Last season, Lens returned to Ligue 1 after a five-season absence and manager Franck Haise helped them to achieve their best top-flight finish since the 2006/07 season by guiding them to seventh place. The Pas-de-Calais-based club did lose three and draw one of their final four league games last season but they’ve started this season far better than they finished the last one — which was, overall, an impressive campaign. Despite selling talented 21-year-old centre-back Loïc Badé to Ligue 1 rivals Rennes for €17m in the summer, they’ve won five, drawn three and lost just one of their first nine Ligue 1 games this season, which leaves them sitting in second place at present, trailing only league leaders Paris Saint-Germain.

Under Haise, Lens have almost exclusively played with a base 3-4-1-2 shape and that has continued into the 2021/22 season. The wing-backs naturally provide the width for Lens within this shape and the importance of those players’ roles can’t be understated — they’re key men for Lens, especially in attacking phases. After joining Sang et Or from now-Bundesliga side Arminia Bielefeld last summer, right wing-back Jonathan Clauss ended the 2020/21 season as Lens’ highest assist provider, with six Ligue 1 assists. While the Frenchman had experience of playing as a right-back and a right wing-back before, in the season prior to joining the Pas-de-Calais side, Clauss had primarily been deployed as a right-winger in a 4-3-3 shape.

This season, Clauss has continued to perform well in attack, while he and the team have also been helped by the arrival of Poland international, Przemysław Frankowski, who joined Lens this summer from MLS side Chicago Fire for €2.3m. Frankowski is a versatile player but similar to Clauss, the right-footed Poland international had primarily played as a right-winger before he arrived at Stade Bollaert-Delelis this summer. Frankowski may have been signed as a replacement for Clément Michelin, Lens’ former back-up right wing-back who left the club to join AEK Athens this summer. However, with Clauss in fine form, Frankowski has managed to force his way into Haise’s first XI via the left wing-back position — an unfamiliar role for him in which he’s managed to thrive this term.

Lens’ wing-back recruitment alone highlights a lot about how Haise views these players as part of his squad. The signings of Clauss and Frankowski — two former wingers who have mainly started in the wing-back positions for Sang et Or this term — indicate that the 50-year-old coach is more concerned with the attacking output from these positions, as opposed to the defensive output. Of course, Lens’ wing-backs do still need to tick certain boxes from a defensive standpoint, but the wing-backs are, first and foremost, viewed as attackers in Haise’s system which is why Frankowski and Clauss, along with centre-forward Florian Sotoca, are currently Sang et Or’s joint-top assist providers for the 2021/22 Ligue 1 campaign (with three assists each) — campaign in which Lens have performed exceptionally well, so far.

This tactical analysis and team-focused scout report provides some deeper insight into the wing-backs’ attacking roles in Lens’ system. My tactical analysis highlights some important aspects of the wing-backs’ roles in different phases of play and highlights how newcomer Frankowski, who was recently labelled ‘one to watch’ by Ligue 1’s official website, has well and truly hit the ground running as a key part of Haise’s tactics.

Early possession phases

As mentioned in the introduction to this analysis, the wing-backs naturally provide the width for Lens in possession. Lens’ wing-backs get extremely wide right from the very beginning of their attacks. From goal-kicks, Haise likes the two wide men to get chalk on their boots and stand on the sideline.

While the rest of Lens’ players look to create central domination to progress from the centre-backs into midfield — with one of the two central midfielders typically dropping deeper to give the centre-backs a short passing option and the other one typically positioning himself higher, often ending up in-line with the number ‘10’ who’ll drop slightly deeper — the wing-backs operate much differently. They will look to create passing angles for the teammate in possession via their positioning, their first port of call is to get as wide as possible to either stretch the opposition’s defensive shape or, otherwise, find space out wide where they can receive the ball from a midfielder/defender and progress.

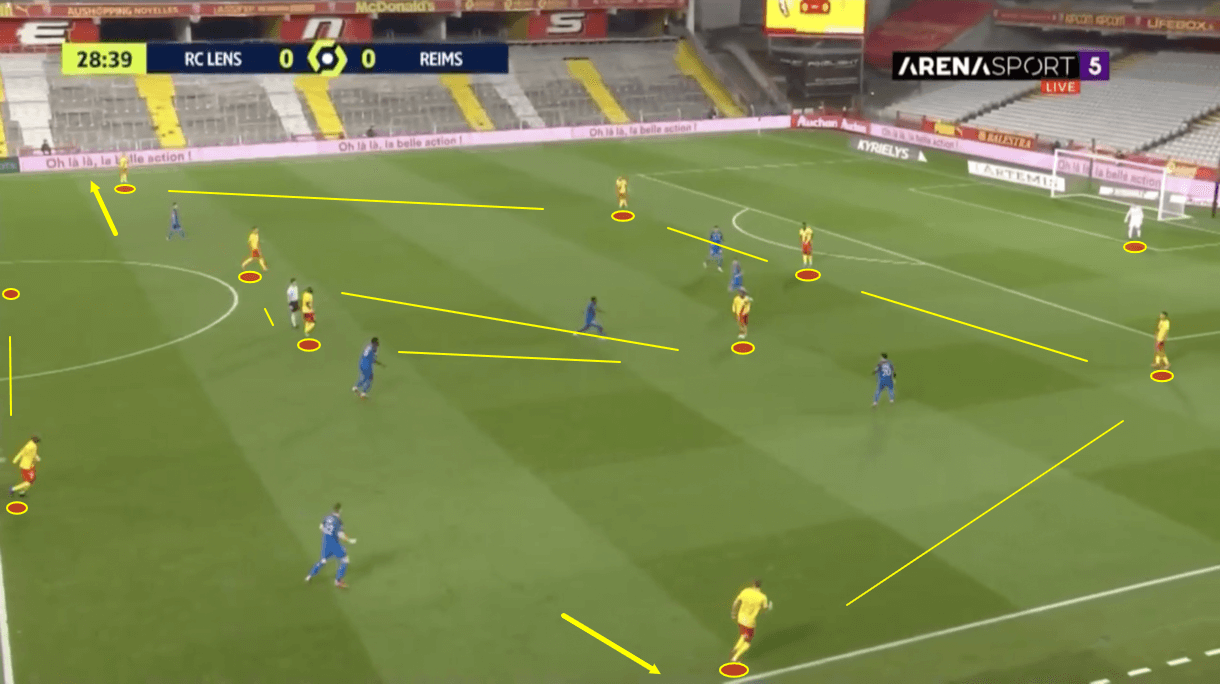

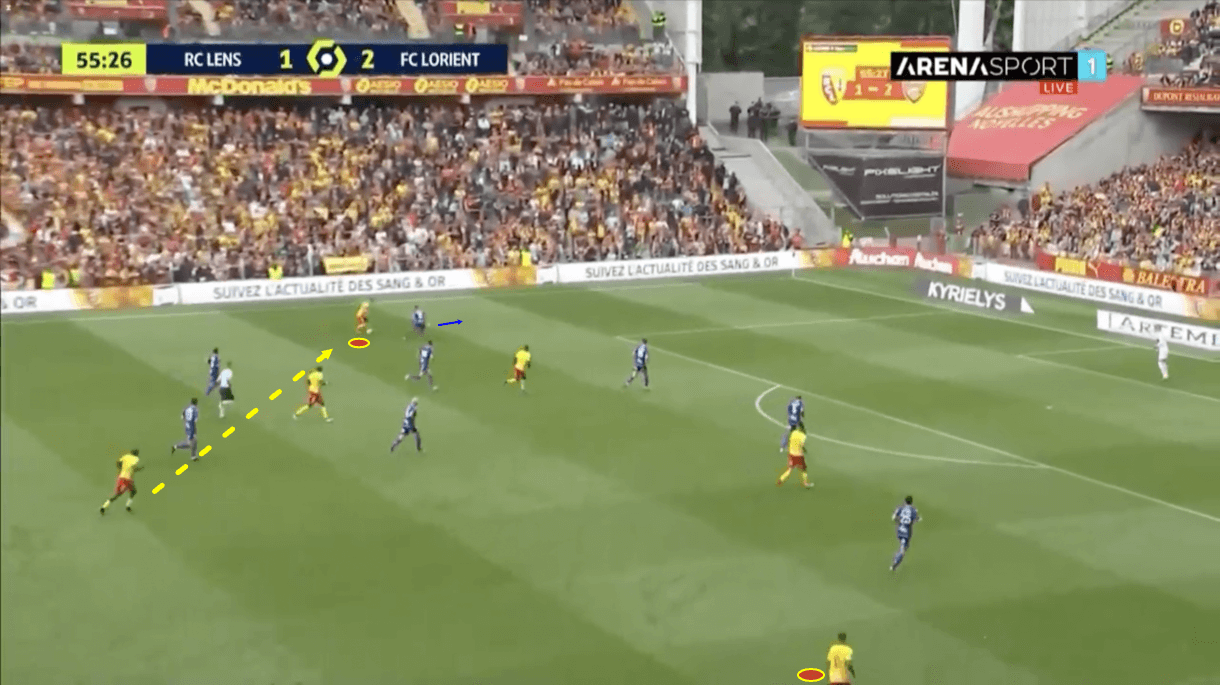

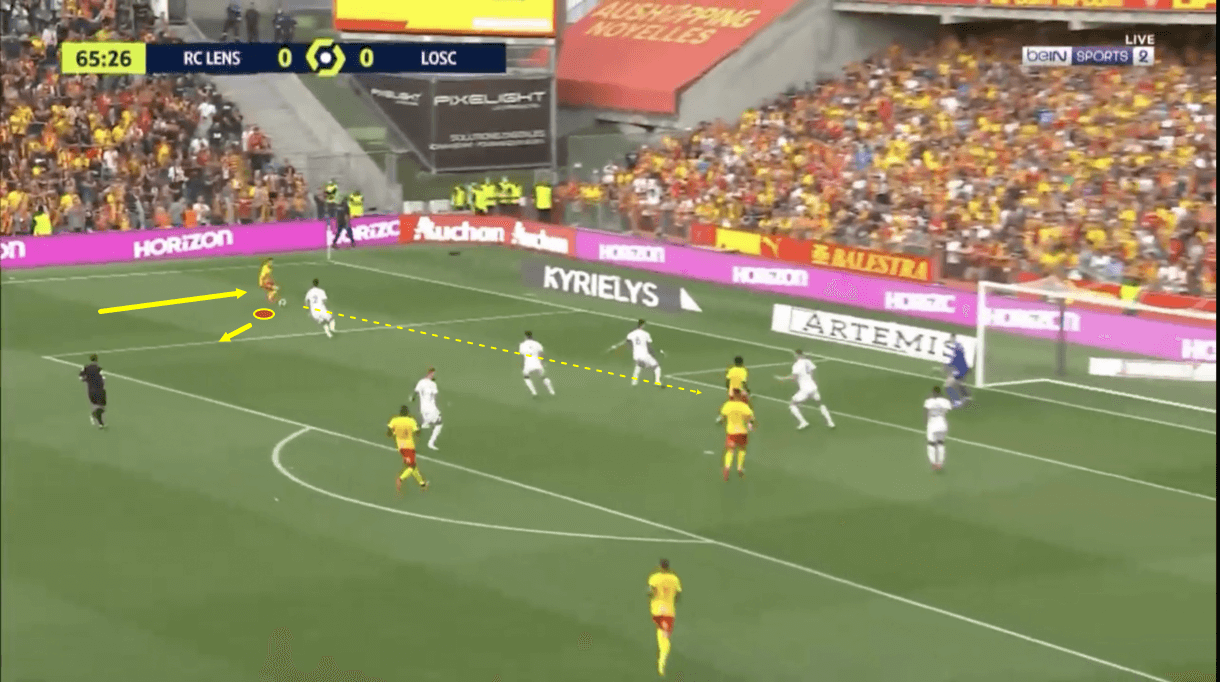

We see an example of Lens’ typical offensive shape during an early possession phase in figure 1. Here, we see their 3-4-1-2 shaping up as described in the previous paragraph, with the back three providing a base for the team while sitting deep and offering protection in central areas around the box in case possession is lost. Meanwhile, one central midfielder dropped deep to receive from the backline while the other advanced to provide his midfield partner with an additional forward passing option. The most important thing for us to note, however, is the wing-backs’ positioning. We can see that both men shifted very wide, getting their heels on the sideline, with left wing-back Frankowski creating an angle to receive a short pass from the midfielder in possession.

Frankowski’s wide positioning and movement to create a passing angle proves key for Lens’ ball progression in this example as play moves on. Lens’ left-forward can be seen dropping into the left half-space channel here but the opposition’s right-back is drawn away from this channel by Frankowski’s positioning and movement. This opens up a passing lane for Lens, allowing the deepest midfielder to connect with the left-forward via a line-breaking pass that progresses Sang et Or into the middle third of the pitch.

This passage of play highlights why Lens’ wing-backs’ positioning and movement, as previously discussed, is so important for Haise’s side in early possession phases. Figure 1 shows how Lens’ wing-backs stretch the opposition’s defence and create gaps for their teammates to exploit.

Additionally, it’s common to see Lens’ wing-backs get into a narrower position during pressing phases in more advanced areas of the pitch, as well as when contesting an aerial duel. In the case of the former, Lens’ midfielders can get drawn higher up the pitch and as a result, the wing-backs move centrally to provide cover and prevent the opposition from playing through their press and breaking through the centre. As we’ll look at in greater detail later on in this tactical analysis piece, Haise is happy for his wing-backs to allow space to open on the far wing during aggressive pressing phases so that the centre of the pitch — the most dangerous area of the pitch — can be reinforced and protected. In the case of the latter (contesting an aerial duel) Lens like to have more bodies positioned around the player contesting the aerial duel — typically someone positioned centrally — to improve their chances of winning the second ball by congesting the drop zone with Sang et Or bodies.

When Lens regain possession after an aggressive press or an aerial duel, though, the wing-backs will spring straight back out to the sideline. Lens’ wing-backs typically waste no time in getting into their extremely wide position during possession phases. They know their role very well and are well prepared to run to the sideline while their side transitions to attack.

The final third

As with both current starting wing-backs having been wingers in a previous life would suggest, Lens’ wing-backs are very active in their team’s game inside the final third. Sang et Or have been proficient in the final third, in general, this season. Their 16 goals in nine games so far makes them the third-highest goalscorers in France’s top-flight right now, along with Montpellier and trailing only PSG and Nice.

They’ve generated the fifth-highest xG (14.85) of any Ligue 1 side this season, trailing star-studded PSG in fourth by just 0.12 xG, while they’ve scored just one of their 16 goals from outside the box.

The arrival of Frankowski has changed the extent of the wing-backs’ involvement in Lens’ attack to an extent. Comparing the new man to Massadio Haidara, who’d been primarily starting at left wing-back last season before Frankowski’s arrival, we notice some similarities with both men being happy to take on opposition defenders 1v1. Dribbling is one of Haidara’s strong points and last season, the Malian engaged in 1.96 dribbles per 90 with a very positive 61.22% success rate. Last season right wing-back Clauss engaged in 2.35 dribbles per 90 with a 53.62% success rate while this season, the right wing-back has engaged in 2.26 dribbles per 90 with a 57.89% success rate. Meanwhile, after his arrival at Lens, Frankowski has taken on 1.94 dribbles per 90 this season with a 57.14% success rate.

In general, Lens aren’t one of Ligue 1’s most frequent dribblers, but they have some decent options for delivering success in the form of their wing-backs.

Frankowski and Haidara differ in some areas too, two of which I’ll focus on here: shots and crosses. Firstly, while Haidara took 0.48 shots per 90 with 41.67% accuracy last season, Frankowski has taken 0.97 shots per 90 with 42.86% accuracy this season. So, the new man has been a more high-volume shooter than Haidara at the left wing-back position thus far.

The Poland international has also proven to be a higher volume crosser than Haidara so far. In general, Lens do tend to cross the ball a lot. They’ve made the fifth-most crosses (14.08 per 90) of any Ligue 1 side this season, with the third-best crossing accuracy (38%). Both last season and this one, Clauss has been Lens’ most frequent crosser. He ended last season with 5.28 crosses per 90 in the league and 34.19% crossing accuracy, while this season, he’s made 5.11 crosses per 90 with 32.56% accuracy.

However, last season, Haidara made 1.96 crosses per 90, ranking him sixth in this particular area, with 32.65% accuracy, while this season, Frankowski has made the second-most crosses of any Lens player (3.19 per 90) with 34.78% accuracy. It’s clear from Clauss’ performance in this area that crossing can be a major part of the wing-backs roles’ at Lens and the arrival of Frankowski to play at left wing-back has spread the crossing load a bit more evenly across both wings. It’s worth noting that Frankowski has made 0.97 key passes per 90 this season — the second-most of any Lens player — while Haidara made just 0.28 per 90 last season, a significant amount lower. Some of these key passes will have come from Frankowski’s impressive crossing quality. Sang et Or have reaped the rewards of Frankowski’s increased crossing over Haidara with the Polish wide man already making two more league assists this season than the Malian made in all of last season, an equal number to Clauss on the right.

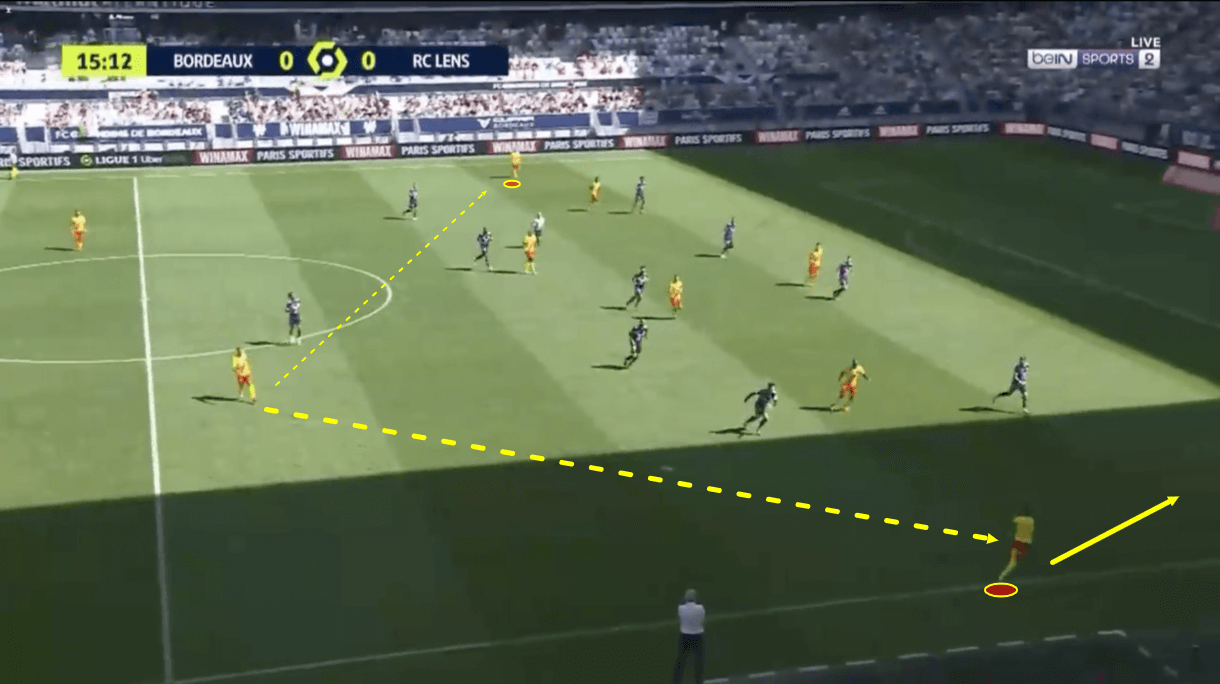

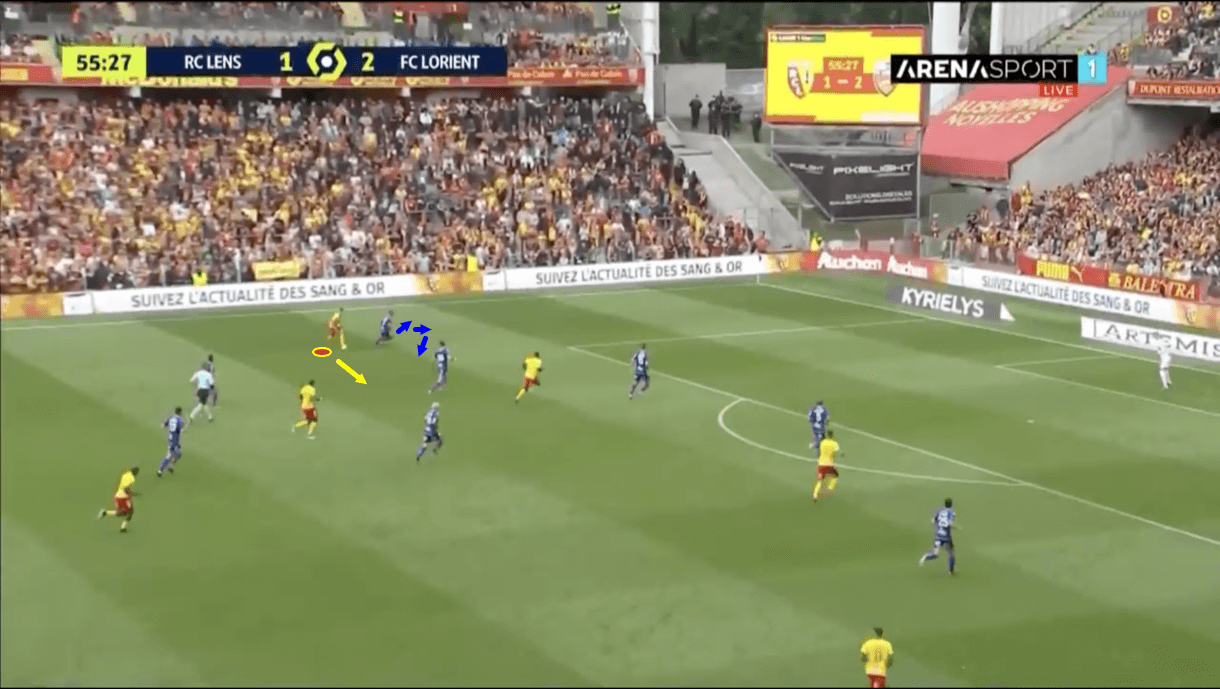

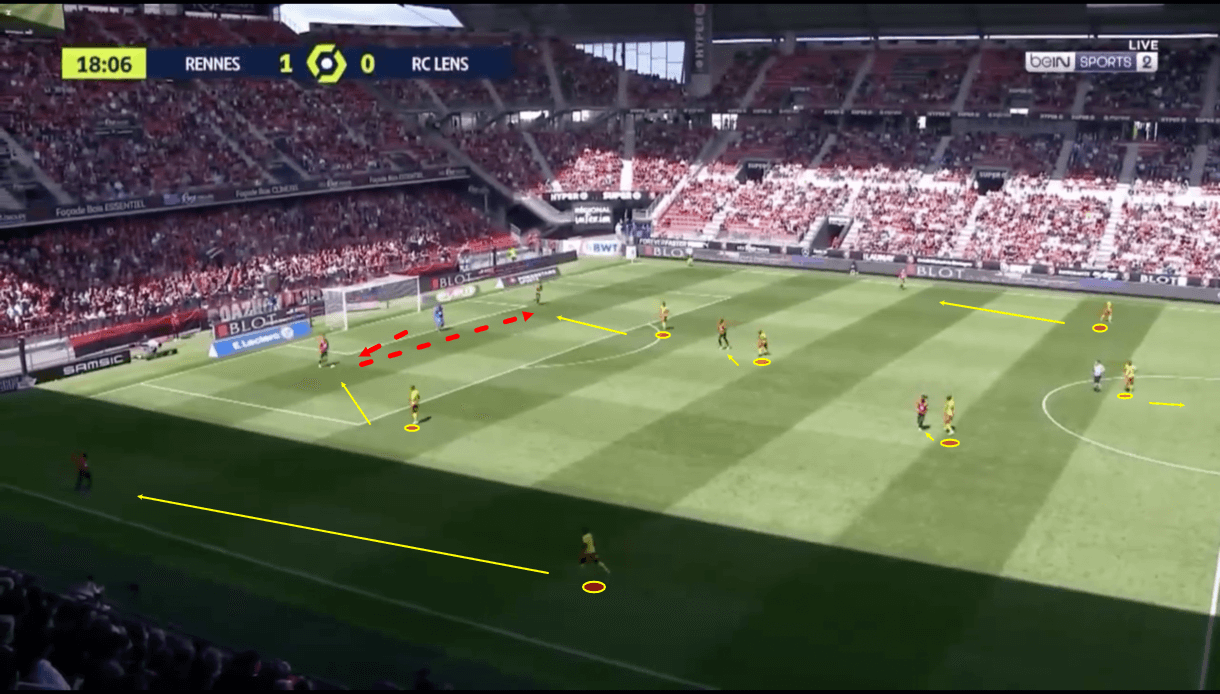

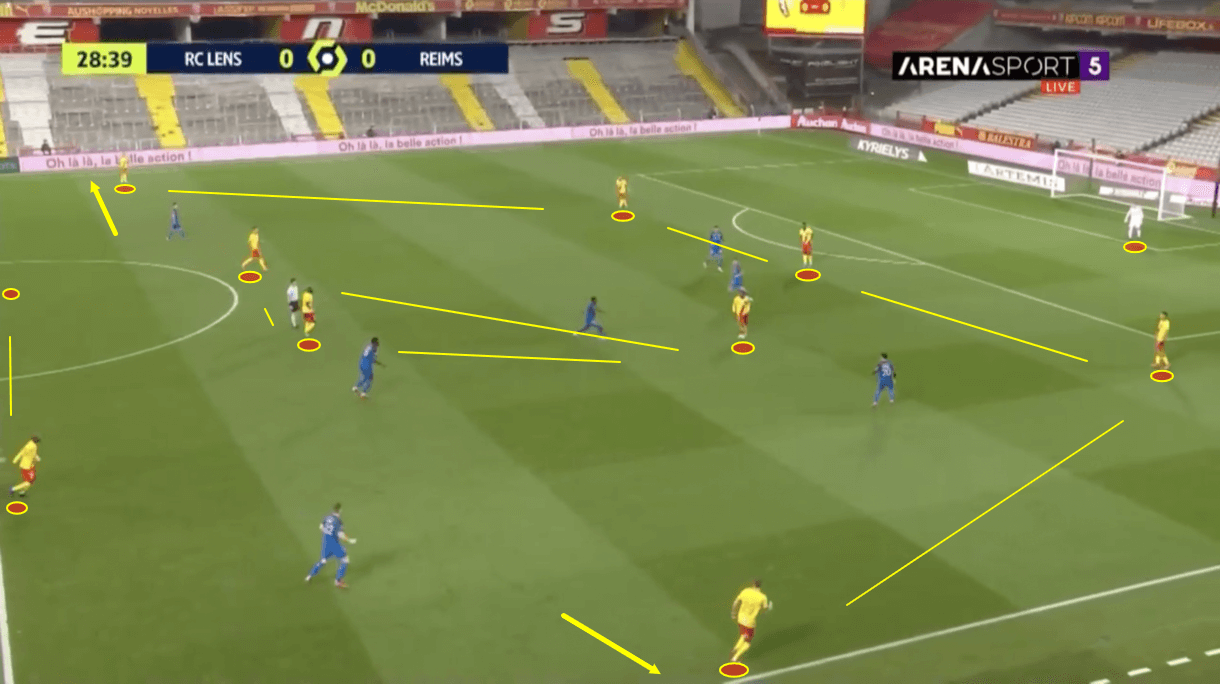

Figure 2 shows an example of Lens’ typical attacking shape when they progress into the opposition’s half. All of Lens’ players except for one centre-back who’s positioned slightly deeper, are in the picture here, including the two wing-backs who can still be seen on the outside of their side’s offensive shape, attempting to either stretch the opposition and create space for the more central players or exploit space themselves out wide.

Here, one of Lens’ wide centre-backs is on the ball, attempting to progress Sang et Or upfield. There are five players positioned ahead of them centrally — the two strikers and three midfielders — and the positioning of these players in central spaces manages to successfully control the opposition’s defensive shape, pinning players centrally as if they move out wider to cover the wing-backs or press higher to challenge the ball carrier, space will open for the central Lens players to exploit.

This can lead to the ball carrier enjoying too much time on the ball, allowing him to decide between switching play to the opposite wing or playing a simpler through ball to the near-sided wing-back, the latter of which is what happened in this particular example, as play moves on from this image.

It’s very common to see Lens play this pass to move into the final third. If they can progress through the centre, then they will, and if central space opens up, it will often be because of the wing-backs stretching the opposition’s shape. However, If the opposition stay narrow to protect the centre, which is often the case, then Lens are happy to play through the wing-backs as we see here to progress into the final third, where these players can then try to create something, generally via a cross.

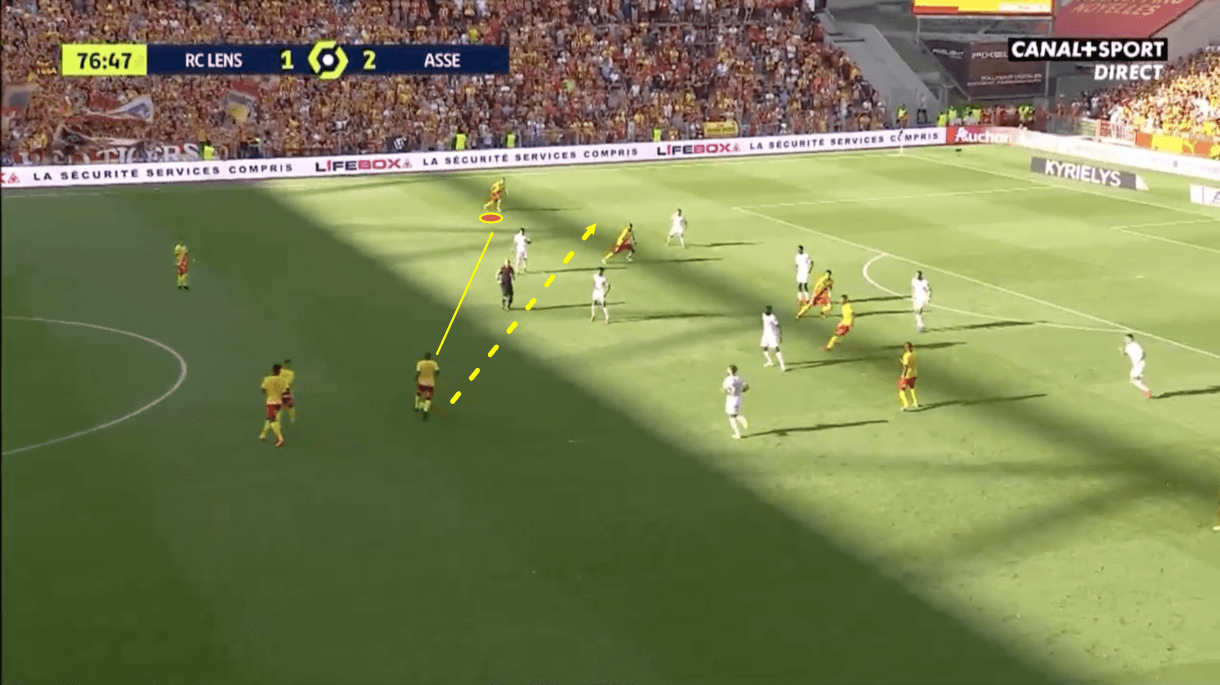

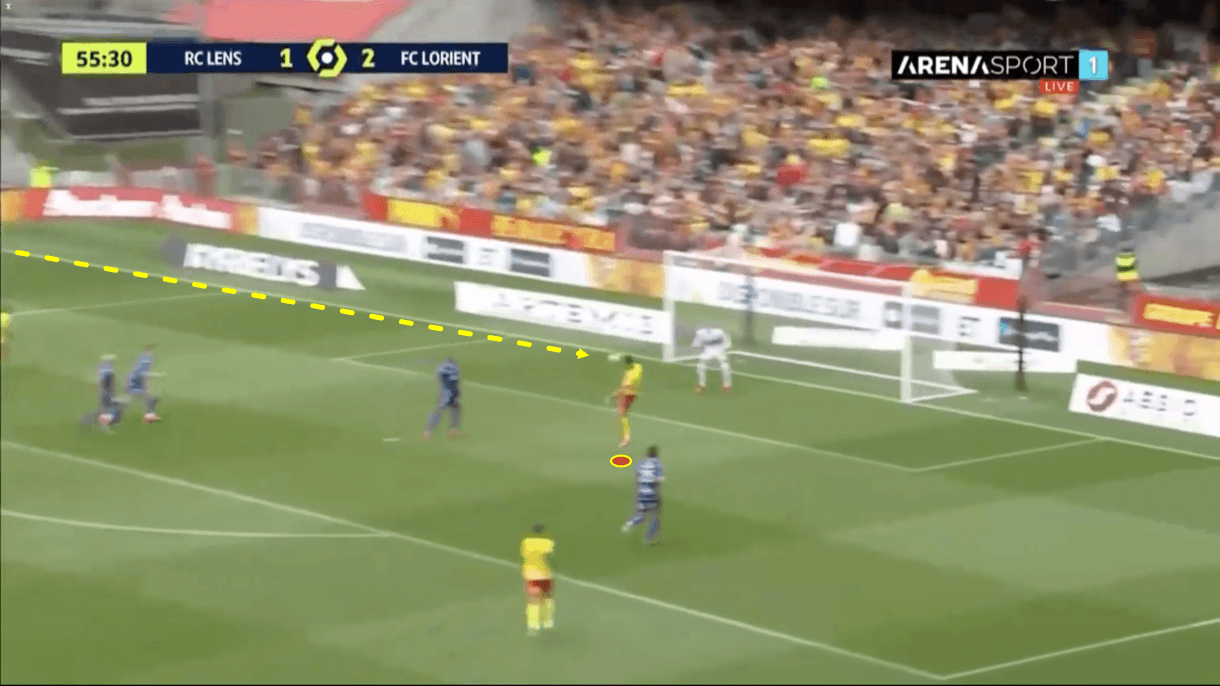

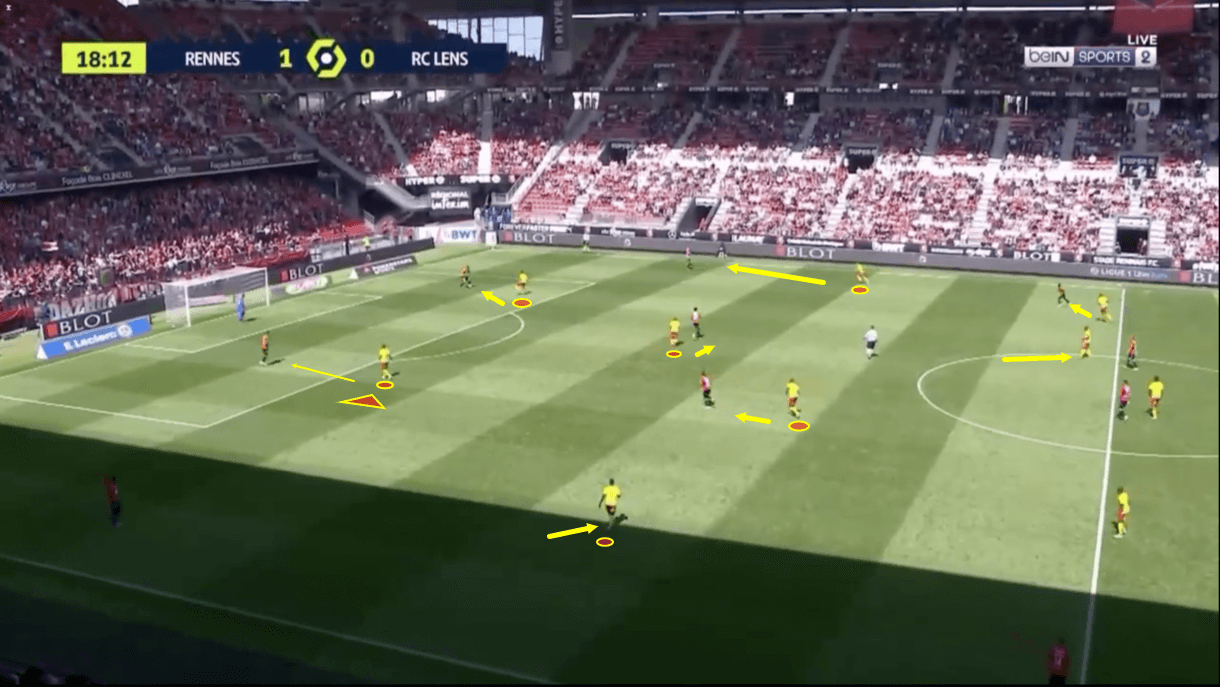

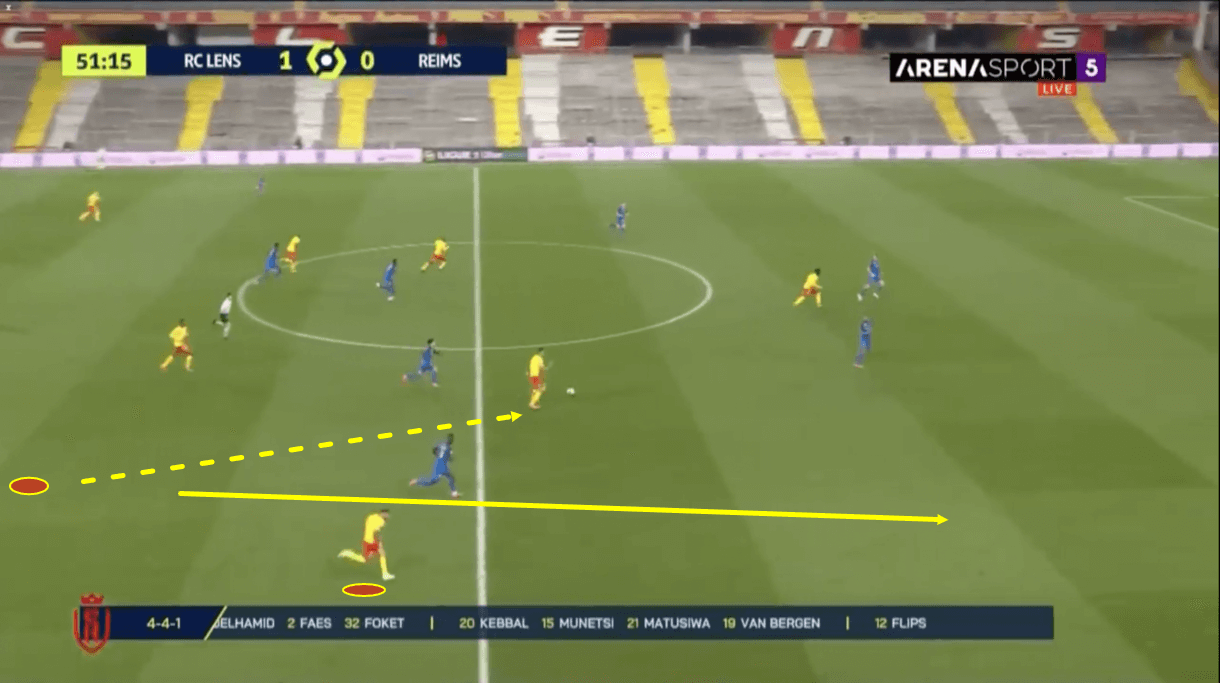

In figure 3, we see an example of the pass being played from midfield to the opposite wing — Frankowski’s wing. Unlike Haidara, who’s left-footed, Frankowski is right-footed which is quite rare for a left wing-back. These players will generally be left-footed to carry the ball on the outside of a particular wing. It’s natural for the wing-backs to stay very wide all of the time while forwards and midfielders occupy the centre and half-spaces, which also makes it very natural for them to receive the ball on the same foot as the wing they’re on, especially when receiving a forward pass to run onto.

Last season, it was common to see Haidara operate like this inside the final third. He would generally receive the ball in very wide positions on his stronger left foot before carrying it towards the byline to cross. In deeper areas, Haidara tended to get narrower a lot of the time, but strictly speaking about the final third, he generally stayed very wide. With Frankowski, he’ll always stay very wide in deeper positions, but it’s somewhat common to see him move inside in the final third, which figure 3 provides an example of. Here, the opposition’s right-back is pinned in a narrow position by the attacker in the half-space, which creates space for Frankowski to target with his run inside from the left wing. As play moves on from this image, the ball is lightly chipped over the top for Frankowski to run onto and collect just behind the right-back while moving inside from the wide position we see him occupying above.

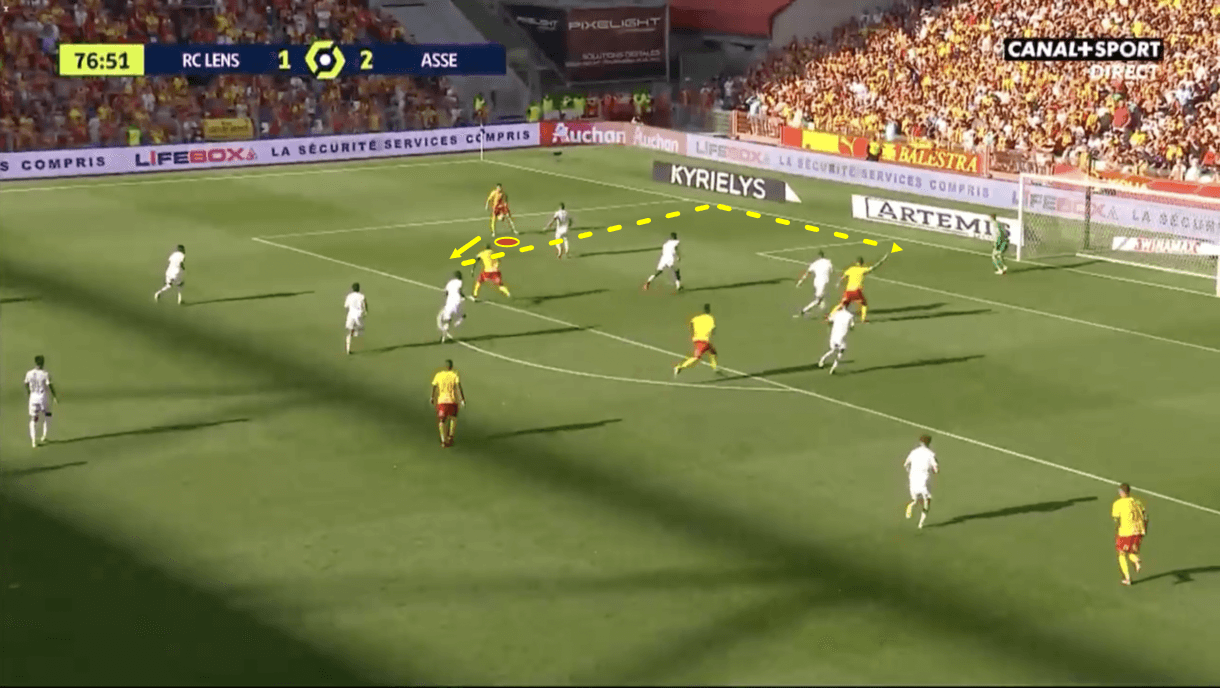

Then, in figure 4, we see how Frankowski ends up inside the box, as opposed to a wider position. After collecting the ball over the top and forcing the opposition’s backline to drop deeper, Frankowski has two options. He can either carry the ball towards the byline, taking it onto his weaker left foot and playing a more natural winger’s cross, or he can cut back onto his stronger right foot to play an inswinging cross. As play moves on from figure 4, we see that he opts for the latter, quickly knocking the ball towards the edge of the box via the outside of his right boot before playing an inswinging cross towards the centre-forward. While Frankowski is comfortable with using his weaker left foot as a crossing tool, it’s most common to see him cut back onto his stronger right foot as we see here, which is somewhat unique for a wing-back.

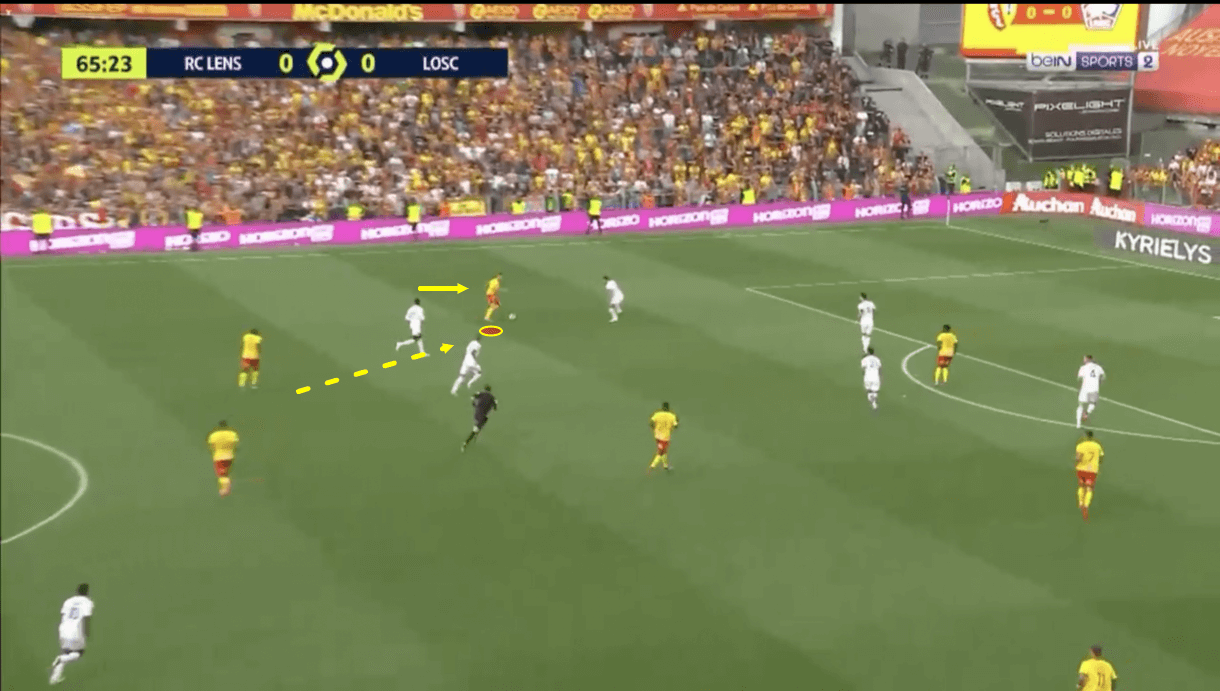

Just before figure 5, Frankowski received a pass out wide on the left wing from a central midfielder again. As play moves on, he opted to take on the opposition’s right-back, who was attracted towards him, as he looked to progress into the opposition’s box. Again, being a wing-back with such a wide starting position, it’s unusual for the Lens man to cut inside as he does — even though we’ve become well used to seeing wingers cut inside. Frankowski can use this, as well as his capability to take the ball on the outside at times to mix things up, to his advantage to keep opposition defenders uncertain about his next move.

In figure 5, we see how Frankowski’s movement can be unpredictable because the opposition right-back’s body positioning is not ideal for defending against an attacker who wants to cut inside. The defender is positioned a few steps closer to his goal than Frankowski but is facing the sideline. If the Lens man wanted to progress down the wing, then this body positioning would be fine, as the defender is prepared to stop the wing-back’s dribble down the wing or at least jockey him away from an ideal crossing position. However, knowing that Frankowski can comfortably go inside, we can say that the defender is not in a good place to stop the Lens man from doing whatever he wants after making that move.

As play moves on into figure 6, we see that as Frankowski cuts inside, the opposition defender is completely caught off guard. As the defender stepped out to block the potential dribble down the wing, Frankowski took the ball inside which forced the opposition right-back to make a complete 180, as the image depicts. This leaves the defender in a poor defensive position, even having to completely turn his back on Frankowski for a moment, which gives the Lens man far too much time and space to plan his next move before having to worry about the defender’s challenge.

Frankowski’s intelligent movement inside, along with the defender’s poor movement, essentially kills the defender’s chances of stopping the wing-back’s cross and as play moves on into figure 7, we see that the resulting cross successfully meets a centre-forward’s head towards the back post. This doesn’t result in a goal but does result in a shot on target and a very dangerous chance created for Sang et Or by their right-footed left wing-back.

So, it’s clear from this example how the Poland international’s unique nature as a right-footed left wing-back can create big problems for the opposition. This has made Frankowski a useful tool inside the final third for Haise’s side this season. This unpredictability, combined with the wing-back’s crossing quality, has made him an excellent chance creator, resulting in the impressive attacking numbers that we analysed at the start of this section of analysis.

Figure 8 provides an example of an occasion when Frankowski opted to take the ball on the outside like a traditional wing-back. The right-footed left wing-back needs to avoid becoming predictable and he achieves this by acting like an orthodox wing-back at times. Here, after receiving the ball wide and taking a few steps inside, we see that Frankowski ended up in a 1v1 situation versus an opposition defender. This time, unlike in figure 5, the defender is positioned much better to protect the centre and guard against the wing-back cutting inside. This makes it possible for Frankowski to move back out wide and attack that space, however.

That’s exactly what happens as play moves on into figure 9, where we see that Frankowski has ended up in a very advanced position, but far wider than where we saw him in the previous image, as well as in the previous passage of play where he cut inside. From here, he can opt to play a cross on his weaker left foot or pull it back onto his stronger right foot, just like in figure 4, and again, he opts to pull the ball back onto his stronger right foot very quickly before crossing.

The cross at the end of this move was a disappointing one, as it was ultimately blocked by the opposition’s right-back. This highlights a big negative to Frankowski’s game — the fact that despite his clear efforts, he can still be predictable at times because he does, like any person and footballer, have some bias; in this case, that’s a bias towards using his right foot. Again, he has used his left foot at times and it’s not incredibly weak, but it’s weaker than his right foot which is a really dangerous weapon for Lens inside the final third so it’s understandable why the wing-back tries to force crosses through this foot whenever possible, even if it makes him more predictable. However, with opposition teams becoming more and more aware of Frankowski’s tendency to do this, he’ll need to get more and more creative with his dribbling to create openings for chance creation that won’t be blocked, like what happened in figure 9.

While this section of analysis focuses heavily on new man Frankowski and the additional weapons he adds to Haise’s arsenal inside the final third, it’s worth mentioning that Clauss is still Lens’ primary crosser and arguably the bigger creative threat, even despite Frankowski’s uniqueness. Clauss operates like a traditional wing-back, occasionally carrying the ball high before crossing, and often crossing early from a deeper position. His crossing technique is excellent which is why Lens send the ball to him so much and are happy to trust him with making so many crosses. Given that he ended last season as Sang et Or’s top assist provider and is currently their joint-top assist provider again this term right now, it’s safe to say that the right wing-back is rewarding his team’s trust with his output.

Counter-attacks

Lens are not a heavily possession-based side. They’ve kept an average of 48.3% possession this season, which ranks them 12th in Ligue 1. While they spend most of their time without the ball, however, they’re a very well structured and effective team in defensive phases who’ve managed to generate the joint-lowest xGA (7.33) of any team in France’s top-flight this term. They have conceded 10 goals, which is far more than expected, but still, only five teams have conceded more than them this season.

Based on what we’ve seen so far at Lens, I feel it’s fair to say that Haidara offers more than Frankowski does without the ball. Last season, Haidara engaged in 8.07 defensive duels per 90 with a very healthy 62.38% success rate, while this season, Frankowski has also engaged in plenty of defensive duels (7.63 per 90), as is the nature of the wing-back role in most systems, but he’s got a much worse success rate of just 47.27%. That success rate pales in comparison to Clauss at right wing-back as well as Haidara, with Clauss engaging in fewer defensive duels (5.23 per 90) but faring far better, generating a 61.36% defensive duel success rate this term.

While Frankowski offers a lot on the ball, Lens would benefit a lot from him improving his defensive output because, as mentioned above, the wing-backs generally have to engage in lots of defensive duels and Lens rely a lot on their counter-attacking quality to score goals. If Frankowski won more of his defensive duels, then Lens could create more counter-attacking opportunities.

Figure 10 shows an example of how Lens shape up when defending in the high-block phase in their 3-4-1-2 system. Last season, Sang et Or had the fifth-lowest PPDA (11.81) of any Ligue 1 side, which essentially means they had the fifth-most aggressive press of any Ligue 1 side. This season, Lens’ press has become a tiny bit more passive and they’ve got the 10th-lowest PPDA (12.15) in France’s top-flight, however that change is minimal and they still press with a relatively similar level of intensity, which, when successful, helps them to force turnovers in advanced areas of the pitch, which in turn creates dangerous counter-attacking opportunities close to the opposition’s goal.

Lens’ defensive shape in the high block phase as depicted in figure 10 provides an excellent example of how Haise wants his side to orientate themselves when pressing at the very beginning of an opposition attack. The two strikers retain access to the opposition’s centre-backs. Their primary focus is getting near to them. If they’re on the ball, the striker will scan to ensure he’s closing off any passing lanes that the defender can use while staying close to them to stifle any attempt at individual ball progression, and if they’re not on the ball, then the striker will look to position themselves so that they pose a pressing threat to that player if a pass is played to them.

The ‘10’ will sit on the deepest opposition midfielder and mark them very closely to prevent the opposition from playing through this player by either preventing the player from turning if the ball is played to them or by putting the opposition off even making that pass via their pressing threat. The deeper central midfielders mark zonally but will get tight to a player if they enter their zone. However, they won’t stray too far from their zone and will mark space if no player enters the vicinity. We see an example of this with the two deeper Lens midfielders in figure 10. One midfielder is slightly higher to mark the opposition midfielder who’s entered their zone, but the other is sticking to his base position, ideally remaining mindful of movement around him by scanning and closing off passing lanes if possible, but not leaving his zone. As a result, this player is marking no particular opposition player at this moment.

As for the wing-backs, we see that they’re starting much deeper. However, they are responsible for quickly closing down the opposition’s full-backs if they receive the ball here in the build-up, which means they have to be alert and quick to react to the opposition’s passes. They don’t start higher because they’re essentially responsible for the entire wing and don’t want to let too much space open up in deeper areas which the opposition could exploit via a quick long ball or some intelligent movement out onto the wing. This means that as well as efficiency in defensive duels, alertness, reactions, and pace, the mental skills of anticipation, patience, and intelligent decision-making are key for the wing-backs to perform their important defensive role in the high block phase well.

As play moves on into figure 11, we see that the opposition played the ball from the right centre-back to the left centre-back. This triggers more aggressive pressure from the Lens forward who was retaining access to this player, which also leads to the other forward stepping up to get closer to the other centre-back and the goalkeeper. The ball-near wing-back also begins to advance at this point, knowing that the opposition could now try to use this full-back to play out.

As Lens’ wing-back steps up, an opposition attacker attempts to target the space behind him by dropping deep and wide, which pulls Lens’ wide centre-back out of position. However, the centre-back is covered by the central midfielder who we mentioned was free in the previous section. This is an important part of Lens’ pressing system. If the wing-back is forced to press high, then the wide centre-back is more likely to get dragged out of position too. It’s important for another player, in this case, the near central midfielder, to step back to prevent Lens’ backline from getting exposed. The backline could alternatively step across in this situation, allowing the ball-far midfielder or wing-back to join them and provide cover if the near central midfielder is occupied. However, the situation we see in figure 11 is arguably the simplest one to pull off effectively.

It’s worth noting that as the opposition play to the far side, the ball-far wing-back steps more into the centre. We touched on this earlier on in this scout report but to reiterate, as the ball is played to a particular side of the pitch, Lens players near to the ball will get drawn out of position which can lead to the centre becoming exposed. To avoid this, the ball-far wing-back will move into the centre to provide extra protection in the centre, freeing up the opposition players on the ball-far wing, but being willing to take that risk to prioritise protecting the space around the ball.

As the ball moves further and further up the pitch and into wider areas, Lens’ press increases in intensity and as a result, the wing-backs generally need to be prepared to engage in lots of defensive duels, along with the wide centre-backs and deep central midfielders. This can lead to these players starting counter-attacks a lot if they’re successful in their defensive duels, which increases the importance of their quality in defensive 1v1s. This passage of play highlights how Haise sets his team up to try and force these turnovers and create moments of transition and given that Lens thrive in transition, this element of their tactics shouldn’t be undervalued — it’s key.

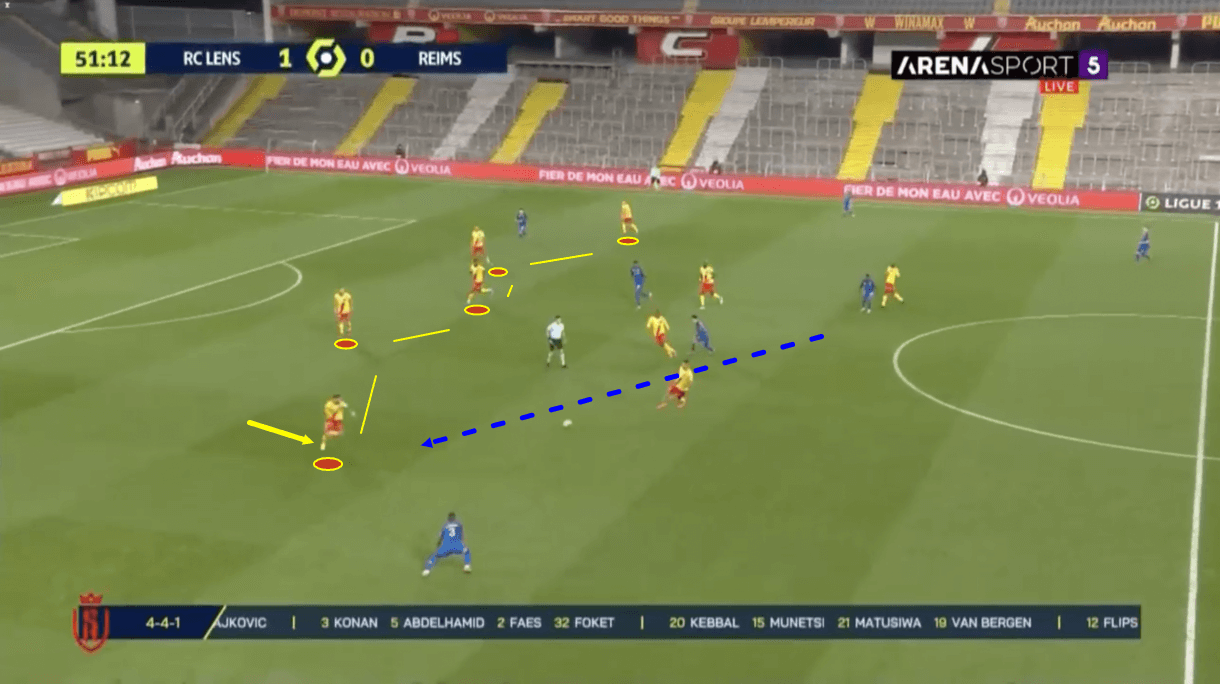

As Lens drop deeper into a mid-block and low-block, their wing-backs naturally get deeper and closer to the centre-backs. Additionally, one centre-forward typically drops deep with the rest of the team, while another will stay high to offer Lens an out-ball if possession is recovered — an important role within the counter-attacking system. We see an example of Lens defending in a low-block in figure 12. The three centre-backs, midfielders, and centre-forward must continue to congest the centre of the pitch to give the opposition little space to play through them. If they succeed in doing this, then they’ll either force a mistake from an opposition player who was too keen on forcing play through the centre or they’ll force play out wide, which gives the wing-backs a chance to spring into action. We see an example of the latter in figure 12.

Here, the opposition tried to play the ball through to a winger but thanks to Lens’ compact shape and organised press, the pass was not incredibly accurate. In this area of the pitch, where Lens have got a very organised, compact shape that covers a lot of area, misplaced passes don’t often go unpunished and as play moves on from here, we see right wing-back Clauss pounce on the ball as soon as it gets close to him to make the interception. After regaining possession, the wing-back’s mindset immediately turns to ‘attack’ and he starts to drive his team upfield. This is a key part of both wing-backs’ roles within Haise’s system. Again, they’ve got to be alert, quick to react, pacey, patient, and intelligent with their decision-making without the ball to capitalise on the counter-attacking opportunities on which Sang et Or typically thrive.

As play moves on into figure 13, we see that Clauss quickly found an attacking teammate — the right centre-forward who dropped deep to help defend — with a through ball and sent him into the opposition half. As this player received and assessed his options, Clauss sprinted forward to make himself a progressive option for the ball carrier and provide some width for his side in the final third. Given that this is a moment of transition and the opposition had just been attacking with their full-backs sent forward, there was lots of space out wide in the opposition’s defence for Clauss to attack which we can see him targeting with this threatening run.

It’s often the case that the wing-backs have lots of space to attack in transition, so the awareness and determination on display from the right wing-back here to get himself in position to exploit that space are two key traits for the wing-backs to possess.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis and scout report, Haise asks a lot of his wing-backs within this 3-4-1-2 system; more than most, they need to be well-rounded players technically, physically, and mentally and we’ve highlighted some of the key attributes for the wing-backs to possess throughout this scout report.

It’s clear that Haise recruits players for the wing-back positions with ‘attack first’ in mind, hence why former wingers in Clauss and Frankowski perform those roles at Stade Bollaert-Delelis, and that’s because these players create a lot of Lens’ goalscoring opportunities which is why Clauss and Frankowski are Sang et Or’s joint-top assist providers this term.

Comments