FC Sochaux-Montbéliard (Sochaux) currently sit second in Ligue 2 — trailing only Toulouse who boast an extremely strong squad for this level — and have conceded the joint-fewest goals (7) of any Ligue 2 side, 13 games into the 2021/22 campaign. This impressive defensive record hasn’t come by accident; it’s the product of the system that Sochaux manager Omar Daf has implemented and perfected during his time in charge of Les Lionceaux — the club at which Daf spent the majority of his playing career. Last season, Sochaux finished in seventh place on the Ligue 2 table but boasted the joint-fourth-best defensive record in terms of goals conceded of any side in France’s second tier at the end of the season.

That second-place finish was Sochaux’s best finish in the second-tier since being relegated from Ligue 1 way back in the 2013/14 season. Daf has overseen steady progression since returning to Stade Auguste Bonal as the manager in November 2018, when he replaced José Manuel Aira. He guided his side to a 16th place finish in that first season before following it up with a 14th place finish in 2019/20.

Now, in his fourth season in charge of the club where he once played as a right-back against the likes of Serie A giants Inter, Bundesliga stalwarts Borussia Dortmund, and talk-of-the-town EPL side Newcastle United in European competition back in the early 2000s — a better time for this club — Daf looks set to take Sochaux one step further in their progression and challenge for promotion back to the top-flight, where you might feel a club of this stature belongs, depending on your level of sentimentality for historic clubs.

Jean-Claude Plessis, who was the club’s president during the majority of Daf’s playing career at Montbéliard-based side, recently sang the praises of his former player, declaring that the 44-year-old coach has an “immense aura” before gushing over his Sochaux team’s performances, saying he has “the impression that everyone is happy to be on the pitch” at Les Lionceaux under Daf, with Sochaux practising “beautiful football” at present.

Plessis’ high praise is justified, given Sochaux’s positive progression under their 44-year-old manager and I intend to uncover some of the key tactics behind Les Lionceaux’s “beautiful” and effective football in this tactical analysis. I’ll attempt to provide insight into Daf’s overall philosophy through analysis of his Sochaux side and their development under him in what is now the ex-Senegal international’s fourth season in charge at Stade Auguste Bonal.

Whether or not Daf’s philosophy and Sochaux’s positive start to the campaign are enough to take France’s first professional club back to Ligue 1 remains to be seen but what is for sure is that this team is continuing to steadily progress well under the 44-year-old who has shown unwavering belief in his convictions throughout his tenure in charge of the two-time French champions, recently explaining that he’s not done anything differently this season than he did in previous seasons, saying: “For 3 years I have been working in the same way. This year it is working well in terms of results but I have always stayed on my line.” With Les Lionceaux enjoying a positive start to the season that follows the steady progression of Daf’s first three seasons at the club, the manager’s confidence and belief in his convictions should be highlighted as a likely important contributor to his side’s potential promotion challenge.

Pressing and aggressiveness

As well as conceding the joint-fewest goals of any Ligue 2 side this term, Sochaux have allowed their opponents to generate the lowest xGA (7.83), as well as the lowest xGA per shot (0.072) of any team in France’s second tier. The success of Daf’s side is built on their defensive solidity and to kick off the tactical analysis, I’m going to focus on Sochaux’s game without the ball in the high block phase of play. At present, Les Lionceaux have got the fourth-lowest PPDA (8.92) of any side in France’s second tier. This indicates that they’ve got the fourth-most aggressive press of any side in the league, as they allow the opposition to complete the fourth-fewest passes inside their final 60% of the pitch before committing a defensive action (a defensive duel, tackle, foul or interception).

Sochaux have primarily lined up in the 4-2-3-1 shape under Daf and they’ve almost exclusively used this formation so far in 2021/22. The centre-forward and number 10 sometimes end up in the same line without the ball. However, it’s then up to one of these two players to lead their side’s press.

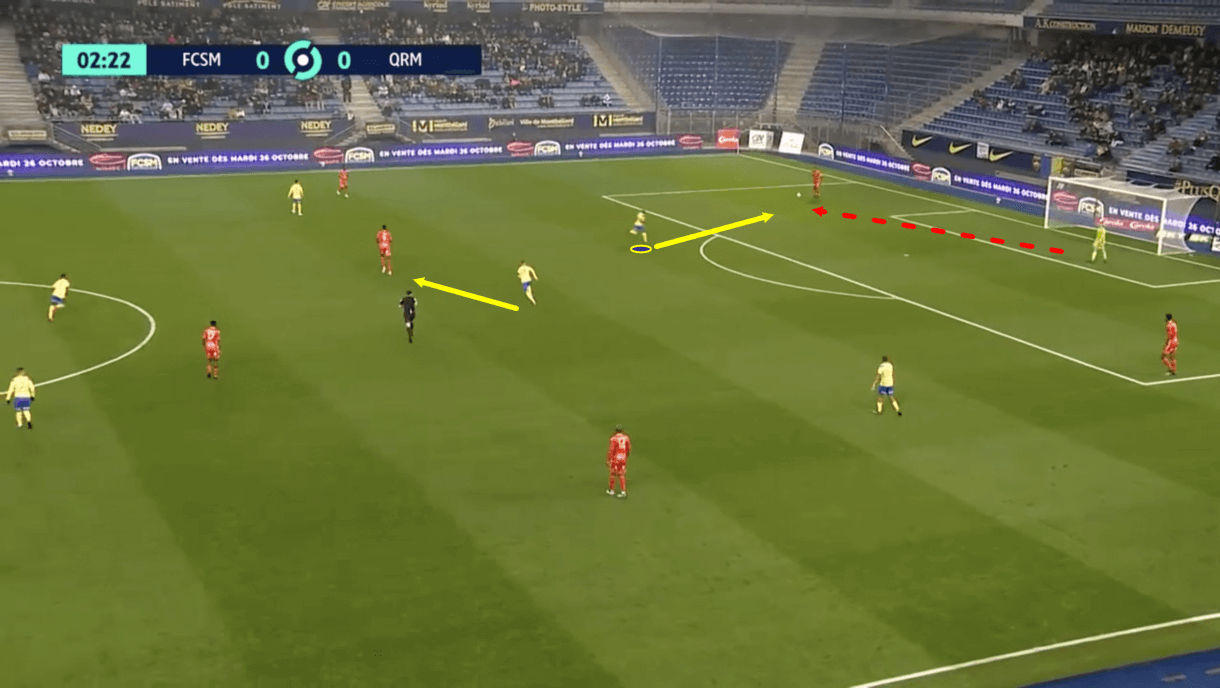

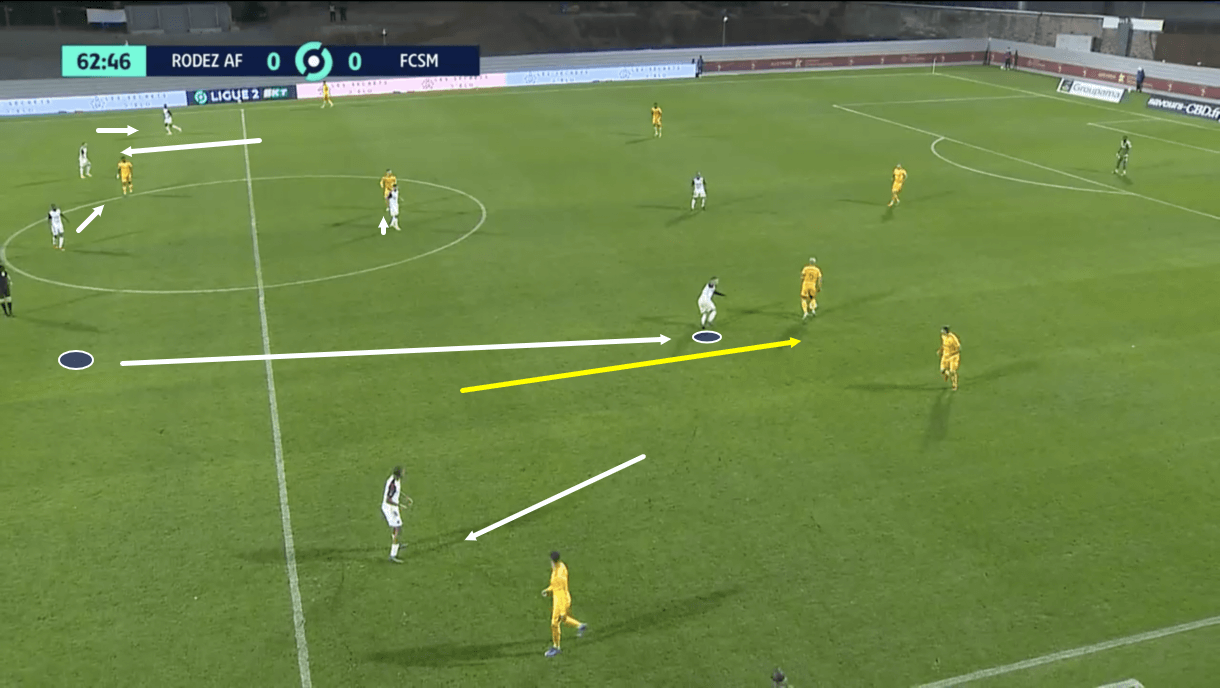

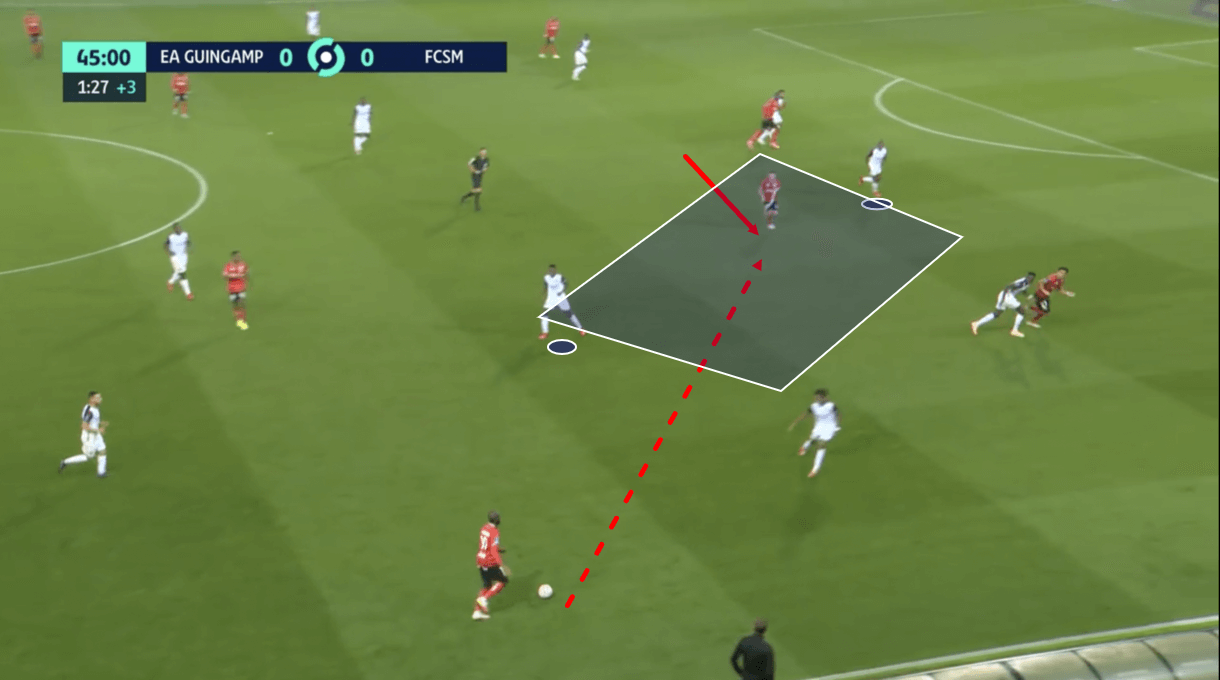

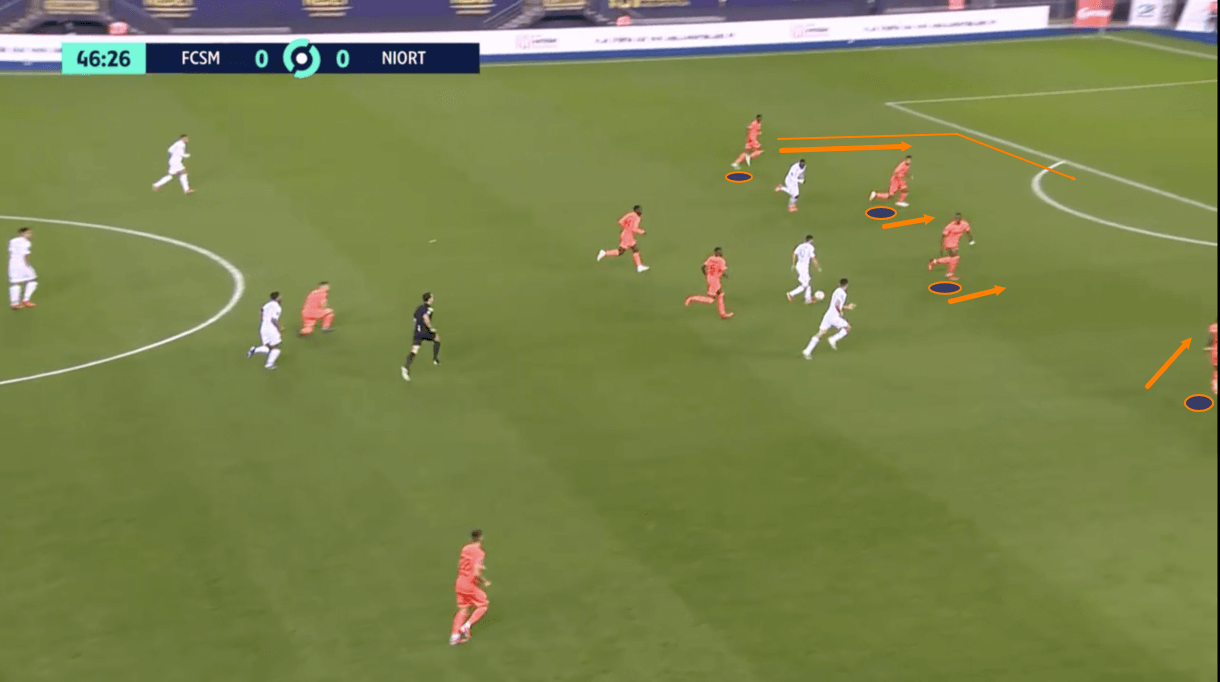

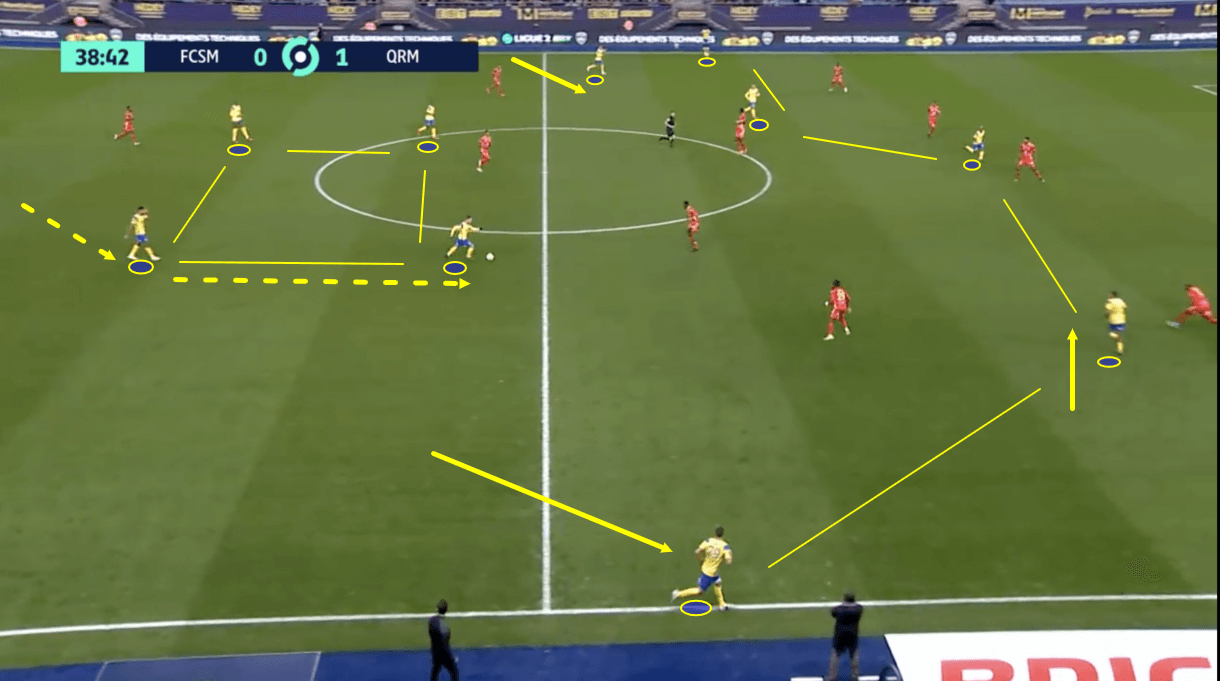

As was the case in figure 1, it’s more common to see Sochaux’s centre-forward leading the press. When this happens, it’s then up to their ‘10’ to drop onto the opposition’s deepest midfielder to avoid getting overloaded in central midfield. Just before figure 1, the opposition’s goalkeeper played the ball out to the right centre-back, whom we see in possession here. As this centre-back receives the ball, Sochaux’s centre-forward springs into action closing him down while the ‘10’ drops to mark the holding midfielder. Sochaux’s ball-near winger gets tight on the opposition’s ball-near full-back, while their ball-far winger retains access to the other centre-back. Les Lionceaux’s two holding midfielders sit behind the ‘10’, resulting in the scene we see here in figure 1.

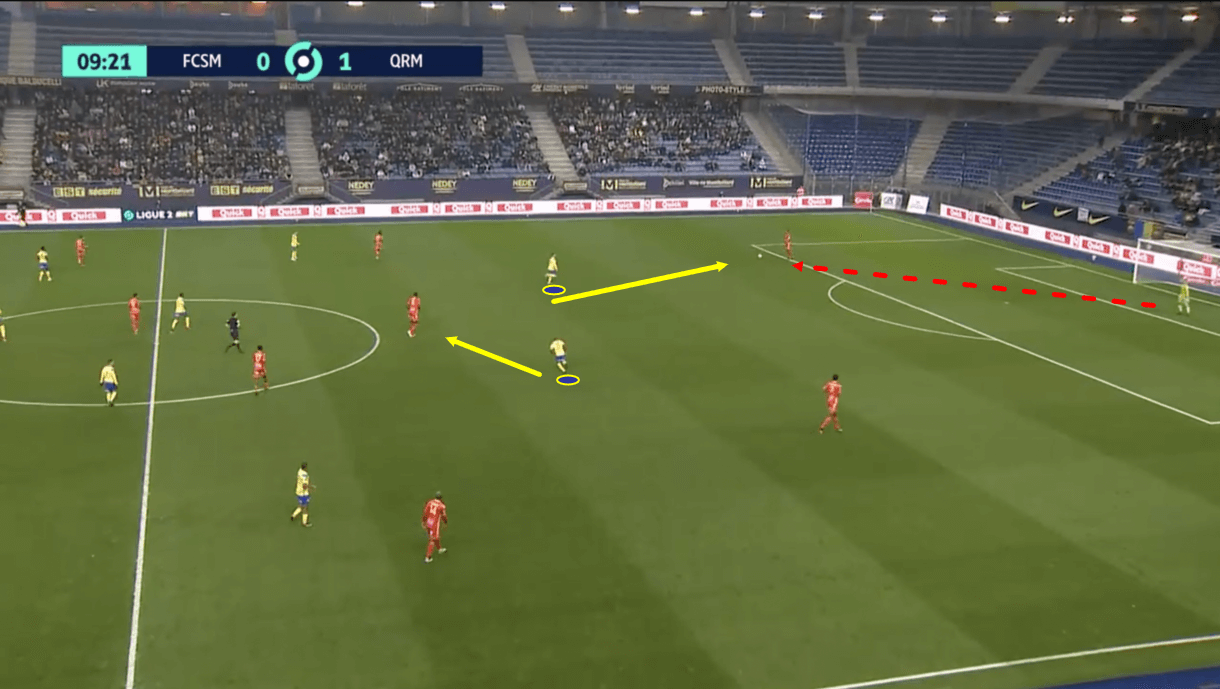

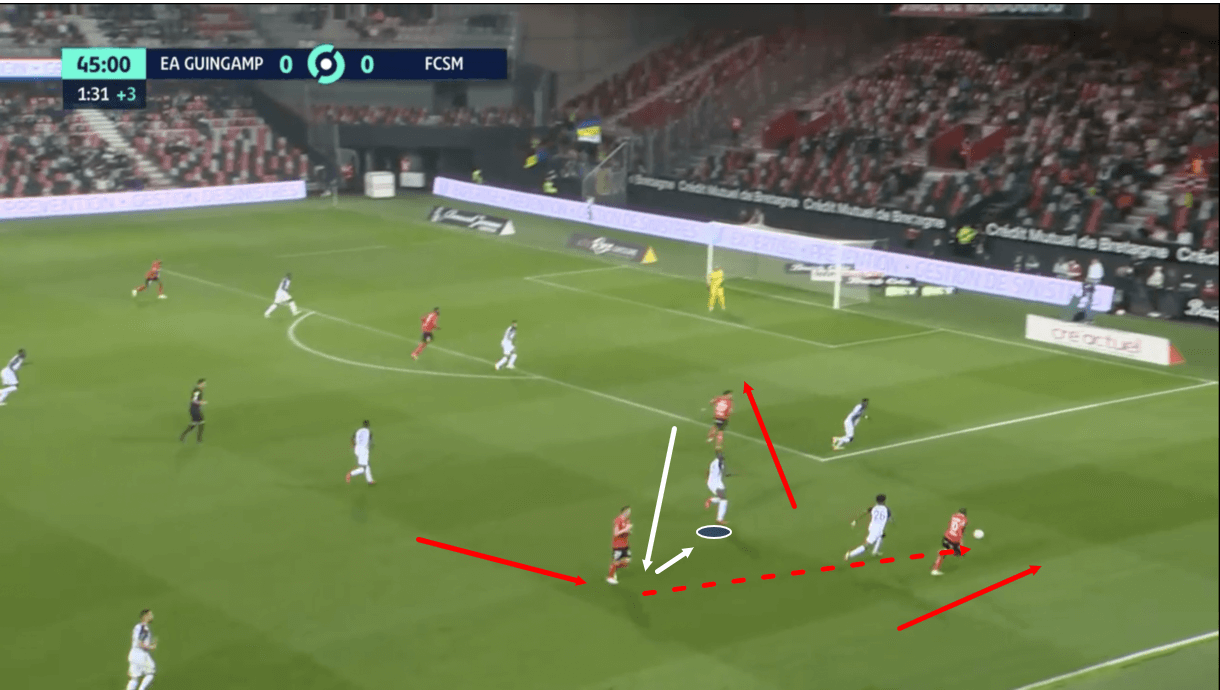

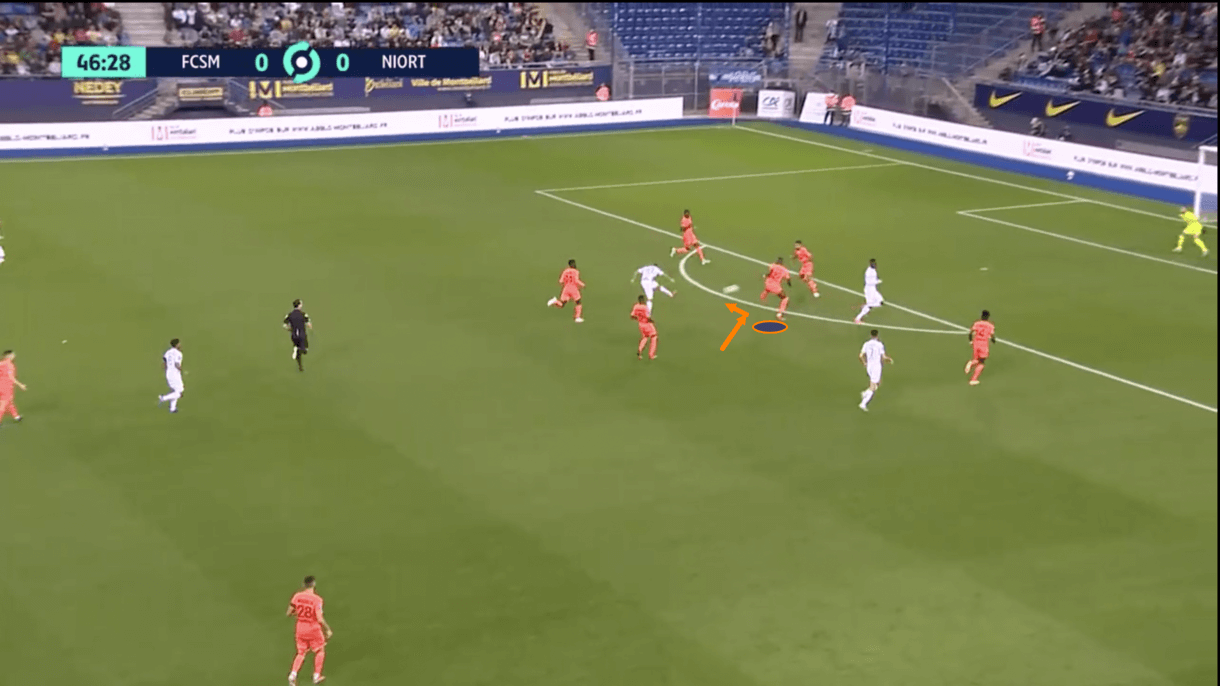

Figure 2 shows an example from this same game of Sochaux’s ‘10’ leading the press. On this occasion, with the opposition positioned slightly further upfield than they were in figure 1, the ‘10’ was positioned closer to the opposition’s centre-back receiver than the centre-forward was while the two men stood on the same line, so it made more sense for the ‘10’ to close the receiver down. As the ‘10’ pressed, the centre-forward dropped off onto the opposition’s deepest midfielder, similar to how the ‘10’ dropped off in figure 1. Again, with the opposition positioned slightly further upfield here, both of Sochaux’s wingers are marking the opposition’s full-backs, allowing the centre-back without the ball to enjoy some space. Ideally, the player leading the press — in this case, the ‘10’ — will bend his run to cut the passing lane to the other centre-back. However, in this example, that wasn’t the case.

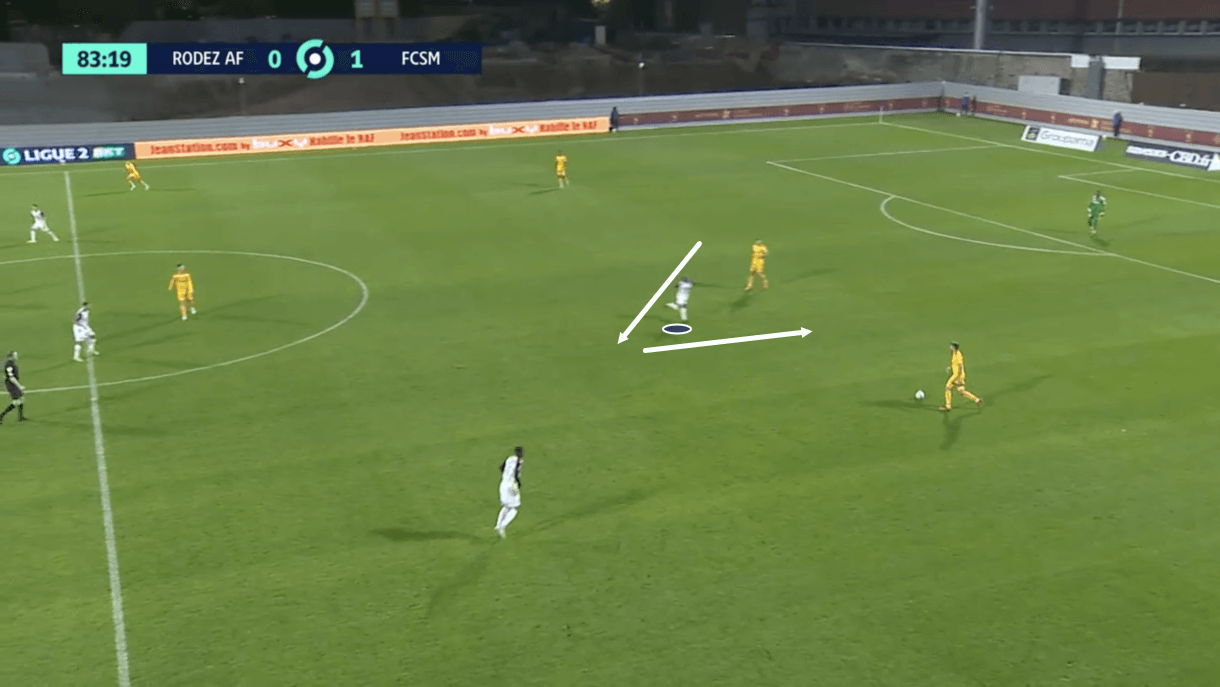

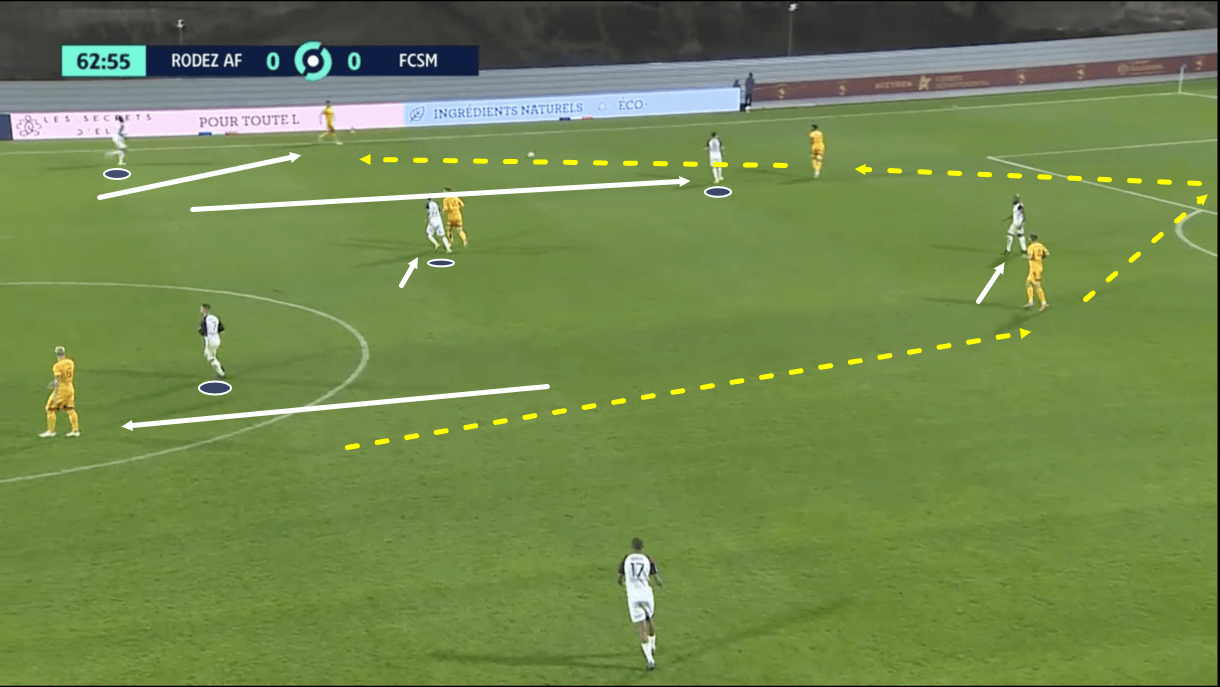

Usually, though, Sochaux’s furthest forward defender will bend his run to perform this action, as was the case in figure 3. Here, Sochaux’s centre-forward can be seen closing down the opposition’s left centre-back. However, instead of running straight at the man on the ball, the centre-forward bends his run to cut off the passing lane to the central centre-back while also threatening the passing lane back to the goalkeeper. This nudges the left centre-back into deciding to carry the ball forward on his own, at which point pressure increased on him both from Sochaux’s right-winger from the front and the centre-forward from behind, rushing the ball carrier into his next decision with limited options.

Cutting off passing lanes like this is a vital part of the furthest forward defender’s role within Daf’s pressing system. For example, in figure 3, this is what allows the wingers and ‘10’ to sit deeper while the centre-forward presses the opposition’s backline alone, giving Sochaux more protection in the all-important central areas closer to their goal.

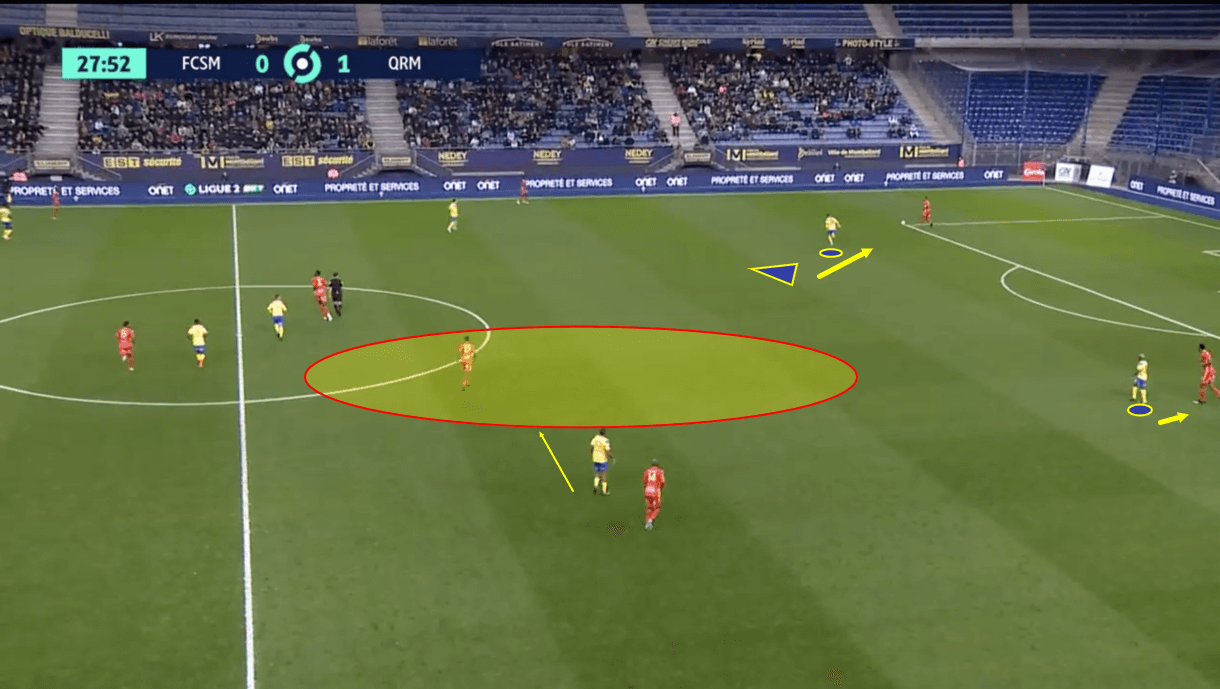

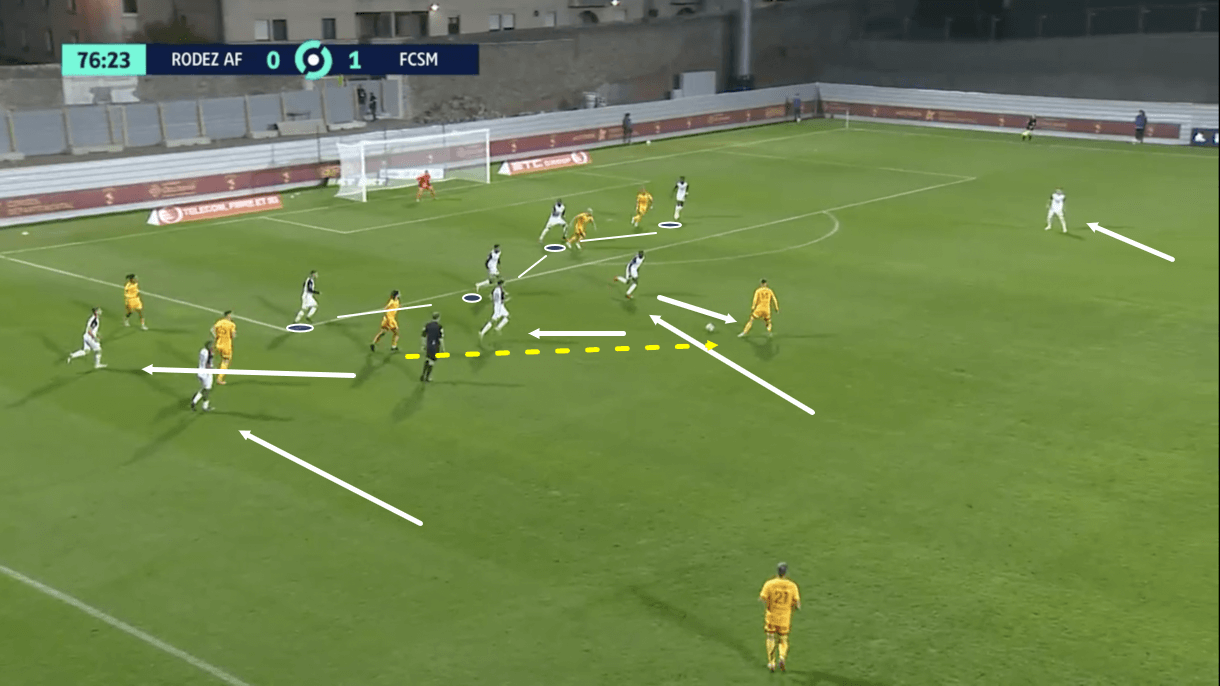

If neither the ‘10’ nor the centre-forward drop onto the opposition’s deepest midfielder while the other leads the press, it can leave Sochaux very exposed in the centre of the pitch, which is why good spatial awareness, scanning, and good tactical understanding concerning their specific roles in this pressing system are so important for Les Lionceaux’s ‘10’ and centre-forward. In figure 4, we see an example of an occasion where neither of these two players performed their duty of dropping onto the opposition’s holding midfielder. As a result, the opposition enjoy a 3v2 overload in central midfield, with the holding midfielder enjoying a lot of space.

Sometimes, when this does happen — which is just occasionally, as usually these players are aware of their surroundings and diligent in performing their covering duties — you’ll see Sochaux’s ball-far winger come into the centre to provide extra protection closer to the ball. At this moment, the right-winger is marking the left-back as he typically would, so isn’t performing this role. However, sometimes we do see the ball-far winger operate more ball-oriented and get closer to the nearest passing option, which also provides extra protection for Sochaux in the centre. Here, he opted to guard against the switch of play by staying closer to the left-back, leaving the centre exposed, even with the ‘10’ protecting it somewhat by keeping the opposition’s holding midfielder in his cover shadow. It wouldn’t be too difficult for the holding midfielder to get out of the cover shadow and into a good position to receive, while it’d also be possible for the right centre-back to find him with a lobbed pass into the centre here, so the opposition still enjoy plenty of options to exploit this central overload.

When the player, usually the ‘10’, does drop onto the opposition’s holding midfielder, they and the two holding midfielders behind them in Sochaux’s 4-2-3-1 system tend to operate in a very man-oriented manner. It’s common to see Sochaux’s holding midfielders follow opposition midfielders deep, for example if they carry the ball towards their own goal. This can lead to Sochaux’s shape distorting a bit, as was the case in figure 5, where the right holding midfielder ends up the second-furthest man forward for Sochaux due to his aggressive marking.

The centre-forward (or ‘10’ if he’s further forward) and wingers act more ball-oriented when pressing high, as well as space-oriented when defending deeper. However, the central midfielders defend in a very man-oriented fashion, which is an important distinction to note about Daf’s pressing tactics.

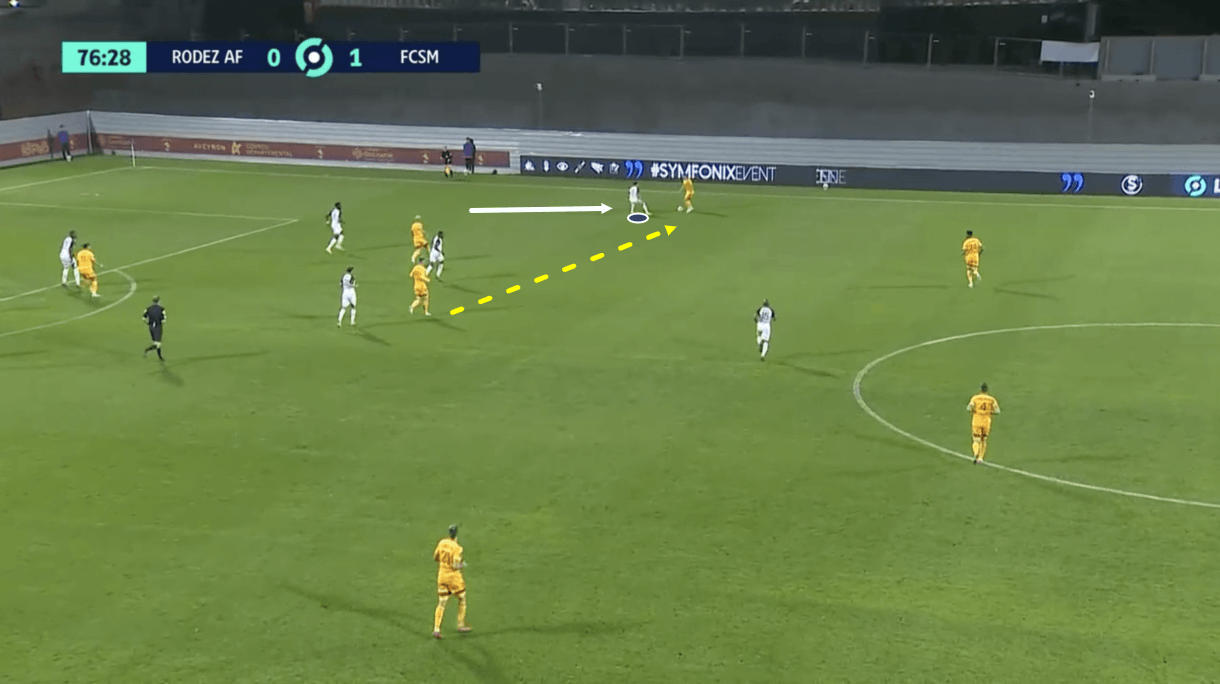

As this passage of play moves on, we see the image from figure 6 form. After playing the ball backwards under pressure from Sochaux’s right holding midfielder, the opposition midfielder began to move into Sochaux’s half again and he was followed by Sochaux’s right holding midfielder, again, as a result of his ball-oriented nature. The opposition end up moving the ball back to the goalkeeper before ending up with the right wing-back.

Sochaux are happy to force the opposition to play through the wide areas via their pressing system. Their central players are very man-oriented and restrict the space that the opposition’s central players enjoy in midfield. Meanwhile, Sochaux’s wingers will generally press deep wide men, like the full-back or, in this case, the wide centre-back — who we see Sochaux’s left-winger pressing high above — while blocking passing lanes into central midfield by keeping those midfielders in their cover shadow. This will typically force the opposition to move the ball out wide where Sochaux enjoy the advantage afforded to them through the sideline, which essentially acts as an extra defender for the pressing side as it significantly reduces the amount of space the opposition have to play the ball through.

As a result, Sochaux can increase their pressing intensity at this moment as the ball moves out to the opposition’s right wing-back and try to force a turnover in an advantageous position. Sochaux’s winger is supported closely by the left-back at this moment, who aggressively presses the opposition’s right wing-back as he receives possession to force the turnover. This passage of play highlights how the different roles within Sochaux’s defensive system ultimately protect the higher value areas in the centre of the pitch while forcing the opposition into positions where Sochaux’s press is more likely to force a turnover and set up a dangerous counter-attacking opportunity for Les Lionceaux.

Similar to figure 4, which showed what can happen when, for one reason or another, neither Sochaux’s centre-forward nor ‘10’ drop onto the opposition’s holding midfielder, figure 7 shows an example of how the opposition can find space in central midfield when one of Sochaux’s holding midfielders or the ‘10’ fail to pick up the correct man. Here, Sochaux’s ‘10’ can be seen marking the opposition’s right central midfielder, while Sochaux’s right holding midfielder is marking the opposition’s left central midfielder. Meanwhile, Sochaux’s left holding midfielder is sitting in his base position close to his holding midfield partner but without any opposition player nearby. Ideally, the left holding midfielder would pick up the opposition’s right central midfielder here but with the ‘10’ already on this man, the holding midfielder stays put.

This misunderstanding/miscommunication between Sochaux’s midfielders leads to the opposition’s holding midfielder finding space to receive deep in the centre of the pitch. Had the ‘10’ been higher, marking this player, and the left holding midfielder been marking the corresponding central midfielder, then this pass would’ve been prevented but as we can see, that’s not what happened. This highlights how Sochaux can be exposed in central midfield if the midfielders fail to get their defensive positioning right and allow an opposition midfielder to find space. One small error from these players, with someone losing their man, can lead to Sochaux’s defensive system breaking down, allowing the opposition to progress via a dangerous area.

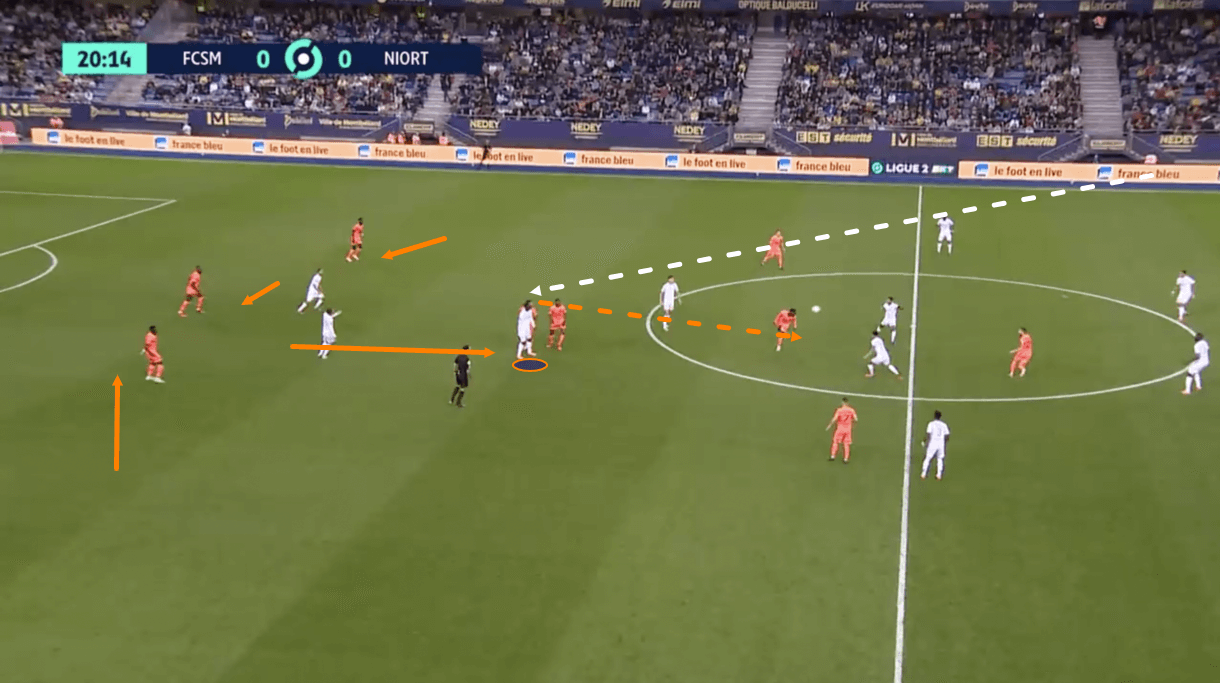

With Sochaux’s forward generally pressing high on the opposition backline and their midfield line generally defending in quite a man-oriented fashion, that could result in space opening up between the aggressive midfield line and the backline. To prevent this space from opening up and to prevent the opposition from using it to hurt Sochaux, their backline also tend to defend quite aggressively, getting tight to opposition attackers who come into their zone and following them if they drop deep. We see an example of this in figure 8, where Sochaux’s right centre-back was dragged forward by an opposition attacker who dropped in between the lines as a long ball was played upfield from the back.

We can see that there was quite a significant gap between Sochaux’s midfield and defensive lines for the opposition attacker to drop into and try to exploit Les Lionceaux. However, as he was aggressively followed by the centre-back, who ultimately won the aerial duel and regained possession for Sochaux, he was prevented from exploiting that space. This is the purpose of the aggressive approach Daf wants his centre-backs to take when defending higher and directly against attackers who want to drop into this space between the lines.

As one defender steps out, it’s then important for the other members of the backline to provide cover for the aggressive defender. We see this in action above with the remaining three members of the backline closing into the centre and forming a back three to prevent a big gap from opening in the backline where the aggressive centre-back stepped out. Had they not done this and if the opposition had won the aerial duel, then the ball could’ve been sent into the gap for a more advanced attacker to exploit so it’s clear how this effort to make the backline more compact to provide cover for the aggressive centre-back makes a solid safety net for Sochaux.

If the centre-back doesn’t step out quickly enough, then the opposition can successfully exploit the space in between Sochaux’s midfield and defensive lines, which can be devastating, so the centre-backs’ decision-making and awareness of their surroundings are very important in Daf’s system. Figure 9 shows an example of one occasion when an opposition attacker did drop in between the lines unmarked, leading to him exploiting that space and ultimately creating a goal for his side. Here, we see that while the opposition’s right-back carries the ball forward, an attacker is dropping in between the lines while moving from the left side of the pitch towards the right. This intelligent run helps him to stay out of the left centre-back’s radar for longer than if he had just dropped directly from the right-forward position.

Sochaux’s left holding midfielder is focused on aggressively defending what’s in front of him but fails to see the danger coming behind him. The midfielder should’ve scanned more to be more aware of his surroundings here, which could’ve helped him to adjust his positioning to cut this passing lane out. With neither this midfielder nor the left centre-back nor the left holding midfielder picking up this attacker, he can receive a forward pass between the lines in a dangerous position. As he receives the pass, the left centre-back does come out to engage him in a defensive duel, but by that point, he’s far too late.

As play moves on into figure 10, we see that the centre-back was caught in no man’s land as the attacker received between the lines before playing the right-back, now positioned much higher, through on the right-wing. Meanwhile, the opposition’s right-winger has cut into the space vacated by the left centre-back that Sochaux have been unable to fill due to the centre-back’s late decision to step out. As play moves on from here, the right-back can find the winger in this space inside the box before scoring to put them 1-0 up against Sochaux.

This passage of play in figures 9 and 10 again highlights how coordination is so important within this Sochaux defensive system. If one player is not alert enough, that can spiral into a big chance being conceded as all it can take is one slip-up for this system to unravel. This may be the biggest negative of Daf’s aggressive defensive system. Any incoordination between the ‘10’ and centre-forward, the ‘10’ and holding midfielders, or the holding midfielders and centre-backs can lead to a free man enjoying space in a central area, which can hurt Les Lionceaux badly, as was the case in figure 10.

In general, Sochaux’s defensive system is set up to primarily protect the centre and force the opposition into lower-value positions, which they’ve generally been quite successful at achieving this term, as is evident from the impressive defensive numbers we mentioned at the beginning of this section. However, it’s a system in which one individual mistake can spiral into a significant issue for the team by allowing the opposition to cut through the centre, as this section of analysis has also highlighted.

Defending deep

In the low block phase, Sochaux will typically drop into a 4-5-1 shape. This shape is naturally formed with the back four getting tight and compact well within the width of the penalty box, while the ‘10’ and wingers join the same line as the holding midfielders just in front of that compact back four. The ‘10’ and holding midfield duo provide protection centrally, with those three bodies acting as a solid central base to prevent the opposition from cutting through the midfield, along with the compact back four behind them. Meanwhile, the wingers provide coverage on the wings to prevent Sochaux from getting penetrated outside the width of their defensive block.

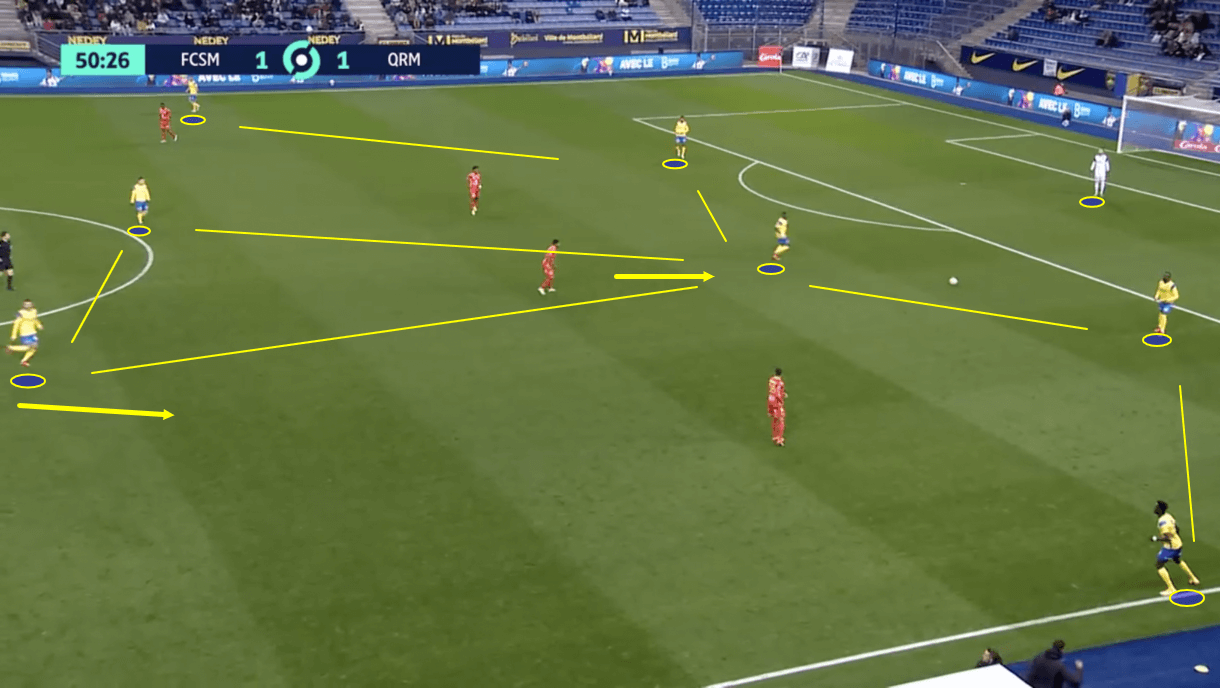

With that in mind, figure 11 then shows an example of how Sochaux’s 4-5-1 shape looks in-game during the low block phase. One important thing to note is that here, Sochaux have got just two men in the centre and an extra man on their right-wing. This is because the right holding midfielder shifted out from the centre to the wing to provide some extra support for the right-winger and prevent the opposition from progressing into the box from their left-wing. The three-man midfield, along with the compact four-man backline behind them, gives a midfielder license to push out wide and provide support to the winger where necessary. They must be careful not to allow the opposition to pull them around too much and exploit the centre, but this can help to prevent opposition dribblers from breaking through Sochaux’s defensive shape via the wing and prevent crosses from making into the box.

Additionally, in figure 11, we see that an opposition pass has just been played from the player in the left half-space to a more central player. As this central player receives the ball, he attracts increased pressure from the nearest Sochaux midfielder. It’s worth noting that this is a significant part of Sochaux’s defensive tactics in the low block phase. It’s common to see the nearest man to the ball aggressively close down opposition receivers as soon as passes are played to them. Daf wants his side to aggressively close down players as soon as they receive the ball for the opposition in this phase. This often doesn’t result in tackles, interceptions or even active defensive duels, but it can pressure the opposition receiver into rushed decisions while also limiting their options on the ball thanks to the pressing defender limiting the space they have to play into. Here, as the central player received the ball for the opposition, Sochaux’s pressing midfielder cut off the opportunity to progress through the centre and rushed him into playing the ball out to the right-wing — a less threatening position than a forward pass through the centre would’ve been.

This aggressive pressure on the receiver could leave the Sochaux defender open to getting dribbled past and left behind by an opposition player. However, in this low block phase, Sochaux have got lots of players positioned very close together, especially in the centre, in a horizontally and vertically compact shape. So, if the first defender was dribbled past, another defender wouldn’t be too far behind to pounce on the dribbler and prevent them from progressing any further. This is one key benefit of Sochaux’s tight, compact defensive shape.

As this passage of play moves on into figure 12, we see that as the ball made its way out to the right-wing from the centre, the next receiver was, again, quickly closed down by the nearest man — Sochaux’s left-winger. While a few opposition players made their way over to the wing to provide options to the receiver, they were both closely followed by Sochaux’s left-back and the two midfielders who were occupying the centre in figure 11. This leaves Sochaux with an overload and plenty of coverage for the pressing player if he is beaten with a dribble, again, providing a safety net for Les Lionceaux. As a result, the safest option here for the opposition is to send the ball backwards.

This passage of play shows how Sochaux’s defensive system in the low block phase can successfully set Sochaux up to protect the centre and force the opposition away from goal through some key principles like aggressively pressing the ball receiver with the nearest man and retaining a vertically and horizontally compact shape.

Figure 13 shows an example of Sochaux’s backline defending against an attacker who’s gotten past the midfield line. Here, we see the defenders backing off in a good, side-on body position which will help them to turn if needed while backtracking. Sochaux’s centre-backs are demonstrating excellent body positioning here while inviting the opposition dribbler to continue forward. While they drop off, Sochaux’s backline also gets more compact, with the full-backs moving centrally to close space between them and the centre-backs for the opposition to potentially exploit.

The full-backs also must be ready to move even further into the centre if required. The full-backs will typically move even further into the centre if a centre-back is forced into a defensive duel, to prevent space from being exploited in the backline.

While in previous examples, we’ve seen the centre-backs defending aggressively and stepping out to engage with attackers, here we see them acting differently which is because here, we see the defenders confronted with an attacker on the ball, facing towards goal, whereas in previous examples, we’ve seen them either dealing with an attacker off the ball or on the ball but facing away from goal. In those situations, the defenders can afford to be more aggressive but here, being aggressive could lead to the defender getting beaten by a dribbler, allowing the opposition to cut straight through the backline. So, in this instance, Daf’s defenders act slightly differently.

Instead of coming out to confront attackers, the defenders opt to back off for two key reasons. Firstly, they’re backing off to buy themselves more time to get compact and organised, and secondly, they’re backing off to try and force the attacker to show his hand first and ideally force a mistake, such as a heavy touch, which Sochaux can then capitalise on. In contrast, if the defender was more aggressive, they’d be forced to show their hand first by engaging in a duel that could result in the opposition attacker skipping past them or passing the ball around them.

As the passage of play moves on into figure 14, we see how Sochaux’s backline is now much more compact, which closes the space that the opposition have to play through. With space reducing for the opposition attacker to dribble into and Sochaux’s holding midfielders also closing in on the attacker from behind, the ball carrier is rushed into taking on a shot from a not very threatening position. This highlights how effective Sochaux’s calm and composed defending in this situation can be at turning a once-promising situation for the attacker into a far less promising situation.

The Sochaux centre-back ends up pulling off a block here but it’s worth noting that his body positioning for blocking the ball isn’t perfect and could result in the ball deflecting towards goal, rather than being fully blocked. Ideally, the defender would’ve been able to get in line with the ball here so his full-body were in place to block the ball. Even so, his block attempt was successful on this occasion. Sochaux have made the second-most blocks (2.77 per 90) of any team in Ligue 2 this season, highlighting that this is a fairly important part of their game which partly comes from their success at forcing opposition attackers into taking shots with defenders positioned in front of them, as we see here. Sochaux are good at denying the opposition clear shots at goal, which is a big reason for their impressive defensive record this season.

In possession

Sochaux’s success this season hasn’t just been because of their performances without the ball, it’s also partly due to their performances in possession. This section of analysis will focus on some of the more important aspects of Les Lionceaux’s tactics with the ball. Sochaux are among the most heavily possession-based sides in France’s second tier at present, having kept the third-highest average percentage of possession (55.2%) of any team in Ligue 2 this term. They’ve also played the fourth-most passes (411 per 90) of any Ligue 2 side.

Les Lionceaux aren’t a very aggressive team with the ball, however. They don’t play an outstanding number of progressive passes or make many dribbles and they don’t take a tonne of shots per 90 either. Daf’s men are very patient with the ball and are happy to wait for their opening when progressing upfield.

Sochaux don’t have a great target man up top; 166cm (5’5”) Aldo Kalulu usually starts at centre-forward for Les Lionceaux and he has got the third-worst aerial duel success rate (13.04%) of any centre-forward in France’s second-tier this season. So, Sochaux haven’t got a great chance of winning aerial duels resulting from long balls from the ‘keeper and while they could still opt to send the ball long to Kalulu to win the second ball, they generally prefer to build their attacks from the back via short passes.

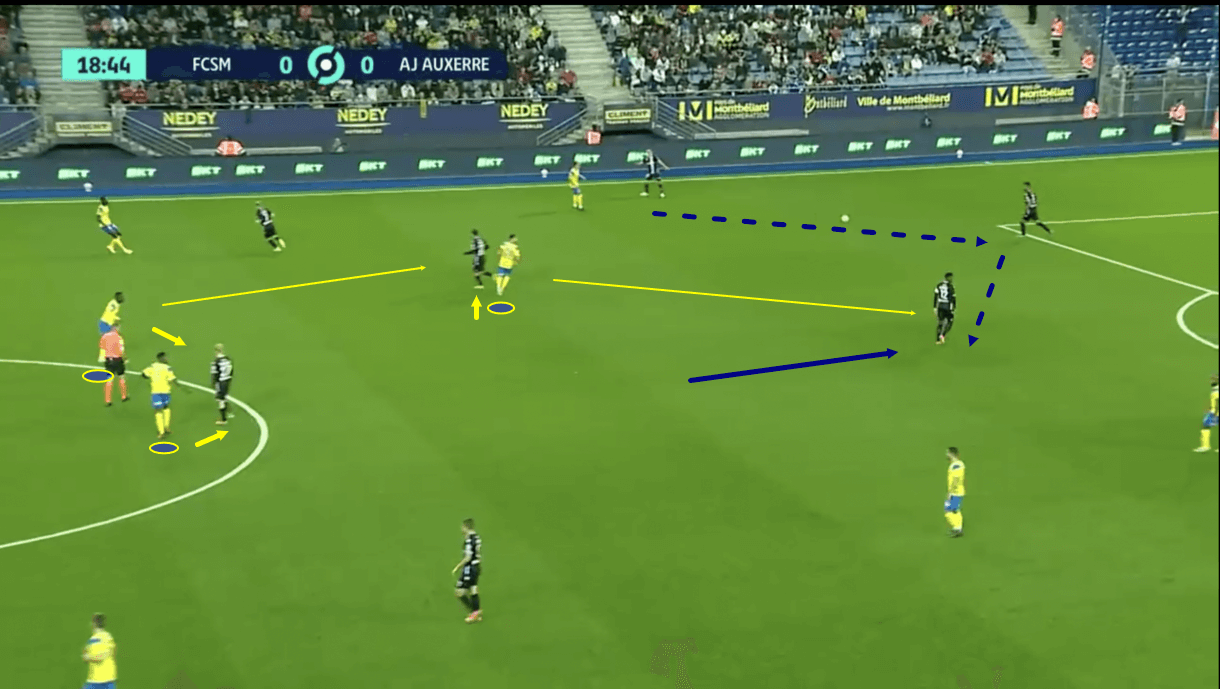

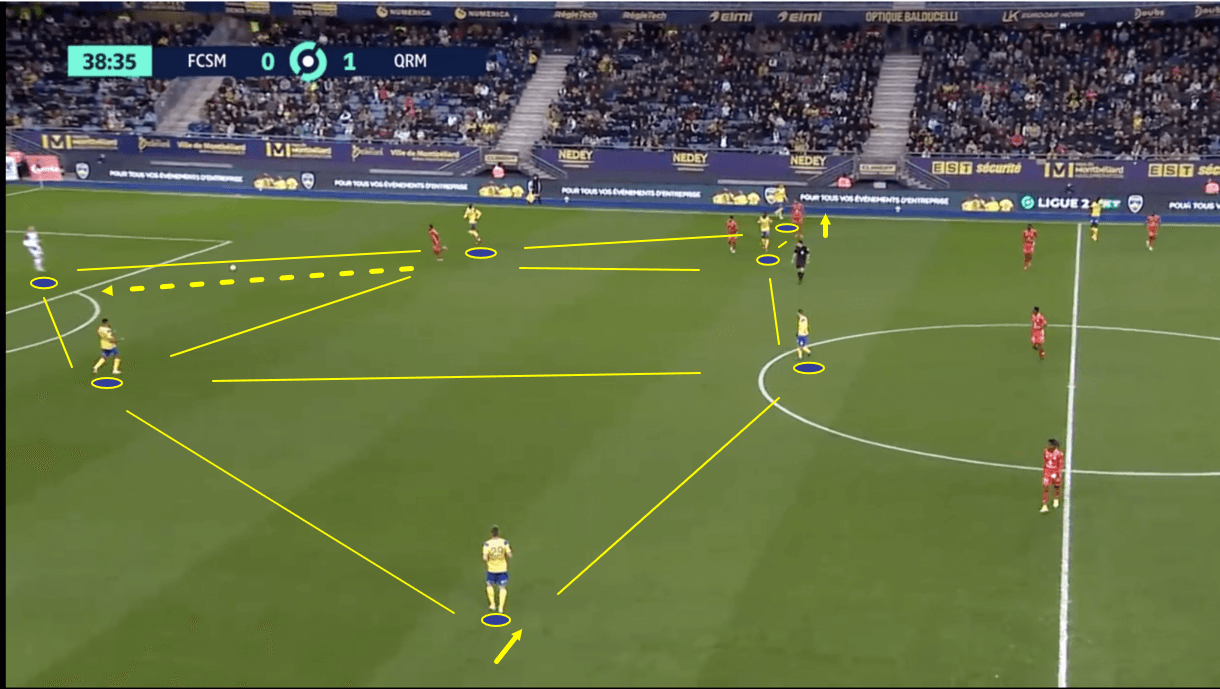

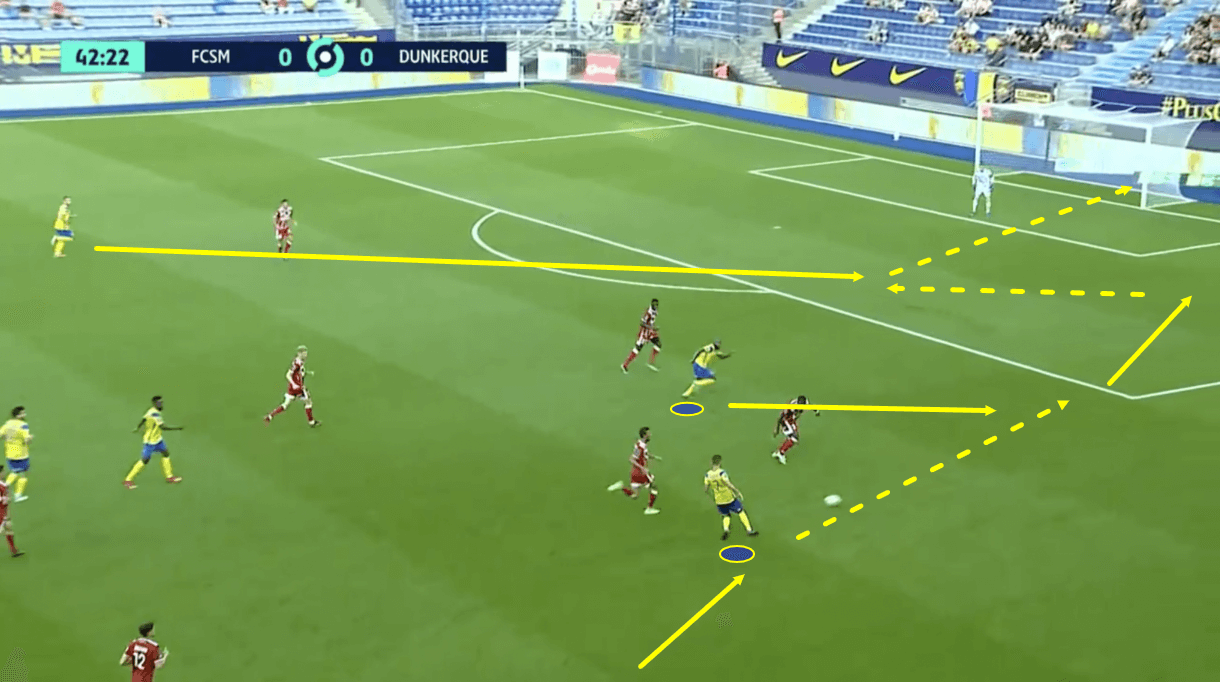

Figure 15 shows a typical example of Les Lionceaux’s offensive structure in the build-up phase. Their full-backs typically push up into the same line as the holding midfielders, resulting in a 2-4-3-1 shape forming. This can leave Sochaux’s wings open on the counter, which is another reason why their patient build-up play is so important and the fact that they’ve made the third-fewest ball losses of any Ligue 2 side this season highlights the success of their patient, careful play in possession.

As this 2-4-3-1 shape can leave the centre-backs vulnerable to pressure from two opposition forwards, Sochaux’s goalkeeper must also be available in the build-up to help his team play out from the back. In this example, while Sochaux’s left centre-back was being pressed and the opposition player pressing him was cutting off the passing lane across to his centre-back partner, the ‘keeper had come out to give him another option and as we can see, the centre-back happily took that option, deciding to play the ball back to the ‘keeper who could then relay it safely to the right centre-back. From here, the right centre-back could progress the ball upfield through the midfield for Sochaux.

This provides a great example of how Sochaux like to build their attacks. They don’t force the issue, aren’t particularly aggressive with the ball and don’t play with a particularly high tempo. They like to circulate the ball around the backline patiently while looking for an opening to safely progress upfield.

It’s also worth noting how, in addition to pushing up to form a four-man line with the two holding midfielders, Sochaux’s full-backs position themselves, in terms of width, according to the position of the ball. For example, here, with the ball on the left side of the pitch with the left centre-back, Sochaux’s left-back was positioned very wide, right at the touchline, while the right-back came into a narrower position when the ball was on the opposite wing, providing more of a presence in central midfield.

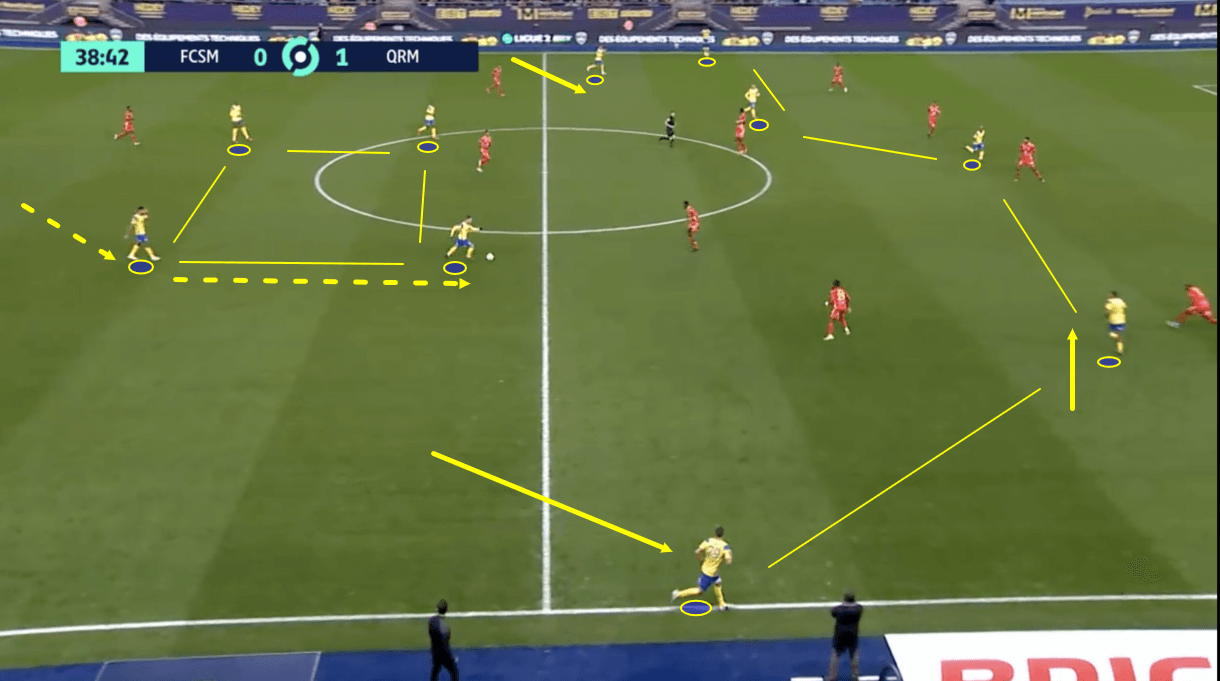

As the ball switched to the right side of the pitch in figure 16, we see how Sochaux’s right-back is now hugging the touchline while the left-back is moving more centrally. This is some subtle movement but it highlights the intricacies of Daf’s system in the early possession phases. As the right-back moves wider to provide the width and the left-back moves narrower, again, providing more of a presence in central midfield, Sochaux’s left-winger stays wide and the right-winger moves into the half-space. So, the wingers demonstrate contrasting movement with the full-backs.

The relationship between the wingers and full-backs is an important part of Sochaux’s system in possession. If the winger is staying wide, then the full-back must be positioned more centrally in the inside channel and vice versa. This helps to create natural passing angles within Sochaux’s offensive shape.

The base of Les Lionceaux’s shape in possession turns into a 2-2 box shape as they move into the ball progression phase, however, with the full-back coming narrower, it becomes more of a 2-3 shape while the wider full-back joins the forward line, creating a natural front five for Sochaux with the wingers, ‘10’ and centre-forward. Daf wants three men centrally to create this midfield three and it’ll generally be formed with the two holding midfielders and one of the full-backs. The Senegalese manager also wants width from one full-back and one winger, while the ‘10’ and other winger provide a presence in the half-spaces. Centre-forward Kalulu, then, will typically be positioned centrally, looking to make runs in behind the opposition’s backline. Again, Sochaux won’t force the issue as they move into the ball progression phase. They remain patient with their play.

It’s worth noting that though we didn’t see an example of this in the previous passage of play, it’s common to see Sochaux’s holding midfield duo stagger their positions, rather than standing right beside each other during build-up and ball progression. This helps to create more passing angles for Sochaux and makes these players more difficult to mark for the opposition than if they were standing right beside each other in an orderly line. Figure 17 shows an example where Sochaux’s left holding midfielder has dropped deep, staggering with the right holding midfielder who’s staying in his initial position. This also creates space for Sochaux’s ‘10’ to drop deep into the right central midfield position, forming the triangle we see above. Meanwhile, Les Lionceaux’s two full-backs also advance into higher positions. This creates something of a 2-3-2-3 shape for Daf’s side and it’s another common shape to see them deploy in the early possession phases.

By forming a front five with one full-back, the wingers, ‘10’ and centre-forward, Sochaux overload an opposition back four and create 1v1s against an opposition back five. It’s a major part of Daf’s tactics in possession to take advantage of this overload, particularly in wider areas that place great importance on the chemistry between the wingers and full-backs. It’s also common to see the centre-forward make runs into wider channels, as was the case in figure 18, to exploit the overload and break into the box. While Kalulu isn’t a very big striker, he is a quick and nimble one. While Daf’s currently using him as a centre-forward, he has primarily played as a winger throughout his career and is very comfortable being played into positions like the one we see him moving into in the image above.

As play moves on from here, we see Kalulu get onto the end of this through ball before cutting the ball back into the box for the ‘10’, who arrives late from the left half-space, to slot the ball away tidily.

Sochaux can capitalise on through balls in behind the backline that exploit Kalulu’s pace and they also like to use low cut-back crosses heavily in the chance creation phase. Plenty of their goals this season have come via these two situations. They’ve also scored some goals via more traditional crosses but as Kalulu doesn’t offer a great physical presence, these types of crosses aren’t extremely effective a lot of the time.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis, I feel that Daf’s effective defensive system has been the key to Sochaux’s successful start to the season. Although the system isn’t without its faults and can be exploited with just one individual error, that hasn’t happened very often this term and, in general, Les Lionceaux have been a very organised side without the ball, which is a testament to Daf’s coaching quality.

Sochaux also play some effective football with the ball. They are a heavily possession-based side with a relatively low tempo who like to take their time when building out from the back. They’re happy to wait for their opening before progressing upfield, rather than trying to force the issue. This sees them play a relatively low amount of progressive passes but they also don’t turn the ball over very often in build-up and ball progression, which is very positive for Daf and his team as they do have some vulnerability out wide on the counter due to the offensive shape that we’ve analysed.

Again, whether or not Daf can guide his team back to Ligue 1 remains to be seen but it’s clear that his tactics have played a key role in his side’s impressive start to the campaign, which is worthy of the praise that ex-Sochaux president Plessis bestowed on him.

Comments