Machida Zelvia have only been in the J League pyramid for a little over 10 years. In the last decade, the team has mainly stayed in the J2 league, moving up from the J3. However, since manager Go Koruda arrived in 2023, the club has been able to play at an entirely different level. Before Koruda left his 28-year role as a high school football coach, the team finished in 15th. In Koruda’s first-ever professional role as a manager, he was able to elevate the side by guiding the team to the top of the league, achieving promotion to the J1 for the first time in the club’s history. In the current season, over halfway into the campaign, the newcomers are at the top of the J1 with the form and performances of a side worthy of winning the league.

The team does have some high-profile players, with Mitchell Duke being a physical presence off the bench, with his abilities on display during the most recent FIFA World Cup. Another forward, Erik, has won the J1 league before, while playing under current Spurs boss Ange Postecoglou. Their main striker, Shota Fuijo, will be aiming to lead the line for Japan at the upcoming Olympics, while teammate Yu Hirakawa has just left to join Bristol City in the Championship. It is no coincidence these high-quality players are all attracted to Machida Zelvia and the project at the club.

Set pieces have played a key role in the club’s ascent to the top of the league table, with 13 of 36 goals coming from set plays and a further two set play goals being scored in cup games. Interestingly, seven of these league set-play goals have come from throw-in situations, meaning 19% of their league goals are a result of throw-ins. Machida Zelvia are different from most teams I’ve analysed, where their success doesn’t come due to their ability to make the first contact. Due to their weakness in being able to win the first contact and deliver precise balls into crowded areas, Machida have had to improvise, and most success has come through either short corners or second-phase situations.

In this tactical analysis, we will delve into the tactics used by Machida Zelvia during attacking set plays, with an analysis of some of the many corner routines they have used to gain the edge. This set-piece analysis will look at the different attacking methods they’ve used to remain unpredictable when using both corner kicks and throw-ins and why their strong counter-press has been key to any success despite a lack of chances coming from the first contact after a set-piece.

Short Corner Patterns

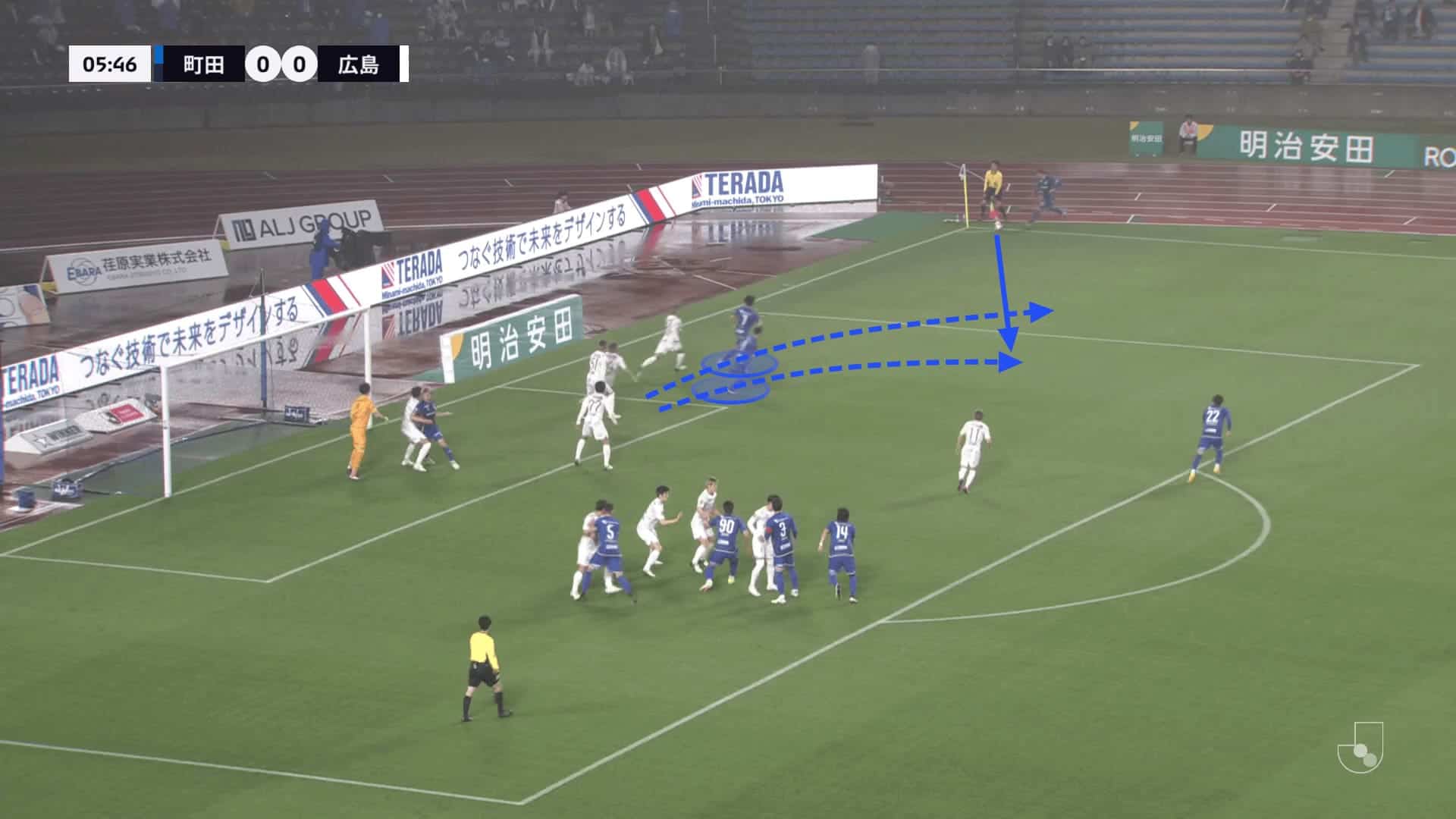

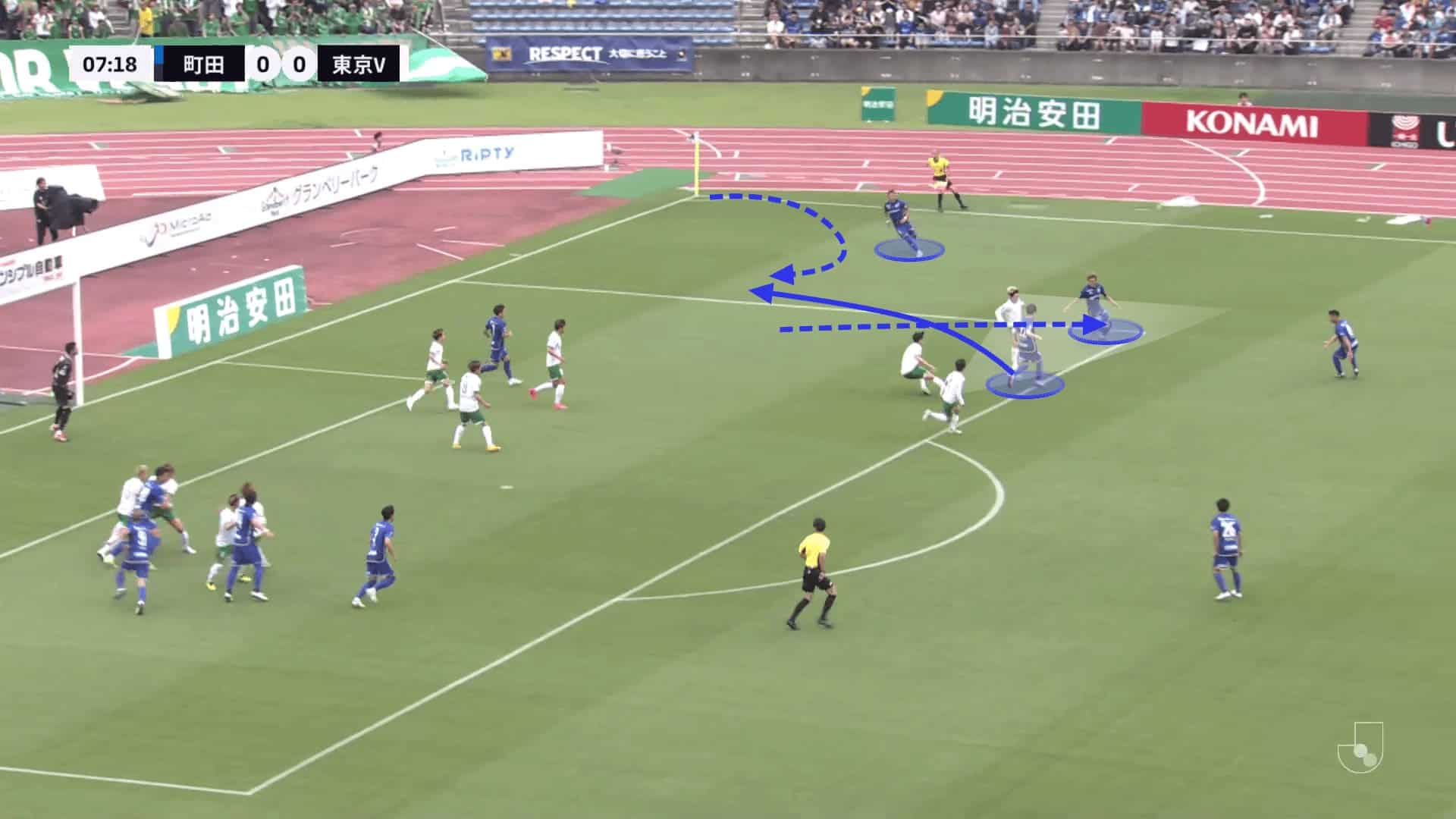

Most of Machida’s short corners start with the receivers starting in the six-yard box, where the two players then sprint away from the box towards the ball, with multiple benefits coming as a result. Firstly, arriving in the space at the edge of the box, increases the time and space the player receiving the short pass and his teammates have on the ball, as the opposing team is not expecting the corner to be played short. Defending sides usually have one or two assigned players to step up from position to close down short corners, but with two players coming to receive the short corner and the taker getting involved in play after, this gives the attacking side the numerical overload.

Furthermore, with the defenders moving at speed to track the supporting runs toward the ball, they are vulnerable to quick changes of direction, meaning it’s hard to react and recover the space behind their backs if the ball is played in behind them.

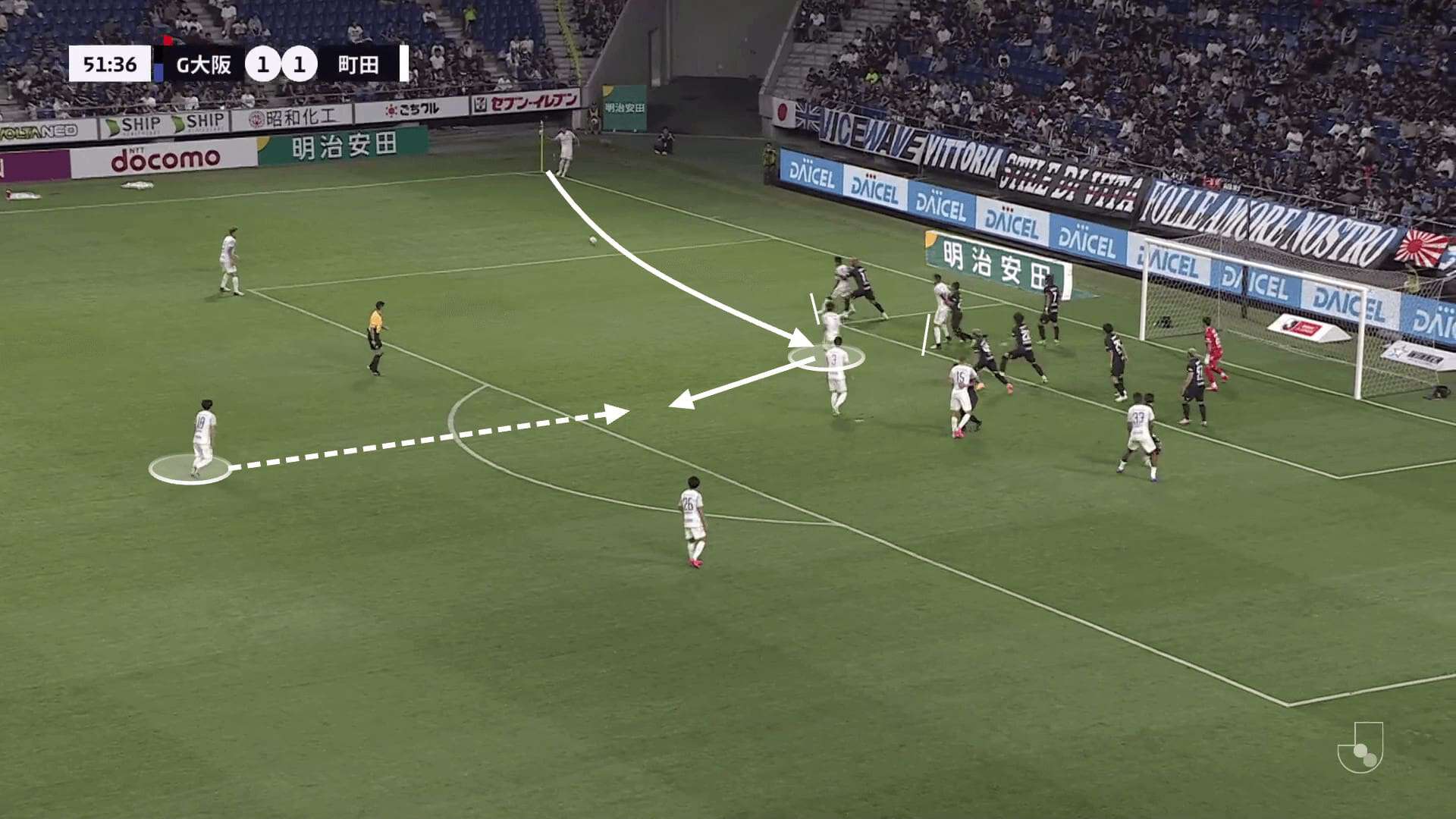

As we see in the examples above and below, the ball is played to the furthest player, which gives the defender tracking the nearer player a problem. When the near player allows the ball to go through his legs and to the further player’s feet in the image below, that defender is suddenly in a position where he is no longer goalside, and suddenly the attacker is out of his sight. In that moment, the near attacker is able to quickly change direction and attack the space they have just arrived from, at the byline to cross the ball into the box. The player on the ball is facing away from the goal, enticing pressure from the defenders, but uses a reverse pass to access the space behind both defenders.

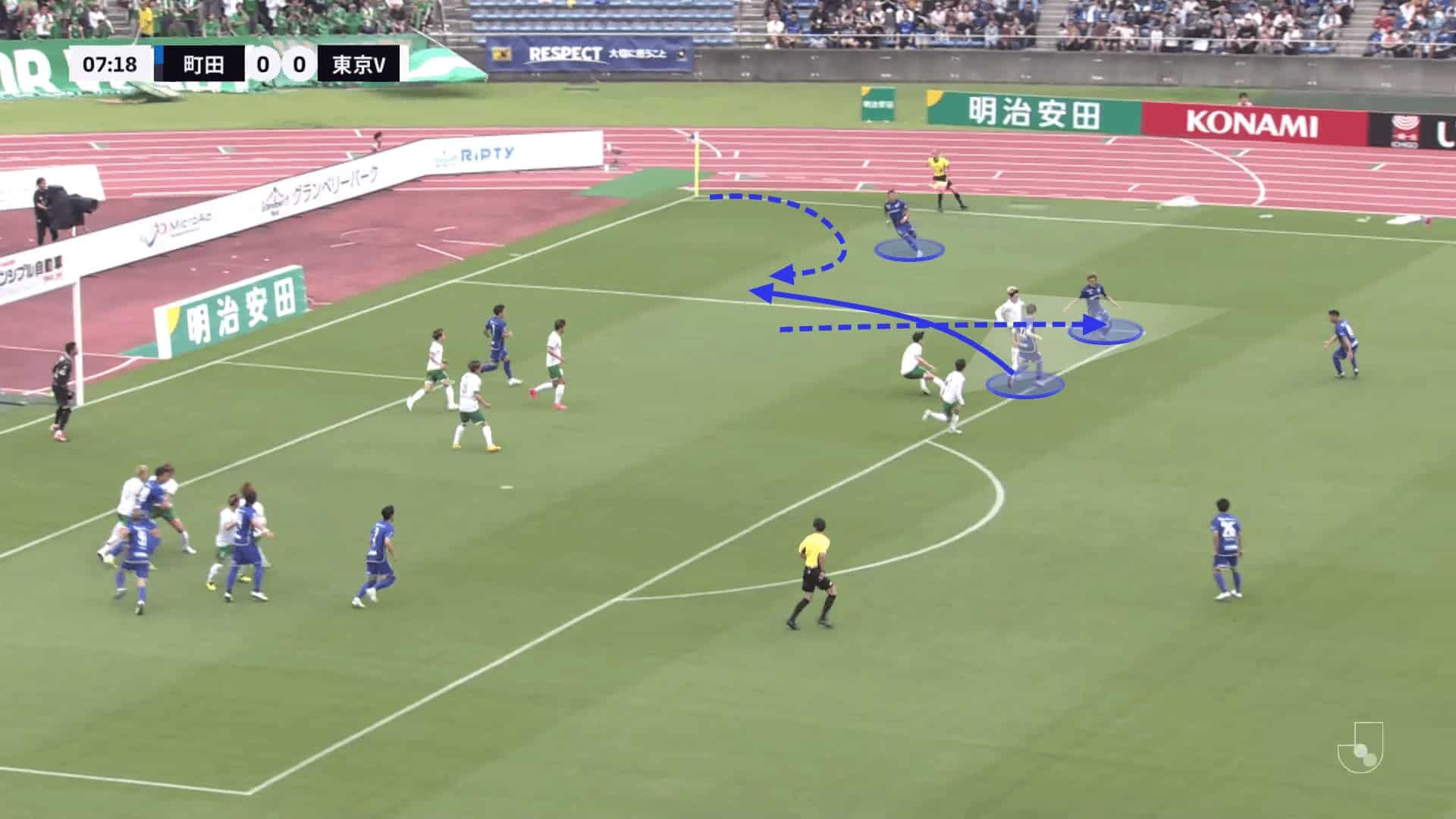

Machida Zelvia have also used a slight variant to this, where the furthest player still receives the ball, allowing him to face both teammates when the ball arrives at his feet. However, this time, the nearer player makes the run to leave the penalty area, dragging his marker away from the box. This increases the gap between both defenders, making the reverse pass to the corner takers easier to execute.

Another variation that makes Machida so interesting to watch is their use of screens during the second phase instead of just doing so during the first cross. After the short corner is taken and a further pass is played to the edge of the box, the same space is targeted. This time, we can see a player setting a screen to prevent the nearest defender inside the penalty area from coming over to cover the space.

In the Japanese J1 League, there have been many instances where teams have set up defensively with large numbers of players inside the six-yard box. As a result, the areas around the edge of the penalty area are less protected and easier to exploit.

Simply, the ball is delivered directly to the space highlighted below on the floor, which allows the player arriving in space to shoot instantly from a good distance. To ensure no player can interrupt the routine, screens are set on the nearest defenders both at the six-yard line and on the edge of the penalty area. This particular instance leads to a goal, where the shot is placed through the sea of defenders, and the goalkeeper is unable to react due to his vision being obscured.

It can be easier to execute the shot when the ball is moving towards the attacker rather than across the player’s body. Adding this context to the previous routine, the only change necessary is for the flat cross to be made towards a player in a central area, who can then lay the ball off to the attacker arriving from outside the box.

Direct Crosses into the Box

As mentioned at the start, the Japanese side has struggled to dominate aerial duels, yet have still been able to be a threat from all set plays. When attempting more traditional methods of scoring goals from set plays, such as using screens to open space around the six-yard box, the corners have lacked the accuracy for the ball to precisely drop in the small spaces highlighted below. Furthermore, attackers have often struggled to lose their markers, meaning they are unable to attack the ball unopposed.

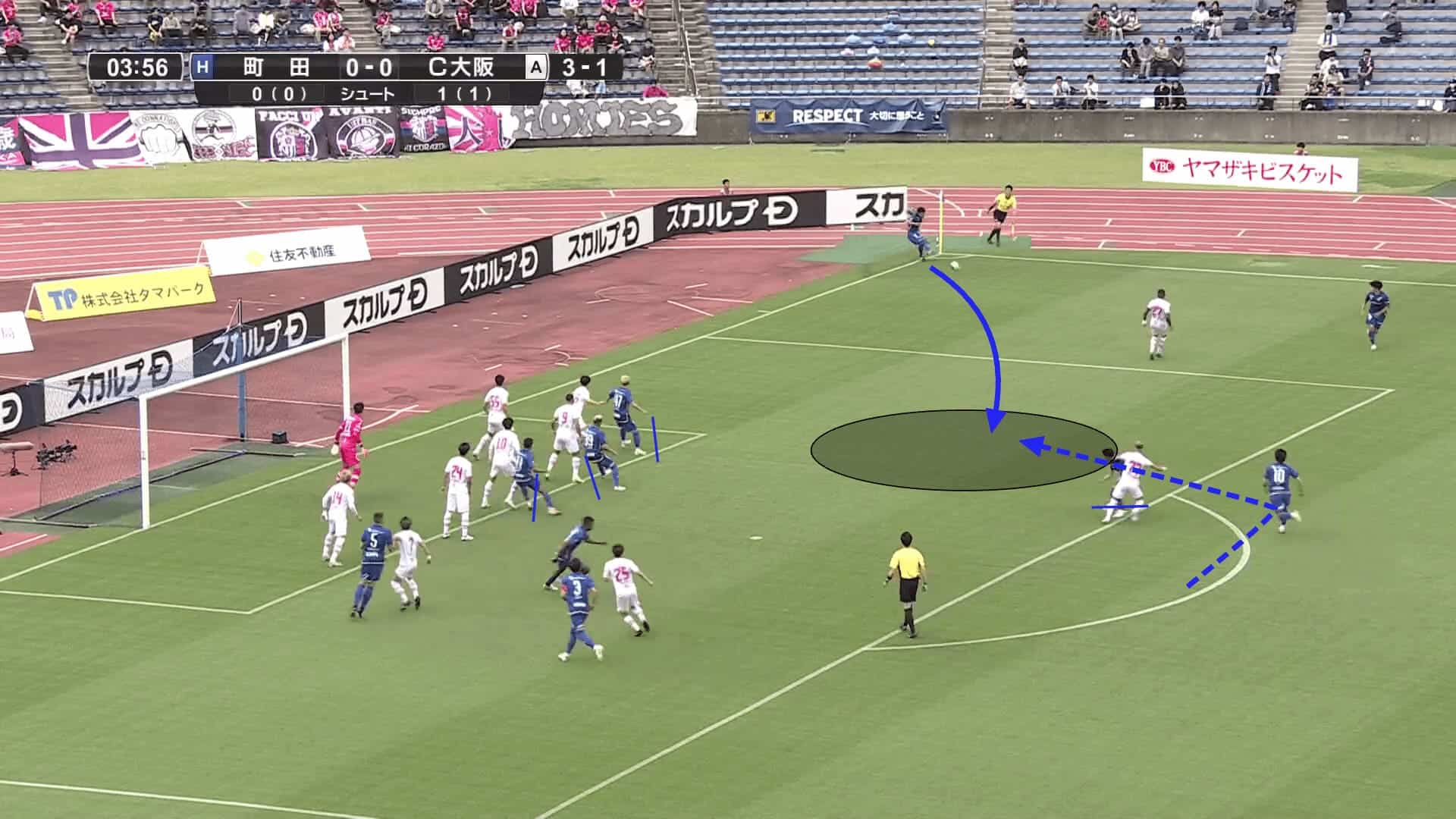

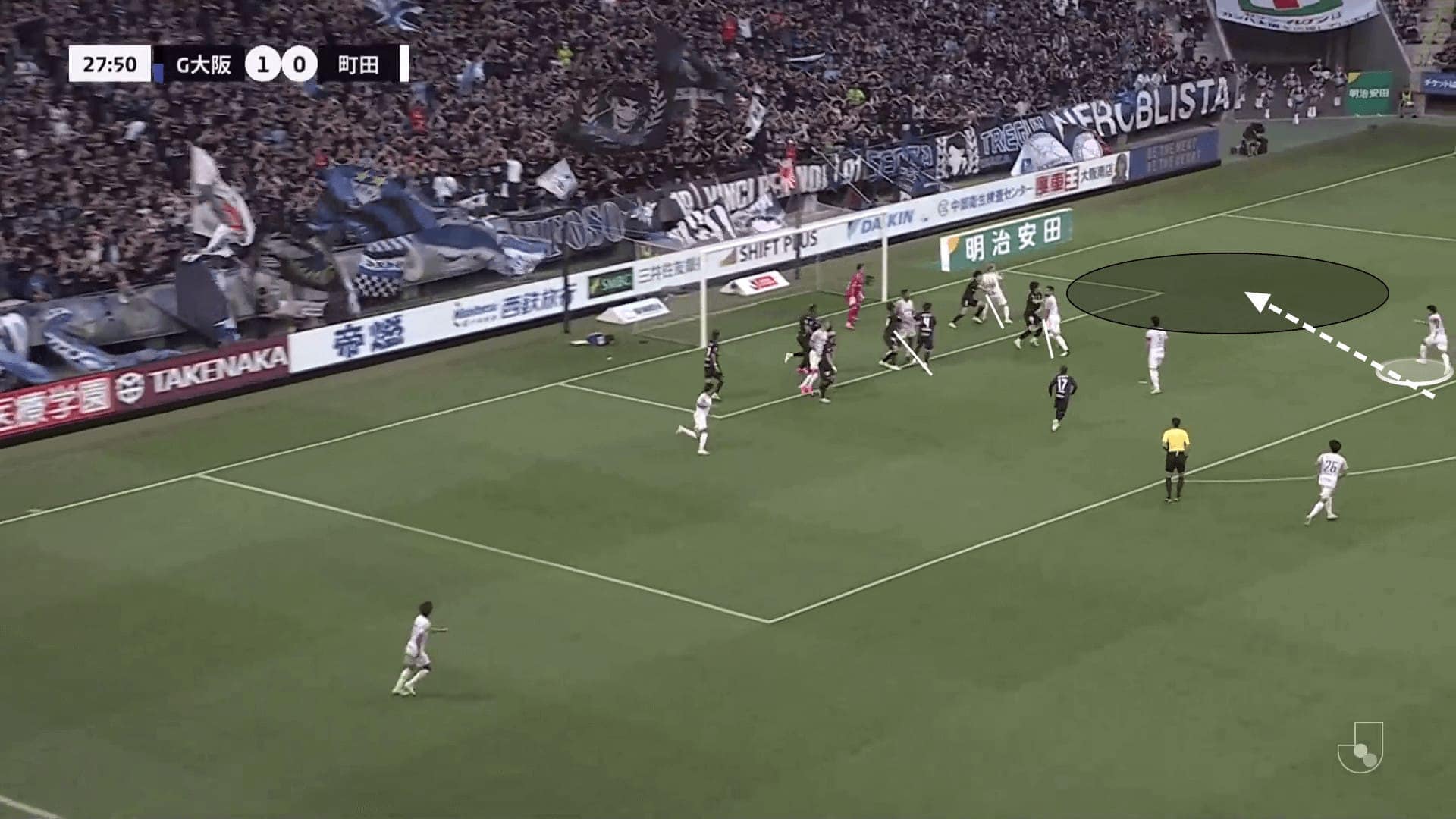

Instead, Machida continue to try find space outside of the block, rather than trying to win aerial duels inside the crowded areas. Earlier, we showed flat crosses being played to both the spaces in front of the defensive unit and in front, from where shooting opportunities were generated. This time, Machida Zelvia attempt to exploit the space on the far side, going over the defensive unit.

We can see the space at the back corner of the six-yard box is targeted, with the nearest attackers all blocking defenders from moving toward that space. Meanwhile, the attacker makes the run into the space from outside the penalty area, which allows him to arrive unmarked and in acres of space. This could be seen as both a benefit and a risk, but with the ball being floated to the area; the attacker has the opportunity to execute a volley on goal, giving the strike more chance of beating the goalkeeper with speed.

While this cross to the far side is made, one player from inside the six-yard box takes up the position on the edge of the box to ensure the team is still protected against counter-attacks and can win the second ball. From the back post position, the attacker also has the opportunity to cross the ball across the face of the goal, where attackers can meet the ball, or defenders might deflect the ball into their own goal due to the speed of the delivery and them still turning their body around.

Throw-In Success

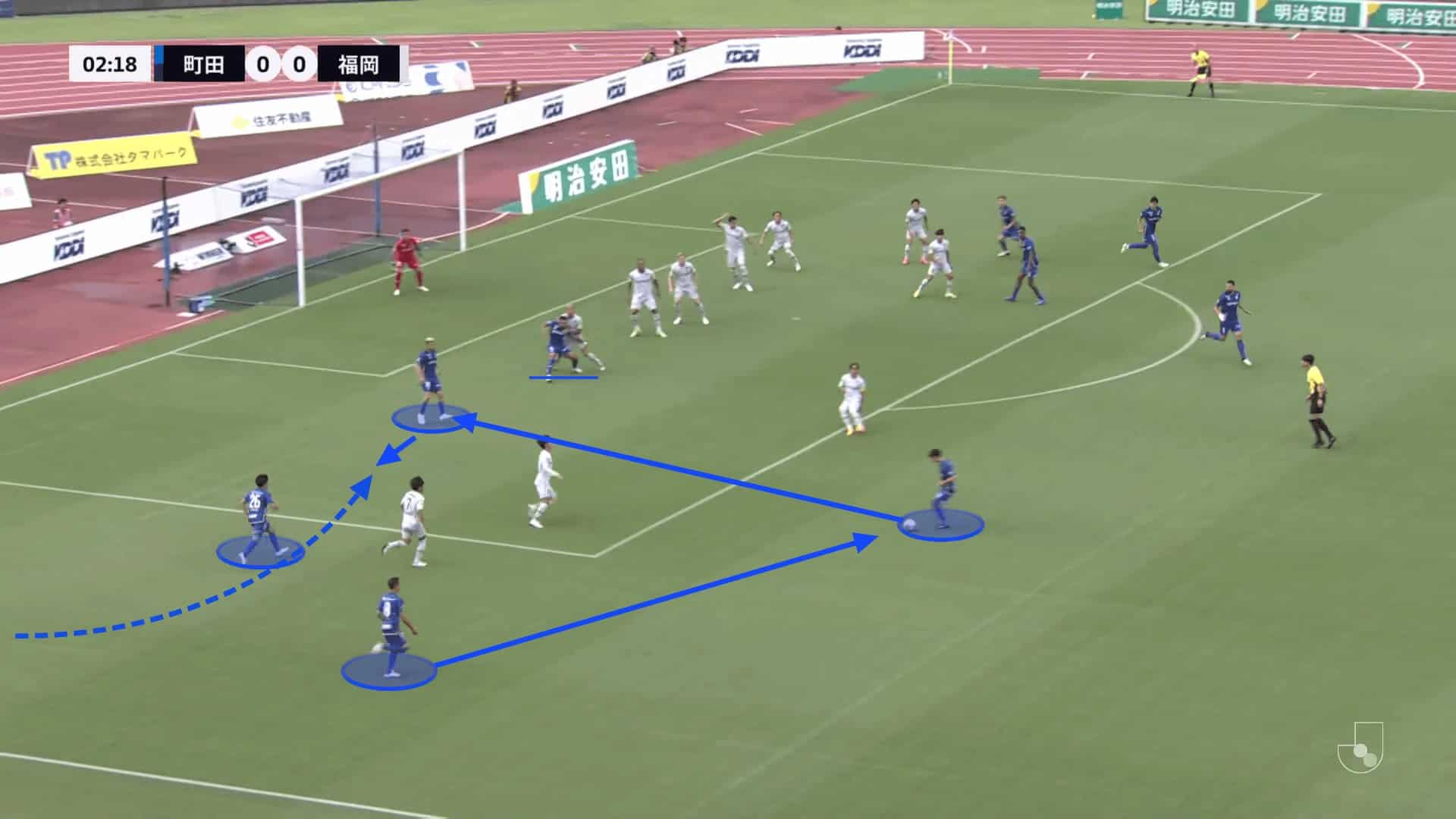

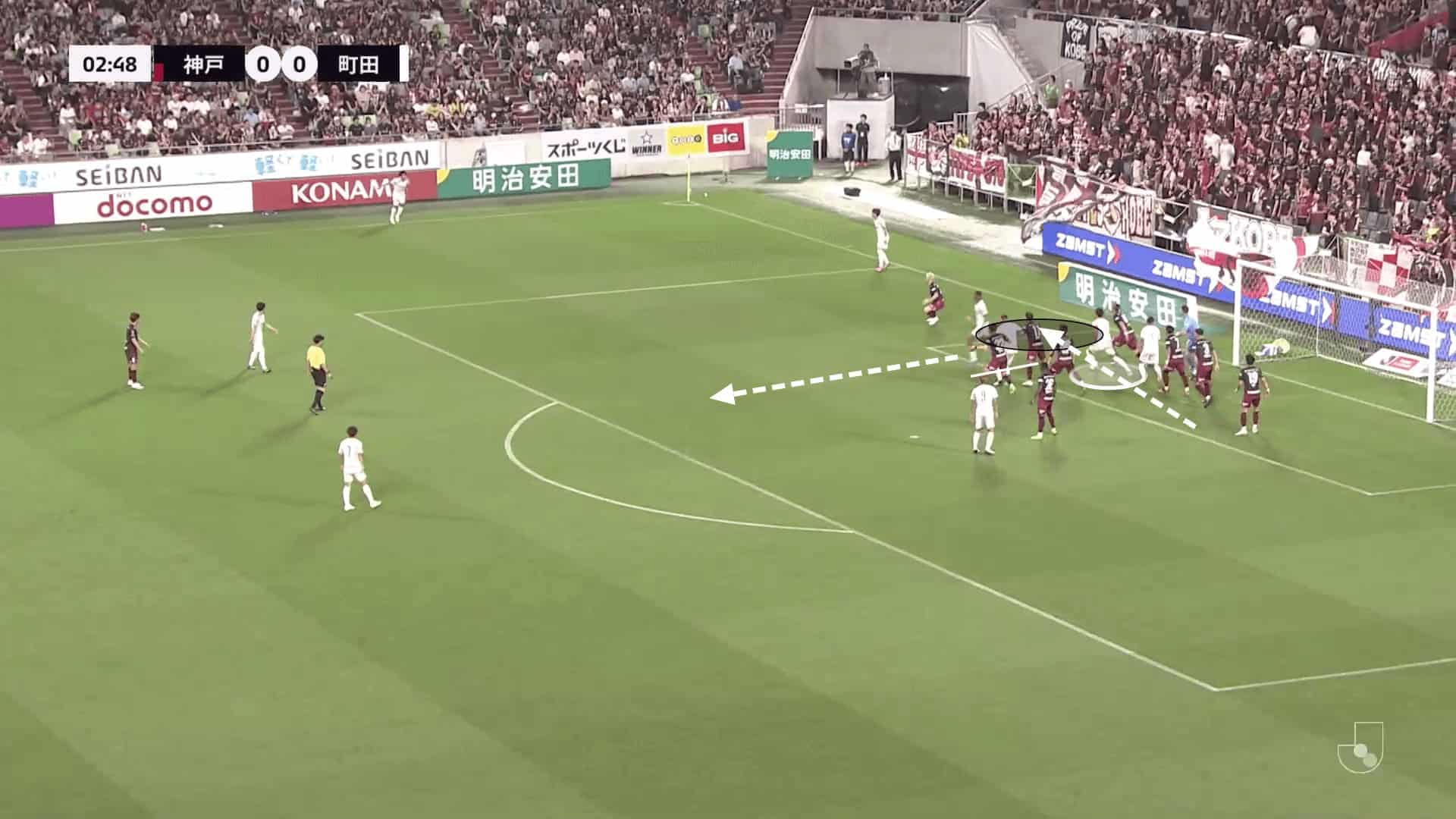

A fifth of their goals have come from chances created in throw-in situations. As we already mentioned earlier, this is not due to how strong the team is in aerial duels but more so a result of strong counter-pressing solutions, which is a key theme of their success in open play.

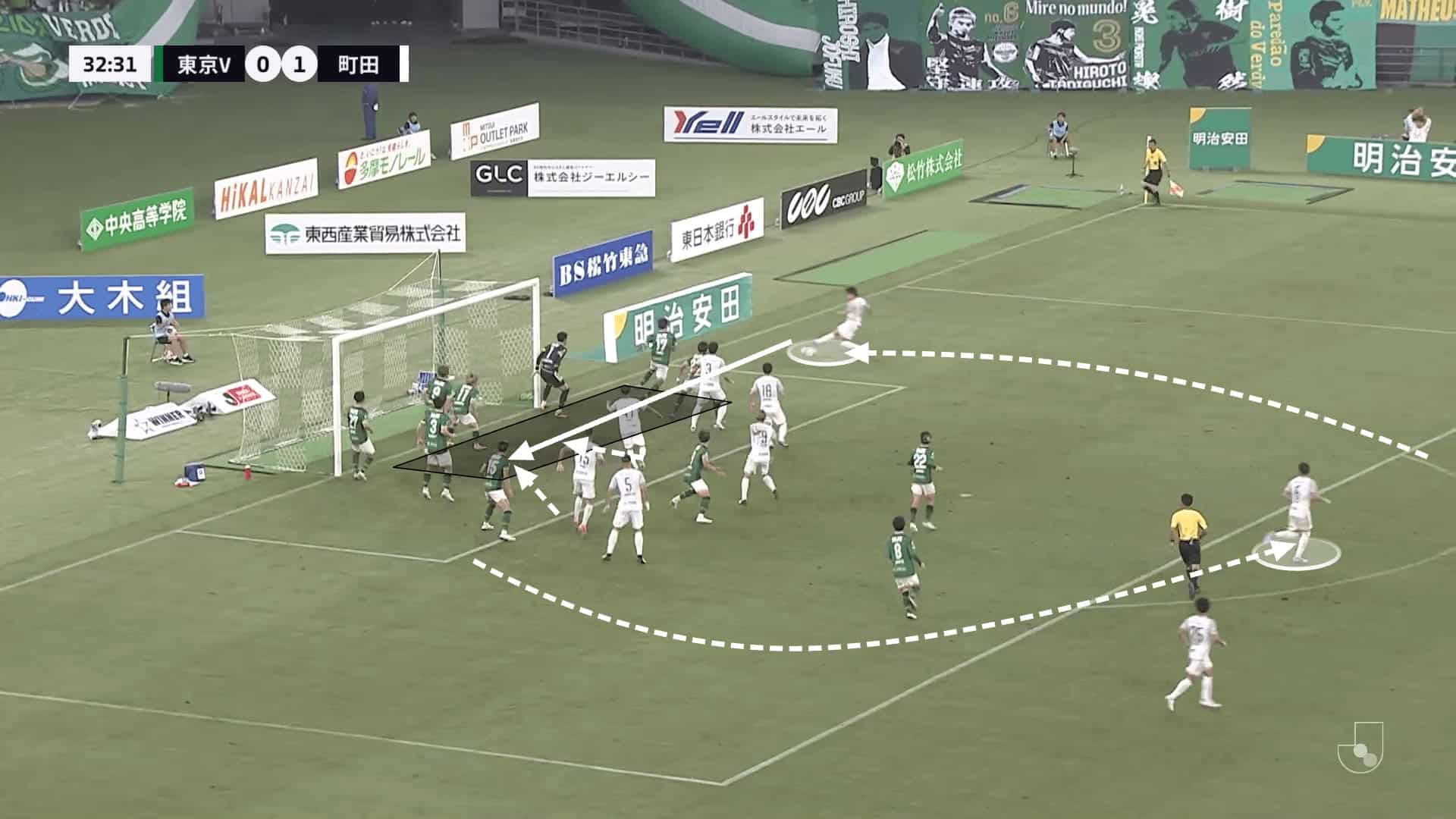

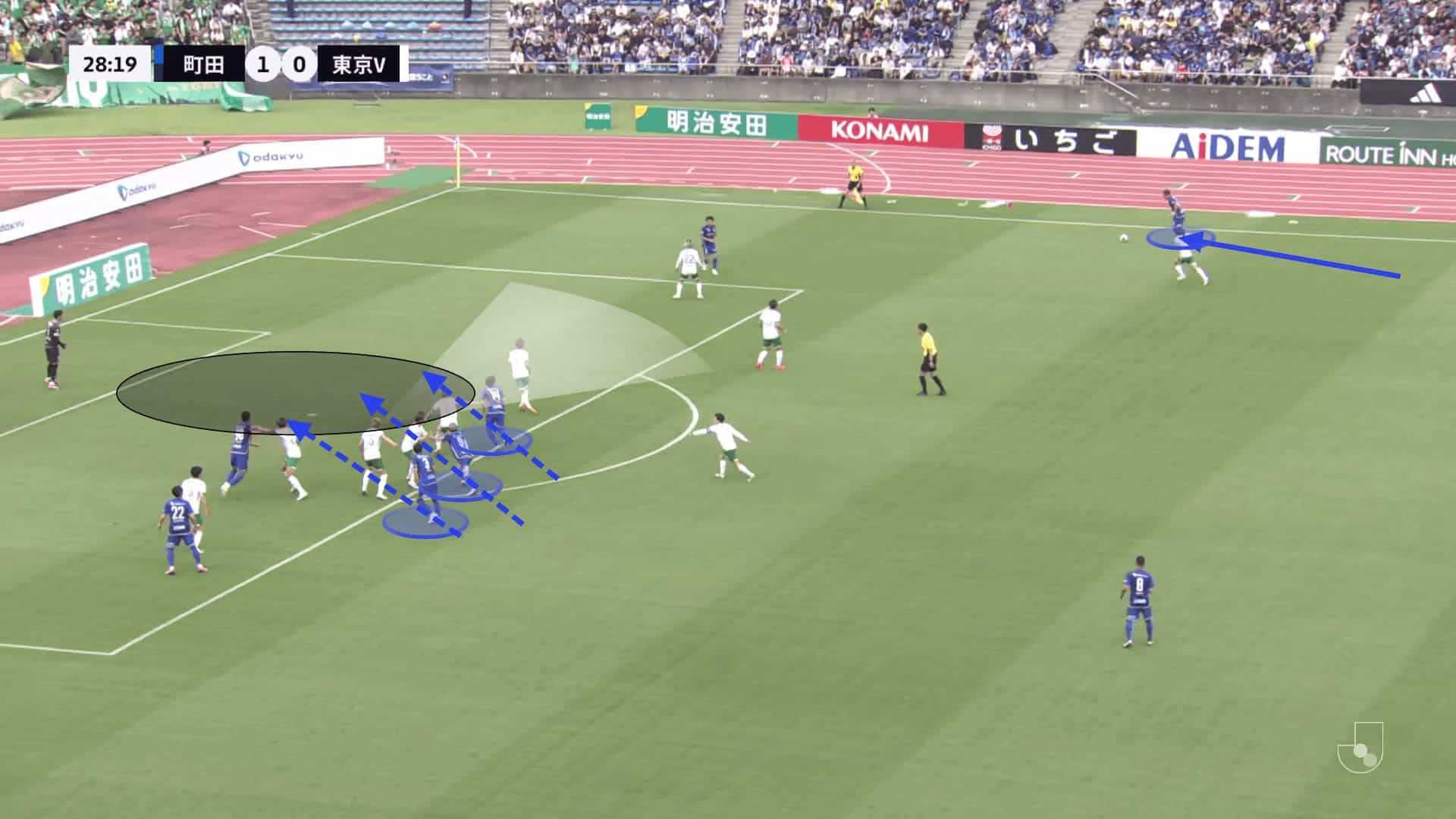

The biggest reason behind their success is how many bodies Machida send up to attack the box with, forcing opponents to defend with all outfield players, allowing them to sustain pressure more easily. As we see in the example below, they always use three players to surround the box, all of whom are ready to pounce on any loose balls headed out by the opposition. One player behind them is used to sweep up any balls that do manage to get cleared during the second phase. Furthermore, the player taking the throw moves towards the box after the ball is in play to help with the counter-press, meaning that there is nowhere opposition teams can go to evade the pressure.

Inside the box, we can see the two nearest players, who hold their position to prevent defenders from moving towards the ball, while the player highlighted slightly deeper attempts to arrive in front of them to flick the ball on towards the back post.

Inside the box, we can see the near player, who holds his position to prevent defenders from moving towards the ball, while the player highlighted slightly deeper attempts to arrive in front of them to flick the ball on towards the back post. At the same time, one player can be seen moving away from the goal to help deal with the second phase.

There hasn’t been much success from this routine in the initial phase. However, Machida Zelvia’s ability to completely dominate the second phase is what makes them so effective. With deadball situations, they have the opportunity to crowd the box and have the belief in their counter-press to retain possession no matter what. As a result, when the ball is headed away from the box, the ball is quickly recycled back to the player out wide, who puts in an early delivery.

In the second phase, defenders attempt to step up, increasing the height of their defensive line. However, with the Japanese outfit able to retain possession, they are able to deliver the ball back instantly. This means that the attackers have lots of space to run into behind the defensive line, with no defender being able to get out to the crosser of the ball quick enough, allowing him to execute his cross to perfection.

Furthermore, during the second phase, it becomes harder for defenders to track their players. This is even tougher for attacking players who have had to come back to help defensively. Defenders have to focus on the ball, and as we can see in the example below, once the attacker is in the blindside of his marker, he can make the penetrative run into the space behind the back line. Machida Zelvia leave lots of players high up and around the box, increasing the chance of an attacker being on the receiving end of the cross.

Summary

This tactical analysis has displayed the reasons behind Machida Zelvia’s set-piece success. Even though they struggled to dominate opponents in aerial duels and with the first contact, they have been creative enough to achieve success in other ways. Just like when facing deep blocks in open play, the solution isn’t necessarily to force your way through them but instead create chances on the outside of the block or sometimes from deeper where the opposition cannot close down the longer-range shot.

Their set-piece ingenuity and bravery to attack the box with so many players, coupled with their strong counter-pressing during transitions, means that Machida Zelvia are able to retain possession and sustain pressure even after unsuccessful deliveries into the penalty area. Eventually, after enough crosses or attempts to play through the block, all it takes is for one defender to lose concentration and fail to track an attacker, which is all Machida need to make the breakthrough and through their relentlessness, this is a guarantee.

Comments