Premier League round 13 began with a clash between Wolves and Chelsea at the Molineux Stadium. Both teams have lost in their previous games, and they were separated by a five-point margin before the game. Despite Olivier Giroud taking the lead for Chelsea, the hosts showed a strong character to come back with a 2-1 victory.

This tactical analysis will dissect some key tactics of Frank Lampard used in this game. Although losing the game, there were positives from the guests, but not by much.

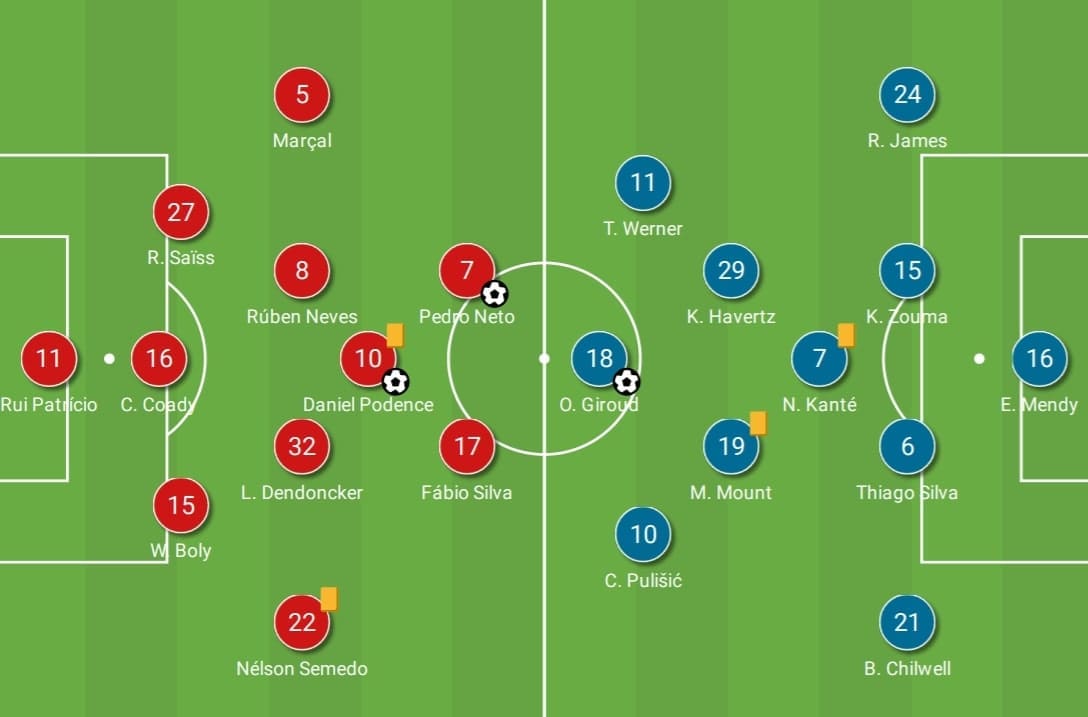

Line-ups

Wolves were without two key players in the last campaign – João Moutinho and Raúl Jiménez. The start of Fábio Silva might have been surprising considering Adama Traoré was left on the bench. The front three slightly tweaked the positionings, from a flattened shape into a 1-2 triangle, with Daniel Podence as the base.

Chelsea were playing with a strong team, but the magical Hakim Ziyech was injured again. Thus, Christian Pulisic and Timo Werner played as the wingers while Kai Harvertz joined Mason Mount at the midfield. Intriguingly, the holding midfielder position role of Jorginho was taken by N’Golo Kanté.

Build-up and ball progression of Chelsea

Lampard’s Chelsea have been trying to play out from the back since the beginning of the campaign. However, without Ziyech to play the concise passes, the first phase lacked dynamics and the development was easily predicted. Instead of playing through the centre, the Blues kept developing the attack from wide spaces, mostly on the left.

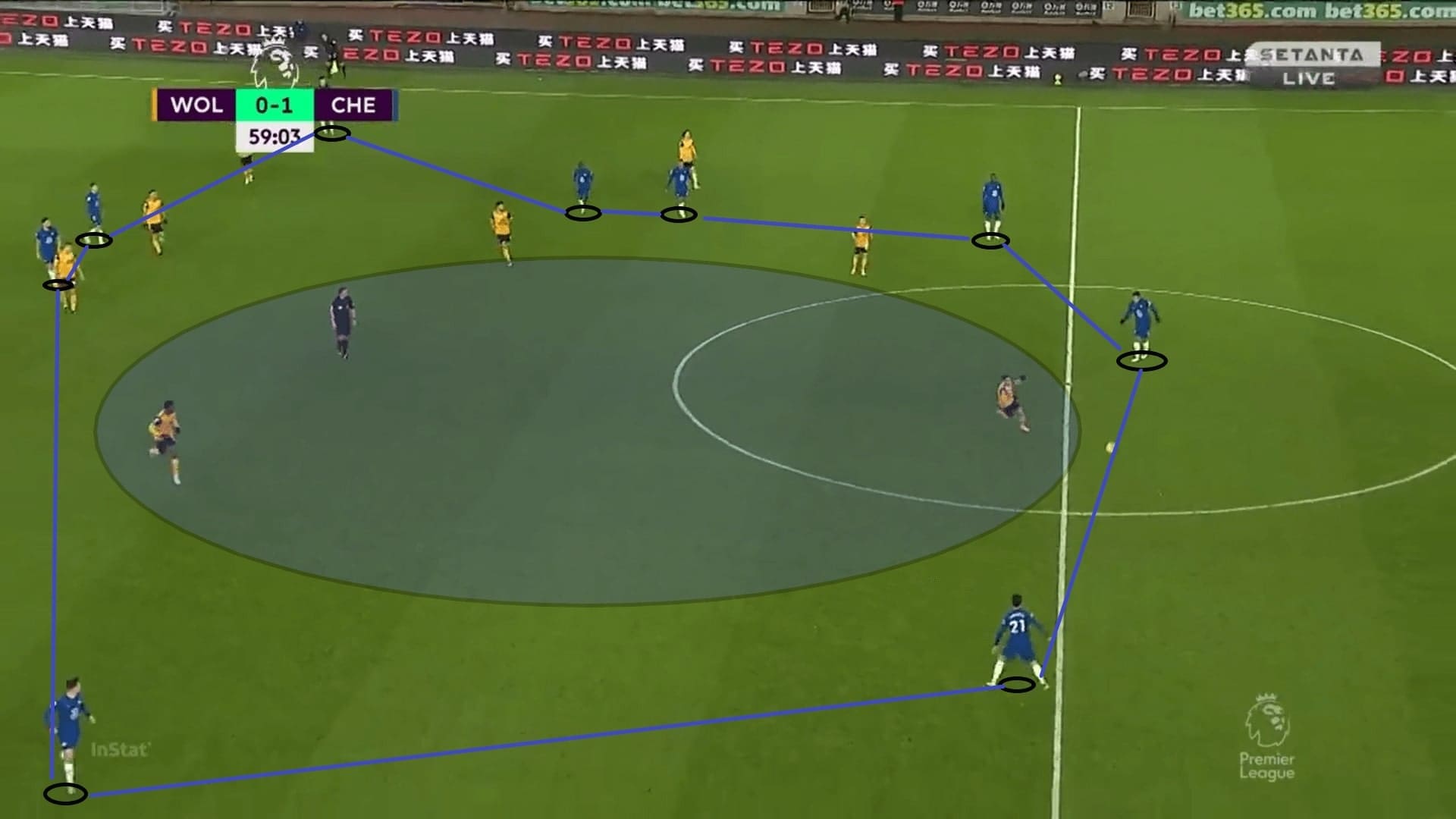

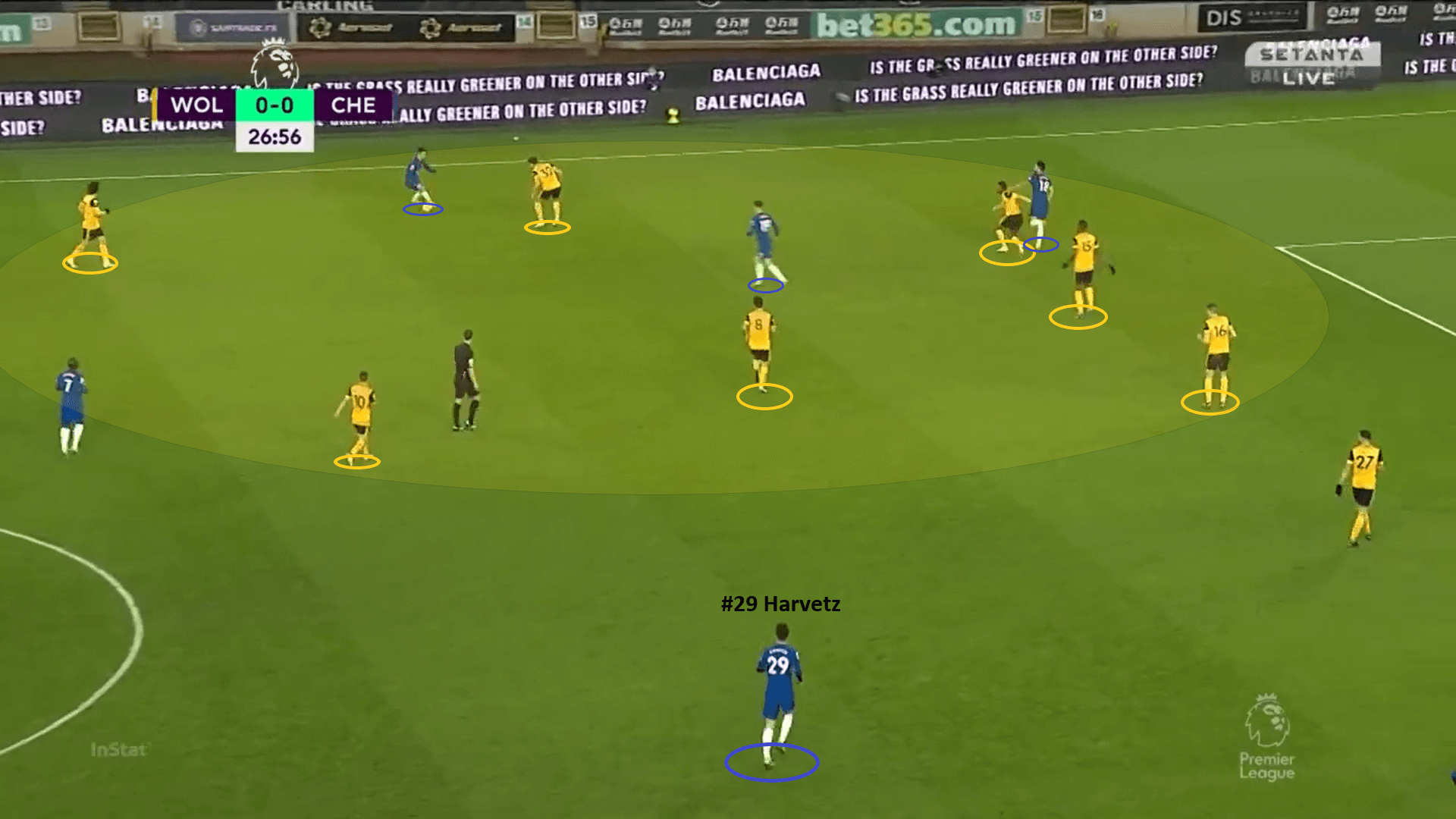

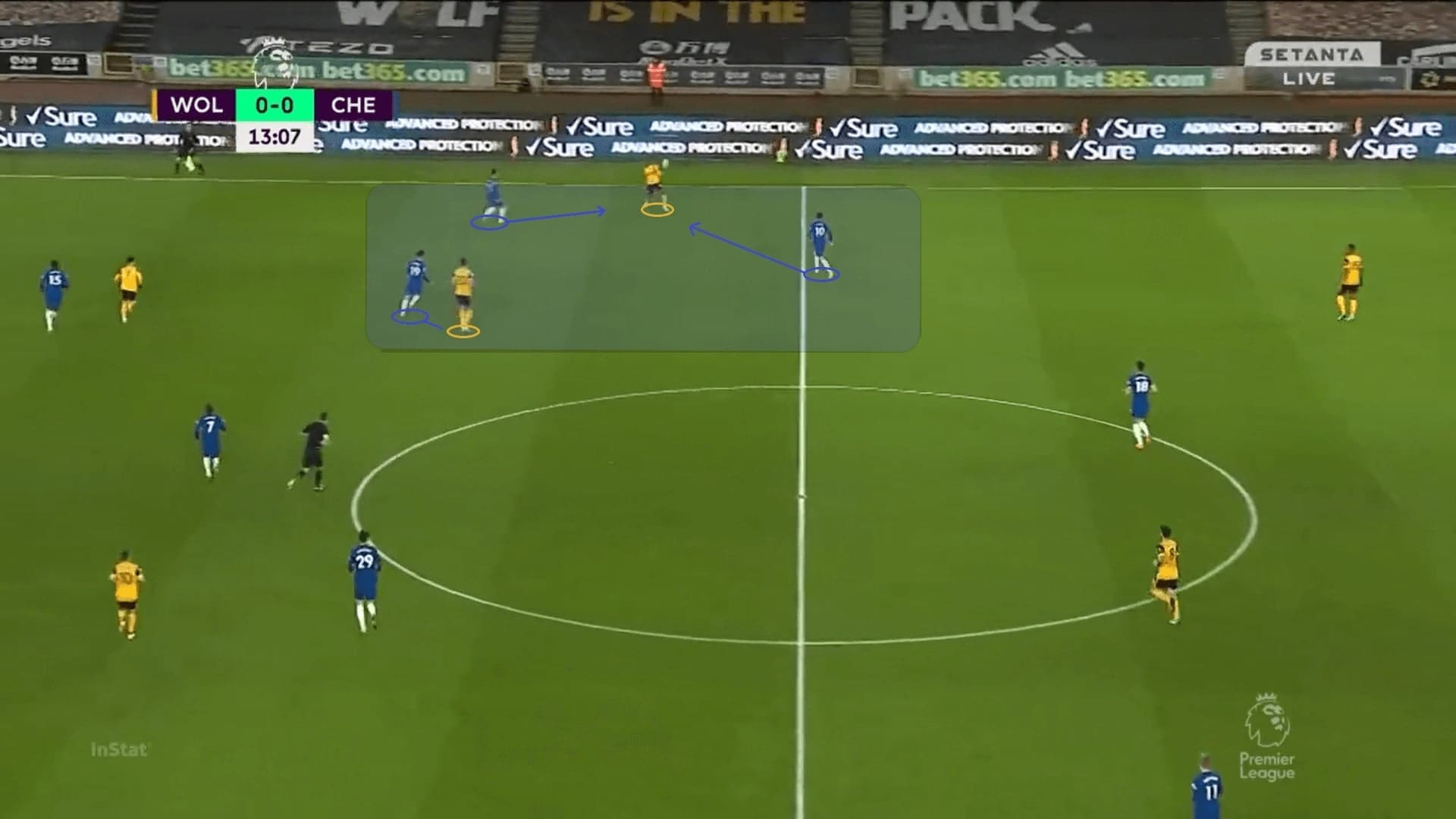

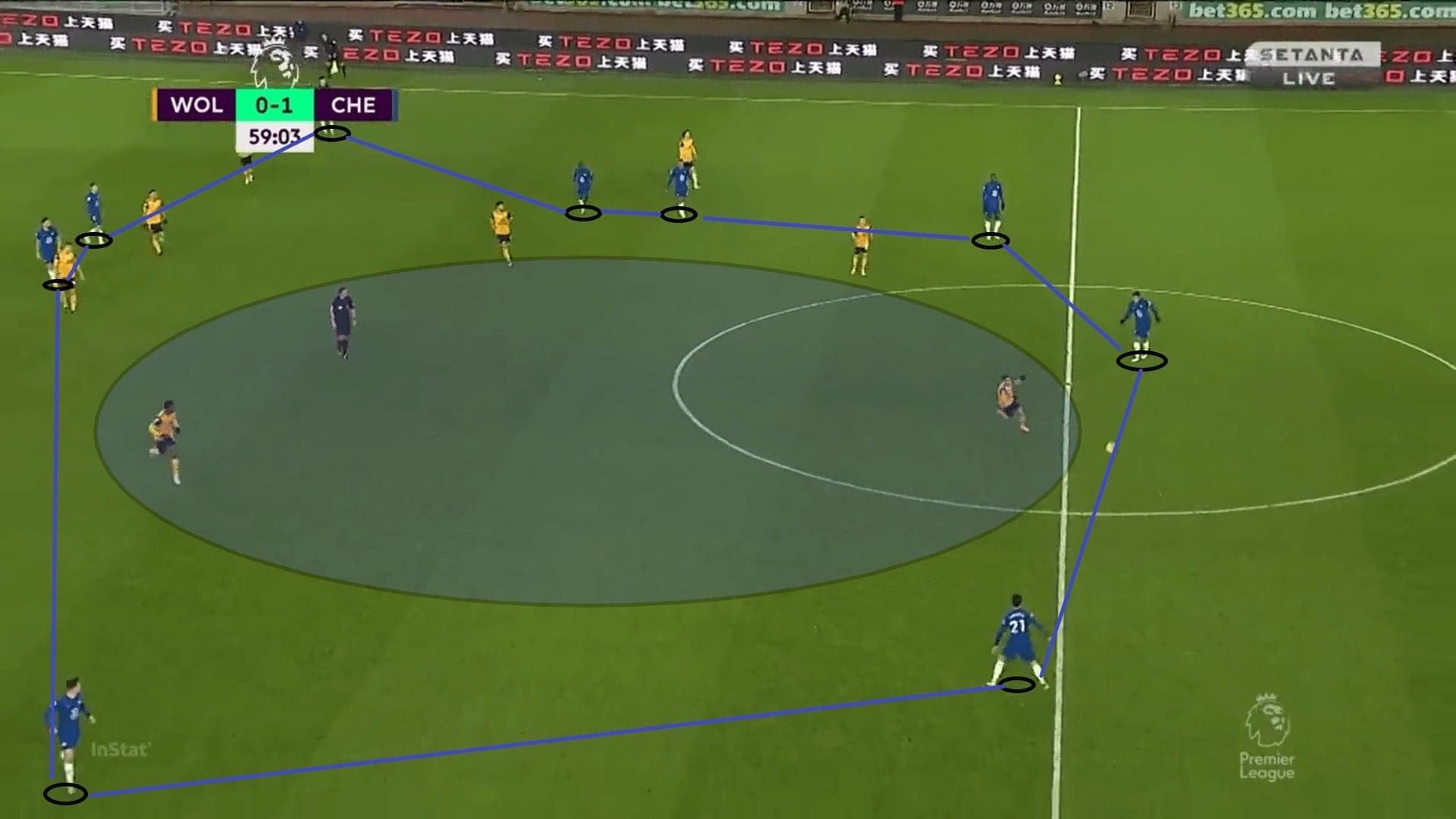

The below image has shown the structural issues of Chelsea clearly – they lost the midfield. The advanced midfielders were instructed to support flanks early, while Kanté offered limited support offensively. On most occasions, we saw the centre-backs struggling to find a vertical option at the centre. Consequently, the attacks of Chelsea were forced sideways. All they could do was to circulate the ball around the defensive block, but not penetrating at the inside.

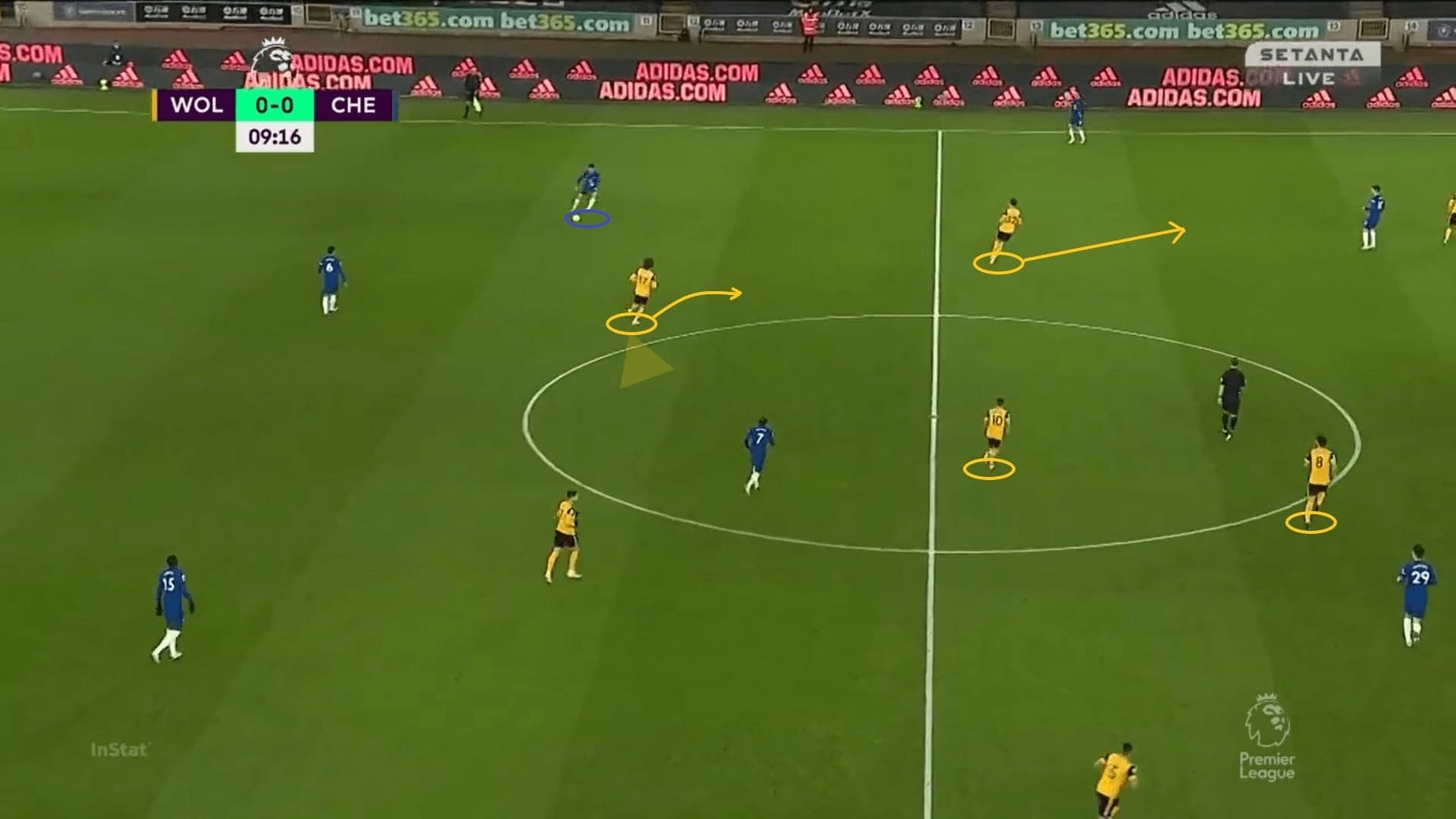

The defence of Wolves was similar to their usual playing style – a medium press plus a midblock, maintaining the defence compactly to support each other. In the first phase, they blocked central access by committing the attacking five at the centre. Specifically, Podence the offensive midfielder was tasked to keep the opposition pivot under control, and the marking was usually tight. When stepping up to press, the top priority for Podence was still to cover Kanté.

The engagement line of defence was deep as Wolves were reluctant to expose spaces behind or within the block. Therefore, they seldom pressed the defenders, allowing Chelsea to progress into the second phase.

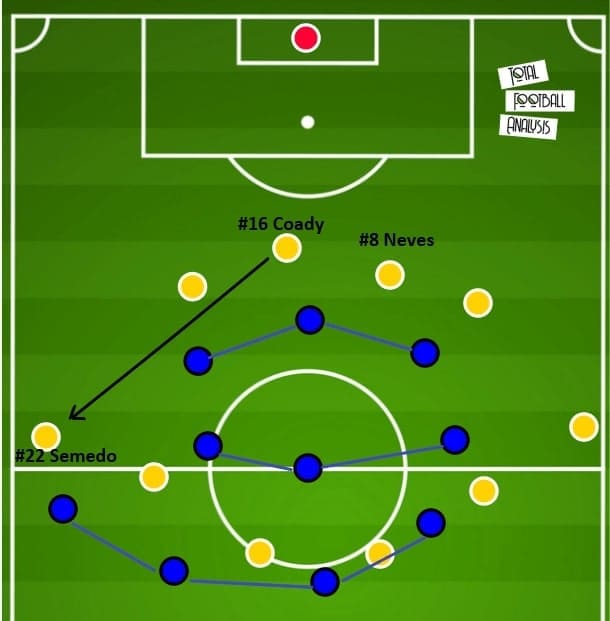

This image shows the defensive shape of Wolves, which was a 5-3-2 block as mentioned in the above analysis. Also, the collective behaviours of players showed a variant of the defence – shifting from man-marking Kanté to zonal coverage.

Here, Leander Dendoncker understood his job – to cover the half-spaces option instead of pressing the ball. Hence the reason that, even when Ben Chilwell received the ball, the Belgian international dropped back instead of pushing forward. Corresponding to his move, Podence and Silva, as a part of the defence, shifted simultaneously to maintain compactness. Through the process, Podence recognised Silva could keep Kanté under the shadow, so he could shift towards Dendoncker.

In fact, even allowing Kanté to receive the ball was not a worrying issue. The French midfielder was good at defending, but lacked the offensive flair to initiate an attack. With the ball, he was more likely to pass sideways instead of penetrating vertically. This shortcoming of the holding midfielder role also hindered Chelsea’s fluidity to combine quickly at the centre.

This example shows a few issues if playing Kanté at this position. Firstly, the awareness to open his body was insufficient, now it was closed, and the angle of turning was large. Everything was slowed down in the process. Secondly, even if he could turn as Podence was yet to access him, the decision was suboptimal. The pair of advanced midfielders were positioning themselves correctly, to offer two diagonal passing lanes for Kanté. If the pass was made to Mount or Harvetz, the Blues broke the lines and faced the back five directly at the centre, where they could generate larger movement.

However, Kanté’s habit to pick a safe option – usually the player in the wide zone, hindered Chelsea’s quality to enter the final third. For example, we can see an instnace of this passing to the left-winger below. The attacks in the final third were mostly wide combinations.

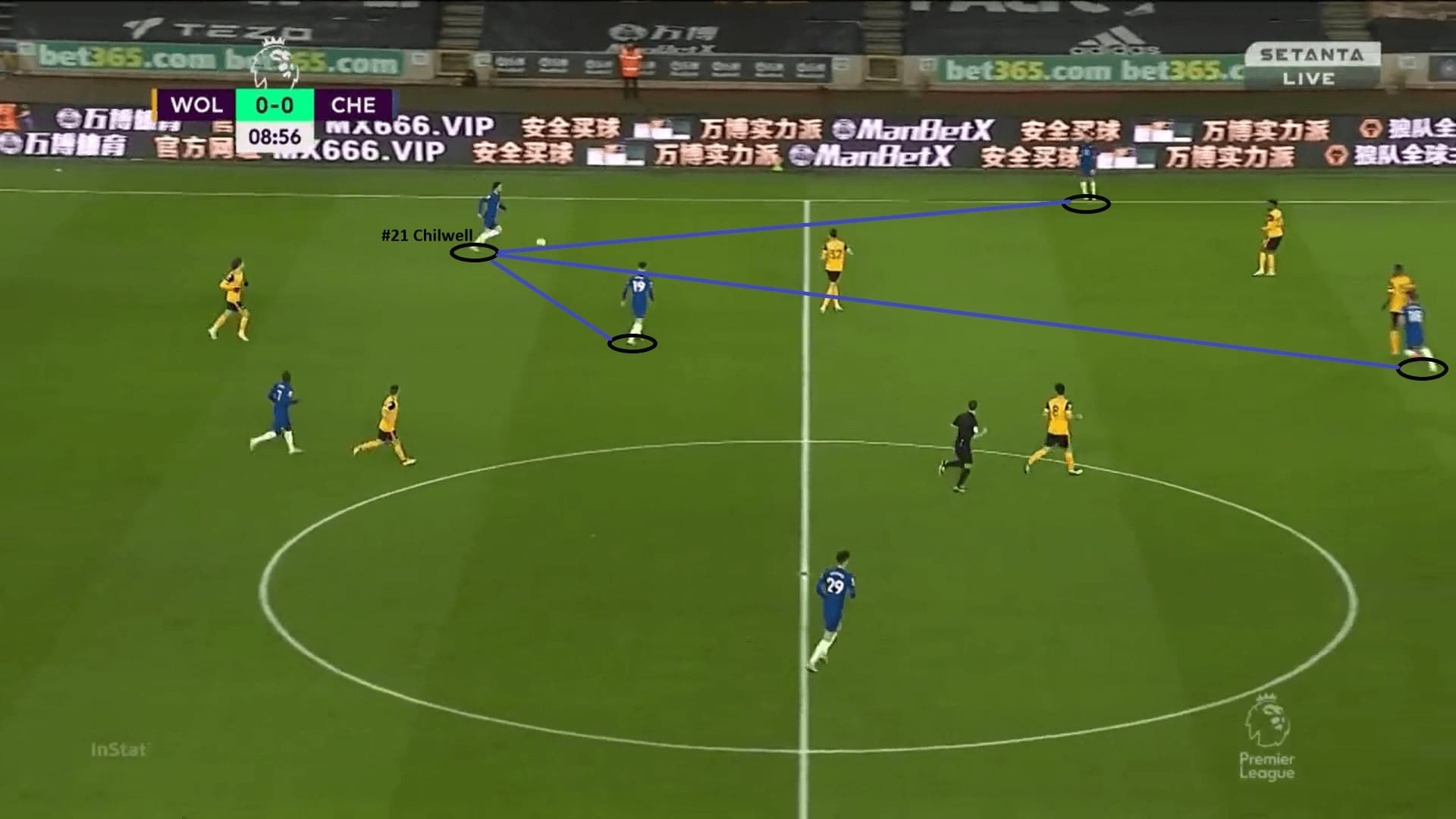

Given the above limitations of Chelsea’s build-up at the centre, Lampard assigned Chilwell as the main progressor in the first phase. The left-back was a bit deeper than the right-back in the first phase, positioning himself at the outside of the Wolves block. The advantage was to create enough spaces for Chilwell to bring the ball forward, over the first or even the second layer of defence. We will then explain the offensive plays of Chelsea in the final third.

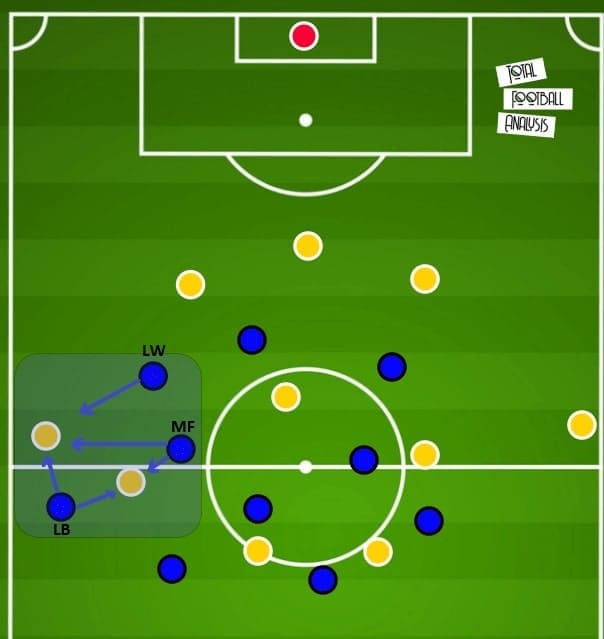

It was a planned tactic of Lampard. To ensure the continuity of the attack, the front players must support the left-back by offering passing options. Usually, the left-winger, striker, and the ball-near midfielder would move to the same flank, offering three options for the ball. As an example, Chilwell had Mount, Pulisic, and Giroud’s support from three different angles.

Battles at flanks in the attacking half

Chelsea planned to attack and tried overloading the left flank in this game. Intriguingly, the defensive scheme of Wolves also emphasises on the wide overload to compress spaces and regain possession. So, how the teams would counter-act against each other was the key theme in this zone.

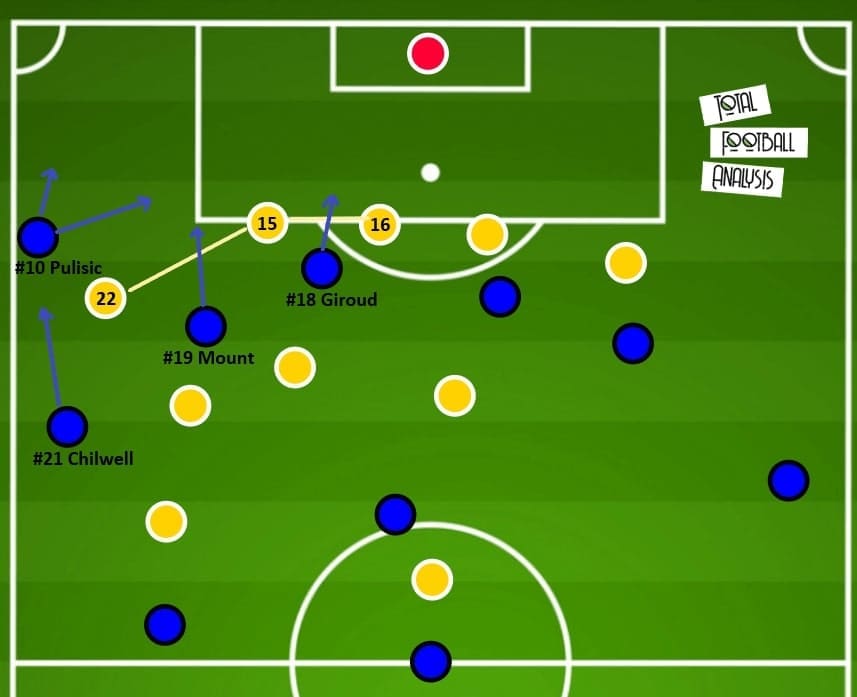

Lampard’s Chelsea prepared to attack the left, as explained, beginning from Chilwell’s ball progression. There were a few key principles to note in this phase

- Formation of the passing triangle

- Giroud to attack spaces between Willy Boly and Conor Coady

- Constant searching for attacking depth into zone 16

- Keep moving the ball to stress the opponents

- Using rotation to create a free player if needed

This board shows the positionings of the Chelsea players at this flank. Pulisic, Chilwell, and Mount could form the passing triangle. Giroud could have occupied both centre-backs, manipulating Boly to stay at the centre. When the opposition right wing-back was dragged wide, the gap was opened at the relative half-spaces for Mount to attack. The objective was to whip in some crosses.

In addition, Chilwell generated 13 crosses out of 32 Chelsea crosses, accumulated a 0.53 xA and an assist. His runs up and down, as well as his offensive outputs at this flank, were vital to the Blues.

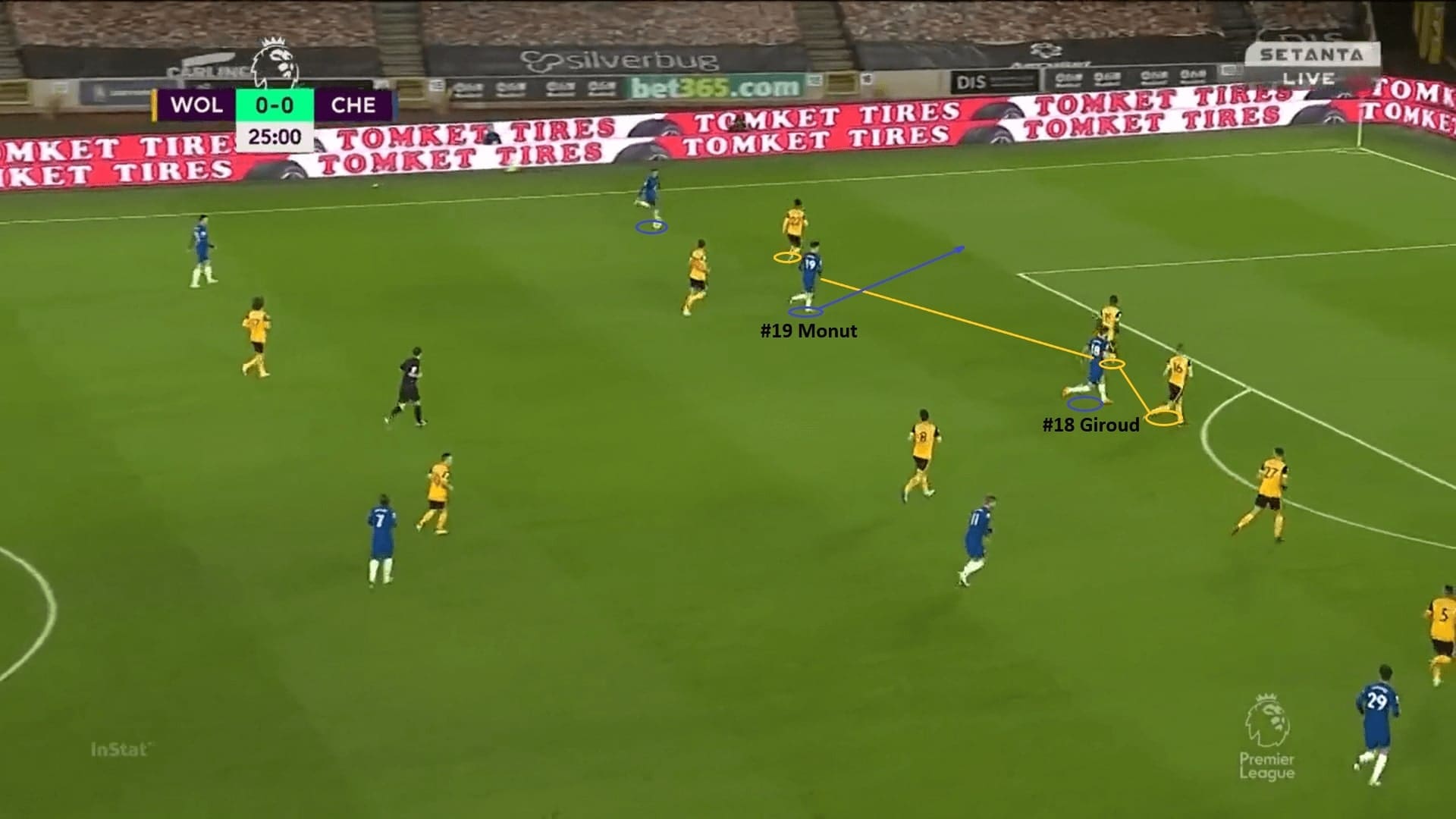

This image shows the key features of Chelsea’s attack as explained above. Giroud to kept Boly and Coady tight at the centre to open the relative gap at half-spaces. Pulisic out wide, overloaded the right wing-back’s zone in a 2 v 1 with Mount. This was a bit difficult for Rúben Semedo to defend – all he could do was rely on another teammate to help. Therefore, the wide player was allowed to keep the ball to dribble or play the release pass.

This was another reason why the tactics to attack this flank was wise. Usually, Boly could provide the defensive cover for Semedo all the time. However, in this game, he had to be more cautious to deal with Giroud. The habit and practices of Wolves were disrupted because of Chelsea’s set-up.

The function of Giroud was more than a traditional target man. Instead, he was free to support around the ball or use his positioning to manipulate the defence. We saw the widest player search for attacking depth, while Giroud dropped slightly deeper, which had the following benefits. Firstly, it would pull the centre-back out of position, and secondly, it would create a passing option for the ball.

These elements attributed to the goal for the Frenchman as well. When attacking Chilwell’s cross, he was not staying at the same line with the central defenders to break the offside trap. Instead, he was a few steps backwards to generate enough distance to sprint, and enough space to attack the ball.

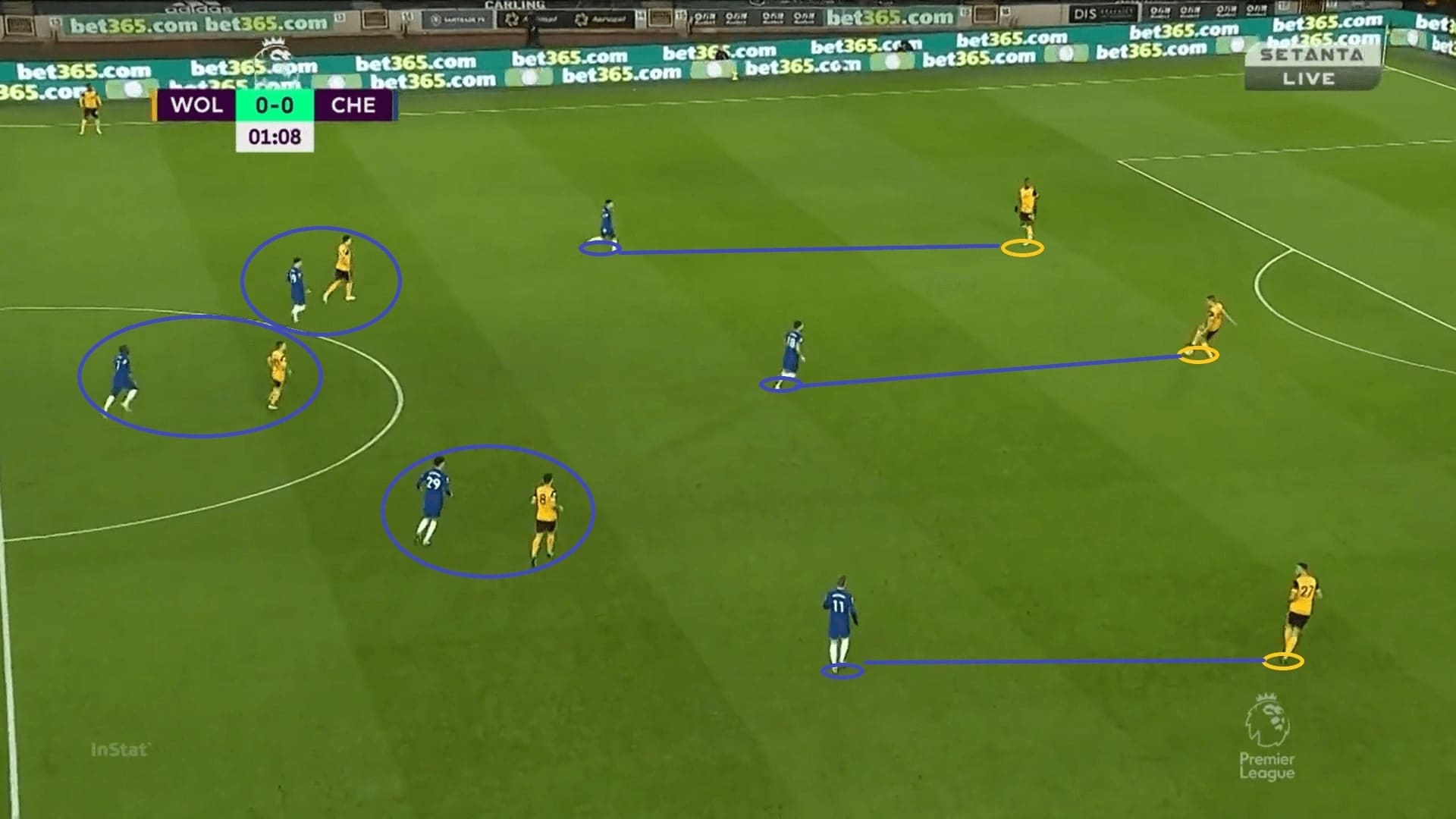

Despite all the efforts to attack this flank, Chelsea were not able to create a lot of big opportunities as Wolves were well-prepared to defend that area. We explained how Wolves defended in the midfield area and moved collectively to invite the wide passes. Usually, they were rewarded with a numerical advantage on this flank – instead of Chelsea’s superiority in numbers.

At least the ball-near midfielder plus Rúben Neves joined the defence on this flank, while one of the forwards would drop behind of Chilwell. In the meantime, the entire defensive line also shifted to reduce horizontal spacing – it turned out to be a 7 v 3 numerical advantage of the hosts. Chelsea sometimes were forced to play in tight areas and inaccurate passes could occur.

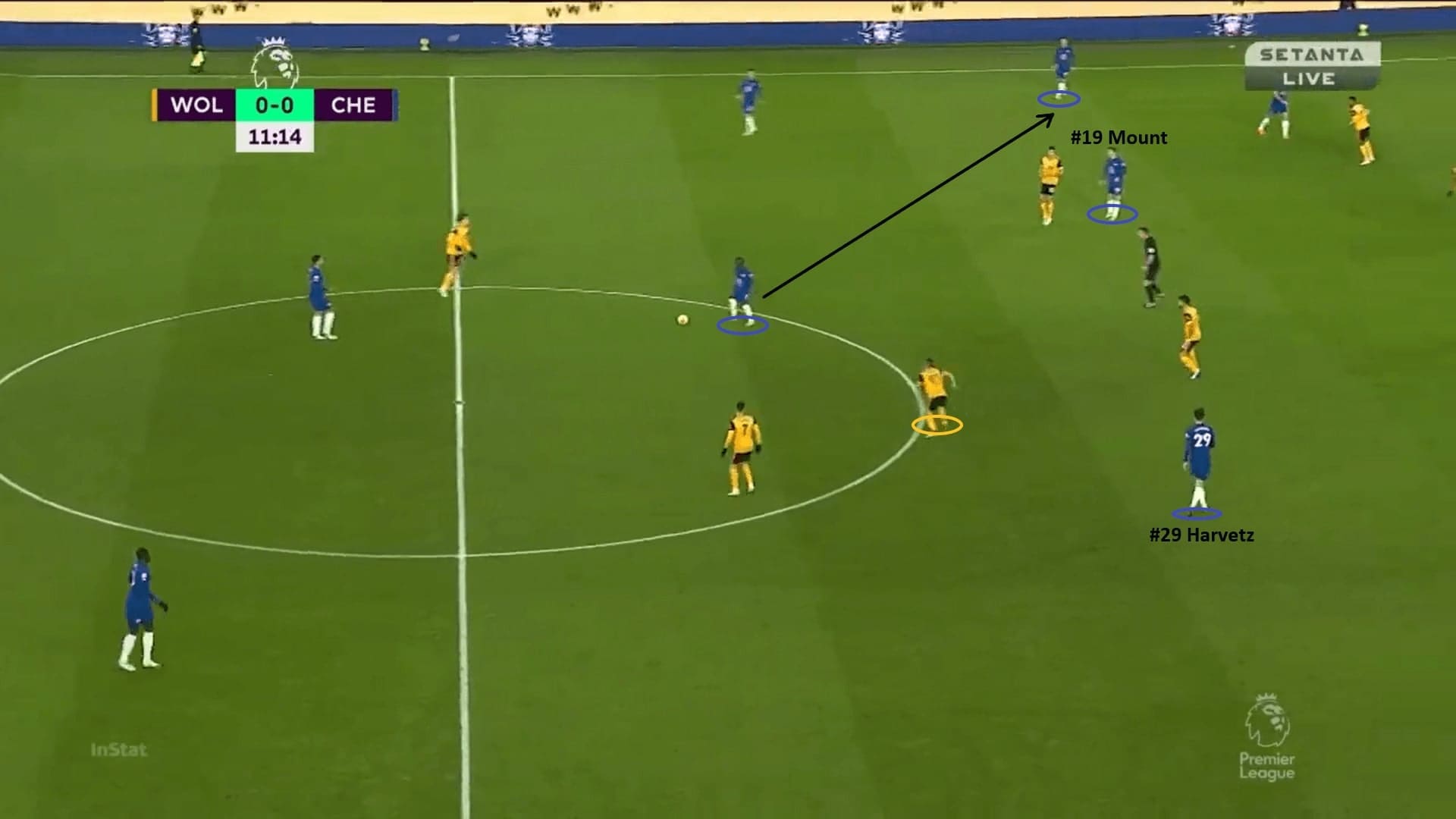

This was also part of the problem for Chelsea – they could not get Harvetz involved in this game. When Lampard designed the tactics to attack the left flank, the €80m new signing had no freedom to roam his position. He merely provided the offensive heights on the far side when Giroud left the height position. For example, in this image, Harvetz was isolated at the bottom and it would be difficult to get him on the ball.

It seemed Nuno Espírito Santo also found a better solution after the break. Since Dendoncker was injured, Owen Ostasowie played at that right midfielder position in the second 45. The American youngster did well to commit himself defensively – did not press the ball even when Chilwell was moving forward. Instead, covering spaces were the top priority.

When Wolves tried to exploit the exposed defence of the Blues in the counter-attack, some offensive players were left high to trigger the opportunities. Chelsea had more positional and transitional moments to attack the flank, so Wolves needed to prepare for this scenario.

Here, you could see Ostasowie was not going to press Chilwell. All Nuno wanted was to cover the half-spaces to stop the release pass. Meanwhile, because of the extra physicality and defensive support added by the youngster, Semedo knew he could jump onto the winger and press Werner earlier.

Chelsea prepared a defensive trap

Defensively, Lampard also studied his opponents and prepared a trap. However, we could hardly categorise it as a pressing trap as the Blues only had to passively for those moments, instead of actively guiding Wolves into the trap by their actions.

When pressing high, Chelsea had enough numbers to man-mark the players at the centre. Here, the front three attached the centre-back, while the midfield trio can man-mark Podence, Neves, and Dendoncker.

But Chelsea seldom engaged the backline in this game, even Neves dropping to the defence would not pull Giroud out of position. Instead, the Blues wished to stay in a 4-3-3 shape that the midfielder and wingers stay in two horizontal zones. Also, the markings on the wide centre-backs were loose, as the wingers stayed slightly deeper to have better access to the wing-backs.

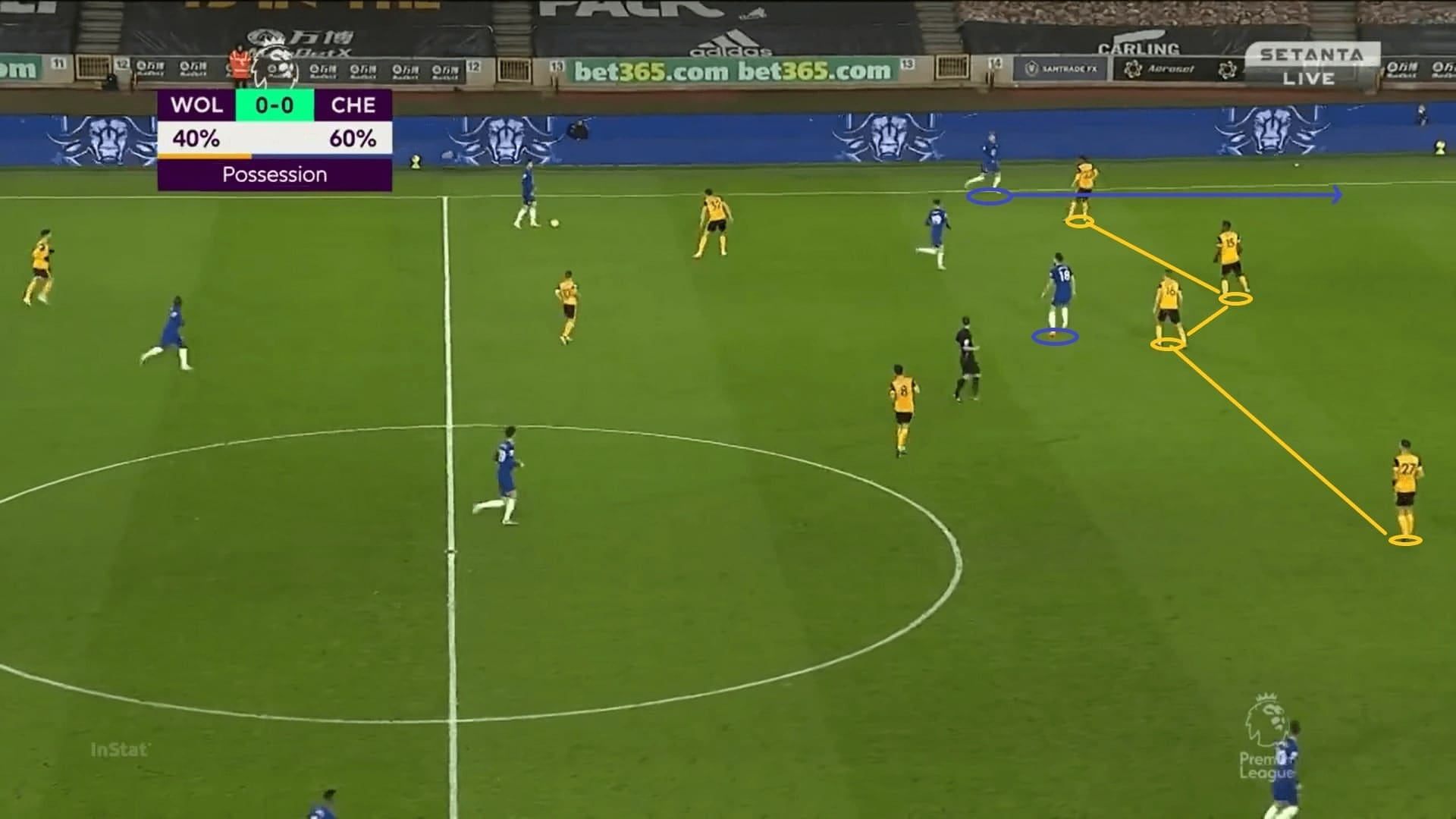

The tactic board below shows the defensive scheme of Chelsea – 4-3-3 with a flexible backline that shifts to the ball flank. Meanwhile, Wolves also used their common offensive pattern – the diagonal lofted balls of Coady to reach the right wing-back. This was a well-predicted behaviour and Lampard tried to counter this.

Here, when the ball was passed to the right wing-back, this board shows the situation. This was a trigger to the Blues as the winger, midfielder, and the full-back should move towards the zone quickly.

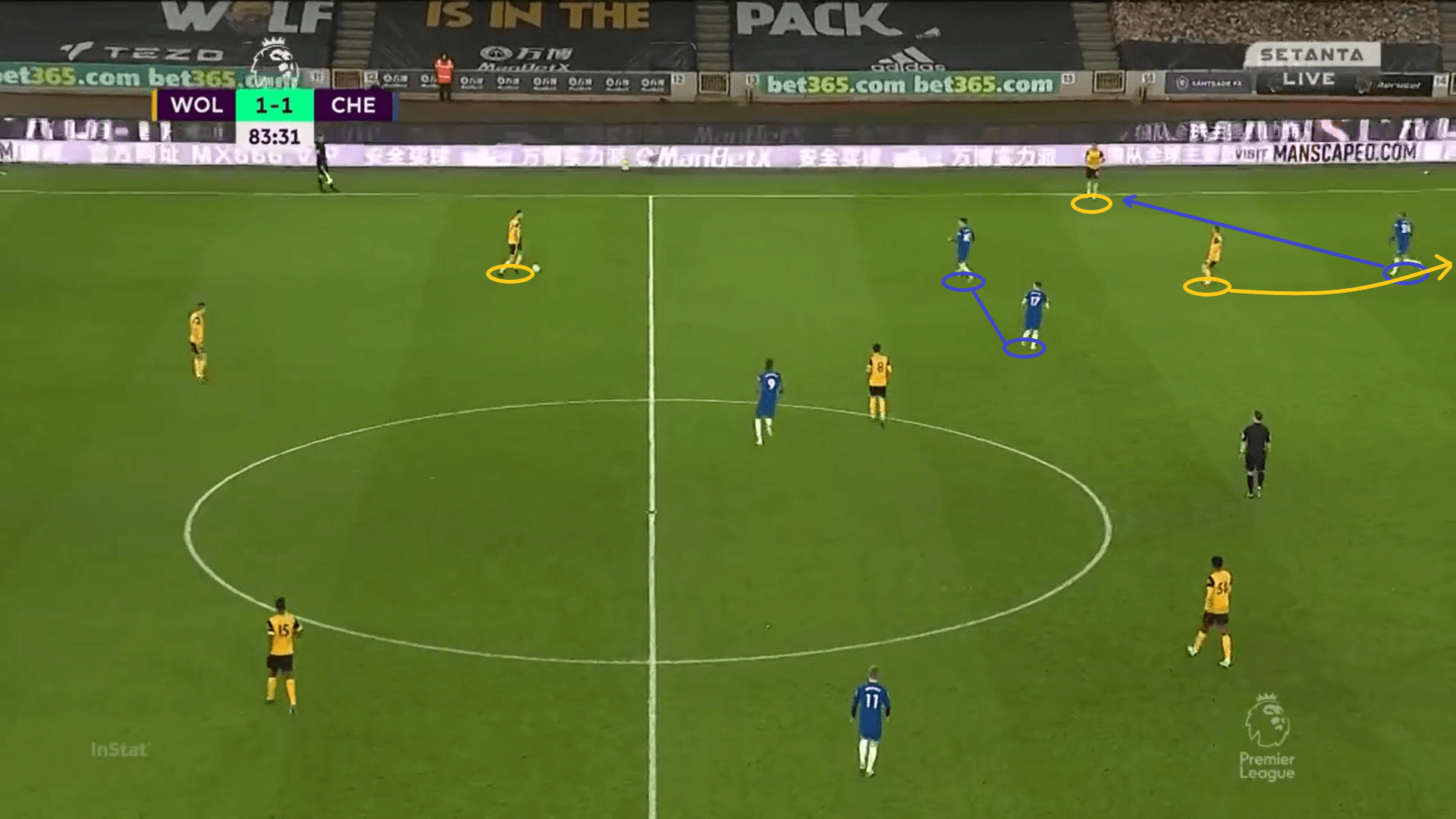

The winger could cut the return passing lane and press from the wing-backs’ back. The midfielder could press the ball while covering the midfielder, for example, Neves. Meanwhile, Chilwell could flexibly pick either target in the zone to attack him. In this tight area, Chelsea enjoyed a 3 v 2 numerical advantage, so the only way for Wolves to get out was through the dribbling of Semedo.

Here are some in-game examples that further demonstrate the situations. As framed, there is a 3 v 2 numerical superiority in the zone. They could spare two players to attack Semedo while using Mount to cover the supportive Dendoncker.

Eventually, under the pressure from two angles, the pass from Semedo to Dendoncker was intercepted by Mount.

Since the passes were lofted from Coady, it took more time for Semedo to read the dropping point. As such, he had to keep his sight on the air until the last moment, unable to check his surroundings. It was also more difficult to control a dropping ball than ground passes, especially when the available spaces were limited by the pressing player.

Another example here was the lofted pass from Coady, where the ball was in the air. At that moment, the Chelsea players were triggered to press Semedo – we saw Werner, Mount, and Chilwell entering the zone to attack the target. Wolves were struggling to enter the final third effectively, let alone create high-quality chances in open plays.

The issue for Chelsea after Podence levelled things up was the execution of the game plan. The Blues were shaken, spacing and positionings, as well as the timing to press, were all suboptimal. Wolves found it easier to bypass the block and enter the final third.

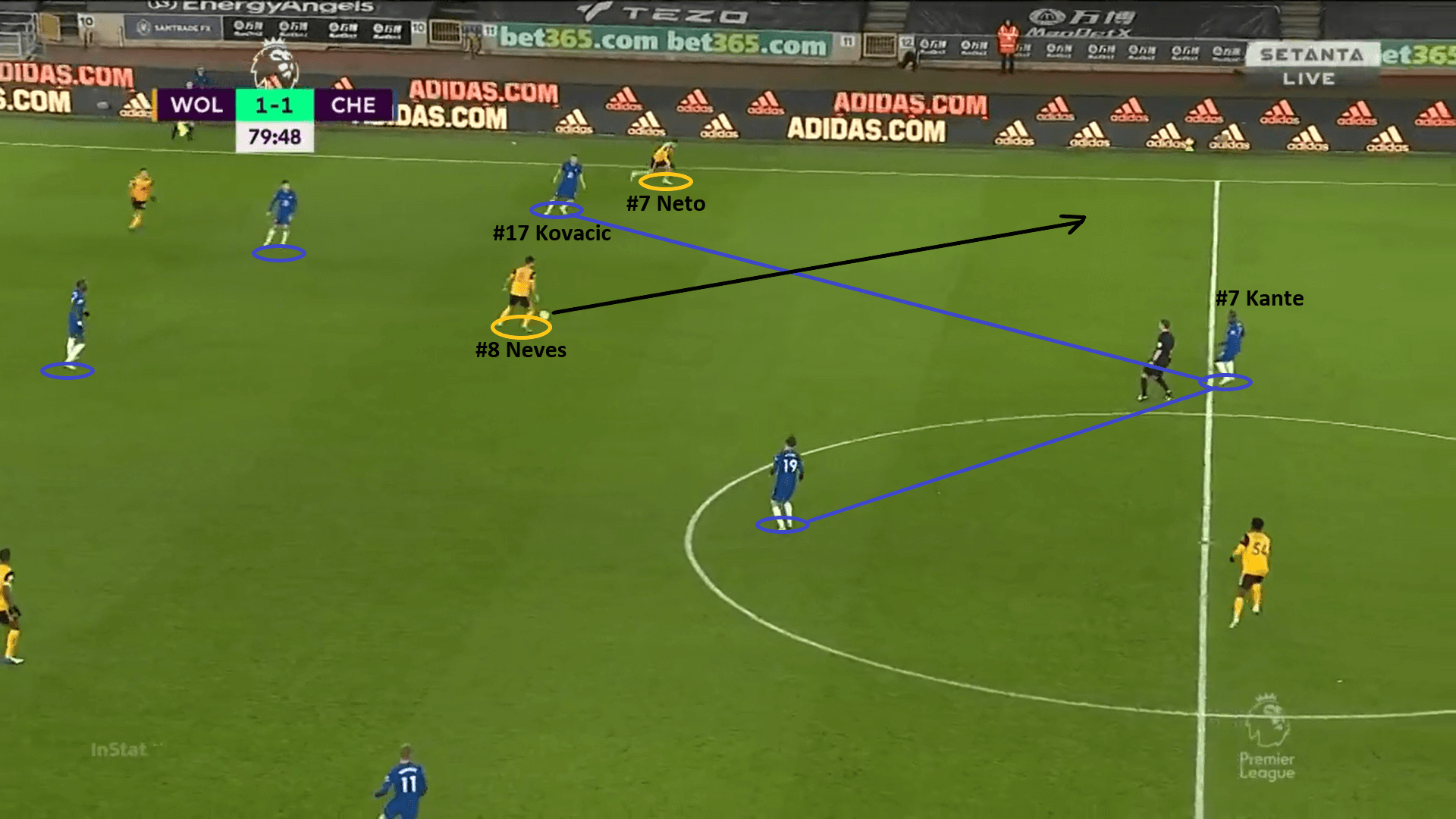

The example below shows a result of Mateo Kovačić leaving his position to man-mark Pedro Neto. It was fine if he stuck to Neto tightly, tracking his run back to the Blues’ half. However, the Croatian midfielder was caught ball-watching, his eyes on Neves instead of paying attention to Neto. When he realised the pass was going back to his side, it was too late to begin his run already as Neto was miles away already.

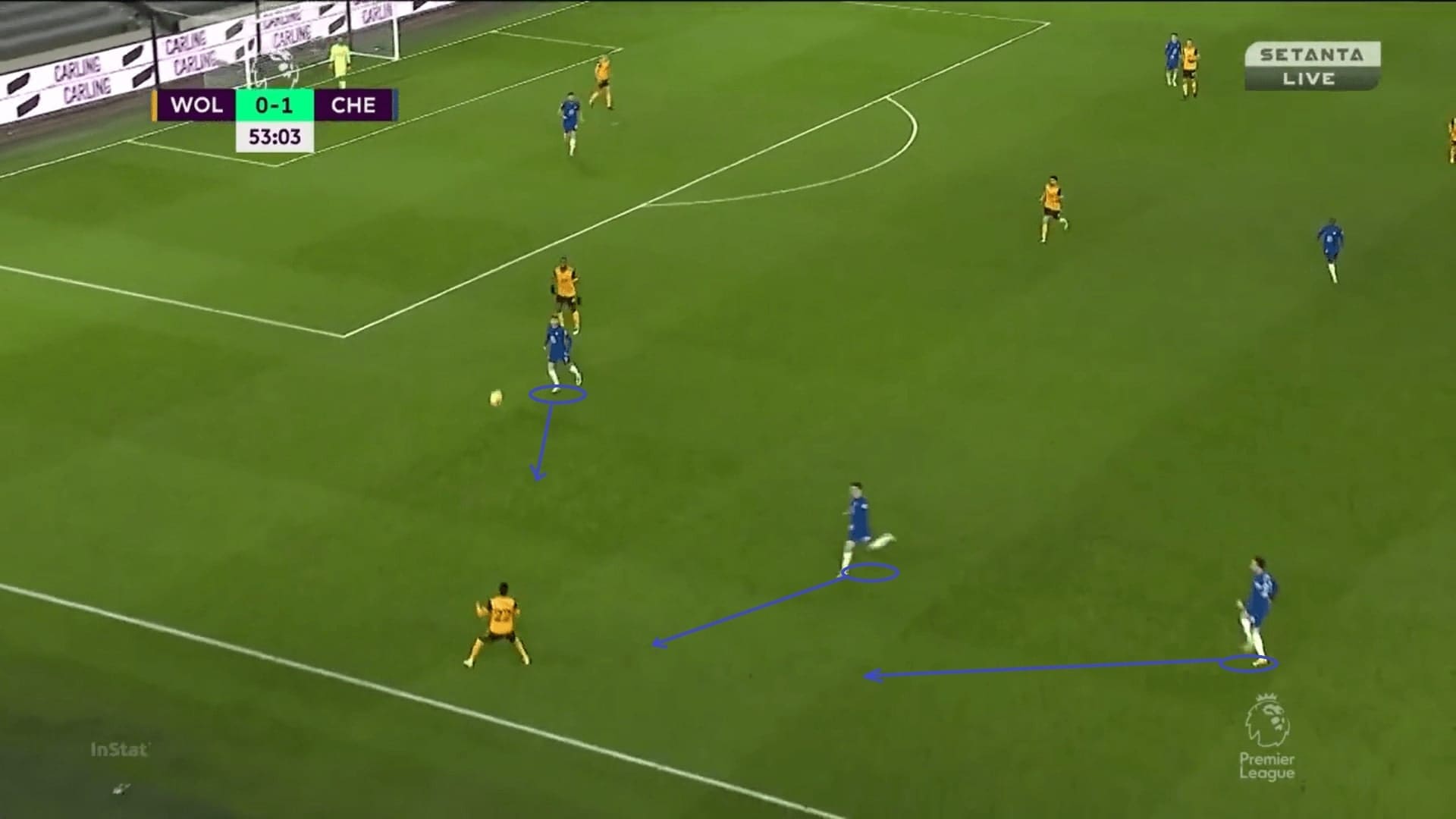

The collapse of the press could also be attributed to the timing to engage the defence. Tammy Abraham led the Chelsea line to press Wolves too early, leaving spaces and being unable to cover Neves at his back. Meanwhile, Kanté was staying much deeper than he did in the first half. The man-oriented midfield was torn apart, as we can see how large the spacing was.

There was another example of the defensive issue here. Kovačić might not have fully understood the game plan and made several defensive errors in the 19 minutes of playing time. Firstly, Pulisic and Kovačić stayed on the same horizontal zone, while the problem would be the loose control of the half-spaces.

When Wolves moved the ball to the wide player, Reece James stepped up to press him – a correct decision. However, Kovačić was way too slow to track Podence, allowing the target to be released in the offensive third.

Counter-attacking opportunities

When Chelsea attacked with numbers, the full-backs were likely to push high on the pitch. As the game developed, Wolves were able to exploit this set-up to create some goal threats, and this was how Neto scored the winner.

The key to covert the offensive transitions into counter-attacks was the spaces behind the full-backs. When Chilwell and James joined the attack, Wolves looked to immediately put the ball at their back to trigger a counter-attack. If the first pass was not possible due to a covering player or limited angle to pass, the host would look for Neves at the centre. The Portuguese international could switch the ball from one vertical half to another, releasing the runners to hit the underloaded flank. To find Neves, it was vital for the initial passer to make the forward runs after a pass, so the Blues would retreat deeper, opening a central passing lane.

Nevertheless, the opportunities for Wolves were limited, and Chelsea might have survived if Édouard Mendy did a better job in the second goal. The goalkeeper positioned himself too high in this case, so it was difficult to save Neto’s shot. He should have stayed deeper in the six-yard box, and the chances to save the shot would have been higher.

Final remarks

This analysis explained the details of the game from a tactical standpoint. Although Chelsea lost the game, some arrangements made more sense than those earlier this season. However, if Lampard had clearer principles of plays, plus with more careful planning and counter-strategies against the opponent, the Blues could have done a lot better.

Despite the positives mentioned in this analysis, there were some worrying issues that required solutions in the future. For example, how to allow Harvetz to perform by himself? Currently, the former Bayer Leverkusen attacker was deployed nearer the wide zone, lacked the flexibility to roam positions. The restricted role had adversely impacted his creative movements in the final third. Also, would Chelsea try to play through the centre in the future?

Although this was not a perfect display from Wolves, the result was extremely crucial to boost the morale of the squad. They were still undergoing a transition period under Nuno as the Portuguese head coach was trying to adapt without several key players in the past. At least it seems as though they have got an appropriate replacement for Diogo Jota already, while Neto also looked sharp as well.

Comments