Brest boss Olivier Dall’Oglio built his positive reputation during his six-and-a-half-years at Dijon, which saw him help the club to re-establish themselves in France’s top-flight. He’s now been managing Brest since 2019/20, guiding the then-newly-promoted side to a 14th-place finish on their first season back in the top-flight since 2012/13.

While Les Pirates aren’t completely safe from being forced back to Ligue 2, at the time of writing, they remain clear of the drop zone in a season where they have been receiving plenty of credit for their entertaining playing style. They are currently the seventh-highest scoring team in Ligue 1 (43), while they’ve conceded the joint second highest number of goals (54) in Ligue 1. Brest games have seen an average of 3.13 goals per game this season. Only games featuring Monaco and Montpellier have seen more goals than Brest games.

Lots of credit for Brest’s entertainment value has gone to Dall’Oglio. The 56-year-old has been touted as a potential successor to Rudi Garcia at title-challenging Olympique Lyonnais in recent months, which would undoubtedly be a step up and these links are a testament to his past work with Dijon and performance with Brest.

In this tactical analysis, we’ll analyse key elements of Dall’Oglio’s tactical philosophy via analysis of his Brest side. We’ll look at what Brest’s tactics tell us about a Dall’Oglio team while analysing some standout strengths and weaknesses of the highly-rated coach’s side.

Dall’Oglio’s Brest in defence

Les Pirates don’t tend to recover the ball high up the pitch much. With a PPDA of 15.52, they’re the sixth-least aggressive pressing team in the league. However, they do engage in plenty of defensive duels, with 70.21 to their name, per 90, for the 2020/21 campaign – more than all but two other teams in France’s top-flight.

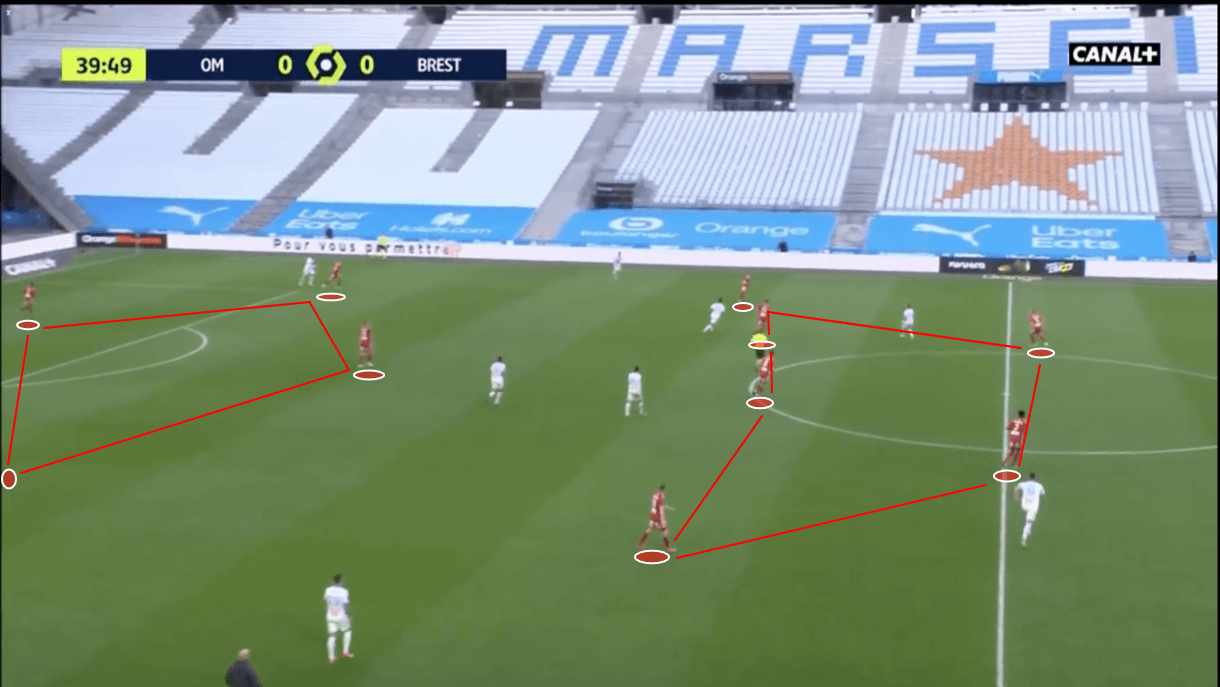

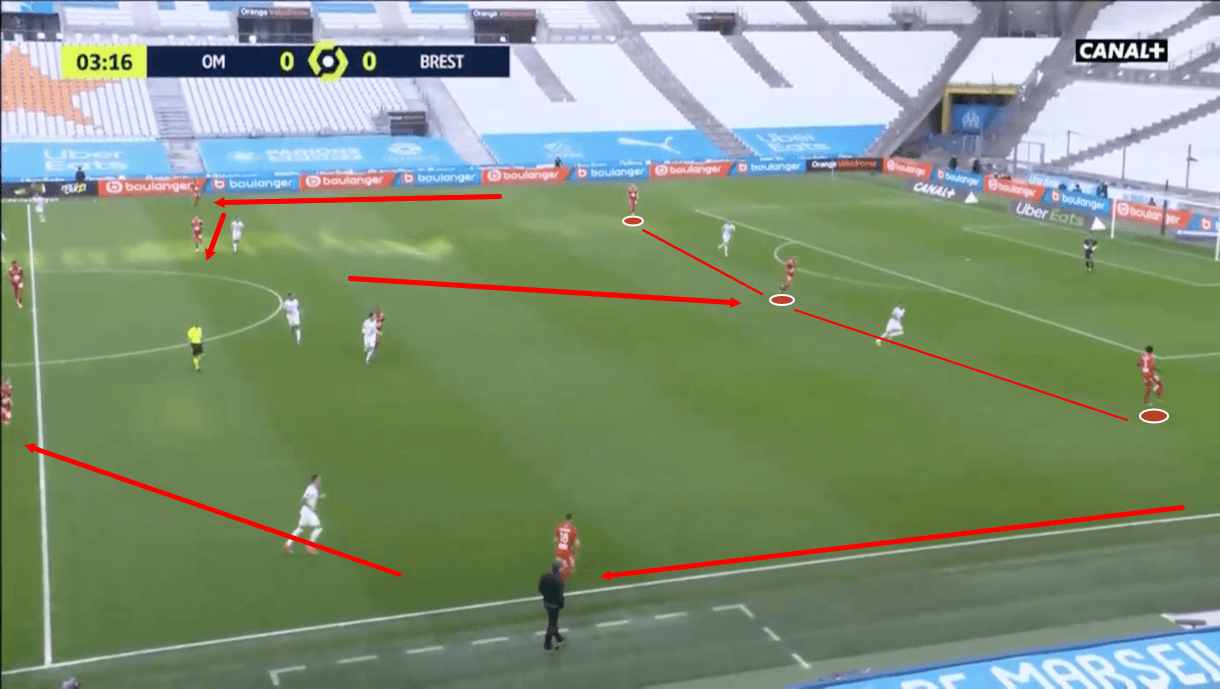

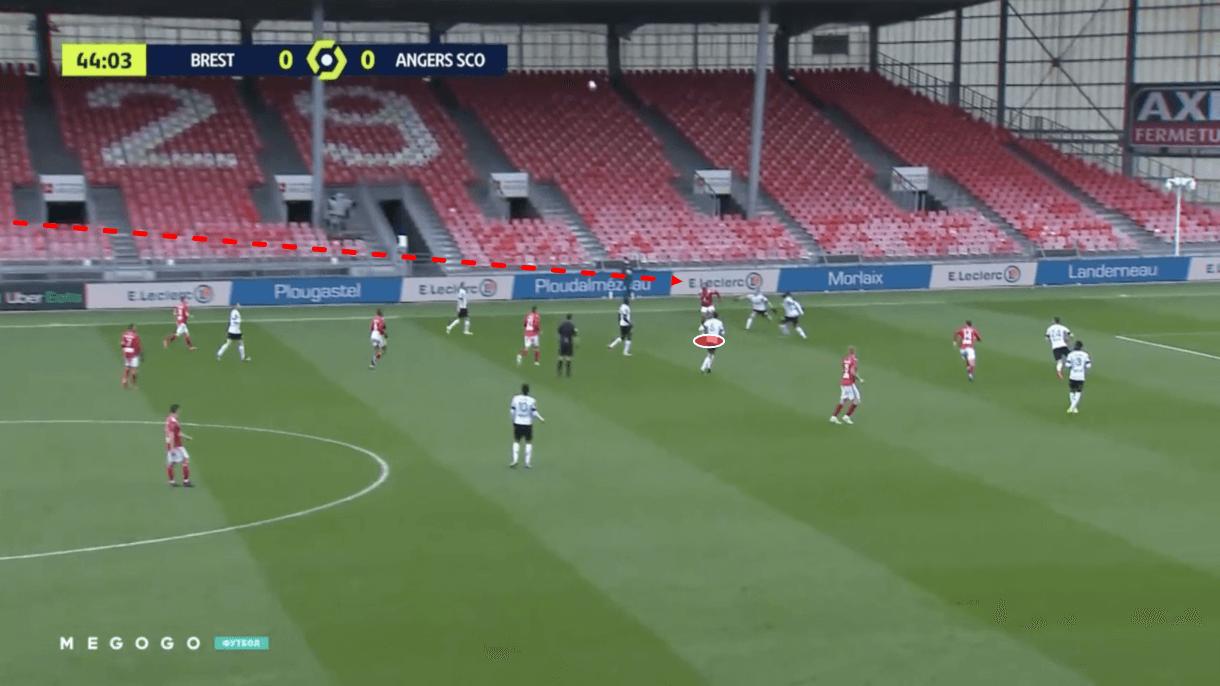

Dall’Oglio’s team usually defends in a 4-2-3-1 higher up the pitch, as was the case in figure 1. Here, Brest’s opponents, Olympique de Marseille, had just been in possession deep inside their own half, which attracted pressure from Brest’s centre-forward, supported by the wingers. The ‘number 10’ remained deeper, offering more support to the holding midfielders.

Brest’s centre-backs stay roughly where you’d expect them to be during this stage of play but the full-backs tend to get in line with the holding midfielders, closing the gap between them and the pressing wingers and resulting in the shape looking more like a 2-4-3-1. This image shows a typical example of Brest’s defensive shape while the opposition are in possession deep.

In figure 2 we see how the box formed by the full-back, the holding midfielder, the winger and the ‘10’ essentially creates an area where Brest will attempt to win the ball back in the opposition’s half.

Just before this image, Marseille’s goalkeeper had the ball and attracted pressure from Brest’s striker. The ‘keeper opted to pass the ball long, looking for the Marseille man closest to Brest’s left-sided holding midfielder. This resulted in the ball moving into this box formed by the four Brest players. The box then closes, with the full-back and holding midfielder moving up and the winger and ‘10’ dropping. The nearest man, the holding midfielder, cuts off the passing lane, makes the interception and sets Brest off on a counter.

As mentioned previously, this team isn’t renowned for winning the ball back high but this is how they shape up defensively in this stage of play and when the ball is played into this area, they do tend to spring into action. As a result of this, the holding midfielders and full-backs tend to engage in the majority of defensive duels and make the majority of interceptions for Dall’Oglio’s side.

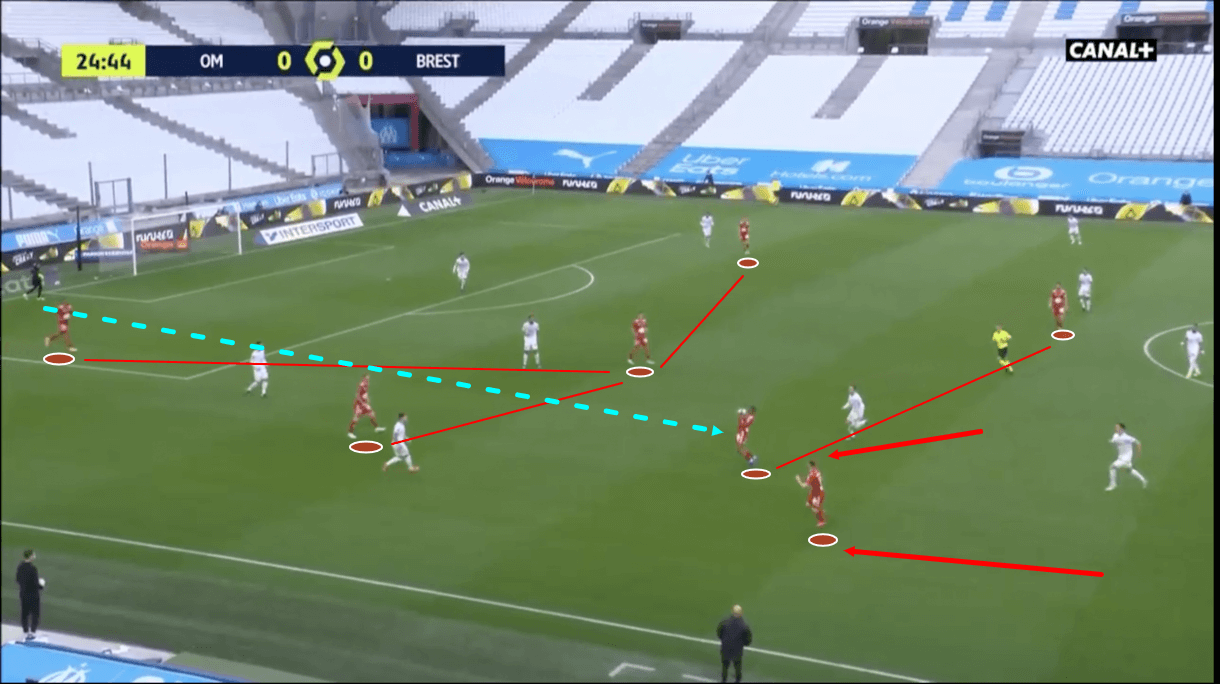

A lot of the time, you’ll see Dall’Oglio’s side shaping up more similar to figure 3 – an organised, compact 4-4-1-1 mid-block, with the opposition in possession in the middle third of the pitch.

The centre-forward tends to apply some pressure when the ball is in front of him but not when it’s been played past him, while the ‘10’ doesn’t apply much pressure. The two banks of four tend to get vertically and horizontally compact, closing the space between them and making it difficult for the opposition to progress centrally. Dall’Oglio’s defensive tactics are very organised, requiring concentration and discipline from his players.

When defending deeper, Brest’s shape generally looks similar to figure 3 but the ‘10’ is more involved, as seen in figure 4, where he’s chasing the Marseille man attempting to dribble past him towards the midfield line of four.

The ‘10’ isn’t really required to press aggressively in the opposition’s half for Dall’Oglio but he plays an important defensive role inside his own half. He tracks back, supporting the midfield and ensuring that none of the midfielders get dragged out of position by this dribbler, which could lead to Brest’s defensive structure becoming weakening.

Thanks to this player’s diligent defensive effort, Brest’s deeper players can stay focused on closing space in deeper areas and getting in position to make blocks, with Brest blocking the fourth-most shots per 90 (2.98) of any team in Ligue 1 this season. As a result, the discipline, concentration and work-rate of the ‘10’ are important as Brest’s block drops deeper.

One potential area of weakness in Brest’s defensive setup is the space that they leave open out wide. In the previous two examples, we saw that Brest defend very vertically and horizontally compact, preventing the opposition from progressing the ball centrally.

This is also the case in figure 5 but here, the opposition intelligently make use of the space that Brest have vacated out wide through their defensive tactics to progress into the final third and create a goalscoring opportunity that they ultimately convert.

Dall’Oglio’s Brest in build-up

This section looks at what Brest typically do on the ball, what kind of passes they tend to make, and the importance of off-the-ball movement in the build-up and chance creation for Dall’Oglio’s side.

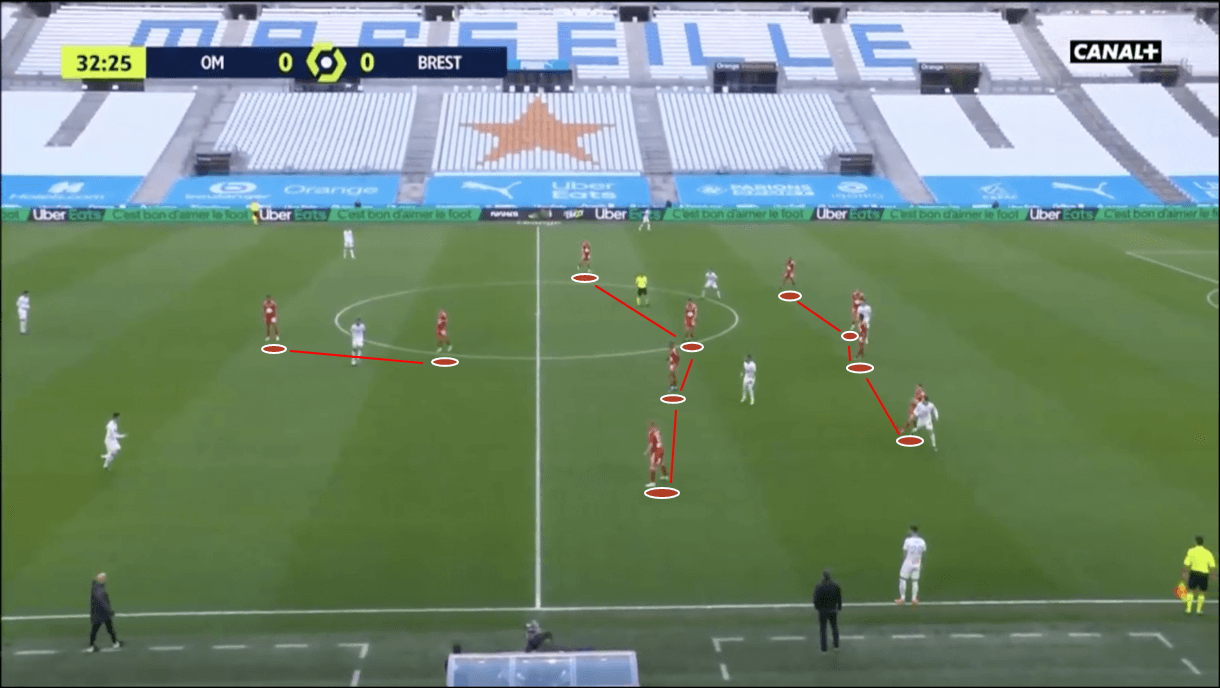

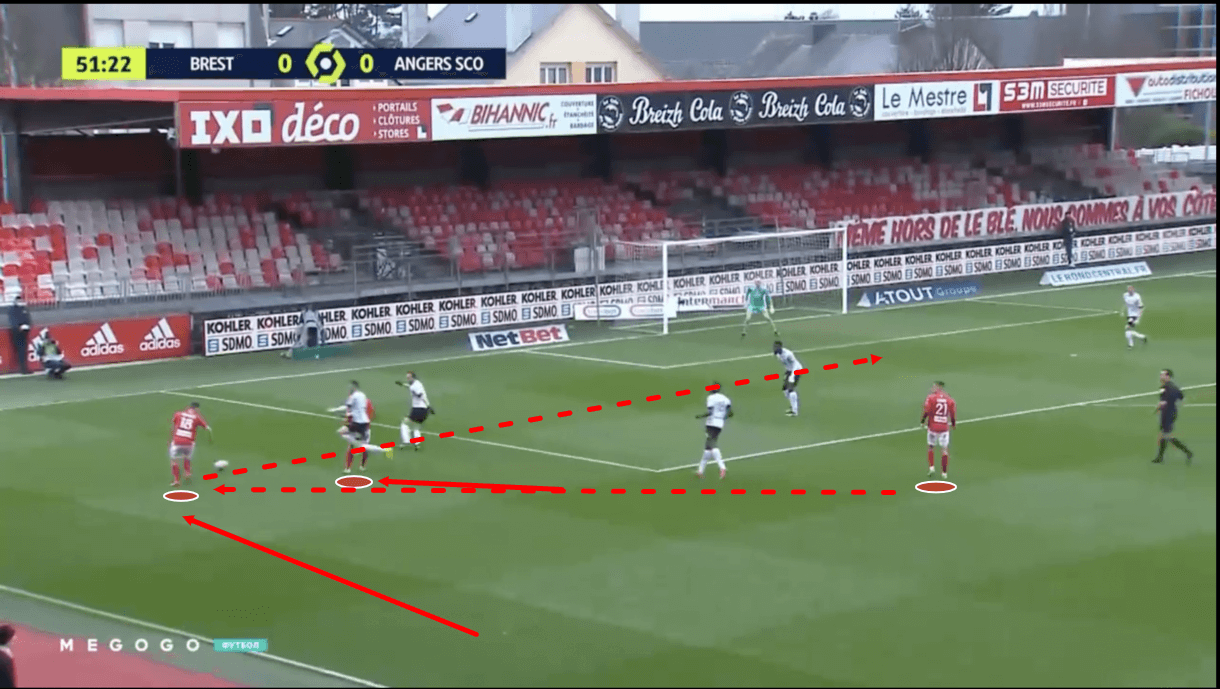

Similar to how Brest often have just two players in the backline while defending higher up the pitch, they also often have just two players in the backline during the build-up and just like when defending higher, this is because the full-backs get higher up the pitch, usually in line with the holding midfielders.

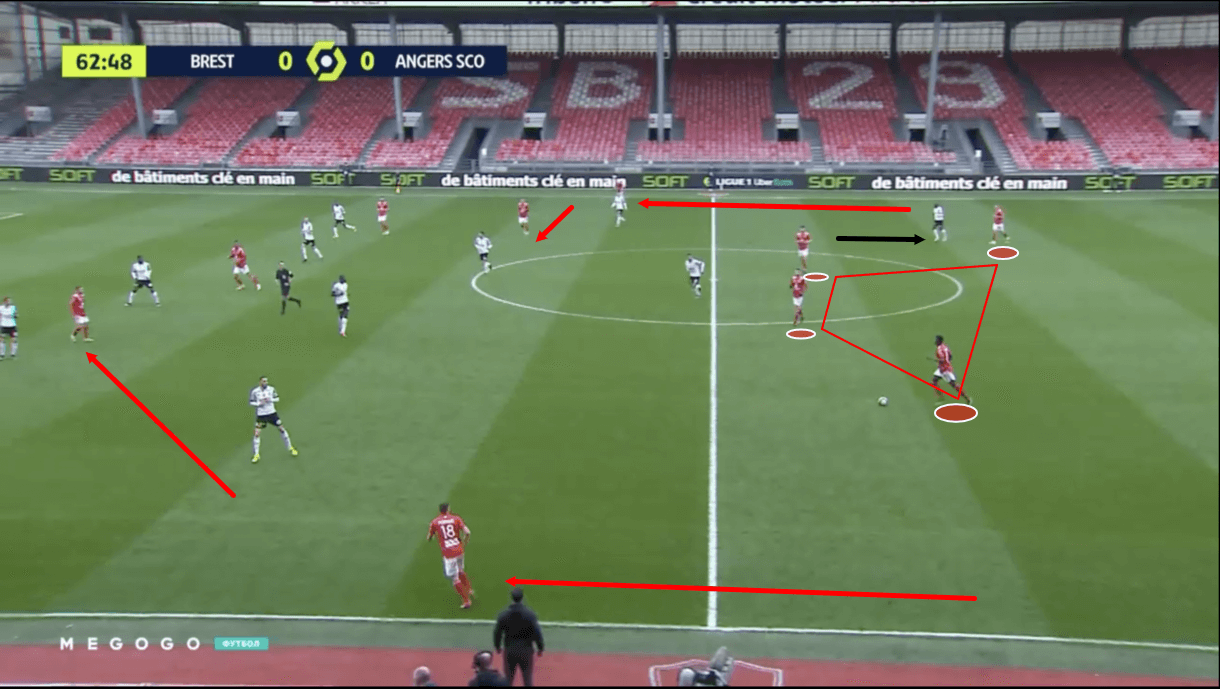

Figure 6 shows a typical example of Dall’Oglio’s side during the build-up when they’ve got two men in the backline. The full-backs push up, forming a four-man line with the holding midfielders. If they’re playing with a ‘10’, he advances into the forward line, while one winger moves centrally, becoming the new ‘10’, and the other winger advances into the forward line as well. This turns Brest’s shape into something of a 2-4-1-3, to label it.

Brest don’t always build up with just two men in the backline, they often build up with three men in the backline, as was the case in figure 7, where one of the holding midfielders has dropped deep, splitting the centre-backs. The other difference between this example and figure 5, is that instead of becoming a ‘10’, one winger has moved into central midfield. This forms a 3-4-3 shape – another very common shape to see Brest playing with during the build-up and more advanced stages of an attack.

Dall’Oglio likes his backline to be numerically superior to the opposition’s forward line by one man. In figure 5, Angers pressed with one forward, so Brest had a two-man backline. In figure 6, Marseille pressed with two forwards, so a holding midfielder dropped to create a one-man advantage for Brest with a three-man backline.

Dall’Oglio likes his backline to attract pressure from the opposition during the beginning of the build-up. The deep-lying players exchange lots of short passes at times, drawing the opposition up the pitch.

This creates more space further up the pitch for Brest and they are active in trying to quickly exploit that space. This sees them play plenty of progressive passes and long balls. Les Pirates have played the sixth-highest number of long passes per 90 (44.3) and the seventh-highest number of progressive passes per 90 (69.66) in Ligue 1 this term.

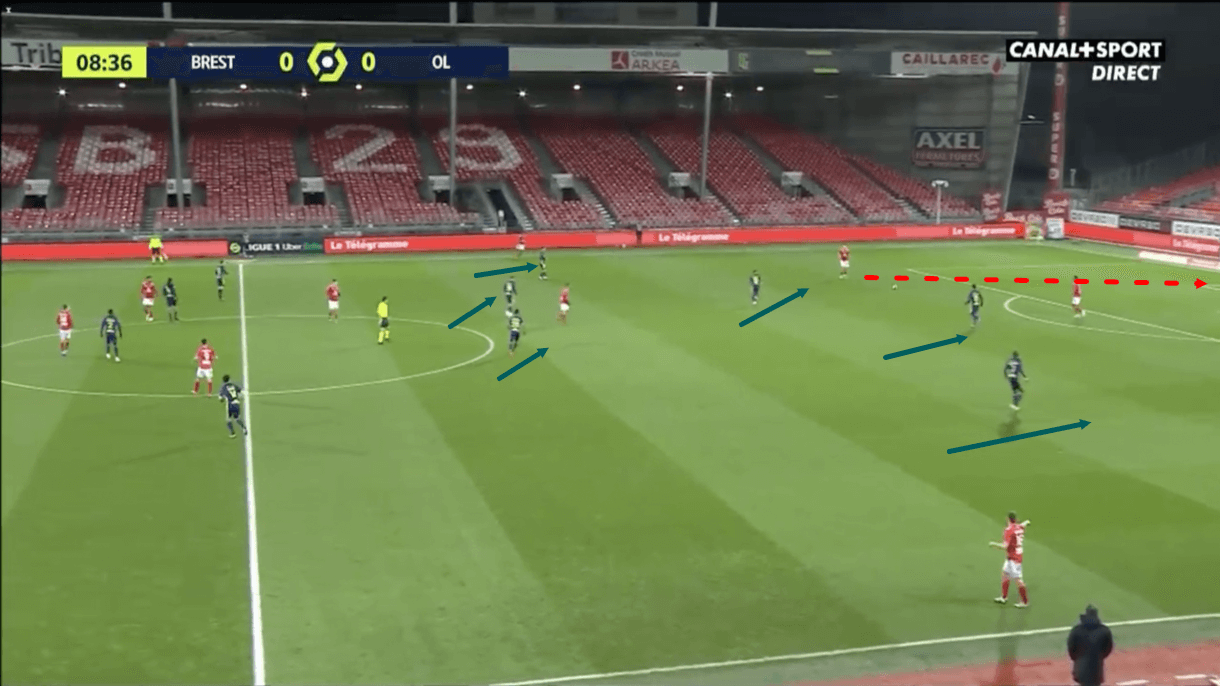

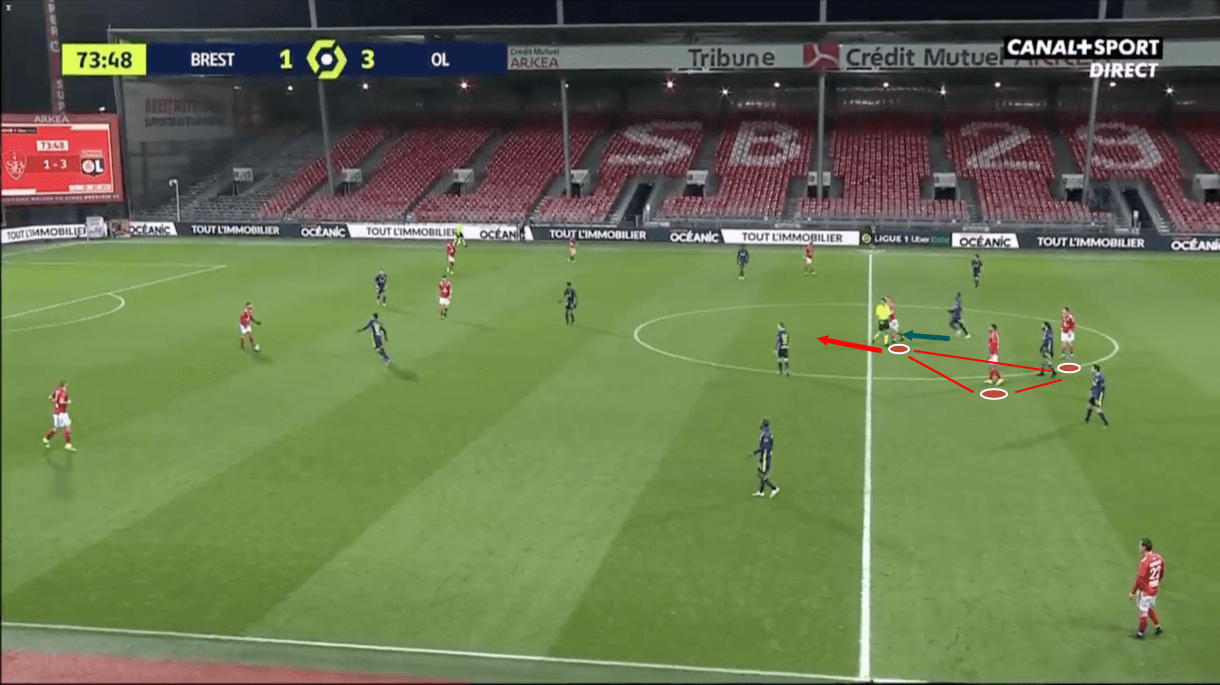

Their short passing tactics at the beginning of the build-up can be an area of weakness, however, as was the case in figure 8. The pressure they attract can lead to turnovers in dangerous positions if the opposition’s press is well-organised and/or if Brest’s deep players have technical mishaps.

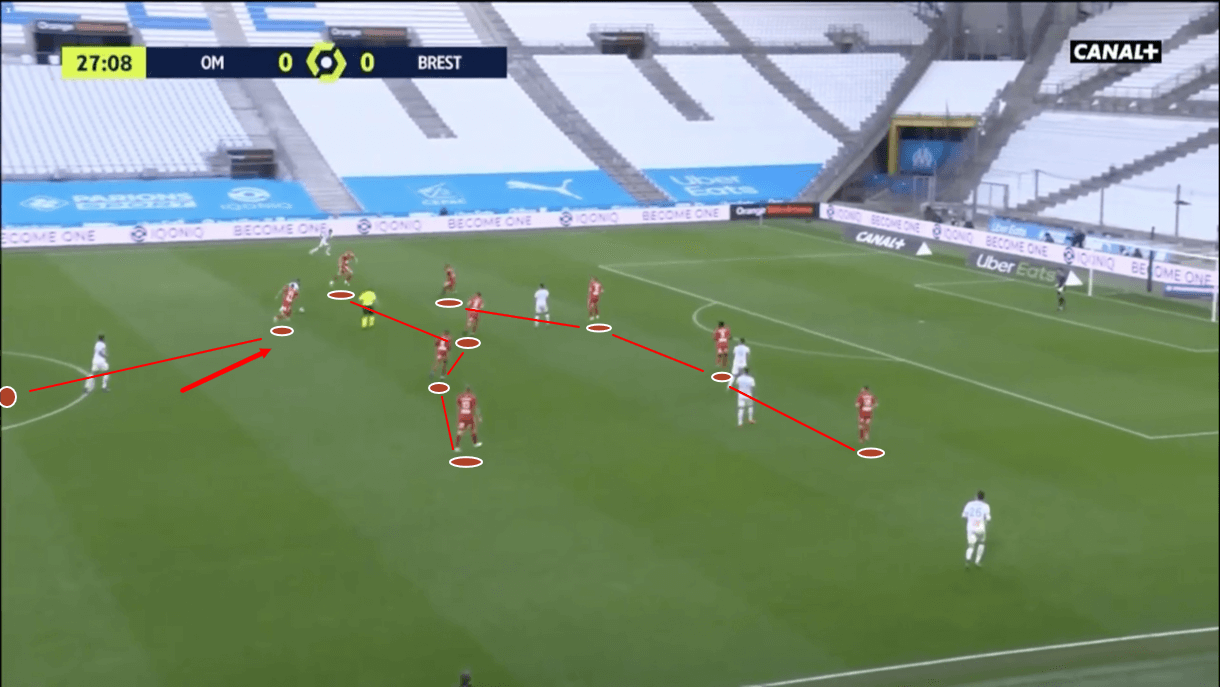

In this example, Lyon’s press was aggressive and well-organised. Brest’s right centre-back in possession was forced to play the ball back to the goalkeeper but Lyon then put the ‘keeper under a lot of pressure, forcing an error and scoring a goal.

Brest’s long balls are often effective for a couple of reasons. Firstly, they’ve got the joint-best aerial duel success rate (51.6%) of any team in France’s top-flight with PSG. A large amount of the credit for that goes to centre-forward Steve Mounié, who signed for Brest this past summer from Huddersfield Town after playing for them for three seasons – two in the EPL and one in the EFL Championship. He’s got a stellar aerial duel success rate of 58.7%, beating the league average by 10%.

He’s often the target of Brest’s long balls, as was the case in figure 9, where he pushed out from the centre to the wing to contest this aerial duel with the full-back, rather than the taller centre-back. He is excellent at winning aerial duels and knocking the ball onto runners in behind or down for his teammates to win the second ball and Dall’Oglio does well to exploit this strength by playing lots of long balls to him.

Most of Brest’s long balls come from the centre-backs and a key job of the attackers in Dall’Oglio’s system is to find space and create good vertical passing options for these players. As a result, the attackers’ movement is important for Brest in terms of progressing play and creating chances.

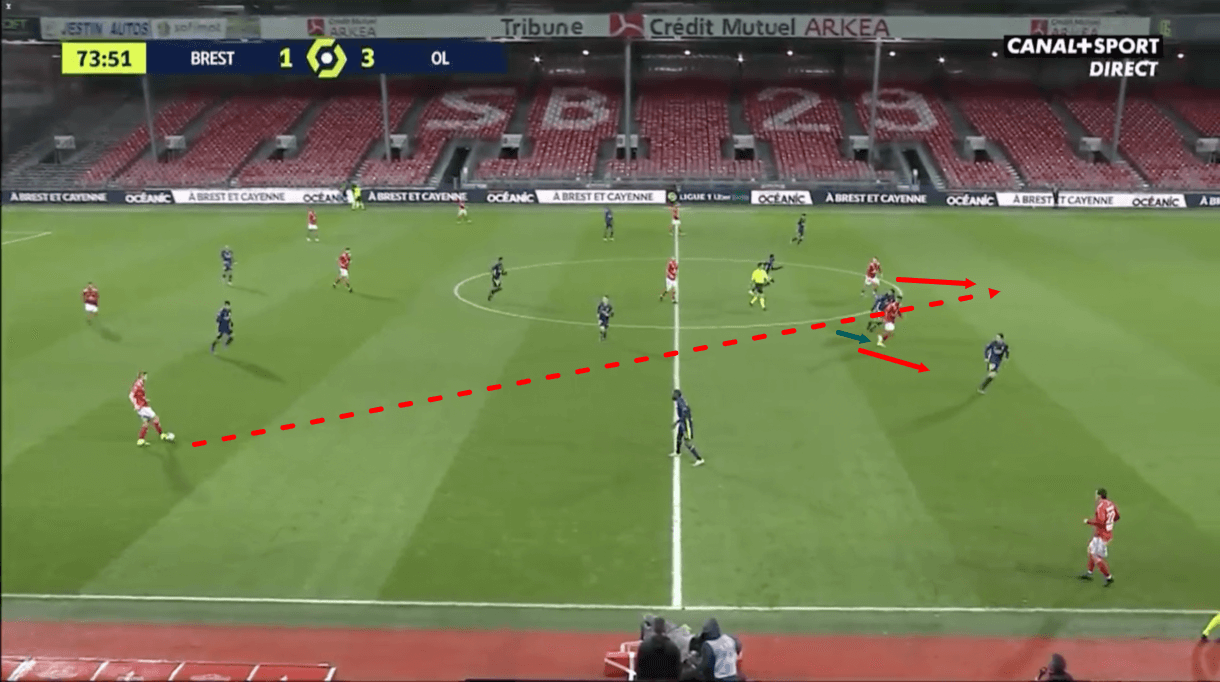

In figure 10, we see Brest in possession deep, during the build-up, while they’ve created a three-man front-line by transitioning into their offensive shape. This image shows an important element of Dall’Oglio’s decision to create a three-man frontline in possession and play with very advanced full-backs who provide the width, he wants to overload the opposition’s backline with his frontline to make them more difficult to defend against and to create options for the deep-lying players to exploit with their long passes.

Here, the Brest forwards have a 3v2 advantage versus the opposition centre-backs and they’re trying to create a free man for the deep-lying players to pick out via their movement. Firstly, the left forward drops deep, dragging the opposition’s right centre-back with him. If the centre-back didn’t follow him, he could have become a free man in between the opposition’s backline and midfield line.

Then, in figure 11, we see that Brest’s right forward begins making a run away from the left centre-back. This catches the left centre-back’s attention, who follows the runner. If he didn’t pick up the run, the centre-back could have played him through, as he would have enjoyed enough freedom to present danger.

As these two centre-backs got dragged out of position, this left the central centre-forward in plenty of space and as the play moves on, the centre-back picks this player out with a long ball over the top, playing him through on goal and assisting the second goal of the game for Dall’Oglio’s side.

Dall’Oglio’s Brest in the final third

Our final section provides an analysis of the tactics that Dall’Oglio’s Brest utilise inside the final third. This section will take a look at how wing play, specifically wide overloads and crosses, are key to Dall’Oglio’s side’s tactics in the final third.

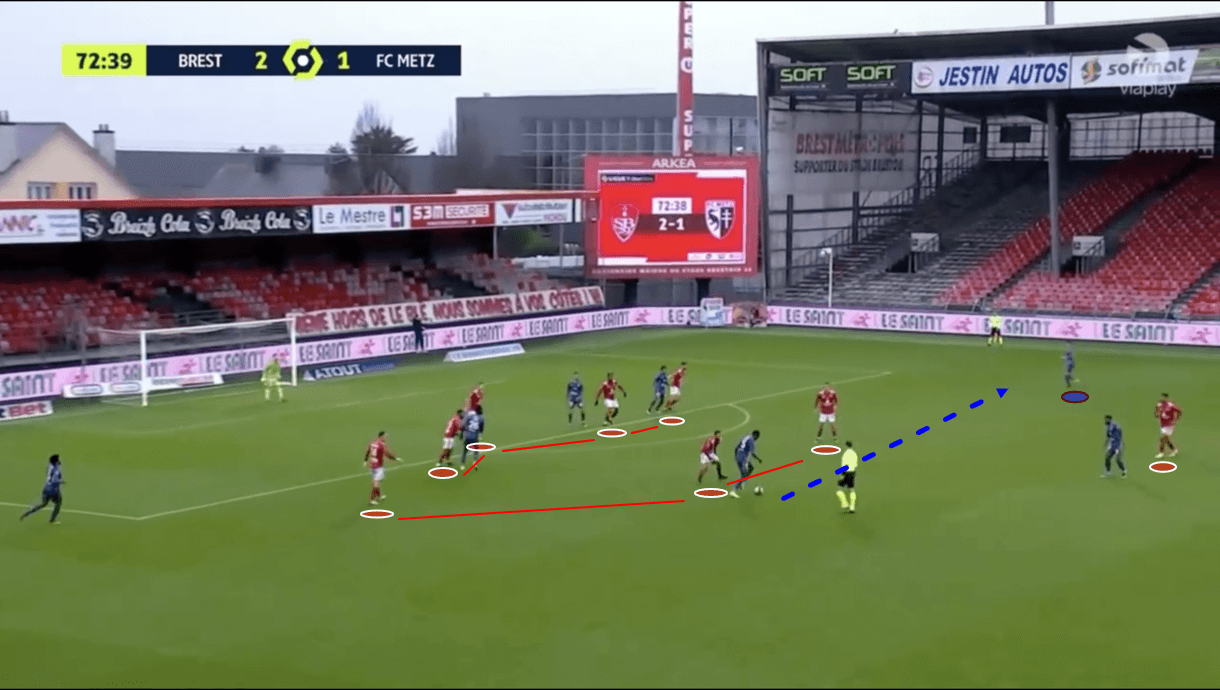

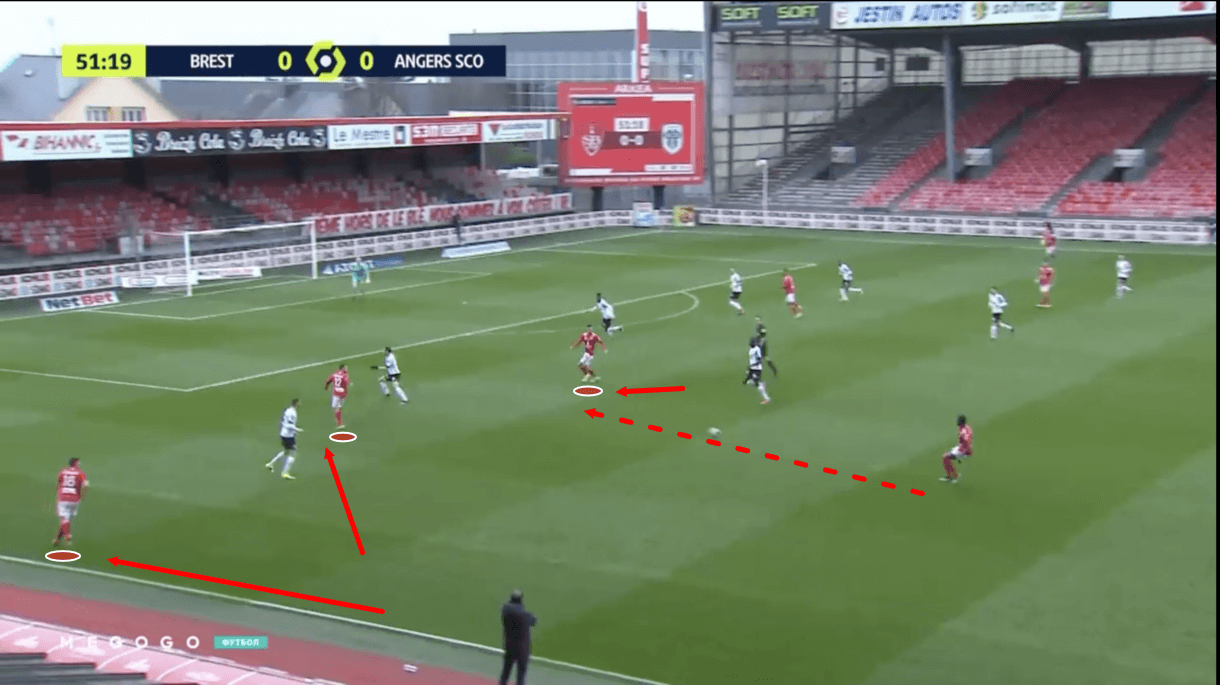

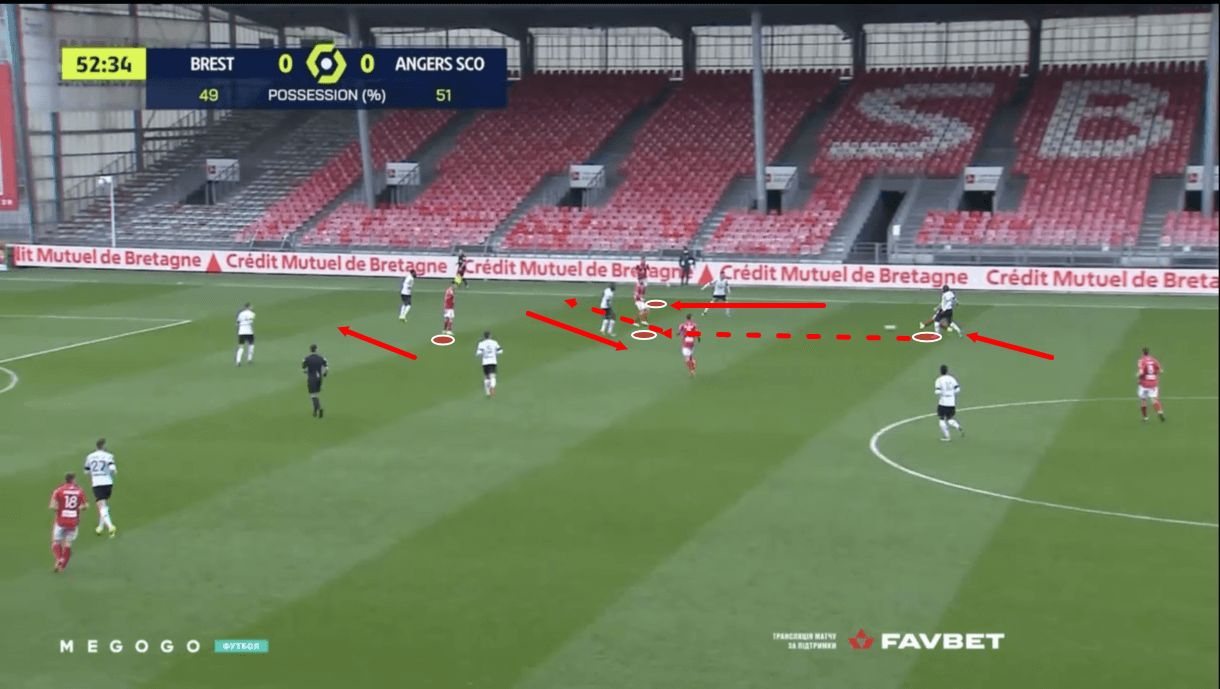

A large amount of Brest’s final third entries come via the wings and they manage this by overloading the opposition’s full-back and near centre-back. We see an example of this in figure 12, where Dall’Oglio’s men have created what is essentially a five-man frontline, with the full-backs overlapping and one winger joining the two centre-forwards/centre-forward and ‘10’.

Brest’s central centre-forward has shifted to the left, which creates a 3v2 for Les Pirates versus Angers’ right-back and right centre-back. As this player receives the ball, he could attempt to carry it into the box himself, play through the winger running in behind from the half-space or play through the overlapping full-back, and he opts for the latter, which is very common for Dall’Oglio’s side, who like to use the overlapping full-backs’ crossing ability and exploit the width inside the final third.

As the play moves on, in figure 13, the overlapping full-back receives the ball in enough space to line up and send a cross into the box first time, which, again, is typical of Les Pirates under Dall’Oglio – they tend to play plenty of first-time crosses, with the overlapping full-backs often receiving the ball in or around the final third in plenty of space.

Dall’Oglio does well to set his full-backs and wingers up for success with their crosses, as is evident by the fact that Brest have got the best cross accuracy (37%) of any team in Ligue 1 this season. Mounié’s aerial quality, as well as the crossers’ technical quality, are other key factors that help the Burgundy-based side to perform so well in this area but the 56-year-old coach’s offensive tactics that create wide overloads give the crossers an excellent platform to line up their pass and put the ball into the right areas too.

It isn’t always Brest’s full-backs that get played in behind from these positions as a result of the wide overloads, however, the wingers in the half-spaces and the centre-forwards also benefit from the wide overloads that their team creates by getting played through on goal.

Figure 14 shows an example of one occasion where this was the case. Just before this image, the right centre-back, who’s in possession here, carried the ball upfield and the right-back made his overlapping run up the wing. Meanwhile, the right-winger shifted inside, while the centre-forward also found himself positioned fairly wide on the right.

The right centre-back finds the right-winger in the half-space and this player quickly plays the ball out to the overlapping full-back. This draws the opposition full-back out and creates space for the centre-forward to run in behind him. As play moves on, the full-back plays the forward through, allowing him to attack the box.

The wingers get played through this area more often than the forwards, and the wingers tend to try and dribble into the box more often than the full-backs, who almost exclusively play crosses. As far as dribbles go, Brest’s wingers make far more than any other members of the squad. However, Brest have made the fewest dribbles per 90 (22.77) and the fourth-fewest through passes per 90 of any Ligue 1 side this season, so they do generally attempt far more crosses than they do dribbles or through passes to get into the penalty area, with the wingers also playing plenty of crosses, like the full-backs.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis of Dall’Oglio’s tactics, the highly-rated coach does well to accentuate some standout strengths of his team, such as Mounié’s aerial quality, though his tactics do leave his team exposed in other areas, such as when attracting pressure while playing out from the back.

On the ball, Dall’Oglio is keen on having a numerical superiority at the back and up front, resulting in his 4-2-3-1/4-4-2 turning into a 2-4-1-3/3-4-3 in possession. The 56-year-old’s team uses a healthy mix of short passes and long passes, along with the intelligent movement of those positioned higher up the pitch, to help Brest to create a free man in attack who can be played through on goal.

Off the ball, Dall’Oglio’s side is not very aggressive. When the opposition have the ball deep, one centre-forward and the wingers press high to force the opposition long, while the full-backs and holding midfielders tend to play the role of ball-winners far more than anyone else. For the most part though, Brest’s defensive tactics are relatively passive for Ligue 1, with an emphasis on discipline and organisation to close space in central areas and make it difficult for the opposition to progress through the centre.

Comments