So far, the current season has not gone the way Borussia Dortmund had imagined. They only have a small chance to win the league left after being eliminated from UEFA Champions League, UEFA Europa League and the domestic DFB-Pokal.

Nevertheless after an club-intern analysis, Marco Rose will also be on the sidelines at BVB in the next season, as Managing Director Hans-Joachim Watzke confirms to ‘Sky’. When asked whether Rose would stay “one hundred percent” at Borussia Dortmund, the 62-year-old replied: “Yes, because he is doing a good job, we want continuity in the position and are satisfied with him. That’s very simple. We’ve said that often enough.”

In the summer, Rose will then be responsible for coordinating the upheaval at BVB. Several players, especially star striker Erling Haaland (21), are expected to leave the club. Today, we will take a look at Rose’s tactics during this season. In this tactical analysis, we will discover how the team suffered from injuries and why they played in multiple different formations throughout the whole campaign.

Formations

Dortmund have defended in a myriad of shapes that vary based on ball placement on the field. The nominal formations have varied from a 4–3–3, to a 4–1–2–1–2, to a 4–2–3–1, to a 3–5–2. These impact the ways that the team press and the zones that they’re able to nullify, while the other zones they might struggle in.

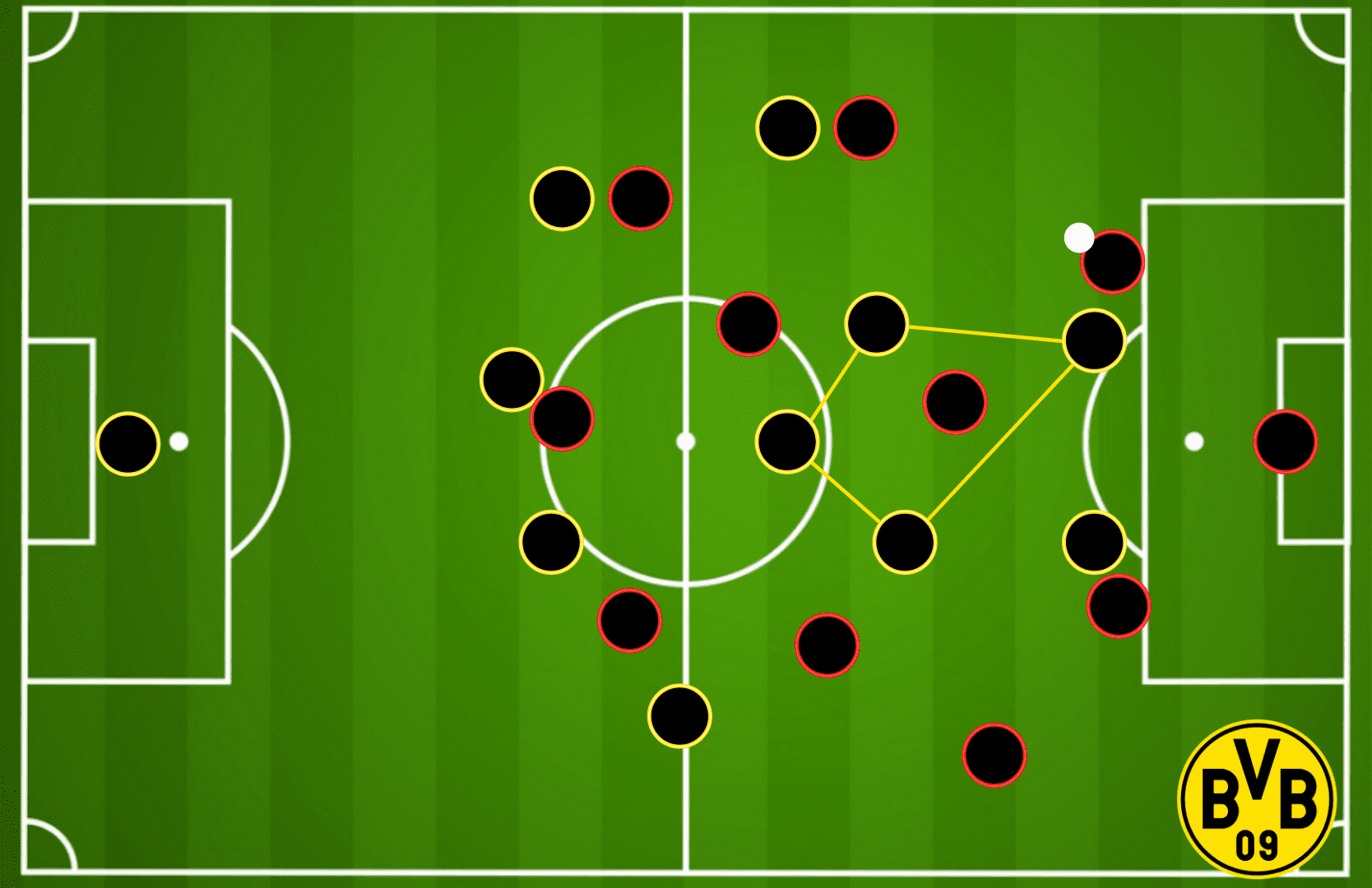

First is the 4–3–3, which has been their primary formation in most matches this season. This generally defends pretty wide, and is often used when playing against an opposition who use a back 3/5 to help counter the natural width of those formations. The midfield in this formation is usually comprised of one number 6 (Witsel/Dahoud) who act as an “anchor” in the midfield, while two 8’s press higher. This causes an immediate weakness in the build-up phase. The diamond gap between the 6, 8’s, and striker can be exploited by an opposition to receive and turn.

The 4–3–3 presses in a 4–3–3 shape and has a few main zones of excellence. First is the wide areas, where the 4–3–3 is particularly dangerous. The team presses from the inside of the pitch, to the wide areas. This creates a dangerous situation wide for the opposition where a combination of the winger, 8, and fullback can overload to win the ball back.

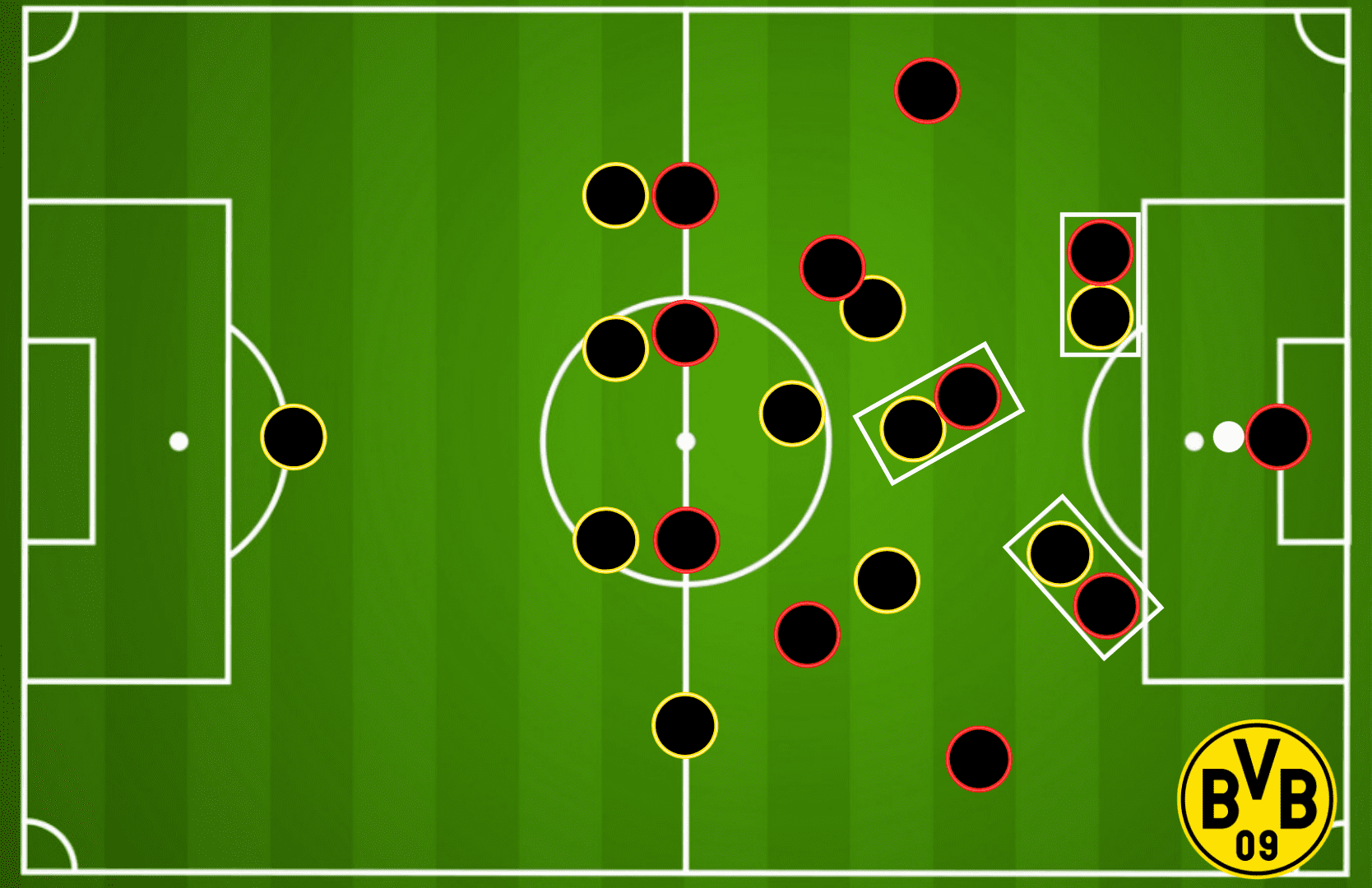

The 4-1-2-1-2 is the next formation to talk about, the one that everyone thought they were using. There’s an easy explanation to this: Rose’s 4–1-2-1-2 defends deeper with three up top as well. Generally, it has the same strengths. Those wide areas are places where striker, 8, 10, or fullback can all work to overload and win the ball. The main difference here can be seen in the opposition build-up phase, where the 10 (often Reus) will man-mark the opposition 6. A lot of teams in the Bundesliga will build with a single midfielder deep, or have the second member of their double pivot move high, making this an effective way to defend any sort of ball progression.

The 4–2–3–1 has been used sparingly this season, but it’s usages in certain scenarios have been obvious. This formation specifically defends well in the second line of progression. By creating a four man forward line, the striker can defend the two centre-backs, moving the ball wide towards one of the wide areas and preventing circulation. All that said, the differences between the two (4–3–3 and 4–2–3–1) is pretty negligible. The 3–5–2 is the final formation used, and it’s mostly been used to account for missing players in attack like Haaland and Reus (see Gladbach match). Defensively it’s a good matchup in a man-oriented setup vs. another 3/5 back side, but the wide areas get overloaded here more frequently.

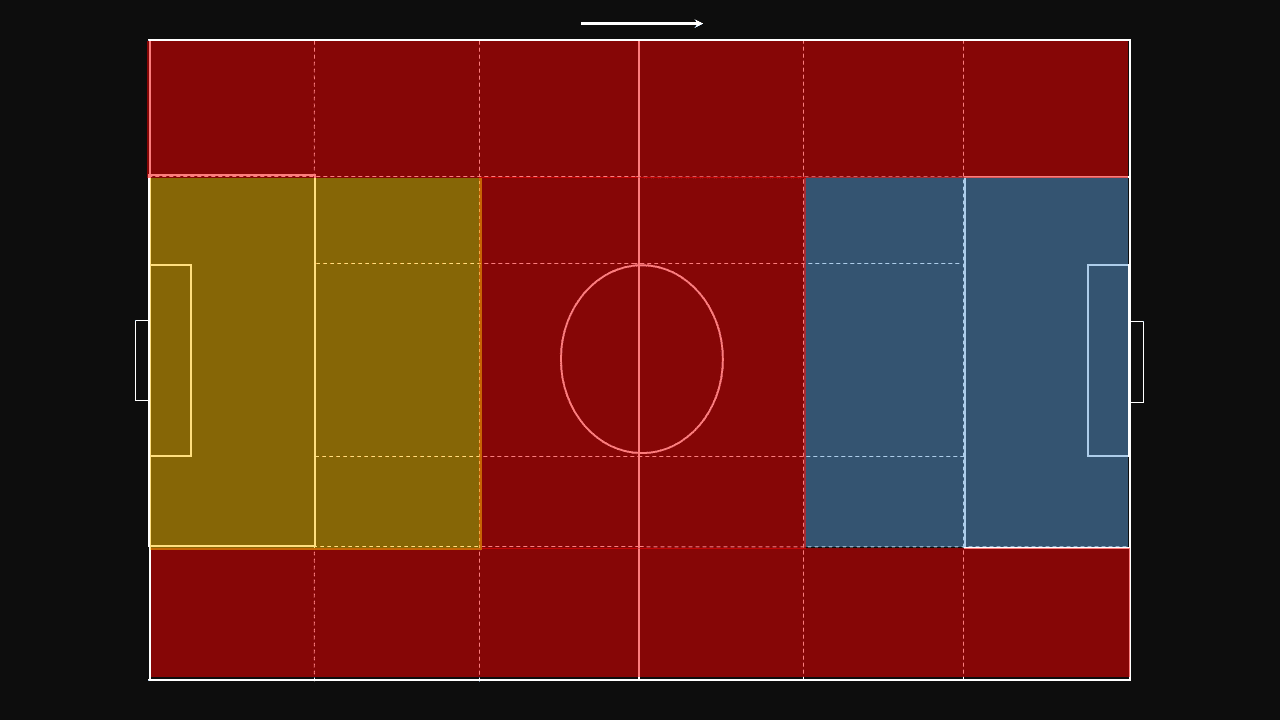

Defending phase

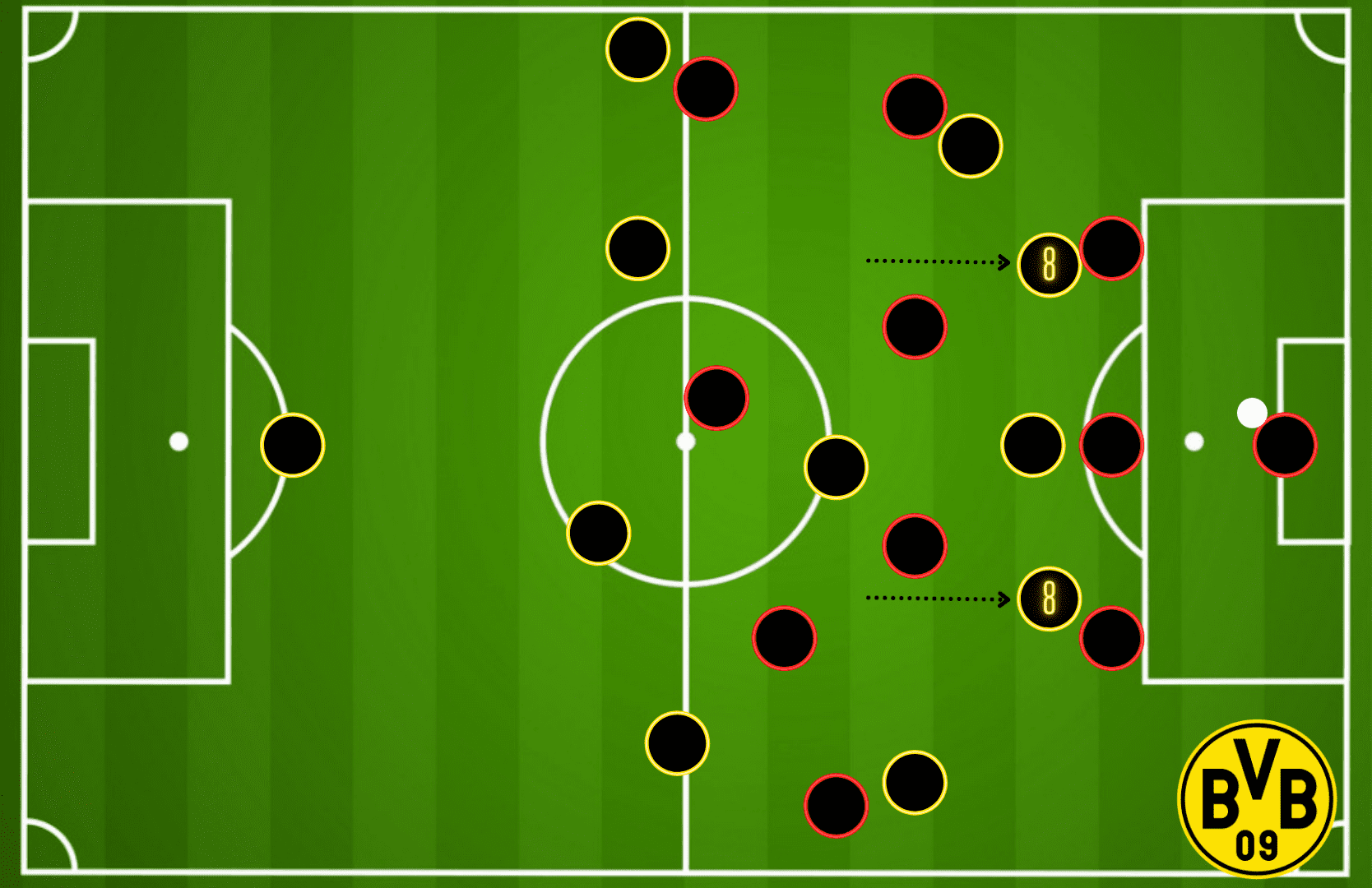

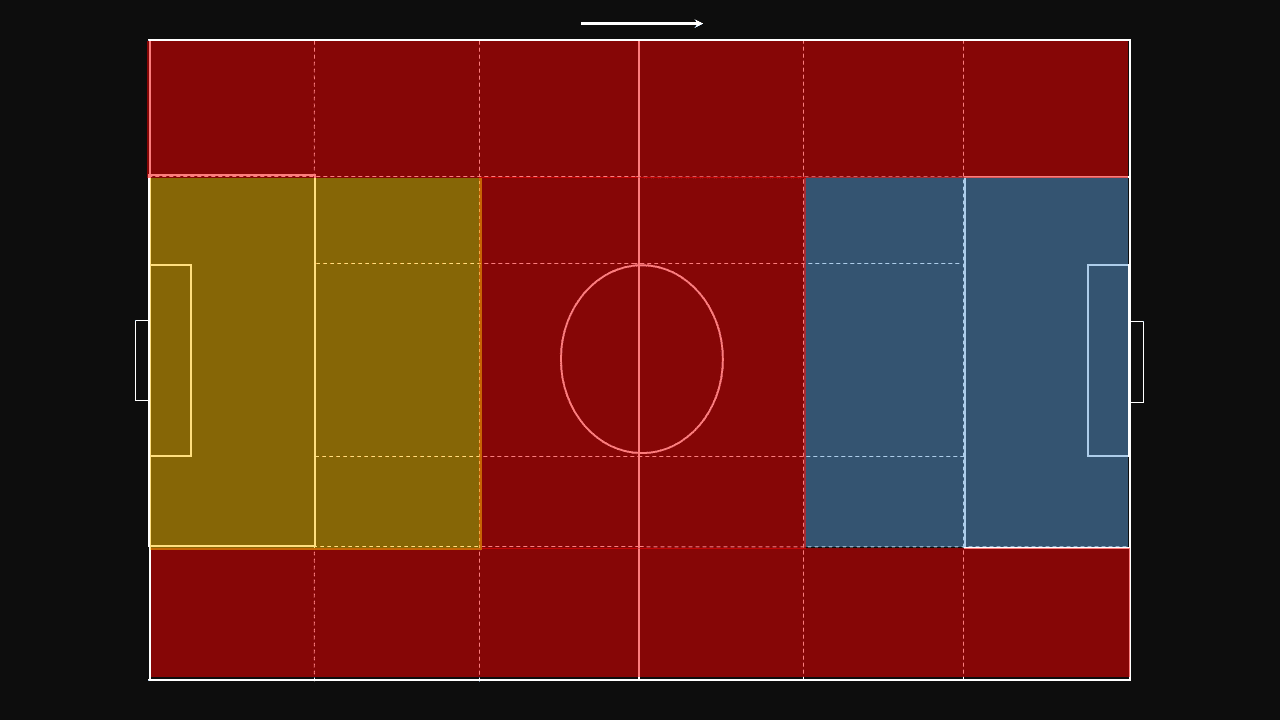

Vastly more important than simply formations used is the principles conveyed to the players by Rose. From the front end of the attack, players are told to repress lost balls quickly to regain possession and to double down and isolate attackers. This is particularly common in the wide areas of the pitch, and in the centre of the pitch after the first midfield line is broken. These can be defined somewhat by zones, seen below. Although it’s not an exact science in this case, these red zones (intense pressing) are specific places where winning the ball is prioritized, while the blue (drop off) and yellow (weaker/situational) are more focused on box defence and space/progression defence respectively.

It all starts with pressing angles and a supporting press, one of the things that Haaland is excellent at because of his size. He is able to directing the opposition to certain sides of the pitch simply with body shape. He rarely is instructed to press hard, but his body shape forces a pass to one direction or the other. His movement acts as a pressing trigger for the players around him, who are able to anticipate the next pass and press before or as the pass is made, rather than when it arrives.

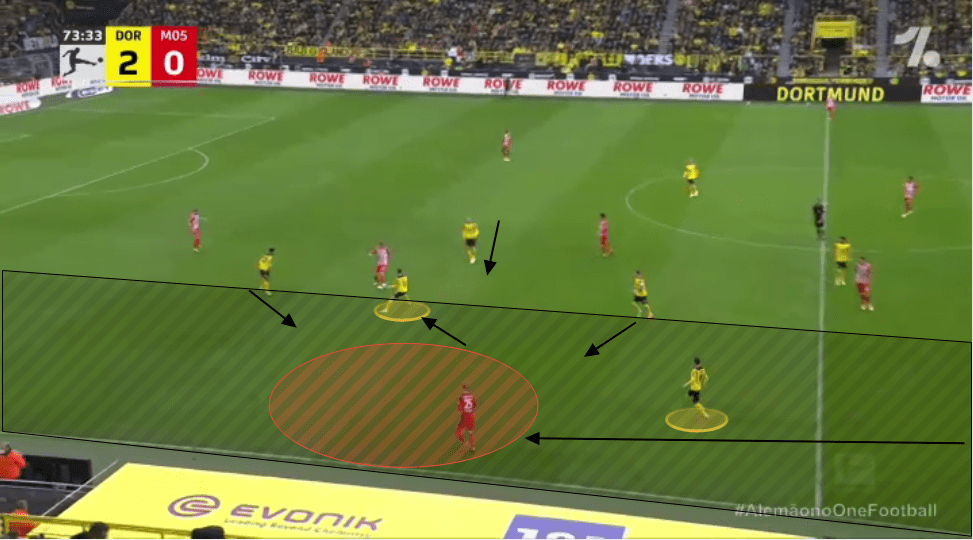

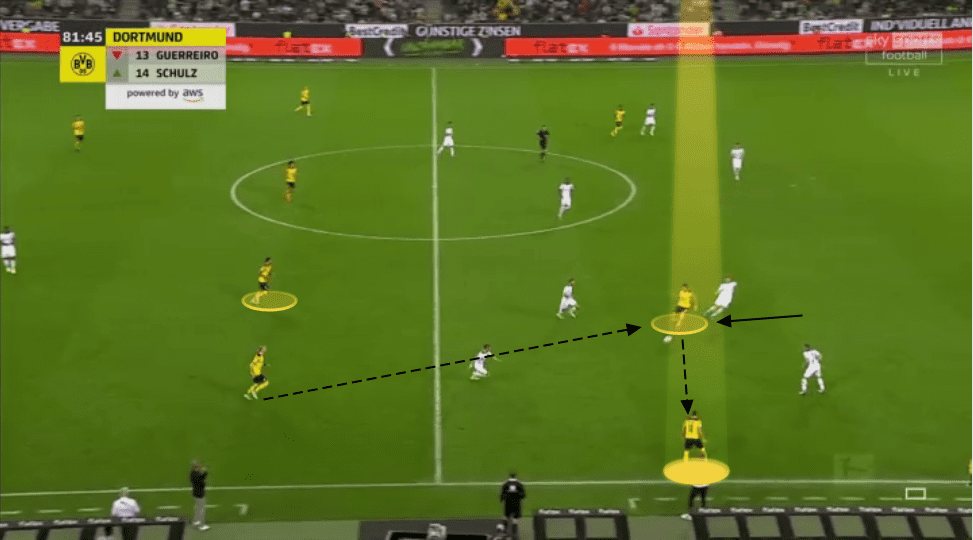

The situation below shows an example of how Haaland is able to direct the opposition’s actions a certain way, and also conveys the next piece of this: pressing traps.

Once the ball is played wide, it acts as a trigger for Schulz to press. Pongračić has already begun to slide to cover his gap, and in the end, Mainz had nowhere to play the ball. It becomes more and more apparent that these pressing traps are BVB’s way to win the ball, and can be seen across all their formations.

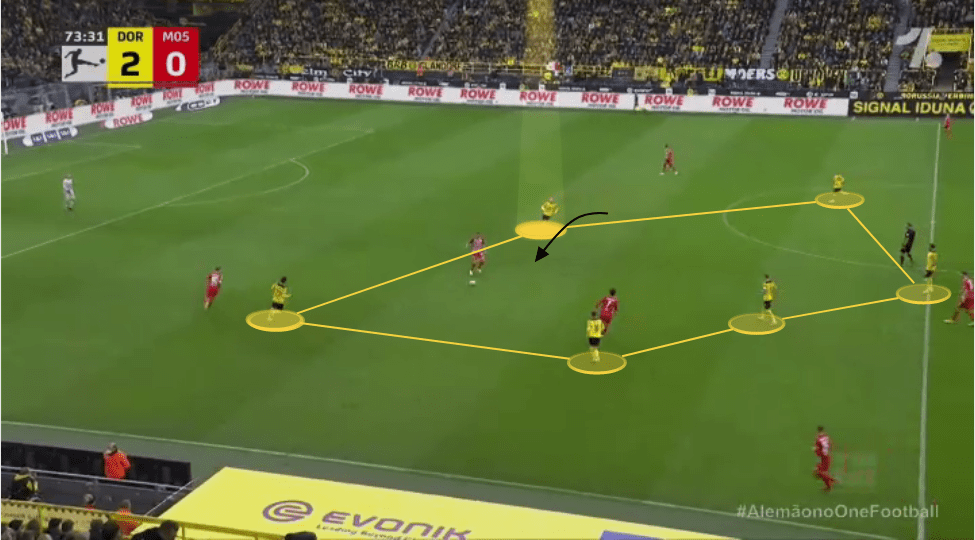

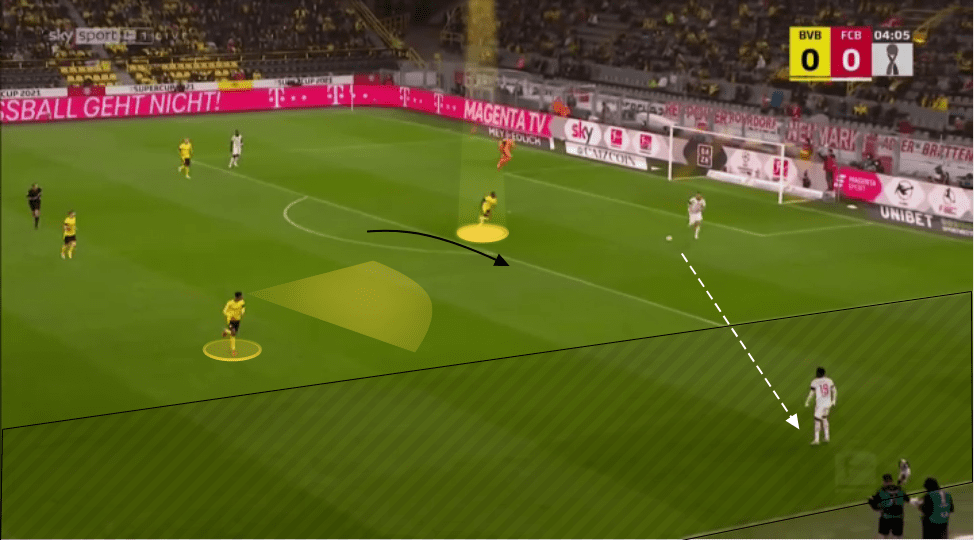

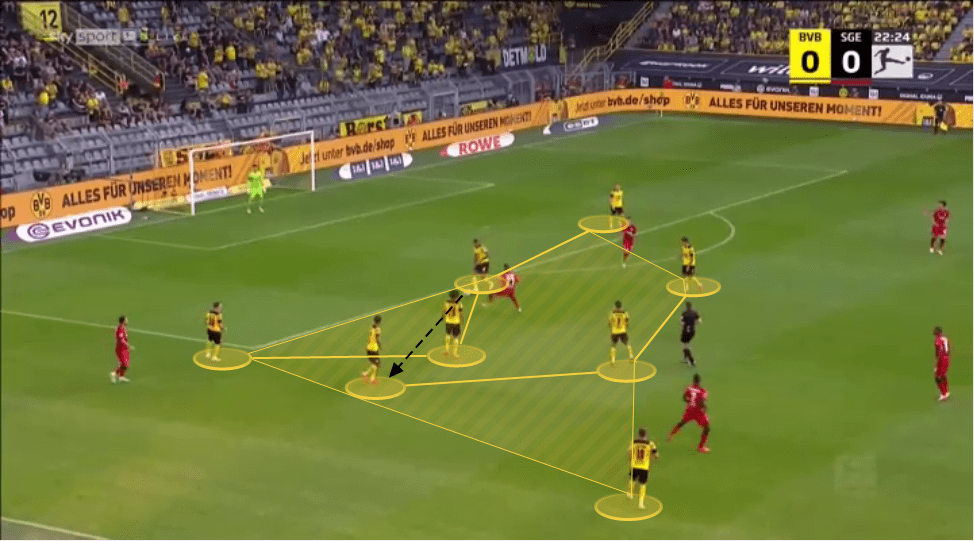

This specific situation was against Bayern, where Dortmund were using the 4–1-2-1-2 to defend. Moukoko’s body shape guides the CB wide, which triggers Bellingham’s press.

Reyna and Reus combine to mark the pivot, and the ball is won after Bayern run out of passing options. A slight tangent here: it’s likely the ball could have been won easier if Moukoko had pressed harder, or continued to shadow Süle, but it worked still.

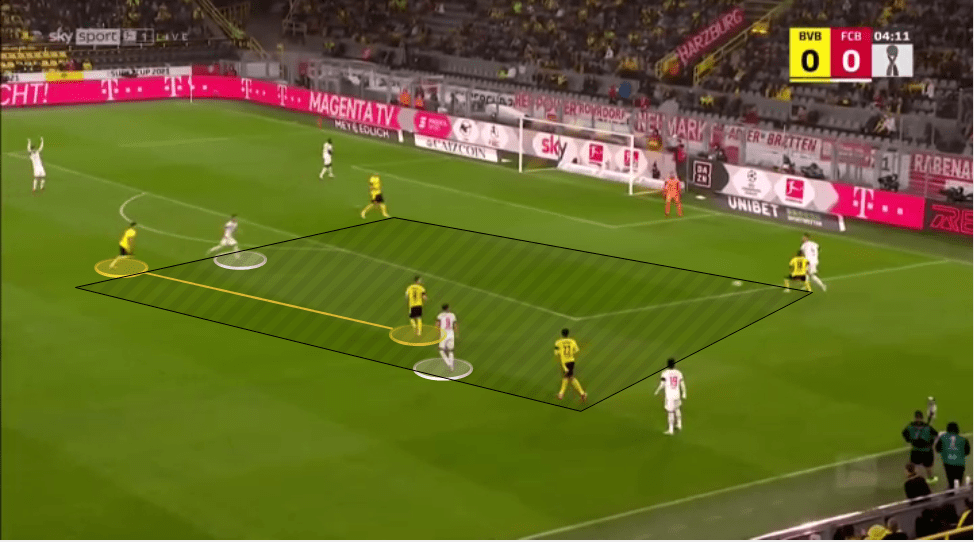

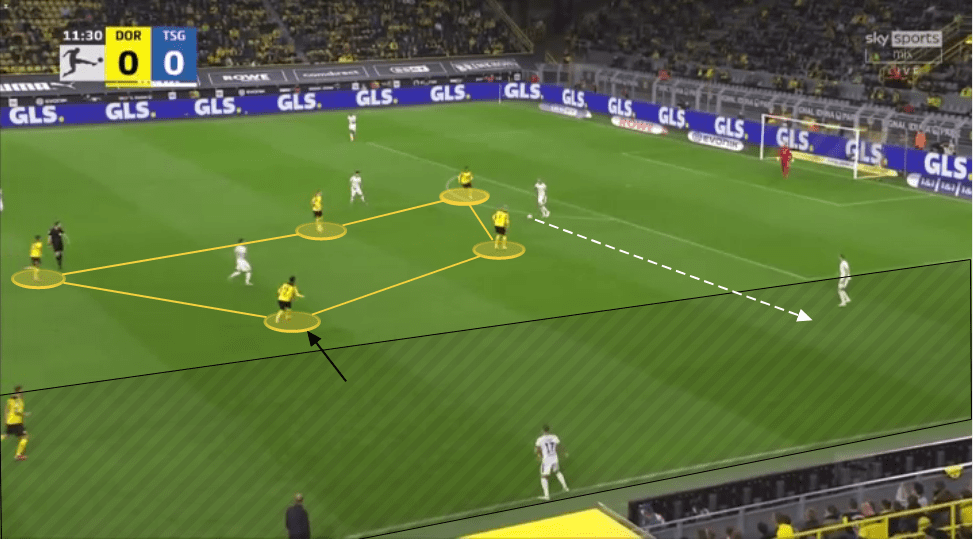

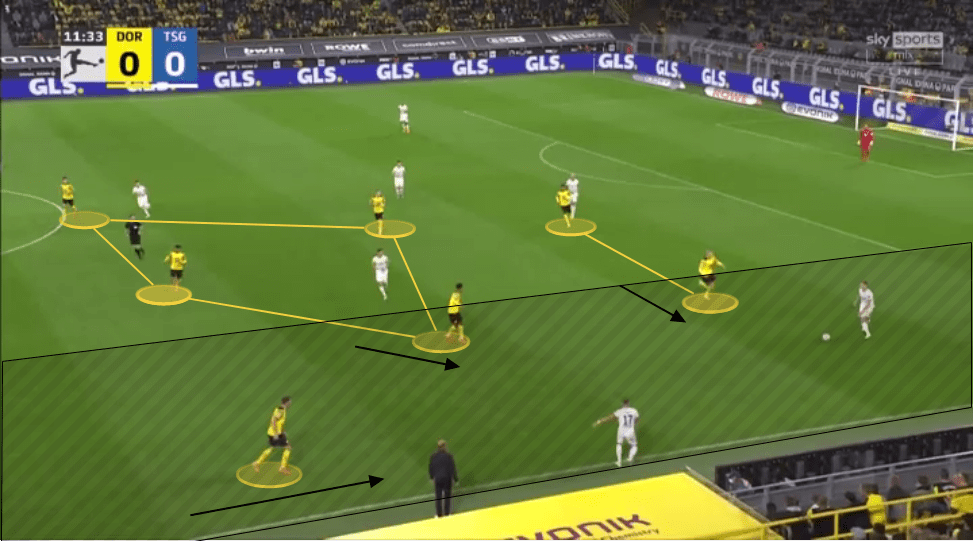

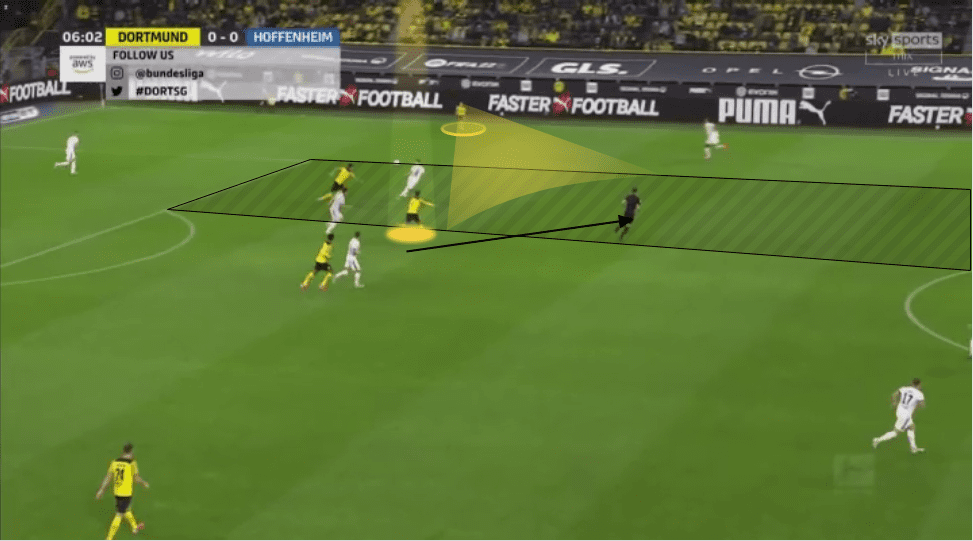

Another variation on these pressing traps can be seen against Hoffenheim, where Haaland passively removes the option through the middle, forcing the CB to pick as a side as he drives forward. After that is done, Bellingham and Meunier wait and watch to see if a pass will be made as Haaland pressures from behind. Collectively, all options are closed down (or made useless) and it forces a long ball that is covered comfortably by the backline.

An important piece of this Hoffenheim clip is not just the pressing trap, but also the way that the forwards are able to press somewhat softly. The standard rule of thumb is that if using a high line, you must secure it with an intense (and cohesive) press from the front. Once that first line of press is broken, you go into a regroup and dropping phase where teams are often most vulnerable. In Dortmund’s case, they’re able to remove the importance of the press because of Kobel. Throughout the season he’s demonstrated immense confidence coming off his line and this allows a passive press, with a high line, which would normally get exploited with a keeper like Bürki.

This section is missing one thing though, what happens when the team gets pushed back deeper? These traps aren’t always executed well, and that’s where mid-block and low-block defence comes into play.

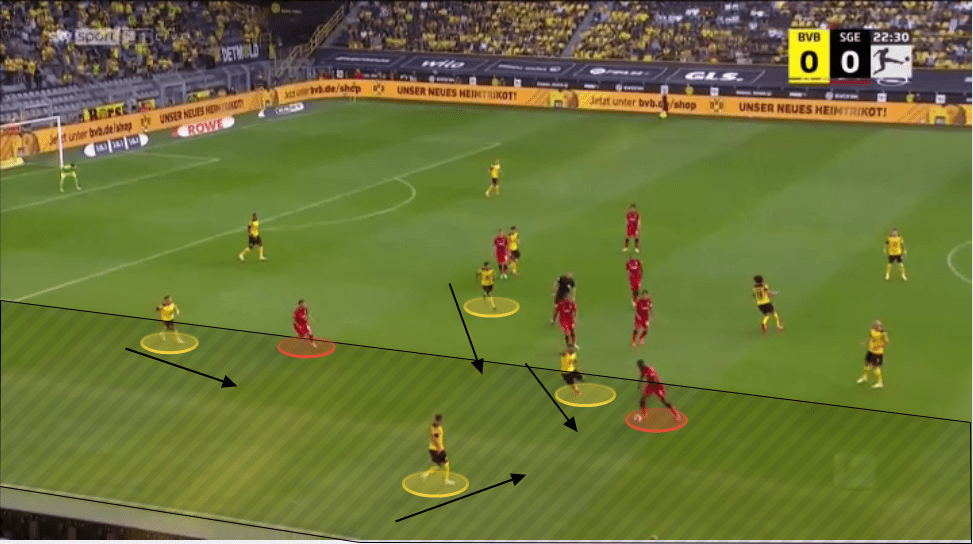

Each one of the previously mentioned formations has some way that it settles into a slightly different shape, for example, the 4–3–3 almost looks like a 4–5–1 at times, where both wingers drop deep. At other times, it looks like a 4–4–2, where the ball-side winger drops deep to support his fullback. This is where “formations” become a bit muddied and it’s important to focus on the principles.

‘Fullbacks are the winger’s job’ is the first point worth picking out. Especially in the high 4–3–3, the ball-side winger is expected to take care of the opposition fullback. If he begins to overlap, the water becomes less clear and the “defensive basics” begin to come into play. Things like passing off a runner to a teammate, covering vacated space and other things are all apparent. I don’t generally find that low-blocks vary their instructions per player, but more so the overall ideas behind it.

One of those team ideas is the idea of isolating a player through pressing angles and winning the ball back with intense pressing based on certain triggers. For example: intense pressure from the midfielders when a line-breaking pass is played, or similarly in the wide zones when a player is isolated. There are very infrequent situations where BVB are back in their box defending the shot, shuffling from side to side.

Miscellaneous defensive things and changes by opposition

Some more position-specific things can vary from opposition to the formation, or are constant throughout. One of those constants is the behaviour of the centre-backs, who often man-mark the opposition forwards. This has resulted in multiple instances of balls played behind the defensive line where a defender (or a few) are caught out of place because they trailed the opposition forward like a duckling with its mother.

One of these variations can be seen within the 4–3–3 specifically. Often the 8’s will step up even higher than the wingers, and press the outside centre-backs against a 3 back formation.

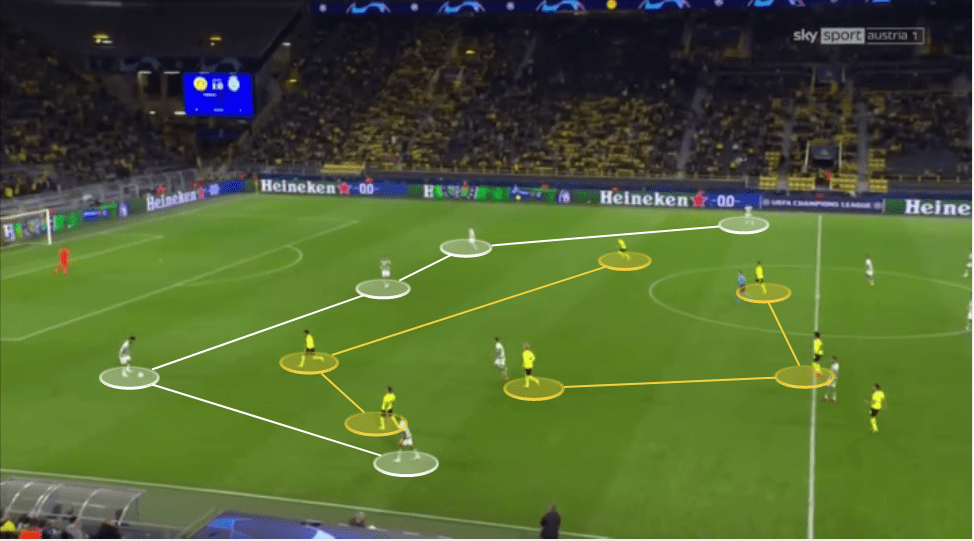

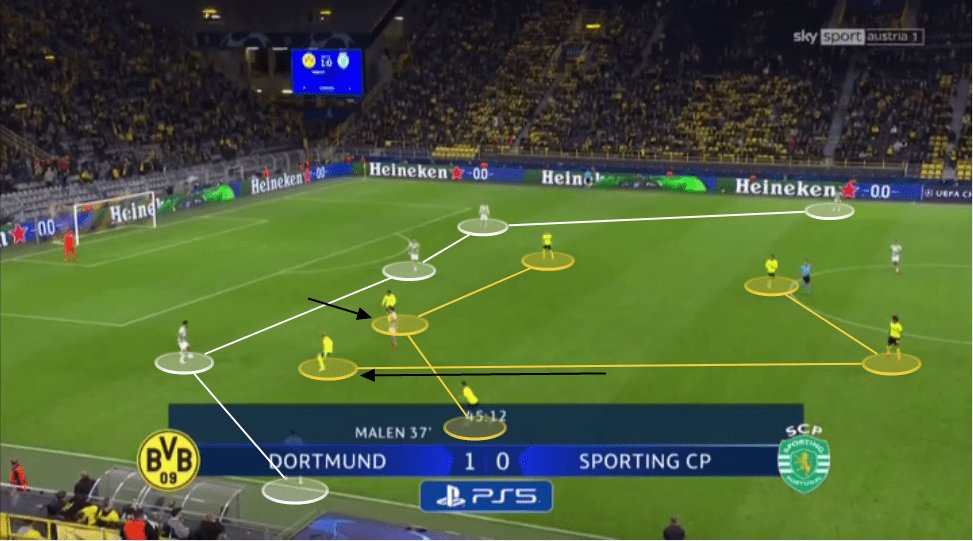

In this specific example below, Dortmund are using a slightly asymmetric 4–3–3, where Bellingham is slightly deeper than Brandt who somewhat interchanges with Hazard to defend that left side of the field. This was likely done as a way to match up with Sporting’s back 5, so that they could efficiently press in a man-oriented fashion.

Important to note: the way Malen first covers the CB, then covers Brandt’s man – emphasis on preventing central progression.

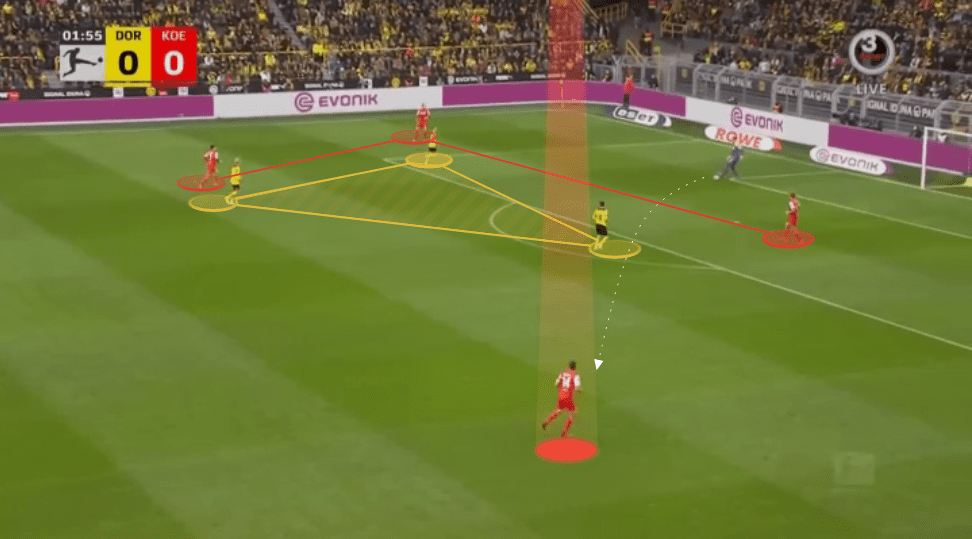

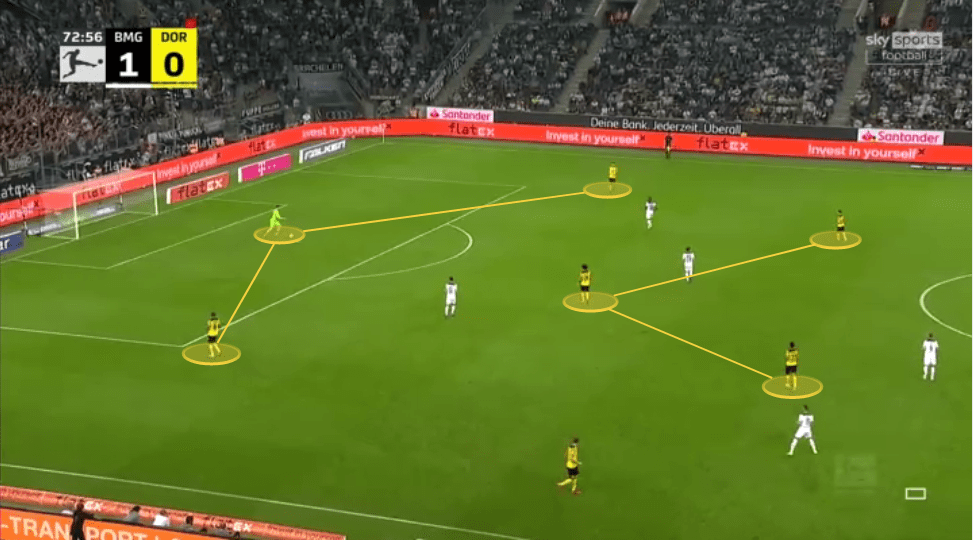

Another obvious defensive change is within the 3–5–2 used. While BVB will sometimes find themselves man-marking the CBs and 6 in a 4-1-2-1-2, this was more obviously intentional against Köln. This was likely due to Horn’s inability to play a lofted ball to his entirely unmarked full-backs. This clip also demonstrates the way that forwards fill in each other’s gaps to ensure that passes are covered.

Watch Reus specifically as Brandt moves to pressure the RCB deep. He moves to mark the 6, taking Brandt’s spot. It’s a small tidbit, but it is important coaching that ensures the running is meaningful. This clip also illustrates an important point I’ve somewhat neglected which is that if the press is broken, the attempted narrowness of their pressing opens acres of space wide where a strong opposition is able to play out and stretch them.

The failures of these two principles were on display against Ajax. While BVB struggled to press well, resulting in frequently wasteful running, Ajax’s ability to play through the press and play expansively was immensely difficult for them to handle across both matches.

Transitions

As seen in a majority of these previously mentioned principles, Dortmund’s mentality is driven on creating dangerous transitions that provides an opportunity for their players to thrive. Haaland and Malen are integral to this, as they’re both very good at finding and making runs behind the defensive line. Unlike previous seasons though, Dortmund have become drastically less transition-dependent.

Defence to attack

If executed properly, the defensive concepts discussed before will cause a lot of transition moments because of the locations the balls are won. This means that the “first action” immediately after winning the ball is important. Assuming the ball was won through one of the preferred methods, it is likely that the player on the ball will have a multitude of short-range passing options right in front of him. This poses the first question for the ball-winner though. If the ball is taken off of a midfielder, it is more likely that the opposition defensive line is exposed, and a counter will be more dangerous at that moment. If the ball is won within their own half, BVB will be more likely to play the ball forward in general.

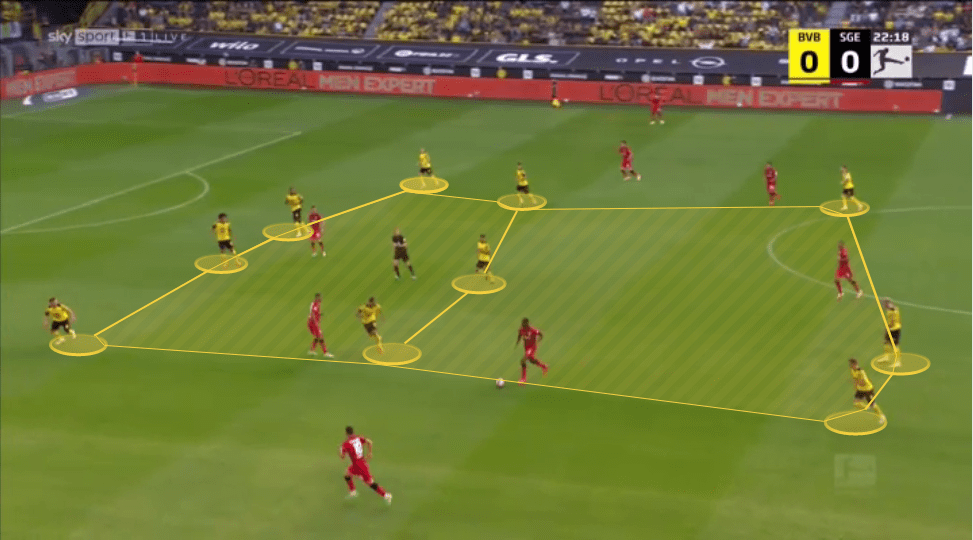

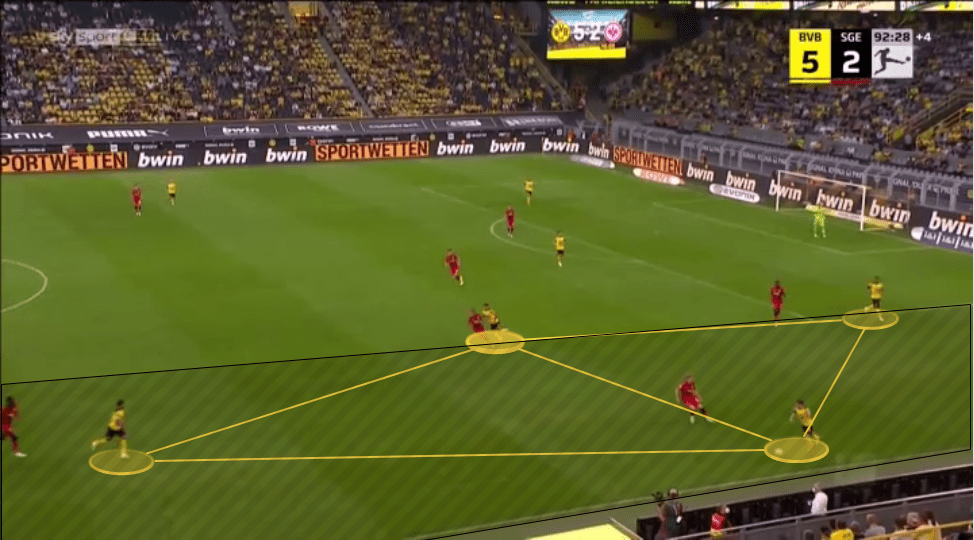

On the flip side, if the ball is won in the opposition half or in the central 1/3, the ball is more often recycled backwards to the defenders who are able to circulate before choosing a new direction of attack. If none of these options before are mentioned, the next option is “how can I combine to build forward?” As mentioned previously, the ball-winner will be presented with a multitude of options in front of him to play with. Choosing a forward option and making a run after playing the ball implies an immediate attack forward. An example of this can be seen below: This specific situation is a great example for a few things. First, is keeping play tight to win the ball back and isolate the Frankfurt forwards.

Second is the forward-first mentality from Akanji, who immediately finds a midfield option in front of him without taking too much time to think about it.

Finally, it is a great example of how players impact their game model. Bellingham and Passlack’s work to win the ball back the second time, before it lands at Haaland’s pace whose immense pace is able to isolate the Frankfurt defenders.

One of the more in-depth pieces of each defensive formation is that each defensive shape alters the rest defence of the opposition, and more importantly, the positioning of BVB’s forwards. For example, in a 4–3–3, Haaland can often be isolated up top as the wingers track back. This makes transitions slightly more difficult because he lacks the support in Reus and Passlack seen in the last clip. One final piece of the defence to attack section is the way that Haaland acted as an outlet. One of the important parts of ‘crisis’ defending, once the opposition is in the final 1/3, is to have an outlet. By having a dominant aerial and physical threat up top, BVB are able to clear their lines and move forward. This is certainly an area of improvement for him though, as he sometimes lacks the patience to wait for a pass, and struggles when pressed from the front at times.

Attack to defence

Known for their counter-pressing in Germany, BVB is no different to this idea. Immediately after losing the ball in most situations, the nearest man will frequently press hard. If isolated, a second man will often come and assist the press. While this counter-press is happening, the rest of the team either works to get back into their positions or look to aid in the counter-press. There is never a still body after losing the ball, whether this is the CBs moving to mark forwards, or wingers looking to repress.

This also brings back the graphic from before that shows the level of the press by zone. Particularly when the opposition gets into a threatening position in the central areas, the primary focus becomes box defending and attempting to remove a dangerous shooting position.

The yellow zone is mostly situational, at times like in the Hoffenheim clip, the goal is to use body shape to guide opposition. In other clips, like against 1.FC Köln, pressing is intense even in the opposition 1/3. Most importantly are the wide zones, where the sidelines act as an additional defender and constraint to the opposition. This is why pressure is more intense here, they’re confined to a 180° view of the field.

These red pressure zones are also important because they’re directly derivative of the short passing mentioned a few times already. By keeping passes short, and combining with nearby teammates, the distance that you have to cover to repress the ball is drastically shorter.

Attacking

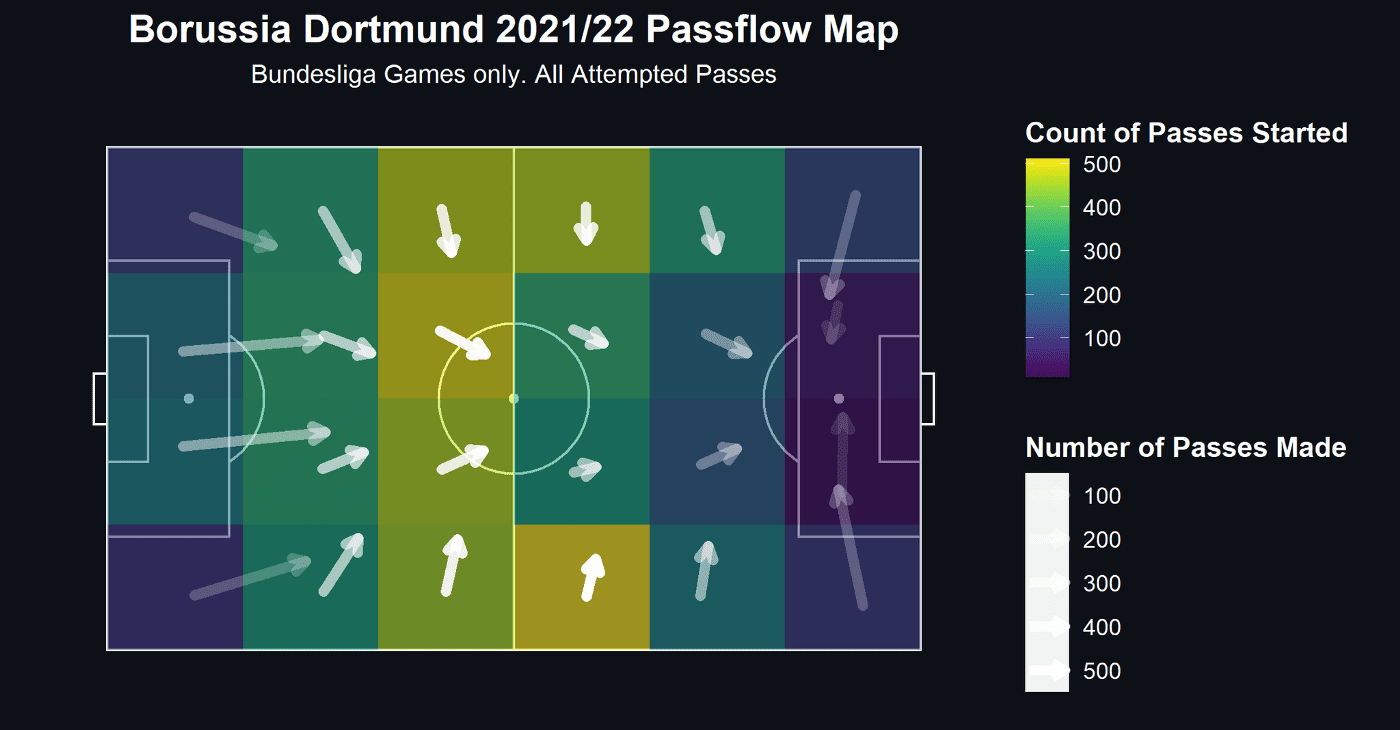

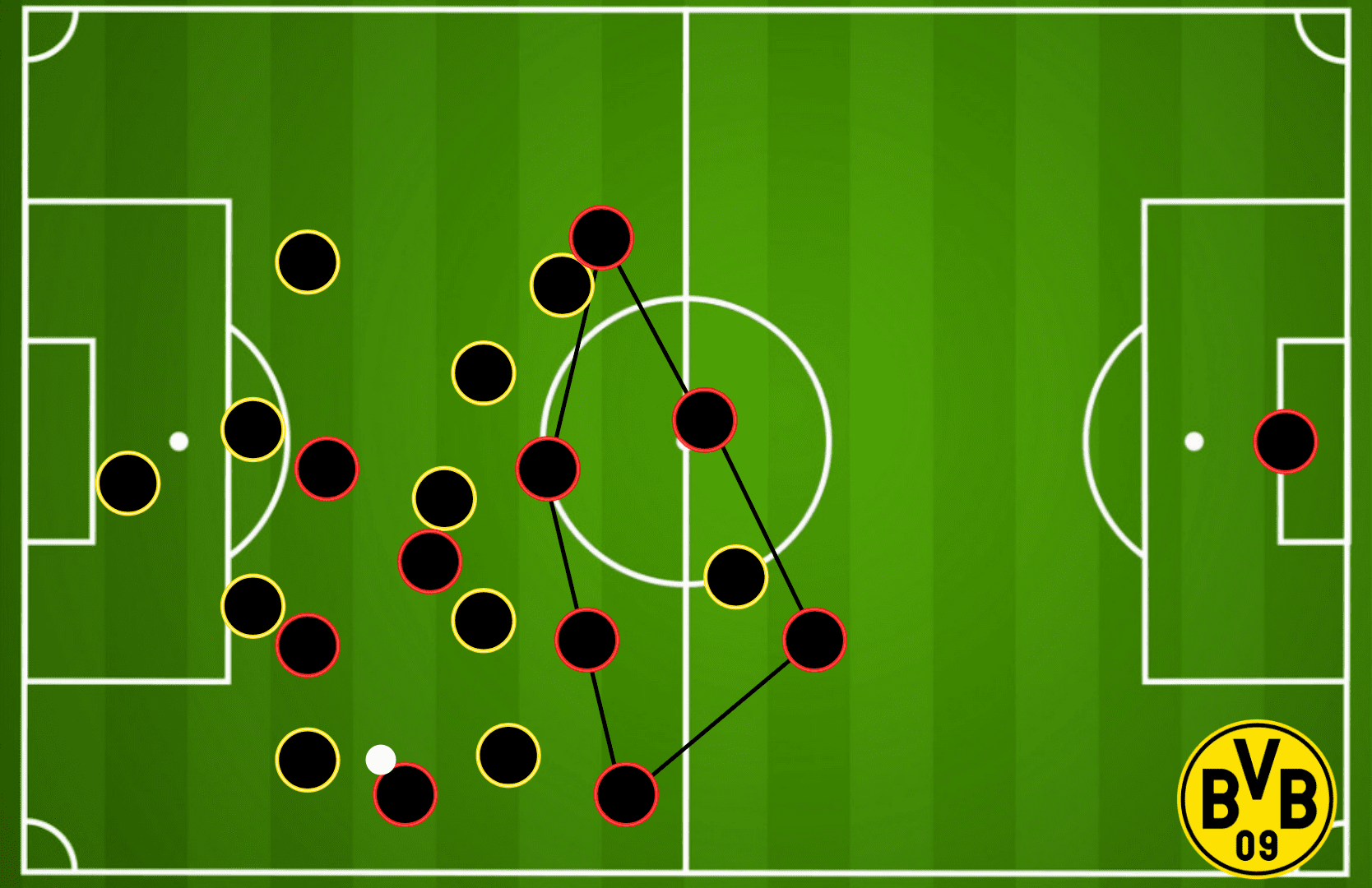

Starting from the back, Dortmund have used the same build-up structure across the board in their build-up, even with variance in shapes. When deepest, like on goal-kicks, it resembles almost a 3–3 shape, where Kobel becomes a part of that back line. He is an adequate passer, does well under pressure, and creates a third man for the opposition to worry about in the defensive line.

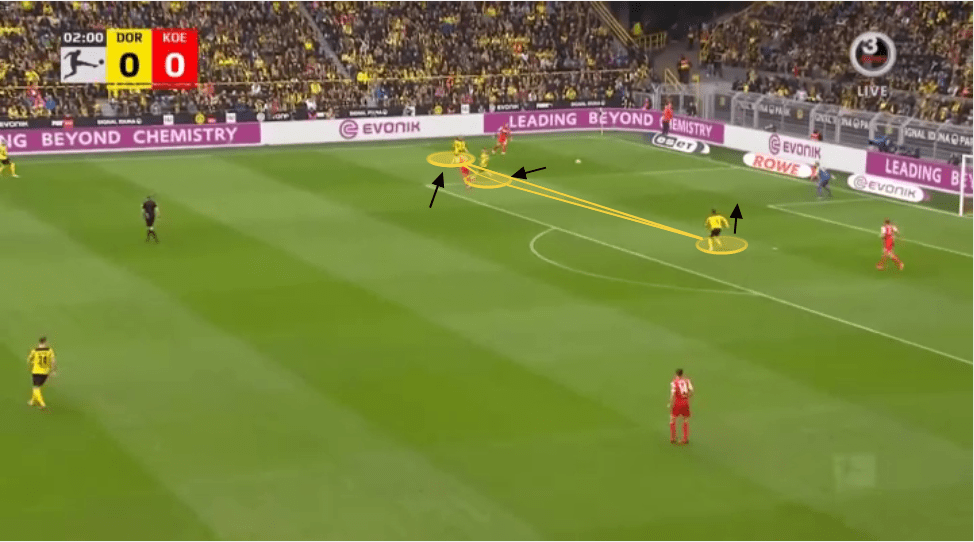

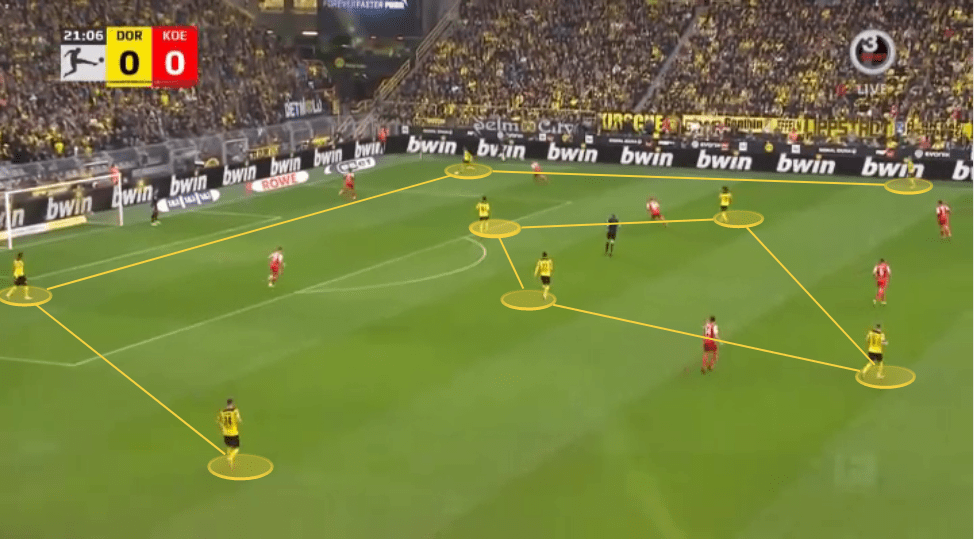

Despite a myriad of formations being used, this shape stays constant throughout, at least at a lot of moments. For example, against Köln, BVB used a 3–5–2 defensive shape, while still creating a shape that looks very similar to the diamond in build-up.

This was accomplished through Hummels staying in midfield, and the wingbacks staying in their natural positions. Hummels in this instance steps out of the defensive line and into the midfield, similar to the exact behaviour a 6 would make.

Build-up principles

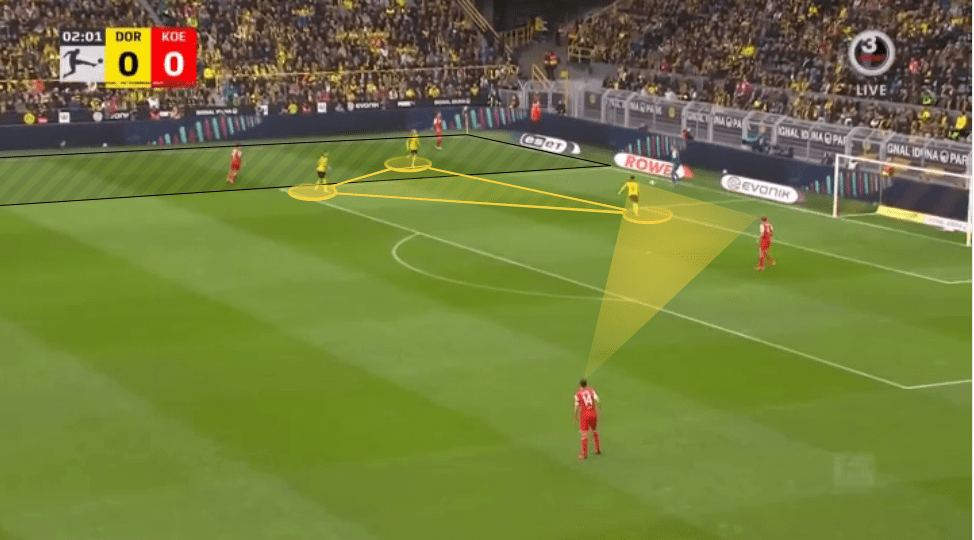

As we progress slightly higher up the field, more players come into play than just the mentioned 3–3 build-up shape. First is the two midfielders, who float in the half-spaces as a quick vertical option. For the most part, they rarely receive the ball, but they can be used in combination with the 6 and opposite 8 to create midfield rotations that create space to receive.

Although the pass wasn’t great in the end, Dahoud was able to play a ball forward, facing forward. Some of these rotations, like the one seen above, create opportunities for the midfielder who rotates into the space to receive facing forward. Against a man-oriented opposition, like Hoffenheim, this is an immediately dangerous situation because it means the press has failed.

Dortmund are also able to progress similarly vs. other man-marking opposition through wide combination play. These patterns are designed so that when a player receives, they’re receiving the ball in a threatening situation. An example of this can be seen below, against another man-oriented side, Frankfurt.

One of the most important principles to these patterns is something that Marić himself has spoken about in a few interviews. Players are meant to have possible solutions at their fingertips, rather than being handed the solution without thinking:

“For me, [tactics are] definitely not a specific match plan with pre-determined sequences, situations, or moves. In my mind, tactics describe the sum of a team’s decisions about how they’re going to solve a particular situation. Tactics are, for instance, a player recognizing where and how he is being closed down but still managing to still see an available teammate. And also how that team-mate has positioned himself in such a way to remain available, and then to receive a pass in the right place at the right moment. Ultimately, it’s a very simple process: on the pitch, you’re either protecting the ball, demanding the ball, or creating space. There is nothing else. Tactics is the mutual resolving of a situation through these actions by means of predefined playing philosophies, which correspond with the players’ abilities and their understanding of the game.”

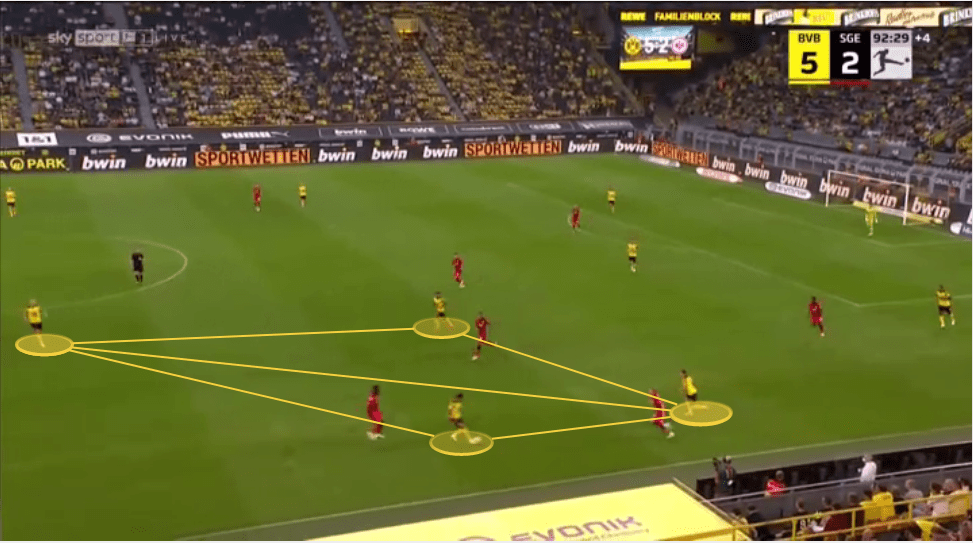

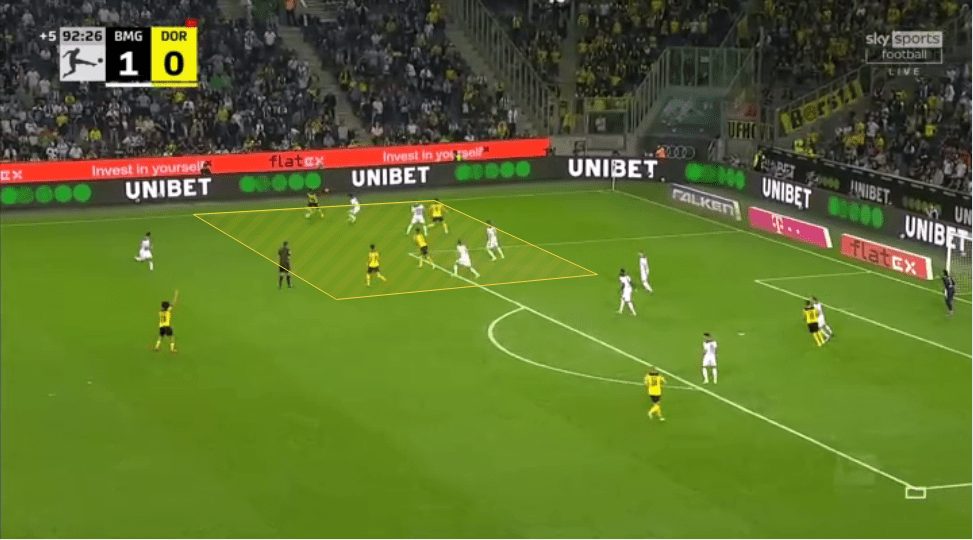

Each one of these patterns is not meant to be an automatism, as much as they’re meant to be a “what-if” relationship between players and the ball carrier as seen in the example below. While this specific combination didn’t quite work out, it showed us the myriad of options posed to each player as they received based on common patterns: Forward looking for space to receive. Winger is wide and able to receive, body shape so he’s able to act as a ‘wall’ or a man where a pass can be bounced off of. Centre-mid provides an option to turn out and switch play.

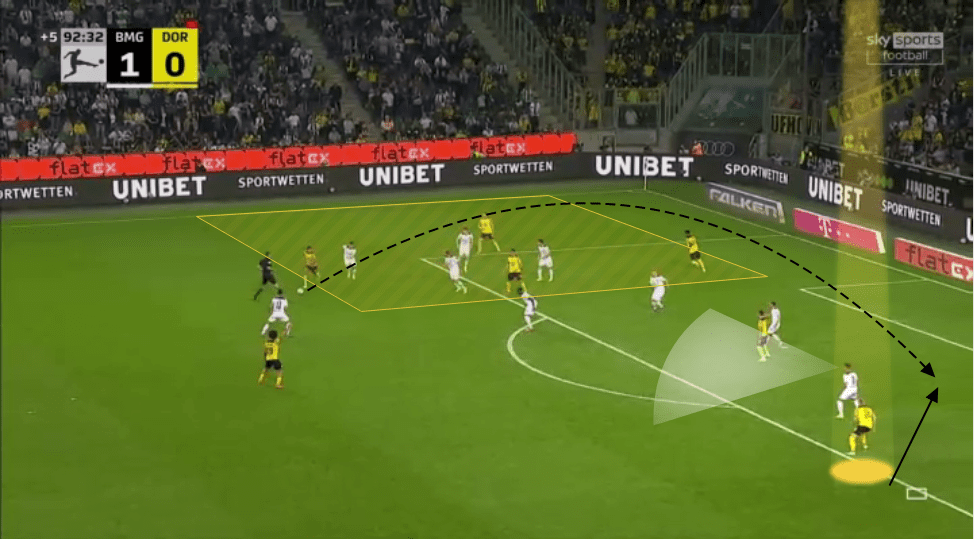

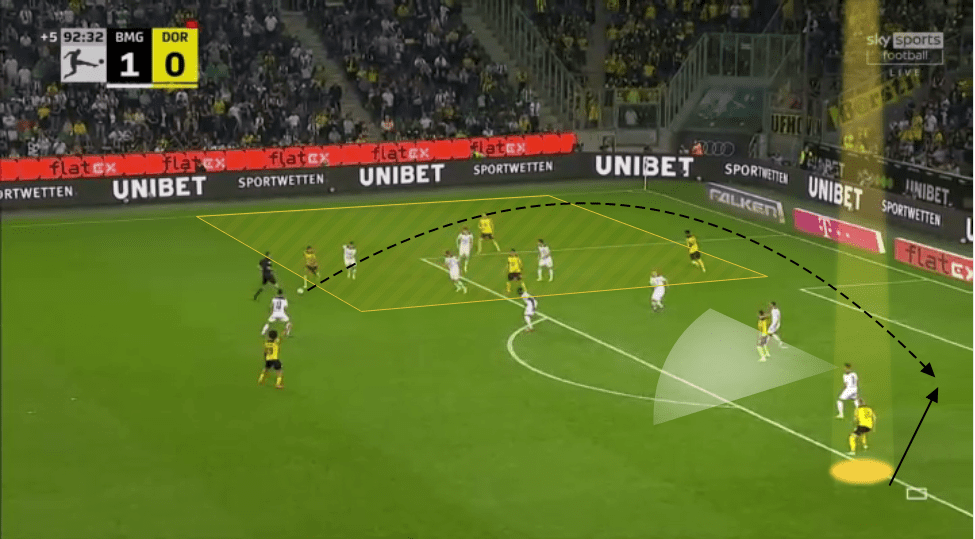

As each player received, he was presented with situations where he knew a teammate would be and being able to resolve the situation in front of him. Anyways, the pressing shape/trap from Gladbach was perfect here.

Chance creation

First is the idea of keeping play in tight spaces. I’m beating a dead horse by now, but in the final 1/3 especially, BVB keep play roughly in one zone to create chances for counter-pressing. This isn’t all defensive though. If you’re a team like BVB, it’s a pretty good bet that your players are good enough to play comfortably in these tight spaces.

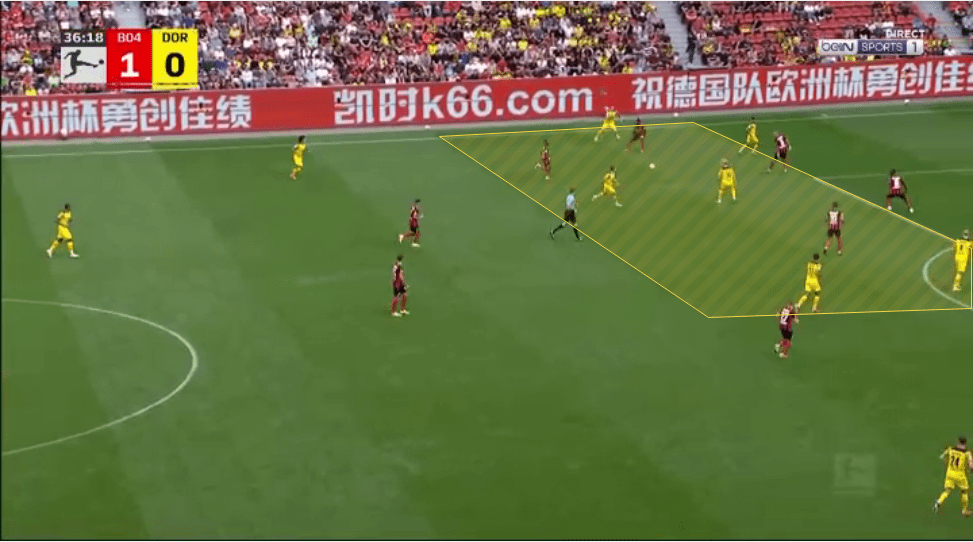

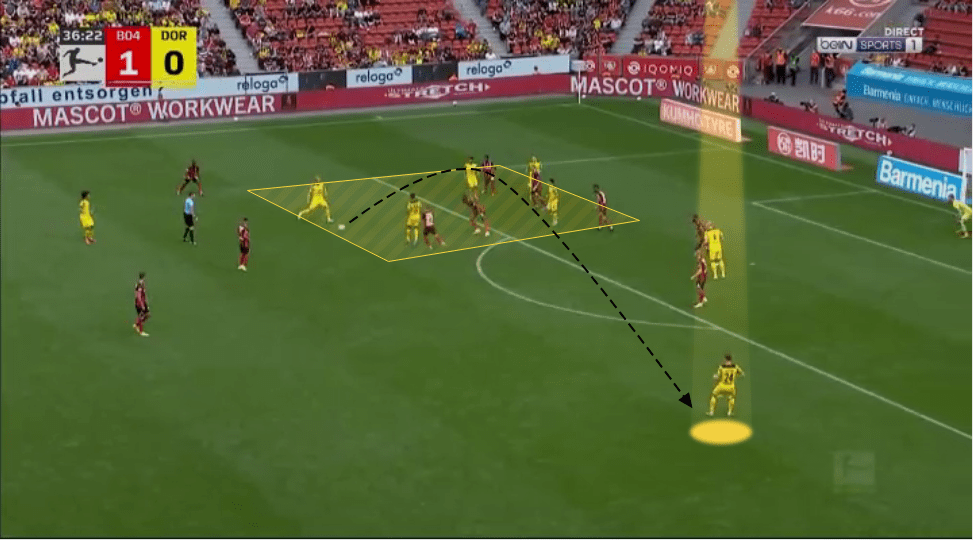

By using this method, you’re able to draw in opposition defenders, before finally finding the underloaded side of the field with an open man or create a 1v1 situation.

Accomplishing this though is much easier said than done. Players must always be moving and looking for new openings to receive in space, while being cognizant of the locations of rest of their team. They do this by creating triangles in those wide areas, where small movements can open up another pass once the ball carriers moves the ball on.

The idea of keeping play in small spaces is apparent at the beginning of the next situation before Brandt finds Meunier on the right flank. With time to receive, open and cross, Meunier plays an inch-perfect ball onto Haaland’s head to finish. This idea alleviates the stresses of continuing to play in those tight spaces, while also providing a dangerous scoring opportunity in the form of a cross or a 1v1 like with the Wolf one before.

Timing when to send this ball out is imperative to its success, as the players are always there, but knowing when they’re free and when they can create a dangerous situation is hard. One of those risks is that these passes are full field switches, and with the entire team compressed into one area, losing the ball can (and has before) mean a hard counter to an exposed BVB backline. When executed properly though, there can be great effects.

Adding to the danger here for an opposition is that once Meunier receives in an underloaded zone, he’s quickly looking to play the ball back into an overloaded one before the opposition can react and slide across. At times, this can be seen as “useless width” where a player is standing on the opposite side of the pitch. I would contest that within reason this layer of width causes situations exactly like shown above.

Some other important parts of their play is specifically how Haaland and Malen play within the 4-1-2-1-2 specifically. Deeper in build-up, Malen acts as a way to link play with the 10 and the rest of the midfield. Some would call this a ‘false 9’ although this often makes it seem like he never runs behind. These runs behind though are why they’re positioned on the sides they’re on. Malen, a right-footed player, starts as the left striker, while Haaland starts as the right striker. Haaland has a very specific tendency to shoot from the deep, left-half space across his body. By playing as the RST, Haaland is able to make a diagonal run into the left half of the field, and receive a straight pass from his midfield or the wide areas. Malen is able to do similar on the right.

Conclusion

Dortmund alter their building tactics based on opposition, whether that’s man-marking, finding a specific spot to exploit, or understanding their zonal marking schemes.

The most obvious example is the way that Dortmund were able to run up goals against oppositions who used a stricter man-marking scheme while having to change their tactics for teams like Freiburg who sit deeper and play zonal for most of the match.

They’ve also altered their tactics not just to suit an opposition, but to suit themselves. For example: before the Gladbach match, both Reus and Haaland got injured. In this event, Dortmund may have looked to play their normal 4-1-2-1-2 with Reus and Haaland up top to exploit the width of their fullbacks. In the end, Rose switched to a 3–5–2, which still had the aim of exploiting those same deep half-space runs, but it added players to the defensive line to change the way they build without Haaland’s and Reus’ abilities.

Comments