Paraguay suffered their first loss of Copa América 2021 in their second group game when they came up against one of South America’s big three – Argentina, who have won two and drawn one of their first three group games at this year’s competition. Despite being the second most successful side in Copa América history, Argentina are currently on something of a drought, having failed to win this tournament since 1993. That is still more recent than Paraguay have lifted the trophy, however, with La Albirroja last winning Copa América in 1979.

This week’s meeting between these two sides was a tight affair that ended in a 1-0 win for Argentina. Neither side looked particularly convincing going forward in this one, which can partly be credited to each team’s solid defensive efforts, however, Paraguay undoubtedly created fewer quality chances than Argentina, who enjoyed the luxury of being able to rely on moments of brilliance from La Liga giants Barcelona’s Lionel Messi and Ligue 1 side PSG’s Ángel Di María at times.

Paraguay kept more of the ball, ending the game with 53.25% possession to Argentina’s 46.75%, but La Albirroja managed to create just eight shots with one hitting the target, while La Albiceleste created nine shots with five hitting the target.

In this tactical analysis piece, we’ll look into Paraguay’s creative issues versus Argentina. We’ll highlight some areas in which they struggled on the ball during this Copa América fixture, while we’ll also provide analysis of what Paraguay tried to do in this game and how they ultimately failed to execute their tactics and plans effectively.

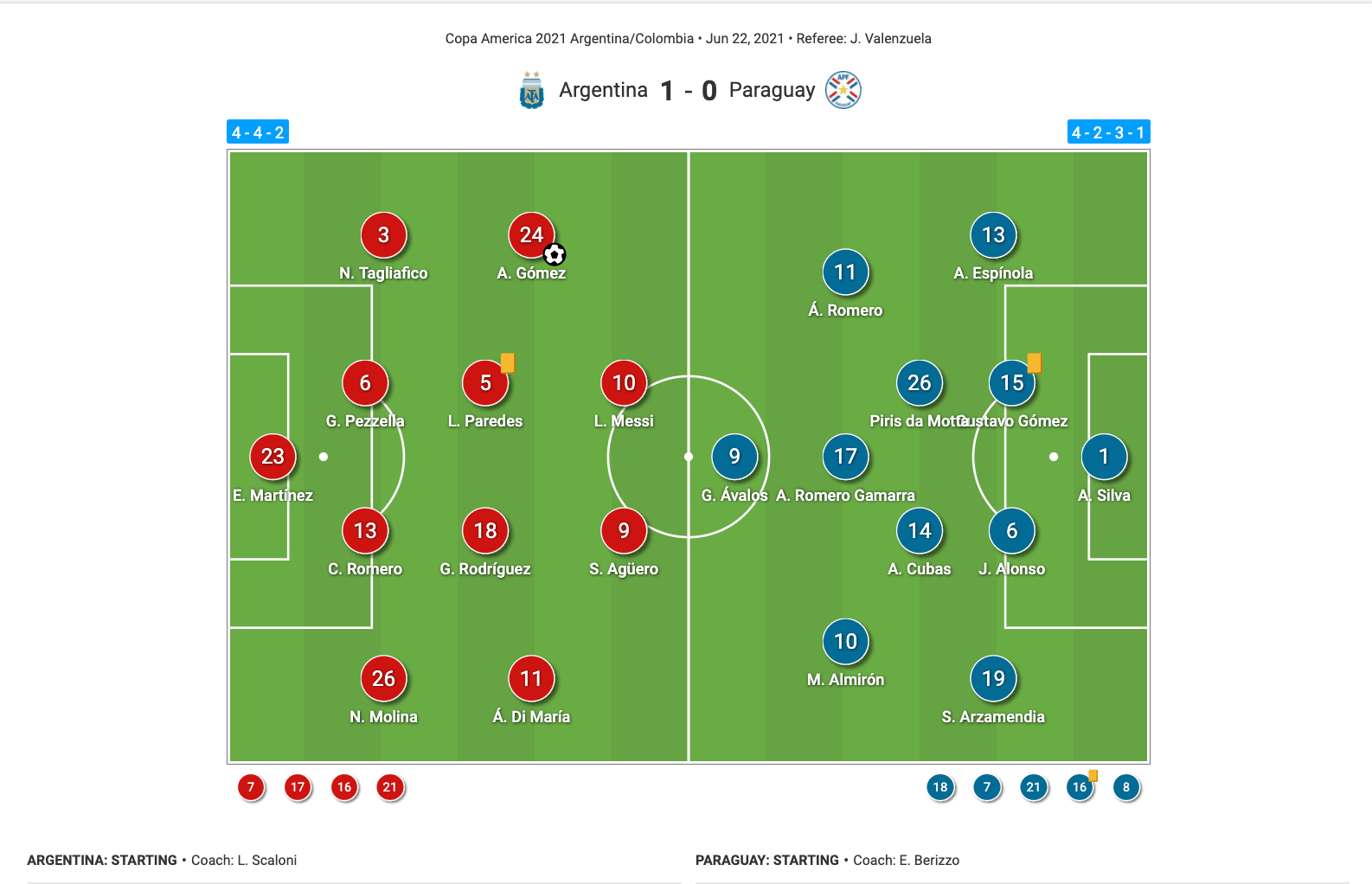

Lineups and formations

Firstly, let’s run through both teams’ lineups and formations for this fixture. Argentina lined up in a 4-4-2 shape for this one, with Messi sometimes dropping deeper to become a ‘10’ in a 4-2-3-1, and Argentina pressing higher in more of a 4-2-2-2. In their 4-4-2 shape, Lionel Scaloni’s team lined up as followed in the corresponding positions:

GK: Emiliano Martínez, RB: Nahuel Molina, RCB: Cristian Romero, LCB: Germán Pezzella, LB: Nicolás Tagliafico, RM: Ángel Di María, RCM: Guido Rodríguez, LCM: Leandro Paredes, LM: Alejandro Gómez, RCF: Lionel Messi, LCF: Sergio Aguero.

Joaquín Correa was Argentina’s first substitute, he replaced Agüero in the 59th minute. Rodrigo De Paul came on in place of Gómez in the 72nd minute, while Nicolás Domínguez and Ángel Correa were introduced in place of Paredes and Di María in the 81st minute as Argentina’s final substitutes.

Meanwhile, Paraguay lined up in a 4-2-3-1 shape, which often changed into a 4-1-4-1 when pressing higher. In their 4-2-3-1 shape, however, Eduardo Berizzo’s team lined up as followed in the corresponding positions:

GK: Antony Silva, RB: Alberto Espínola, RCB: Gustavo Gómez, LCB: Júnior Alonso, LB: Santiago Arzamendia, RDM: Robert Piris Da Motta, LDM: Andrés Cubas, RW: Ángel Romero, AM: Alejandro Romero Gamarra (Kaku), LW: Miguel Almirón, CF: Gabriel Ávalos.

Paraguay made their first couple of substitutes in the 66th minute, as Óscar Romero and Ángel Cardozo Lucena replaced Kaku and Cubas, respectively. Then, Richard Sánchez came on in place of Piris Da Motta in the 82nd minute, before lastly, Braian Samudio and Carlos González Espínola were introduced in place of Ávalos and Ángel Romero in the 87th minute.

Paraguay’s press

Paraguay pressed very aggressively in the high-block phase versus Argentina consistently throughout this game. They ended the contest with a PPDA of just 5.72, which was far lower than Argentina’s PPDA of 11.86 – also not a very high PPDA – highlighting just how aggressively they pressed their opponents in this one, allowing them very little time on the ball before engaging them with a defensive action (defensive duel, interception, or tackle).

La Albirroja made 60 ball recoveries, in total, during this game. 11 of them were made high up the pitch, with 30 coming in the middle of the pitch and 19 of their recoveries coming in the lower third of the pitch. So, the majority of Paraguay’s ball recoveries came in the high and middle third of the pitch, with as many as 18.3% coming in the higher third. In contrast, Argentina made 65 recoveries versus Paraguay, with just six coming in the higher third, 22 coming in the middle third and 37 coming in the lower third. So, while Argentina did also press Paraguay quite high, they generally won the ball back in lower areas far more frequently.

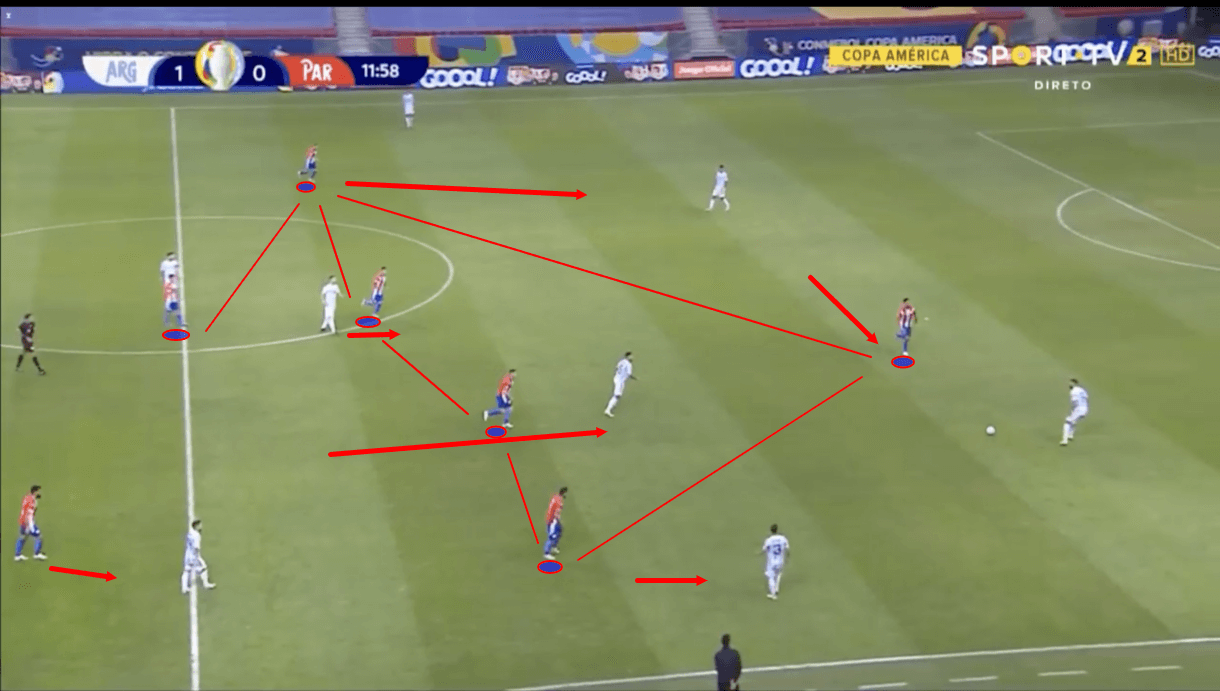

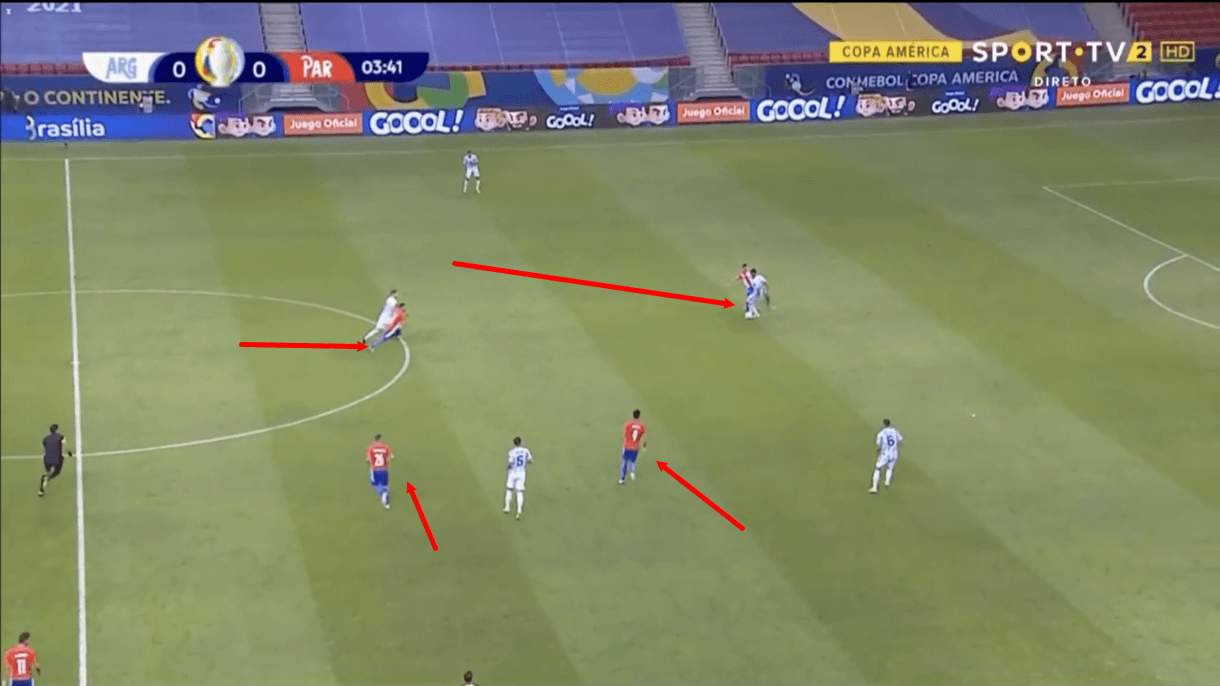

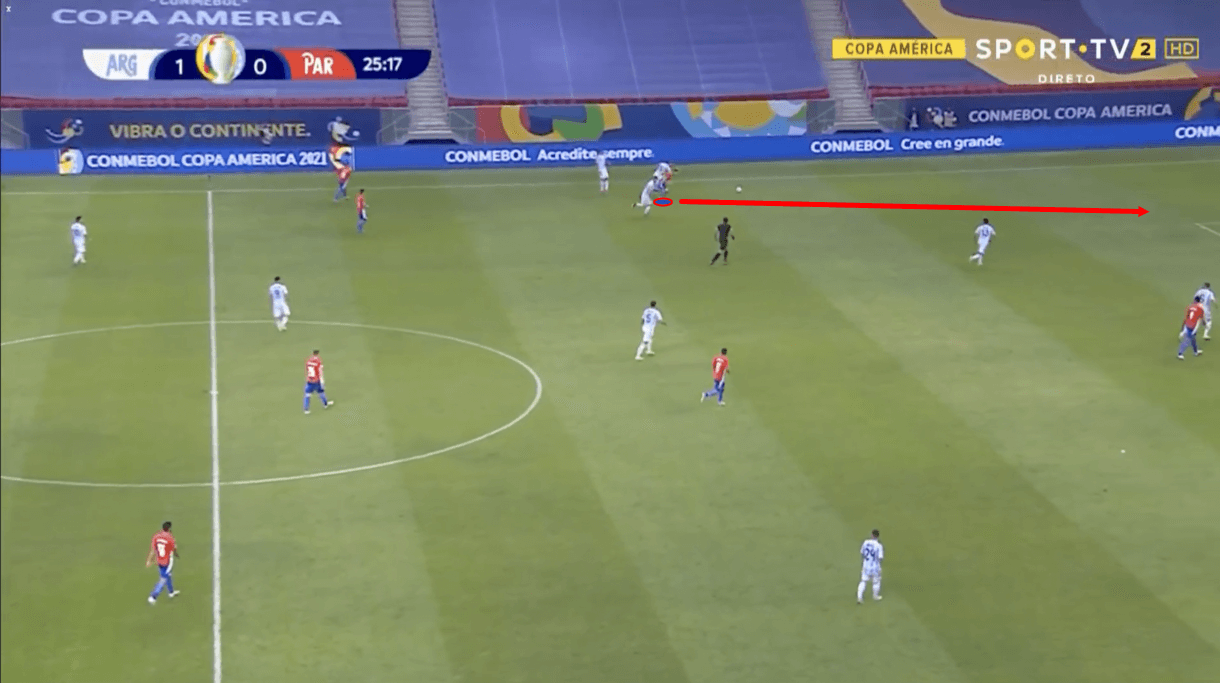

As mentioned previously, when pressing higher, Paraguay’s shape tended to shift from a 4-2-3-1 into a 4-1-4-1. We can see an example of this 4-1-4-1 shape in figure 2. To form this shape, Piris Da Motta tended to push into a more advanced position, joining Kaku, Romero and Almirón behind Ávalos. This left Cubas as their sole holding midfielder. This change in shape which saw Paraguay commit more bodies higher up the pitch highlights how La Albirroja emphasised winning the ball higher.

Additionally, Paraguay’s decision to play a 4-1-4-1 during this phase of play prevented Argentina from building out easily thanks to having a 2v1 overload versus Paraguay’s ‘10’ with their two central midfielders, as now Paraguay could match them man-for-man here. We can see how they achieved this in figure 2. Throughout this game, Da Motta and Kaku tended to stick very tight to Argentina’s midfield duo in the high-block and mid-block phases, with Cubas either being an extra man covering behind in case they were beaten or picking up Messi if he dropped into a ‘10’ position.

Meanwhile, Paraguay’s near-sided winger would mark the opposition’s near-sided full-back tightly and centre-forward Ávalos cut the pitch in half, positioning himself between the centre-backs and preventing them from being able to directly pass to one another. In this position, Ávalos tended to press the ball-carrier aggressively while keeping the other centre-back in his cover shadow.

The far-sided winger, then, would not stick quite as close to the opposition full-back as the near-sided winger would. He remained somewhat compact with his midfield teammates who would shift to the ball-near side as Paraguay aimed to congest space around the ball-carrier, and was prepared to press the ball-far centre-back should the opposition either try to switch to him through another player, such as a central midfielder or the goalkeeper.

This was the case as figure 2, above, moved on. Just before this image, Argentina’s left central midfielder passed to the left centre-back. He couldn’t then pass to the left-back or return to the left central midfielder, as they were marked tightly, while he was also prevented from playing the ball across to his central defensive partner because of Ávalos’ press and intelligent positioning. This left the goalkeeper as the only viable short passing option who could have space to progress the ball. This is a scenario that Paraguay set up for Argentina to press high and try to regain possession.

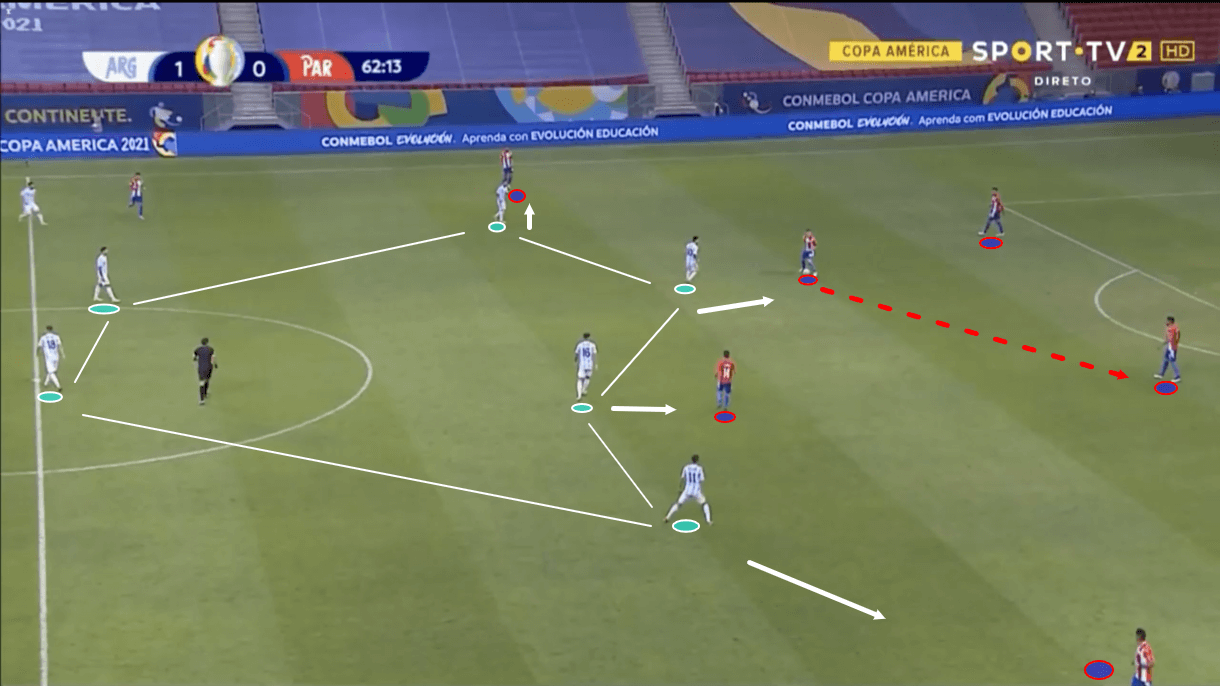

As this passage of play moves on, then, into figure 3, we see how Paraguay’s high block advanced further, following Argentina shirts as they dropped deep and ensuring that no short passing options opened up for the ‘keeper. It’s worth noting how left-winger Almirón, in particular, didn’t press the right-back but instead got closer to the right centre-back to make that short pass a risky one, while intelligently using his body to block the short passing lane to the right-back.

As play moves on, Argentina’s goalkeeper is forced to go long to the right-back, who attracts pressure from Paraguay’s left-back. The Argentinian player fails to control the long ball and Paraguay ultimately force a turnover quite high up the pitch.

This is an example of Paraguay’s pressing tactics and how they were effective, at times in this game. However, while Berizzo set his side up really well to force high turnovers in dangerous positions, and Paraguay’s players were extremely active and energetic during this phase to implement the manager’s vision, they ultimately failed to take advantage of the positive scenarios that their high press created.

This was partially due to how they used the ball, and the quality of chances that they ultimately did create, which we’ll come onto later in this tactical analysis. This was also due in part to the fact that some of their tackling wasn’t good enough, which let them down when opportunities to win the ball high in dangerous situations presented themselves.

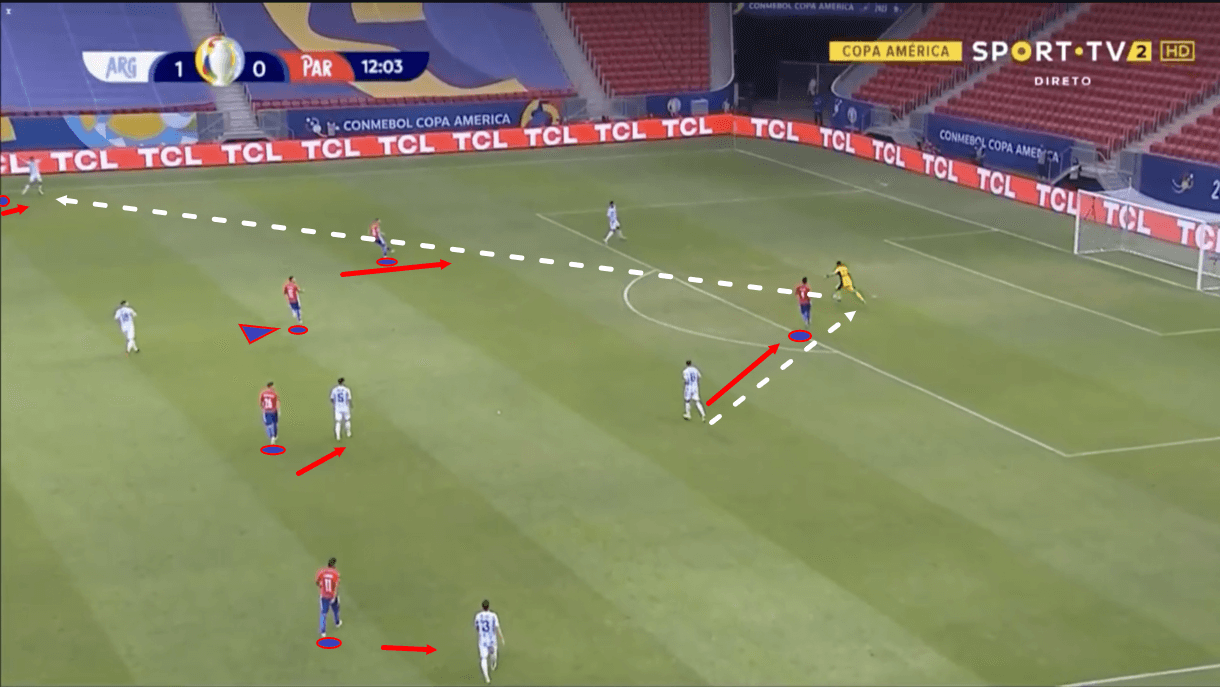

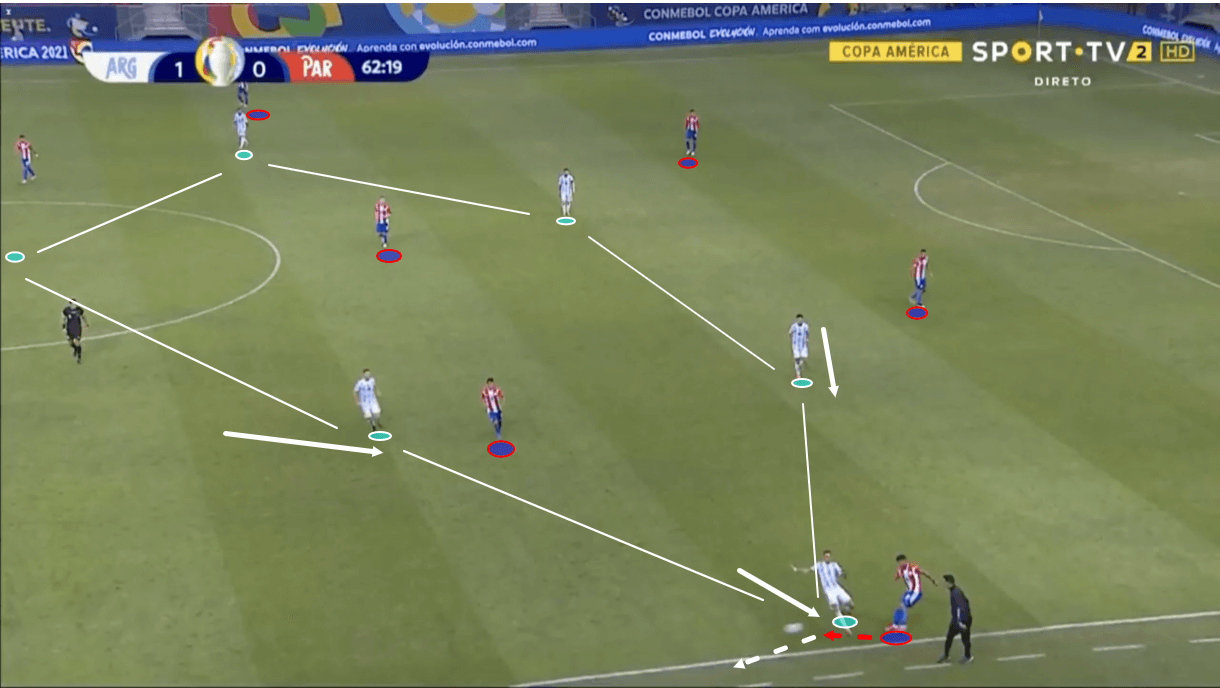

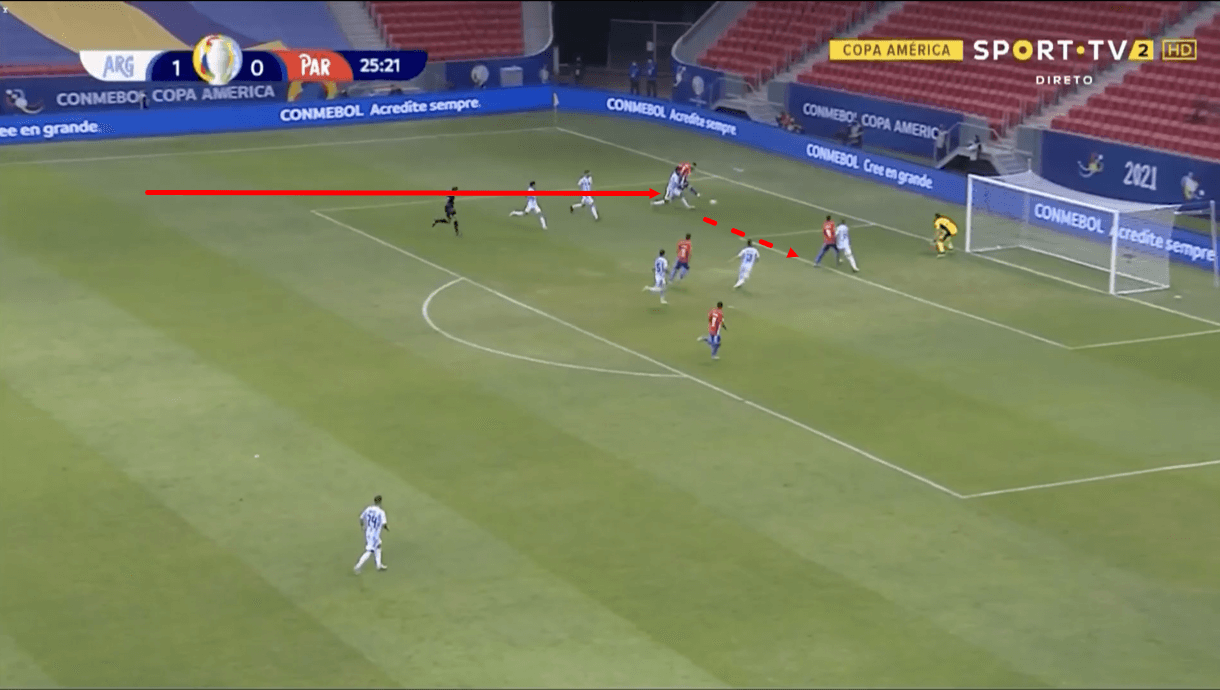

For example, figure 4, we see another instance of Paraguay pressing Argentina high in their 4-1-4-1. This time, just before this image, the left centre-back passed the ball to Argentina’s left central midfielder. This immediately attracted pressure from Piris Da Motta, who prevented the player from turning and forced him to play the ball quickly to the only open man – Argentina’s right centre-back. As we know, this pass then attracted pressure from Almirón.

Almirón’s press was quick and he successfully got in position to win the ball from the right centre-back, whose first touch was slightly strong. As we see in figure 5, this is exactly the kind of scenario Paraguay would have hoped to create while putting together this game plan. However, the execution let them down. Almirón’s tackle wasn’t strong enough, he only managed to clip the ball, which essentially gave Argentina’s centre-back a second chance to recover by going in for the second ball stronger, and as play moves on, Argentina manage to get themselves out of jail with some quick passing.

This kind of situation occurred multiple times in this game. Paraguay had the structure and energy to set up really good pressing situations that could have led to a good goalscoring opportunity, but the quality of their tackling let them down. Paraguay wanted to create counterattacking chances high up the pitch but, unfortunately for them, the game ended with 0 counterattacks for both sides. This wasn’t through a lack of planning on Berizzo’s part or a failure to implement a good pressing structure, they just failed to execute their plan effectively through a lack of technical tackling quality or a lack of physicality in challenges.

Paraguay’s progression struggles

As a result of their failure to create counterattacks, a lot of Paraguay’s attacking efforts were focused on positional attacks, of which they created 37 in this game to Argentina’s 20. However, both teams had five positional attacks each resulting in shots at goal, so it’s clear that Argentina were more effective than Paraguay in this area. One reason that Paraguay had so much possession and so many positional attacks in this game and ultimately had little to show for it was that they struggled to progress past Argentina’s solid mid-to-high block.

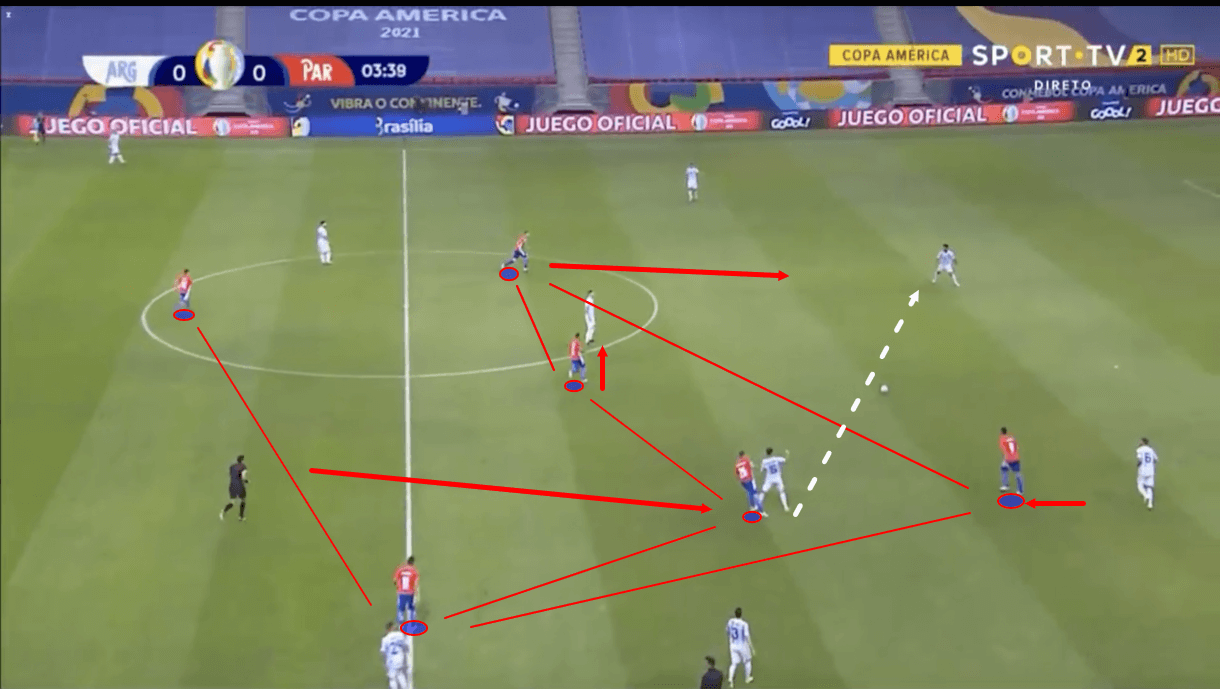

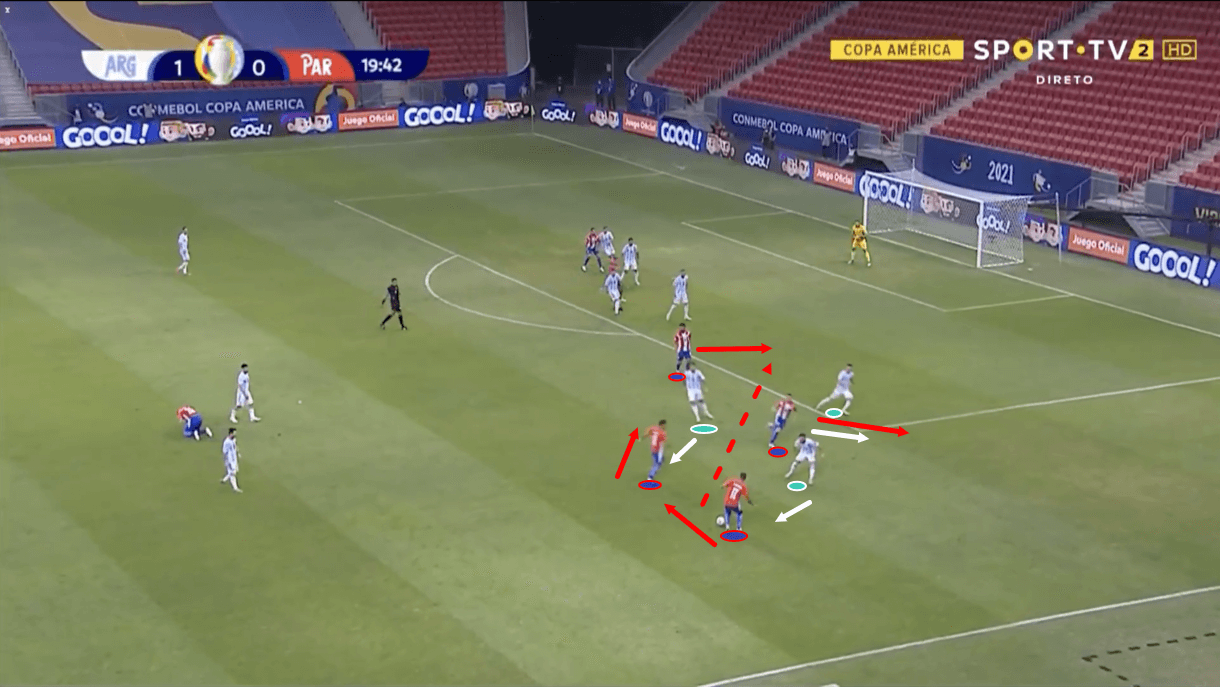

In build-up, Paraguay generally created a 2-4-1-3 shape, with the full-backs advancing in line with the holding midfielders, as is typical in possession phases with the 4-2-3-1. Argentina, meanwhile, tended to press high in a 4-2-2-2, with the centre-forwards and central midfielders occupying virtually the same vertical lines, and the wingers sitting wider while positioned about midway between the other two lines.

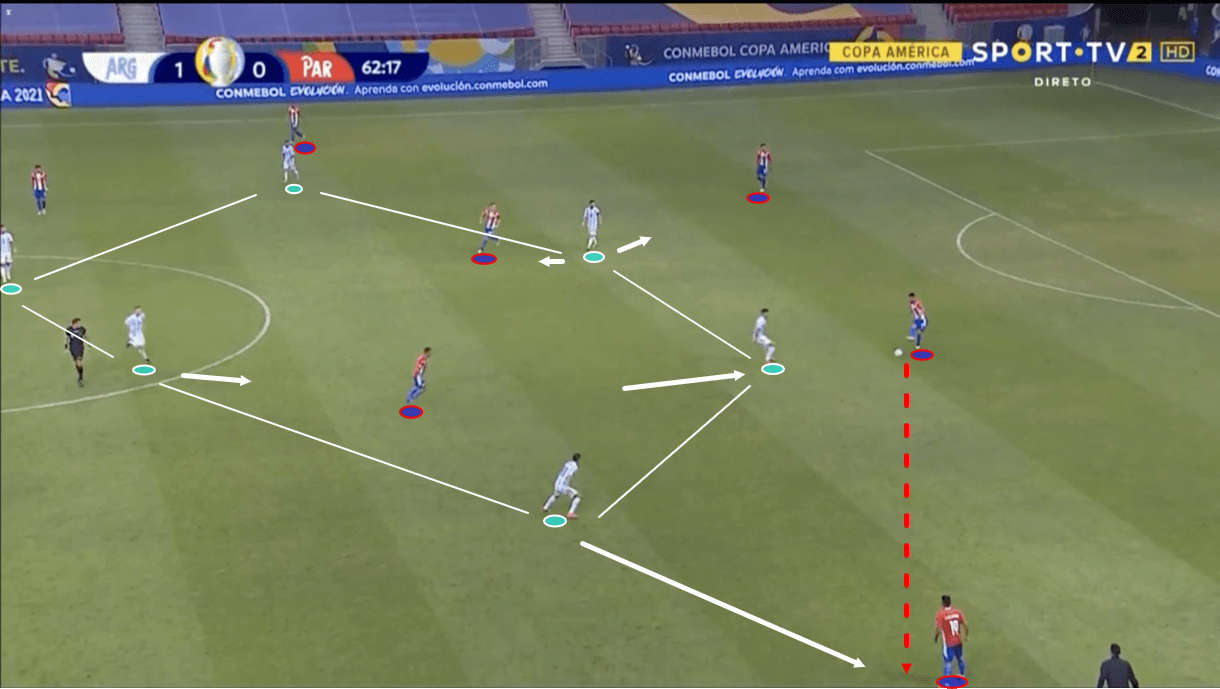

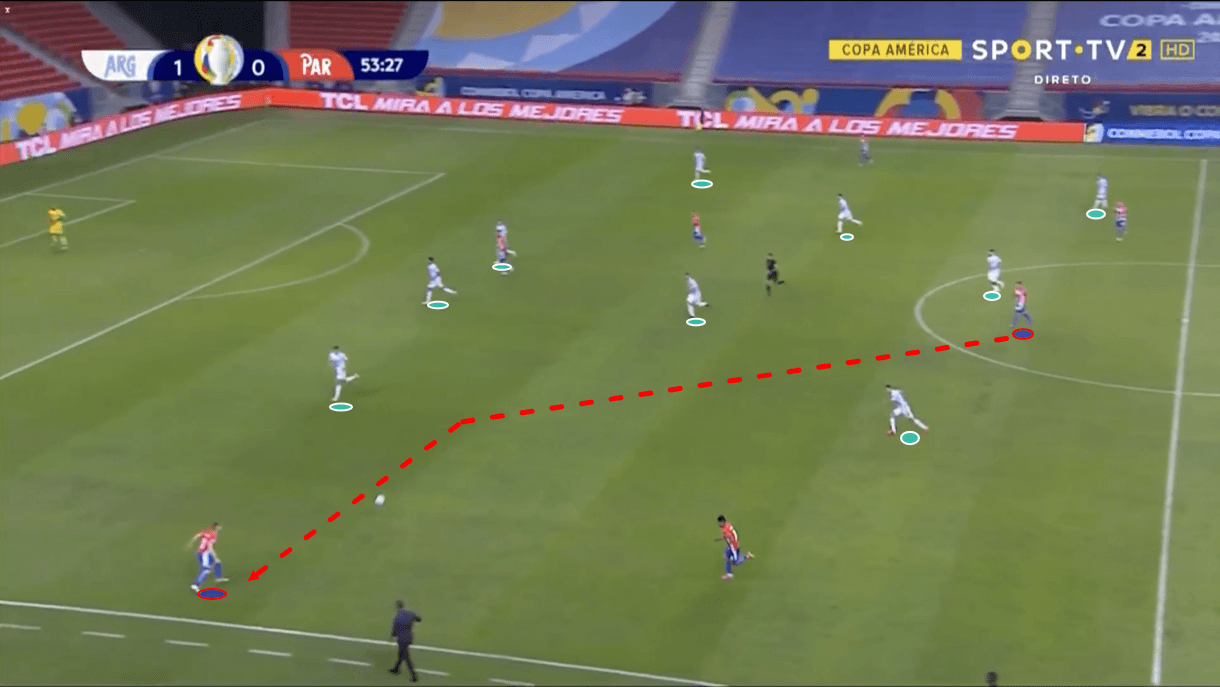

For the most part, Paraguay found it very difficult to progress past Argentina’s high block during this game and we’ll analyse one passage of play which highlights some of the reasons for this here, starting with figure 6, above, which shows both teams in the shapes we discussed previously, though Argentina’s centre-forwards are slightly deeper than normal here, resulting in more of a 4-2-4 shape forming.

Just before this image, the ball was played to Paraguay’s right holding midfielder. Often when these players received the ball in this game, they were prevented from even turning due to pressure from behind, but in this case he did manage to turn, but he still had plenty of pressure from Messi and limited passing options ahead and to the side. Argentina limited the Paraguay midfielders’ forward and sideways passing options, resulting in a lot of passes being played just between these four central players at the base of Paraguay’s attacking shape.

This can happen to teams simply because of the nature of this shape which sees sets two of two players occupying the same vertical and horizontal lines, and Argentina’s press exploited this very well by preventing the midfielders from advancing much on or off the ball through their positioning and aggression. The Argentina press effectively stranded these four Paraguay players in their base positions for large portions of the game and Paraguay struggled to adjust and get past that pressure.

As this passage of play above moves on, the right holding midfielder passes back to the left centre-back. This was a common sight that highlighted how effective Argentina’s press was at limiting Paraguay’s ball progression.

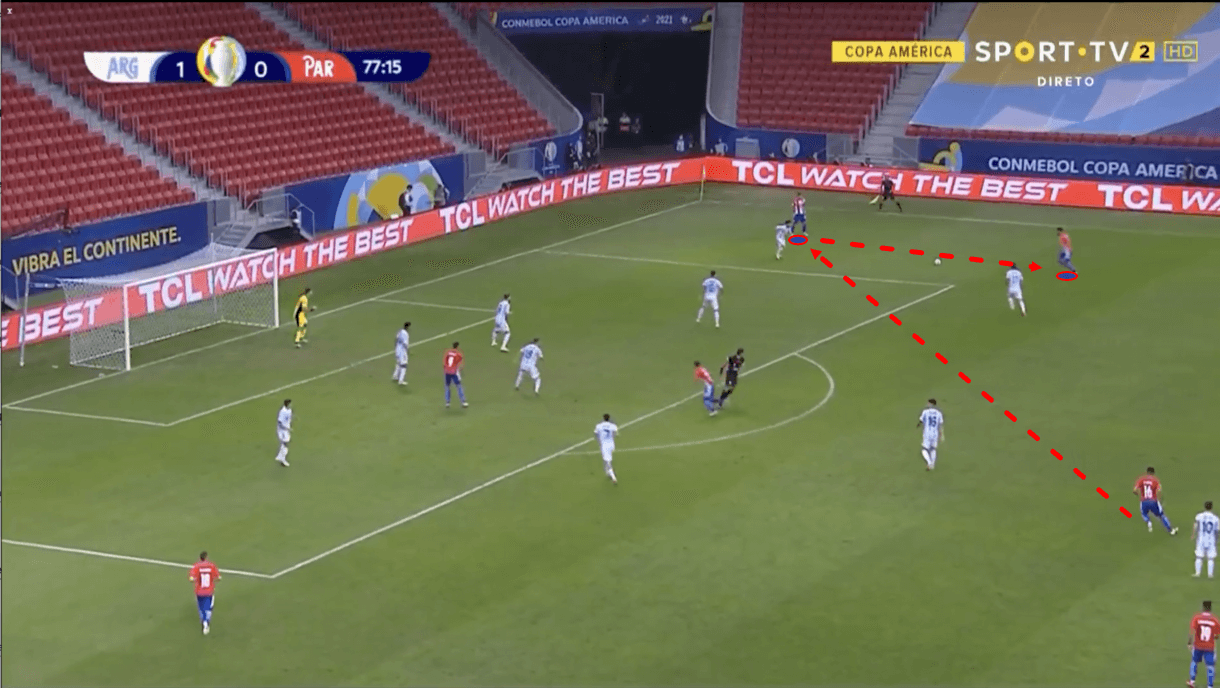

As figure 7 shows, when the ball went back to the left centre-back, Argentina’s right centre-forward advanced past the central midfielder he was marking and closed down the ball-receiver, while the left centre-forward also advanced to get in line with his centre-forward partner. Now we see Argentina’s 4-2-2-2 shape and how effective it was at preventing Paraguay from progressing out of their own third.

The ball-near centre-forward closed down the ball-carrier while keeping the ball-near holding midfielder in his cover shadow, the ball-far centre-forward was in position to press the other centre-back if he was the intended recipient of a pass, while he also retained access to the ball-far holding midfielder, and Argentina’s ball-near winger began pressing Paraguay’s ball-near full-back, who was now the only viable lateral short passing option.

This was Paraguay’s most common passing combination throughout the game. The ball moved between Alonso and Arzamendia a total of 25 times, which highlights how common it was for Argentina to force La Albirroja into this unfavourable situation through their pressing.

Paraguay could, theoretically, try to play the ball into central midfield through Arzamendia with Argentina in their 4-2-2-2 shape like this. It would be easier with the near centre-forward more advanced after pressing the centre-back and the winger pulled out wide, however, as this play moves on, we see arguably the most important aspect of Argentina’s high block come into play – the shift from a 4-2-2-2 into a 4-1-3-2.

Simply put, Argentina’s ball-near central midfielder always had the freedom to advance into the next line to provide cover for the winger and centre-forward by marking Paraguay’s near central midfielder. This was extremely effective at preventing the ball from moving between Arzamendia and the left central midfielder – usually Cubas. On a couple of occasions, the pass was still played into Cubas in situations like this, however, on those occasions, the Argentina midfielder successfully prevented his opponent from turning and this either forced Paraguay backwards again or led to a turnover through Argentina’s pressing trap.

As this passage of play moves on into figure 8, we see that Arzamendia ended up resorting to trying to play the ball up the line and his pass was intercepted, with the ball ultimately going out of play on this occasion, resulting in a Paraguay throw-in, so not the worst result, however, it does show how Paraguay’s ball progression was stifled. Sometimes, Arzamendia tried to play the ball down the line to left-winger Almirón here, however, like Cubas, he was marked tightly from behind by an Argentinian shirt – this time the right-back, resulting in similar ball progression breakdowns.

Passages of play like this one were a relatively common sight during this game and this highlights how Argentina’s organised press in the high block successfully stifled Paraguay’s ball progression.

Paraguay’s crossing

La Albirroja relied heavily on crossing from wide areas via the full-backs and wingers to get into Argentina’s box when they did manage to progress into the final third. They ended up attempting a total of 21 crosses in this game. However, Paraguay’s crossing was largely ineffective, as they managed to play just six accurate crosses versus La Albiceleste.

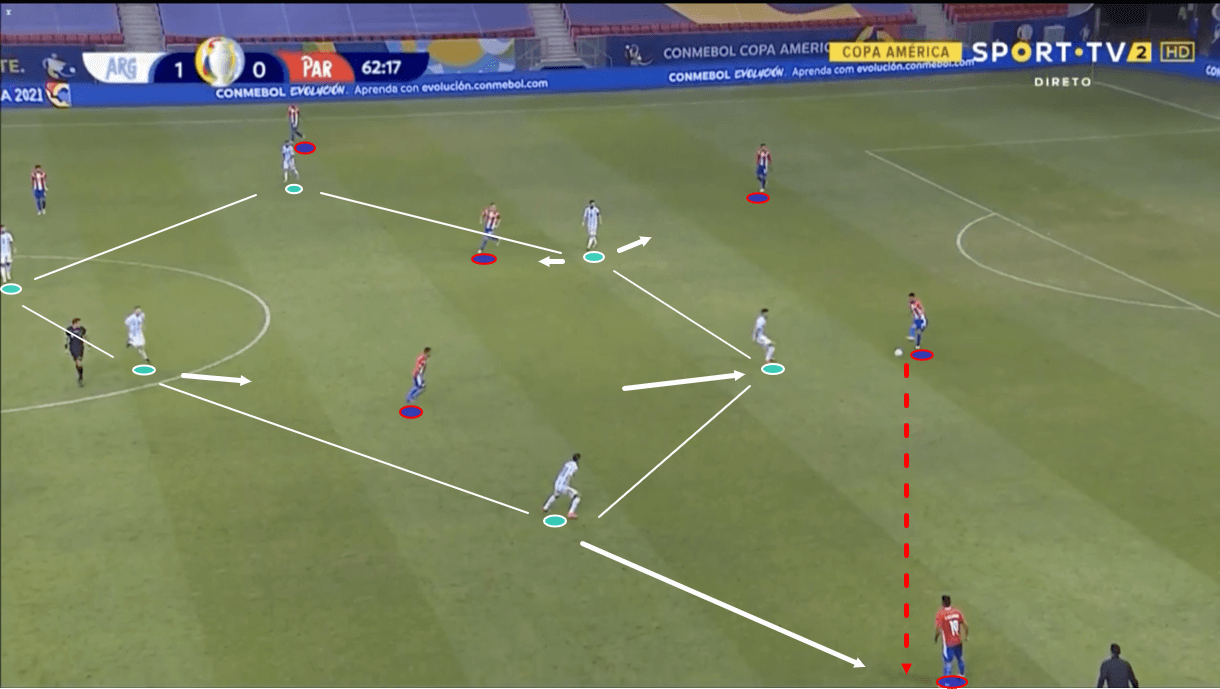

As seen in figure 9, Almirón and Romero on Paraguay’s wings tended to stay very wide during ball progression. This was good positioning as Argentina’s defensive shape tended to get very narrow in deeper areas, so these creative players had a lot of space to operate in when found via Cubas and Piris Da Motta’s long balls from the centre, and they could stretch the opposition backline.

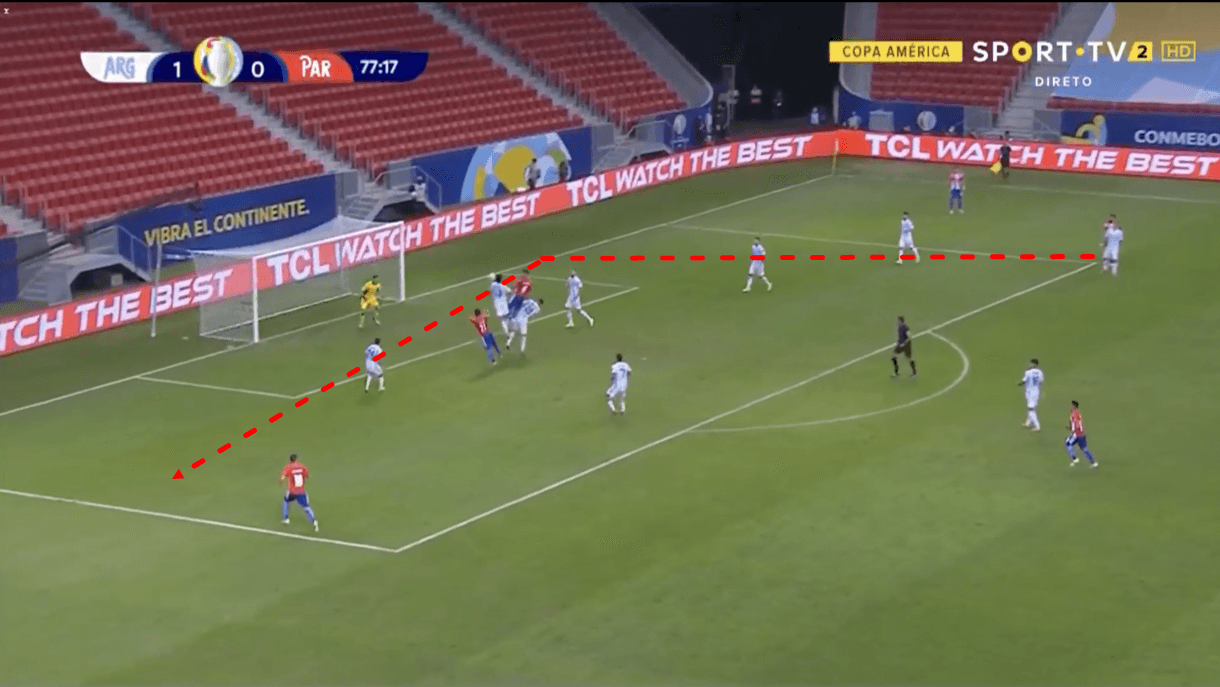

Paraguay’s right-winger was on the receiving end of a long, crossfield ball from the centre just before figure 10. Then, this player attracted pressure before he linked up with the right-back who ventured forward from deep in support. The winger laid the ball off for the right-back, who then sent a cross into the box.

However, as the play moves on into figure 11, we see that this cross failed to trouble Argentina too much, with the ball missing the Paraguayan targets before falling to Almirón on the left wing, who took a shot on from a less-than-ideal position, with the ball ultimately going wide.

Paraguay’s crosses, in general, were aimed at centre-forward Ávalos, however, Argentina were well able to deal with his threat, as firstly, Paraguay had very few other aerial threats so could concentrate more on dealing with Ávalos directly from the cross, and secondly, Argentina tended to pack the penalty box full of bodies to outnumber the attackers and make it more difficult for them to find space and take advantage of the cross.

Argentina’s centre-backs tended to double up on Ávalos, as was the case in figure 11 above, outmuscling him and usually outjumping him, with Ávalos failing to threaten via his jumping reach. As the ball fell to Almirón, multiple Argentina bodies got in position to block the shot and reduce his threat, however, with the shot coming from a poor angle, Almirón failed to hit the target anyway. It was common to see Argentina’s defenders deal with Paraguay’s crossing threat swiftly and effectively like this before crowding players around the attacker and in front of goal to block the incoming shot.

La Albirroja snatched at opportunities like the one Almirón got here, where the shot would come from a bad angle or from long-range, often after a cross that had been headed away by Argentinian defenders. This played a part in the quality of Paraguay’s chances not being very good in this game, but all Argentina really had to do was deal with Paraguay’s cross attempts effectively, and then Paraguay seemed to have few other ideas. Argentina successfully packed the box, limited Ávalos’ threat and limited Paraguay’s attacking options.

Paraguay did create a couple of more threatening chances in this game, however. These chances were different to the usual ones which were far more like the passage of play we analysed in figures 10 and 11 and may highlight how La Albirroja could have gotten more from this game. As mentioned previously, Almirón and Romero tended to enjoy a lot of space when they received the ball out wide while Argentina were defending deeper. These players struggled to impact the game via their crossing versus Argentina, but are both very good dribblers. They didn’t take on many lengthy dribbles in this game, but when they did, they showed some promise.

In figure 12, we see an example of Almirón taking the ball past Argentina’s right-back, who was pulled out wide to close space around the winger just before this image. He knocked the ball around the right-back and ran past him on the other side, before carrying the ball all the way into the Argentina box.

This led to the crossing opportunity we see in figure 13, but this crossing opportunity isn’t one of the wide, floated crosses we saw in figures 10 and 11, but more of a short, low cutback. This made more Paraguay players threats, as while Paraguay don’t have many aerial threats, plenty of their players can score from chances like this. However, La Albirroja didn’t create enough of these chances. They usually didn’t attack Argentina’s box as quickly as this by carrying the ball upfield through the likes of Almirón and Romero, so generally faced a more compact and structured defence.

Again, this could come back to their failure to create any counterattacking opportunities through their pressing, but ultimately, the chances they created were ones that Argentina were well prepared to deal with.

Additionally, while Almirón and Romero stretched Argentina’s defence, creating space in central positions like the half-spaces, Paraguay failed to occupy these positions or really take advantage of that space enough.

Figure 14 shows one of the few occasions where they did create via the half-space, via Romero, and this was one of their best chances versus Argentina. Romero cut inside, while his teammates’ movement dragged Argentina defenders away, opening up a passing lane through to a teammate in the box. The resulting shot from this attack was blocked, but this highlights how Paraguay did threaten Argentina via the half-spaces, similar to how they threatened via a shorter cross following an Almirón dribble, but these types of attacks were few and far between in this one, even though their crossing was much less effective and that played a big part in their creative struggles versus La Albiceleste.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis of Argentina’s 1-0 win over Paraguay, it’s clear that both teams had some solid defensive tactics in the high-block, which led to both sides’ build-up being stifled, however, Paraguay failed to take advantage of the dangerous attacking opportunities that their pressing threatened to create, while Argentina’s effective defending in the high block also played a big part in Paraguay’s creative issues.

Meanwhile, the chances that Paraguay did create just failed to threaten Argentina and while Almirón and Romero showed some creative promise in different scenarios, these scenarios were rare and that ultimately led to La Albirroja failing to threaten the opponent as much as they really had to.

Comments