Chelsea have been in the headlines of late due to their perceived inability to defend set-pieces effectively, with their Premier League game against West Ham United highlighting this to the masses. This struggle from set-pieces has been occurring all season, with the Blues totalling up fifteen goals conceded from indirect set-piece situations, with nine of those coming from corners. Frank Lampard recently suggested that his recruitment may have to be adjusted in order to allow more height into the side, with this height seemingly viewed as one solution to their set-piece problems. In this tactical analysis, I’ll focus on Chelsea’s defensive corners and highlight what exactly the problems are, as well as then identifying how these problems can be solved, with adjustments in positioning, staggering, and structure considered along with individual player behaviours and coaching points being identified.

General structure

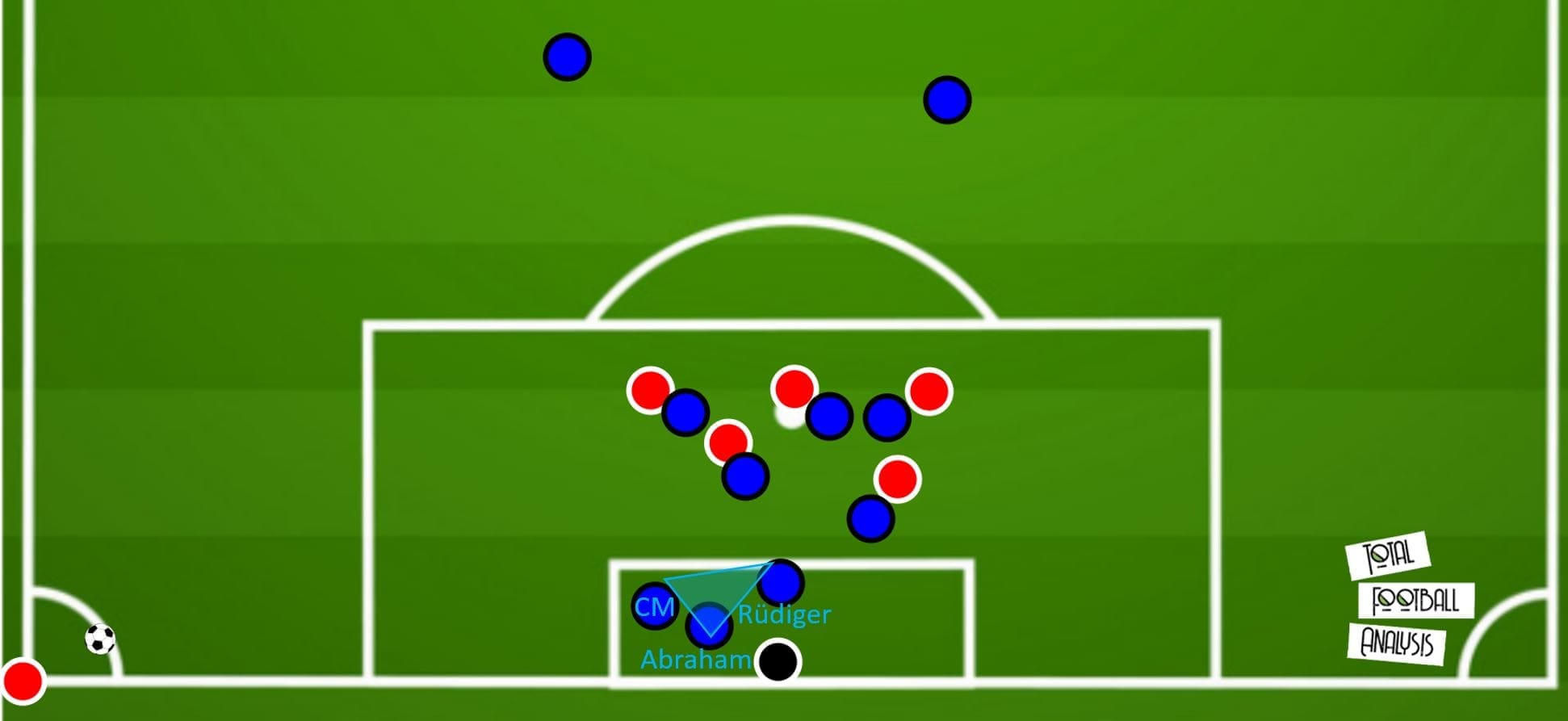

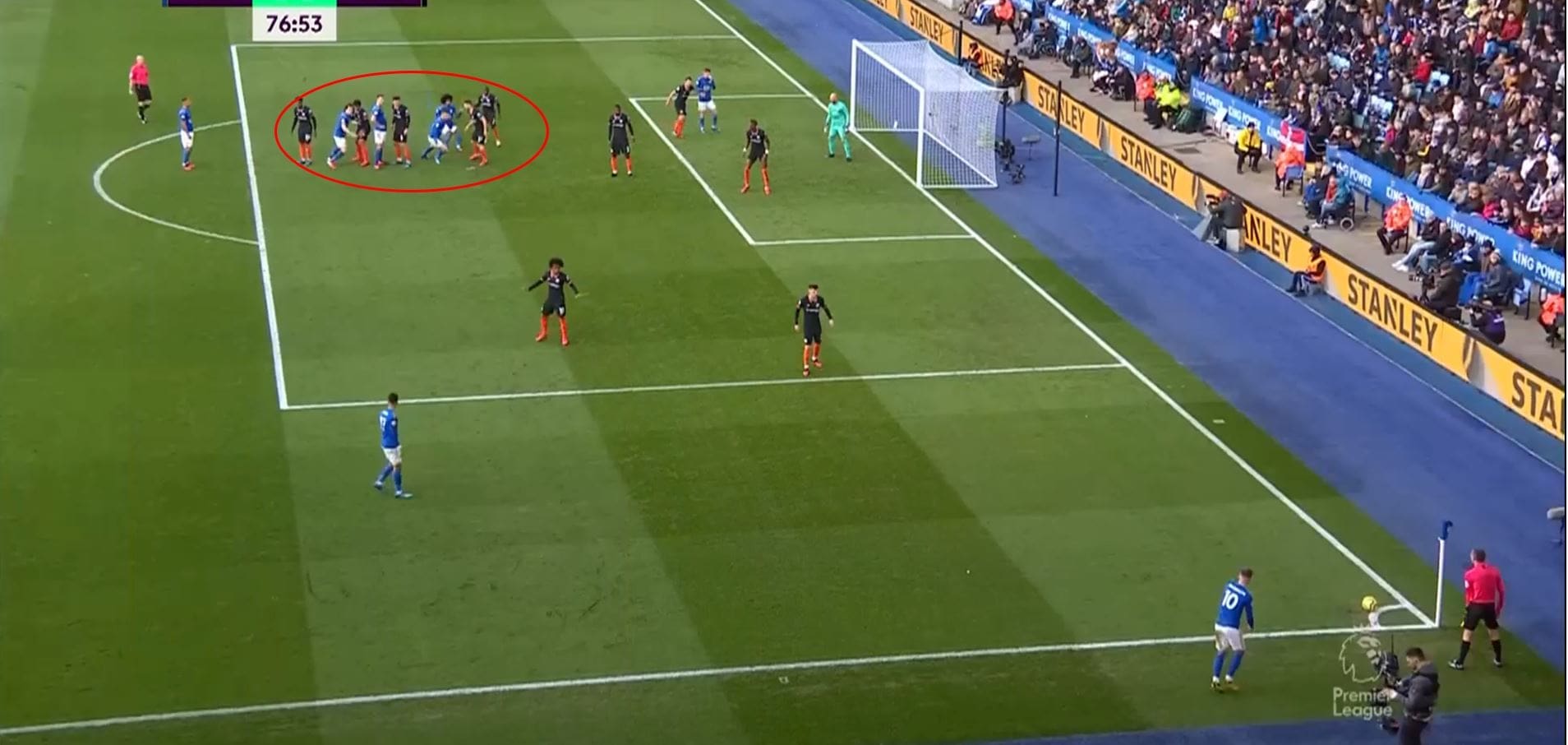

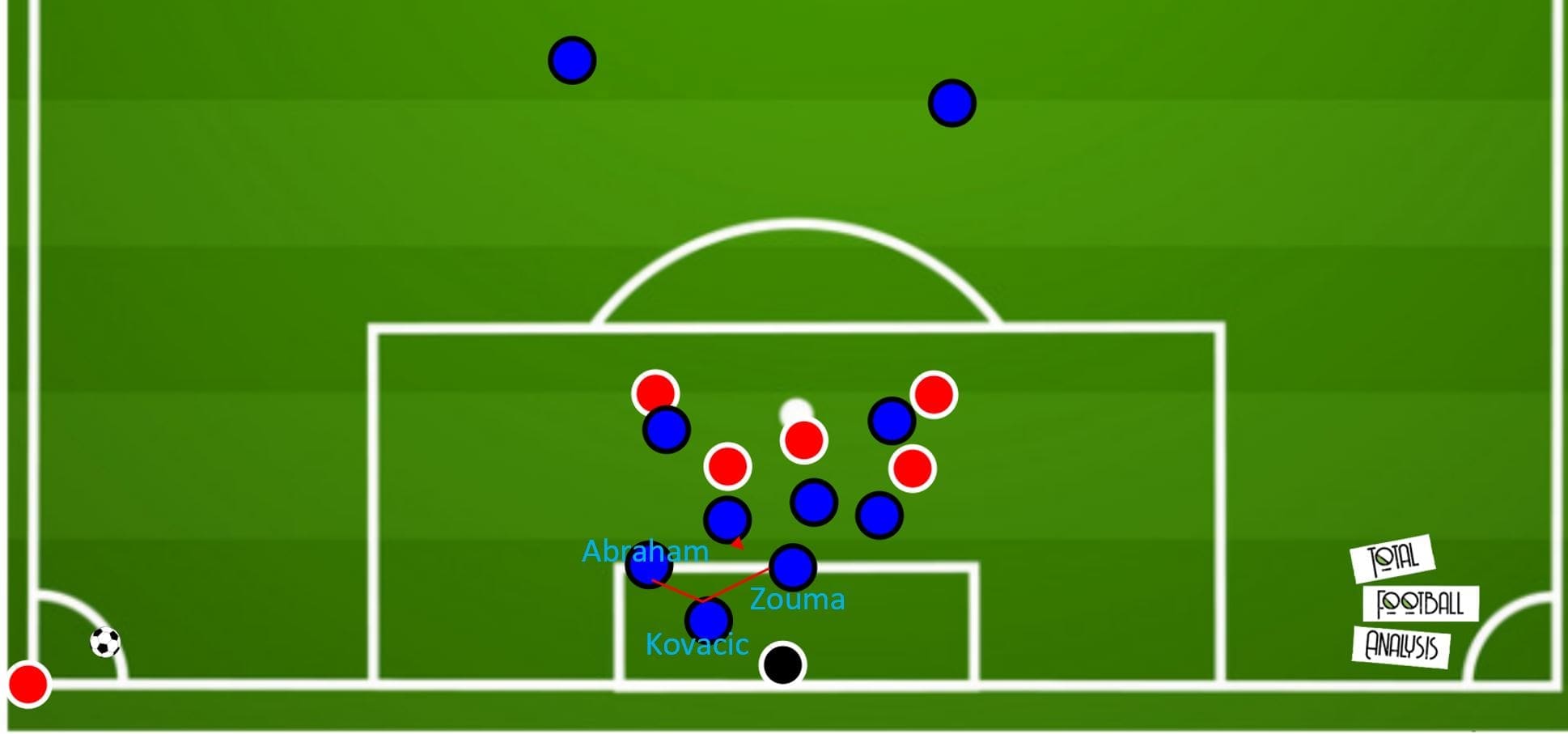

It makes sense to start with the structure Chelsea use to defend corners, with this outlined in the image below. Chelsea’s general structure from mid-October onwards has been a mix of zonal and man-marking, with a three-man zonal system and usually five-man markers. Due to Lampard’s rotations in the starting eleven, Chelsea’s players within the zonal system do change occasionally, but when they do, they tend to just be like for like replacements. Antonio Rüdiger occupies the central zone most often, while if he does not play another centre back will fill his role. Chelsea rely on a striker for the deeper near post player, and so this season it has been Tammy Abraham or Olivier Giroud. The near-side six-yard box zonal role is occupied by one of the Chelsea central midfielders, which due to the particular amount of rotation in this area has seen Jorginho, Kanté, Kovačić, and Mount all take up this role throughout the season. The staggering of this zonal system has been inconsistent at times for Chelsea and this is a key area which will be discussed.

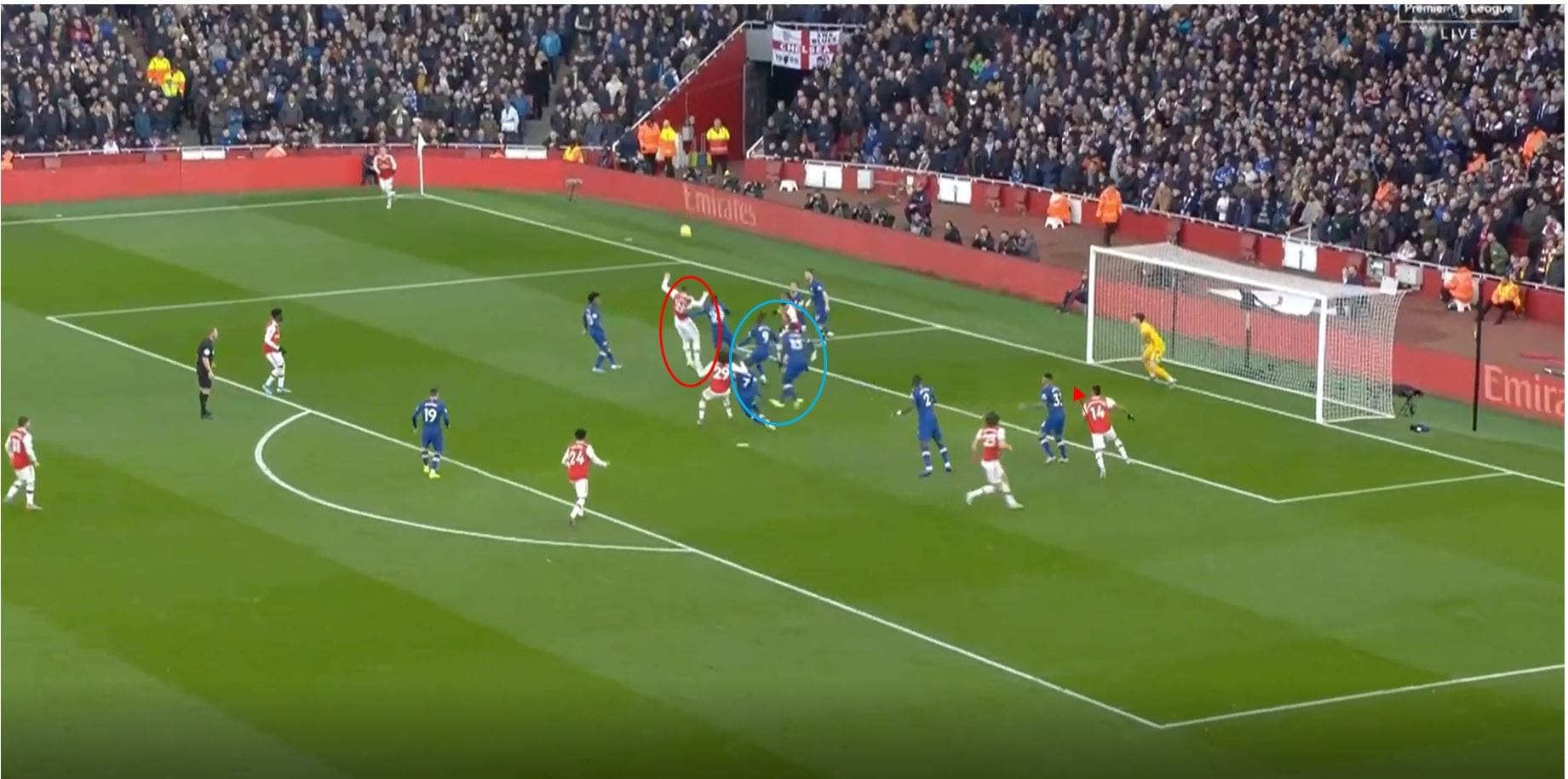

In this structure and staggering against Leicester, we can break down the roles of each player clearly. The central midfielder Billy Gilmour protects the near side of the six-yard box and is responsible for dealing with any short or low crosses into this zone. Gilmour must also be prepared to step out a yard or two to cover the edge of the six-yard box and protect the corner of the six-yard box, which is where we see Jamie Vardy running into here. Tammy Abraham is in a deeper role and has the task of protecting any deliveries that go close to the touchline, in order to prevent the ball possibly evading the coverage at the near post and going through to the goalkeeper or directly in. Abraham may push out a yard or so, but his body language tells us he’s wanting to move forward towards the corner taker, rather than outwards. Kurt Zouma takes up the most central role, and he takes up a slightly higher position, with his main role being to cover this central area and head the ball away if it enters this zone.

Some of the gaps in zonal coverage, therefore, are the edge of the six-yard box between Zouma and Gilmour, and the most obvious one, the back post. Chelsea’s structure offers no zonal coverage of the back post, and so instead it is up to man markers to battle physically with their opponent to prevent them from receiving a header. Again this is something we will be back to shortly.

When teams commit a player short, Chelsea sacrifice the nearest zonal marker to create a 2 v 2, and so as a result we see here Mason Mount vacates his zone.

From the start of the season to the October international break though, Chelsea actually used a different system, instead relying on a far more zonal system comprising of five zonal players and three-man markers. The poor behaviours shown by their zonal markers though led to them conceding goals early in the season, and so since mid-October, they have adopted that three-man zonal structure previously mentioned.

Now we’ll move onto what the problems are with the system and how they have been exploited.

Poor zonal marking

One of the main issues Chelsea have faced has been the staggering of their zonal markers and the height of their positioning. When highlighting the roles of each zonal player, I showed the distance each player can cover when moving forward in order to challenge for headers. Many of the goals Chelsea have conceded have come directly from those areas (or just outside) where zonal markers should cover, and so what is the problem with the zonal markers?

One common trend in Chelsea’s season has been the height of their zonal markers positioning, particularly from out-swinging corners. The height/depth that the defending team takes from corners is dependent on what kind of delivery is coming in. In-swinging corners obviously swing towards the goal, and so naturally, the defending side drops deeper from in-swingers to protect the goal. Oppositely, for out-swinging deliveries, the ball is going away from goal, and so the defence should push higher in order to cover the higher areas of the box.

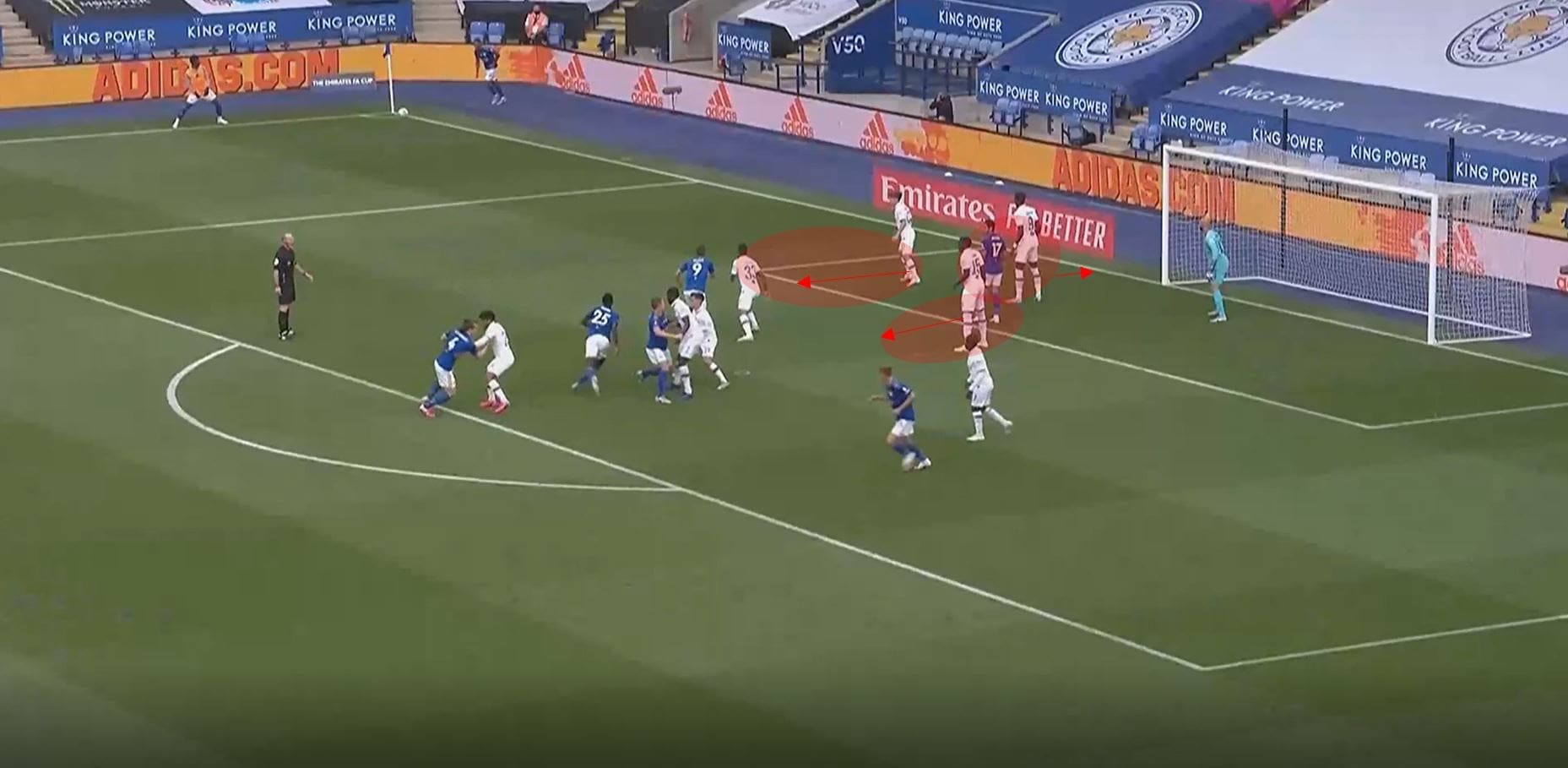

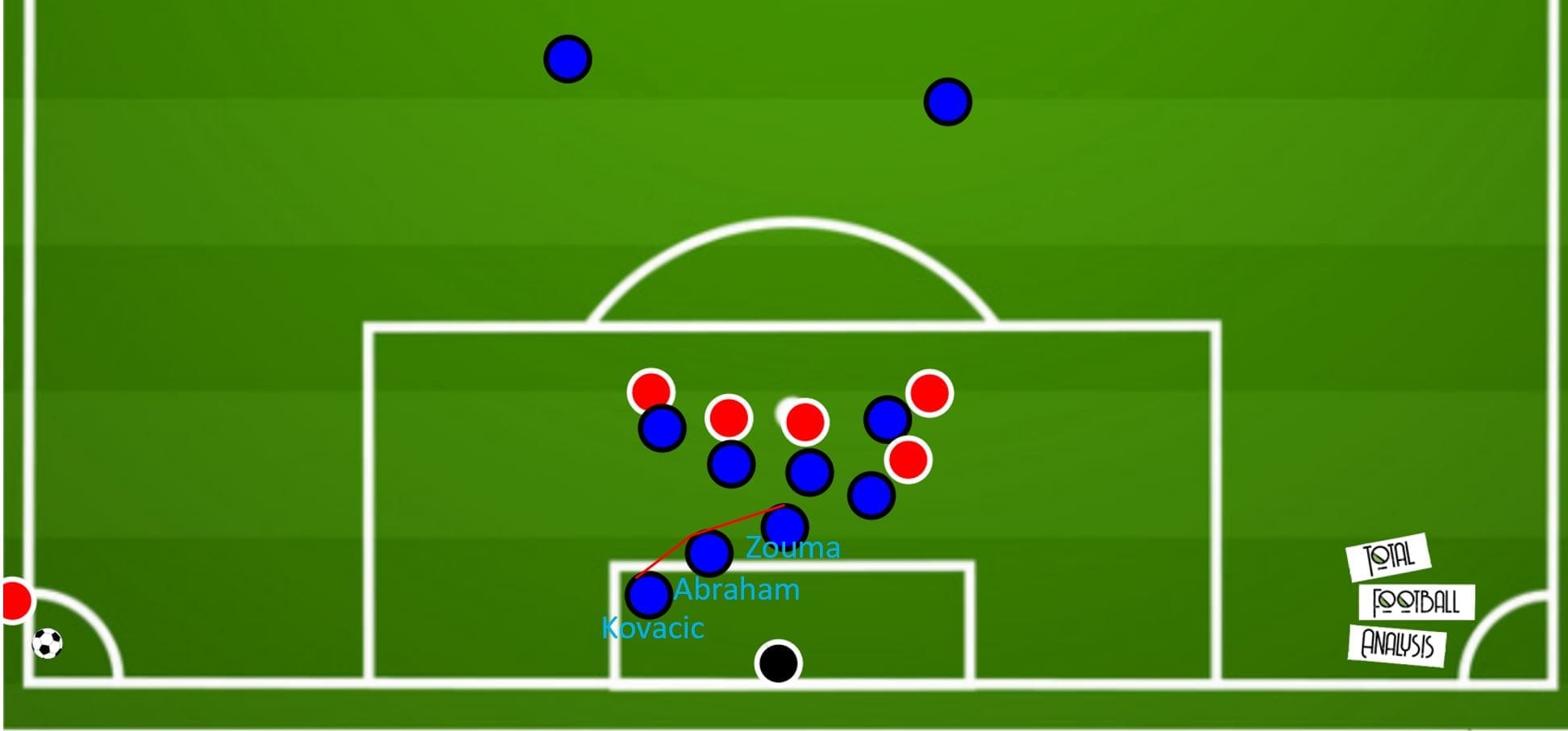

Chelsea have been guilty this season of being too deep from out-swingers, and so opponents have found success in deeper deliveries to central areas. Below we can see a good example of Chelsea’s poor zonal occupation against Arsenal against an out-swinging delivery. We can see Abraham stands just inside the six-yard box while Zouma is slightly outside. Arsenal stay reasonably deep, and so the space highlighted below is created. Arsenal end up scoring from the circle shown. Abraham in particular is just too deep with his initial positioning and as a result, can’t push out far enough to challenge for this header.

If we analyse why he stays deep, we can assess that it is likely to protect this near post space behind the central midfielder, as Arsenal commit a player around this area. However, Chelsea have to learn to adjust to such changes, and so here, Kovačić can afford to drop deeper into the space behind him, which then allows Abraham to push forward.

But as it turns out, the first contact is not the only problem. Arsenal here use a very well designed routine in which Aubameyang ghosts round his marker at the back post, but this routine is allowed to happen due to the poor discipline of Chelsea’s zonal players. The whole point of zonal marking is each player covers one specific zone, and moves out should this zone be engaged. Each player’s individual coverage builds into one system which gives a maximal amount of permanent coverage, and so regardless of what the opposition does, the structure remains mostly the same and the same zones are occupied. If players zones aren’t engaged, they shouldn’t move out and players have to avoid being drawn towards the ball, otherwise, that structure immediately collapses.

Kurt Zouma here gives a great example of how not to defend in a zonal system, as from his starting position (see image above), he pushes out towards the ball and ends up just behind Abraham, despite having no realistic chance of getting the ball. As a result, when Arsenal win the first header, they have a clear path through the centre for a flick-on through to Aubameyang. The only reasonable explanation for this movement from Zouma would be to play offside, but if that’s the case nobody else seemed to get the message, and mostly man-marking doesn’t lend itself well to this.

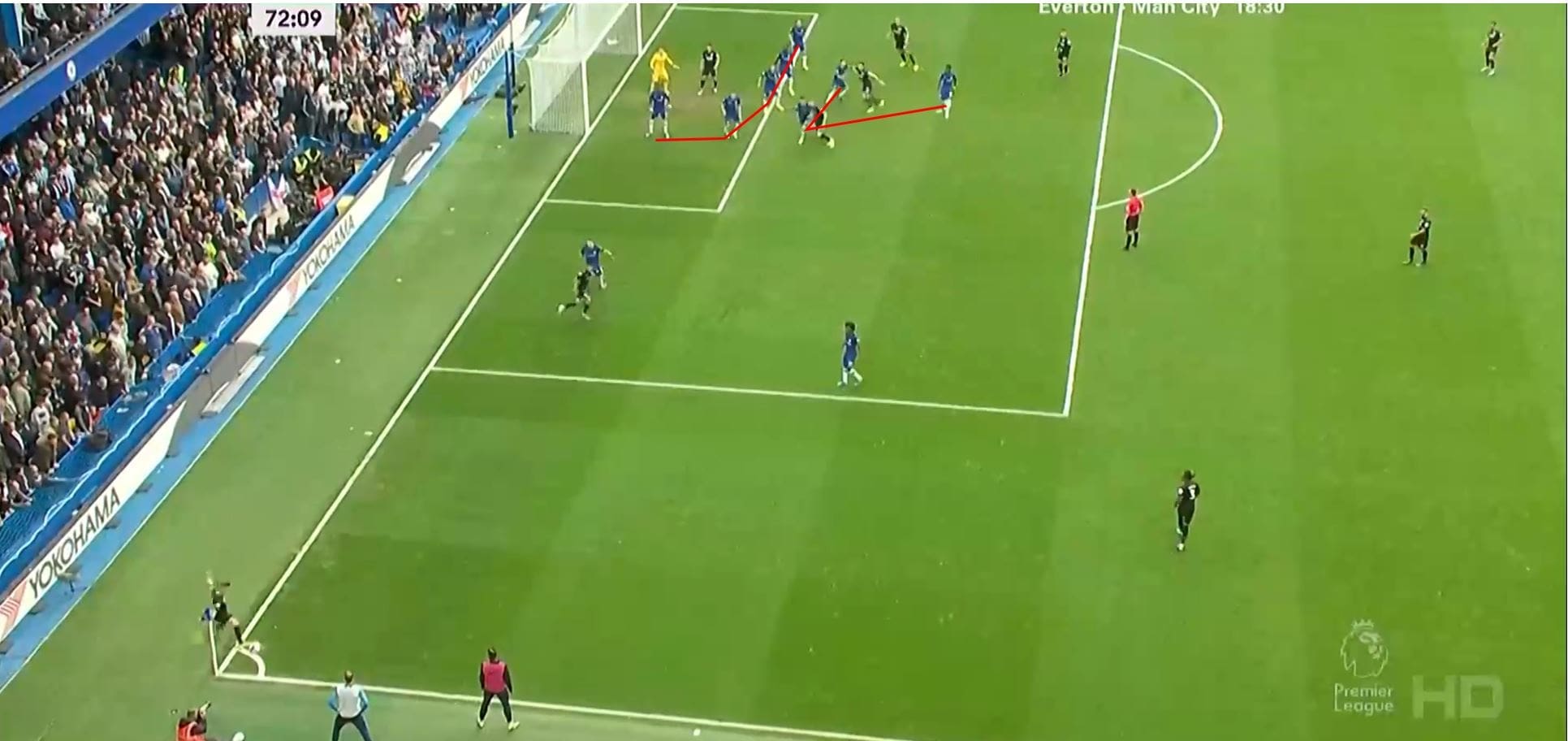

Here Chelsea fall victim to their own zonal structure again, with their staggering again different. Here, the near side six-yard box marker (Mount) now takes up the role of protecting the touchline area and looks to prevent the ball from going all the way through to the goalkeeper. Tammy Abraham and Kurt Zouma are now in much higher positions and are both mostly orientated towards the central areas. The depth needed by Mason Mount to protect this lane, as well as the height seen by Abraham, means the near post area is now fairly unoccupied.

As a result, when Ajax make a run towards the near post, because Abraham is in a more central position, he cannot get out in time to reach the player and cover the corner of the six-yard box. Again, simple adjustments would allow them to nullify the threat, as here they look to protect the touchline delivery, but it is an out-swinging corner. Mount could simply move more towards the corner of the six-yard box to cover this zone more effectively, as an out-swinging delivery is not going to threaten to catch a goalkeeper off guard and go straight in.

A more permanent structure with consistent staggering would also help to improve Chelsea, but with only a three-man zonal system problems in terms of coverage are always likely to come up, as three players can’t cover all of the spaces effectively, and Chelsea always seem to be compromising slightly due to their lack of numbers in this regard.

Disorganisation can also be a factor if teams are unsure on their spacing, and we can see an example of this against Bournemouth. We can see Chelsea’s three-man zonal structure is not yet complete, with Andreas Christensen still dropping deeper into shape just four seconds before the ball is in the net for Bournemouth.

Chelsea do get into their shape, but again their staggering is not ideal, and Christensen fails to jump higher than one of the deeper runners, which is also in part down to the man markers, whose job it is to block those deeper Bournemouth runners.

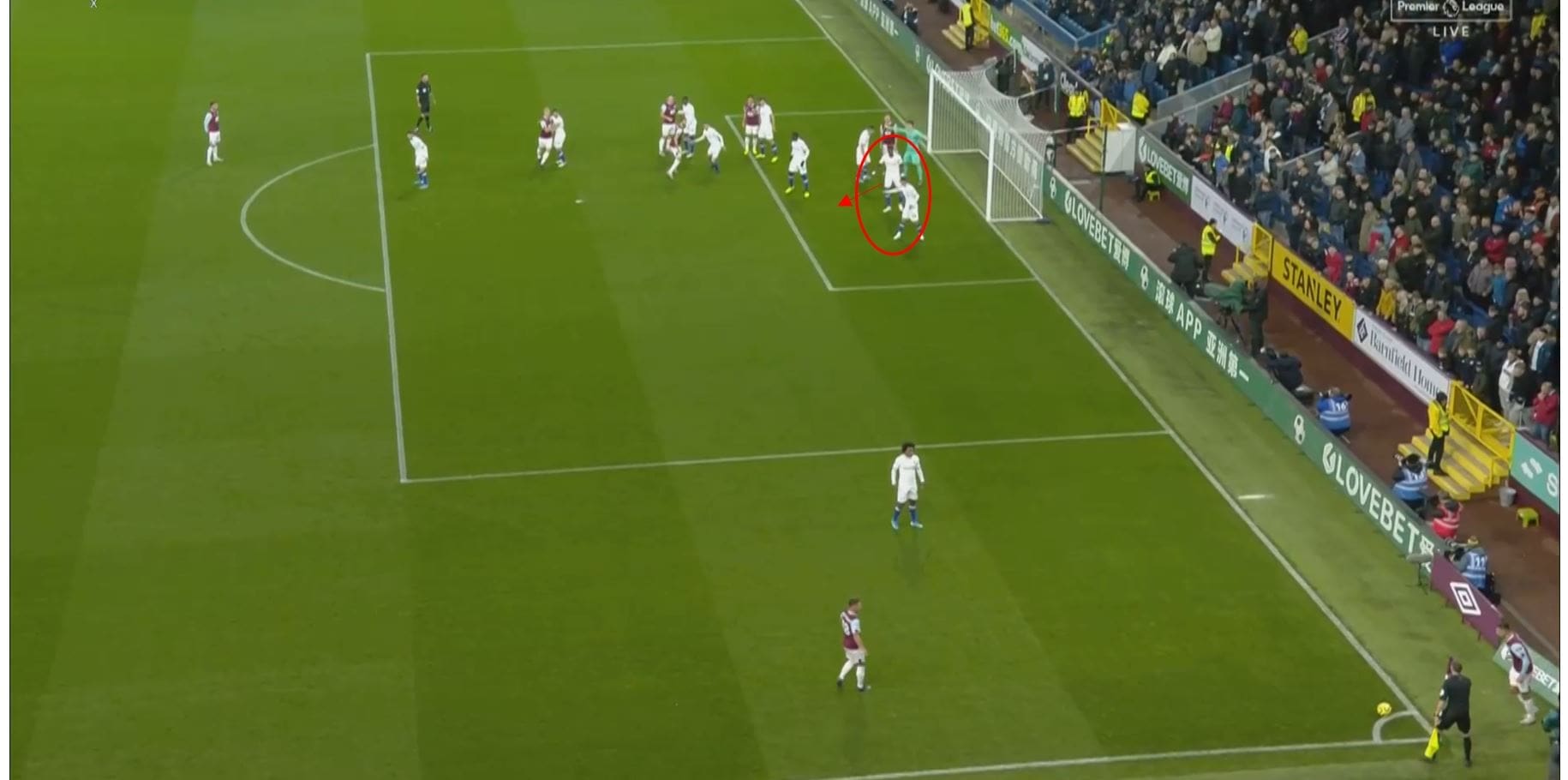

Here, just before the corner is delivered, we see Jorginho organising Chelsea’s staggering, with the Italian clearly telling Abraham here to push forward slightly, which to me isn’t a great sign just before Burnley deliver a corner.

In summary then, in this section we have discussed:

- Chelsea’s three-man zonal system and their inconsistent staggering

- Their coverage issues in a three-man structure.

- Chelsea’s poor height of the zonal line, particularly against out-swinging corners

The role of the man markers

The role of a man marker is to stick with a specific player and prevent them from gaining a clean header on goal, but while used in a zonal system, they must also act as blockers to slow down runners, otherwise, an opponent can gain a free run at a zonal player, which due to the differences in momentum can cause problems. Although, as we’ve pointed out, Chelsea’s zonal markers have not performed well throughout the season, their man markers have also been poor and played a hand in several goals being conceded.

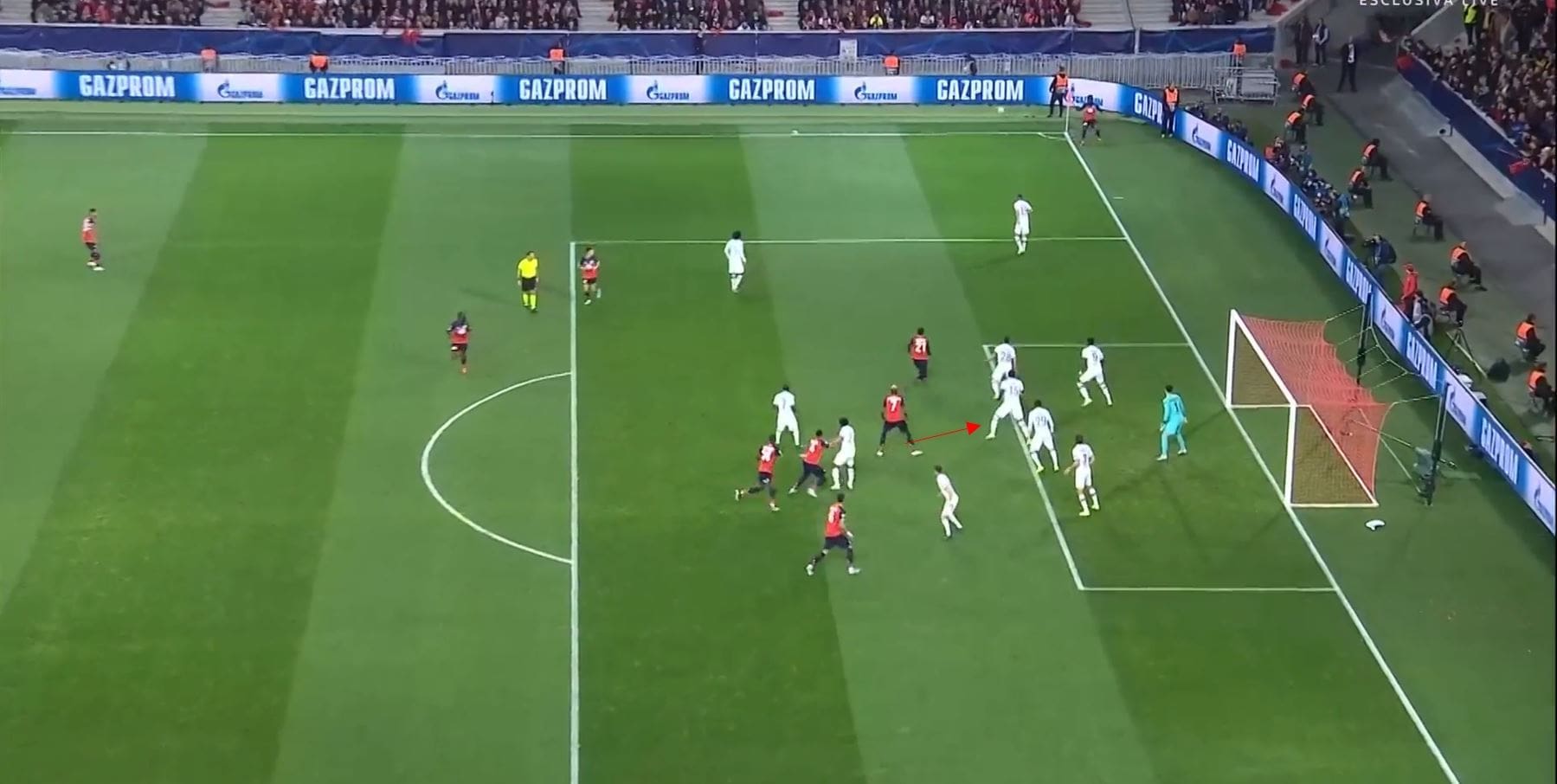

In this example from earlier in the season, we see Chelsea’s man-marking is terrible, but because the system is mainly zonal, I would guarantee many people at the time blamed the zonal marking, when in fact this is largely down to the man-marking Chelsea have (not) used. We can see Chelsea commit three-man markers and have a five-man zonal structure (shown earlier), but Lille’s main goal threat Victor Osimhen is not marked, and is allowed a free run at the zonal structure. The ball lands directly in Osimhen’s path, and although Christensen could perhaps do better to win the header or put off Osimhen, beating a man in the air who has a run up on you is difficult. Adjusting the system or structure would provide Christensen better protection, and help to slow Osimhen down and prevent him from scoring.

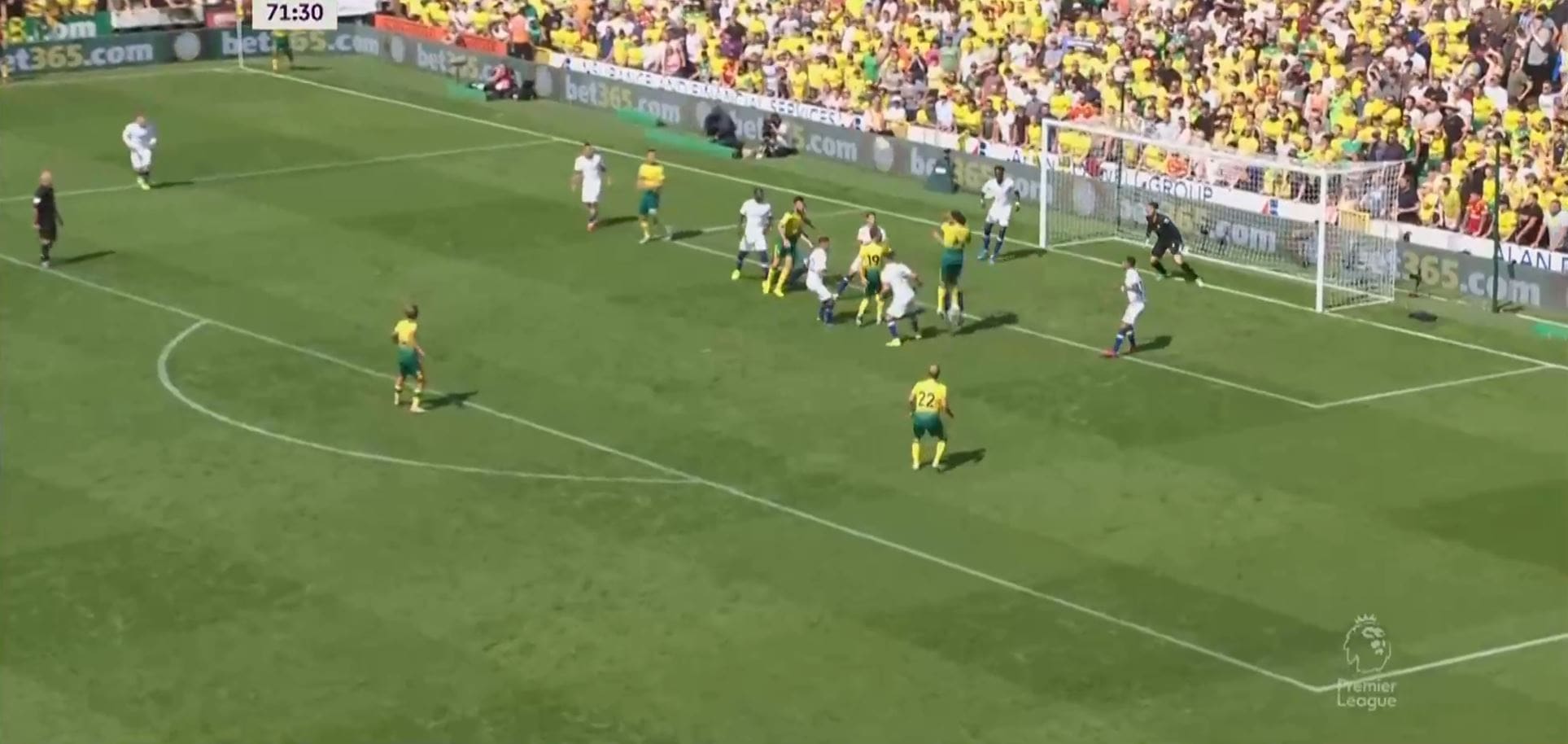

Here again early in the season with that five-man zonal structure, the ‘zonal marking’ is blamed, but in reality it’s the man markers who don’t do their job, although Chelsea’s choice of personnel is questionable. Ndidi here starts closest to Jorginho, but Chelsea’s marking is disorganised, number 22 Pulisic and Jorginho (five) seem to mark the same player, and Ndidi is left to run completely free onto César Azpilicueta. I would not choose Azpilicueta to occupy this zone, but if you place a man marker on Ndidi you slow him down considerably and can guide his run elsewhere.

Here Chelsea’s markers are not physical enough again, as they should act as a literal shield for these zonal players. Again, it is Christensen who is isolated by the opposition, and he is forced to jump with a marker, where he should probably do better, but once more the Chelsea markers don’t do enough. They don’t have to win the header, they just have to do enough to put off the header.

If we look at Liverpool’s structure here, their second line aims to block runs into higher areas for the Bournemouth runners. They don’t push high to meet the runners and mark them tightly, and instead just act as a kind of shield or net to catch players running from deep and slow them down.

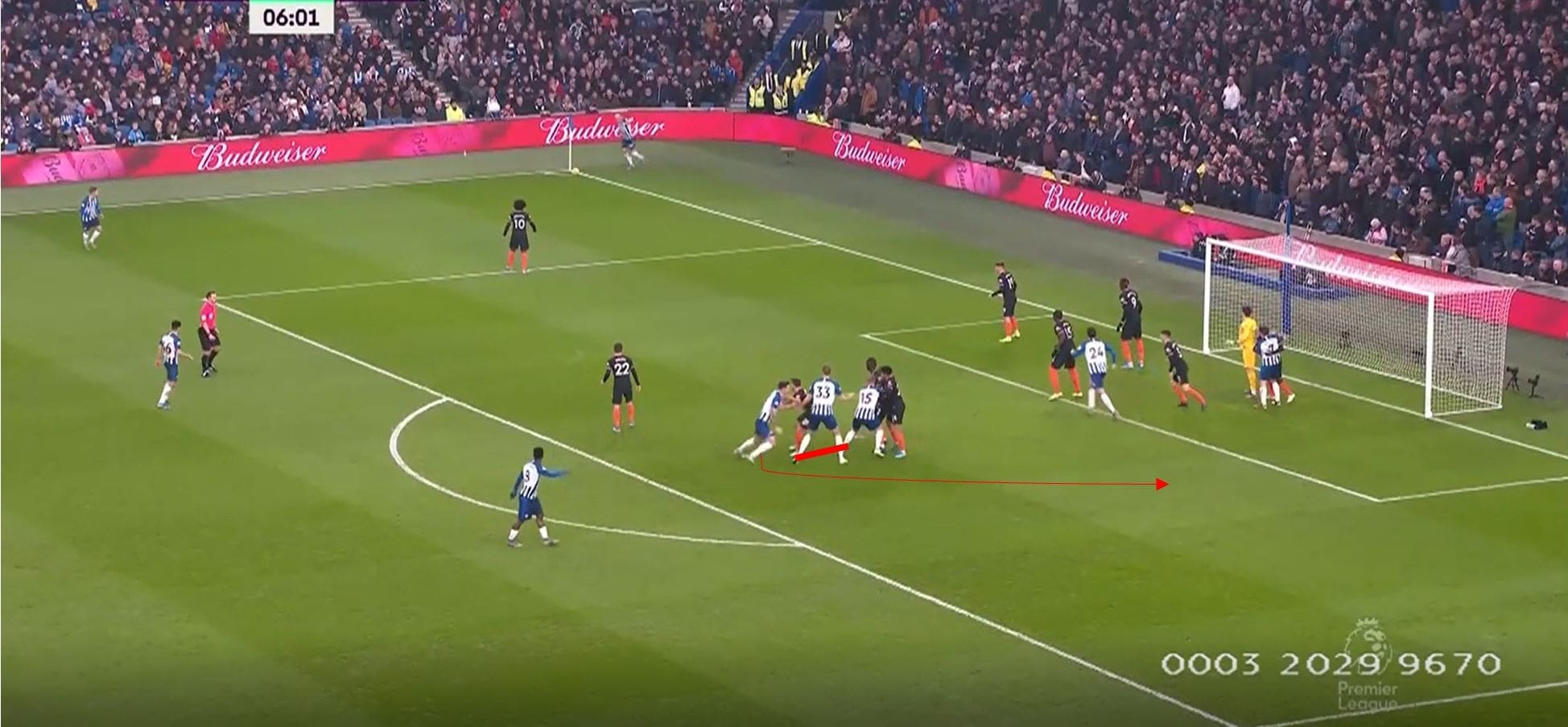

Chelsea’s man markers have also struggled to defend groups or trains of attacking players from corners, and don’t seem to have been coached on how best to defend these types of situations. Here Leicester set up in a train, with their attackers lining up one behind the other. Chelsea opt to simply match their structure and line up in the same way, which makes it much easier for Leicester to execute blocks on markers and create a free man.

A flat line of players perpendicular to the train would allow for players to be marked more effectively, as roles can be allocated more easily and blocks are much more difficult to put in place. We see here Chelsea again commit a player into the group of attackers, and as a result Brighton are able to execute a nice block before heading to the unoccupied back post area.

Back-post occupation

Another area in which Chelsea’s man markers have been weak is with their ability to follow players runs, with the majority of these being made towards the back post. As touched on, Chelsea’s current zonal coverage provides no coverage of the back post area, and so as a result Chelsea rely on physical 1 v 1 battles at the back post, which as they found out at West Ham, isn’t always the best option.

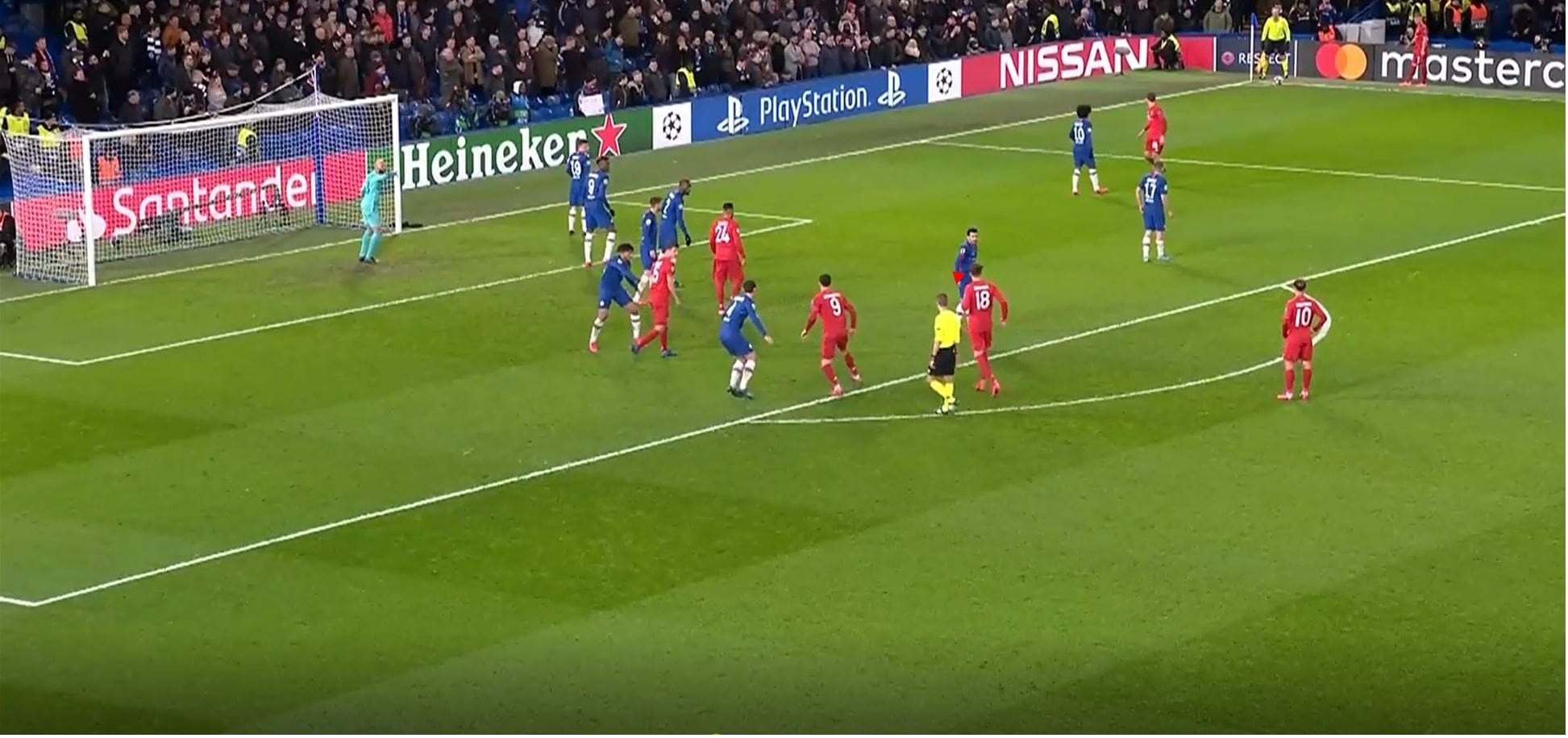

Chelsea’s marking of players moving towards this area can be extremely poor, and we can see an example of this here. Pedro quite clearly looks at Leon Goretzka, but rather than following decides to stay in his position for now. All of the other Chelsea man markers are marking.

Goretzka then has a simple free run towards the back post, and Chelsea have no zonal occupation of the back post, and so when the majority of the Bayern runners run to the back post, Goreztka is completely isolated for a free header on goal. Granted this is late on in the game, but other examples also show this to happen often.

We can see here Ben Chilwell starts centrally but spins off towards the back post, with his marker facing the wrong way and not actually recognising this.

As a result, again we see a player receive relatively unmarked, as all players have to do is lose one player and the back post is open. Some kind of zonal coverage of this area would help to nullify this threat and prevent teams from finding such space.

Deliveries to the back post do rely a lot on physicality, as players are battling for a slow-moving, lofted delivery and often stand still rather than move onto the ball at speed, and as a result, Chelsea have conceded goals from this back post area, even when markers have stayed with players. The goals conceded most recently against West Ham, and Harry Maguire’s goal against them best illustrate this.

We can see Azpilicueta stays with the West Ham attacker, but it is just a case of physicality and dynamic superiority. Because Azpilicueta starts in a higher area and is facing his marker, he has to turn to track the run, while West Ham are just running forwards. As a result, Tomáš Souček is able to win the header while Azpilicueta is in an awkward body position. Personnel can be blamed but the system doesn’t help at all, and back post runs are very difficult to track and stop because of that dynamic superiority.

Adapting or changing the system?

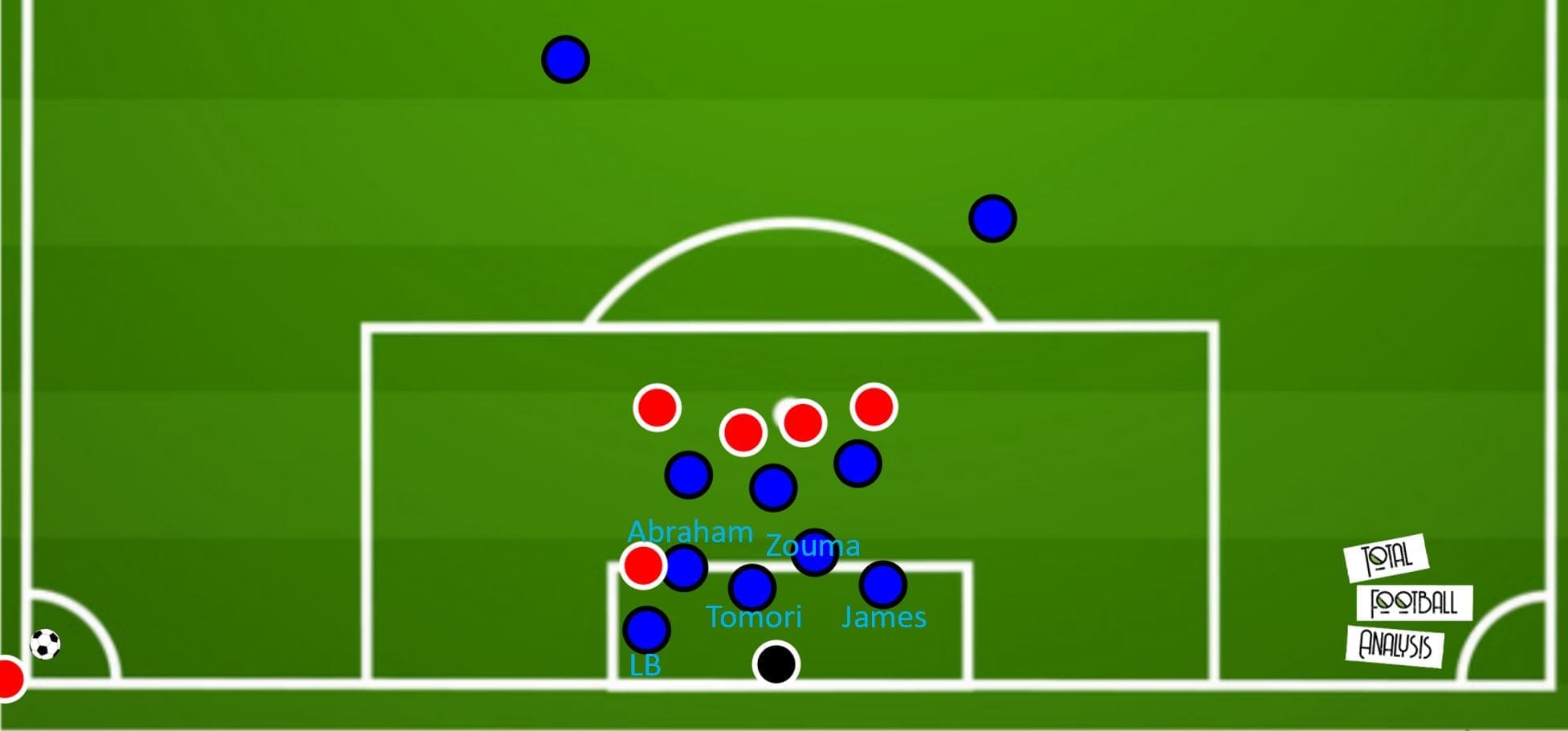

Every system has its advantages and disadvantages, and so it is a difficult decision for Chelsea as to whether they refine their current system, or revert to a different one. This section will look at the pros and cons of a refined version of their current system compared to an alternative, and recommend a system for Chelsea. If we start with adapting the initial structure I’d recommend the use of personnel in this way. A central midfielder with decent height for example Kovačić occupies the lane towards the goalkeeper while defending an inswinging corner. Kovačić has a good mentality and will go towards the ball bravely, and his height is not massively needed in this role. Chelsea have used Tammy Abraham in this role for most of the season, but this role doesn’t involve challenging the opponent, it simply involves cutting a passing lane. As a result, height and physicality isn’t a huge factor, and so a smaller player can be sacrificed in here. Azpilicueta could also be another option here.

Abraham moves higher onto around the corner of the six-yard box (or slightly deeper for an inswinger), as he is tall and mobile and has decent aerial ability. This zone will involve the defender moving outwards quickly, and challenging for headers with opponents, and so a player who is capable of closing space fairly quickly while being tall is an excellent asset. If we go back to the Ajax goal example, Abraham’s starting position doesn’t help him but he is able to get a foot in which helps to put off the Ajax attacker somewhat, and so he is likely to be coachable in this area.

Kurt Zouma occupies the central zone, as he seems to be the best header of the ball and best aerially for Chelsea. He needs to be coached around when to move from his zone and when not to and also around the height of his positioning, but he represents the best option for Chelsea.

The man markers are positioned deeper and look to use the coaching points discussed to act as a shield for the zonal players, particularly for the space in front of Kovačić.

For out-swinging corners the structure looks more like this, with increased staggering and height allowing for better coverage of the near post and central areas. Abraham is able to push out both sideways and forward to help cover the near post and central zone, while Zouma is better placed to compete with deeper deliveries.

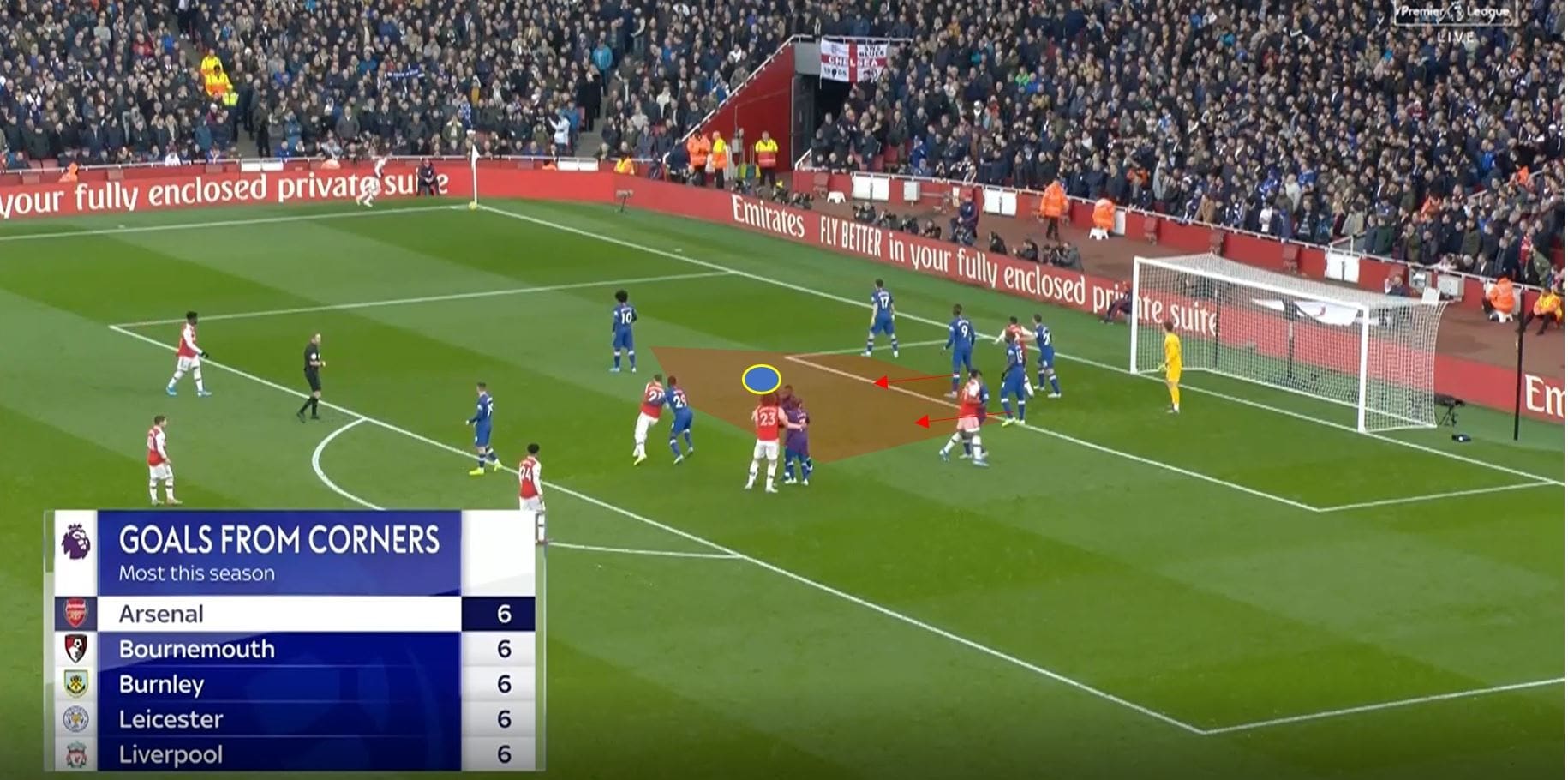

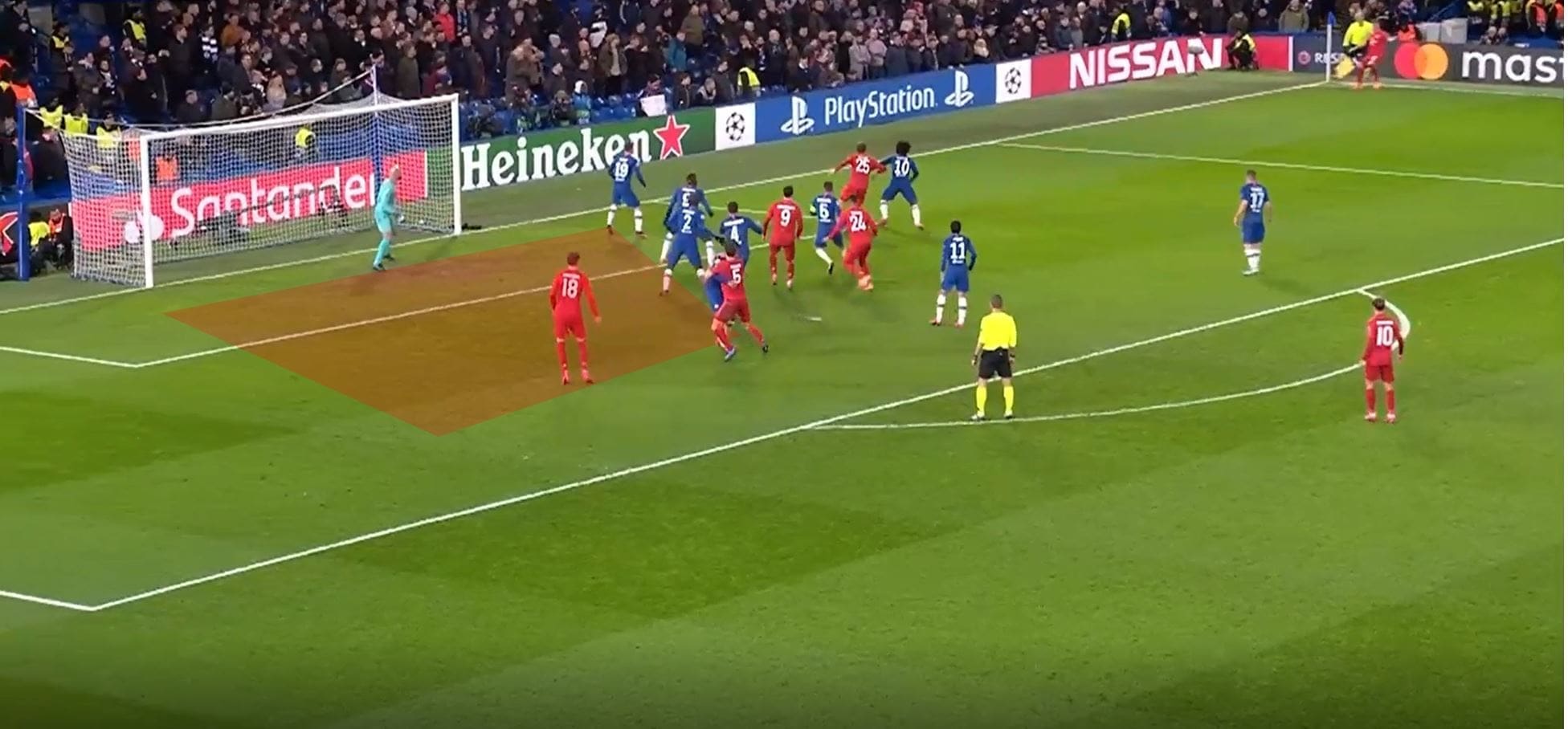

An adapted system actually takes us back to their original system at the start of the season, but with improved staggering. Notice how the higher, deeper, higher, deeper structure that is in place which allows for maximal coverage in each area. This is a system many sides use and is perhaps used most successfully by Liverpool and RB Leipzig. Two players cover the near post region, with one player slightly higher than the other, in order to cover delivery in front. The nearest player’s role is to prevent a flick on and to protect the near post touchline area, so the ball doesn’t go all the way through. Two players then cover the central area, again we see good staggering with the players at different heights, which helps to maximise coverage of each area. If the ball goes behind this highest player, you would expect the goalkeeper to claim it. Likewise, if the ball goes ahead of the deeper of the two central players, you would expect the near post markers close to him to cover it. There is then a back post zonal marker who covers the whole back post region. It is vital the spacing between each player remains optimal and that each zone remains covered, otherwise opposition players can occupy and win headers in these zones. For more information on how RB Leipzig use this structure, check out my set-piece analysis here.

Zouma takes the highest positioning and the highest priority zone again, as the headers that depend most on physicality are likely to be found here with floated crosses, while Tomori is next to him. The two full-backs over their side, while Abraham fills in the corner of the six-yard box. This would need revised at the start of next season, and as it stands I’d replace Kovačić with Abraham, as he is unlikely to start.

This structure therefore prevents those back-post occupancy issues, and if players are coached using the coaching points highlighted throughout on how to behave as zonal markers and man markers/blockers, they should have maximal coverage of the box. Chelsea have also struggled from second phase corners at times, and so a more regimented zonal approach allows for the team to push out in a less random shape, as with man-marking the opposition can pin players back to play them onside.

Conclusion

The debate of whether or not to go back to a more zonal approach depends somewhat on coaching and the preference of the coach, but for me I would recommend reverting back to the more zonal approach so long as it is coached properly. The debate of using more man to man or zonal systems is something which I have written around previously, and I for one favour zonal marking because of its more coverage based approach where the shape of the side is not dictated by the opposition. Comparisons using data are difficult between the two systems suggested, as the sample size of eight games for their initial structure is just too small, and so a more qualitative analysis has been completed.

Frank Lampard in recent weeks has bemoaned the lack of height in his side, and although this is a factor in defending corners, their choice to move tactics to a more man-oriented system has only increased the importance of height and physicality in his side. Recruiting a centre back who excels in the air, or perhaps a taller defensive midfielder would allow for more coachable players. Coaching around the behaviours needed in zonal marking would allow less reliance on physical attributes, and would therefore allow Chelsea to solve their current problems if coached effectively, and therefore recruitment may benefit the club in this regard, but whether it is vital is yet to be seen. This analysis has only pointed out weaknesses and stated coaching points and no actual practices have been detailed, as these are something I will share with a club privately if they contact me regarding coaching set-pieces.

Comments