After just a single season Norwich City have been relegated from the Premier League back to the EFL Championship. There are a multitude of factors that have contributed to the Canaries poor performance: ranging from macro-factors like a brittle defence, to a blunt attack. However, problems with defending set-pieces have plagued them all season – indeed throughout Daniel Farke’s tenure. Since the restart Norwich have conceded five goals from dead-ball situations (three from corners and two from free-kicks). These consistent issues and concessions seemingly indicate systemic weaknesses within Norwich’s structure. In this set-piece analysis, I will use analysis to see whether that is true.

This tactical analysis will look solely at Norwich’s tactics when defending set-pieces, and corners specifically.

Defensive structure

To properly understand why Norwich are poor at set-pieces we must look at their structure as a whole and then identify weaknesses within it.

As with most teams, Norwich utilise a mix of zonal and man-marking. This provides a balance, with the hope that deficiencies in either man-marking or zonal marking be offset by the other’s strengths. Farke splits it like this: five zonally mark, while another three are instructed to man-mark. I’ll expand on this further later but the personnel chosen to man-mark is a weakness in Farke’s defensive scheme.

Whilst aerial dominance is not a strength of the Norwich squad those most proficient zonally mark. Ben Godfrey and – from the restart – Timm Klose are these players. Therefore, they take up positions closest to Tim Krul in goal. This principle does not change whether the delivery is an in-swinger or out-swinger, albeit if the overarching structure adapts slightly to an alternative ball trajectory. Additionally, Alex Tettey occupies the far-post area, a more physical player so to cope with opponents seeking knock-downs.

The Norwich structure can be visualised above. Max Aarons has a dual role of preventing the ball going through the danger zone and being the man on the post. Due to his height (5’7”) such a role is understandable. The 10, Marco Stiepermann, is responsible for covering the near-portion and edge of the six-yard box. This has greater importance as it tends to be where runners from deep attack. Immediately behind Stiepermann is a line of three consisting of: Godfrey, Klose and Mario Vrančić. Because this zone is most likely to be where the corner-taker is aiming – especially with an in-swinger – this trio have to be aggressive, but disciplined in their actions.

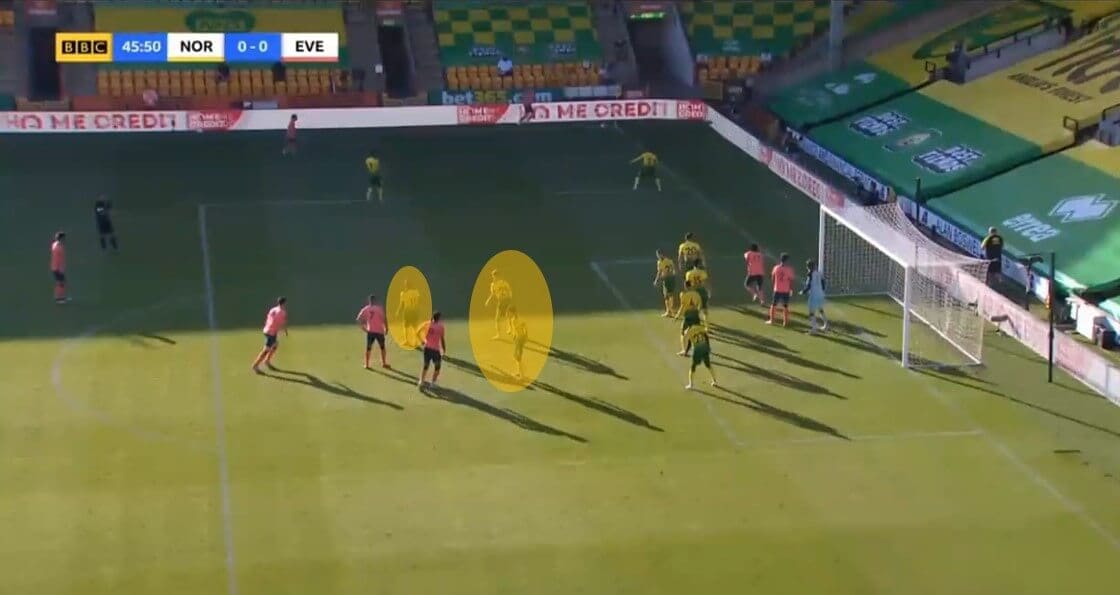

This next example illustrates how the structure changes in the case of a potential short corner. When this happens, it is Aarons who leaves his position to move out, therefore creating a 2v2. Onel Hernández is already further out thanks to his original positioning, which is also evident in the first image. Furthermore, this picture shows the man-marking set-up more clearly. Teemu Pukki is seemingly marking Declan Rice. However, Jamal Lewis and Emi Buendía are not spaced optimally, with them both effectively occupying No.28 Tomáš Souček, thus leaving No.21 Angelo Ogbonna free.

Here shows how Norwich structure themselves for an out-swinger. The regular five are this time positioned in a diagonal line. Consequently, they are ready for whatever height the delivery ends up. This also provides superior body-orientation as instead of being square as you can have a more open body position, which is beneficial when competing in aerial duels.

I’ll now look at the issues that have resulted in Norwich having the worst record in the division, having conceded 15 goals in 37 games.

Flatness of zonal marking structure

The purpose of zonal marking versus man is to achieve optimal coverage of the necessary areas relative to the type of delivery. The basis of this method is that your positioning isn’t dictated by the opposition, unlike with man-marking. Obviously, their aim is to score, therefore they will seek to manipulate the structure in such a way that creates separation and a clear path to goal. To ensure you’re covering all zones staggering is needed. Players should be located at differing heights to help maximise coverage. Of course, you need to factor in the goalkeeper’s unique ability to use his hands. But, by staggering your defensive shape, the delivery then has to be more pin-point and accurate to generate a solid chance.

Whilst Norwich do indeed favour zonal marking, they often neglect this crucial aspect. Instead, they opt for no, or minimal, staggering. By doing this they are only protecting themselves against different lengths of delivery, not varying height. For example, if the delivery is directed closer to the penalty spot than the middle of the six-yard box. The man-markers are then left on their own to win their battles if the specific delivery sees the zonal markers not needed. It is important to note that it does change for the better from out-swingers, with a more diagonal structure for the aforementioned five whereby they are pushing out as required.

We can see here against Brighton the normal line of five are located relatively deep due to the in-swinging delivery. Two players have been drawn out, further emptying the penalty box. What is noticeable, however, is the relative flatness of the players who are zonally marking. There are two players covering the near-post section, with the second slightly higher than the first. But there is not enough variation in how deep the five are individually positioned. Some should ideally be higher and can attack the ball earlier, against the Brighton players who will always have more momentum. Tettey being the deepest also arguably seems inefficient as he is one of Norwich’s most physical players; I’d prefer him to be more central in a role where he can utilise his skillset better.

We can see this once more against Manchester United, although Norwich were down to 10 men at the time with Klose having been sent off. This results in a rather baffling scheme where they are seven players in deep areas, but not structured in a coordinated way. As a result, their structure seems quite basic, with coverage sub-optimal. For instance, there is no depth present whatsoever, meaning the United players on the edge of the box would hypothetically have undue time – because immediate pressure cannot be applied due to where they are originally.

Here is an example in which – unlike the Arsenal one earlier – Norwich’s spacing is poor. The quintet should preferably be spaced so they are moving away from goal; therefore, they can react appropriately to varying lengths of delivery. Additionally, Aarons being where he is doesn’t seem very useful considering it is an out-swinging delivery, so there is no need to protect that specific area.

Problems at the near-post

The near-post is statistically the place where the most shots are taken from in corner situations. It makes sense; it’s the place closest to where the corner is taken, with less opportunity for the opposition to interrupt the ball flight. Therefore, occupancy of this vital area is imperative, along with optimal spacing in terms of depth and body-orientation.

These next images show the sequence of events that leads to West Ham’s opening goal. Only Stiepermann is covering the near-post area in the image above. In addition to this, he is arguably too deep, with the German leaving the corner part empty. Rice darts towards this space, bringing his marker Pukki with him, and creating extra space centrally. Issa Diop is located on the blindside of Stiepermann. Aarons’ positioning results that in the crucial second phase – when Diop flicks the ball on – Antonio doesn’t have to worry about remaining onside. We can this ensue here below.

Rice’s run creates a yard of space for Diop to step into. Admittedly, he is given help by both Stiepermann and Pukki challenging Rice, even though the ball goes over their heads. The West Ham centre-back is able to get to the ball easily due to his offensive movement coming from Vrančić’s blindside. Antonio moves right to left due to where the ball is going but still scores fairly. While there is a valid argument for having a man on the post perhaps putting Aarons in the aforementioned unoccupied near-post space would be wiser.

Here again we see how it is effectively just No.19 Tom Trybull who is patrolling this zone. Indeed, for an in-swinger the ball is likely to go in or around here. The structure here would improve if Trybull had a teammate located slightly higher on the edge of the six-yard box. This would provide protection at a different height. Furthermore, presence there would naturally impede Arsenal attackers beginning their runs from a deep.

Here Norwich have left an even greater portion of the near-post zone unoccupied. Aarons has pushed out in case of the short corner, thereby causing Stiepermann (already the lone marker) to pull deeper closer to the goalmouth. Also, Souček has moved much closer to Krul centrally, resulting in some general congestion here. Subsequently, with a free near-post to exploit and Ogbonna having qualitative superiority over Buendía then they can take advantage of Norwich having issues with adjusting to different circumstances.

Wrong man-markers

Although many teams opt to have their most aerially proficient defenders in a zonal structure – a logical decision – physicality is arguably an even more important trait when man-marking. The role of the man-markers is to act as blockers to reduce the momentum attackers from deep can have, thus benefitting them versus the static zonal markers. Therefore, these players should ideally be also able to hold their own over tall, sizeable attackers who are seeking to attack the corner from a position that is originally deeper, in order to gain superiority over the opposition zonal markers.

This is an issue with Norwich. The Canaries squad profile doesn’t lend itself to physical attributes, and those who do go into the zonal marking scheme in the goalmouth. Consequently, the three man-markers are usually: Lewis, Buendía and Pukki. Naturally, this alters with changes in the team. This trio, however, are not suited to the role and do not sufficiently possess the attributes required. However, I think Farke has other, better, options, such as Hernández (who has been used here on occasion) and Stiepermann who can cope better with the demands of this role.

The example above illustrates this extremely well. Buendía is at the back-past tussling with Watford left-back Adam Masina, who has got goal-side. Elsewhere, Pukki and Lewis are locked into duels more centrally. The consequence of this is that Danny Welbeck has become free in a very good position with clear access to the goal.

Here Norwich’s man-markers are evident against Chelsea. In this instance it is Lewis, Hernández and Lukas Rupp who are assigned to the role. Their responsibility is arguably even greater here because of the increased gap between the two distinctive structures. This would allow the deeper Chelsea attackers to create more momentum and overpower Norwich’s zonal markers. Lewis, Hernández and Rupp are positioned rather simplistically here, thereby meaning Chelsea can create separation easier.

Conversely, here versus Everton, we see a better example of how the three man-markers can be utilised better. Hernández is on a line higher than Lewis and Ondrej Duda – a nice example of staggering. Moreover, they are perpendicular to the three Everton players, this is more advantageous for Norwich as offensive movements can be disrupted easier.

Conclusion

Defending corners has been a consistent issue throughout Farke’s reign. Since he took over Norwich have conceded 33 goals from corners, 18% of all goals conceded during his time. This indicates that upon their return to the EFL Championship – a notoriously physical league – adaption may be necessary to minimise concession from these situations. Perhaps summer recruitment may have to be conducted in view of signing more players who are adept aerially.

Comments