Before reading this article, go to your preferred search engine, type in ‘Monaco football news’ and check what’s returned to you. Aurélien Tchouaméni transfer speculation, amid fierce speculation surrounding the midfielder and the likes of Real Madrid and Liverpool? Tick. One or two bits focusing on Cesc Fàbregas’ future, with the Arsenal, Chelsea and Barcelona legend looking to potentially end his three-year stint in the principality? Possibly. Speculation over sporting director Paul Mitchell, with the Ralf Rangnick-approved recruitment expert, allegedly being watched by clubs such as Manchester United and Chelsea? Maybe.

This is completely understandable and not at all a knock on those pieces, I’ve no doubt enjoyed many of them. However, has football media moved too far in the direction of behind-the-scenes speculation and dialogue while moving away from discussions over on-the-pitch matters? If you’re in the circles that discuss on-the-pitch performance regularly, this probably doesn’t matter for you, as you’ll be able to find the content you like. In the wider domain of football discourse, however, we’re still very much operating in a gossipy world more so than one of substantial analysis and discussion, even with the likes of Sky Sports continuously introducing more and more data and modern analytics tools into their EPL coverage to provide the viewer with a more informed view on performances.

My point here is — you wouldn’t quickly discover the story of how Monaco secured third place, and UEFA Champions League football for next season — this past weekend, on the final day of the campaign, nor would you easily get informed that Les Monégasques ended the 2021/22 season as Ligue 1’s most in-form side, thanks to 10 wins, one draw and one loss in their final 12 games, giving them 31 points; that’s seven more points than title-winners PSG and second-placed Marseille (both of whom were joint-second on the end-of-season 12-game form table) accumulated in that same time.

So, if you’re someone who wants to peruse a tactical analysis piece looking into some of the strategies and tactics implemented by Philippe Clement to achieve such good results to end the campaign and get his team into Europe’s premier competition for next term, you’ve come to the right place. This tactical analysis aims to provide some in-depth analysis of Monaco’s performances during this impressive run of fixtures, not overly focusing on individuals, though of course, individual quality, ability to fulfil instructions and perform specific roles are of the utmost importance in any football team, rather this piece aims to focus primarily on Monaco as a team and how their Belgian coach and his football philosophy has led them together, as a group, to a dominant season’s end.

Build-up

We’re going to start this tactical analysis piece by looking at Monaco’s performances in possession, and where better to start than from the back, looking at Les Monégasques’ build-up play? Monaco sit fifth in Ligue 1’s overall possession table (52.3%) and third in Ligue 1’s overall passing table (452.55 per 90). It probably won’t come as a massive surprise that more often than not, they start their attacks via short passes from the goalkeeper to the centre-backs or full-backs — perhaps even a holding midfielder. Monaco place lots of importance on either creating space between the lines for their wingers, midfielders and forwards to invade and collect the ball from a deeper player’s pass before charging at the opposition’s backline, or creating space behind the opposition’s backline for their pacey forward line (usually featuring the likes of Wissam Ben Yedder, Gelson Martins and Kevin Volland, all of whom represent pacey forward options) to attack the open space. They can regularly create this space with great efficiency via their build-up play which often focuses on drawing the opposition’s press upfield as the deeper Monaco players circulate the ball between themselves while looking to forge an opening to cut through the opposition’s defensive shape.

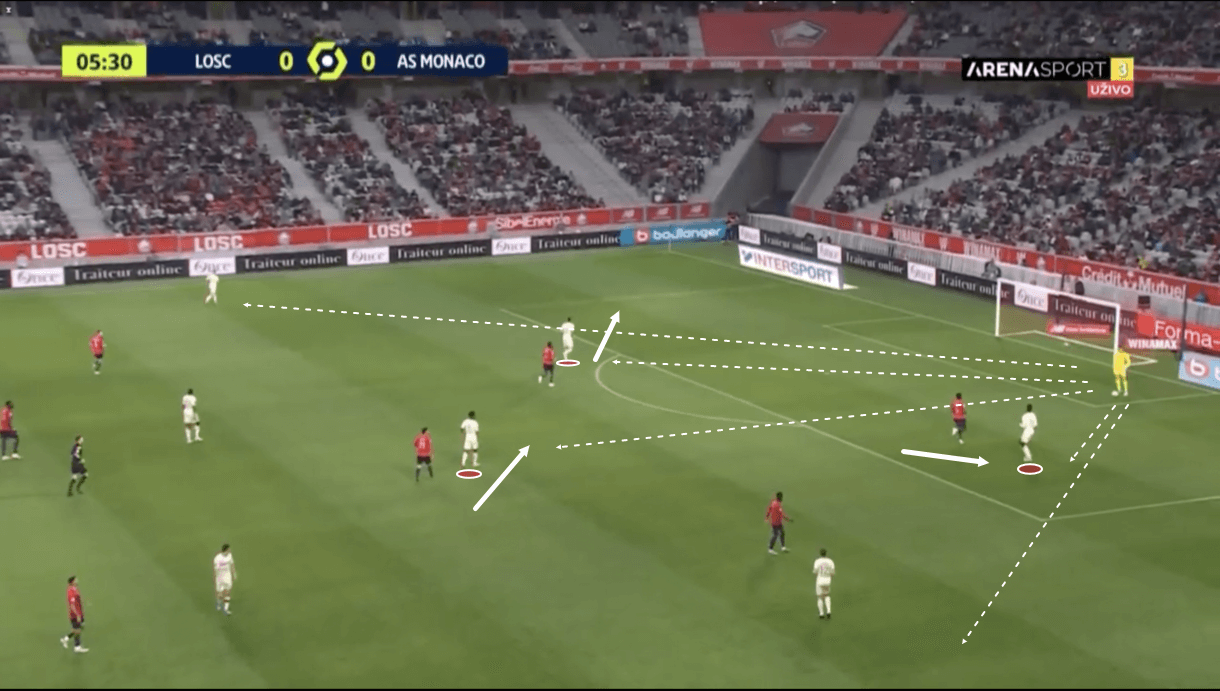

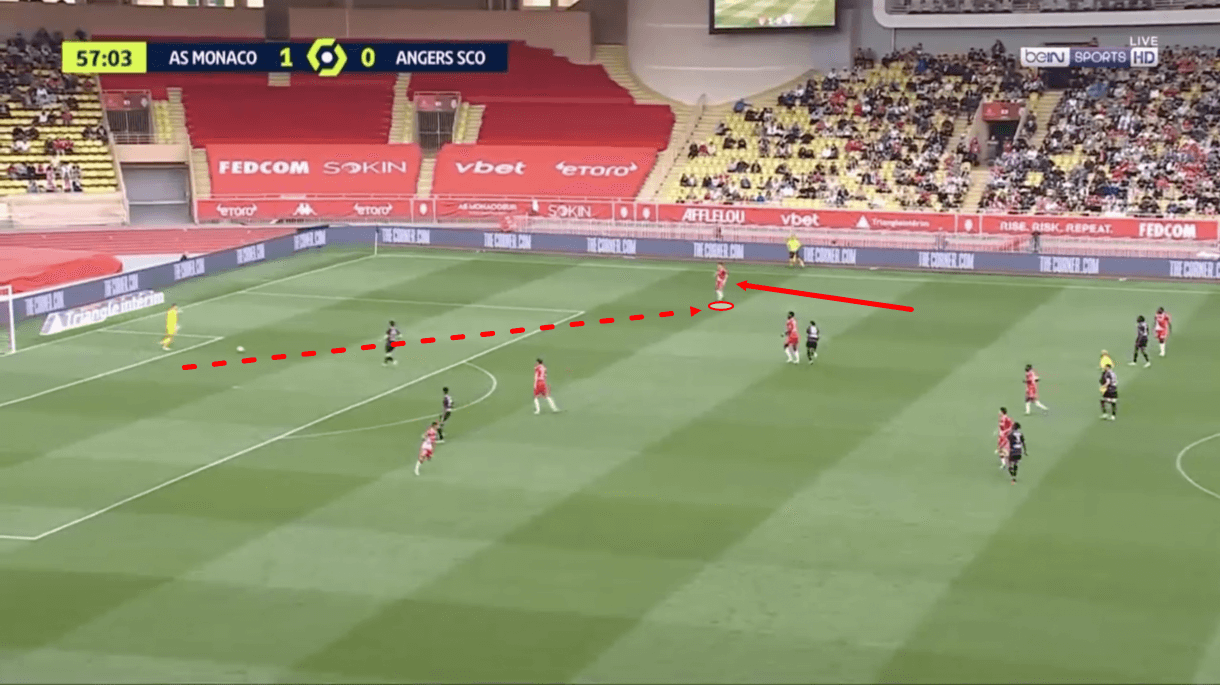

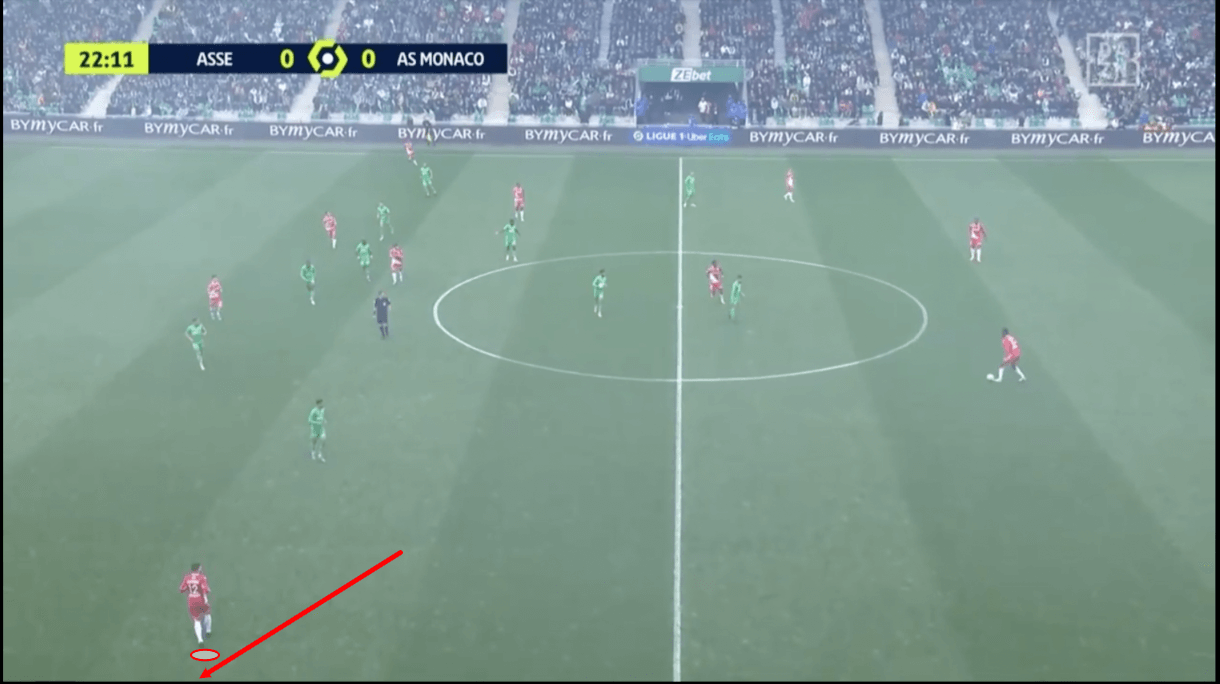

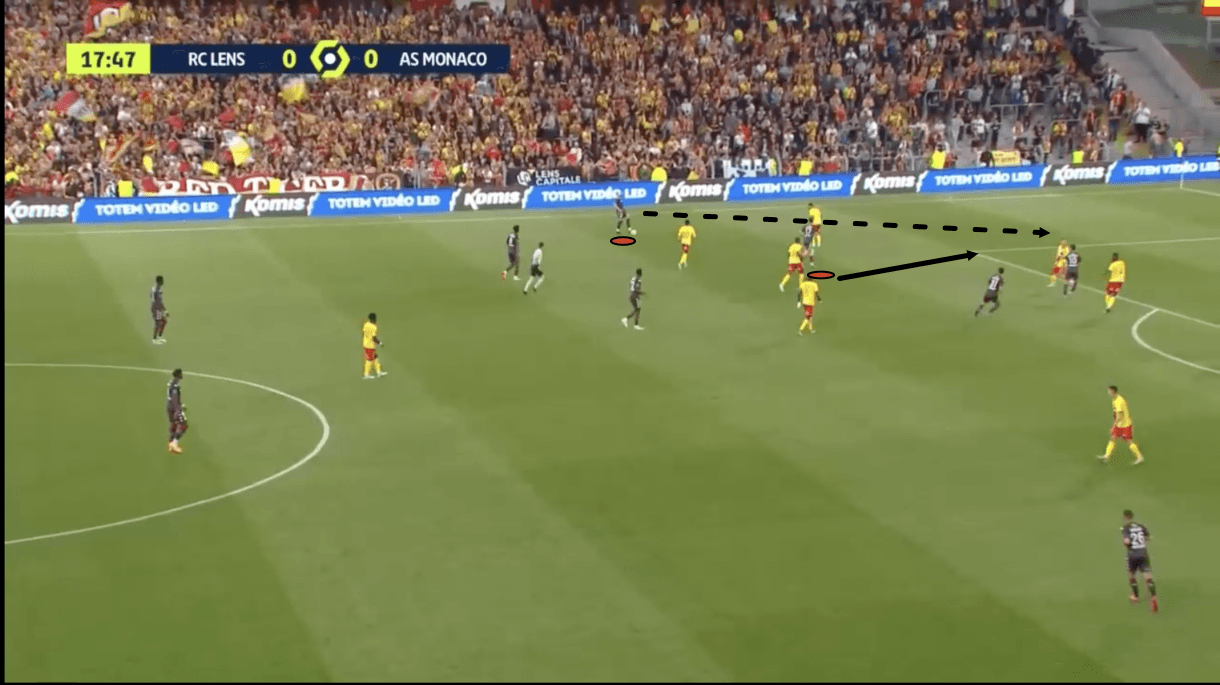

When starting their attack with the ‘keeper, Monaco look to create five secure passing options for him. We see an example of this in figure 1, where just before this image, the ball was sent back to the ‘keeper’s feet from one of the centre-backs, who then pushed wide, along with his central defensive partner, to open the central passing lane into midfield, where Tchouaméni moved from his left holding midfield position in Monaco’s typical 4-2-3-1 system to a more central and slightly deeper position than his midfield partner Youssouf Fofana. At the same time, Monaco’s full-backs advance to be in the same line as Tchouaméni at this moment, while Monaco’s wingers and ‘10’ will roam about ahead of Fofana between the lines, all likely operating on slightly different vertical and horizontal lines to make themselves more difficult for the opposition to mark and offer their deeper teammates different angles and passing options to each other.

Monaco need to be careful at times about playing too risky in deep positions as the centre-backs and holding midfielders can get caught in possession by being a little too casual, perhaps, at times. In general, though, their passing play to begin attacks is effective at drawing opposition bodies upfield and achieving their goal of creating more space for their more advanced players upfield.

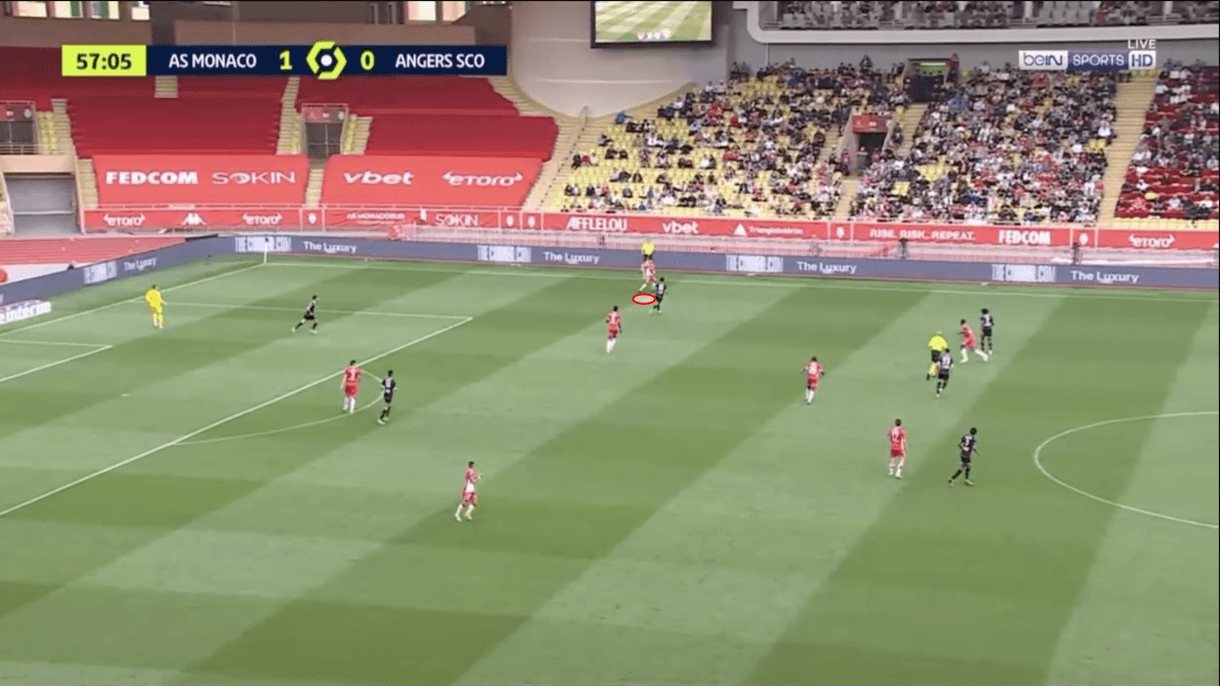

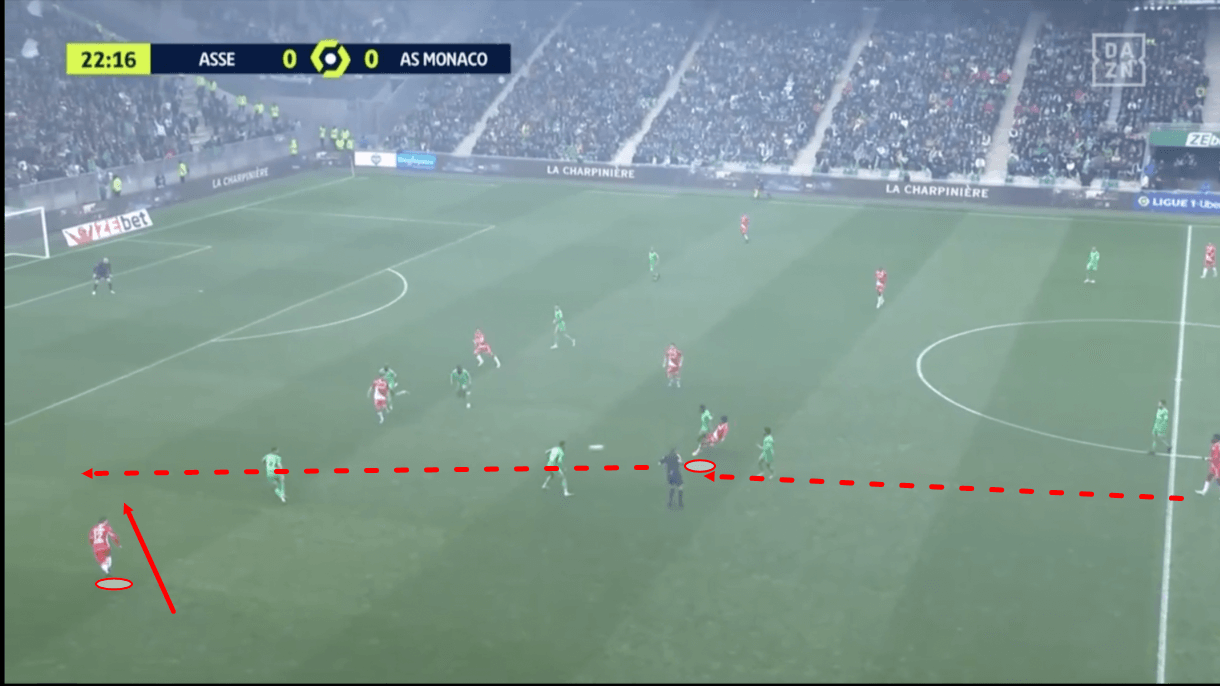

While we saw Tchouaméni dropping deep in the previous example, Clement doesn’t appear to have him under strict instructions to do so, as we’ve also seen his midfield partner Fofana operate as the deeper midfielder, allowing Tchouaméni freedom to go forward, at times this season, which we see an example of in figure 2. These two midfielders have a lot of footballing intelligence and probably don’t need to be dictated to in terms of where to go and when to do it, rather they seem to have been put in a system where they know the general goal and plan, but must then use their own heads to fulfil the manager’s wishes. When one goes, the other drops and vice versa. The important thing for these players, who are crucial in the build-up and ball progression for Monaco, is that 1. They offer their backline options behind the opposition’s first line of pressure and 2. They don’t stand on the same vertical or horizontal lines, ensuring they maintain a ‘stagger’ that makes them more difficult to control and gives both their teammates and each other more options and a chance to play through them.

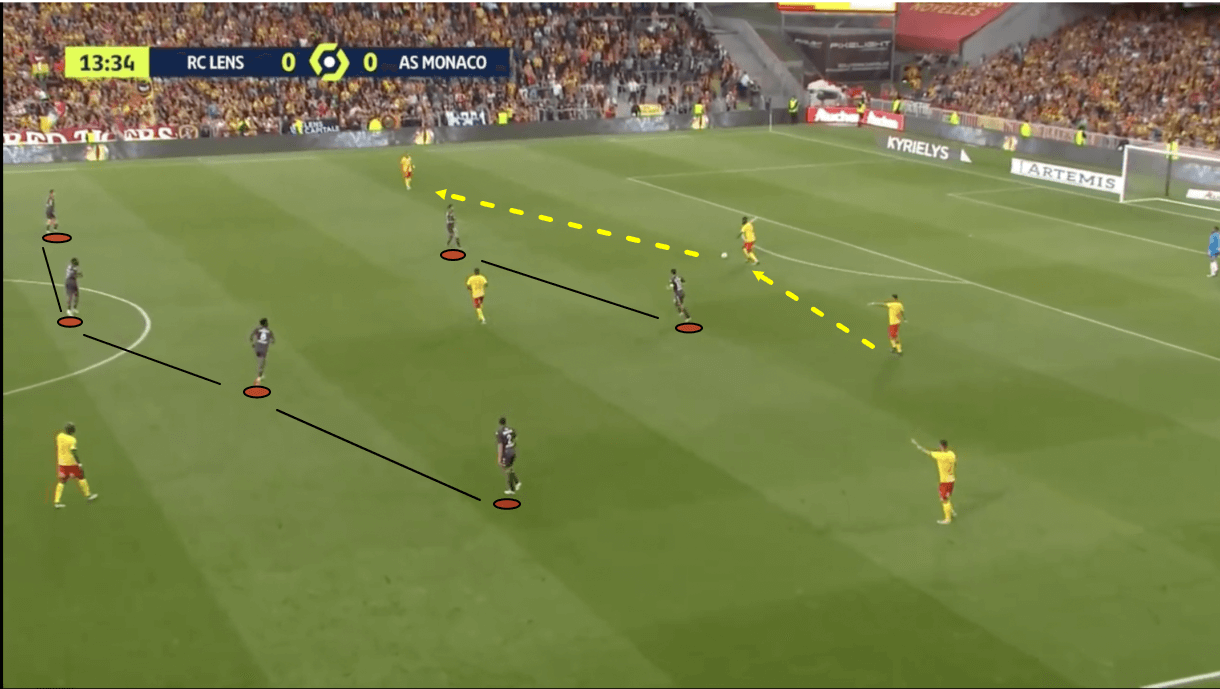

We do also see Monaco go long from the ‘keeper at times, and we see an example of how you might expect to see them set up in such situations in figure 3 (wingers, ‘10’ and centre-forward in the red-rimmed circles and midfielders/full-backs in the white-rimmed circles). Their ‘10’ and centre-forward often play very closely together and that remains true in figure 3, while the right-winger comes inside as well, combining positionally with the forwards and the midfield duo to create a strong core to win second-balls. The left-winger is positioned wider at this point, as he’s the target for the ‘keeper’s long ball. Whether it’s to target a specific player within the opposition’s system or just to vary up their way of attacking, Monaco aren’t extremely strict with who goes where exactly but this kind of setup where they’ve got a good central overload, keeping most of the forwards compact along with the midfield duo is a common sight when they opt to go long, to ensure that if the ball drops into the centre, they’ve got a good chance of winning the second ball, especially with the energy and power in midfield provided by Fofana and the interception-monster, Tchouaméni.

Progression

Moving on into the next step in attack, ball progression phase, again, the midfield pairing is really important here with their movement in the build-up phase designed to free them up to receive behind the opposition’s press, turn and get the team continuing forward as they move into the middle third of the pitch. Both Tchouaméni (8.3 per 90) and Fofana (7.38 per 90) rank very highly among Ligue 1 midfielders when it comes to progressive passes; this is indicative of the duo’s role in Monaco’s progression moving forward from situations where we saw them in the previous section to the next phase. Their job is facilitated by their teammates’ positioning and movement, as they ensure the midfielders have plenty of potential options all standing at varying points to one another to try to create at least one free man for the midfielders to target.

It’s also common to see Fofana and Tchouaméni, respectively, look to drive forward with the ball from deep. So, if they’ve managed to receive and turn but then their forward passing options are limited, they also retain the freedom to just carry the ball forward themselves, knowing that the other midfielder has the intelligence and maturity in their game to cover for them. This level of understanding and mutual respect makes the pair a really effective midfield duo, which ultimately comes to the benefit of Monaco’s ball progression.

It’s not just Monaco’s midfielders who retain the licence to drive forward; the same rule applies to the centre-backs in the same situation. If they deem no passing option more suitable than the option of just carrying the ball through the opposition’s press, then they are free to do so, again, knowing that the ball-near midfielder will rotate into the centre-back position to cover for them, as we see Fofana doing in figure 4. Again, this is an example of the kind of intelligent, mature play we’ve become used to from Monaco’s star men.

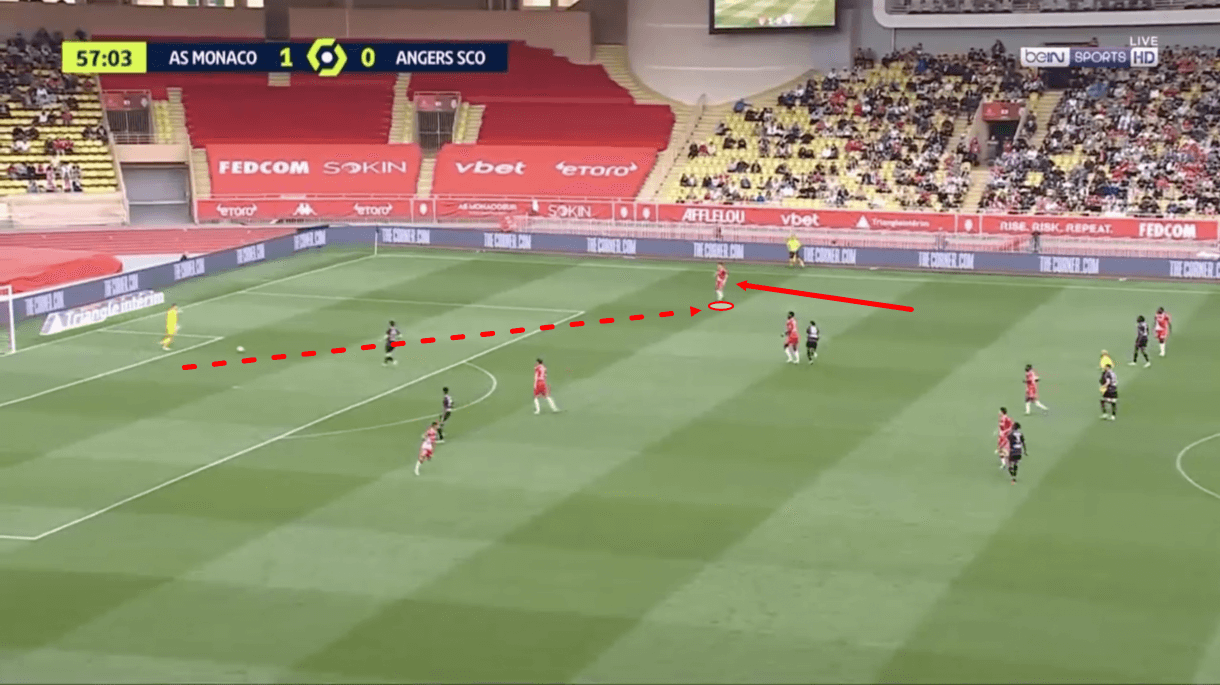

Of course, opposing teams are aware of these midfielders’ importance to Monaco as a team and Clement’s system. They haven’t had their heads in the sand and do happen to play in the same league as Les Monégasques, after all. As a result, they often do their very best to prevent the ball from going into midfield from the back, whether that’s by employing a tight man-oriented scheme on the two players or by caging them in a pressing system to block the passing lanes into the midfielders, perhaps while closing down the ball carrier. We see ane example of the former in figure 5, with Monaco’s midfielders all carrying some extra weight in the form of an Angers player on their back in this example.

Monaco’s major solution to getting around this in 2021/22 has been: to use the full-backs. Heavily. The full-backs have been the key, secret ingredient to Monaco’s ball progression this term, as when roads into midfield are blocked off, these guys routinely come in clutch, dropping deeper, as we see from the left-back in figure 5 (compared to where we saw them sitting in, for instance, figure 1) to make themselves more easily accessible for the ‘keeper/centre-backs.

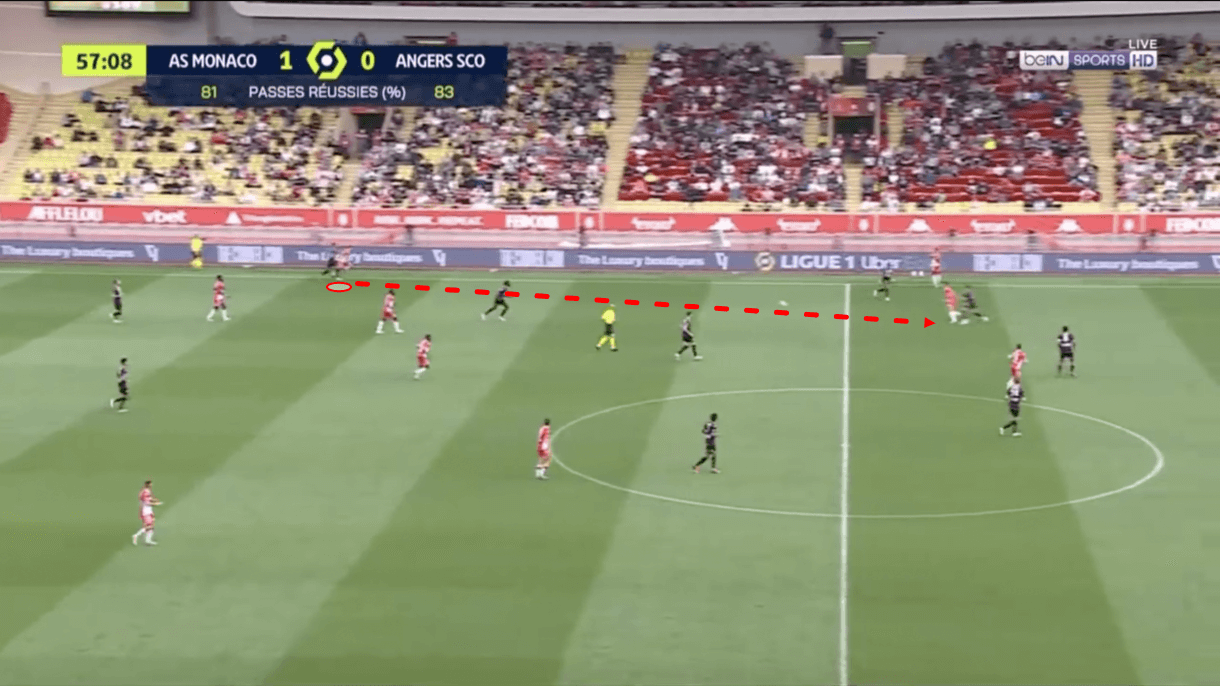

Clement’s full-backs can often do this without attracting too much pressure, with the opposition’s main focus usually being to protect the centre, especially from Fofana and Tchouaméni, or on wingers further upfield, Monaco’s ‘10’, etc. The full-backs can often be an afterthought, which plays well into Les Monégasques’ hands. As we move on into figure 6, we see how left-back Caio Henrique was able to receive the ball and turn to face the way he wanted to play before an opposition body was in close proximity.

This gave the full-back enough time to set himself, get his head up, pick out a teammate and send the ball his way, which we see as this passage of play culminates in the ball getting played into one of the forwards’ feet in figure 7. From here, the receiver can either look to carry the ball at the backline himself, combine with one of his fellow attackers or even send the ball short into the feet of one of Monaco’s midfielders, who we see, now have a lot more freedom. All of this highlights how beneficial progressing through the full-back and bypassing the midfield line altogether can be for Monaco, as if they really want to, they can then move back into midfield and get the ball with these players via the scenic route or just continue the attack without going through them, both of which are good options here.

This important role in Monaco’s tactics has led to their full-backs (Djibril Sidibé – 12.81 per 90, Ruben Aguilar – 11.86 per 90, Ismail Jakobs – 11.35 per 90 and Caio Henrique – 9.97 per 90) all ranking extremely highly (Sidibé – 1st, Aguilar – 3rd, Jakobs – 4th and Henrique – 9th) for progressive passes when compared with all of Ligue 1’s full-backs to have played at least 800 minutes this term, highlighting how important this progressive role is for the full-backs within Monaco’s tactics.

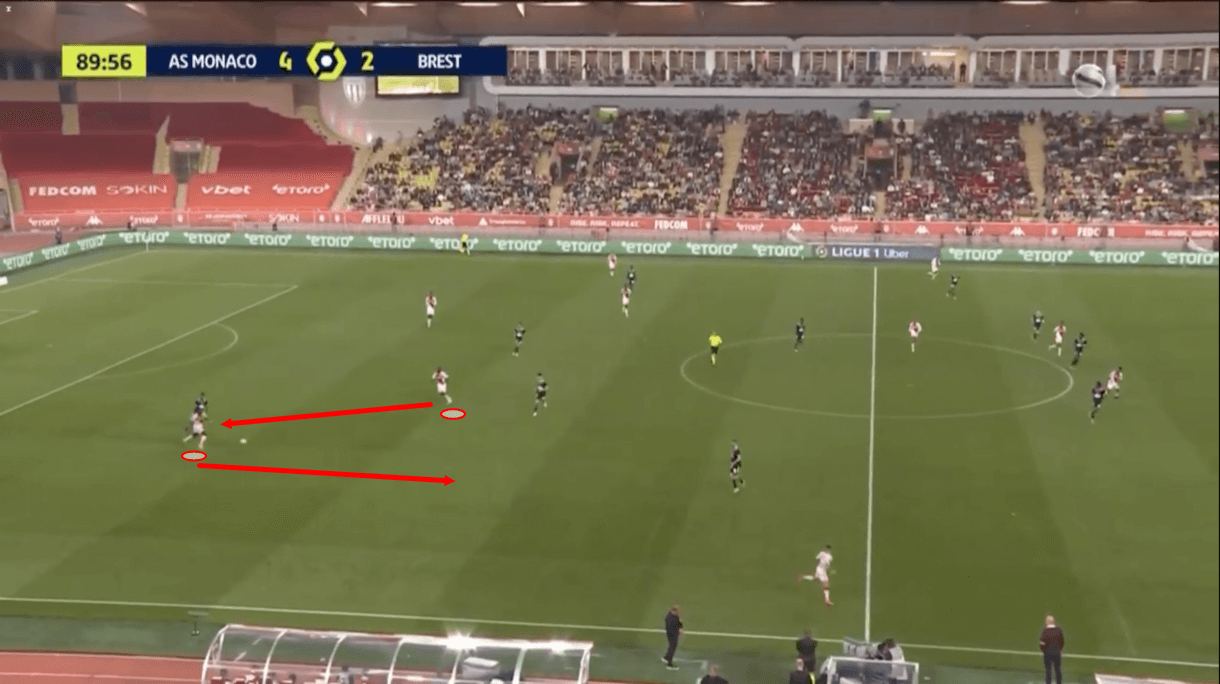

However, there’s one more key role for Monaco’s full-backs as the team enters the middle third of the pitch as well, and that is: holding the width. Now, Clement doesn’t need to have both full-backs on the sidelines at all times but he does require the ball-near full-back to be at the touchline and the ball-far full-back to at least be the widest player on that side of the pitch — though he’s happy for this player to come narrower, which could be helpful should the ball get turned over or if Monaco need bodies centrally.

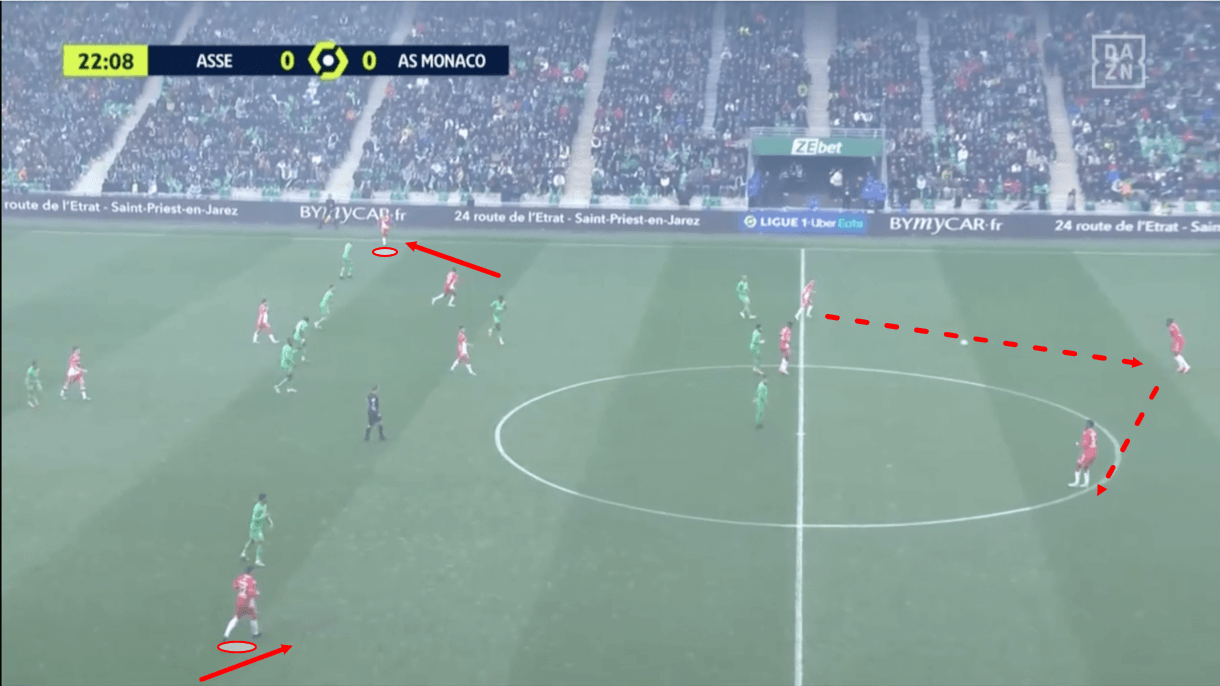

We see an example of Monaco’s right-back sitting as widely as possible in figure 8, while the left-back is more central. At this moment, though, we see Les Monégasques moving the ball across the pitch via the centre-backs and as they do so, moving on into figure 9, we see how their shape and positioning changes.

As soon as the ball enters the left centre-back’s feet, the left-back has sprung out to the sideline where he can offer the left centre-back a wide passing option in tonnes of space. However, there’s more to it than just that, as we can see that the left back’s movement has also begun drawing an opposition body (with Saint-Étienne playing a 5-3-2 here) out to cover this potential pass. By drawing a player out from the centre like this, Monaco’s left-back has created more space centrally for Monaco’s midfielders to attack and ultimately, as we’ll see when moving on into figure 10, receive the next pass. This is what you’d call ‘stretching’ the opposition. By positioning oneself wide, you can draw a defensive player out of shape and in doing so, can create more space for teammates to enjoy centrally.

In figure 10, we see how the left-back continued his run after the midfielder received the ball in midfield from the centre-back. With the midfielder attracting attention back to him, away from the full-back, after receiving, the full-back now enjoys more space and as he begins moving inside while targeting space behind the opposition’s backline, the midfielder gets his head up, spots the run and threads a delightful through ball between the opposition’s defensive shape and into the runner’s path — setting him up to attack the final third and put Monaco into a good goalscoring position.

Chance creation

The full-backs remain key to Monaco’s attack inside the final third, as they continue providing the width, which Les Monégasques like to use a lot. This is a big reason why Monaco have made the second-most crosses (15 per 90) of any side in France’s top flight in 2021/22. Plenty of Monaco’s crosses come from the full-backs themselves, with left-back Jakobs (5.71 per 90) making the most of any Ligue 1 full-back this term. Monaco’s wingers are also heavily involved as crossers, though, albeit from a more central position.

So, how do Monaco set up these crossing opportunities and get their playmakers into so much space inside the final third? Firstly, let’s turn our attention to figure 11, where we see Monaco on the verge of entering the final third. However, it’s not just entering the final third that counts, you need to do it well to ensure it doesn’t end in vain and a goalscoring opportunity can be created. Les Monégasques manage to create a great opportunity to enter the final third on this occasion thanks to some brilliant off-the-ball movement. With the ball carrier here getting his head up and looking at the options ahead of him, one of Monaco’s forwards, circled, makes his desire to receive the ball visible and begins running diagonally towards the centre. The animated attacker quickly attracts attention from the opposition right-back outside of him, which leads to that player moving more centrally to pick him up before the ball can be slid into his path.

However, if you briefly return to figure 11, you’ll see that a wider player was creeping up behind from deep to attack this space as the opposition full-back left to pick up the forward moving centrally. Moving on into figure 12, then, we see that the Monaco wide man ended up in possession of the ball in space inside the final third, wide on the left-wing; this shows how important intelligent off-the-ball movement and spatial awareness, particularly with regard to teammates’ positioning, are for Monaco when entering the final third.

From here, the ball carrier has a few options: he can run at the full-back, cross early (the option he ends up taking) or slide a through ball towards the byline and into the path of the forward he combined with who could now target space behind that defender. All of these are attractive options in some way that could hurt the opposition.

While that previous passage of play didn’t see the full-back sliding the ball into the wide attacker’s path, we do see that occur in figure 13. Again, we see the full-back in possession out wide here, with plenty of space to enjoy. This looks very similar to the previous example, with Monaco having doubled up on the opposition full-back out wide. The full-back remains caught between a rock and a hard place here as the full-back enjoys the same three attractive options he did in the previous example too. As play moves on from this, we see the full-back slide a through ball into the attacker’s running path behind the defender, creating a decent cutback crossing opportunity for Les Monégasques.

So, Monaco can vary their attacks and final third entries quite a lot but some patterns are clear — they like to use width a lot, they cross a lot, off-the-ball movement to manipulate the opposition is paramount, and they create lots of 2v1s out wide versus the opposition’s full-back and they’re comfortable both crossing early, from a wider and deeper position and later, from a more advanced and central position, though different players are typically responsible for those different types of crosses.

Defending high

Monaco ended the 2021/22 campaign with the third-lowest PPDA in France’s top-flight (9.84), along with having engaged in the third-most defensive duels (68.46 per 90). This is indicative of their aggressive and proactive defensive style, designed to win the ball back high and close to the opposition’s goal when possible. In doing so, they can create excellent opportunities to hit the opposition quickly while in transition — always a highly-valuable goalscoring opportunity.

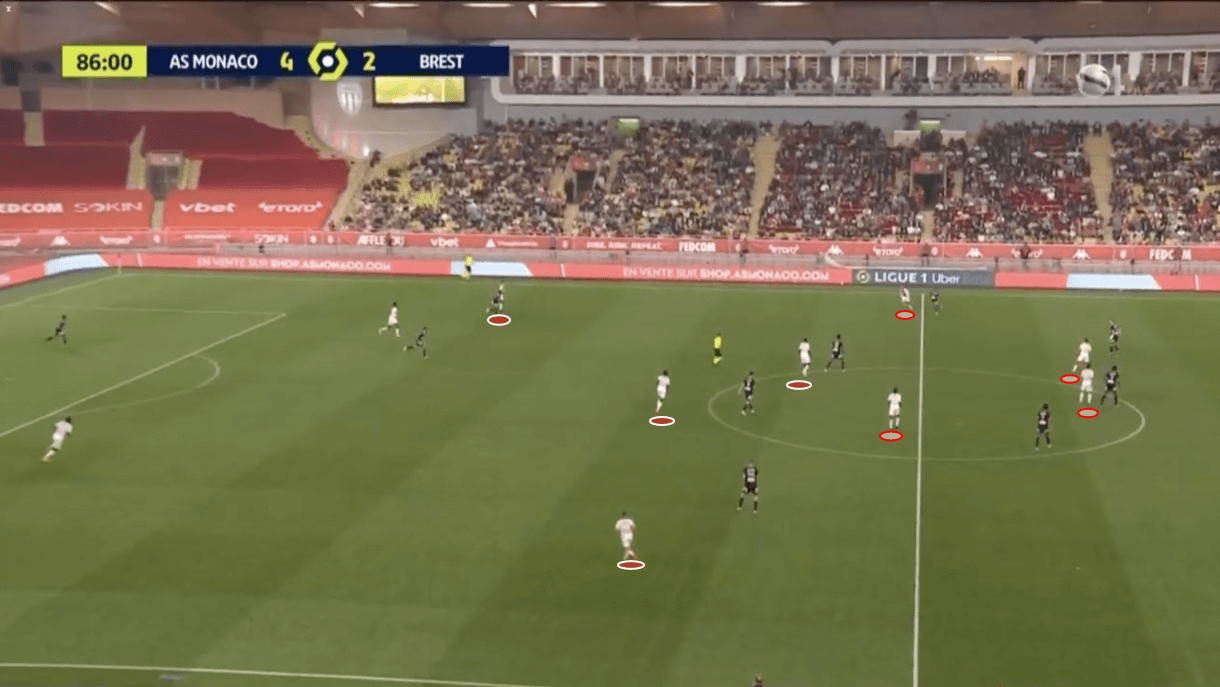

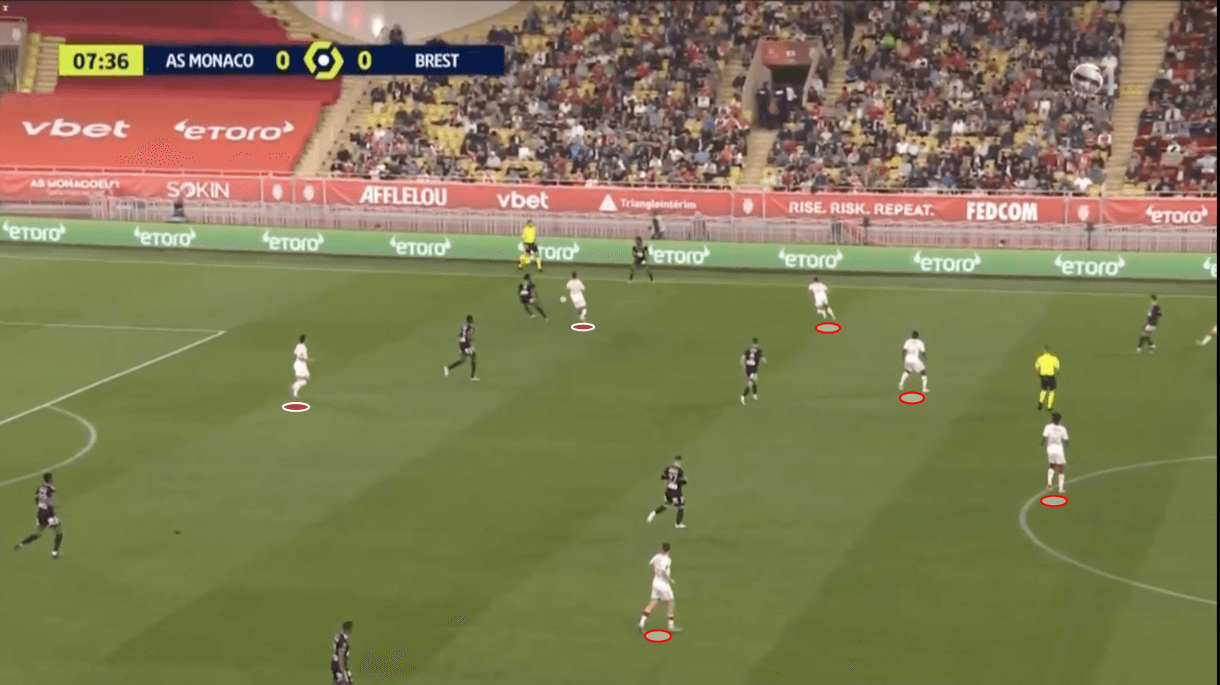

At the start of their attacks, Monaco defend in a 4-4-2, with the ‘10’ joining the centre-forward in the first line of defence and the wingers dropping to be on the same line as the midfielders. At first glance, the shape appears to be quite position-oriented in figure 14, and this is largely the case although once an opposition player does enter their zone, players will deviate slightly from their base position to close the space on them a tad. However, they don’t jump at the first sign of someone moving toward them and generally remain focused on holding their positions and maintaining a manageable distance between each other to ensure the opposition can’t play through them.

Responsibility for controlling the opposition’s deepest midfielder generally falls to the centre-forwards. With the ball centrally, as we see here, neither man gets too tight on the midfielder but both retain a close enough distance that if the ball is played to him, they can quickly close him down and regain possession. This also makes a heavy touch or mis-control or even taking too much time to make a decision on his next move extremely dangerous for the holding midfielder. In a sense, Monaco back themselves to force a turnover should it be played to the isolated midfielder in this kind of situation. However, when the ball is played out to either side from the centre, then the responsibility falls to the forwards to cut the passing lane into midfield and prevent the midfielder from receiving while closing down the opposition ball carrier. As the ball-near forward closes down the opposition ball carrier, keeping the deepest midfielder in his cover shadow, the ball-far forward will also shift over, getting tighter to that midfielder from behind and ensuring an opportunity to, for argument’s sake, go from the left-back to the left centre-back and into the holding midfielder behind the pressing forward, doesn’t open up.

Additionally, as the ball moves from side to side, we see Monaco’s midfield line and backline shift about as well. In figure 15, the ball has been played to the opposition’s right centre-back and while the ball-near forward closes him down, operating in the fashion we discussed previously along with his centre-forward partner at this moment, Monaco’s midfield shifts to this side of the pitch alongside them, with the ball-near winger getting higher and marking the near passing option more aggressively, while the rest of the midfield line shifts over to cover the space behind him and the space left in the centre. When the ball is on this side of the pitch, Monaco still try to retain access to the opposite side, hence why we see the ball-far winger positioned where he is — centrally but still within sprinting distance of the opposition’s ball-far full-back should the switch be played. As a result, responsibility for controlling both the centre (at least the right central midfield area) and the option on the far wing falls to this player.

Brest didn’t opt for the quick switch here, instead, moving the ball across to the left-wing more slowly via the backline. As they reach the left-wing here in figure 16, we see how Monaco’s shape basically acts like a mirror of what we saw in figure 15. The ideas and instructions remain the same but with those on the opposite side carrying them out compared with what we saw in figure 15. This provides a good example of how Monaco’s system operates in the early defensive stages and note how the ball-near forward and winger continue to press aggressively, similarly to those in figure 15, while those behind them retain a manageable distance and decent levels of compactness.

Not to say space couldn’t open up between Monaco’s players here but they limit the amount that can, and this, combined with the elite levels of energy, pace, aggression, spatial awareness and anticipation in Monaco’s midfield, particularly the midfield duo, don’t expect a player receiving between the lines in space to enjoy such space for very long. We say ‘, particularly the midfield duo’ but take nothing away from the work rate on display this season from all of Monaco’s midfielders, full-backs and forwards in terms of defensive effort. It’s common to see the ‘10’ tracking back aggressively if they can win the ball in the mid-block phase, allowing the deeper midfielders to remain disciplined and compact knowing reinforcements are on their way. Teamwork is paramount. The midfielders in such a situation count on the ‘10’ to track back quickly and aggressively while the ‘10’ relies on the midfielders to maintain intelligent positioning and remain disciplined and calm to ensure space doesn’t open for the opposition ball carrier to exploit before he has time to arrive and engage the player in a defensive duel. This is just one example of this defensive teamwork and work rate in Monaco’s system this term, we’ve seen tonnes of similar examples throughout the season. The impressive levels of team spirit and togetherness, along with technical organisation, were key for propelling Monaco into the hotly-contested Champions League places.

Defending deep and transitioning to attack

Our final section of analysis focuses on Monaco when they move into a deeper block and how this combines with their transition to attack, which is another element of their game that has been very important this term. Monaco drop into a 4-4-1-1 shape when in the deep-block phase, leaving one attacker — usually, Ben Yedder — upfield as an attacking outlet should the ball be won back. Again, Monaco’s midfielders and full-backs are key in this phase of play as their respective ability to read the game, organisation instilled by Clement, overall aggression and energy are key in forcing turnovers and creating opportunities to counter-attack.

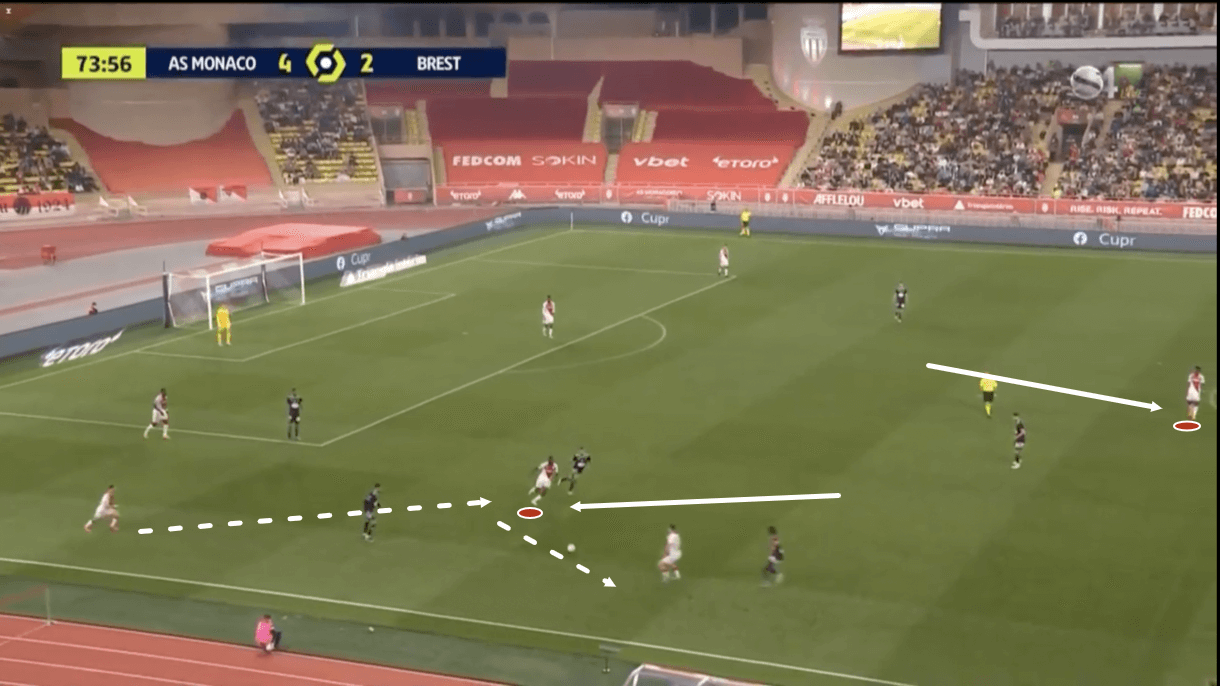

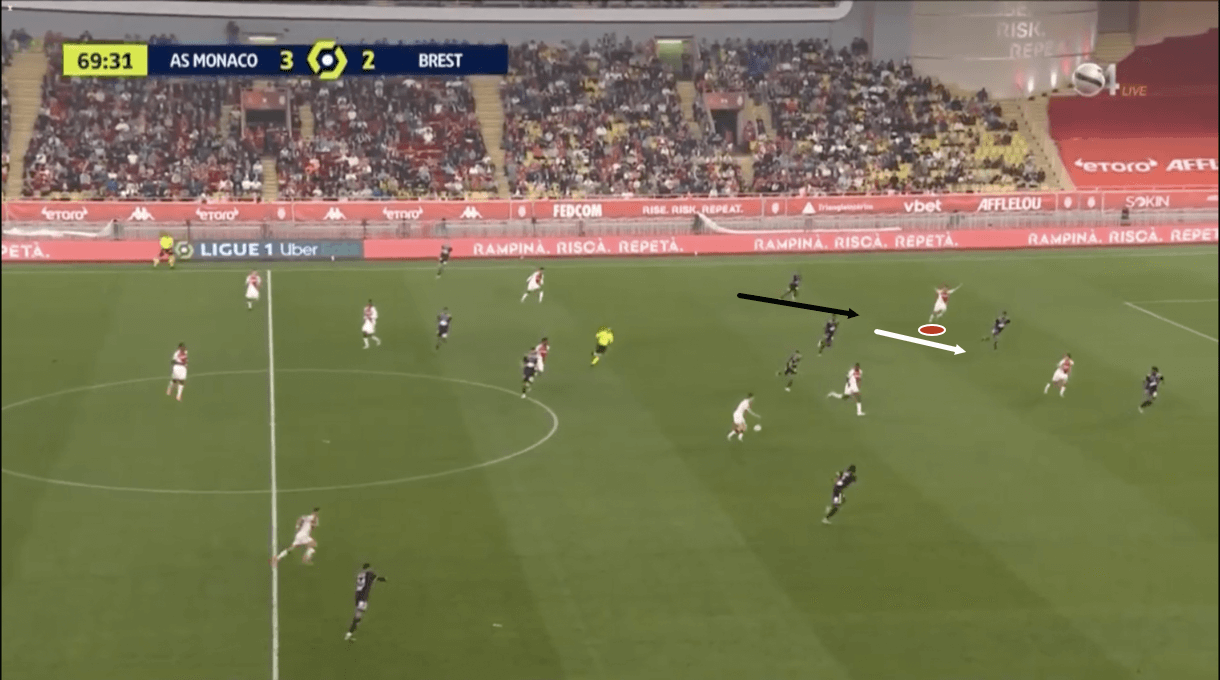

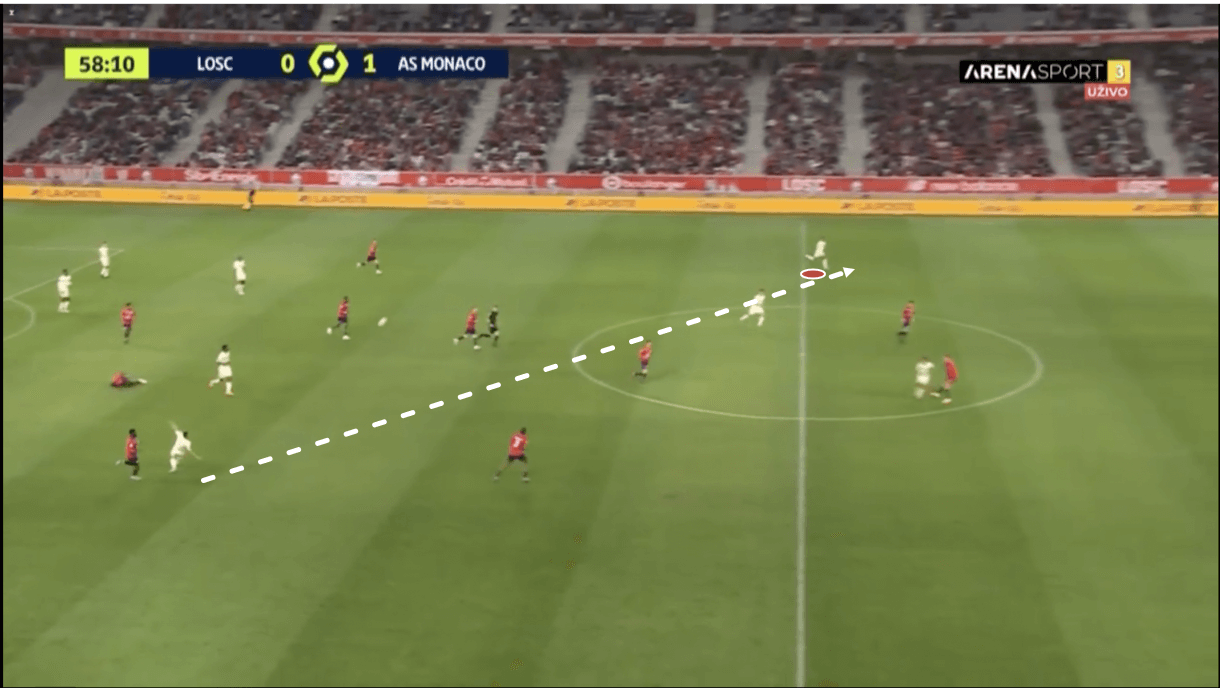

We see an example of Monaco’s winger forcing a turnover in figure 17. As the opposition attacker tried to move centrally and play a pass, Monaco’s full-back aggressively closed him down and sent the ball flying into his midfield teammate’s path. This player could then get on the ball, send it out towards a wider teammate in space on the right and get Monaco moving upfield.

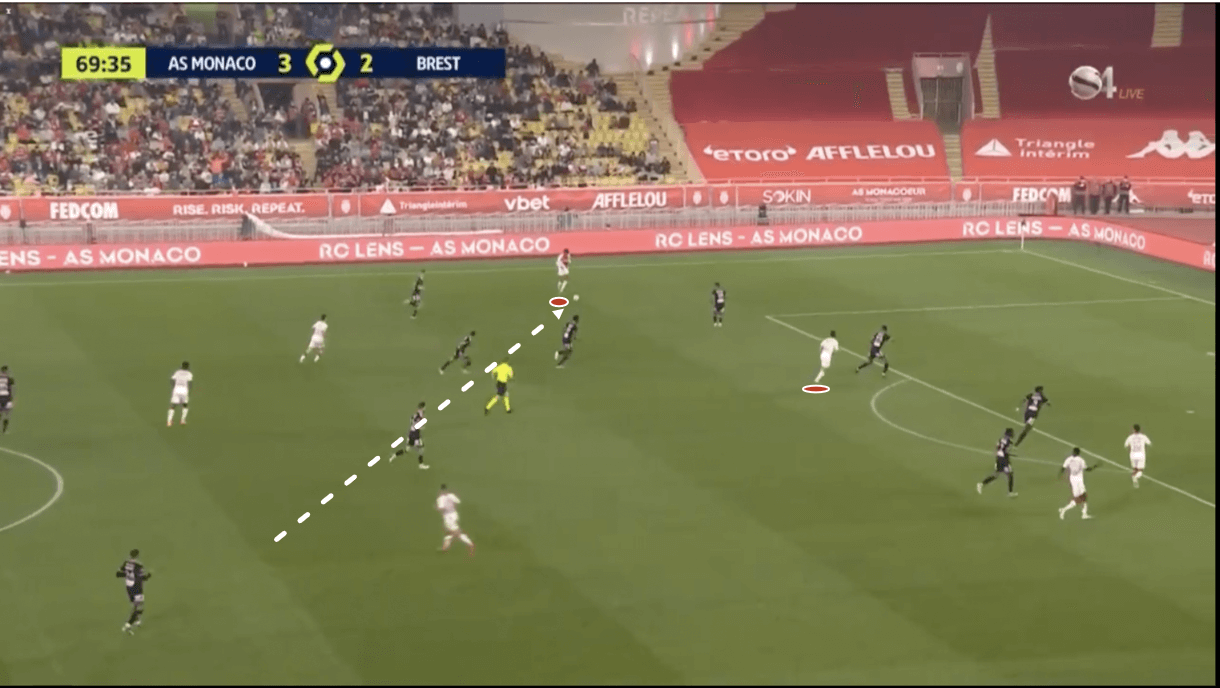

While technical defensive quality and energy are important in this phase and in creating opportunities for transition to attack — and absolutely should be recognised — that’s only part of the job. Monaco need to continue to be aggressive and proactive as they transition to attack and we see an excellent example of that in this passage of play, as we progress into figure 18. The energy levels that Monaco showed this season to get upfield quickly and really capitalise on counterattack opportunities were key for their success in transition.

As this passage of play moves on into figure 18, we see how the very same player who made the interception to turn the ball over and begin this counterattack for Monaco has now got up the other end of the pitch and quickly created a 3v2 overload for Monaco versus the opposition’s defensive line. This is pure energy and work rate — something that every player and every team needs and can make the difference between winning and losing as much as anything else. We saw plenty of that on display from Monaco this term. Yes, there’s a lot at play here. In the first example, we saw Monaco in a very well-organised 4-4-1-1 block with the winger getting the opportunity to steal the ball back for his side thanks to the engagement that this shape helped create but to get the opportunity and then take advantage of the opportunity, energy and effort play just as key a role as anything else in progressing the team from their own third, out of possession to the opposition’s third, in possession, in a matter of seconds.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis piece, Monaco’s middle line of midfielders and full-backs were crucial for their incredible run of form to end the season, with the full-backs, in particular, coming in clutch in an underrated, crucial role in pretty much every phase of play.

I hope that this tactical analysis has shone a light on the key elements of Clement’s system and tactics at Monaco and has provided you with a better idea of how the Belgian coach oversaw Les Monégasques’ second-half-of-the-season transformation into a Champions League-worthy side.

Comments