OGC Nice have been quite impressive in Ligue 1 this season.

They are currently sixth in the Ligue 1 table from 11 wins, eight draws, and nine losses – just behind Reims albeit with the same amount of points (41 points).

What makes this more impressive is that the side, currently managed by former Arsenal midfielder Patrick Vieira, have been using a very young squad.

In fact, Nice actually have the youngest average age in the league at 23.7-years-old, while bottom-of-the-table Toulouse and fifth-placed Reims trail with an average age of 24.1 and 24.2 each.

Vieira came in to take charge of Les Aiglons in the 2018/19 season, replacing Lucien Favre who left for Borussia Dortmund.

The former France international gained plaudits when he joined Nice as he introduced a free-flowing attacking game.

His philosophy relies on flexibility in the game and it’s something that makes his team very hard to contain.

His team’s performance in the first season was certainly not bad as they finished eighth in the Ligue 1 table, again, with the youngest squad in the league (average age of 21.8).

This season, Vieira certainly wants to aim higher, looking to finish in a European spot.

In this tactical analysis, we’ll take a look at the tactics behind Vieira’s success this season at Nice alongside potential vulnerabilities that may come with his tactics and philosophy.

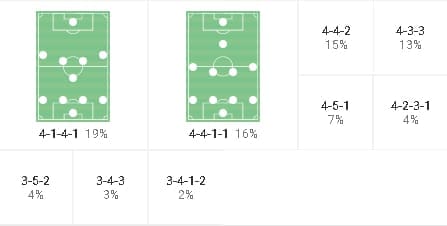

Patrick Vieira Formations

This season Vieira mainly employs a 4-1-4-1 formation along with its variations (4-3-3, 4-5-1).

Often, Vieira tweaks the formation a little and uses a variation of 4-4-1-1 which can also be 4-2-3-1 or 4-4-2 on paper.

It’s also not rare to see them lining up or changing the formation mid-game into a three-man backline system, using a 3-5-2 or 3-4-1-1 or 3-4-3 in the game.

It may appear that Vieira doesn’t really have one set/favoured formation and likes to experiment with new ideas.

Though the formations he uses in the game may vary, the philosophy and tactics he employs are pretty much the same in every game.

Albeit with a few tweaks that are dependent on the opponents they face.

With that said, a lot of times the formations that he actually uses in the game may differ from what’s on paper.

Having seen Vieira’s Nice play, it is quite clear that the formations that he uses in his starting lineups are rather insignificant as most of the times they don’t really reflect the formation on paper.

As mentioned previously, Vieira relies a lot on flexibility.

There are always a lot of formation changes during the game as they take up different shapes depending on the phase of play they’re in.

This will be explained in more detail in the next sections of this tactical analysis.

Patrick Vieira Attacking tendencies

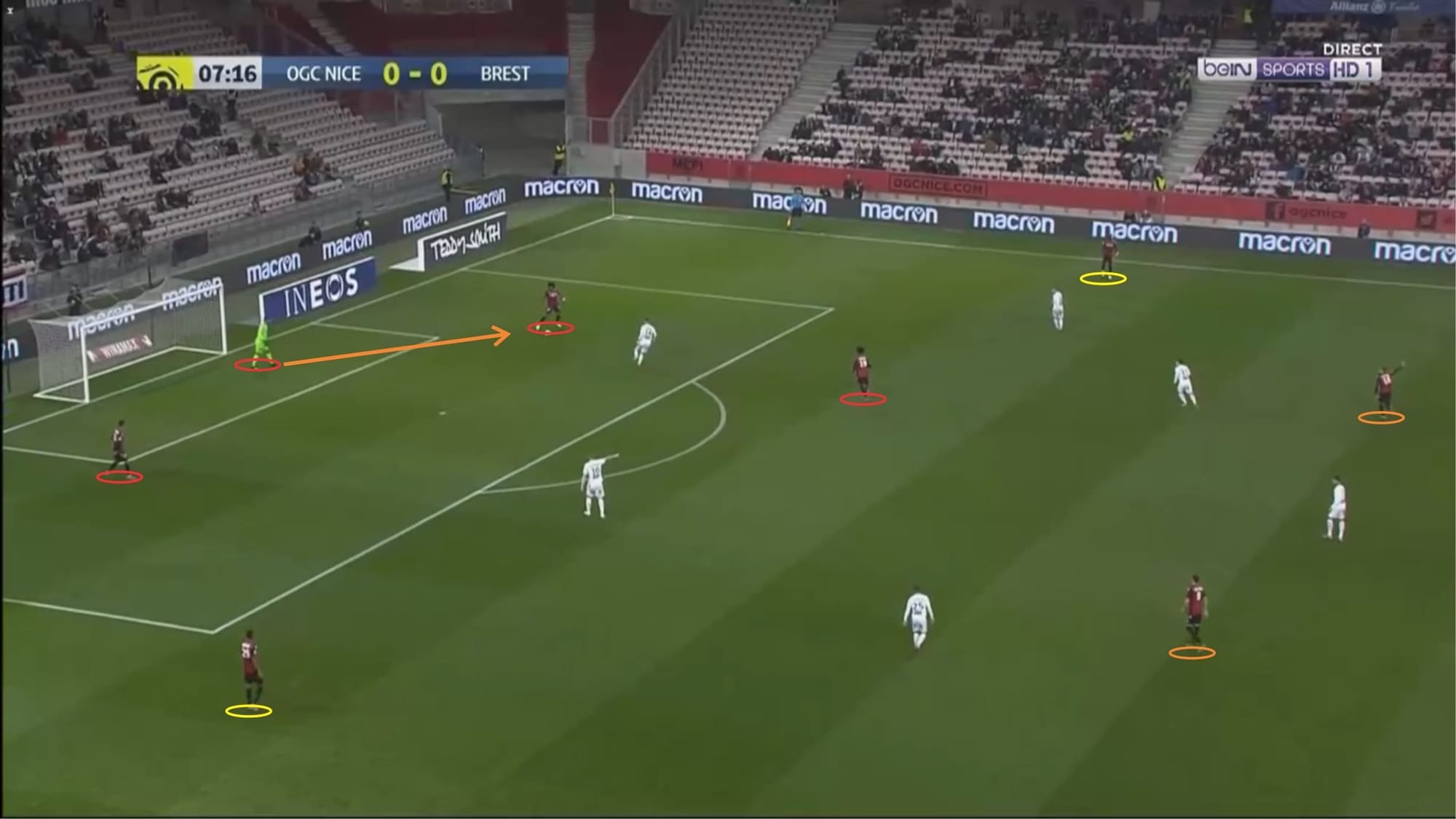

Vieira’s Nice tend to play from the back with the goalkeeper making a short distribution.

They’re quite patient and possession-based, tending not to rush even when under pressure, mainly opting to use short passes and play their way out of pressure and then work their way into the box.

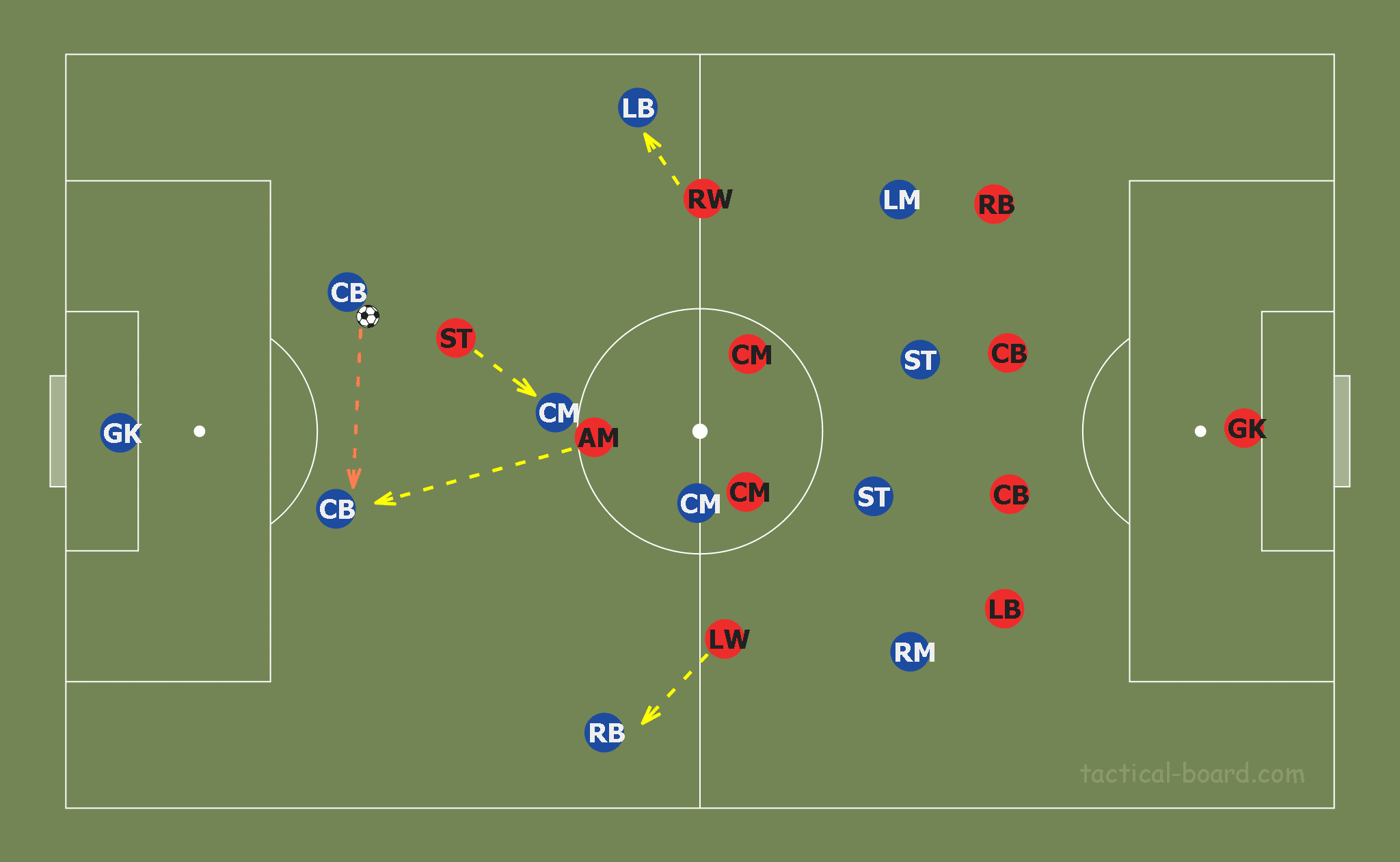

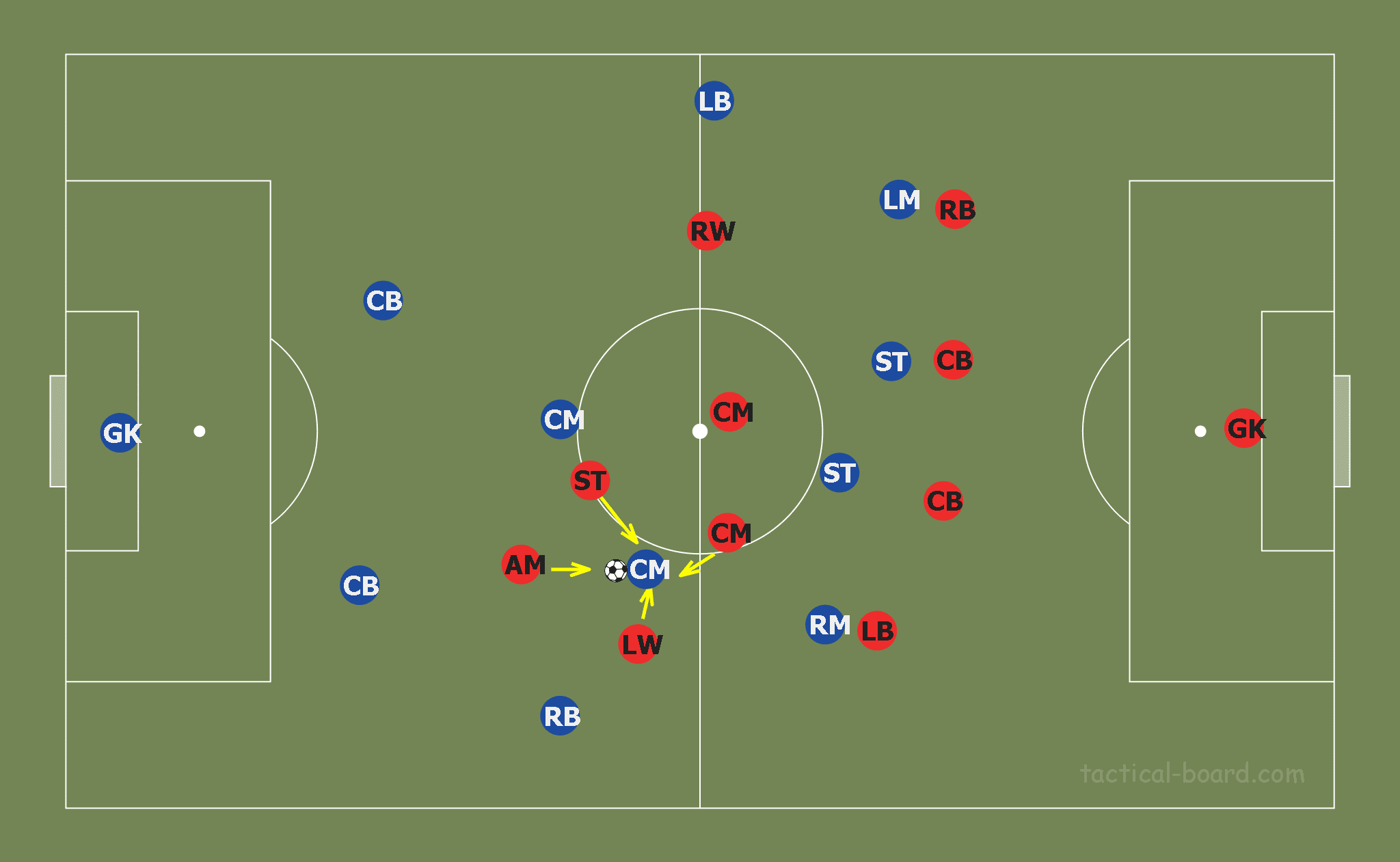

Above is the initial shape that they usually use in the build-up.

In this particular match, Nice play with a 4-4-1-1 formation.

As you can see, the centre-backs sit inside the box and apart from each other, while one holding midfielder plays as a pivot but actively moves and tries to make himself available as a progressive passing option to help exit pressure.

The goalkeeper is always involved when they’re playing out from the back as he also always looks to move around and make himself available if no progressive option is available.

Walter Benítez’s touch may not be perfect but he’s certainly not awkward on the ball.

Most importantly, his passing in open play is rather impressive and often can save his team from being overwhelmed by pressure deep inside their own half.

The full-backs (yellow circles) don’t sit very high, providing yet another option to escape pressure in case central areas are completely inaccessible and they have to play around the block in order to exit pressure.

Meanwhile, there are usually two players (in this situation, a central midfielder and an attacking midfielder) who sit in the half-spaces, maintaining a fairly high position.

While one central midfielder holds himself in a rather deep position, the other one sits in a more advanced area.

In case the backline decides to play the ball long, the two midfielders in the half-spaces will usually look to collect second balls.

However, if the opponents are piling pressure to the backline, then one of the two advanced midfielders will drop down to create numerical advantage and provide support.

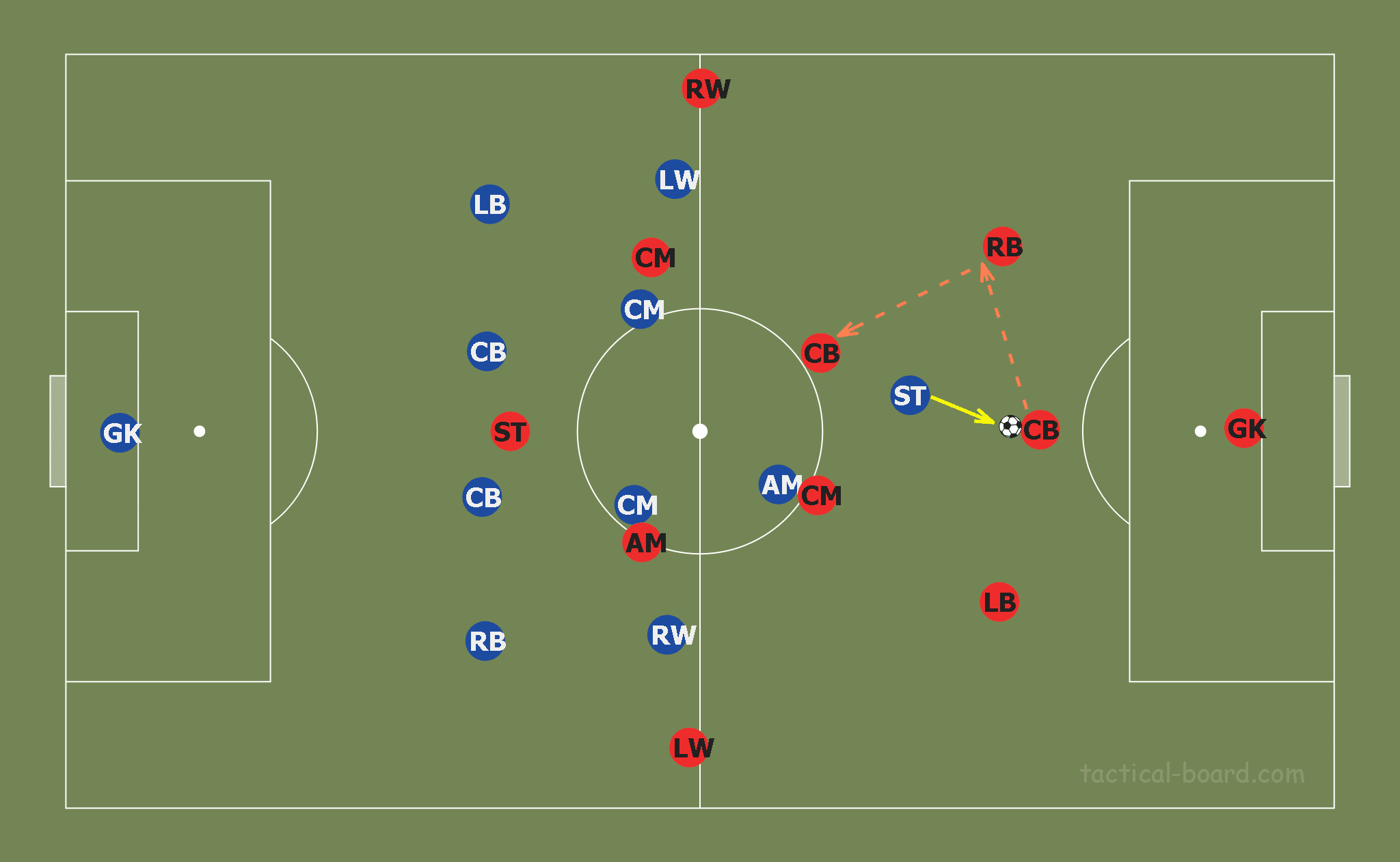

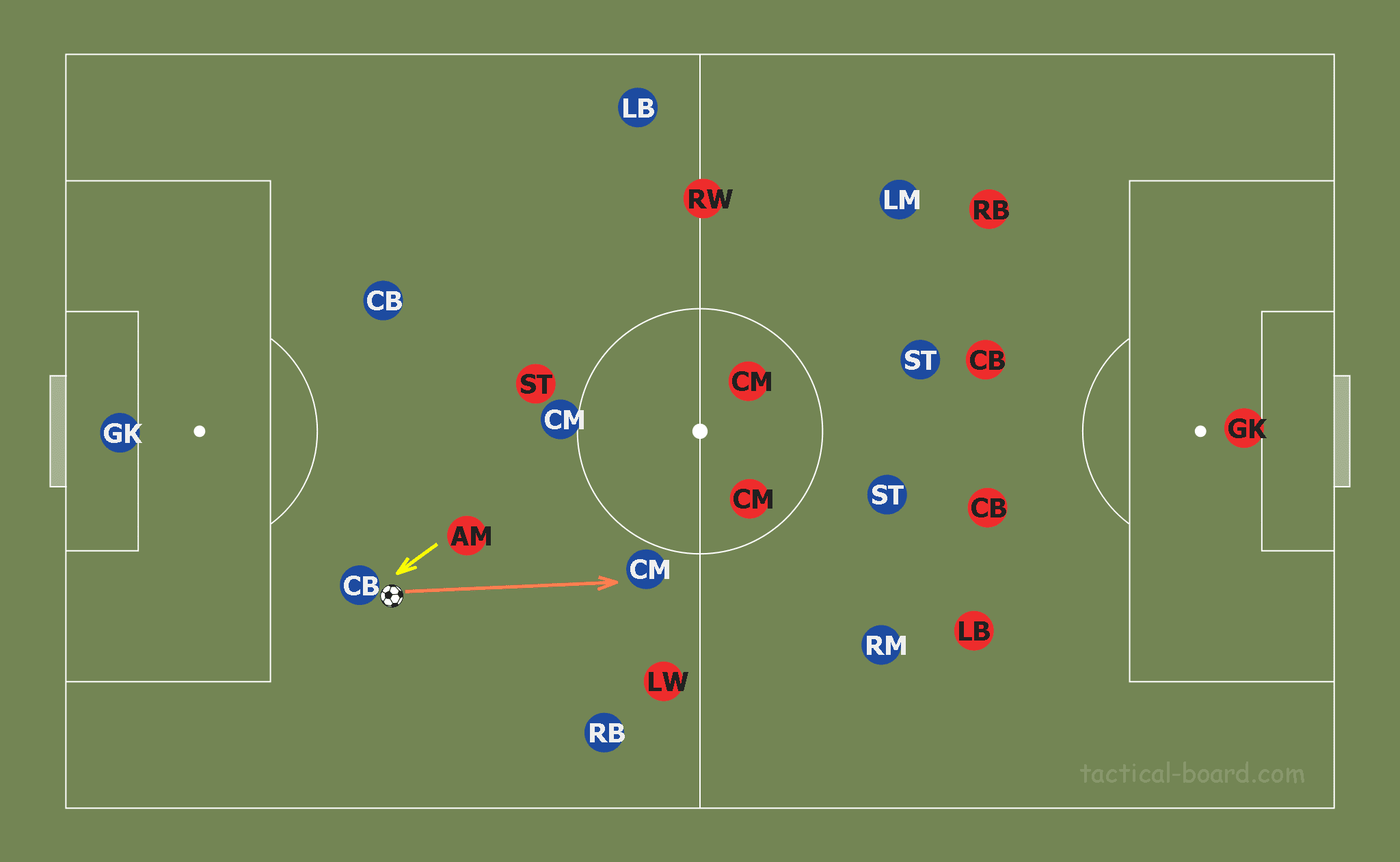

Although their shape normally looks like the image above when they’re playing out from the back, it can often change into a three-man backline, taking up a 3-2-4-1 shape.

What’s interesting is that usually one of the two centre-backs will step out of position and sit in front of the backline, partnering with the holding central midfielder as a double pivot, meanwhile the two full-backs stay deep and sit narrow rather than sit high and wide.

This can be seen in the image below.

As you can see, by having five players circulating the ball at the back (plus the goalkeeper if forced to play the ball back), not only can Nice outnumber the first line of pressure of their opposition, but they can also create triangles, allowing them to circulate and progress the ball with ease.

Vieira usually uses defensive full-backs when playing which perfectly suits this system.

Malang Sarr and Stanley Nsoki who are often played as a left-back, for example, are strong on the ball and has good distribution whilst only defensively solid albeit not offering a lot of support and creativity in advanced areas.

Meanwhile, Patrick Burner and Christophe Hérelle usually occupy the right-back berth.

However, there’s a different tendency, when Burner plays compared to Hérelle.

While there is still visibly the same tactical tendency of sitting deep and narrow to create a three-man backline in the build-up when the ball gets into advanced areas, Burner tends to advance forward rather than stay deep, meanwhile, the centre-back-cum-pivot returns to his position.

On the other hand, Hérelle tends to maintain his position even when the ball is in advanced areas, allowing the centre-back-cum-pivot to stay in front of the defence and help rotate possession while the team are inside the opposing half.

Despite using varying formations this season, this creation of a three-man backline with two pivots upfront is a very consistent tendency in Vieira’s Nice team and happens in every single formation they use, whether it be 4-1-4-1 (with all its variations), 4-2-3-1 (with all its variations), and other three centre-backs formations.

The difference is that when he uses a four-man backline, one of the centre-backs will move forward and sit in the pivot spot, but in a three-man backline formation, the shape is automatically created when they’re building up from the back.

Their tendencies in attack are also pretty much the same in any formations they use although there are several differences in defence which will be talked about later in this analysis.

Usually, a more athletic Danilo Barbosa is the one that moves forward while Dante Bonfim stays in his position.

Although, on rare occasions the former Bayern Munich defender can be seen occupying the pivot spot as well.

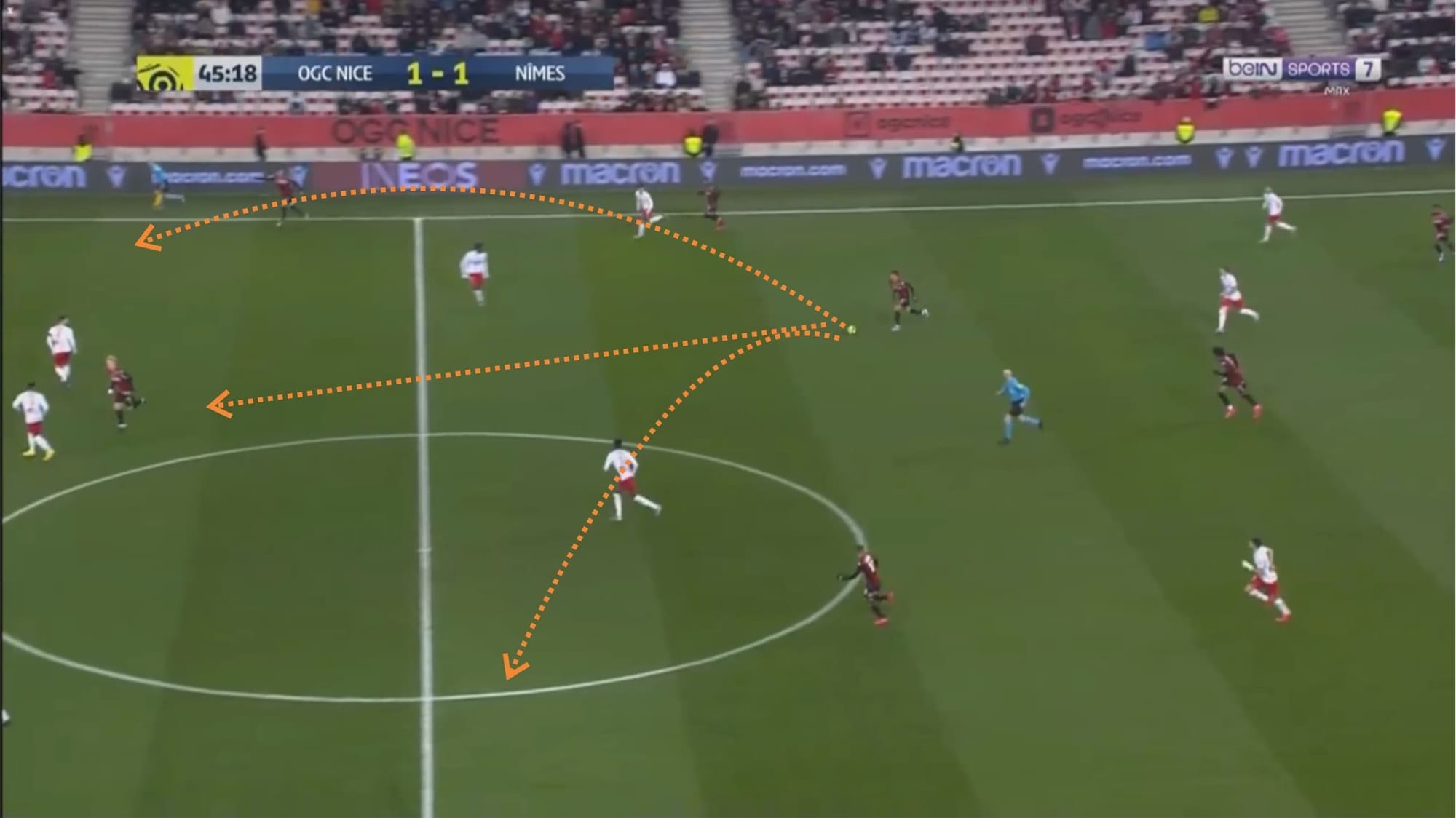

As you can see above, by moving up and making himself available as a progressive option, Nice can both beat Nimes’ attempts at overloading as well as piling pressure into that particular area on the pitch and progress the ball forward.

After receiving the ball, Danio has a lot of time and space to make his decision and execute his action.

At this particular situation, he had several progressive options and also the opportunity to drive forward with the ball himself but in the end he chose to pass the ball to Alexis Claude-Maurice on his left-hand side.

There’s not really one set tactical tendency they use in attack.

As mentioned previously in this tactical analysis, Nice are flexible depending on the opposing team.

Players are allowed freedom and creativity.

In attack, for example, though they mainly like to use short passes and work the ball up into the box patiently, there are times when the backline will improvise and launch a direct long ball into space if the situation allows.

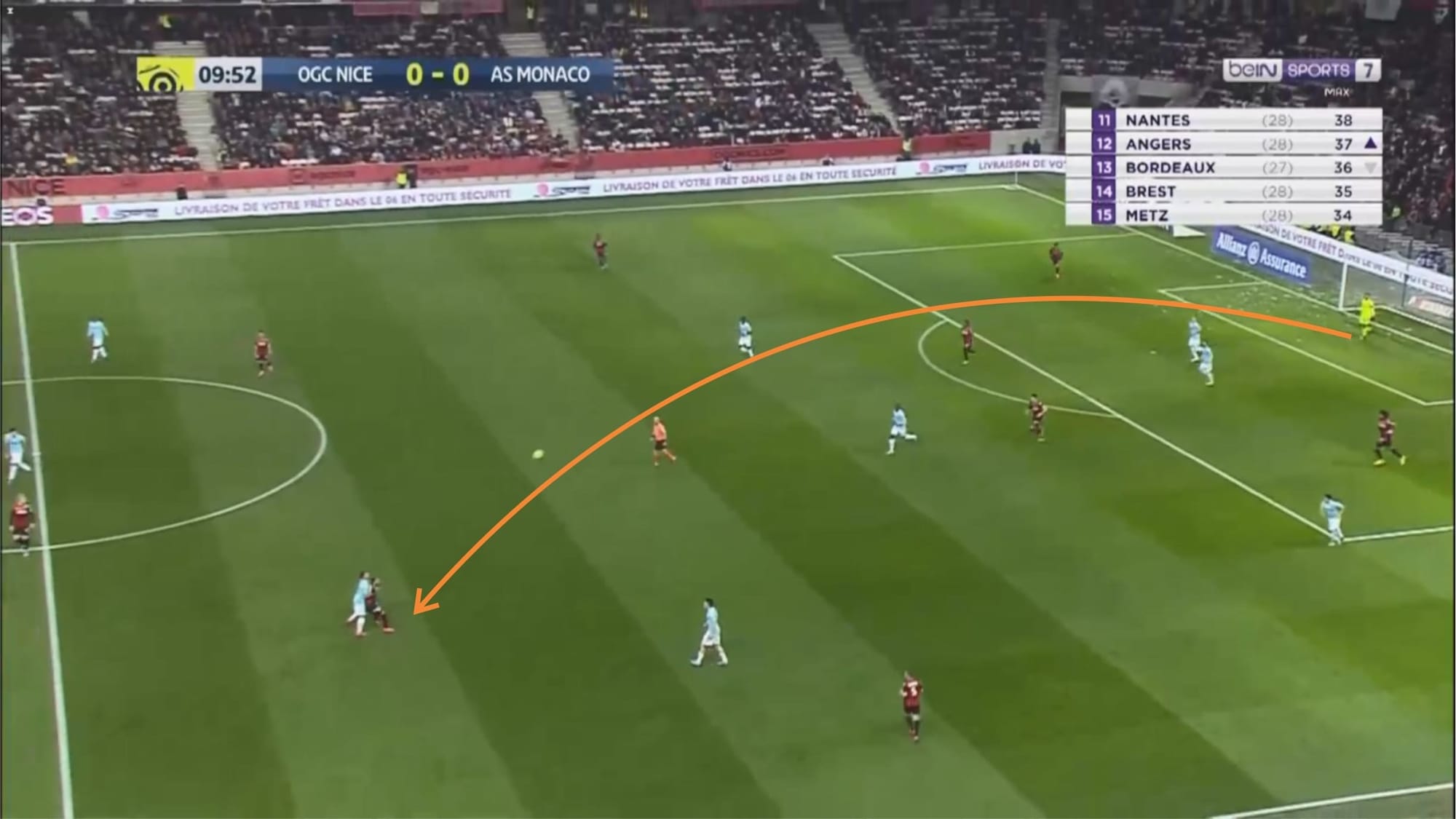

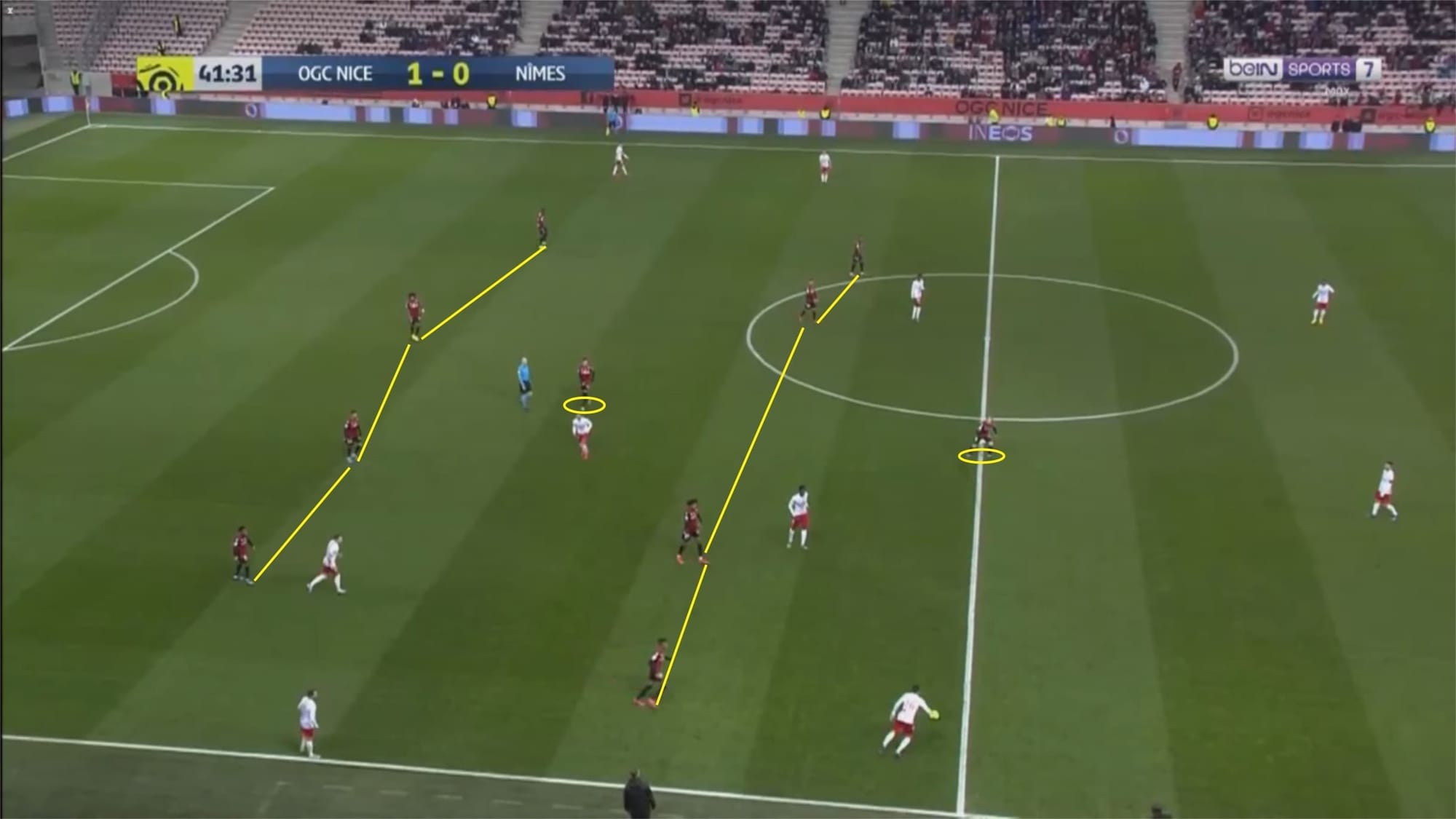

Quick breaks are rather common and as in the example below, whenever there’s an opportunity to break quickly, the ball carrier may choose to be creative and play direct.

In the situation above for example, Dante actually has an opportunity to play the ball towards Kasper Dolberg who’s dropping to receive and looking to link play and play between the lines.

By dropping, Dolberg can potentially unmark himself or drag out his marker and create an opening in behind the defence.

Seeing Dolberg’s movements, Adam Ounas is immediately triggered to make a run and exploit space, making great use of his explosiveness and pace.

Dante saw the run and instead of playing it short, he played a lofted pass into the back of the defence onto the path of Ounas.

However, the winger’s touch was rather poor and he failed to make the most of the situation.

Nice mostly look to combine and create chances centrally, but again, as mentioned previously, they can be flexible.

As teams tend to defend with a narrow and compact defence, crowding the middle-central areas are often inaccessible for Nice and therefore they’d have to make their way around the block and play through the flanks.

Although after getting past the pressure, they will often move the ball back inside either by passing the ball towards a player in a central area or cutting inside with the ball.

Nice only average 10.39 crosses per game which is the second-lowest in Ligue 1, certainly showing that they fancy chance creation through central areas a bit more often.

In the situation above, for example, Ounas plays the ball towards Dolberg who then acts as a wall and bounces the ball onto the path of Arnaud Lusamba.

After receiving the ball, Lusamba has a few choices that he can make.

He can play the ball towards Claude-Maurice in front of him which in turn will prompt his teammates to combine through the middle and exchange quick one-two touch passes to create chances centrally.

Or he can play the ball towards Pierre Lees-Melou who can potentially also unlock the defence with a central through ball or play the ball through towards a free wide player on the left-hand side.

Or, Lusamba can just chip the ball onto the path of his teammate in the wide area himself.

In this particular match, Nice are playing with a 3-5-2 formation which changes into a 3-4-3 formation in attack with one of the central midfielders and one of the strikers turning into wingers who sit narrow and the wing-backs sitting high and wide to stretch the defence.

Though as mentioned before, they tend to use defensive full-backs in a four-man backline and therefore those full-backs won’t provide much support and creativity upfront, Nice can still pose dangers in wide areas with the wingers tending to stay wide instead of tucking in order to stretch the defence while the central advanced midfielders occupy the half-spaces and provide support inside areas whenever needed.

Nice tend to switch play often, exploiting underloaded areas and taking advantage of their wide players’ explosiveness and creativity but they tend to move the ball to the middle first before playing a diagonal switch of play rather than playing a long pass from one flank to the other.

Nice’s main weakness when in possession seems to be in collecting offensive second balls.

They don’t seem to be the kind of team that would deliberately play a pass forward and let the opposing team win the aerial duel before then pressing to win the second ball.

Usually when launching the ball forward, the ball carrier at the back will look instead to play the ball onto space at the back of the defence or play the ball into the feet of a teammate.

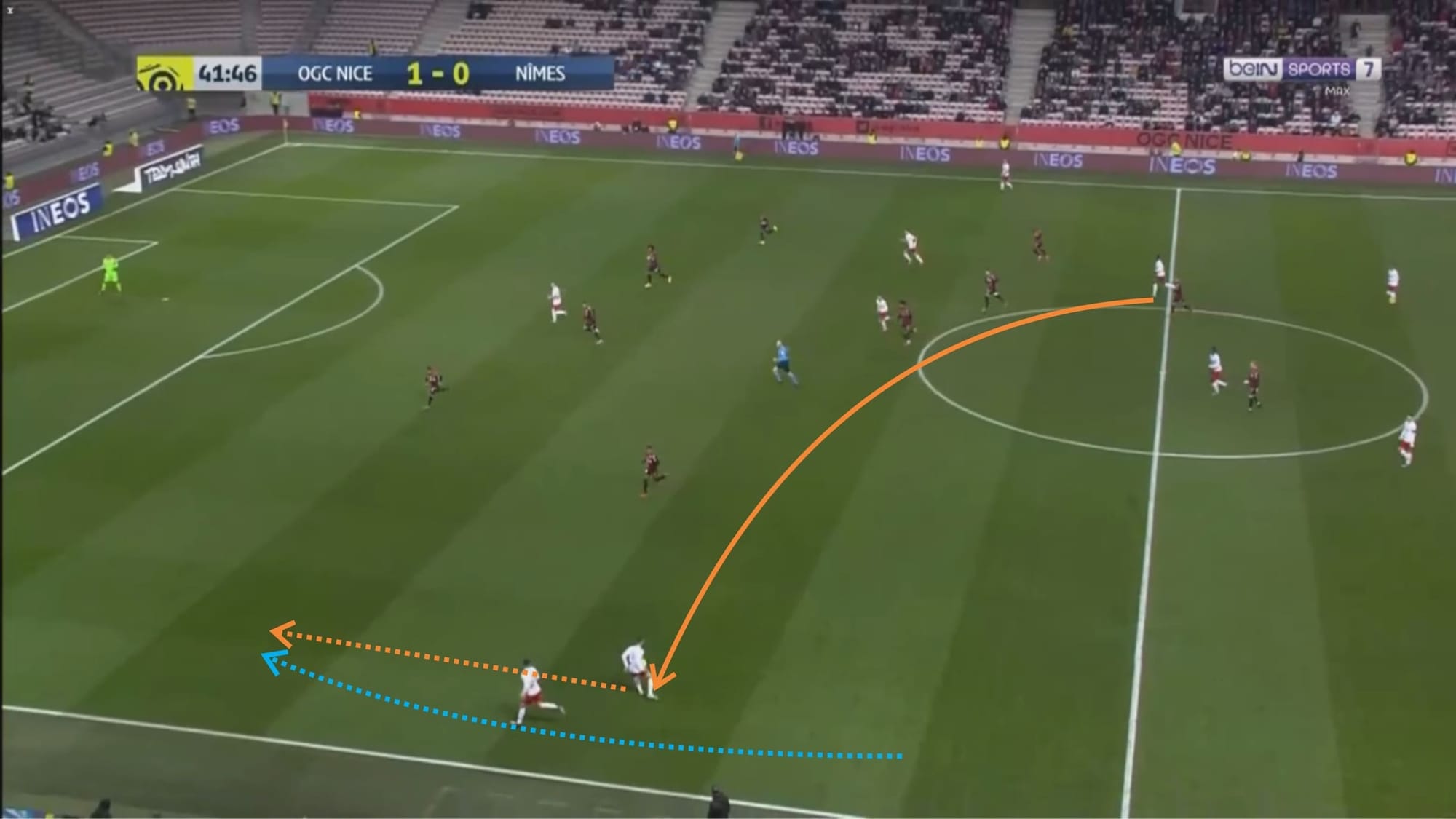

This can be seen in the picture below.

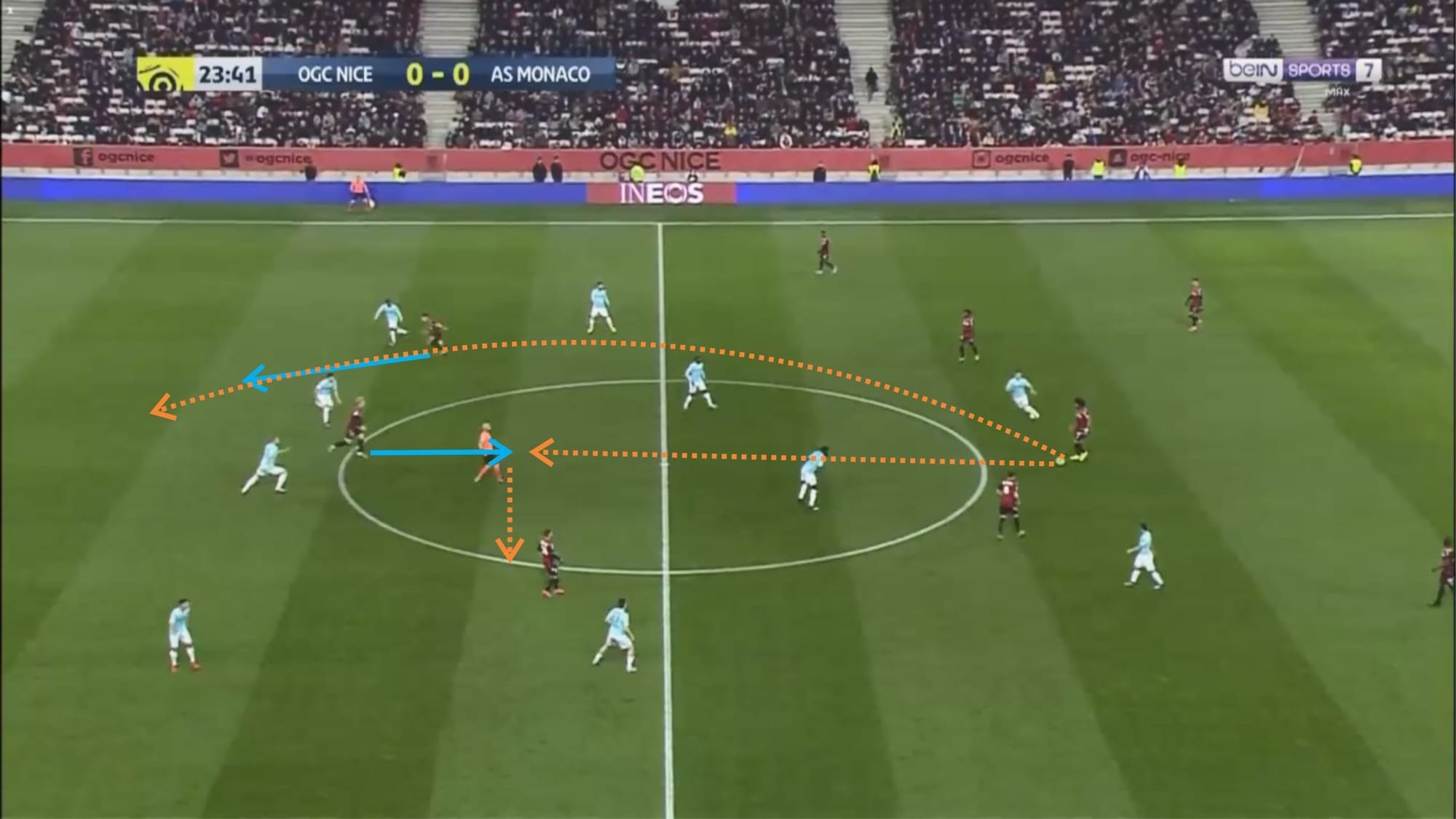

Again, on paper Nice appear to play with a 3-5-2 formation that changes into a 3-4-3 when in possession against Monaco.

With Monaco exerting an aggressive pressure and using a high block as well as utilising a combination of man and passing lane-oriented approach, Nice were having difficulties playing out from the back and often had to resort to lofting the ball forward to exit pressure.

In the picture, the three centre-backs sit deep and in the same line (Sarr not in the frame).

The two pivots drop even deeper to provide support to help the team play out of pressure.

There are several problems in Nice’s attempts at winning offensive second balls.

Firstly the structure shows that although Monaco have more players around the ball, Nice still have several players ready to pounce on the second ball as well.

However, due to the structure and their tendency to have more players drop to offer support when pressed high in the build-up, the option upfront becomes limited, especially central options.

In the picture above, Claude-Maurice may be able to play the ball towards Ounas (right-winger), Riza Durmisi (left wing-back), or Dolberg (striker) but all these options are rather difficult, especially as he’s under pressure when challenging for the aerial ball.

Aside from the structure, Nice’s lack of intensity and aggression when pressing/counter-pressing to win the second ball may often put themselves in danger as opponents can recover possession inside their own half and resume their attack quickly.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re always passive and rarely win second balls but the gap in the structure, as well as lack of aggression and intensity when duelling to win offensive second balls, usually happens often enough in the game that the opposing team may take advantage from their vulnerability.

Luckily, in the situation above, the pass is accurate and Claude-Maurice can control the ball albeit in a rather uncomfortable fashion as he’s under pressure.

Narrow and compact defence

What stands out in Nice’s defence is their narrow and compact shape as well as flexibility in defence.

Depending on the opposition they’re facing, the formation they use in defence may vary and may even change numerous times mid-game.

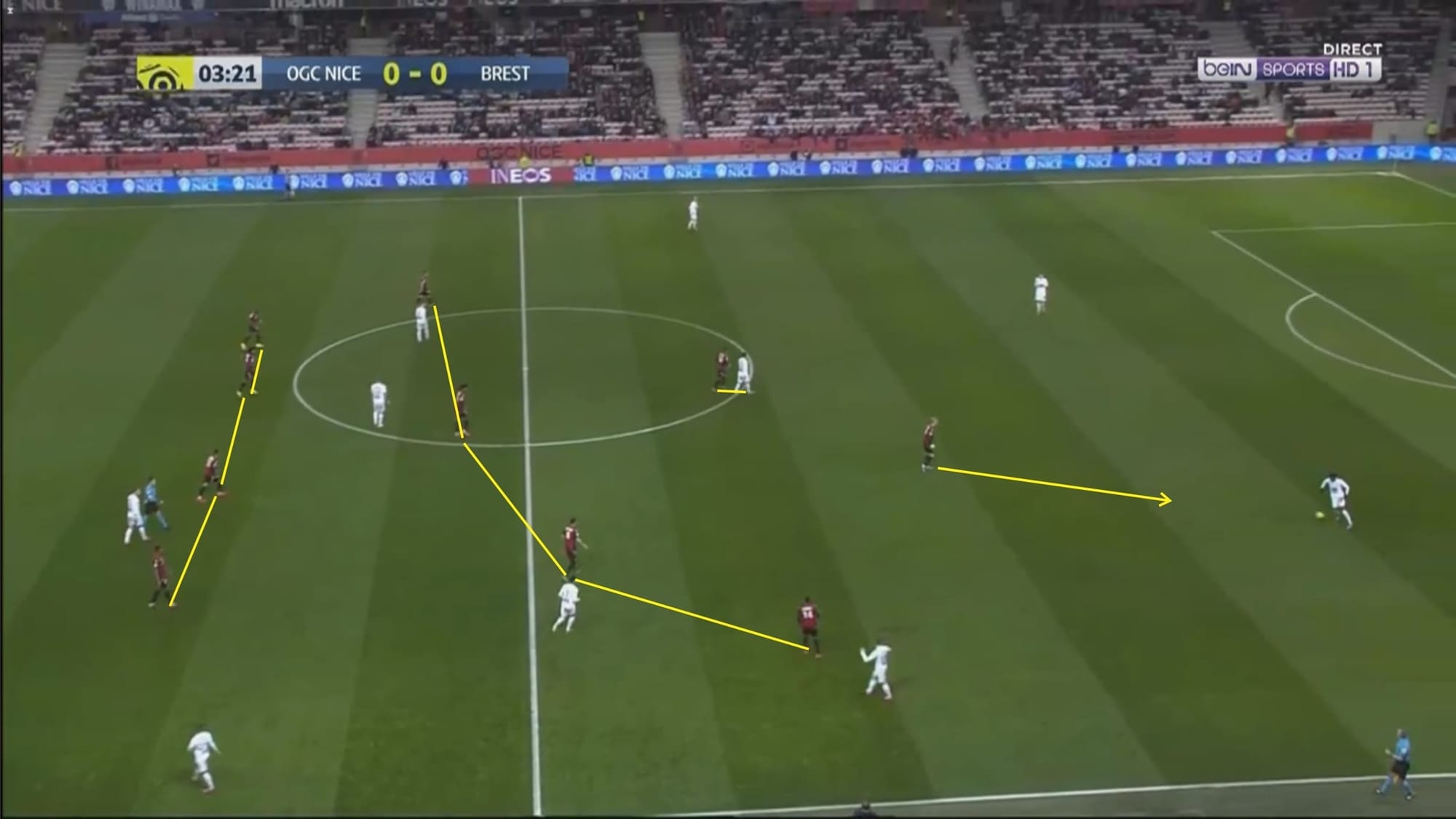

In the image above, Nice play with a 4-4-1-1 formation against Brest and defend with a 4-4-2 with one man pressing the ball while the other man in the first line marks the pivot.

They tend to defend with a medium-high block, allowing the opposing team to come out of their penalty box but restricting central access to progress by staying compact and narrow.

Once the ball carrier moves high enough, one of the two forwards will look to press the ball, aiming to steer the ball carrier into bringing the ball close to the flank while blocking his passing lane towards his teammate in order to isolate him.

Nice mainly defend with a mix of man-marking and zonal orientation.

When the ball is moved wide, the ball-near players tend to be man-oriented when marking in order to close off options and prevent progression.

However, certain passing lanes sometimes are deliberately left open, luring the opposing player into playing the ball towards that area.

Their approach can be seen a bit more clearly in the picture below.

In the image above Nice (red team) defend with a 4-4-2 block against the blue team with a 4-4-2 system.

In the picture above, the opposing left centre-back initially wants to play the ball towards his left-back but seeing Nice’s right-winger edging closer in anticipation when the ball is played, the ball carrier decides to pass the ball laterally towards his partner at the back.

When the lateral pass is played, the attacking midfielder then leaves the opposing pivot and presses the ball whilst Nice’s striker moves closer to mark the pivot.

At certain occasions, Nice may press the ball with two players at once with the striker and attacking midfielder closing the ball carrier down while both block the passing lane towards the left centre-back and the pivot each.

As mentioned previously, the presser will look to steer the ball to the flank and they may become man-oriented when the ball is in a wide area but certain passing lanes may deliberately be left open.

For example, in the image above, the opposing ball carrier is allowed to play the ball into the feet of a player in the half-space.

However, once the ball is played into the ‘free’ player, Nice will then immediately execute their pressing trap and swarm the ball carrier and isolating him, causing panic and forcing mistake whilst potentially winning the ball in the process.

The pressing trap is flexible and doesn’t have to happen in the half-space.

At times, an opposing wide player can also be left free deliberately with Nice’s defender sitting narrow instead of staying wide and staying close.

With the other options usually inaccessible/marked by other teammates, the opponent can be lured to move the ball towards the ‘free’ player.

However, like in the picture above, once the ball is played towards the ‘free’ player, Nice’s pressing trap is immediately executed, forcing the ball receiver to rush his decision and execution.

Their pressure is only moderately aggressive and rather than forcing the opposing player into a mistake very early in their build-up play by defending with a high block and pressing very aggressively.

Nice look to force the opposing team into playing the ball or moving into certain areas where they can overload and isolate that area as well as pile pressure in order to win the ball back.

Nice average 61.44 defensive duels per game with a success rate of 59.9% and a lot of their successful defensive duels are usually inside the middle third or in their defensive third.

There are a limited amount of defensive duels deep inside the opposing half.

Their PPDA of 12.7 (fifth-highest in Ligue 1) also proves that they may not be the most aggressive team when it comes to pressing.

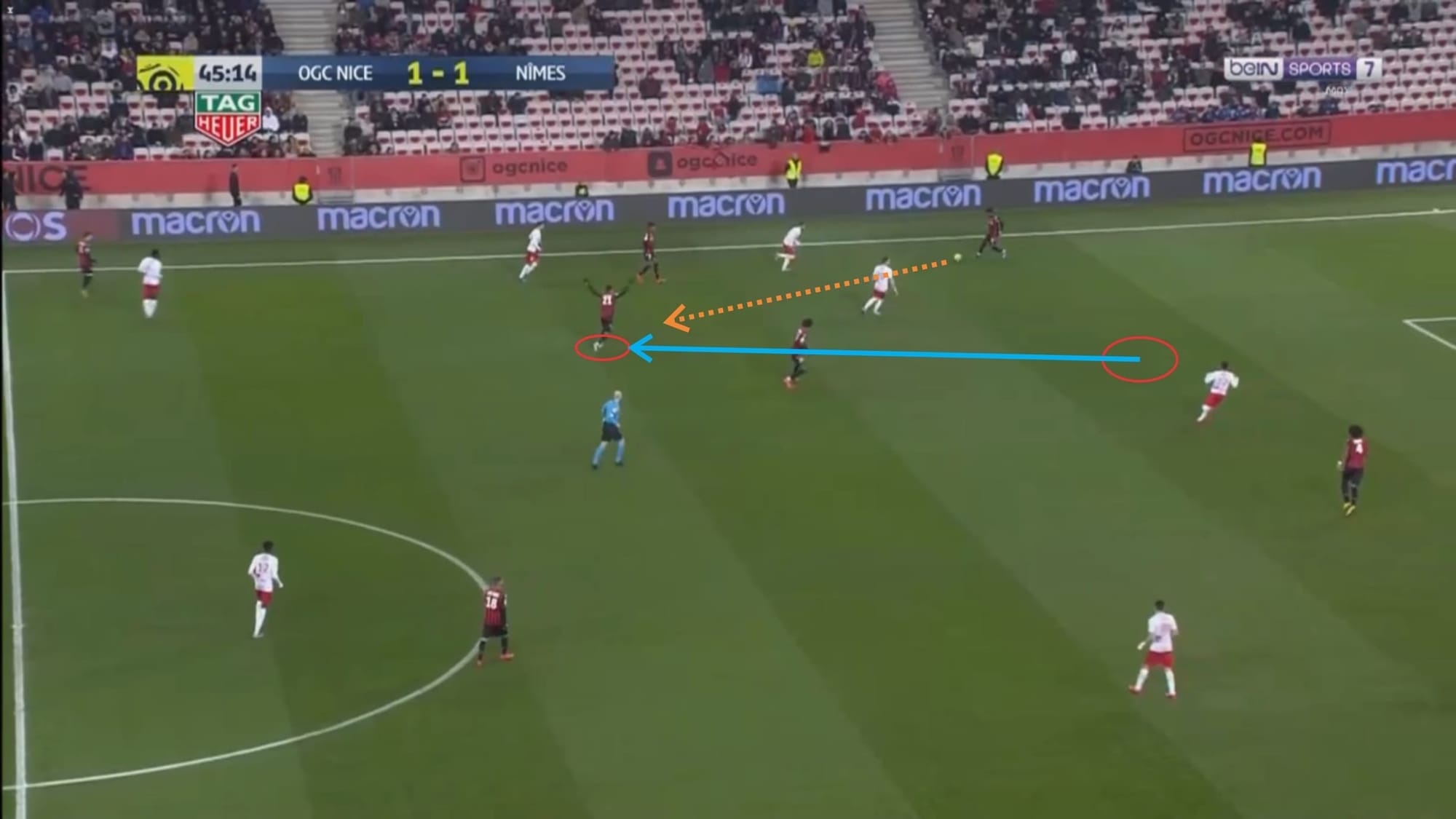

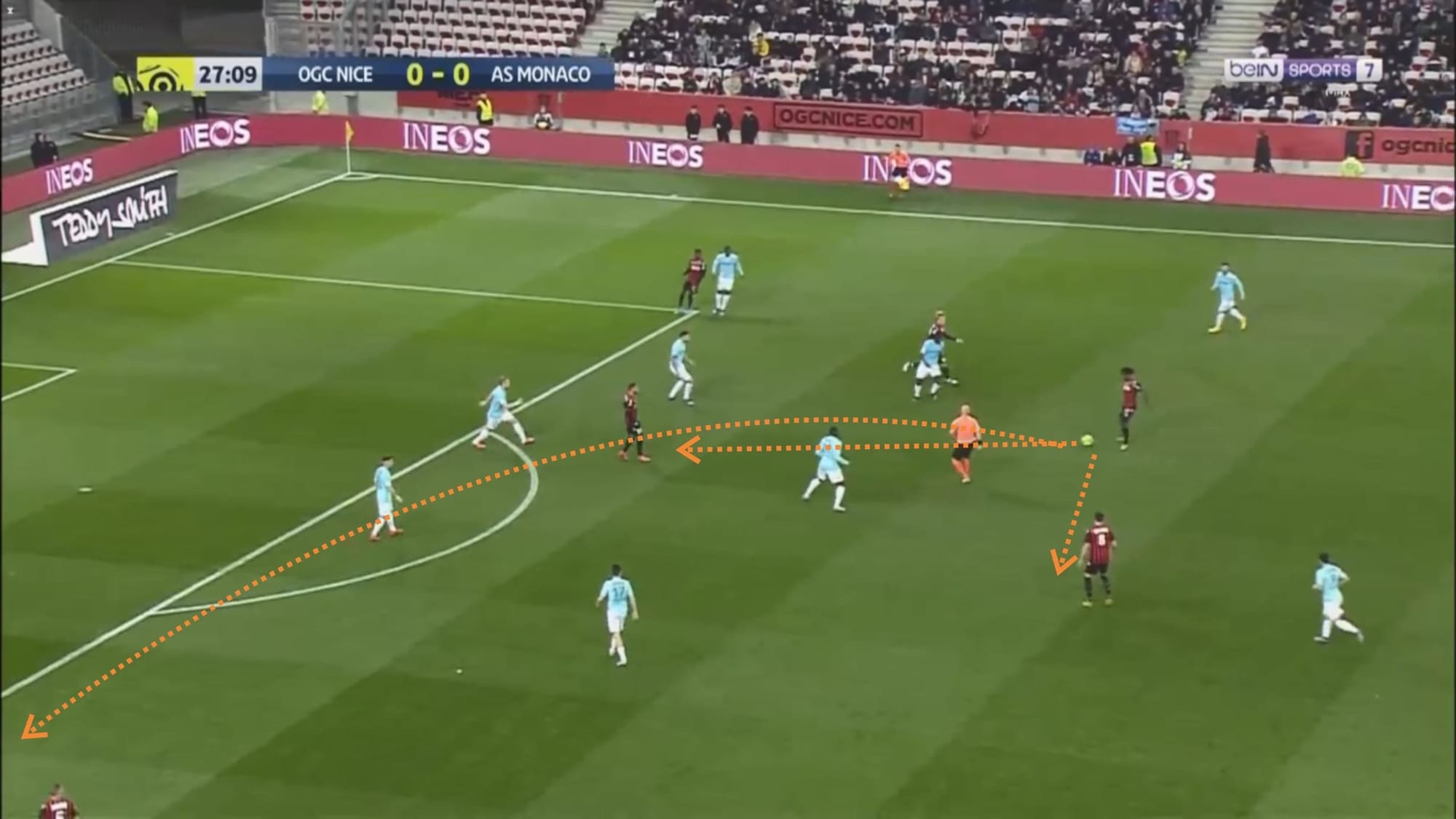

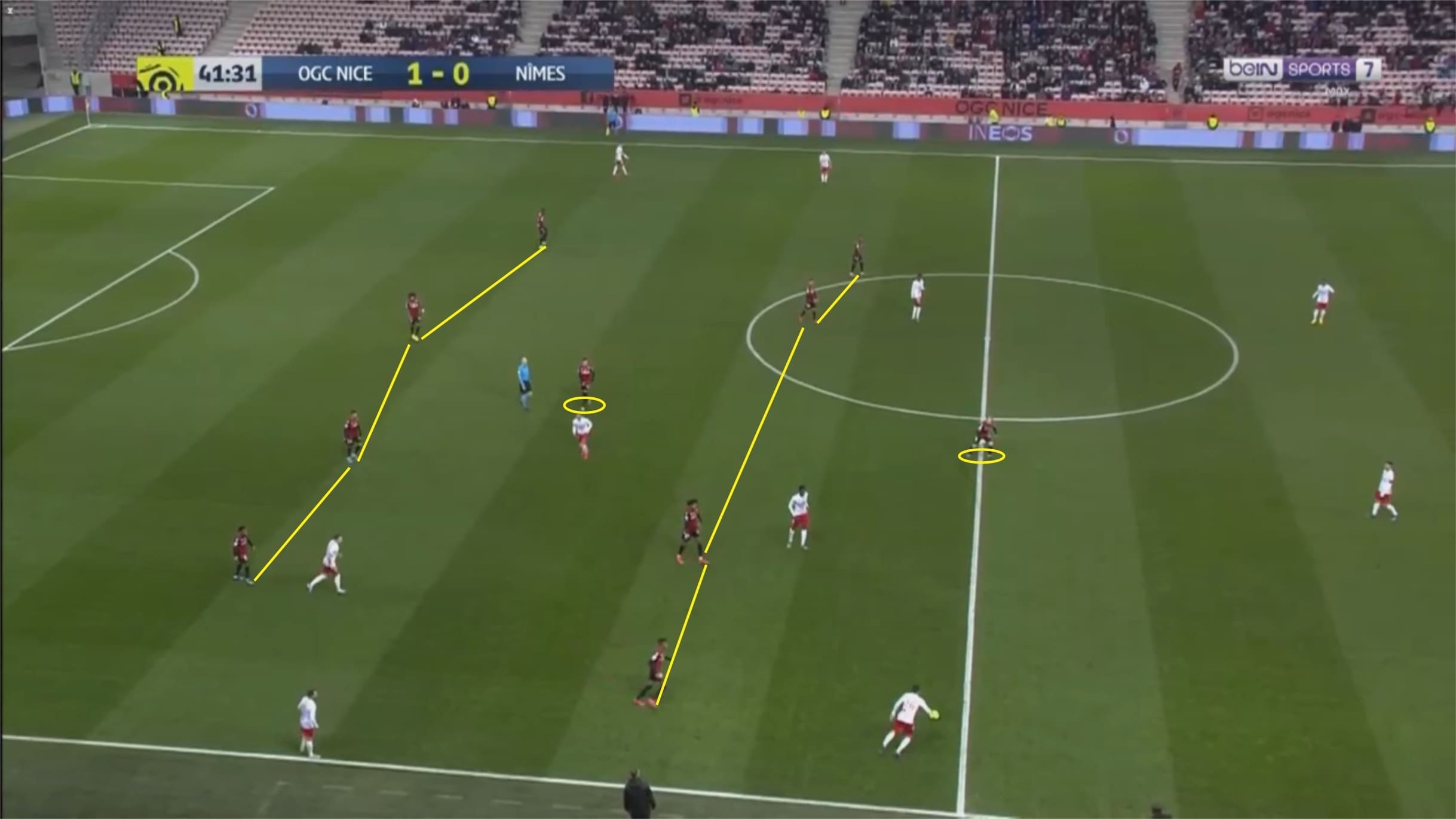

The image above shows Nice’s flexibility in defence.

In this particular match, Nice actually play with a 4-4-2 formation on paper, but in reality, the actual shape that they take up vary in attack and defence.

Against Nimes’ double pivot in a 4-2-3-1 formation, one of Nice’s forwards drops back and man marks one of the pivots.

Meanwhile, one of Nice’s central midfielders sits a bit higher up to stay close to the other pivot and the other Nice central midfielder hold his position in between the lines and defends against Nimes’ attacking midfielder.

This prevents central progression and combination, denying Nimes access and forcing them to play around the block instead.

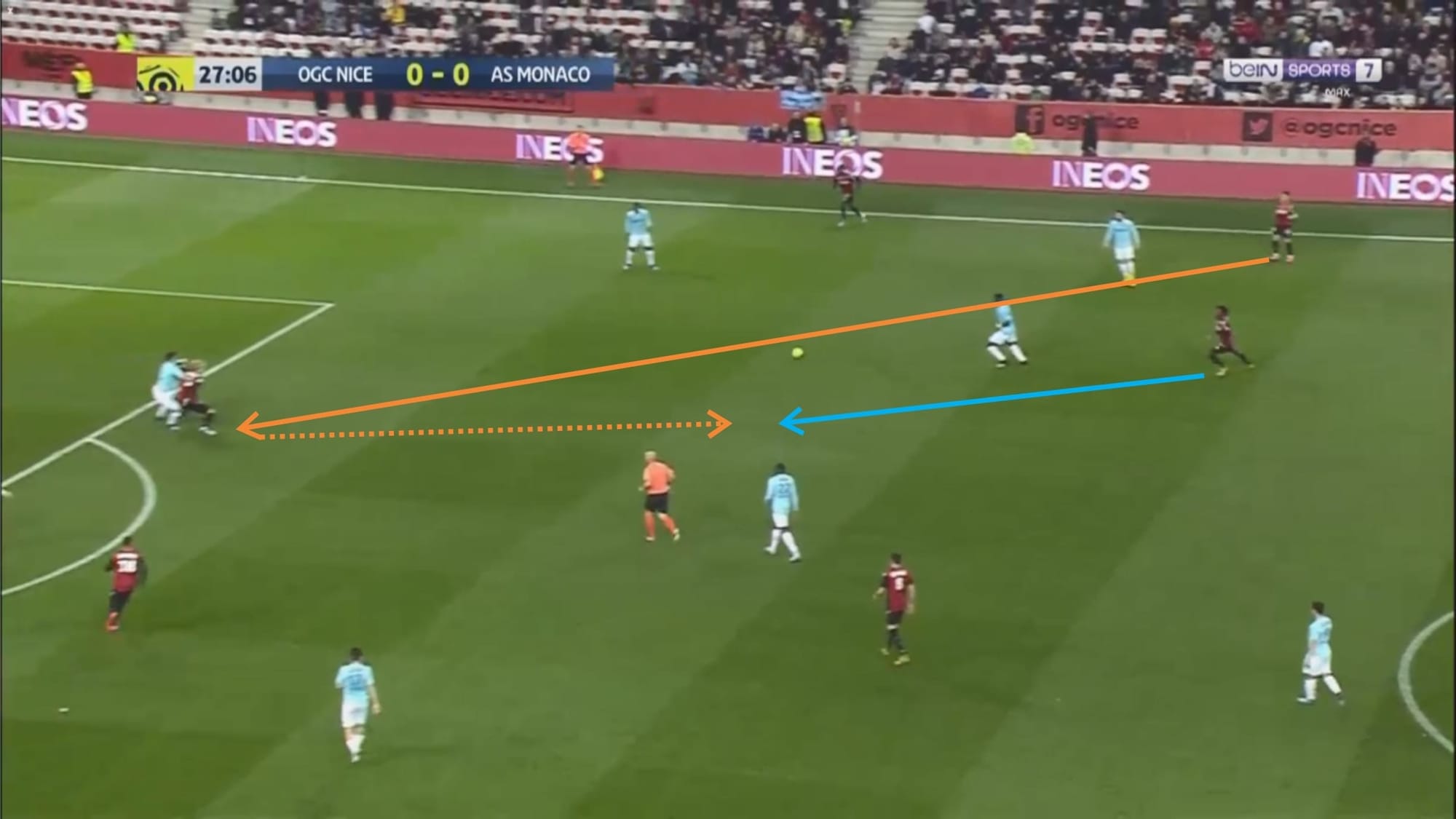

However, their highly narrow and compact shape comes at a cost.

Wide areas may become exposed and they certainly will be vulnerable against teams that switch play often as they’d be forced to move their block often testing their discipline.

In the image above, for example, one of Nimes’ pivots manages to control the ball and spot a free teammate on the other flank.

The ball carrier disguises his pass well and delivers it accurately.

Nice will then have to move their block across quickly but their opponents are quicker.

Once the Nimes winger receives the ball on the underloaded area, he passes the ball through into the path of his overlapping teammate who was immediately met with a 1v1 situation with Nice’s full-back.

As the opposing full-back has time and space, he manages to execute the cross comfortably and manages to find his teammate inside the box although in the end, his teammate’s shot ends up wide of the goal.

Nice allow a pretty high amount of 15.47 crosses into their box per game and 31.9% of those crosses end up being accurate.

Nice are usually pretty quick when moving the block across the field when the ball is switched towards the underloaded flank.

But there are, of course, certain times when the opponents are much quicker in moving the ball and Nice don’t have much time to move across the field and block the cross, or at least press the crosser in order to force a lower quality cross.

Conclusion

Nice are one of the highest-scoring team in Ligue 1 this season, scoring 41 goals in the league, joint fourth-highest alongside Marseille.

However, statistically, they’re not the most solid in defence: conceding 38 goals in the league, sixth-highest amount of goals conceded.

Vieira’s flexible philosophy and tactics have worked wonders for his youthful Nice team and athough they are still far from perfect, there are a lot of interesting points to talk about.

If Ligue 1 is going to be resumed in the future, surely Dante and co.

will be looking to catch up with the other teams at the top of the table and force their way into a European spot.

With them being eliminated already from Coupe de la Ligue and Coupe de France, Vieira and his side can focus solely on finishing as high as possible in the league.

Comments