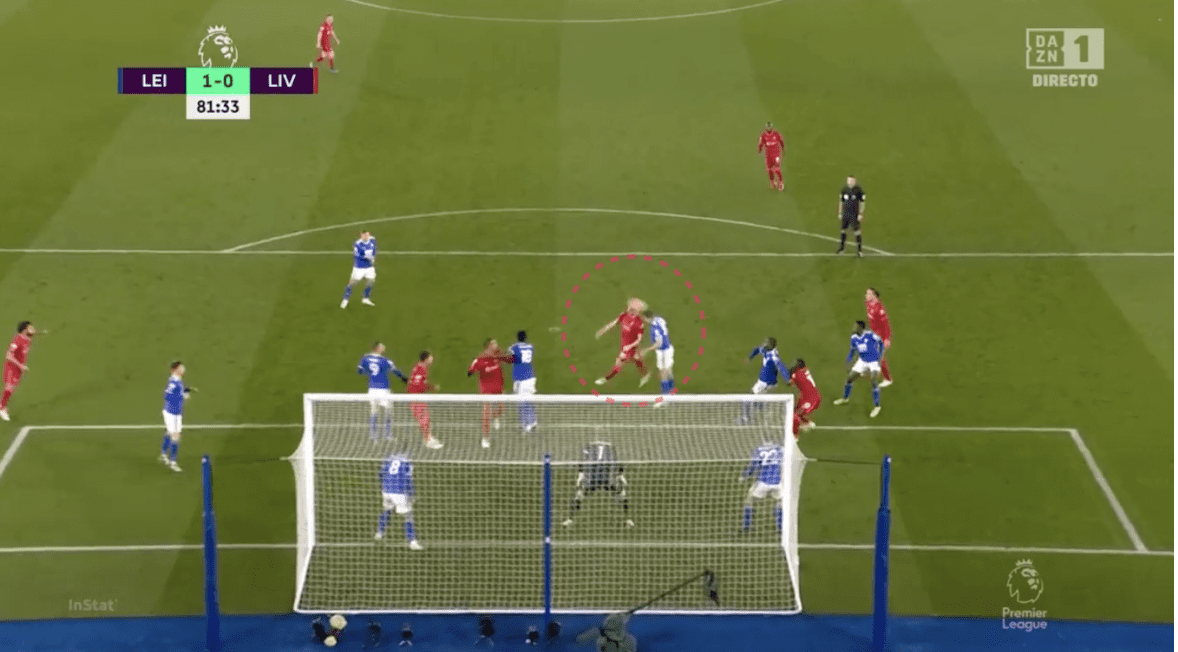

Another example in this situation against Liverpool can show the struggles of Leicester’s man-marking. We focused on the battle between Jota and Castagne in this case.

Initially, Jota and Castagne are on the far side and in a deeper area (above image).

The next image shows Jota moved first, he attacked the centre, the man-marker was forced to react, and he could only be reactive as this is the nature of man-marking.

But then Jota suddenly stopped, but as we said, man-marking is reactive, even it was within a second, Castagne was a moment later to react on the target’s behaviour to change his own approach. When Jota stopped, Castagne overran and he wanted to go back.

Jota is a very clever and mobile player in the penalty box, and knowing Castagne stopped, he suddenly attacked the cross and moved into the reverse direction of the marker as shown above.

There was no response, Castagne was always a beat slower than Jota in the entire process. When Jota leapt to head the ball when he was at the highest point, Castagne was not even reaching the same height because the timing to jump is too late.

Leicester almost conceded an equalizer here, it was all about the same issue, man-marking. And, in this case, is also about vacating the six-yard line as well.

Conclusion

It has been a difficult season for Leicester and Rodgers, they encountered a serious injury crisis in one or two positions, and as we have shown in this analysis, there are also very serious issues in the defensive corners. For me, there was no ultimate and perfect approach, there are only “optimal” and “suitable”. In Leicester’s context, it was a very difficult and complex problem given Rodgers had already thrown different solutions.

Maybe, the problem is not about the zonal chain, it is about why the opponents could easily run into those threatening positions. Compared to man-markers who need to both track targets and look for the ball, is a blocker a better option? There are at least 15+ games to play this season and we will see whether Leicester could fix it.

Comments