One of the most enjoyable aspects of football is seeing young managers rise to prominence and implement their own philosophies and ideologies on the game beloved by all.

Unlike in days gone by though, young coaches have been heavily influenced by the positional play blueprint left by Pep Guardiola and the Total Football principles laid down by some legendary Dutch coaches including the late Johan Cruyff, Louis van Gaal and of course, its founding father, Rinus Michels.

One of these coaches is Venezia’s, Paolo Zanetti. The Italian coach is the youngest manager in Serie A, at just 39 and managed to get Venezia promoted to the top division from Serie B at the first time of asking through the play-offs. This was the club’s first time back in Italy’s top-flight in 19 years.

The Venetian club, who had a busy summer window, are sitting in 16th place currently, playing some of the best football in the league from a subjective perspective, which is a massive credit to Zanetti and his coaching staff.

This tactical analysis piece will be focusing on the tactics deployed by Zanetti. It will be an analysis of how Venezia have set up so far this season, tactically, under their young coach.

Formation and style of play

It would be safe to say that Zanetti is a manager who prefers to set this Venezia team up in a back four. This is the manager’s second season in charge of the Italian side, and he has yet to deploy a back three in any official competition.

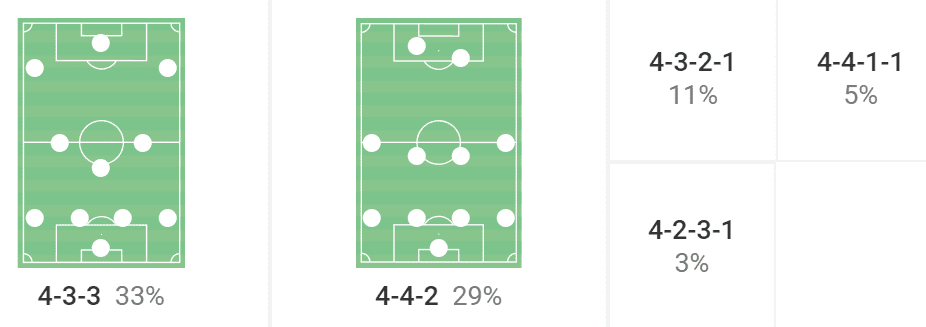

However, it is also a fair assessment to say that it can be very difficult for any opposition coach to predict which formation Venezia will play in. Zanetti has set his side up in numerous structures so far this season, most notably the 4-3-3 which has been utilised in 33% of the team’s matches.

Nonetheless, the 4-2-3-1, 4-4-2, 4-3-2-1, and 4-4-1-1 are not uncommon choices from the young coach either.

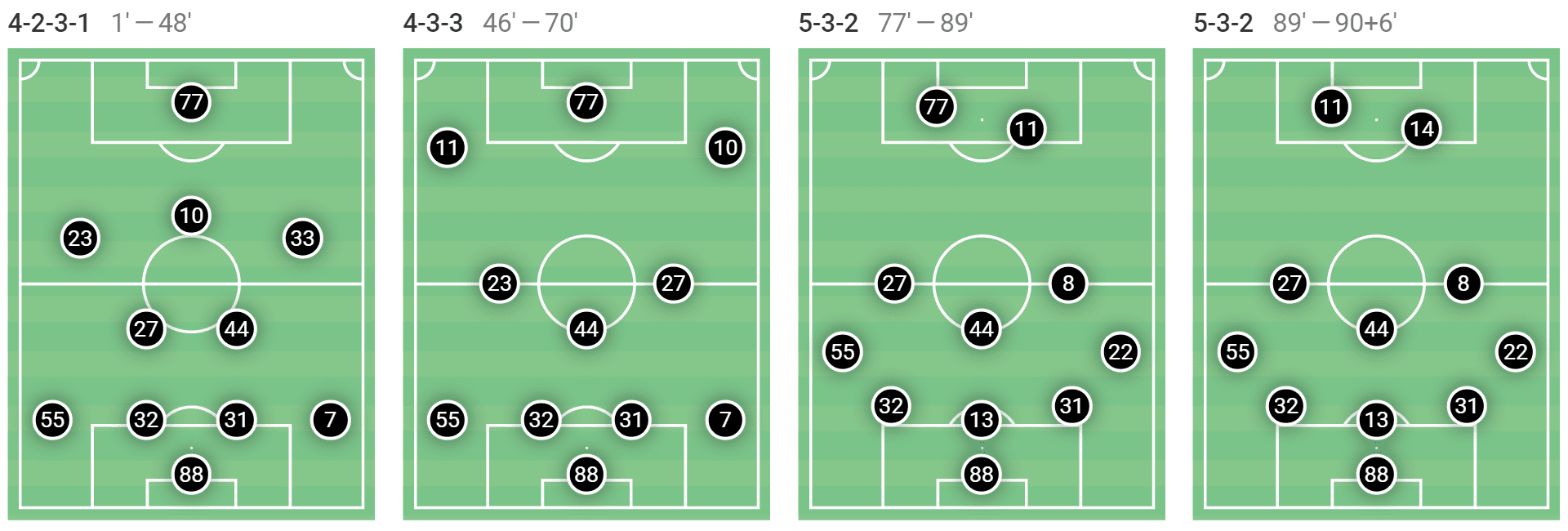

The manager has a tendency to rotate his players too, in order to slightly adjust the system for each opponent, but his tactical tweaks have been proven to work so far this season. In a recent fixture against José Mourinho’s AS Roma, Zanetti originally set his team up in a 4-2-3-1 but later switched to a 4-3-3 and eventually a 5-3-2.

The first systematic change was made at the interval when the Venetian team were 2-1 down. By the end of the game, Venezia had turned the score on its head, winning 3-2 when the referee blew for full-time.

In terms of the style of play that Zanetti has implemented, the team tend to cede possession for large parts of the game, soaking up pressure from the opposition in a proactive defensive block before attacking the spaces in behind once the ball is turned over. Venezia have averaged just 42.4% of the ball this season.

However, there is still a large emphasis on the principles of positional play when Venezia have possession of the ball, such as fluid build-up play, wide overloads, and vertical passes in an attempt to find more advanced players in pockets of space between the lines of the opponent’s defensive block. These will all be analysed in further detail.

Breaking the press

Zanetti does not want his team to be predictable in this vastly important phase of the game. Venezia use a number of different variations in the deeper areas of the pitch in order to progress play higher and break through the opponent’s press.

Several factors are taken into consideration when deciding which variation to use, including how many players are committed to the defending team’s press, how many players are in the opponent’s first line of pressure, as well as the formation that Zanetti has deployed.

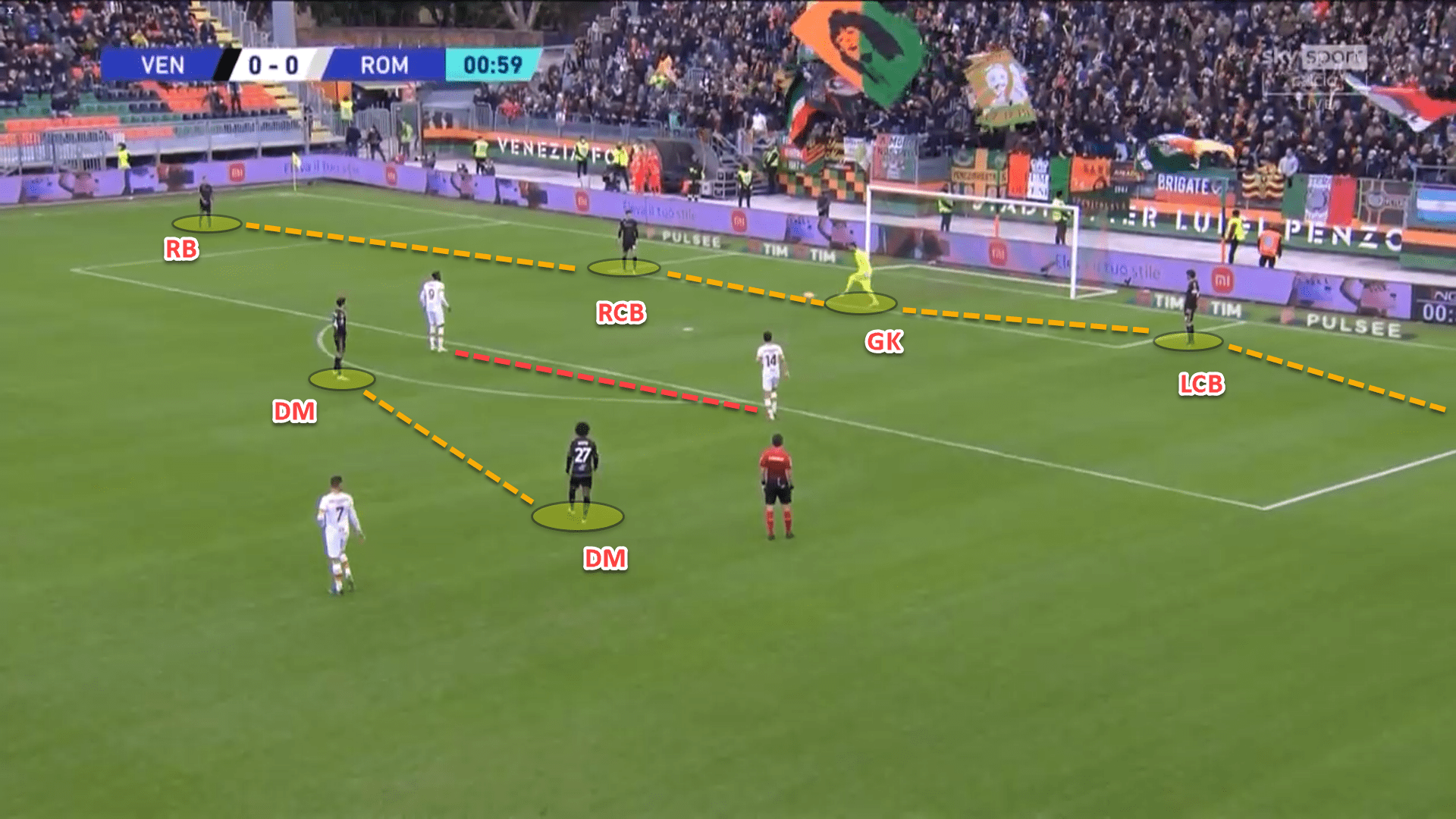

One way that Venezia look to progress the ball from deeper areas of the pitch is basic. The centre-backs will split wide, allowing the goalkeeper to position himself as a third passing option between them. The fullbacks remain low while the double-pivot position themselves behind the opposition’s first line of pressure.

Generally, the objective in this instance is to play into the double-pivot, breaking the first line of pressure and getting the midfielders into a position where they can open themselves up to play forward and progress play.

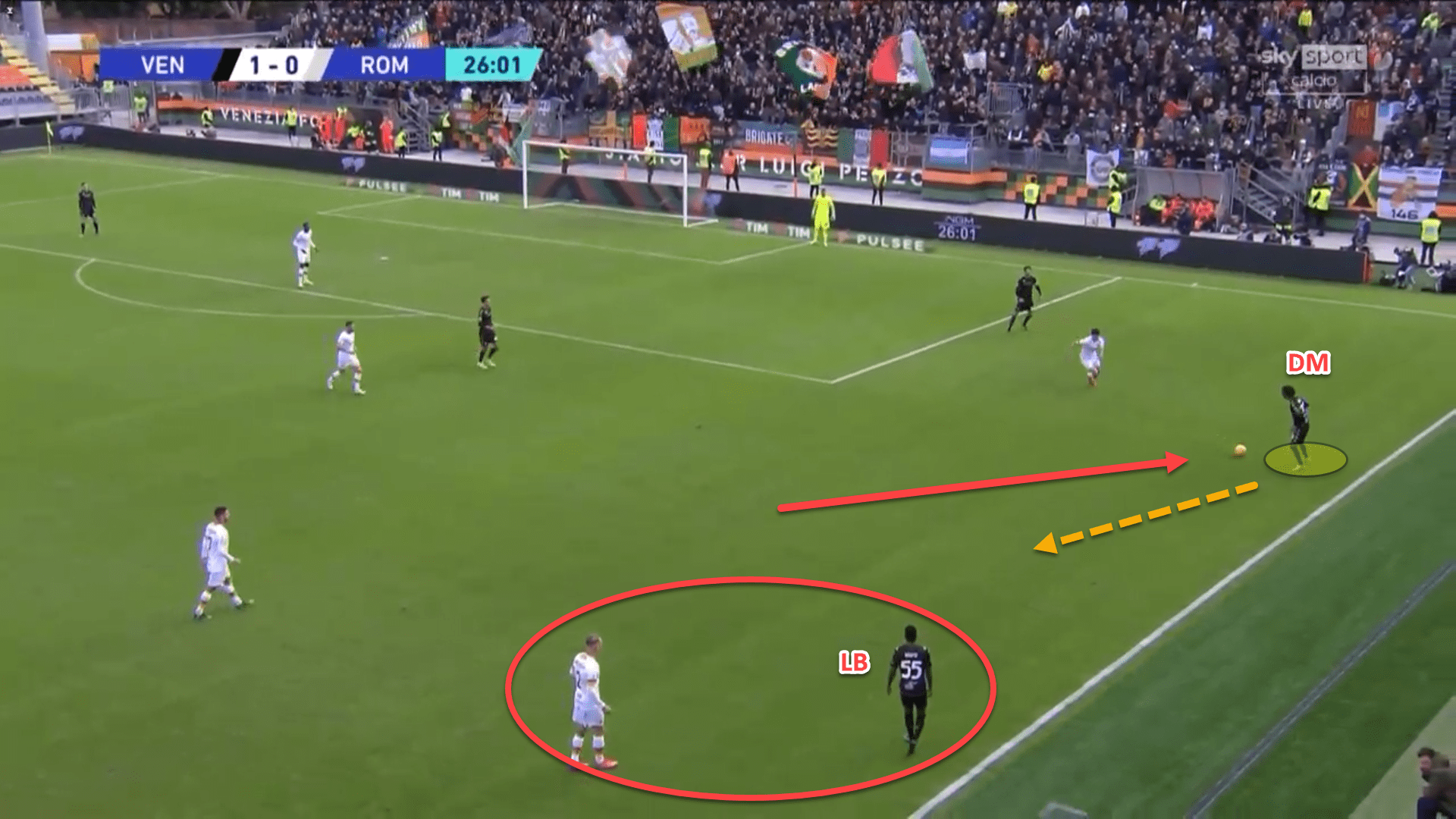

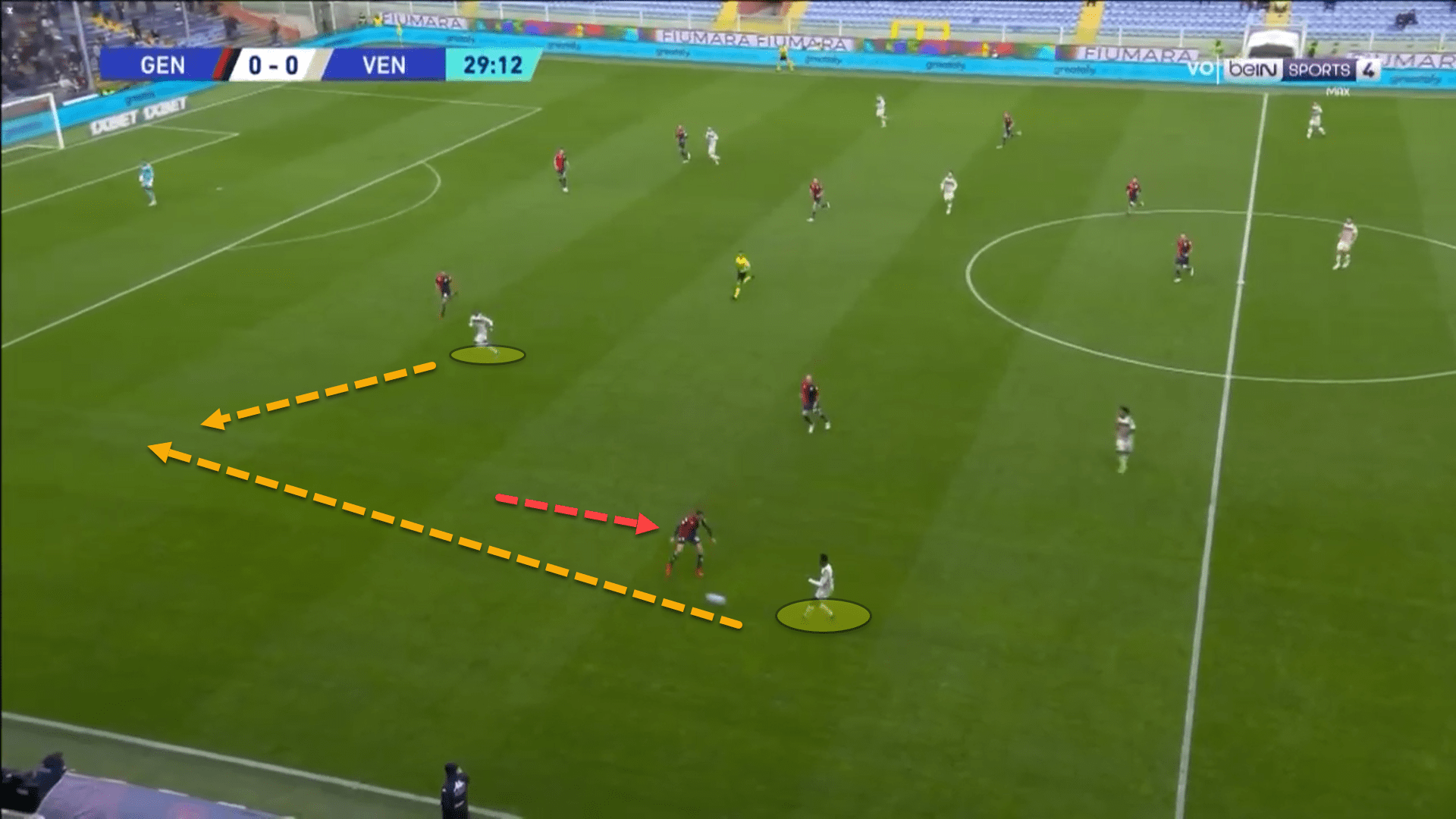

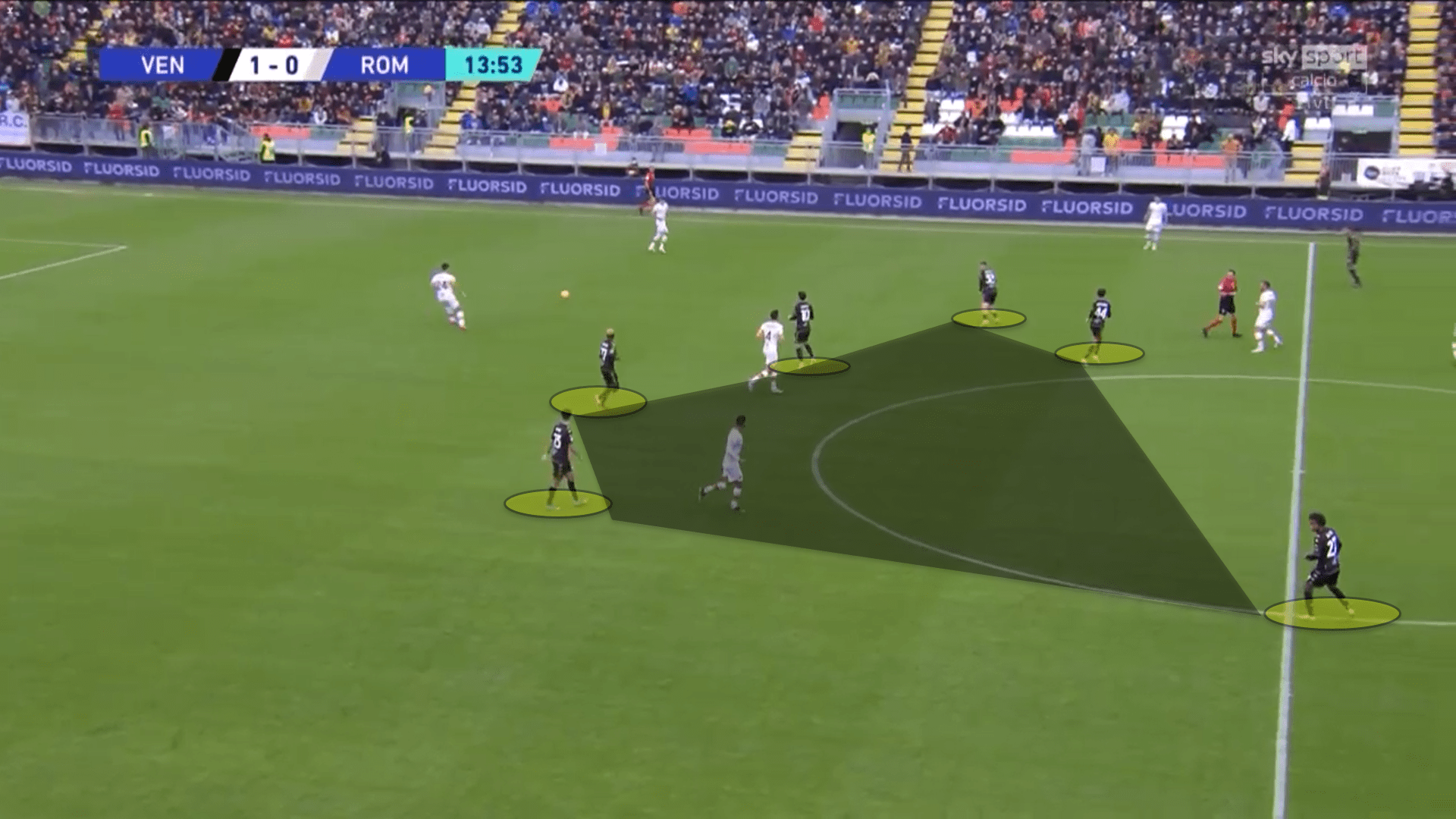

Here, the centre-back has enticed the centre-forward to press him and has slipped the ball into the furthest defensive midfielder, Gianluca Busio, which has broken AS Roma’s first line of pressure.

Subsequently, on reception of the ball, Busio is being pressed from behind and so plays first time into the feet of his partner in the pivot, Ethan Ampadu. The Chelsea loanee can then open his body out and play forward. In this instance, Zanetti’s men have successfully broken through Roma’s press and have manipulated the opposition to bring the ball from a deep area into a higher position on the pitch.

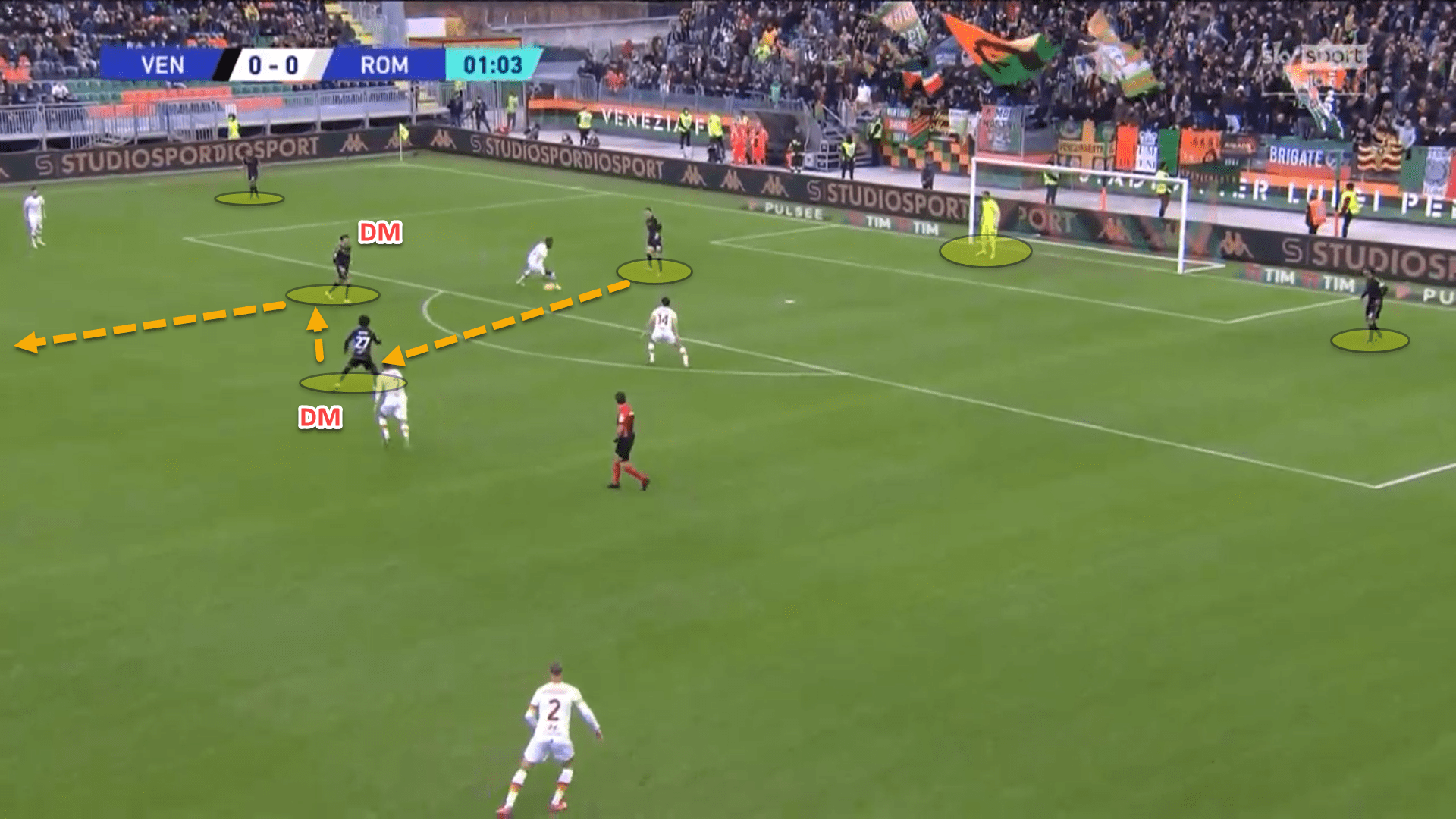

Another way Zanetti has instructed his side to play in the build-up phase is by a midfielder dropping out to the flanks, allowing the fullback on that side to advance further forward.

This is called a wide rotation and is useful because it disrupts a team’s structure regardless of whether they are defending high or in a deeper part of the field. It also helps players receive in space.

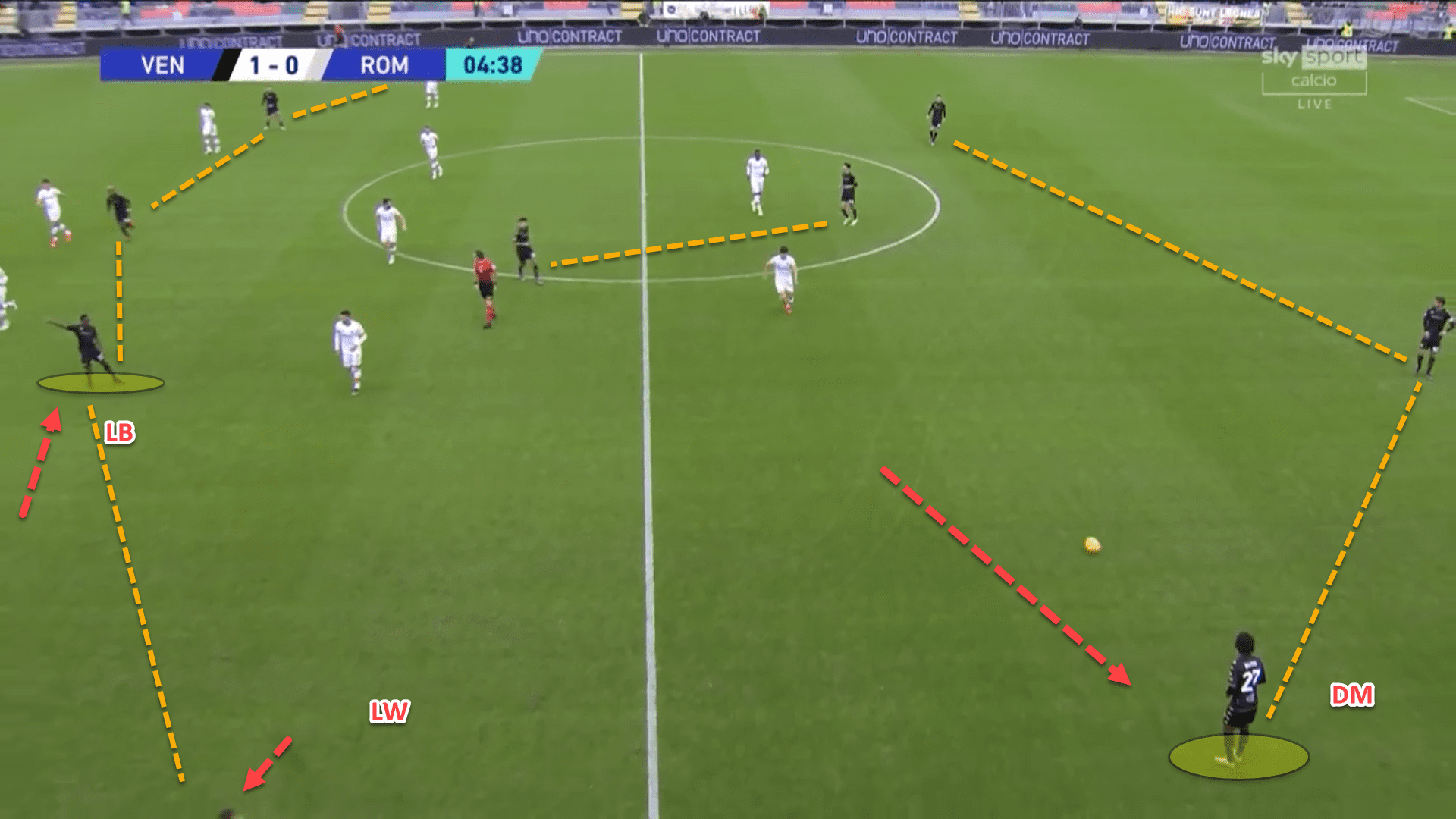

In this instance, Busio has dropped out to the left flank while the Giallorossi are pressing high during Venezia’s build-up phase. The left-back, who would normally be in this position, has pushed further up the field to facilitate this and has brought his marker with him.

By doing so, nobody is marking Busio and the United States international can receive the ball under no pressure, drive into space or else carefully pick his next pass, which allows Venezia to progress further up the pitch and out of the press.

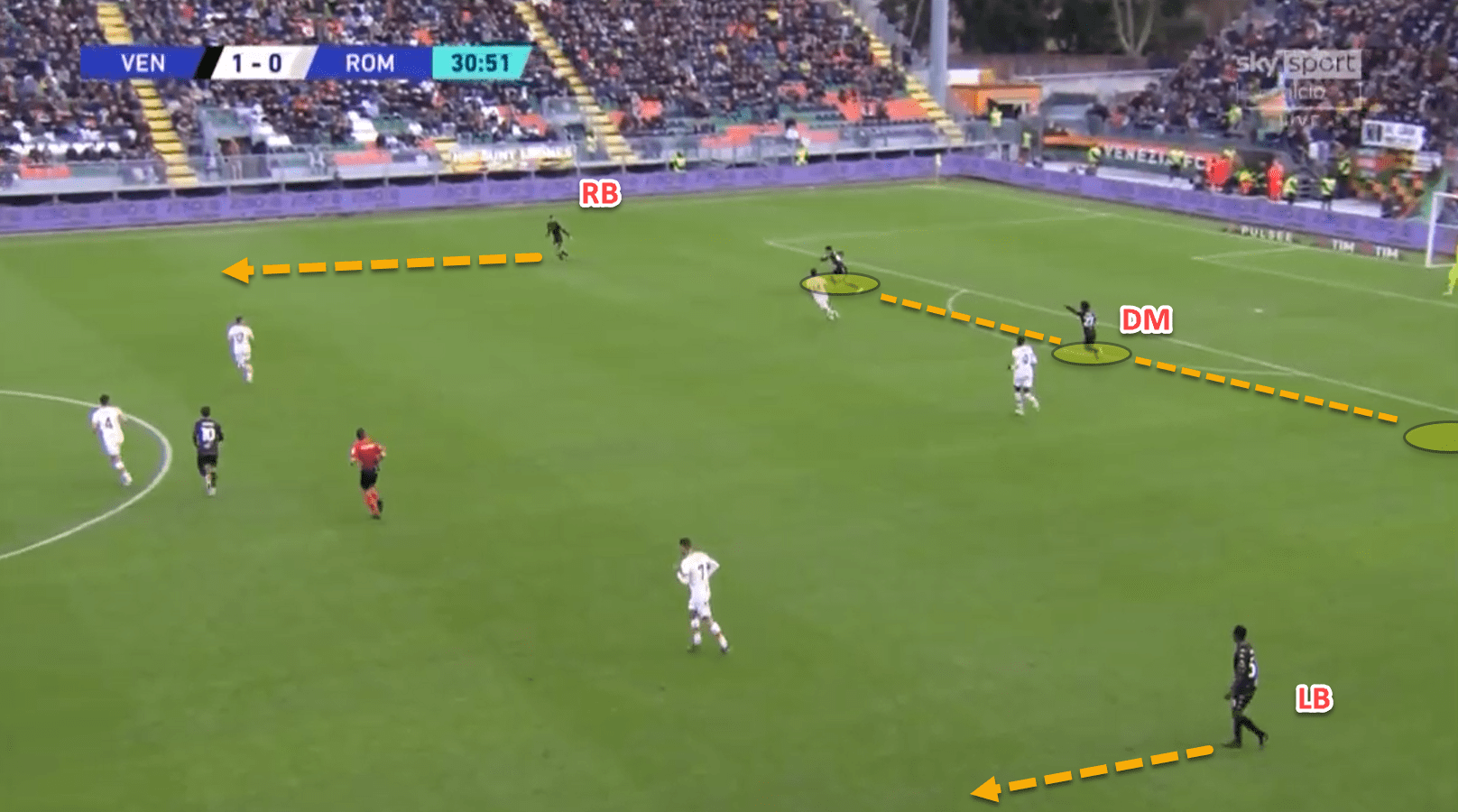

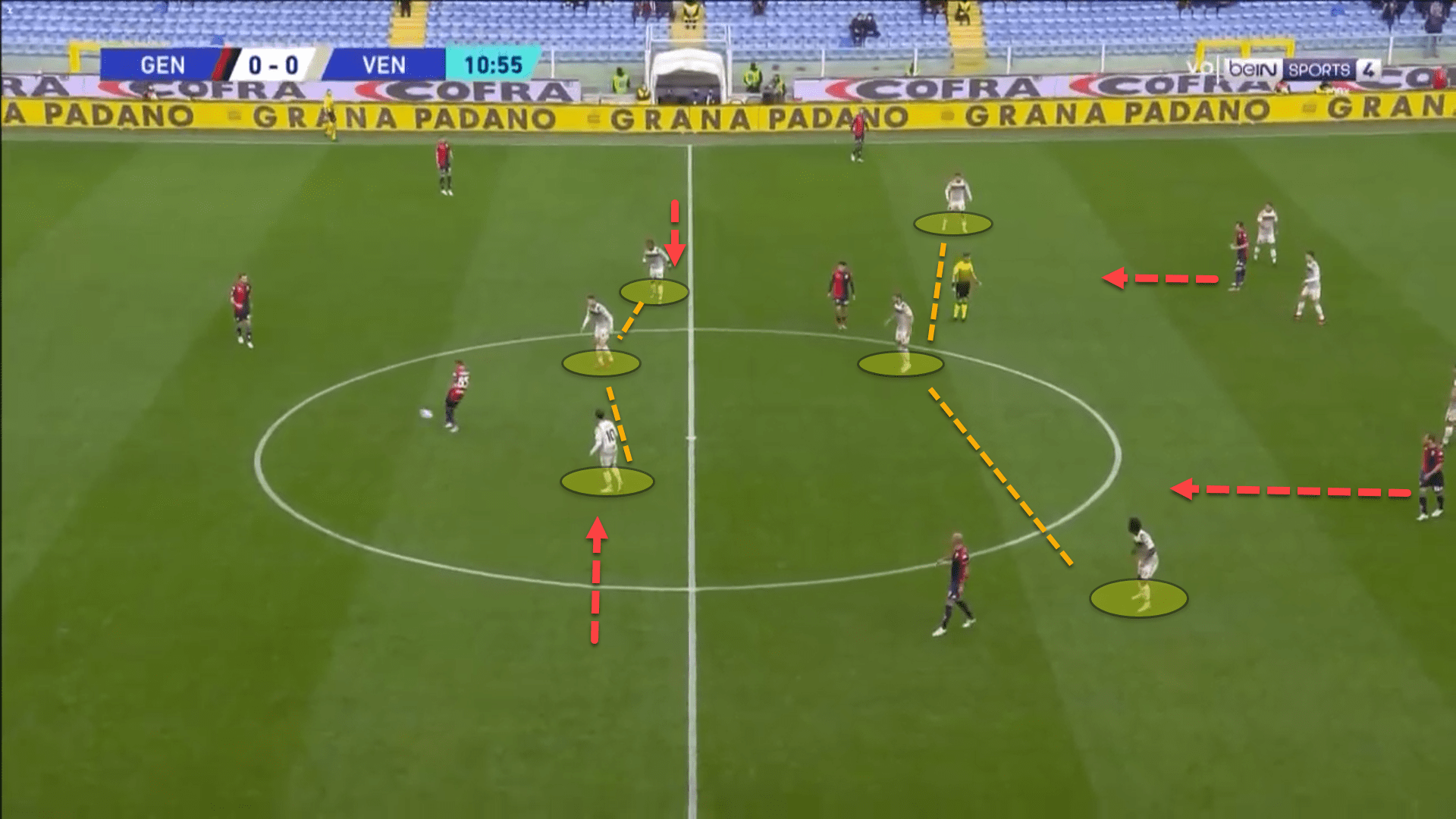

Finally, and in a very similar fashion to the last, one of the midfield players drops in between the two centre-backs, allowing both fullbacks to push higher up the pitch while creating a temporary back three.

This is only done when the opponent have two players in their first line of pressure. While the other two variations are used against a three, as it gives Venezia a 4/5 vs 3 in the build-up phase, if the defending side have committed just two players in the first line of pressure, Zanetti’s side can afford to push the fullbacks on, drop a midfielder into the backline and simply create a 3 vs 2 situation.

Looking at the previous image, Busio has dropped into the backline between the two central defenders. He can visibly be seen shouting at his right-back and pointing at him to push forward up the pitch as he has now become a temporary defender while in possession against Roma’s two centre-forwards.

Variations in the build-up phase of a team’s positional attack are extremely important and are certainly vital for Zanetti’s blueprint because the young coach wants his side to invite the opposition to press and then exploit space behind the backline with direct passes which will be analysed in further detail.

Direct play and positional fluidity

Venezia’s positional attacks tend not to be very prolonged. Generally, the idea from Zanetti is to get the ball up the pitch as quickly as possible and exploit space behind the opposition’s backline when they move up to press.

When the opponent’s press is broken, Venezia speed up their play and start playing one-touch passes in order to exploit the spaces in the opposition’s defensive structure.

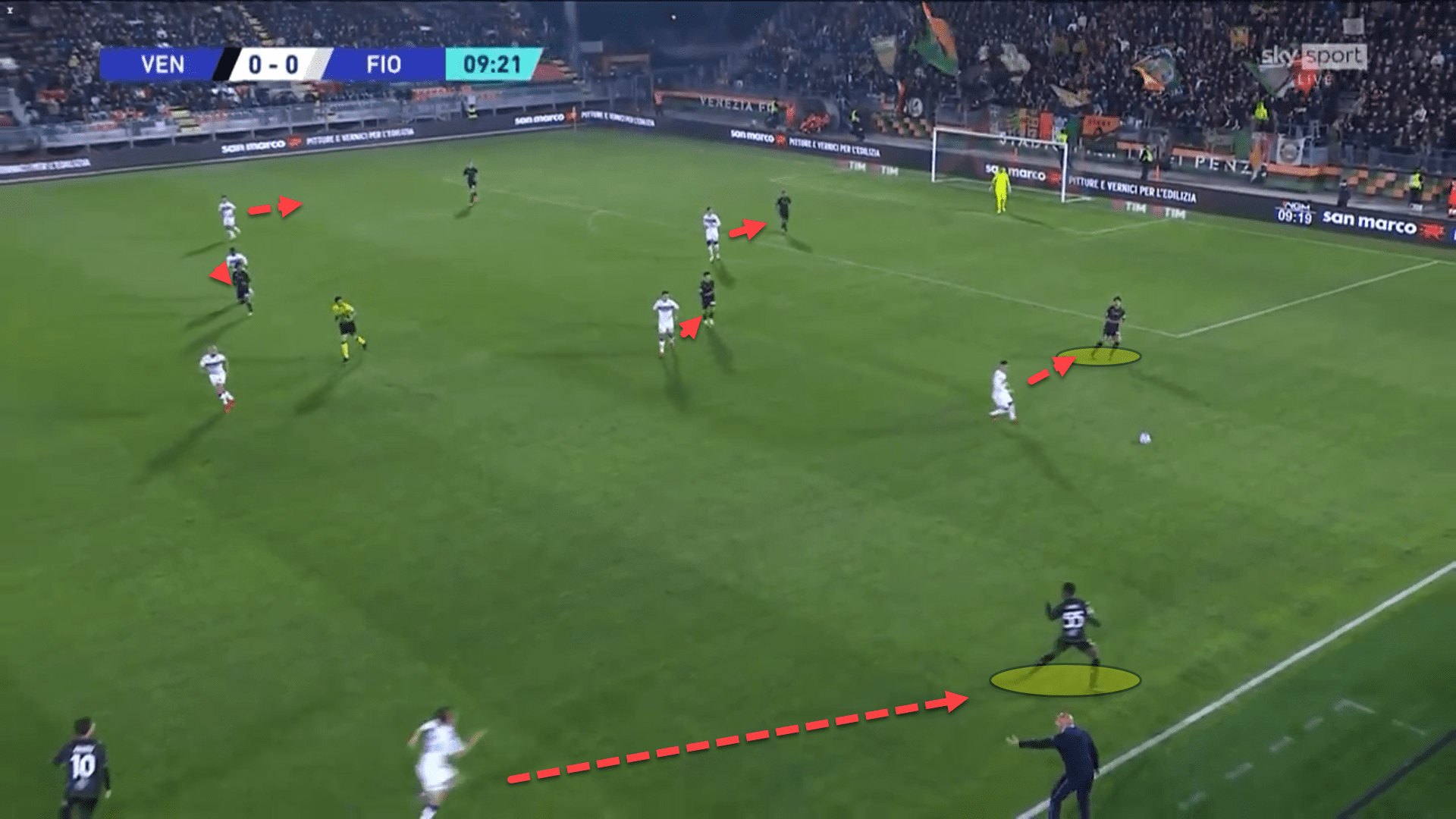

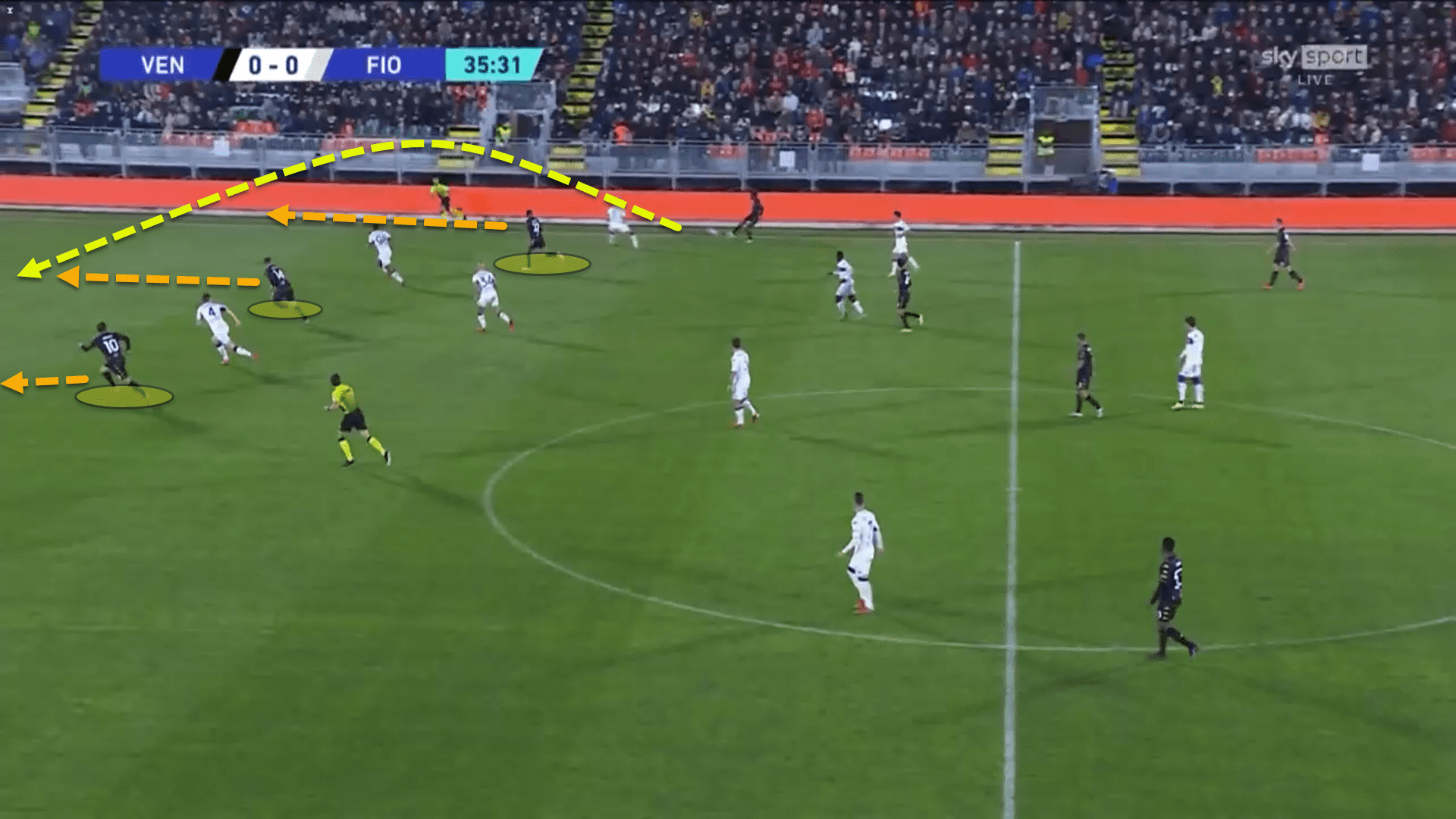

In this instance, the centre-back has played the ball out left to the fullback. Fiorentina are pressing Venezia high up the pitch and have left space to be exploited. Once he receives the ball, the left-back quickly plays to the feet of the centre-forward who has dropped short, dragging his marker.

From there, the players can play some one-touch passing and they are in behind the opponent’s backline.

The main principle that’s necessary to do this is that Venezia leave quite a lot of players deep in the lower areas of the pitch. This invites the opposition to press, leaving space higher up the field to be exploited through quick passing or dribbling.

The Venetian team are currently averaging just 3.02 passes per each possession sequence so far in Serie A this season, which is one of the lowest in the league while also boasting an average direct speed of 1.68m/s, the fourth-highest in the league.

This tells us that Zanetti’s team are very direct. The manager constantly instructs his forward players to attack the depth of the pitch too in order to give options in behind. Sometimes, a simple ball in behind the opponent’s backline will set Venezia through on goal.

Balls from the fullback into a winger running the channel between the fullback and centre-back are a heavily utilised way of progressing play for Venezia under Zanetti too. This is done simply by attracting the opposition’s fullback out to press and slipping it into a runner in behind.

Having players such as David Okereke and Thomas Henry is very useful for doing so as the pair are constantly attacking the depth, stretching the defensive team vertically and latching onto the end of balls in behind due to their rapid speed.

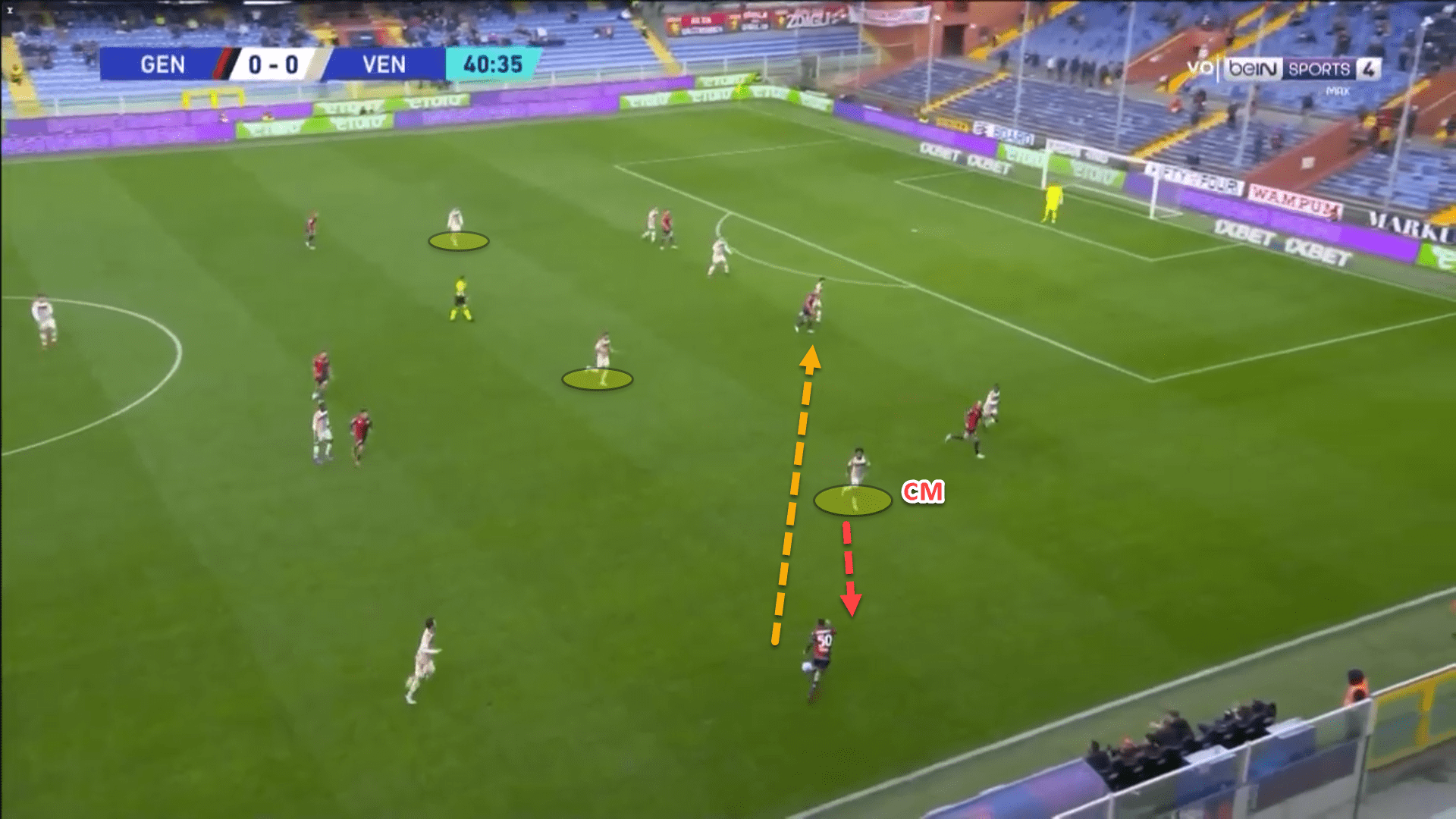

Venezia tend to attack down the wide areas anyway when they are looking to break into the final third in a settled, positional attack. They do this, in a similar fashion as explained in the previous section, by dropping a central midfielder out wide as an auxiliary fullback.

As can be seen in this image, Busio has dropped out wide as a temporary left-back to receive the ball in space. Generally, a normal wide rotation occurs when the midfielder drops wide, the winger pushes into the halfspace and the fullback moves high and wide.

However, Zanetti likes his team to be positionally fluid. In this instance, the left-back is the player in the halfspace while the winger is wide on the left.

Another noticeable aspect from the previous image is that Venezia’s shape when trying to break down a team’s defensive block tends to look like a 3-2-5 although this is not an absolute structure and can change depending on the situation.

Again, their forward players play high and rarely drop short to receive to feet unless applicable. This is because Zanetti prefers his players to play on the shoulder of the last defender.

This is important in order to be as efficient as possible as Venezia struggle with breaking down low defensive blocks and so rely heavily on balls in behind, even during positional attacks.

Sporadic pressing and heavy reliance on midfield

So far, only the possession principles that Zanetti implements into his side have been analysed. Out of possession, the coach takes quite a pragmatic approach in quite classic Italian fashion.

Zanetti does instruct his team to press high when the opponent has the ball in the first third of the pitch. However, this does depend on the opponent on the day. Against lesser teams, Venezia are likelier to press higher than against better opposition.

The Venetian team hold a Passes allowed Per Defensive Action this season of 14.5, which is one of the highest in Serie A. The higher the PPDA, the less a team presses as they allow more passes before intervening with a defensive action.

Generally, Zanetti instructs his players to drop off into their defensive shape instead. If the manager deploys a 4-4-1-1 or a 4-2-3-1 formation, the team will use a 4-4-2 defensive block but if a 4-3-3 is deployed, it will remain as such.

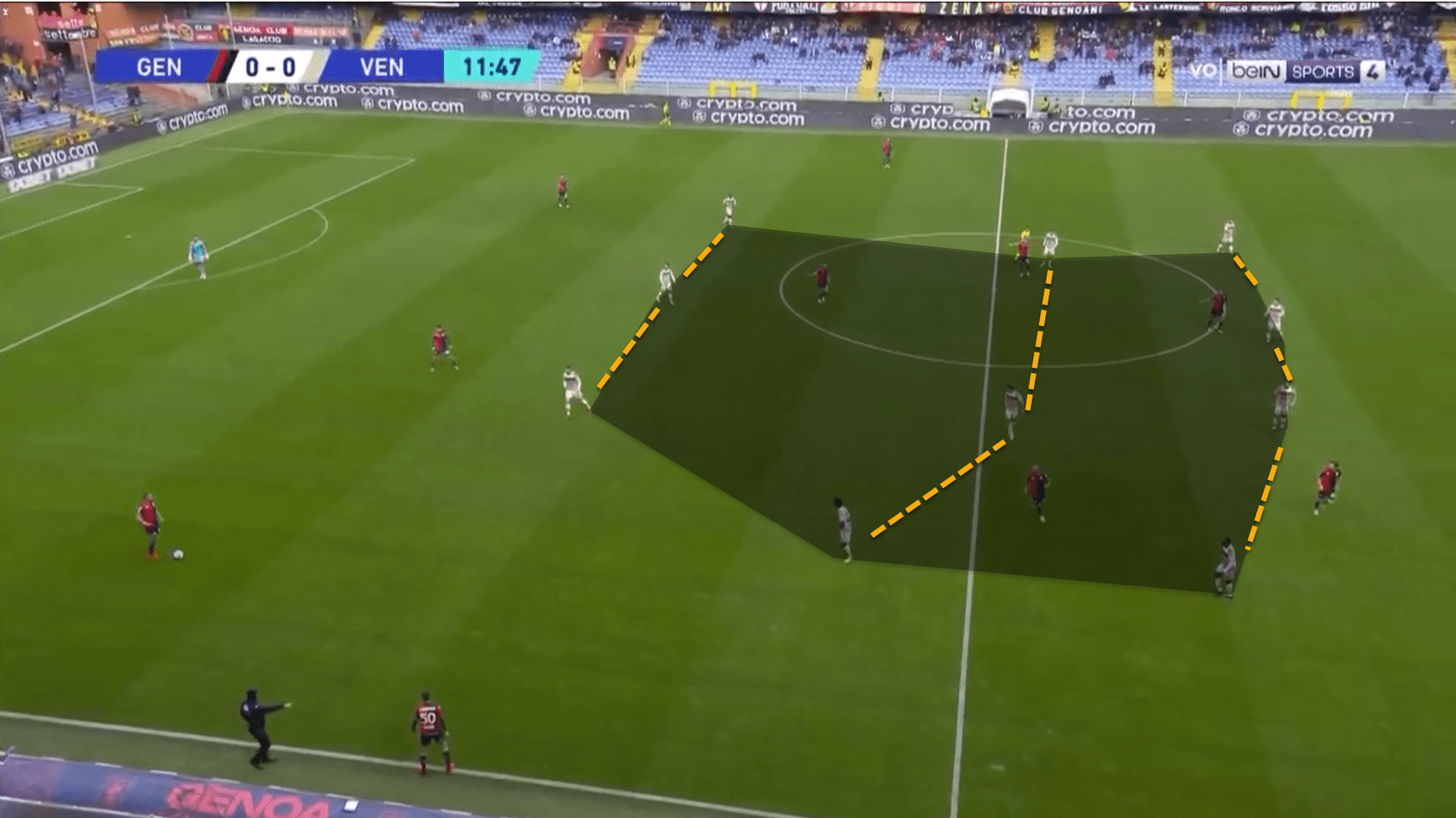

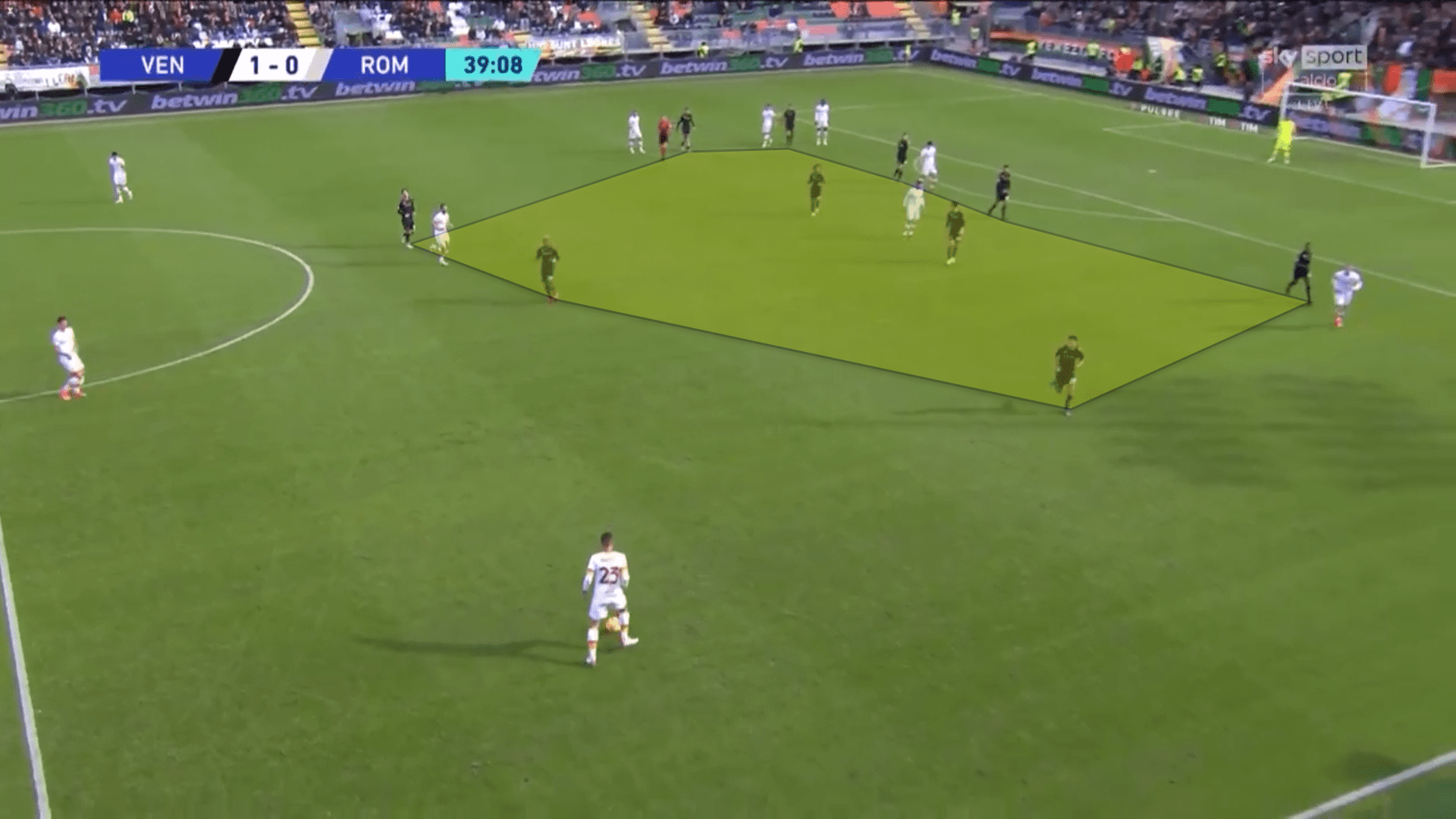

In this instance, Venezia are sitting in a 4-3-3 medium-level block. Zanetti instructs his players to remain compact between the lines and to mark players inside the defensive block.

The newly-promoted side are more than happy to allow the opponent to have possession of the ball in predictable areas and will only engage if the player on the ball poses a threat. Generally, though, they will cede possession and try to cut off passing lanes inside the block to ensure that their structure is not broken.

To deny access inside the block, Zanetti uses a very narrow first line of pressure in their defensive set-up. The objective with this is to ensure that the attacking side cannot play through them and must play to the wide areas instead.

In this example, Venezia have deployed a 4-4-2/4-2-4 out of possession. The space between the double-pivot and front four is extremely compact and so Roma are forced wide to keep moving the ball.

When deploying a 4-3-3, while it may provide extra attacking options going forward and in transition, the shape can be quite problematic for Venezia under Zanetti in the same way that it was for Nuno Espírito Santo at Tottenham Hotspur.

Generally, when a team use a 4-3-3 out of possession, the wingers will drop back as the block moves lower down the pitch to create a 4-5-1 shape. Zanetti, instead, keeps them high and narrow to negate any passes centrally. However, this can sometimes leave the midfield exposed when the first line of pressure is broken.

This is because the midfield must position themselves wider in order to defend the wide areas should the ball get switched. Zanetti is instructing his central midfielders to stay wide enough that they can get across if the ball is switched but also close enough to their teammates so that they can defend the central spaces.

Why don’t they wingers simply drop back? Firstly, it would be more difficult to force them wide, and secondly, Zanetti wants to leave his wingers up high so that they can run in behind alongside the centre-forward during attacking transitions.

In the lower areas of the pitch, Venezia are the second-most active side in Serie A this season in terms of pressures per 90 in their defensive third. Zanetti’s side are averaging 56.7 pressures per 90 in this section of the pitch.

Interestingly, Venezia have the lowest pressure success rate in Italy’s top-flight division with 25%. They have conceded the fifth-highest volume of shots too with 138, as of writing, conceding an xGA of 18.2. In total, this season, Zanetti’s men have conceded 19 goals and so are slightly underperforming their xGA statistics.

Regardless of the shape, the tactical instructions from the manager are to stay compact and deny space between the lines, keep close connections with one another, and force the opposition wide.

Venezia want to ensure that the attacking side have the ball in harmless areas of the pitch, generally in front or beside the low block.

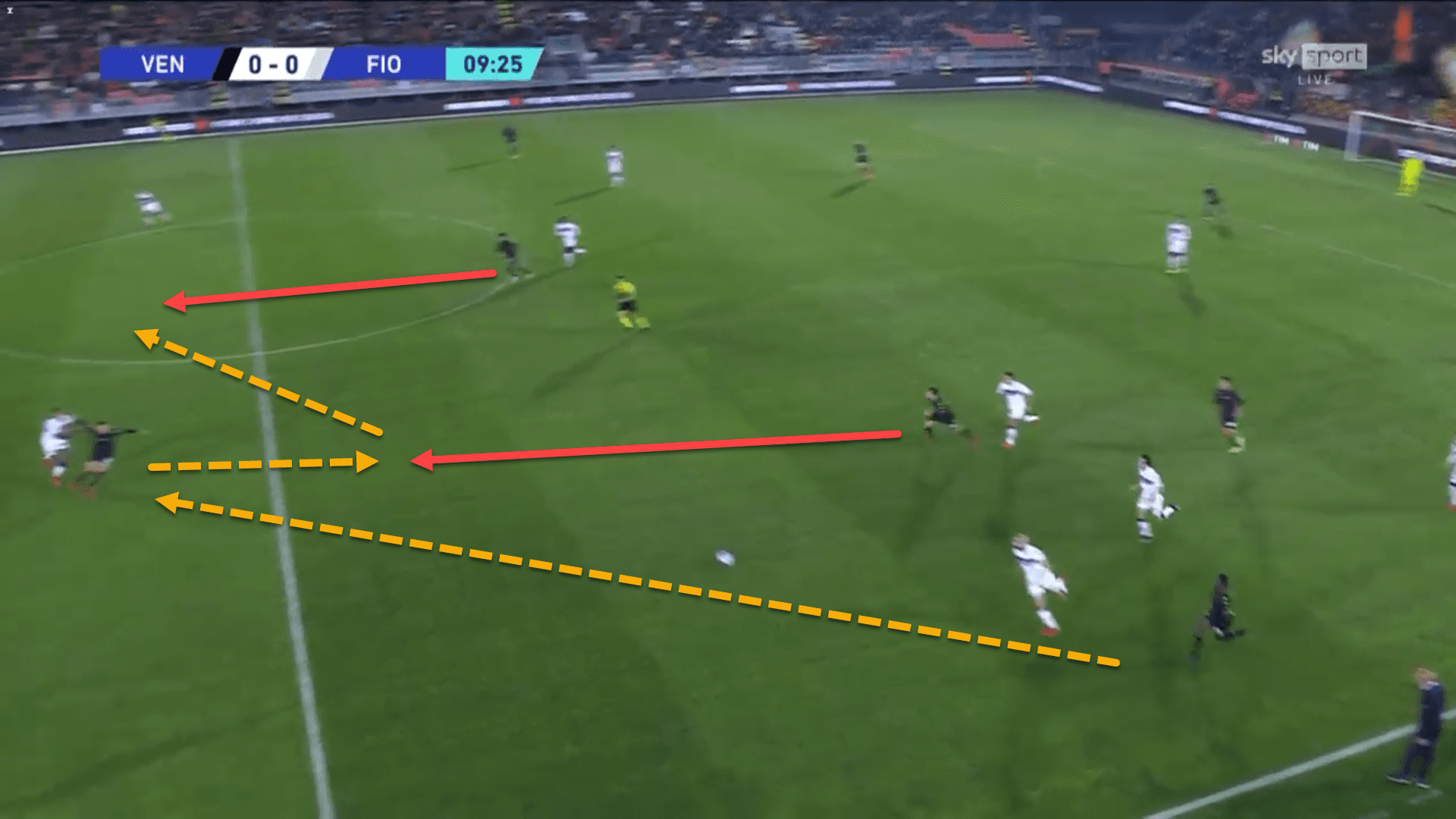

In a 4-3-3 though, as the wingers are not tracking back to help the fullback, the ball-near midfielder must come across, but this leaves space centrally which can cause them issues in the final third.

Here, the ball has been switched to the attacking right flank. The nearest midfielder for Venezia has shifted across to defend against the ball-carrier. However, this has stretched Venezia’s midfield and made it easy for the player in possession to play to the feet of the frontman in the final third.

Conclusion

In possession, Zanetti sets his side up to defend in instances where the ball is lost while out of possession, the coach ensures that his team are ready to attack. These principles can sometimes be detrimental, but he sticks with his beliefs and they have been proven to be successful thus far.

While Venezia are looking likely to be in a relegation dogfight this season, they are still entertaining and have been playing a wonderful brand of football, which is a credit to the 39-year-old coach. He is certainly one to keep an eye out for in the future regarding the next great football coaches.

Comments