Halfway through the 2018 season, Martí Cifuentes was appointed head coach of Sandefjord in the Norwegian Eliteserien. Despite the turnaround of results, that autumn they were relegated, whereas Cifuentes was trusted with embedding his philosophy in the group while in the second tier. This season they are back in Eliteserien, playing a brand of football quite different from last time.

This tactical analysis will examine the tactics employed by Cifuentes at Sandefjord. Firstly, it will look at data to present a picture of development from season to season. Secondly, it will present an analysis of Cifuentes’ philosophy at Sandefjord and how it manifests in defence, attack and transitions.

The data analysis

When taking over a new team mid-season there are naturally an array of difficulties with implementing your own principles and turning things around. Firstly, there is the lack of a pre-season, and therefore no time available for large changes. Secondly, and it is often the case elsewhere too, Cifuentes was hired because of the lack of good results. This further strengthens the notion that time to practice structure, new principles and tactical habits, essentially a philosophy, isn’t available.

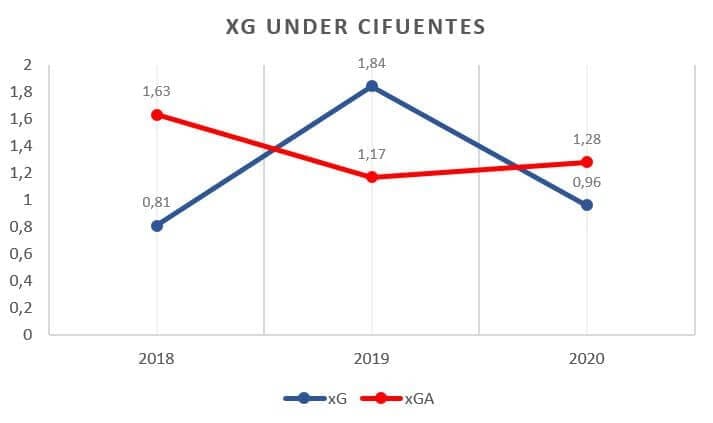

The results did change, but not right away. With the former Barcelona and Ajax employee they lost three of the first four matches and in the last 14, they also lost three. As a total percentage of matches lost, that is a decrease of 53.57%. The trend of being defensively solid is something Cifuentes has managed to keep with the team, both the season in OBOS-Ligaen and this season in Eliteserien. The xG numbers for and against for the last two seasons and this year’s can be seen below.

The graph shows how xGA (expected goals against) went down to a league-best number of 1.17 per 90 the season last season. This, along with the increase in xG, is expected when playing against lower quality opposition. What is interesting to notice, however, is that they have been able to keep the xGA at almost the same level this season. At the same time, the xG per 90 has increased compared to the last time they were in the top-flight.

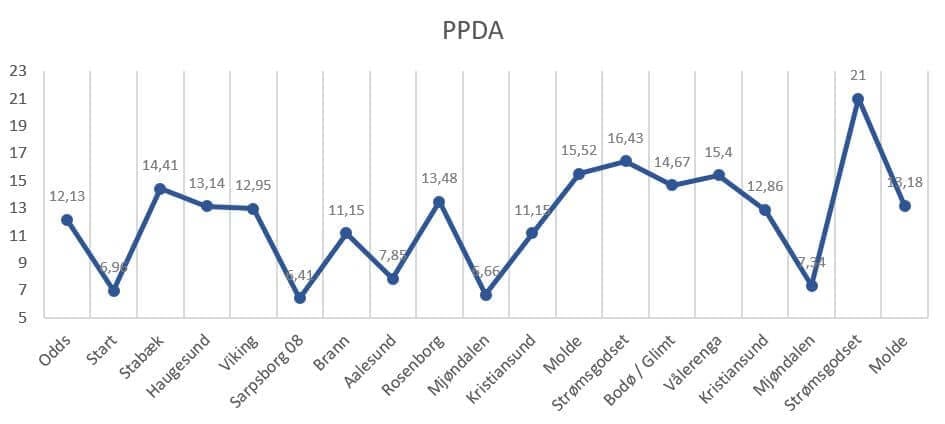

PPDA (passes per defensive action) is often used to present a picture of a team’s pressing. A lower number means the opponent has fewer passes completed before the team in defence has a defensive action. Last time in Eliteserien and last season in OBOS-Ligaen, Sandefjord had quite similar numbers in this category. 10.75 and 10.39 respectively are average numbers compared to top European football, but good in Norway. This season’s 12.2 shows a decrease in pressing intensity on face value, but considering they now play against teams that participate in qualification to UEFA Champions League and Europa League it is impressive.

Cifuentes’ and Sandefjord’s defensive approach this season is a sign of their good adaptability. Taking a closer look at PPDA and sorting by opposition, the data shows they have a high degree of variation with pressing intensity. Three matches with a number lower than seven and four games where it was higher than 15 are proof of that. The trend as of now seems to be that the better the opponent’s build-up from the keeper is, the more they stand off.

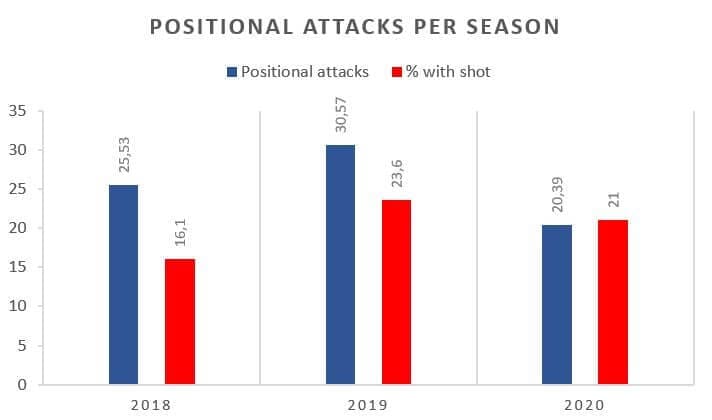

Attacking wise, Cifuentes has been able to implement methods that have increased the effectiveness in possession. In 2018, Sandefjord on average had 25.53 positional attacks per 90 where 16.1% ended with a shot. The amount of positional attacks was understandably increased in the second tier. However, the most impressive was the fact that almost every fourth attack ended in a shot. They met lower quality opposition, yes, but also more opponents that defended much deeper on the pitch. Thus, they were required to be more efficient in possession.

This season they had a 33.3% decrease in the amount of positional attacks. At the same time, they have kept the efficiency from last season with 21% still ending in a shot. From this, it is possible to deduct that Cifuentes has implemented methods of approaching the attacking phase that better creates and utilises space. In the following section, the focus will be on the aspects Cifuentes has successfully implemented in possession. Additionally, how this has helped to achieve the level of efficiency with the ball.

Staggered structure

The concept of staggering is used to describe the shape of a team for controlling space on the field. In this instance, it is meant for the shape in possession. A structure with good staggering utilises the available width and depth to provide ways of progressing play. It is also a central part of executing a good counterpress, but more on that later.

Positioning players on different lines of height makes it harder to defend against while also providing more connections within the structure. The image below shows a moment of Sandefjord’s structure in Cifuentes’ first match as head coach.

Using a screenshot like this has its drawbacks as it only shows the structure for a split-second. However, this flat structure was common to see at the time of Cifuentes’ takeover. The team has four, or three and a half, lines of players. The positioning of the lines of players makes it hard to progress play here. Two of the lines of players are on the side closest to their own goal compared to the opponent’s structure. In addition, four players (one player on the right outside picture) are standing on the last line, providing few problems for the marking of the opponent backline.

Starting flat like Sandefjord do in the picture above is not inherently a bad thing. Arriving into the desired space instead of standing there gives the defender less time to react. Less time for the defender means more for the attacker, which in turn could be the difference between a goal or no goal. The problem with Sandefjord here however, was that the tendency generally was not to move from a flat structure into a staggered one. The usual follow-up was arguably a flatter structure with players moving away from the opponent and out of their shape to receive. This led to a passive positional play, with most of the progression happening down the sideline.

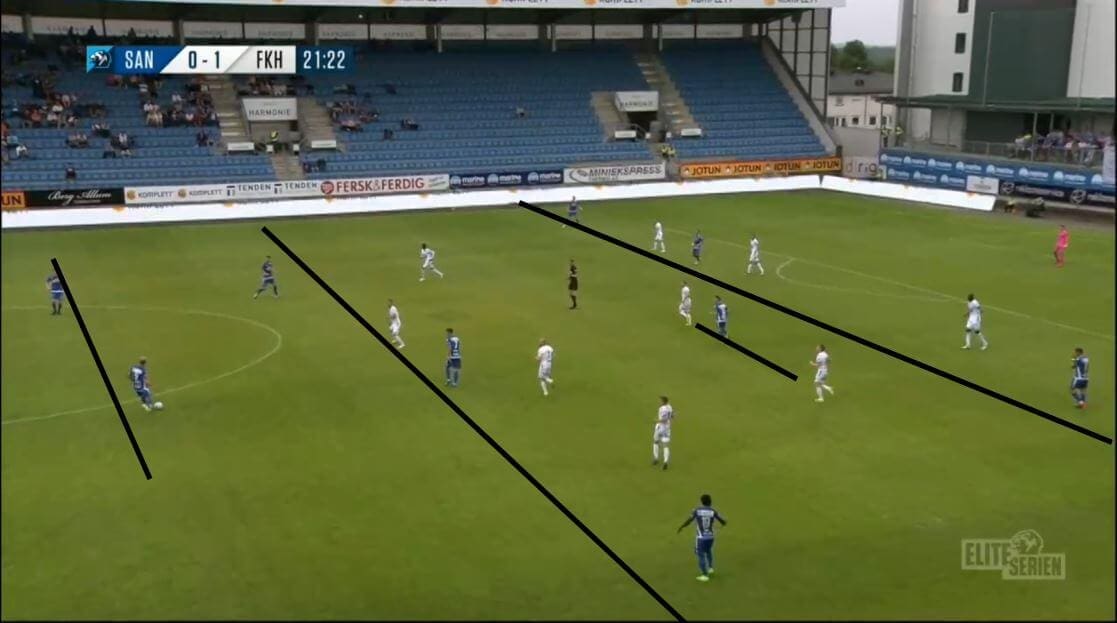

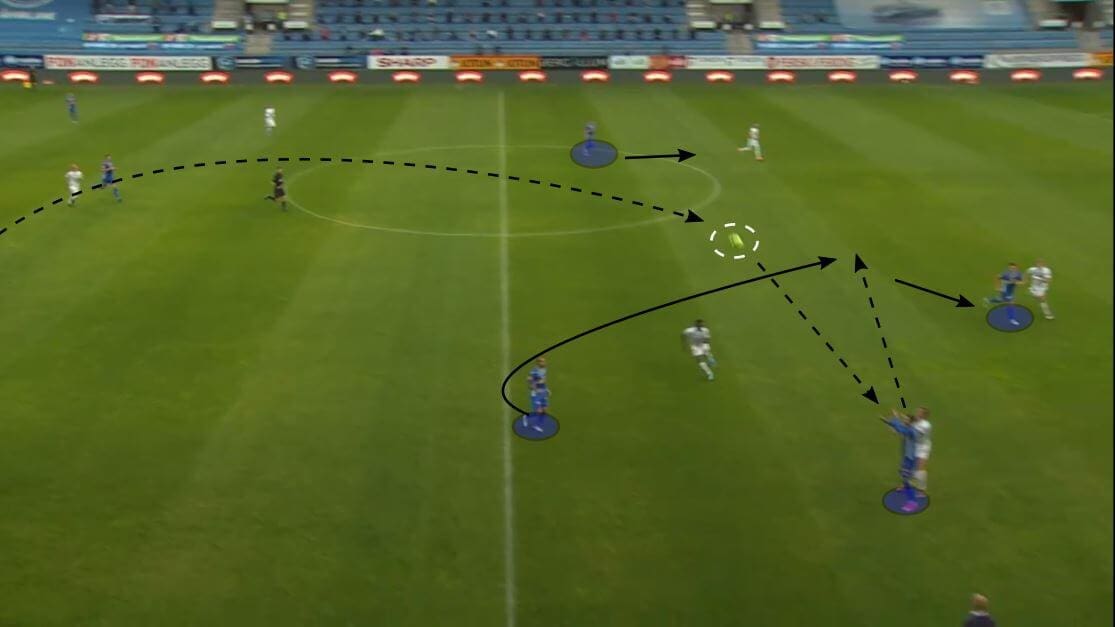

Above is another split-second photo of Sandefjord’s structure against Molde in the away win this season. Six lines of players positioned at different heights provide the ball-carrier with good options to progress play. There are several passing options as receivers have options for lay-offs, and the player in possession can carry the ball forward himself. Staggering the players in this fashion allows Cifuentes’ team better access to lay-offs and third man passes among other things.

Optimal utilisation of width and depth are central to having a well-constructed staggering in possession. Again, the photo above is a good example of how they achieve both width and depth. On each side, one player keeps the width. The player on the right is out of the photo but on the second-highest line. On the left, the player keeping width is the highest. The central staggering of defenders and midfielders provides several ways of progressing play. This plays a big role in the two players being able to keep the width with such a high line. Continuing on that point, the high and wide positioning forces the opponent full-backs to stay wider. In turn, this again opens space centrally.

A clean first progression

Cifuentes have installed an interesting combination of patience and directness in their own half. A numerical superiority in the first line is almost a constant with the team. Depending on how the opponent presses, this is most often the four defenders plus one or two midfielders. The remaining four players actively push the defensive line back with simultaneous movements behind the line, wide and between the defence and midfield line.

From this starting structure, they have the option to play both long and short. The offside rule does not apply to goal kicks, and therefore the long ball in behind from the keeper is an option here. This also poses another dilemma for the opposing team, namely how they deal with the height of the four players. If they want more security and be in superiority in the back, they will have a two-man inferiority in the press. With a one-man inferiority they have better access to the Sandefjord players in build-up, but man to man with the four highest attackers.

The full-backs in the team stay low and wide during the goal kick. This invites the opponent wingers higher in the field, potentially leaving space for them to take advantage of later. This can be a wall pass with a centre-back or central midfielder. If not, the positioning also leaves space for the winger to receive if he comes deep. Another aspect of the full-back role in Cifuentes’ team is the inverted runs with the ball, especially on the right side. The player there will from time to time take advantage of a striker being pulled out of position to press. He does this through carrying the ball into the vacated space, creating further numerical superiority centrally.

Up-back-through

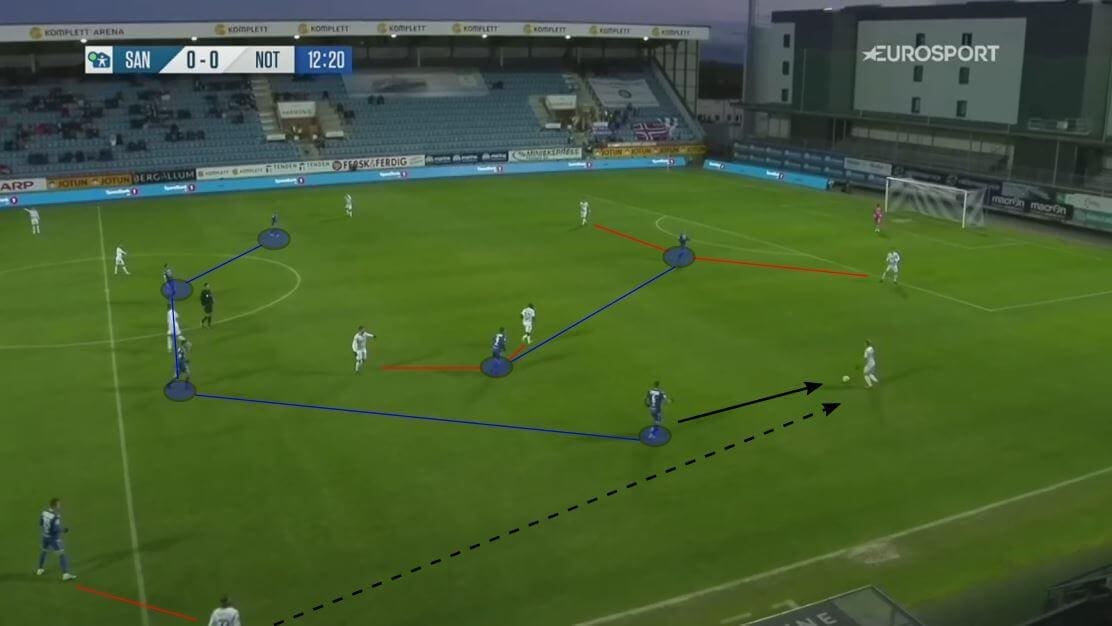

As mentioned at the beginning of the last section, there is an interesting mix between patience and directness. Cifuentes has installed within the team a concept used very much in Spanish football, the up-back-through. The difference, however, is that this is often a concept used to get past one line of pressure. In Cifuentes’ Sandefjord, the concept is often used to attract the opponent’s pressure before playing over it, and past several lines of pressure.

They will often play from a centre-back, via a deep midfielder to the other centre-back or the right full-back. The initial forward pass attracts the attention of the opponent, along with the follow-up back-pass. Both a player receiving with his back turned and a backwards pass are normal press triggers. Therefore, the desired result of attracting the opponent is achieved and there is space behind to take advantage of. In these situations, many teams in Eliteserien leave a lot of open space between defence and midfield. This is where the last part of the up-back-through takes place.

Either the striker or the right winger will take the ball down. The next move is a lay-off to an onrushing central midfielder or play in behind for the attacking midfielder as shown above. The exact situation above puts Sandefjord in a 3v2 against the opponent just five seconds after the keeper had the ball last. It is also another example of how Cifuentes’ ability to adapt the team to the opponent is a strength. The team they met here, Strømsgodset, is one of the most aggressive teams in the league in their high press. They tend to leave spaces in these areas when they press high, something, it seems, that the Sandefjord coach had noticed beforehand.

The medium block

Previously, this analysis stated that Cifuentes is a coach with a high level of adaptability. The defensive phase is a good place to look at with his team to see this. They are newly-promoted and, on the paper, the weaker team in most matches. Therefore, a high press with the intention of winning the ball in the opponent’s half is a poor choice in many matches. He employs a medium block in a 1-4-4-2 structure against many teams, where the opponent centre-backs are allowed to have the ball. If the opponent plays with a single number six, he is often marked tightly in the build-up, which makes the central progression harder.

The trigger for when to start the press is the top of the midfield circle. When they first press in the targeted area, they press very aggressively, showing the centre-back carrying the ball towards the full-back as the only forward option. The middle is closed off with a high degree of compactness both vertically and horizontally. The ball-far of the two in the first line of pressure will stay with the number six to keep him from becoming an option for switching play.

When they are successful in forcing the ball wide, they will swarm the area and cut off the option to play the ball back to the centre-back it came from. The already compact shape makes it very hard for a potential pass from the full-back to the inside. Winning the ball back in this manner is made easier by the sideline, limiting the options for the full-back. In essence, the only options for the full-back is a forward pass to the winger or a long backwards pass to the keeper. If he plays it forward, then Sandefjord have a good option of winning it back.

High press

Specific triggers allow Sandefjord to go from their medium block into the high press that was much more visible during last season. Three triggers that seem to be constant for initiating are loose/poor balls, perhaps above ground, backwards passes and a backwards turn. There are others as well, but it seems at least these three are a part of most pressing initiations.

Against weaker opponents they will still utilise the high press they used so frequently last season. This is visible also in the data analysis section at the start of this piece. There is a clear link between certain teams expected to be weaker in possession, and the PPDA numbers against them.

Counter-pressing

Cifuentes at Sandefjord has so far been a very interesting journey to follow. How he quickly added defensive stability in his first season while starting to implement his own ideas and principles is impressive. Last season saw the team keep the defensive stability while vastly improving in the attacking phase too. This season they have faced stronger opposition and adapted the approach without sacrificing their principles. They have done this with great success, arguably punching above their weight in Eliteserien. If Cifuentes keeps up the development of this team for the rest of the season, Sandefjord will be very fortunate to keep him for another one.

Comments