Managerial sackings are one of the most devastating aspects of football. They don’t necessarily tell the full story and certainly don’t mean that a coach is poor, despite the negative stain it may leave on their career.

Some of the greatest managers of all time have been sacked by clubs in the past, often multiple times. The likes of Jose Mourinho, Louis van Gaal, and even Carlo Ancelotti have all stared down the barrel of the gun at one point before the trigger was pulled. It’s part of the merry-go-round that football management has become, for good or for bad.

This past week, it was announced by Swedish giants Malmö that Miloš Milojević was relieved of his duties after the club suffered a devastating and premature exit from the UEFA Champions League.

Di blåe were put to the sword by Lithuanian side FK Žalgiris in a 3-0 defeat on aggregate, losing 2-0 in the second leg at home, to hammer the final nail in the coffin of Milojević’s time at the Eleda Stadium in the Swedish South-West.

Milojević is a very astute and attack-minded coach as he had shown from his time with Víkingur, Breiðablik and Mjällby, but things, unfortunately, went wrong at Malmö.

As ever, Total Football Analysis is here to put things into perspective in the only way we know how – tactical analysis. This tactics piece will be an analysis of Milojević at Malmö, looking at what were the main issues suffered by the Swedish champions that led to the 39-year-old’s dismissal.

Preferred formation choice

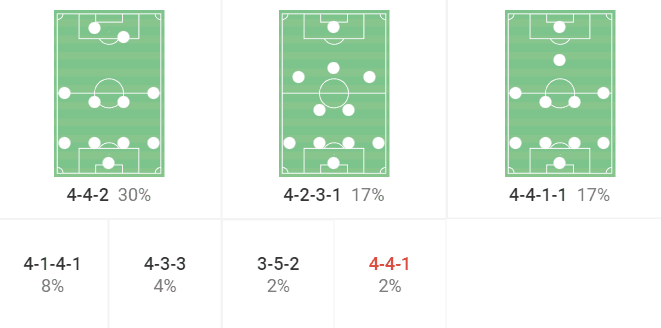

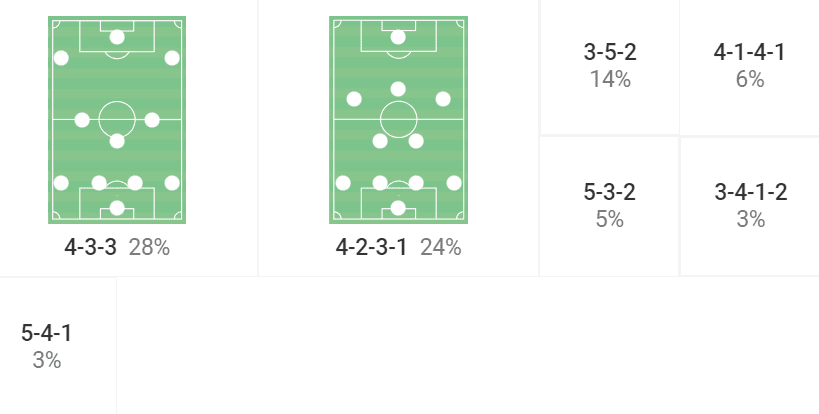

While some coaches are less stubborn and more tactically flexible than others, ultimately, they all have a favourite formation. Milojević’s has been the 4-3-3 at Malmö, although the Serbian complemented this nicely by using the 4-2-3-1 as a backup plan.

However, during his stint with Mjällby, where Milojević guided the team to back-to-back promotions from the Ettan to the Superettan, all the way to the Allsvenskan, the manager used a more conventional 4-4-2.

But in the 2019 campaign, Milojević employed the 4-4-2 in just 30 percent of Mjällby’s games in all competitions, seeing great success to reach the footballing promised land in Sweden. The 4-4-2 was still his go-to but the young coach was beginning to be slightly more flexible.

The 4-3-3, including its more defensive cousin the 4-1-4-1, was utilised in 11 percent of their matches.

After leaving Mjällby, Milojević moved back home to Serbia to become Internazionale legend Dejan Stanković’s assistant manager at Red Star Belgrade until 2021. Upon return to Sweden with Hammarby, the coach displayed even more flexibility, often sifting through a vast array of different formations like the 4-3-3, 4-2-3-1, 3-4-1-2, 3-5-2, the 3-4-3 and also the 4-4-2.

Nevertheless, with Malmö, despite the team’s struggles, Milojević settled on the 4-3-3, using the 4-2-3-1 as his backup option in certain games and even several variations of back-three shapes, once again displaying his tactical flexibility.

The Swedish giants have extremely technical midfielders in their ranks such as Sergio Peña, club captain Anders Christiansen, and Moustafa Zeidan which allowed the 39-year-old to play the 4-3-3 with a more possession-based approach as the side averaged the third-highest average share of the ball in the Allsvenskan under Milojević’s tutelage with exactly 58 percent.

Things seemed perfect on paper. An adaptable squad with youth, experience and technical quality, with a malleable head coach at the helm. But things didn’t look as perfect on the pitch as they sounded on paper.

Struggling to break down a low block

When analysing some of Malmö’s recent games, one thing that became apparent was their struggles in the opposition’s half to break down a deep defensive block. The team’s predictability became a prodigious issue, especially during their UEFA Champions League run.

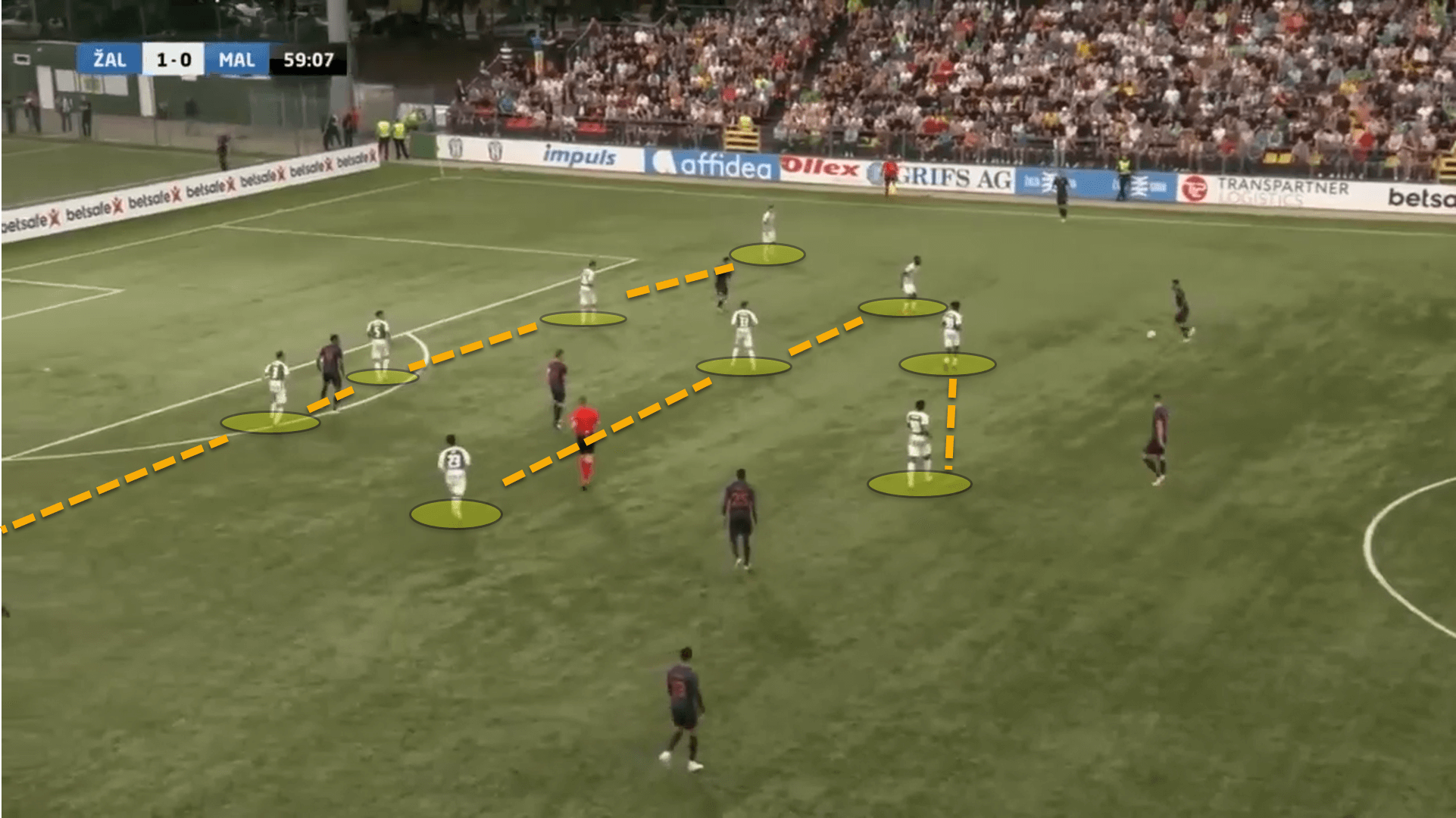

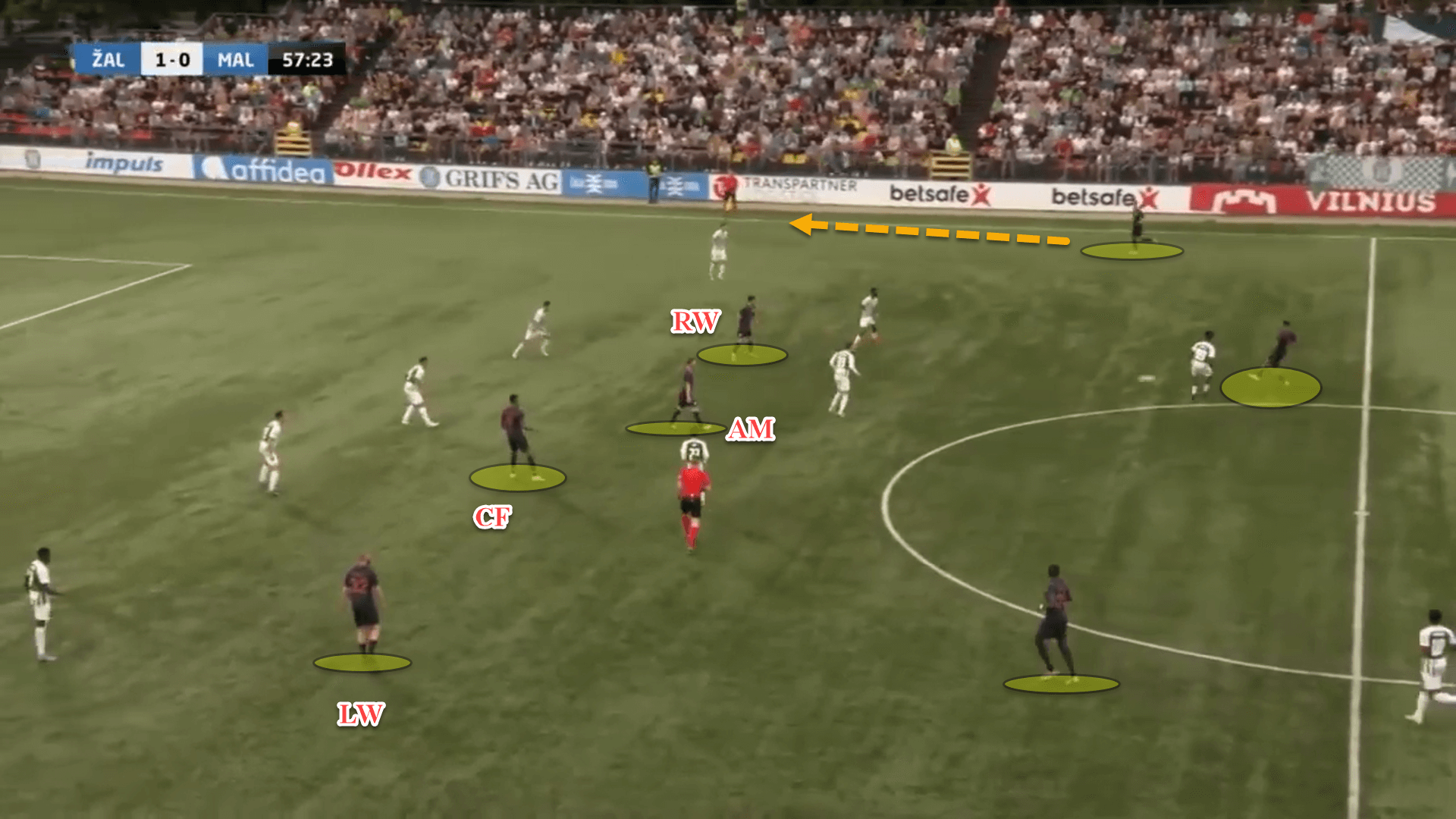

Against Žalgiris, manager Vladimir Cheburin had a simple plan to stifle Malmö and exploit their weaknesses. The Lithuanian side set up in a deep defensive block in a 5-3-2 shape, holding the line at the edge of the penalty area for as long as possible across both legs.

Full credit should be given to Cheburin and his players for being so resilient across 180 minutes of knockout football, successfully preventing Malmö from scoring a single goal in their quest to reach the next round of the competition.

However, with the fullest respect to Žalgiris, their players are not world-beaters. While a well-drilled low block can be difficult to carve open, much more was expected of Malmö who were far too predictable in the opponent’s half of the pitch.

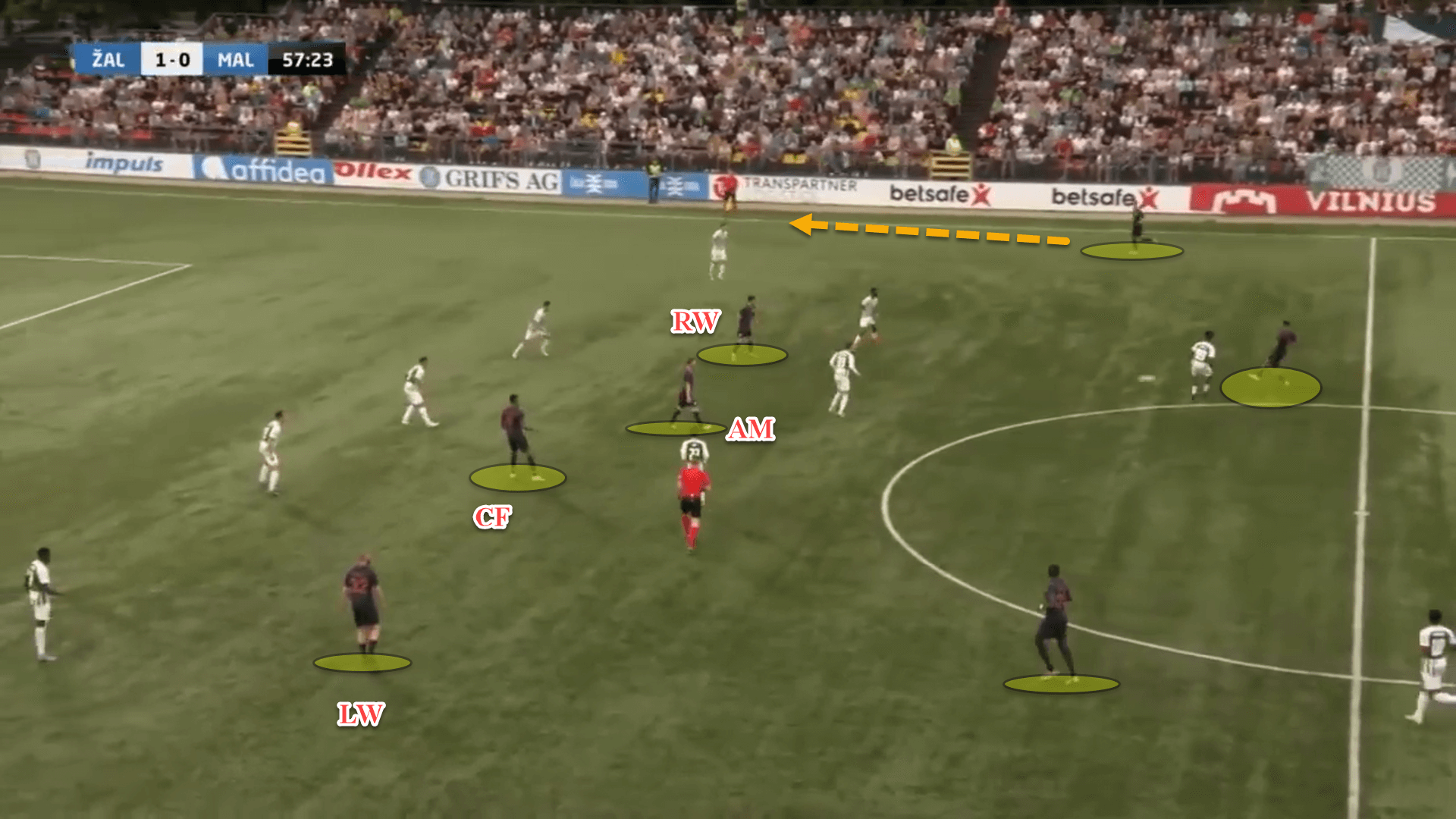

When in the opposition’s end of the pitch, Milojević wants his forward and midfield players to occupy the central areas of the pitch, while the fullbacks push high and wide on the flanks.

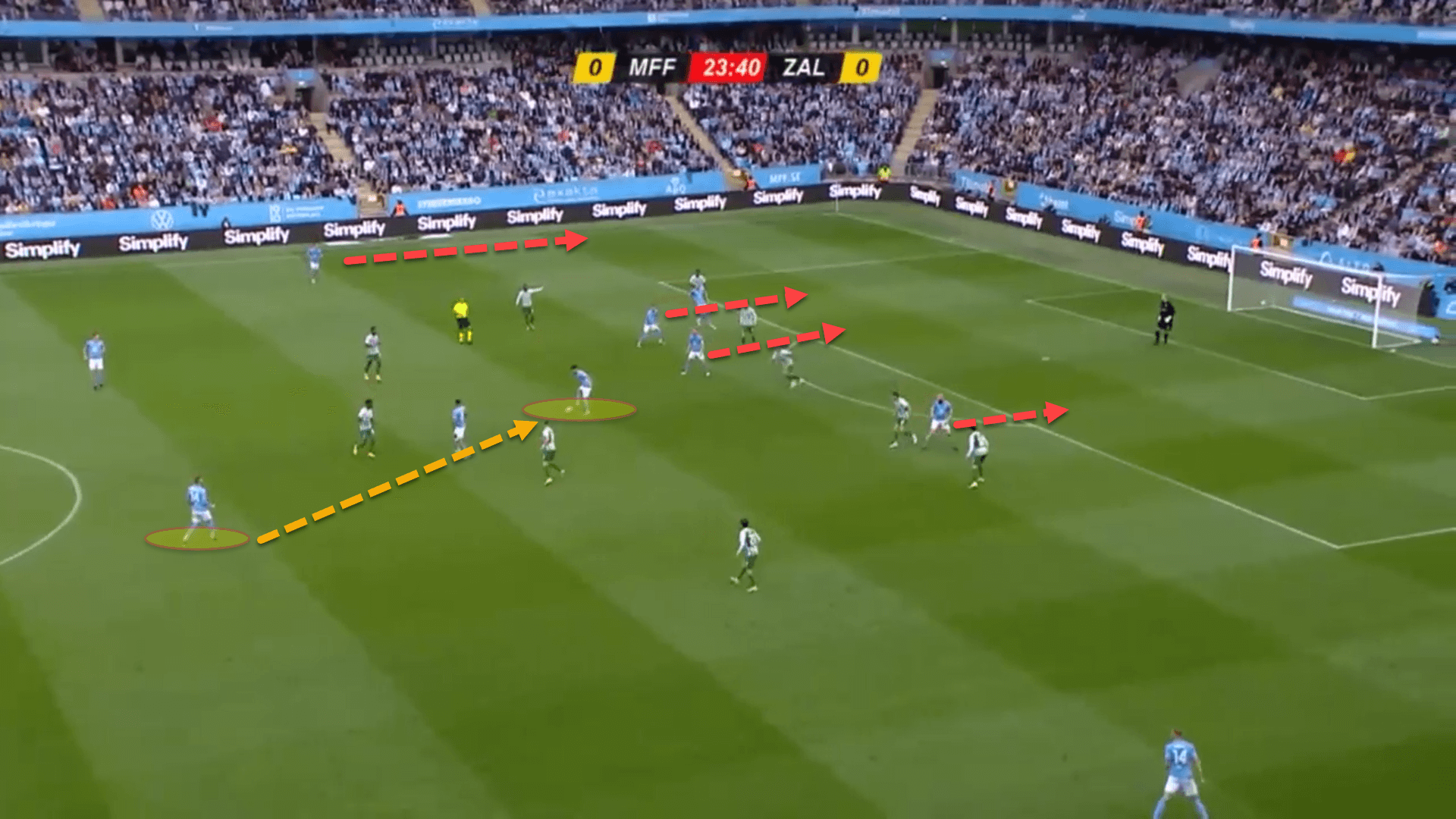

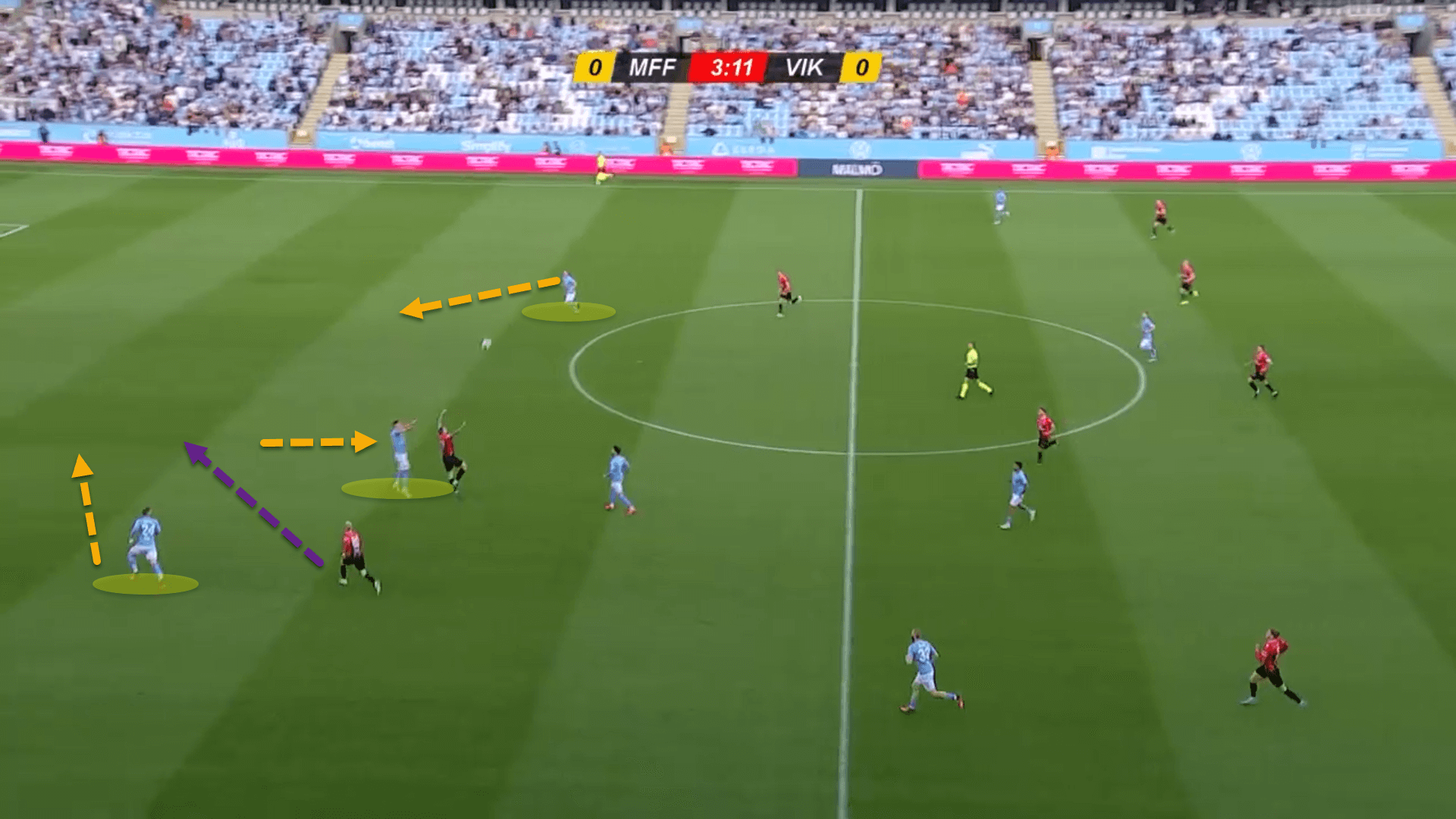

This was their set-up against Žalgiris’s deep block in the first leg out in Lithuania. Beginning in a base 4-2-3-1 formation, the wingers would invert and move inside alongside the number ‘10’ and centre-forward while both fullbacks pushed high on the sides.

The shape would often resemble a 2-2-6 or a 3-1-6 if one of the double-pivot dropped in between or beside the centre-backs. This was very similar to how Ole Gunnar Solskjær’s Manchester United played in these higher phases – plenty of occupation between the lines, high fullbacks and a constantly screening double-pivot.

However, Malmö found it somewhat difficult to reach their more technical players between the lines. There was barely enough room for the attacking players to receive the ball between the lines of the opposition’s deep block. This meant that they were not able to turn often and were forced to release it straight away.

For instance, here, there was a severe collapse in Žalgiris’s defensive structure. Malmö were able to get the midfielder on the ball with plenty of time and space to turn and play a slipped through ball behind the opposition’s backline. Unfortunately, this was one of very few of these moments.

One way to create more of these situations is to have players constantly attacking the depth of the pitch. Frustratingly, this was evidentially lacking from Milojević’s side as the players were constantly coming short to look for the ball to feet. Not enough were willing to make a selfless run beyond the defensive line.

Because of this, opponents have been able to hold their shape unscathed while Malmö attacked down the flanks. One of the reasons why there is a lack of running in behind is because doesn’t want the backline to drop too low.

How Malmö attacked in the final third under the Serbian was by creating triangles on the flanks and putting inswinging crosses in the box.

Crossing was the main form of breaking down a low block under Milojević. In the Allsvenskan, the side averaged 17 crosses per 90. This increased to 19.7 in all competitions. Furthermore, the side averaged 7.17 deep completed crosses per game.

By ensuring that the players did not run in behind, Malmö were able to keep oppositions’ defensive lines slightly higher, around the edge of the box which would leave space for their deep, inswinging crosses.

Unfortunately, while boasting a decent accuracy of 38.1 percent from crosses, their methods in the final third were far too predictable. This was what led to Milojević’s downfall in the Champions League. Di blåe’s inability to break down Žalgiris’ low block halted any chance they had of progressing and this is ultimately what lost the 39-year-old his job.

Failure to plug space

In the higher defensive phases, Malmö were actually quite impressive. Employing a mix of a zonal and man-marking system when pressing, the Swedish champions were really efficient at stifling their opponent’s build-up play.

Under the recently-dismissed coach, Malmö always pressed high, getting in the face of the attacking side in order to win back possession as close to the goal as possible. Over his last five matches, Milojević’s team averaged 93.8 ball recoveries per match. 18.9 of these were in the opposition’s half on average.

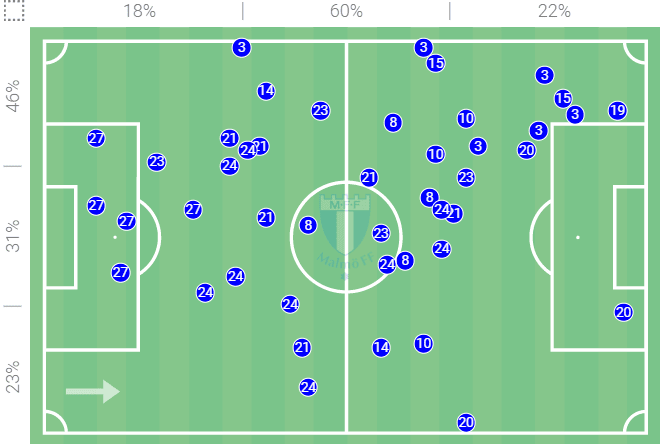

Here is an example of the areas where Malmö won the ball while pressing in Milojević’s final league match against Sirius. The most noticeable aspect of this data visual is that there was a clear plan to force the opposition to the left side before aggressively pressing.

The players knew their roles and responsibilities and executed high pressing really well under the former manager.

However, it was further down the pitch where things began to get a little tricky for the Allsvenskan side. There seemed to be a desperate unwillingness to track back from players, while plugging gaps in the backline was seen as the work of the poor.

When a fullback is dragged out wide, creating space between themself and the nearest centre-back, there are two ways in which the gap can be plugged. Either the backline can shift across to the ball-side, or else a midfielder can briefly drop into the space.

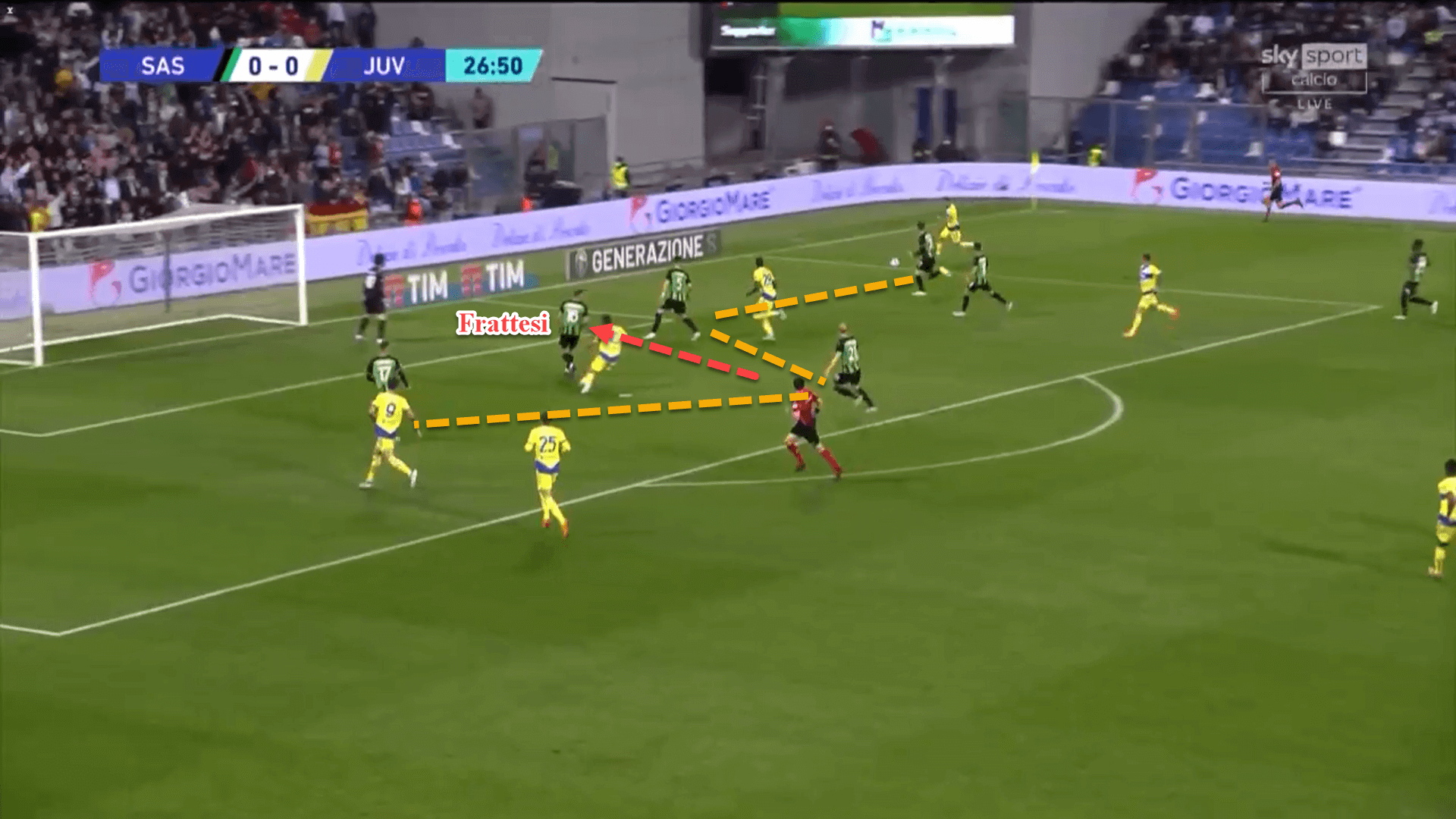

Look at this example, which was taken from the scout report of Davide Frattesi from the most recent edition of the Total Football Analysis Magazine.

Sassuolo’s centre-back had been late recovering his position and so Frattesi seamlessly slotted in to ensure that there were no holes in the backline. When Juventus played the ball into the box, Frattesi was there to clear it away, a wonderful display of common sense in the defensive phases.

However, at risk of sounding redundant and harsh, common sense was lacking in many of the players at Malmö when it came to plugging gaps in the backline. Oftentimes, it was far too easy for the opposition to play into massive channels between the fullback/wingback and the nearest central defender.

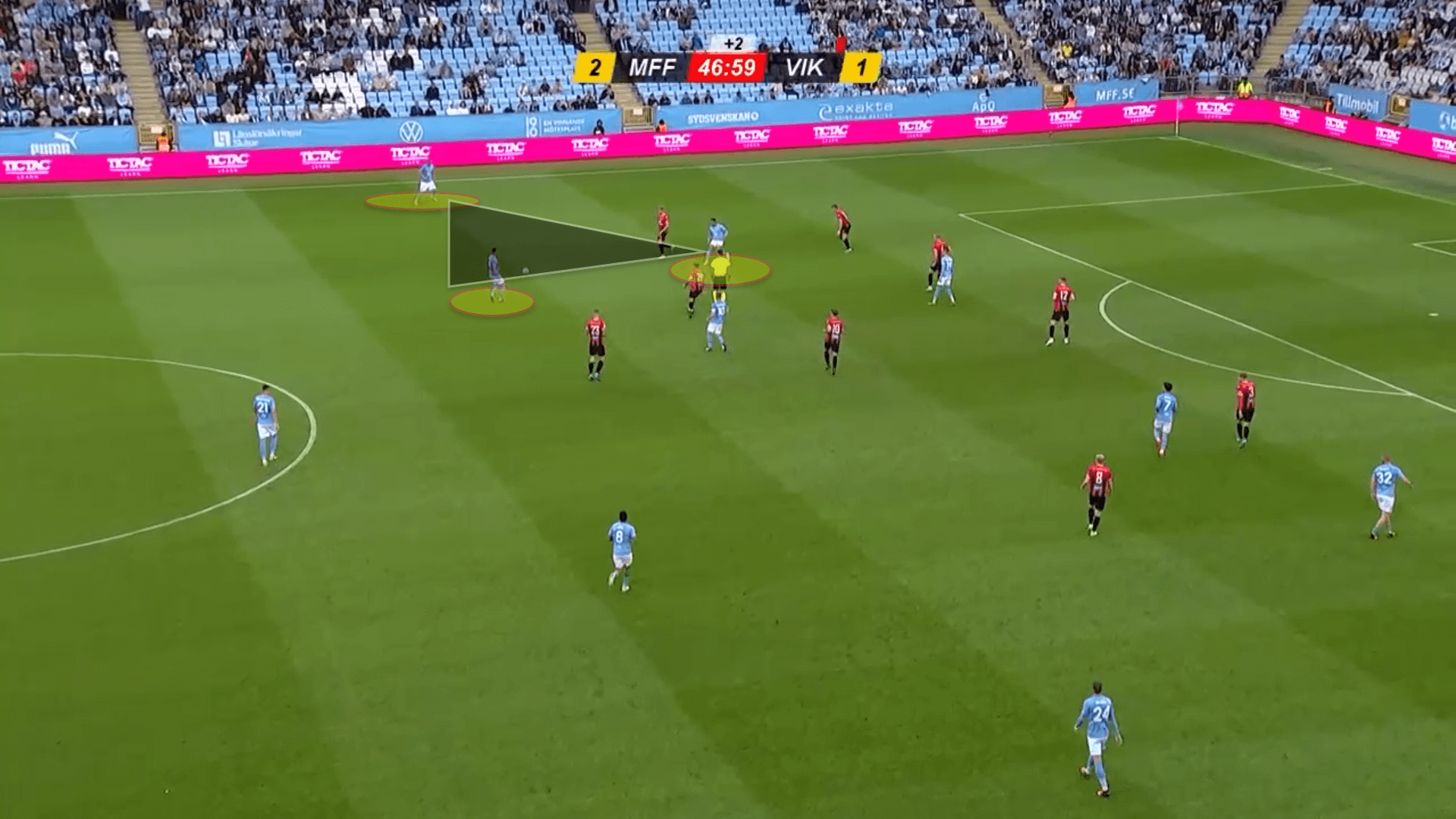

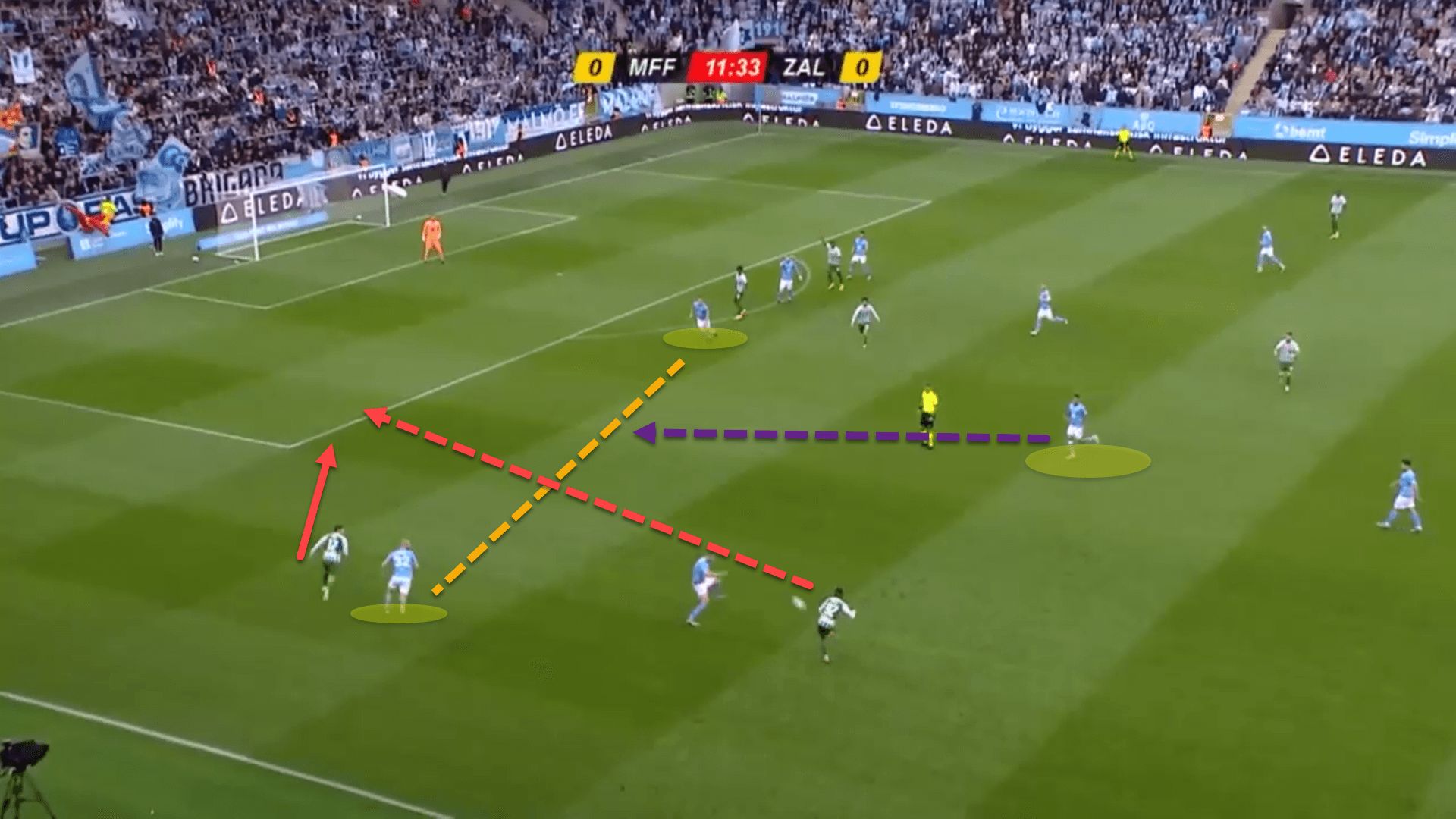

Using the example above, Žalgiris were able to easily get in behind Malmö’s backline by splitting their right-back and right centre-back.

In this instance, either the three other defenders should have stepped across to close the gap to the fullback or else the nearest midfielder should have dropped off into the space, blocking the passing lane. Neither of these things happened. Malmö’s defensive line parted ways like the sea did for Moses.

But these weren’t just seldom moments in a couple of games. They were a frighteningly evident continuum when watching Malmö defend in the deeper areas of the pitch.

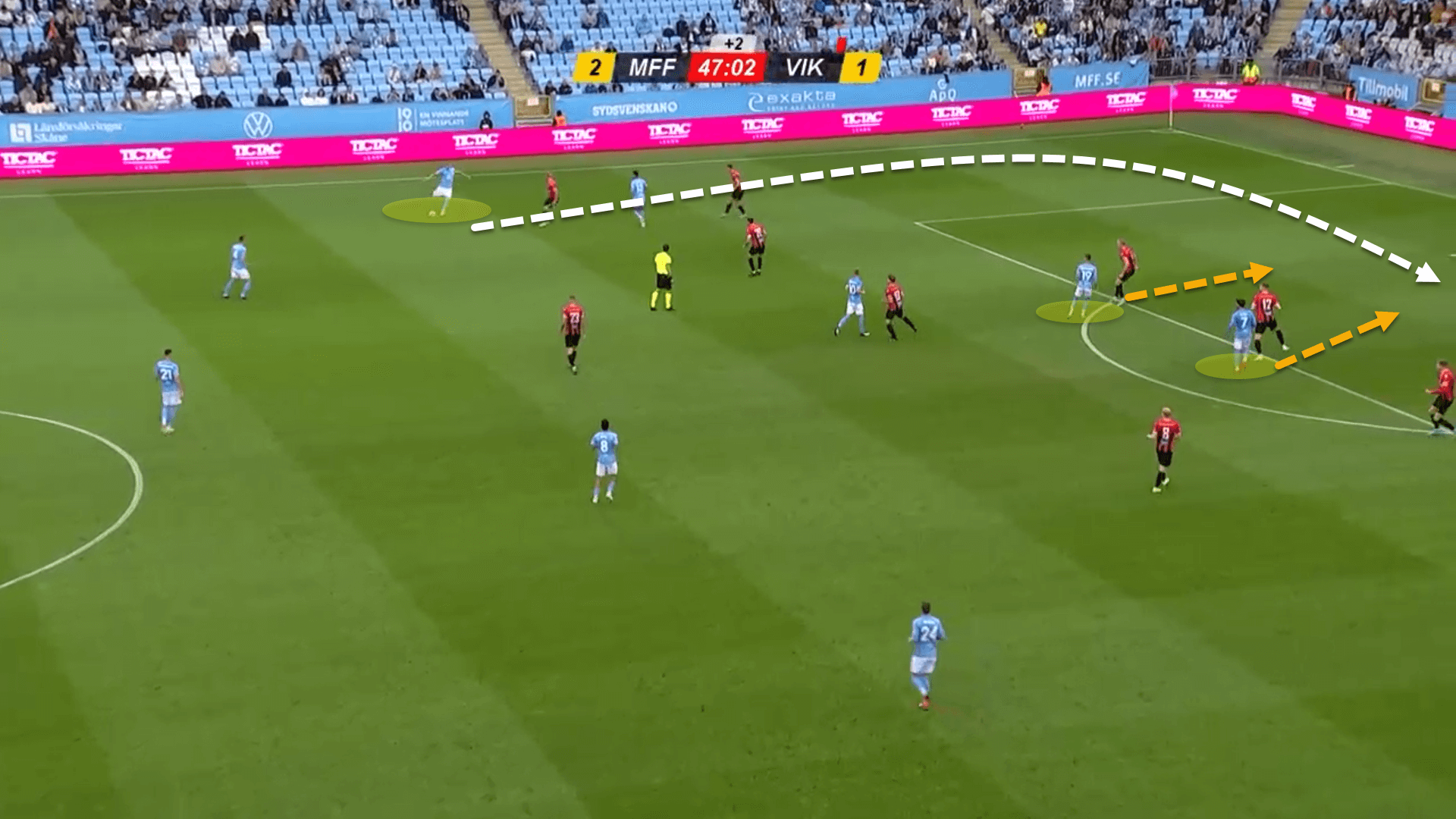

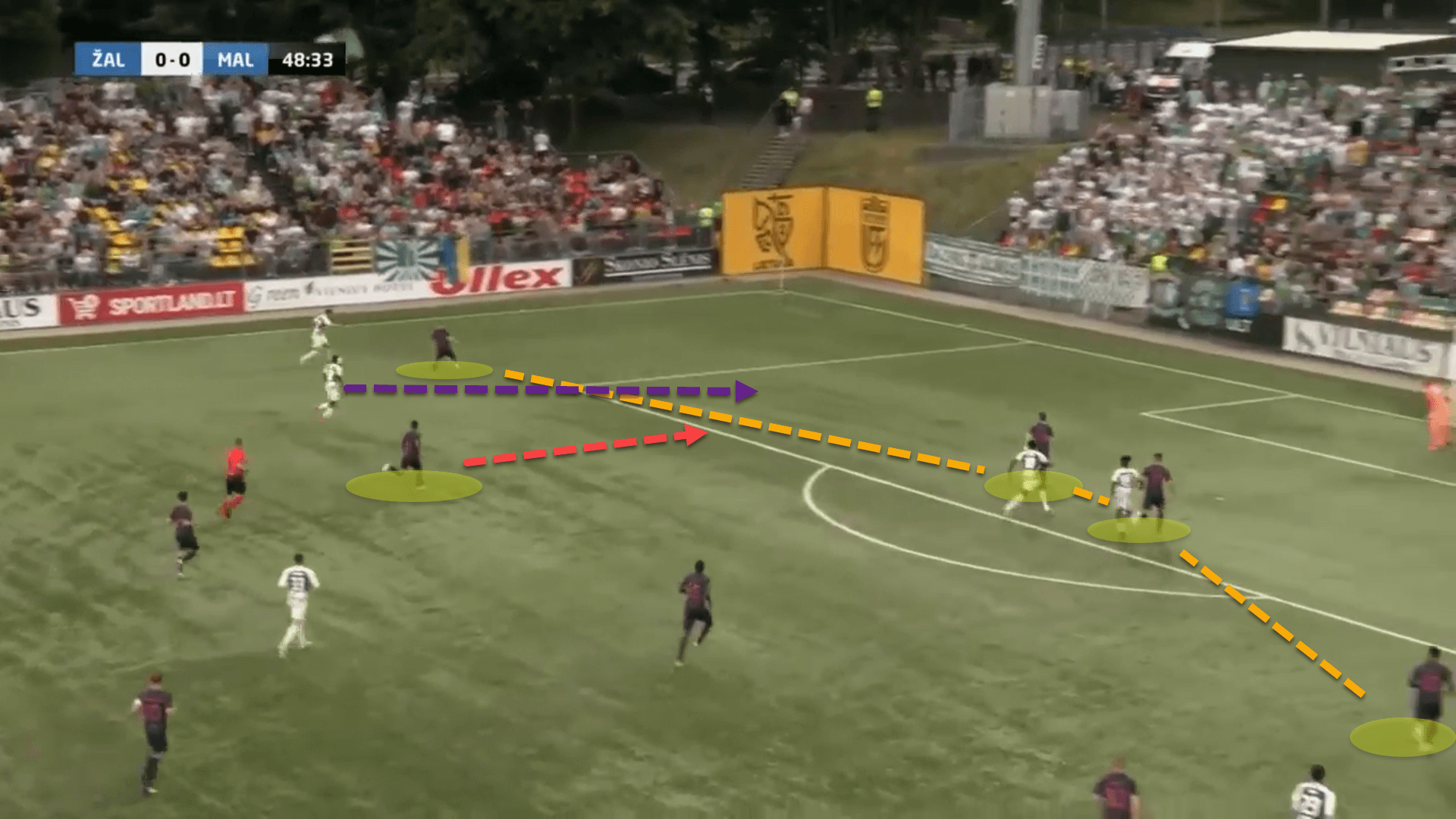

Again, here, Malmö’s right-back has stepped across. The three other defenders are holding their positions in the box to defend against the opponent’s two strikers. This means that the nearest midfielder needs to plug the gap. They didn’t.

By the time their compactness had been successfully restored, it was too late as the ball-carrier struck his shot beautifully into the top-right corner to open the tie’s scoring.

This was a structural issue from Milojević’s tactical setup. However, common sense needs to play its part.

As much as we like to discuss football as if it is a strategic board game like chess, the reality is that players need to make intelligent decisions on the pitch at the right moment. Unfortunately for Milojević, a lapse in common sense and communication in vital moments from Malmö’s players against Žalgiris cost the gaffer his job.

Dealing with long balls

Another problem area for Malmö during their feeble Champions League run was how they dealt with aerial balls from the opposition.

When defending against a long ball, it’s of vital importance that one defender steps out of the backline to challenge in the air while the rest of the defenders drop off and narrow themselves closer together.

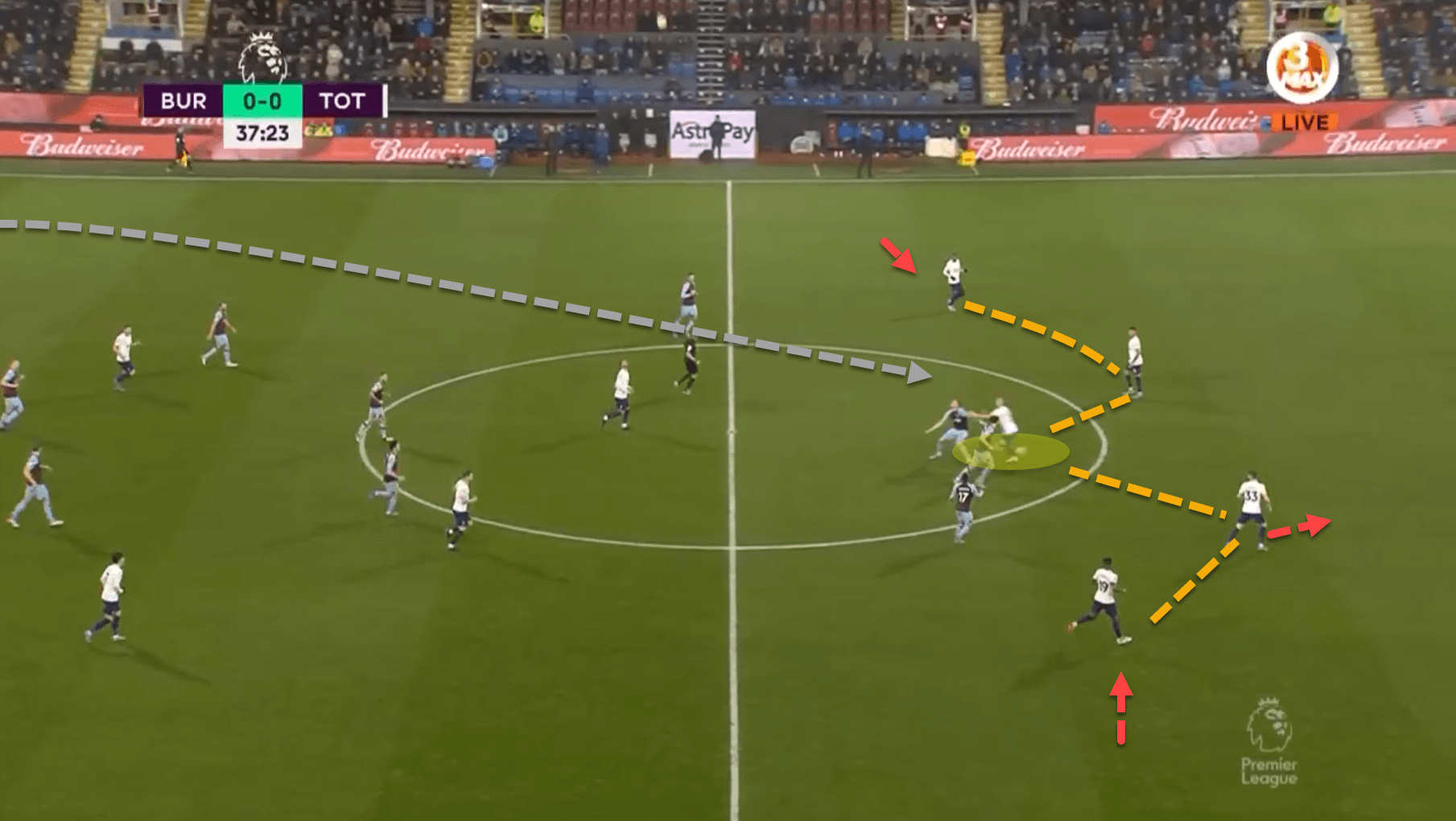

This image is a perfect example of how to defend against a long ball. The Tottenham Hotspur central centre-back steps out to challenge the Burnley centre-forward. Meanwhile, the remaining four defenders from the back five move closer and drop slightly so to be ready in case one of the attacking players make a run in behind.

However, regarding Malmö, the defenders were far too individualistic when defending these types of direct passes from the opposition, running the risk of being exploited with flick-ons in behind.

Look here for instance. Malmö’s central defender from the back three has stepped out to challenge in the air. The two other centre-backs are way too far, meaning a heavy burden is placed on the defender to ensure that he wins the aerial duel.

Malmö are excellent in their aerial duels, it must be said, winning 58 percent in the Allsvenskan this season which is the highest of any side in the division. However, it’s the other 42 percent that was more worrying under Milojević.

Winning the first contact is not as important as winning the second. A team can lose the duel on the first contact once the correct structure is put in place to sweep up the second. However, in the previous image, the centre-backs are too distant from each other and haven’t dropped enough to prepare for the possible flick-on.

Conclusion

Perhaps Milojević’s sacking was slightly premature. Of course, Malmö’s disappointing and early Champions League exit was the main reason and was something the board couldn’t simply overlook. However, the side were just three points off the top of the Allsvenskan when the club announced their decision.

Regardless, that’s how the cookie crumbles in football. These three issues discussed weren’t ground-breaking but were some of the main tactical reasons behind Milojević’s fall as Malmö boss.

Comments