The xG of a penalty kick is 0.76, meaning a penalty kick is expected to result in a goal 76% of the time. However, after extensive research of 224 penalty kicks taken during the 2021/22 season in the Premier League and La Liga, it is clear that certain factors can massively increase the chance of a penalty being converted.

First of all, it is important to mention that while this analysis will disclose the trends amongst successful penalties and methods players could use to improve the success of a penalty kick, at the end of the day, a penalty is dependent on many different factors, such as the taker’s ball striking technique, which is not being taken into account at the moment. Even if a penalty uses the common successful trends in this article, it is reliant on each player and their ability to strike the ball accurately.

Inspired by Geir Jordet’s insights into the psychological aspect of penalty kicks, with players taking their time before the first step of their run-up, my research aligns with the information presented by him. 85% of penalties taken by players who wait over 5 seconds after the referee’s whistle result in goals, while the figure drops to 81% for players who begin their run-up within 3-5 seconds of the whistle. This figure then drops down to 75% for any players who begin their run-up within 3 seconds of the referee’s signal. Players who can compose themselves before the penalty kick run-up are able to significantly increase the chance of scoring a penalty. This analysis will focus on the different run-ups, and the ability of an individual to wait and relax under the pressure to execute their run-up & kick is essential.

In this tactical analysis, we will examine the tactics behind different run-ups for penalty kicks and examine their benefits in depth. This set-piece analysis will find the advantages of different penalty run-ups and explain why changing step length and speed is crucial to negating a goalkeeper’s power step and, therefore, giving attackers more space to aim at in the goal.

Issues with Consistent Run-Ups

Consistent run-ups resulted in goals on 76% of occasions, while penalty run-ups, which included stutters or players accelerating/decelerating, saw a rise to 80% success rates.

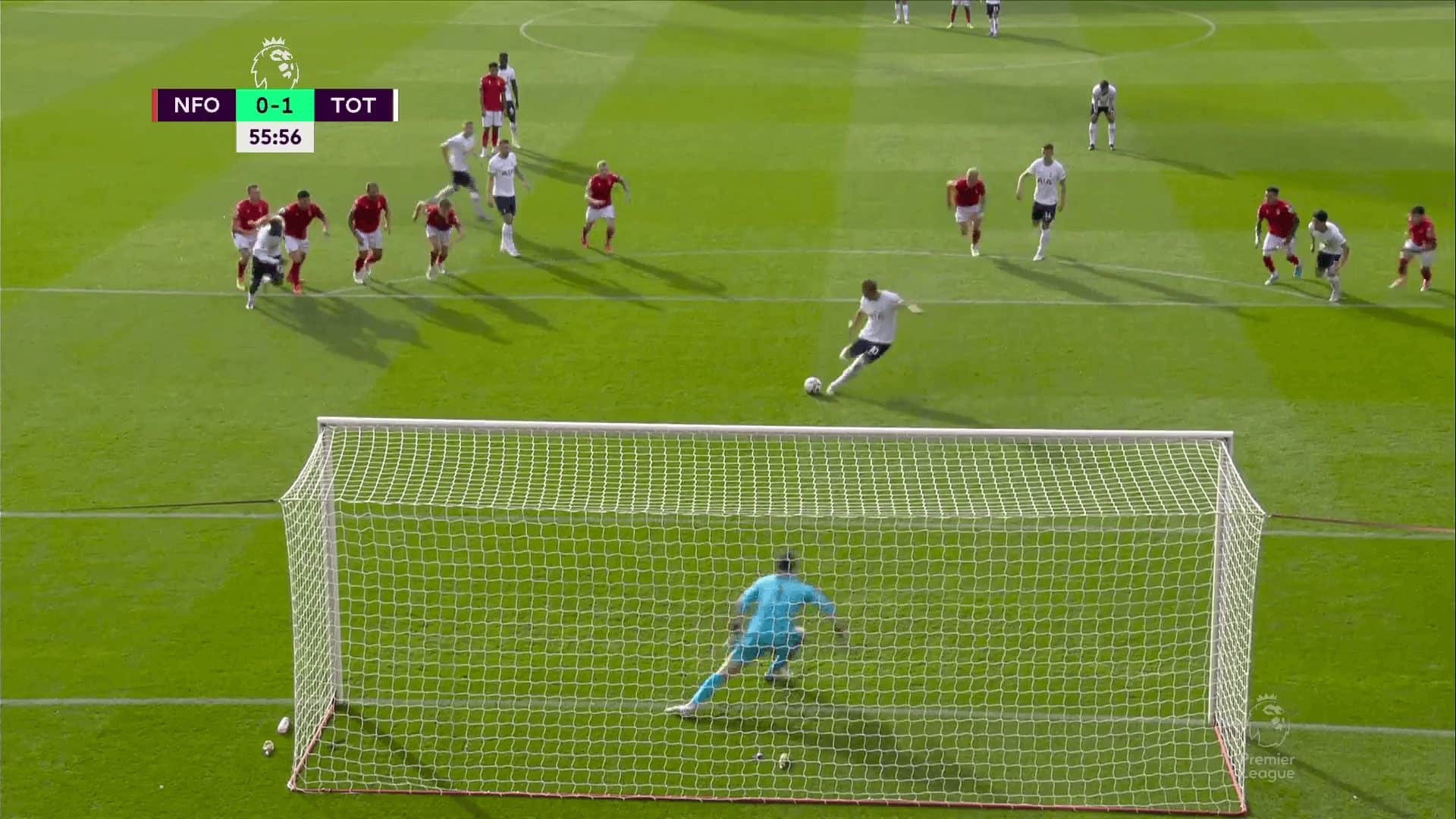

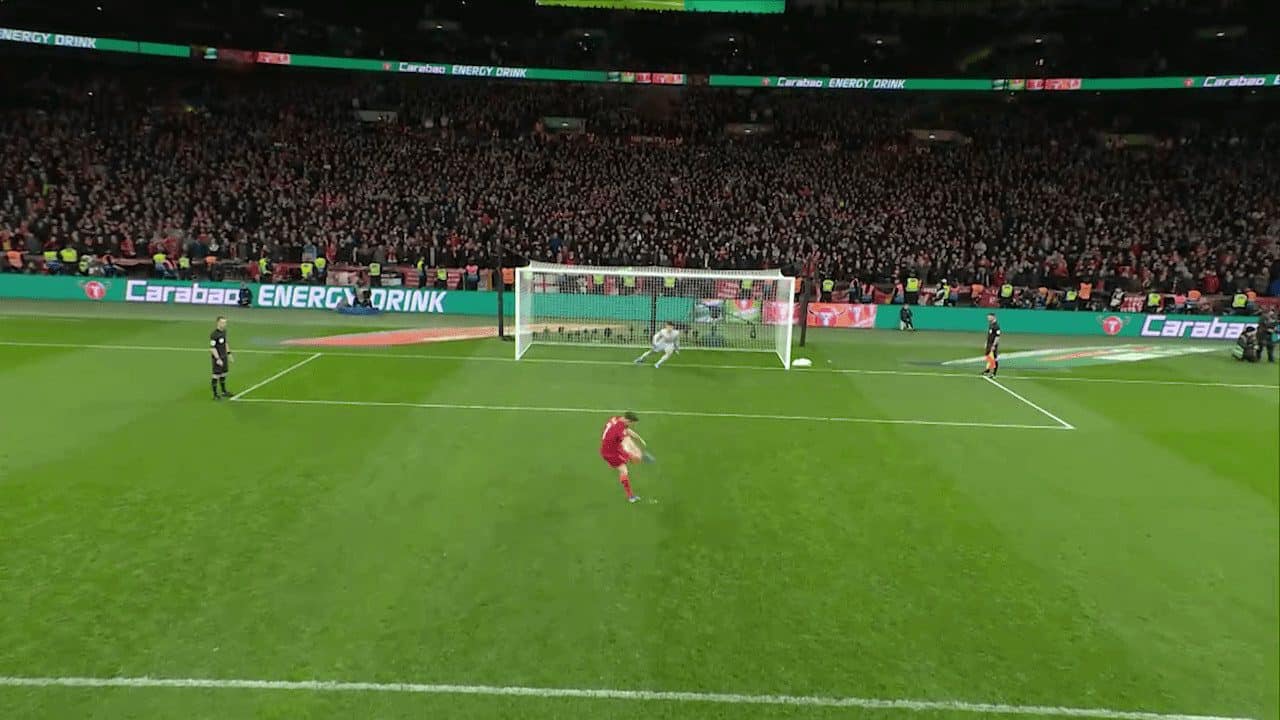

When a goalkeeper faces a player with a steady movement towards the ball during the run-up, they can assume the moment at which the player will strike the ball and time when to dive and perform the power step (the step which allows the goalkeeper to generate the spring to reach the post). In the example below, Dean Henderson knows how Harry Kane prepares for a penalty, and he is able to move early before the ball is kicked when attempting to save the penalty. There is no threat of Kane stuttering, so Henderson can afford to move early, with no threat of Kane reacting to the keeper’s movements and changing his decision. The early power step means Henderson can cover the entire bottom right of the goal, meaning if he does guess the right way, he is likely to save the penalty, as he does in this particular example.

Bayern Munich‘s Harry Kane possesses excellent ball striking, which means that he is often able to hit the ball into the top corner, giving goalkeepers no chance even if they guess early. However, his consistent run-up gives goalkeepers the chance to guess early, meaning he doesn’t give himself the best possible chance of scoring penalties, as goalkeepers have the chance of saving the strike if they guess a bottom corner correctly.

Long Run-Ups

In order to disrupt a goalkeeper’s power step, thus preventing them from generating the spring to reach the bottom corners of the goal, players have started using different methods during the run-up to a penalty kick. Long run-ups involving players taking nine steps or more have resulted in a 100% success rate from the data my research has found, although that did only include six attempts.

The longer a run-up is, the more opportunities a player has to vary the speed and step length of their run-up. When a player does alter their run-up, the goalkeeper no longer has the chance of being able to accurately predict the moment when the kick will be taken, thus stopping them from making that power step early, meaning that they are unable to reach the bottom corners of the goal. By only varying the step length and speed of their run-up, a penalty taker will have been able to create the space needed in the bottom corner to score a goal, as long as they are able to consistently place the ball in that very spot.

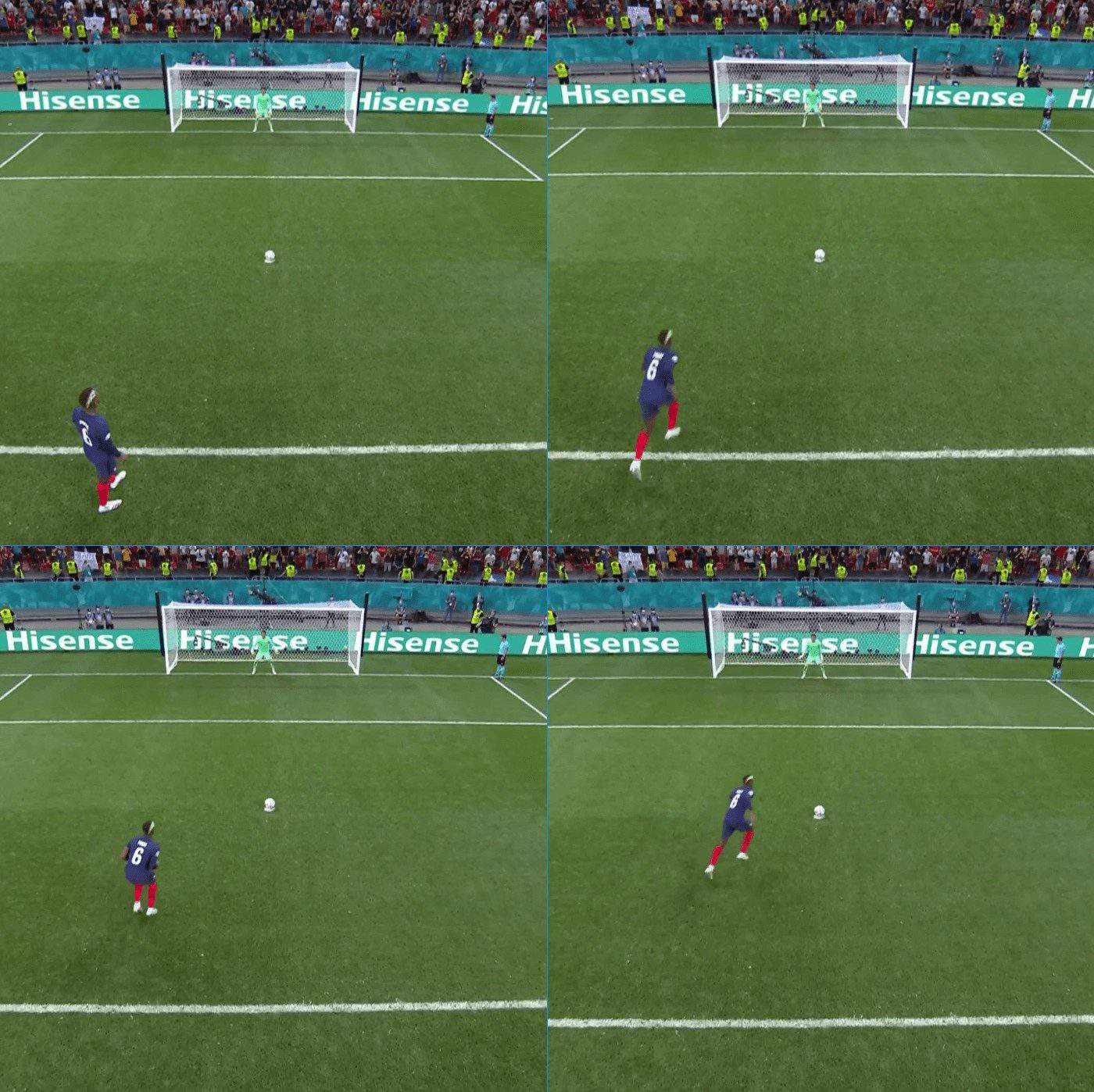

As we can see in the example below, Paul Pogba’s long run-up gives him numerous opportunities to vary his run-up, including both accelerations and decelerations. He originally begins his run-up through two strong large steps, making the goalkeeper think the shot is coming instantly. However, he then slows down by taking multiple tiny steps. At this moment, Sommer (in goal) does not have the option of diving early as the little steps mean that, at that rate, Pogba is still a long time away from taking the shot. Yet again, Pogba instantly speeds up his run-up, where he attempts to catch Sommer on his heels as the shot comes much sooner than it would have if he had carried on with the mini steps. This mental gymnastics causes Sommer to be rooted to his line and unable to move early to increase his chance of saving the shot.

Finally, at the point that Pogba is about to strike the ball, Sommer doesn’t have the time to make the power step to save the strike. Sommer’s weight is still on his back foot, and he is still planting his foot with which he is going to make the dive. As a result, he doesn’t have the time to reach the bottom corner if the ball does go there due to the late dive.

A player’s run-up can disrupt the goalkeeper’s ability to dive in two main ways: acceleration and deceleration.

The example of Pogba showed elements of both, but ultimately, prior to the shot being taken, Pogba’s run-up accelerates from a slow pace to a fast pace.

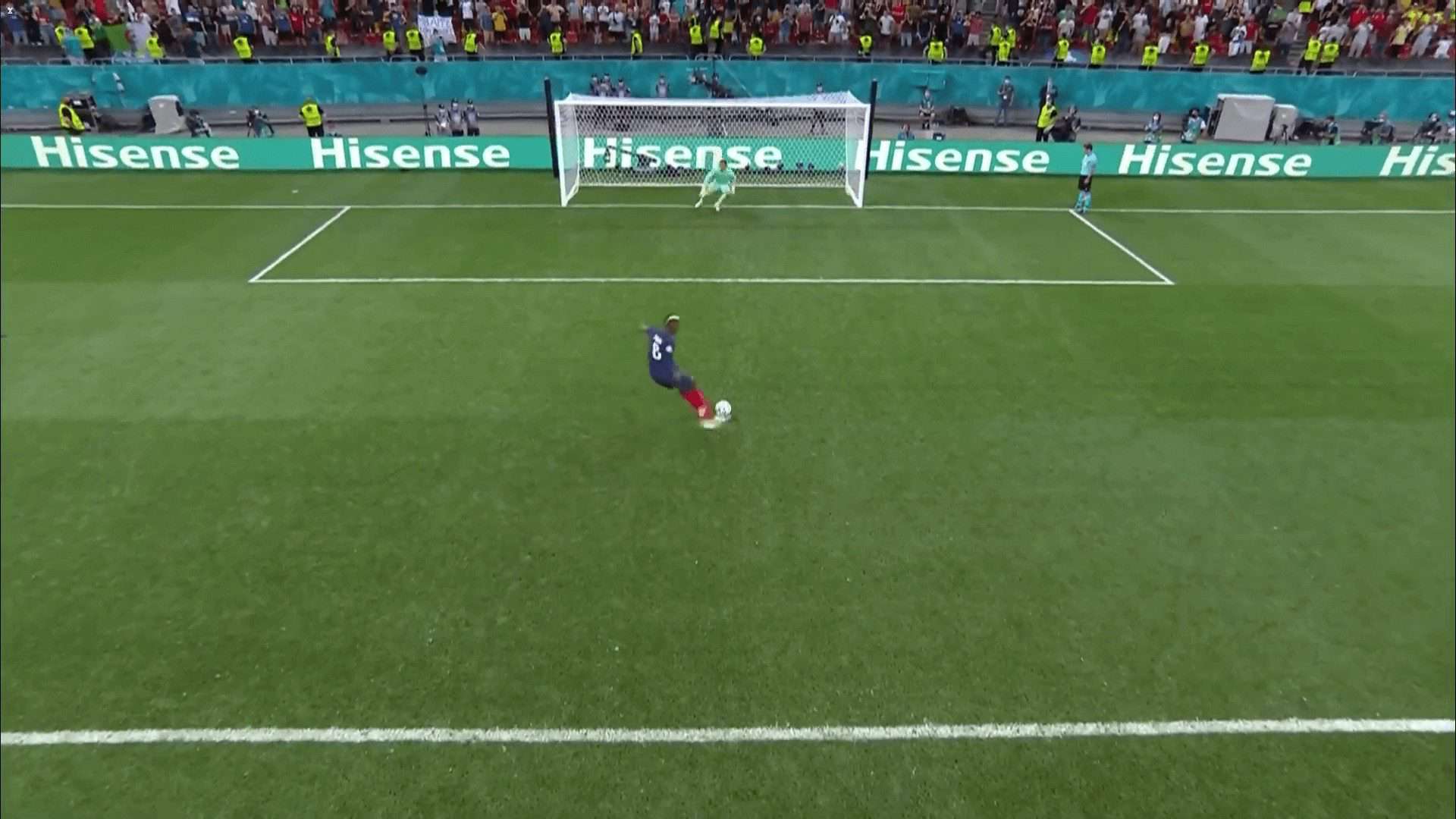

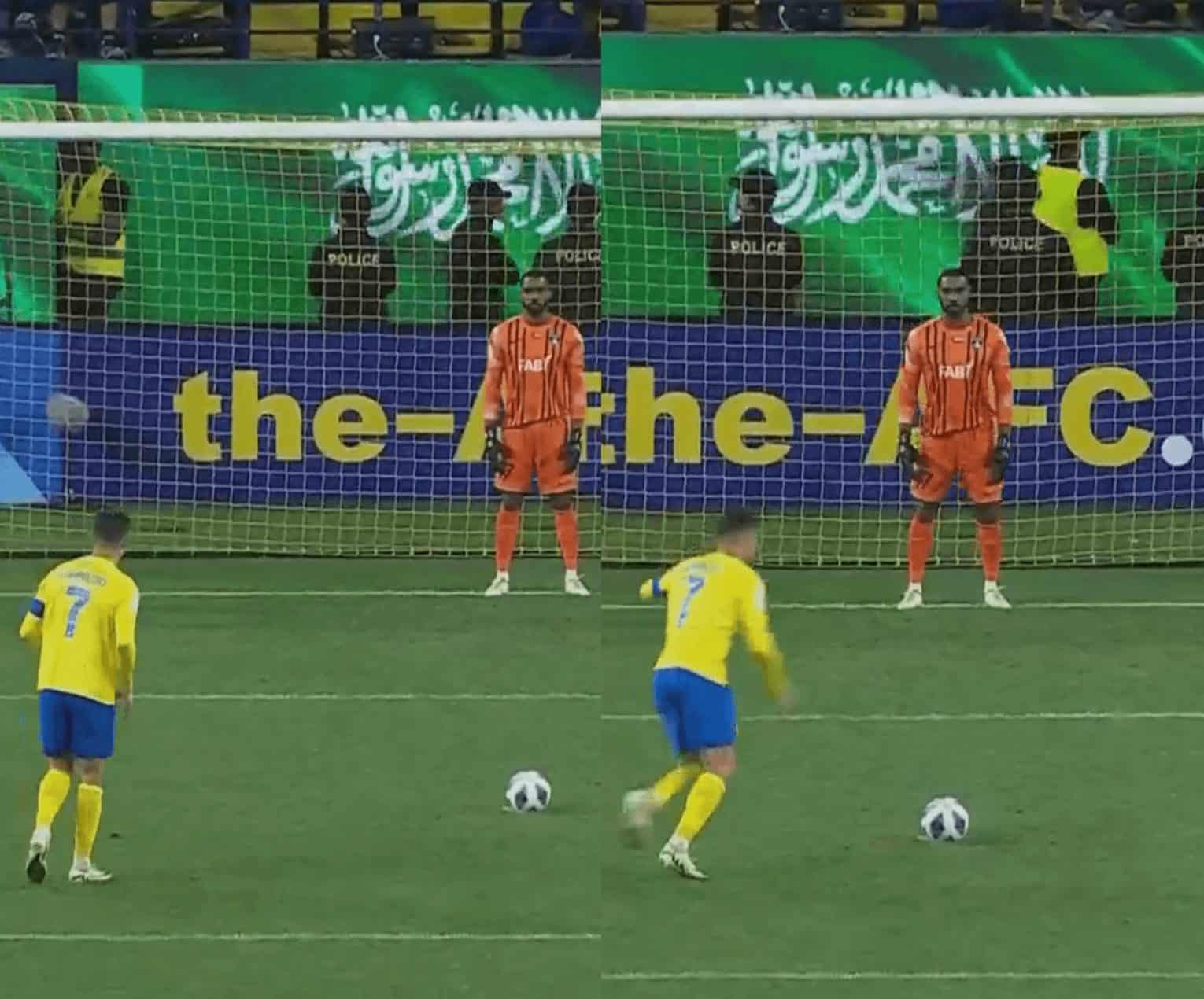

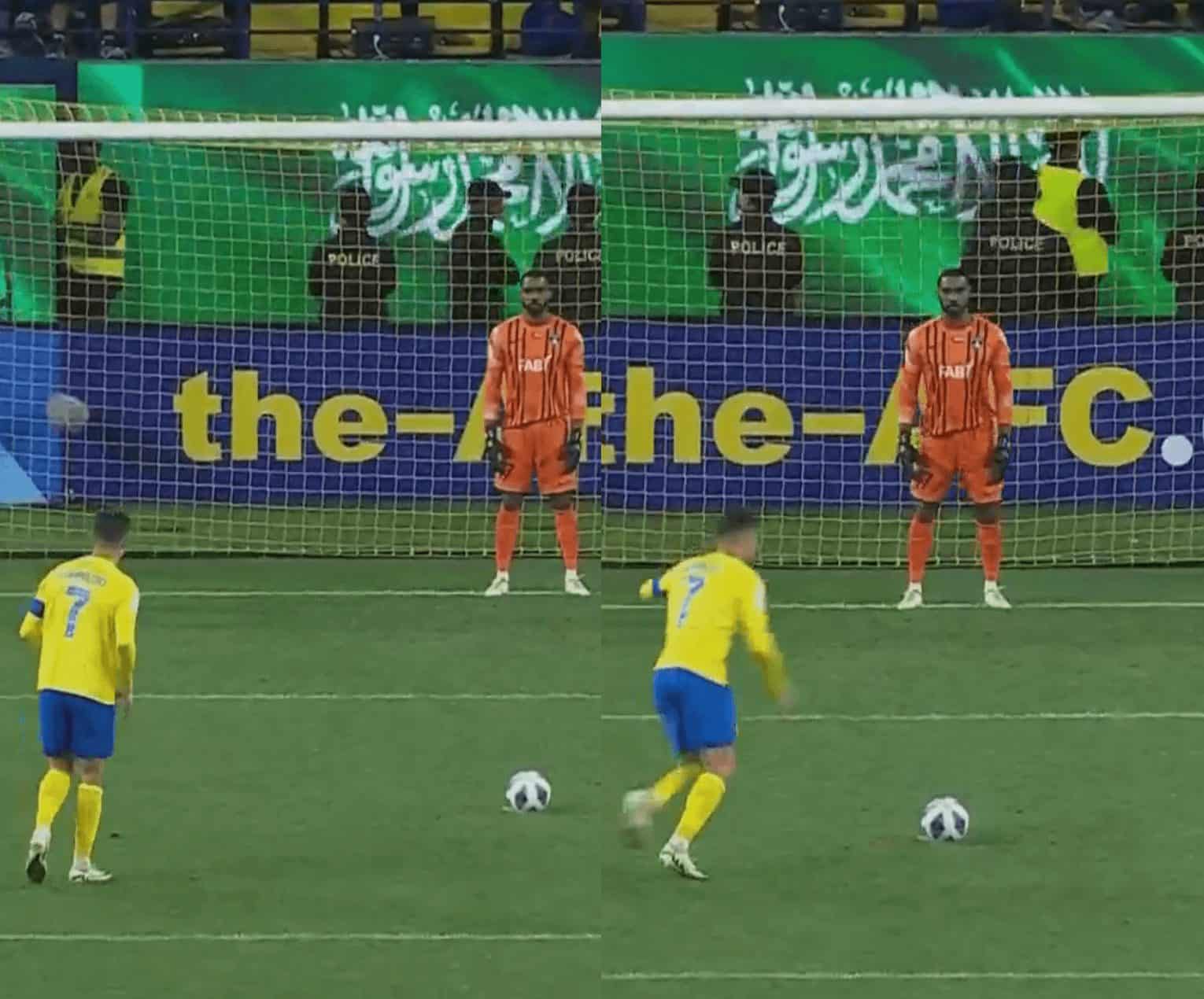

Cristiano Ronaldo already had a strong penalty record throughout his career due to his ability to remain calm under pressure and his immense ball striking. However, following his departure from Manchester United, he has continued to prove why he’s been a top professional for so long. Since he arrived in Saudi Arabia, Ronaldo has evolved his penalty run-up to give himself the best possible chance of scoring every penalty kick. As we can see from the two images below, Ronaldo’s run-up starts at a walking pace whilst maintaining eye contact with the goalkeeper. He then speeds up in the final couple of steps before his kick to generate the power to put the ball past the goalkeeper. The sudden acceleration doesn’t give goalkeepers the time to make their power step and allows Ronaldo to put the ball into the bottom corner comfortably. Since this adaptation to his penalty run-up, Ronaldo has scored all 18 of his penalty kicks, upping his overall career penalty kick success rate to 85%.

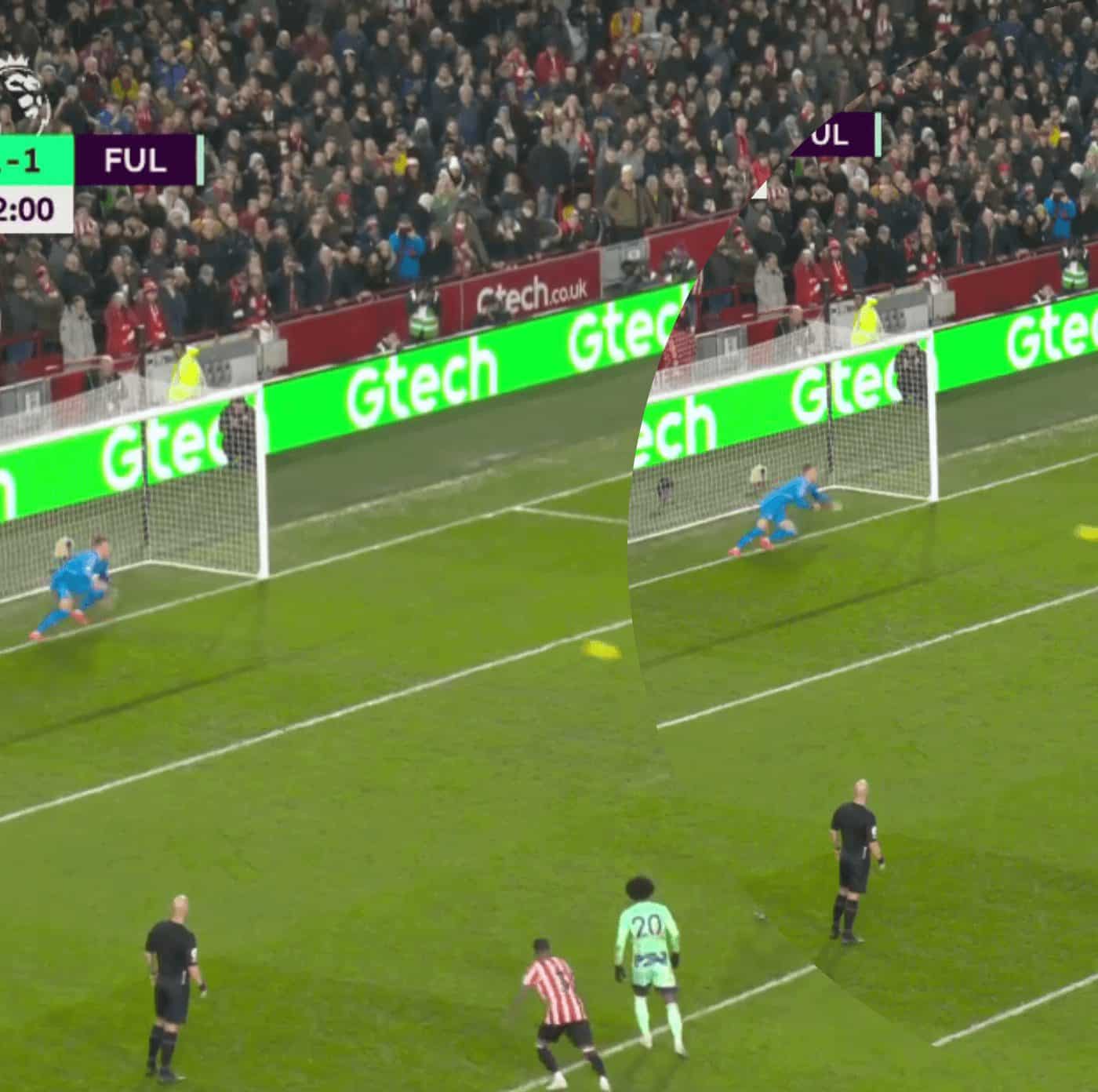

James Milner is an example of a player who maximises the probability of penalty success through varied run-ups, even though his ball-striking isn’t at the level of the greats in the game. Simply through accelerations during the run-up, Milner can create the space needed to the side of the goalkeepers to score penalties. His run-up is similar to Pogba in that it includes decelerations and accelerations, which means that goalkeepers cannot dive early. In the example below, we can see that Kepa is just about transferring his weight to his front leg to make the power step after the kick has been taken. By the time Kepa fully springs to the side, the ball will have already hit the back of the net. Although I am unable to pinpoint the moment at which Milner adopted this run-up method, he has achieved a 90% success rate from 21 penalties during his Liverpool career.

Flipping the method on its head, we now move on to decelerations during the run-up. When a player starts the run-up quickly but then slows down as they are about to reach the ball, the aim is usually to fool the goalkeeper into picking a side and diving early before reacting to their decision and putting it the other way.

As we can see in the example below, Jorginho is one of the original players to use this method, where he slows down just before he strikes the ball. His method is unique in the sense that he uses a hop to slow down rather than the conventional way, but that hop gives him the ability to keep his eyes on the goalie whilst knowing where the ball is due to the muscle memory of his hop, to know where the ball is by the time he lands and be able to strike it without looking at it.

He is yet another example of a player who doesn’t possess ball-striking skills, but through changes to the run-up, he has been able to achieve a career 84% penalty success rate, doing better than the average 76% of penalties that should be scored.

The deceleration provides players with the opportunity to bait the goalkeeper into diving early before putting the ball the other way. Lewandowski here can be seen looking up at the goalkeeper, seeing him shift his body weight to his left, so he puts the ball into the other half of the goal. Furthermore, the use of the stutter that Lewandowski uses encourages goalkeepers to the edge of their line ever so slightly, which means that even if a goalkeeper manages to dive the right way and save the penalty, it is likely that they have come off their line and the penalty will be retaken.

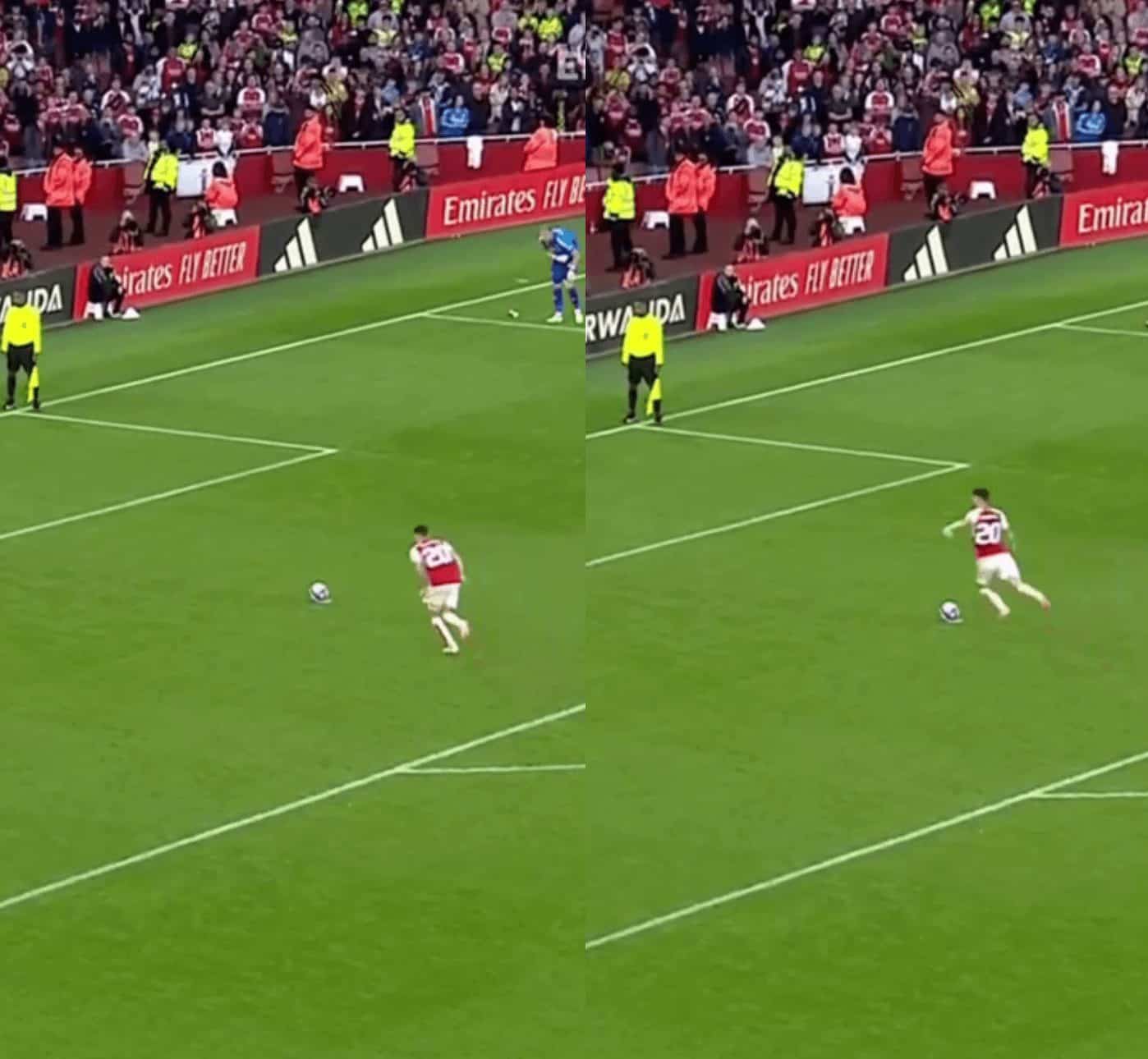

Sometimes, the goalkeeper will refuse to dive early, anticipating the attacker’s deceleration before the shot. However, in those instances, goalkeepers can often be rooted to the spot. Similar to the penalties where attackers accelerate, when goalkeepers wait for the shot, they don’t have the time to generate the spring to dive far through the power step. As shown in the image below, when Leno waits for the shot, he doesn’t have time to make the step.

As a result, all of Leno’s body weight is shifted to his far side leg whilst the ball is already on the screen, on the way to the goal. He doesn’t have time to take a step as the ball is already in motion, meaning that he has to attempt to dive without generating much momentum towards the ball, and his left leg is still in the middle of the goal.

Because of the absence of that vital power step towards the ball, Leno, at full stretch, still leaves a large portion of the goal open on the side he has dived on. We can see in the image that the ball has a lot of space between the keeper and the post to arrive in. The ball is already hitting the back of the net at this point, meaning that the space between Leno and the post is even wider at the point the ball crosses the line, which is all that matters.

Short Run-Ups

Penalties with short run-ups are similar in the sense that players can still speed up or move slowly as they approach the ball. However, the shorter distance gives players less time to manipulate the goalkeeper, and it is impossible to decelerate. Using my research, players who only took two steps before striking the ball managed to achieve a 90% success rate from penalties.

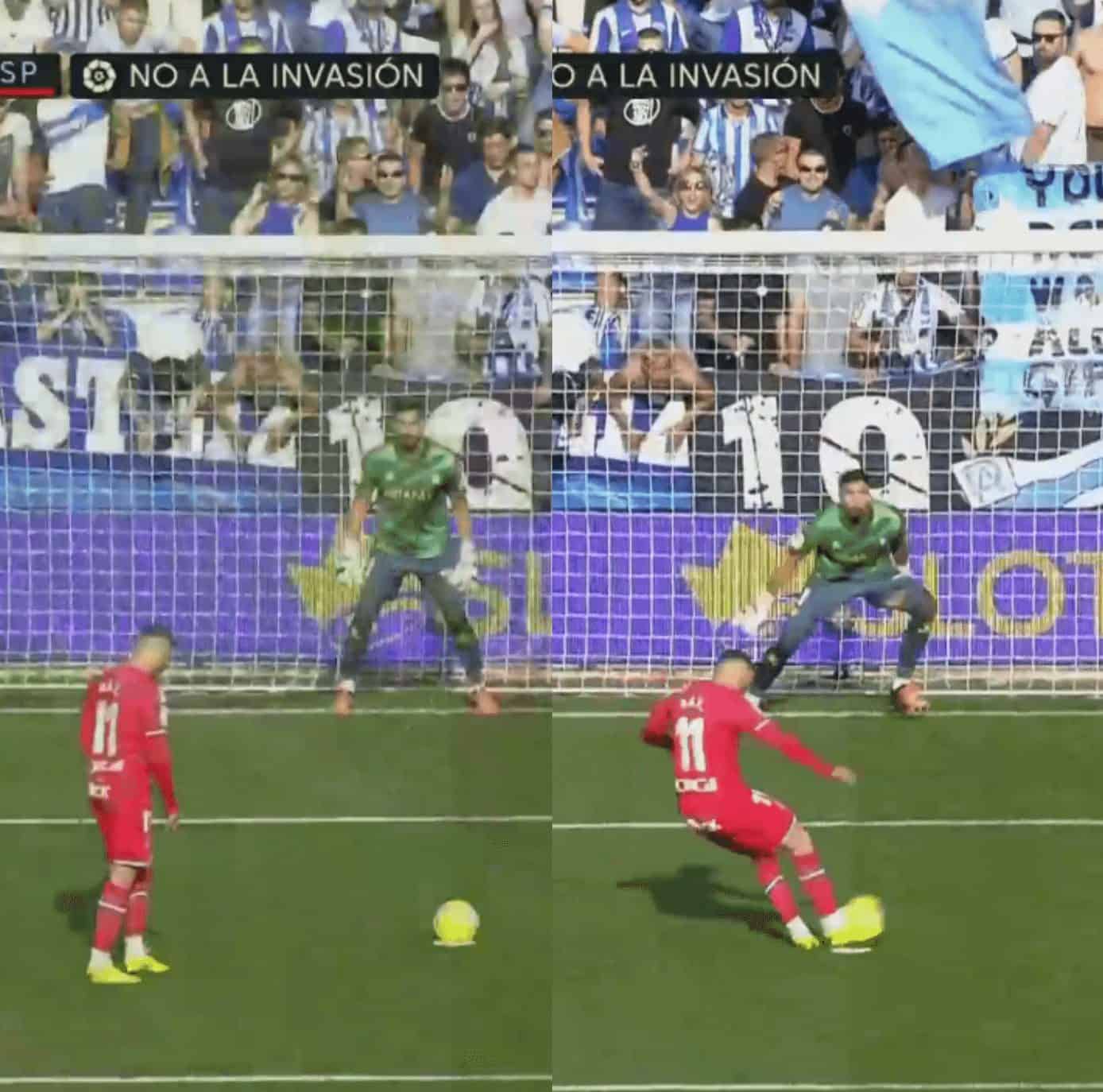

Raul de Tomas changes his run-up to be unpredictable, choosing between both short and long run-ups. However, in this particular example, his use of a short run-up is particularly effective. We can see that he starts off in a close position to the ball. It is also important to add that he waits for long periods of time after the referee blows his whistle, which means that goalkeepers are left standing on the spot, unsure at what moment the kick will be taken.

He also looks away from the goal, acting uninterested before making that burst towards the ball. At that moment, goalkeepers don’t have enough time to make the power step to make their dive.

Yet again, due to the unpredictability of the run-up, the goalkeeper’s weight is all on the back leg at the moment in which the ball is struck. Due to the short run-up and no real change of pace during the actual run-up, the goalkeeper isn’t fully deceived, but the power step is still made after the ball is struck, therefore meaning he cannot reach the wider areas of the goal.

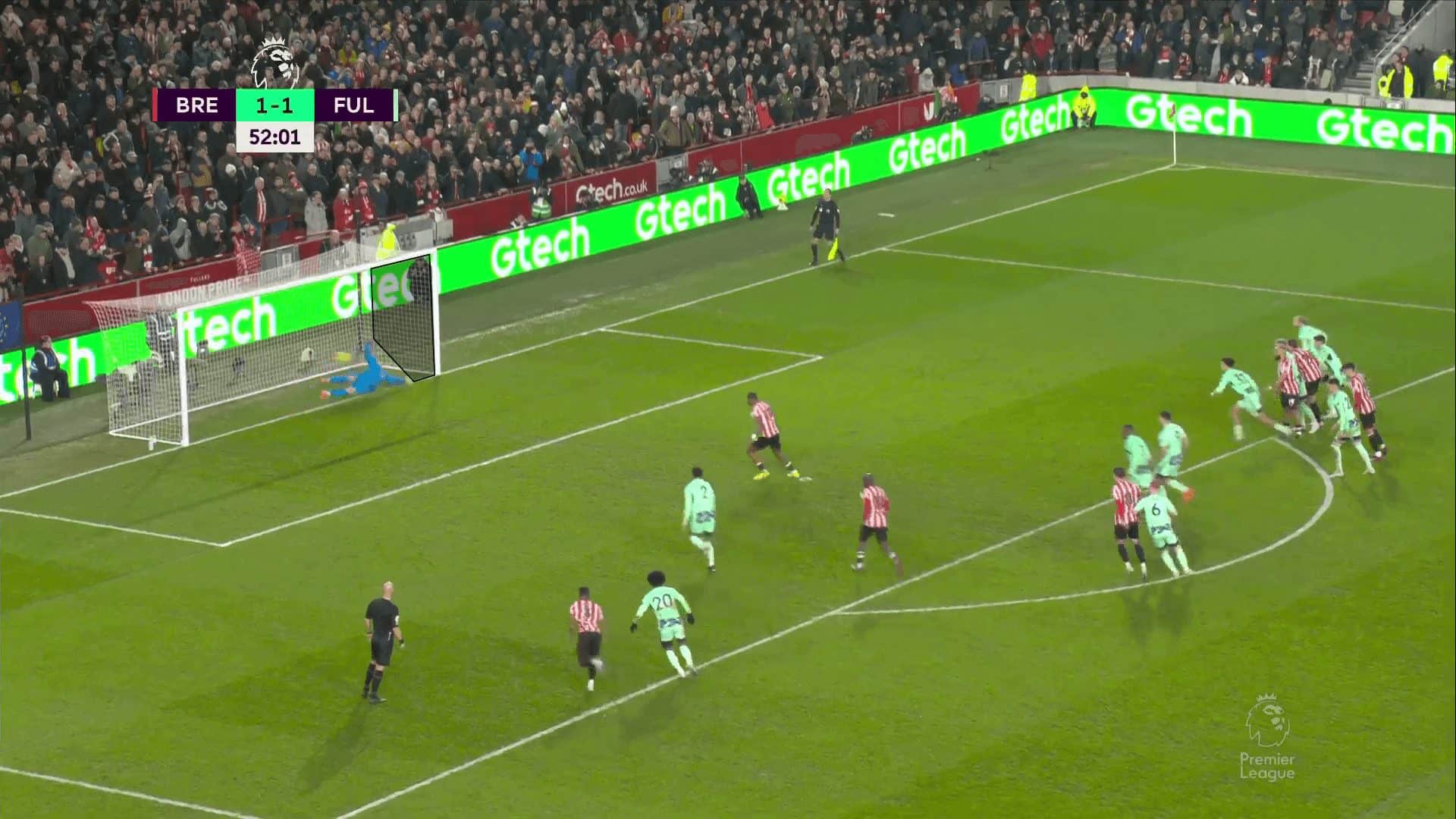

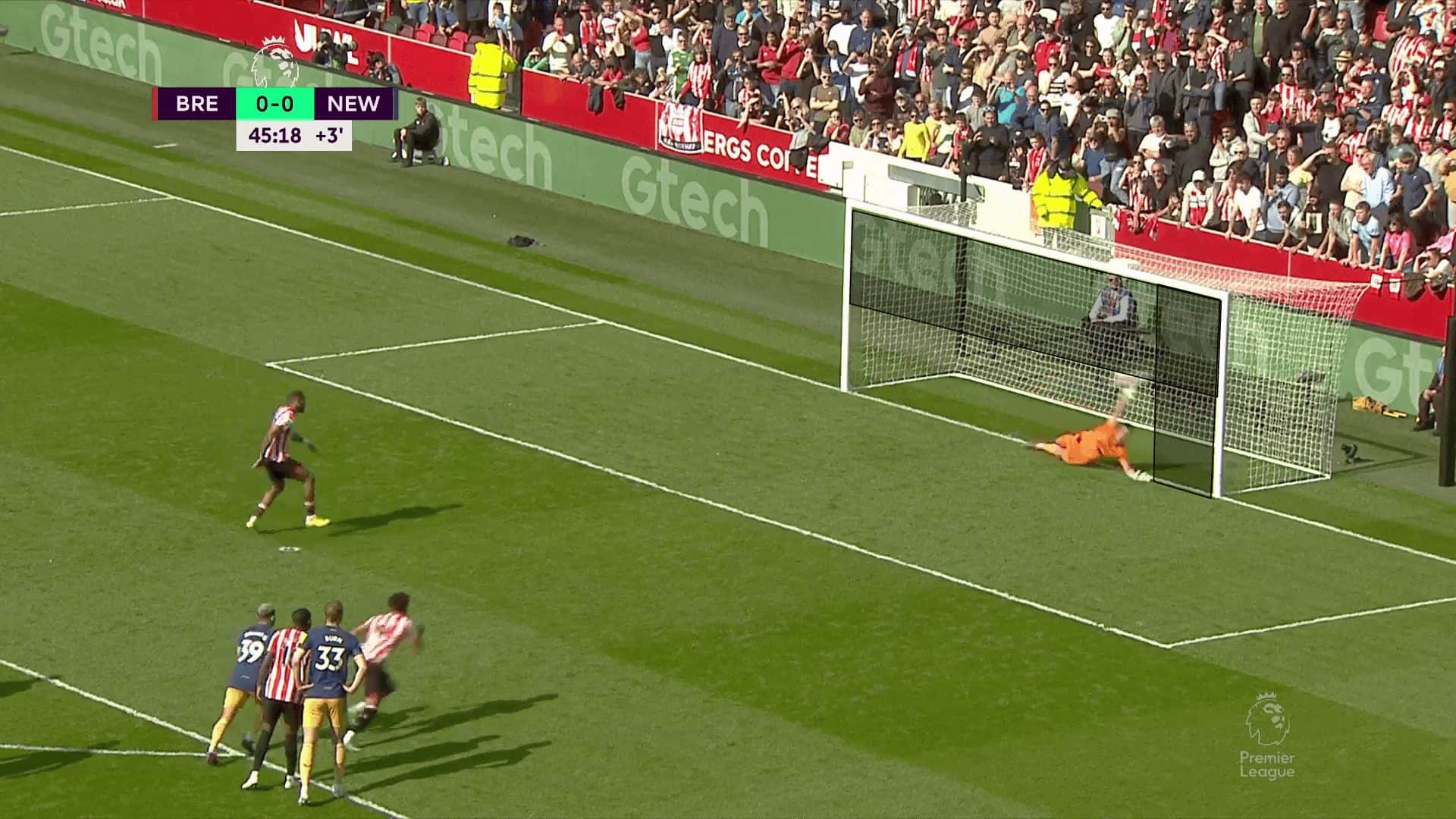

Ivan Toney is arguably one of the strongest penalty-takers in the world, with a 94% success rate from 32 penalties. He uses similar methods to the likes of Jorginho and Lewandowski, where he waits for the goalkeeper to move. Rather than decelerating, Toney walks slowly towards the ball, but then has the option to speed up when he sees a goalkeeper unwilling to move early. There are two main options, the first being that he waits for the goalkeeper to make the power step one way before putting the ball in the other side of the goal.

The other option is to slightly speed up and shoot when it is clear the goalkeeper is waiting for the shot and anticipating the slow walk. This can leave the goalkeeper rooted to the spot, similar to what Milner and Ronaldo have done. When the goalkeeper is rooted, they are unable to generate the spring to reach the wide areas of the goal, and Toney has the excellent ability to put the ball in the top half of the goal. We can see Nick Pope at full stretch after diving off of his back leg, which means that a large column of the wide right of the goal is left open.

Summary

This tactical analysis has detailed the different types of a run-up players can use when approaching penalty kicks and why this helps to increase the success rate of penalty kicks. Goalkeepers are often able to predict the time at which the ball will be kicked and dive early towards the side they picked, allowing them to cover the entire area that they wish to (e.g. bottom right). However, through the introduction of varied run-ups through changes to step length and speed, attackers are able to force goalkeepers to remain rooted to their line until it is physically too late for them to cover the widest parts of the goal, negating their power step. Even players who fail to possess strong ball-striking skills are able to create enough space for themselves to convert penalty kicks.

Comments