In last month’s magazine, I looked at three common pressing strategies and the patterns of play and structures that could be used to break them, and thanks to an excellent response, as you can see, we’re onto part two. In this tactical analysis, I’ll outline three more pressing strategies, including my preferred system in an ideal world, and look at how the use of various principles, tactics and patterns can allow these presses to be broken. As with last time, there is a short disclaimer with regards to how this is structured, with probably a bit more pragmatism than in the first article, however for every press I have attempted to use a standard 4-3-3 build-up shape at some stage.

3-4-3

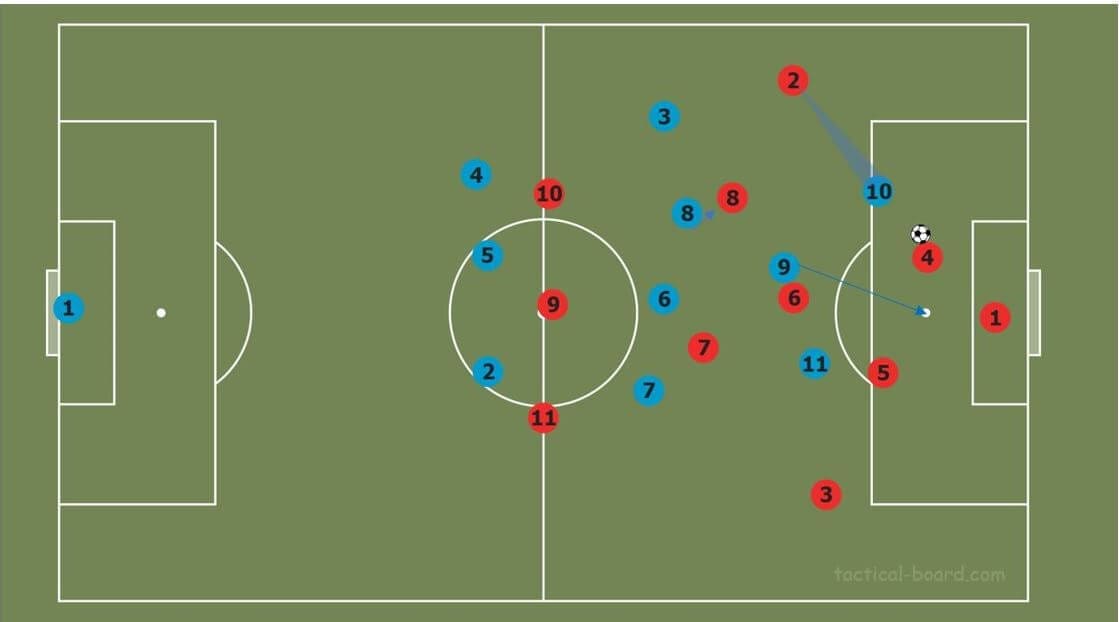

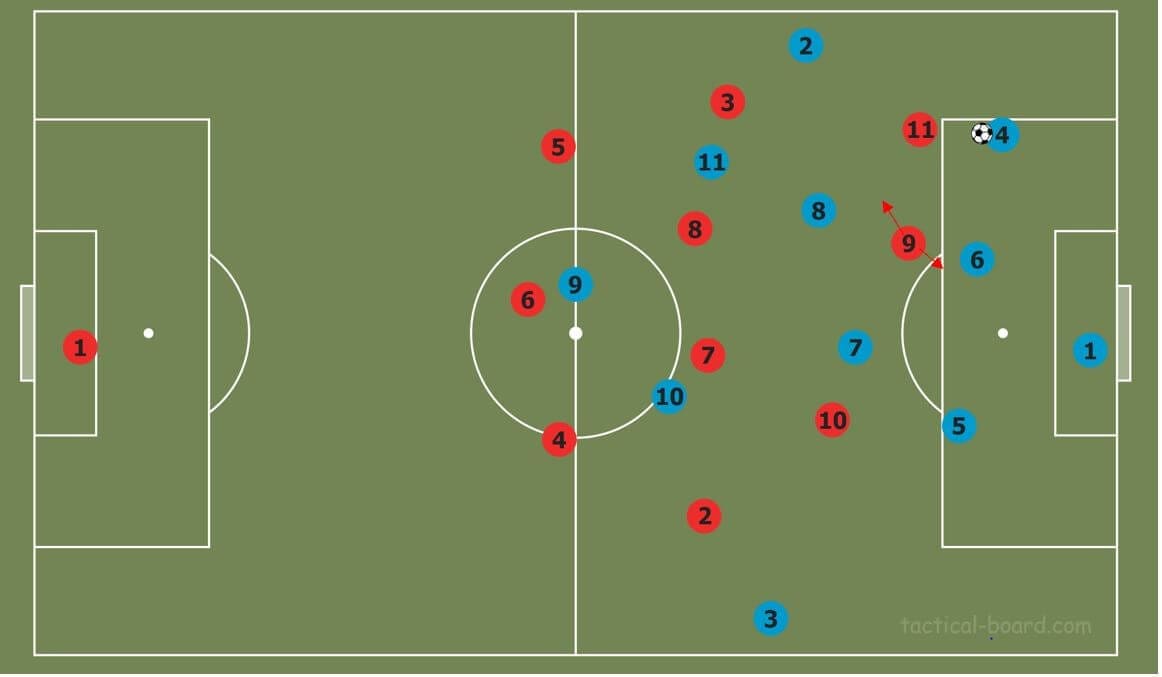

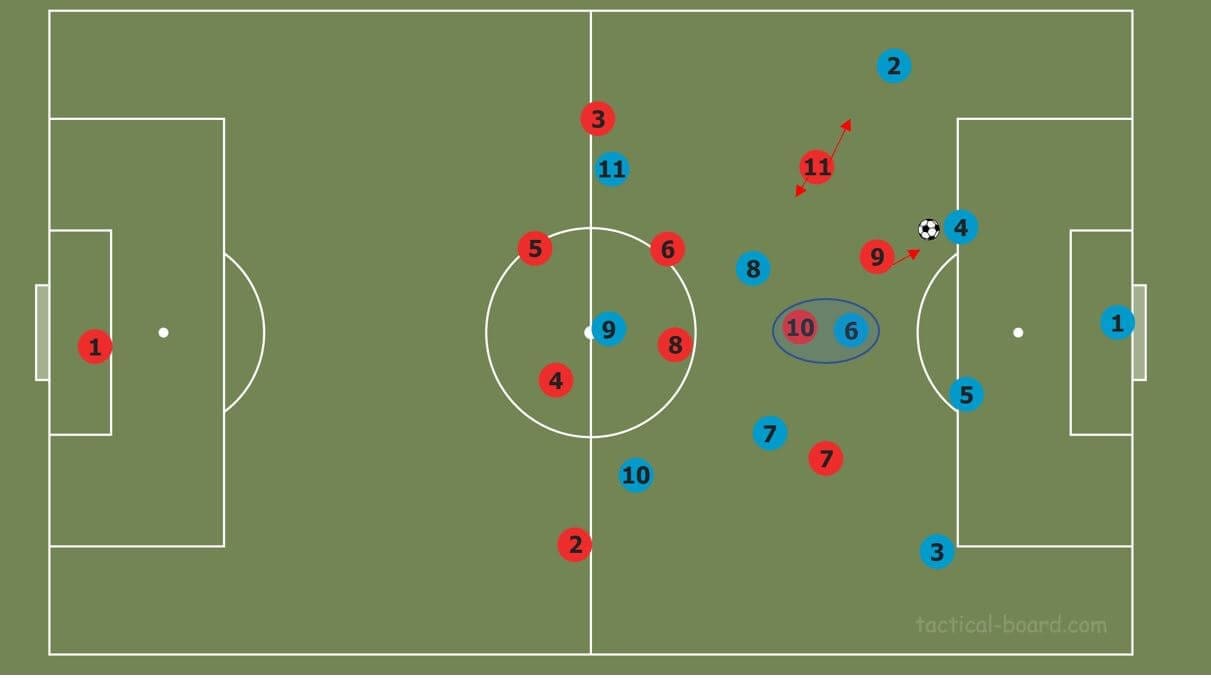

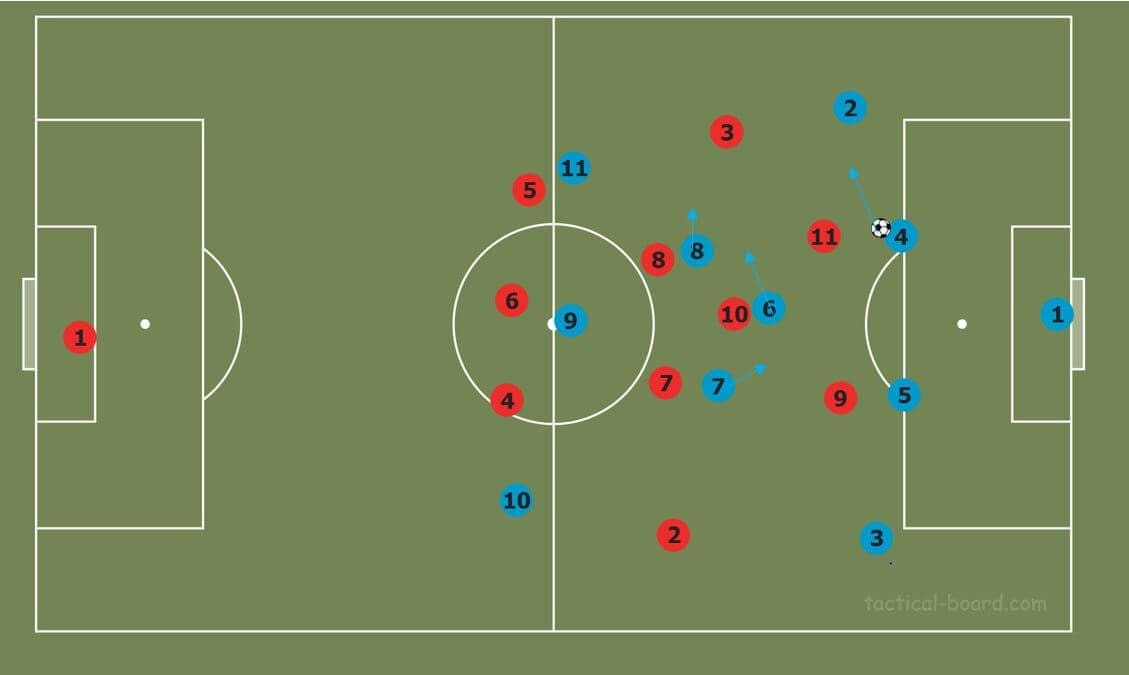

The first pressing strategy we will look at is a 3-4-3, with an emphasis on cutting the passing lanes to the full-back, and therefore forcing the team building up through the middle. We can see here the pressing winger/inside forward (number ten) presses inwards on the centre back, while cutting the passing lane wide. The striker covers the pivot if there is one and is also in a position to press the goalkeeper while keeping the pivot in their cover shadow if the ball goes back.

The main difference between this, and Liverpool’s 4-3-3 which I mentioned in the previous analysis, is the permanently high positioning of the wing-back/winger (number three). In theory, Liverpool’s press could look like this at times if one full-back advances and the other tucks in.

How to break it

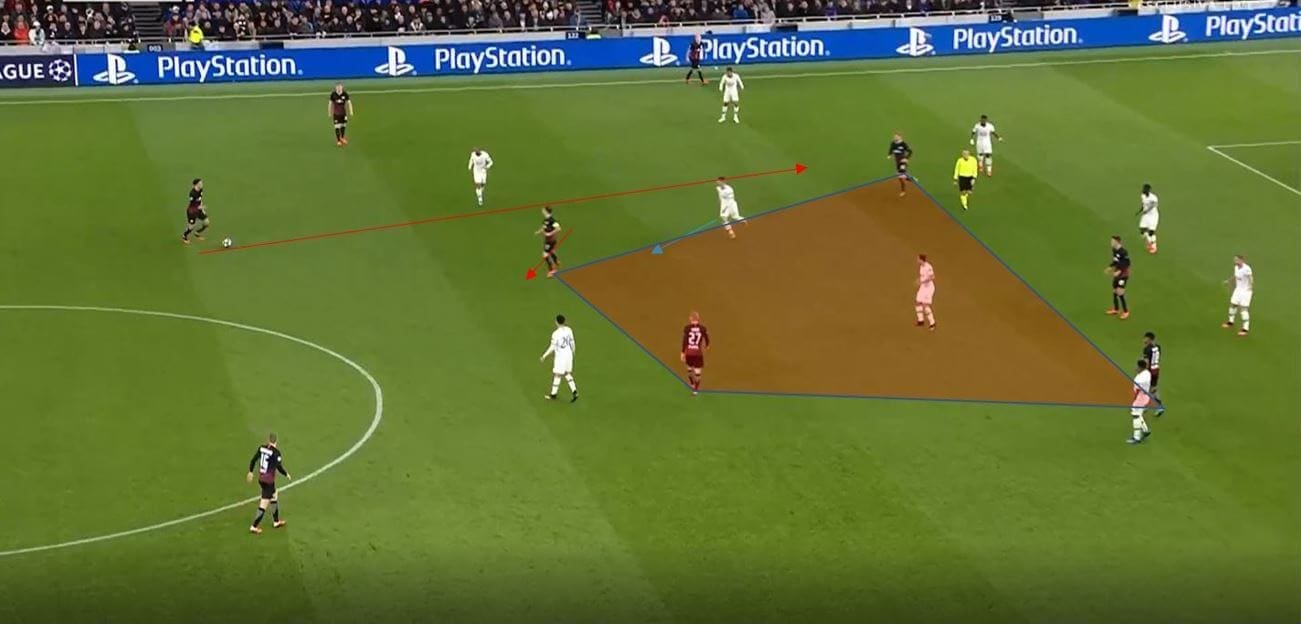

My first solution is very much centred around vertical passing and does admittedly require players to drop deep, but if support can be provided to these vertical passes, they could be effective. We can see a slightly emphasised picture of a potential way to break this type of pressing below, where we look to challenge them in their attempts to play down the centre. Here we are using a midfield box kind of concept, with the central midfielders acting as decoys and staying extremely centrally, looking to create space and occupy the central midfielders of the pressing team. Here, the attacking team needs to look to disguise the pass inside by feinting using body position to play inside and into the half-space. The main difficulty surrounding this is drawing that wing-back into a wide enough area to open up this passing lane, and so the build-up side’s wing-back needs to stay as wide as possible, in order to maximise the pressing distance and force the opposition player to adjust.

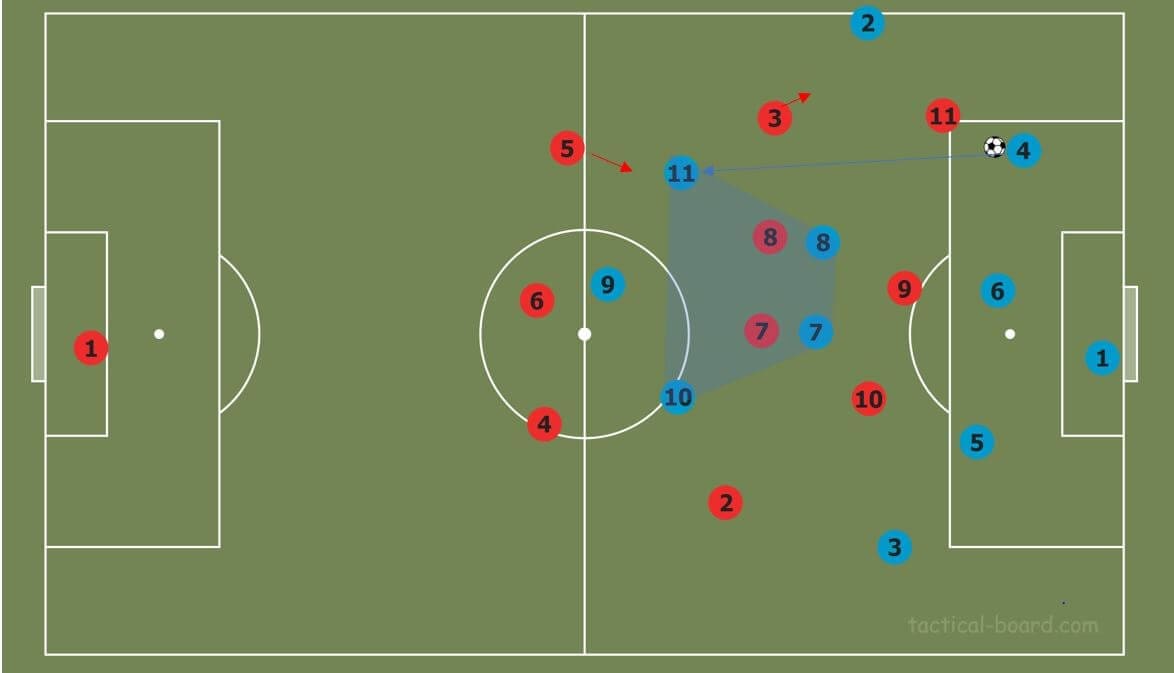

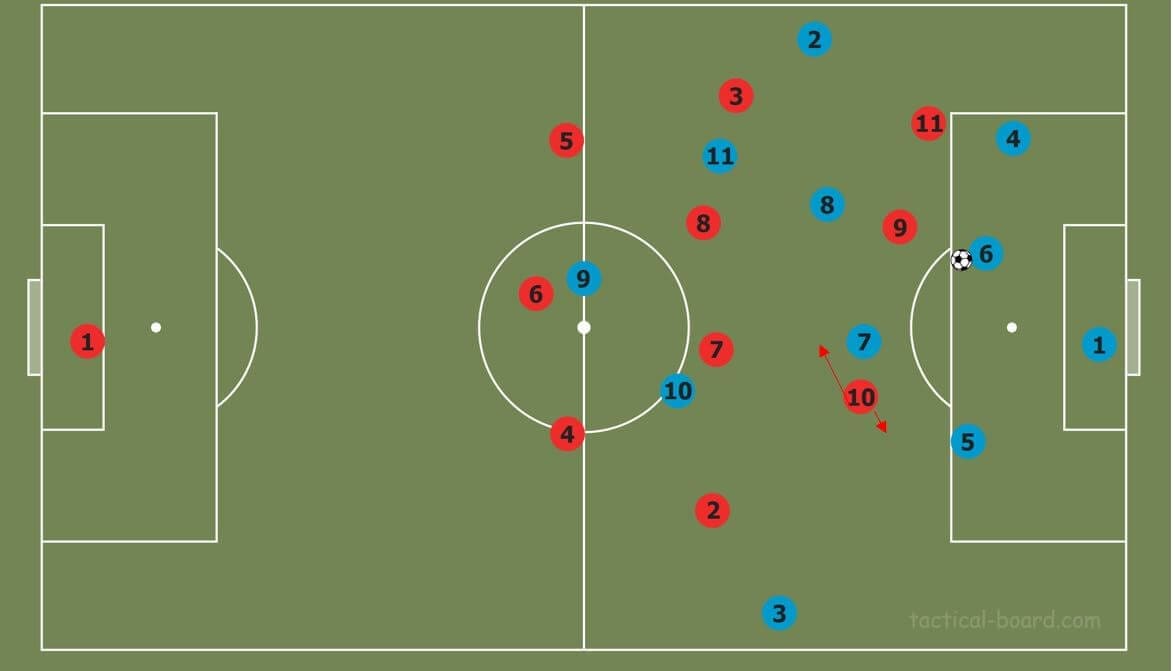

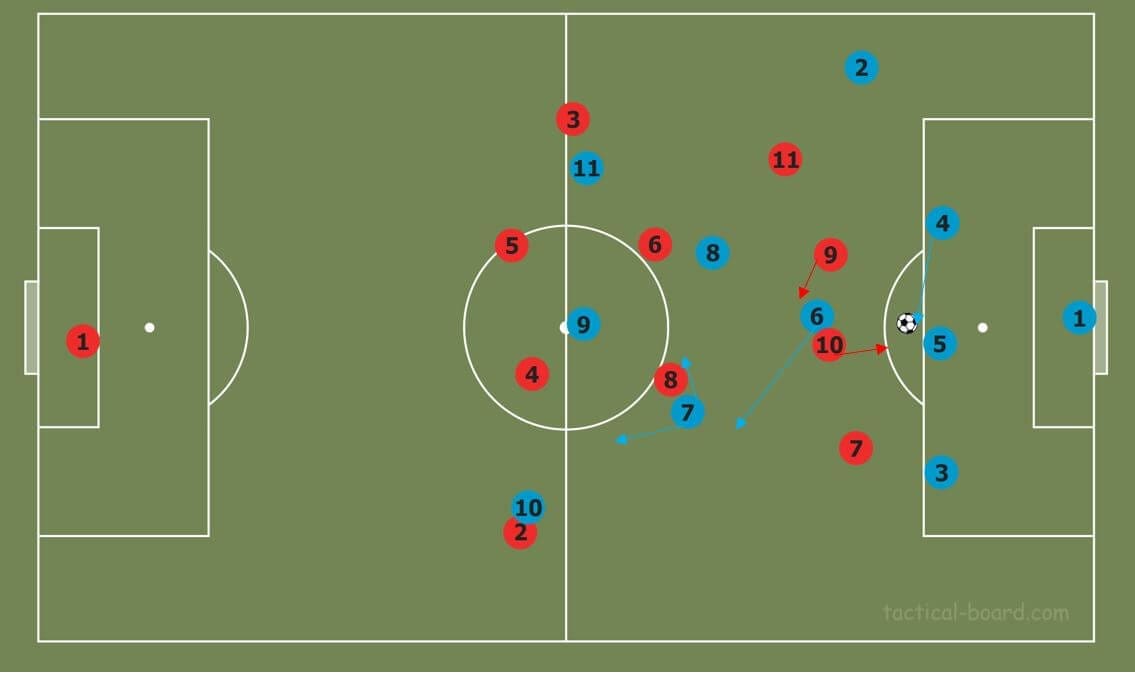

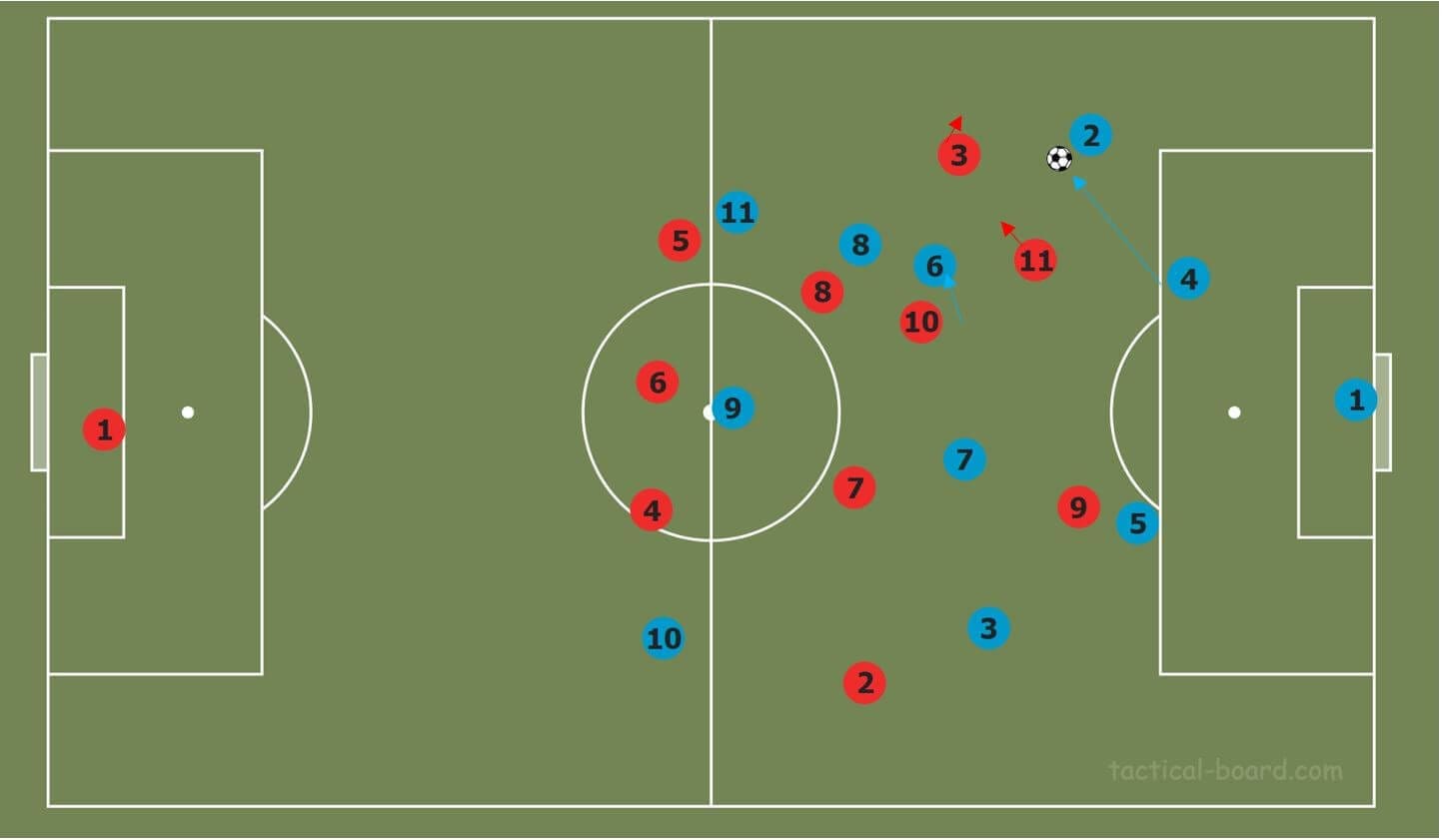

Below we can see an alternative method that relies less on the ill-discipline of the opposition. As seen in the Liverpool 4-3-3 section of my previous piece, here we look at overloading the striker, by placing a double pivot on them. In this freeze frame, we can see the basic ideas behind the shape, but this won’t be how it plays out positionally. The number eleven and ten pin back the pressing team’s number eight and seven, while the double pivot drops to create problems for the striker.

This next image shows the likely reaction the pressing side will have, with the winger tucking in to help the striker and protect the passing lane to the number eight. When this winger does tuck in, this is a trigger for the centre back to move slightly wider, and for the number eight to push on.

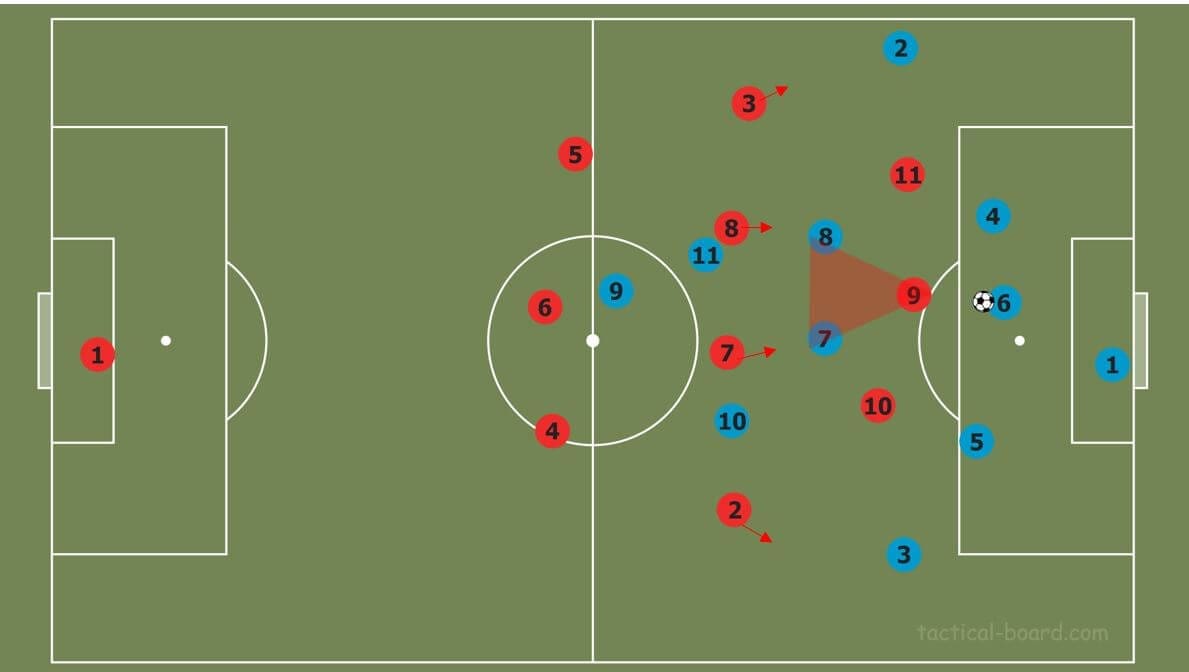

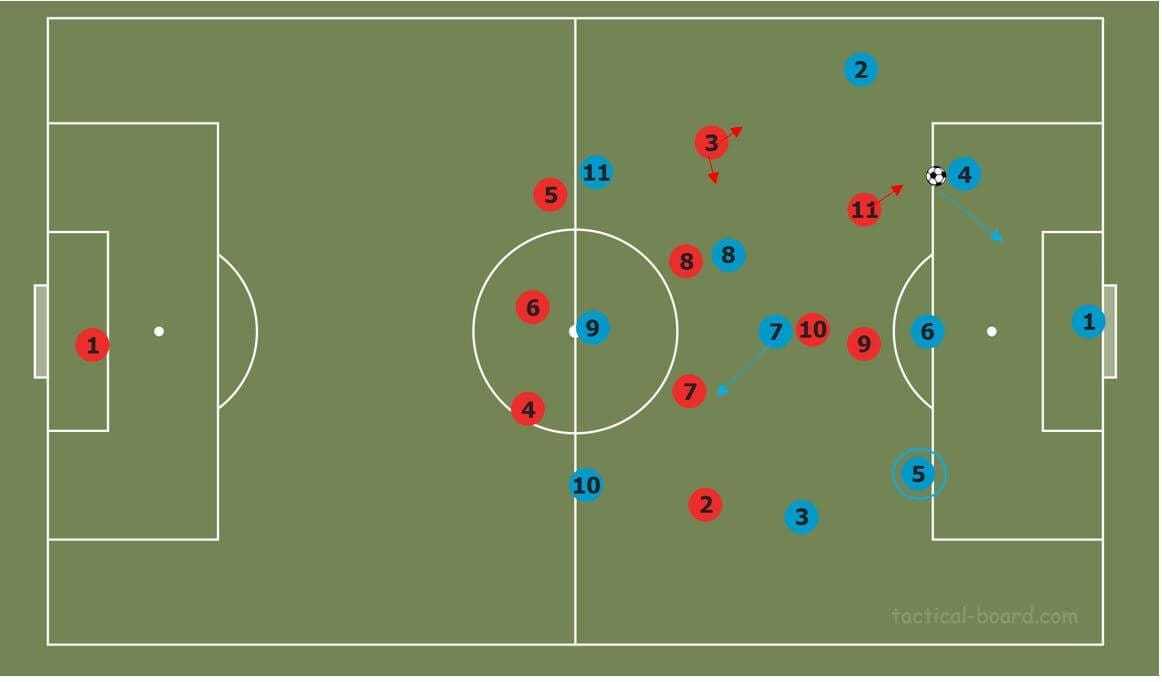

By moving this winger inside, we increase the pressing distance between them and the centre back (number four). As a result, this centre back will be able to receive the ball and pick a pass, which again will depend on the movement of the opposition. With the lane from centre back to wing-back no longer covered by the winger due to them tucking in, you would expect the pressing wing-back to move higher and tighter to the opposite wing-back. If the nine can’t get across to cover the passing lane into the central midfielder, then the first line of the press is overcome, and the second line is further back thanks to the pinning done which was mentioned earlier.

If the ball goes to the number four, and the striker does tuck across, this scenario below could occur. It is unlikely that the pressing winger can cover the inside lane alone to the now more advanced number eight, and so the striker may come across to cover this lane, which then leaves the central centre back open. From here, the other winger now has the decision of tucking in or staying with the defender, with again the pressing distance between the two sides’ central midfielders too large now. If the winger tucks in, the left-sided centre back is open, and has acres of space to drive into and attract a press from a player outside the first line of the press. The rest of the team can then push forward and progress up the pitch, with three players already in very advanced positions.

Four at the back with Tim Walter principles

This next way to break this specific 3-4-3 press involves a back four, with the rest of the team pushed higher and isolating the first line of the press to create a 5v3. The back four in a narrow shape forces the wingers to tuck and press the centre backs, with the striker no longer having a pivot to mark. This could see them instead take up a freer role and look to press the goalkeeper quickly, but this shouldn’t make too much difference to the pattern.

The centre back will be pressed upon receiving the ball from the goalkeeper. And one winger will tuck across to cover the other centre back. This pass back to the goalkeeper should act as the trigger for the number five to move out wide, and the quicker they can move out the better, in order to create separation between themselves and the winger.

From here, depending on optimal the angle can be made, the number five can then progress play into the advancing number six, with the pressing number nine being too far away to run with him as he had previously pressed the other centre back.

4-2-3-1

The next pressing scheme we will look at is a 4-2-3-1, which is slightly different to the flat 4-4-2 previously discussed due to the differing roles of the number ten player. Within this system the wingers look to protect the inside lane while keeping an optimal distance between themselves and the full-back. The number ten will usually mark the pivot, with the striker pressing the nearest centre back. If the ball is switched across, the number ten and nine swap roles.

How to break it

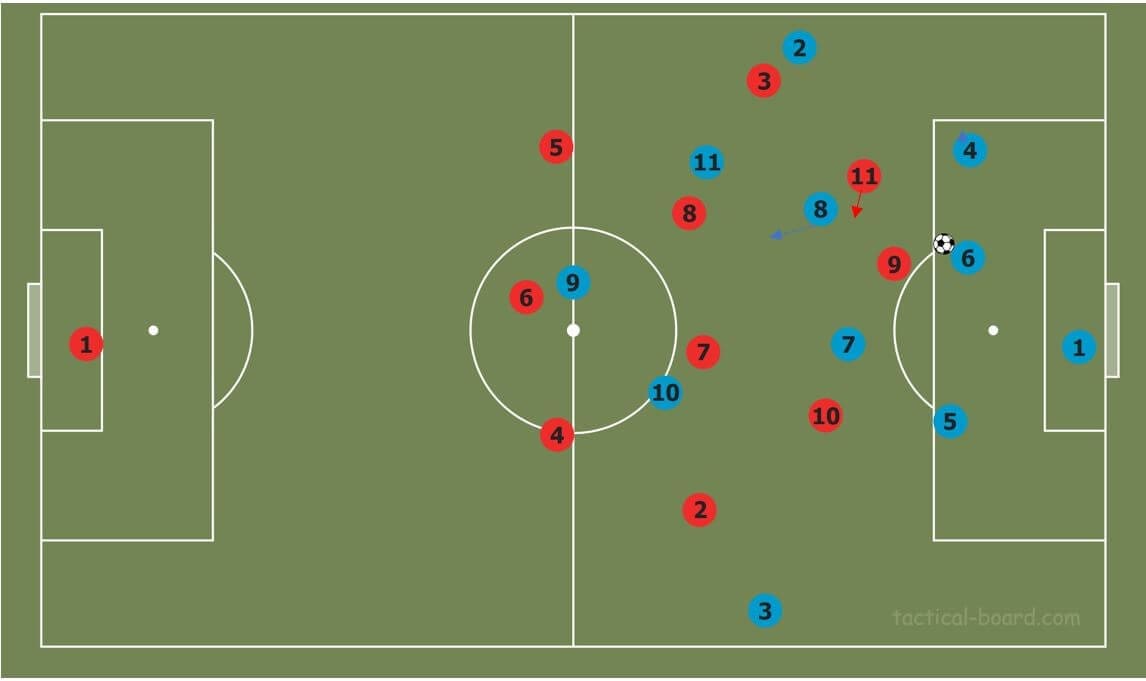

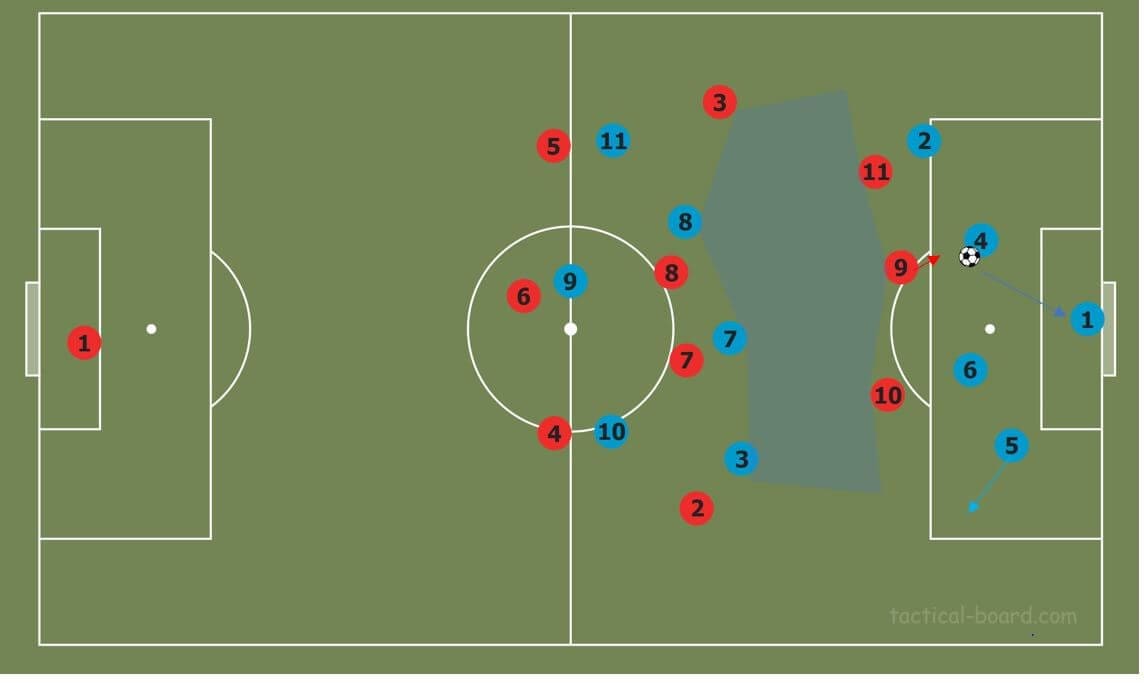

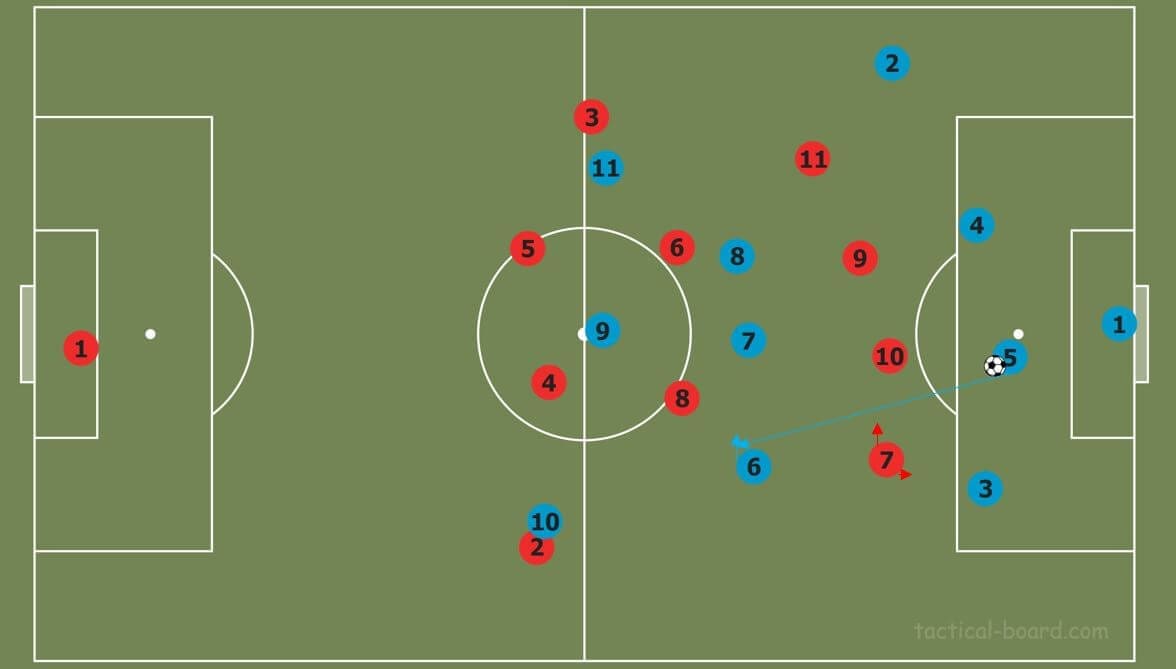

The key to breaking this press in my opinion is the transition that occurs between the pressing number nine and ten. If we carry on from the situation highlighted above, we see that the nine presses and forces a lateral pass across the line. Upon this pass being played, the number ten pushes across to press the centre back, and the number nine recovers to mark the pivot, as we can see below.

Therefore, if we can maximise the distance between the pivot, and the initial pressing number nine, you can create a free man. So, when the ball is beginning to look as though it is going to be played across, this should act as a trigger for the number six to move away from the number nine who will be approaching. The higher central midfielder (number seven) can look to pin back his opposite central midfielder and create space for the six to progress into. Again, the wider the full-back stays, the more space there is for a central pass.

It would be the best-case scenario for the number seven to move inwards, as this suits the body orientation that the number six will have when running from facing his own goal into this area quickly. This creates a 2v1 on the central midfielder and therefore allows the team to progress. If the winger does a good enough job of cutting the lane to the six, the full-back can be used and an overload is still present.

Using a back three to beat a 4-2-3-1

A method of beating the first line of a press which I have discussed often this season is the use of a back three. In the previous example using a back four, we can see the struggles that can be seen when relying on lateral passes with centre backs, as in a back four, the centre backs have to stay closer together to increase the speed of the pass and prevent interceptions. In a back three, there is an extra player in the chain, which therefore allows for better coverage of the back line. We can see below that this is very effective against a 4-2-3-1, as this formation can often have a one-man first line of the press. If you stretch the pitch and use a back three, it forces the wingers to press the wide centre backs, therefore meaning nobody is a good distance away to press the wing-back.

In the Bundesliga, Borussia Mönchengladbach used this system extremely effectively against RB Leipzig’s 4-2-3-1 press, with the ten occupied and the winger being forced to press the wide centre back. If we compare this to the previous solutions involving a back four, the winger is pressing between the full-back and central area. Leipzig are forced to commit a full-back forward to try and deal with the press, but the pressing distance is large and so Gladbach repeatedly exploited this kind of build-up and scored a goal directly from it.

3-4-1-2

The 3-4-1-2 formation matches up very well against a 4-3-3 build-up structure, with the pivot, full-backs and centre backs all equal numerically for both sides. We can see the pressing structure outlined below, with the number ten marking the pivot and a 3v3 in midfield, while the two centre backs are continually pressed by the strikers, and the full backs covered by the pressing wing backs.

How to break it

Again, if we carry on from the previous image, we can see a potential way to bypass the press. The pressing distance between the wing-back and full-back is large enough to allow the full-back to get it out of their feet, and if the centre backs space correctly, space for the inside pass can be created. Therefore, we need to try and create some numerical superiority, so once the ball is played wide, the pivot and number eight move across to the inside space but may potentially be followed in a man-orientated way. If this is the case then a pass down the line may be an option to the winger, with support provided on that side by the two nearby central midfielders, but in terms of body orientation it benefits teams to play diagonally and into the centre, as there are more passing options from a central area facing the opposition goal than in a wide area facing your own.

If the midfielders are followed, there is a potential for the number seven to quickly drop into the pivot and the ball to go back into them, as some separation between them and the marker should be created.

Using a back three

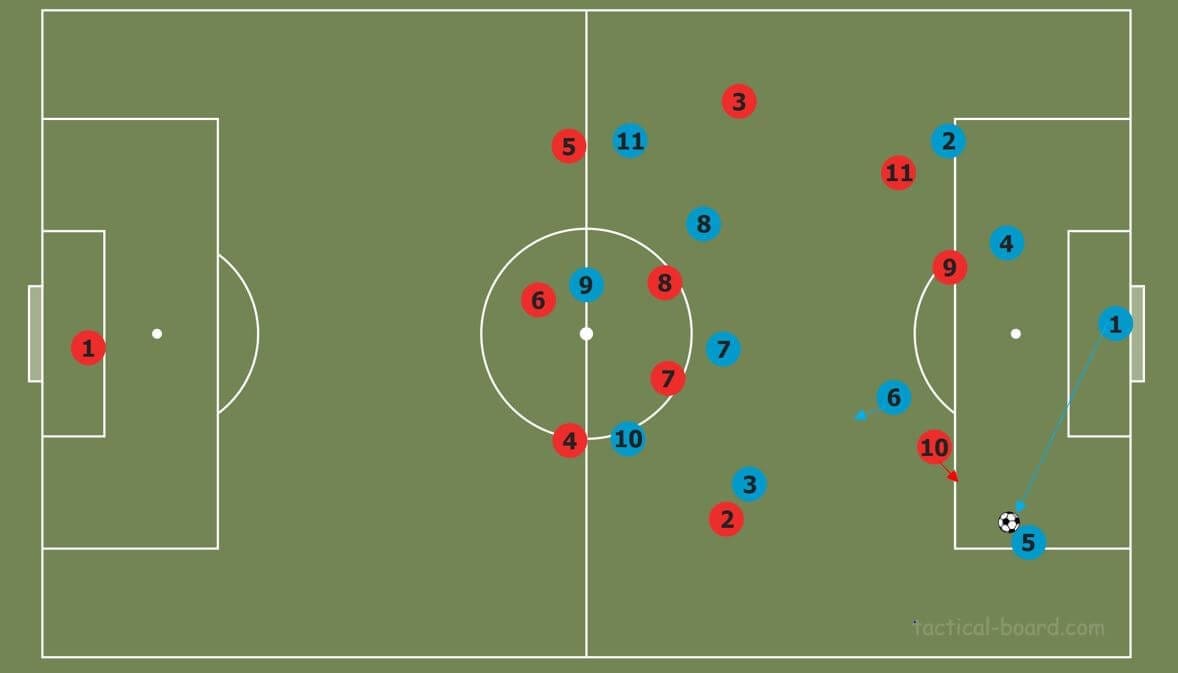

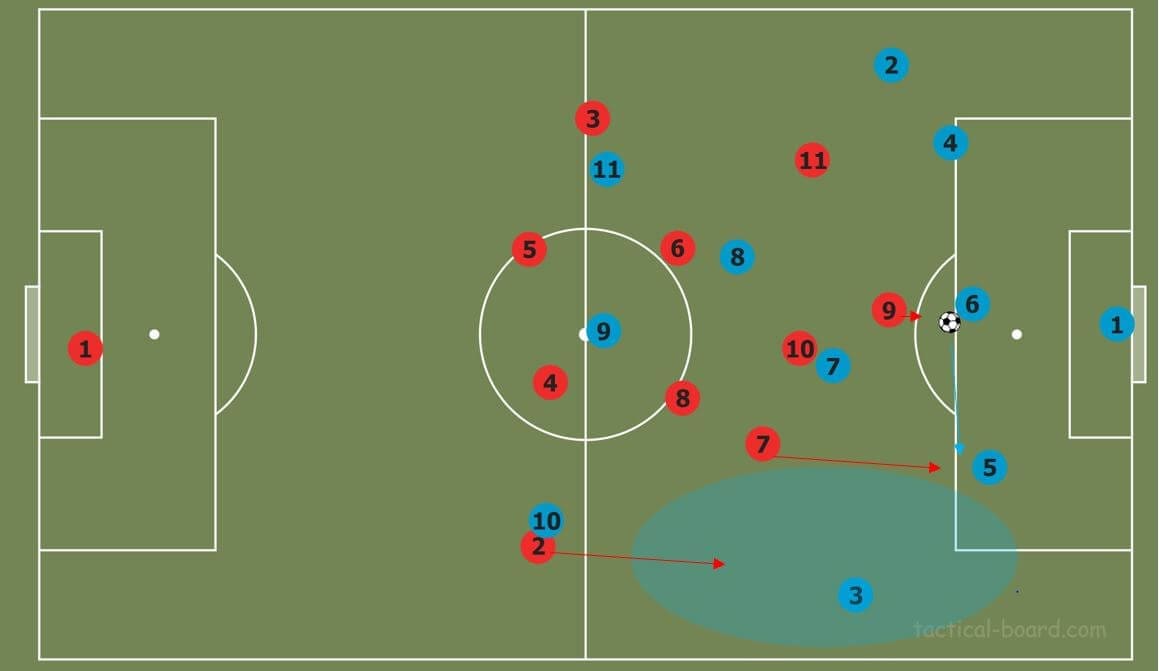

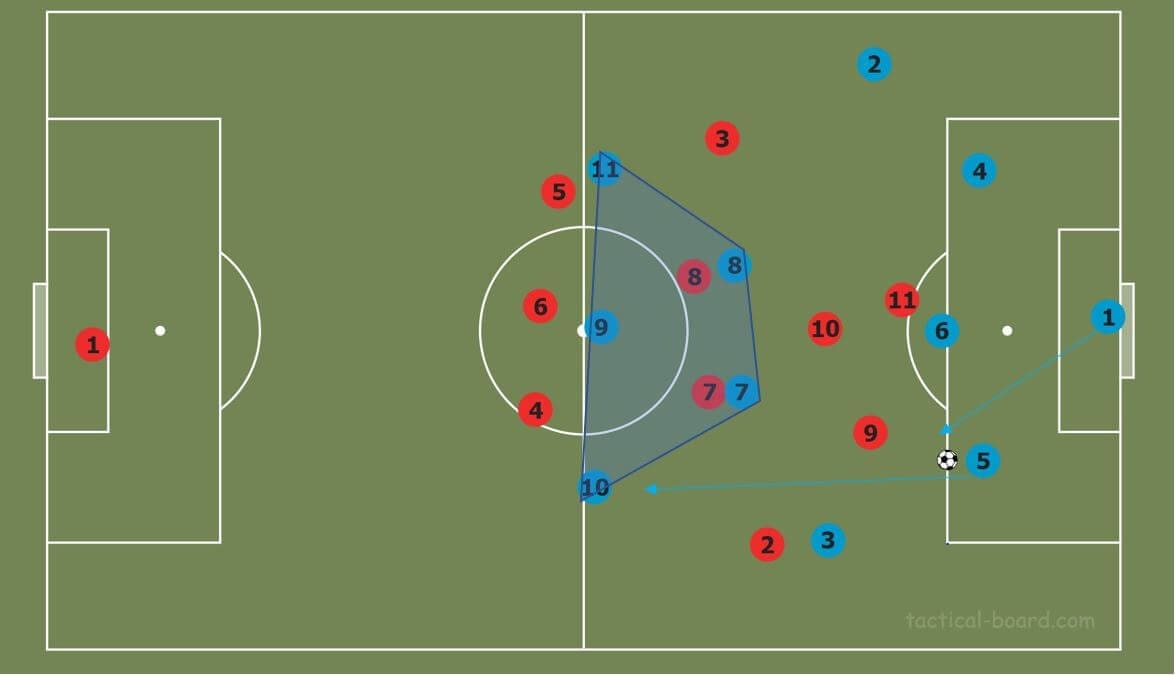

We’ve discussed the benefits of a back three and we can use this principle again here, with a bit of patience, combined with a midfield box in order to create space and directly access the third line (attack). We can see below that the right-sided centre back will be pressed by one of the strikers, with the other coming across to mark the central centre back. The number seven stays with the pressing number ten to occupy him, and the goalkeeper is used to create a 4v2 in the first line of the press.

If stretched enough and played quickly enough, the pressing distance between the pressing number nine and the far centre back should be large enough to allow some forward passing, and so space should be occupied effectively in order to make the most out of this forward passing opportunity.

We can then go back to one of the earlier concepts used in a midfield box, with the number seven having now moved to occupy a central midfielder and remains in the centre. The wing-back looks to stay wide enough to create space in the half-space, and the wing-back should look as though they want to receive to attract the attention of the opposition wing-back.

We can see below, RB Leipzig using this shape against Tottenham in a 4-4-2 in a higher area, but with the same principles applying. Width is needed to create space in the middle, and the half-spaces are occupied and freer due to the central positioning of the two central midfielders.

Conclusion

There are a number of patterns, structures and strategies in order to beat pressing schemes, but when pressing schemes are broken down in this way you hopefully start to see that regardless of what numbers come up, the differences between them are fairly minute, and so it is more about the role each player plays within a press that decide how to break it. Tactical flexibility I believe will be the next trend within football over the next few years, and so we may see more of these personalised build-up shapes to counteract an opposition press.

Comments