What Is Counterattack In Football?

Counterattacks are a very useful tool to strike opponents when they are at their most unbalanced.

UEFA Champions League winners Real Madrid are a testament to that.

By positioning players strategically when out of possession, teams that then quickly turn defence into an attack can be lethal.

Counterattacks at the highest level involve far more planned actions than in previous eras.

This tactical theory analyses the principles of the modern counterattack.

This analysis focuses on goals scored from counterattacks when teams have deliberately positioned players ahead of the ball during the defensive phase.

This tactical analysis will use goals scored recently by John Herdman’s Toronto FC in the MLS to describe this tactical theory.

Suggestions on how coaches can implement counterattacking tactics are also included.

Countering Behind High Full-Backs

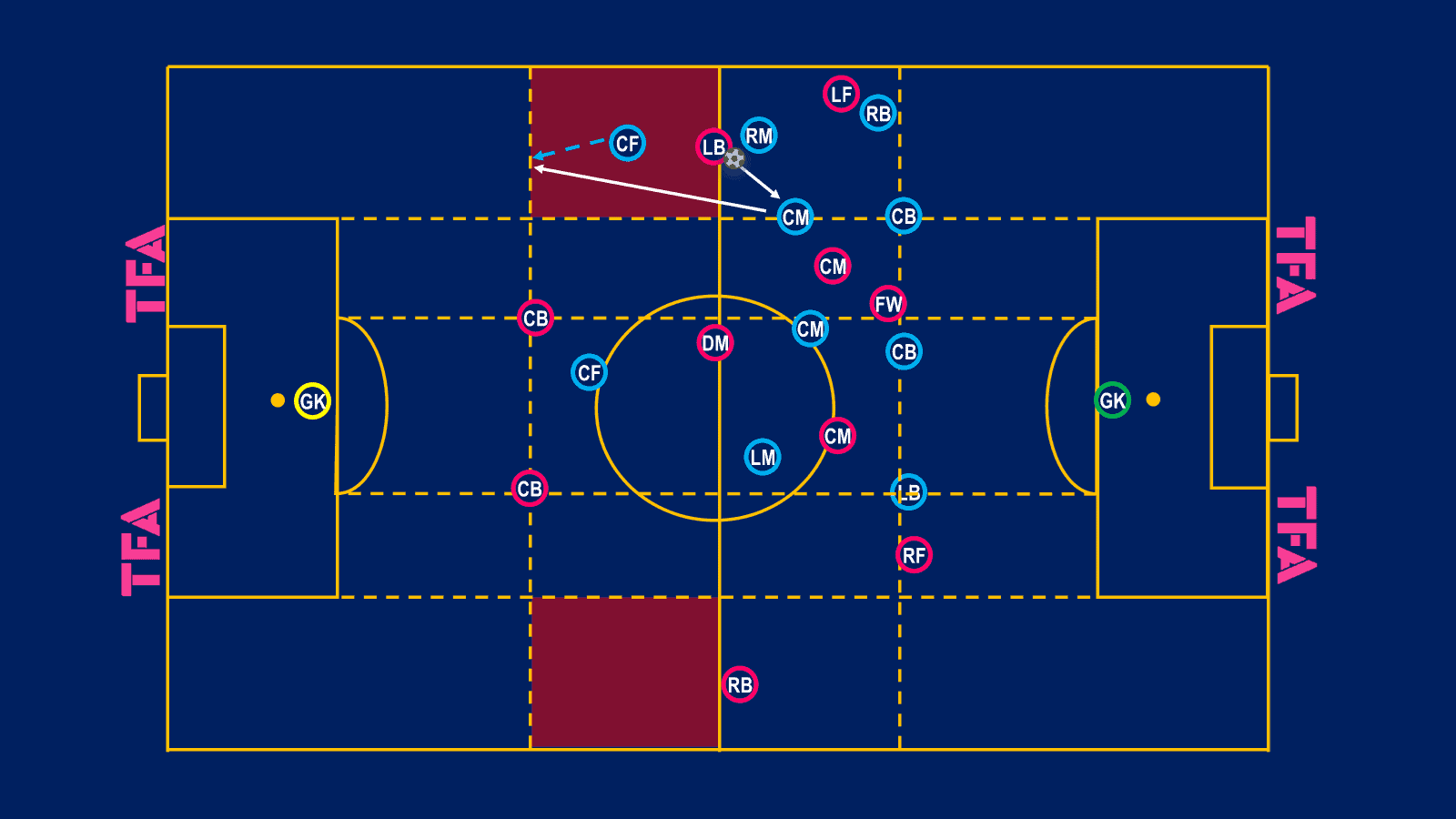

The above tactical diagram shows the attacking team (pink) set up in a 4-3-3 mid-block against the blue team’s defensive 4-4-2 mid-block.

The defending team has eight players behind the ball, in two lines of four, defending the width of the pitch.

Two players, in this case, the central forwards, stay ahead of the ball, with one forward overloading the ball side of the pitch and occupying the space behind the high full-back.

This forward could also be the ball-side winger in a 4-3-3 formation.

The backline must remain high enough, without dropping off too deep, to be in a position to play the ball into the red area quickly on attacking transitions.

The further the defensive and midfield units are from this zone, the longer the ball will take to travel there, giving the pink team more time to react.

The ball-far centre-forward’s positioning is also essential here.

By remaining relatively central, he prevents the ball-near centre-back (who may also be trying to be an option for a pass) from shifting over to cover the now wide forward.

By not being right up against the centre-backs, the central forward is also an option to receive the first pass.

In this scenario, when the ball is won on a transition, it is important to play forward at the earliest opportunity, using the space behind the high full-backs, and have supporting players run forward quickly.

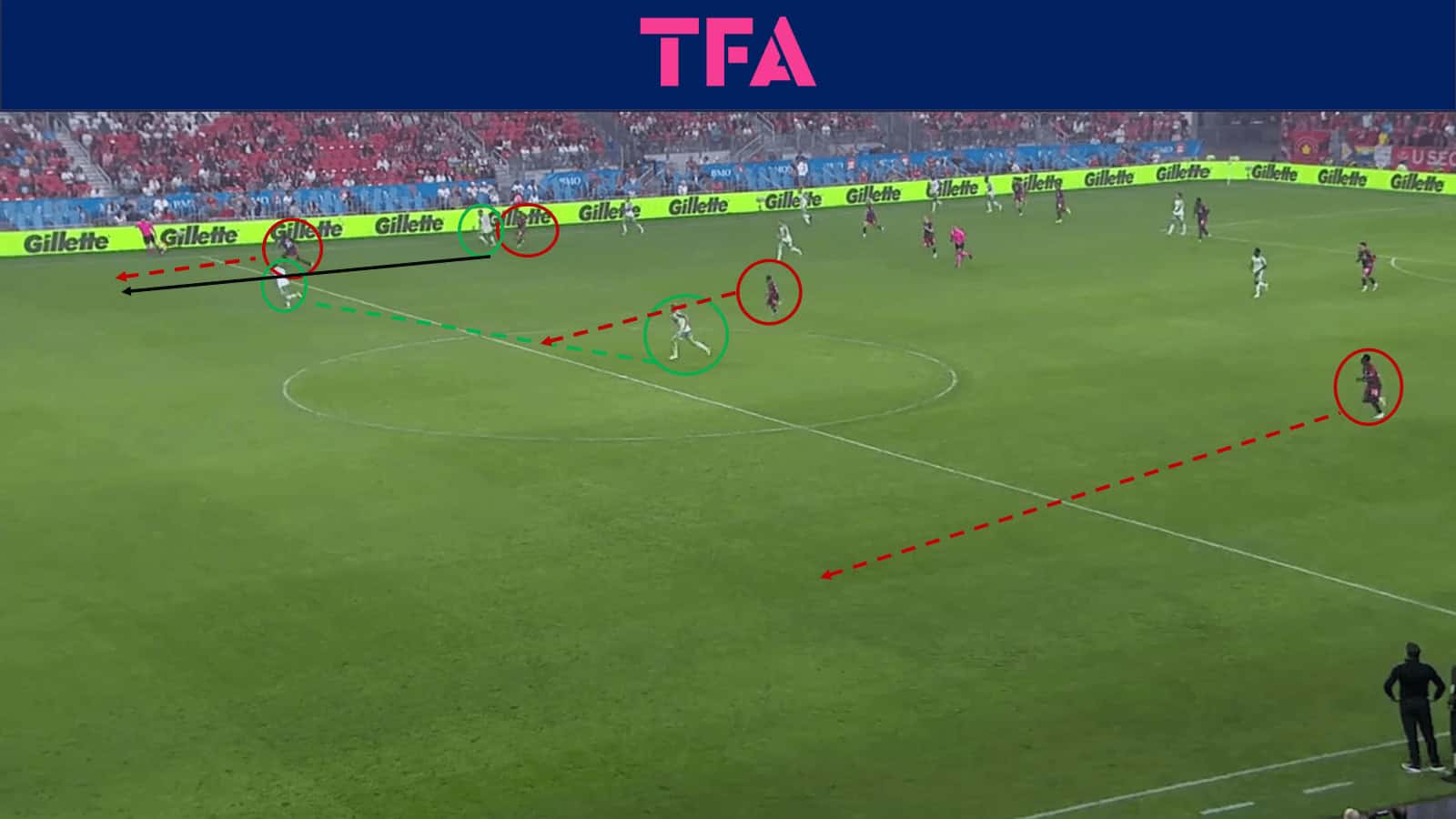

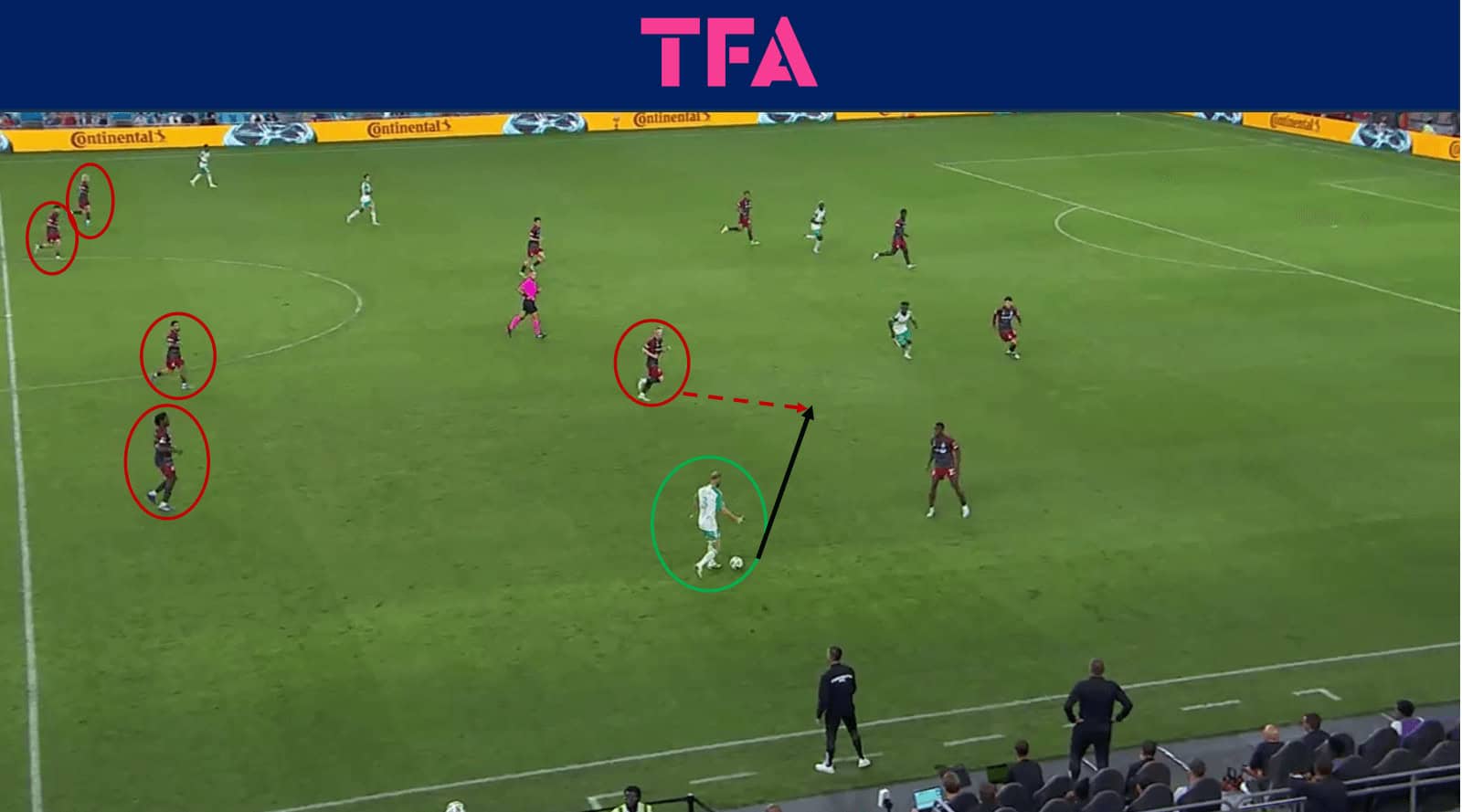

This goal from Toronto in their match against Austin was scored in a similar fashion: Toronto exploited the space left by Austin’s high full-backs.

The image shows one forward in the wide area, on the ball side, behind the Austin left-back.

The more central forward, former Seria A star Lorenzo Insigne, is in the middle of the pitch, about 10 yards from the nearest opposition player, making him an option to receive the first pass.

On the ball-far side of the pitch, Toronto’s wing-back, Richie Laryae, is also high, ready to sprint into the space behind Austin’s right-back once Toronto win the ball.

When the forward receives the ball, his first thought is to dribble forward at speed before then running directly at the defender — pinning him in place.

In the initial phase of the counterattack, the three furthest forward players occupy three different vertical zones of the pitch.

By providing (relative) width, the defenders are unable to cover and react to all three players’ movements.

The pace at which the ball carrier dribbles forward and the speed of the supporting runs make it very hard for recovering players to help their centre-backs.

At this point, when the attack is reaching the box, the central forward makes an angled run across the dribbling player.

This run is designed to drag the most central and covering defender, allowing the ball carrier to continue his run inside and open up a passing lane into the left wing-back.

Austin’s recovering midfielder does very well to get close to the ball and even challenges the dribbling player.

However, the speed of the attack means the midfielder can only make a desperate challenge just outside the box.

Despite getting a touch on the ball, Toronto, by attacking in numbers, have a player positioned to get on the end of the deflected ball who goes on to volley into the goal.

Four Toronto players are in their opponent’s box when the ball hits the net.

Positioning Players High

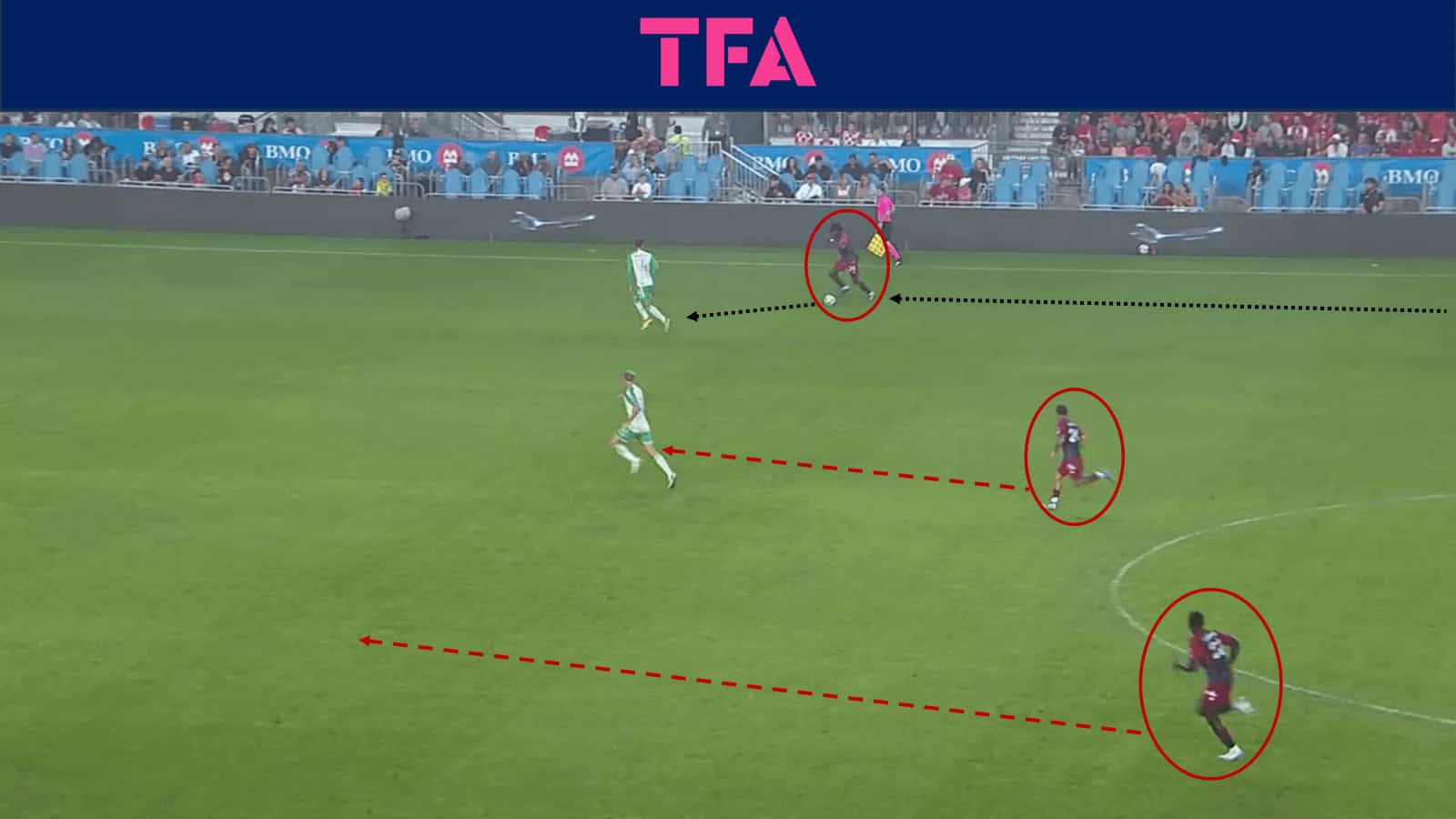

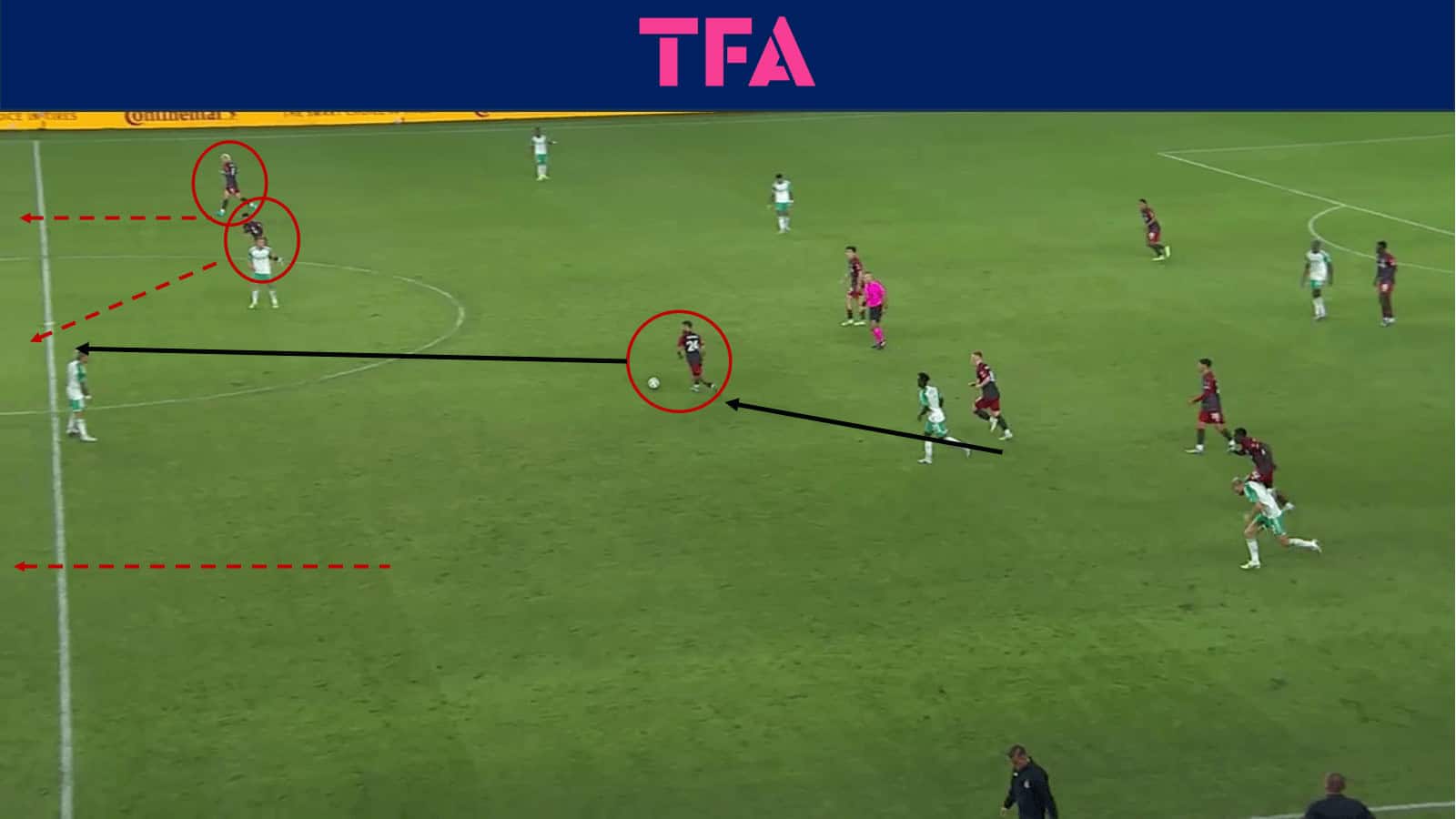

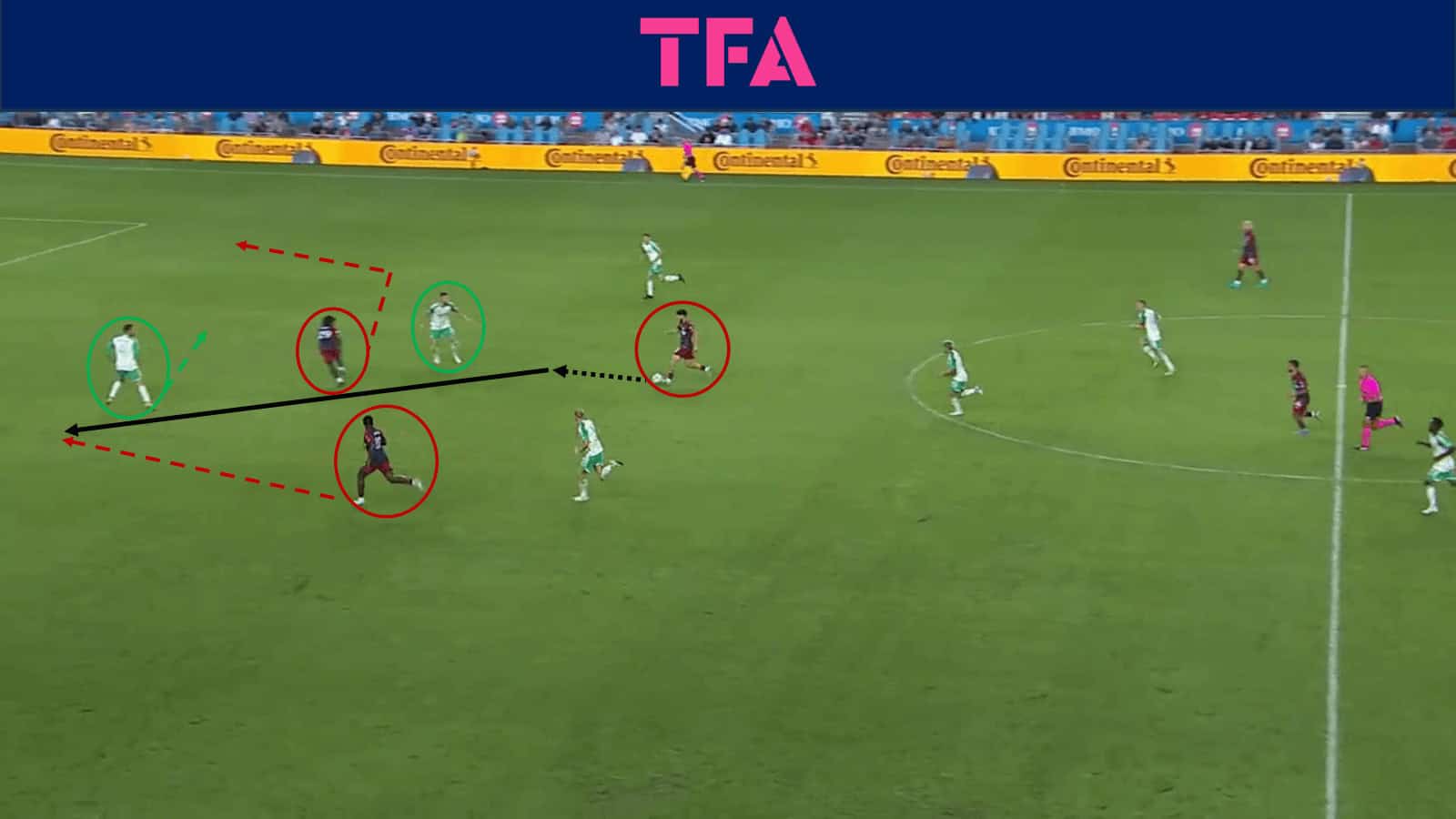

In this example, from the same match, Austin’s former Ligue 1 star, Mikkel Desler, is in possession of the ball around 15 yards into Toronto’s half.

On this occasion, Toronto left four players high ahead of the ball and trusted their (now) back four and two holding midfielders to defend against the Austin attack.

Not only were Toronto’s front four in high positions, but they were also strategically placed across the width of the pitch.

By being positioned in different vertical lines and being placed in the zone between the opposition’s backline and midfield, they made themselves very hard to mark.

If Austin’s backline was to push up and get tight to each player, not only would this make it harder for them to keep the ball, any loss of possession could result in Toronto playing in behind them straight away.

Desler’s pass into his forward is intercepted.

Upon winning the ball, Toronto immediately play it forward into Insigne who is completely unopposed.

Insigne then turns and drives, forcing Austin to retreat, before playing a pass between two Austin players for his teammate, who has made an angled run, to sprint onto.

The receiving player then drives at the nearest centre-back to pin him whilst his teammate, Deandre Kerr, makes another angled run in behind.

This run acts as a decoy to drag the covering defender away and give space for his teammate, Richie Laryea, on the left to run into.

Laryea receives the through ball and drives into the box before providing a cutback for Kerr to score.

Counterattacking Pass Sequence

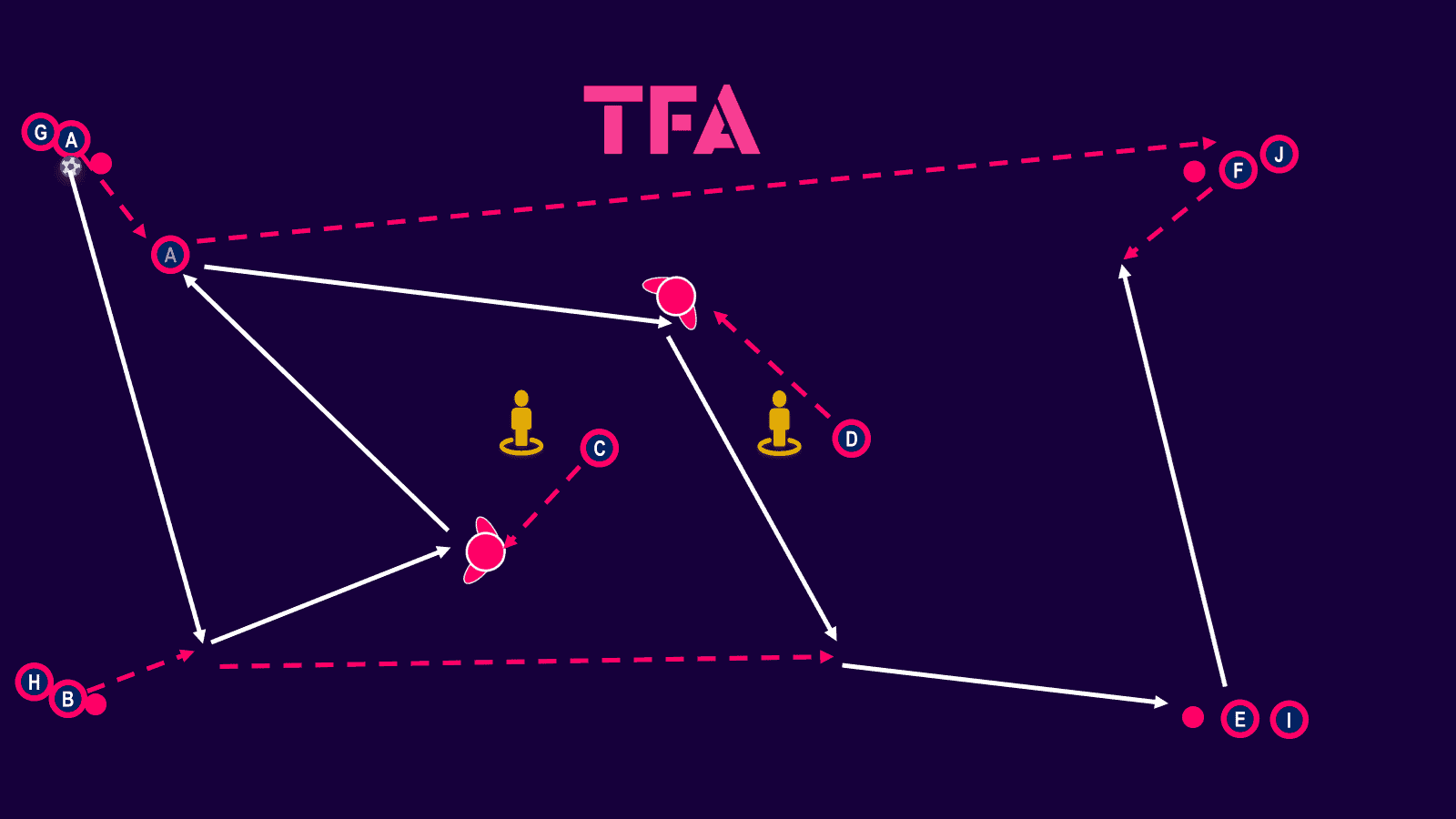

This unopposed passing exercise is designed to both prepare the players for the physical demands of a counterattacking session as well as to embed the principle of playing and running forward as quickly as possible.

It involves target players, who represent players who are left ahead of the ball for the supporting players to combine with.

It also includes angled runs to mimic the runs made to drag away defenders.

The size can be adjusted depending on the level and age of the players working with, but it can be as long as half a pitch.

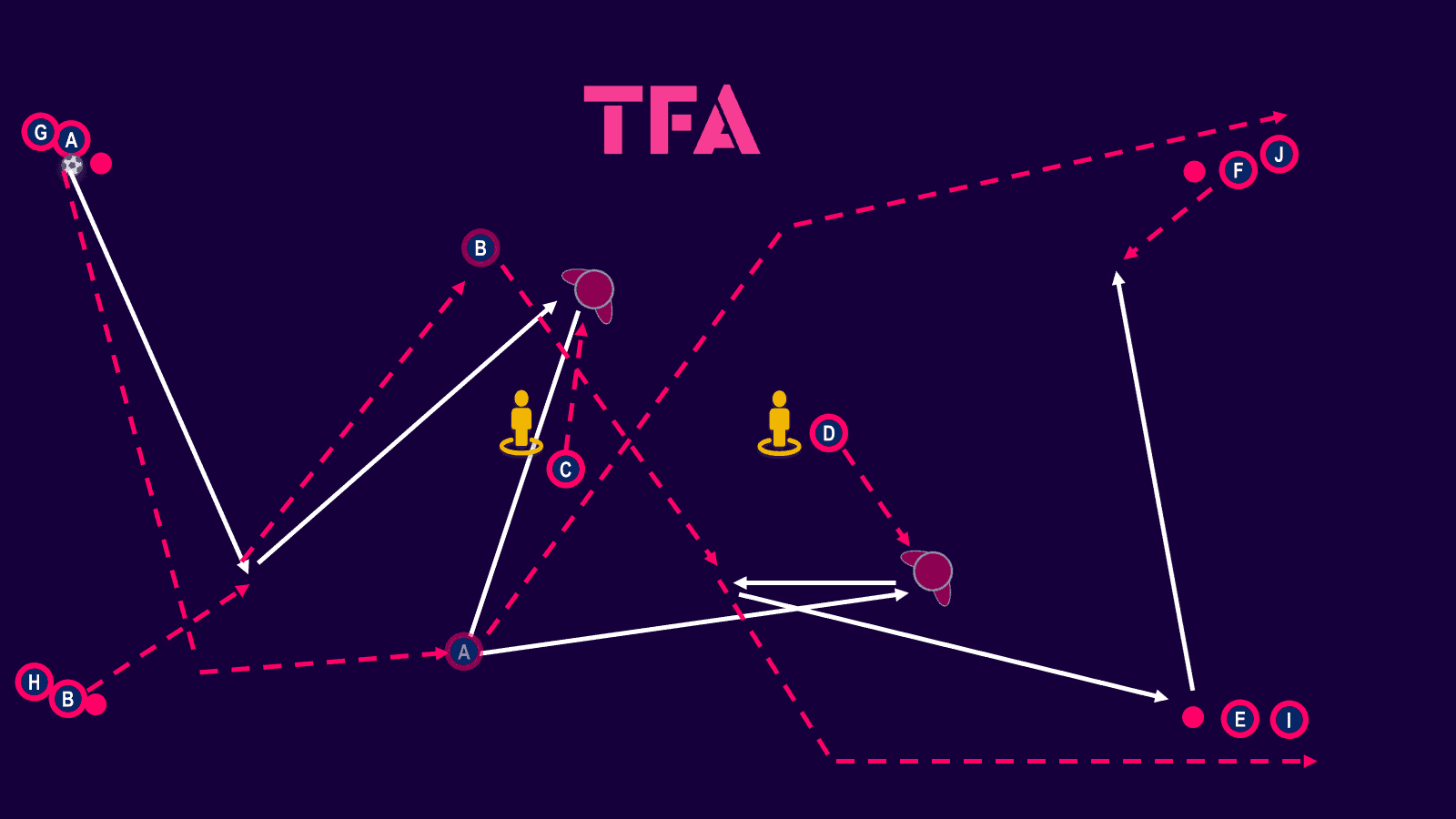

The exercise begins with player ‘A’ playing a slow, angled pass for ‘B’ to run onto.

The weight of the pass should allow the next pass into the ‘forward’ to be played firmly.

‘B’ then finds ‘C’, which represents a forward and has moved from behind the mannequin, before ‘C’ sets it back where it came from to ‘A’.

‘A’ plays a firm pass into the second forward, who takes a touch with the inside of their back foot before quickly, with their opposite foot, switching to ‘B’.

Players ‘A’ and ‘B’ then sprint to and join the opposite lines after playing their final passes with the forwards remaining in their positions.

As shown above, the exercise then progresses for ‘A’ and ‘B’ to make two cross-over runs.

For the drill to mimic a realistic counterattack situation, players should be encouraged to complete it a full, match speed.

The drill can also be adapted into a shooting drill.

The sequence begins at the goal end, before repeating on the way back but finishing with a strike at goal.

Mid-block to Counterattack Exercise

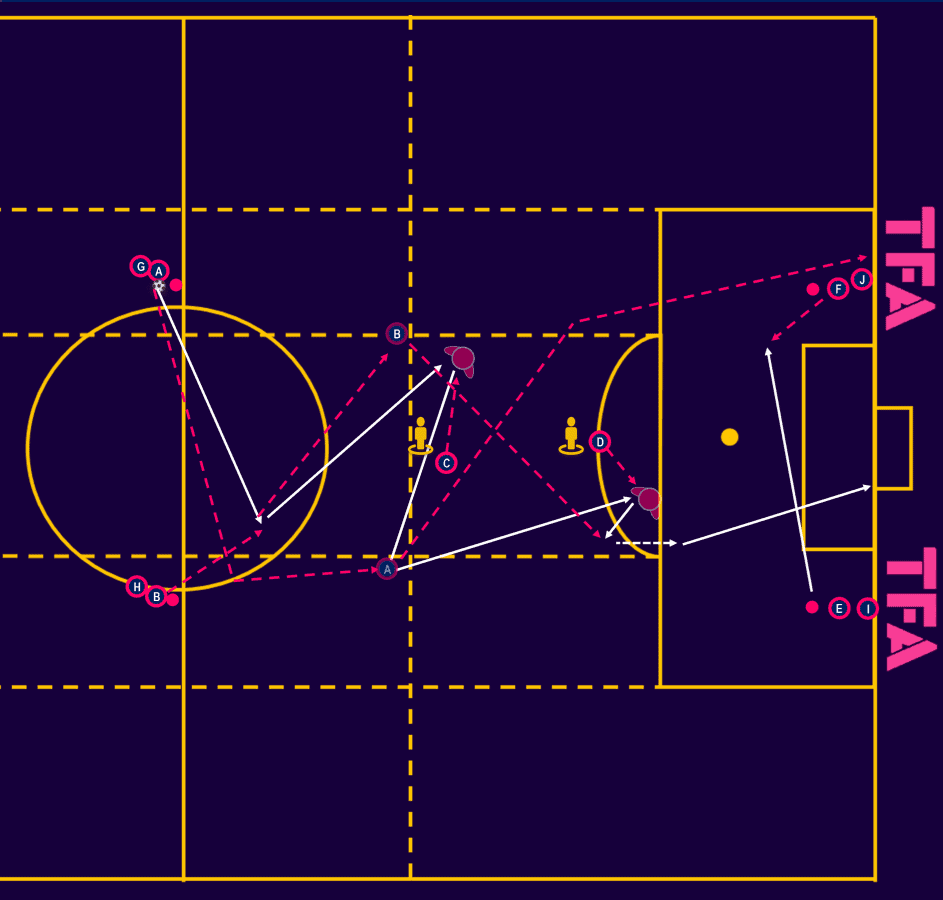

This practice is designed to simulate teams targeting the area behind their opposition’s high full-backs.

The exercise begins with the opposition, shown as pink, moving the ball across their back four with those players in fixed positions and the blue team forwards only acting as shadow defenders.

The back four aims to find one of their midfielders in the red zone, who will then score one of three mini-goals.

One of the blue team forwards should occupy the space behind the full-back (shown in image) on whatever side of the pitch the attack is being developed on.

This requires the four blue midfielders to cover the width of the pitch as if in a mid-block and against an offensive overload.

Once possession is turned over, the blue team’s aim is to counterattack to the big goal.

The pink teams recovering full-backs must run forward to the cone (or pole) on the sideline before being able to participate in the defensive phase.

This incentivises the blue team to play quickly before these full-backs can influence the attack.

Initially, the blue team’s midfield can attack, but the pink midfielders must remain in their midfield zone.

This can allow coaches to work on and embed pre-planned movements before adding the complication of recovering midfield players.

The immediate aim should be to play forward and find the forward in the space behind the full-back.

Regardless of the movements, coaches should demand that midfielders flood forward in support of the attack and make angled runs to drag defenders and create space for others.

When dribbling with the ball, the attacking player should look to pin one centre-back.

Conclusion

Counterattacks have long been part of the game, and many elite coaches have used them as their main source of attack.

What has changed in recent years is the amount of pre-planned positioning to set up the conditions for a counterattack and the pre-planned movements based on the opposition’s set-up.

Coaches that are able to understand and implement these concepts create a great advantage for their teams.

Comments