In August last year, Andreas Georgson‘s set-piece ideas were analyzed after his impact on Southampton’s dead balls had an immediate and impressive effect in the opening three weeks of the Championship campaign.

Even though he left the role in December, there’s no doubt that his set-piece expertise helped the Saints to reach 87 points, earning a place in the play-offs, which eventually saw Southampton promoted back to the Premier League instantly.

The Swedish manager, who has had experience as a set-piece coach in Arsenal, Brentford, Malmo FF, and Southampton, left to pursue his career as head coach at Lillestrøm in the Norwegian top flight.

However, fresh reports are stating that he could be reunited with ex-Saints director of football James Wilcox, this time as a set-piece coach at Manchester United, with Wilcox being appointed technical director following the change in ownership in the red side of Manchester, as they continue the revamp of Erik Ten Hag‘s backroom staff.

Lillestrøm are sat in the middle of the league but are precariously close to the relegation spots.

Nevertheless, from a set-piece perspective, Georgson continues to display where his strengths lie, with 10 of 18 league goals coming from dead balls (56%).

At every level, the Swede has been able to positively influence his team’s set plays with an even share of goals being scored from corner kicks, free kicks and throw-ins, paying close attention to each element of set pieces, including goal kicks.

In this tactical analysis, we will delve into the Andreas Georgson tactics behind Lillestrøm’s corner kicks, with an in-depth analysis of how they have used runs from the far side to be dangerous from corners.

This set-piece analysis will also explore the various ways in which they have attempted to create aerial advantages for their players and how Andreas Georgson has evolved his ideas over the last year.

Andreas Georgson Attacking Corner Kicks

To start with, the overall method behind the corner kicks has been the same here as it was at Southampton.

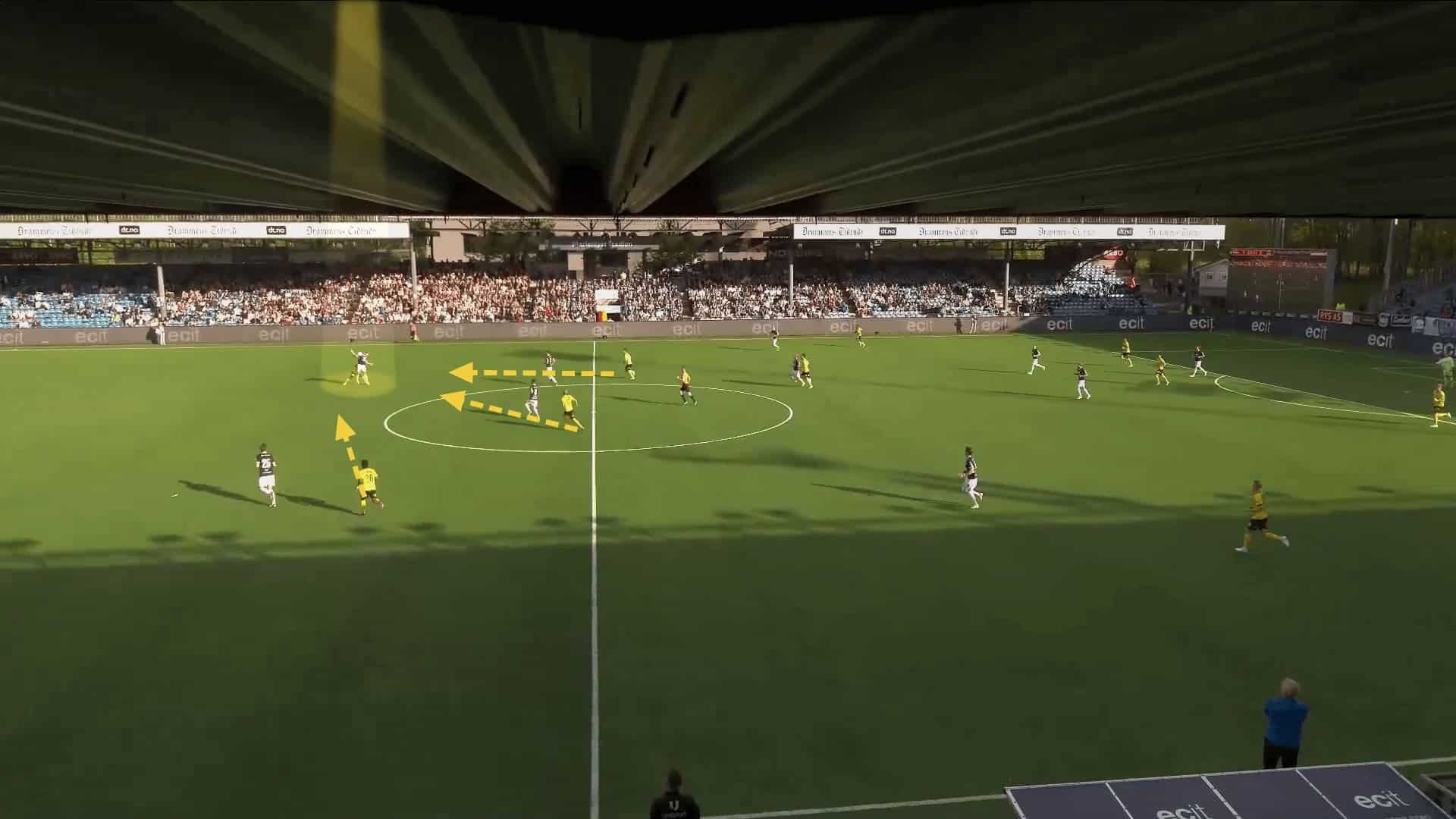

The attacking unit starts at the far side of the six-yard box before making runs to different parts of the six-yard box.

The position of the players, starting inside the six-yard box, takes away depth from Lillestrøm’s attacks, removing the ability for players to attack the ball and generate powerful efforts on goal.

However, this is not as important when the ball is aimed at areas inside the six-yard box, from where power isn’t necessary to beat the goalkeeper.

Lillestrøm tactics stretch opponents horizontally, attempting to find spaces between defenders where they can win the first contact.

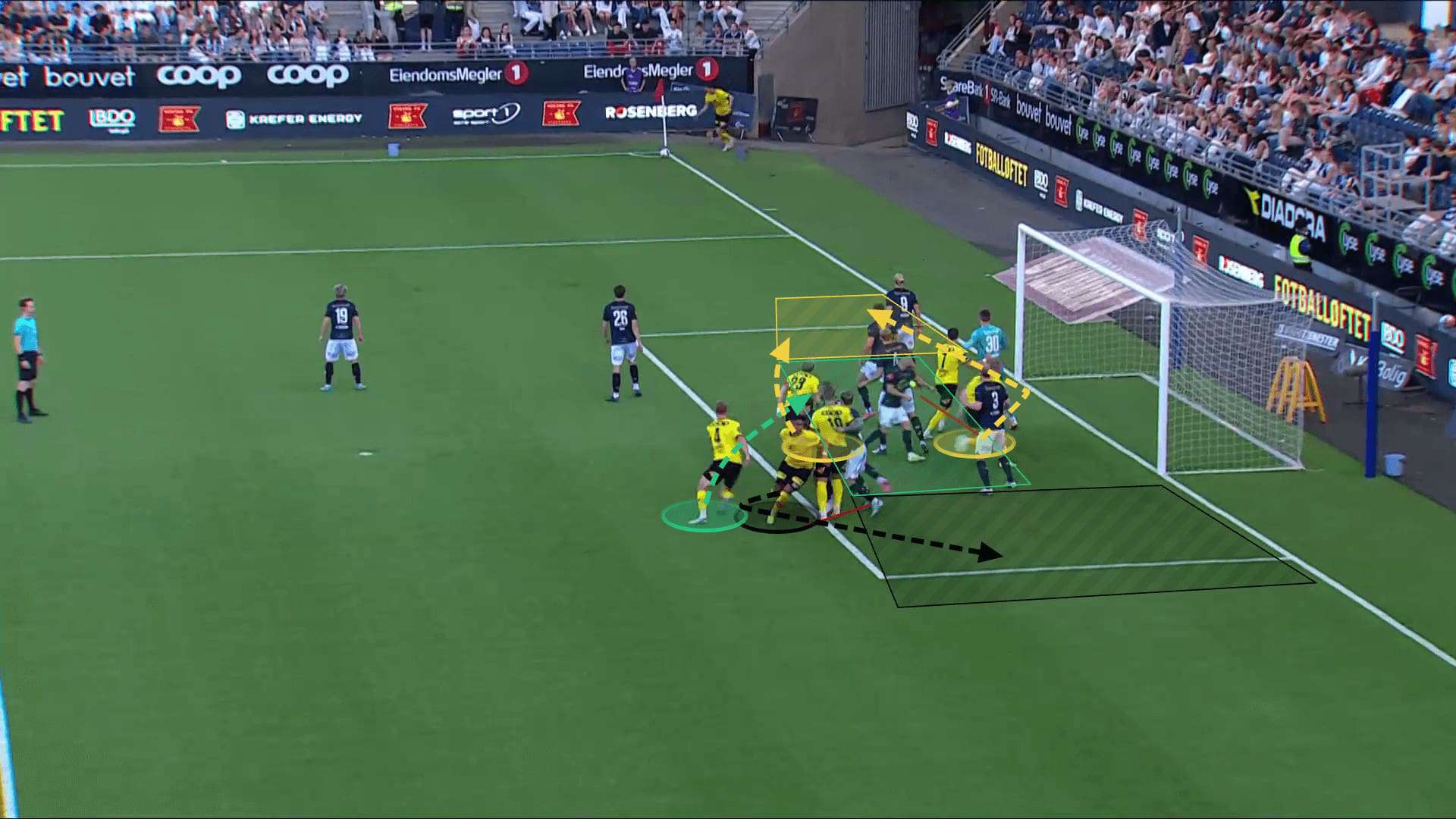

The image below is used to split the six-yard box into different areas, to show what is expected in each area, and to clearly see which players are assigned to attack which space.

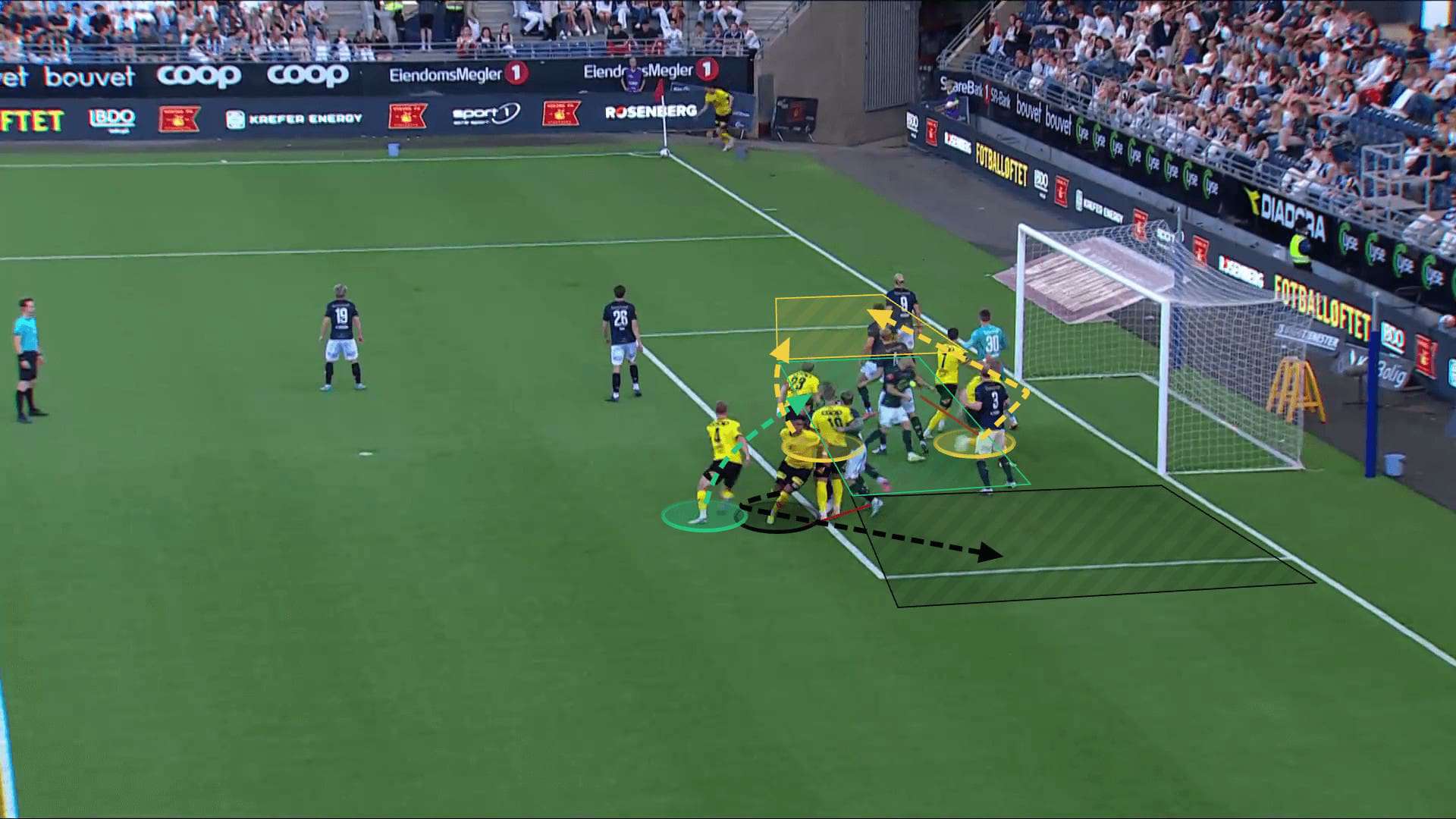

They use four players starting in the black zone, while two players start in the green zone.

In the yellow zone, players are expected to flick on low crosses to more dangerous areas while also dragging zonal players away from central areas.

Lillestrøm attempts to deliver the ball into the green zone, where players attempt to arrive and direct the ball goalwards with the area becoming easier to access due to the block on the goalkeeper.

In the black zone, attackers start their runs, while some stay in the zone to collect rebounds following the first contact or attempt to win aerial duels and make the first contact following heavier crosses.

When focusing on the two players who start in the green zone, just by the keeper, one player stands his ground and can be seen blocking the goalkeeper, preventing him from stepping off the line to claim the ball.

The second player can be seen making a run around the goalkeeper towards the near post area, where he can arrive unmarked by using the goalkeeper as an obstacle for a defender tracking his movement.

The four attackers who start at the far side of the six-yard box have attempted different methods to ensure players can arrive in the yellow, green, and black zones.

In this particular example below, a screen is set for one attacker to arrive in the black zone, while two players can make darting runs into the green and yellow zones, having gained separation by making their movement from the defender’s blindside, which allows them to build momentum without the defender reacting and tracking the movement instantly.

As mentioned earlier, everything that Lillestrøm does aims to target the central space in the six-yard box, where winning the first contact can ensure a high-quality chance and, most likely, a goal.

This is only possible when the goalkeeper is prevented from controlling the space around him through the use of a screen.

Where Georgson seems to have adapted and refined his routine from his time at Southampton is by consistently blocking the goalkeeper, meaning that the ball can always access the high-value green zone.

At the same time, the attackers must do their bit by creating advantages to beat their opponents in aerial duels in the green zone.

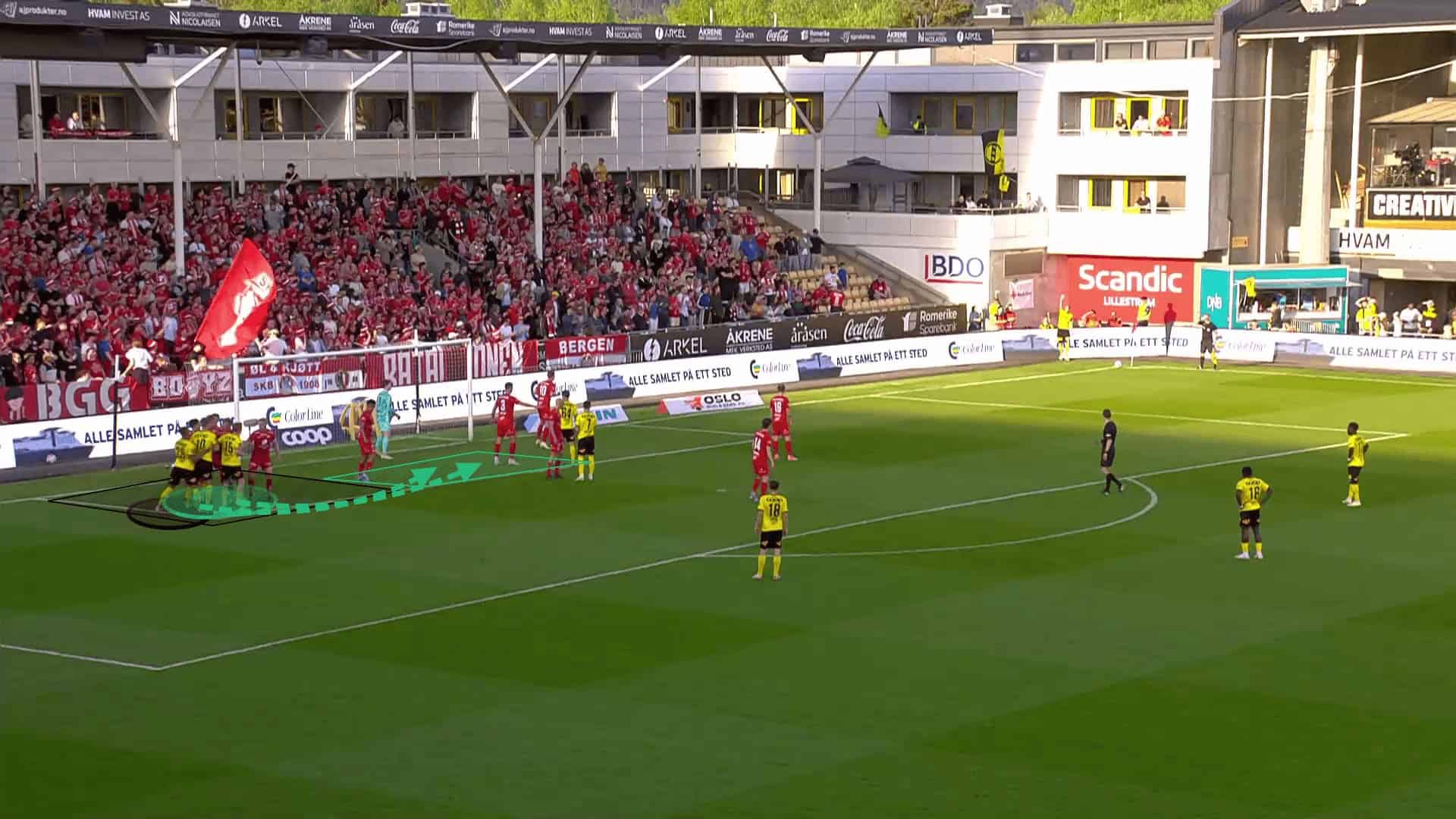

One other method Georgson has used to help attackers gain separation, and advantages in aerial duels in the six-yard box are implementing the ‘train’ setup.

This consists of each attacker being touch-tight next to the player in front, making it impossible for defenders to be tight when tracking runs.

As we see in the example below, the three attackers are using the setup, which allows the players behind the first member of the unit to arrive in the green zone with momentum.

Although the idea is good, the player at the front still allows his defender to remain tight, meaning the advantage does not apply to him.

The last player remains in the black zone, meaning he isn’t making use of the potential advantage he is gifted.

As a result, only the second (middle) player who attempts to arrive in the green zone reaps the rewards of the ‘train’.

The attempts to deliver the ball into the six-yard box offer big rewards, but it also comes at the risk of needing an accurate and consistent delivery.

As a result, balls are often either under or overhit and arrive in the yellow and black zones rather than the central green zone.

Therefore, it is essential that the player arriving at the near side of the six-yard box arrives with good timing and is able to delicately flick the ball to his teammates in the six-yard box.

There have been many instances where a flat delivery has been cleared by a defender due to the attacker’s poor timing of the arrival at the yellow zone.

At the far side of the six-yard box, inside the black zone, Lillestrøm have faced further problems when reacting to overhit crosses.

As the attacking unit starts their movements from that far side (black zone), any player whose role is to remain in that zone has to wait, meaning he is static during the attempt for the aerial duel.

Rather than arriving in that space, the player waits in the space and has no ability to gain momentum and receive an advantage when competing for the ball.

For this to be effective, any player who waits in that zone should be strong enough aerially to win the duel without an advantage, someone who is extremely dominant physically in aerial duels, so there is a mismatch.

This routine is similar to how Arsenal was able to be a set-piece threat last season.

What Arsenal has done to ensure they are receiving advantages across all zones is by making the attacking unit start even deeper in the far side of the penalty area, where players can make the same runs as they had done.

This would also give the players the chance to arrive at the black zone, where they use their momentum to win aerial duels.

Another area in which Lillestrøm dominates set-pieces is their dominance in the second phase.

Georgson continues to use three players around the penalty area, where the two outside players are more creative and able to control clearances and quickly deliver the ball back into dangerous areas.

The central deeper player is defensive-minded and can handle ground and aerial defensive duels while having the anticipation and awareness to put out fires before they start.

Last season at Southampton, short corners were more frequently used, meaning one attacker in the box was sacrificed in attempts to lure out defenders and change the picture inside the penalty area.

However, by focusing more on direct crosses, Lillestrøm consistently have a bigger number of attackers in and around the six-yard box, helping them to react and win the second balls more often.

Andreas Georgson Free Kicks + Goal Kick Routine

From free kicks last year, Georgson had been using early runs to disrupt the height of the defensive line.

The early run would bait a defender into tracking the movement, where the defender would be deeper than the rest while the ball hadn’t been delivered at that point.

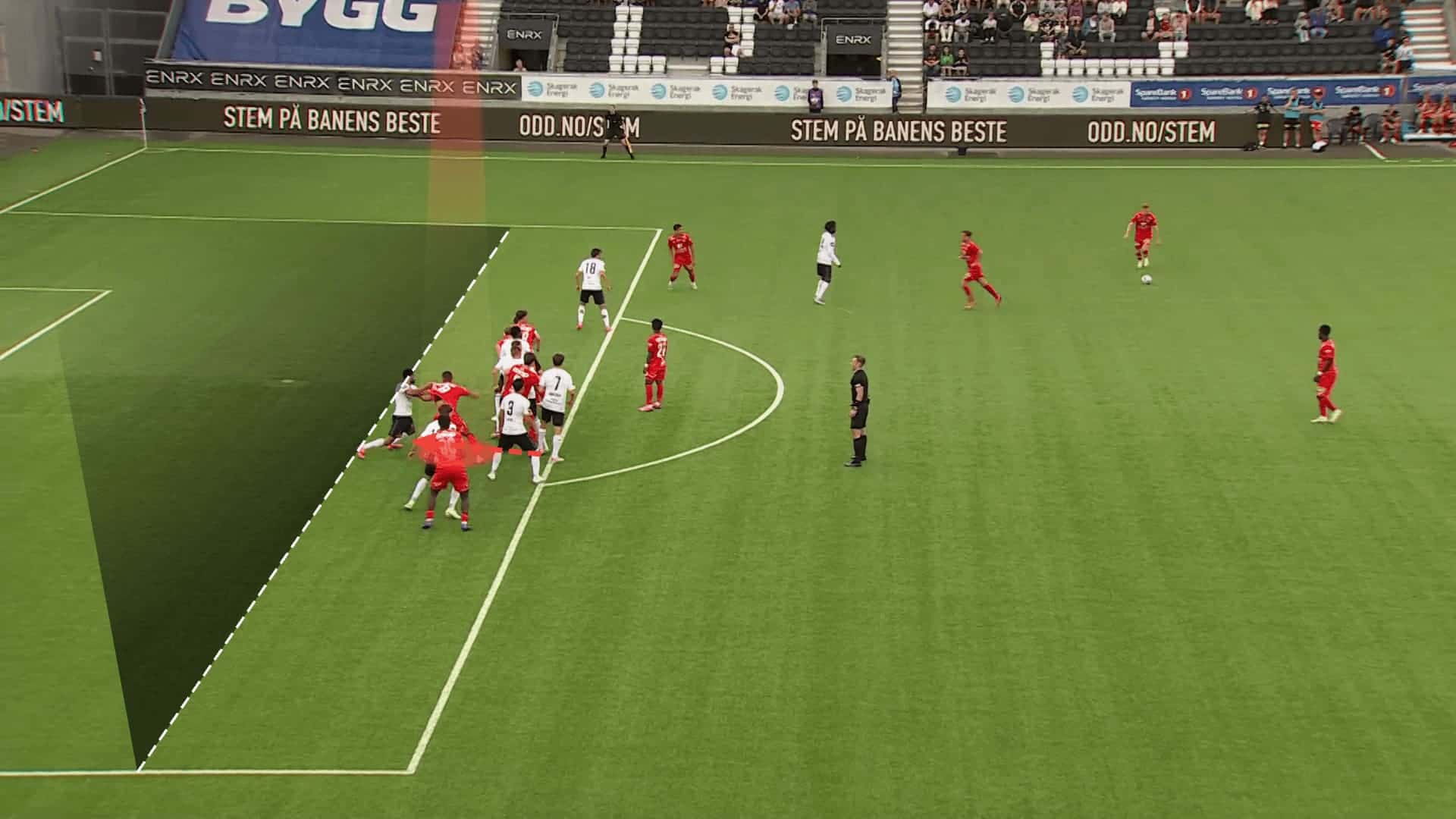

At Lillestrøm, a new way to alter the height of the defensive line has been through physically forcing one member of the defensive unit to move deeper than the rest.

As we can see in the example below, one attacker engages with a defender, where they are holding each other, and it allows the attacker to force the defender to take a few steps back.

As a result, the defensive line is much deeper than before, and so all the Lillestrøm attackers can make their runs in behind before the ball is played.

The early run means they can gain a yard on their marker and arrive in space first without the risk of being offside due to the defensive line being pushed deeper and other defenders not being aware of what is occurring behind their backs.

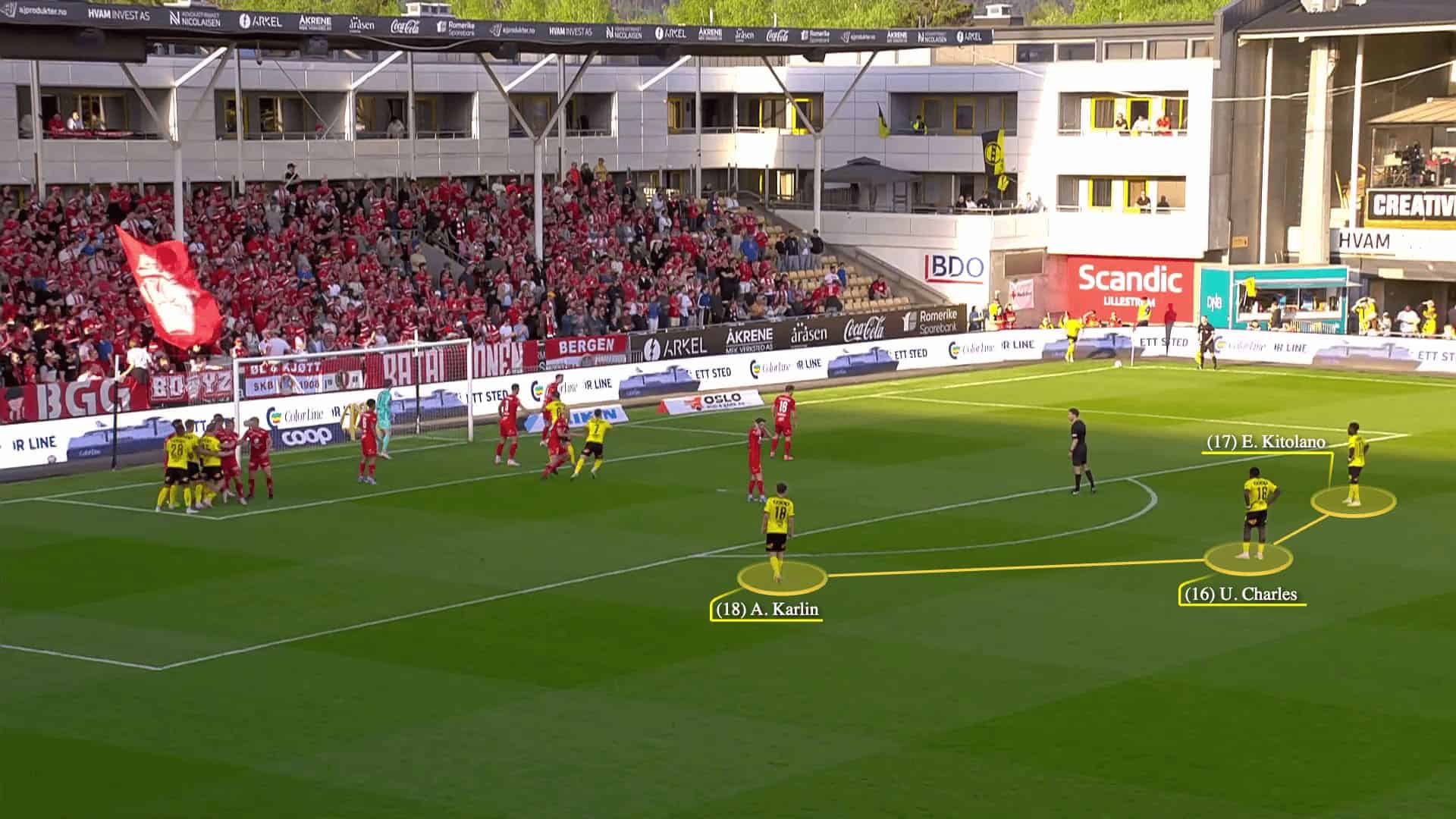

From deep central free kicks, Lillestrøm have often stretched opponents by using two attacking units, one on either side of the penalty area.

In doing so, they are able to create 3v3 situations on both sides, where attackers have more space to try and lose their markers before arriving in space.

The most central member of the attacking unit (3v3) can be seen using his teammates, who block off defenders, to arrive in the space highlighted.

An attacker also starts on the penalty spot, where he cannot receive the ball from his offside position but is in an excellent position to receive the second pass after the ball is crossed into the black area in the image below.

Andreas Georgson has also shown his creativity by using goal kicks to his advantage and creating goalscoring opportunities from his own six-yard box.

The plan is to build out from the back, but when opponents attempt to press man to man, Lillestrøm has used the pressure to their advantage by attracting opponents to the ball before using a long ball to find the isolated attackers.

As the goalkeeper takes the short kick, the attacker drops deep to offer a shorter passing option, which creates 1v1 situations around the halfway line.

From there, the ball is played long to the isolated attacker.

Even if the attacker doesn’t win the aerial duel, he can battle for the ball and prevent the defender from getting much contact on the ball, meaning the ball will only drop in a 10-yard radius or so.

With the knowledge that the ball will remain in the opposition half, the near players can sprint towards the ball to collect the second ball, from where they can generate counter-attacking opportunities.

Going long against man-to-man presses from goal kicks to isolated attackers has already earned them two goals in the opening half of the season, and if opponents start to worry about the threat of this and drop deeper to prevent the 1v1 situations in their own half, it will only make the build-up efforts easier in the future, a win-win.

Summary

This Andreas Georgson tactical analysis has shown how Georgson has been setting up Lillestrøm when attacking set plays so far this season, highlighting both the good and the bad elements of his set play preparation.

It is clear that Georgson is building and expanding on last year’s ideas and continues trying to perfect his routines.

If he does earn a move to Manchester United, it would be great to see yet another side employing a set-piece coach, making the Premier League a hotspot for set-play creativity and excellence.

Comments