Carrying on from the last article in this series, this tactical analysis will look at how the best teams in Europe attack the far post zone from corners. To do this, I used data (with help from Marton Balla) to identify which teams attack this zone with the greatest success, before then analysing every corner to see how each team utilises the back post effectively. The number of corners taken in each zone, as well as the general efficiency was taken into account, with the last article covering the front post and the general efficiency of teams in Europe’s top five leagues. The whole series involved the analysis of over 2000 corners and provides the behaviour and structural trends the best teams display in each zone.

The far post data

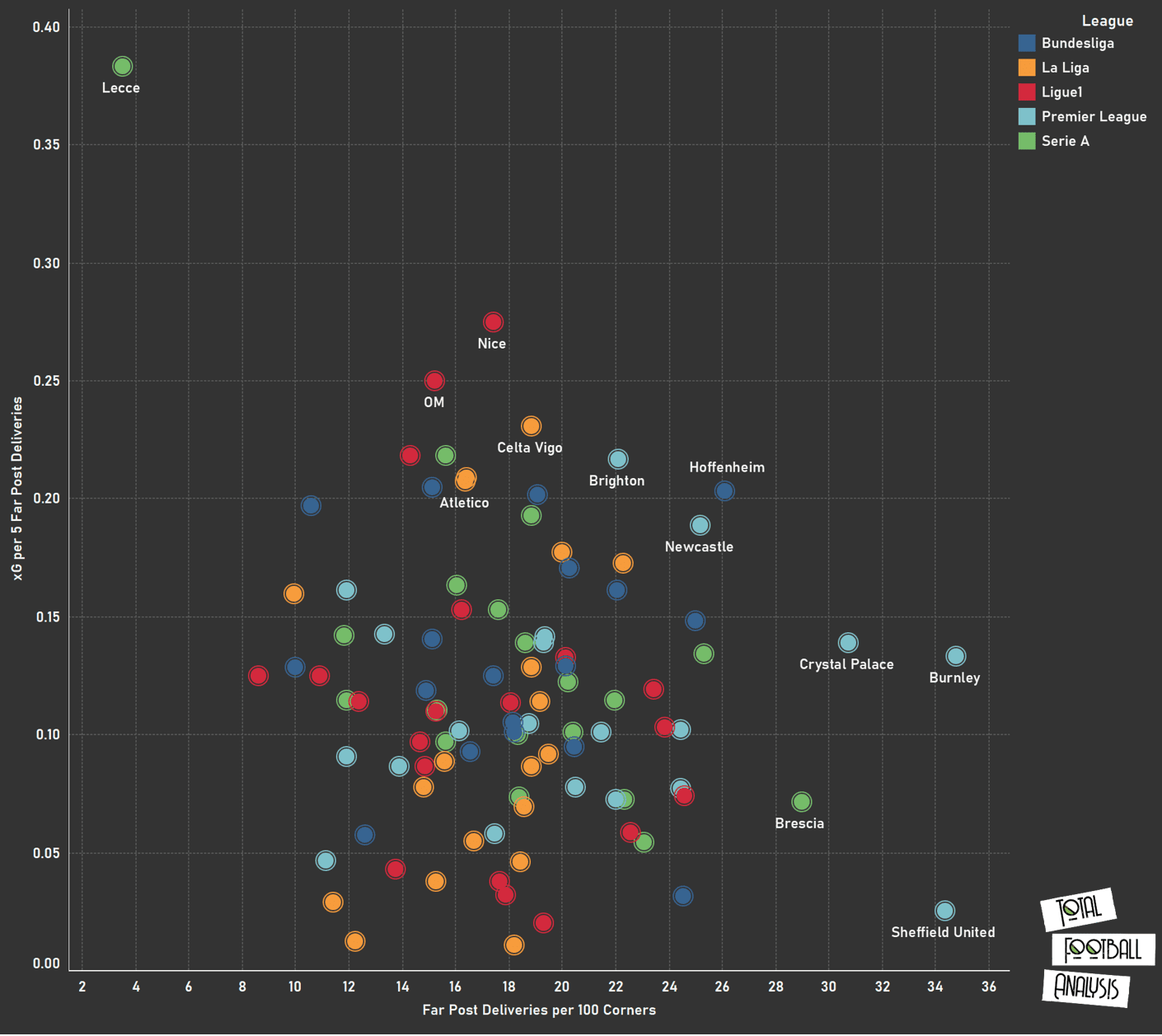

To give a general outlook on teams who use the far post most effectively, we plotted the number of far post deliveries per 100 corners against the xG generated per five far post corners. This gave an overview of who used the zone lots, and how efficient they were in their use. From the teams identified in the graph below, their overall xG generated was considered, as well as the number of shots taken.

We can see in the graph below that the English teams mainly dominate this area, with Crystal Palace, Burnley and Sheffield United all attempting the most deliveries into the far post. Sheffield United show as being fairly inefficient on the graph, as they attempt 34 far post deliveries per 100 corners, and only generate 0.025 xG per five deliveries. At the complete opposite end, Lecce clearly have generated a small number of very good chances from very few attempts. In the middle of the pack, the likes of Brighton, Hoffenheim and Celta Vigo are performing well, with this area suggesting teams are not over-reliant on the zone but they still perform well in it. One of the worst teams from the Premier League seen in the bottom left of the graph is Manchester City, with this giving a clue towards the nature of the back post.

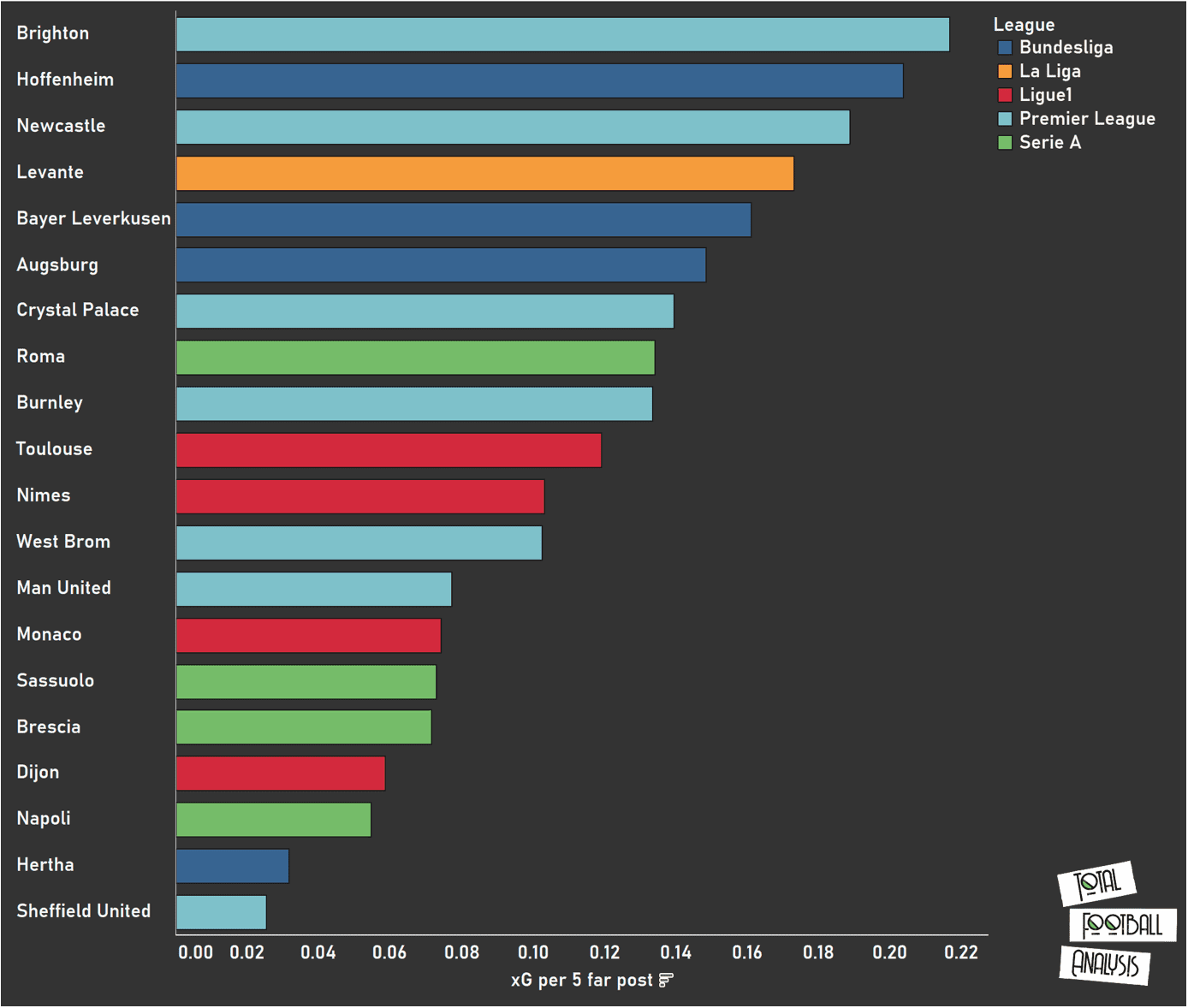

A threshold of the minimum number of far post corners was then used to filter down teams who actively use the back post, as for the purposes of the article we want to find how teams consistently attack the area well. Teams were then placed in order of their xG per five corners, to give further representation of who attacks the zone consistently in the most successful way. We see Brighton come out on top followed by the Bundesliga‘s Hoffenheim.

As mentioned, to create a shortlist of the ‘best’ teams, the following graphs, as well as other basic stats such as shots, were considered. As a result of this, the following four team shortlist was created. Other teams can and will be covered at later dates, although I’m not sure if that will be released as a public article.

- Brighton

- Hoffenheim

- Burnley

- Crystal Palace

The main benefit of the back post

Before we get into the individual trends within each team, we will first look at the main trend which underpins the use of the back post. The back post offers a unique physical advantage due to its position on the pitch and the nature of defending from corners.

Naturally, when attackers attack a corner, they run from deeper and have the goal in front of them. Due to this attackers have the sole responsibility of making a movement to receive the cross, and they don’t have to adjust to track the flight of the ball due to their body positioning. Defenders meanwhile often face the corner kick taker, as they have to track the flight of the ball while also tracking a movement of an attacker. This side on stance and the roles associated with it, are what create an advantage both at the back post and generally against man-oriented opposition.

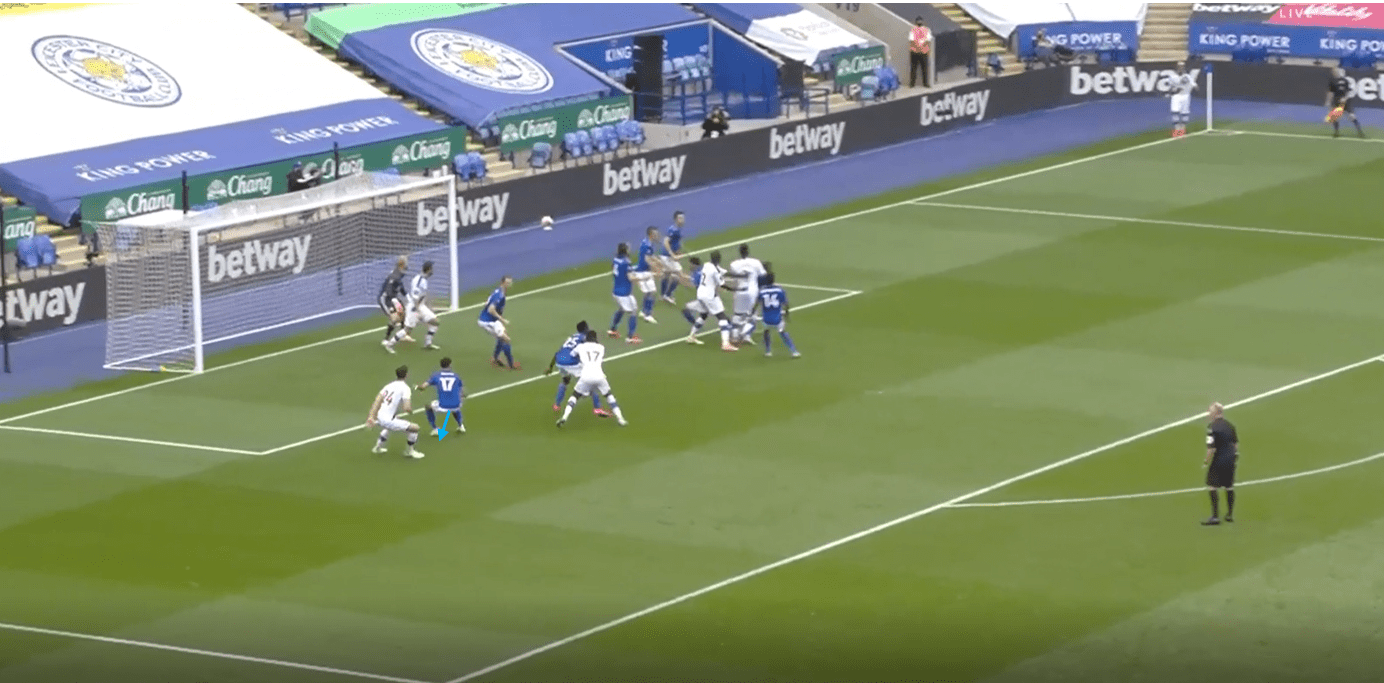

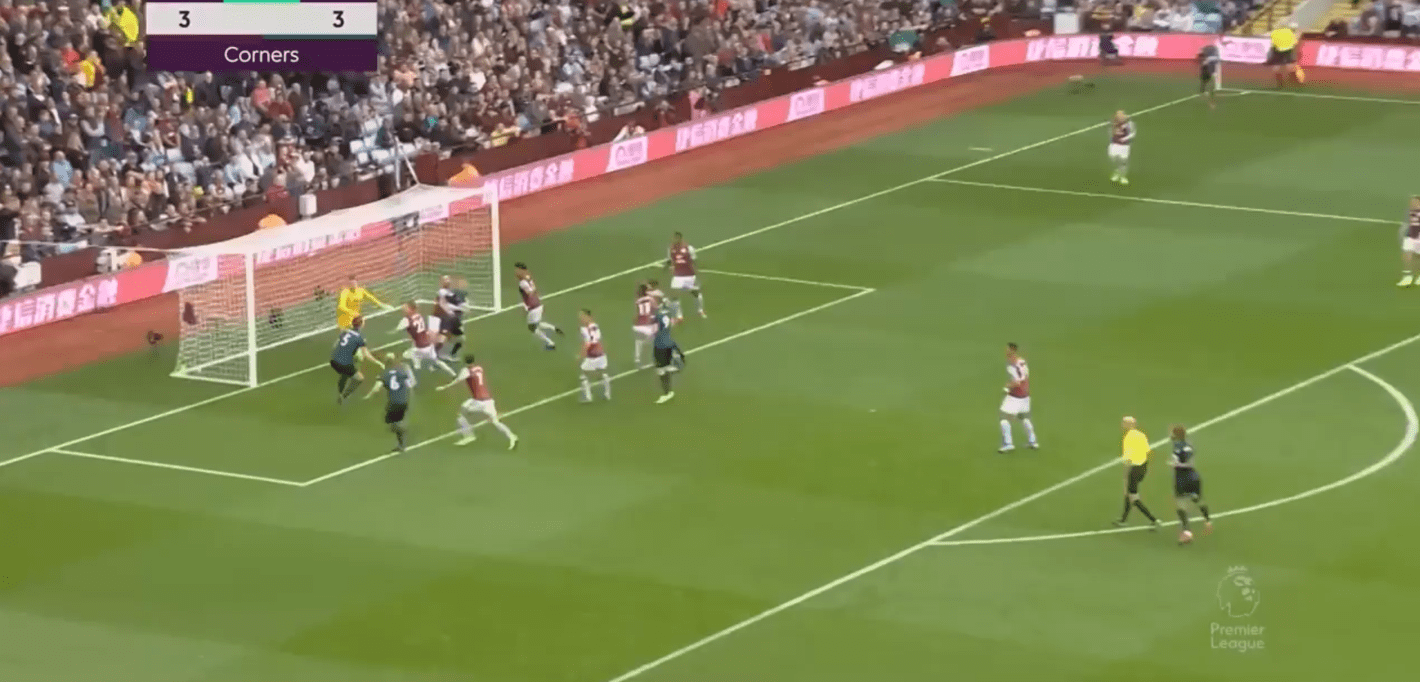

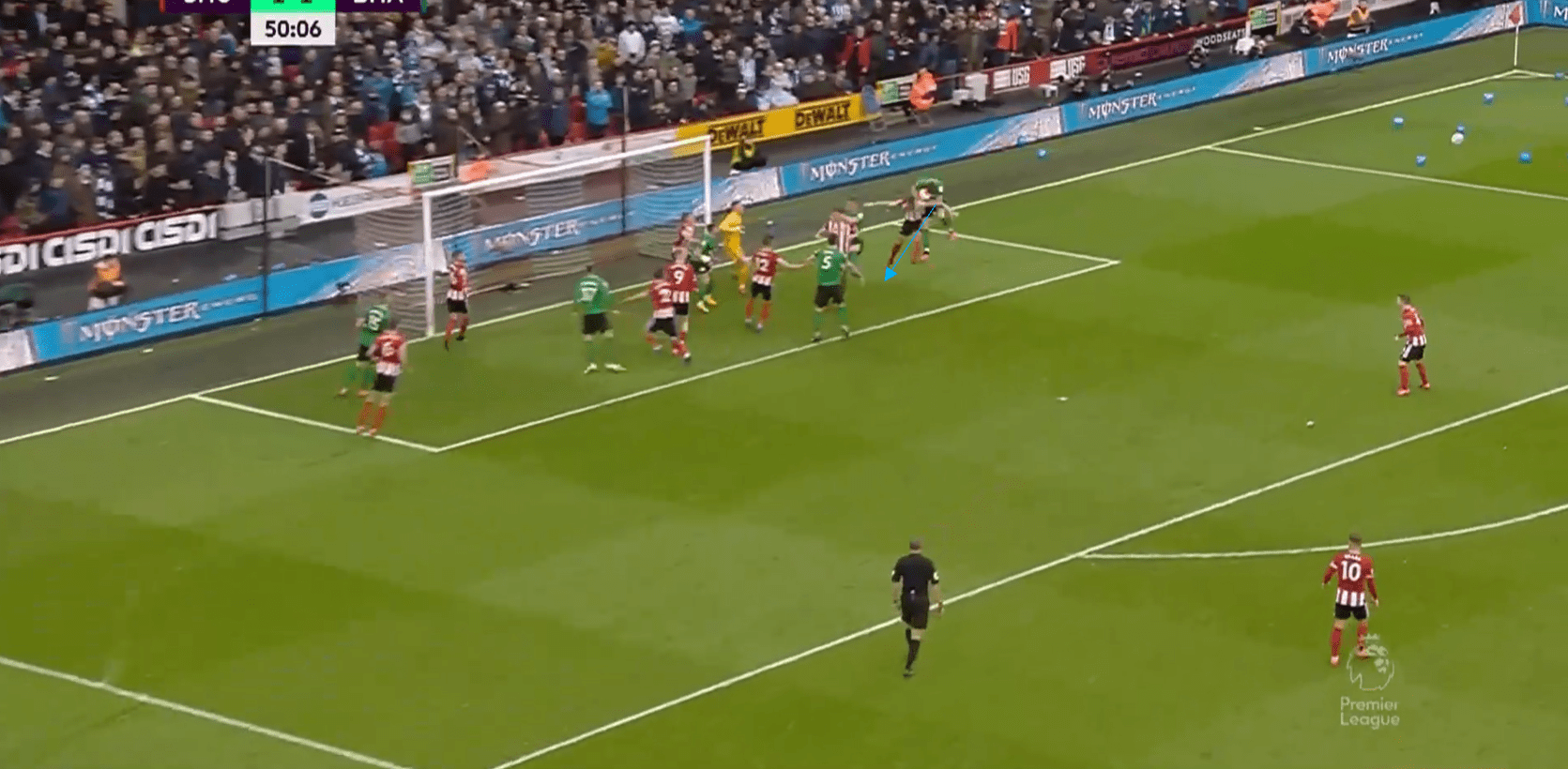

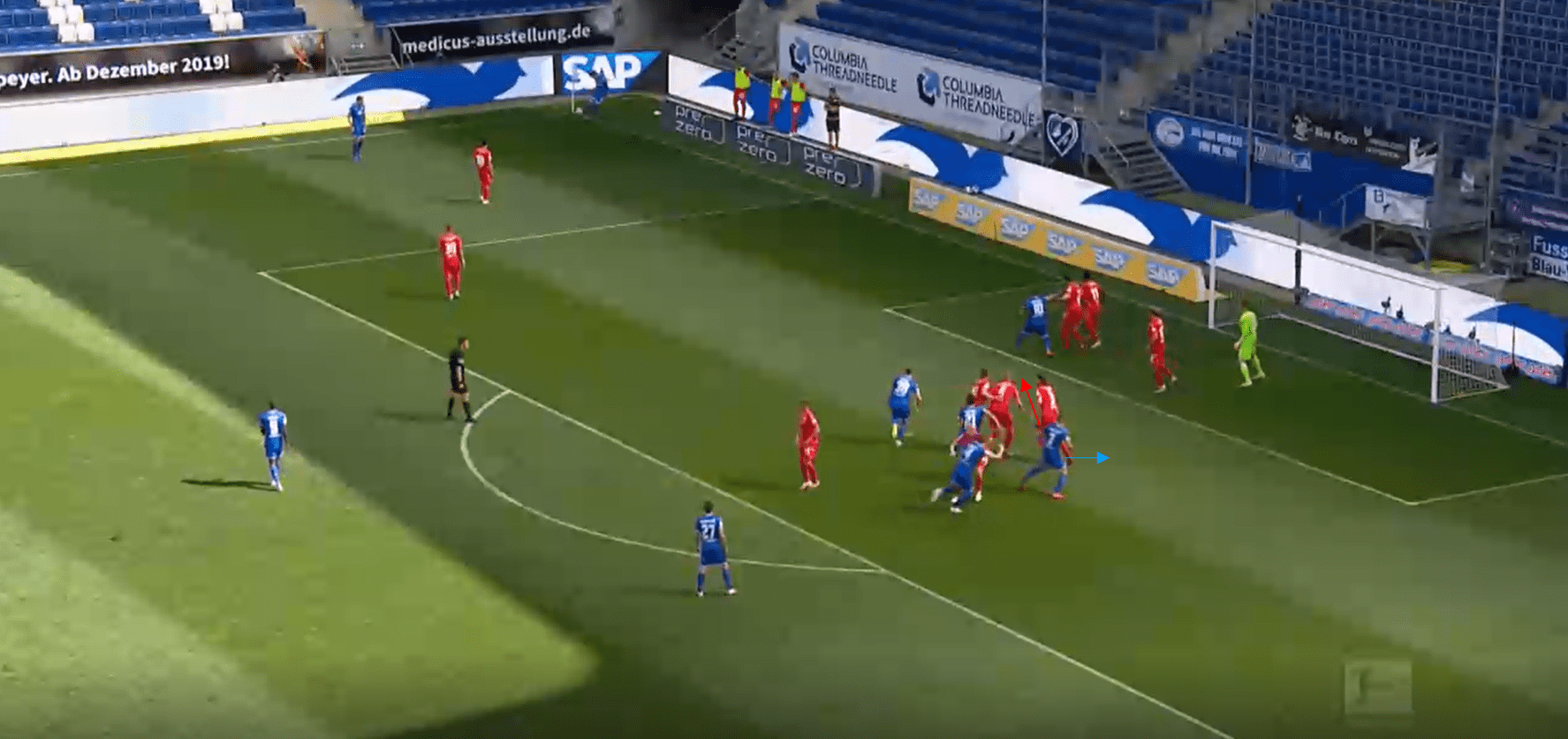

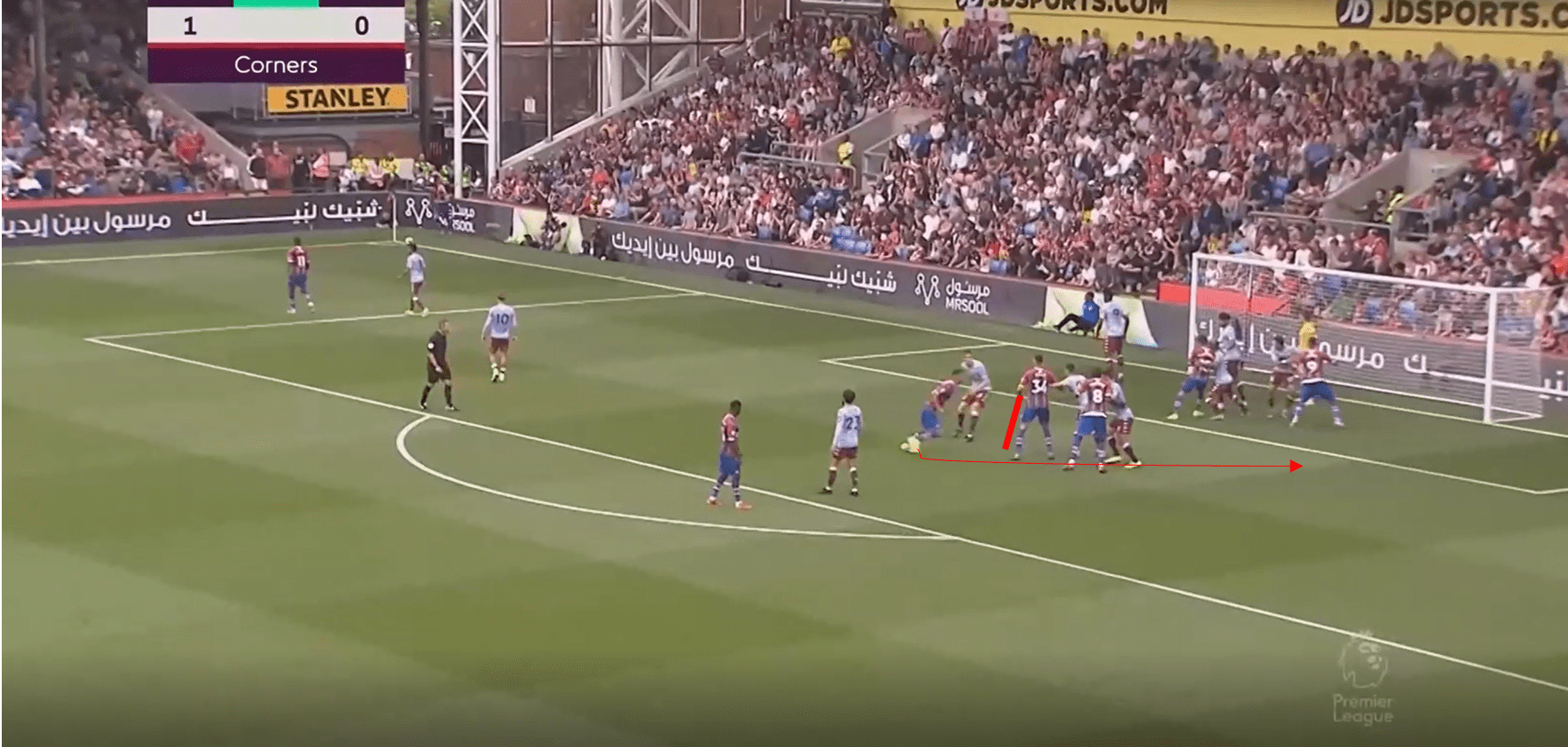

Deliveries to the back post therefore often result in a scene like the one below with Crystal Palace. Markers of players at the back post have to shuffle backwards in order to compromise between getting close to an attacker at the back post while still tracking the flight of the ball. This backwards movement is pretty inefficient and slow, and the jump to challenge the header has to be made backwards, which seems to impact the height of the jump. Therefore, when an attacker arrives at greater speed, running towards goal, with generally a greater jumping height, they have an advantage over the marker and more often than not they win the header.

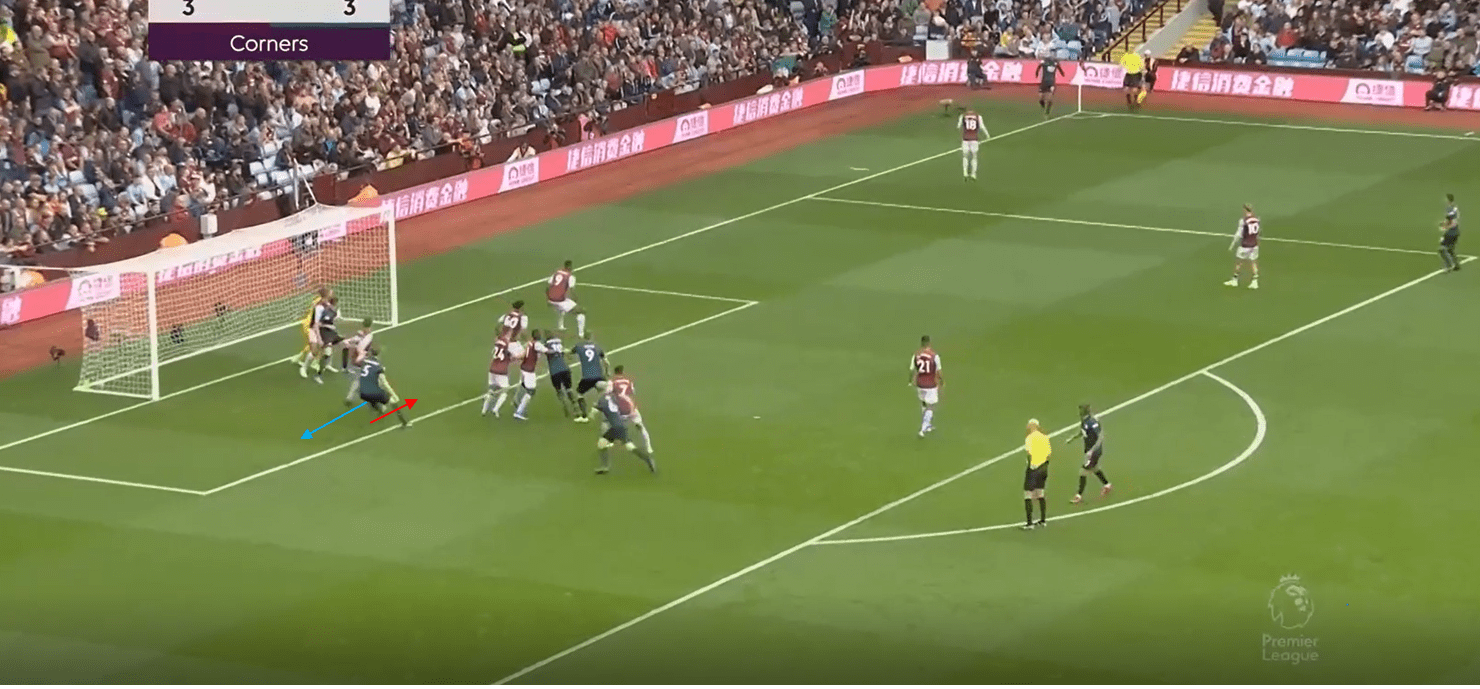

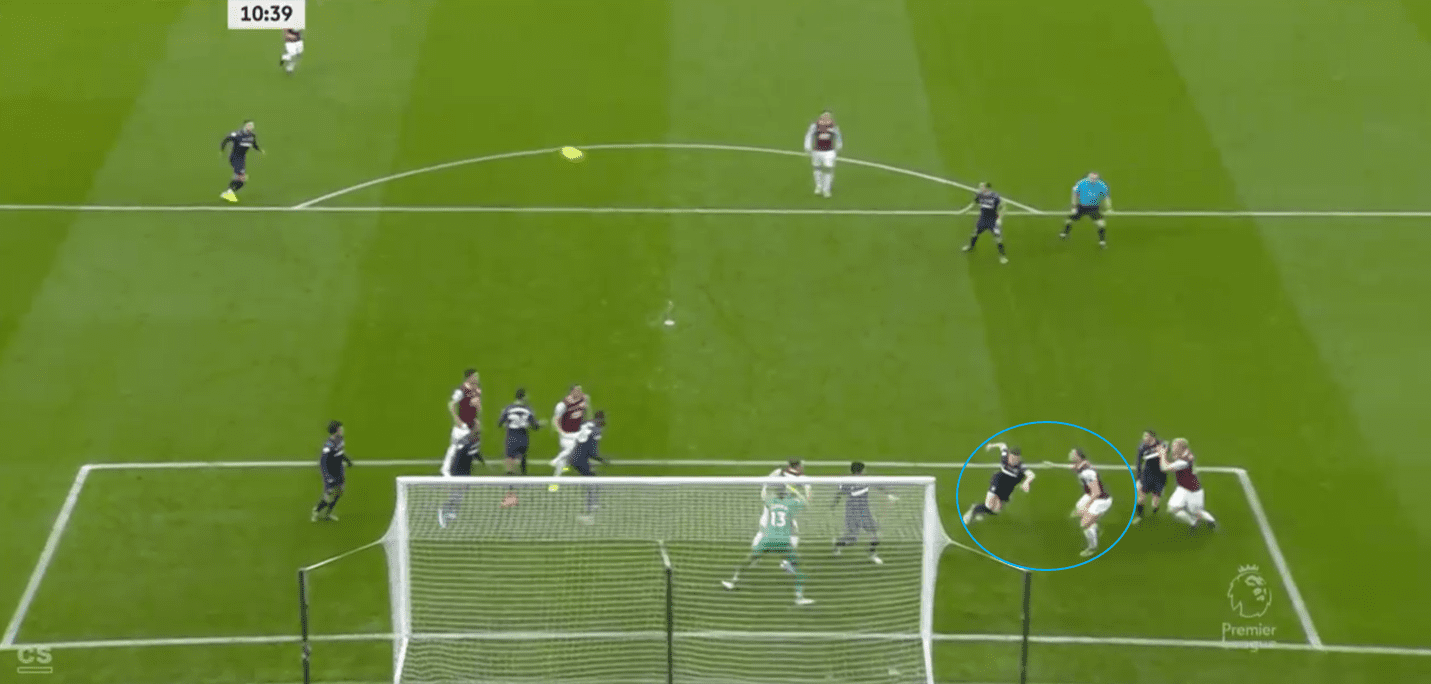

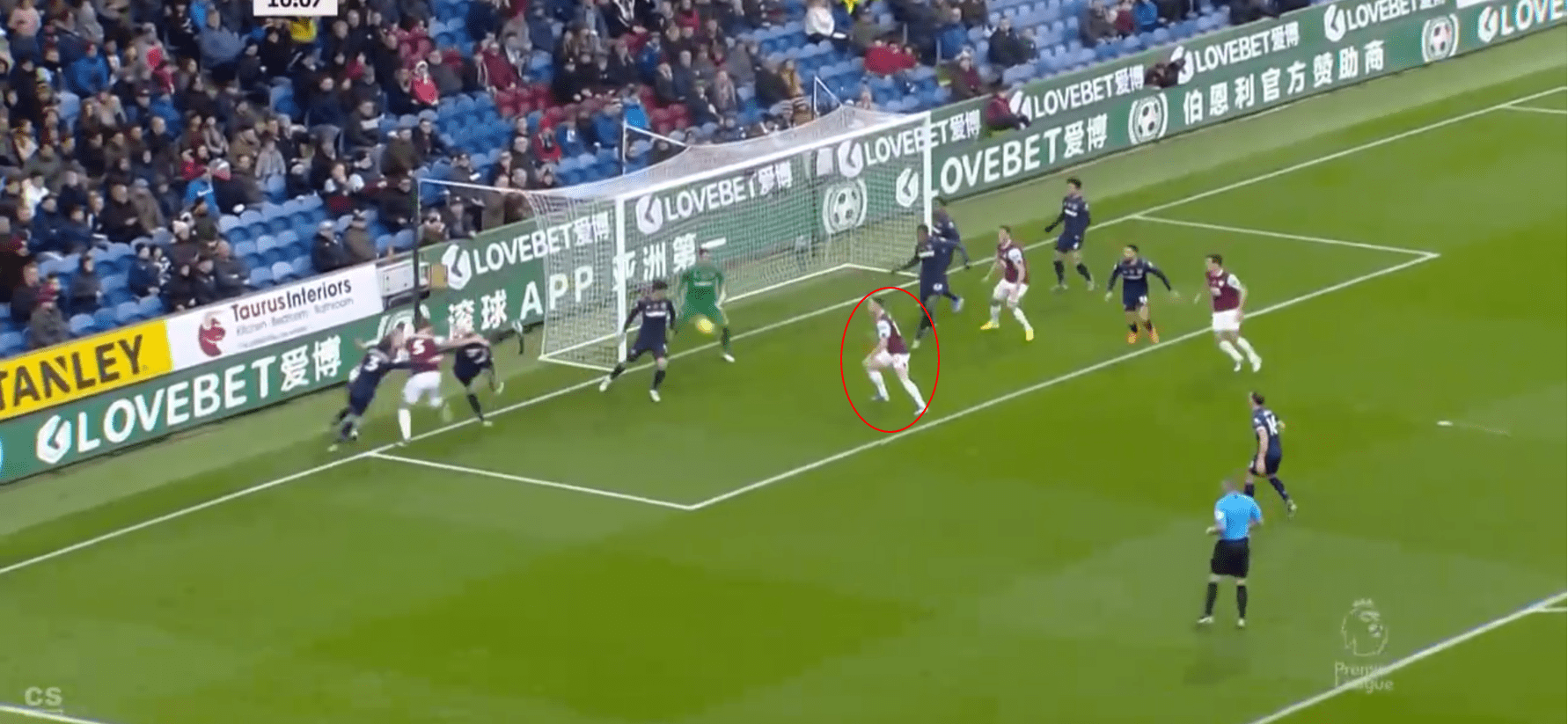

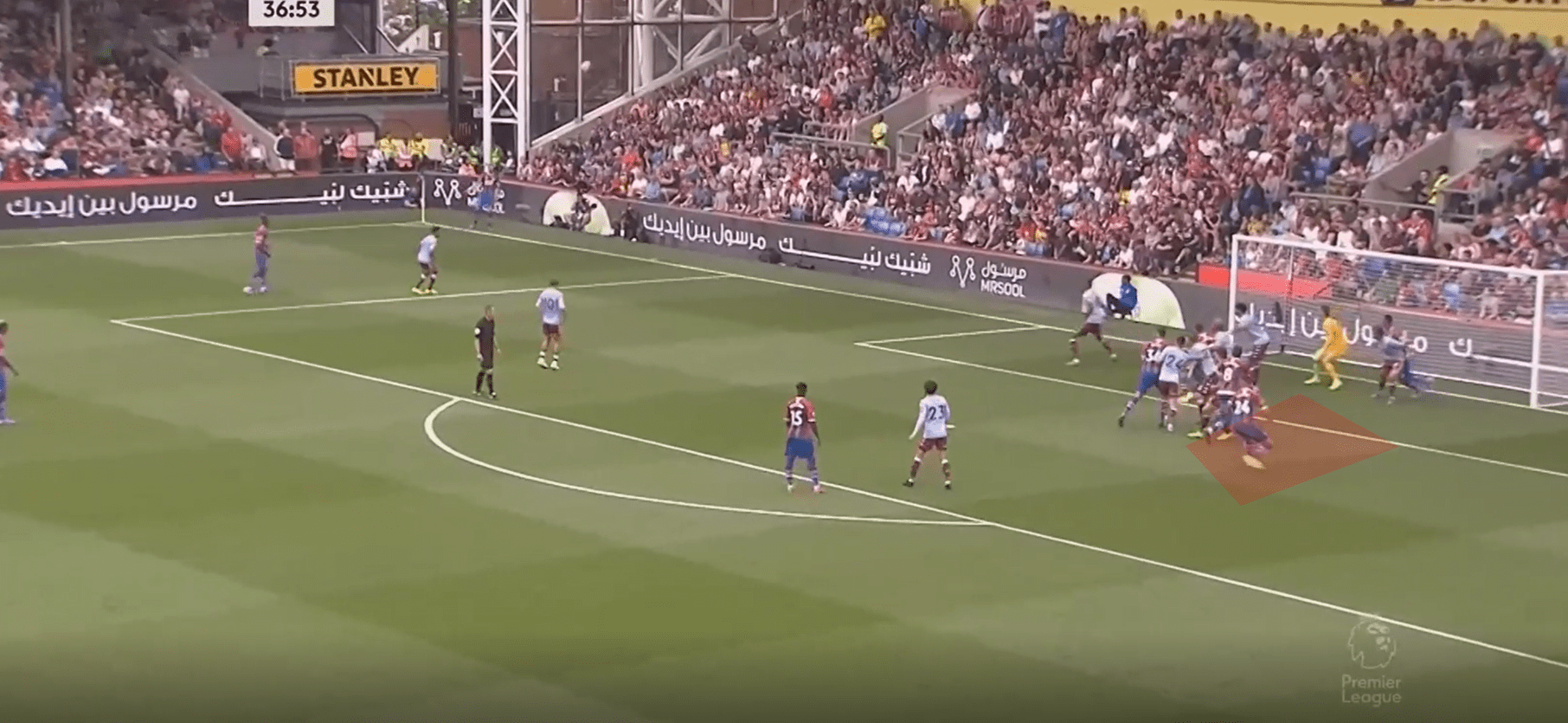

Due to the defender having those two responsibilities of tracking the flight of the ball and marking a man, consistent changes in direction by the attacker can have a great effect. We can see an example below involving Burnley, where Tarkowksi starts at the back post and makes a movement forward towards the centre. He and his marker have the same body orientation, and both are watching the corner taker.

With the defender’s eyes on the corner taker and the ball, Tarkowski changes direction again by falling back towards the back post. Because the defender is watching the ball initially, this movement by Tarkowski allows him to create some separation and confuse his marker. It is worth bearing in mind the defender is always reacting to the attacker, and so the constant changes in direction which affect the speed and momentum of the defender are vital to create separation. The defender here completely turns his back in order to find the attacker again, and so he is no longer aware of where the ball is.

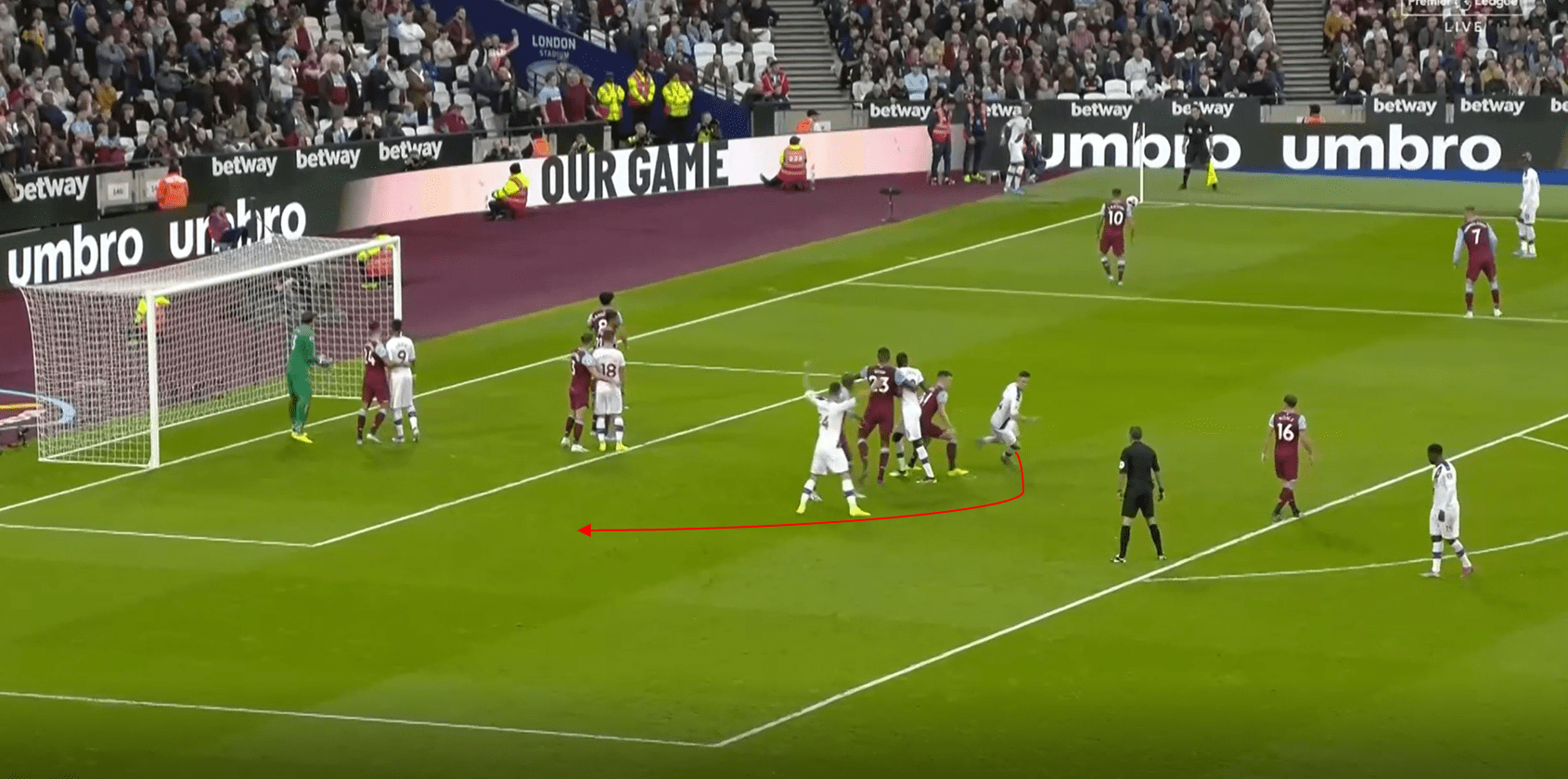

We can see in this example here Chris Wood changes the direction of his run and adjust according to the flight of the ball. His marker is disrupted by this and struggles to read and react to the changes in direction, and so he eventually just loses his balance and can’t cover his marker.

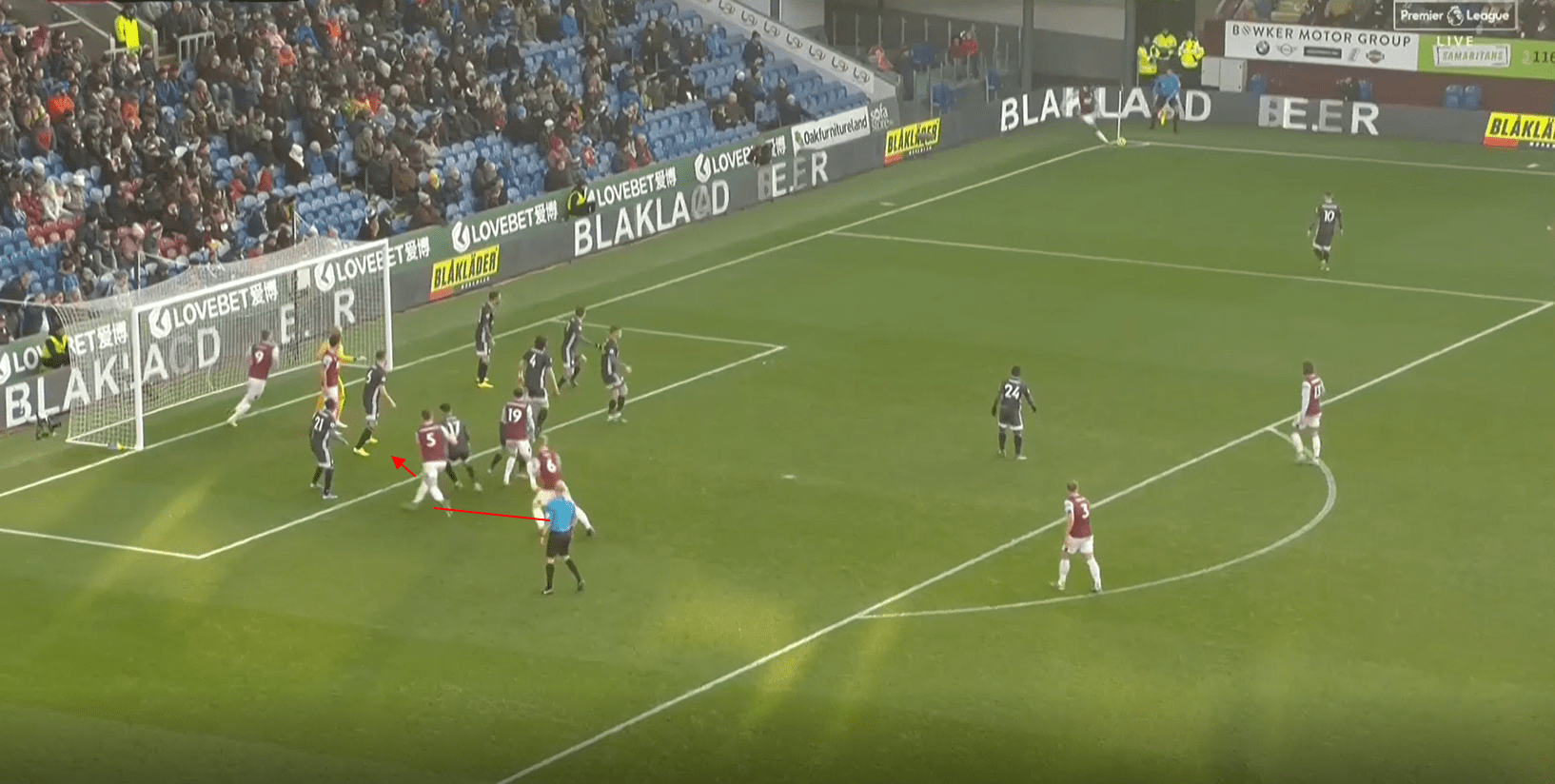

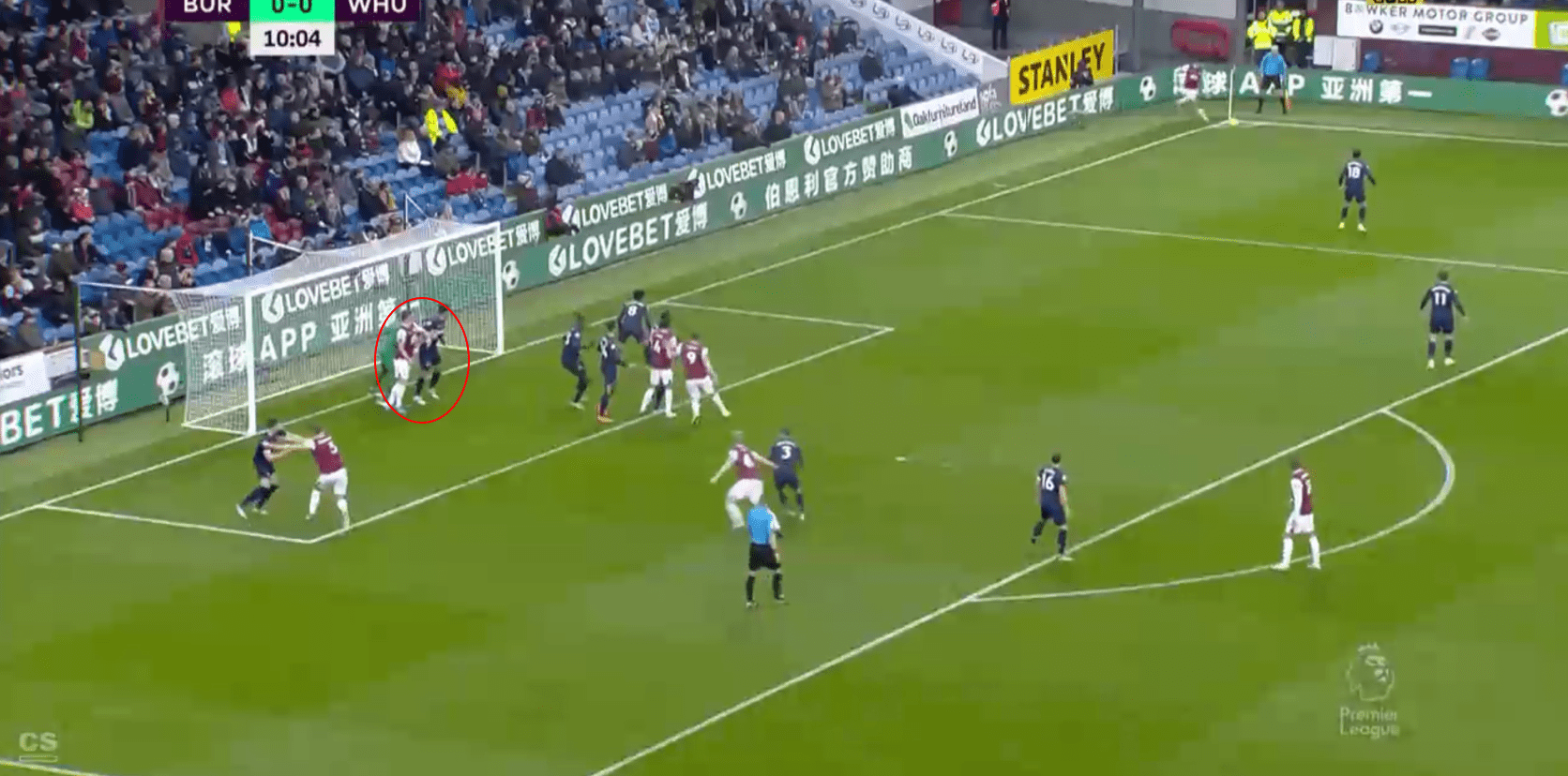

In this final example here, just after the ball has been kicked, Tarkowksi moves forwards from the back post again, where his marker follows him quickly.

Tarkowski uses the momentum of the defender against him, as when the defender moves towards him, Tarkowski makes a movement in the opposite direction again. The defender therefore can’t stay with the attacker, and Tarkowski gets a free header at the back post. Burnley consequently score for reasons we will go into in detail shortly. We’ll now look at the individual trends the best back post teams display.

Burnley

The first team we will look at is a team who use a mix between the back post and GK zone frequently, which may at times account for slightly lower xG than I would have perceived from watching their footage. Burnley are an obvious physical threat from set-pieces, and when this is combined with intelligent movement, they thrive at the back post.

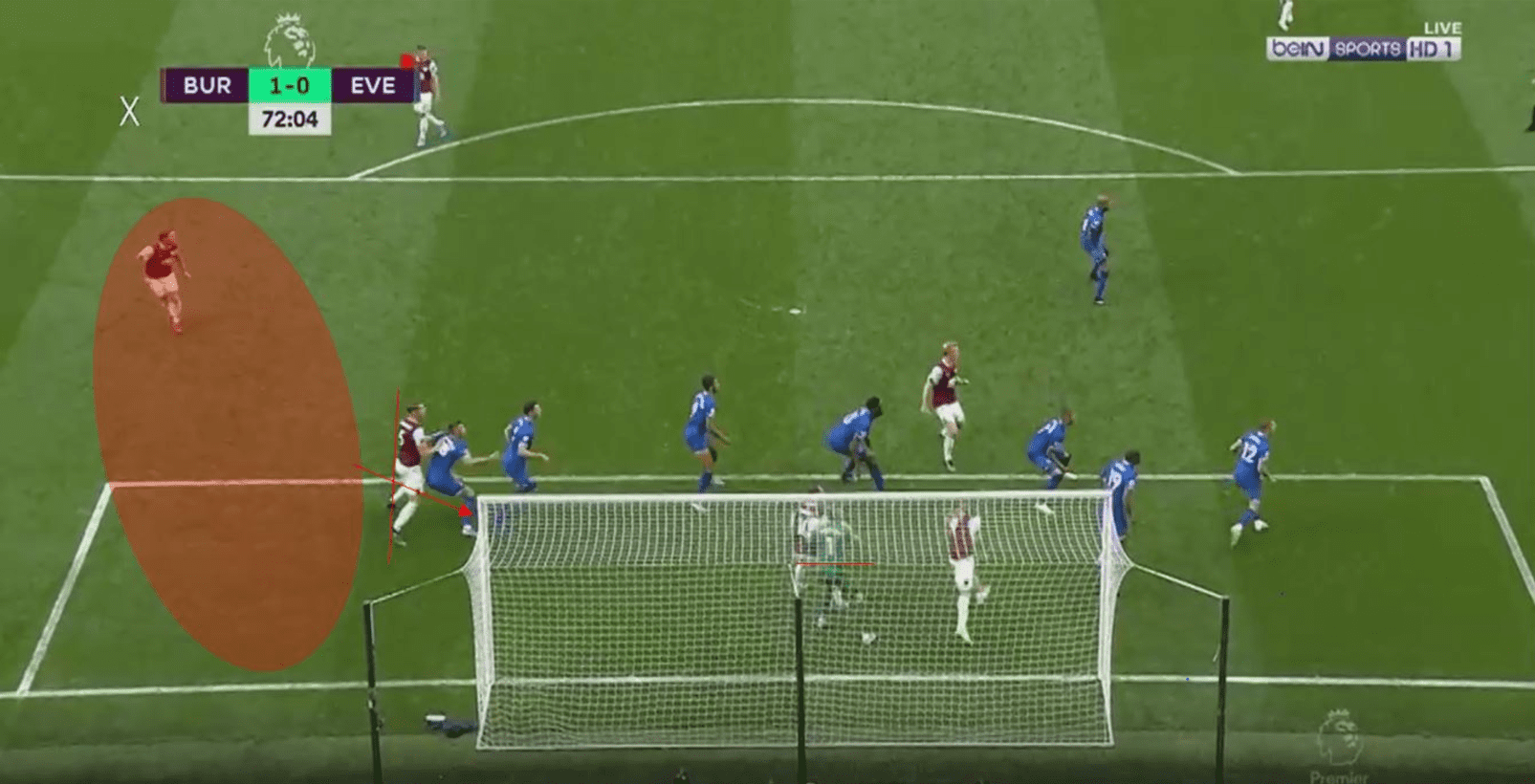

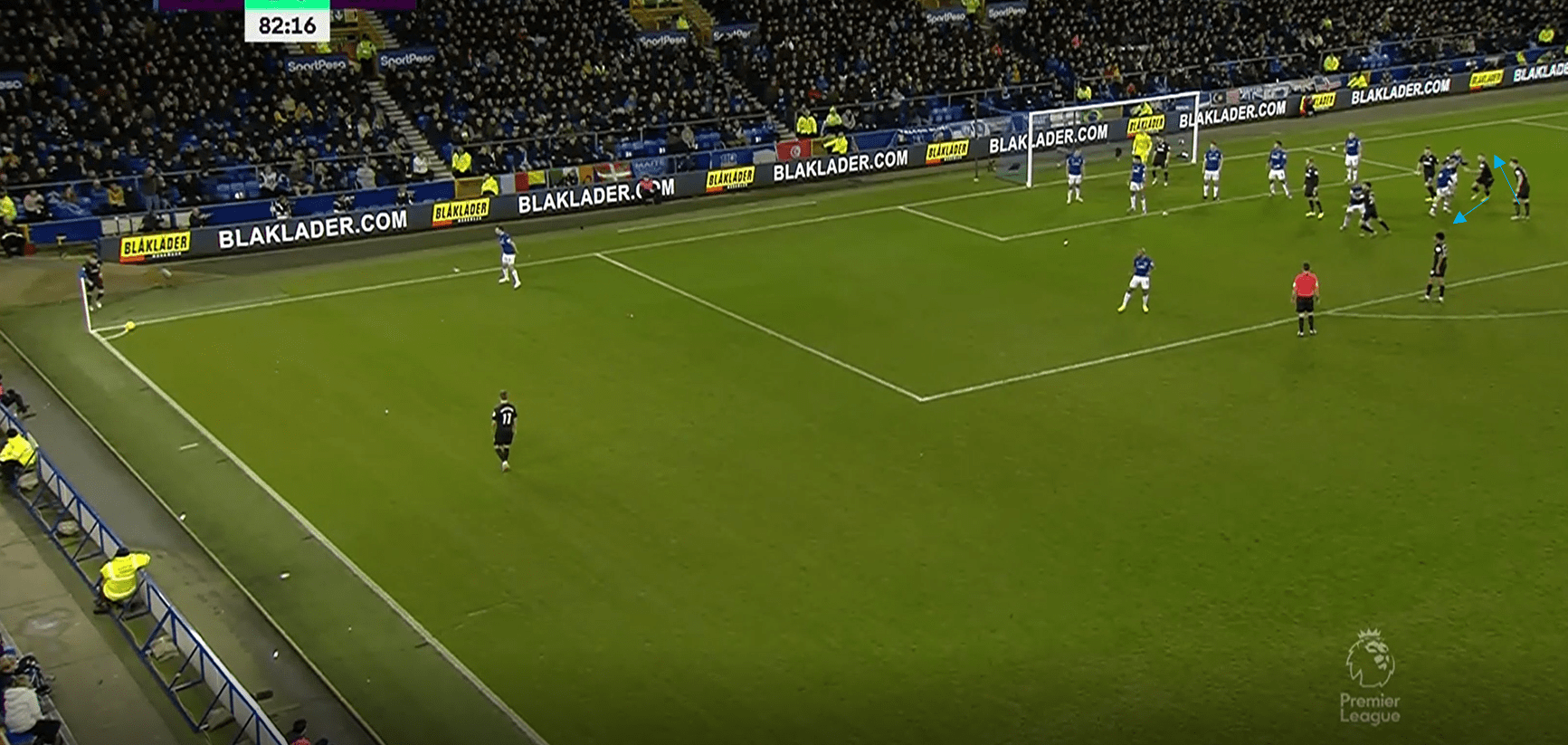

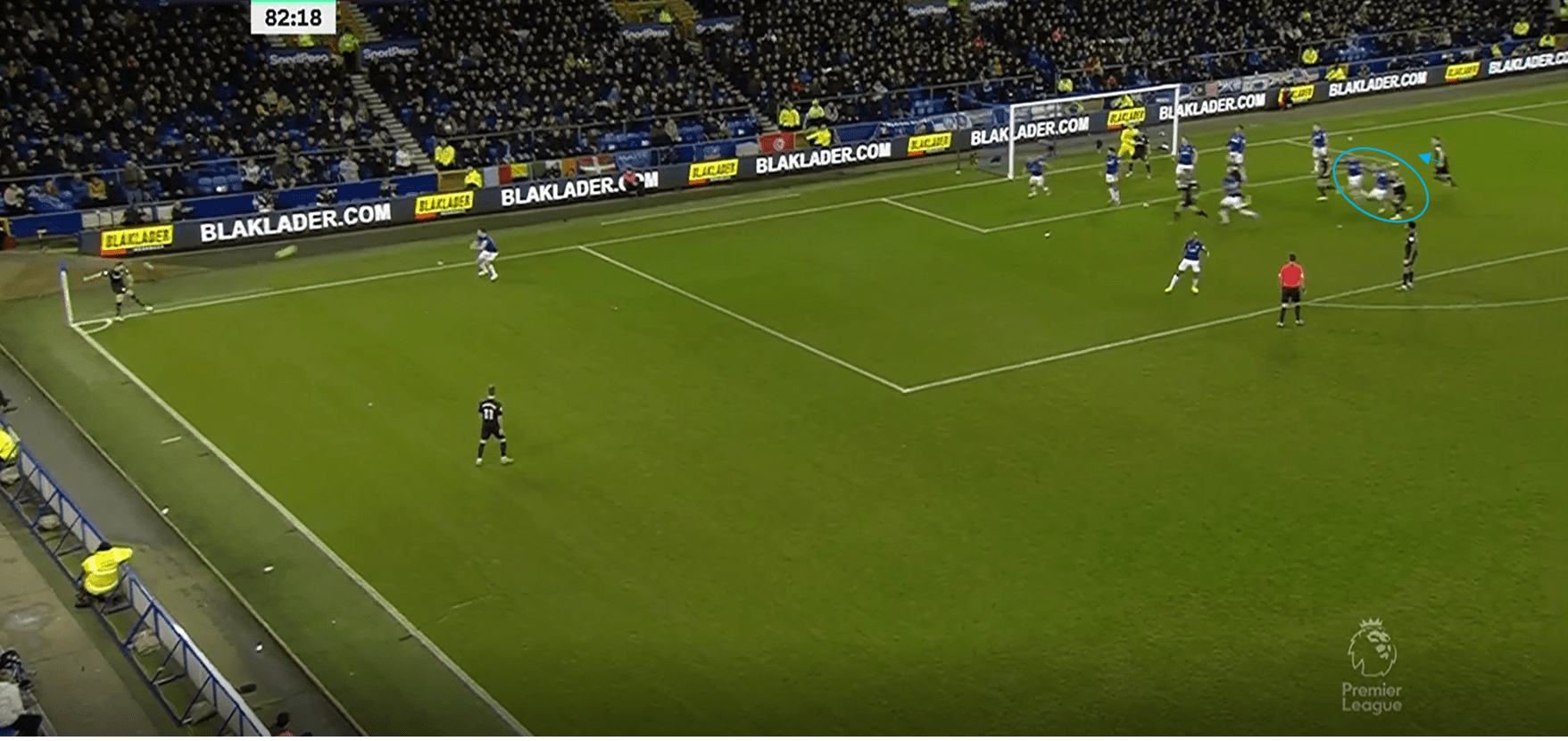

One of the main features of Burnley’s play is their use of far side positioning on their markers, which can be used to block access to the back post. The most obvious example of this came very early in the season against Everton, with James Tarkowski standing at the back post and rather than moving towards the net, he holds his position on the far side of the marker. A deep runner then moves towards the back post, and the closest Everton player cannot adjust due to the block placed.

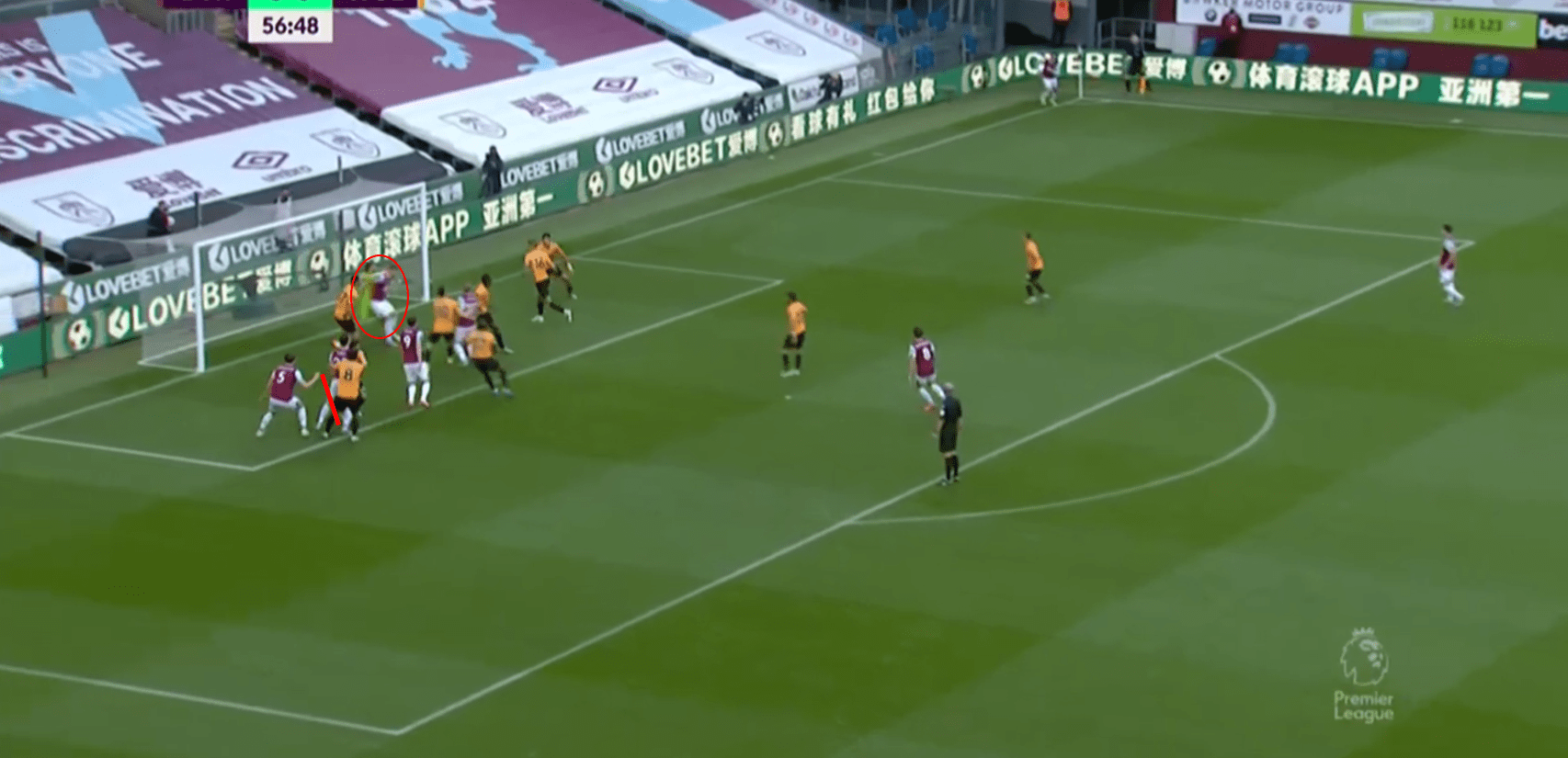

In a more common situation, Burnley will often stagger their runners so that they arrive at different times. This allows for the first runner to be marked tightly and set up a block, while the deeper runner then arrives and looks to take advantage of the space created by a block. We can see an example here where a player initially runs to the back post and stays on the far side of his marker. Tarkowski then arrives later, but the opposition struggle to adapt due to the positioning of that initial player. The goalkeeper is also often blocked in order to restrict their movement and prevent them from pushing out to claim deeper deliveries.

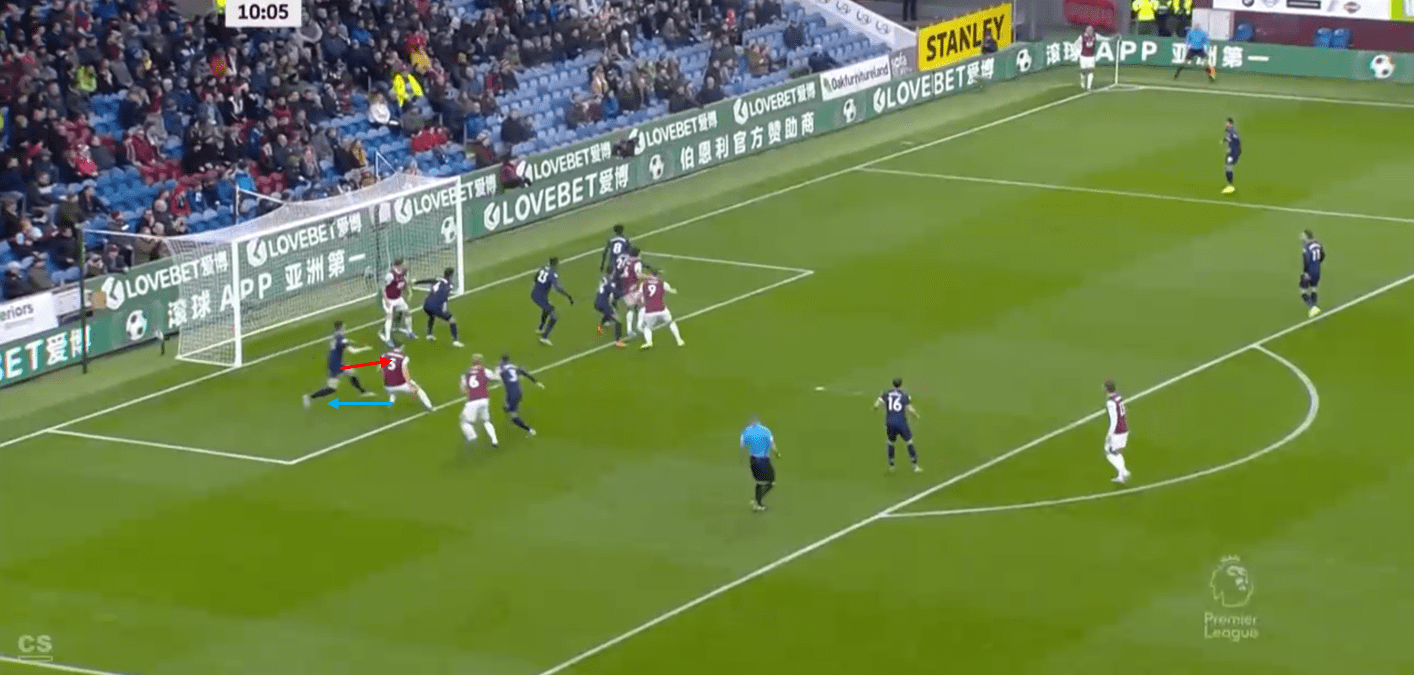

We can see in this example below the movements of two Burnley players are staggered to create the same effect. Tarkowski starts higher and moves first, occupying the man marker and staying on the far side. Tarkwoski stays back initially, before then also making a movement into the back post.

The deeper runner (Ben Mee) then has a free run up towards the goal, and with no player between him and the back post zonal marker, he is able to generate a dynamic advantage. When the ball is delivered towards the back post, the defending team will look to fall back and react to where the ball is dropping, but virtually all the Burnley players position themselves on the far side of their markers, with the goalkeeper blocked again. As a result, Burnley score from a rebound from the back post header.

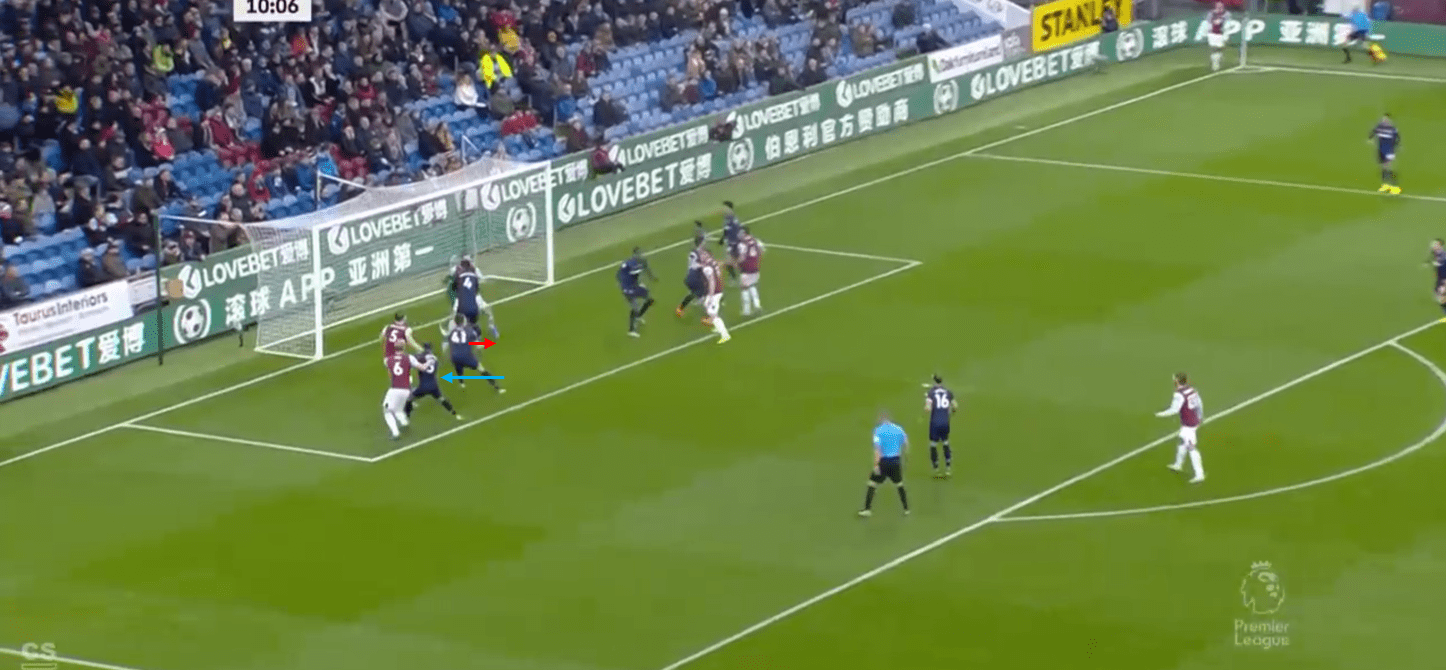

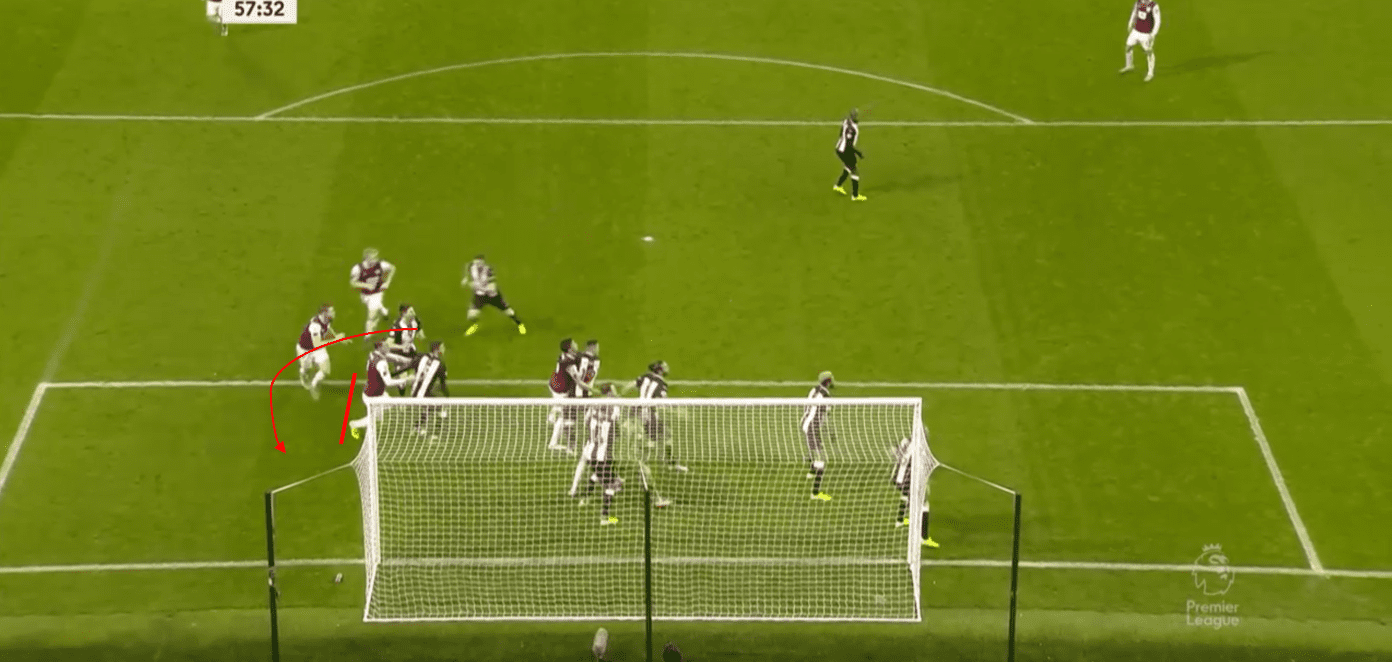

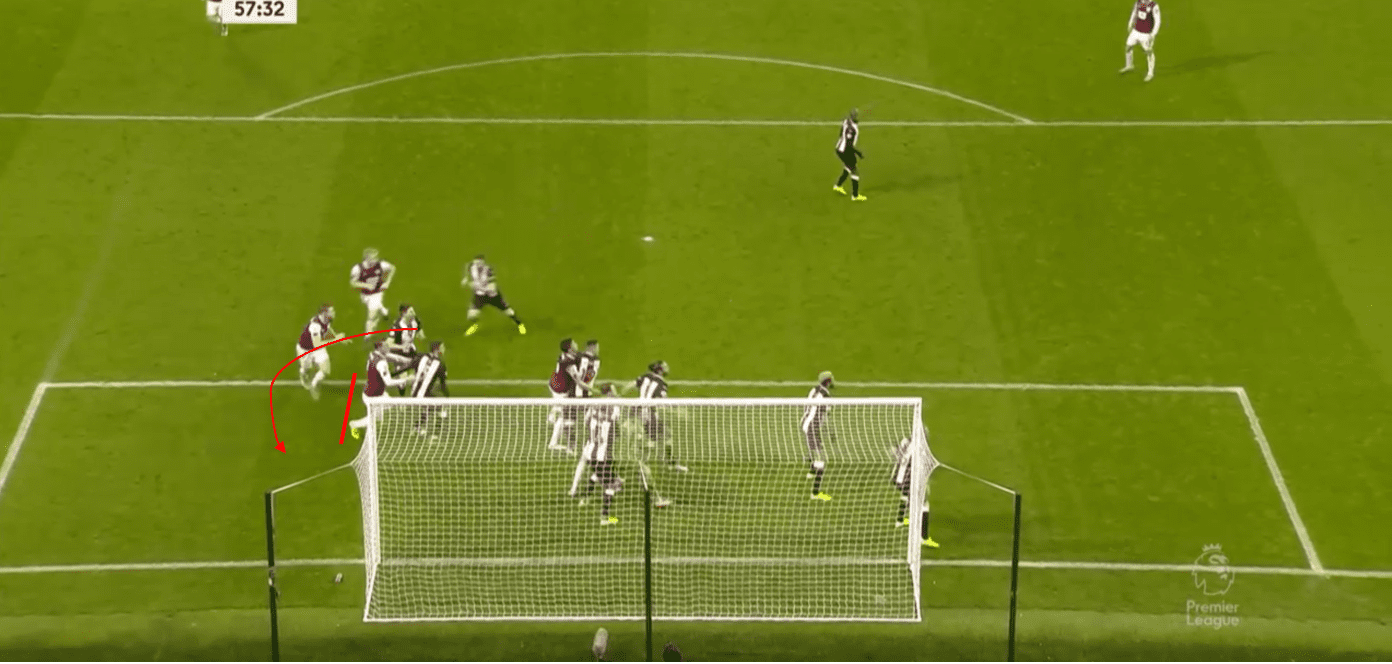

We can see in this example here Chris Wood makes a quick movement towards the back post, with his marker watching the ball. A Burnley player is already at the back post, positioned on the far side of their marker, meaning when the ball is delivered, Newcastle can’t adjust and Chris Wood can score a free header at the back post. This original back post player can also act as a blocker for Wood’s marker if needed.

Another prominent trend in Burnley’s success from back post corners is their preparation for the second contact. Back post corners can often be delivered into areas too far from goal to score from directly, and so it is important players are positioned well to challenge for the second ball. Burnley do this well and structure themselves to increase the probability of winning the second ball.

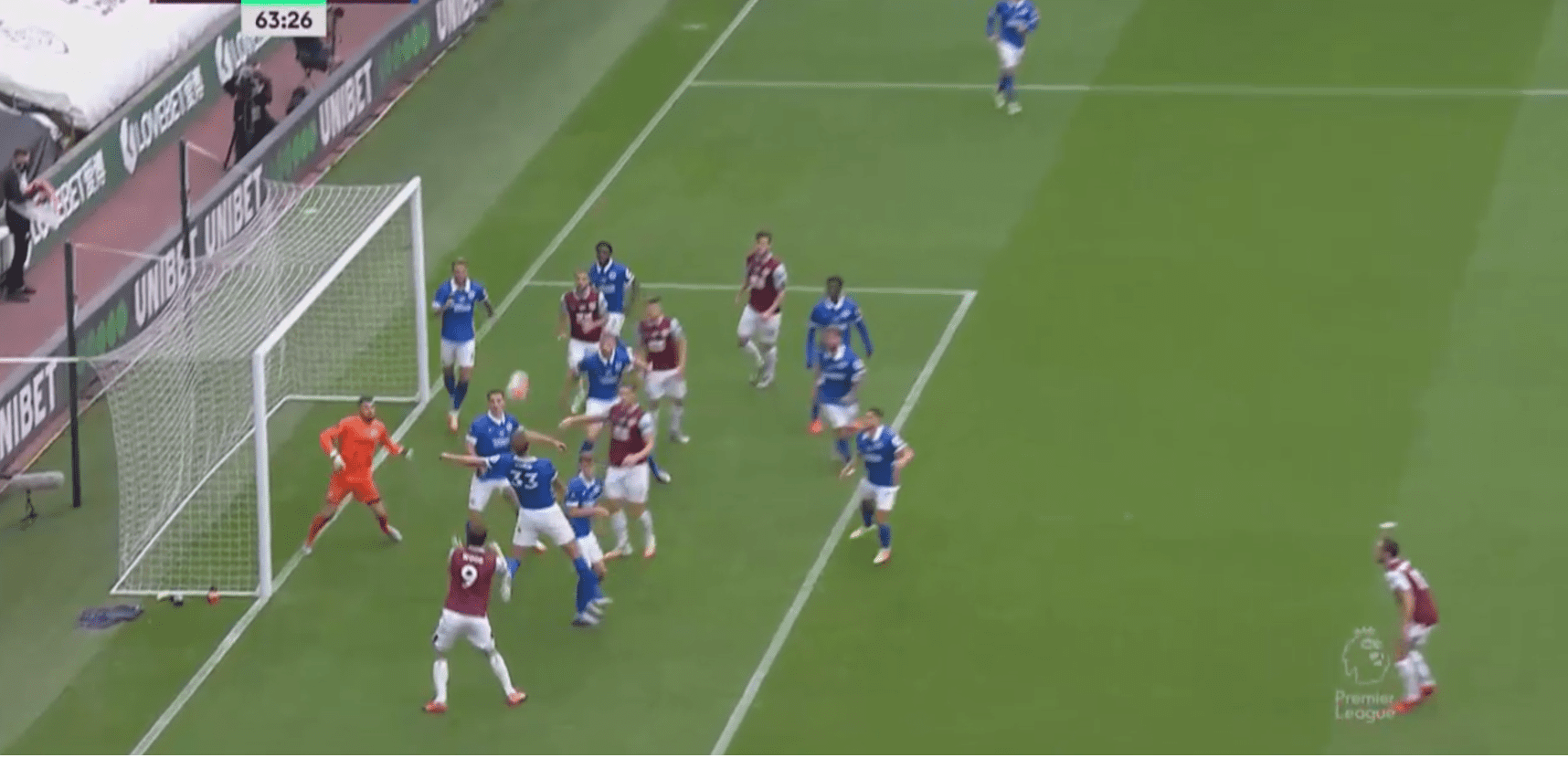

We can see an example of this below where Burnley stagger themselves well around the back post header, with four players at different heights around the six-yard box ready to win the header. By pinning the goalkeeper and positioning themselves high, Burnley allow themselves to get closer to the goal, and they also then have players in positions to head the ball. Staggering players at different heights increases the overall area they cover, and so it is more likely that Burnley win the second ball.

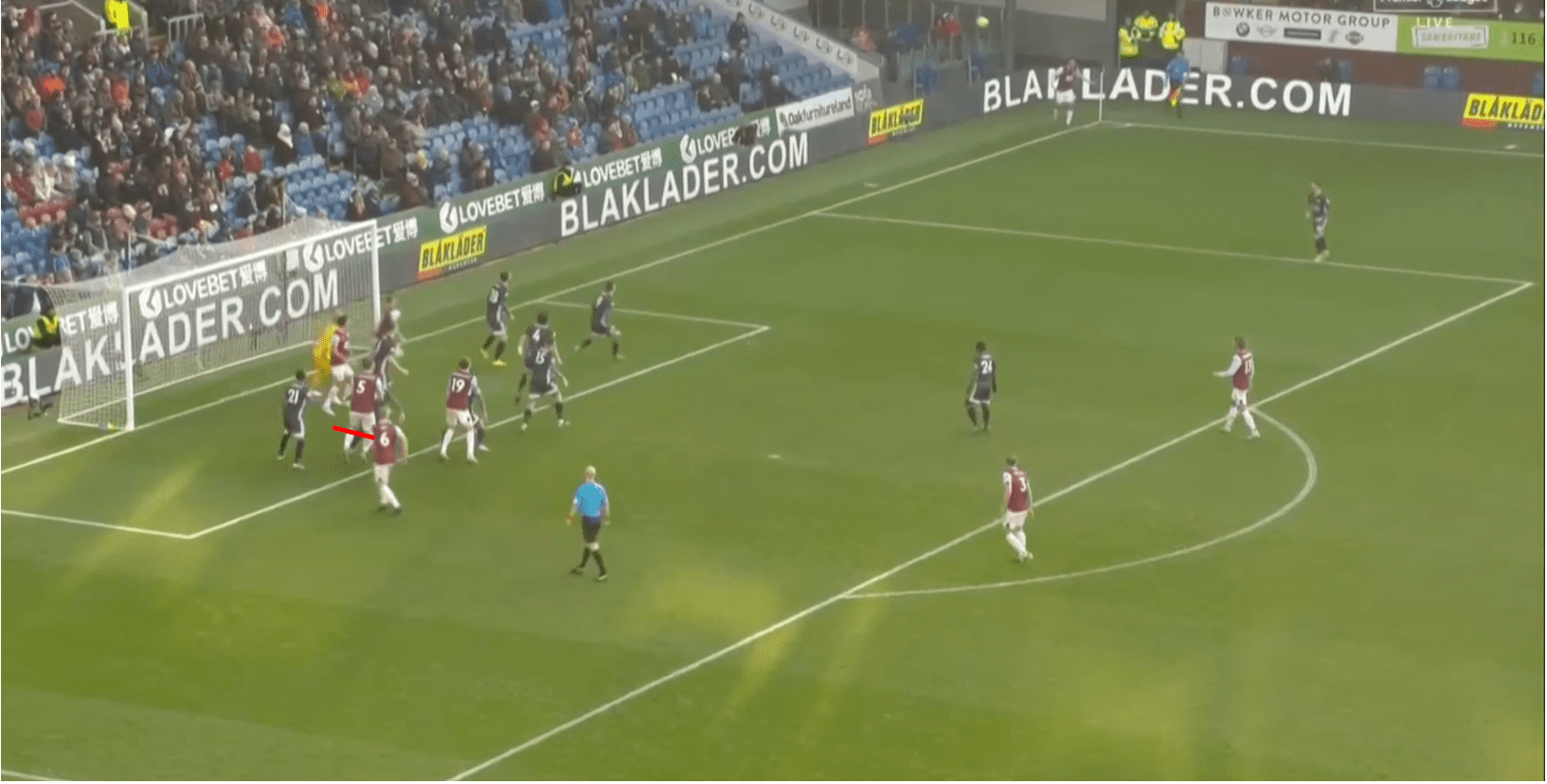

We can see in this example below following a simple dismarking movement by Chris Wood, he is able to get open at the back post again. Burnley then have four players again in the six-yard box in different areas, and so the likelihood of winning the second ball or a rebound from the goalkeeper is higher.

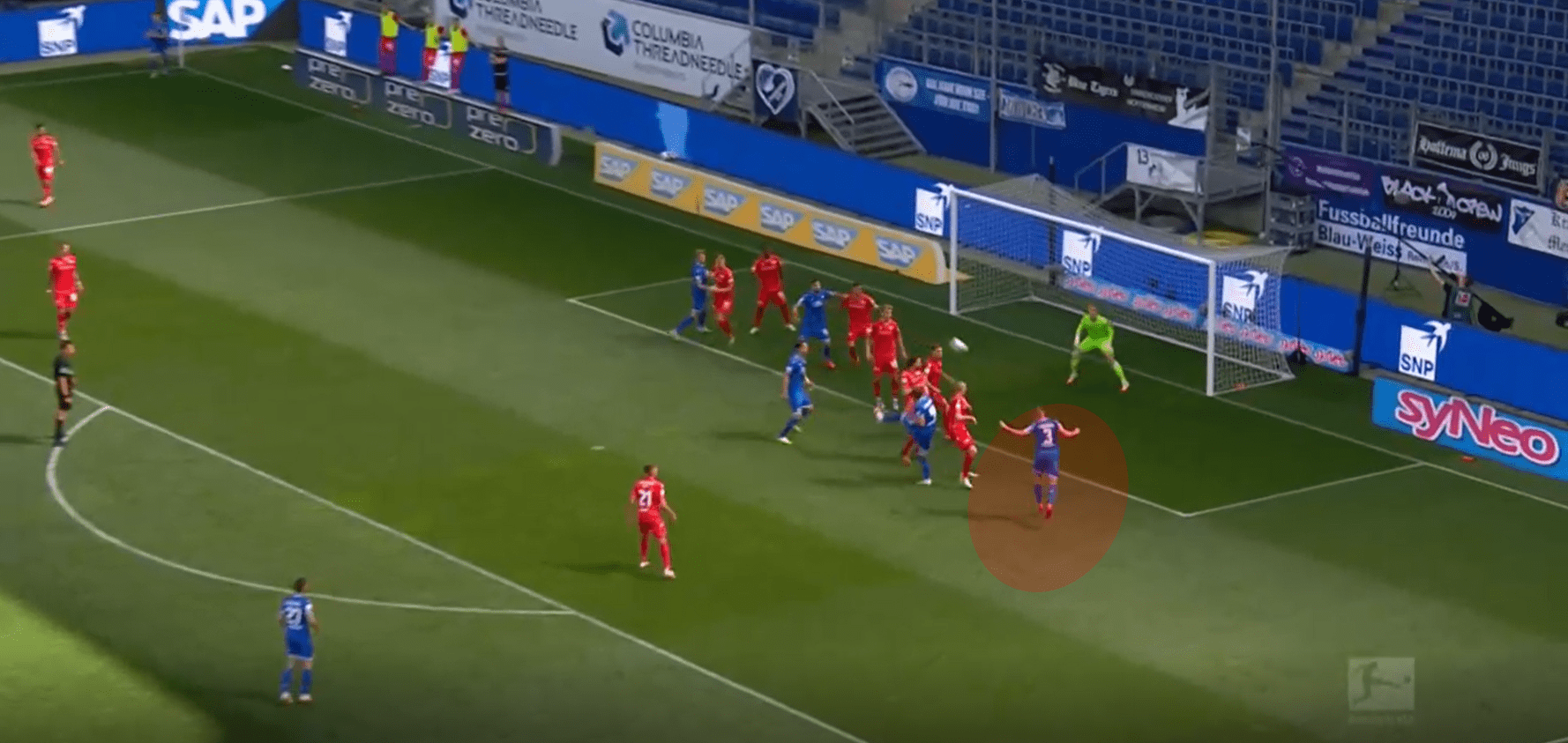

This example below sums up all of the nice trends in Burnley’s set pieces. We see Burnley space well and commit one player to the back post. This player (Tarkowksi) uses his hands well to create separation from his marker, and Ashley Barnes positions himself on the goalkeeper to block him from pushing out to claim the ball. This use of his hands by Tarkowksi is something I will mention throughout the series. The initial spacing by Burnley means the back post is fairly vacant other than the one player, and this is deliberate in order to help win the second ball.

Once the ball is delivered towards the back post, Ashley Barnes moves off the goalkeeper and backwards into that initial vacant space in front of the goalkeeper. Barnes can then simply receive the knockdown and score completely unmarked from about four yards out. Burnley’s initial spacing allows for Barnes’ movement, and the individual movements of Tarkwoski and Barnes make the goal.

Brighton

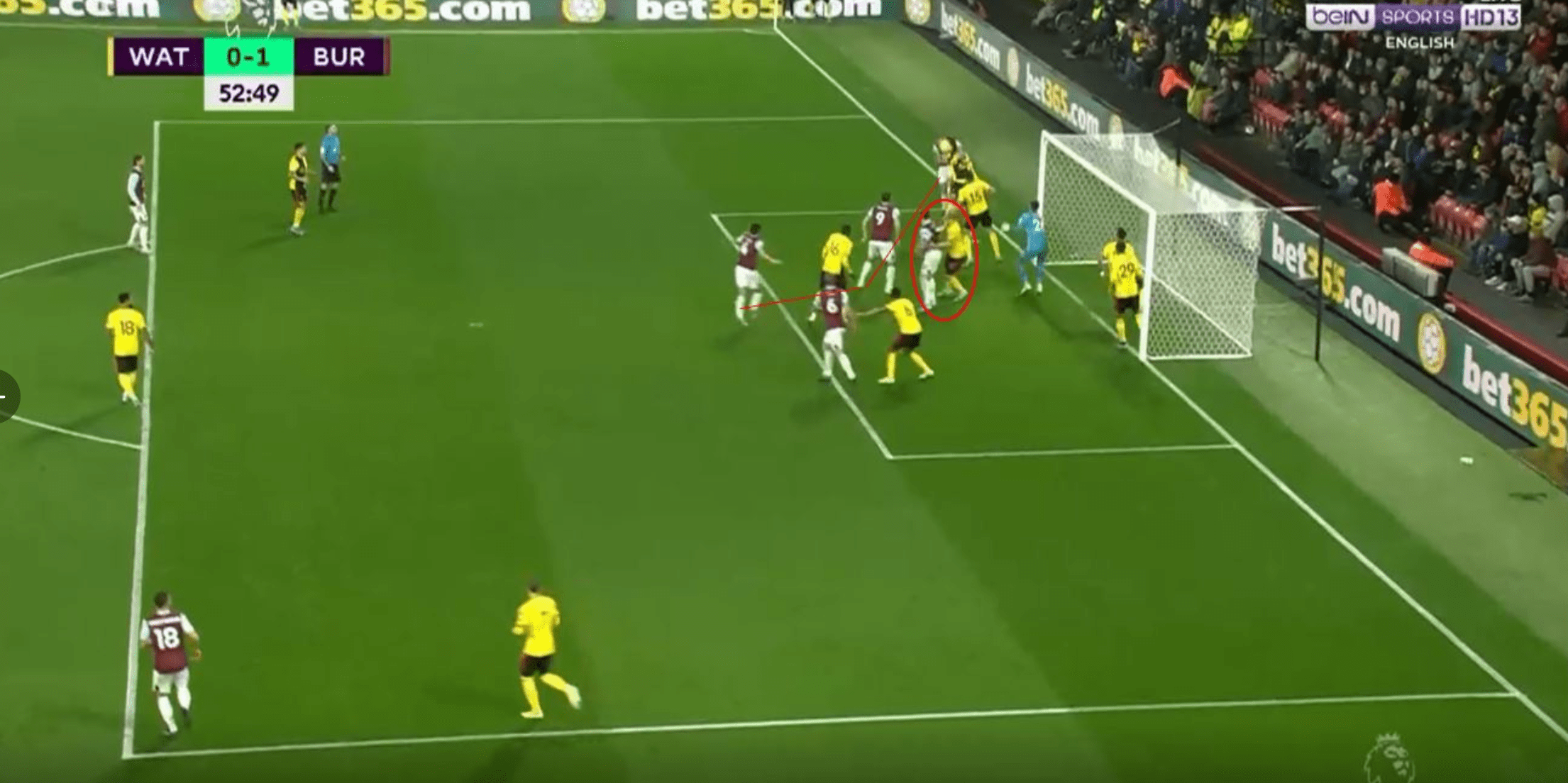

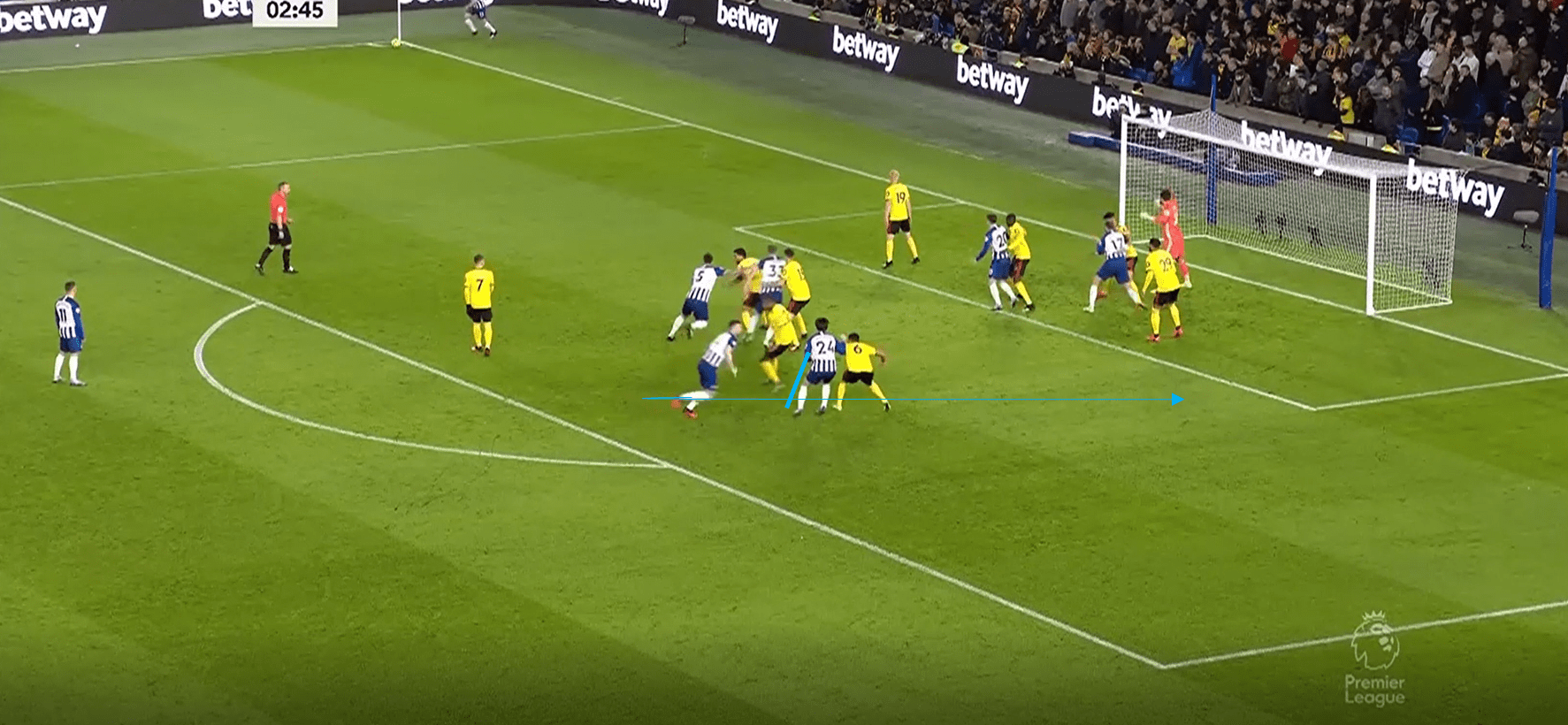

The main trend in Brighton’s back post corners is their common movement of target players running around blockers or traffic in order to receive at the back post. We can see an example of this below against Watford, where one player starts deeper and aims to make a run at the back post. Another player slightly higher also is in the same path towards the far post, but this player instead stays still and blocks the movement of the target player’s marker, which allows for his teammate to run around and into the space unmarked.

We can see a good example of this again against Chelsea, with the deepest player of a train making the movement towards the back post. Chelsea defend against the train poorly, going man for man and easily allowing the second Brighton player in the train (number 33) to block him. A block is placed on the nearest back post player also, and so the Brighton target player has a free run at the back post. The delivery however is poor and so it comes to nothing.

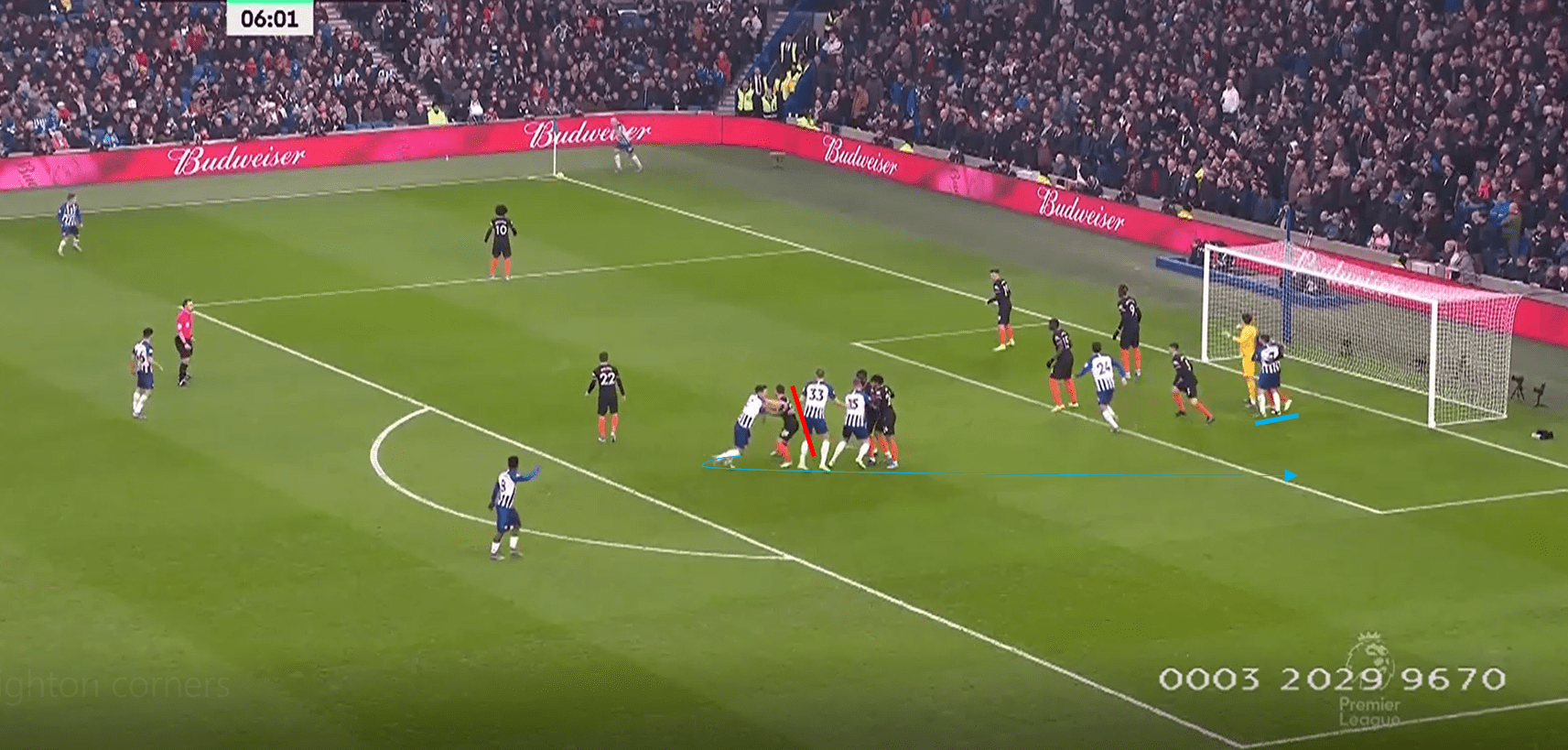

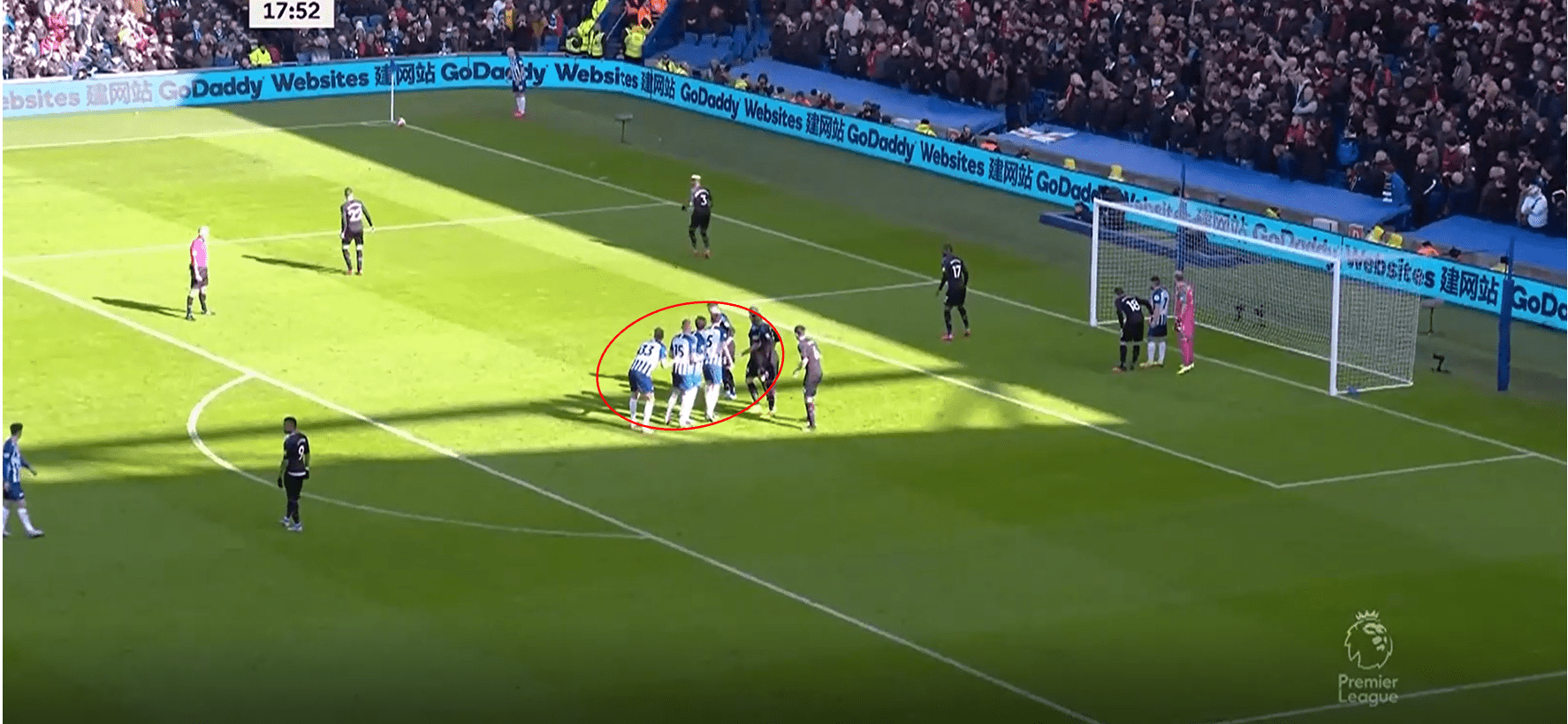

Brighton seem to rely more on intricate movements than the likes of Burnley (which isn’t a good or bad thing), and we can see an example of such a movement below. Brighton here use a scissor movement, where two players swap directions by crossing paths in order to confuse their markers. The deepest player again moves towards the back post while a higher player moves towards the centre, and this movement helps to create traffic which allows Dunk to lose his marker.

Because of this scissor movement, the Everton players end up following the same man, and so Dunk gets free at the back post. Everton have a back post zonal marker, but Dunk can gain dynamic superiority against a static zonal marker to get a header away valued at 0.25xG.

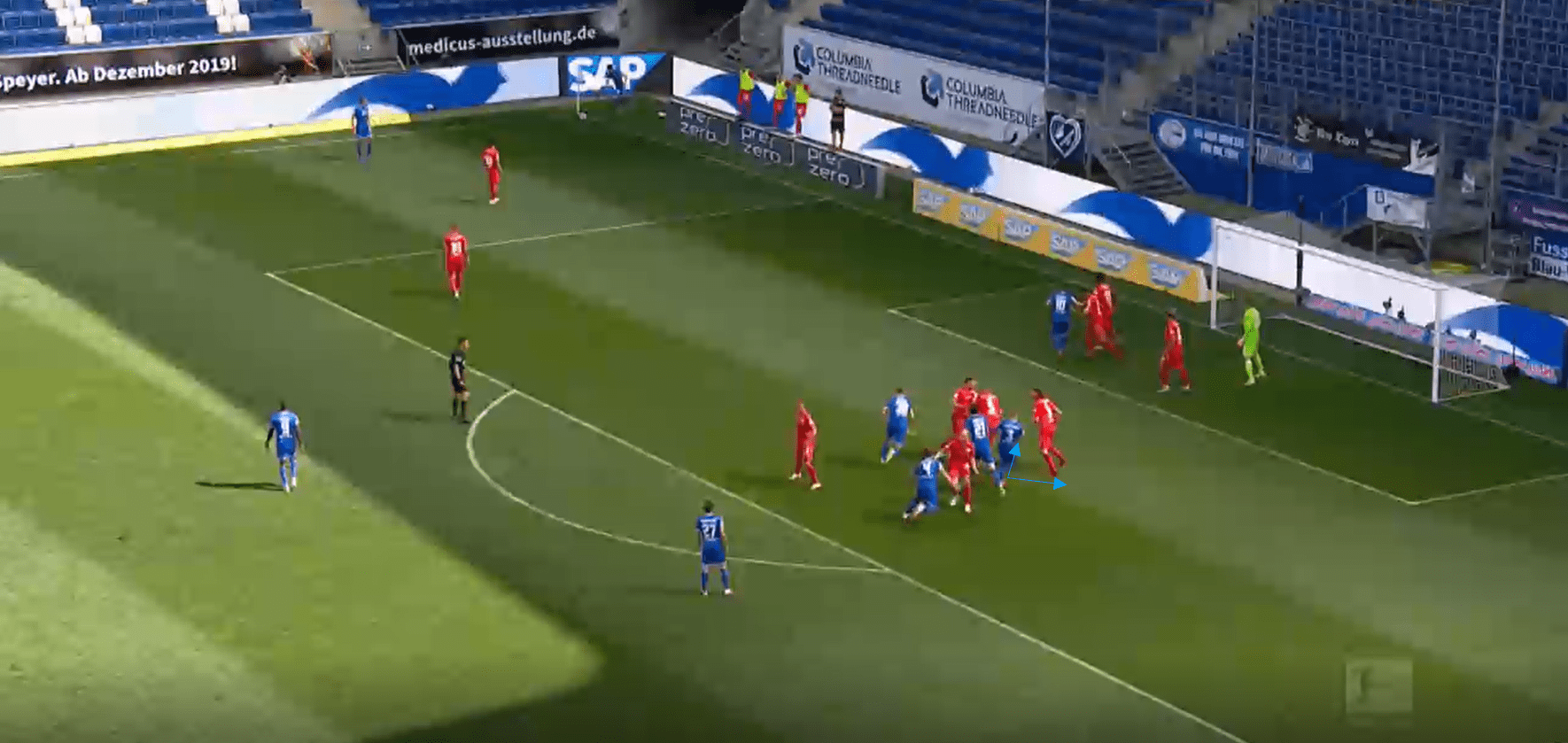

Something which Brighton also commonly use is trains in order to dismark opponents and create separation. We can see an example of this below where Brighton line up players one behind the other before these players then move off in different directions. This makes them very difficult to mark man to man due to the compactness of the train, and so teams will often fall back into this shape seen below, with their aim just to cover and limit as many players as possible.

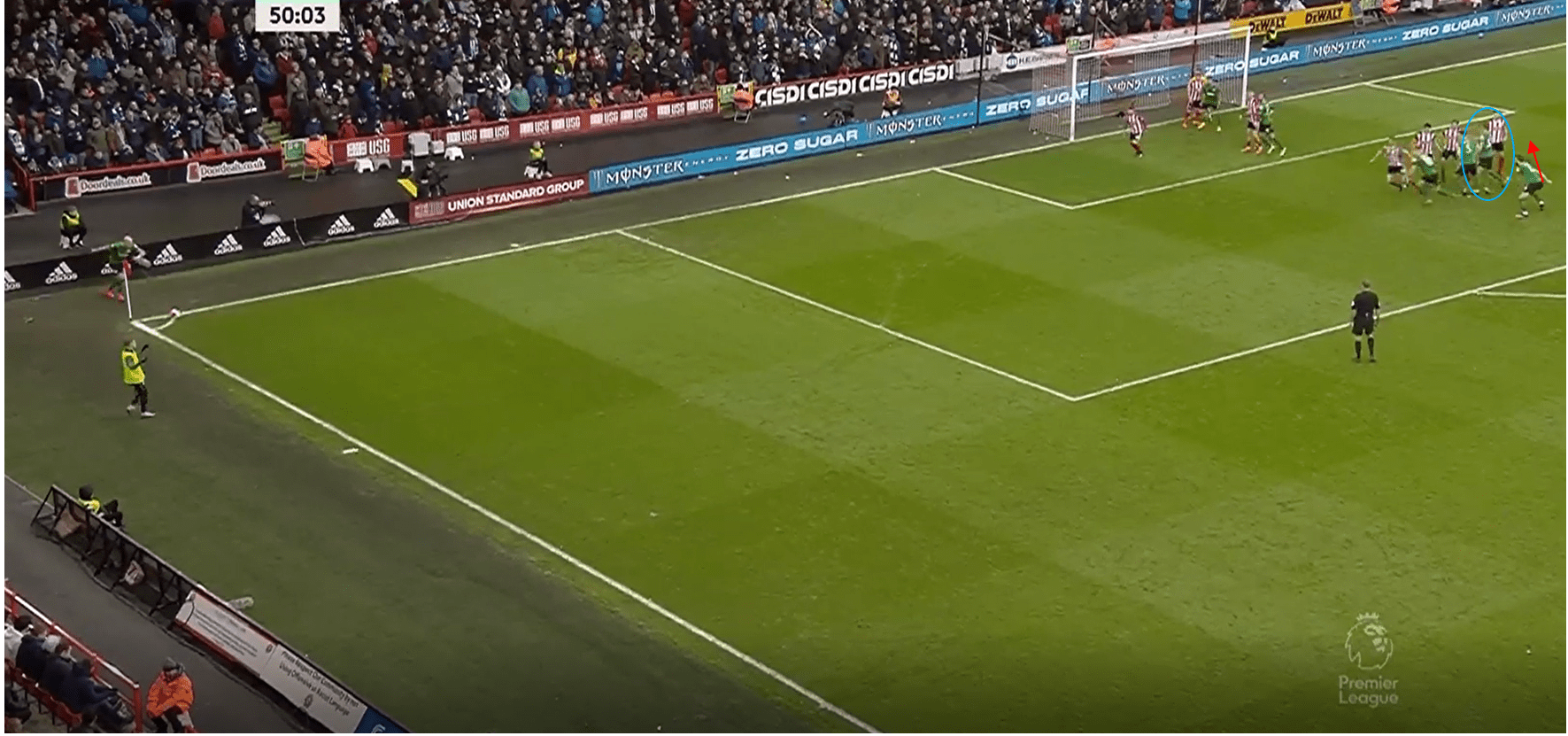

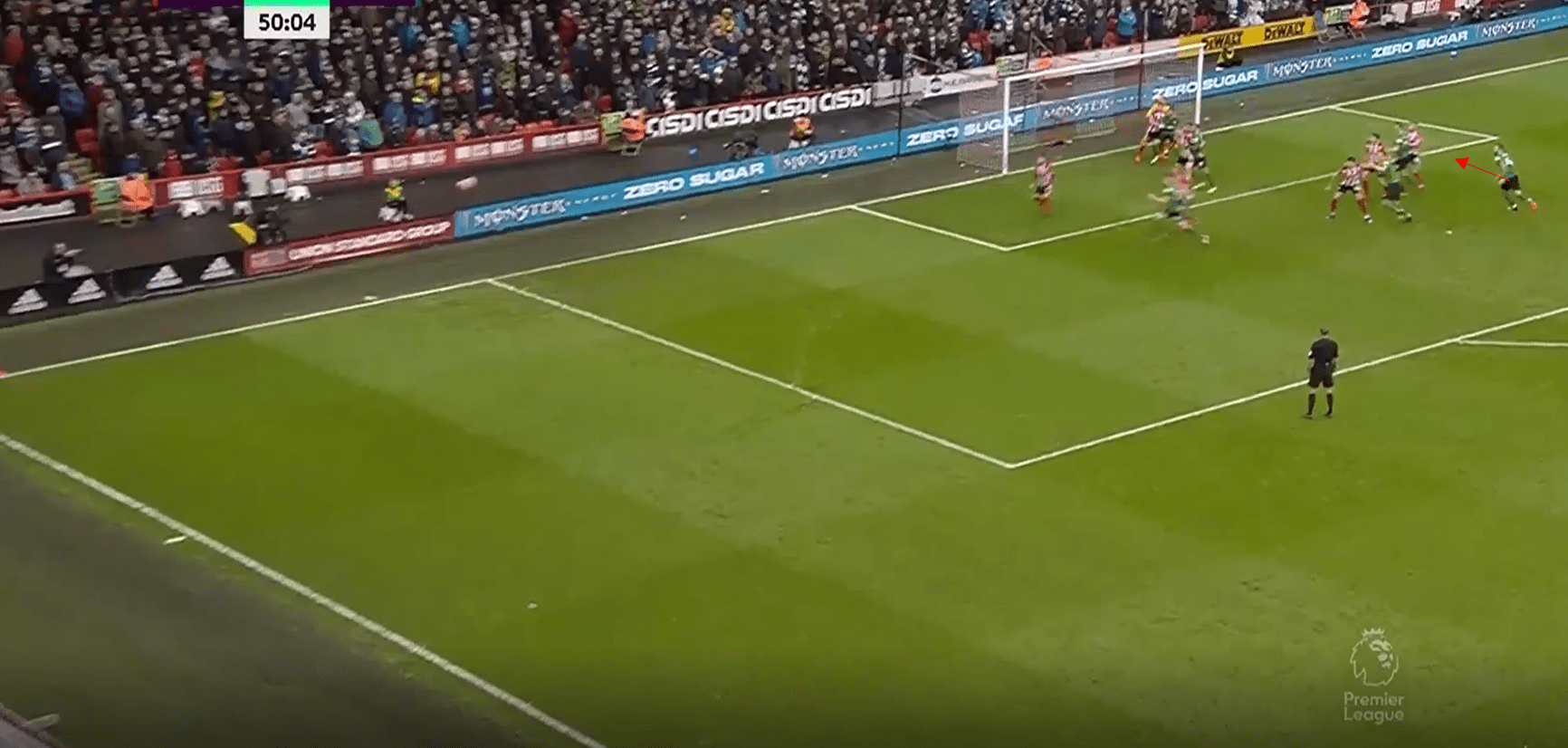

We can see an example of a good movement by Brighton from a train here, where they stagger their runners again, with one player remaining deeper while the rest run forwards out of the train. The deeper player holds his run and allows his teammates to occupy the defenders, before he then moves towards the back post.

We can see the opposition back post player gets occupied by a Brighton attacker, and so target player Shane Duffy has a free run at goal and can attack the back post delivery well. The staggering and timing of the run is what allows him to get free here, but Sheffield United’s back post marker does just enough to put off Duffy at the back post, preventing him from getting a clean header.

Brighton though have a decent second ball structure, and so Lewis Dunk, who was one of the central players, drops deeper to increase the chances of winning the second ball. He is able to get a shot away from the second ball, which is worth 0.39 xG.

Hoffenheim

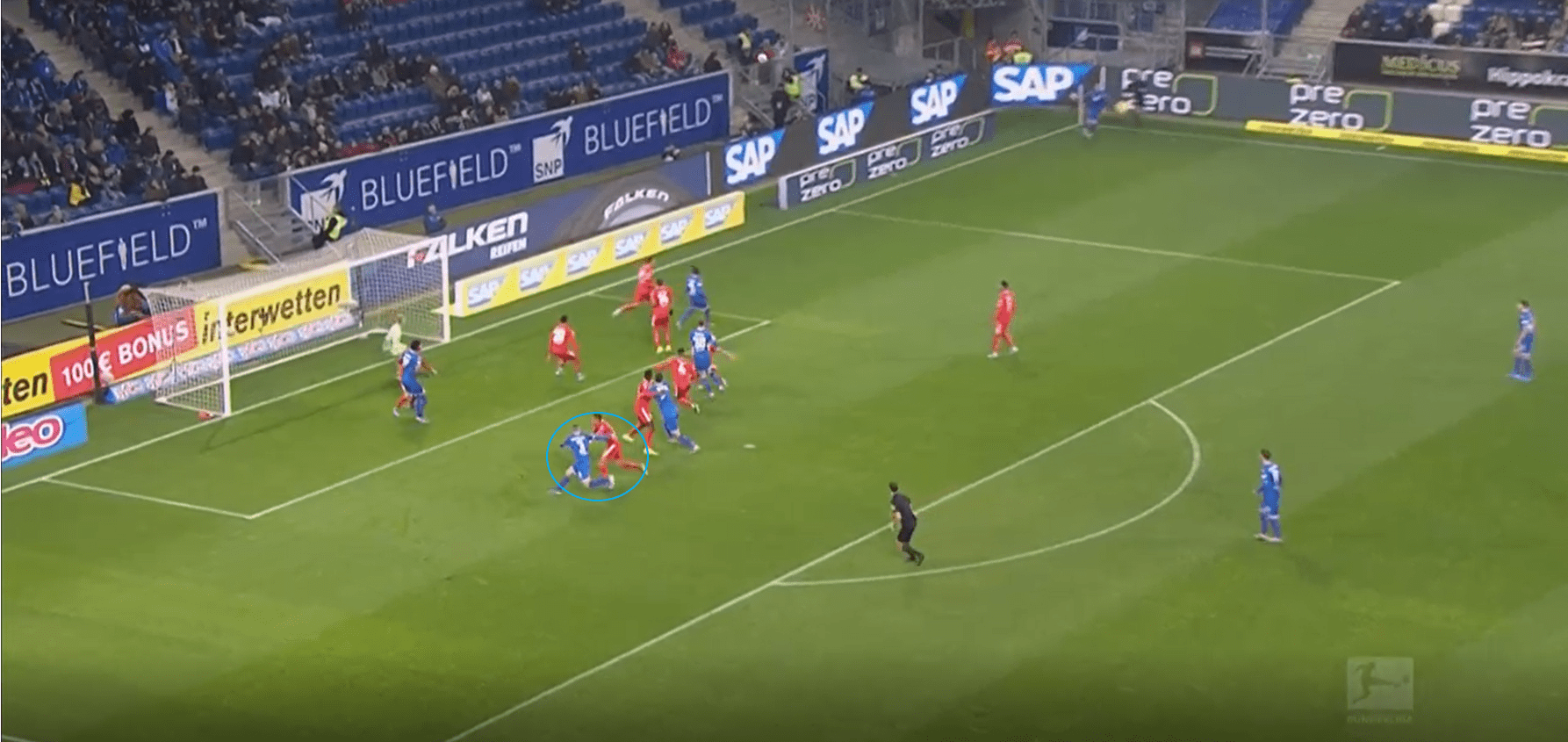

Hoffenheim ranked second in our chart in terms of xG per five corners at the back post, and the main trend in their play is their use of excellent individual movement combined with the natural advantage of the back post. We can see a good example of this here with a player making an initial simple movement towards the back post while marked. If we look at the body positioning of the defender, he has neither the defender nor the flight of the ball in his eyeline, and instead just looks to run to the back post urgently in order to stay with his marker.

The Hoffenheim attacker (Pavel Kadeřábek) recognises this, and so stops his run and changes direction. The Mainz defender isn’t watching the flight of the ball or the attacker very effectively, and because of the urgency of his run, he cannot slow down and react to the attacker’s change in direction. As a result, we see the separation created between the pair, and Hoffenheim get a free header on goal.

Kadeřábek generally seems to be very good from set-pieces, with his individual movement often allowing him to gain a free header on goal. In this example, we see he starts as the player closest to the back post, but he makes his run inside towards the centre initially. His marker takes a quick look to check the run, before then looking back at the ball.

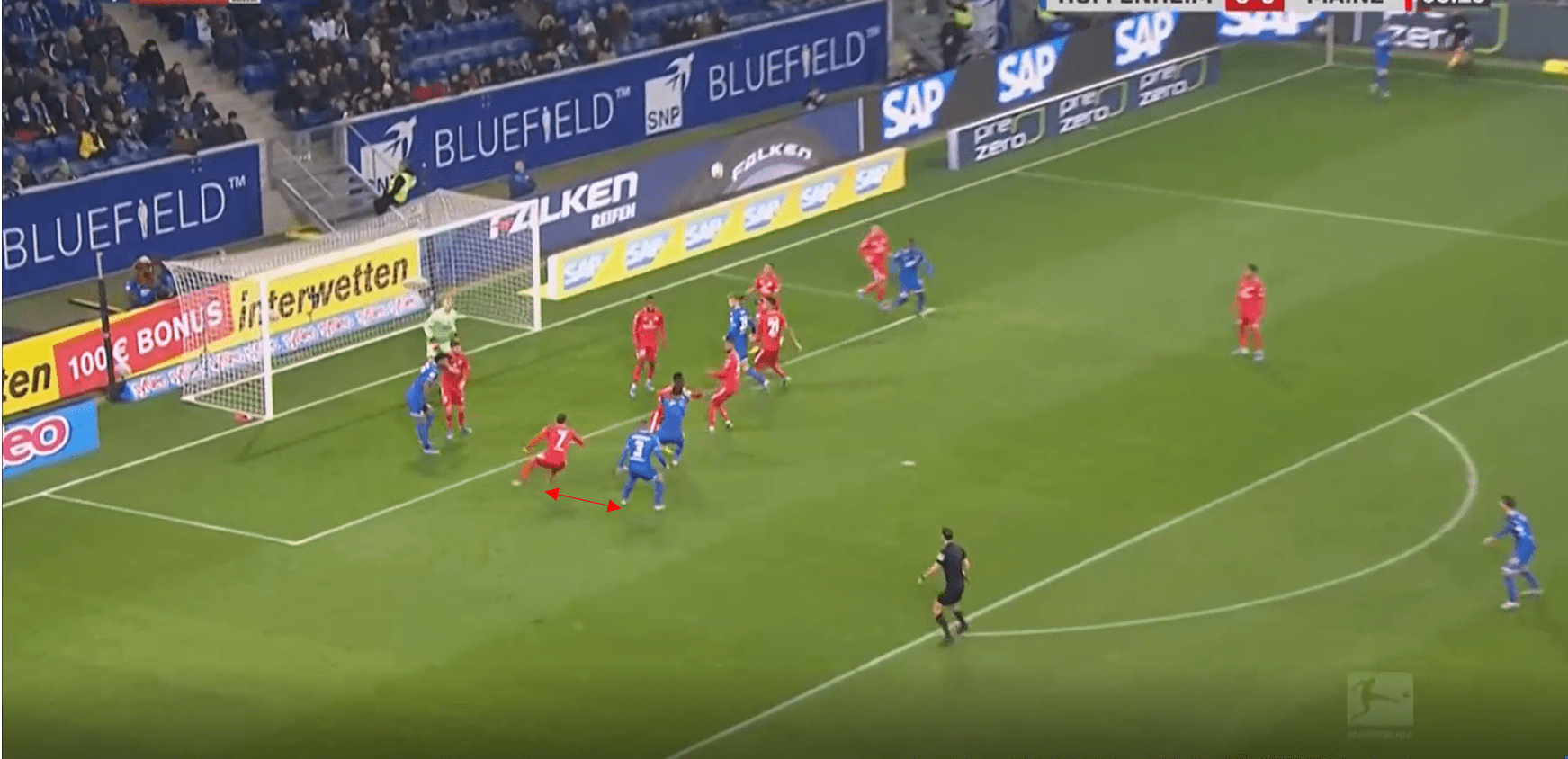

Once the ball is about to be delivered, Kadeřábek changes direction and runs towards the back post again. The opposition defender looks at the ball as it is about to be delivered, and after his first scan, he just assumes Kadeřábek is still making the same run. The defender therefore moves towards the centre/near post, while Kadeřábek moves to the back post.

As a result, Hoffenheim get a completely free header at the back post, with the original marker of Kadeřábek a good few yards from him. An incredibly simple movement executed well against man markers can have a massive effect.

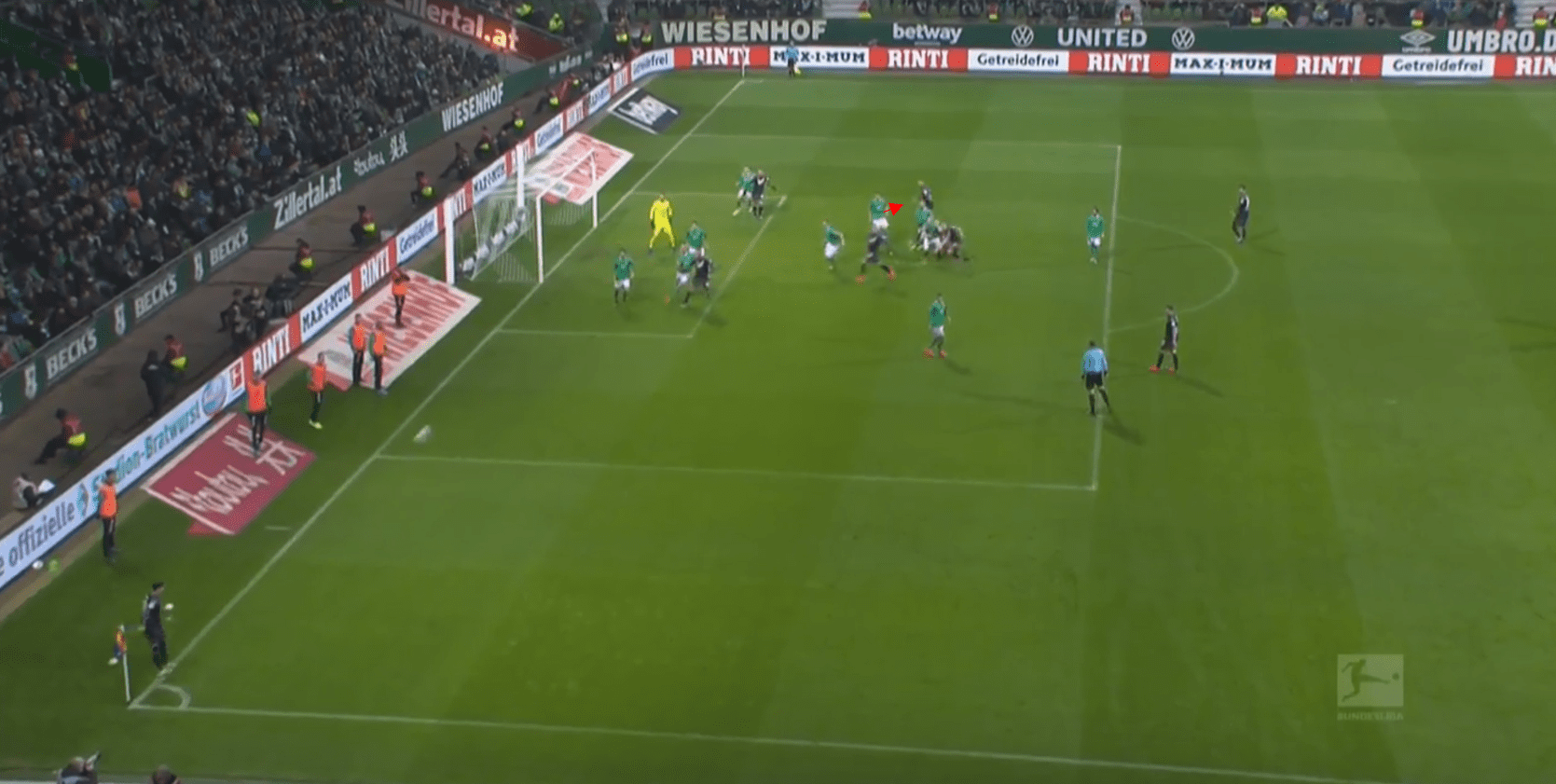

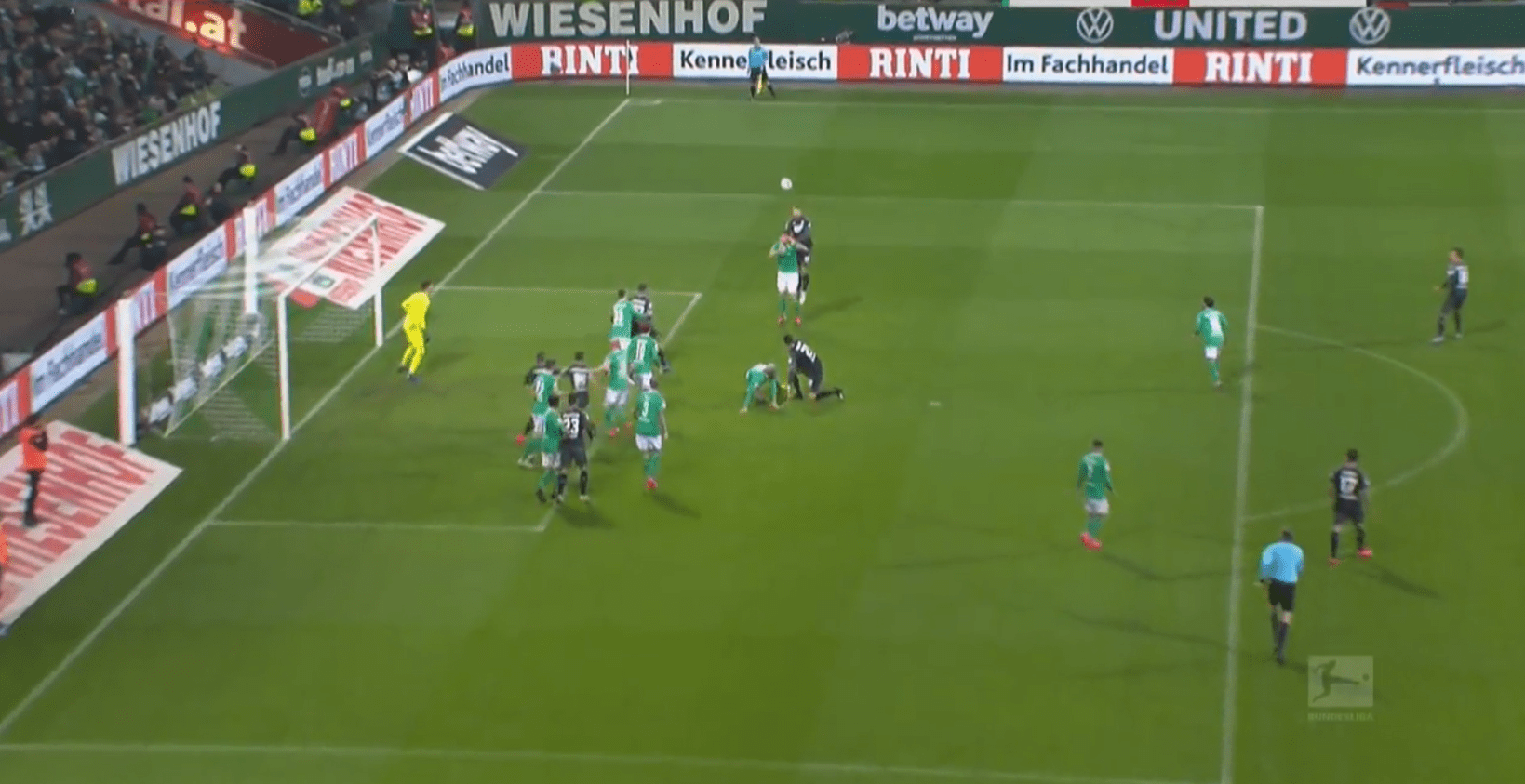

Hoffenheim’s height and physical attributes in the box allow them to take advantage of the natural advantage of the back post also. In this example, Hoffenheim start from deep and stagger their runners in a train, with one player moving towards the back post. Separation is created by that original train, but Werder Bremen do a decent job of staying with their men.

The back post players marker is able to get fairly close, but he has to run backwards to get close to the attacker. As a result, we see that back post advantage again where the attacker can jump much higher and win the header. Hoffenheim’s preparation around the second ball is good also, and so the ball is nodded down to the closest player, who forces an own goal through an overhead kick.

There are multiple examples of Hoffenheim’s changes of direction and other such movements creating space and separation for headers, however in the context of this kind of analysis, it can be difficult to show these kinds of movements using still images.

Crystal Palace

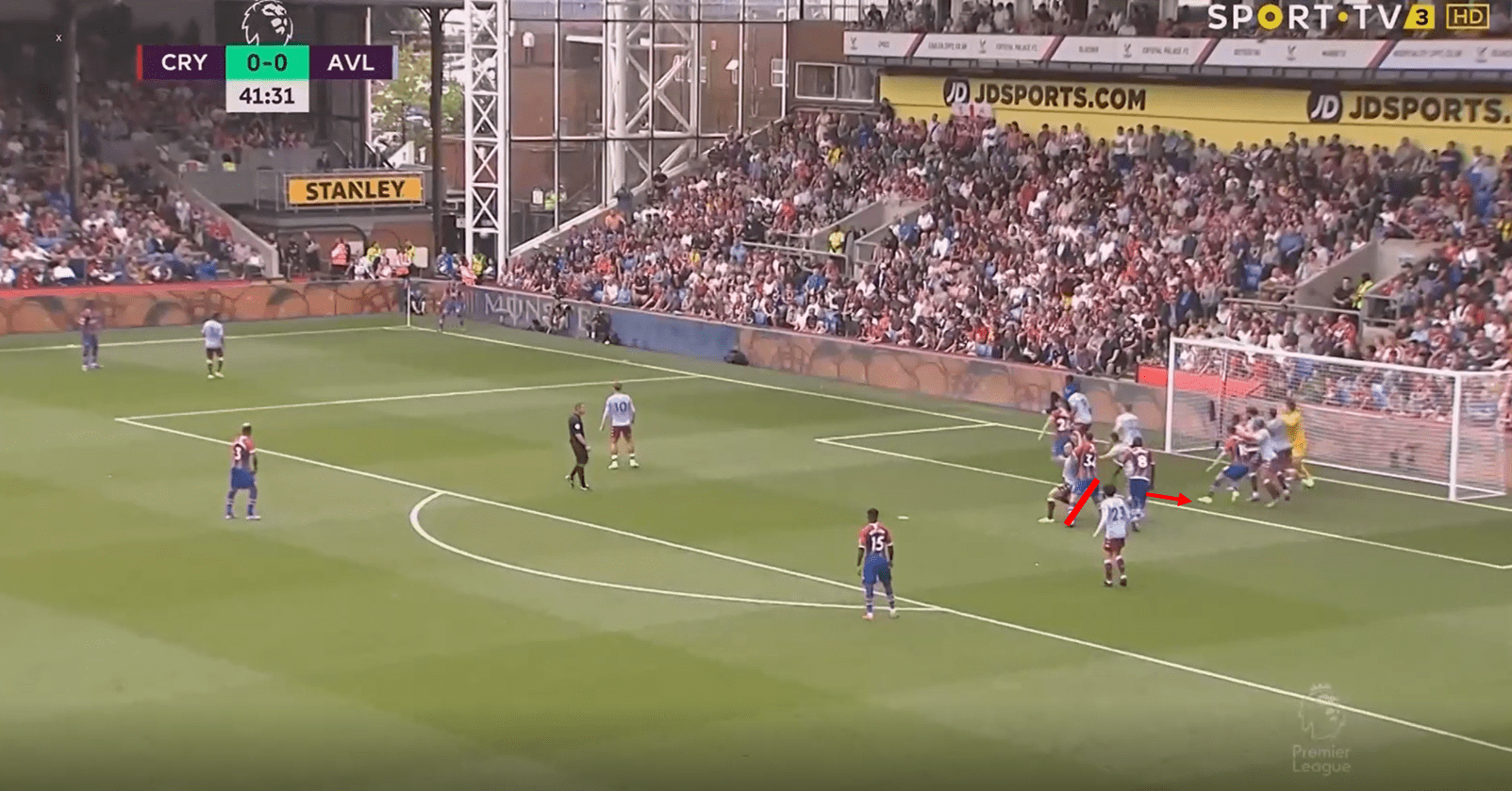

Crystal Palace combine lots of the ideas already mentioned, with good examples of blockers and changes in direction seen. We can see a good example of a block below, with the furthest player from the back post running against the traffic. The target player Cahill starts at the near post, while two other Palace players stay in a more central position. Cahill starts slightly higher than these two players, before spinning and running towards the back post. This means that Cahill has to run towards his teammates, but because he spins, he starts deeper than his marker. As a result, Cahill can run around the traffic and towards the back post, while the defender cannot. Defenders will often look to take a shortcut through the traffic as a result of the difficulty tracking markers who arc their run, but getting through the traffic should be difficult if the offensive team does their job.

We can see that the traffic here does its job, as the defender gets stuck trying to run through the Crystal Palace attackers. Gary Cahill therefore is able to get free at the back post, but the delivery is slightly off and so Palace have to make do with a volley from a poor angle.

We can see in this example here Crystal Palace work in a pair, with one player moving towards the back post while a far player can act as a blocker. Kouyaté is able to get a free run at goal as a result of this block by Martin Kelly, and Kelly’s marker cannot adjust to mark Kouyaté who is now free.

We can see Crystal Palace attempt a similar move here, with a near post player spinning and looking to run around the traffic towards the back post. Here though, Palace don’t recognise this to set up a block, with Scott Dann (number six) having the best opportunity to set up a block. The run by the target player also starts too deep, as when he creates separation, the defender isn’t behind that group of players that act as traffic. As a result, the defender doesn’t have to run through traffic and can just follow the run easily.

We can see a slightly better example here, but again the target player doesn’t start high enough, and so the traffic can be avoided failry well by the defender. Palace also don’t actively place a block on this player depite Kouyaté actually making contact with the defender. The arced run does create some separation, but not as much as it could. This kind of run naturally makes you difficult to follow, and the defender has to fully turn his back on the ball in order to track the run.

Conclusion

This article has sought to identify some of the best teams in Europe at attacking the back post from corners. The teams analysed were chosen based on the number of shots relative to number of deliveries, as well as xG generated. There are of course specific routines, tactics, and movements which can be practiced to utilise the back post, but this analysis looks to identify principles or common ideas amongst the ‘best’ teams who use the zone consistently. The back post is an area which is generally associated with physicality, and while height and other physical attributes are important from set-pieces, movement and coordination is arguably more important. To conclude, from this article we can identify the general trends that successful teams display at the back post are:

- Consistent changes in direction

- Feinting movements to create separation

- Far side blocking

- Creation of traffic towards the back post

- Running in the direction of traffic

Next in the series we will look at the penalty area before moving onto the goalkeeper zone and short corners. Between that though, I might get distracted and decide to give Union Berlin’s offensive set-pieces an article of their own.

Comments