This past weekend, Gérald Baticle claimed the biggest scalp yet of his young tenure in charge of Angers as he guided Le SCO to an emphatic 3-0 victory over Olympique Lyon. Baticle arrived at Stade Raymond Kopa this summer, having spent the previous 10 years at Lyon, serving as Les Gones’ assistant manager for a decade before his summer departure and Sunday’s face-off with his now-former club.

Following his side’s victory, Baticle declared that their performance was “what [they] had set up” and prepared in training ahead of the fixture, stating that he was “not surprised” by “the intentions” and “animations” his team produced to dismantle Lyon, who finished 32 points and nine places above Le SCO in France’s top-flight last season.

Sunday’s 3-0 victory leaves Angers top of Ligue 1 after game week two. They’ve accumulated six points from a possible six and an impressive goal difference of five, scoring five thus far and conceding nothing. While it’s early days, it’s clear that Baticle has got off to a flying start at his new home, with the Angers squad taking to his ideas quickly.

Peter Bosz, on the other hand, who moved to Lyon in May after being dismissed by German Bundesliga side Bayer Leverkusen earlier this year, still awaits his first competitive win at Lyon, who have undoubtedly been weakened this summer, losing Melvin Bard and Jean Lucas to Ligue 1 rivals Nice and Monaco, respectively, and perhaps most significantly, Memphis Depay who joined La Liga giants Barcelona.

In this tactical analysis piece, we’ll provide analysis of one key aspect, in particular, to Baticle’s tactics on Sunday which led his Angers side to victory over Lyon – their dominance in the transition phases. We’ll look at how Angers’ control over transitions played arguably the most important part of all in their dismantling of Les Gones.

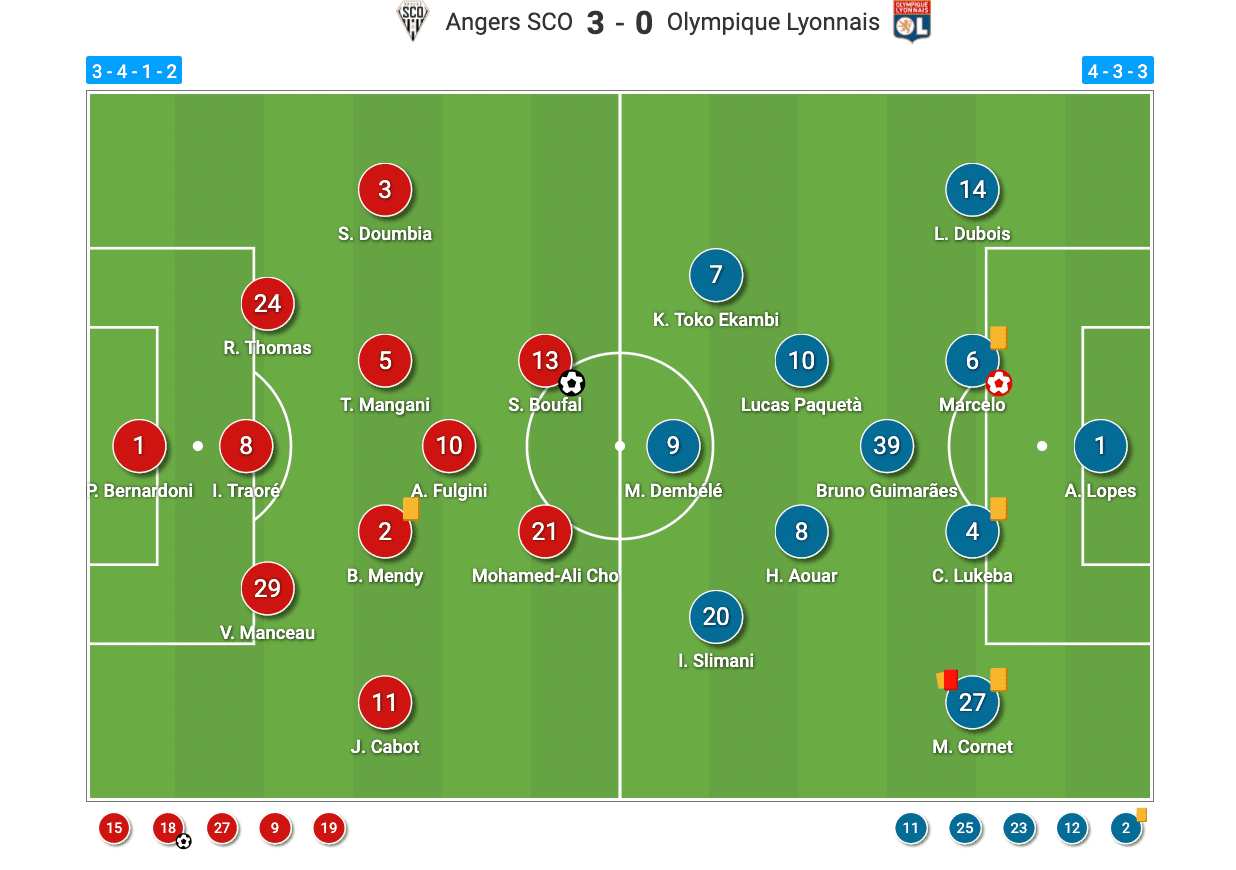

Lineups and formations

To kick off this analysis piece, we’ll quickly look at the personnel who took to the field for both sides in Sunday’s fixture. Starting with the eventual winners, Angers, the home side lined up in a base 3-4-1-2 shape for this game. Their starting XI looked like:

Paul Bernardoni (GK), Vincent Manceau (RCB), Ismaël Traoré (CB), Romain Thomas (LCB), Jimmy Cabot (RWB), Souleyman Doumbia (LWB), Batista Mendy (RCM), Thomas Mangani (LCM), Sofiane Boufal (AM), Angelo Fulgini (RCF), Mohamed-Ali Cho (LCF).

Angers also made five substitutions during this game, the first couple of which came on the 74th minute when Stéphane Bahoken replaced Cho and Azzedine Ounahi replaced Boufal. Then, in the 80th minute, Casimir Ninga came on for Fulgini in attack, while Pierrick Capelle took Mangani’s place in midfield. Lastly, in the 86th minute, Mathias Pereira Lage replaced Doumbia for Le SCO’s final substitution of the game.

As for the away side, Lyon lined up in a base 4-3-3 shape for this game. Their starting XI was: Anthony Lopes (GK), Léo Dubois (RB), Marcelo (RCB), Castello Lukeba (LCB), Maxwel Cornet (LB), Bruno Guimarães (DM), Lucas Paquetá (RCM), Houssem Aouar (LCM), Karl Toko Ekambi (RW), Moussa Dembélé (CF), Islam Slimani (LW).

Additionally, just like Baticle, Lyon boss Bosz made five substitutions in this game, three of which came at half-time with Lyon trailing Angers by a goal. Thiago Mendes replaced Guimarães, Sinaly Diomandé replaced Lukeba, and Maxence Caqueret replaced Paquetá for the second 45 minutes. Then, in the 69th minute, after Cornet was sent off just a few minutes prior, left-back Henrique came on in place of Slimani, while lastly, in the 82nd minute, Tino Kadewere took to the pitch in place of Toko Ekambi.

Angers’ defensive transitions

Angers set up to control transitions, first and foremost, in this game. This was particularly evident through their transitions from defence to attack, which led to their goals. However, they also performed very well in transition to defence, denying Lyon opportunities to hurt them on the counter.

While Angers came out of this game with a 3-0 victory, Lyon had the majority of the ball in this contest – 58% possession to Angers’ 42%. Part of this can be attributed to both teams’ respective styles in possession. Angers generally played the ball forward faster, while Lyon operated with a slower tempo – too slow at times. However, Angers’ ability to halt Lyon’s counter-attacks and force them to continue passing the ball around in search of an opening instead of driving forward into an opening on several occasions also played a small but important part in this.

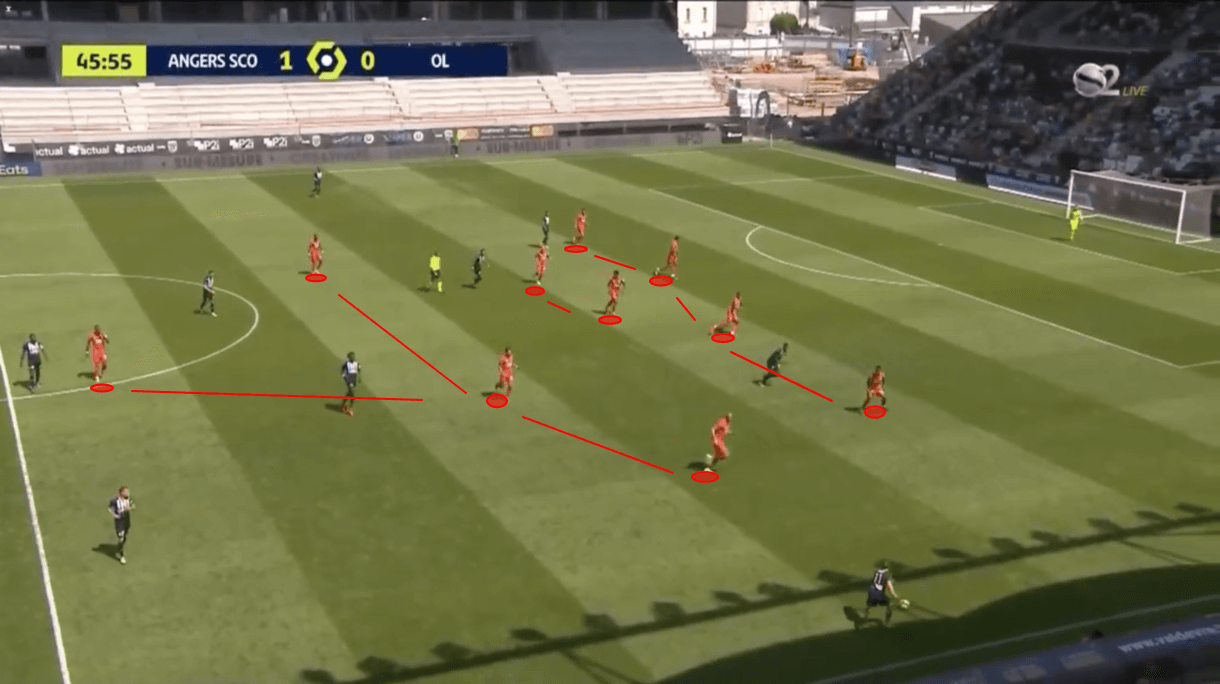

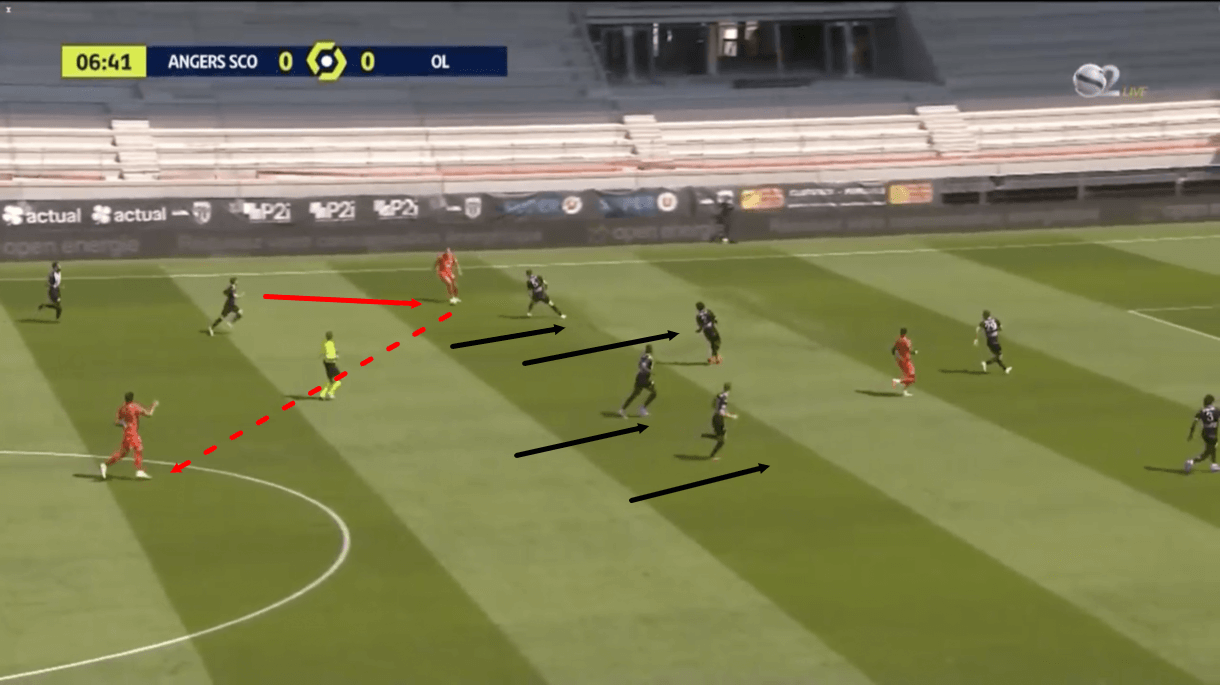

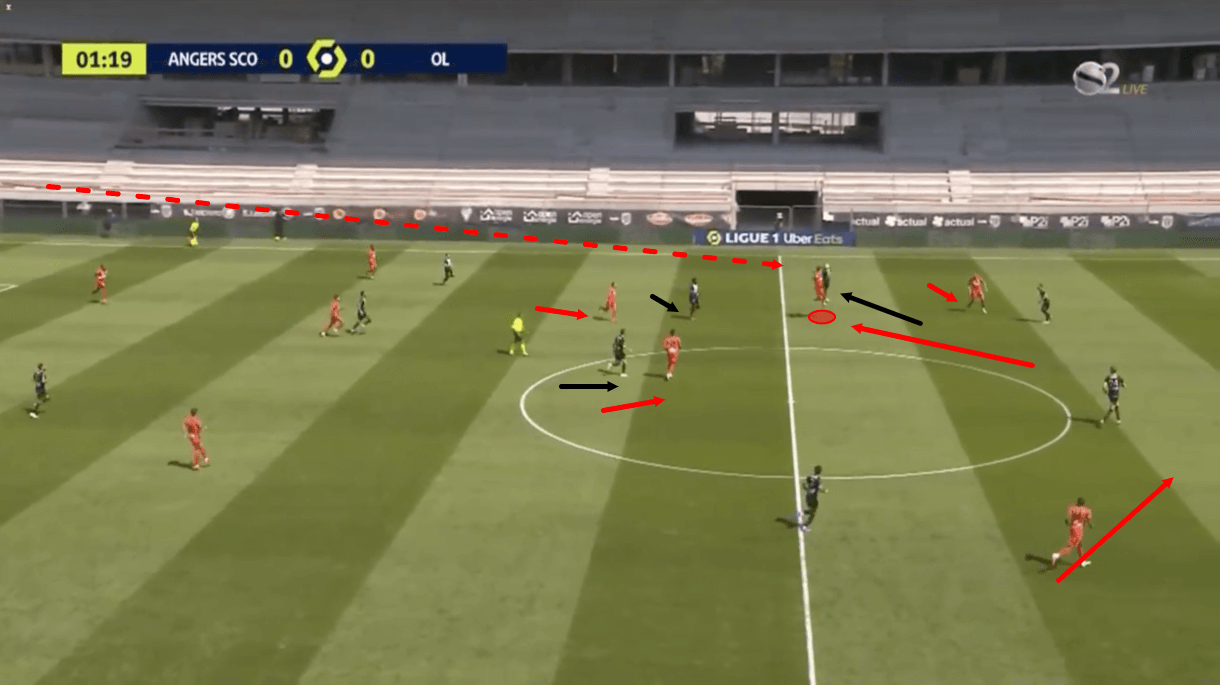

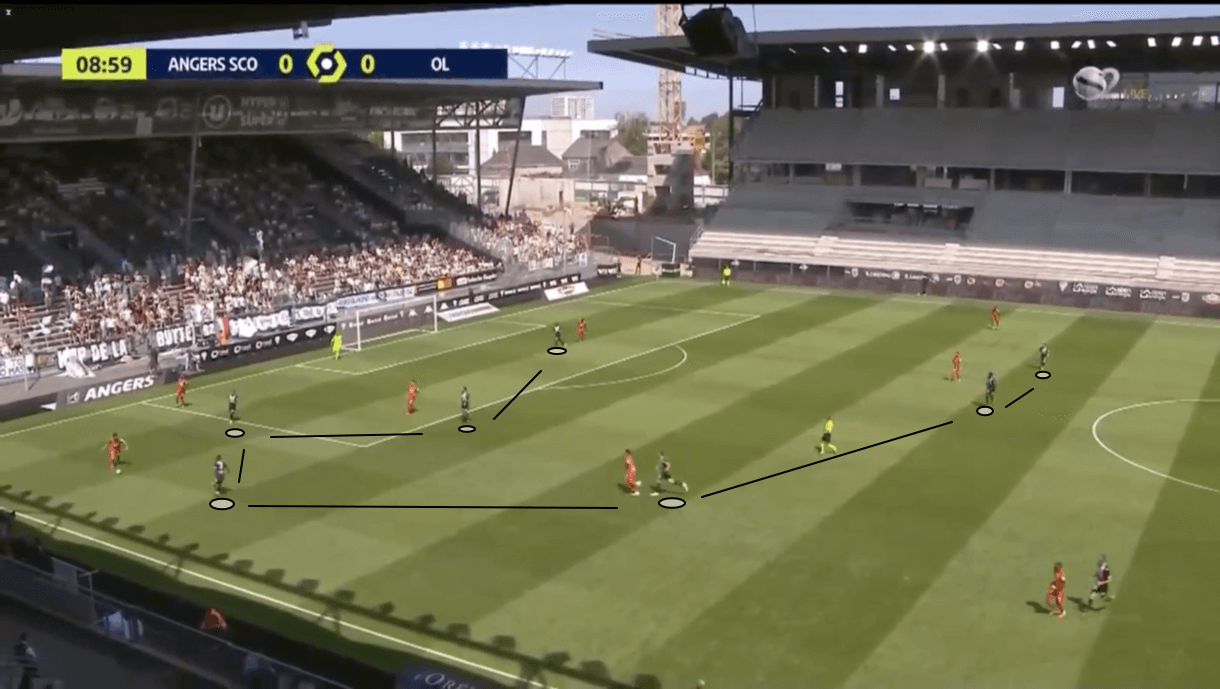

In figure 2, we see an example of Angers building an attack in their offensive 3-4-1-2 structure. As we’ll discuss at greater length later in this tactical analysis piece, Baticle liked his team to form a front-five consisting of the three attackers and the two wing-backs. This is evident from figure 2. The creation of this front five in attack left a 3-2 structure at the base of Angers’ shape – the three centre-backs and two central midfielders. These players generally remained deep during positional attacks and provided security for the five-man frontline, guarding against counter-attacks.

This 3-2 structure played an important role in bracing Angers for the transition to defence and Lyon’s potential incoming counters. Angers always remained very strong, defensively, in the centre of the pitch throughout this game thanks largely to the constant presence of these two central midfielders who were extremely active ball-winners – especially Mendy. So the fact they remained here during positional attacks to protect against potential counters provided good coverage for Angers in transition to defence.

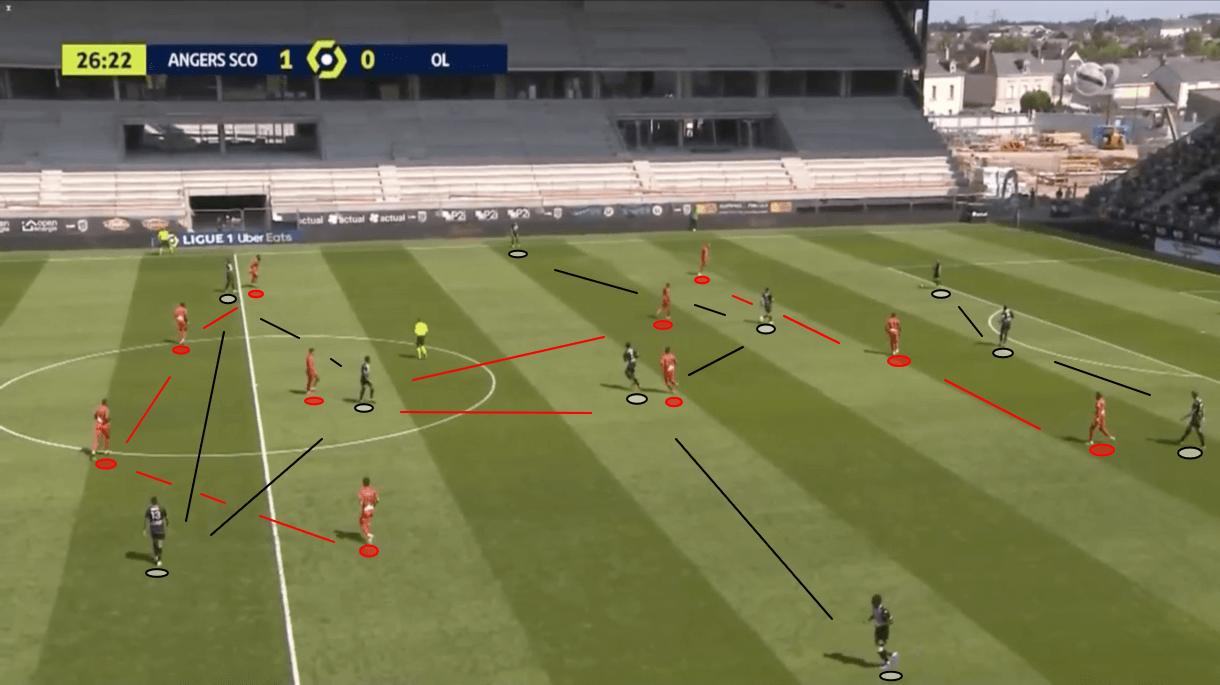

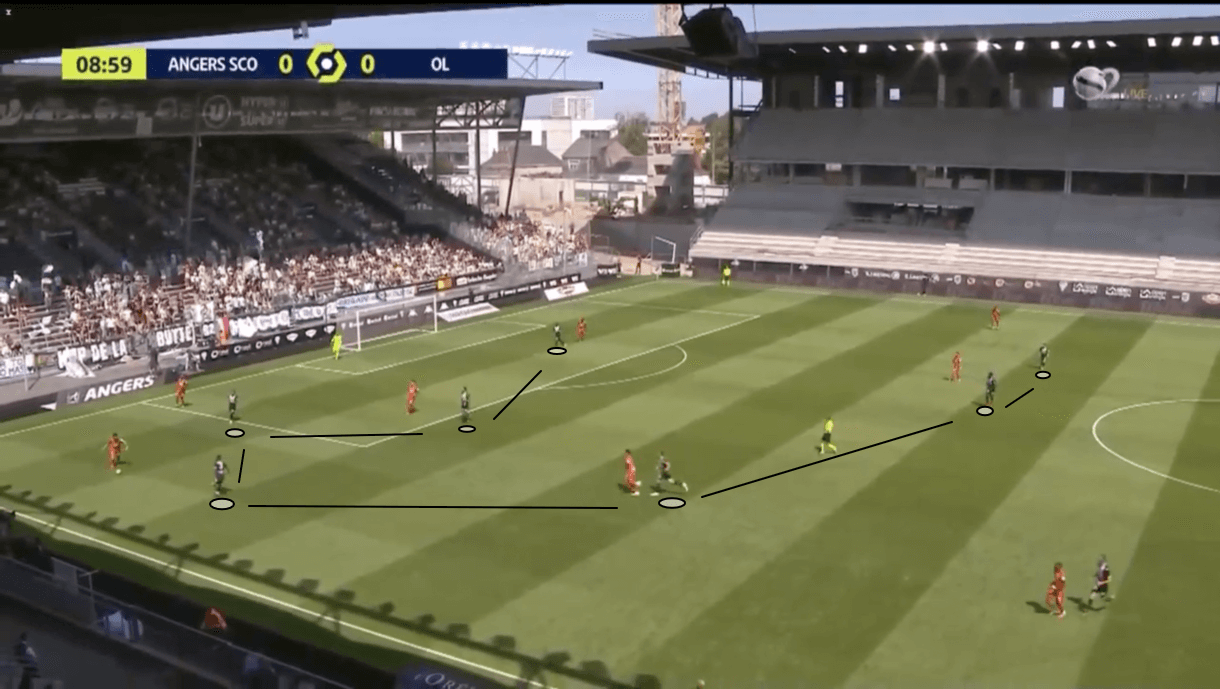

Figure 3 shows another example of Angers’ offensive structure – this time in a slightly earlier phase of play than we observed in figure 2. Here, Angers are in the build-up phase but we see a very similar structure to the one we saw in figure 2, but with the wing-backs sitting slightly deeper and the central midfielders staggering too. This highlights how the shape changes to provide more support for the centre-backs on the ball during the build-up. The wing-backs provide an outlet for shorter passes via their positioning and the central midfielders make it somewhat easier for their side to play through them by staggering as so.

This shape also allowed Angers to place more bodies deeper during the build-up, while Lyon were pressing in a high-block. This provided a little bit of security in case a turnover occurred in this dangerous area for Le SCO. With more bodies positioned close together in this deeper area, Angers could get bodies behind the ball and in position to defend in a low-block quicker than if they’d committed more men forward and they had more ground to cover in retreat.

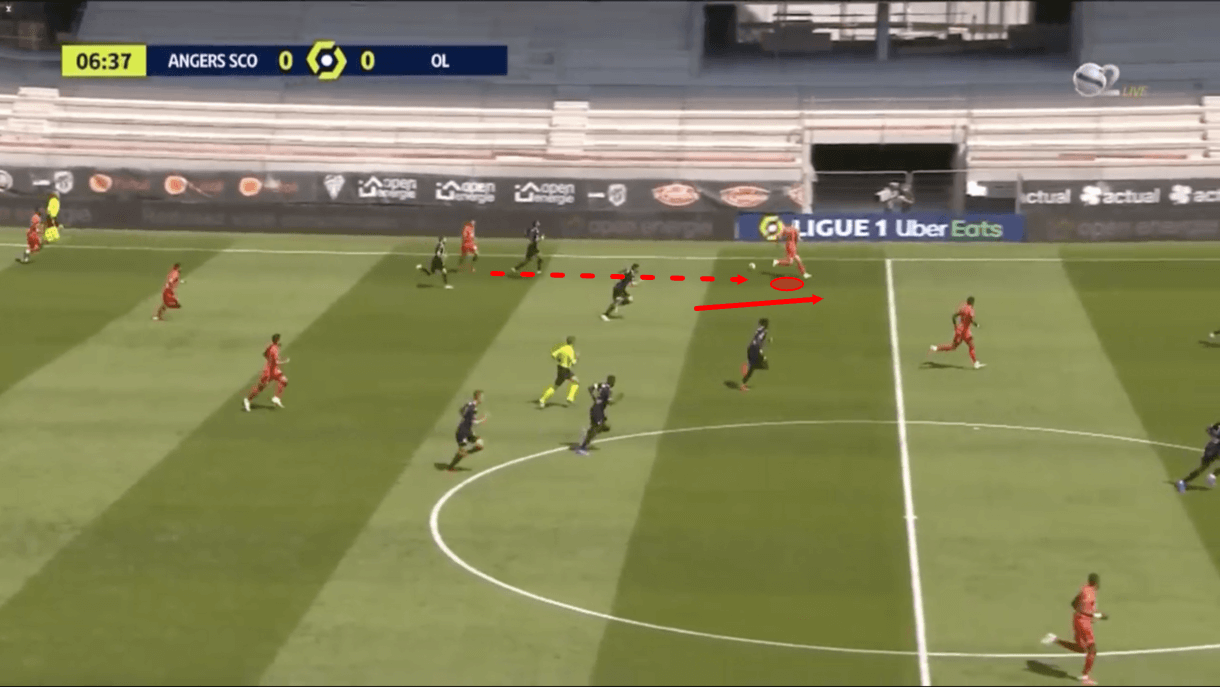

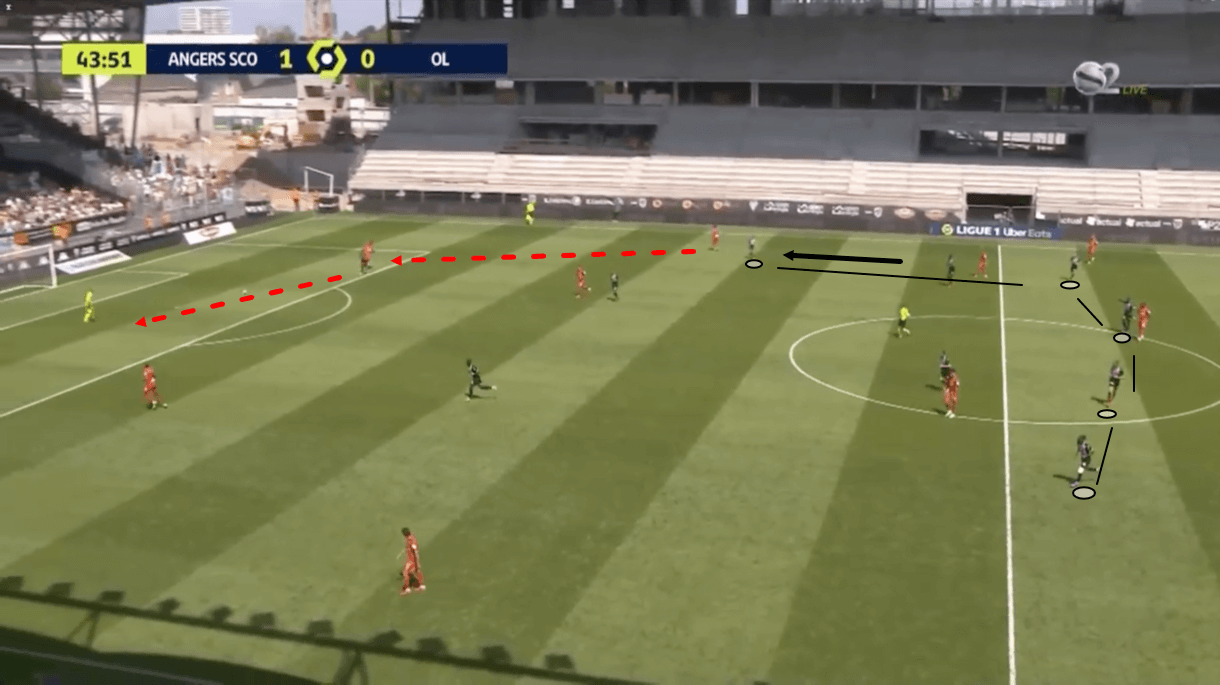

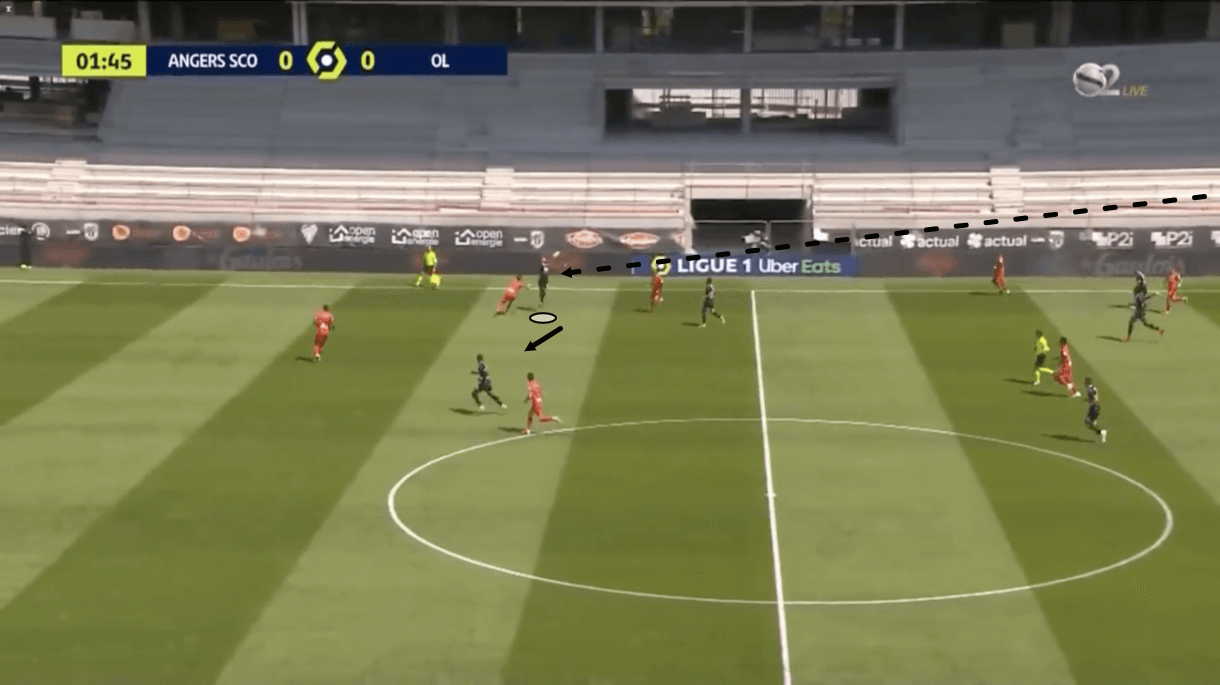

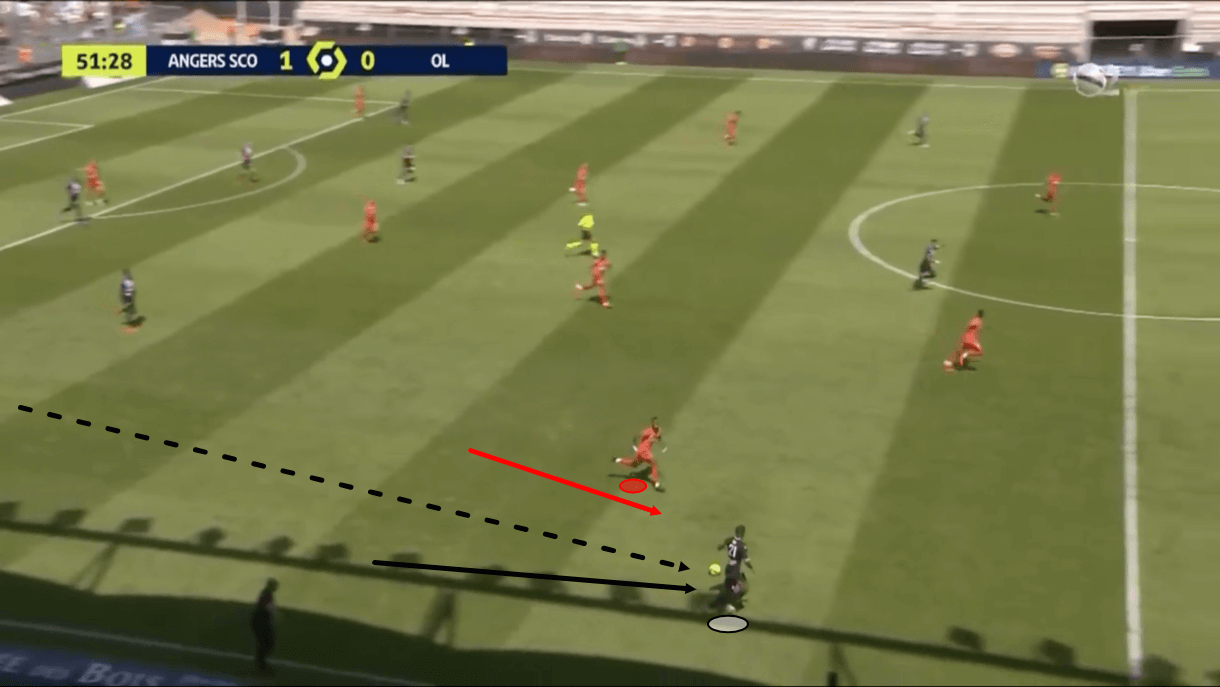

A lot of Lyon’s transition attempts came through Slimani on the left wing. This was partly by design from Lyon – they played Slimani at left-wing and so he was often more open than others in transition while Angers focused on protecting the centre more heavily – but also partly by design from Angers, who would noticeably mark Toko Ekambi and Dembélé more heavily – if given the choice – in transition, leaving Slimani more open and ultimately forcing Lyon to play through him. We see an example of Lyon attempting to counter-attack through Slimani in figure 4.

Lyon performed poorly in transitions to attack on Sunday and this passage of play highlights a couple of reasons for that. Firstly, the pass to Slimani here is not very fast-paced. This forced the attacker to slow his run to meet the ball, taking some momentum out of the counter for Lyon. In general, Lyon did play with quite a low tempo versus Angers and as a result, it was common to see them play slower passes like this one. However, this proved harmful to themselves in transition to attack as it slowed their transition down and afforded Angers more time to recover.

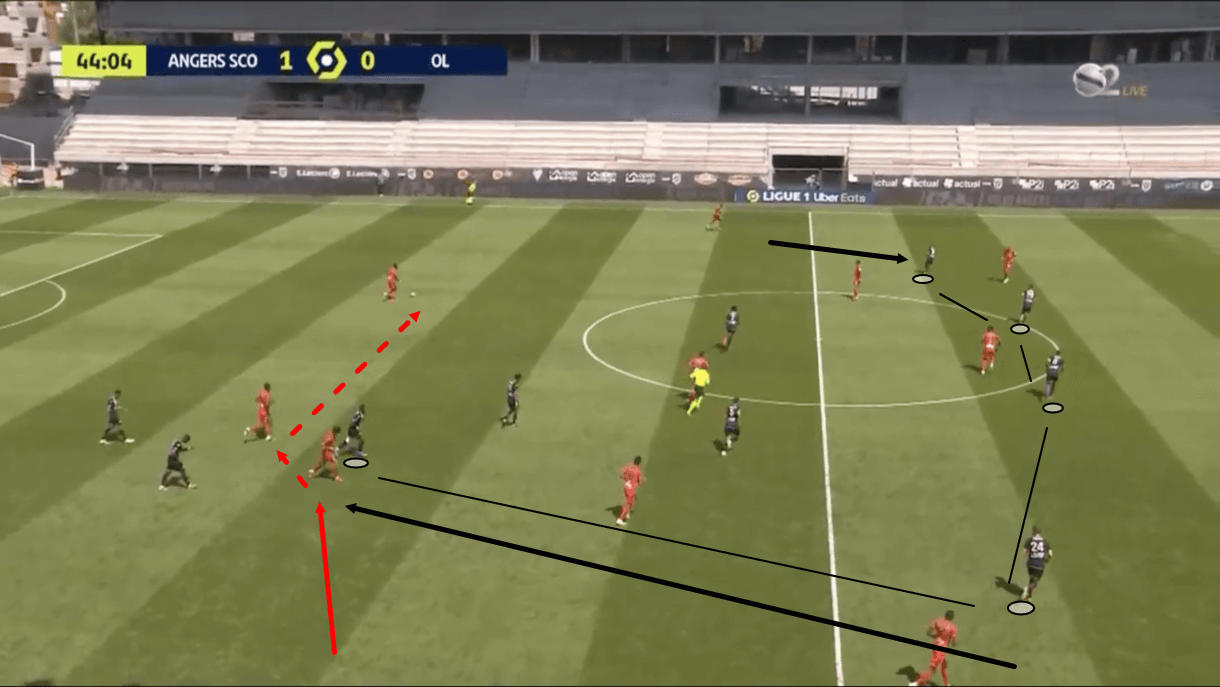

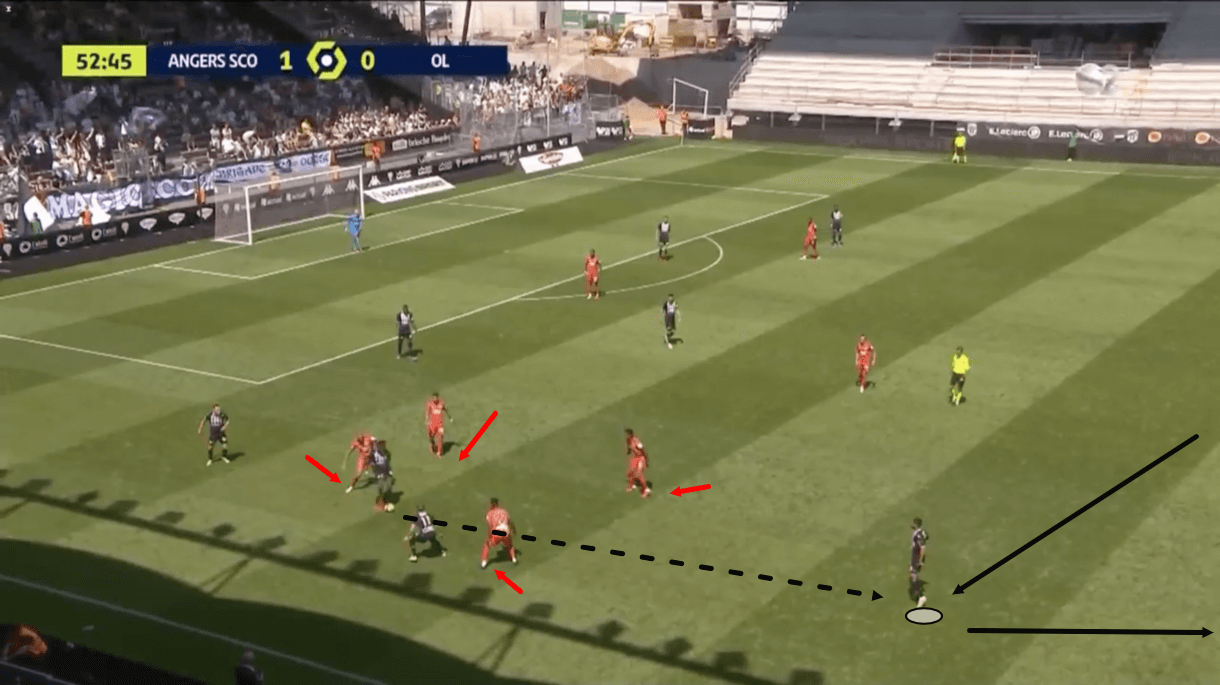

In figure 4, we saw that Angers had just two men in the centre-back positions at this moment in which Lyon attempted to counter – so Slimani and the two attackers just ahead of him – Toko Ekambi and Dembélé – theoretically had the opportunity to create an overload. However, in figure 5, we see that Angers had well enough time to get bodies back behind the ball and force Lyon to change course, ultimately playing back into central midfield and beginning a slower, more positional attack with Angers given the opportunity to get settled and organised in their 5-3-2 low-block.

Another reason for Lyon’s struggle in transition which is evident from this example is the fact that Slimani isn’t the quickest or most agile player and isn’t the one you’d ideally want to be playing through in this phase. However, due to his position in Lyon’s setup and Angers’ decisions to cover the other attackers more heavily during this phase, they often had to. Due to the attacker’s lack of pace, Angers often had more time than Lyon likely would have hoped to recover.

This, combined with the fact that Baticle’s side generally dropped back into their defensive shape quite quickly in transition to defence – with player’s often visibly sprinting to form their side’s defensive shape – meant that Angers effectively dominated this phase. They did a very good job in transition to defence, recovering well throughout the game and proving difficult for Lyon to counter-attack successfully.

Angers’ press

Baticle’s side pressed very aggressively throughout this game in different areas of the pitch. We’ll analyse those situations in this section to highlight how Angers’ press played a key role in their victory over Lyon, with Le SCO’s opening goal coming via a transition resulting from a high recovery thanks to their aggressive pressure.

Figure 6 shows an example of Angers’ 3-4-1-2 shape in the high-block phase. Angers pressed zonally but they went with quite a man-oriented approach when in the high-block – particularly in the centre, where Angers’ central midfielders and ‘10’ generally marked Lyon’s central midfielders and holding midfielder very tightly. At times, Angers got too man-oriented in the centre, allowing their players to get dragged out of position and creating space for Dembélé to drop into and Lyon to slice through them. However, in general, Angers’ aggressive press was effective at stifling Lyon’s build-up play.

In figure 6, we see Lyon’s right-back, Dubois, on the ball. With the ball on this wing, Angers’ defensive shape moves over to this side as seen above. This doesn’t impact the strikers and midfielders too much but impacts the wide men quite a bit. With Dubois on the ball, Angers’ left wing-back has to advance into quite a high defensive position. The left centre-back would shift over towards the left-back position to provide cover as a result.

Meanwhile, the right wing-back would come more centrally, essentially forgetting the left-back and focusing on being an extra man in midfield. This was key to Angers’ high-block and avoiding getting played through as a result of their man-oriented midfielders. The opposite wing-back effectively became a free man in midfield to cover space and ensure that Lyon couldn’t manipulate Angers’ defensive shape regularly.

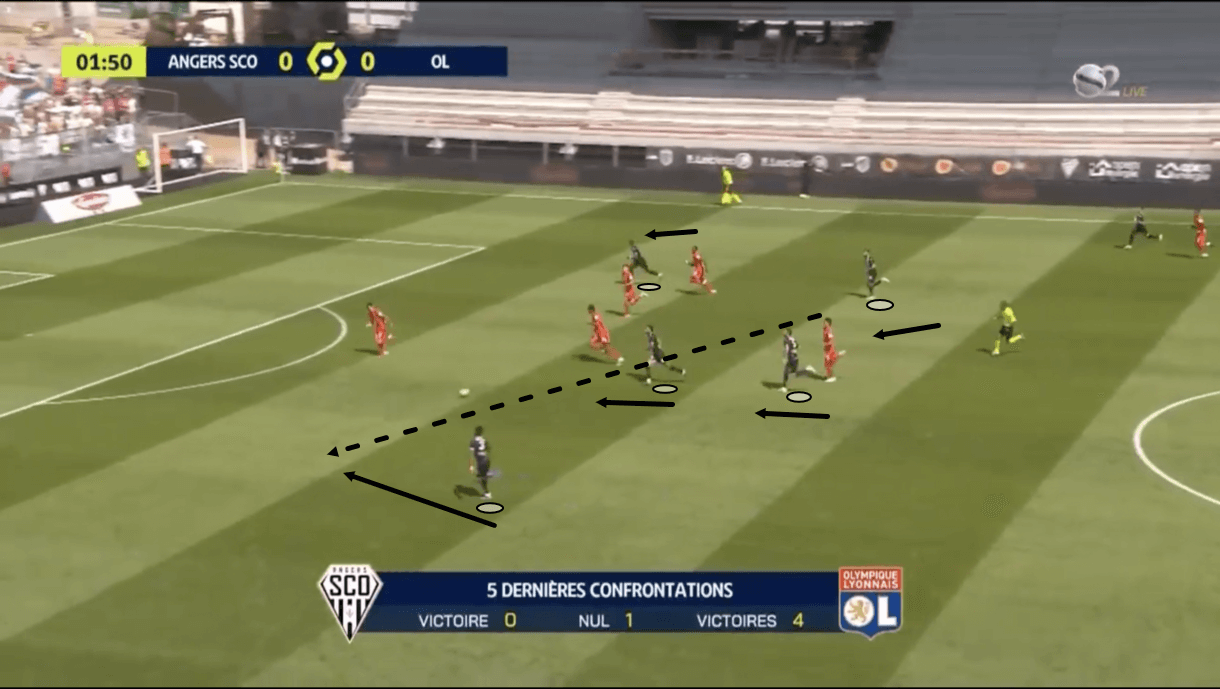

Figure 7 shows another example of Angers’ defensive shape during the high-block phase. Here, we see the right wing-back pressing high, while the left wing-back has remained deep, providing cover and not worrying about Les Gones’ right-back. Just before this image, Lyon attempted to play out through the left-back but as Le SCO’s right wing-back drove forward, the away side were forced to go back to the goalkeeper.

As play moved on into figure 8, Lyon ended up playing the ball out to the right-back who was freer, but then attracted pressure from the left wing-back. As the left wing-back advanced to mark Lyon’s right-back, the right wing-back forgot about Lyon’s left-back and recovered to protect space and provide extra support to midfield again, as we observed in figure 6. It was common to see Angers’ backline operate with this pendulum motion which was key to protecting the centre during the high-block phase.

This highlights one way in which Baticle’s side went about implementing one key element of their manager’s tactics in this game – buff up the centre and prevent the opposition from playing through this area. On most occasions when Lyon did try to play through the centre they were met with fierce pressure from Angers’ ball-winning central midfielders, the ‘10’, and the free wing-back – if not even more bodies. This helped them to force Lyon out from the centre – into easier-to-press areas like the wings – or helped them to force turnovers through their aggressive central pressure.

It was fairly common to see Lyon play the ball long from the ‘keeper in this game – potentially in part due to their struggle to play through Angers’ defensive shape. They were happy to use Dembélé as a target man, dropping into midfield to open space for Toko Ekambi and Slimani to potentially attack or just to boost the numbers in midfield and try to progress by winning the ball there and advancing. We see an example of Dembélé dropping to contest an aerial duel from a goal kick in figure 9.

This Lyon tactic wasn’t extremely effective versus Angers. Le SCO’s centre-backs dealt really well with Dembélé’s movement, with one – usually the central centre-back – following the striker into midfield and contesting the aerial duel with him – often beating the Lyon attacker aerially. Additionally, the other two centre-backs were alert and reacted to that movement well, closing the central space and making it more difficult for Dembélé to send a flick-on through the backline to his attacking teammates.

Additionally, on the occasions where Dembélé did win the aerial duel, he often sent the ball into central midfield, where Paquetá and Aouar – later Caqueret and Aouar – would have to compete with Mendy and Mangani. As mentioned previously, the Angers midfielders were extremely active defensively throughout the game and always reacted faster and more aggressively to the second ball than Lyon’s midfielders did. Just like when playing into midfield from the back, this meant that it was difficult for Lyon to succeed at winning second balls in central midfield following an aerial duel from the goal kick.

So, there weren’t many ways for Lyon to succeed from these aerial duels. The defender contesting it with Dembélé often won them, it was difficult for Dembélé to flick the ball on accurately and even if he managed that, Angers’ other centre-backs prepared themselves to cover that space, and if the striker headed the ball down into midfield, Angers usually swept up and dealt with the danger.

When pressing high, sitting in a mid/low-block or contesting second balls, Angers’ midfielders were absolutely key to their side’s defensive tactics in this game. They forced turnovers all around the pitch and created lots of counter-attacking opportunities for their side, both from advanced positions and deep positions. Lyon found it difficult to get their creative players (Aouar, Paquetá, Guimarães) on the ball as a result and failed to create many chances.

Angers defending deep

When Angers defended high, they formed something of a 3-4-1-2 shape. However, when defending deeper, they generally played in more of a 5-3-2 shape. This shape offered great coverage centrally – further protecting this area and preventing Lyon from playing through them.

Figure 10 provides an example of Angers’ 5-3-2 defensive shape. Here, we see how the wing-backs tucked in and formed a tight, compact back five when defending deeper, with the two central midfielders and the ‘10’ providing additional cover in central midfield just in front of them and the two strikers pressing from the front. As figure 10 indicates, this defensive shape did allow Lyon some space out wide, but this space was generally closed down when the ball was played out to the wing and although Lyon managed to double-up on Angers’ wing-backs on occasion to play through the backline – those occasions weren’t common and this defensive shape generally offered more than enough cover.

One of the biggest frustrations for Lyon in the first half was their struggle to get deep-lying playmaker Guimarães on the ball, in space, facing forward. He always faced constant pressure in the centre – usually from Angers’ ‘10’ – and as a result, was limited in how he could conduct play from deep. At times, he drifted out into the deep half-spaces, where we see him in figure 10, just to find some space where he could get his head up on the ball and pick out some movement ahead of him.

On this occasion, Guimarães played a looping ball over Angers’ backline, intending to exploit space behind. It was very common to see Lyon utilise this tactic on Sunday. They were constantly trying to exploit space behind Angers’ backline with this type of long ball but generally, there wasn’t enough space behind the backline to really exploit and Angers dealt well with the pass attempts – which were limited as it was because of Angers’ aggressive pressing. Lyon’s struggle to utilise Guimarães effectively was a large part of why he was taken off at half-time. He didn’t offer great coverage in transition and Les Gones struggled to get the best out of him in possession too in this one.

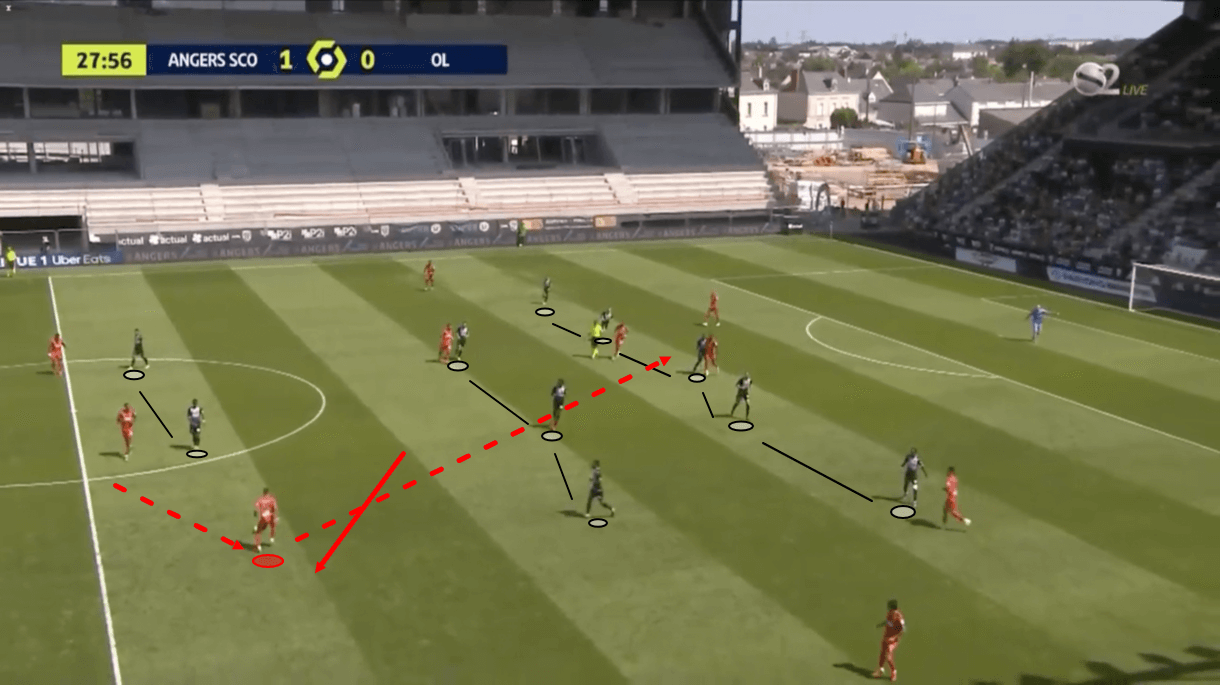

Figure 10 also gives us a glimpse at Lyon’s offensive shape. In possession, Lyon typically formed something of a 3-2-5 shape. The two centre-backs and holding midfielder sat slightly deeper, while the two central midfielders played just ahead in midfield. Meanwhile, Lyon’s front three became narrow, allowing the full-backs to push up and provide the width outside. Lyon were quick to get the full-backs forward in this game and this, combined with the fact that their midfield struggled to compete with Angers’ midfield physically in 50-50s, was a weakness in their structure in transitions which Angers successfully exploited.

We see an example of Angers attacking the vacated full-back position in figure 11. Just before this image, Lyon were in attack but as Angers regained possession, they immediately sent the ball long down the wing towards a striker who’d shifted out onto the wing. Due to the left-back’s absence, the centre-back was forced out wide but he was too slow to get in position and Angers’ striker could take the long ball down and dribble past.

As play moved on into figure 12, we see how Angers worked to quickly exploit Lyon’s weakened backline by sending large numbers forward quickly to create an overload. Additionally, we see how they intelligently switched play to the free man on the opposite side, with Les Gones’ backline having just been dragged over to one wing in transition. This passage of play highlights how Angers identified and attacked weaknesses in Lyon’s shape in transition. This was a common sight in Sunday’s game, with Angers constantly taking advantage of this particular weakness in transition.

We see another example of Angers sending the ball directly down the right wing to exploit Lyon’s vacated left-back position in figure 13. Angers created many chances via this method on Sunday and left-back Cornet’s red card in the 65th minute came directly as a result of Angers sending the ball down this wing on the counter while he was upfield, and the defender desperately trying to recover. He likely also became frustrated due to his offensive positioning being constantly exploited throughout this game – leading to his sending off.

As Lyon pressed more and more aggressively in the second half in search of high recoveries to try and get themselves back in the game, Angers’ ‘10’ Boufal, and later Ounahi who scored Le SCO’s third and final goal of the game, ended up finding more and more space between the lines. We see an example of this in figure 14, where we see Boufal in lots of space on the right wing, having just shifted out into this position from his base central position. The ‘10’s movement proved very difficult for Lyon to deal with when pressing high and Angers exploited this very effectively on a couple of occasions as well, playing out of Les Gones’ press and breaking away upfield through the ‘10’.

From these counter-attack examples, we see how important the front three were for Angers in transition on Sunday. They were constantly on the lookout for space that they could exploit in Lyon’s weakened structure and they were constantly moving into this space to give their deeper teammates options in transition. The fact that the advanced attackers and deeper players were on the same wavelength and constantly combined quickly in moments of transition meant that they were a step ahead of Lyon and enjoyed that advantage of exploiting them time and time again in transition in this game. The fact that they were ultimately so successful with these tactics is a testament to the coaching quality of Angers boss and former Lyon assistant Baticle, who worked with a Lyon side renowned for their counter-attacking quality last season and looks to be doing so again this term.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis piece, it’s clear that Angers did well at making Lyon’s possession dominance ineffective through their impressive defending. This is why Lyon had 29 positional attacks on Sunday, with just six resulting in a shot. Almost 10% more of Angers’ positional attacks resulted in a shot, for reference, per Wyscout, highlighting Lyon’s struggle to convert their possession into goalscoring chances.

Angers had less of the ball but ended the game with more shots than Lyon, twice as many shots on target as Lyon and most importantly, three more goals than Lyon. As we’ve analysed, this was largely thanks to their superior performance in transition. They nullified Lyon’s attempts to counter-attack them very successfully by exploiting Slimani’s lack of pace and by retreating into their defensive shape very quickly and effectively, while they pressed aggressively to force high turnovers, win the ball centrally, and constantly win second balls, creating counter-attacking opportunities from dangerous positions. Lastly, Angers did very well to exploit weaknesses in Lyon’s structure in transition to attack – especially their weakness at the full-back positions, with Lyon committing the full-backs very far forward in possession. All of this led Baticle’s side to victory over Les Gones.

Comments