The city of London hosted another Premier League classic last weekend. In the six-goal thriller, visitors West Ham United successfully salvaged a draw against Tottenham Hotspur after conceding three goals in the first 16 minutes. Such a result helped them to continue their positive run after scoring seven goals in the previous two gameweeks.

Ironically, all of West Ham’s goals came in the closing 16 minutes of the game. What actually happened in this dramatic match? This tactical analysis will try to answer that by examining both managers’ tactics and adjustments throughout the 90 minutes.

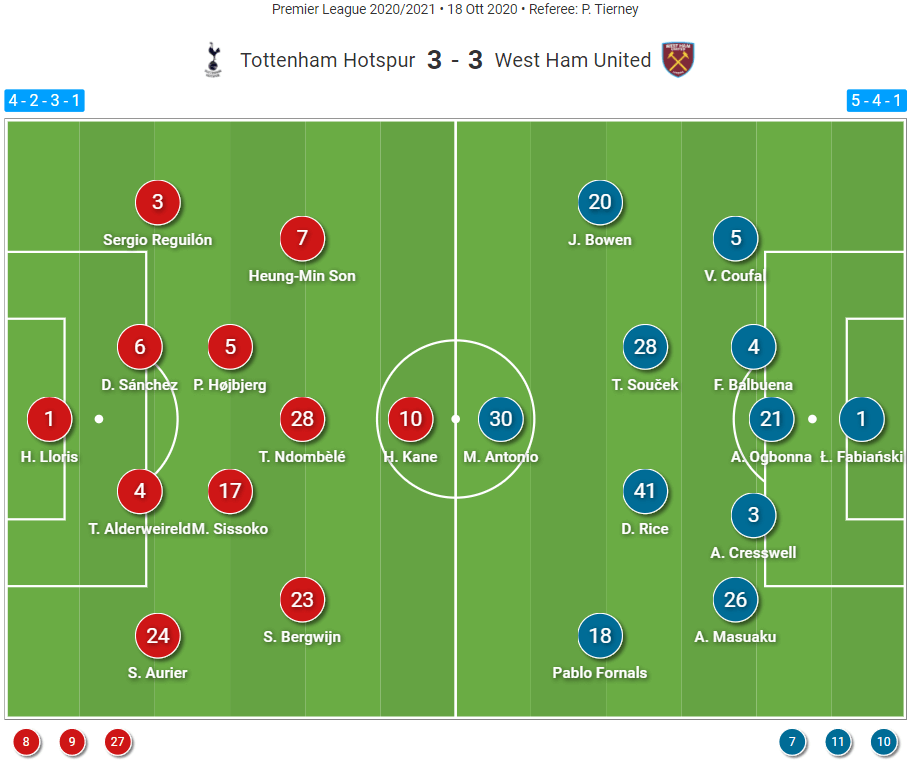

Lineups

José Mourinho opted for the usual 4–2–3–1 for Tottenham. The back-four consisted of Serge Aurier, Toby Alderweireld, Davinson Sánchez and former Real Madrid man Sergio Reguilón. Talisman Harry Kane led the attacking line supported by the trio of Steven Bergwijn, Tanguy Ndombélé, and Son Heung-min behind him. Names like Harry Winks, Lucas Moura, and multiple Champions League winner Gareth Bale had to play from the bench.

In the opposite side, David Moyes chose 5–4–1 for his team. Their backline included players like Vladimír Coufal, Fabián Balbuena, Angelo Ogbonna, Aaron Cresswell, and Fuka-Arthur Masuaku. Upfront, Michail Antonio started as the lone striker; helped by the quartet of Jarrod Bowen, Tomáš Souček, Declan Rice, and Pablo Fornals in the midfield. The Hammers’ dugout was filled by the likes of Andriy Yarmolenko, Manuel Lanzini, and Robert Snodgrass.

Spurs ran riot in the first quarter-hour (part one)

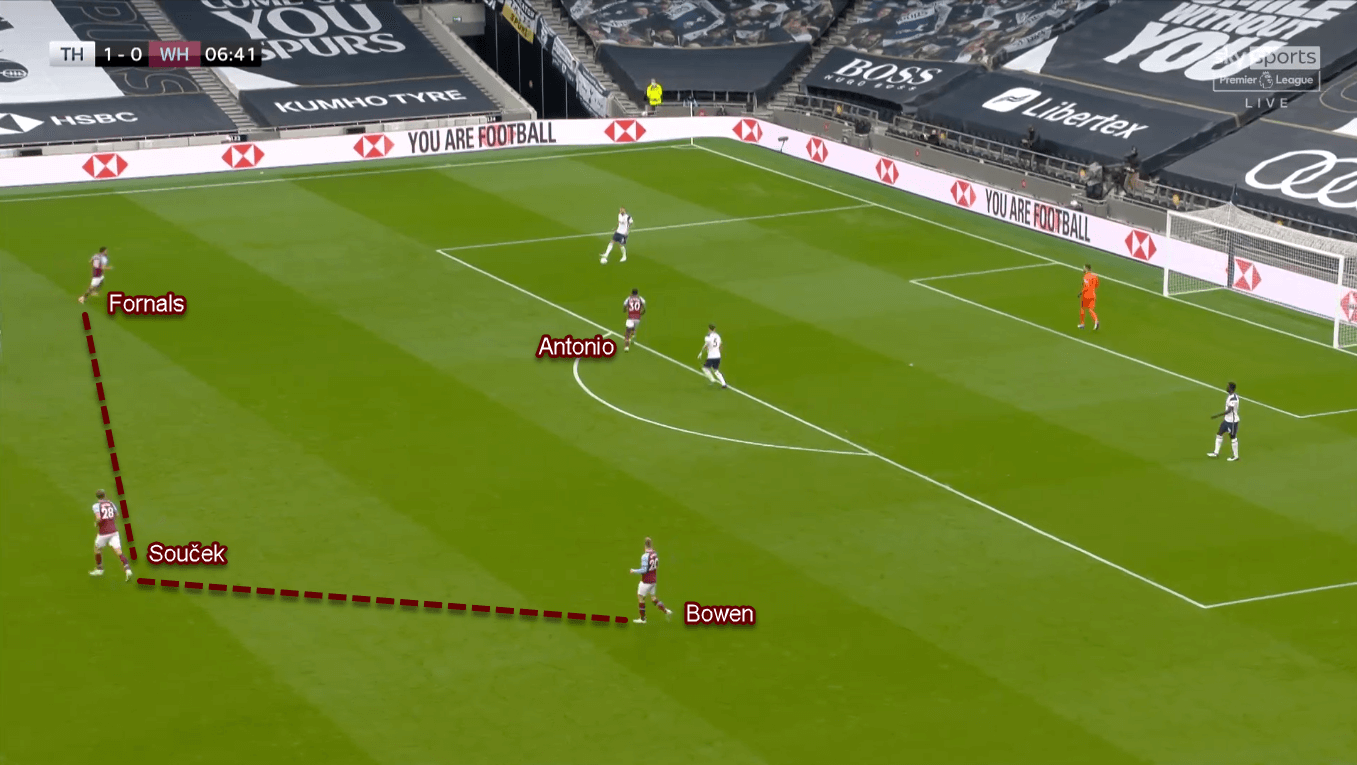

This analysis will start by examining how Spurs successfully scored three goals past Łukasz Fabiański. But before that, we need to break down West Ham’s defensive tactics first. Since the first whistle been blown, the visitors tried to defend quite aggressively in a 5–1–3–1 structure.

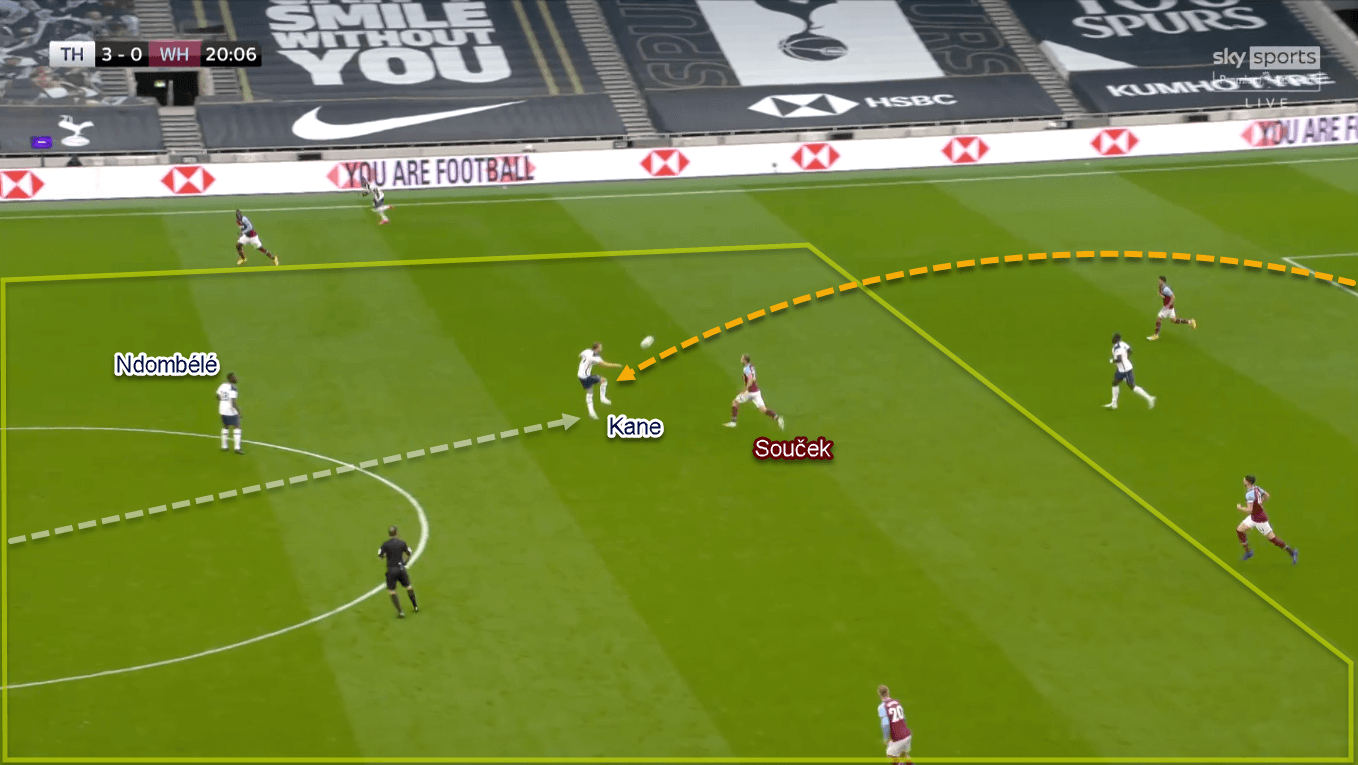

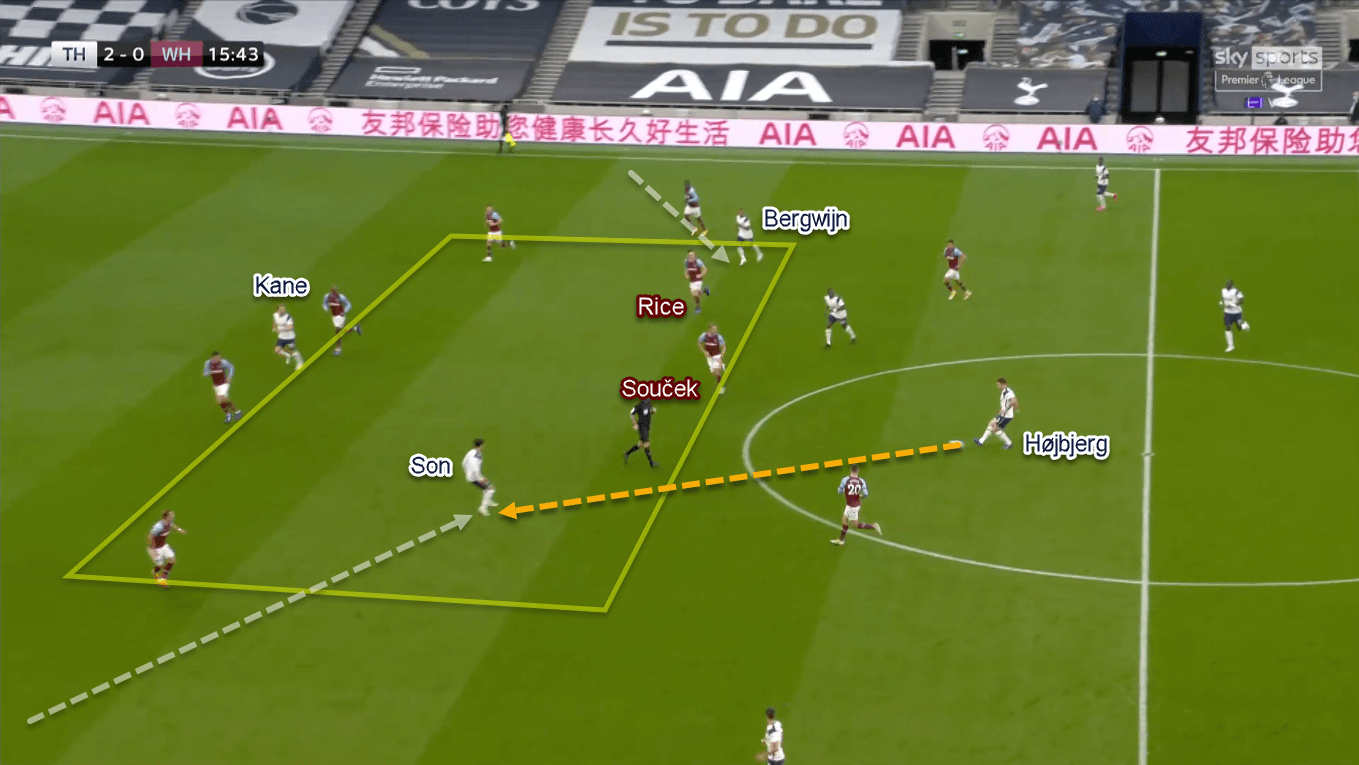

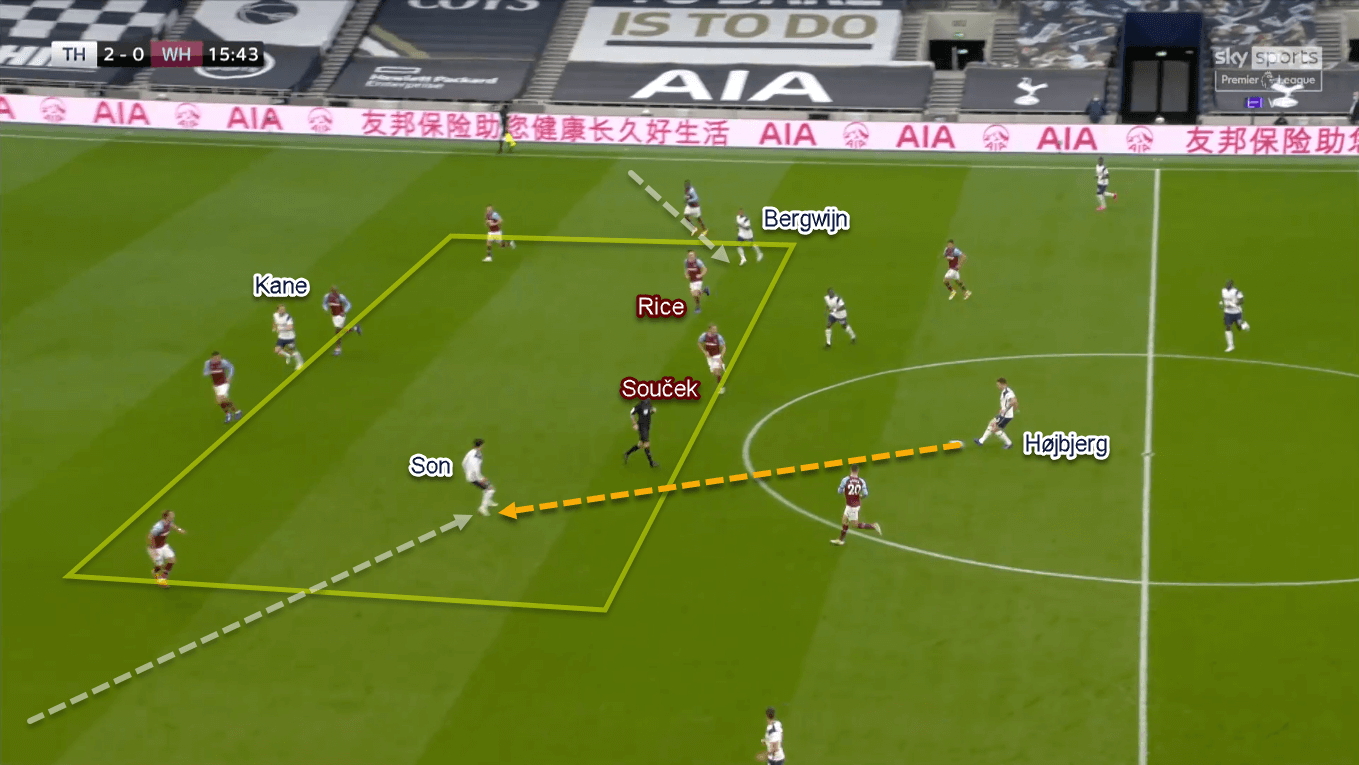

In that shape, wingers Bowen and Fornals were positioned in between Spurs’ full-backs and centre-backs. They were tasked to press on Spurs’ ball-side centre-back on their respective side whenever the Lilywhites tried to play short. In between them, there was Souček. The Czech was tasked to step up from the midfield line and join the wingers to prevent Spurs from building their attacks smoothly through the central lanes.

However, this actually gave West Ham a big defensive issue. That’s because Souček’s forward movement would leave Rice alone in front of the defenders. To be more clear, that would force the Englishman to cover huge space in between the lines. This problem was exploited so many times by Spurs early in the game.

Spurs ran riot in the first quarter-hour (part two)

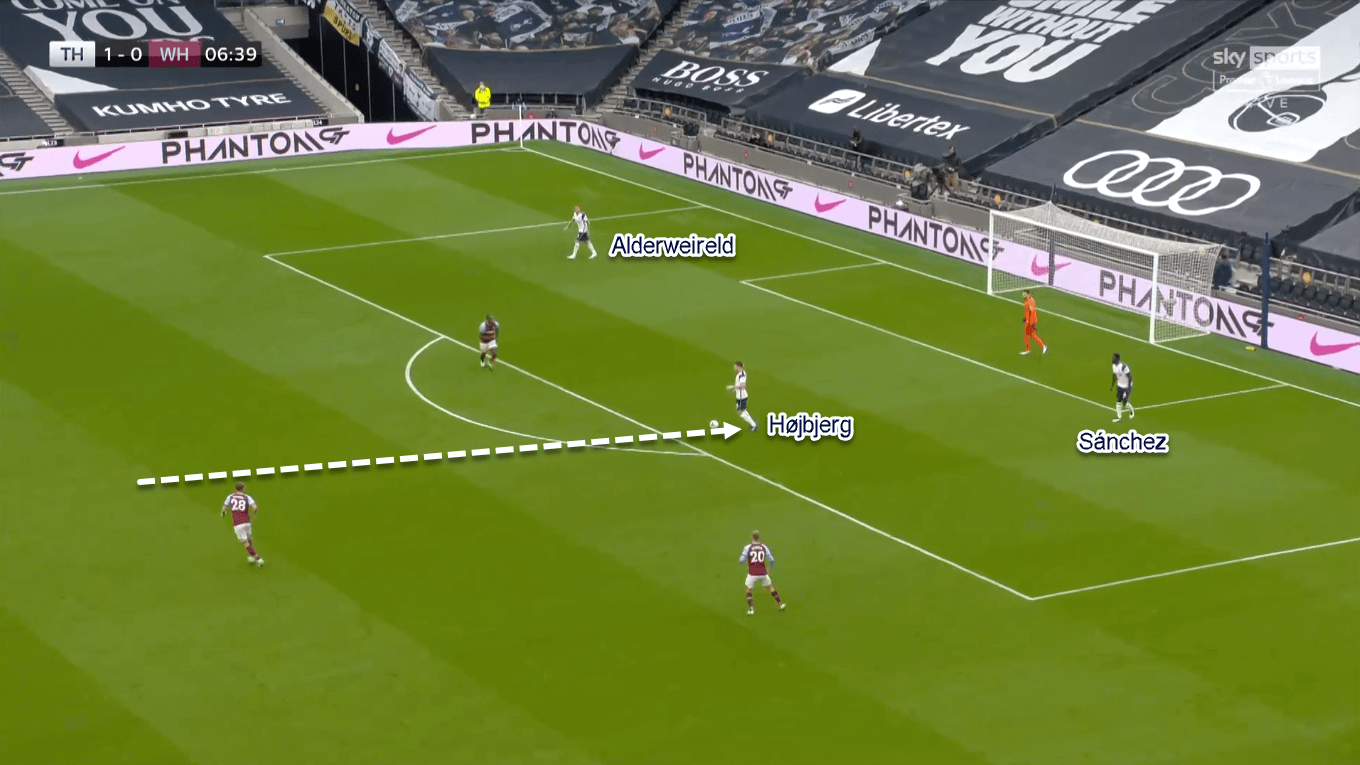

Now let’s move to the home side’s attacking approach. When his team were trying to build attacks, Mourinho would ask Pierre-Emile Højbjerg to drop in between the centre-backs. There were two objectives that he tried to achieve by giving the Dane such an instruction, as follow:

First, to help Spurs have a numerical superiority at the back. With three players against the lone Antonio, Spurs would control the ball with more ease in their early third. Second, to attract pressure from the visitors. When Højbjerg dropped, there were occasions where Souček would follow him. This would even pull the Czech further from Rice; thus opening more space in between West Ham’s defensive lines.

Good for Tottenham, they had two players in between the lines. The first was Ndombélé, and the second was Kane. To reach them, Spurs would utilise their deeper players — and even Hugo Lloris — to send aerial balls to the halfway line. After receiving, they would try to quickly find Son and/or Bergwijn with aerial balls in behind.

Kane was given the license to drop from his position to provide numerical superiority against Rice in the midfield area. Even more, he was trusted with more attacking responsibilities than Ndombélé. Due to his great passing ability, Kane was crucial in distributing long balls in behind to the pacey wingers. Tottenham’s opening goal was the main proof of the effectiveness of this approach.

Early adjustments from Moyes

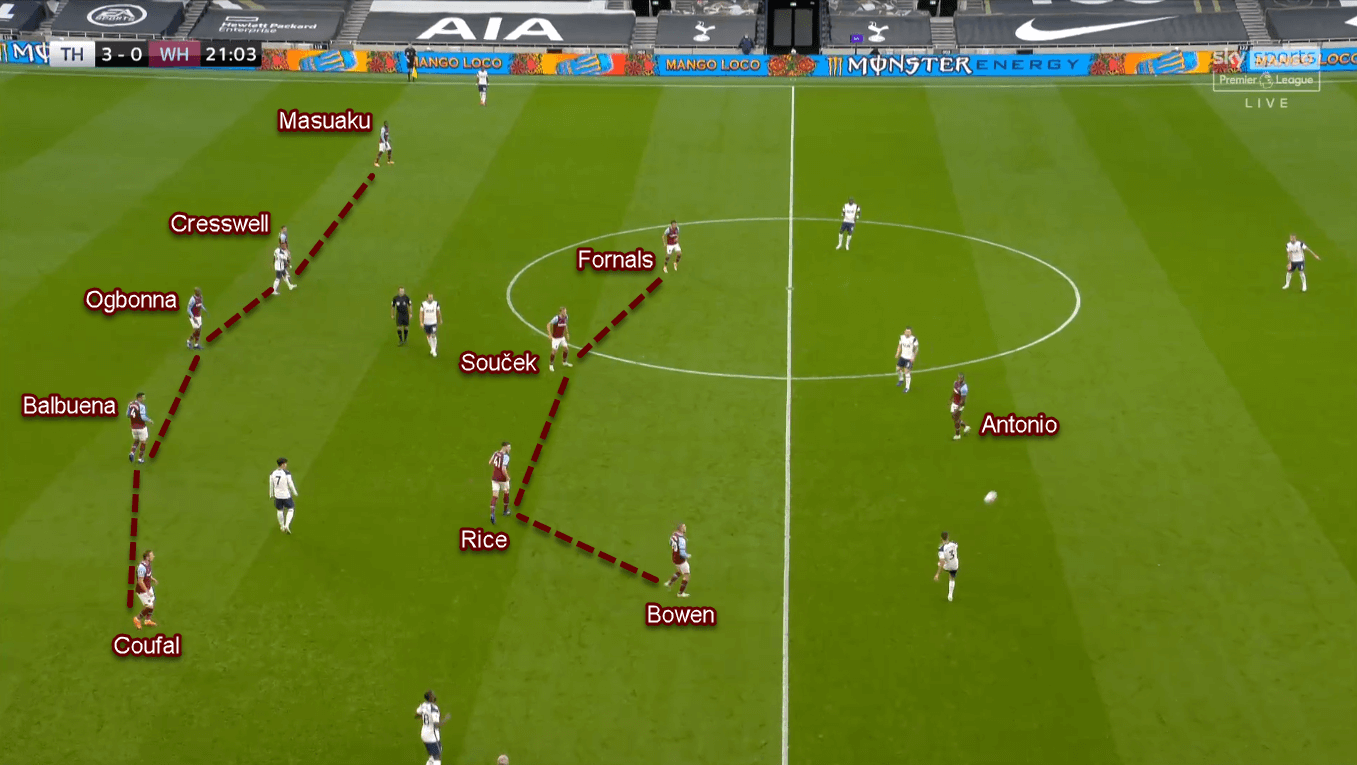

Knowing that his men were overrun heavily in the midfield, Moyes adjusted his defensive tactics. The first thing was by changing the structure to 5–2–3. In the process, Souček was tasked to drop back alongside Rice; thus providing more support in front of the defenders.

Upfront, Fornals and Antonio swapped places; with the former standing a bit deeper than his attacking comrades. That’s to keep closing the central lanes while giving Antonio the chance to reserve more energy for transitions. However, both players would return to their initial positions when West Ham were defending in a mid-block.

When such a thing happened, they would move to a 5–4–1, with Antonio alone in the first pressing line. However, a similar defensive issue still occurred. That being a lack of vertical compactness; therefore giving Spurs lots of space in between the lines.

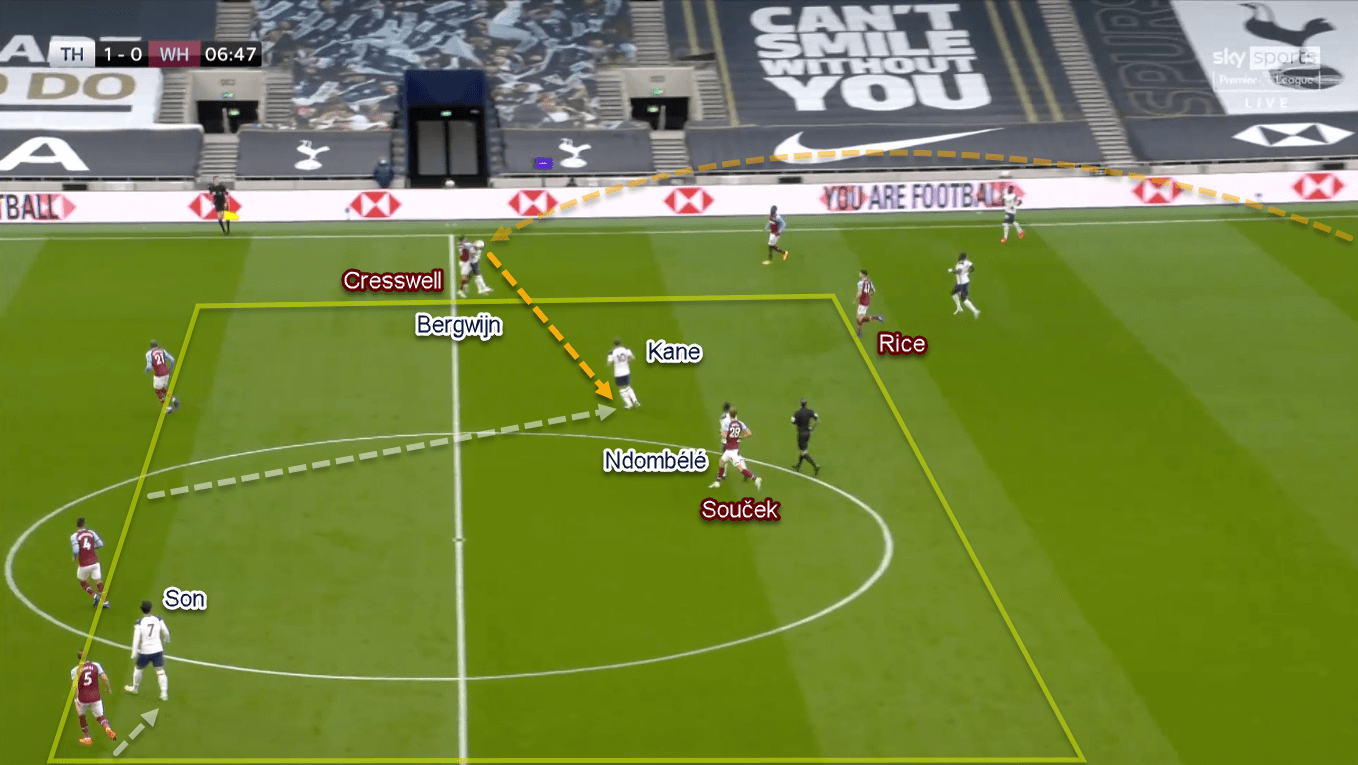

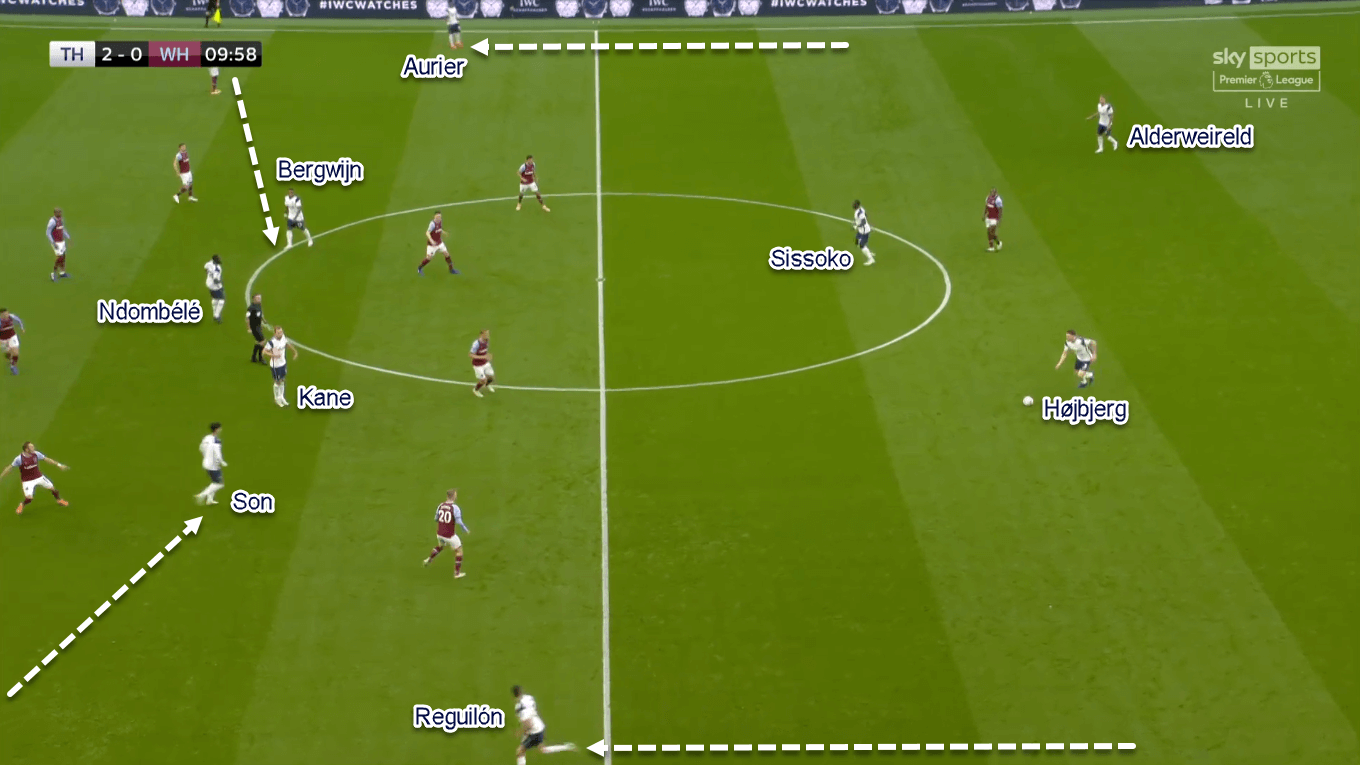

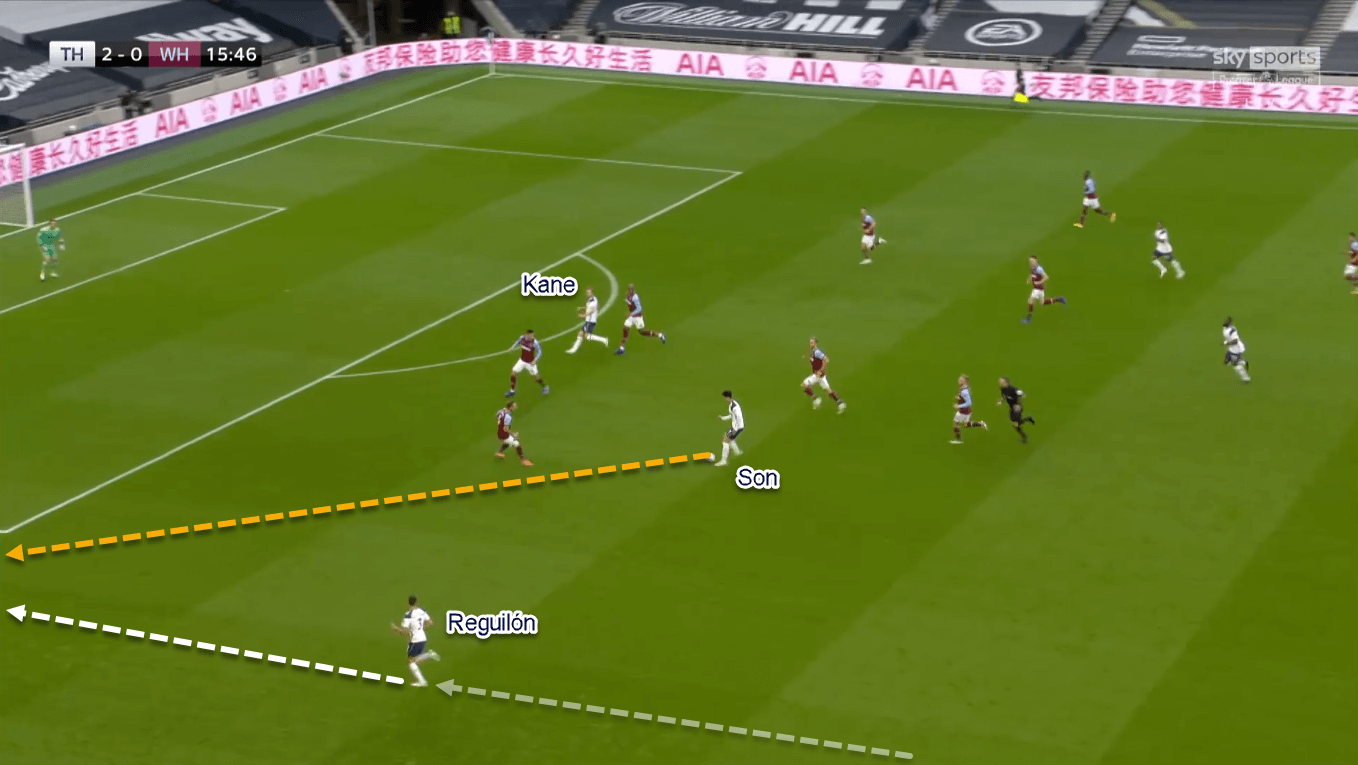

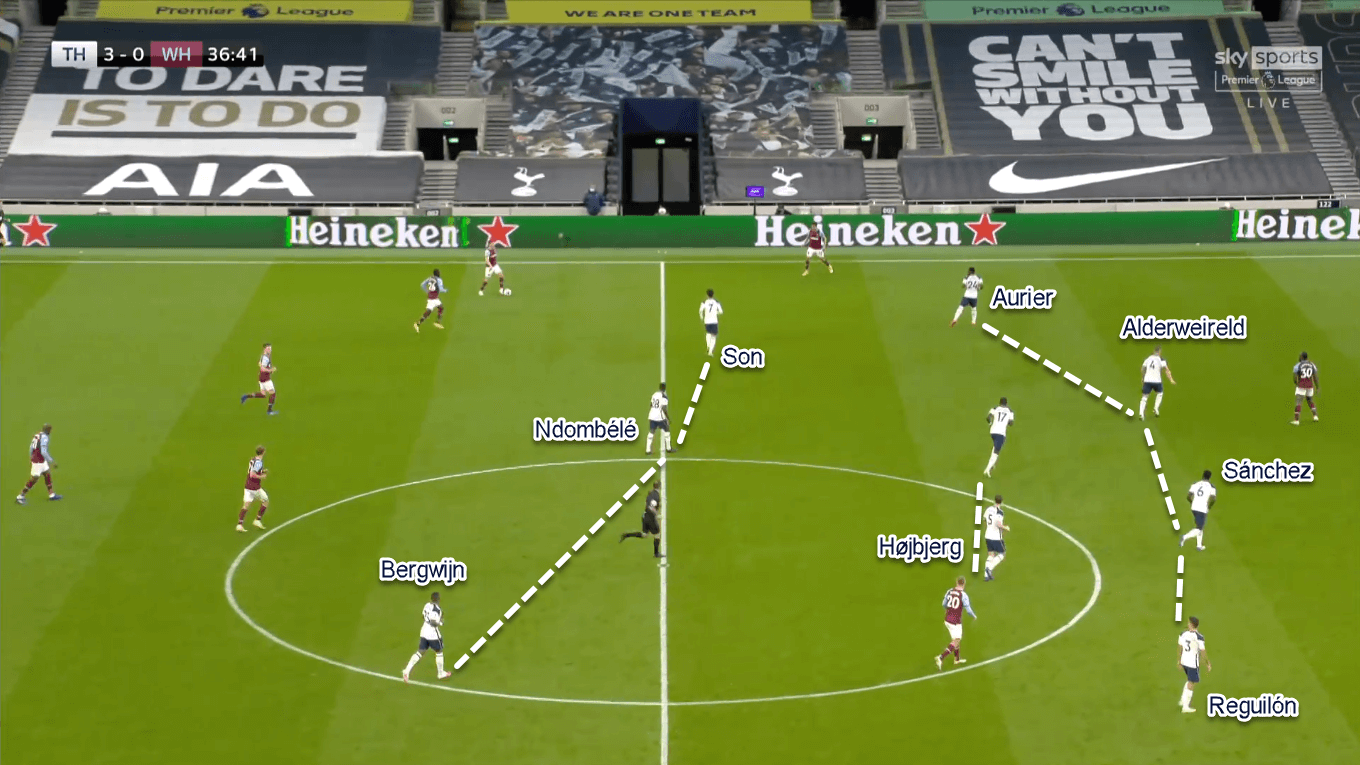

On possession, Spurs would play in a 2–4–4-ish structure. The first notable thing was Højbjerg’s return to the midfield alongside Sissoko. Next, the wingers were tucked inside while the full-backs advanced to provide the width. With Son and Bergwijn playing narrowly, Spurs would have up to four attackers playing in between the lines at the same time.

As expected, their main target on possession was accessing those attackers. After receiving, one of them would send the ball to the marauding full-backs in the flanks. The full-backs — now in the final third — then were tasked to cross the ball immediately into the box. For a fact, Kane’s second goal came from such a sequence.

The Hammers‘ attempt to damage Spurs

Despite being on the back foot for the majority of the first half, that didn’t mean West Ham had no attacking plans. The statistics showed that they managed to get 0.47 attacks per minute in the opening period. To compare, Tottenham even only managed 0.31. How so?

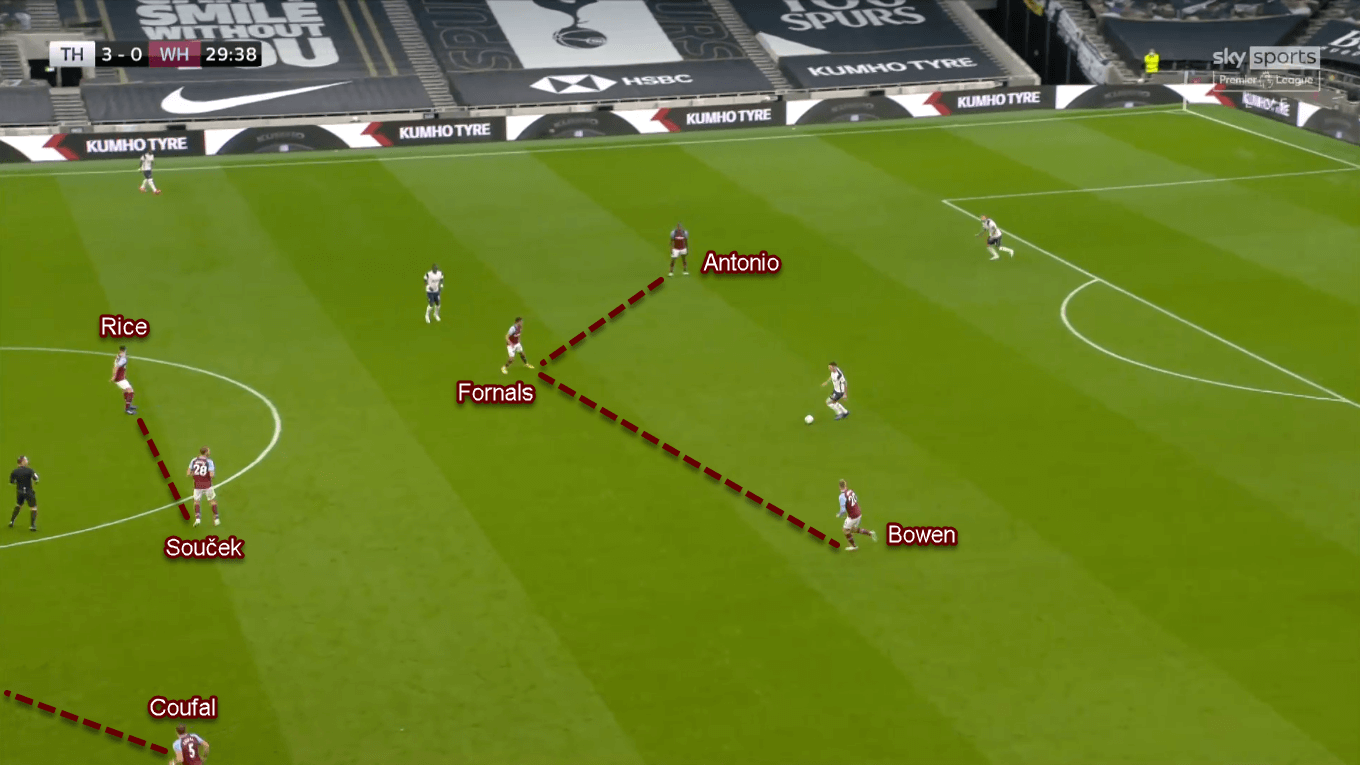

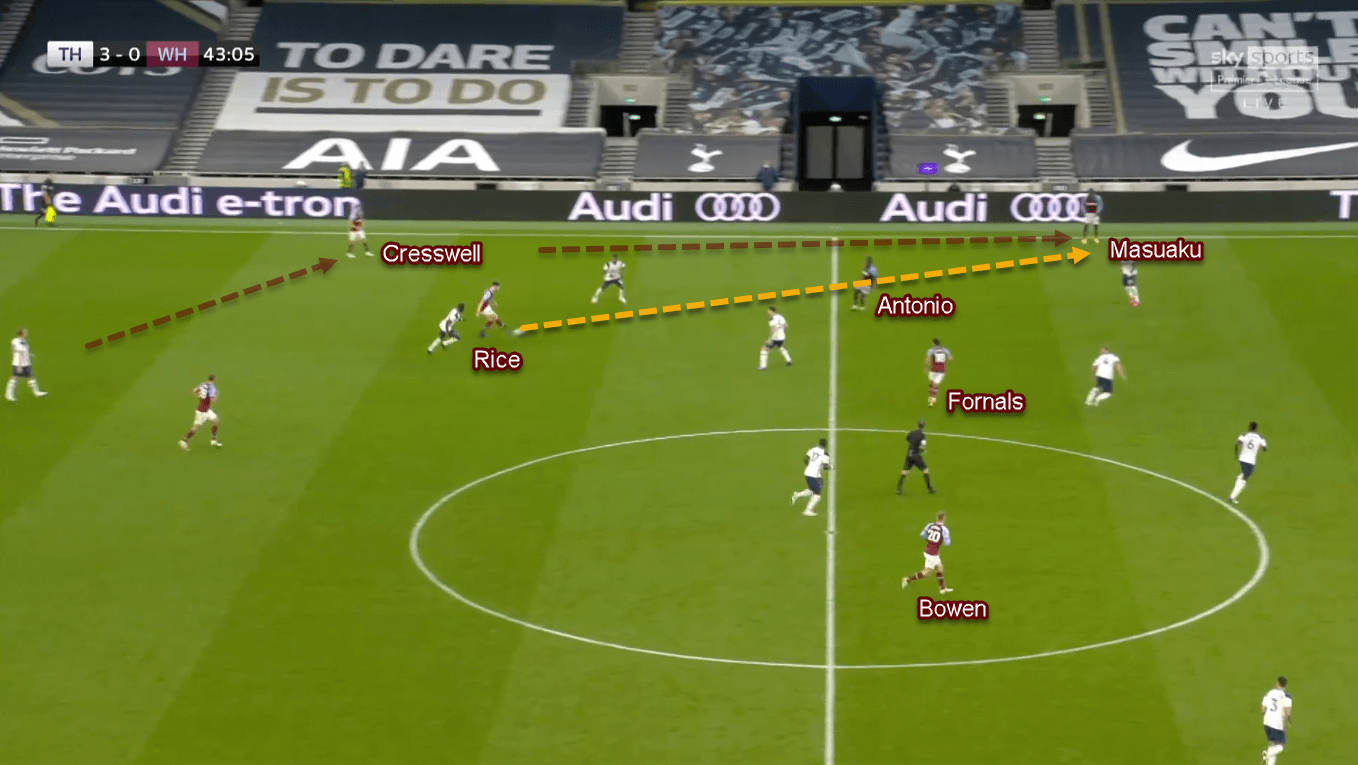

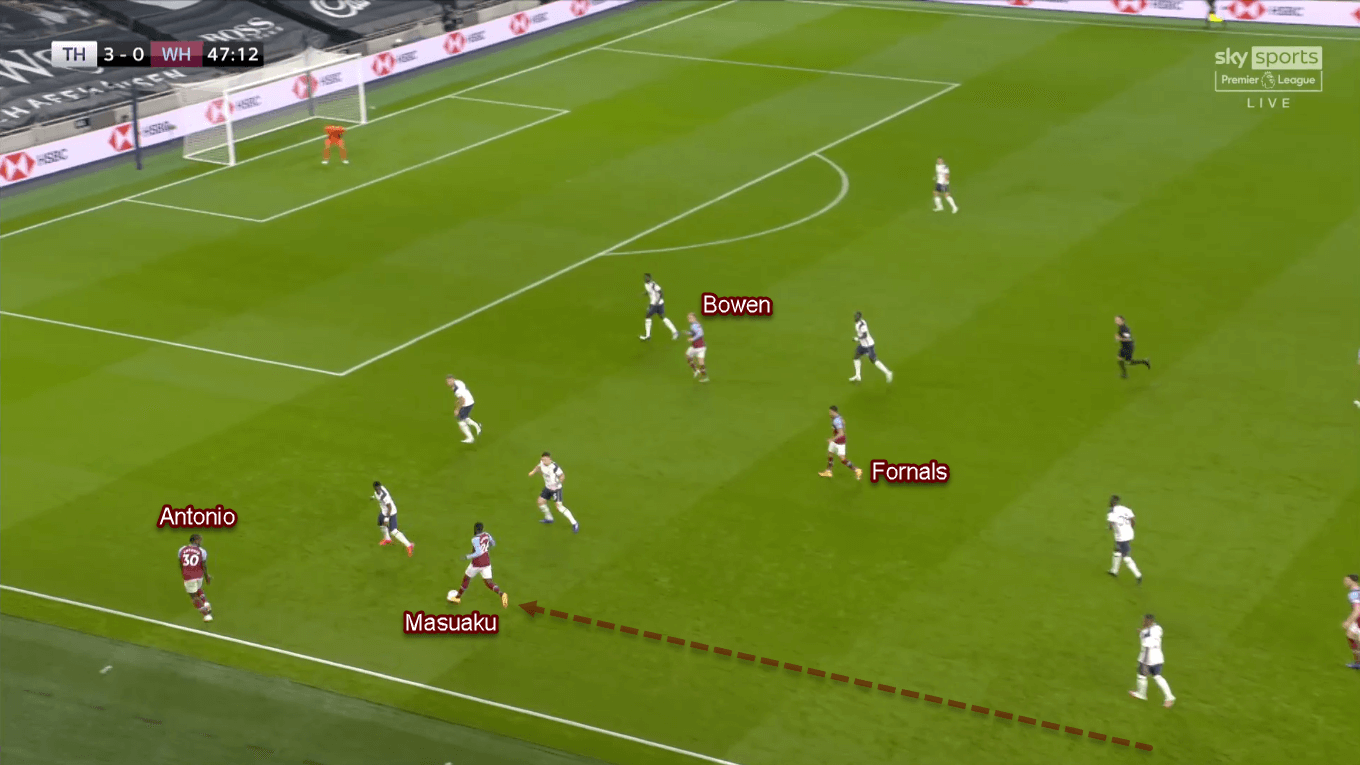

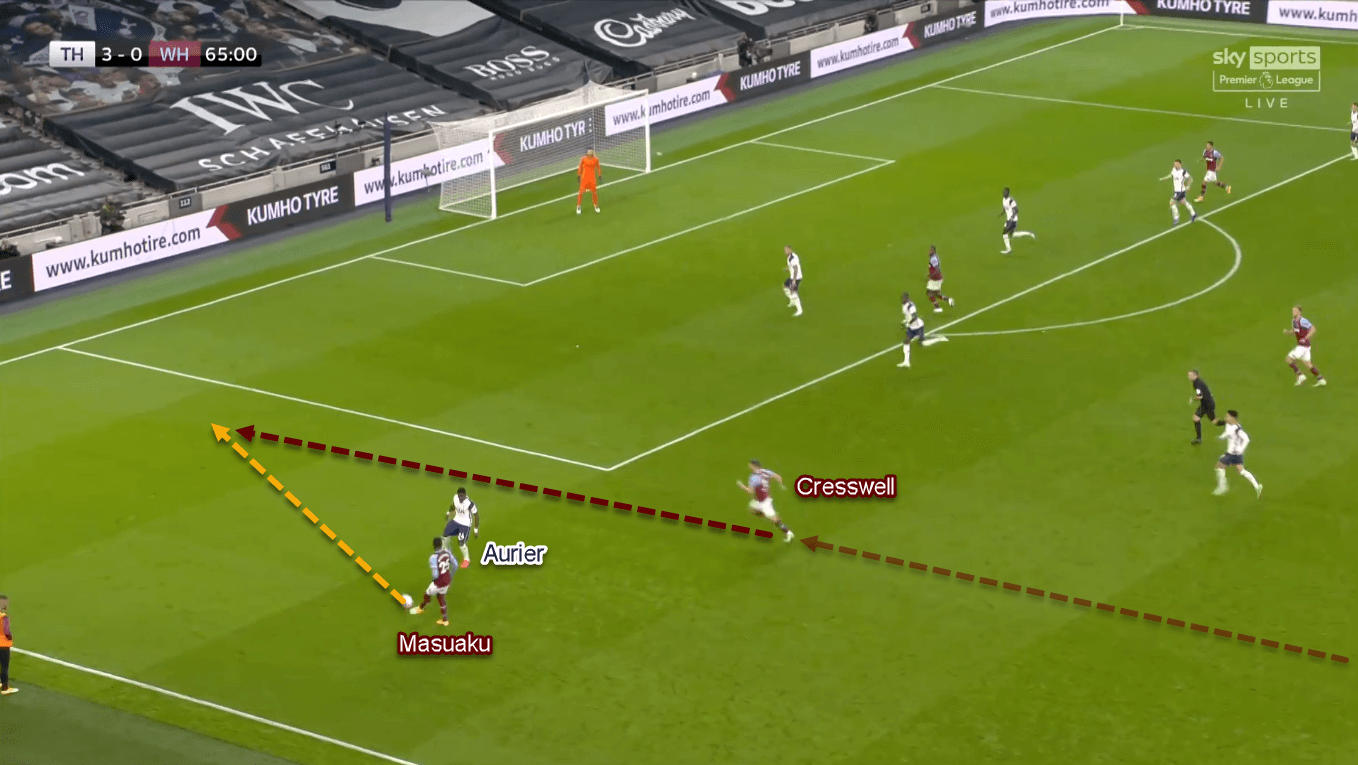

Structure-wise, West Ham moved from 5–4–1 to a 4–2–3–1/4–2–4-ish shape when attacking. In that shape, left wing-back Masuaku would step up and join the forwards while the remaining defenders shifted accordingly to cover his vacated space. As expected, he was utilised quite heavily to create chaos in Spurs’ right flank.

West Ham didn’t waste a lot of time in their attacks. Usually, they would try to find Masuaku quickly in the left flank, before the wing-back immediately distributes the ball to the attackers in behind. To be more specific, his passes were targeted to the half-space, so the attackers would have more space upon receiving. After that, the Hammers would try to send hard crosses to the far-post to create chances.

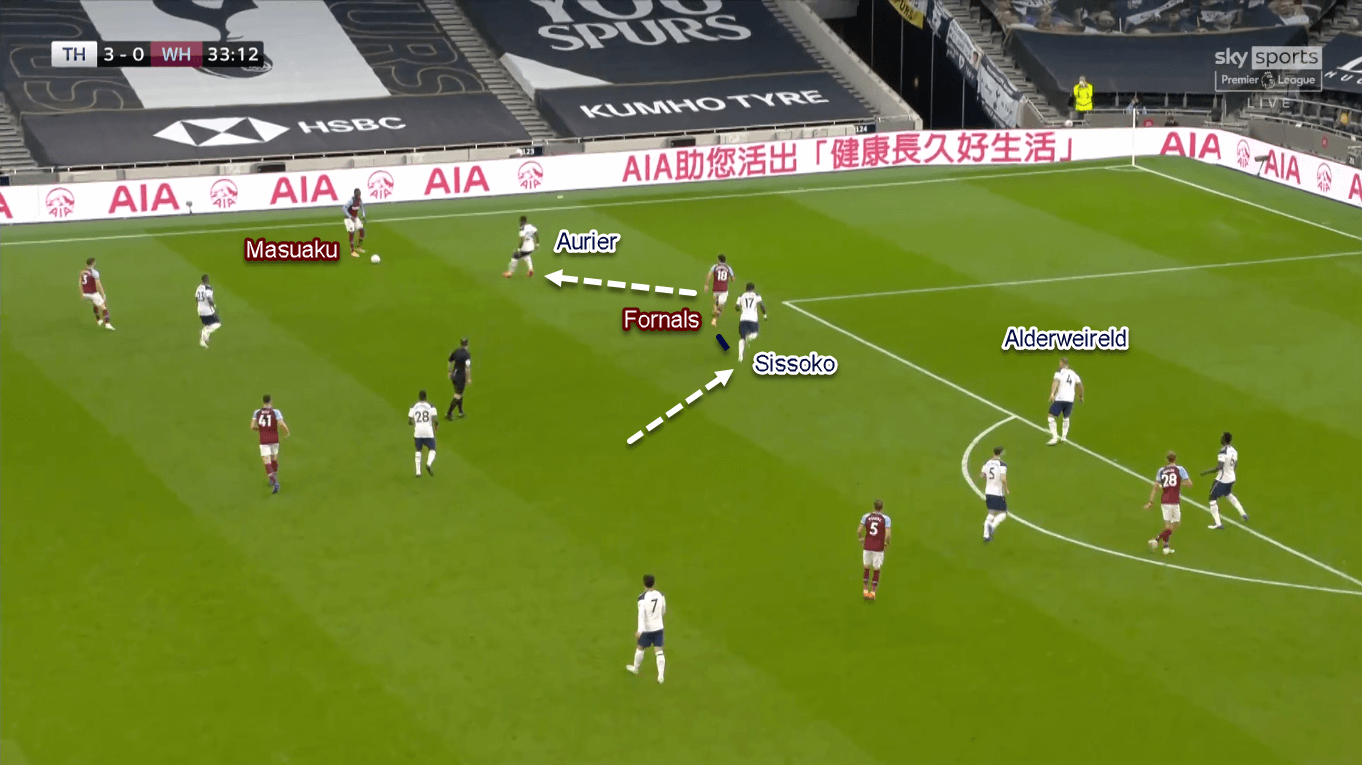

Oppositely, Tottenham kept their 4–2–3–1 when not having the ball. To counter the flank threats, Mourinho would usually ask the ball-side full-back to step up and press the on-ball opponent. The vacated space by the full-back then would be filled mainly by the nearby defensive midfielder; who has dropped from his area. If the midfielder wasn’t close enough, the nearby centre-back could also shift a bit from his position to cover the space.

Successful second-half adjustments from the visitors

West Ham’s average possession rate spiked up from 41% to 55% after the break. However, they kept the same attacking rate from the earlier half, with 0.47 attacks per minute. What happened behind the inspiring comeback?

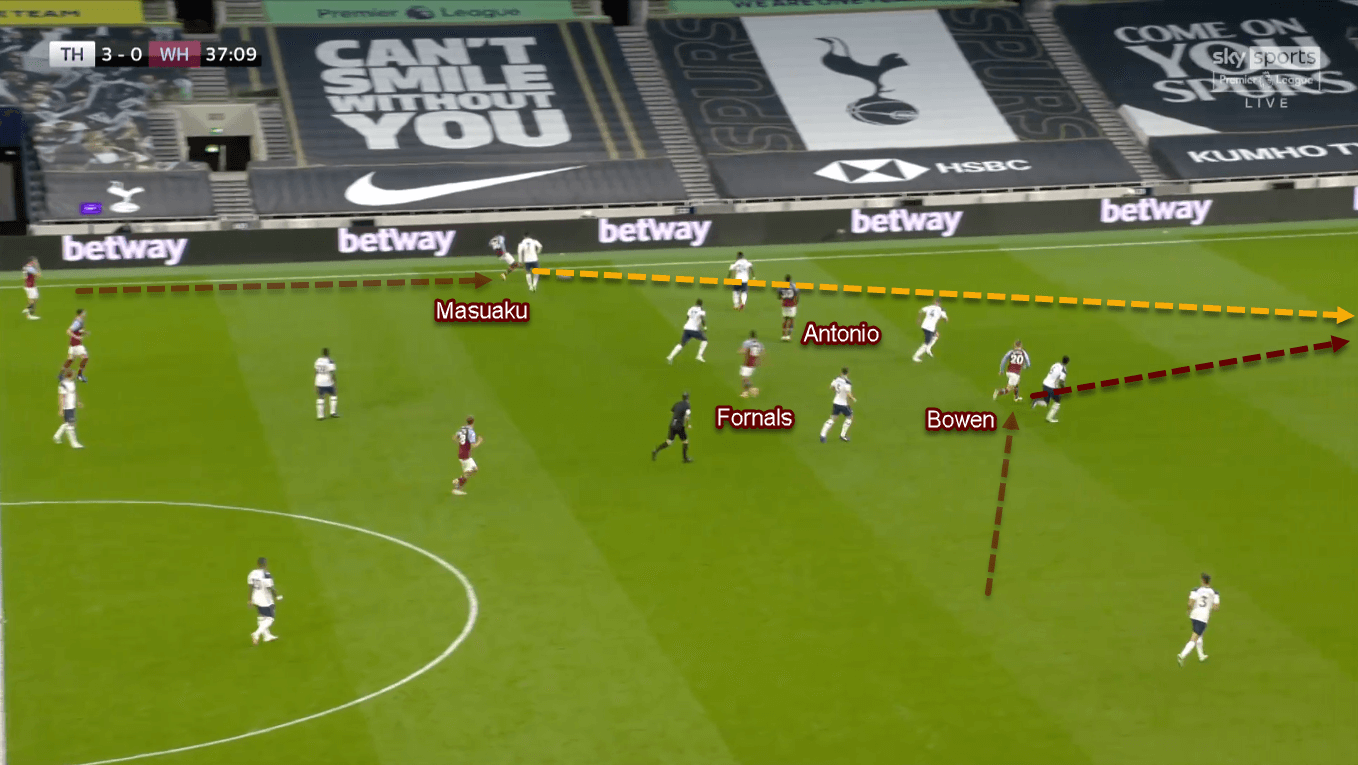

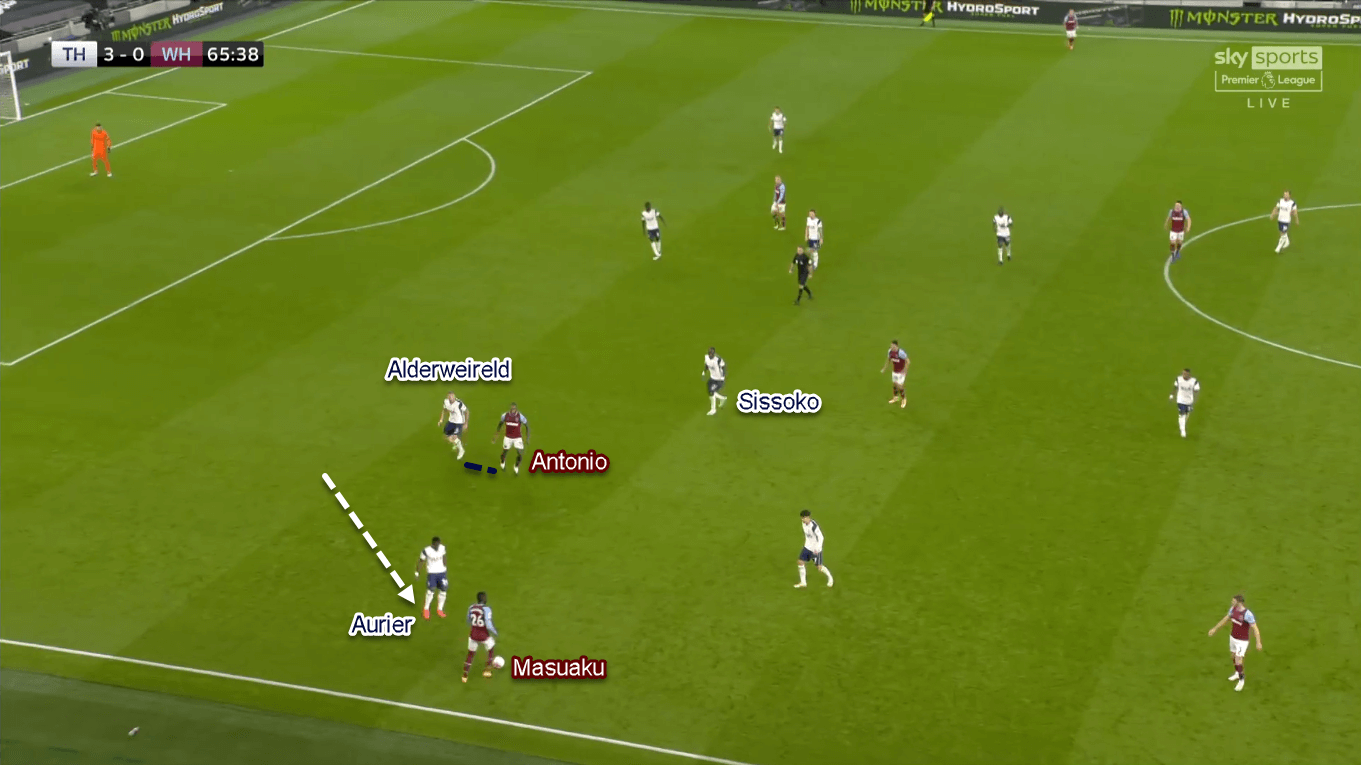

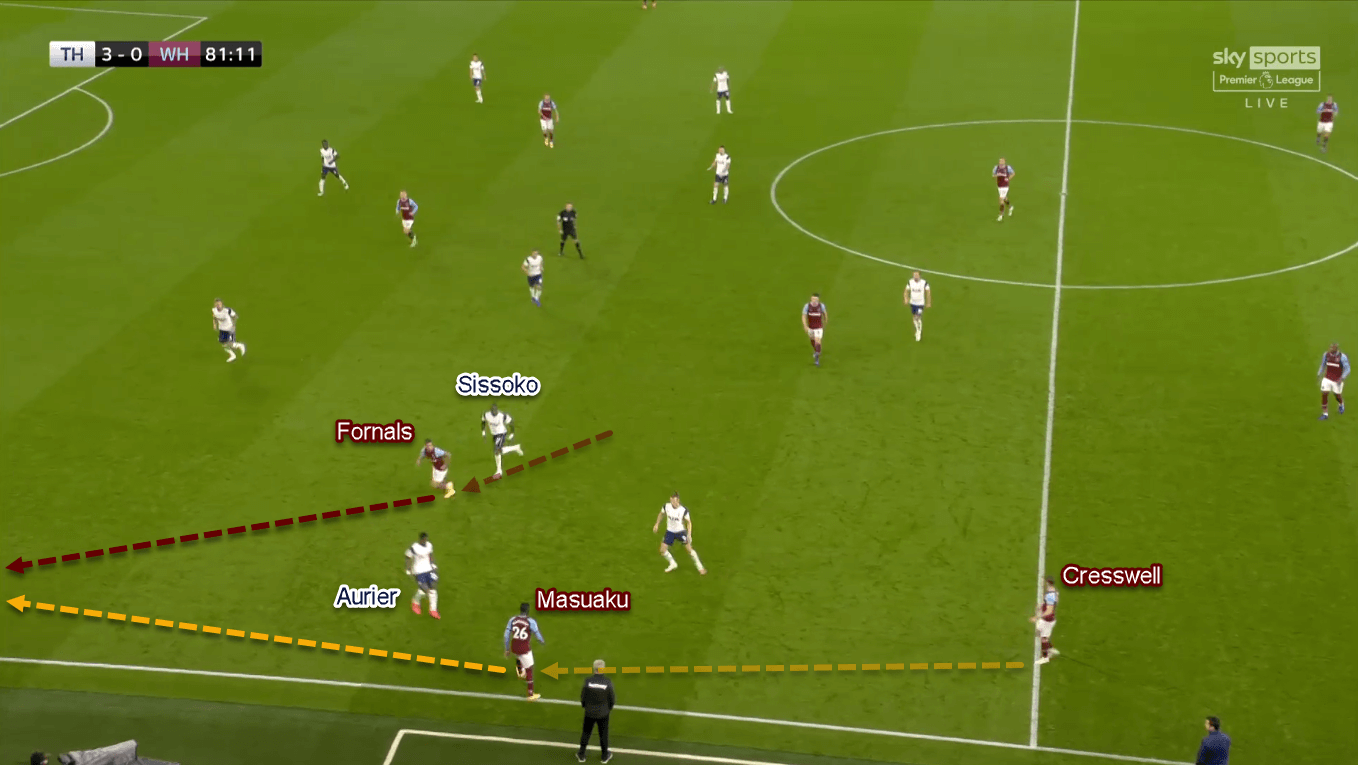

In the second half, the Hammers were more patient with the ball. That means they would try to bring more players in front of the ball first rather than quickly penetrate like in the first half. Their attacking structure was similar — 4–2–4-ish shape — but now Moyes allowed his wing-backs to be more adventurous than before.

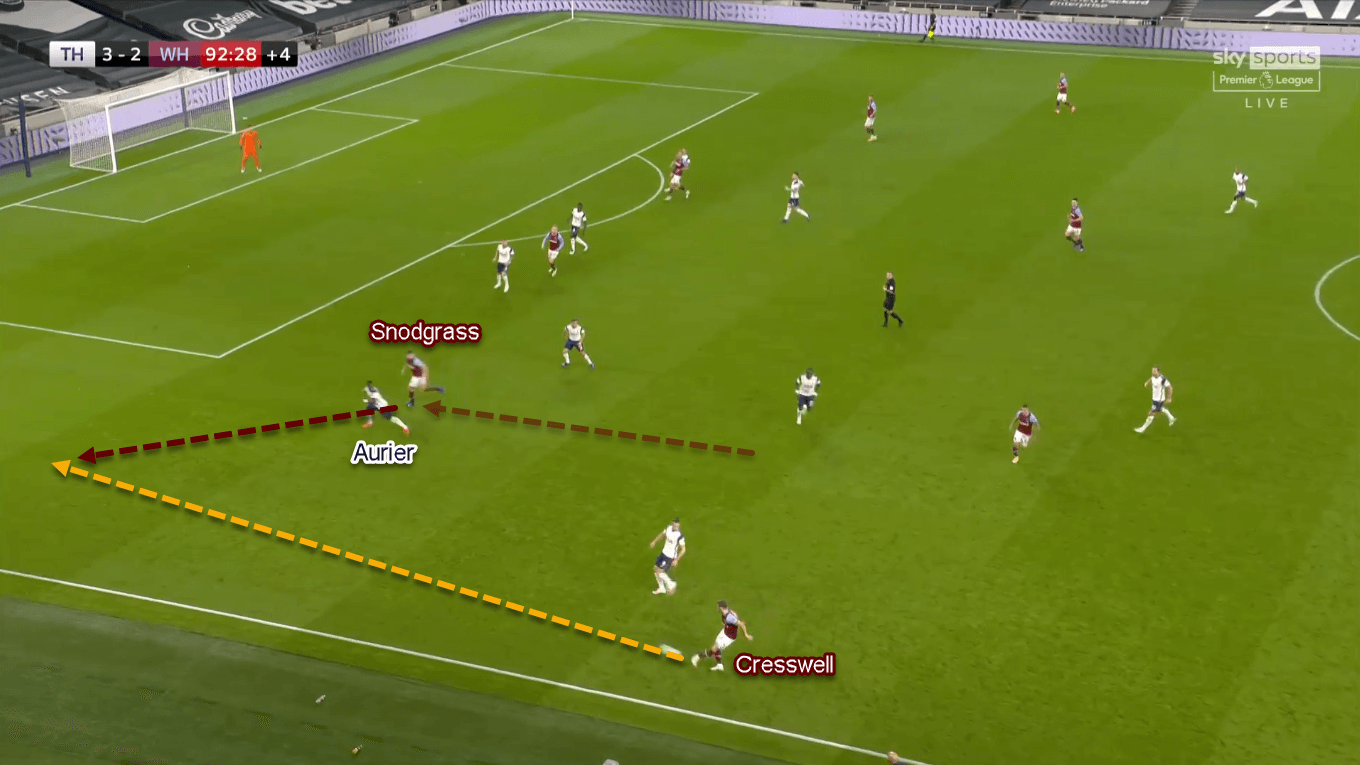

The visitors’ attacking plans in the second half relied more on overloading the flank. The stats even showed that 35 (76.08%) West Ham’s attacks came from wide areas. In the process, they would try to exploit the space left by Spurs’ full-back when the rivals tried to press West Ham on the flank.

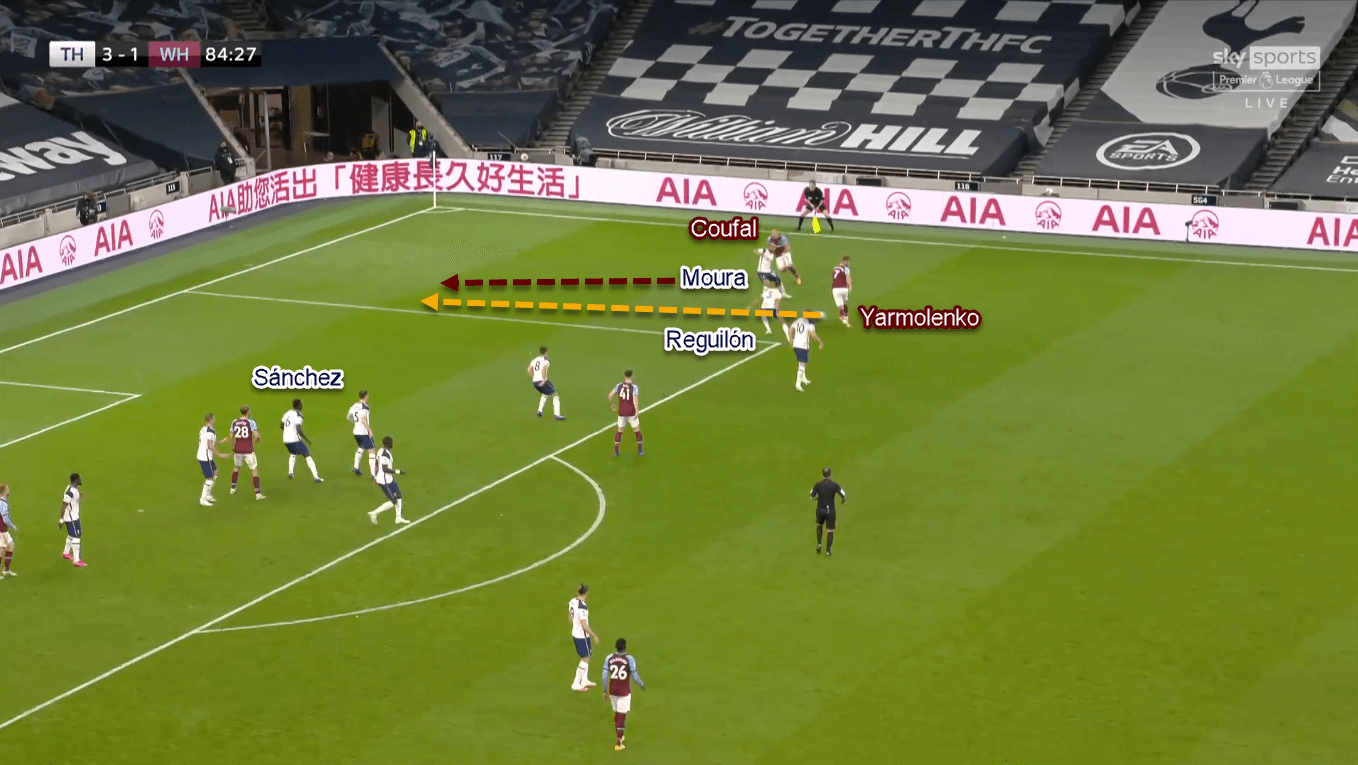

There was a notable difference in their wide-area approach, though. That was by allowing the wingers to distribute the passes in behind, as well as allowing the defenders — namely Coufal and Cresswell — to make penetrating runs before sending crosses inside the box. Such rotations made West Ham somewhat more unpredictable in the wide areas. For a fact, all West Ham goals were started by successful combinations in the flank.

Final thoughts

To say Mourinho got his tactics wrong was a huge mistake. He successfully set his team up to make three goals in the opening quarter-hour; a great start by any standard. In the second half, he helped his man to create six shots; one more than the previous half. Those included Kane’s denied-by-the-post attempt and Bale’s close-range miss in the stoppage time. Had (at least) one of them went in, the hosts would surely finish the weekend with three points in their bag. Unlucky.

Oppositely, to say Moyes’ men were fortunate didn’t do them justice either. The manager realised his mistakes early and quickly adjusted his defensive tactics to prevent bigger humiliation. After the break, his substitutes were spot on, with all of them contributed to the goals; directly or not. West Ham could even go home with a win if Fornals didn’t miss a golden chance just five minutes after the break.

To close this, we can only give praise and appreciations to both teams and managers for such a thrilling display. What a superbly brilliant match. Imagine not loving football, eh?

Comments