Last season, Régis Le Bris guided Lorient to a 10th place finish in Ligue 1 — their highest top-flight placing since the 2013/14 campaign, their final season under the leadership of Christian Gourcuff, when they finished eighth; they had quite a young squad to boot, giving the impression of quite a bright future for the Brittany-based club.

This season has seen fortunes turn for Le Bris and his side, currently sitting in 16th after earning just seven points from their opening eight league games of 2023/24. They can’t blame their attack too much for this poor start, as their 13 goals scored places them seventh in the league in that particular area, despite chance creation not being a solid point for them so far this term.

It’s the other end of the pitch, where the aim is to keep the ball out of the net, that has really stood out as a weak point for Les Merlus this term — they’ve conceded 18 goals in their first eight games this season, giving them the worst defensive record in France’s top-flight. With the league’s fourth-highest xGA tally (16.18), it’s clear they’ve been far too giving at the back this term — but why?

Our tactical analysis and team-focused scout report aims to examine what’s changed for Lorient this season compared to last and get to the bottom of their defensive issues. Furthermore, our analysis will highlight what Le Bris needs to change if he is to oversee the necessary improvements in Lorient’s game.

The problem is not between the sticks

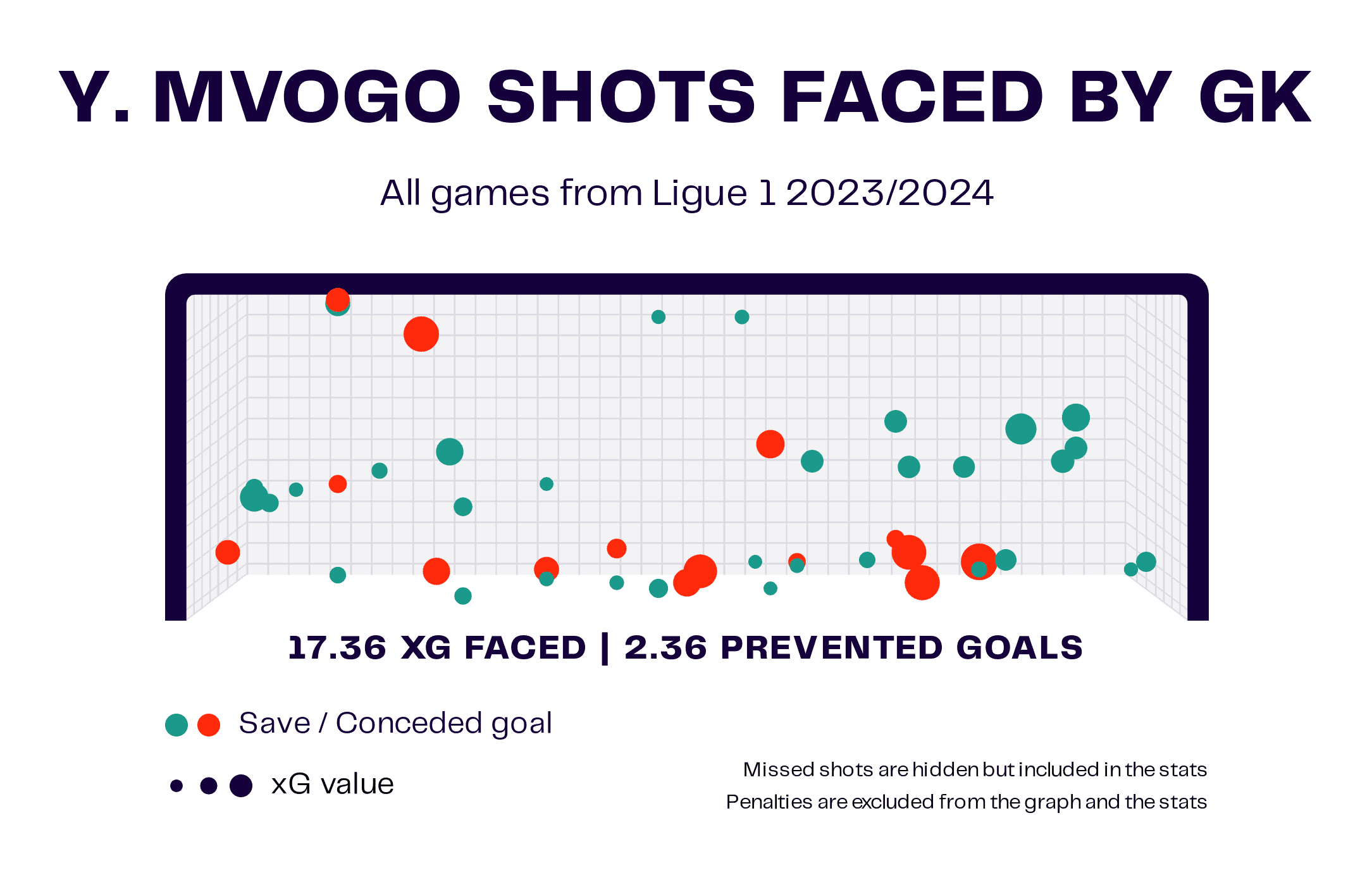

When a team is performing poorly at the back, the goalkeeper will always fall under the microscope and be thoroughly examined. However, needless to say, for anyone who’s been following Lorient closely this term, it’s evident that stopper Yvon Mvogo is far from a problem.

In fact, they’ve got the 29-year-old ex-Swiss Super League star with Young Boys and Bundesliga backup at RB Leipzig to thank for not conceding even more so far this term!

A brilliant example of Mvogo’s shot-stopping was on display late on in his team’s latest Ligue 1 fixture — a 3-3 draw with fellow strugglers Olympique Lyon.

The home side, Lyon, had a glorious opportunity to take the lead in the dying moments of the game, but Mvogo pulled off a stunning stop, demonstrating excellent reactions and composure to keep things level and deny the opponent the late winner.

This is just one example of how Mvogo has proven crucial for Lorient in the 2023/24 campaign — turning our attention to figure 2 below; we can see this wasn’t a one-off.

Based on the 17.36 non-penalty xG he’s faced in 2023/24, the 29-year-old keeper has prevented a total of 2.36 goals in Lorient’s eight league games so far this term. This fairly impressive tally certainly highlights his value and trustworthiness behind Lorient’s backline.

The rest of the team could do a better job of helping him out and exposing him, as we saw in figure 1, less often, however.

Different structure, same principles, less intensity

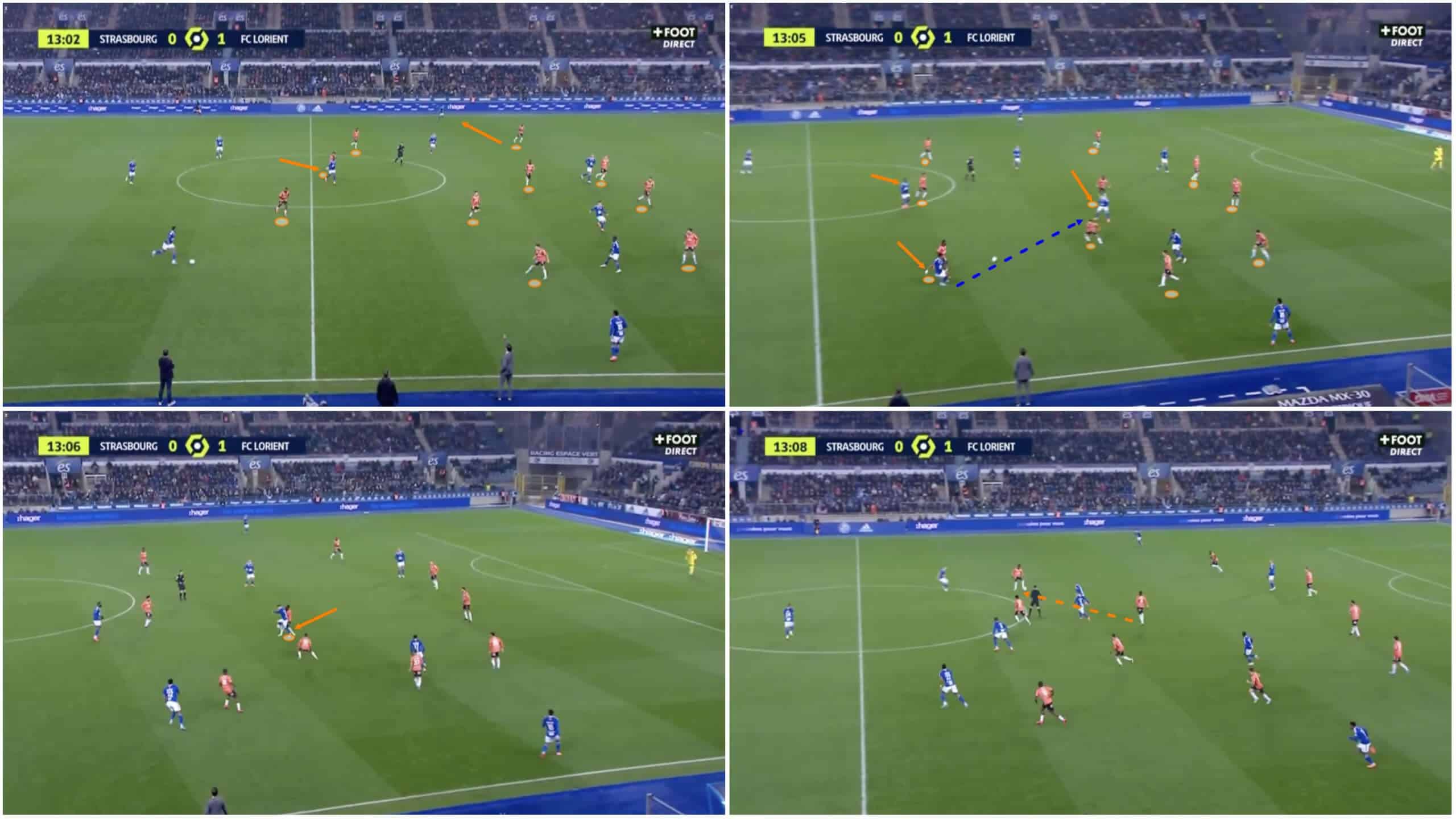

One massive change in Lorient’s tactics this season compared to last is the way in which their team is structured. While they primarily play in a 3-4-2-1 this season, they primarily defended in a 4-4-2/4-4-1-1 shape last term. We see an example of this in figure 3.

Here, they’re set up in a mid-block designed to offer decent coverage across the pitch while also remaining both vertically and horizontally compact, denying even the most eagle-eyed opposition playmaker the opportunity to exploit space between the lines.

Apart from the spacing and positional awareness, a vital part of this defensive strategy on which its success hinges is Lorient’s central midfielders’ physical effort and intensity.

In this case, Bonke Innocent aggressively closes down the receiver and regains possession for his side when the opposition threatens to play through them in midfield.

Lorient have missed the injured Innocent a lot this season. He was absolutely vital in an understated ball-winning role last season, and since he’s been out of action this term, his absence has been strongly felt. Once he returns to action, we can expect a significant upturn in Les Merlus’ performances and results because of his intensity when entering challenges, closing down opponents and his skill with regaining possession.

The Brittany-based side still wish to apply the same principles this season, of course, but are not doing so effectively. Their intensity and physicality looks a lot weaker this term, which is perhaps best illustrated by the fact that their defensive duel success rate has dropped from 61% last season — seventh-highest — to 54.4% this term — the lowest in the league.

This is not ideal for a team that spends plenty of time without the ball and has contested the fifth-most defensive duels (67.36 per 90) in France’s top flight this term.

Take figure 4 as an example. Here, we see how Laurent Abergel is quite easily dribbled past by the attacker, who received with his back to the central midfielder, which allows Montpellier to progress through the centre.

After a long ball over the top creates a 50/50 between the Montpellier striker and Lorient’s right centre-back, Montassar Talbi, the forward Akor Adams completely outmuscles the defender, blowing him to the side and ensuring it was Montpellier again who came out on top of the physical duel, allowing them to create a great goalscoring opportunity.

Le Bris seemingly doesn’t want his side defending very high up the pitch, and that’s fine; you don’t need to do that. However, it’s necessary that when they do enter duels, they enter them with commitment and enough intensity to come out on top of more of these 50/50s because, at the moment, they’re making it too easy for the opponent to bully them and play through them in this way as opposed to any intelligent movement designed to open gaps centrally.

The central gaps haven’t been required as the opponent is comfortable simply outmuscling them. So, working on the intensity with which they enter duels and applying more physical effort should help in situations like we saw in figure 4.

Again, the impending return of Innocent will make a big difference in this regard.

Defensive transitions

Another area of Lorient’s game linked to their lack of intensity and, perhaps, the absence of Bonke Innocent in particular is the transition to defence. Last term, Lorient primarily defended with a 3-2 rest-defence structure that saw two centre-backs and one full-back, along with the midfield duo of Enzo Le Fée and Bonke Innocent, sitting back to help their side prepare for any incoming counterattacks.

These players’ roles were not necessarily to engage the opposition high and counterpress. Rather, they were to try and protect critical areas that the opposition would attempt to access in transition, deny them the opportunity to enter those areas and delay the counterattack for long enough to buy the more advanced players time to get back.

This term, Lorient are without Le Fée (who was sold to Rennes for €20m) and, as mentioned, have been without Innocent so far due to injury. However, they’ve still attempted to defend in this way, achieving less success.

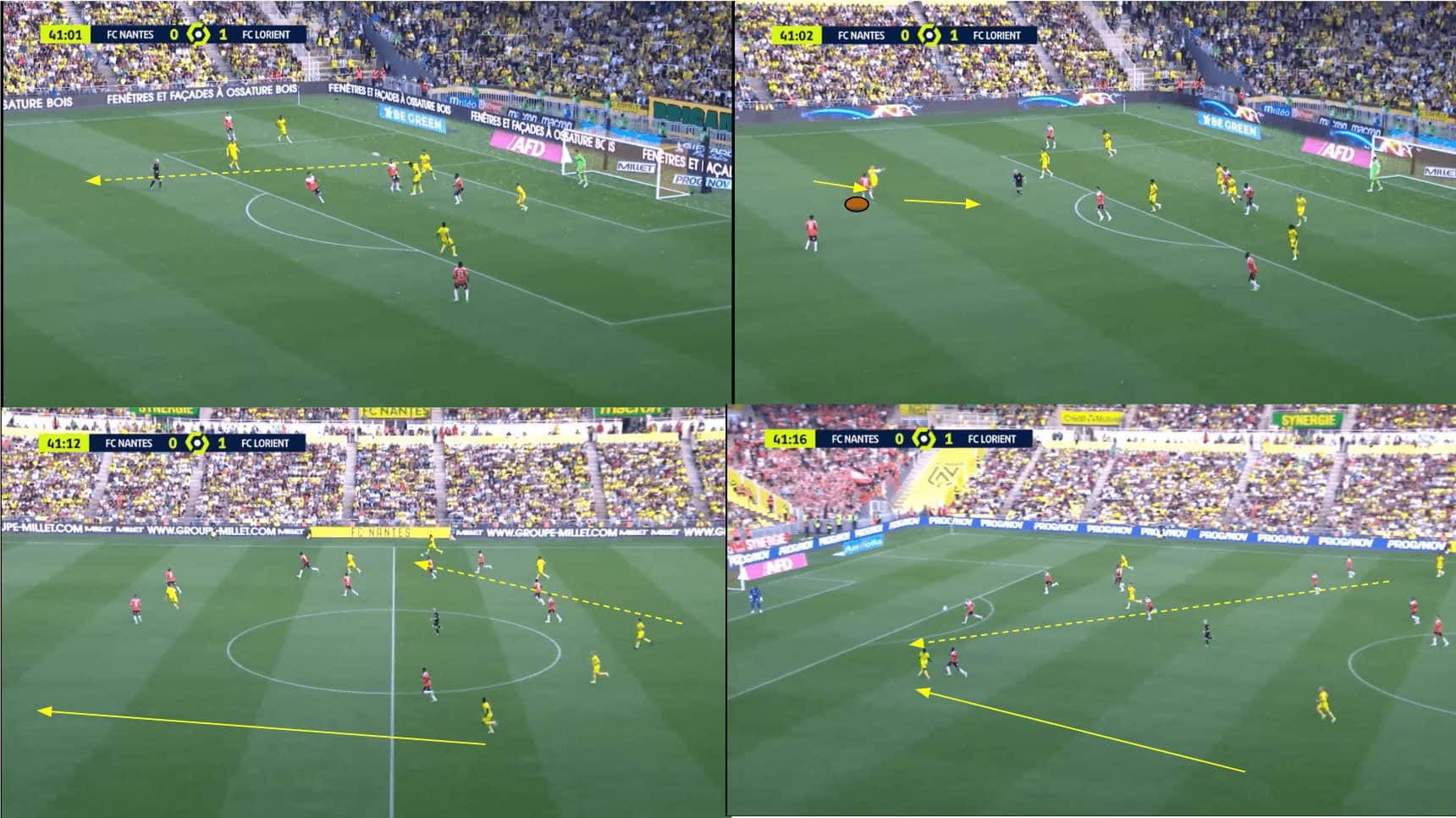

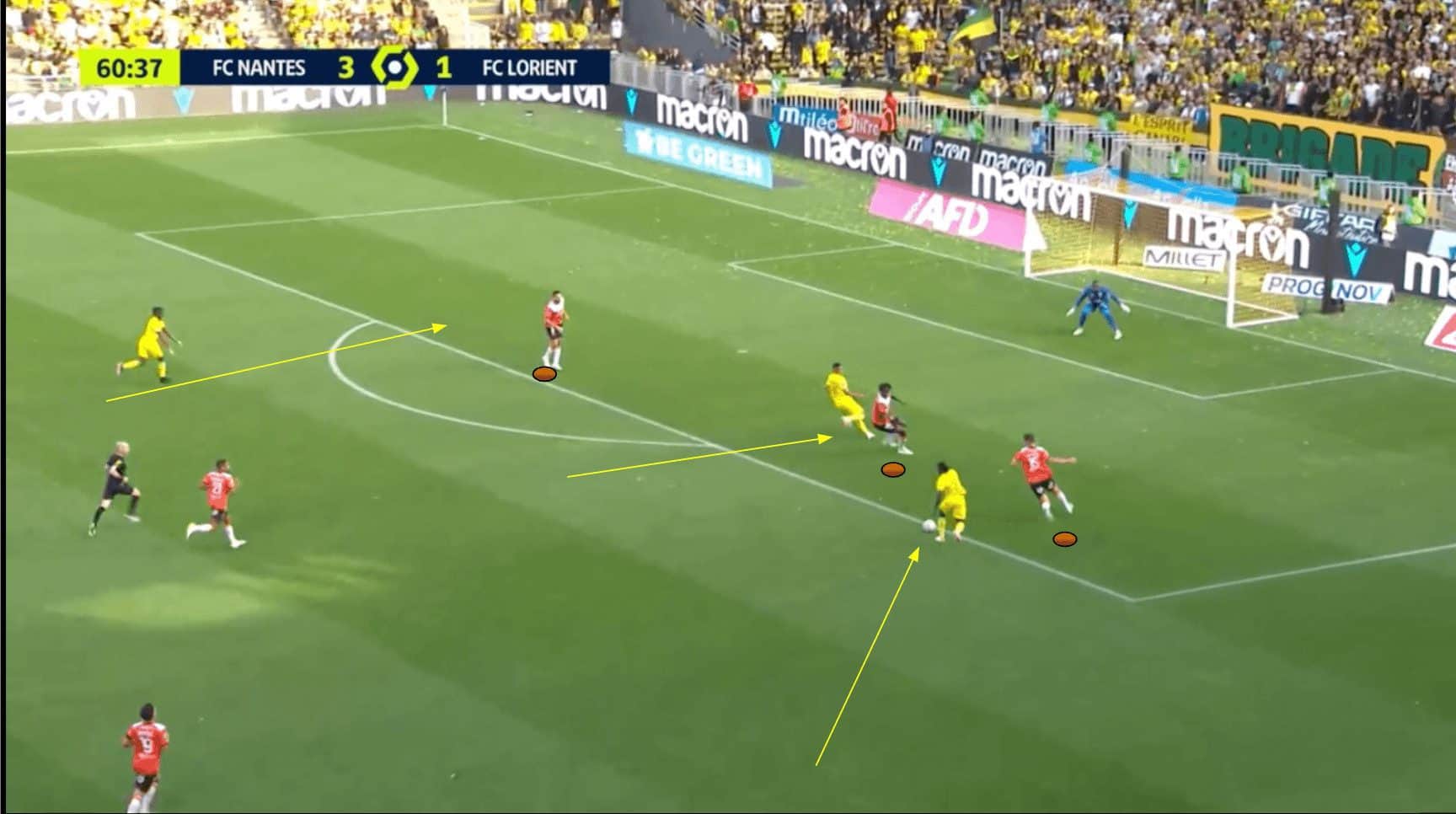

Nantes exploited Lorient several times on the counter in their recent Ligue 1 clash, emphasising problems in Lorient’s transition to defence at the moment in the process.

Looking at figure 5, for example, Nantes head the ball out of the box and, unsurprisingly, the 50/50 duel goes in their favour. From here, they get the ball out to the right wing, behind Lorient’s left wing-back but too far ahead of their left centre-back for him to decide he should move out, especially as he’s occupied by another Nantes attacker at this moment.

From here, Lorient’s wing-backs and other attackers take too long to get back and allow the Nantes wide man too much time on the ball, while on the opposite side of the pitch, Nantes’ left-sided attacker breaks away in behind Lorient’s right wing-back, exhibiting blistering pace and making him an ideal target for this crossfield ball in behind that really puts Lorient’s goal in danger.

This highlights, again, how the lack of intensity from Lorient’s players overall out of possession has been a major issue this term. The left central midfielder probably should’ve gone out to close the ball carrier down here, but the left wing-back should’ve recovered more quickly as well.

Their failure to act decisively on dealing with Nantes’ right-sided attacker led to that player enjoying way too much time and space, thus being able to pick out a teammate’s run with a tremendous crossfield through ball.

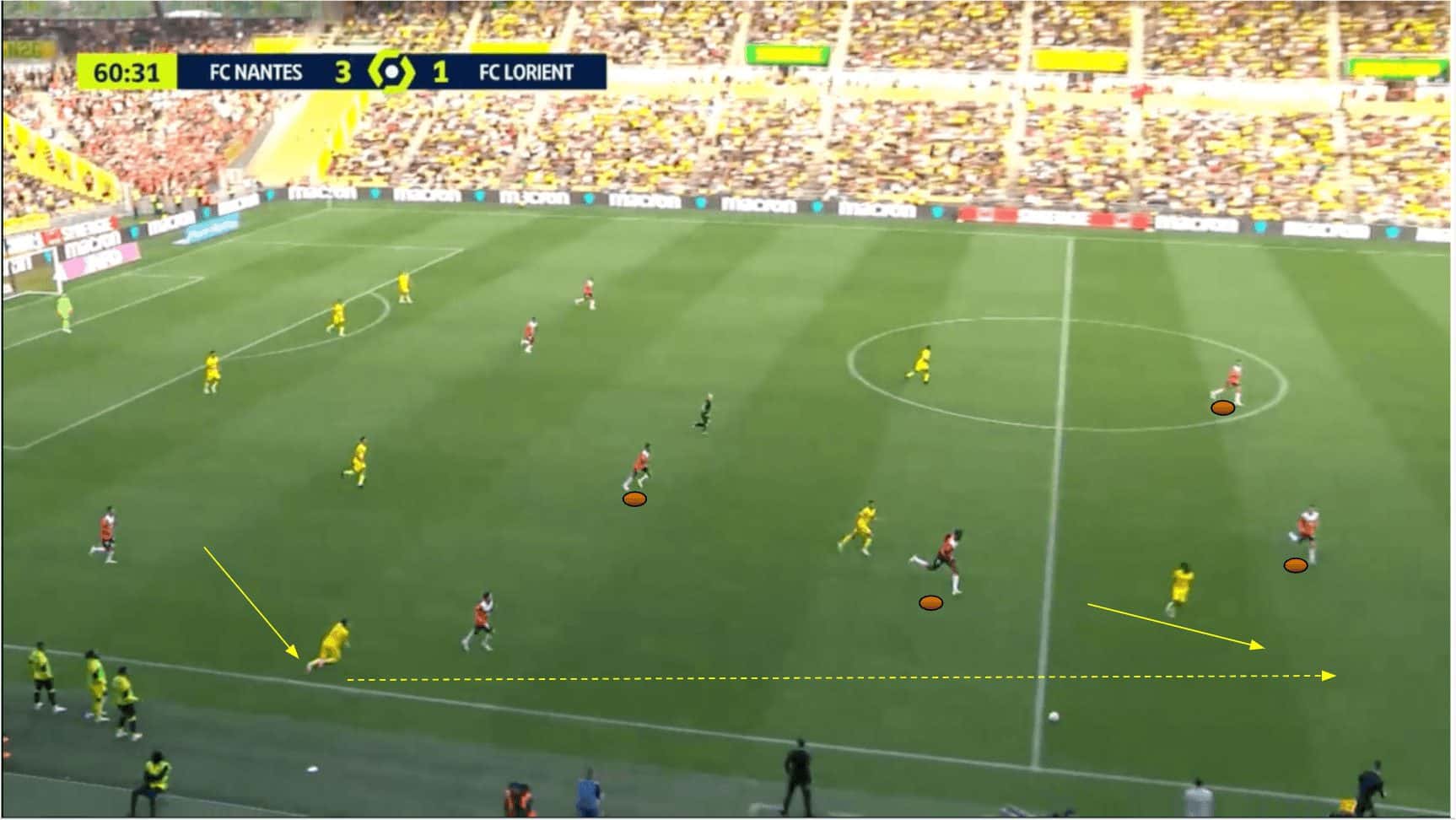

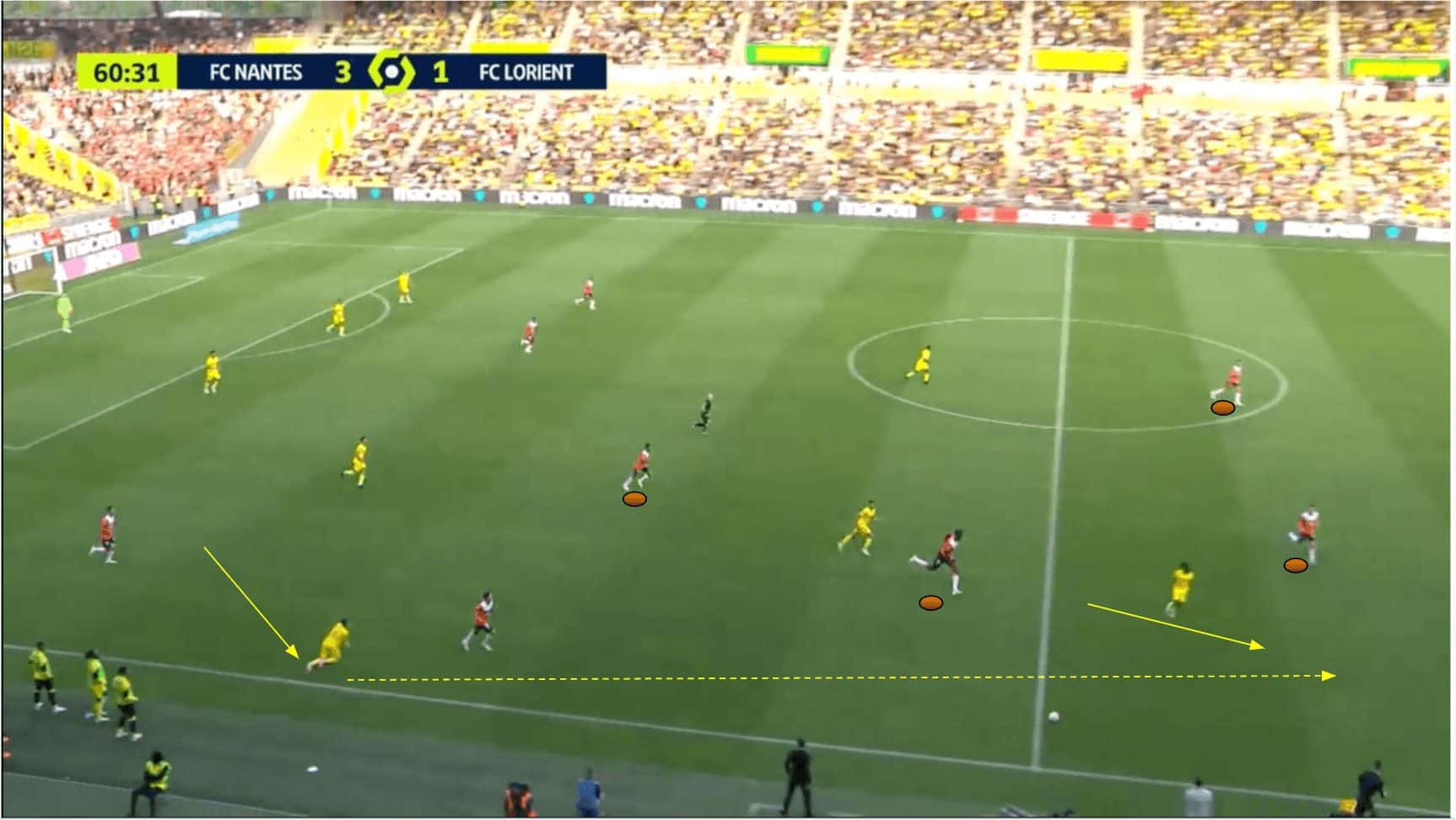

Figures 6-7 show another example from this clash with Nantes that displays how Lorient’s rest defence has sometimes been disorganised, exposing their backline.

In this case, we see a 3-1 structure as Lorient ended up committing more bodies forward while chasing the game in the 60th minute. After Nantes escaped from their backline and got the ball out wide again, they could drive the ball forward to the striker, who made an exquisite run between two of Lorient’s three centre-backs.

This attacker could then carry the ball as far as Lorient’s penalty box relatively unchallenged. At the same time, Nantes generated a 3v3 inside the final third — a very threatening situation for Les Merlus’ goal.

Nantes did a great job of exploiting Lorient’s desperation to get back into the game and punishing them for committing that extra body forward as they approached the later stages of this one.

It’s evident that Lorient has some areas to work on in their defensive transitions, as they have undoubtedly been weaker than they’d like of late in this regard. Again, if players make a greater effort to track back and recover more quickly, this will likely have a positive impact.

Manipulation of the backline

The final issue we’ll touch on in regard to Lorient’s defensive problems is the manipulation of their backline. As mentioned earlier, Lorient play with three centre-backs and two wing-backs this season, while they played with two centre-backs and two full-backs last term.

Their defenders tend to get dragged out of position from the mid-block when the ball is played to an opposition attacker, which then opens up the space behind to be targeted.

We see an example of how Lyon achieved this in figure 8. Lorient’s left centre-back, Isaak Touré, is initially pulled out as Les Gones play the ball into the half-space. The ball is quickly circulated out wide, where Lyon’s right-winger can carry past Lorient’s left wing-back and into the space left open by the aggressive left centre-back previously.

The wing-back likely could’ve anticipated this pass better and certainly performed better in the 1v1 duel with the winger. His failure to do so, along with the left centre-back’s earlier haste to jump out of the backline but inability to prevent the opponent from progressing, left a lot of space for Lyon to target and set up a good goalscoring opportunity that Mvogo, again, had to pull off a decent reflex save to prevent.

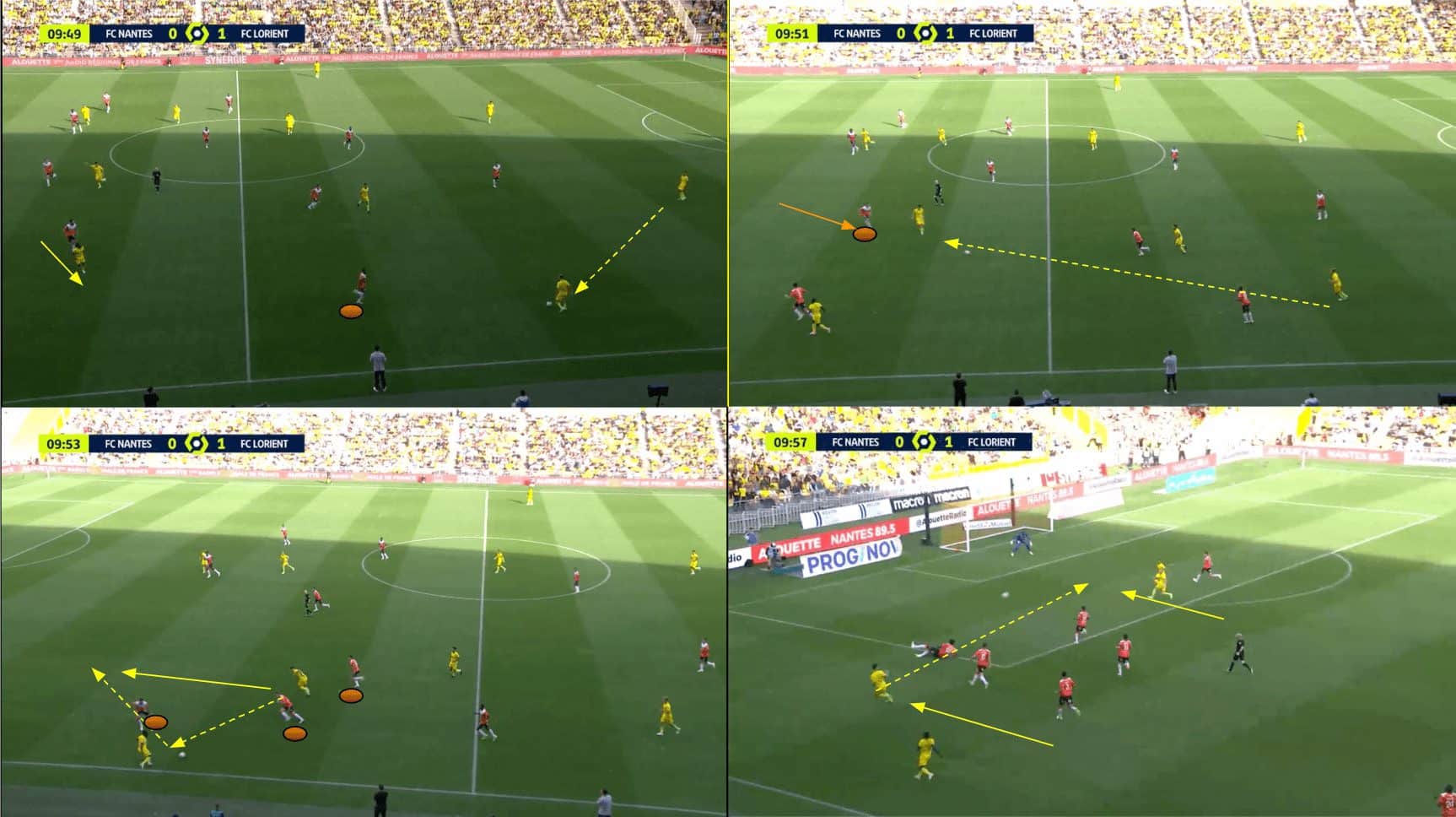

One of the best examples of Lorient’s backline being manipulated this season comes from Nantes once more. On this occasion, Nantes’ left-back picks up the ball deep, dragging Lorient’s right wing-back out to defend against him, forcing the rest of Les Merlus’ backline to shift over into more of a traditional back-four.

This is ineffective as the wing-back doesn’t press aggressively enough to prevent the full-back from finding the left striker dropping off into the half-space, yet again pulling out the centre-back — this time, the central centre-back — but with the run being made at enough of a distance from the defender that he is still able to receive unbothered by the challenge from behind.

After playing a quick one-two with the winger, the attacker is then played in behind the backline.

The bottom-left image in figure 9 highlights three Lorient defenders — the right wing-back (who’d been dragged out to press the opposition’s left-back), the right centre-back (who’d been forced to shift over and cover the winger) and the central centre-back (who’d been dragged out of position by the striker.

We can clearly see how disorganised Lorient’s backline quickly became here due to the players’ inability to defend effectively when dragged out of position by the opponent’s possession play.

Players jump out but not with enough intensity or aggression to actually make a difference to the opposition’s progression. They essentially just create gaps for the other team to try and exploit, as Nantes did on this occasion, creating an excellent goalscoring opportunity from the left wing.

Lorient’s wide centre-backs have been exposed too often this season, making it difficult for them to perform their roles effectively. Furthermore, Talbi has typically defended in a two-centre-back partnership throughout his career. He doesn’t seem as comfortable in a three, where he has to get wider and more aggressive.

This combination of too much exposure and a lack of familiarity with the roles has been devastating for Lorient in the settled defensive phases this term.

Conclusion

Perhaps switching back to a four-defender system would be preferable for Lorient to turn their fortunes around. They attempted this in the second half of a recent clash with Montpellier. They still ended up losing 3-0 but conceded fewer chances in the second half.

Undoubtedly, the return of Innocent to the squad and Tiemoué Bakayoko, who could prove influential, should make a significant difference to their defensive performances. Still, that doesn’t excuse the poor intensity and positioning that we’ve examined in this analysis — this is stuff the current group can improve on and give their team a better chance of moving away from the danger zone even before Innocent and Bakayoko are in the starting XI.

Comments