At the end of the 2018/19 season, Liverpool narrowly missed out on the Premier League title after a dramatic title race with rivals Manchester City. In virtually any other season, their form that year would have been worthy of the title, but it wasn’t to be and Liverpool had to find a way to ensure they could win the title the following season.

Now, having won the title last season, they enter the new season considering how they can retain their title. Despite a record-breaking season, Liverpool will no doubt be looking for ways to improve heading into the season, and assistant manager and lead analyst Peter Krawietz revealed in an interview that he used the Corona Virus break to analyse previous matches and to begin to plan for this coming season. On this analysis, Krawietz said:

“From this, something fundamental has now emerged that we want to use in the coming months.

“It’s mainly about details and small adjustments around our game principles”

As a result of these quotes, I decided to try and mirror Krawietz’s process by identifying a series of games where Liverpool didn’t perform at their best, before analysing what went wrong in specific situations in those games. The games chosen were based on Liverpool’s low xG compared to their possession stats, as one of the most common games Liverpool are likely to face is those where the opposition sit deeper and Liverpool have to rely more on their positional play. Therefore, this tactical analysis will analyse some of the key features and principles of Liverpool’s positional play, before looking at how these principles can be edited or refined in order to benefit their game this season.

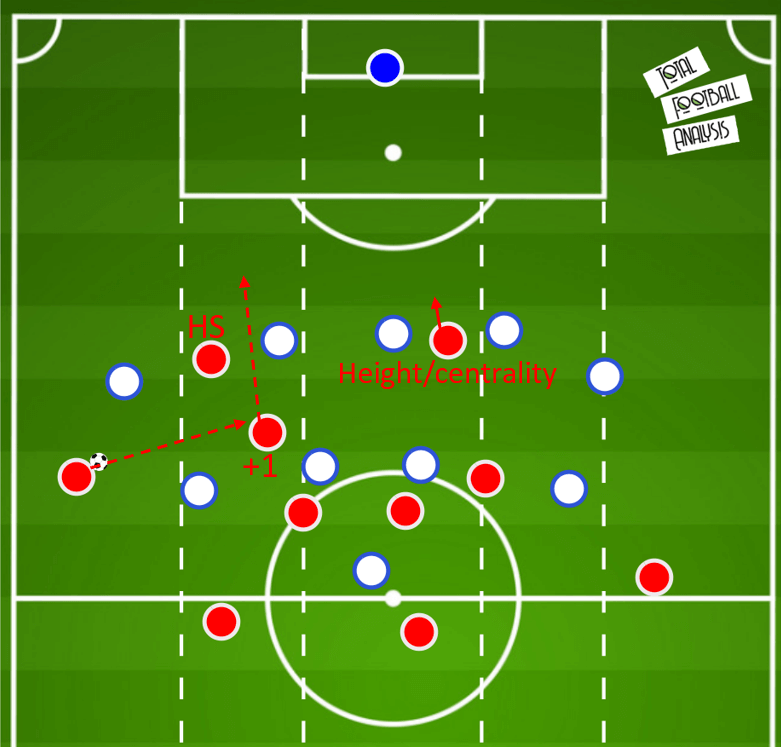

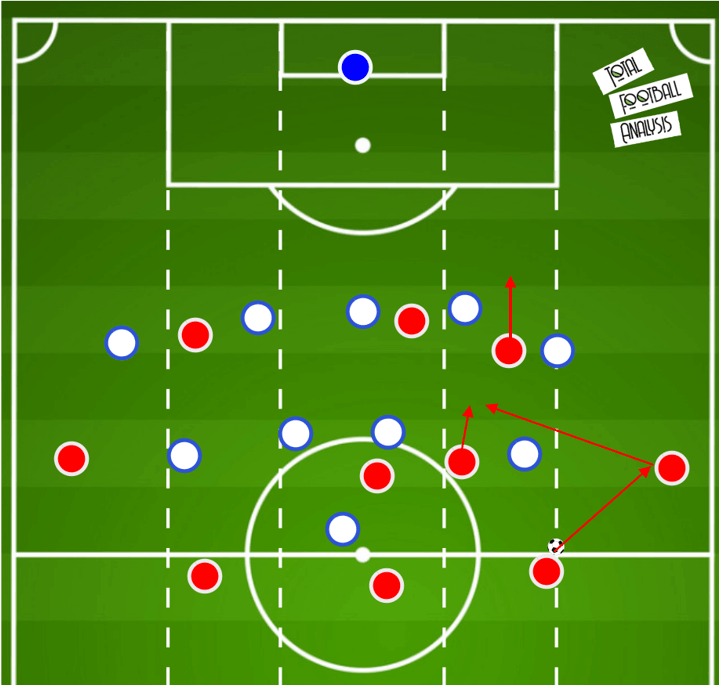

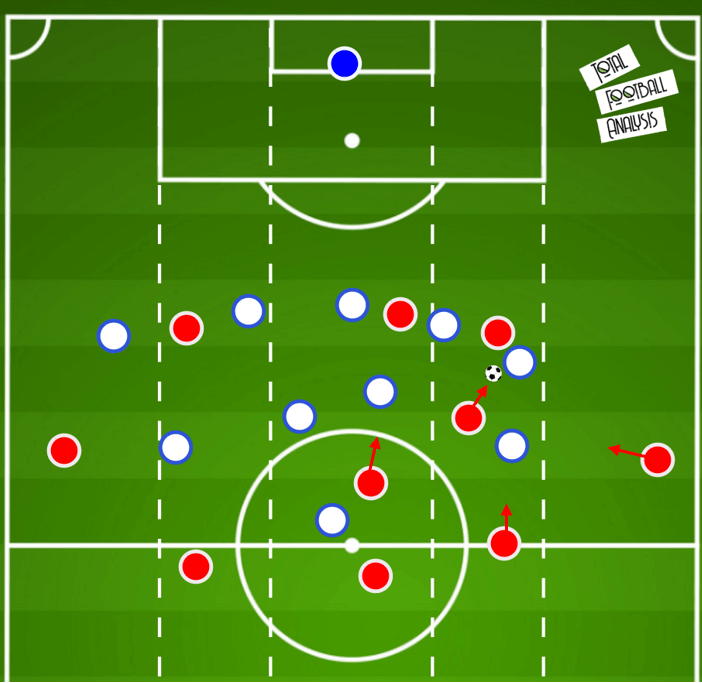

Positional play structure

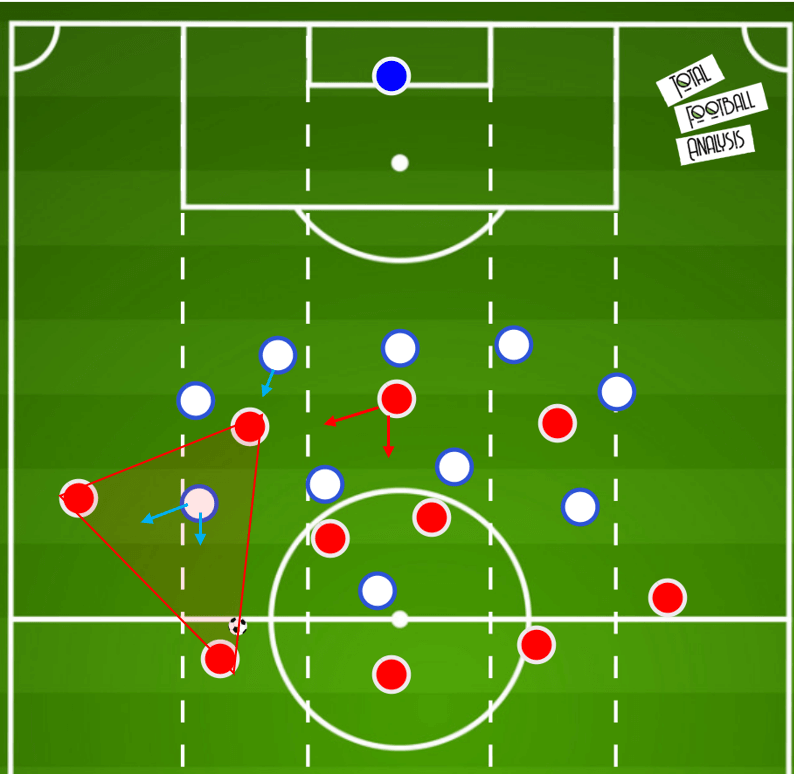

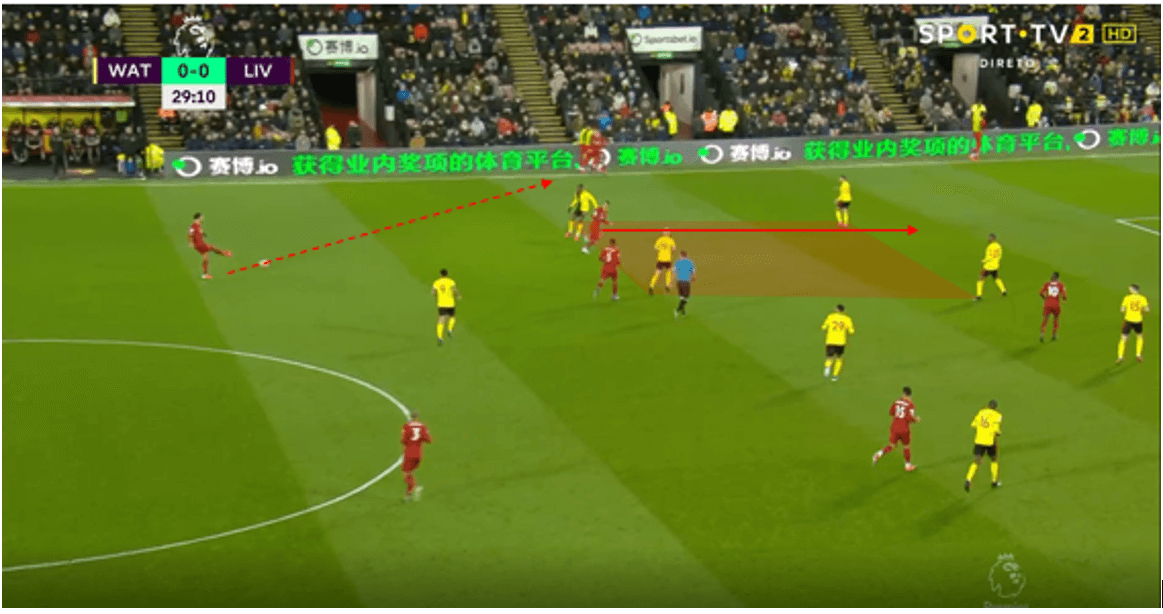

Liverpool’s most common positional play structure resembles this image below, with this particular example taking place against a 5-4-1 formation. A central midfielder, usually one of the wider ones, will drop into the deep half-space and form a back three, with the aim of this being to allow Liverpool to build vertically in the half-space and to also potentially engage the opposition’s second line of pressure, enabling the full-back more space and greater freedom in attack. This is one of the reasons Liverpool’s full-backs excel creatively and Liverpool’s midfielders don’t.

The inside forwards occupy the half-space, while the full-backs try to open the lane to the half-space by remaining wide, which is a common principle in most positional play. Central midfielders aim to stay in the centre and try to pin the opposition central midfielders here.

This triangle shape between the full-back, inside forward and deep half-space player will come up throughout the article, and it is a main principle the side seems to value.

Liverpool of course also build in a back four at times, in which case the two balls near central midfielders largely act as cover for the attack and then occupy the central areas. At times the far central midfielder will make movements in behind the second line, and a ball near the central midfielder at times will rotate into the half-space or even provide width.

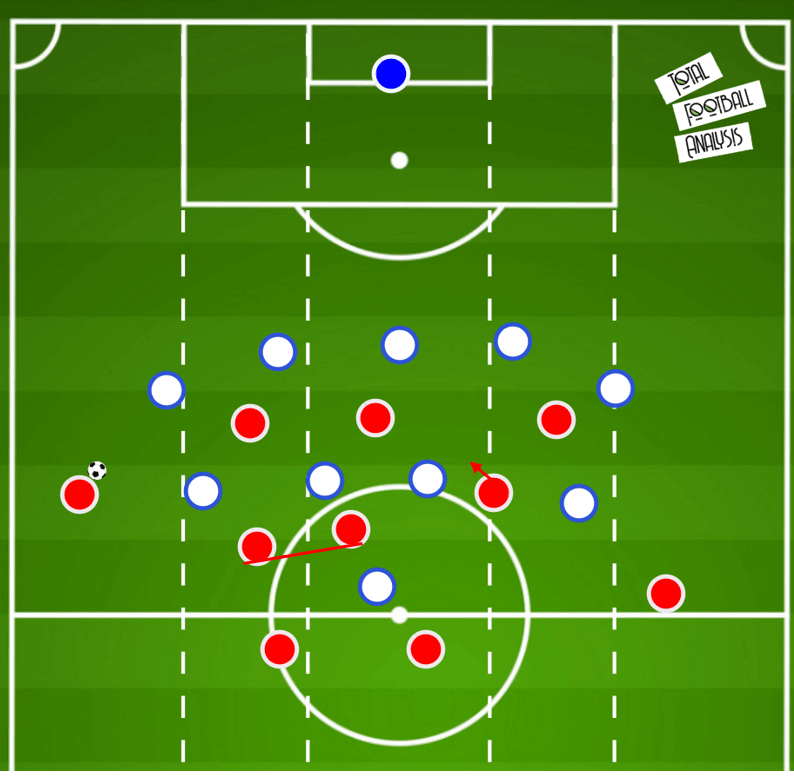

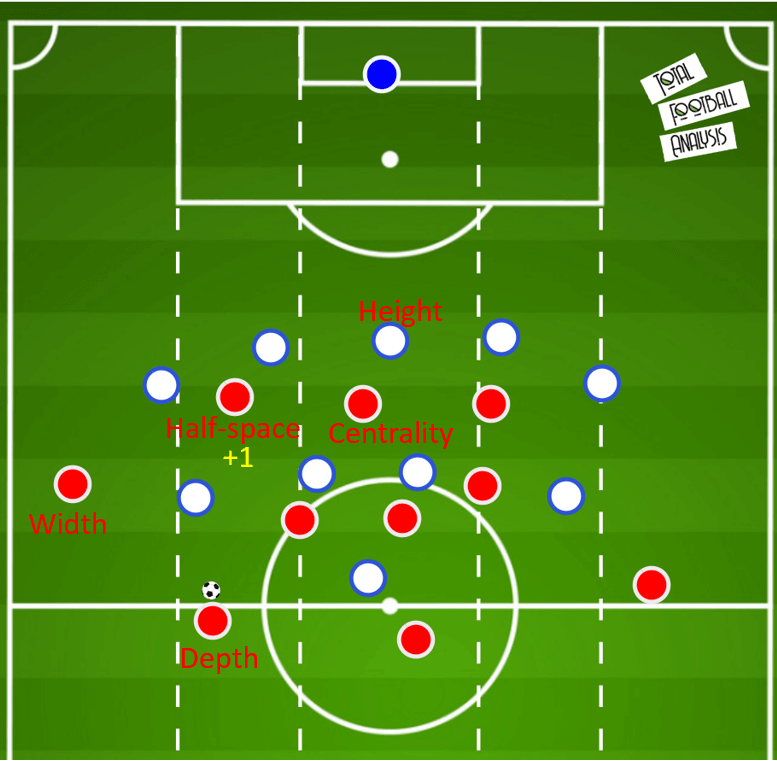

Liverpool’s system is also role based, like all good positional play systems. By this, I mean that Liverpool have roles that need to be filled for their principles to be executed, but who occupies these roles can be largely irrelevant to a degree. We can see the roles highlighted below, all of which were explained above. We can see in the diagram the central lane involves both height and centrality, while the half-space also needs occupation, and can also need an extra player +1 in order to overload and build through this area. Variations such as double width, which involves having two players providing width, can also be seen in some situations. Again, we will come back to this idea later.

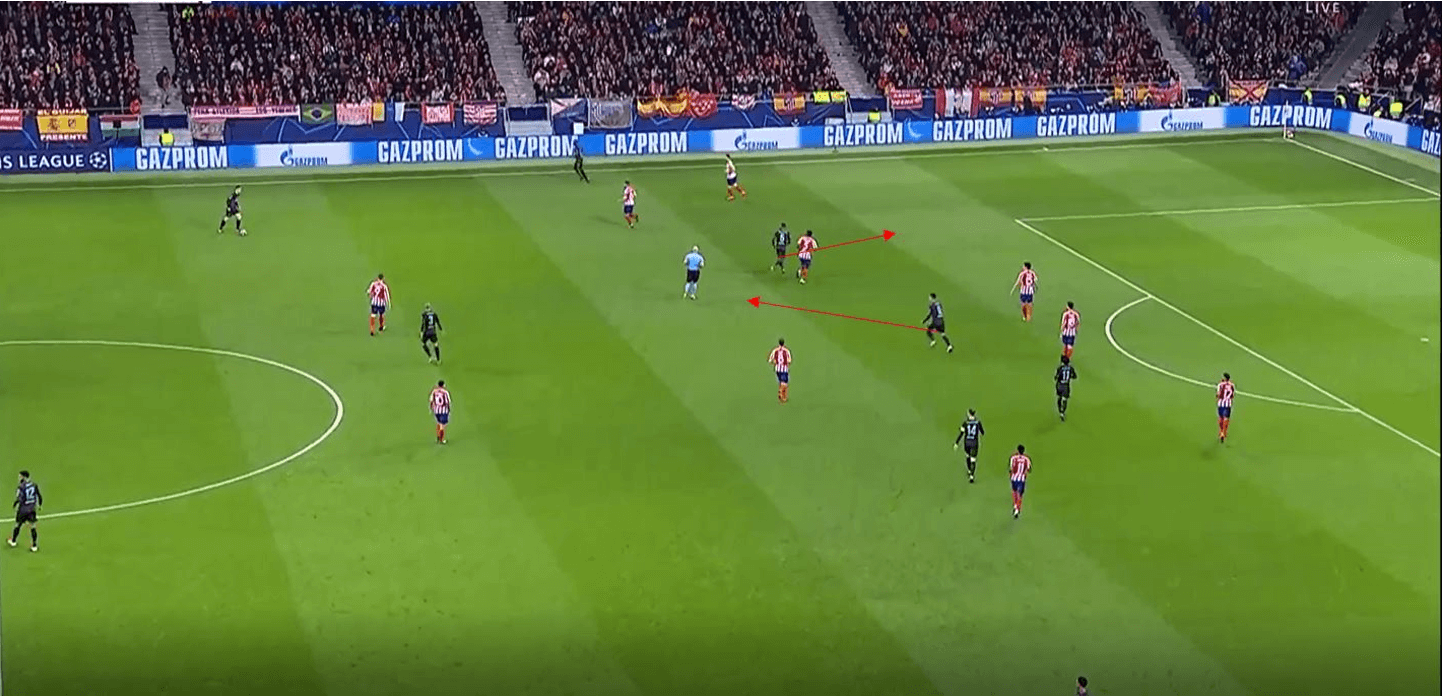

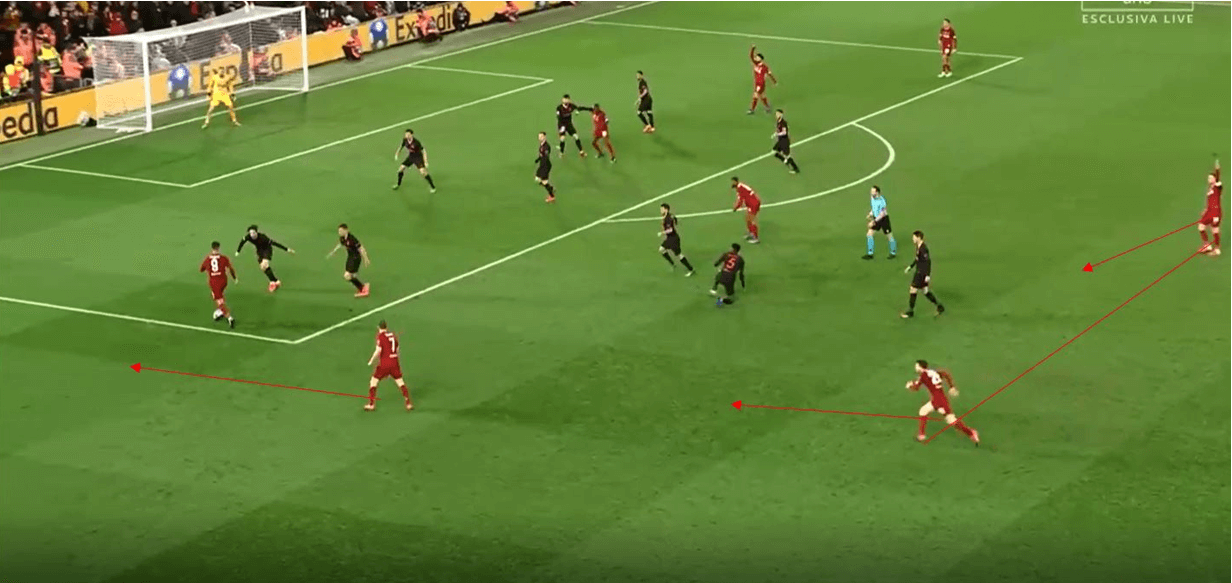

We can see a basic example of their principles in play here against Atletico Madrid, with the necessary roles fulfilled but the personnel slightly different. We can see Robertson is on the ball and has not pushed higher, and so he instead provides the depth to the attack. Mané therefore moves wider to provide width, while Gini Wijnaldum moves higher into the half-space. Wijanldum’s run forward occupies the centre back, and so Roberto Firmino drops to overload the half-space and occupy the space that Wijnaldum has vacated.

Rest defence and risk vs reward

Much of Liverpool’s play relies on balance in the side, and it is this balance which has made them so successful. Liverpool aren’t as dynamic in their positional play as Manchester City are, but at the same time, Liverpool are probably more balanced and defensively sound within their positional play. This is largely down to another principle of their positional play, in that they usually like to have at least two players positioned behind the ball within counter-pressing range.

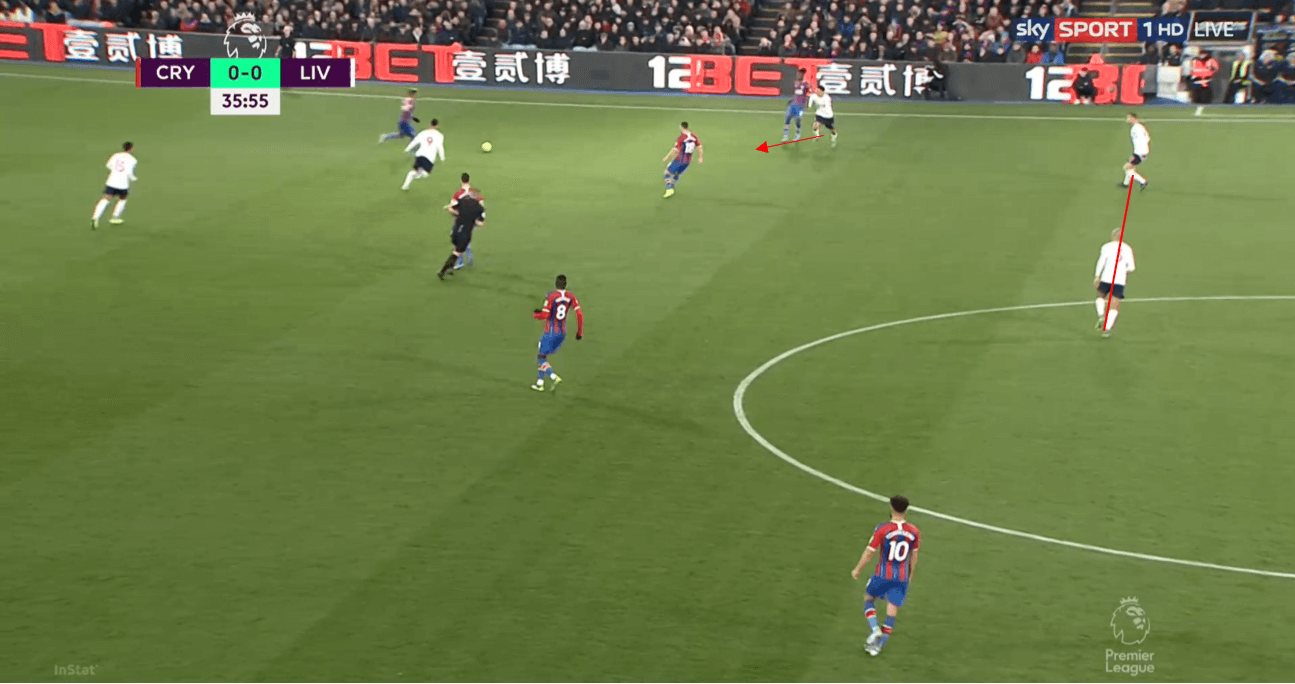

These two players behind the ball are usually the central midfielders, while the full-back can also counter-press from the wing when needed. We see a good example here against Crystal Palace when Liverpool have this rest defence, with Alexander-Arnold counter-pressing from the wings and Henderson and Fabinho being in a position to cover passing lanes and counter-press inwards if needed. The closest player can apply direct pressure on the ball initially.

In a similar way to their offensive principles, the roles within the team can be slightly flexible, however they are usually not as flexible simply due to the skill sets of players. We can see here Wijnaldum provides the width, and so Robertson and Henderson act as that cover for the attack.

As a result, when the ball is lost in the half-space, Liverpool can counter-press well here to sustain their attack. This allows Liverpool to slowly grind down opponents and prevents the opposition from counter-attacking and pushing higher up the pitch.

The balance of risk against reward comes into play with regards to how rest defence interacts with positional play. If Liverpool consistently want at least two midfielders behind the ball ready to counter-press, this obviously hinders the positioning of the team offensively. Any possible ideas or variations in their positional play therefore need to consider the implications on the rest defence. Their match against Atletico Madrid is a perfect example of one tiny misjudgement in rest defence costing them. Liverpool here are pushing for a goal in extra time, and they are initially set in that rest defence of two players behind the ball and covering the attack. Andrew Robertson begins a run forward, as Liverpool can’t progress the ball.

Robertson makes a supporting run, but Simeone’s side are able to recover the ball. Robertson is therefore now in no position to counter-press, and Henderson alone cannot cover the passing lanes. As a result, Liverpool concede a goal from the counter-attack.

Part of Liverpool’s ‘problem’ therefore is balancing that rest defence with a good positional structure, and this is ultimately one of the biggest dilemma’s in football, specifically for possession based sides. Again to draw a comparison to Manchester City, Liverpool are generally less expansive and are instead more controlling of the game, and so they tend to grind teams down slowly, with the quality of their front line often compensating for a non-ideal positional structure. This makes them more dominant, but maybe less potent at times. Their game against Norwich was a perfect example, where they controlled the game completely and slowly broke down that block, scoring in the 78th minute. An ideal solution then is one which doesn’t compromise defensive stability much, but also benefits the team’s offensive threat.

Finding the ‘ideal solution’

If we take a look back at the roles within Liverpool’s positional play, the workload around Roberto Firmino is perhaps what hinders Liverpool at times. Firmino is famed for his excellent movement (and rightfully so), but as we can see below, relying solely on Firmino to perform certain roles can have its disadvantages.

Liverpool’s front three is fluid, and so those roles discussed are covered by that front three often, but in some situations it could be argued that support from other teammates would benefit them. We can see a fairly typical example below, where Firmino drops in as a +1 to overload the half-space, while Sadio Mané occupies the half-space, looking to create a 2v1 on the centre back. Because Firmino drops from the centre, Salah comes across and acts as the height and central player. Liverpool are very capable of scoring from such situations, but the addition of an extra player within those roles seems as though it would benefit them. They do manage this on occasion, but often when not set the front three have to operate in this way.

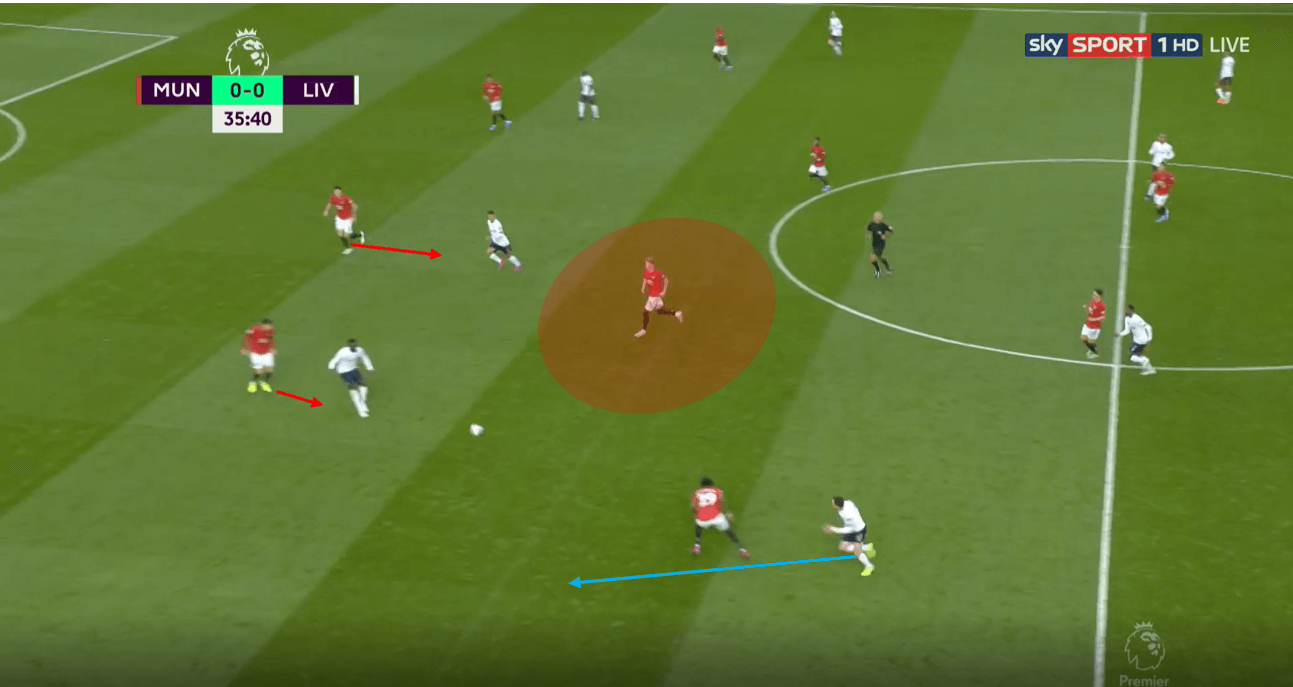

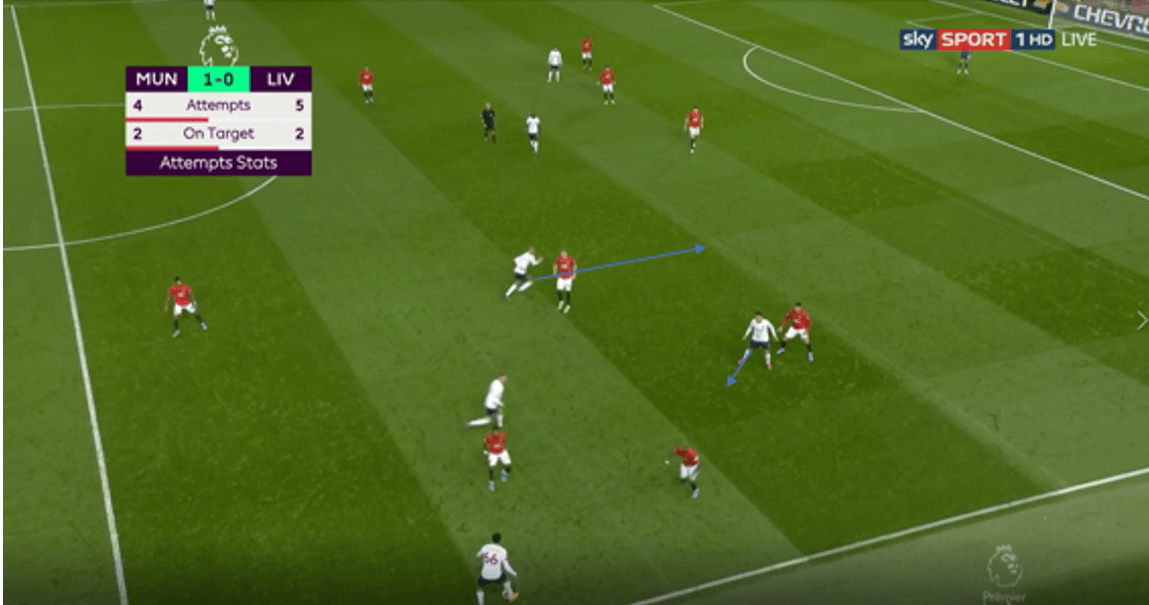

The main problem then is that creation of the +1 player, and we can see a few examples below of Liverpool becoming slightly isolated in the half-space. Here, Origi receives in the half-space facing away from the goal, and so clearly requires support for the ball to be progressed. Firmino doesn’t want to drop because he needs to remain central, and no midfielders are nearby to help. Jordan Henderson has pushed forward to the wide right position, with Liverpool potentially looking to play from the left eventually to the right as they do often, but here they just don’t have enough support around Origi to progress play. Origi is tackled/fouled, and Man United counter and score, with Andy Robertson looking to move forward to support Origi initially.

In this example here again, Liverpool lack that +1 player, as Andy Robertson here plays the ball into Mané in the half-space. Mané receives and looks to play the ball back to Robertson in order to then make a run in behind the centre back marking him. Mané in this scene therefore has to act as the half-space occupier, and the +1 player, and so it makes it much easier for Man United to react to and deal with. Liverpool need to find ways to make complementary movements consistently, as yes they are able to do it at times in games, but maybe not as consistently as they would like.

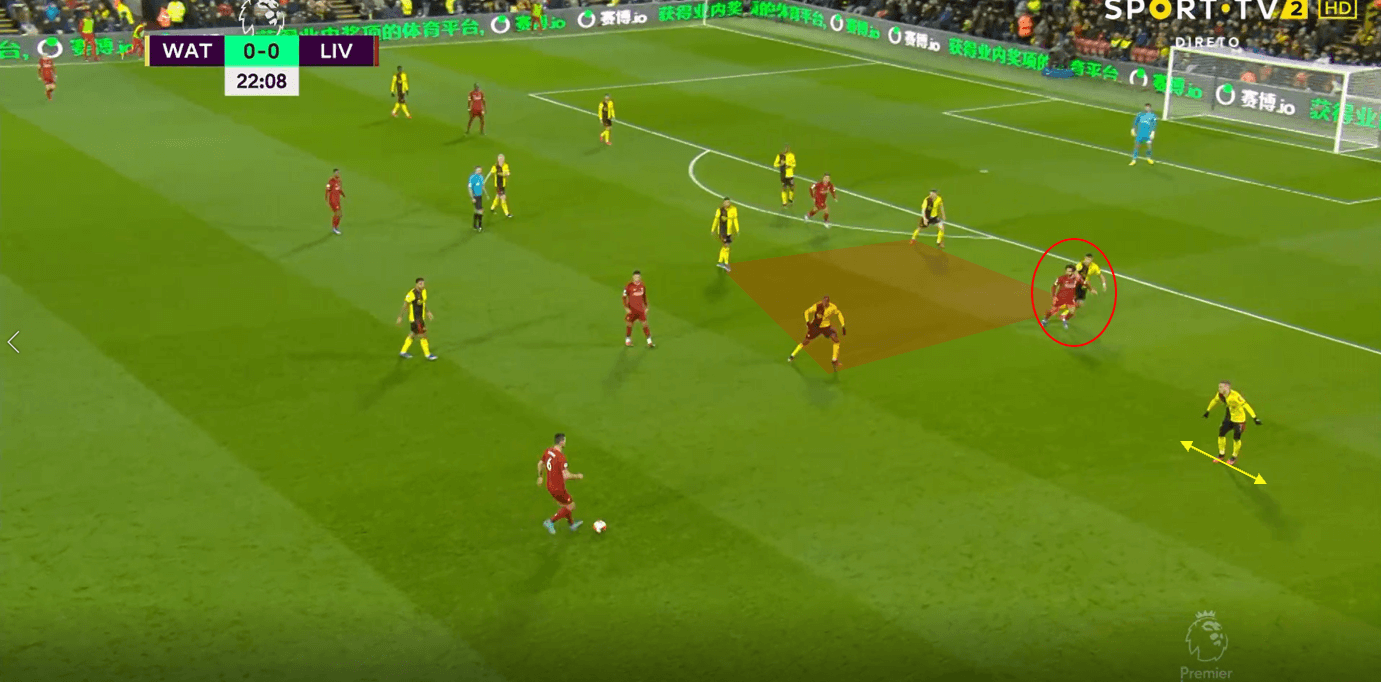

Here we see the wide centre back Dejan Lovren can directly access the half-space, where inside forward Salah can post up against the defender. Full-back Alexander Arnold can overlap, but Liverpool cannot really find a free player.

Again though Liverpool’s front three are excellent without an overload, and Salah and Mané are particularly adept at receiving with their back to goal. Salah has a signature move of backing into opponents consistently with his back to goal, often winning fouls by doing so.

Dynamic space occupation

One solution which would allow Liverpool to consistently create a free man against deeper opposition would be the use of dynamic space occupation from the midfield. Players such as Takumi Minamino and Naby Keita could start as part of a midfield three, and be tasked with the role of becoming that +1 player, or rotating around this role, when Liverpool have possession. Again, Liverpool do this at times, but it isn’t a designated role, rather an improvised response to problems set by the opposition.

Their usual response is for either a midfielder to occupy the far side, or drop into the half-space to form more of a 4-2-3-1, as we have seen elsewhere in this analysis. We can see an example of this below, where Salah moves out wide to provide width, meaning Chamberlain moves to occupy the half-space. Chamberlain here though doesn’t move from a deeper position into the half-space, and instead moves from the side into it. As a result, his body orientation is fairly poor and it harms the progression of the ball somewhat.

Dynamic space occupation, involves players moving into vacated space, often from a deeper position. The main advantage of this is that it improves that body orientation of the player in the half-space, and so if Liverpool can create a +1 in this way, it will benefit their ball progression. We can see an example below of Roberto Firmino deliberately moving deeper in order to then receive with forward facing body orientation, as well as to dismark any opponents. Firmino here though acts as the half-space occupier, with Mané acting as the central player.

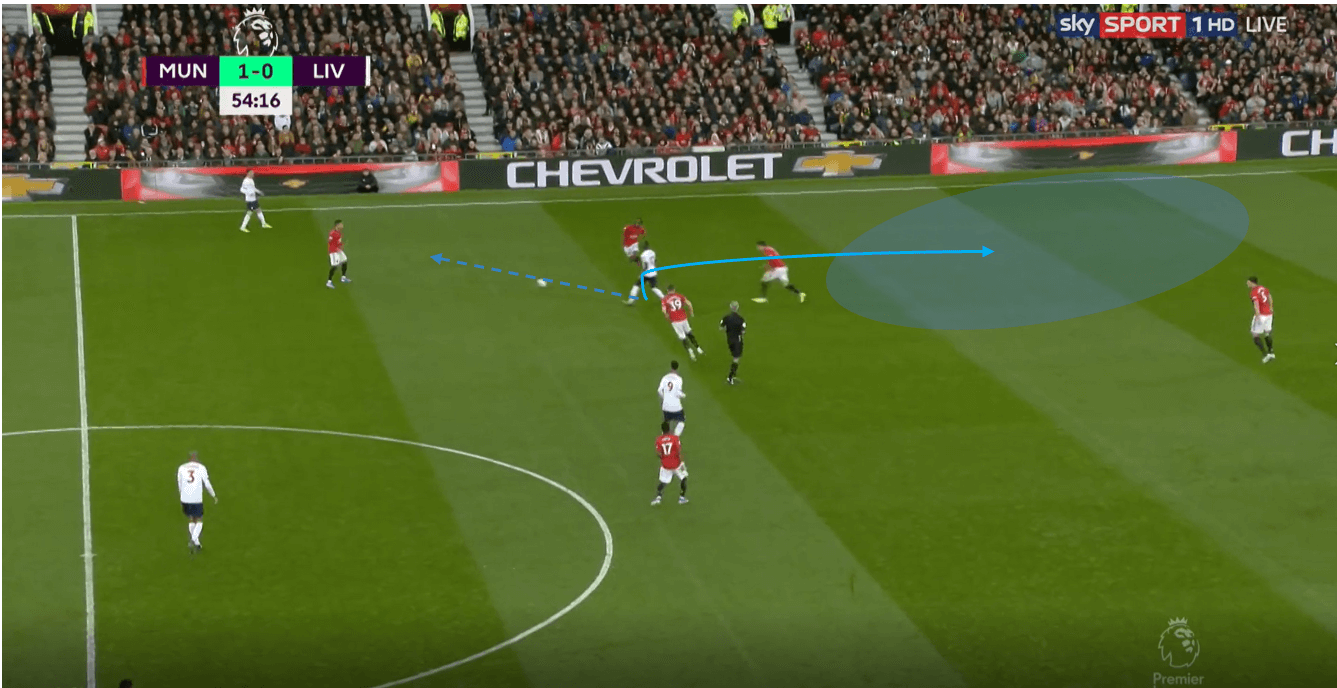

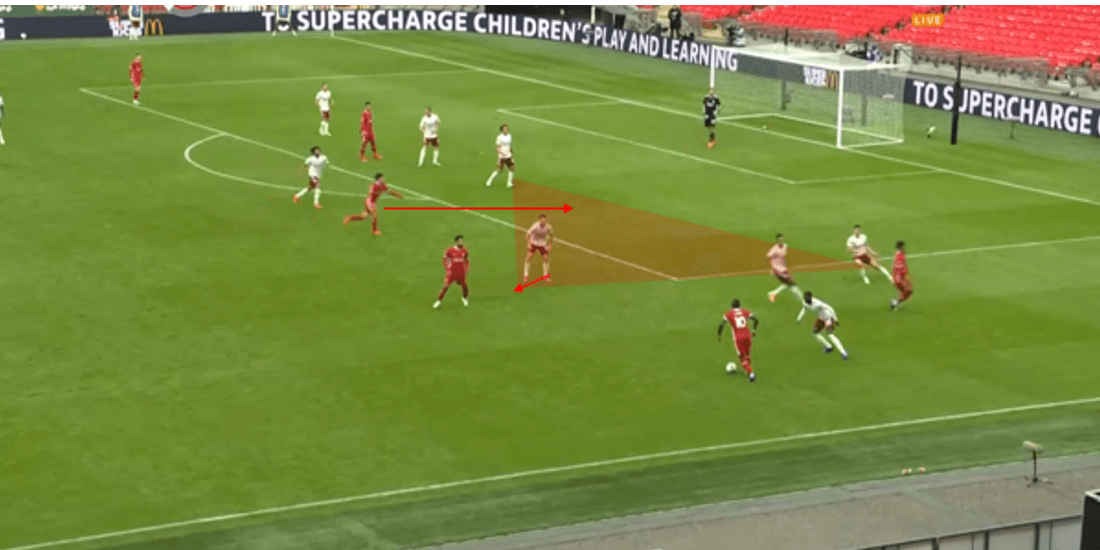

Takumi Minamino was brought on in the second half of the Community Shield against Arsenal, and his performance certainly shone some light on how this could work as a system. Liverpool switched to more of a 4-2-3-1, and Minamino’s positioning and movement changed the game for Liverpool. We can see an example here where Minamino starts deeper and receives between the lines with forward body orientation. Width is provided by the full-back, and Firmino has also come deep in the half-space, and so Liverpool get the opportunity to overload this area.

We can see in another example here, Salah occupies the half-space and drags a central defender forward, creating space in behind. Minamino then makes a run from deeper into this space, and Liverpool still have a player in the box to attack a potential cross.

Firmino’s movements to create space for teammates is excellent, and so having a player who can consistently link with Firmino and occupy these areas would benefit Liverpool. Situations like the one below have occurred previously this season for Liverpool, but again, they are often few and far between, and due to the dynamics of playing in that Liverpool midfield, it is not always possible for players like Fabinho to make these kinds of runs. Allowing Minamino or Keita to have a slightly freer role may benefit them in games where the opposition sit off. The shape may therefore resemble more of a 4-2-3-1 or 4-2-4 at times, but a 4-3-3 is always possible before players make that run forward.

How does this affect the rest defence?

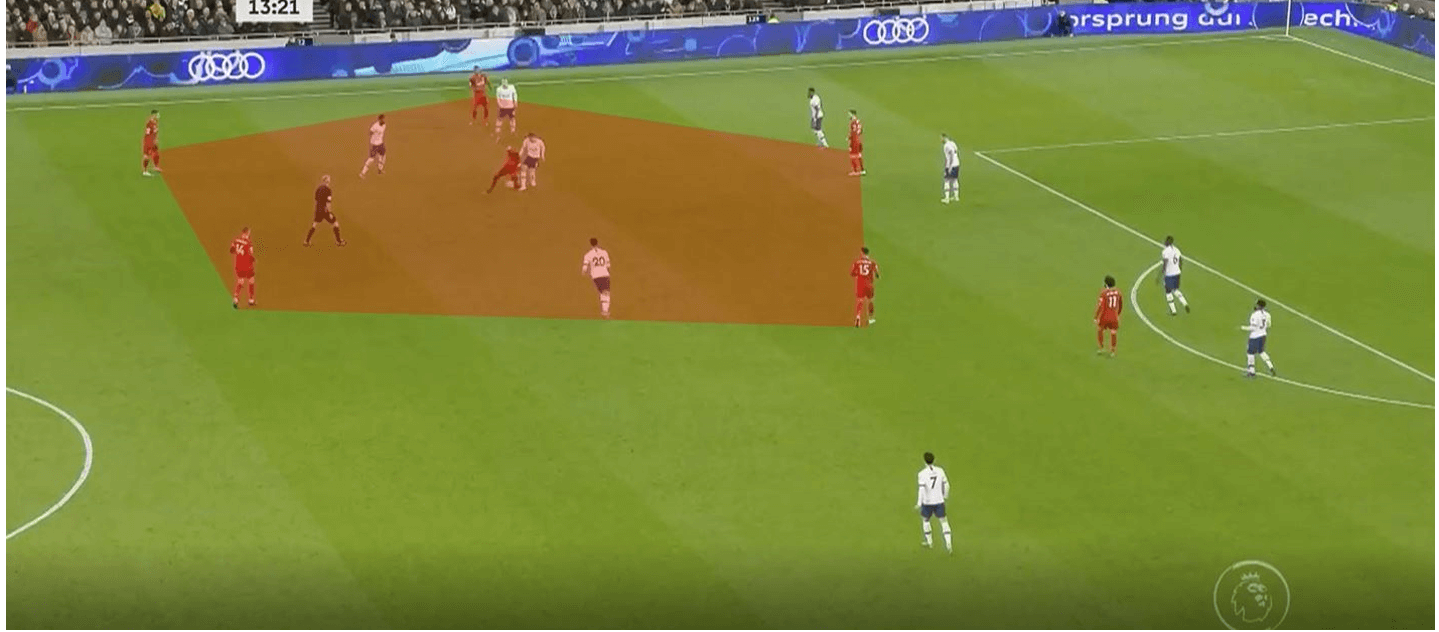

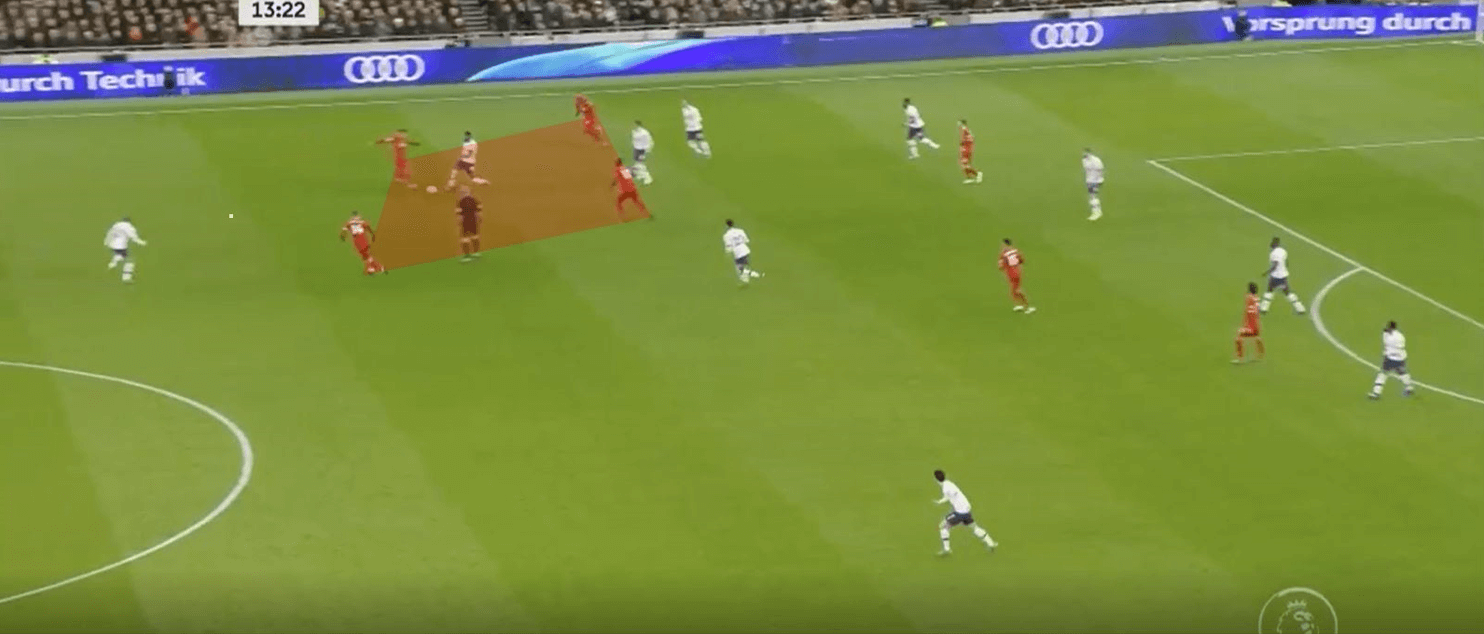

The idea around teams who rely on dynamic space occupation is that because players are moving forwards into empty space, if the ball is lost, they can simply continue their run forwards and turn it into a counter-press. We can see a situation below where one of Liverpool’s midfielders drops into a back three, while one looks to act as that overloader. The ball goes out to the full-back, which triggers a run in behind the second line by the midfielder.

The opposition full-back though is able to jump in and win the ball. As a result, the central midfielder has to move forward slightly to cover the opposition central midfielders. The central midfielder within the back three should be ready to jump forward also after they have passed the ball, to increase compactness around the ball further. The full-back can press inwards as usual from the wings, and the far full-back would move to a more compact position, and Liverpool should as a result be able to remain balanced. In some situations, that more attacking oriented midfielder will have to make their run with some caution, and in games where Liverpool think they need more balance in midfield to press with and deal with counter-attacks, players will simply make less of these movements.

Conclusion

The problem Liverpool face regarding balance is not a new or unexpected one, and it is often individual ‘gambles’ in the game which make the difference. Often, Liverpool are able to break down the opposition using other methods over time, but at times they can struggle and this article simply suggests a possible way they can attack without compromising their rest defence too much. As Klopp said after the Arsenal match, these kinds of matches against a deep sitting opposition require sharp decision making and fresh minds, and they are by no means easy and so it will be interesting to see how Liverpool’s tactics develop over the season, particularly as it looks as though teams will sit back potentially even more than they did last season. If they maintain that balance shown in this scout report while still penetrating teams, as well as managing all aspects of the game such as corners and throws, then it should be another very successful year for Liverpool.

Comments