After joining Olympique Lyon in the summer having previously been manager of Bundesliga sides Bayer Leverkusen and Borussia Dortmund, as well as Eredivisie giants Ajax before that, Peter Bosz hasn’t enjoyed a great start to life at Groupama Stadium. While clearly having a good mind for the game, Bosz’s past managerial posts haven’t always gone well at all. For example, Bosz’s time at Dortmund ended just 15 league games into the 2017/18 season, with a record of six wins, four draws and five losses. At the time of his departure, BVB were on an eight-game winless run in the Bundesliga. Now, at Ligue 1’s winter break, Bosz has guided Lyon to six wins, seven draws and five losses in France’s top-flight so far — a true mixed bag of results — leaving Les Gones sitting in 13th place after 18 games (it should be noted that most other Ligue 1 sides have played 19 games, which does influence Lyon’s standing slightly. However, even assuming Lyon won their game in hand, they’d likely only climb to 10th place.)

A bottom-half finish for Les Gones this term would be their first time finishing in the bottom half of France’s top-flight since 1996 and a real statement about the club’s descent from the dominant heights they reached in the 2000s. Of course, all of the responsibility for this doesn’t lie with the manager alone. Plenty of people have contributed to the results we’re seeing on the pitch for Les Gones this season and a lot of that work had been done even before Bosz’s arrival in the summer. However, you could also argue that now, with the season at the midway point, Bosz is the person most responsible for figuring out a way of ending Lyon’s poor campaign and turning things around. This is a team that made it to the UEFA Champions League semi-final just two seasons ago, remember, and plenty of the quality from that side remains in the current Lyon team.

In this tactical analysis and team-focused scout report, I’ll highlight some issues with what I believe to be the biggest area of concern for Les Gones at present — their susceptibility to leaving their goalkeeper exposed both in later defensive phases and in defensive transitions. While Lyon’s actual goals conceded per 90 (1.35) isn’t disastrously bad, ranking them with the ninth-worst goals per 90 ratio in France’s top-flight, it’s still too many goals going in the wrong end, as it’s equal to their goals scored (26). However, perhaps even more alarming is the fact that Les Gones’ xGA (31.39) is the second-highest xGA of any Ligue 1 side, just 0.14 lower than Lorient, highlighting the level of vulnerability in their defence. They’ve also conceded the third-most shots (12.12 per 90) of any team in France’s top-flight this season, while their xGA per shot (0.134) is the joint-fourth highest xGA per shot in Ligue 1, indicating that they’re not just conceding a high volume of shots but they’re conceding a high volume of high-quality chances.

I hope that this analysis focusing on Bosz’s strategy and tactics shares some useful ideas as to why this has been the case for Les Gones this term, as well as identifying some ways in which Bosz could potentially look to improve his team to fix these problems. All data and stats analysed in this scout report are from Wyscout unless otherwise stated.

Issues with aggressive / 1v1 defending

Lyon have primarily used a 4-2-3-1 this season, with soon-to-be free agent Jason Denayer (982 mins) and ex-Bayern Munich centre-back Jérôme Boateng (1037 mins) being Bosz’s preferred partnership at the heart of defence. Sinaly Diomandé (633 mins), Castello Lukeba (433 mins) and Damien Da Silva (408 mins) are other notable players to have featured at centre-back for Les Gones this term.

In Lyon’s four-at-the-back system, Denayer or Lukeba, the latter of whom is left-footed, have primarily played on the left while Boateng and Da Silva, both of whom are right-footed like Denayer, have primarily played on the right. Diomandé, also right-footed, has been deployed on either side, but slightly more often on the right than on the left. In their last two Ligue 1 games, likely with a view to changing things to end their poor run, Bosz has lined his team up in a three-centre-back shape, with Boateng performing the central centre-back role in both of those games. In Bosz’s three-centre-back system, Boateng acts as the least aggressive defender in the centre — a role that suits him well. They’ve likely chosen to switch to this system because another body in central defence provides an extra layer of protection at the back in case one defender is beaten while finding space around three centre-backs can also be naturally more difficult than finding space around two centre-backs.

Non-aggressive defending from the centre-backs has been a relatively common part of Lyon games this season. Lukeba and Da Silva have engaged in the most defensive duels of any Lyon centre-back, ranking 28th and 29th for defensive duels per 90 among Ligue 1 centre-backs with at least 400 minutes this term — still not an extremely high ranking, but given that Bosz’s side has been one of Ligue 1’s most possession-dominant (58.6% average — the third-most possession in Ligue 1), this may not come as a massive shock and will come somewhat as a result of the system and tactics.

Interestingly, though, Boateng (5.29 per 90), Denayer (3.94 per 90) and Diomandé (3.55 per 90) all engage in a relatively low number of defensive duels among Ligue 1 centre-backs, especially the latter two. Is this a result of preference or system/instructions? Probably a mix of both but I do find it interesting that for such an aggressive side without the ball (Lyon have the third-lowest PPDA — 9.53 — of any Ligue 1 side this term, basically indicating they press with the third-most intensity) in general, both members of their main centre-back partnership aren’t very aggressive and this creates a unique, sometimes negative result on the pitch, which we’ll analyse further later in this section of analysis.

However, all centre-backs must engage in defensive duels at some stage and while Diomandé (72%) and Lukeba (71.88%) have a good defensive duel success rate, Da Silva (63.33%), Boateng (60.66%) and Denayer (60.47%) have very low defensive duel success rates compared to other Ligue 1 centre-backs with 400 minutes or more. Again, we see Lyon’s main centre-back partnership popping up in a negative light here. From this, we can say that Lyon’s main two centre-backs 1. Don’t engage in many defensive duels and 2. Tend to fare relatively poorly in the defensive duels they do contest.

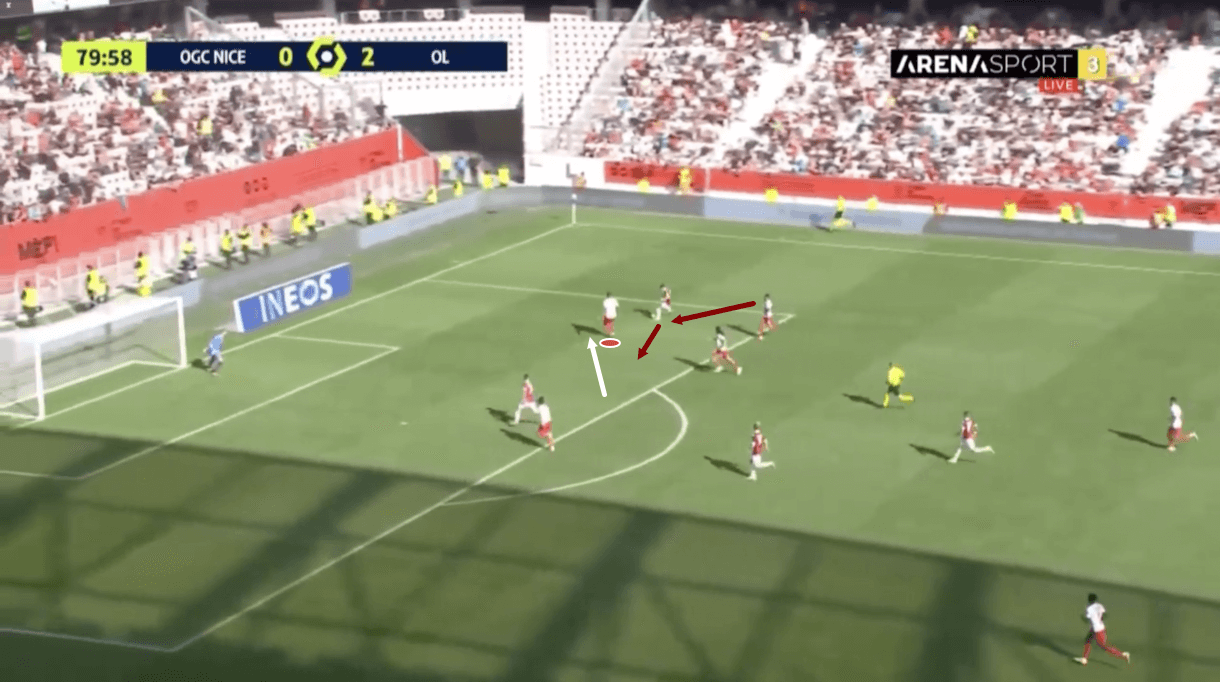

Both Boateng and Denayer are experienced centre-backs, with the former having won just about everything there is to win in the game, but I think part of the explanation for their poor performance in defensive duels and, ultimately, Lyon’s poor defensive record, lies with their defensive technique in situations when they’re forced to defend aggressively. Take figure 1, for example. Here, the opposition have progressed down Lyon’s left wing behind the full-back and into the box, drawing Boateng on this occasion into a 1v1 as left centre-back Denayer was slightly higher, having been beaten earlier in the move.

As the German centre-back approaches, he leaves a lot of space open on the inside for the dribbler to cut into while moving away from the centre of the box, as opposed to backing into it and giving himself a better chance of turning when the attacker makes a move. As this passage of play progresses, we see the attacker burst past Boateng into the centre of the box by exploiting the centre-back’s less-than-helpful movement and body positioning.

There have been several occasions this season when both Boateng and Denayer have been sold far too easily by opposition attackers in the way we see with Boateng here, with the centre-back overcommitting to defending one particular side and then leaving the other side open to be exploited. However, this is also an example of Lyon leaving the centre-back exposed and in a position to make a mistake that leaves him exploited like this one. Why was the right centre-back dragged into a 1v1 on the left side of his box here? Because the full-back and left centre-back were played through with a great pass that exploited space behind them earlier in the move. Why was the pass played? Because there wasn’t enough pressure on the passer and the runner was given too much space and freedom to move into it. No individual is solely to blame, it’s a combination of things that have led to Lyon’s struggles at the back in aggressive defending situations this term, like the example we see above.

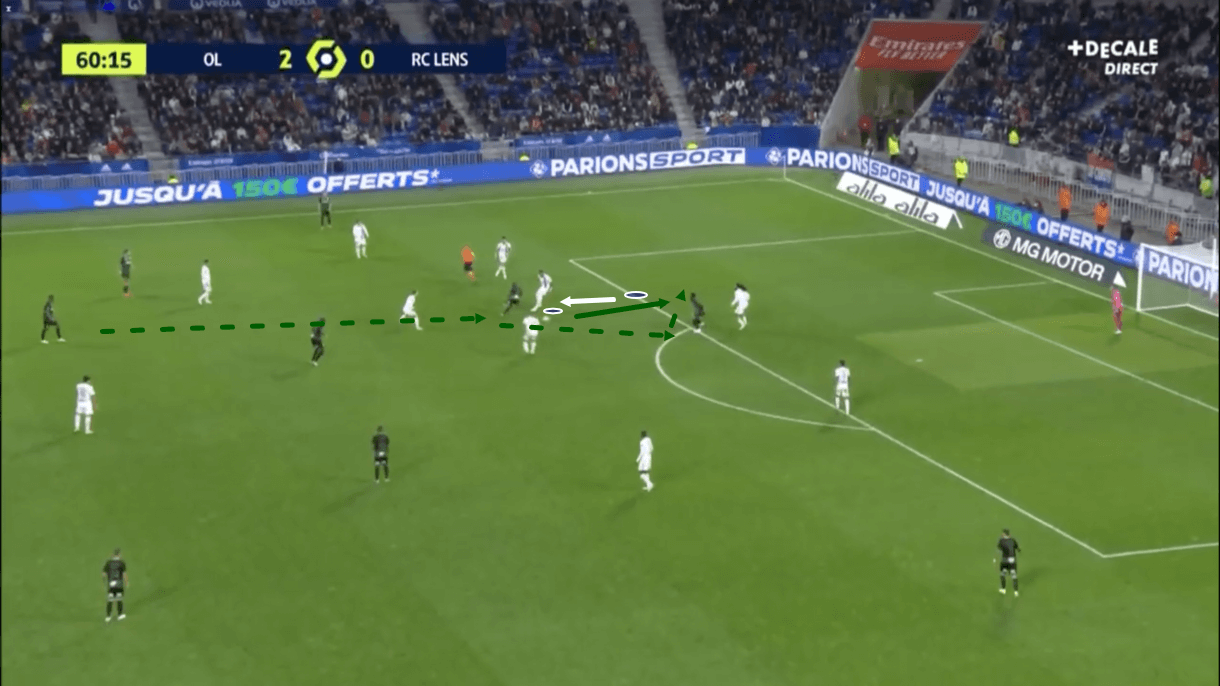

Another potential criticism of Lyon’s centre-backs has been their tendency to not get tight enough to attackers when forced to defend aggressively as they receive the ball behind the midfield line. We see an example of one such situation in figure 2. Here, Lens’ left-forward has just received a pass in between the lines, dragging right centre-back Boateng out from the backline. However, despite his movement, the centre-back isn’t tight enough to prevent the attacker from turning on receiving the ball, leading to the attacker being able to link up with his right-forward teammate, play a one-two around Boateng and progress into the box.

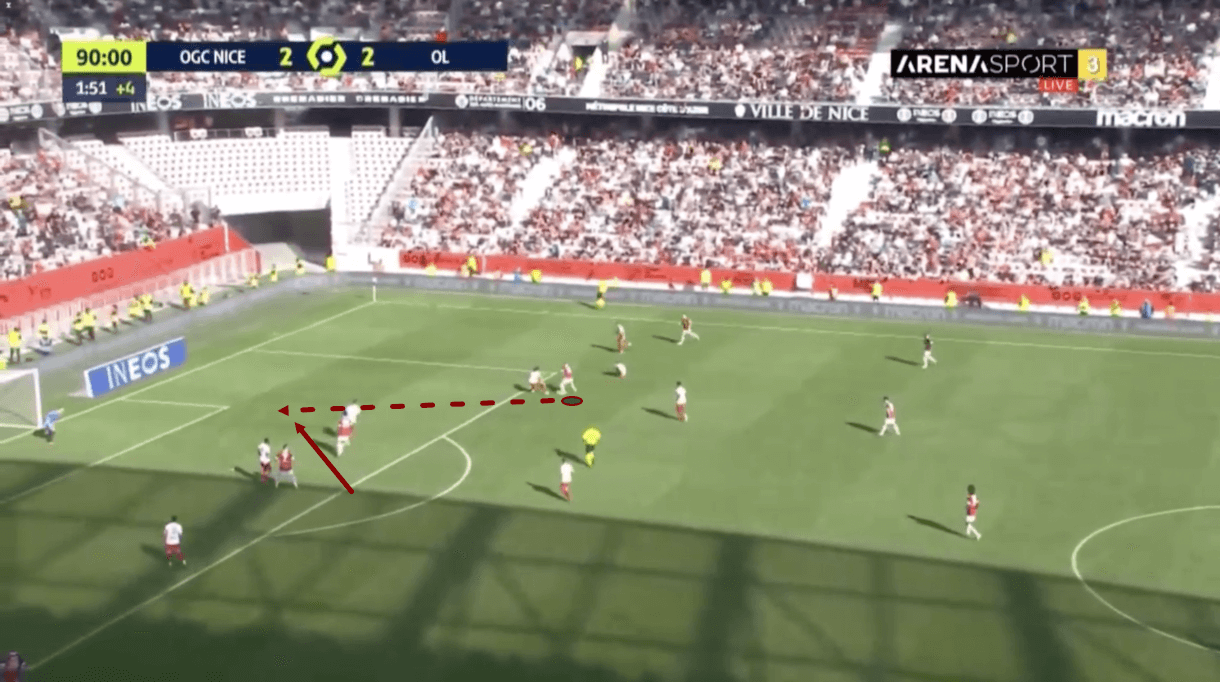

We see an example of a similar situation in figures 3-4, this time with Denayer instead of Boateng. In figure 3, we see the opposition sending the ball from the right-wing into an attacker’s path as he moves to exploit space in front of Denayer and behind Lyon’s midfield line.

As play progresses into figure 4, we see that while Denayer moved out of the backline to confront the attacker, again, he wasn’t tight enough to prevent him from turning and that leads to the scene we see in figure 4, where the attacker is facing Denayer with space behind him and another attacker running into that space where he can receive the through pass in the box to create a goalscoring opportunity that they ultimately take, turning this game from 2-2 to 3-2 very late on.

This highlights the issue for both centre-backs of failing to get tight enough to attackers when they receive between the lines, allowing them to 1. Turn and 2. Enjoy enough time to decide on their next action and execute successfully to progress into a very threatening position. Again, these centre-backs don’t prefer to defend aggressively and the situations into which they’ve been dragged aren’t ideal for them, but I think they still could’ve been handled better than they were.

Figure 5 shows another example of an opposition attacker receiving the ball in between the lines, but this time with Lyon in a mid-block rather than a low-block, which is how we saw them defending in each of the other examples so far. We see a better example of what I perceive to be Bosz’s intentions for Lyon’s centre-backs in this example. As the attacker receives between the lines, Les Gones’ defence backs off, rather than comes out to defend aggressively which we know they don’t typically like to do. Here, we see Diomandé in place of Boateng, but the intent remains the same — protect the space behind. The idea here is for the centre-backs to remain organised with a side-on body shape, ready to react to either the dribbler getting close enough to make a defensive action on something like a heavy touch, or react to the ball being played in behind, which we see them executing well in this example. Meanwhile, the onus is on the midfielders to get back quickly and diligently to apply pressure on the attackers from behind.

The most important thing here is that the attacker doesn’t enjoy lots of time and space in between the lines in a dangerous position to make their next decision and execute it. However, in this example and as has been the case in many of Lyon’s games this season, the attacker was afforded that luxury of time and space between the lines, which they used to punish Les Gones.

As this example moves on into figure 6, we see that the attacker who’d received between the lines has now laid the ball off to a wide player, who also has lots of time and space in a dangerous position to get his head up before executing his next move, which ends up being a well-delivered floated cross that drops just behind Denayer for the attacker we see just outside of the box here to send into the net with a powerful header. By the time the nearest midfielder had gotten back into position, the central attacker had already turned and laid the ball off out wide to a player who was already facing forward and had lots and time and space of his own to make a decision. This highlights the issue of Lyon’s tactics — if the defenders aren’t going to come out, the midfielders have to get back. The attacker can’t be afforded so much time and space between the lines, as if they are, then the result is figure 6 and its aftermath — a goal conceded.

Similar to figures 3-4, this last passage of play resulted in a late goal being conceded and that’s been fairly common for Lyon. Whether it’s a concentration issue or an energy issue or a motivation issue or something else, these defensive problems we’ve seen on the pitch have come more often during later parts of a game, which isn’t an ideal habit to be getting into and something Bosz needs to assess.

Defensive transitions

Defensive transitions are often an area of concern for possession-dominant sides, and this is an area in which Lyon have found some difficulty this term. They’ve conceded a relatively high number of counterattacks per 90 for a Ligue 1 side this term (3.25 per 90) and a relatively high percentage of those counterattacks (43.1%) have resulted in a shot. So, why are Lyon conceding so many shots from counterattacks?

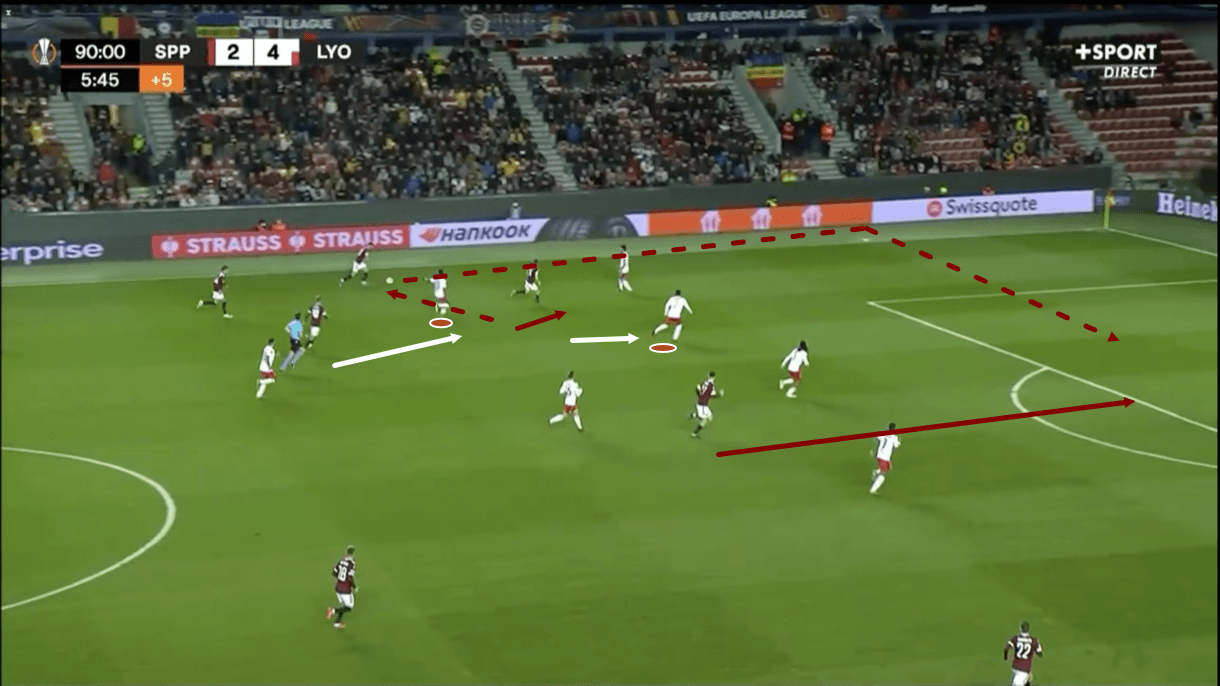

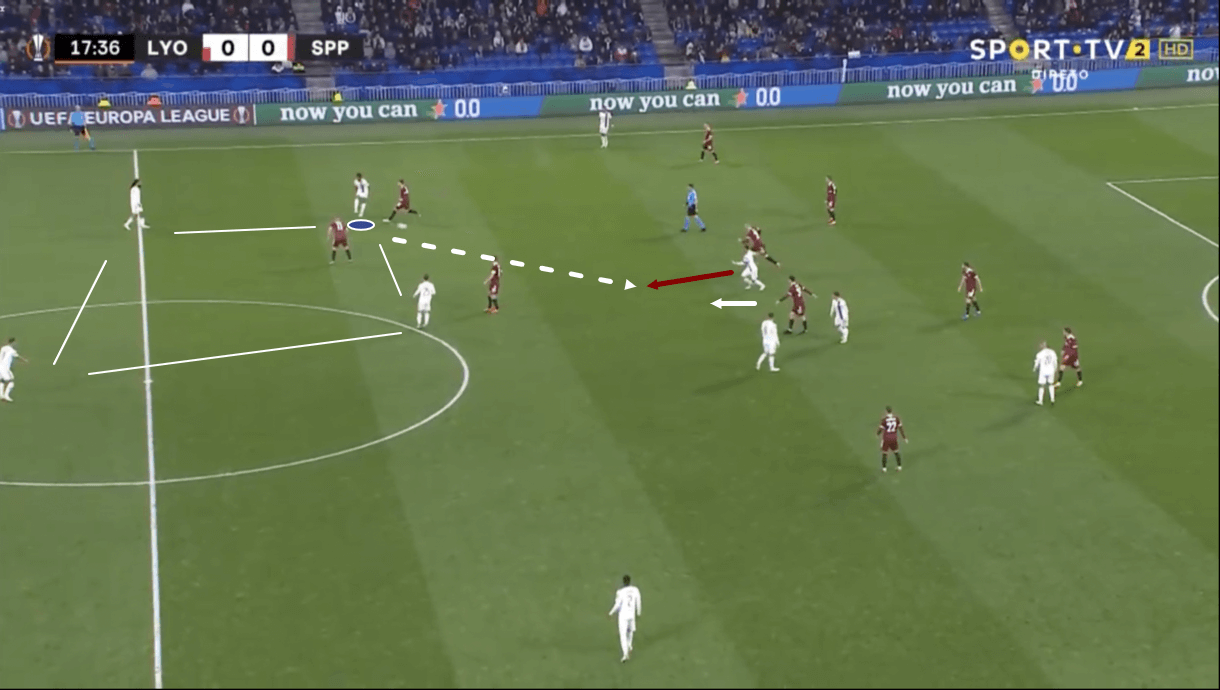

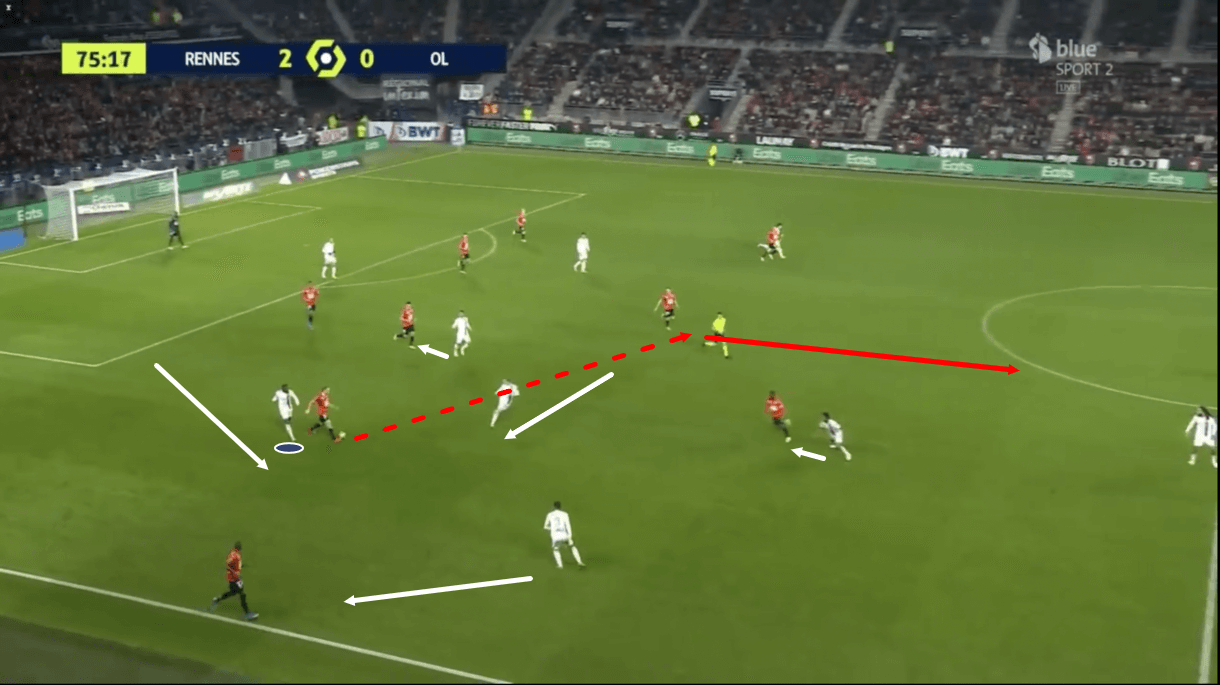

Part of the explanation for this, again, is Bosz’s reliance on players to apply pressure from behind, chasing down attackers who have already progressed beyond them initially, which figures 7-8 will highlight. Firstly, figure 7 shows an example of a counter-attacking situation starting for Rennes versus Lyon, with Rennes having just regained possession on the edge of their own box.

At this moment, Lyon’s general counter-pressing structure isn’t bad. As I’ve marked on the image, players are generally well-positioned to control the immediate passing options, making life more difficult for the ball carrier. However, when counter-pressing, the team transitioning to defence has a limited amount of time to win the ball back before they lose control of those passing options, with runs being made beyond them and more teammates moving upfield to offer support. As a result, pressure on the ball carrier is also crucial in these moments immediately after losing possession — not just pressure on the ball carrier and not just pressure on the options, but both working together to stop the counter and win the ball back.

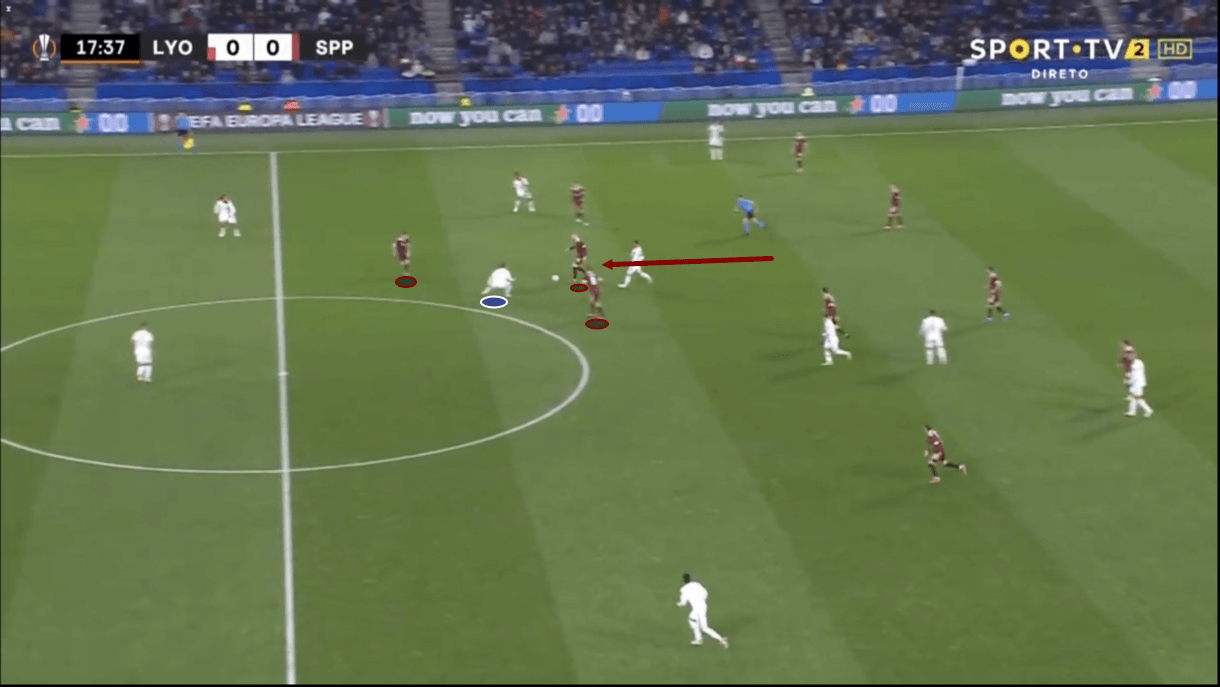

The player tasked with pressing the ball carrier in this example was Lyon’s left-sided attacker, Karl Toko Ekambi. As this passage of play progressed into figure 8, we see that Toko Ekambi did get back to the ball carrier in time but when he arrived at the player, he failed to do anything conducive to actually stopping the counter-attack/regaining possession. His presence alone wasn’t enough to stop the attack and when he arrived at the ball carrier, he more or less just slowed down. This led to Lyon’s right central midfielder, Maxence Caqueret, being dragged over to press the ball carrier but as he did so, he allowed another Rennes player to become free in the centre as a passing option which the ball carrier took, allowing Rennes to break away through the centre of the pitch, from where they ultimately progressed into the opposition’s half.

On arriving at the ball carrier, Toko Ekambi could’ve positioned himself on the other side of the attacker to block the passing lanes into midfield, could’ve made a tackle to either win the ball back clearly or could’ve even just fouled the opposition attacker to prevent the counter-attack from continuing. Instead, he went behind the attacker which led to Caqueret being moved out of position and Rennes progressing through midfield. Again, things like this are never down to just one person but a combination of things. However, this passage of play provides another clear example of how Bosz relies on his players to apply pressure well from behind and what the consequences of not performing this task well enough are and have been for Les Gones throughout the season.

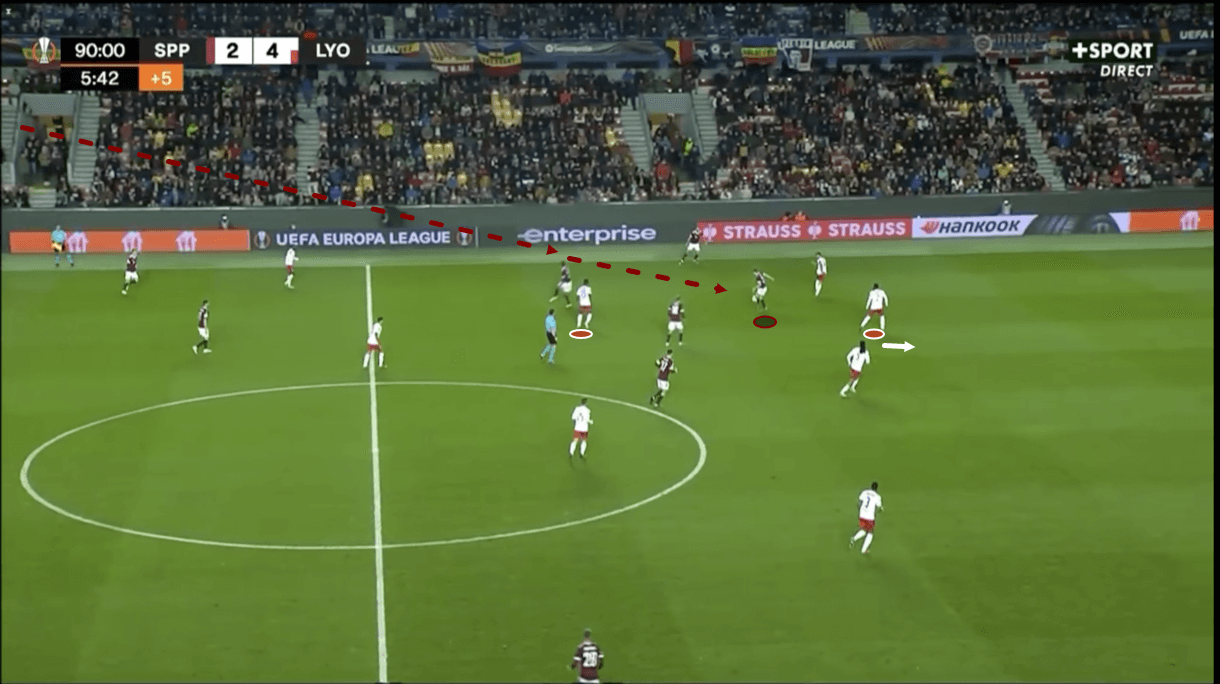

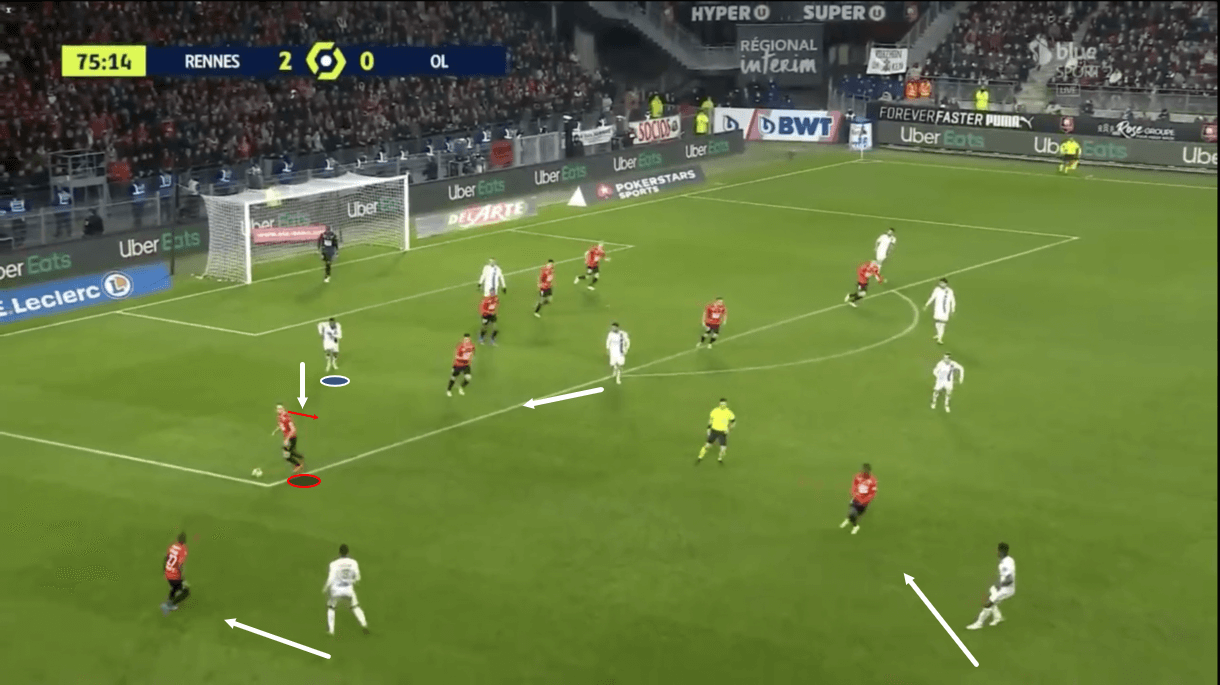

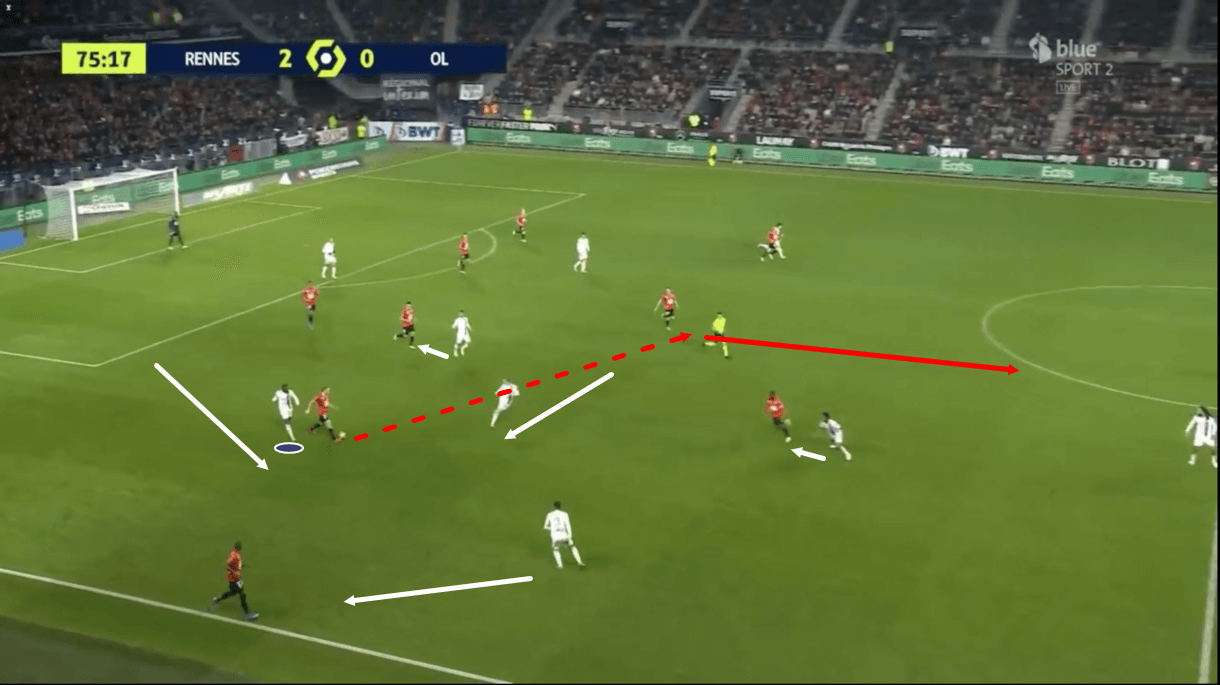

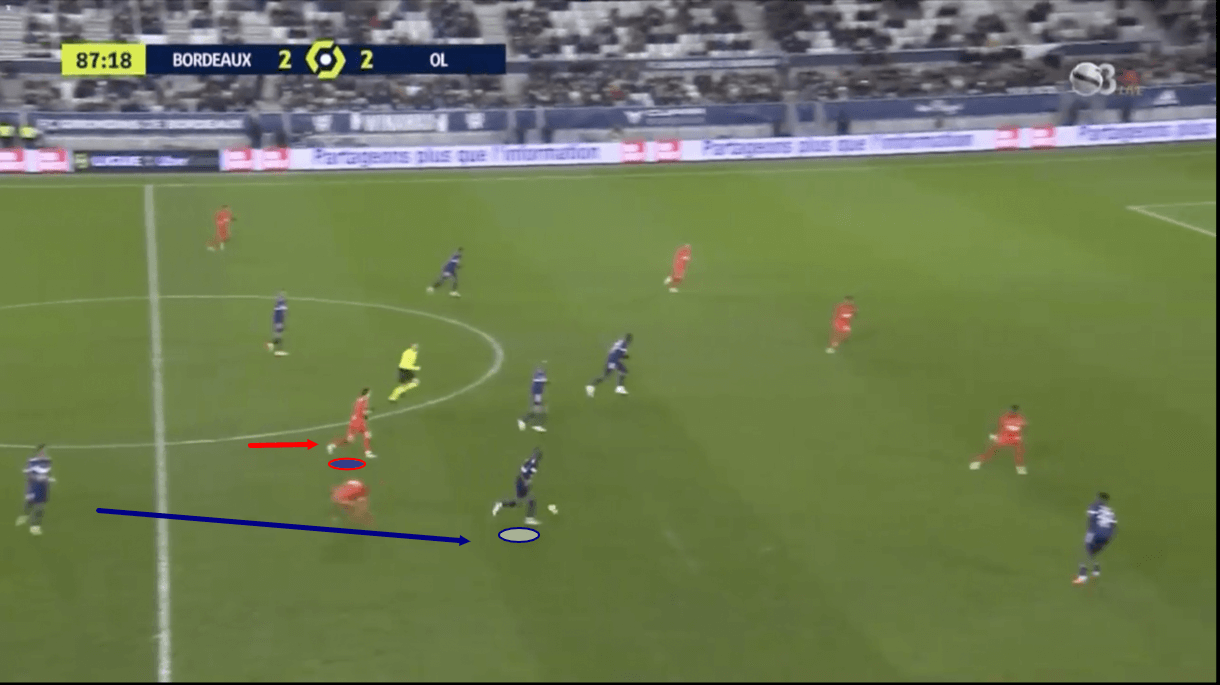

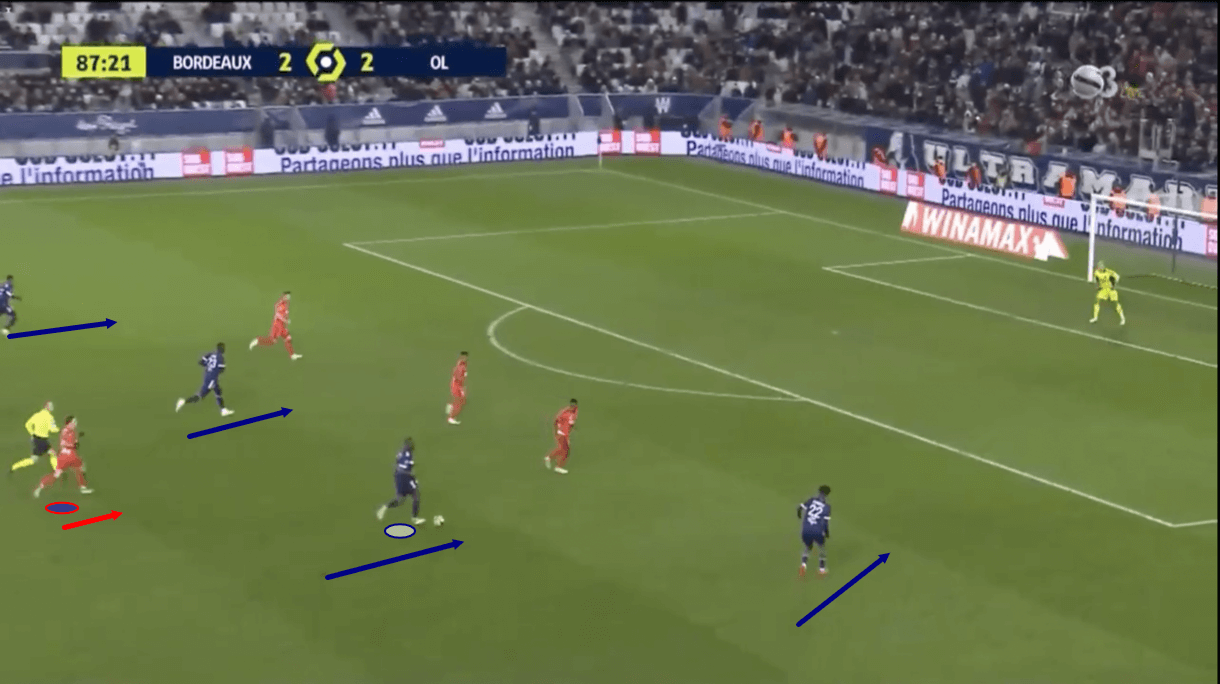

Figures 9-10 show another example of Lyon in defensive transition, this time after having just lost the ball in midfield rather than further upfield. This time, we get a closer look at how Les Gones’ backline — this time in a back-three — operate in defensive transition. As explained earlier when looking at their behaviour in the mid-block, Lyon’s backline is typically tasked with protecting space behind rather than defending aggressively in or around the area of the pitch in which we see them here, and that is also the case in defensive transitions here, as we see in this example.

As the Bordeaux ball carrier progressed upfield, however, we see in figure 10 that Bordeaux have created a 4v3 overload against Lyon’s backline, while one midfielder is tracking back to chase the ball carrier, but isn’t getting there quickly enough. In real-time, I think it’d be fair enough to say the midfielder isn’t exactly sprinting back — whether that’s a problem of fatigue late on in the game so he needs more protection from his teammates, coach and/or system, motivation, confidence or work rate is another issue, but it’s certainly a problem for Bosz if you’re relying on forwards to get back and close down players running at midfield in transition or midfielders to get back and close down players running at the backline in transition, and they simply aren’t doing it quickly enough to make the required difference.

Again, look at the clock, it’s late in the game here which, as discussed earlier, is a common time to catch Lyon making defensive mistakes or ending up in negative situations like this one. On this occasion, the opposition fail to score but they succeed in creating another dangerous situation for Lyon’s defence and goalkeeper.

As mentioned earlier in this analysis, while Lyon have conceded 26 goals, their xGA is 31.39, which is way more than their actual goals conceded and is the second-worst xGA of any Ligue 1 side. This is partly an indicator of luck and also an indicator of goalkeeper Anthony Lopes’ quality between the sticks. Per Statsbomb via FBRef, Lopes has made more saves (69) than any other Ligue 1 goalkeeper this season, with the next-highest 10 behind Lopes. Additionally, Lyon’s post-shot xGA minus goals allowed (+2.1) is the second-highest of any goalkeeper in Ligue 1, with fellow Lyon ‘keeper Julian Pollersbeck also boasting a positive (+0.4) post-shot xGA minus goals allowed. Post-shot xG is useful for analysing goalkeepers’ performances because per Statsbomb: “post-shot xG uses information after the shot has been taken up until the shot were to pass the goalkeeper”. If you have a positive result after taking actual goals allowed away from post-shot xG, it either indicates good luck or above-average shot-stopping and with Lopes boasting the second-highest post-shot xG minus goals allowed in Ligue 1, we can see that his performance has been crucial for Lyon this season.

These post-shot xG minus goals allowed numbers, Lyon’s xGA and shots against all point to 1. Lyon leaving their goalkeeper quite vulnerable at times this season and 2. The goalkeeper bailing Lyon out quite a lot this season. I think this is worrying for Lyon because they’re already having a poor season by their standards and if not for a combination of luck and great shot-stopping, they’d be a whole lot worse off still, which doesn’t paint their defensive system and individual defensive performances in a good light.

Ball losses

For the final section of this tactical analysis, I’ll touch on Lyon’s ball losses. Again, as a possession-dominant side, guarding against giving lots of turnovers is very important, and in general, Lyon are good at doing this. They’ve got the third-best pass accuracy (87.7%) and sixth-lowest ball losses (88.86 per 90) in Ligue 1. However, guarding against giving easy turnovers in dangerous areas is also important and while there are plenty of Ligue 1 sides conceding possession more than Lyon, Les Gones have given the ball away cheaply in dangerous areas this term. They have a habit of allowing this to occur in the progression phase when playing either a lateral pass or a forward pass at least more often than I think they’d be comfortable for this to occur.

As mentioned earlier in this analysis, their shape in counter-pressing is generally fine but when they lose the ball cheaply in a dangerous position in the progression phase, they inevitably leave themselves vulnerable to being successfully countered because they’ll have many if not most of their players in front of the ball in that instance, giving the opposition a lot of space to attack.

In their 4-2-3-1 shape, Lyon tend to build with a 2-2 base structure. One full-back — the ball-near one if applicable — gets wide on the touchline with the other tucking in slightly to add some central protection and offer another central short passing option. The centre-forward leads the line with the three supporting attackers occupying space behind him in either the typical, central ‘10’ position or the half-spaces. We see an example of this offensive shape in figure 11.

Here, however, as left central midfielder Thiago Mendes looks to play the ball forward to one of the attacking midfielders while under pressure, an opposition midfielder springs into action to cut the passing lane and immediately setting up a counter-attack for his team.

As play moves on into figure 12, we see that the interception was successful and the opposition were immediately able to set up a 3v1 on Lyon’s right central midfielder. In overloading the right central midfielder in this small area, the opposition were able to progress past Lyon’s midfield very quickly before going on to overload Les Gones’ backline. This passage of play highlights just how quickly Lyon can go from the progression phase to a very vulnerable defensive position as a result of a loose ball in midfield. This will inevitably happen at some point, but I think turnovers like this are happening far too frequently for Lyon this season and they’ve been punished by this on a couple of occasions, so this is an area for Bosz to focus his efforts on the training ground to improve Lyon’s possession play as well as their capability in defensive transitions for when moments like this do occur.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis and scout report, I think Lyon’s biggest issues this season have been in their defending in the mid-block, low-block and defensive transitions. Their centre-backs can improve when they’re forced to defend aggressively, while the team can improve to minimise the number of times the centre-backs are forced to defend aggressively. Meanwhile, Lyon’s more advanced players (midfielders and forwards, where required) must improve their defending when needed to track back and close down ball carriers behind them. These are the two main issues for me, with ball losses being a third area for Bosz to focus on in the future.

Comments