Leicester City hosted Wolverhampton Wanderers last Sunday. The recent history of both teams’ meeting was slightly in favour of the visitors. Per the statistics, the last time Leicester won against Wolves in the Premier League was back in August 2018; while Wolves came victorious in January 2019.

However, it’s the home side who managed to win last weekend’s encounter. Thanks to Jamie Vardy’s penalty goal, Leicester now have six consecutive wins in all competitions. It’s not just that, though. This result also means that they will top the table until the league returns in about a fortnight. Without further ado, this tactical analysis will examine how the match unfolded.

Lineups

On paper, it seems that Brendan Rodgers chose 5–4–1 as his team’s main shape. But, the actual structure of Leicester was closer to 3–4–3/3–4–2–1, especially because they enjoyed more possession up until the 75th minute. In this system, the trio of Wesley Fofana, Jonny Evans, and Christian Fuchs was chosen to play at the heart of the defence. Up top, marksman Vardy was supported by Dennis Praet and James Maddison next to him. Leicester’s bench was filled with names like Wes Morgan, Marc Albrighton, and Harvey Barnes.

In the opposite side, Nuno Espírito Santo opted for 3–4–3. Nélson Semedo and former Ligue 1 player, Rayan Aït-Nouri, were trusted to play as the wing-back pairing after a convincing win against Crystal Palace in the previous game week. The attacking line then was filled by the trio of Pedro Neto, Raúl Jiménez, and Daniel Podence. Names like Fernando Marçal, Fábio Silva, and ex-Barcelona player Adama Traoré had to start the game from the bench.

Cautious approach from the visitors

This analysis will start by examining Wolves’ defensive tactics. As usual, Nuno preferred his team to be the more passive side on the ball and would try to hurt the opponent in transitions. To do so, he instructed his men to defend in a medium-block 5–2–3 with the focus to congest the central spaces. This shape would swiftly change to 5–4–1 when Wolves were defending deeper.

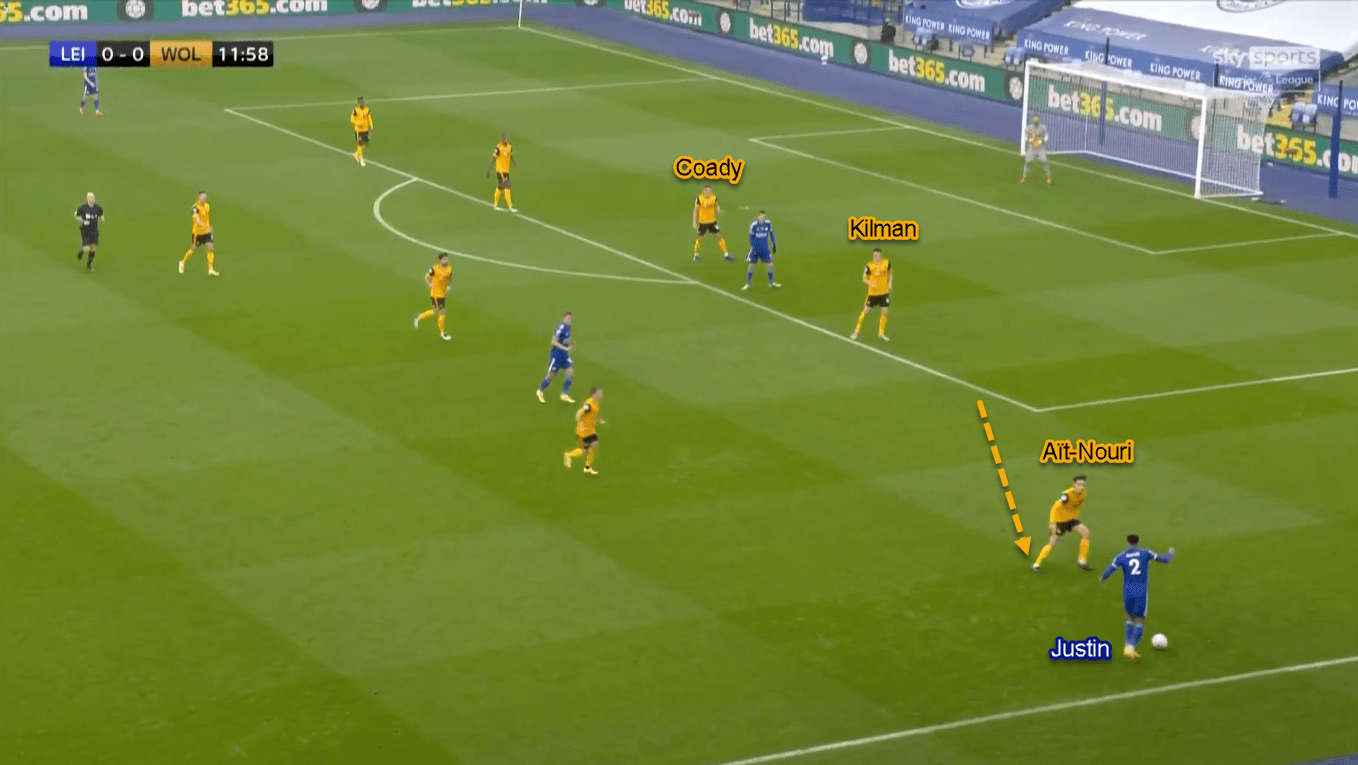

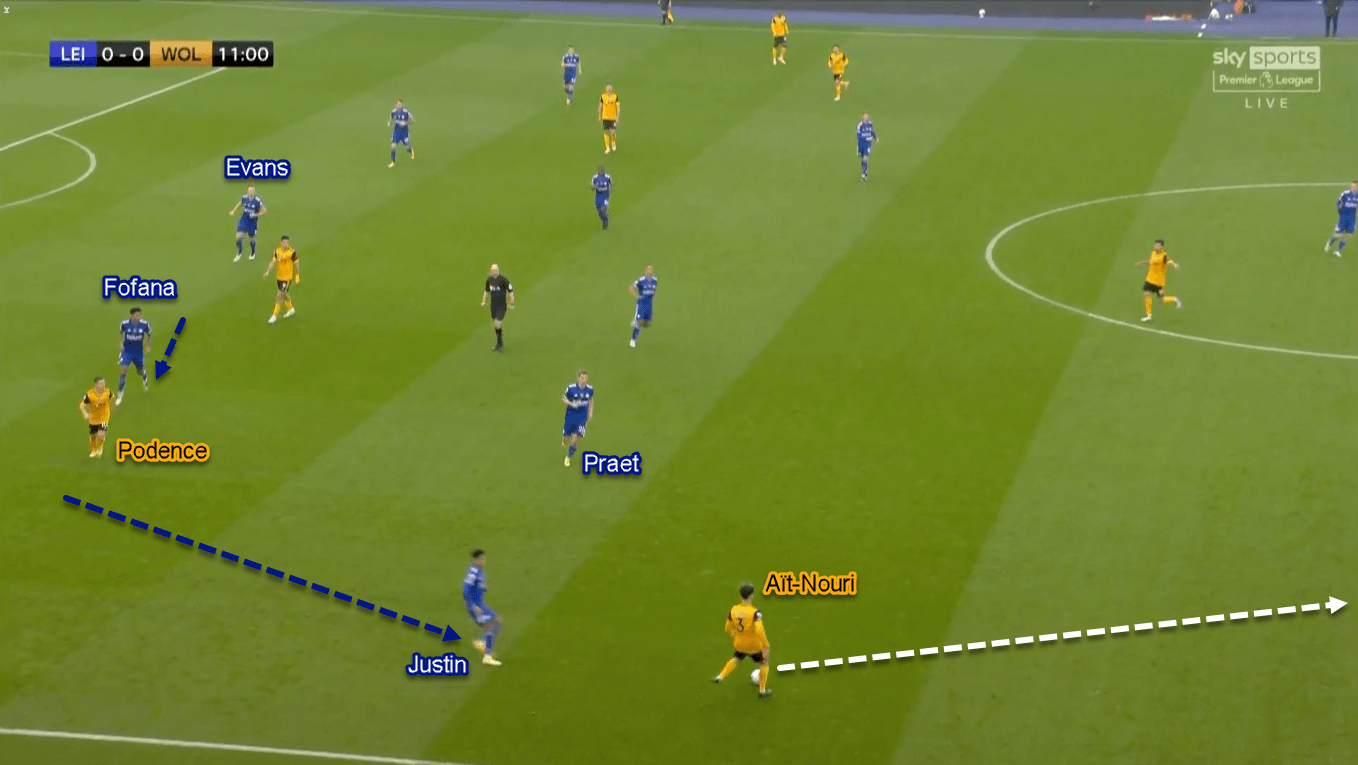

Their focus to close the central lanes forced Leicester to attack through the flanks. The Wanderers would counter the flank-play by sending their ball-side wing-back to step out from the backline and press Leicester’s player in the wide area. When doing so, either Semedo or Aït-Nouri would quickly press the opponent as well as limiting his time and space with the ball.

One interesting thing in this flank defence was Nuno’s instruction to keep his centre-back trio close to each other. It means that the outside centre-backs (namely Willy Boly and Kilman) would stay within the backline instead of coming nearby the wing-back and providing cover for him. This instruction was probably to help Wolves congest the penalty box should Leicester try to find Vardy with crosses.

Leicester’s attacking tactics

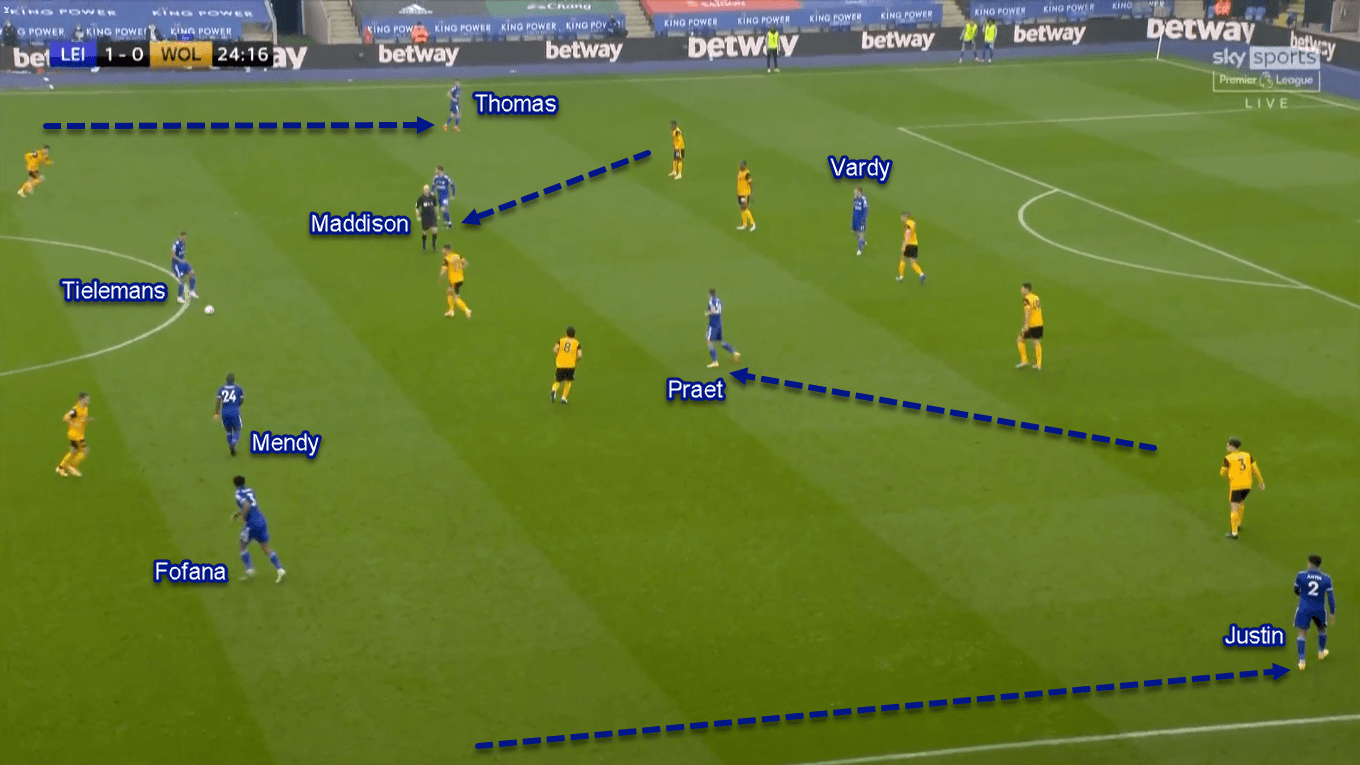

As mentioned previously, Leicester would use 3–4–3/3–4–2–1 when they had the ball. In this structure, Rodgers asked both wing-backs to bomb forward, even up to the forward line. The objective behind that was to allow them to be Leicester’s main attacking outlets in the wide areas.

Upfront, talisman Vardy was tasked to play in the shoulders of Wolves’ centre-backs. It means that he would pin the backline instead of dropping from his designated position. Vardy’s positioning was also important to stretch Wolves’ defensive block. This means the centre-backs couldn’t risk having a more aggressive defensive line because Vardy has a speed advantage over the trio.

Another advantage of the talisman’s positioning was to open more space in between the lines. This space was then occupied by both Maddison and Praet, who also tucked themselves to play inside the half-spaces. Interestingly, the duo had different tasks, as follow:

First, Maddison. The Englishman was instructed to orchestrate the attacks before the ball went into the final third. If we look at the stats, Maddison finished the game with four (80%) accurate passes into the final third; compared to Praet’s one.

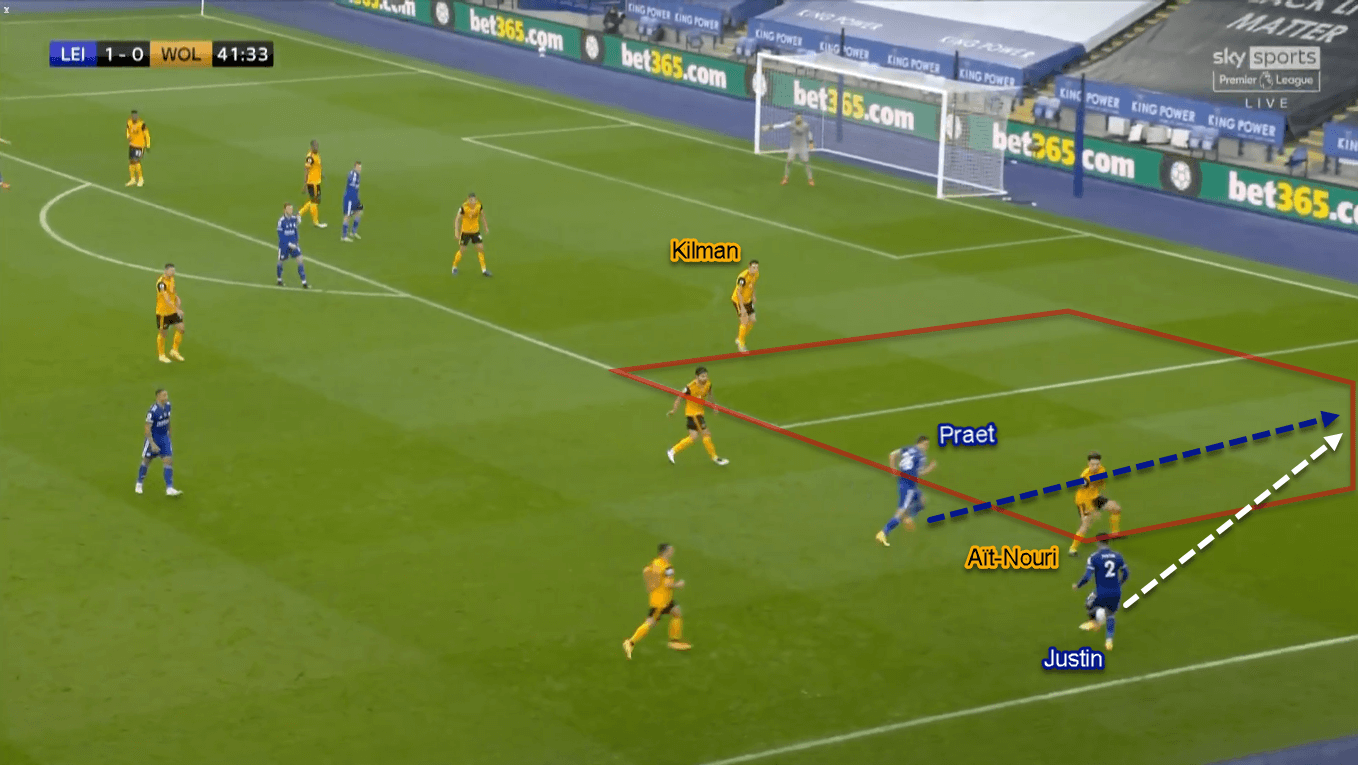

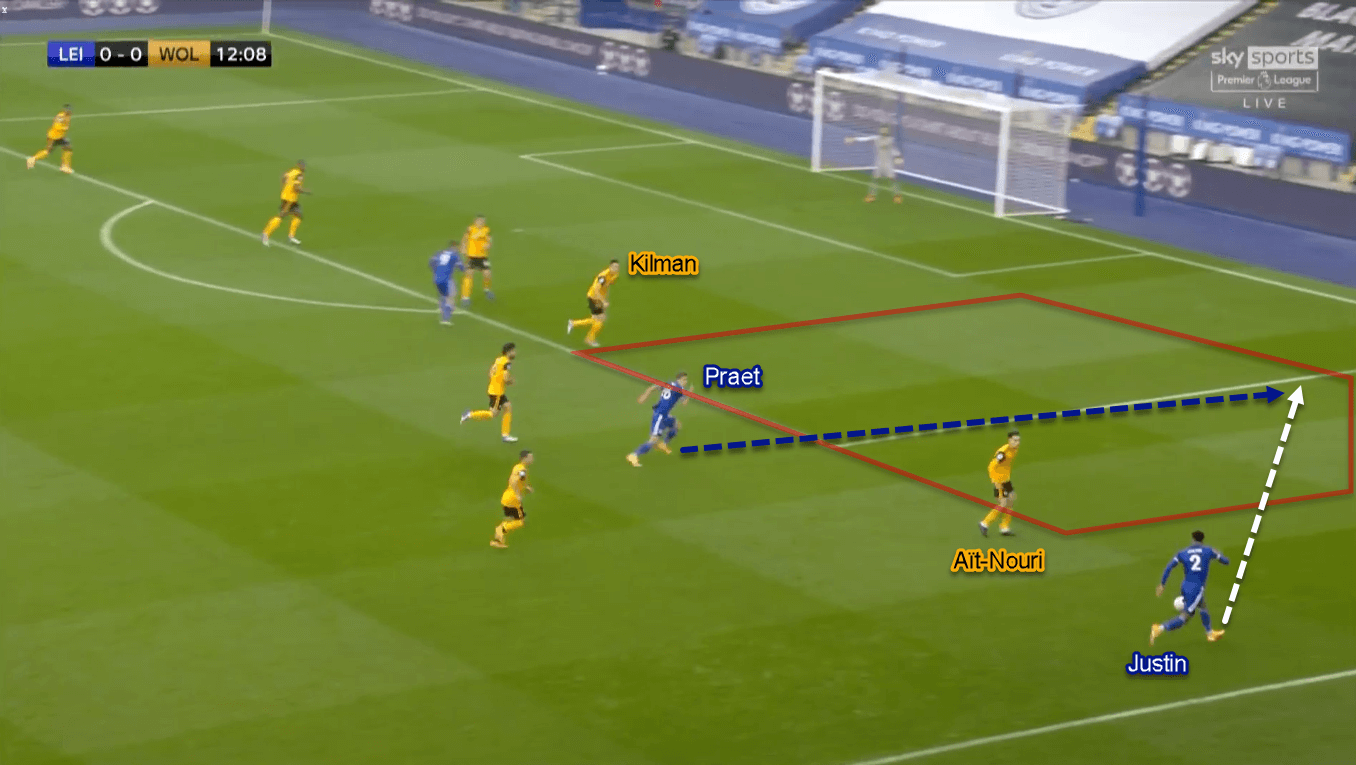

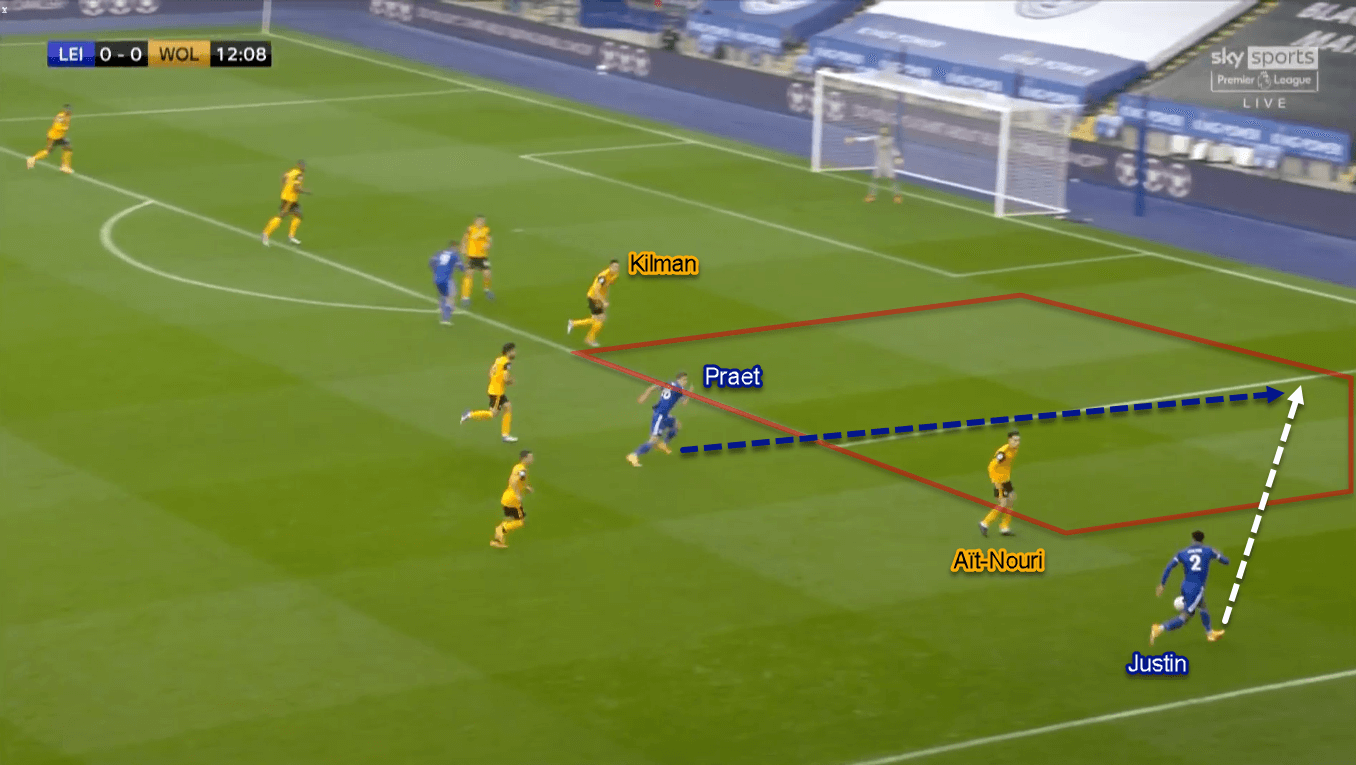

Next, Praet. The number 26 was tasked to help Justin making combinations in the right flank. Per the statistics, Leicester had 18 (42.86%) attacks from that side. Furthermore, the Belgian also helped his team penetrating Wolves’ defence by providing runs in behind inside the right half-space. Such runs were crucial to exploit the visitors’ defensive problem, which we will discuss in the next part.

Two defensive issues, two penalties allowed (part one)

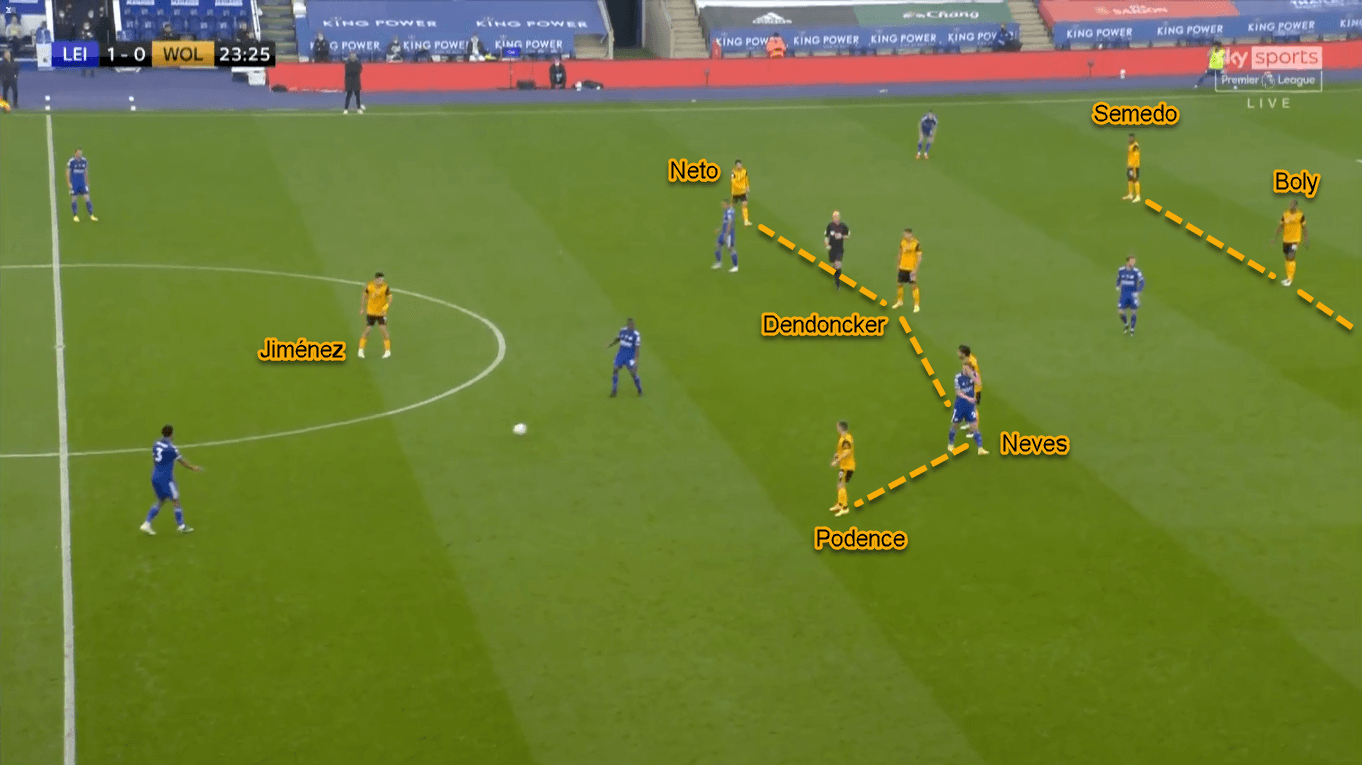

Nuno’s decision to shift his team’s defensive structure to 5–4–1 gave his wingers more responsibility. It means that both Neto and Podence had to focus more heavily to help his team maintaining the defensive compactness. However, problems occurred when one of them didn’t do the defensive task, particularly Podence.

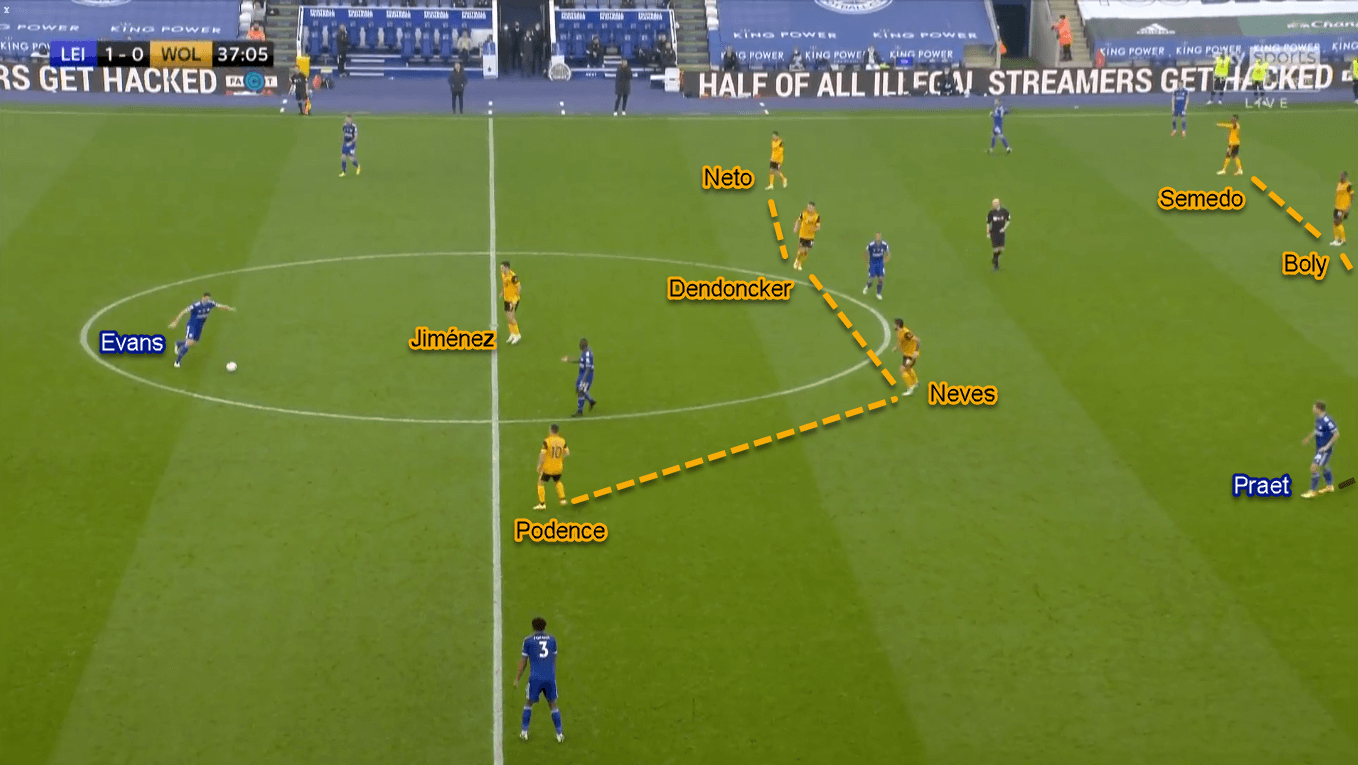

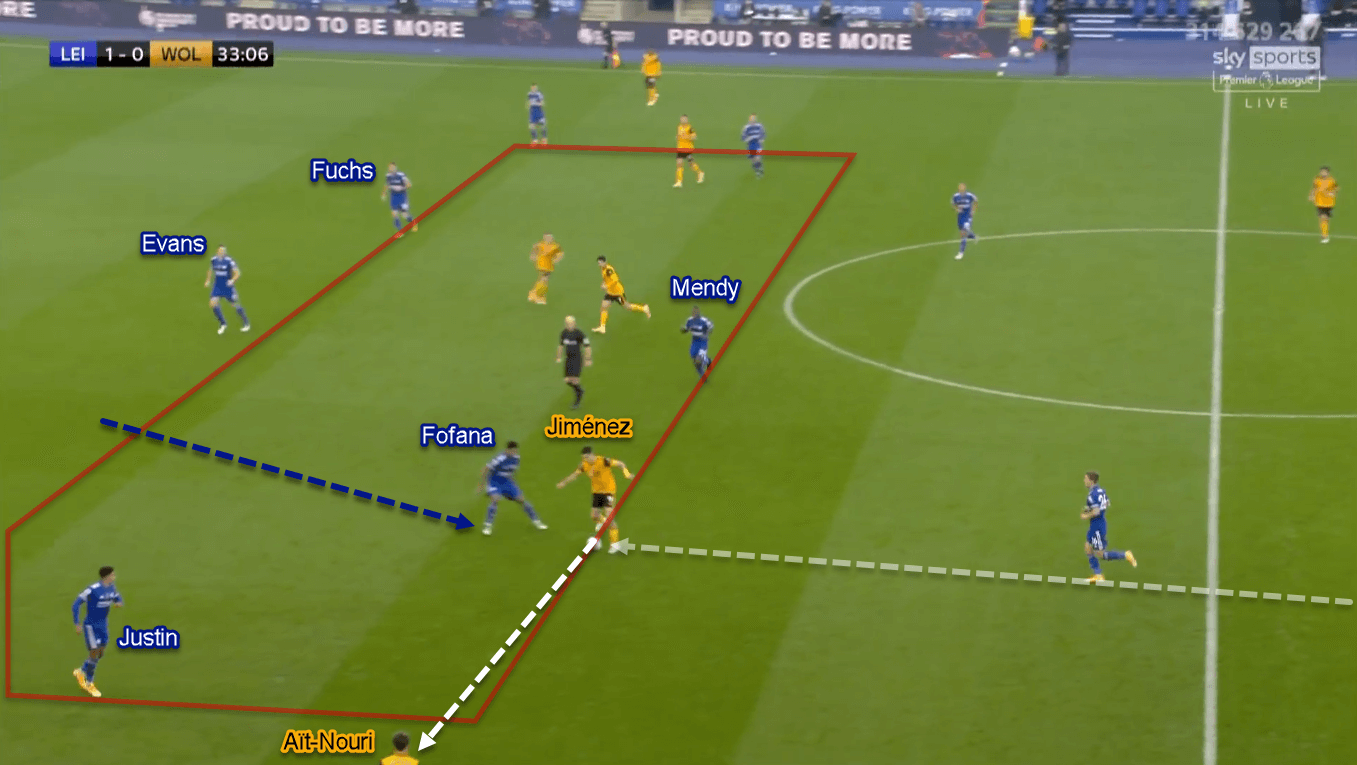

There were occasions when Podence was positioned (slightly) higher than his flank partner in defensive situations. Even more, there were also moments where he stood alongside Jiménez instead of the central midfielders. This advanced positioning made Wolves’ defensive structure go lopsided. It’s not just that, though. This could also open space inside the half-space where Podence should be situated. As a result, Leicester could exploit the problem through their mobile attacking midfielders.

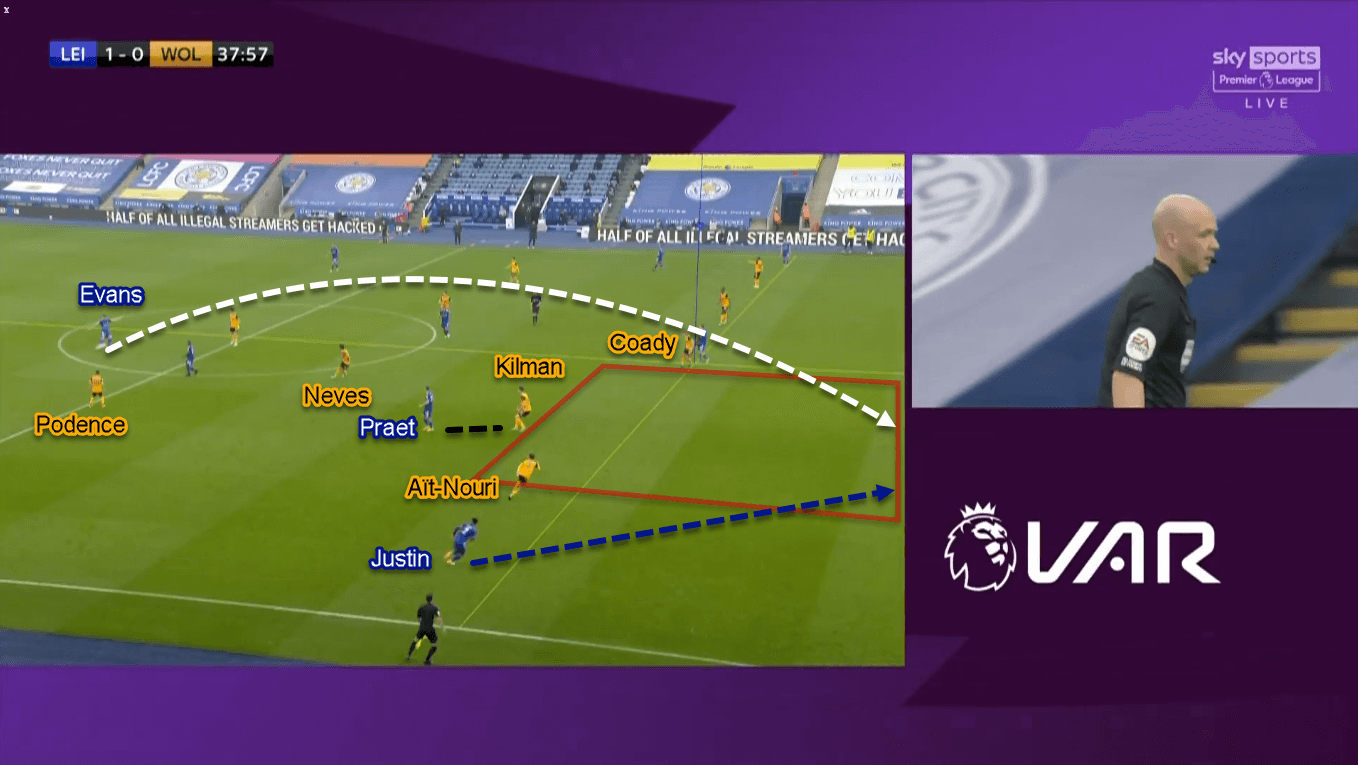

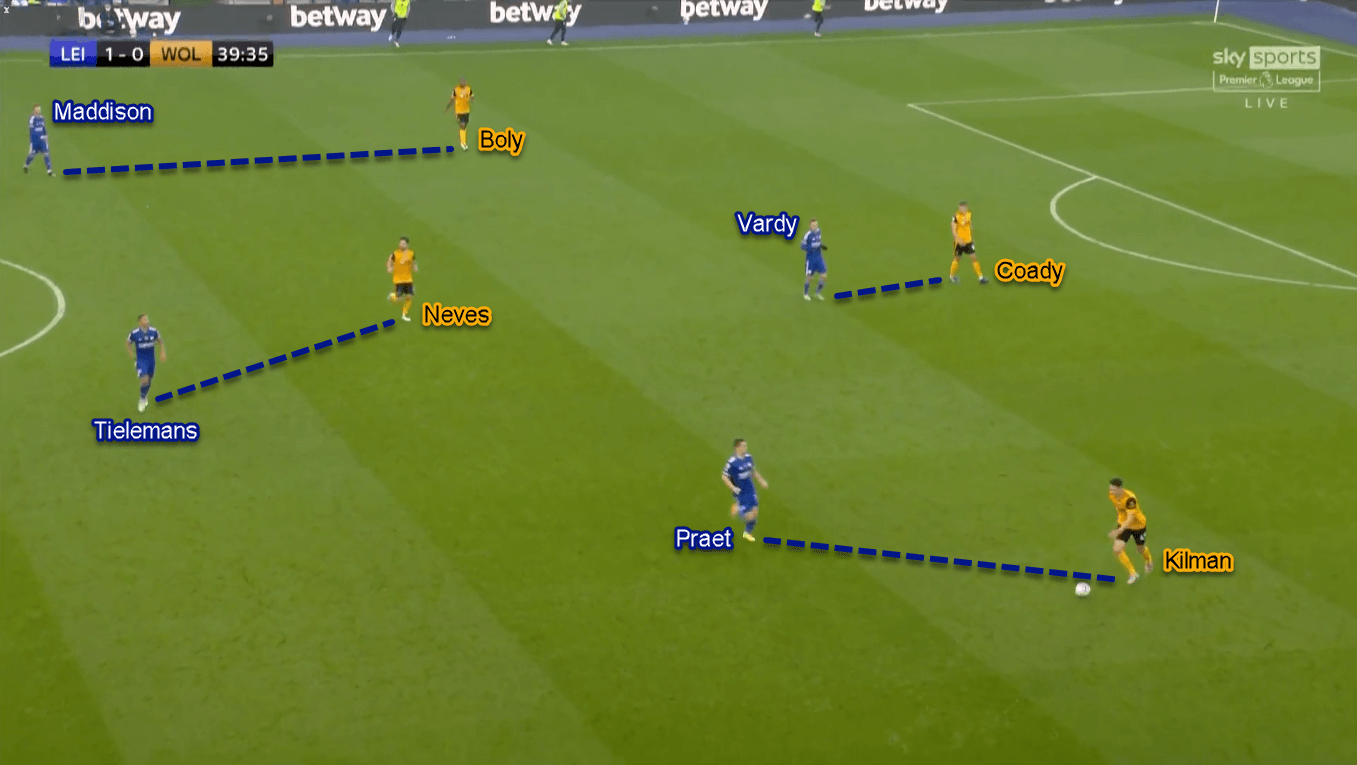

This particular issue even bore its fruit in the 38th minute. That time, Podence stood very close to Jiménez instead of Rúben Neves. This forced Kilman to step up from the defensive line so he could close Praet in between the lines. As Kilman went forward, a huge space appeared in the area he just vacated; between Coady and Aït-Nouri. This allowed Evans to send a long ball there; forcing the French wing-back to foul Justin inside the box.

Two defensive issues, two penalties allowed (part two)

Let’s get back to Wolves’ defensive approach in the flank. When Leicester had the ball in wide areas, the visitors’ wing-back would immediately step wide and press the man in blue. The objective was to limit the space and time for the opponent on the ball.

However, the wing-back’s movement was not followed by the nearby centre-back. This means that the outside centre-backs would stay within the backline instead of covering the space left by Semedo or Aït-Nouri. This approach was chosen so Wolves would have three defenders containing Vardy should Leicester try to play crosses to their marksman.

In one side, the approach worked. The stats showed that Leicester only managed four (20%) accurate crosses throughout the game. Ironically, the only goal of this match also happened from this defensive strategy.

As mentioned previously, the ball-side centre-back would stay put instead of coming nearby the wing-back. As a result, an ample space would appear in between them; inside the half-space to be more specific. This space then could be attacked by one of Leicester’s midfielders via a darting run in behind. For a fact, Vardy’s first penalty happened from a successful attempt of exploiting this issue.

Leicester’s defensive strategy (part one)

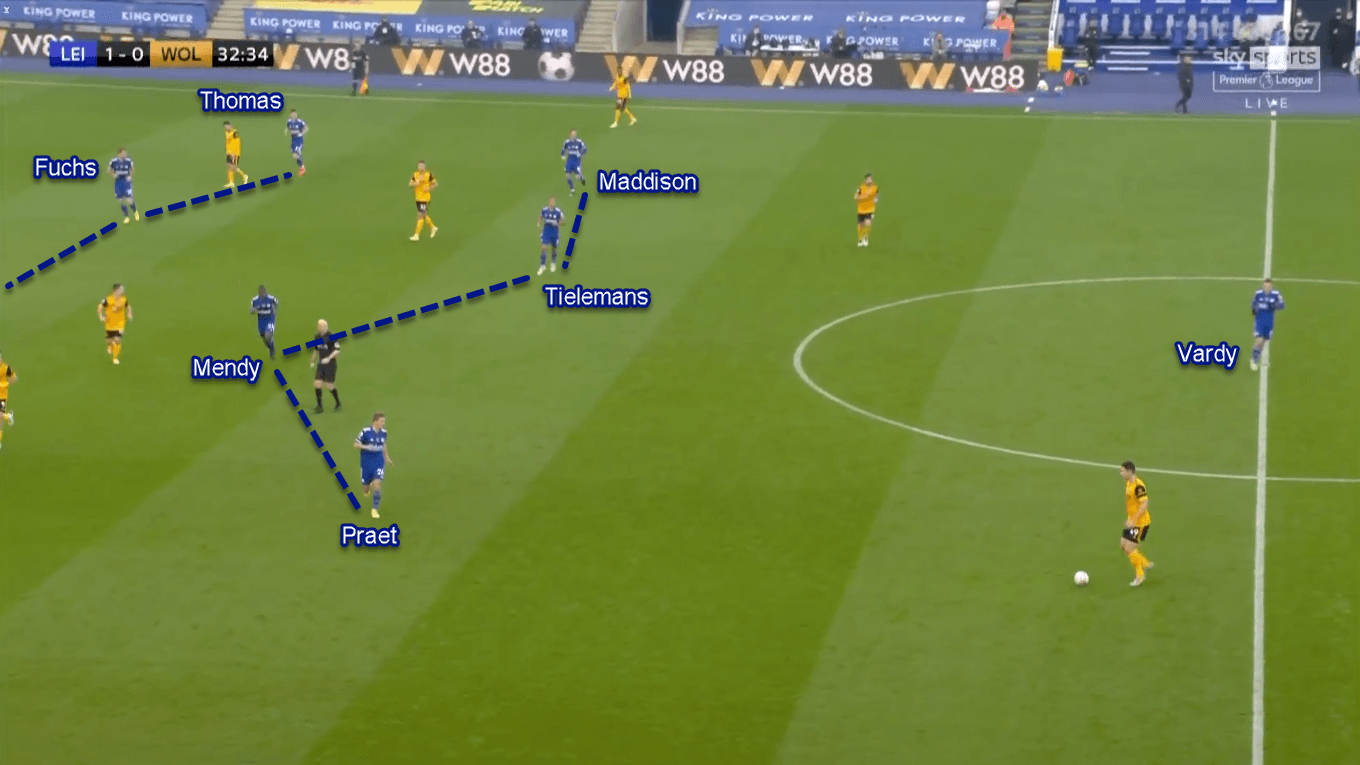

The Filberts’ initial defensive plan was actively pressing Wolves; up into their penalty box if necessary. The structure they used was 5–1–3–1. In this shape, Youri Tielemans stepped up and leaving Nampalys Mendy alone in front of the defenders.

Tielemans’ particular task was a part of Leicester’s strategy to mirror Wolves’ early third setup. It means that the Foxes would press in a man-oriented manner against their opponents’ deeper players, except the goalkeeper. In the process, Tielemans was tasked to press Neves; meanwhile, Praet, Vardy, and Maddison had to press the centre-backs in front of them. The objective behind this was to prevent Wolves from building their attacks smoothly from the back.

When Wolves enjoyed more possession, particularly in the last 15 minutes of each half, Leicester would drop to a mid-block 5–4–1. In this shape, Vardy has less defensive workload and would stay much more forward compared to his teammates. Despite the rather cautious structure, Leicester kept their aggression to prevent Wolves enjoying possession for a prolonged time.

Leicester’s defensive strategy (part two)

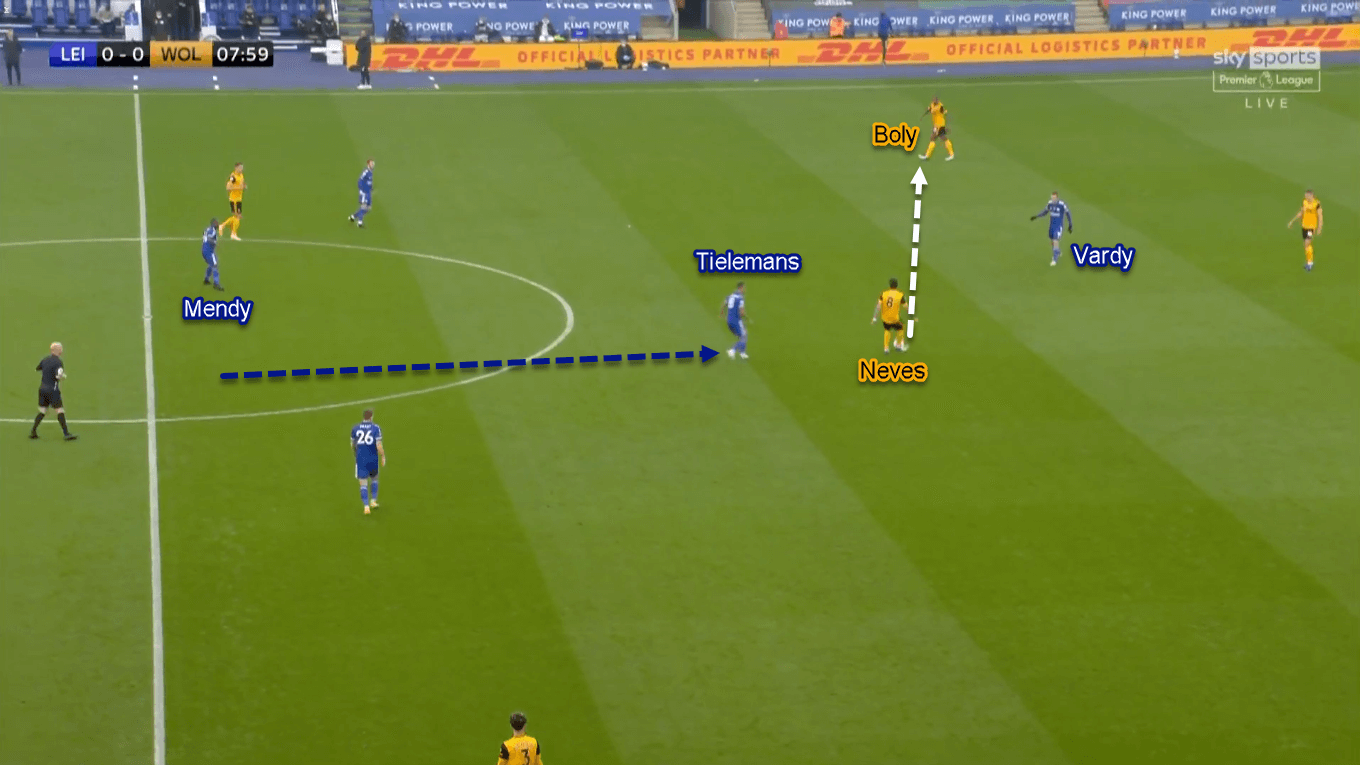

The first way they did that was by sending one of the central midfielders to press Neves whenever he has the ball. By doing so, Leicester would force the Portuguese to quickly spread the ball wide as well as preventing him from building attacks centrally. Tielemans was the midfielder who had more responsibility to press Neves, while Mendy provided cover by staying in the midfield line.

If Wolves tried to penetrate through wide areas, Leicester’s ball-side wing-back would immediately step up to the midfield line and press the opponents’ flank player. By doing so, he could even force the opponent to play backwards. The statistics back this as Semedo (12), and Aït-Nouri (17) were forced to make 39 negative passes throughout the game.

One notable thing of Leicester’s flank press was the behaviour of the nearby centre-back. Instead of staying put, either Fuchs or Fofana would come closer to their respective wing-back. The main objective behind this was to cover the space in the defensive line. Another reason was to close the nearest potential progressive options for Wolves as their forwards liked to play in between the lines.

It’s safe to say that Leicester’s defensive tactics worked brilliantly. In the first half, they limited Wolves to only one long-range shot just before the whistle. The visitors did increase their shooting outputs and expected goals (xG) tally after the break. However, it’s not enough to break the Foxes down. Per the stats, Wolves finished the game with only 0.66 xG from eight goalscoring attempts.

Another toothless performance

If Neves didn’t attempt to shoot in the stoppage time, Wolves would end the first half with zero shots. Surely not a good thing for a team who desire another European ticket for next season. But how did that happen? What was their attacking strategy in this game?

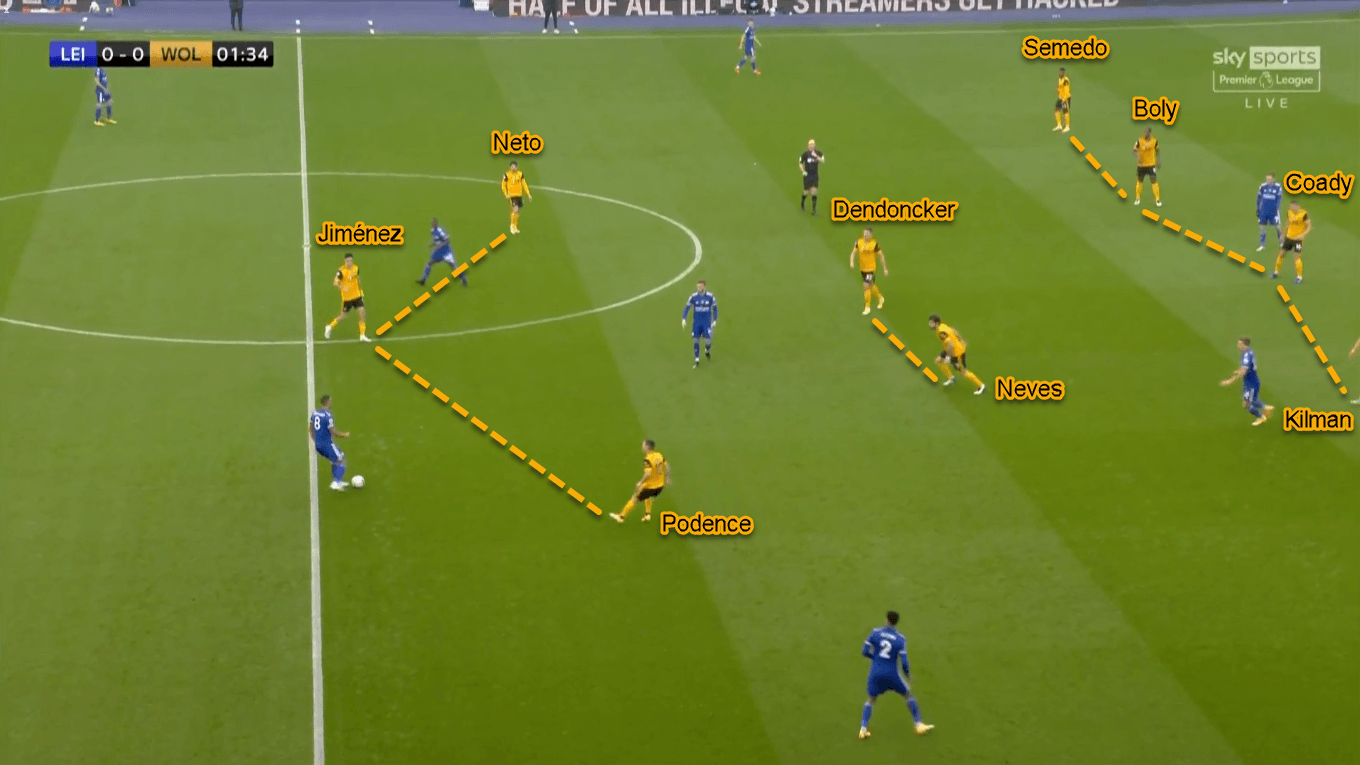

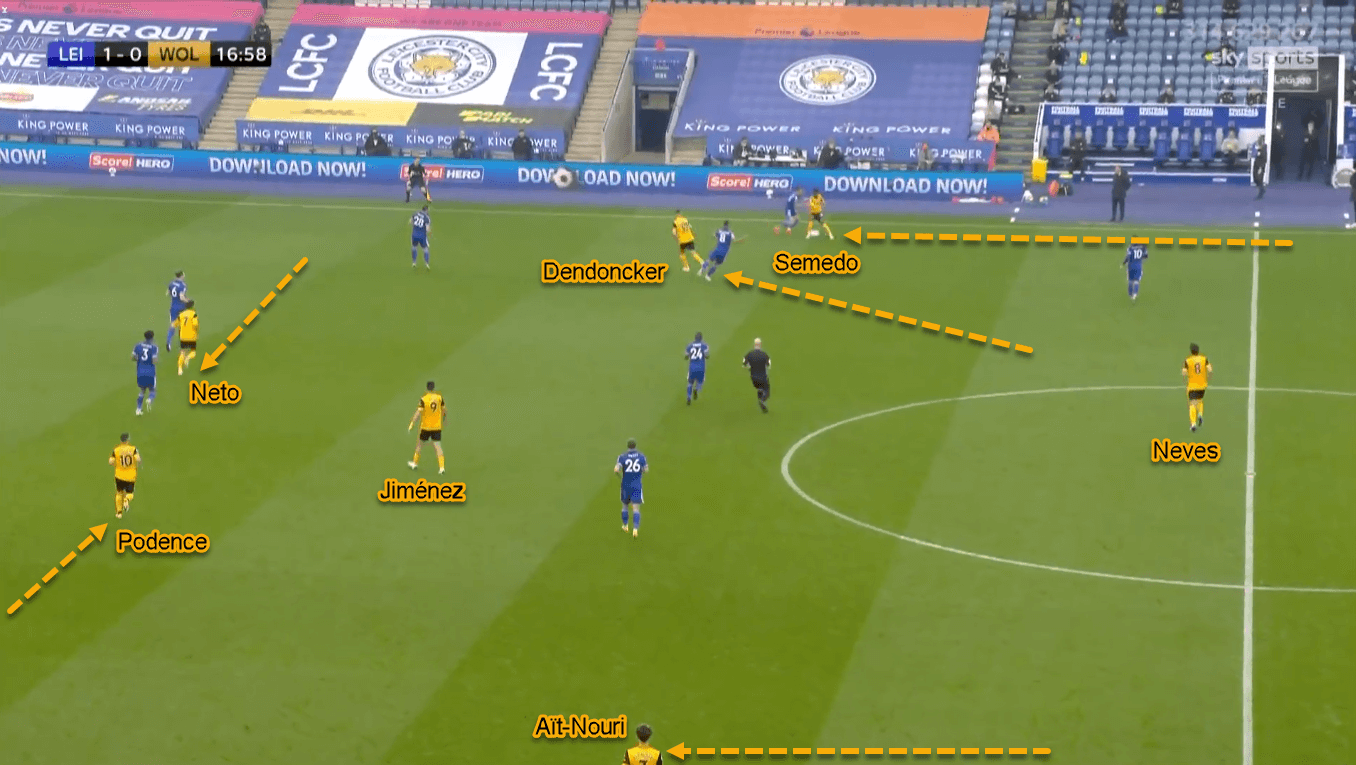

Structure-wise, Nuno deployed his men in a 3–1–3–3-ish fashion. The first notable thing in this setup was the different tasks between the midfielders. Neves was given the responsibility to bridge the centre-backs and the attackers, while Leander Dendoncker was tasked to join the forwards and play in between the lines.

Upfront, the forwards were playing narrow while the wing-backs provided width in both flanks. The objective behind this was to allow Jiménez, Podence, and Neto to play in between the lines. However, there was not much success when accessing the trio there. That’s because Leicester would immediately send their nearest centre-back to press the receiving attacker, even when the ball was still en route to the forward.

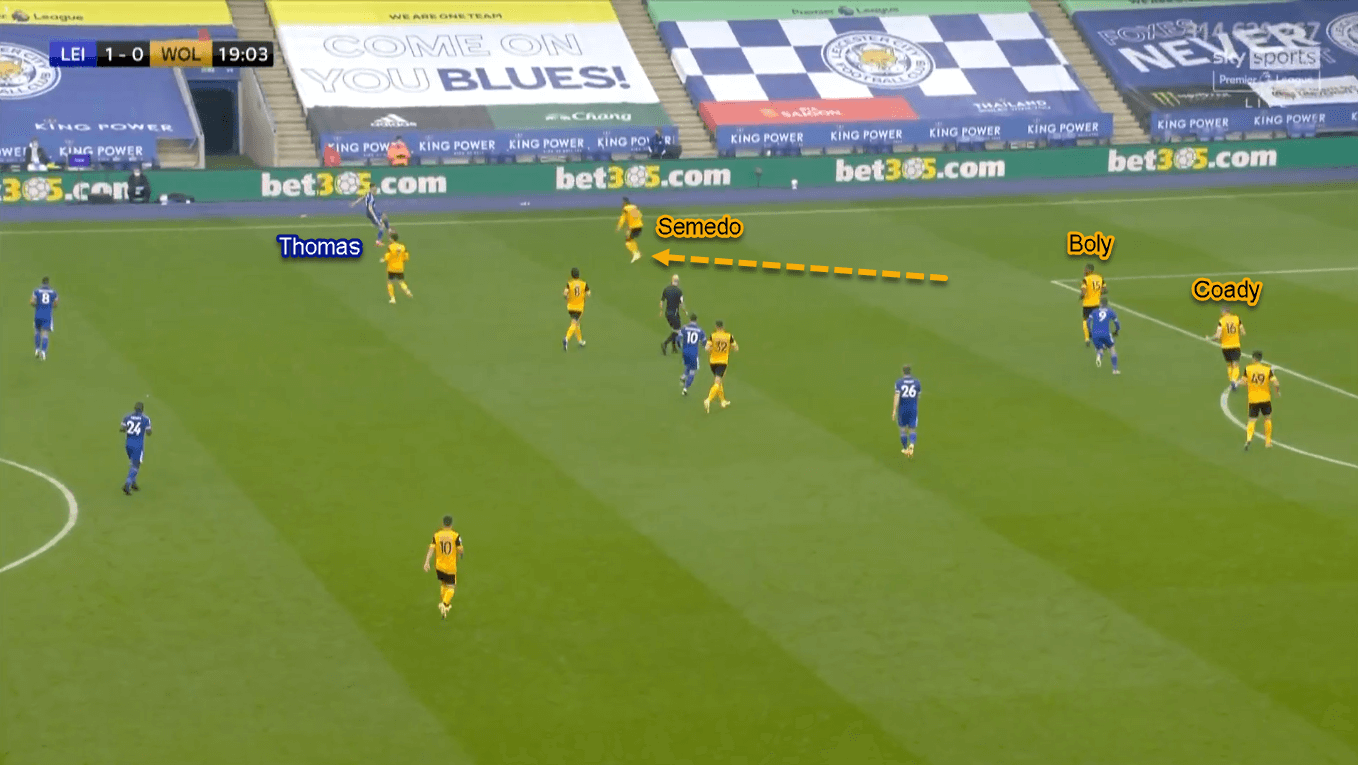

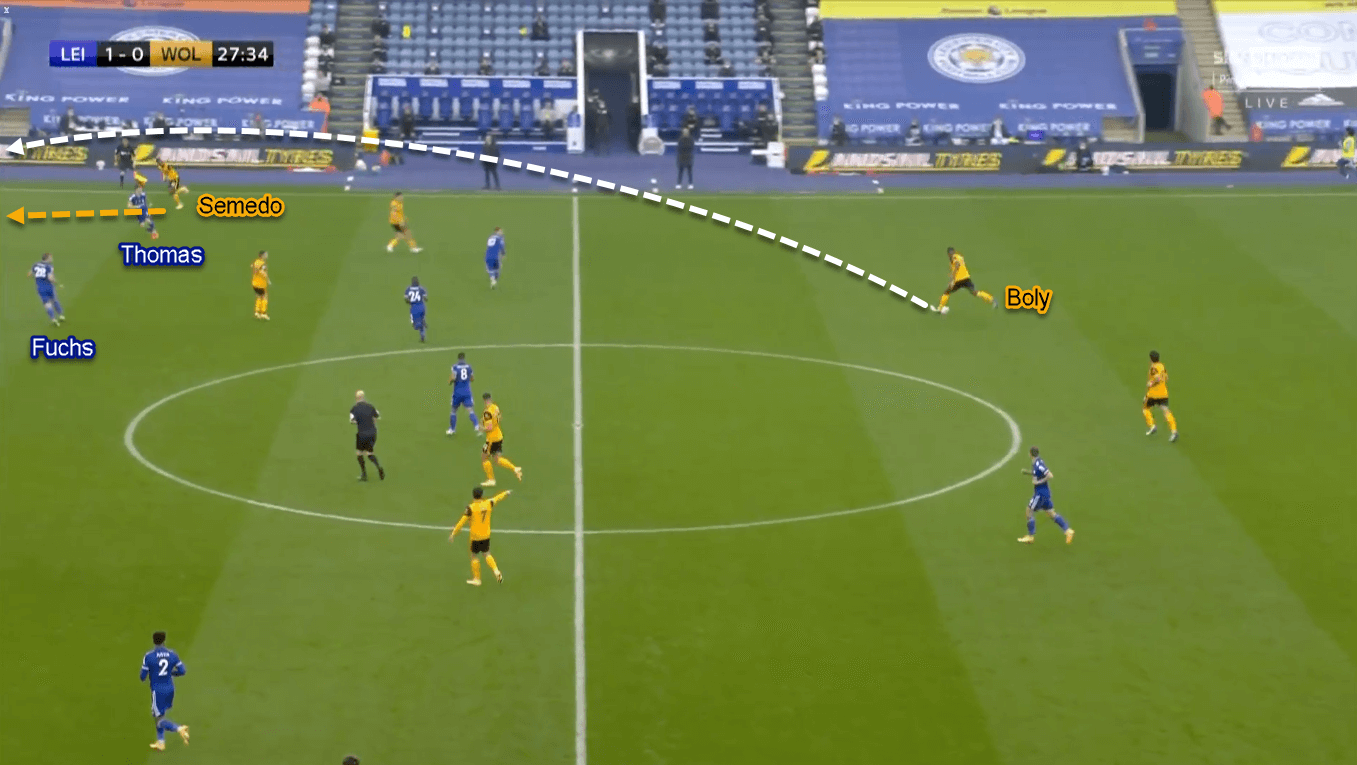

As they got nullified often when playing short, Wolves also used a more direct approach. That was by sending (aerial) through-balls to the overlapping Semedo in behind. The right wing-back was probably chosen because of his attacking traits or Nuno considered Fuchs-Thomas pairing as Leicester’s weakest point defensively.

After receiving, Semedo was tasked to provide crosses into the box. However, Wolves’ attacking setup didn’t help him much. As all the forwards would start their runs in between the lines, Wolves would have not much variation to receive the crosses. No wonder why all three of Semedo’s crosses went inaccurate.

Second-half adjustments

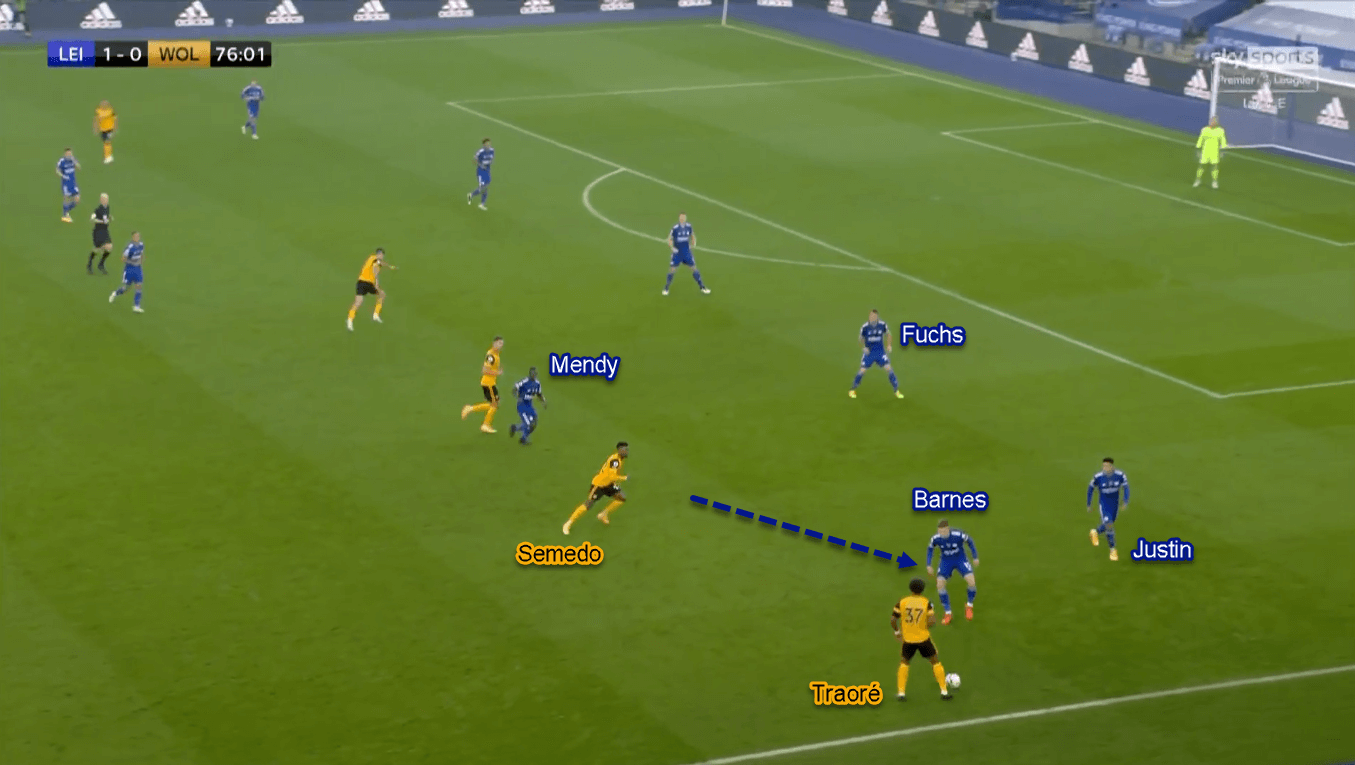

Nuno subbed in Traoré for the uninspiring Podence just after an hour. This change also marked a tactical adjustment for Wolves as Traoré likes to play wide more often. The substitution also gave the Wanderers more threat in the right flank with a combination of Traoré and Semedo.

Rodgers realised this and also adjusted his defensive tactics. Structure-wise, Leicester kept their 5–4–1. However, their flank approach changed. Instead of asking the left wing-back to step up and press, Rodgers instructed him to stay within the backline. Then, the ball-side winger would drift a bit from the area and press Wolves’ on-ball flank player.

The objective behind that was to provide more solidity at the back, as Leicester would keep their back-five intact for all of the time. It’s not just that, though. Barnes — the new left-winger — still had a fresh pair of legs to contain Traoré in the right flank. Even though he’s not a naturally defensive player, Barnes could help his team to limit Semedo and Traoré’s threat in the last quarter-hour of the game.

Conclusion

Six games, six wins. What an incredible job by Rodgers and his men in the last two weeks. They were in the fourth place and four points adrift from the league leaders back then. Now, they are at the top of the table at least until they host Liverpool on 21 November. All because of the manager’s tactical brilliance and his armada’s superb display on the pitch.

Yet, the same could not be said to Nuno’s Wolves. Their shaky start earlier this season was treated positively with three wins from the previous four matches, yet they had to drop again after a dull display against Leicester. Their next three games will be against Southampton, Arsenal, and Liverpool. Will the dark clouds move away from the Molineux? Only Nuno can provide an answer to that.

Comments