Parma are currently sat second in Serie B, following an undefeated start to the season. Current head coach Fabio Pecchia led Parma to a 4th place finish in his first season with the club and narrowly lost in the semifinals of the playoffs to return to the Serie A. The ex-assistant coach of Rafael Benitez at the likes of Real Madrid and Napoli will be looking to achieve instant promotion back to the top flight at the second time of trying.

Although Parma haven’t scored from any set plays in the league yet, they have had some interesting ideas with their short corners and deserve praise for their ingenuity. Parma have displayed a good understanding of using third-man runs to find a free player inside the penalty area from corners, although they have struggled to have many shots from these interesting set plays.

In this tactical analysis, we will look into the tactics behind Parma’s offensive set plays, with an in-depth analysis of how their main corner routine has been used. This set-piece analysis will examine why this routine has had some encouraging signs, why it hasn’t been effective yet, and the steps Parma can take to become more threatening from set plays whilst maintaining their current methods.

Finding the Spare Man

The most common method for defending against short corners involves opposition teams sending out enough players to go man-to-man with the potential receivers of the pass. However, this often results in the corner taker being unaccounted for, with the norm being that once the corner is taken, the player taking it is immediately offside and won’t impact the upcoming sequence. The immediate surroundings around the corner flag is the only area on the pitch where an opposing player can’t start.

As a result, the player by the corner flag can begin with space, where they have a more straightforward job of receiving the ball away from any defenders. As seen in the example below, two defenders are ready to press the short corner, but no one is left to defend against the player taking the corner, meaning he can be labelled as the spare man.

One way in which Parma have attempted to create further space for the players receiving a short pass includes using screens inside the penalty area on the nearest defenders who can potentially close down the short corner. Blocking the defenders from closing down the short corner gives each player the time and space they need to execute their actions. Furthermore, preventing a defender from moving can keep the offside line closer to goal, which makes it easier for the corner taker to move into an onside position and be available to receive the pass.

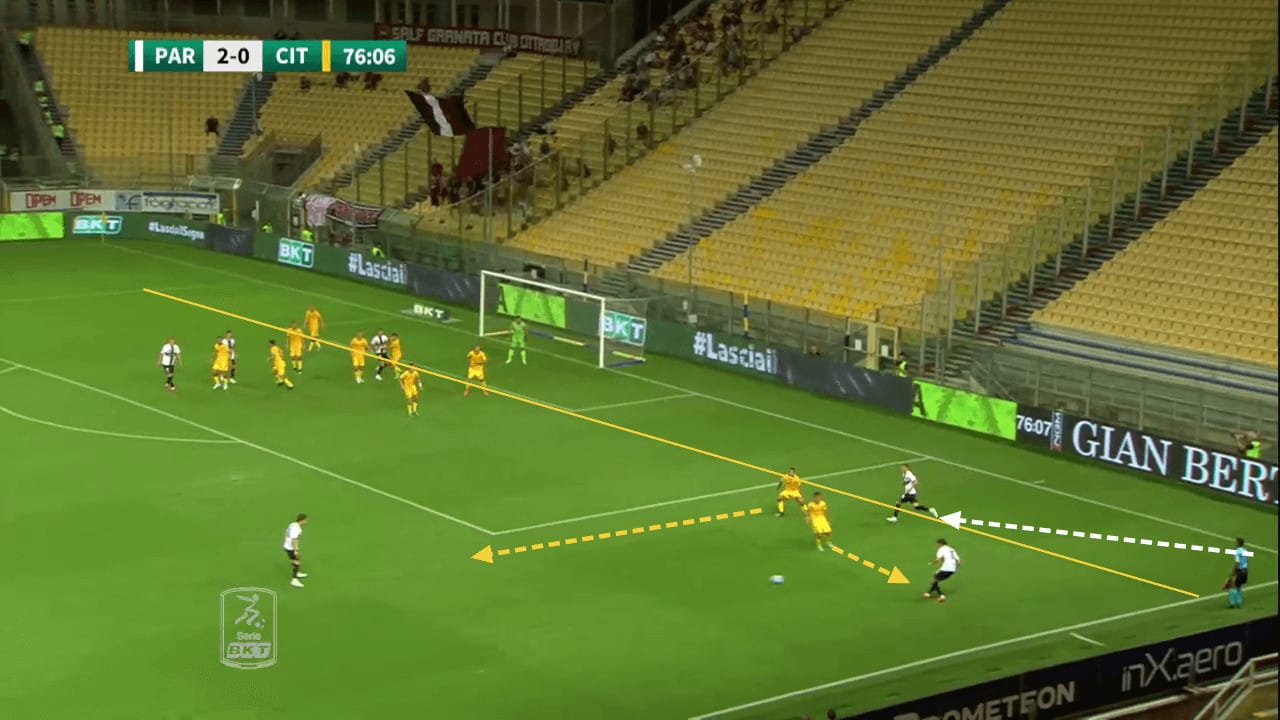

The example below shows Parma again using a 3v2 overload outside the box to create space for a free player in the attacking third. For the numerical advantage to exist, the corner taker must sprint into an onside position where he can still be available to receive the ball legally. Looking inside the penalty area, we can see a minimal attacking presence for Parma, which comes with both problems and advantages.

An advantage of looking so unthreatening and dull inside the penalty area is that it can make the defensive side overconfident and less aware. Usually, when a short corner is taken, the defensive team steps up to push attackers further from the goal. Stepping up involves the whole unit being coordinated and can be more accessible when up against more attackers, as each defender will be responsible for playing their marker offside. However, with so many defenders having no obligation, it becomes easier for just one player to forget their part, leaving the offside line in a deeper position, which gives the corner taker more space to roam in before receiving the ball.

It is essential that the third player in this sequence, furthest away from the goal, is pressed immediately. Although positioned furthest from the goal, the fact they have the ball means that they have the possibility of picking out a teammate, which can’t be allowed. Furthermore, with the narrower position of the cross, defenders are more susceptible to a cross being delivered over their heads into the space behind their backs. So, the deepest player must be pressured.

As a result, this leaves the remaining defender with two attackers to cover. As the corner taker is usually in an offside position immediately, it becomes natural for the last defender to mark the player waiting to receive the corner rather than the taker himself. Due to this event occurring so commonly, Parma have managed to create a method where the corner taker can ghost into the penalty area regularly, with no one picking him up.

As the example below shows, having the deeper player receive the ball allows the corner-taker to roam into the box. The nearest defender must press the ball handler, meaning he has to leave the yellow zone seen below. The corner taker can then ghost into the box from a wide area, which would be called offside in almost any other circumstance. Still, with the deep defensive block during a corner, the player can enter the box from a wide area, where he is out of sight of any opposition defenders.

The issue with having such a small attacking unit in terms of numbers is that it is harder for attackers to find space inside the box. Only three attackers face eight defenders, so it is easier for defenders to man-mark players, with teammates helping to remain in zonal defending positions. The attackers also seem to be surprised by Parma’s success in finding the third man to run into the box and so stay static in the moments where the ball player needs the most movement.

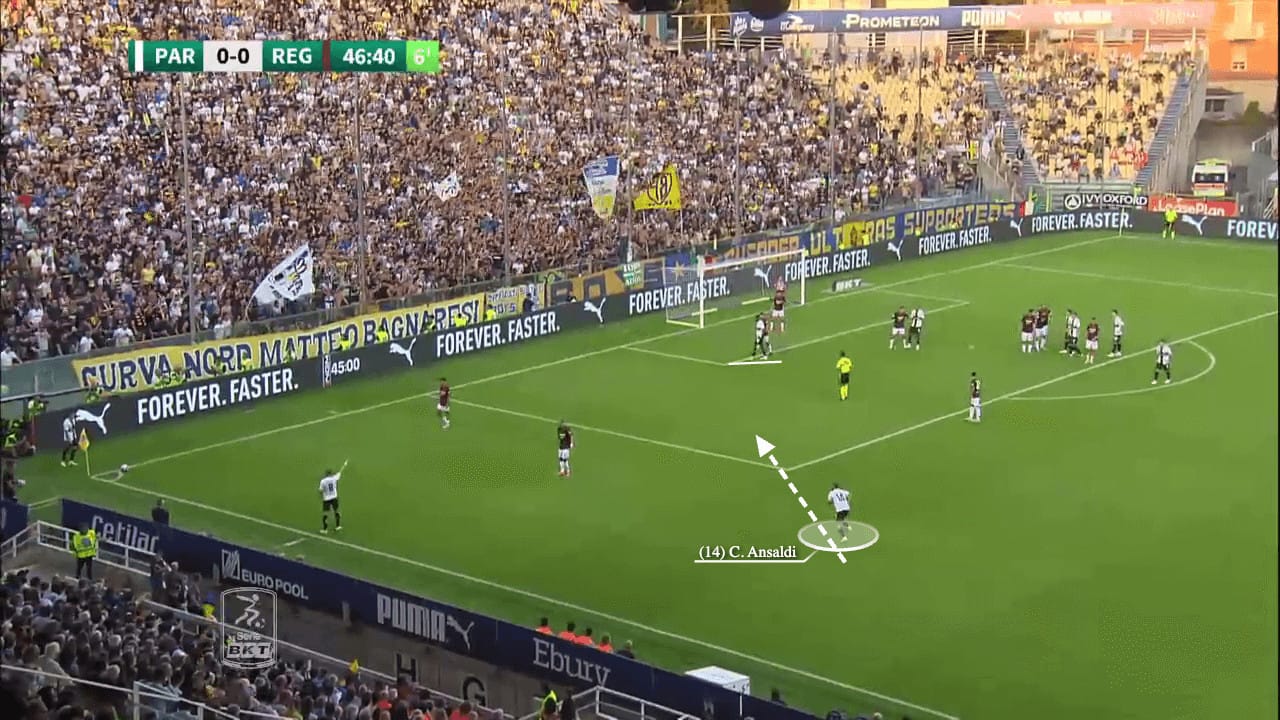

In certain moments, as pictured in the example below, defending teams use an extra player to be ready to man-mark the corner taker, expecting his involvement in the play. To combat this, Parma have added an attacker as well in order to maintain the numerical advantage. The fourth attacker can be pictured below, ready to receive the ball. This makes it possible to recreate the earlier plans, where defenders mark the options nearest to the ball, where the corner taker can be left unmarked again and float into the penalty area unmarked.

With the deep position of the ball player, the defenders start to face away from the goal, which allows the original corner taker to creep into the defender’s blindside and make the movement into the space left behind. The example above also showed a decoy run being made from inside the box to out, increasing the space the original corner taker can roam into.

Below is yet another example of how the corner taker has quickly recovered into an onside position whilst Parma are passing the ball around to keep the defenders’ attention away from the players they should be marking. With the corner taker being left unmarked due to the arrival from an offside position, no defender considers him their responsibility. Hence, he can easily sprint into the penalty area without anyone tracking his run.

I believe Parma could see more success with this method if they could swap the foot used by the player, making the pass over the top. With a left-footed pass from the left and right-footed from the right, the ball comes over the recipient’s shoulders, and the player has to look up to track the ball, leading to a higher chance of failing to make proper contact with the ball.

If the foot swapped, and a right-footed pass was inswinging into the player at the left wing, the attacker would see the ball travel the entire way, and it would move into their body rather than away, leading to a higher chance of making firm contact with the ball. This could also be made as a reverse pass, where the disguise could create further space for the intended target.

Parma have also begun to add variations to these short routines whenever possible. One way this was done was through the proactive movement of the receiving players. As we can see in the example below, the deepest player recognises the vast space available in the box already.

Rather than making a few passes to drag players and create that space, he instantly moves to receive, as the intention behind these corners is to get the ball into that wide area inside the box, from where a cross has a higher chance of success.

A significant issue that Parma have faced is their lack of care to the details inside the penalty area. As we can see in the example below, there are six attackers ready to receive the ball. However, Parma fail to organise the movements inside the penalty area, so none of the attackers are in an advantageous position over their markers. We know the nearest player to the ball is attempting to provide a screen.

However, the other five attackers all aim to attack the same area of the box. The attackers all make the same movements towards the near side of the six-yard box, but each attacker has failed to create separation, and so can easily be nullified. Parma can create separation for its players in many ways, whether through screens, decoy runs, or altering the starting positions to have a clearer path at the target area.

In addition, Parma attempt to attack the most congested part of the penalty area. With so many attackers in this particular example, the defensive side is spread thin to mark each player, and significant gaps are evident at the back post. Yet, Parma failed to react and attempted to force the ball into the one area they are comfortable attacking.

It is clear that the Parma attackers aren’t well prepared in the details of how, when, and the reasons why to attack the incoming crosses, which is apparent with almost every cross delivered into the penalty area and is a stark contrast from the solid methods they have in getting the ball to good crossing positions.

Conclusion

This tactical analysis has detailed how Parma have stood out from set plays so far this season. Their ability to consistently allow their preferred corner taker to move into more favourable crossing conditions and accurately play the ball into him has impressed this season so far. Parma clearly instructs the corner taker to always be available to receive the ball by moving into an onside position instantly.

Furthermore, they consistently use third-man run combinations to find the corner taker in space, but it seems that once they get to that point, there is a lack of intent from the remainder of the team to want to attack the cross. The attacking unit inside the box needs to trust the team’s ability to retain the ball from these short corners and remain patient in the box, ready to attack the six-yard box once the corner taker receives the ball inside the penalty area. If Parma can iron out a few issues, they will become a constant threat from set pieces, with teams struggling to keep up with the different movements of the players surrounding the penalty area.

Comments