Who Is Paolo Vanoli?

Though he’s only in his second first-team managerial role, Venezia boss Paolo Vanoli is no newcomer to coaching.

The 51-year-old Serie B manager is a former Italy youth coach and assistant manager to the senior Italian national team, as well as having been Antonio Conte’s technical coach during his tenures at EPL giants Chelsea (beginning in 2017) and Serie A giants Internazionale (from 2019-2021), respectively.

He was part of an FA Cup-winning backroom team with Chelsea, as well as a Serie A-winning Inter side in 2020/21, who also managed to finish as runner-up in the UEFA Europa League that season.

After taking on his first manager role with Spartak Moscow in 2021/22 — guiding them to Russian Cup glory — Vanoli was called upon to take charge of floundering Venezia in Serie B, with the newly-relegated side having a disastrous start to the 2022/23 campaign which saw them in the relegation zone of the second-tier at the time Conte’s former assistant arrived.

Vanoli oversaw a significant turn in fortunes last season when he took over, ultimately guiding his team to an eighth-place finish — still below where I Leoni Alati would like to be in the second tier, but a respectable finish given the context of their awful start to the campaign.

Venezia’s upward trajectory has continued under Vanoli in 2023/24.

Now, at the time of writing, which is just before the midway point of the season, they sit second on the table, just two points off Parma, threatening to be in all of the right conversations come the business end of the term should things continue progressing in the fashion they currently are.

Vanoli has instilled some clear principles in his side in all phases of play, as any coach will when given the time to really put their stamp down on their team.

The defensive principles he’s brought to Venezia, in particular, have been effective and stimulating to watch be put into practice on the pitch throughout his tenure in charge, which is where the focus of this tactical analysis piece will lay.

We’re going to provide an in-depth analysis of Vanoli’s defensive tactics with Venezia in this piece, looking at what the 51-year-old coach demands from his players out-of-possession and how the out-of-possession approach he advocates has been vital to the club’s success under his leadership over the last year and a bit.

Paolo Vanoli Tactics – Basic defensive overview

Firstly, we’re going to set the scene for you with a brief overview of Venezia’s defensive setup and some general statistics that indicate how they’ve performed when it comes to keeping the ball out of their net this term.

Vanoli has been flexible in terms of shape, though his side has exclusively used four players in the backline.

However, we’ve seen plenty of 4-3-3 (or variations) as well as 4-4-2 and 4-2-3-1 on different occasions this term, so we’re really not looking at a formation-based system with Venezia, nor are we dealing with a three-centre-back setup.

Venezia have conceded the joint-second-fewest goals in Italy’s second-tier (16) at this point in the 2023/24 campaign and conceded the eighth-lowest xG (22.12).

Both of these numbers are respectable and point to the quality of the defensive setup that Vanoli has put in place, but it’s clear from the numbers that I Leoni Alati have needed their goalkeepers to bail them out on a few occasions this season to ensure their actual defensive record bests their record on expected numbers and has them performing to a really high level.

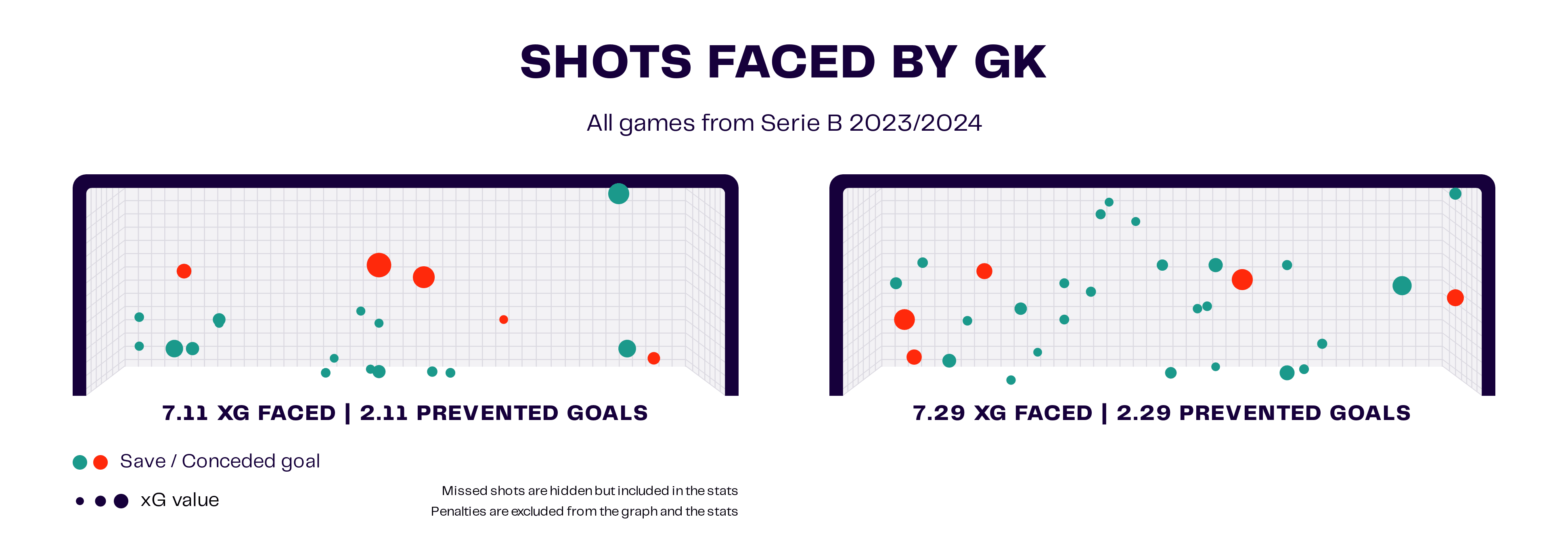

Two goalkeepers have featured fairly heavily for Venezia this season: Bruno Bertinato and Jesse Joronen.

We see both stoppers’ respective shots faced in Serie B this term in figure 1, with Bertinato on the left and Joronen on the right.

Both have faced similar amounts of danger and prevented similar amounts, too; very little separates the two ‘keepers purely based on their performances inside their own net in 2023/24.

Ultimately, Vanoli has two reliable shot-stoppers in his ranks who have been in good form when called upon this season — a lovely scenario for a coach, though keeping both happy will undoubtedly be an unenviable task.

I Leoni Alati have kept the fourth-highest average percentage of possession (52.3%) in Italy’s second-tier this term, which is a statistic that their out-of-possession approach has a lot to do with.

Paolo Vanoli Pressing

To start off, Venezia have operated a very well-organised press this season that’s made them a nightmare to play against for teams trying to play through the thirds.

Again, the actual shape they set up in has varied depending on the game and the opponent.

But the fundamental principles of their setup have remained consistent, and the quality with which this team has applied the manager’s defensive vision has played a major role in their out-of-possession success under his tutelage.

As mentioned, we’ve seen Venezia shape up in a 4-3-3 or a variation of the 4-3-3 plenty of the time this season.

When playing without the ball, the Serie B side’s front three get extremely narrow, looking to congest the centre of the pitch and force the opposition to play the ball out to the full-backs.

When the front three gets narrow, they form what’s known as the ‘Christmas tree’ formation, famously used by Carlo Ancelotti for periods of his tenure with AC Milan two decades ago.

The opposition playing the ball out wide is, then, a pressing trigger for Vanoli’s side, who will always look to use the sideline as an extra defender and try to win the ball back one way or another via an aggressive press on the wings.

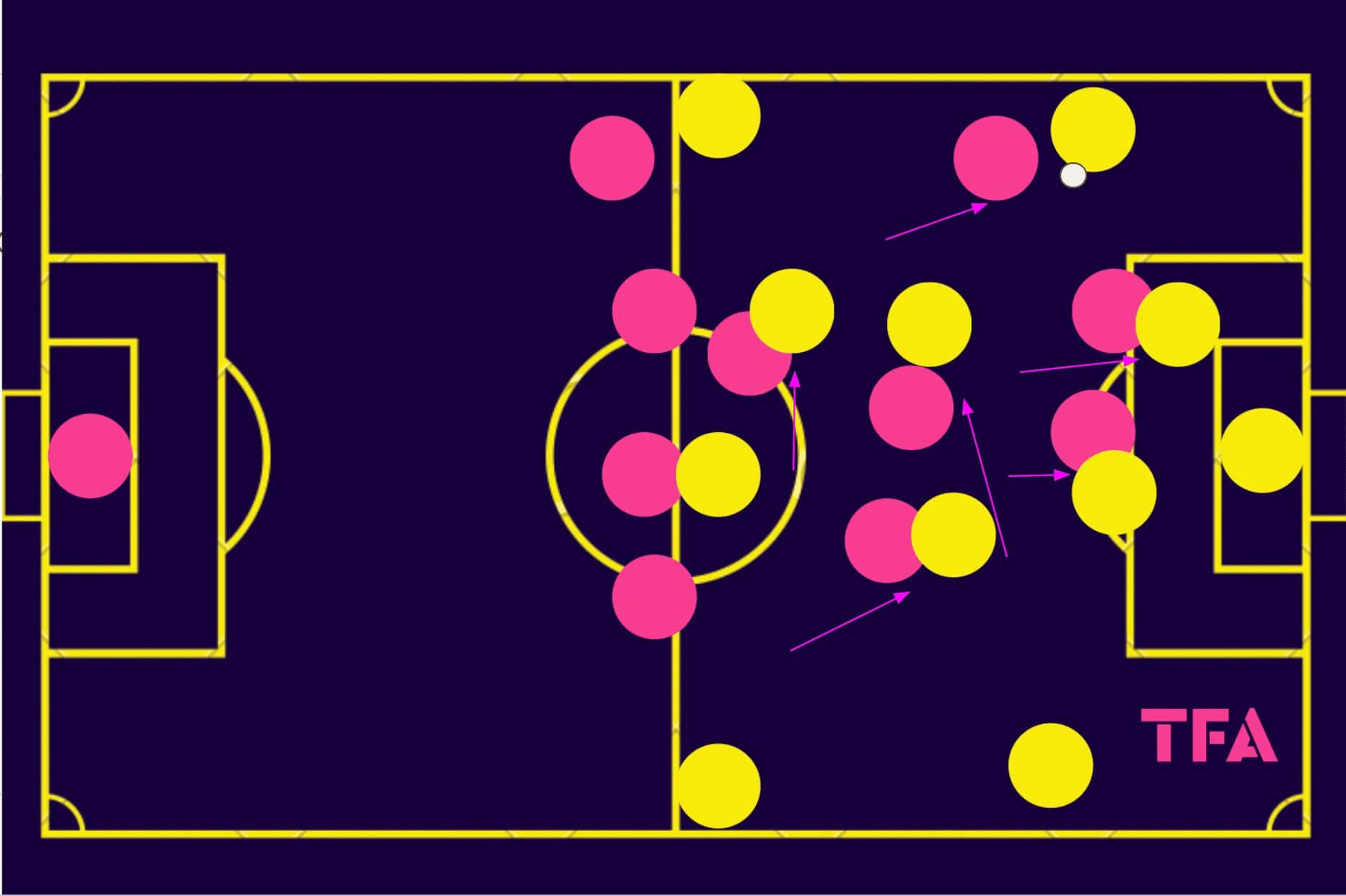

We see an example of how Venezia’s pressing scheme will unfold as the opposition play the ball out to their right-back here in figure 3.

The ball-near central midfielder will actually act aggressively and close down the receiver while the front three remain narrow, each marking a nearby passing option, including both centre-backs.

The rest of the midfield will shift over to maintain a fairly close distance to the pressing midfielder.

At the same time, the back four also shuffles to this side, congesting the space available for the ball carrier to potentially pick out a safe pass, doing what they can to remove that possibility.

One weakness of this approach is that it allows the ball-far winger and full-back to enjoy a lot of space, and if the opponent manages to pull off a switch pass, this can put Vanoli’s side in a lot of trouble.

However, the trade-off is that by congesting the space around the ball carrier, marking all the near passing options and aggressively pursuing the ball carrier themselves, Venezia can force high turnovers with regularity, generating plenty of goalscoring opportunities to offset the inevitable switches that will put them on the back foot.

Whether utilising this shape, a 4-4-2 or a 4-2-3-1, the principle of congesting the centre with a narrow shape before significantly increasing the intensity of the press on the ball carrier when the opposition move out wide remains constant for Vanoli’s team.

Here, in figures 4 and 5, we see Venezia’s narrow shape pressing the opposition out wide, this time in the mid-block phase.

Here, the opposition’s right-winger is the pass target, so Venezia’s left-back is the best option to close him down.

Meanwhile, all the other near passing options are blocked off, so the ball-near midfielder drops to make himself available for a pass into the centre of the park.

As the ball is played into the centre, the receiver is immediately dispossessed as several white and black shirts swarm around him and hunt the ball off his foot.

Venezia didn’t give the receiver a chance to get his head up and look at what options he’d have for his next move as they shut down the attack in an instant, drawing him into a pressing trap between several defensive bodies that would immediately close in around him on receiving the pass while keeping decent passing options in their cover shadow.

Venezia’s aggressive pressure is great for creating situations like this where lots of their players are in a similar location, available to trap an opponent like this to quickly win possession, and it’s great for forcing the opponent into rushed decisions, again, helpful for favourable turnovers.

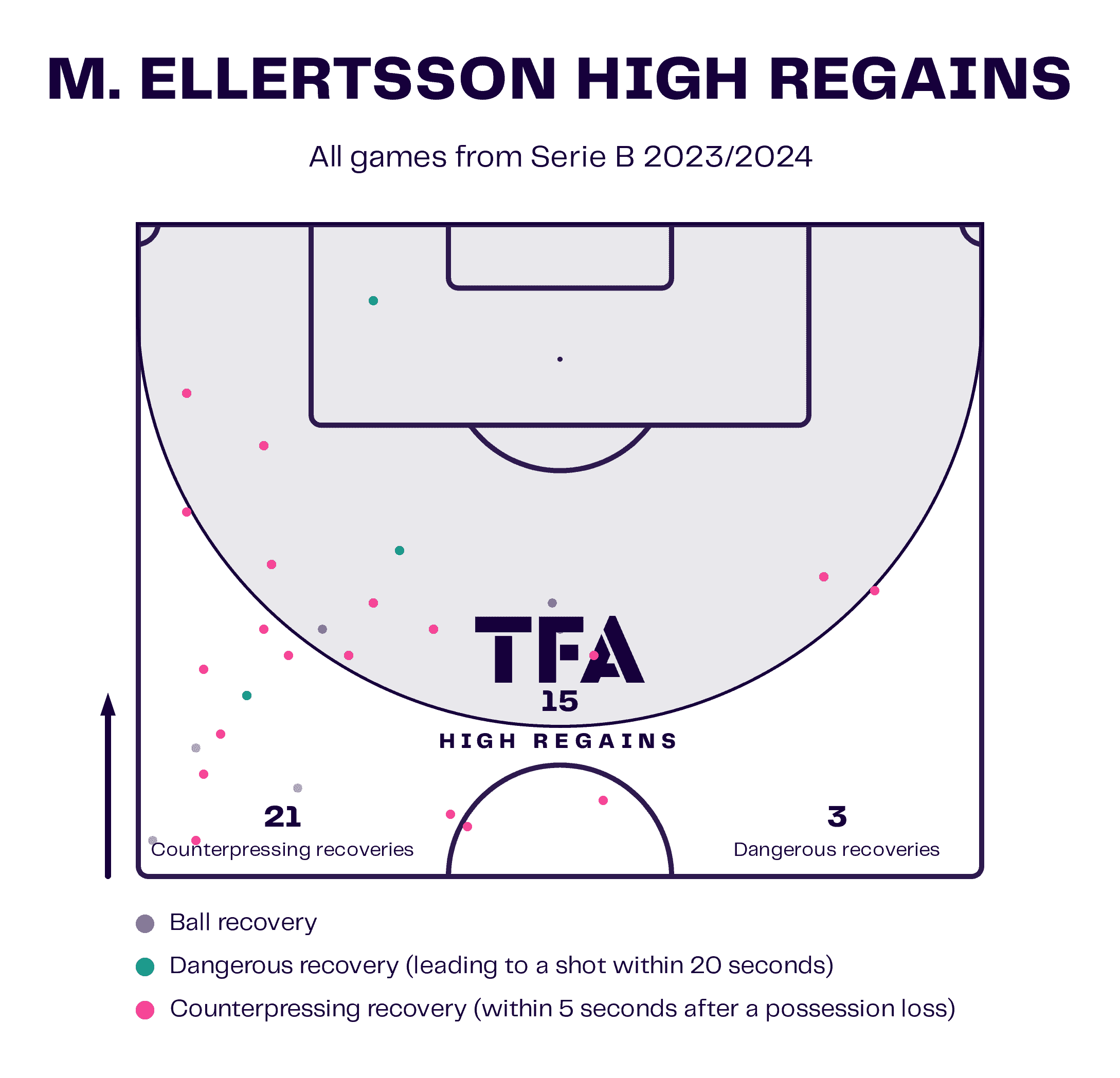

As per a recent post from CIES Football Observatory titled: “‘Marathon runners’ and ‘sprinters’ in world football”, Venezia’s 21-year-old winger Mikael Egill Ellertsson has made more sprints in the defensive phase per 90 than any other player in Italy’s second-tier this term.

That’s largely a result of his role within this defensive setup that often sees him having to quickly close players down aggressively as the ball is played out wide by the attacking team in the build-up and ball progression phases.

To his credit, Ellertsson has performed the job required of him to a high level, constantly closing down opposition wide receivers in an instant, denying them time and space, doing his part to ensure Venezia’s pressing scheme operates on the highest possible level to enhance their all-around performance.

As shown by figure 6, this Icelandic winger has made his fair share of high regains, especially counterpressing recoveries, in 2023/24.

That brings us nicely into our next section, where we’ll look at the importance of counterpressing for this Venezia side in greater detail.

Paolo Vanoli Counterpressing

Constant counterpressure has been a common feature of Vanoli’s Venezia side — we always see this team apply aggressive pressure to the opposition immediately after a turnover with the aim of using that counterpress as a playmaker to generate a goalscoring chance of their own by regaining the ball high and subsequently attacking a weakened unprepared backline.

Vanoli will commit plenty of bodies to advanced areas as Venezia move into the ball progression and chance creation phases of possession, partly with the aim of overloading the opposition with the ball and creating a valuable goalscoring opportunity but also with the aim of having lots of bodies close so if they lose possession, they can immediately counterpress in numbers to try and win the ball back.

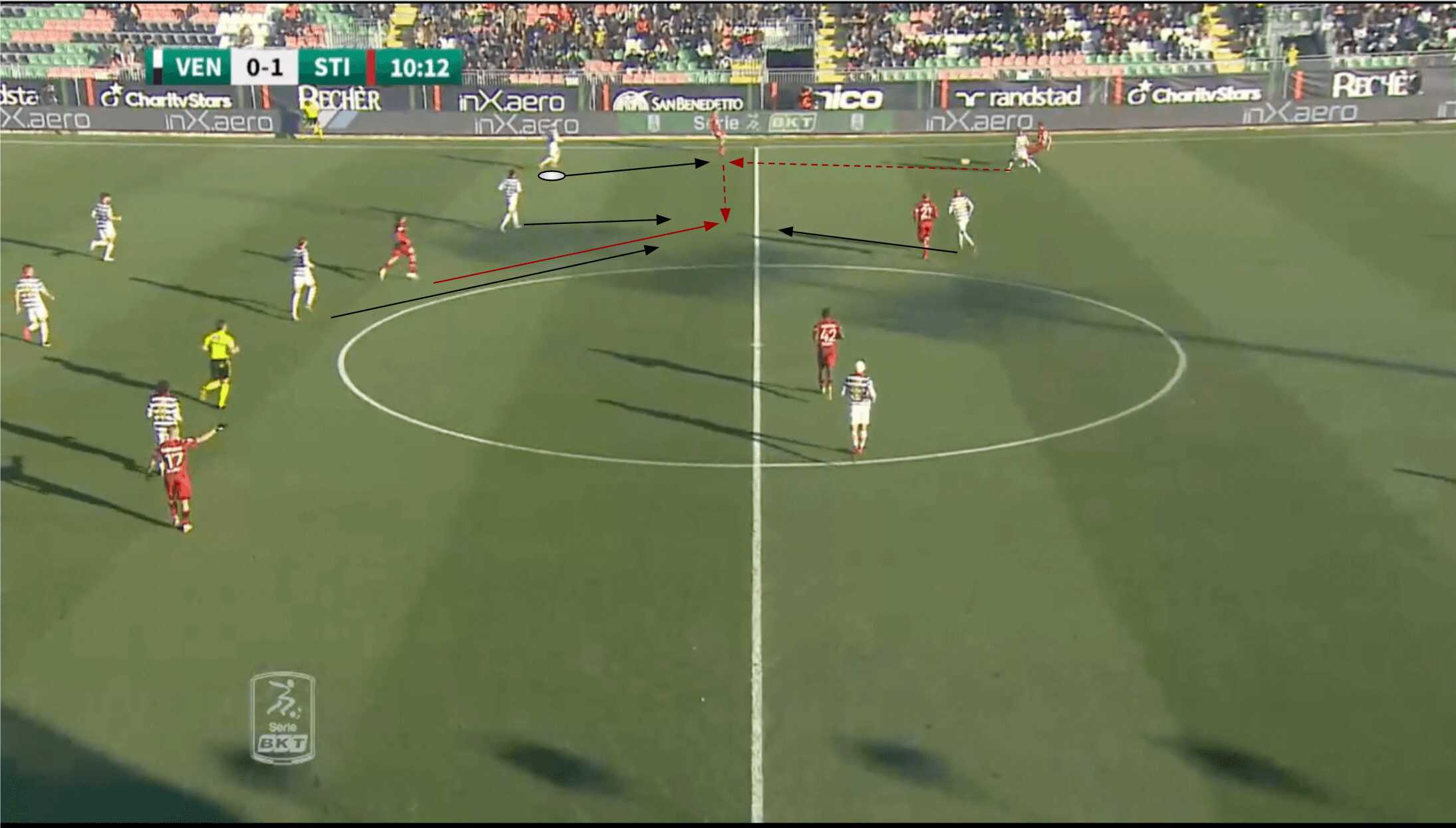

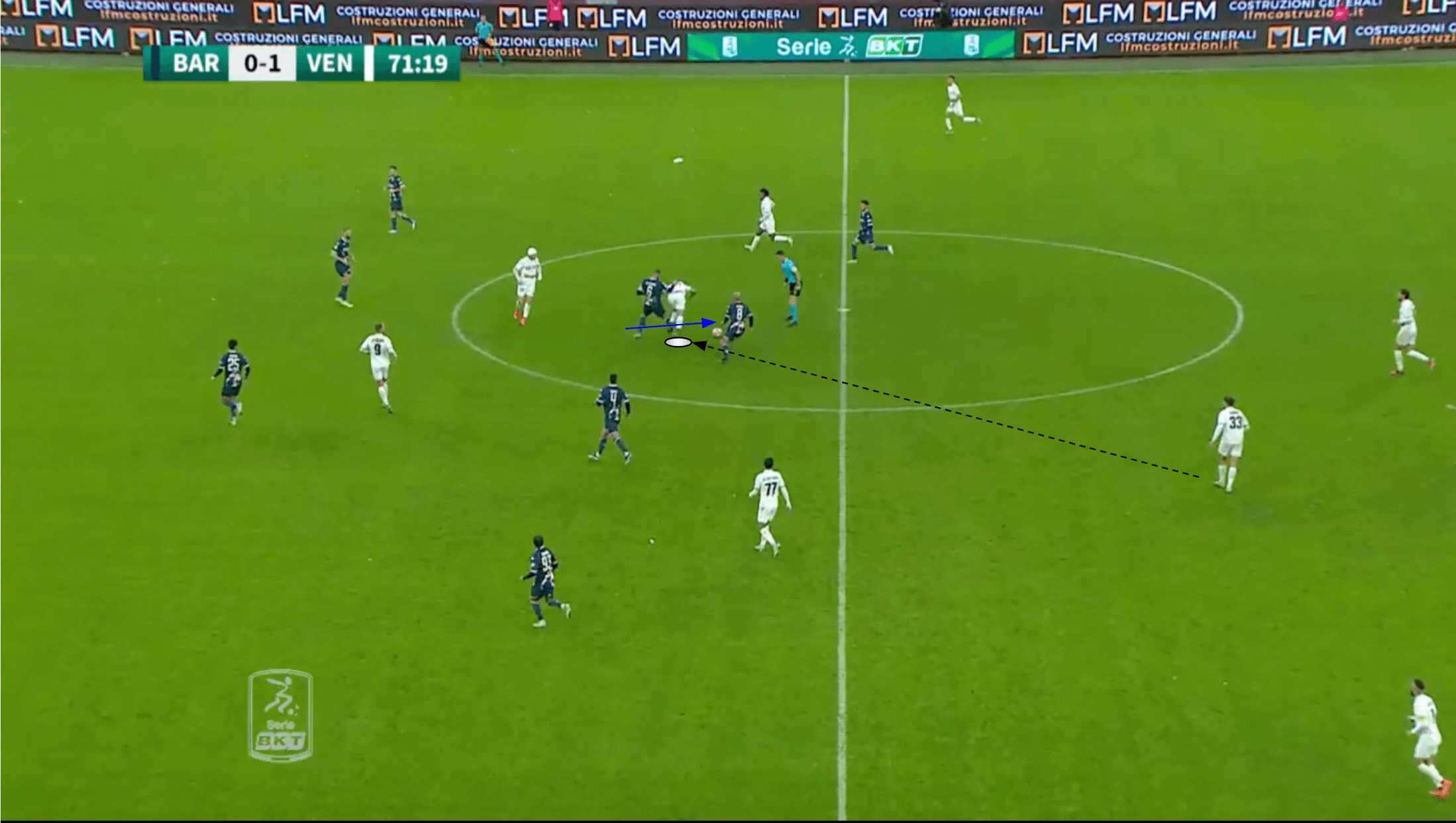

Take figure 7 as an example.

Here, Venezia fired a long ball forward from the back, which is met by the opposition defender’s head.

As the header easily finds a friendly body on the edge of the box for the opposition, Venezia instantly become more dangerous.

Why? Because as soon as that opposition player controls the ball while facing his own goal on the edge of his box, Venezia bodies are swarming the nearby passing options while one I Leoni Alati player takes the responsibility of pressing the ball carrier, preventing him from turning and trying to force him into a bad move.

After a couple of failed attempts at playing their way out of Venezia’s press, the opposition ultimately end up being forced to play the ball out for a throw-in to I Leoni Alati just on the edge of their final third — not a bad result for Vanoli’s side who gained a lot of ground and have now set themselves up to kickstart an attack from a highly valuable position for chance creation.

Venezia had lots of bodies nearby, marking potential passing options for the opposition, while any opponents who found some space and became a new near passing option were very quickly closed down and prevented from progressing their attack any further forward.

This is an excellent example of how a team can pin the opponent into a confined space via constant, aggressive counterpressure and why it can often force valuable turnovers for the pressing side to then go on and create something from.

Had Venezia regained possession in open play here, the opponent would’ve had no semblance of defensive organisation to combat the resulting Venezia attack.

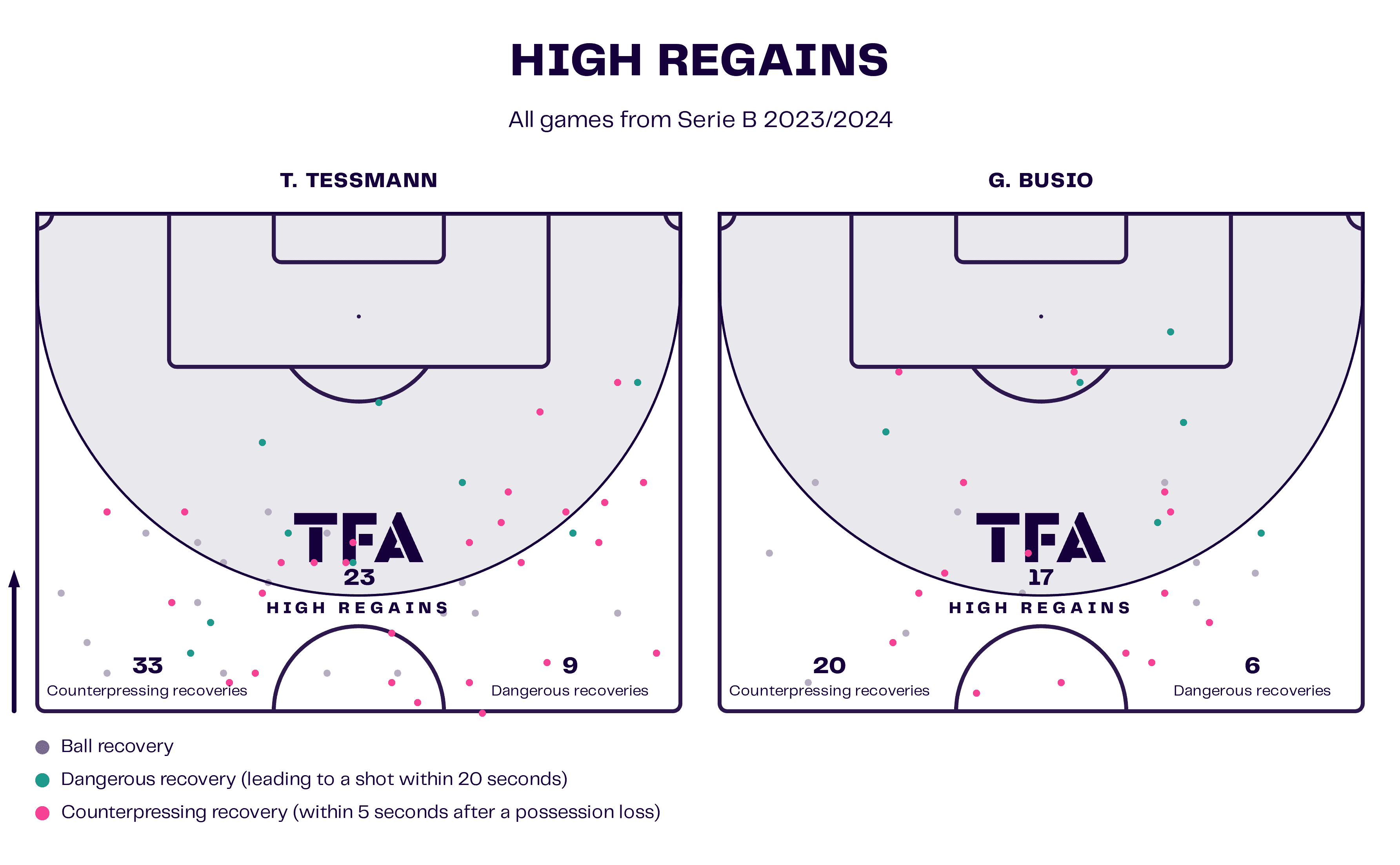

We mentioned earlier that I Leoni Alati’s central midfielders are often tasked with pressing aggressively high in the high-block and mid-block phases while the forward line remains narrow; they are also precious assets in producing counterpressing recoveries, similar to the wingers, as we can see from figure 8 which displays Tanner Tessmann and Gianluca Busio’s respective high regains from 2023/24 to date.

Both of these players provide an excellent defensive work rate for Vanoli in all phases of out-of-possession play, and both men are extremely active in Venezia’s counterpressing, too, with this type of recovery unsurprisingly dominating the high regains map for both above.

Now, with committing a lot of bodies forward in the progression and chance creation phases comes the risk that the opposition will be able to either regain the ball early — from Venezia’s deep-lying midfielders, for instance — or will be able to quickly launch the ball upfield after regaining it deep to exploit their weakened backline.

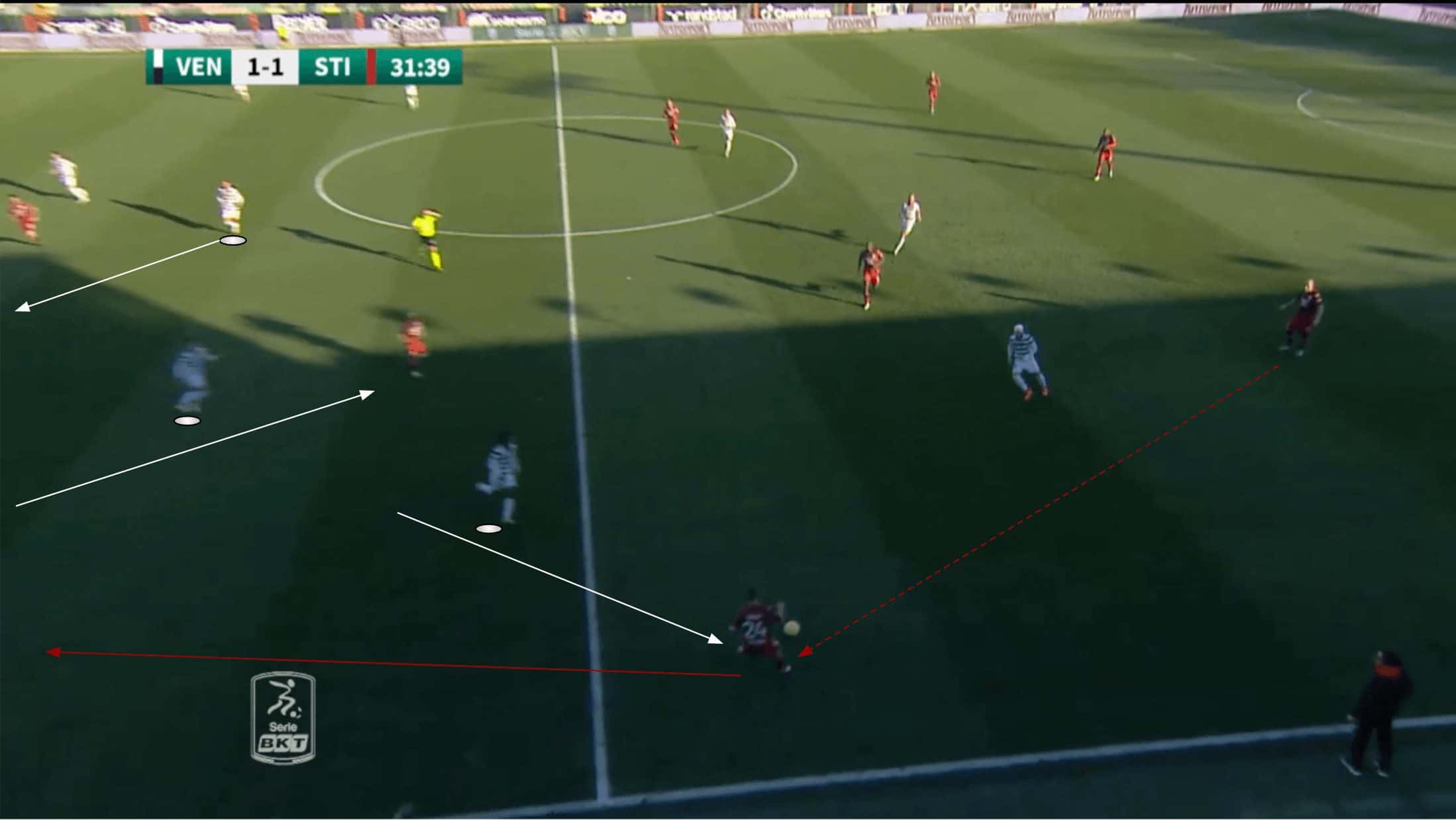

We see an example of the former in figures 9 and 10.

As Venezia played the ball into midfield in the progression phase, the receiver is immediately dispossessed and starts carrying the ball forward into I Leoni Alati’s half.

Venezia like to send both full-backs forward in the progression phase, along with their more advanced central midfielders or one midfielder if they’re operating with a double-pivot.

Essentially, they’ll often end up with just three men back — their two centre-backs and one holding midfielder — which is extremely weak for defending against the counterattack.

On this occasion, the ball carrier plays the through ball to the runner on the left, setting up a 1v1 with Venezia’s right centre-back.

If the dribbler comes out on top of that, they’re through on goal.

This is where Vanoli’s side are extremely vulnerable — they commit bodies forward and have a great setup for counterpressing in advanced areas; however, they are weak in the defensive transition when they occur in deeper areas.

Paolo Vanoli Defending in deeper areas

Speaking of deeper areas, we can now move on into the final section of our tactical analysis piece — Venezia’s approach to defending in deeper areas in settled defensive phases.

Vanoli’s side will essentially continue utilising the same shape they utilise when defending higher upfield, be that a 4-3-3, the Christmas tree shape, 4-4-2 or 4-2-3-1 in that particular game.

However, they’ll typically keep their centre-forward on about the halfway line as an outlet should they regain possession and need to clear the ball away or be on the lookout for a quick counterattacking opportunity.

Every other player will get very vertically and horizontally compact — more than in any other phase of play as they try to protect the most valuable areas of the pitch for them in a defensive sense while the opposition pile bodies forward while occupying their most threatening positions.

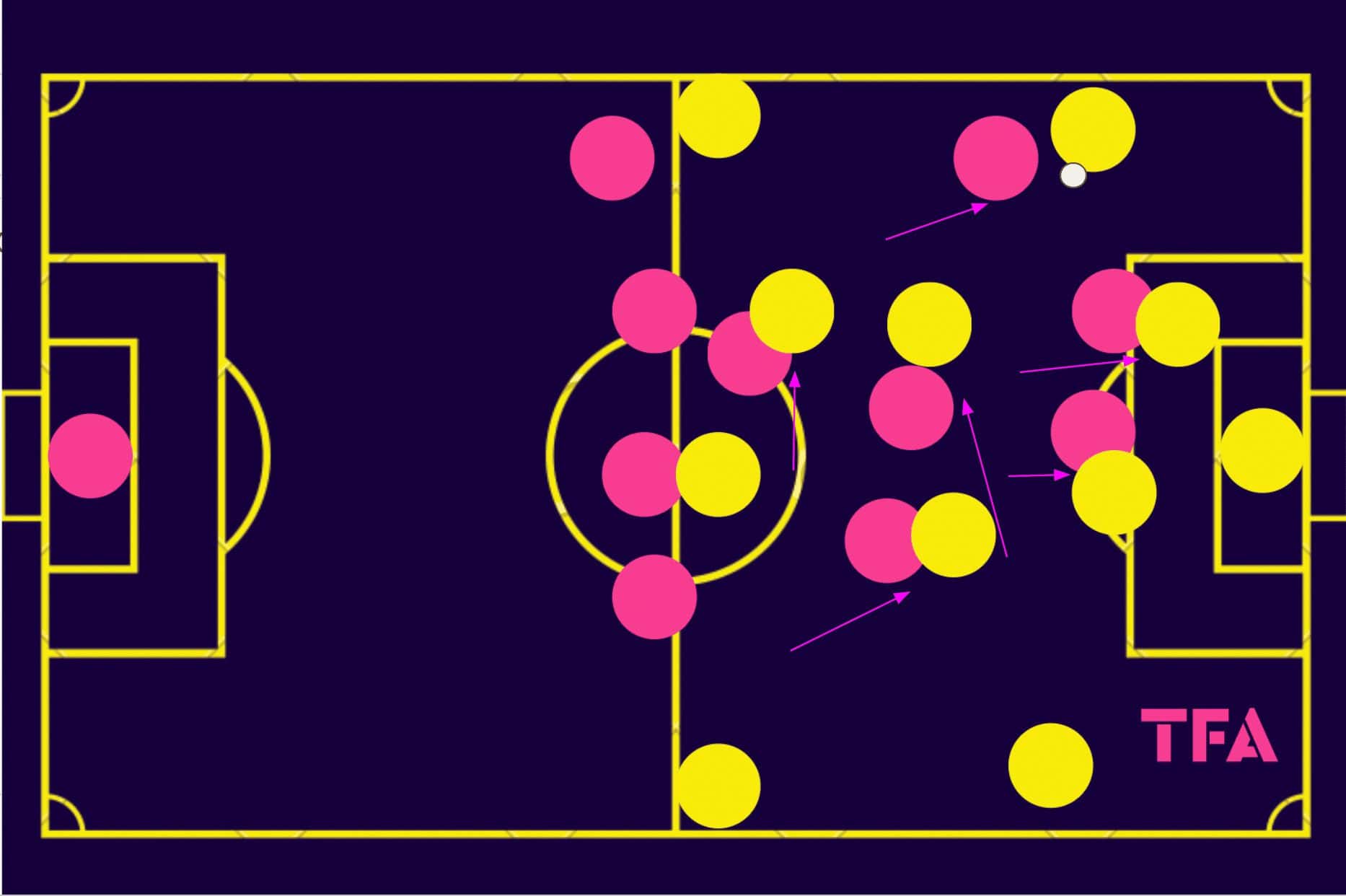

Venezia’s holding midfielder(s) can play a vital role in their deep defending a lot of the time, including this example from figures 11 and 12.

Here, in figure 11, we see the opposition full-back receiving on the left wing, pulling Venezia’s right central midfielder out into a 1v1 defensive duel.

To prevent a free man opening up behind the midfielder, I Leoni Alati’s right-back then moves inside to pick that player up.

This frees up space behind the pressing midfielder on the wing, however, which the opposition ball carrier tries to take advantage of as he continues this attack with a dribble down the wing.

Venezia’s right centre-back is then pulled out from the backline to close down the dribbler and to prevent massive gaps from opening up in the backline; Vanoli’s holding midfielder tracks back extremely diligently to close the gap, having observed the right-back coming out and preemptively began tracking back aggressively as we can see in the background of figure 11.

It’s fortunate for the Serie B side that he did so; as we can see in figure 12, his presence in the backline proved vital to preventing the opponent from getting into a really dangerous goalscoring position.

It’s common to see Venezia’s holding midfielder(s) plugging gaps like this when their team has to defend deep — mostly as a result of Vanoli’s pressing approach, which requires players near the opposition ball carrier and any viable passing options to bravely step up and combat the attacking team.

The ball-far players with no immediate threats in front of them, like the holding midfielder in figure 11, should then be disciplined enough to look behind them and provide cover when necessary, as was the case in this instance — a perfect example of the defensive teamwork Vanoli wants to see from his side out-of-possession.

Blocks from the centre-backs will also inevitably come in very handy for Venezia when defending deep, with right centre-back Giorgio Altare, in particular, making a significant mark in that respect this term, blocking a total of 15 shots combining to equal what would’ve been 2.19 xG.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis piece on Venezia’s out-of-possession approach, Paolo Vanoli has put Serie B’s fourth-youngest squad (25.4) into second place at about the midway point of the season through some excellent coaching and extracting plenty of commitment from the players.

Vanoli demands a high work rate, energy, organisation, alertness, and discipline from his players in the defensive phases.

He needs his players to come together and work as a unit, which, more often than not, they have done this term, as we’ve seen just a tiny example of via our analysis.

If Venezia can maintain their current level in all phases, including their out-of-possession phases where they’ve been Serie B standouts this season, they may well regain their top-flight status for 2024/25.

Comments