Overloads have been and always will be an extremely powerful tool to tactically gain an advantage over the opposition. In simple terms, having an extra player over the opposition team in a certain area means there is someone free to receive the ball with time and space. Finding that player allows them to perform any action without disruption, meaning they can perform it to the best of their abilities.

In relation to set plays, being able to create overloads in the 18-yard box means that someone will be free to receive the cross and have a shot on goal from close range without the opposition interfering, leading to a consistent method of creating high-quality chances. With the chances coming from dead balls, the provider also has no interruption when attempting the cross, allowing them to perform the cross to their peak level and with the ability to replicate the scenarios frequently during training sessions.

In this tactical analysis, we will look into the tactics behind different methods of creating overloads, with an in-depth analysis of how each method can be attempted and the positives/risks that come along with them. This set-piece analysis will look at why the different variations can all be effective and hopefully inspire teams to develop their own corner routines incorporating overloads due to their ability to provide teams with unopposed shots around the six-yard box.

Numerical superiority through positioning

The first and most simple method in which overloads can be created from set plays is through the starting positions of attackers in relation to defences. Attackers can group up in certain areas of the 18-yard box to overwhelm defenders by outnumbering them. This is most common in areas around the penalty spot due to the frequent use of zonal defensive setups around the six-yard box by most teams.

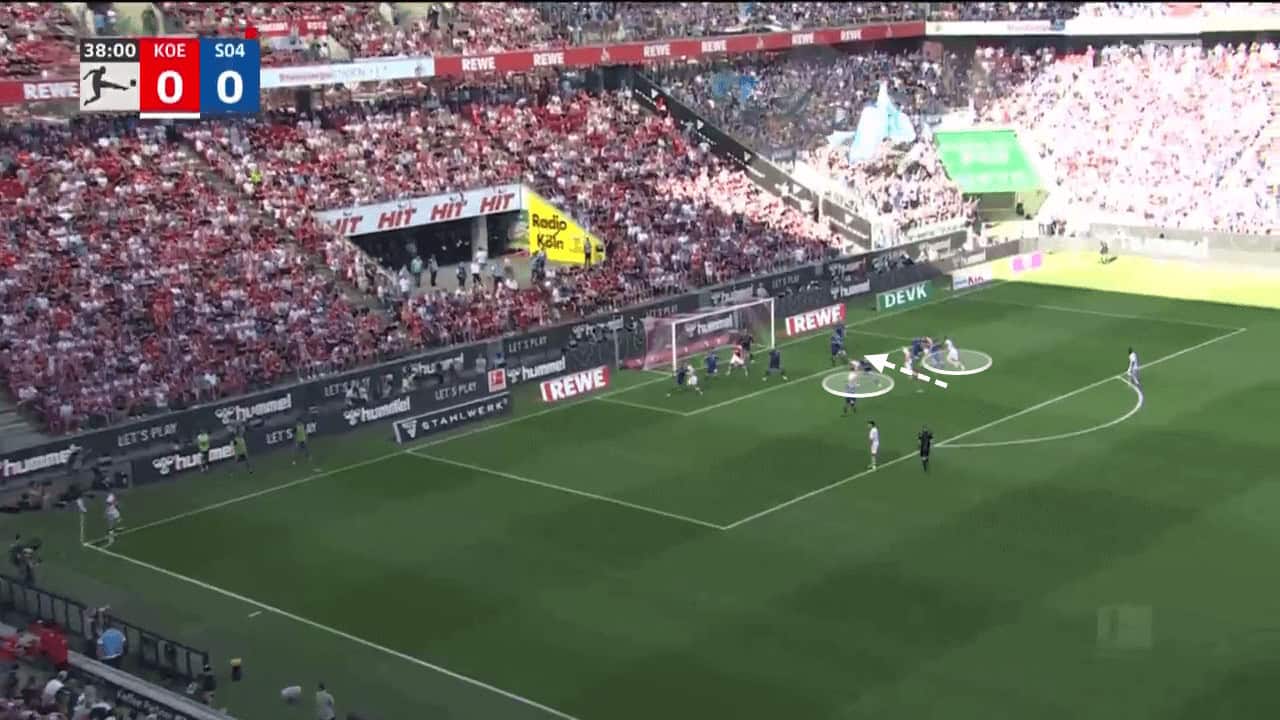

We can see in the example below, FC Koln had a clear 3v2 around the penalty spot where the two Schalke defenders are unable to track the three different runs into the six-yard box.

Once the corner is taken, the three attackers all attack different areas inside the six-yard box, splitting their runs. With the Koln players all running into different areas, it becomes impossible for the two Schalke defenders to track each run. This results in one attacker being unmarked, and able to attack the six-yard box unopposed. Although there are zonal defenders positioned around the six-yard box, the extra distance which the free Koln attacker has to attack the ball with gives him an advantage in the aerial duel.

A slightly alternate method of creating overloads is by targeting deeper areas inside the 18-yard box. Receiving the ball further away from goal allows the attackers additional time to control the ball.

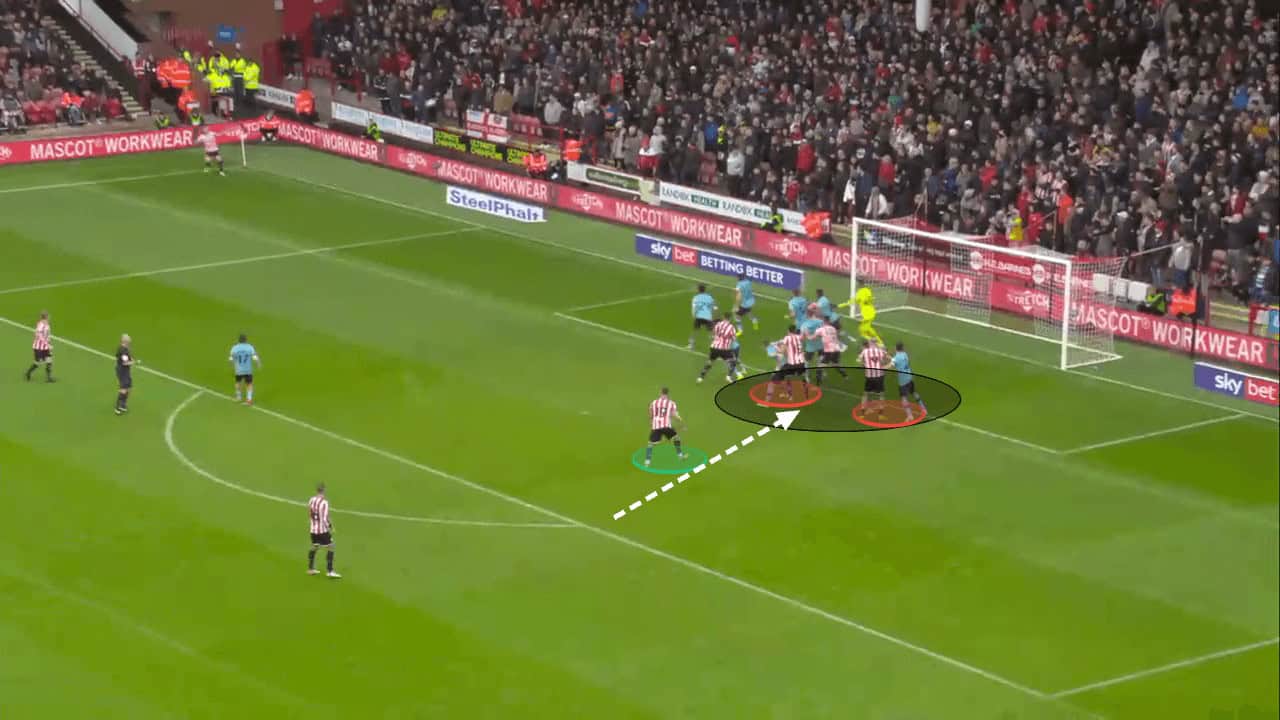

In the image below, we can see Brentford using three players around the back of the six-yard box, whilst only two defenders are responsible for that area. Whilst the ball is crossed into that area, the Brentford attacker is able to control the ball and the Liverpool defenders are hesitant when pressing the ball, as they are wary of committing to the duel and leaving the third man completely free. Due to the hesitation of the defence, Wissa is able to take the shot from around eight yards with his teammates’ dangerous positioning being enough to give him the separation needed to execute the strike.

Immobilising the opponents

One way in which it is possible to effectively make the most of the extra man is through the use of screens. The above examples have shown scenarios in which attackers had space due to defenders following the decoys, leaving the target player free to attack the ball. However, that method may not always work effectively if the defenders pick the right player to mark. The decoys then become irrelevant as the cross is not heading towards them and they’ve let the target player be marked by a defender.

In order to ensure that the designated target player will always be the free man, it is important to “immobilise” the remaining defenders. In the example below, inside the target area, there is a 2v1. Immobilising players means that you prevent them from moving as normal, meaning they won’t be able to attack the ball or change the person they are marking as they become rooted in one place. With this method, you can ensure that the decoy attackers are tasked with preventing the defenders from going towards the ball, whilst the target player is completely safe from defensive pressure while he lines up his run towards the ball.

Screens are the only legal way of completely preventing a player from moving freely and forcing them to stay in one spot, or at least preventing them from moving in the direction of the ball. In the example below, we can see the Monaco attackers with an overload and so one player provides a blindside screen whilst the other player in the target area is able to then attack the ball freely.

Movement to create overloads

The final way in which overloads can be utilised effectively is through the timing of the attacking movement as the corner is taken. Usually, when a team has a clear overload, the defensive side will communicate with each other to solve the issues and gain numerical equality. However, a smart way of deterring teams from matching up is through the late arrivals of individuals into target areas, meaning that the overload is there but only becomes apparent as the corner is about to be taken. The defensive side has limited time to solve the issues when the ball is travelling, and so with this method, the overload is extremely difficult to combat.

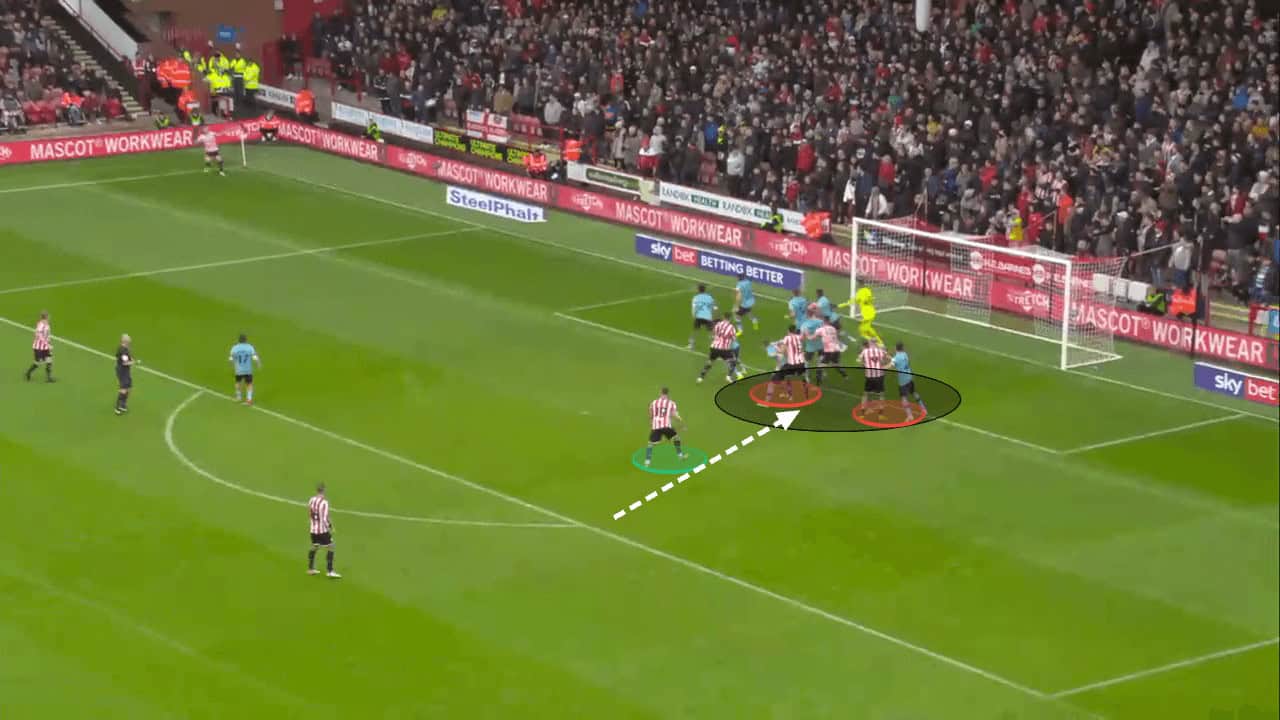

As seen in the image below, Sheffield United have a 2v2 on the far side of the six-yard box. With no clear advantage, Burnley feel as though the situation is under control, with the defenders trying to prevent the attackers from moving towards the ball, rather than attempting to clear the cross. The two defenders feel they have control, and are happy to let the ball run across the box and out for a throw. As the cross comes in, a run from deep can be seen, with the player being able to arrive in the target area unmarked. The two Burnley defenders aren’t going for the ball, so the free Sheffield United attacker is able to attack the corner with no obstacles and a run-up to get extra power on the headed effort.

A slight alternative to arrivals from deep is the arrival in a target area whilst the corner is being taken, made by multiple attackers. In the example below, Tottenham Hotspur are defending the near side of the six-yard box zonally with one player. As soon as the corner taker begins his run-up, it is the trigger for two Brentford attackers to create an overload at the near side of the six-yard box.

As described earlier, the late arrival into a target area doesn’t give defenders enough time to readjust their positions and so are left underloaded. With the 2v1 being clear in the image below, one attacker is tasked with immobilising the only defender present, which leaves the spare man to freely attack the ball from a dangerous area.

Use of Underloads

Whilst overloads are common in tactical preparations during open play, a common principle of attacking play is ‘overloading to isolate‘. Being able to drag a defensive set-up away from the real target, who then has fewer obstacles in his way, is a common method of chance creation from open play and can also be applied to set plays. Leaving attackers isolated, meaning to be 1v1 inside large spaces, usually allows attackers to gain the advantage in one of two main ways.

Firstly, having only one defender means there is numerical equality, which leaves the only advantage possible to be made through physical qualities. For example, leaving two players in an area with one clearly better than the other aerially can allow them to easily win the aerial duel, so no matter how poor the cross may be, they should always be more likely to make the first contact on a cross.

The other way in which someone isolated can take advantage of the extra space they’re in is through their mobility to find free spaces inside the target area through their quick movement and agility to weave away from their marker.

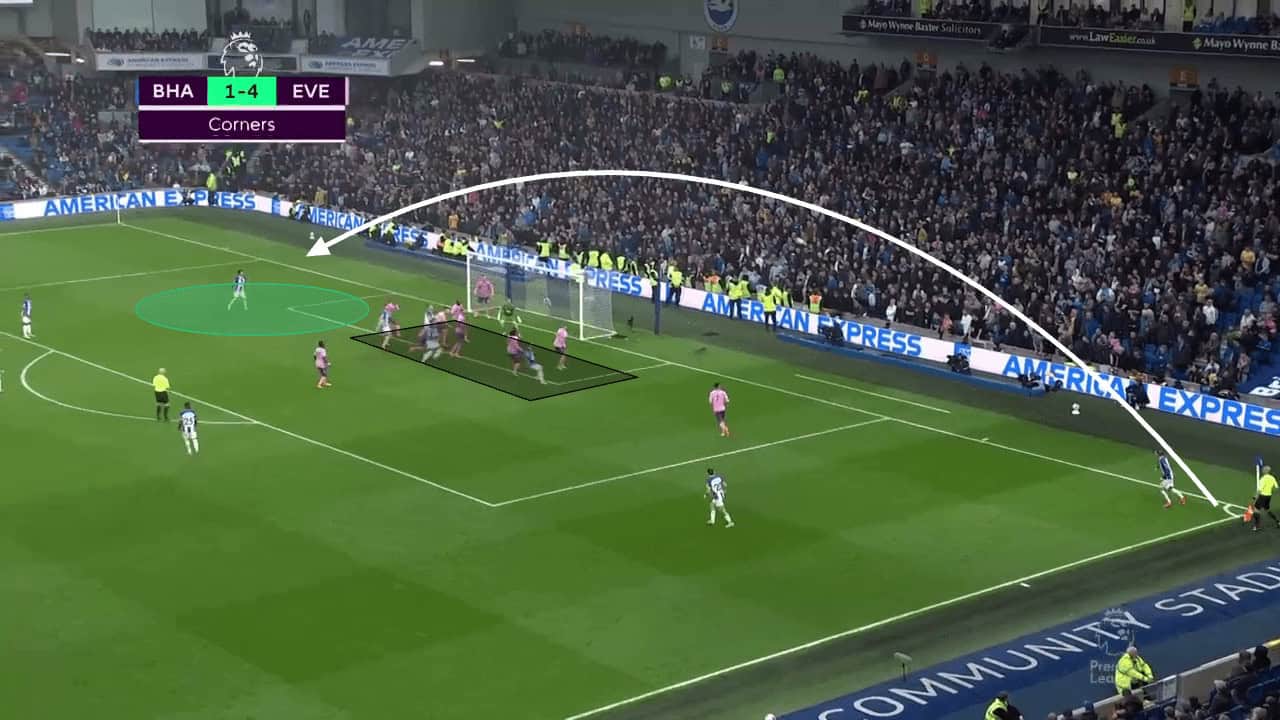

This can be clearly seen through the example below in which Brighton heavily crowds the near side of the six-yard box. This preoccupies the West Ham defence, leaving a 1v1 inside the back half of the six-yard box. As the ball is crossed in, the free attacker is able to lose his marker through his movement and gain the separation required to redirect the ball into the back of the net when it arrives inside the target area. Of course, there is a lot to be done by the other Brighton attackers, in order to make sure the ball arrives inside the target area. However, once it is successfully done, it usually leads to high-quality chances being created at the back post which are harder to miss than score.

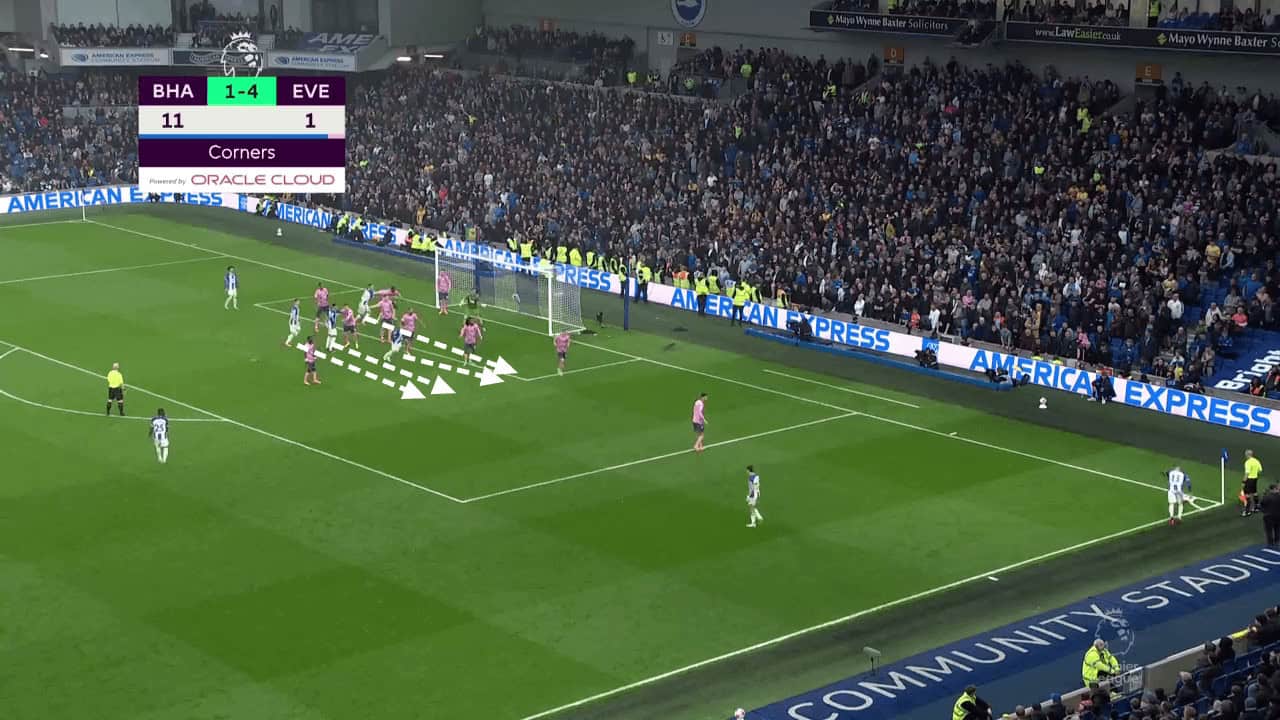

A mixture of the methods mentioned in this piece can be combined together. For example, Brighton can be pictured below purposefully overloading the near side of the six-yard box. Their runs are made early in order to give the Everton defenders time to track the runners which then makes them leave the zonal roles they started in.

As they all track the decoy runners, Mitoma can be seen at the back post, isolated by the six-yard box. The overload at the front side of the box is a large cause for concern, which then provides Mitoma with extra time to either control the ball or strike it towards goal. With the space he is in, he is able to perform his action without disruption, giving himself the highest chance of success.

Conclusion

This tactical analysis has described the multiple ways in which overloads and underloads can be formed and the many benefits each different style has. While the attempts which are closer to goal obviously are more likely to result in goals thanks to screens, overloads provide an equal alternative, where players may be slightly further from the goal but are completely unmarked with the ability to attack the ball and have a free shot from just outside the six-yard box.

The use of overloads and screens gives the best of both worlds, where a player is able to arrive inside a dangerous position close to goal without any markers. Being able to combine the two can potentially give teams the chance to consistently attack crosses in dangerous positions with no defensive presence in the target areas wherever they may be.

Comments