This article can make one promise.

Read this tactical analysis and you’ll understand how to avoid getting beaten by Manchester City’s build-out.

Additionally, after hours of studying the Manchester City build-out, we also posit that there is no stopping Guardiola’s side as they play out of the back.

On the surface, those may seem like contradicting statements. Don’t worry, this analysis will clear up any confusion.

Ultimately, trying to stop Manchester City’s build-out is a fool’s errand. We’re asking the wrong question. Knowing what Manchester City hopes to achieve through the build-out and devising how teams can wrestle the match initiative from them are the topics we’ll address.

In this tactical analysis, we will look at some of the problems presented by Manchester City’s build-out, offer some ideas on how to cope with Ederson and his 3-2 network at the back and finish with the box midfield. Let’s start by laying out the problem.

The problem

If you haven’t read Ahmed El-Daly’s scout report in the May 2023 magazine, it’s well worth the read. His detailed analysis pinpoints the intricacies of the Manchester City build-out with the 3-2 setup at the back. The last section of his article lays out how he would counter City’s build-up. It’s an excellent exercise in tactical theory with concrete measures for stopping Guardiola and his men.

To distinguish between the two pieces, we used a similar approach in this article to the tactical analysis of how to stop Roberto De Zerbi’s Brighton Hove and Albion. At least, that was the intention.

In that team analysis, we started with data. The idea was to identify teams that had success stopping Manchester City’s build-out. Particularly, we were looking for an above-average volume in high recoveries for the opponent and low losses for City. The distinction between the two metrics is that City may lose the ball by putting it out of bounds, but there isn’t a recovery awarded to the opponent. Even if the opponent doesn’t recover the ball, we at least want to identify the metrics in which City has been more prone to mistakes in their defensive third.

Turns out, there aren’t many of those games.

Their build-up has confounded the EPL. In fact, in the 2022/23 campaign, there’s only one club to keep City below an xG of 1.25, force more than 15 low losses and record more than 10 high recoveries. That club is Real Madrid. If success leaves clues, there aren’t many to be found. City has cleaned the crime scene exceedingly well.

Let’s set the problem. Again, once you finish reading this article, read Ahmed’s magazine piece. Since he has already laid out the specifics of their build-out, we’ll stick to the basic principles here.

The first problem Guardiola creates for his opponents is the use of Ederson as a second centre-back. With his technical quality and positional depth, he’s simply not going to turn the ball over. The Brazilian is as safe at the back as they come. Shifting Rúben Dias into the halfspaces allows Ederson to give tactical balance playing off of the location of the ball and his relation to Dias. The cue for him to step higher is John Stones’ moving into midfield to form a double pivot with Rodri.

Stones is the one who initiates the change in attacking shape, who remains deeper if there’s a threat of a loss of possession and pushes higher as that threat diminishes. If there’s no threat whatsoever, he’ll push into the midfield from the onset to give City a 3-4-3 with a box midfield. If Dias needs help centrally, either Stones or Rodri can drop in line with the Portuguese.

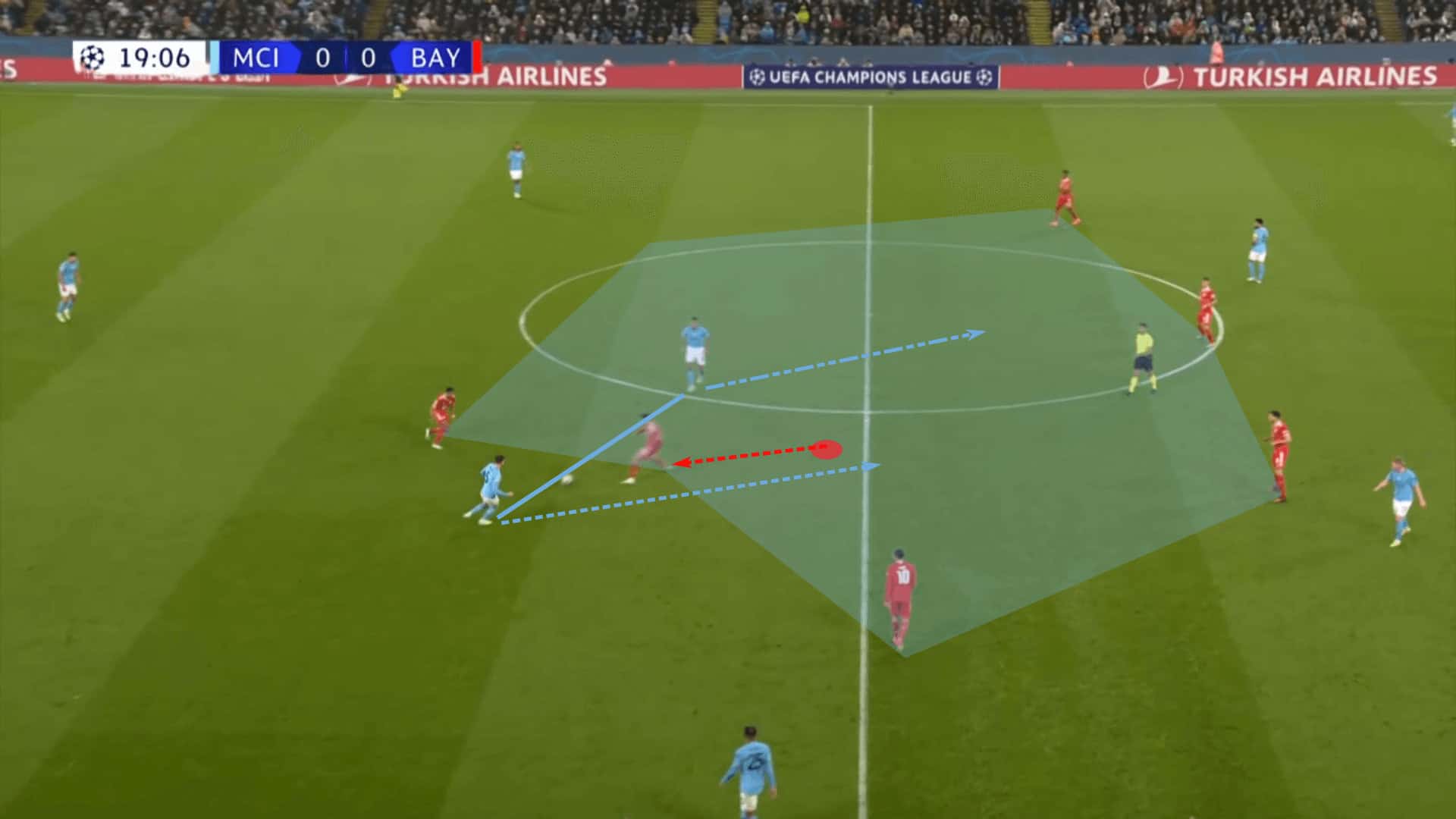

When Stones is forced to start deeper, look for Rodri to move into a support position to spring Stones into midfield. Notice how City creates space for Stones to make his move. KDB and İlkay Gündoğan push high up the pitch, virtually in line with Haaland, creating a large gap in the opposition lines, our second problem. That’s the space they want to bring Stones into.

This is one of the key ideas that Guardiola has borrowed from De Zerbi. The high/low setup is key for City, be it as they build out of the back or look to connect the lines a little higher up the pitch. Pushing the top two players in the box midfield higher up the pitch disconnects the opposition’s lines vertically. That gives City three players in a high central overload. From there, they can alternate as to who takes the highest position of the three while they make alternating runs dropping into the space between the lines and looking to run behind the opponent.

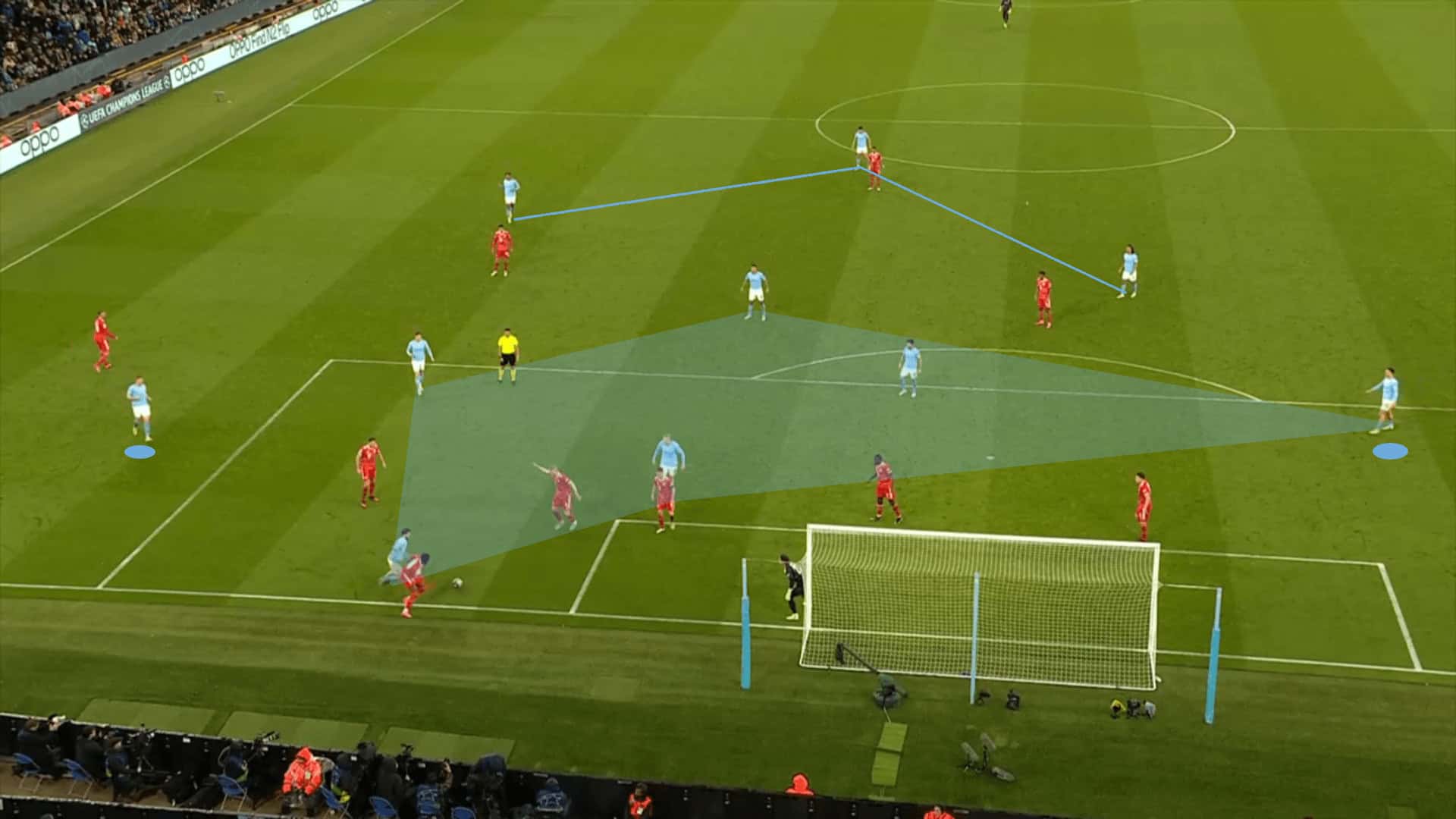

This is the most important principle that opponents must contend with. The 3-2-2-3 shape, which is really a 3-2-5, allows City to stretch the opponent’s backline with two high and wide players, one on either side while forcing opponents to commit a minimum of three players into a deep central position to deal with Haaland and company. If opponents want to remain plus one at the back, then we’re talking about four players deep centrally. That’s a total number of six players required to defend against City’s highest line.

Say the opponent commits six players at the back. If City is building out in their defensive third, they have a 6-4 advantage in the first phase.

But that’s not what they want. They want the opponents to commit more numbers forward. Should the opponent push a 5th or 6th clear in support of the high press, they leave themselves 1v1 against Manchester City’s front line and attacking midfielders. That’s a recipe for disaster, as Arsenal can attest to.

The third problem created by the 3-2 shape comes higher up the pitch. This is where opponents have to struggle with the high central overload. No team in the Premier League sends more crosses than City. Having Haaland in the box helps, but what’s more important is that they tend to establish numerical equality, increasing the likelihood of winning the first or second ball off of the cross.

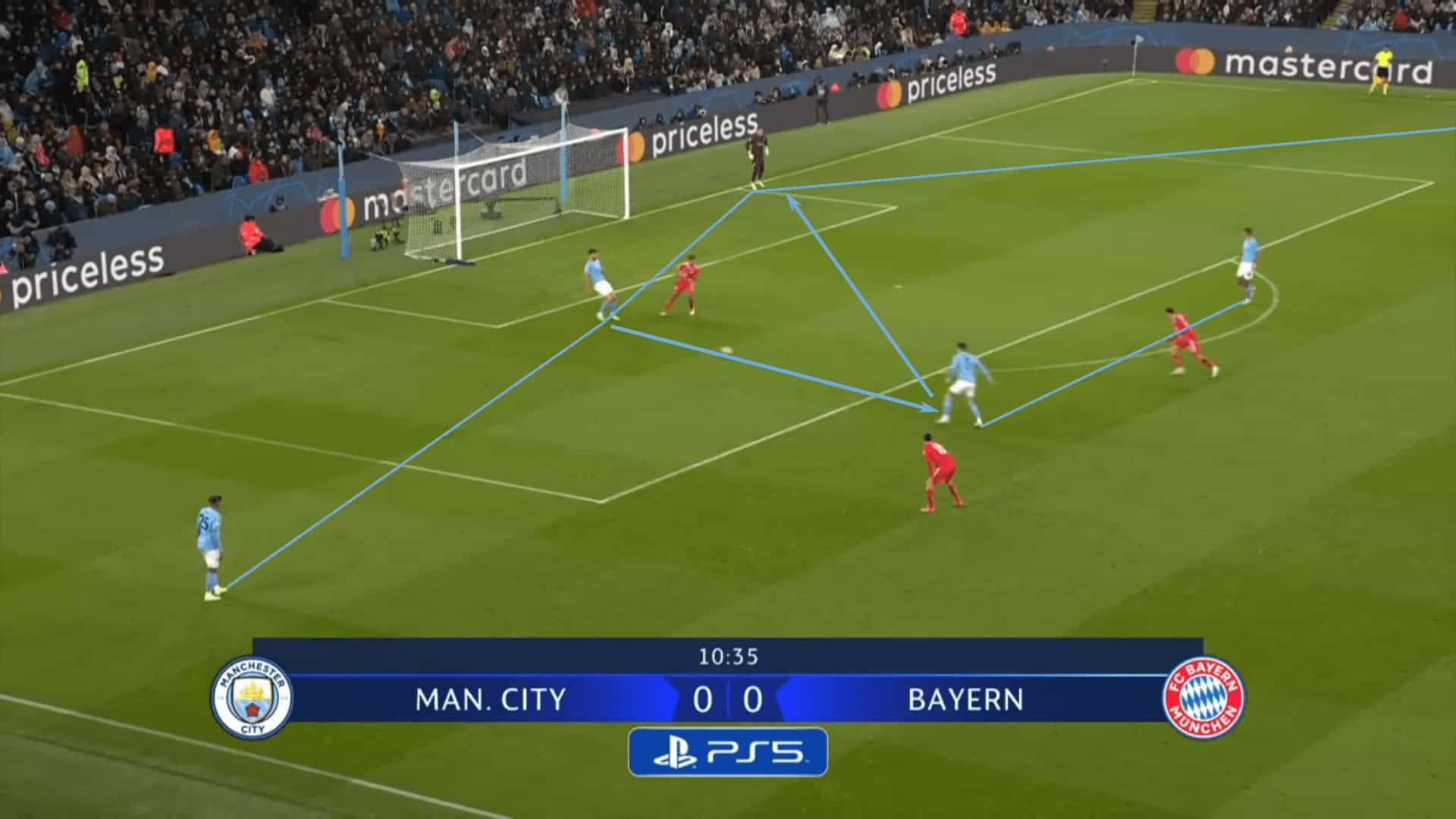

And when a cross isn’t sent, they’ve pinned the opponent’s backline into a deep central position, allowing more attackers to arrive at the top of the box. That’s how City got their opening goal against Bayern Munich in the first leg of the Champions League.

Much like Brighton’s build-up, the intent is to disconnect the lines vertically to then play into numerical quality or even a superiority higher up the pitch. Unbalancing the opponent along the y-axis creates opportunities for more direct attacks, the topic of another analysis.

Finally, once City enters the box, most of the team is either in the penalty area or at least in shooting range. They’re willing to take risks at the back, as seen below, trusting their backline to deal with danger. In this sequence against Bayern, they’re effectively man-for-man at the back. In all likelihood, Kyle Walker figures into the equation when an elite 1v1 player features for the opposition, such as Vinícius Júnior.

So, the problems identified are that Manchester City can use Ederson as that second centre-back, and Stones pushes into midfield to give City a numerical superiority there, allowing City to push three players into high central positions. In doing so, they disconnect the opposition’s lines vertically and create more direct attacks on goal. Even in the final third in open play, they can use the same structure to unbalance opponents.

So how do you stop this build-out?

You don’t.

Containing Ederson’s threat

Stopping the build-out is virtually an impossible task. At best, there are ways to contain it and limit its effectiveness without leaving the backline exposed.

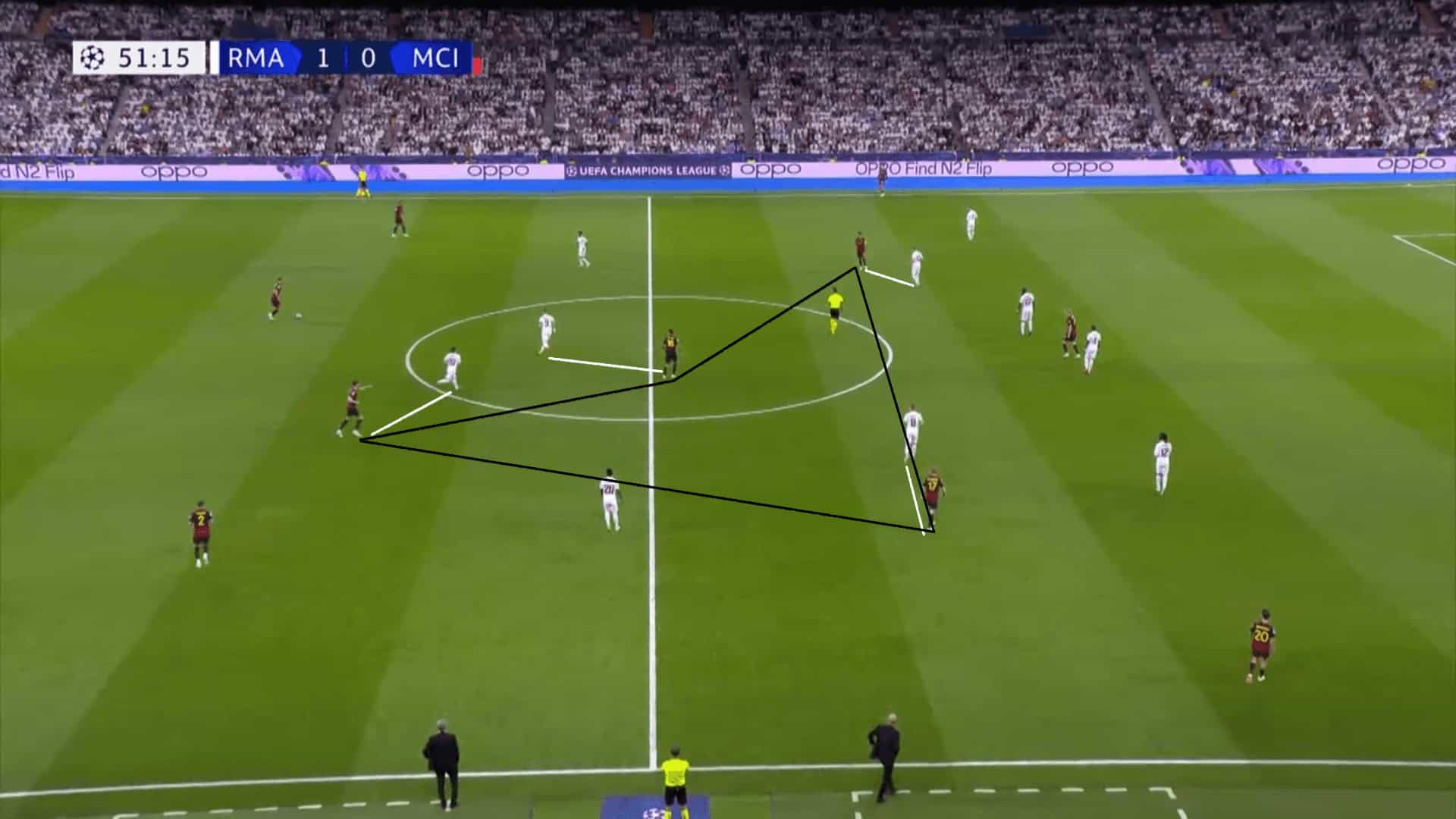

Carlo Ancelotti had a clear plan for how to engage City’s backline. There were two noticeable cues to signal increased pressure on the ball. The first was a negative pass. Notice the tight marking of forward passing options. Real Madrid has eliminated opportunities to play forward, forcing Manchester City to play backwards. As the ball is played back, Real Madrid is quick to move with it, applying pressure on the new first attacker.

With those forward passing targets still tightly marked, the clear solution is to play another negative pass, this time to Ederson, the last remaining option. Real Madrid is not going to take the ball off of him, but what they can do is force a hurried delivery, giving them an opportunity to fight for the first and second ball while potentially ending City’s build-out.

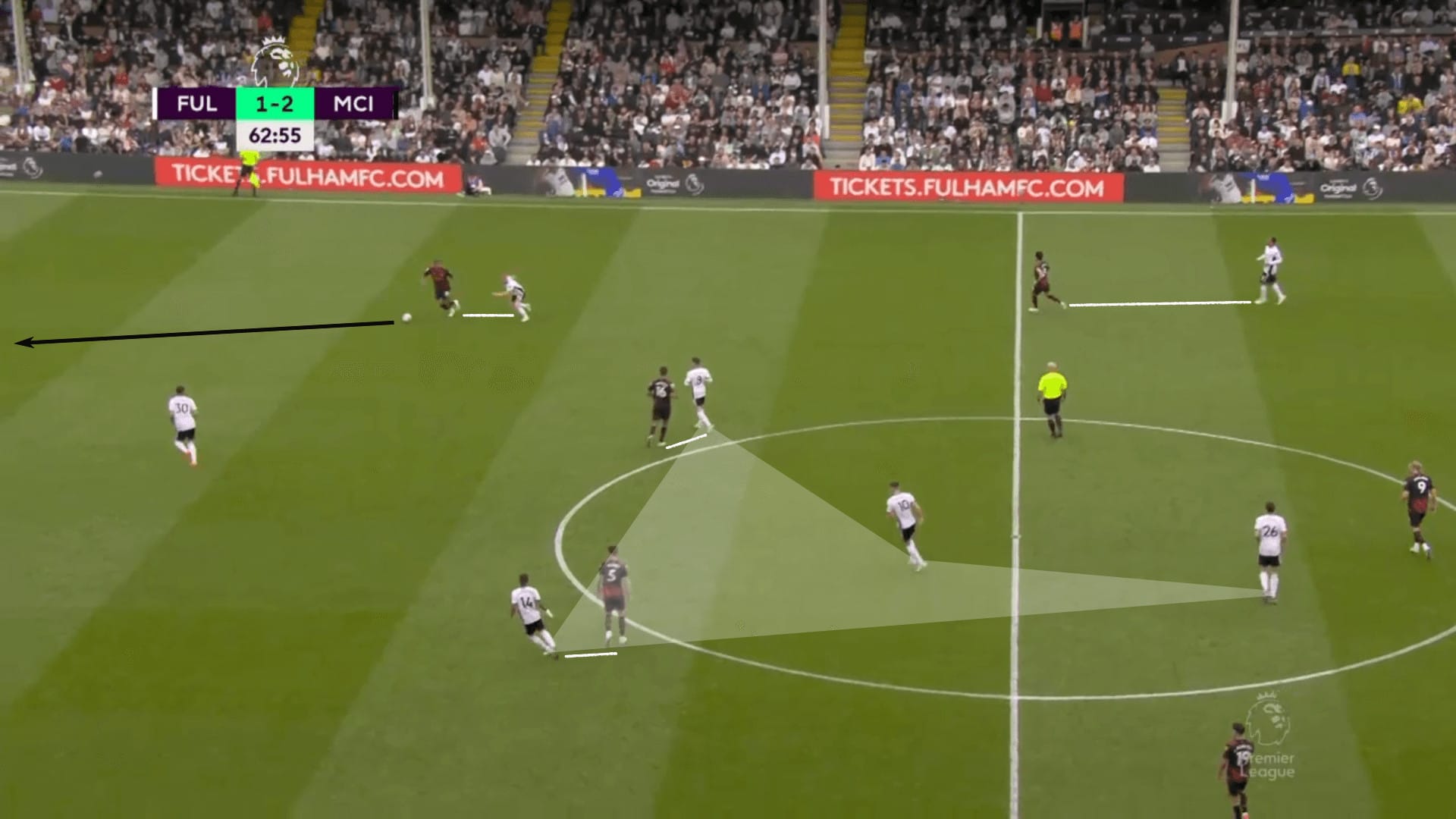

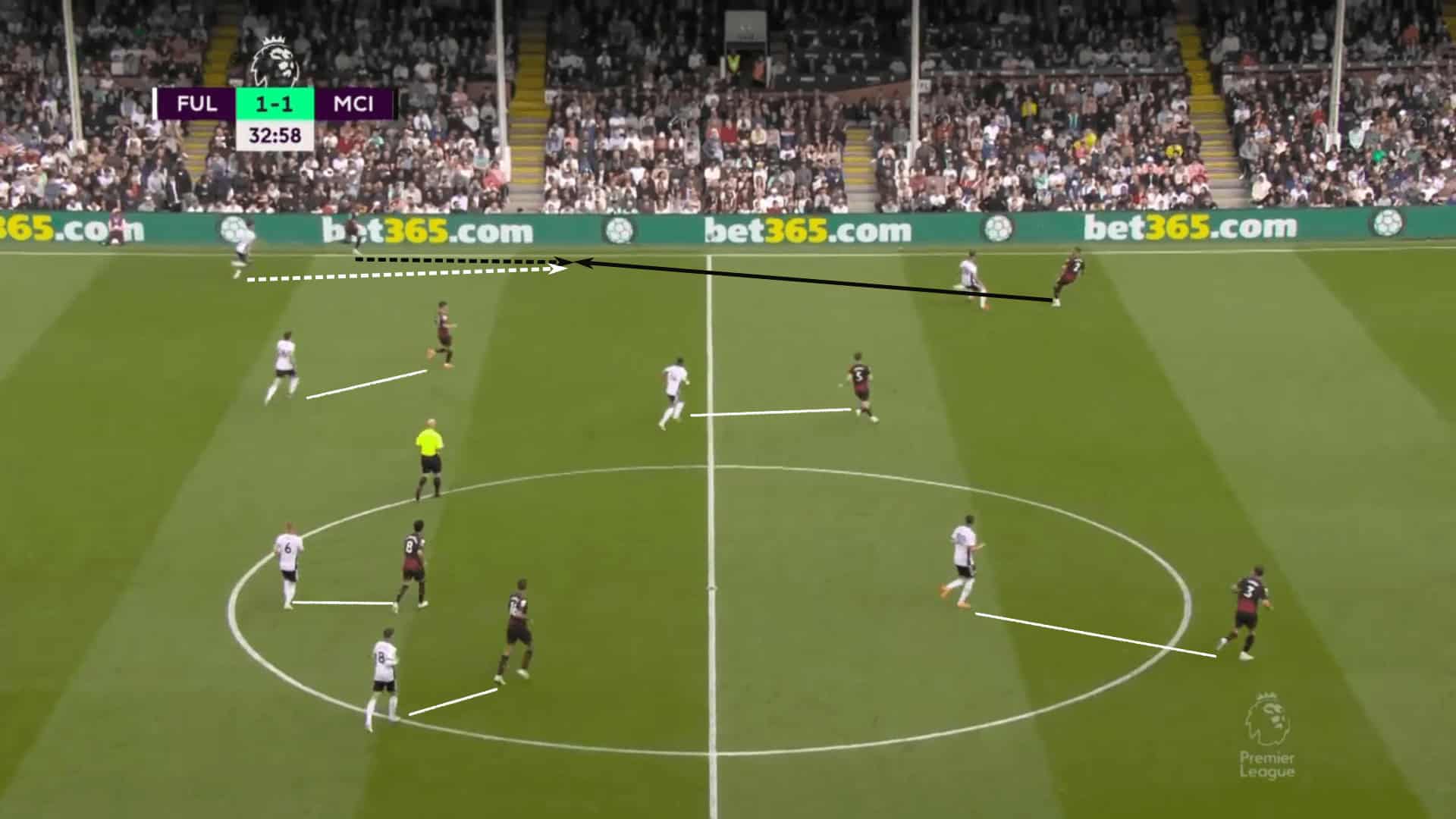

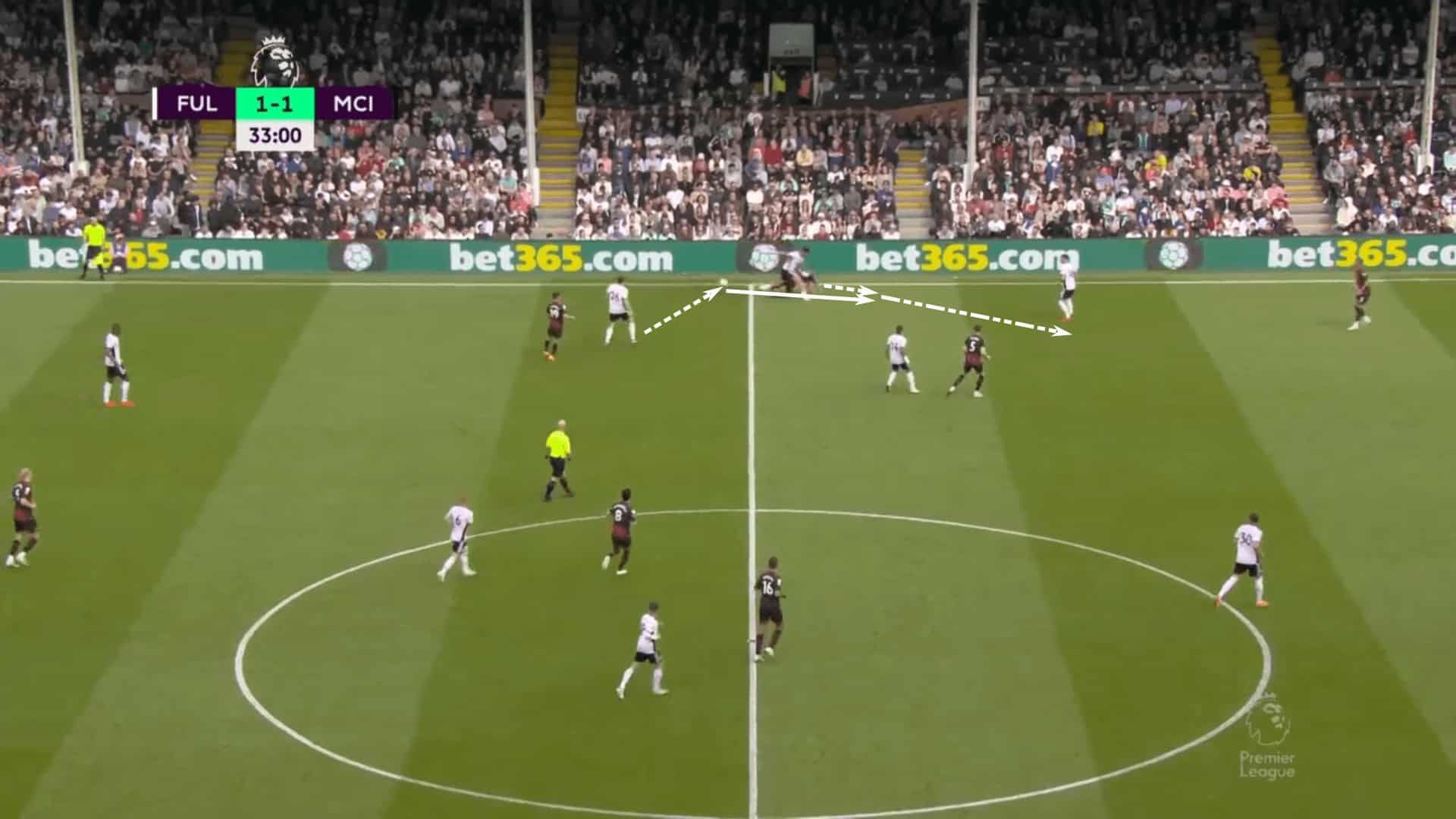

These tactics were used by Marco Silva’s Fulham as well. In a 3/4 press, they tightly marked Stones and Rodri, remained compact centrally to deny access to the high central overload and used two players to pressure the left centre-back, Nathan Aké, and Dias. The safest pass was all the way back to Ederson.

He had time to take a touch and attempt the switch of play, but that commitment from Fulham to target negative passes into Ederson as pressing cues led to a rushed delivery and turnover.

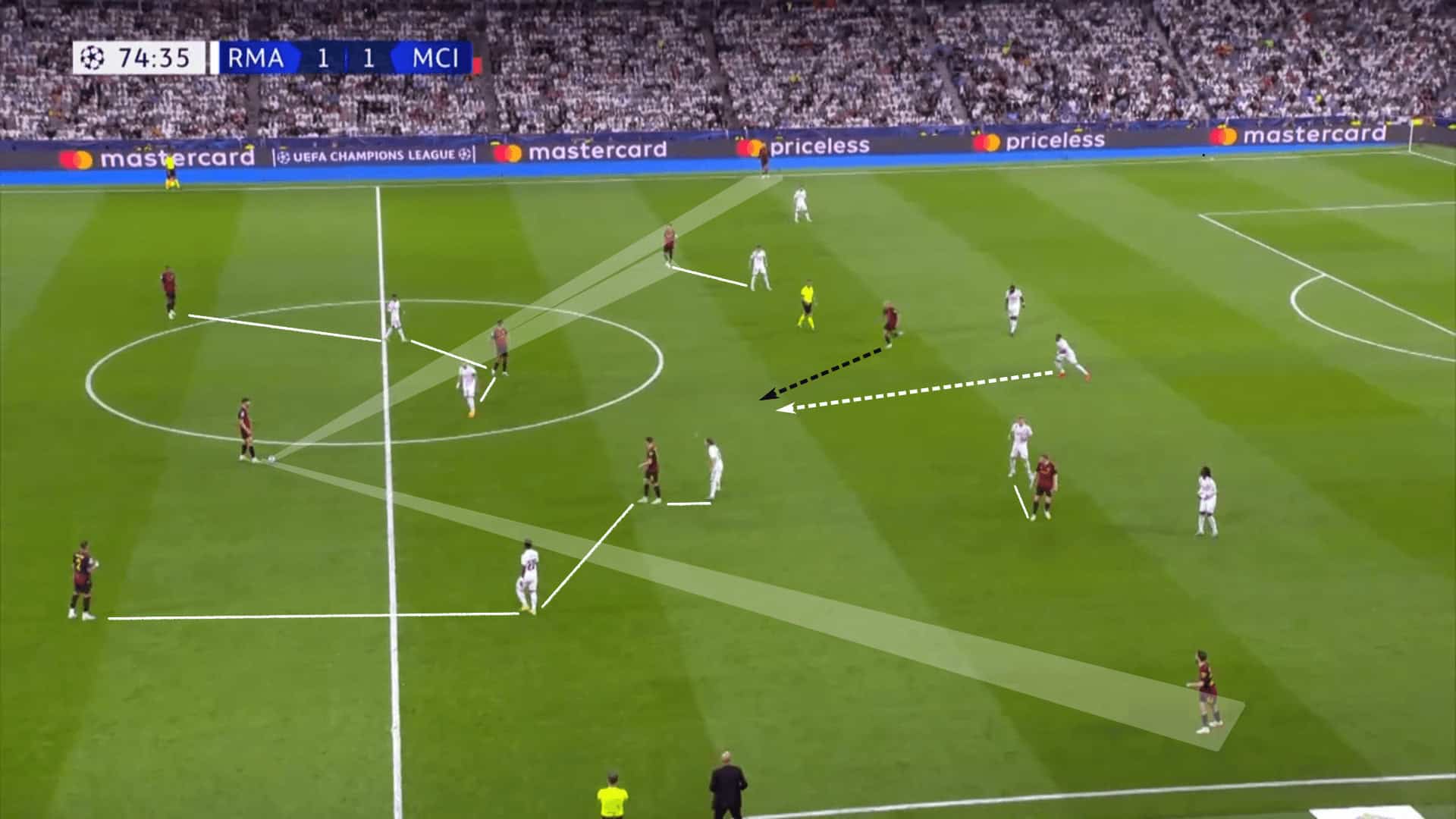

The other noticeable trigger in the match against Real Madrid was funnelling play into Dias and forcing him to play over the press. In the image below, the City midfield box is accounted for, as is Haaland. The only realistic options are a pass to the right and left centre-backs or Bernardo Silva on the right wing. Real Madrid put the initiative on Dias to beat the press.

In the sequence below, he is left alone. Real Madrid wants him on the ball as the free player. As he receives, short and intermediate options are tightly marked. They’re challenging him to play over the press.

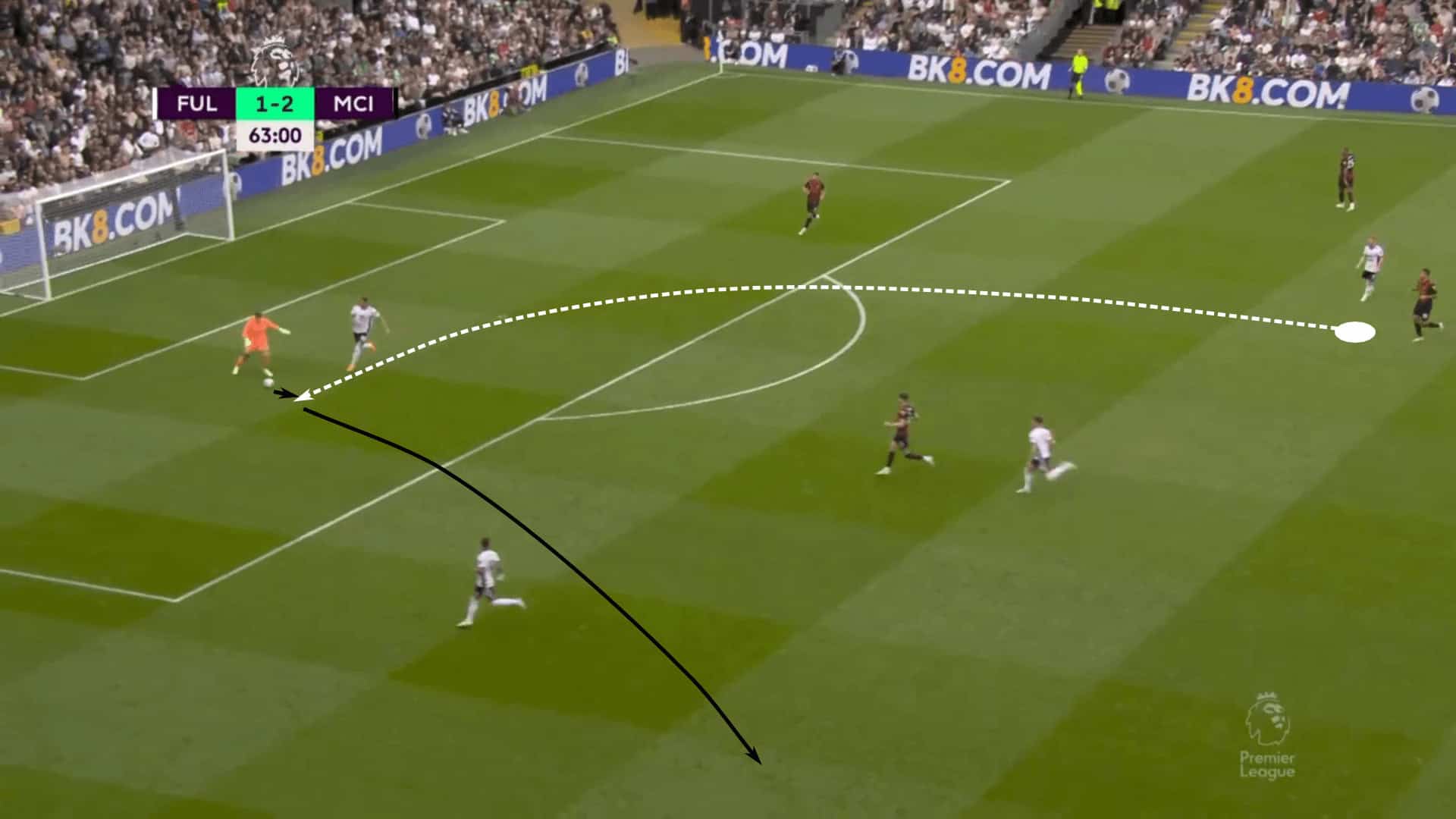

Space is gradually closed down as Real Madrid attempts to impact the timing of his action and force a strike that’s less clean technically. The pass is sent across the field to Walker, which is another important piece of the puzzle. The ball is a difficult one to control and City loses a couple of seconds as he attempts to settle the ball. Real Madrid uses that time to get numbers near it and poke it free from Rodri, earning their high recovery.

Walker is a phenomenal athlete and defender, but if there’s one player on Manchester City you’d want to target in possession, it’s him. Leaving Walker as the free man and inviting a long delivery into him is a pressing opportunity. Eliminate his options to play forward, or at least make them highly contestable passes, and he’s unlikely to play his way out of the press.

When City does play out of pressure on the right, at least when Walker is in the game, the sequence that’s most likely to break the press is a negative pass leading to a quick switch of play. Whether it’s Walker or Akanji on the right, tracking Dias and Ederson, or even the deep-checking runs of Stones and Rodri, is critical to the high press’s success.

And this is where City’s back three can hurt you. If you gamble and commit numbers toward the ball, you have to win it or end the play. From that back-three set-up, once the first negative pass is played, the farside centre-back has so much space to run into with only one player shadow-marking him. It’s simply too great an angle for the shadow-marking defender to cover. In this instance, Akanji makes the run forward and City beat the press.

There’s an inherent risk in engaging City through a high press. With their quality at the back and the fact that Ederson has the skill to give them a truly numerical and qualitative advantage, more numbers are required to keep City from building out on the ground. However, if you do that, they’re equally comfortable playing into the high central overload. Just look at the way City scored their opener against Arsenal. They played long into Haaland who controlled the ball and laid it off to De Bruyne. That quality of attacking the opponent with numerical equality is a recipe for disaster.

This section was all about containing City’s build-out and taking opportunistic pressing cues. But consistently high pressing this side is the equivalent of football roulette. You don’t know which attack is going to hurt you, but given enough chances, they will. So rather than engaging in the high press, the key is to impose through deeper defending, eliminating Ederson from the attack and forcing City to break through a wall in the mid-block. The idea is to defend from a position of strength rather than take City’s bait and defend in the way they want. They want you to chase in the high press, so don’t.

Here’s what the alternative looks like.

Dealing with the box midfield

The higher up the pitch you press City, the greater the risk you take on. The teams that have had the greatest success limiting the Sky Blues this season have tended to sit deeper on the pitch. The better teams on the schedule found a happy medium in the mid-block whereas lesser teams have parked the bus and battled in the box like madmen.

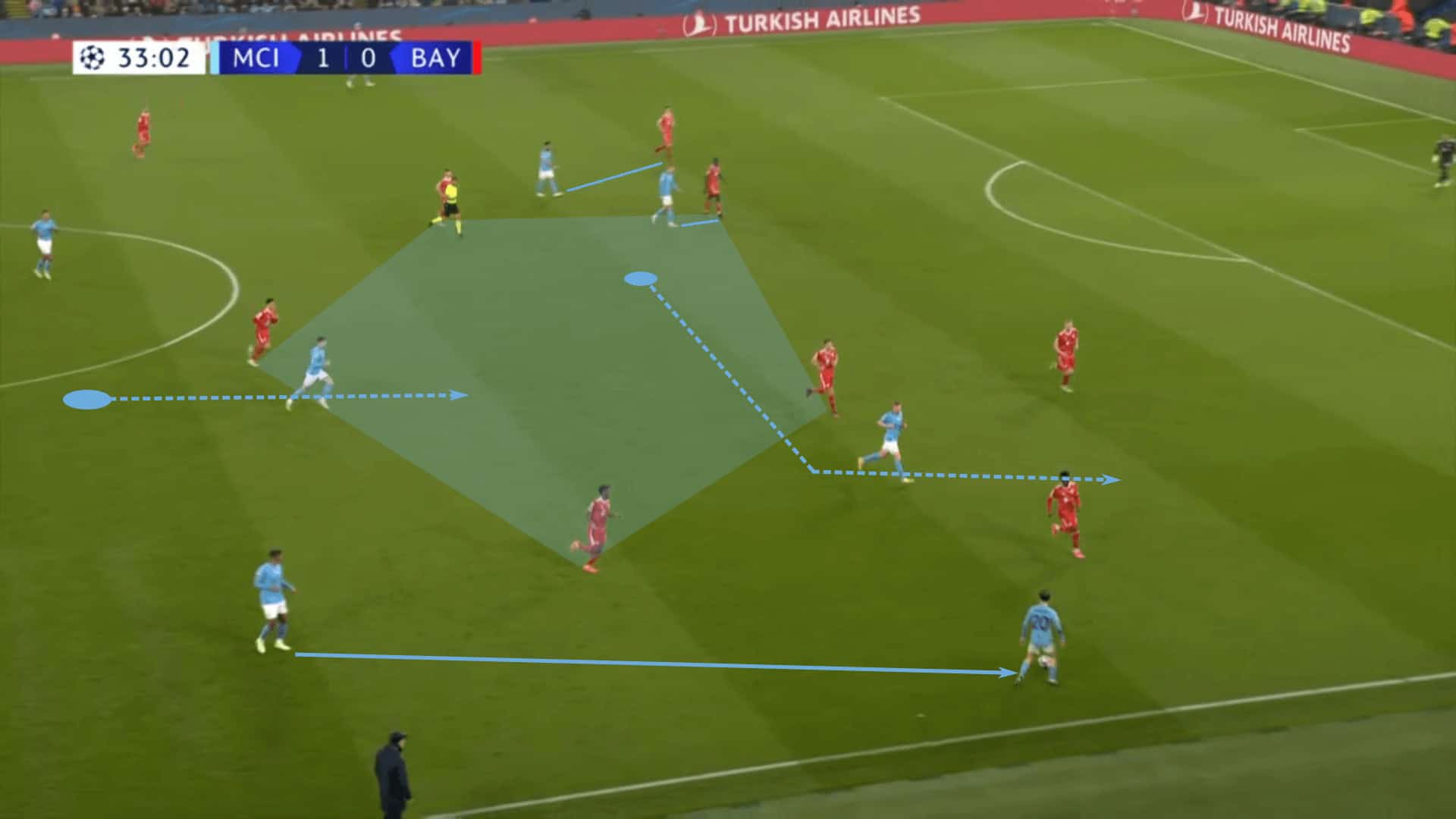

Regardless of where teams choose to press City, one of the key items to take care of is the handling of the midfield square. Since we have an example against Bayern Munich in the high press, let’s start there.

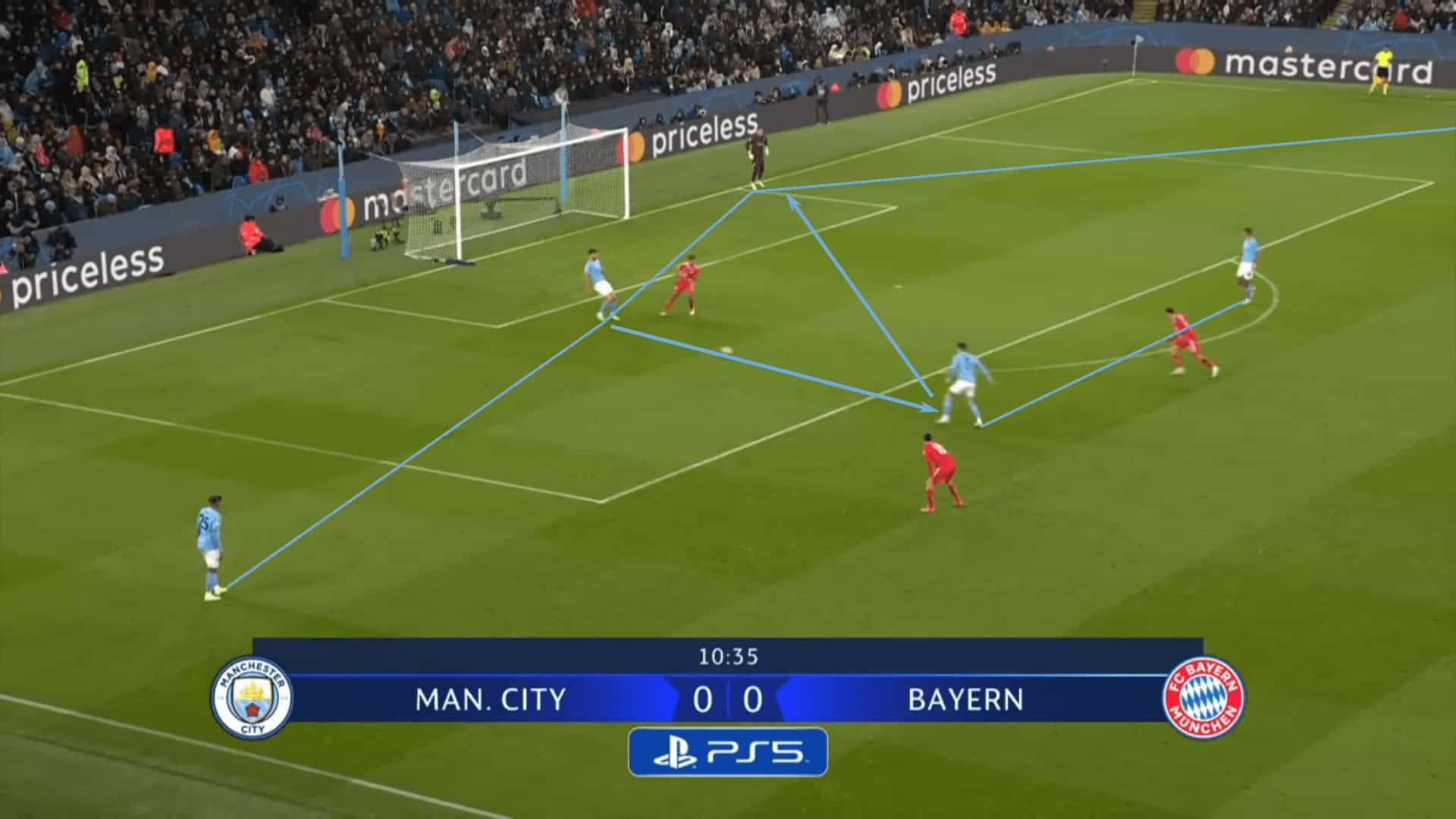

Bayern were very aggressive in the press, but they failed to negate City’s short and intermediate options. This is a prime example. City started from a goal kick with Dias on the right and Ederson on the left, leaving Stones to push into midfield. Look at Ederson as the left centre-back and it looks like a standard back-four build-out.

City managed to play out of the press in this instance largely because Bayern didn’t commit enough numbers forward in the high press. The triangulation from Dias to Stones to Ederson was far too simple. Failure to tightly mark the double pivot essentially guarantees City a successful first phase of the attack.

Some clubs like to have their forwards simply chase the ball. The instructions are simple and there’s zero interpretation needed. That leaves the midfielders to read passing lanes and shadow-mark players behind them. Ideally, they’re the ones making the interceptions.

Against City, this is a death wish. Chasing the ball without numerical equality will cue the long pass. Sending two few numbers, as we see with Bayern, will lead to easily broken lines. Even if a team features three forwards, we have to account for the fact that Ederson is as fundamental to the build-out as any other member of the backline. He gives them a decisive extra player.

Rather than pressing City high up the pitch, especially the central part of the field, Real Madrid had a lot of success inviting City to come nearer to midfield. One reason for this is that it’s simply easier to manage space from the low block. The second is that it severely limits Ederson’s impact in possession. Once City pushed into the middle third, they operated as a more standard back-three. If help is needed, either Stones or Rodri will drop in line with Dias, but this is functionally a standard back-three as City looks to connect the lines.

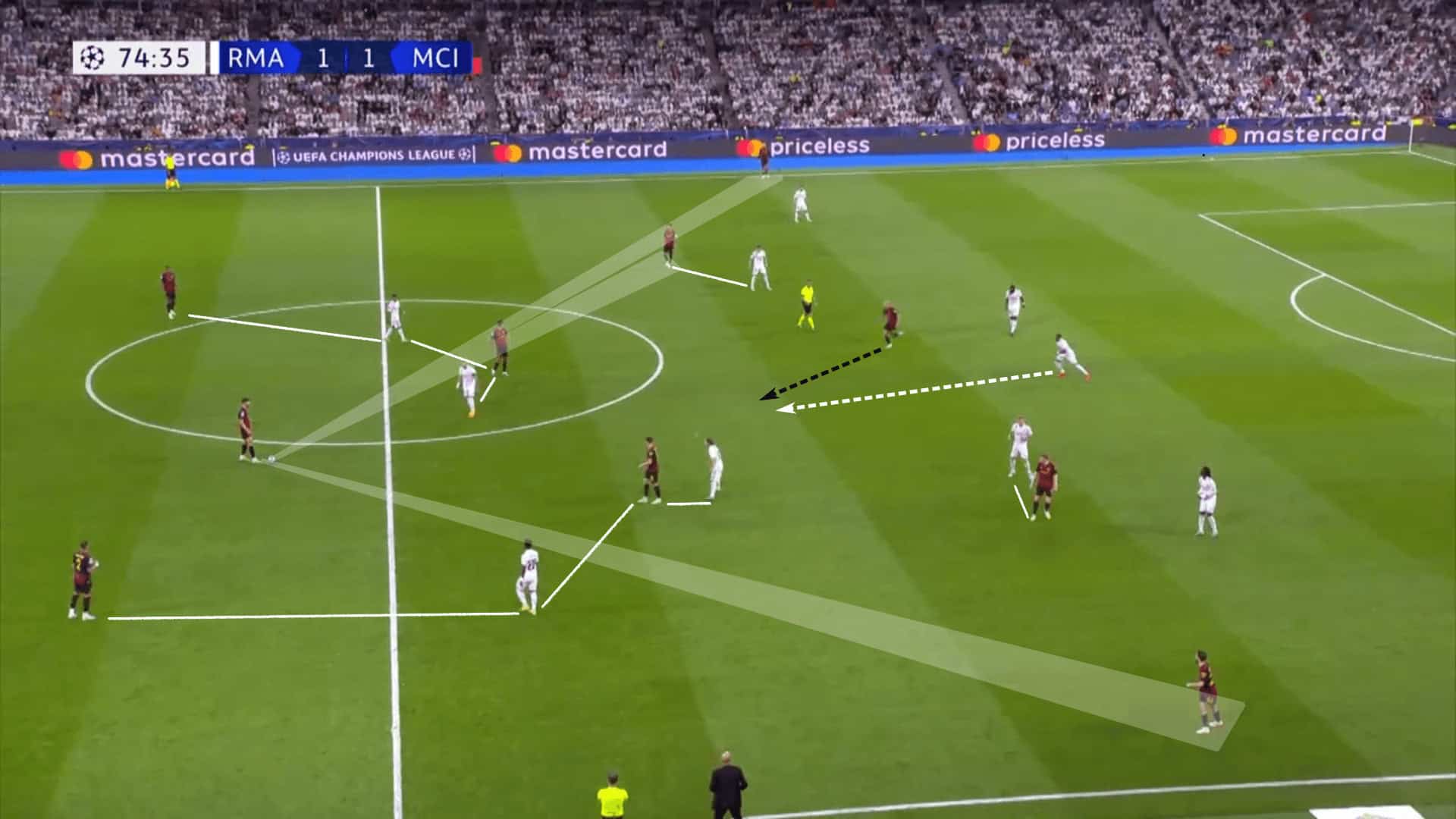

In the middle third, the distances between the lines are a little tighter, which makes accounting for the midfield square easier. For Real Madrid, it was often Karim Benzema and Luka Modrić who were responsible for either marking or shadow-marking the double pivot. Meanwhile, notice the positioning of Fede Valverde and Toni Kroos. They’re very tight on De Bruyne and Gündoğan.

Another thing to note as Real Madrid settled into their midfield line of confrontation was the positioning of the two wide forwards, Vinícius Júnior and Rodrygo. They give Real Madrid the horizontal compactness necessary to help with the double pivot and are also close enough to apply pressure on the two outside centre-backs.

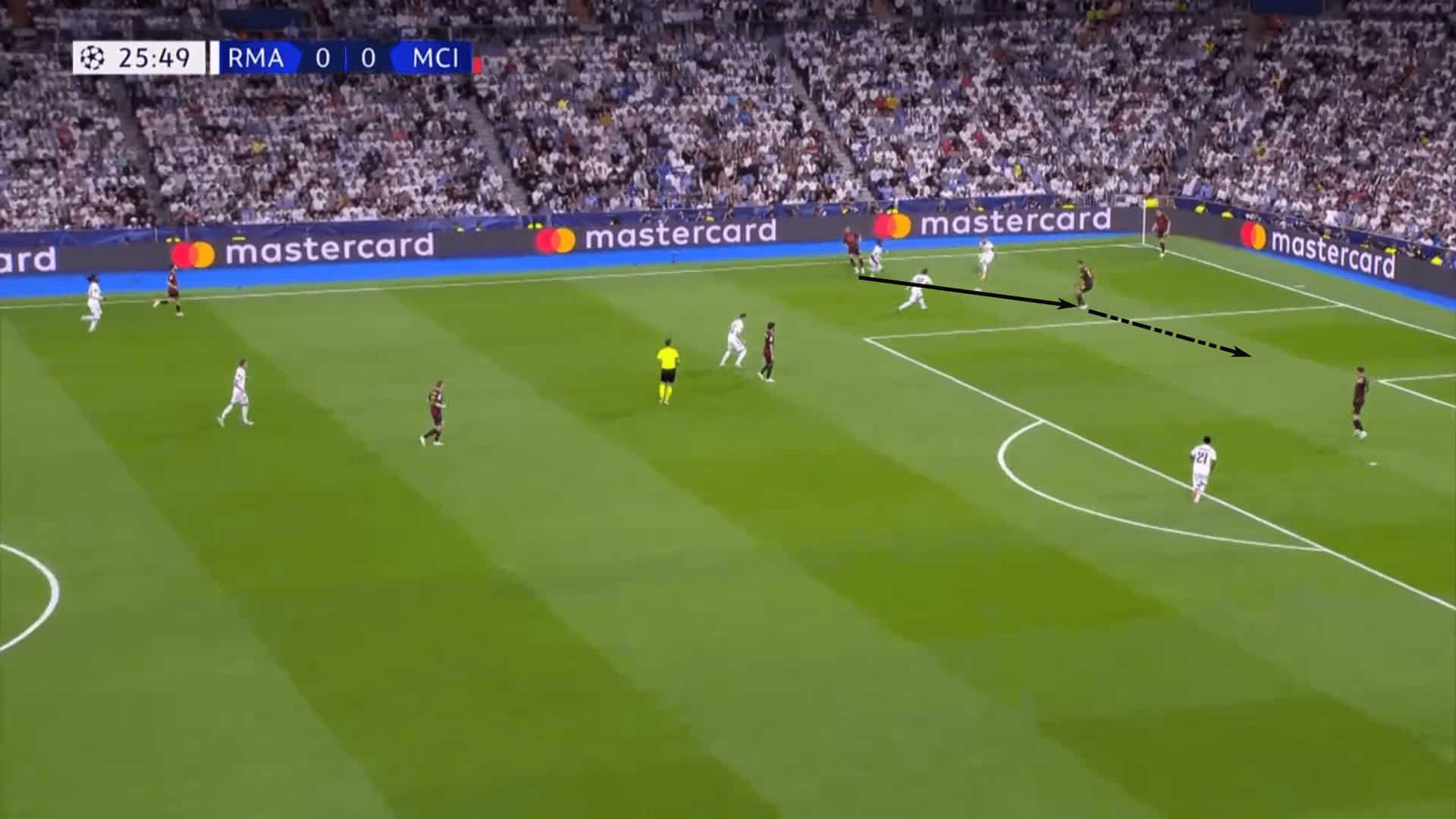

Accounting for City’s midfielders is key. De Bruyne in particular is very good at creating space for the players underneath him. His movements into the right half-space, often running behind the backline, creates space centrally for the pivots to run into. The second benefit is that it disconnects the two centre-backs. Here, it’s Matthijs de Ligt who has to follow his run into the wing.

When teams tightly mark the four Manchester City midfielders, they can funnel the Cityzens into the wings. As long as the marks remain tight, they can force City to drop the #7 or #11 into a support position. As we saw against Fulham, those hard-checking runs put City’s wide forwards into a position where they are receiving with their backs to goal and momentum is carrying them in the wrong direction.

There’s also little support underneath as well, meaning opponents can increase the pressure on the first attacker. In this case, it leads to a Fulham recovery in the midfield.

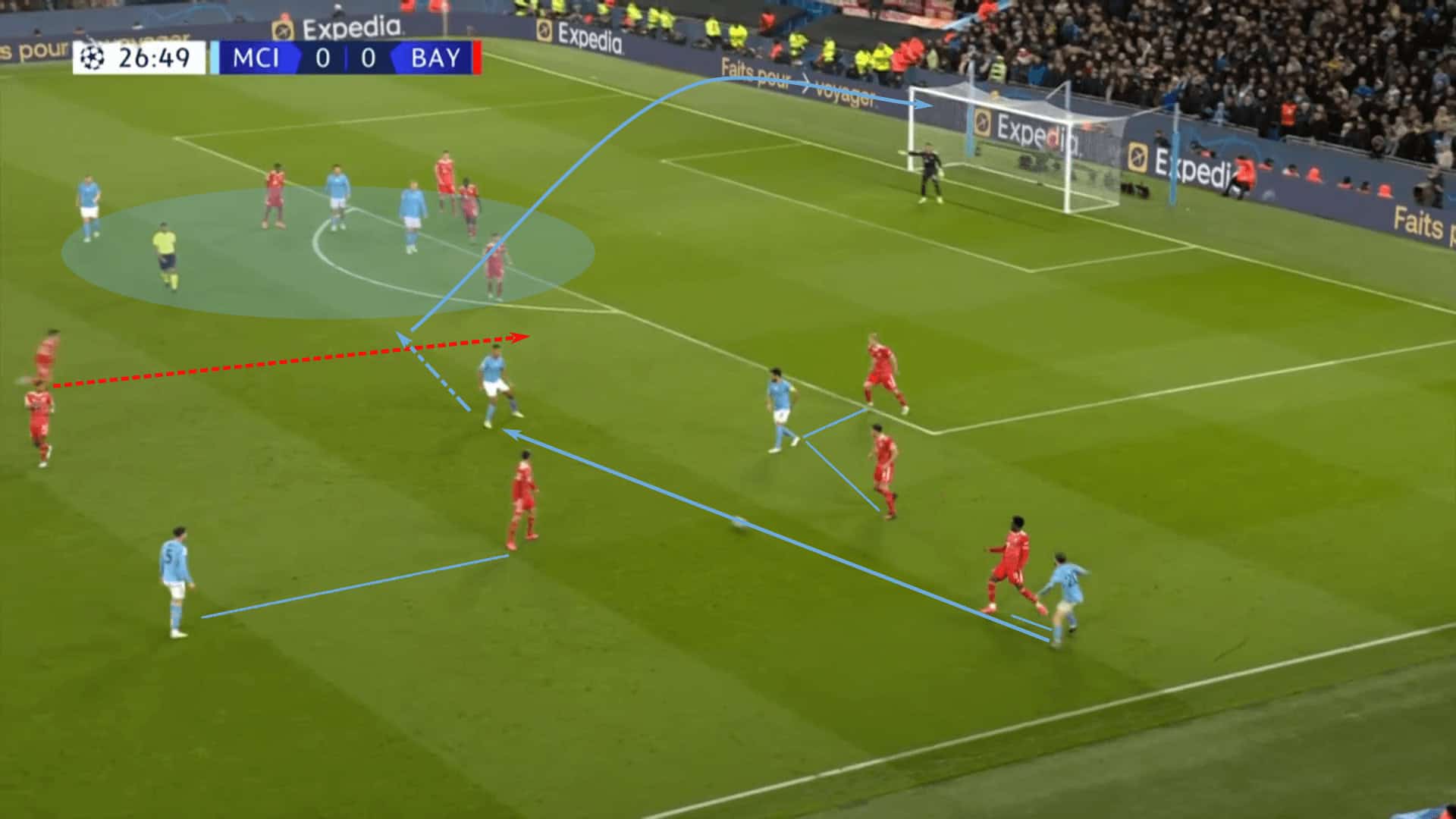

Bayern Munich uses these tactics as well. When they did have success in the high press, it typically came from funnelling City into the wings and sealing them there. Once City is pushed into the wings, it’s vital to take away the negative pass out of pressure and the nearest midfielders. Do that and you have a chance to recover the ball. That’s exactly what Bayern Munich did.

The forward pass was played into Kevin De Bruyne who, much like the Fulham example, was checking to the ball with his back to goal and momentum pushing him close to his own goal. There’s a chance he could have played backwards, but the square pass to Rodri was his way out of pressure. Bayern Munich stepped in to deflect the pass, claim the recovery and send Leroy Sané to goal against his former club. The result of the counterattack was a shot from about 15m out by Jamal Musiala, who put the ball into the outstretched legs of Dias.

Conclusion

When the first line of a team’s press takes away City’s double pivot, the implications are far-reaching. That means the midfield line can direct their attention to KDB and Gündoğan, leaving the backline to double-team Haaland and account for each of the wide forwards.

To make this task more realistic, delaying pressure until City enters the middle third removes Ederson from the equation. Without him operating as the free player along the backline, City have fewer options for ball progression. That puts the onus on the back three, especially Dias, to play through or over the press, a tactic that’s worked for the teams in this tactical analysis.

Guardiola wants opponents to engage City through the high press. From a positional standpoint, Pep’s side enjoys a clear advantage. Some opponents will instinctively look to attack Manchester City through the high press. For a club like Bayern Munich, that’s part of their game model, their identity.

However, as Real Madrid has shown, there are several benefits to dropping into a mid-block. Ultimately, Ancelotti found a way for Madrid to defend from a position of strength. By refusing to play the game according to Manchester City’s rules, Ancelotti flipped the script and forced City to adapt to the conditions presented by the Real Madrid mid-block. It also gave Madrid more security in dealing with City’s high central overload, box midfield and the two wide players. Manchester City hoped to present a problem to Real Madrid through the build-out, but it’s one Real Madrid refused to answer, instead responding with a problem for City to solve.

There’s no stopping Manchester City’s build-out. The good news is, no one has to. Search for the right answers and you won’t get caught answering Guardiola’s trick questions.

Comments