Miguel Angel Ramirez may be a name not many are familiar with just yet. But this ‘yet’ is definitely key in this sentence. The 35-year-old coach is currently managing Independiente del Valle over in the Ecuadorian top-flight and has even managed to secure his first title at the club by clinching the Copa del Sudamericana in 2018/19.

His team is well known for its attacking and exciting tactics, positional play and possession-based style of football that often both impresses and mesmerises the crowds. In this tactical analysis, we will take a more in-depth look at those tactics and try to explain why he just might be one of the coaches of the future.

Build-up tactics

Ramírez’s philosophy revolves heavily around positional play and outmanoeuvring the opposition with passing, movement as well as space creation and exploitation. The basis of his tactics, as we will see further down the line of this tactical analysis, lies in creating superiorities across the pitch.

On paper, Ramírez prefers to deploy his team either in a 4-1-4-1 or 4-4-2 systems but on most occasions those formations will transform on the pitch, depending on whether the team is in or out of possession and their current phase of play.

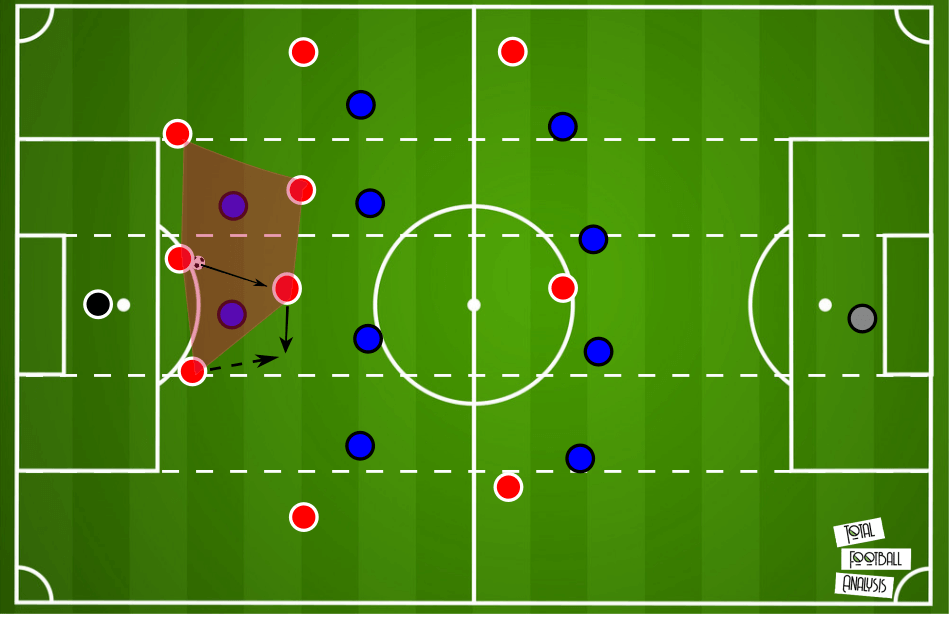

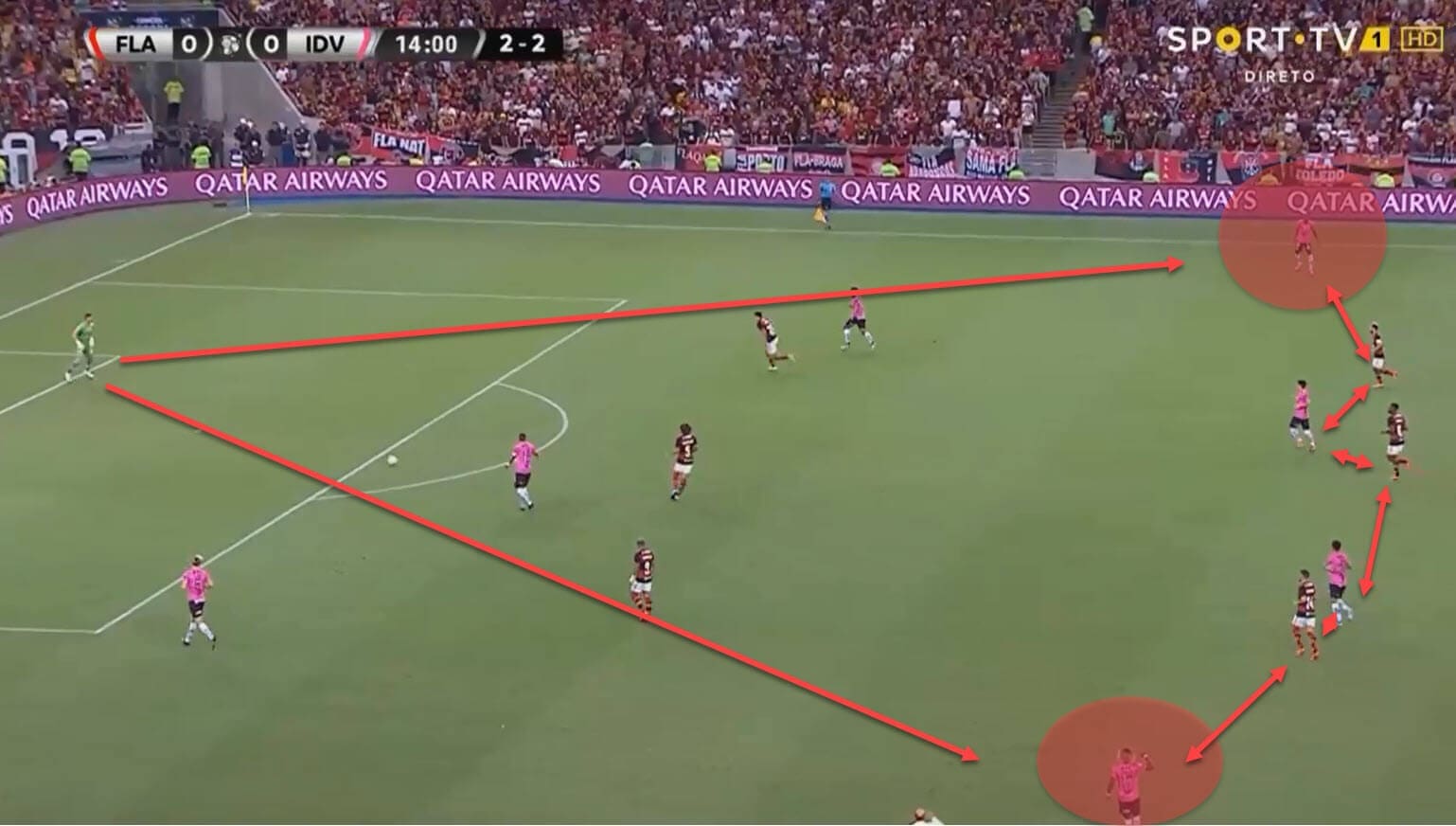

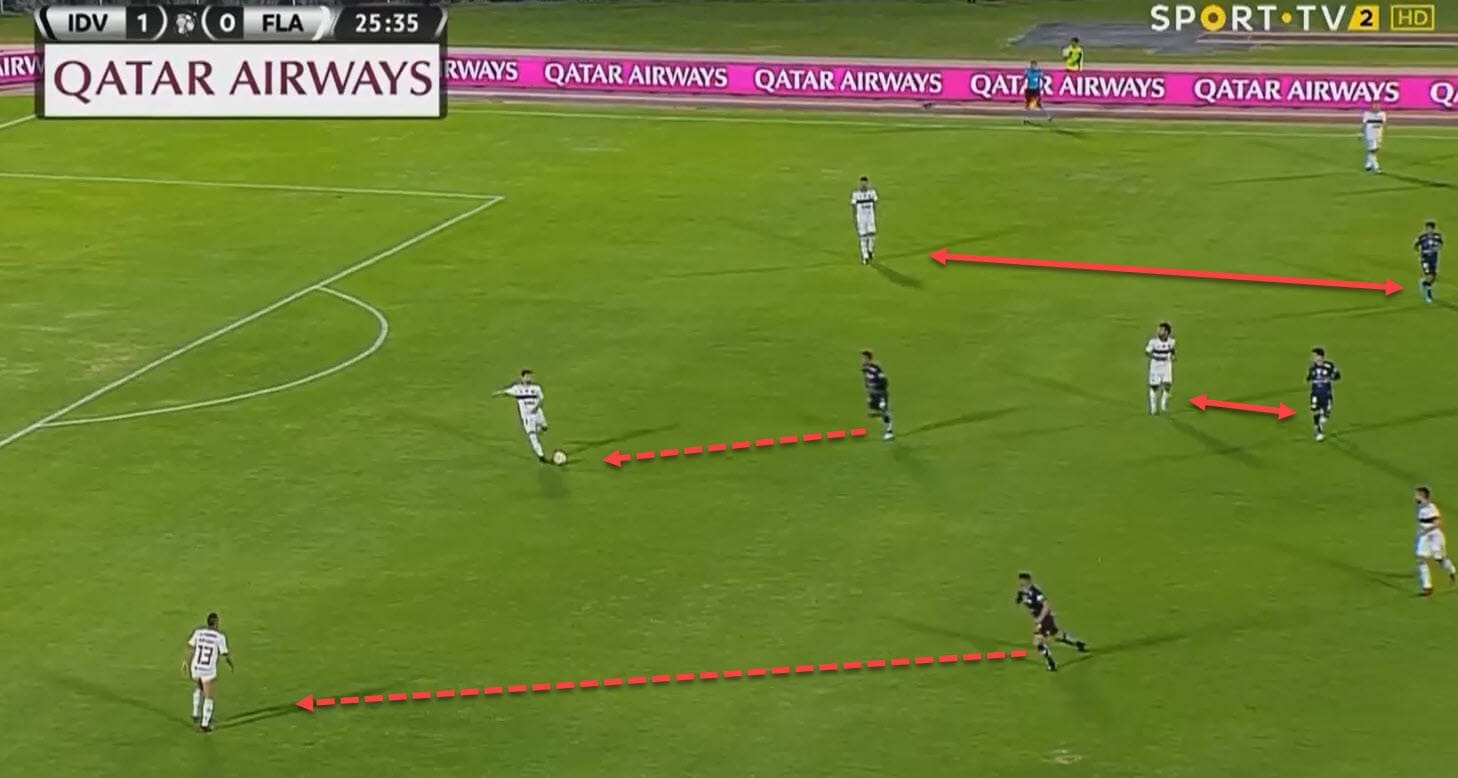

The most common structure we will see Independiente utilise is a back three against the opposition’s front two. In that scenario, where they have to resist the press of only two players, the pivot will often drop between the centre-backs to create the back three and establish a numerical superiority against the pressers. You can see an example of that structure down in the image below.

By pushing the full-backs higher and wide on the pitch, Ramírez ensures they occupy the wide midfielders while Independiente’s own central midfielders form a double pivot and drop behind the opposition’s second line to ensure numerical superiority in the first phase of build-up.

The above example shows us a 5v2 situation in which bypassing the first line of press is a mere formality for Independiente. By recycling the ball along the backline, they can easily stretch the pressing duo and then combine with either of the two pivots to progress the ball. In case the midfielders are then pressed from behind, the ball can quickly be returned back to one of the wide centre-backs who then step out into the open space and advance the ball by simply carrying it forward, as can be seen from the image.

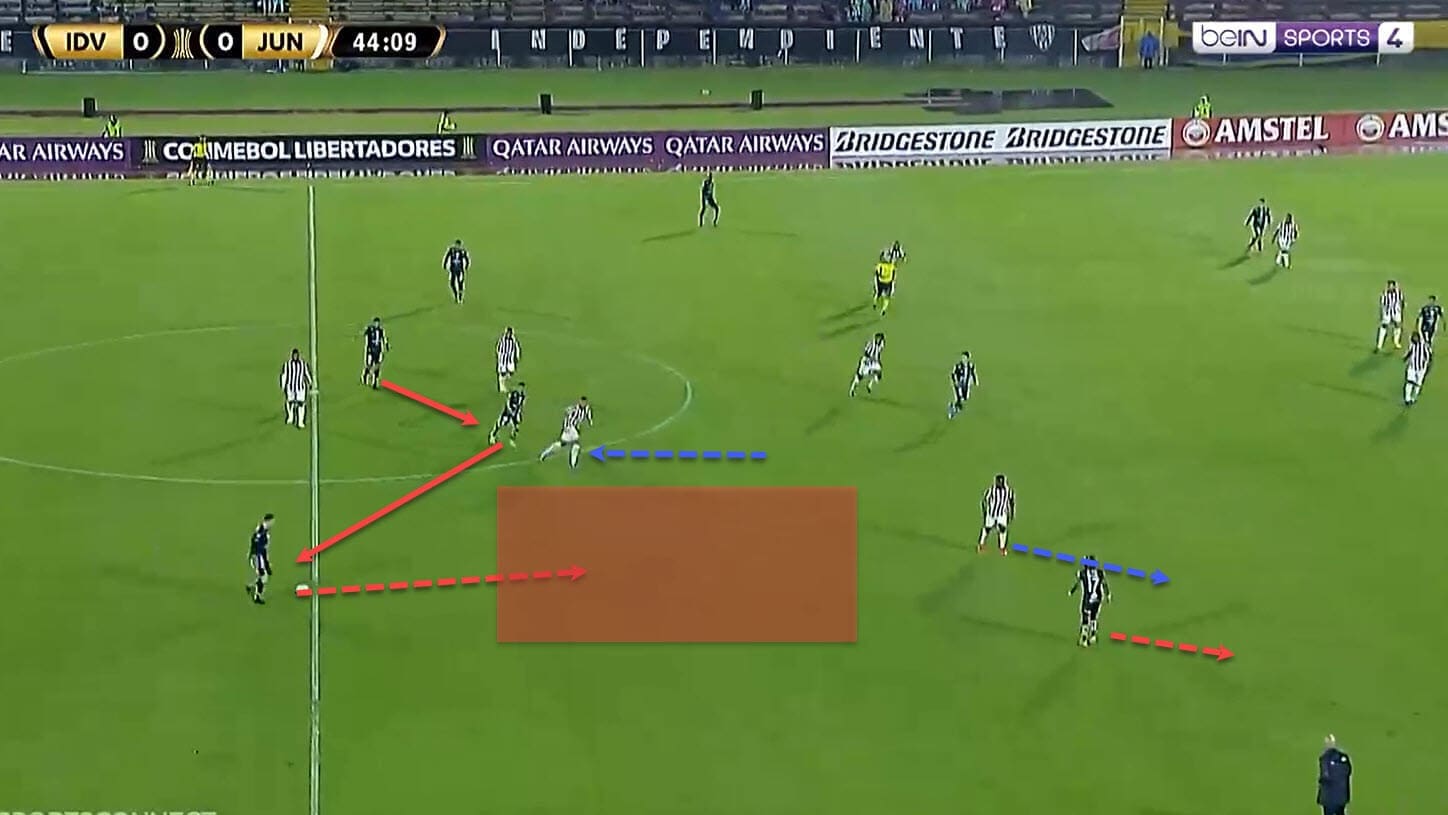

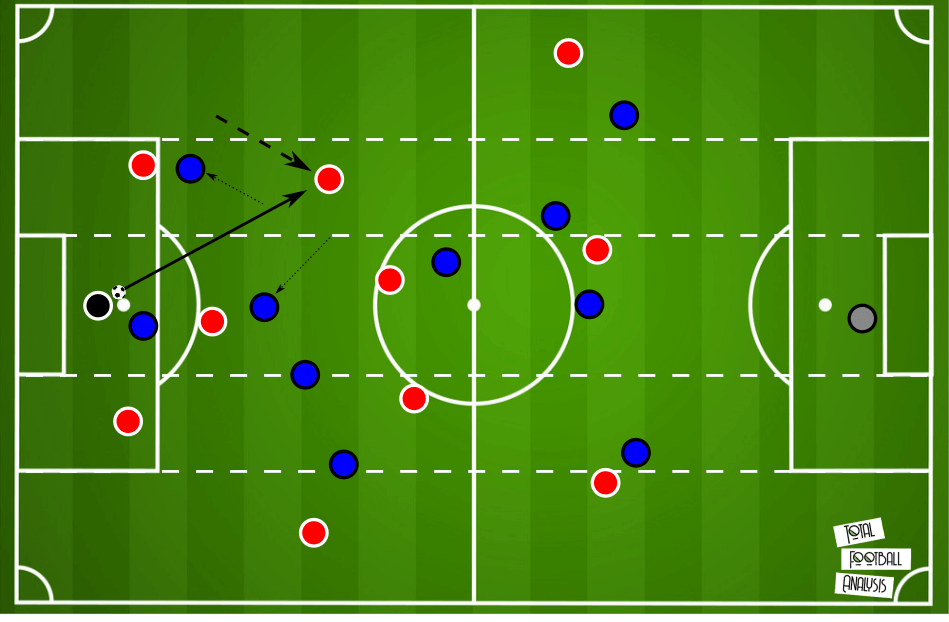

Let’s observe an in-game example below as well. The pivot once again drops between the centre-backs and the other midfielder remains close to ensure the superiority. A quick combination between the backline and one of the midfielders ejects the centre-back who can push forward and progress the ball into open space.

And since an additional midfielder has dropped deeper to combine with the backline, he pulls another marker with himself, opening space for the centre-back to exploit with his run.

Of course, good ball-playing centre-backs who are brave and secure in possession are a must for these tactics to work and Ramírez has them at his disposal. But there are many variations for beating the pressing squad and advancing the build from the backline that they utilise in addition to that.

Generally, they are not afraid to recycle possession until they see an opening and then they exploit it. Creating numerical superiority in the first phase of play, however, is the foundation on which they build their attacks further. This gives the centre-backs the freedom to move forward safely without having to engage the opposition in duels.

Usually, one midfielder will drop to connect with the back three and outplay the pressing duo while the other midfield works together with the full-back to push the other markers higher up the pitch, creating a pocket of space to exploit.

These are, however, just one of many variations that mostly depend on the opposition’s structure and how well they are pressed during a game. Luckily, they can use their goalkeeper and full-backs in other ways to manipulate the other team’s movement.

Using the goalkeeper to beat the press

Another important aspect of Independiente’s build-up phase is their use of the goalkeeper and full-backs to escape the press. Using the goalie is a great way to stretch the opposition’s frontline, especially if they match the backline man for man, usually in a 3v3 scenario, considering that’s the most common build-up structure they will use.

In that scenario, the goalie will work together with the rest of the squad to create that numerical superiority and bypass the press. We can see a clear example of that in the image below. Both the centre-backs and the pivot have a marker following them closely but by involving the goalkeeper, Independiente suddenly have a one-man advantage.

As soon as the goalkeeper receives the ball, it activates the press from the nearest forward, who leaves his original marker to charge for the ball. At the same time, the pivot will quickly drop deeper to offer an additional passing channel that will only be used to lay off the ball to the free centre-back on the other side who can then advance up the pitch.

It’s a rather simple method that is once again using the numerical superiority against the opposition, this time achieving it by involving the goalkeeper in the build-up tactics. But that works best when the opposition decide to press all the way up the pitch.

Still, when they are pressed in a 4-3-3 structure that marks their three-man backline and the double pivot, they can still use the goalkeeper’s passing range to find the free man in space. Usually, that free man will be the full-back but the main idea is to put the opposition in a situation where they have an impossible decision to make.

You can see the basic structure behind those tactics in the image above. The opposition’s midfield has to decide whether to press the full-back or one of the midfielders but choosing either frees the other man as a direct result.

Of course, the goalie then has to find his teammate with an accurate pass and by failing that, the whole concept and the attack break down immediately. Still, even if the opposition invest more players to mark out of the options, Ramírez also likes to drop his wingers deeper to receive the ball either directly from the goalie or from the backline, whoever is in possession at that time. This, once again, ensures the numerical superiority is always on their side.

But there’s also an interesting concept I’ve noticed them utilise in a couple of games and that is the use of inverted full-backs. These tactics are both used as a tool to advance the play from deep and occupy the right spaces and markers higher up the pitch to set up different attacking movements.

We’ll explore that further in the following section of our tactical analysis.

Inverted full-backs in build-up and offensive tactics

Interestingly enough, the analysis has shown that Ramírez likes to use inverted full-backs in two of his attacking phases of play. The first phase is, of course, the build-up phase and there, the full-backs are used to progress the ball further up the pitch and bypass the pressing squad.

If the goalkeeper is forced to receive the ball while the opposition pushes high with multiple players, the centre-backs and the midfielders move in such a way to create additional passing channels that can be used to escape the press.

Notice such an example down below. The goalkeeper has the ball and both of his teammates who are dropping deeper are dragging their markers away, opening a channel towards the full-back who has inverted inside to occupy a more central position where he can receive the ball cleanly and unmarked.

This is basic movement manipulation and on paper, it’s a pretty straightforward setup but it’s difficult to execute. Still, once you do master it, it can work like a charm and bypass the press easily. But inverted full-backs seem like an everpresent concept with Ramírez.

When it comes to Independiente’s attacking structures, both of their wingers like to stay higher up the pitch and keep the width almost at all times. Of course, they will drop deeper if necessary to combat the inferiority and help the build-up but as a general rule of thumb, they usually occupy the high and wide areas.

This, in turn, means that the full-backs will underlap instead of overlapping and generally advance through their respective half-spaces. The idea is then to isolate the winger with their markers, leaving them in 1v1 situations or even better, eject them into open space unmarked.

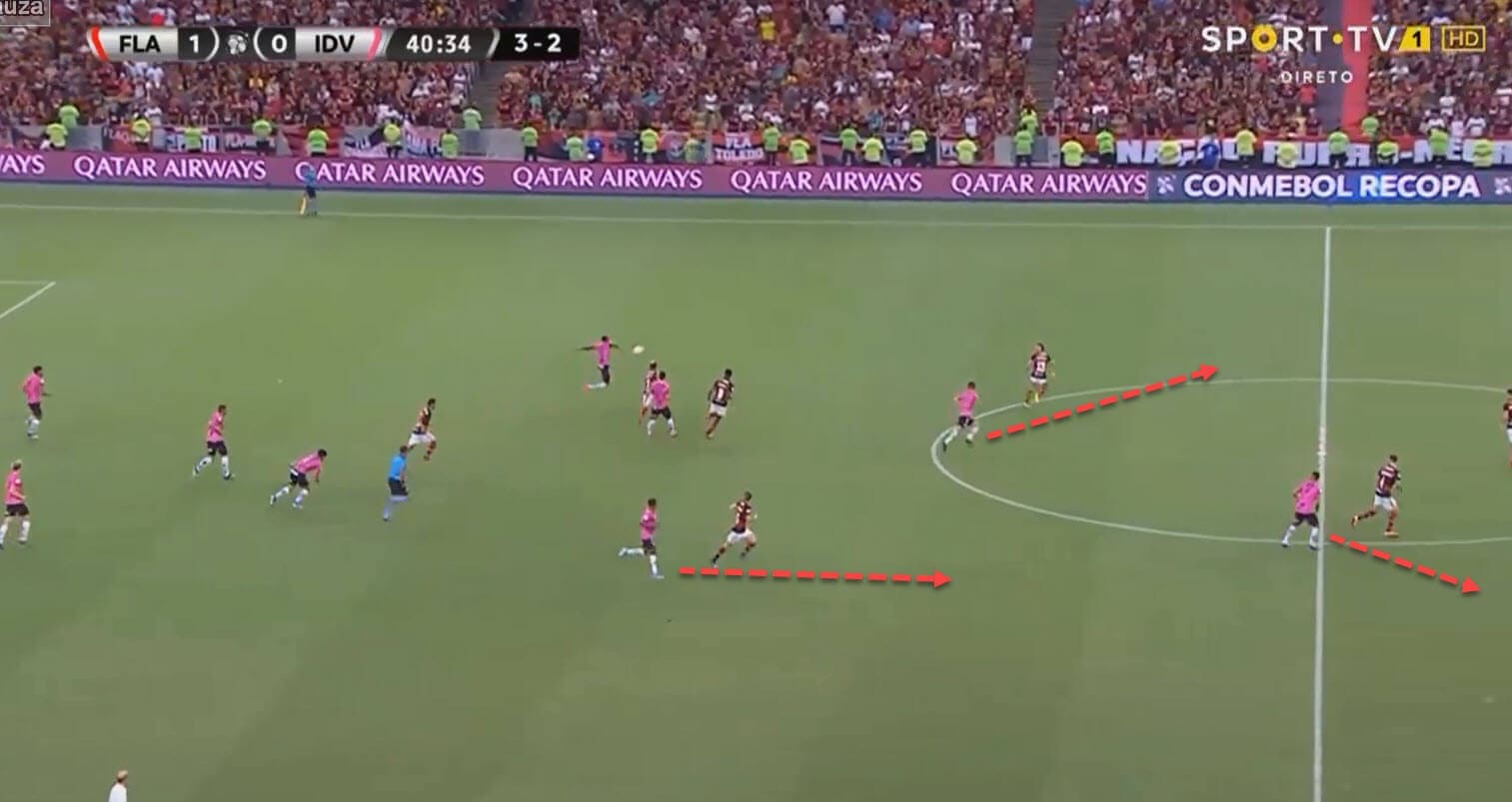

Let’s observe one setup with inverted full-backs that enables such a course of action. Below, we can see the ball is initially with the wide centre-back who plays it to the left-back out wide. While that is happening, the right-back moves forward and into the centre of the pitch, where he can receive the ball from his teammate.

His movement attracts the attention of multiple markers who all try to collapse on him and snatch the ball away but he can quickly lay it off for one of the near midfielders. But since all the defenders converged into the central areas, the winger who is still keeping his width on the flank is left completely free to receive the ball.

All it takes after that is a quick pass over the top to eject him into open space to attack the final third and the box unopposed. Similarly, the inverted full-backs can also be used as links between the middle and the final third.

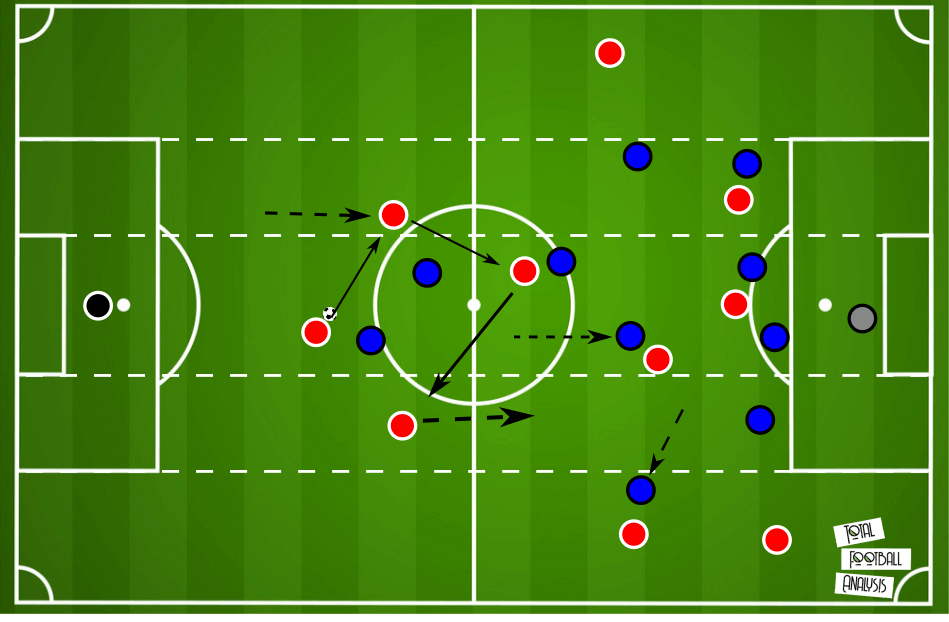

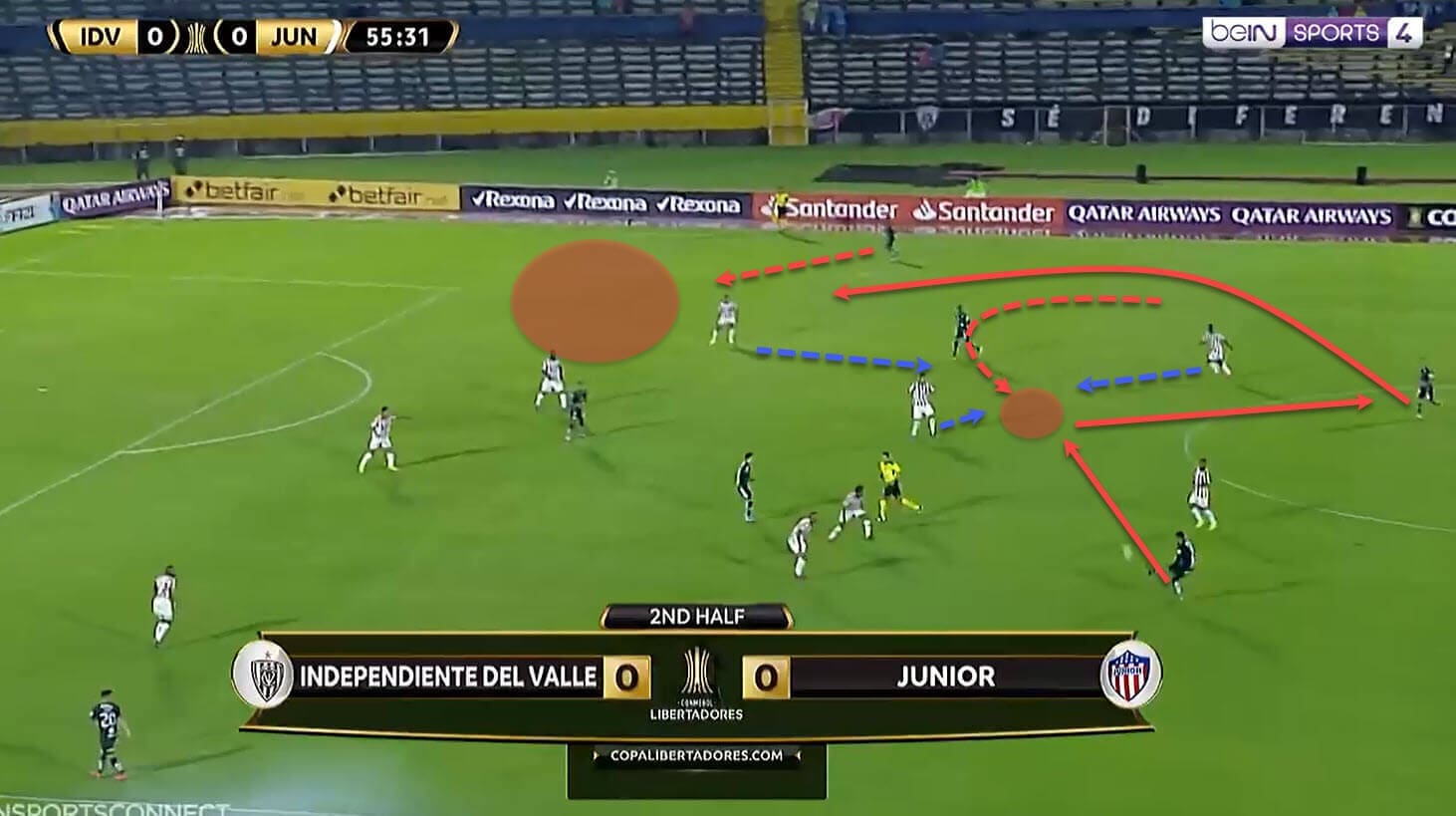

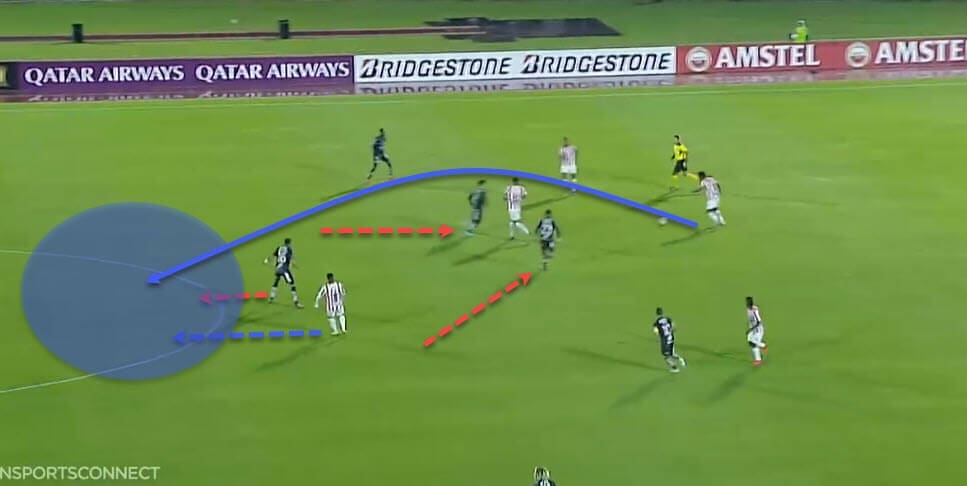

Just like in the previous examples, movement and superiority are key for these tactics to work. Notice down below how Independiente have created a 3v2 situation as their pivot has once again dropped between the centre-backs, enabling them to bypass the two pressers. Then, the centre-forward will drop slightly deeper, dragging his marker with himself and the wide midfielder will take his place, moving his marker as well.

This, in turn, opens up a pocket of space that the full-back can exploit, receiving the ball directly from the backline and then progressing it into the final third with a penetrative pass in-behind the opposition’s defence.

The same process can be executed with a midfielder dropping deeper instead of the forward, as long as they move the markers and create those little pockets of space for the full-back. The role of the wingers is equally important as they are the ones stretching the defensive line as well.

Pressing and transitions

The final part of this tactical analysis will look at how Ramírez likes his team to set up during the defensive phase and in transitions. Generally speaking, Independiente will enforce a high and aggressive press but this depends on the state of the game and the position the team is in.

There is no clear structure Ramírez has set in stone for their pressing tactics but they do seem to employ a mix between a zonal and man-marking system. To put it simply, his players occupy certain areas on the pitch and then press an opponent who receives the ball or is about to receive the ball in that specific zone they’re responsible for covering.

Of course, this sometimes means they won’t be marking their counterparts tightly but will engage them if the ball is recycled their way or their man has already received it. Once that happens, they will start with the press. Let’s observe an example of that below.

Notice how the wide player stays relatively far from the opposition’s backline, blocking the channels towards the central areas but as soon as the centre-back in his zone is about to receive the ball, he engages in a press.

It’s also worth noting down the positioning of the other players, all of whom seem to have their designated counterpart to mark but don’t necessarily stay tight to them, as mentioned earlier in this tactical analysis.

In general, there are also some basic pressing triggers that I have noticed them consistently follow: the opposition receiving the ball with back to goal, recycling the ball out wide to the full-backs or the wide centre-backs and instant counter-pressing immediately upon losing the ball but only when the situation and the structure allow them to do it.

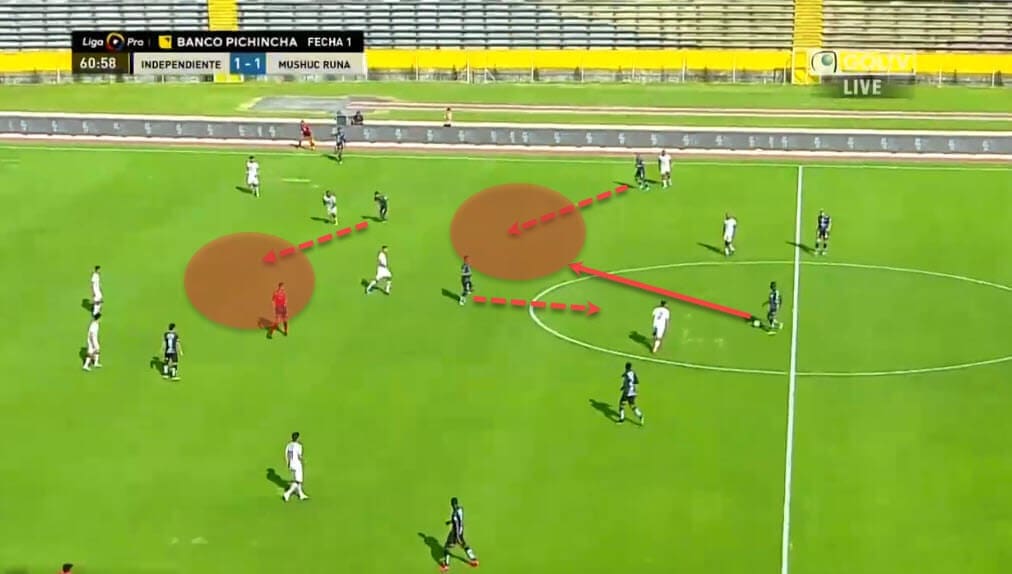

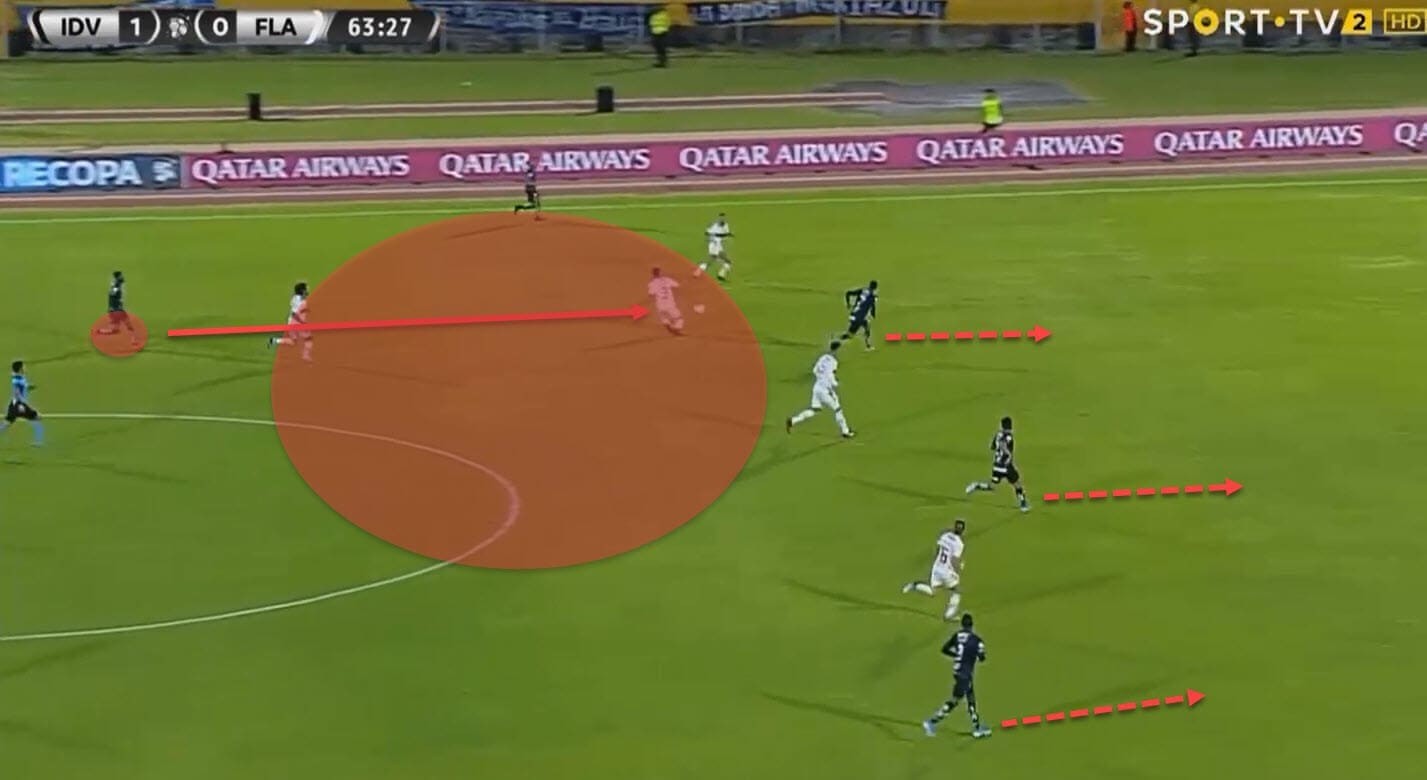

Overall, even though they are showing a high dose of aggressiveness in their counter-pressing, that is not exclusively among their go-to tactics. The reason behind that is that their basic structure and positioning rarely allows for successful counter-press. Let’s observe that in the following example.

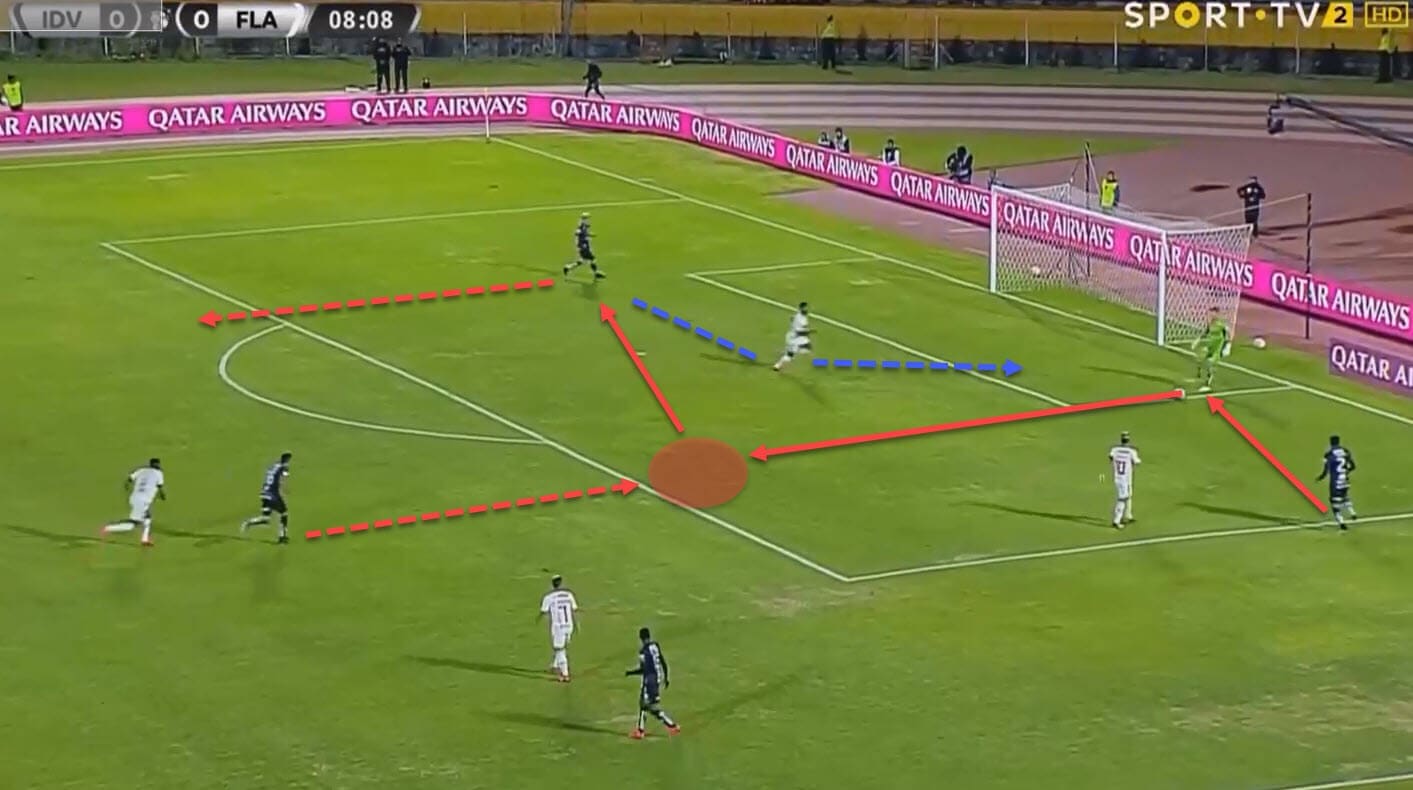

Independiente have just progressed the ball from the goalkeeper to the inverted full-back and then into the final third with three piercing through balls. However, the final ball was intercepted and there wasn’t anyone close enough to start the immediate counter-press.

The reason for that lies in their initial structure. Since the pivot regularly drops between the centre-backs and the remaining two central midfielders are positioned between the opposition’s first and second line of press to achieve superiority, there are not enough bodies higher up the pitch for an immediate counter-press.

Naturally, there will be scenarios which will allow for it at times but if the ball is quickly progressed through the thirds, the majority of their man-power will stay behind. The other side of the coin is that this allows for better counter-pressing in deeper areas and is also a good environment to instigate transitions from.

Most of the time, Ramírez will keep at least two forwards higher up the pitch during the defensive phase and upon taking back possession, they are immediately ready to charge forward into space.

It has to be said, however, that with 7.5 PPDA (passes allowed per defensive action) in 2019, they are among the more aggressive pressers in the league even though they might not always deploy those tactics. Still, with their structure that we discussed, it usually requires the deeper players to sprint over longer distances to successfully press upon losing the ball higher up the pitch.

This can make the press itself less effective simply because the opposition suddenly has more time to react and deploy their passes and if the second line presses from deep, it only leaves the centre-backs and the pivot to defend if the press is bypassed.

We can see such an example in the image below.

Final remarks

Miguel Ángel Ramírez may not have the pedigree of Pep Guardiola of Manchester City or Jurgen Klopp of Liverpool over in the Premier League, but he is definitely a young coach on the rise who could stake his claim on the big stage sooner rather than later.

Of course, we have already seen him as a youth coach at Deportivo Alavés and Las Palmas so he does have some European exposure on his CV. Still, it wouldn’t really be a stretch to say that even bigger things might be on the horizon for the 35-year-old coach.

Only time will tell, though.

Comments