Wolverhampton Wanderers hosted Newcastle United last weekend. Their previous three encounters in the Premier League ended in an identical scoreline: 1–1. The last time it happened was between 2003 and 2010, when both teams yoyo-ed between top-flight football and the Championship or lower. Funnily enough, last Sunday’s match ended in another 1–1. It means that neither of them have beaten each other in a league match since December 2018.

The match was dull, to be fair. This was somehow expected, though, due to both teams’ nature to rely on counter-attacks rather than aggressively attacking for the majority of the game. In terms of expected goals (xG), Wolves just made 0.88 from 15 attempts, while Newcastle only got 0.41 from five shots. This tactical analysis will examine the tactics both teams used and how they influenced the outcome of the match.

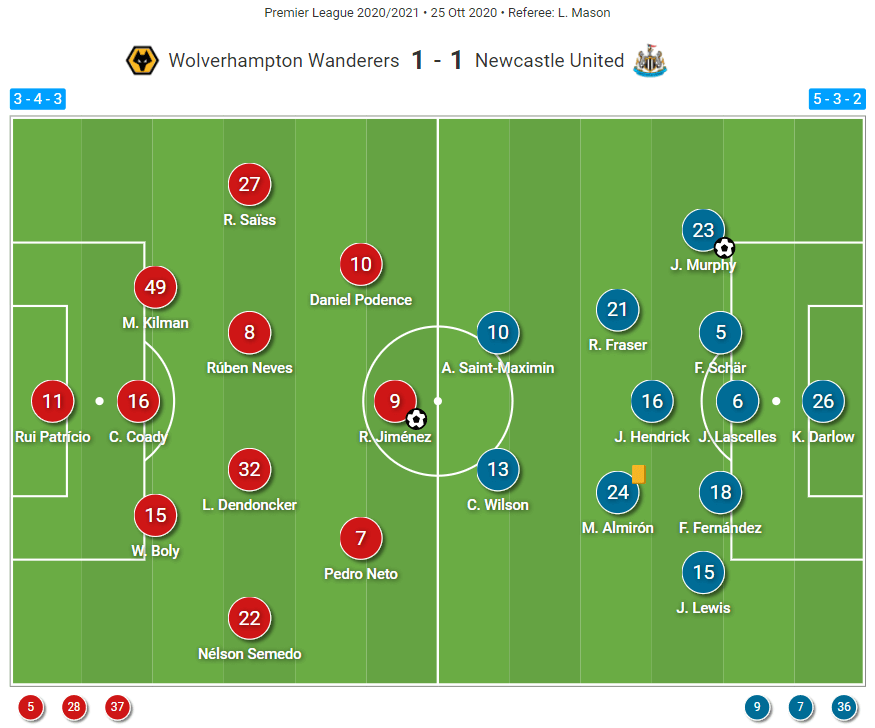

Lineups

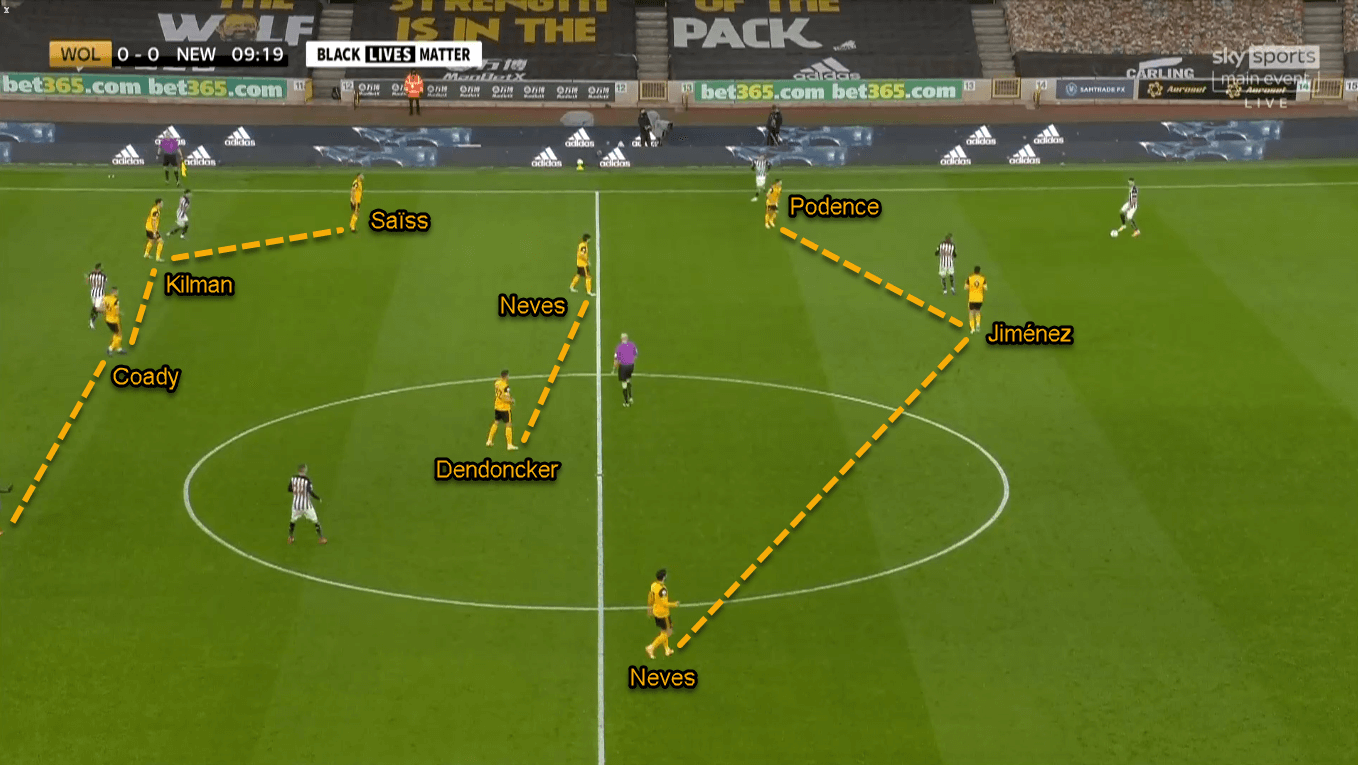

Nuno Espírito Santo opted for his preferred 3–4–3 in this game. The trio of Willy Boly, Conor Coady, and Max Kilman started at the heart of the defence while Nélson Semedo and Romain Saïss gave support from the flanks. Up top, talisman Raúl Jiménez led the attack and flanked by the duo of Pedro Neto and Daniel Podence. Wolves’ bench was filled with names like Fernando Marçal, João Moutinho, and former FC Barcelona man Adama Traoré.

In the opposite side, Steve Bruce went for 5–3–2. The midfield trio consisted of Ryan Fraser, Jeff Hendrick, and former Major League Soccer star Miguel Almirón. Up front, new recruit Callum Wilson was given the license to spearhead the attack alongside Allan Saint-Maximin. Players like Andy Carroll, Joelinton, and Sean Longstaff had to start the match from the dugout.

Newcastle’s defensive plans

This analysis will start by dissecting Newcastle’s defensive tactics. When they conceded possession, Newcastle would defend in a mid-block 5–3–2. The main objectives of this shape were to protect the central lanes and force Wolves to attack through the flanks. There was one interesting thing that can be found in Newcastle’s defensive block. That was their lack of compactness (mainly vertically), which gave Wolves so much space in between the lines to exploit. We’ll talk deeper about this later.

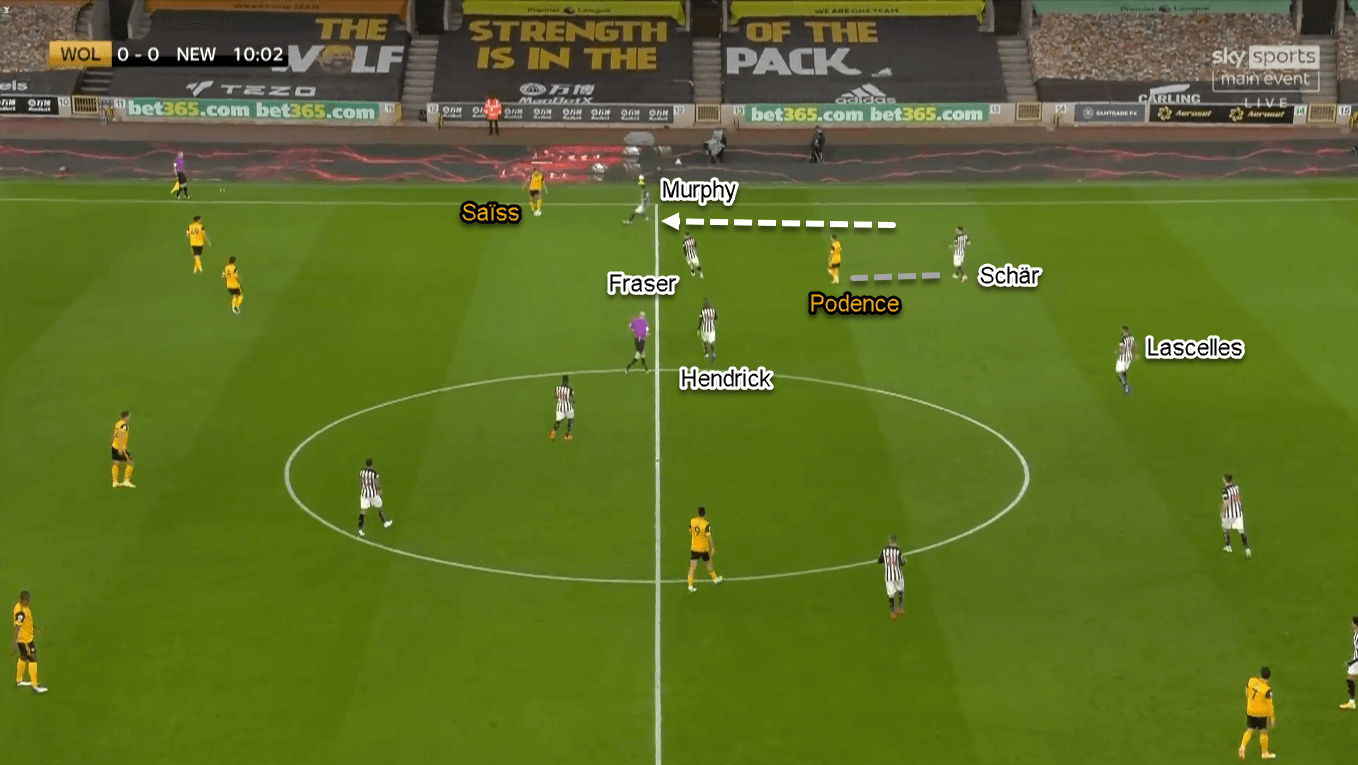

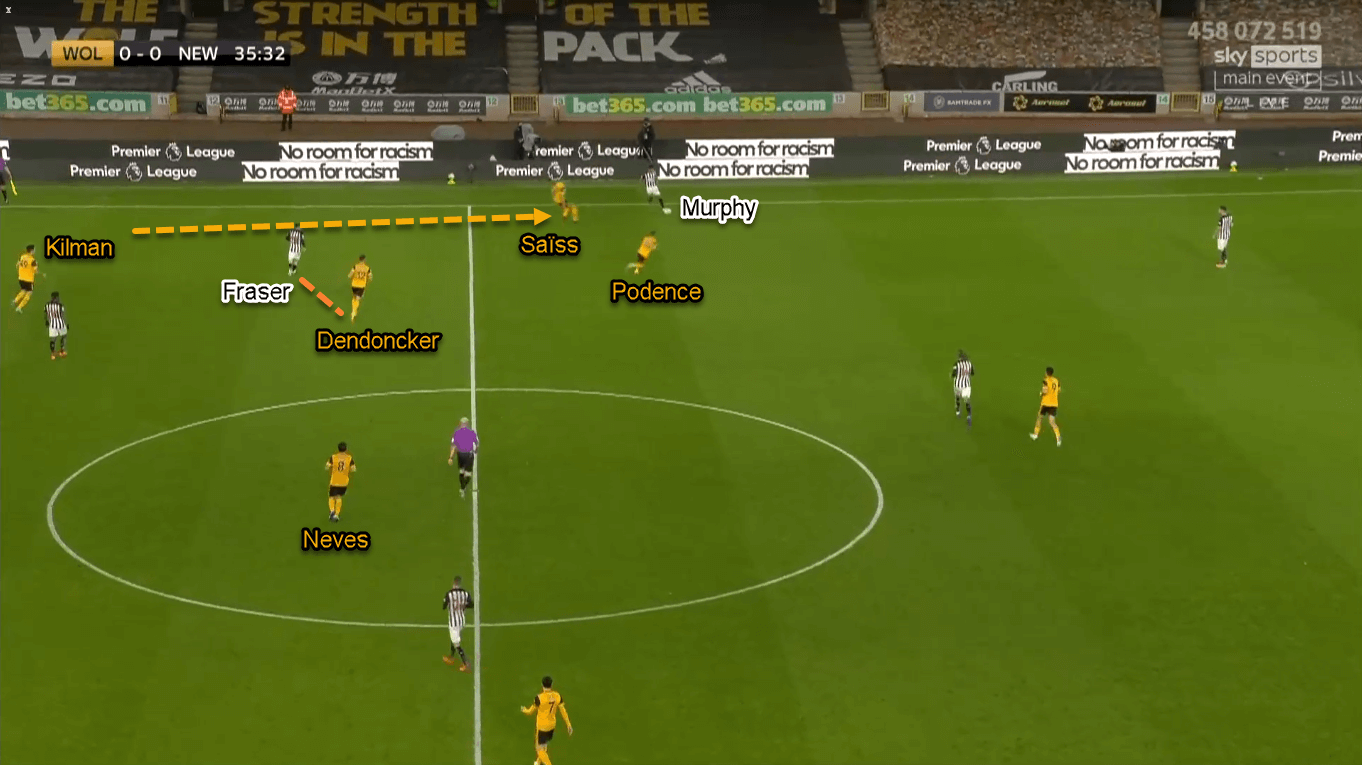

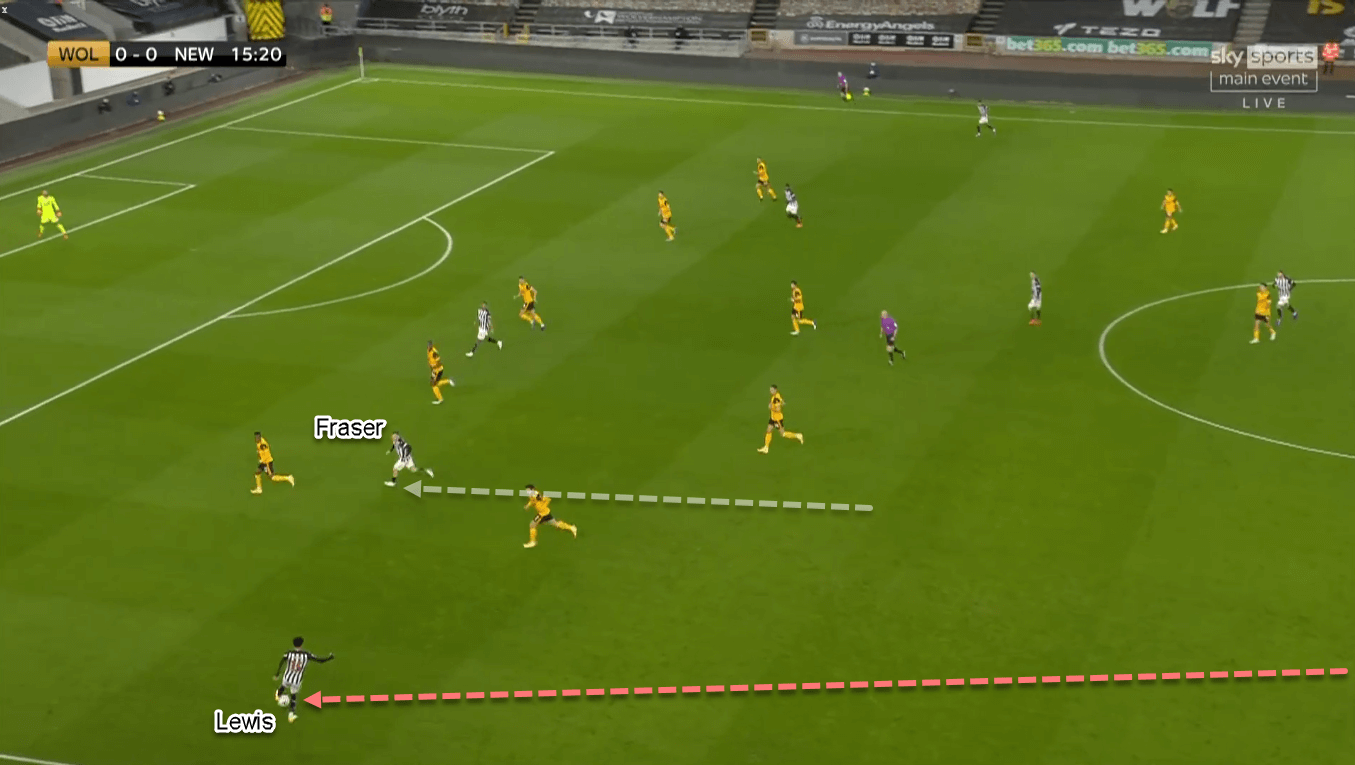

We already know that Newcastle would force Wolves to play through the flanks. But what did they do to contain the hosts there? There were two main options that the visitors used in this match, as follows:

First, by instructing the ball-side wing-back to come up from the backline and press the opponents’ flank player. This mostly happened in Newcastle’s right side, with Jacob Murphy pressing on Saïss because the latter wasn’t too aggressive in his positioning. Inside, Bruce asked the nearby central midfielder and/or centre-back to close the progressive passing option(s) for the Moroccan. In that way, Wolves were prohibited to penetrate through the defensive block easily.

Secondly, by instructing the ball-side midfielder to step wide from the midfield line and execute the press. At the same time, Newcastle’s ball-side wing-back would stay behind alongside his defensive partners. This mostly happened in their left flank, because Semedo tended to advance to the final third. Similarly, Newcastle also closed the inside progressive passing options for Wolves. This time they could use Hendrick and/or the nearby centre-back to do that.

Toothless Wolves (part one)

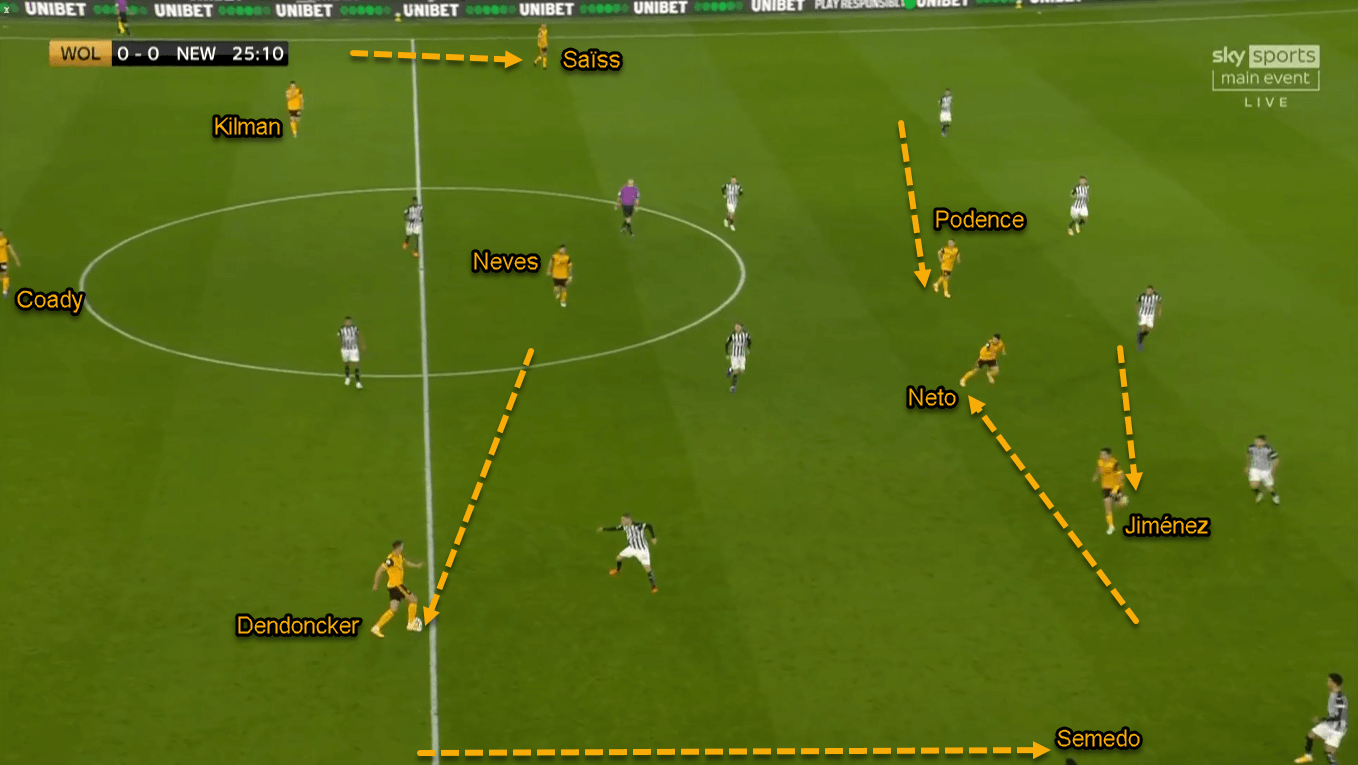

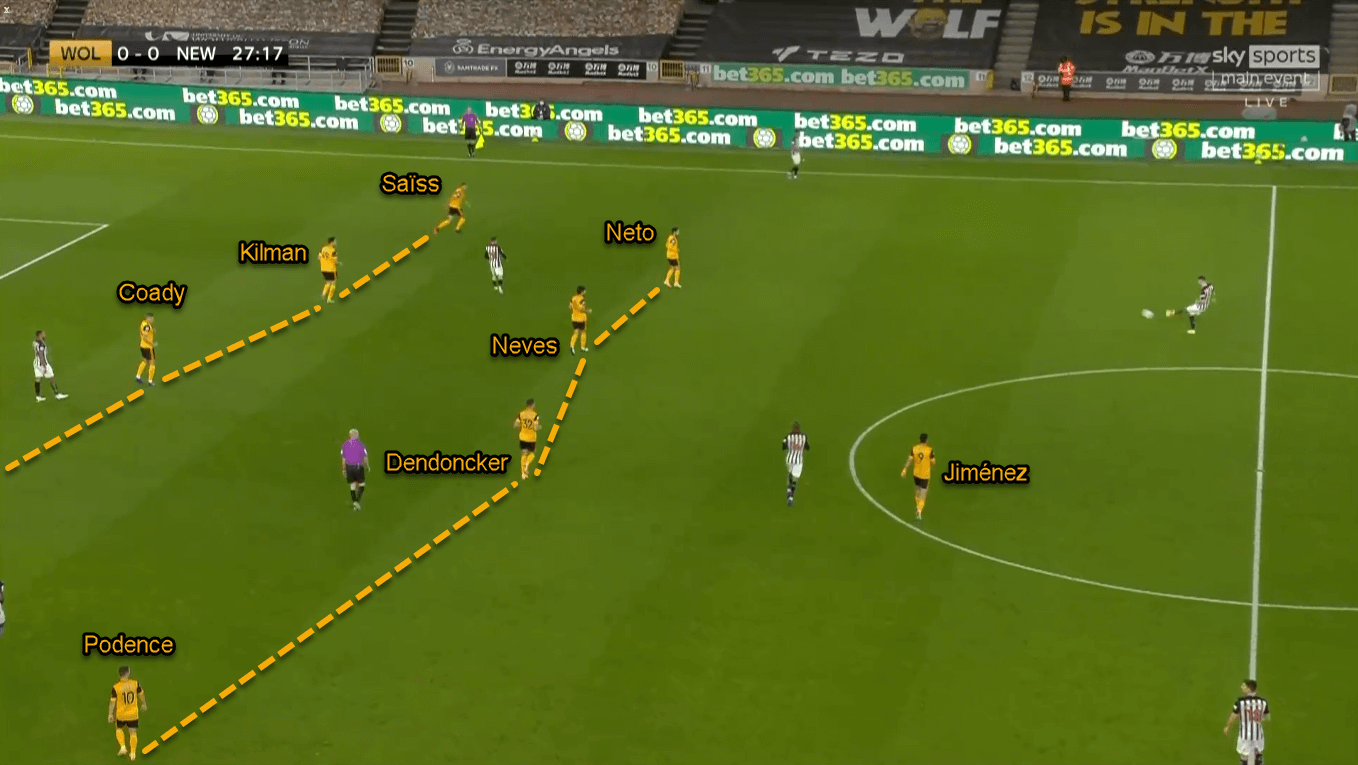

Wolves had the lion’s share of the ball with an average of 64% possession throughout the game. Structure-wise, they used a lopsided 3–4–3. In this shape, one central midfielder would often drift wide to the half-space. The objective behind this was to help Wolves overloading the flank in where the midfielder has dropped.

Next, the asymmetrical shape also happened because of the differing characteristics of the wing-backs. Left wing-back Saïss is originally a centre-back, hence the rather cautious positioning as mentioned. In the opposite side, Semedo was positioned further forward due to his attacking tendencies and ability.

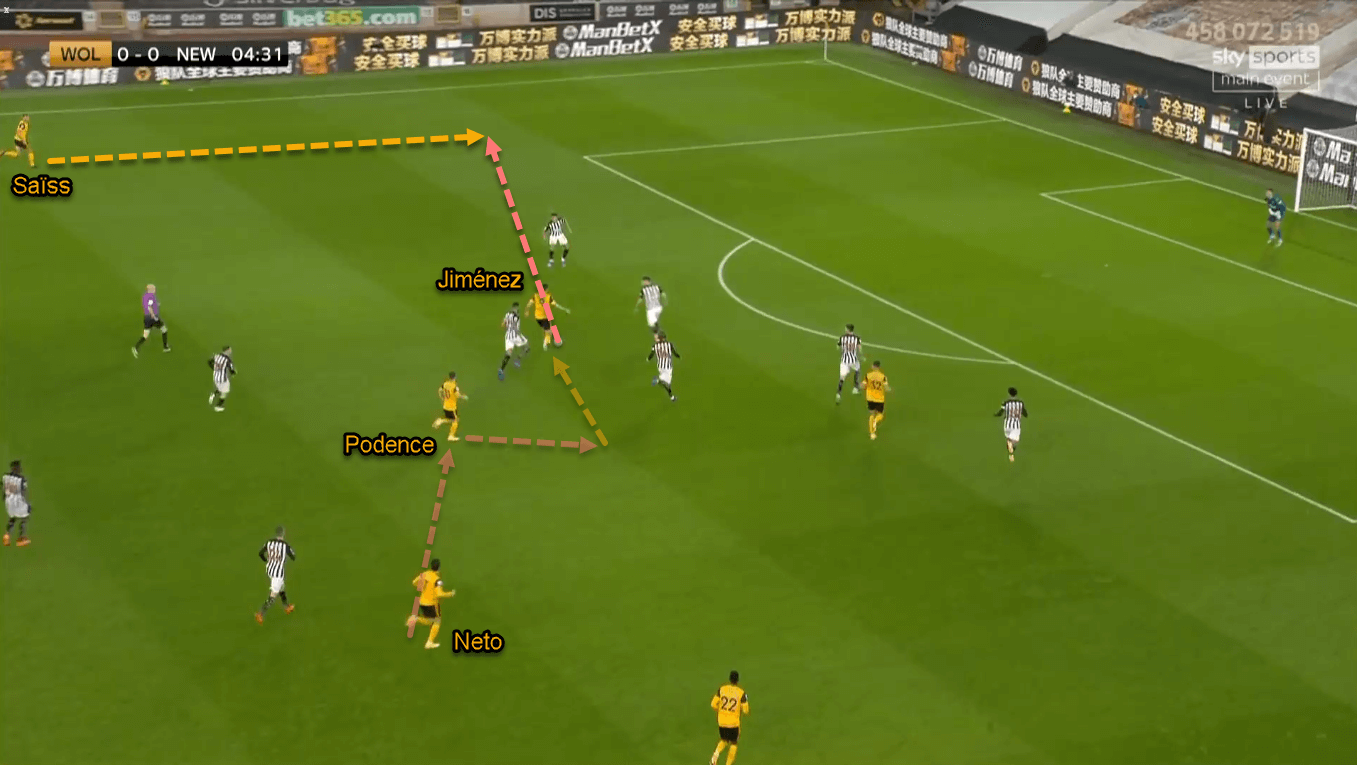

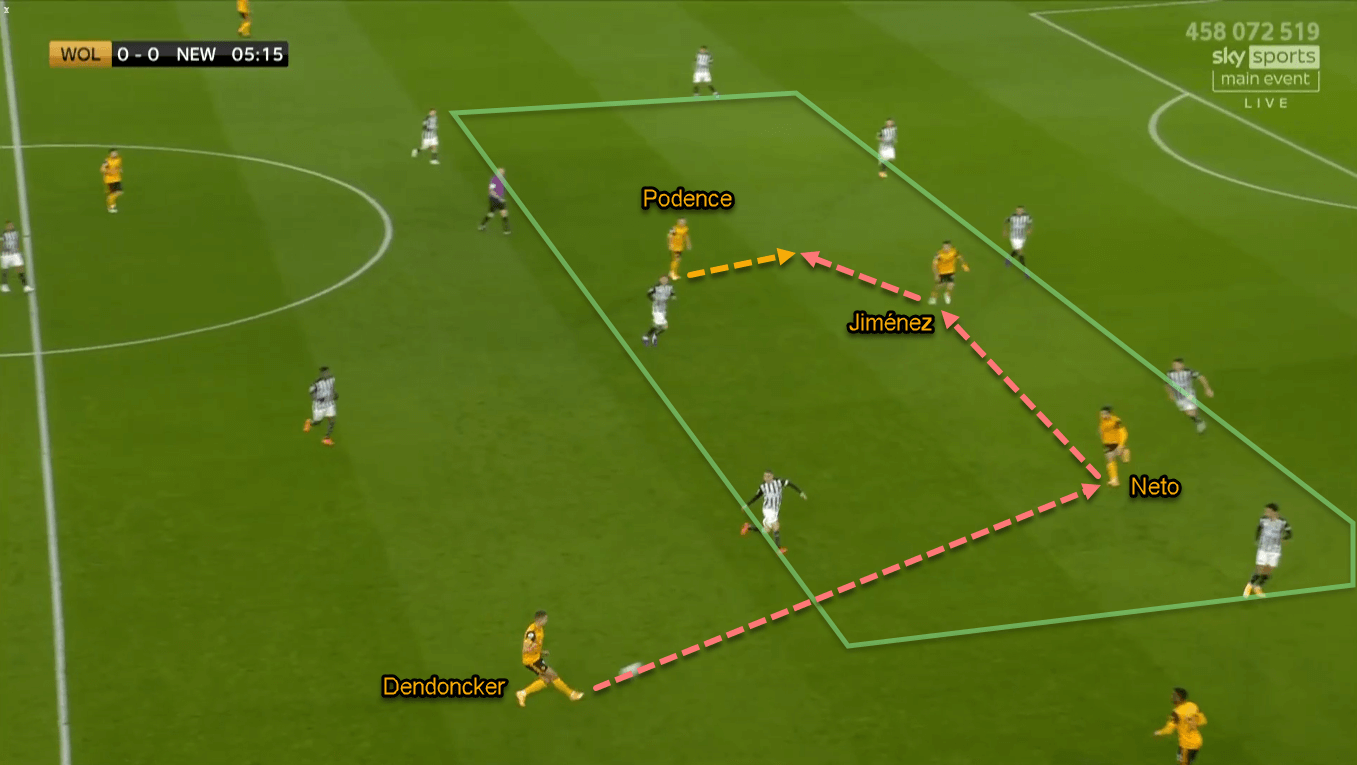

Last but not least, the forwards. The wingers — Neto and Podence — were mainly tasked to play inside to help Jiménez exploiting the space in between the lines. The trio was also given the freedom to rotate by Nuno. That’s because of their adeptness to play across the final third as well as their good on-ball quality.

Toothless Wolves (part two)

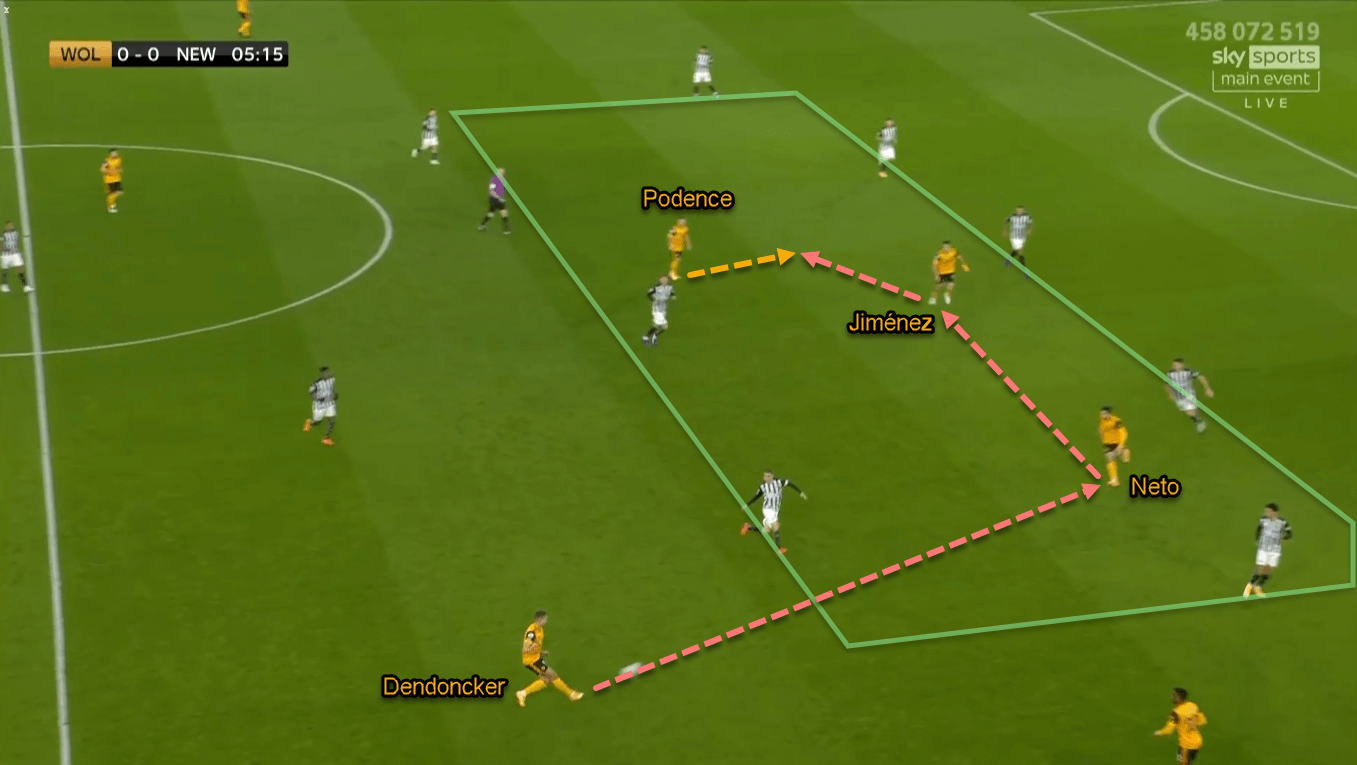

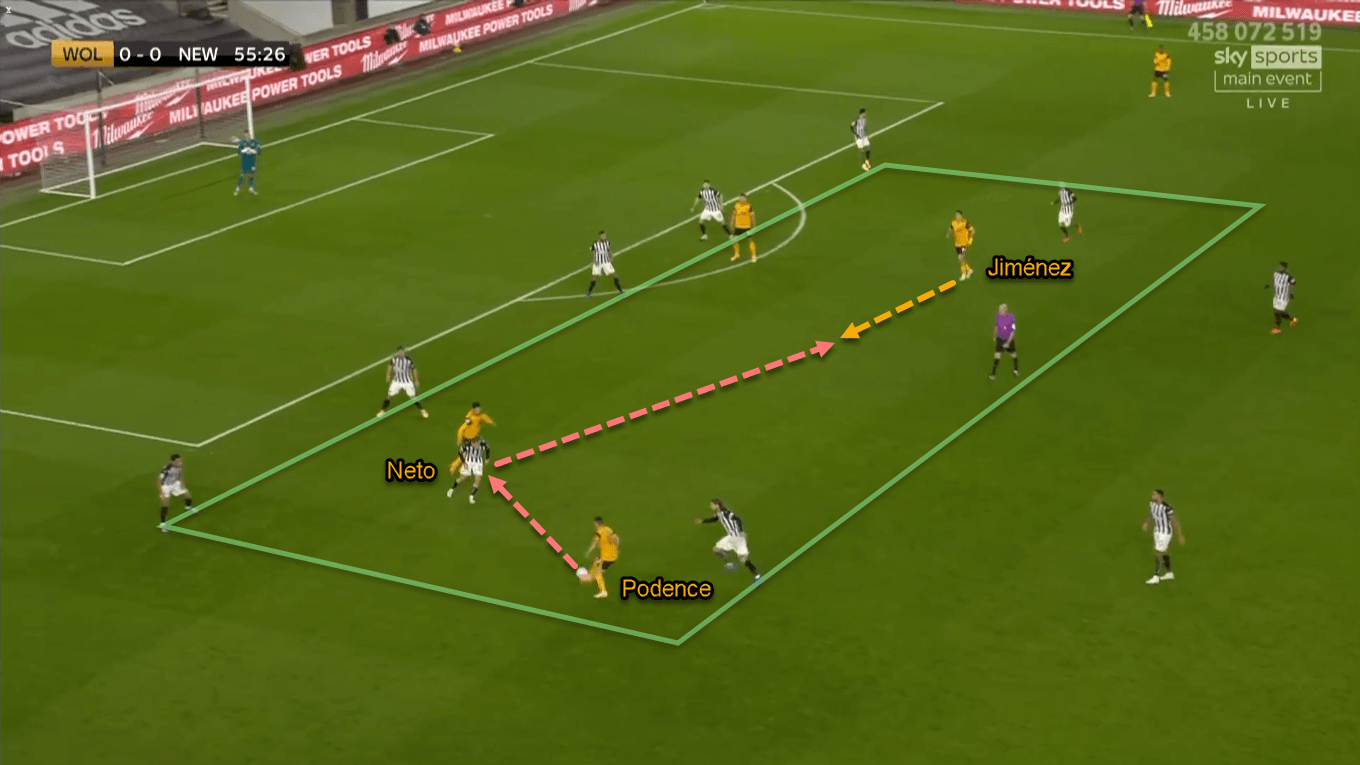

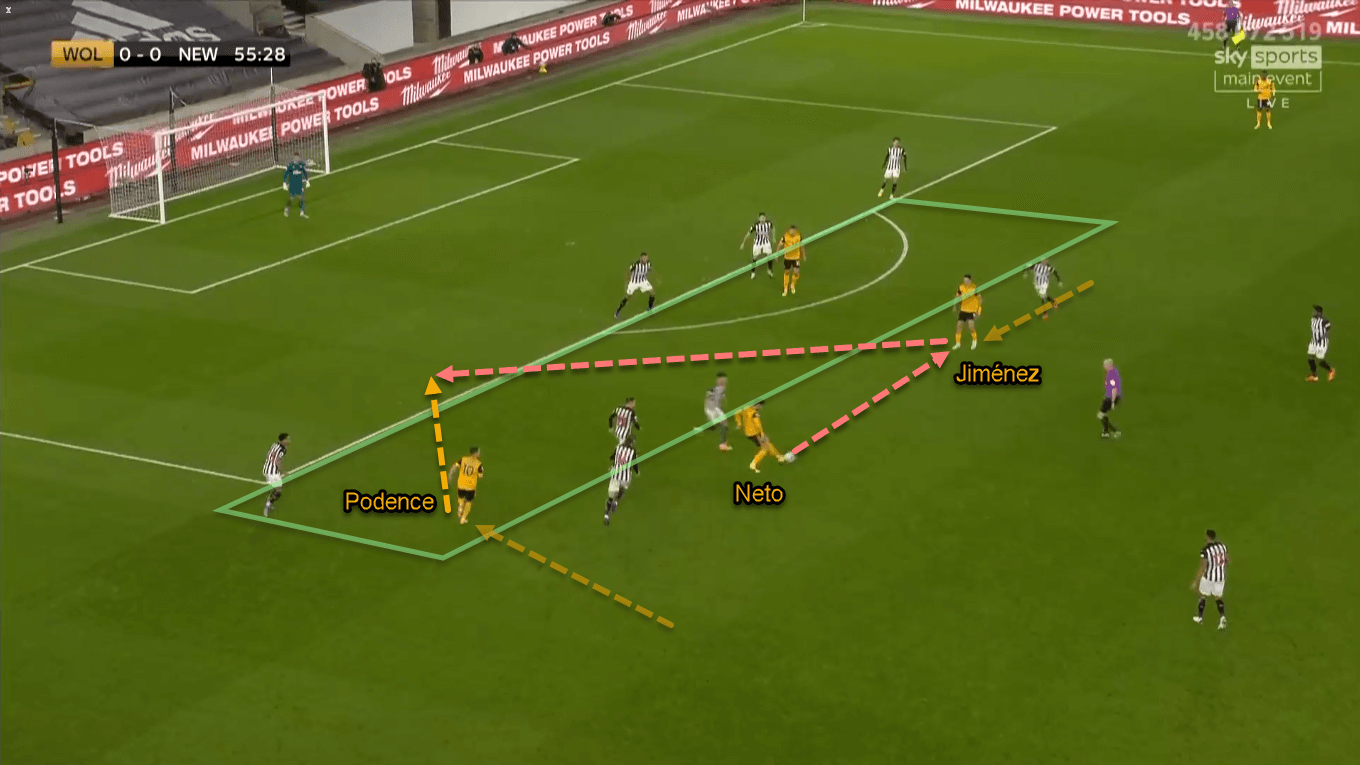

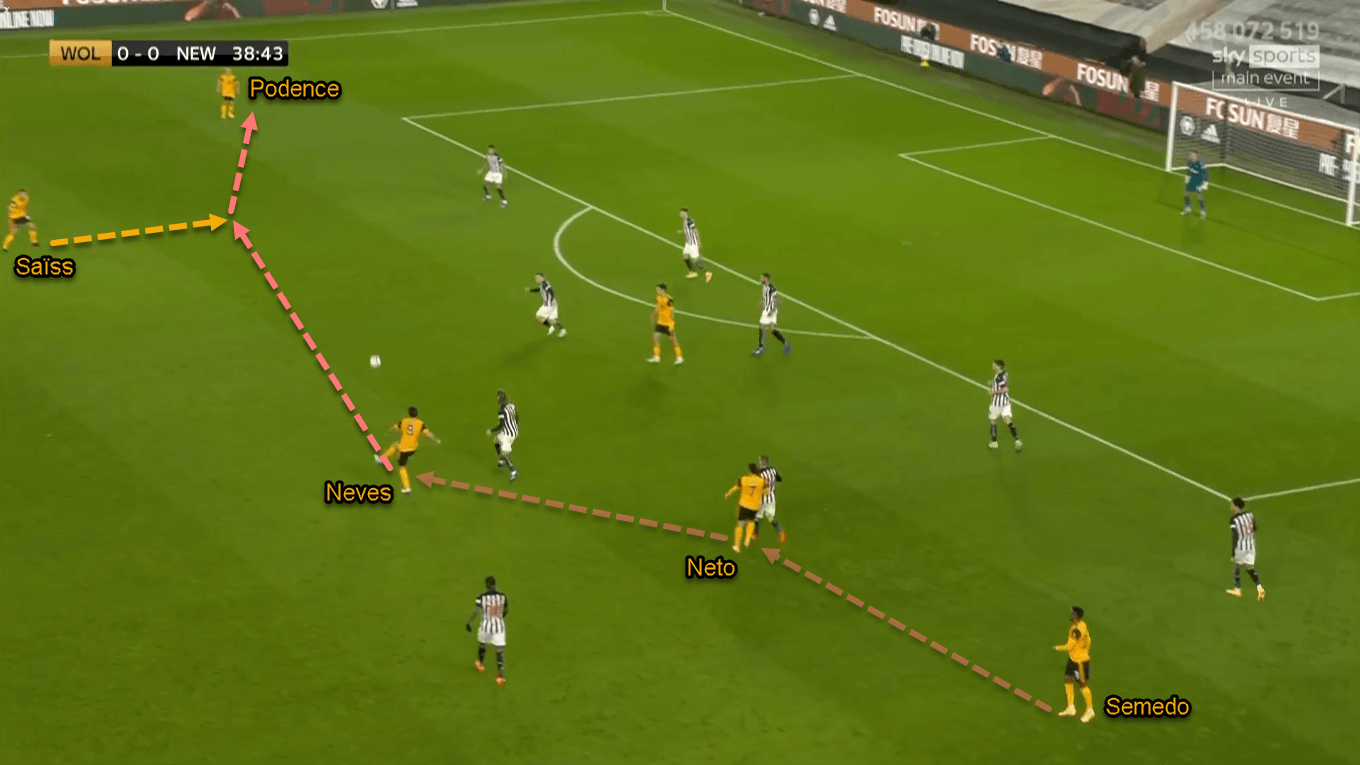

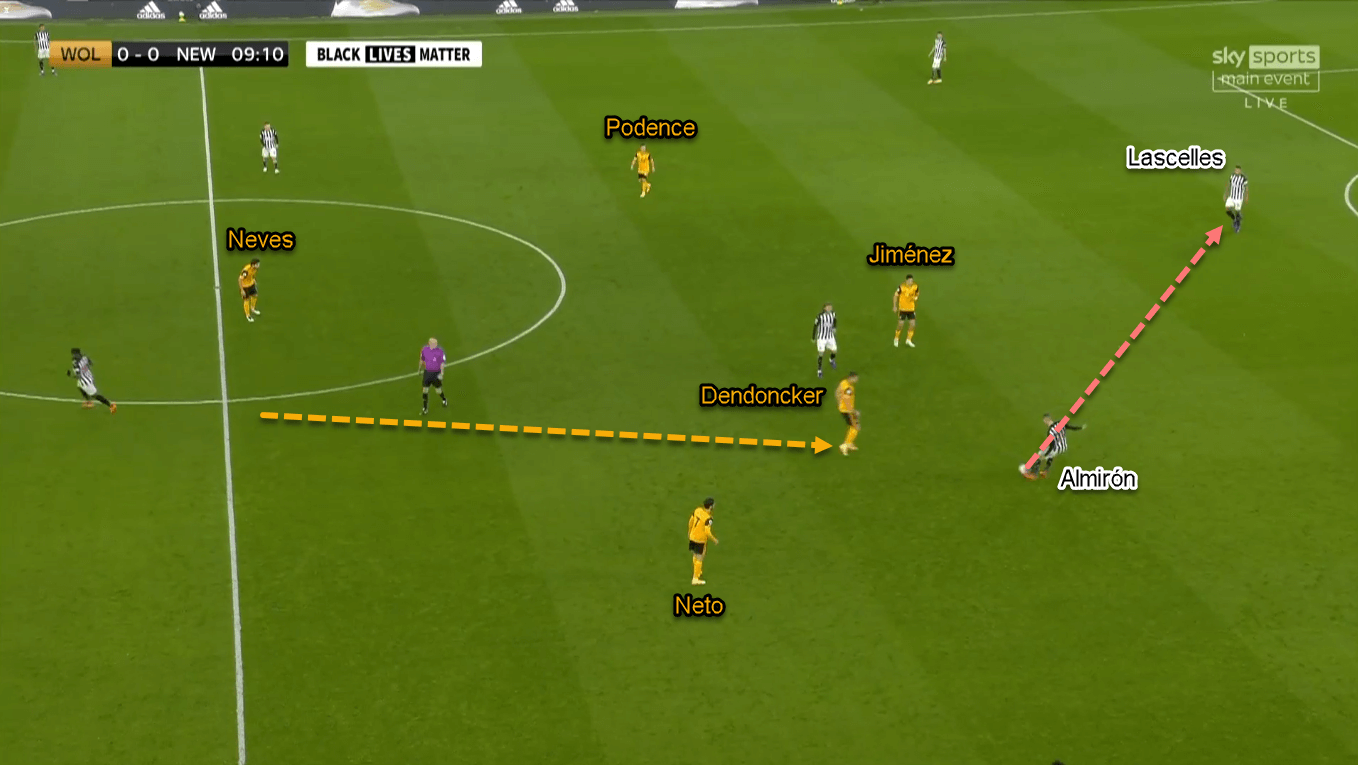

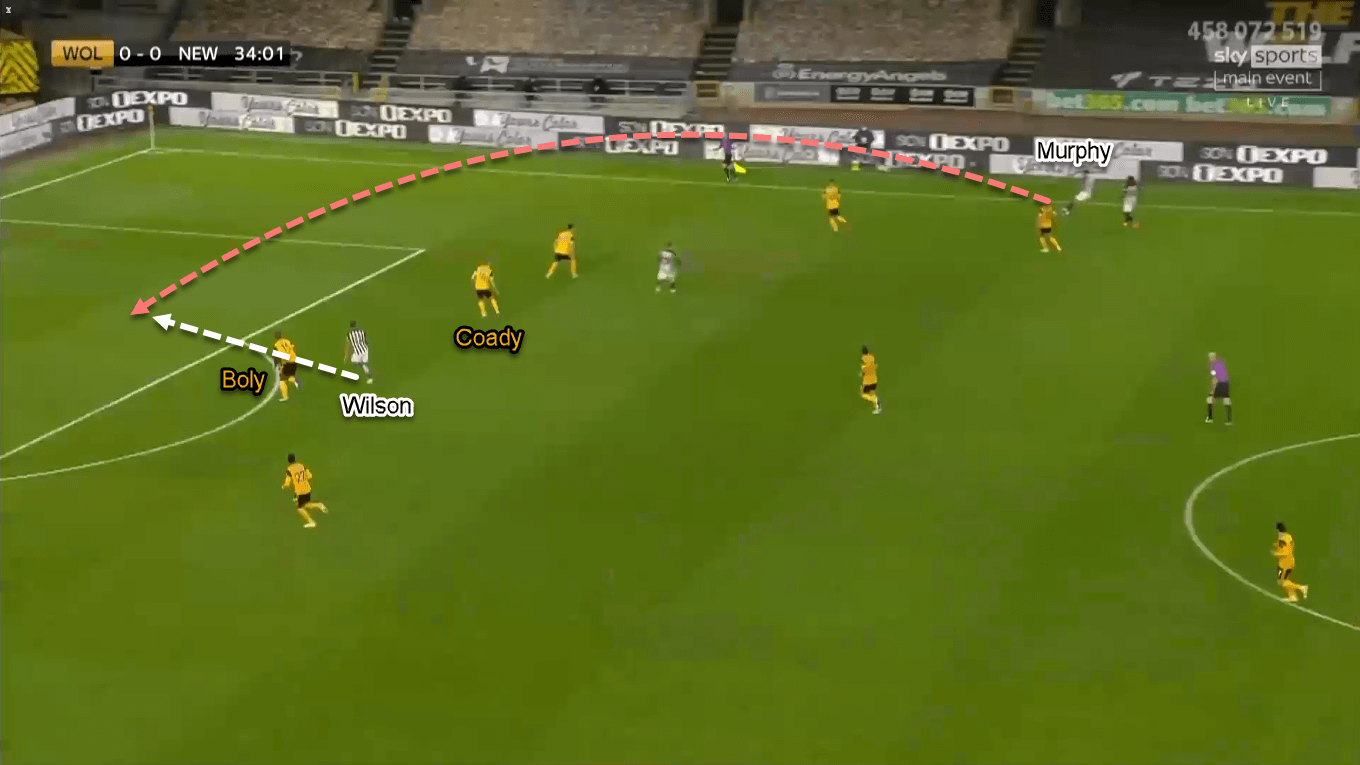

Wolves’ main idea in their attacks was to exploit the space in between the lines. Mainly, they started the move by sending ground diagonal balls from the flank to the inside space. After that, the attackers could combine swiftly before creating chances from outside the box.

Another way Wolves used after playing in between the lines was to play the ball to the opposite flank via short combinations. In this flank-to-flank approach, the hosts tried to disrupt Newcastle’s defensive department by moving the ball quickly across the pitch, forcing the visitors to be hardly organised. After the ball reached the other flank, the flank player then was tasked to send crosses into the box to the attackers inside.

However, Wolves didn’t threaten Karl Darlow’s goal often. The statistics showed that only four (26.67%) of the hosts’ shots that came from inside the box. Even worse, only one (6.67%) of their chances that was rated higher than 0.11 in terms of xG.

Wolves’ crossing approach wasn’t better either. If we look at the stats, Wolves only managed to complete five crosses in this game. That’s about 29.41% success rate from their 17 attempts. Toothless, indeed.

Strength in numbers

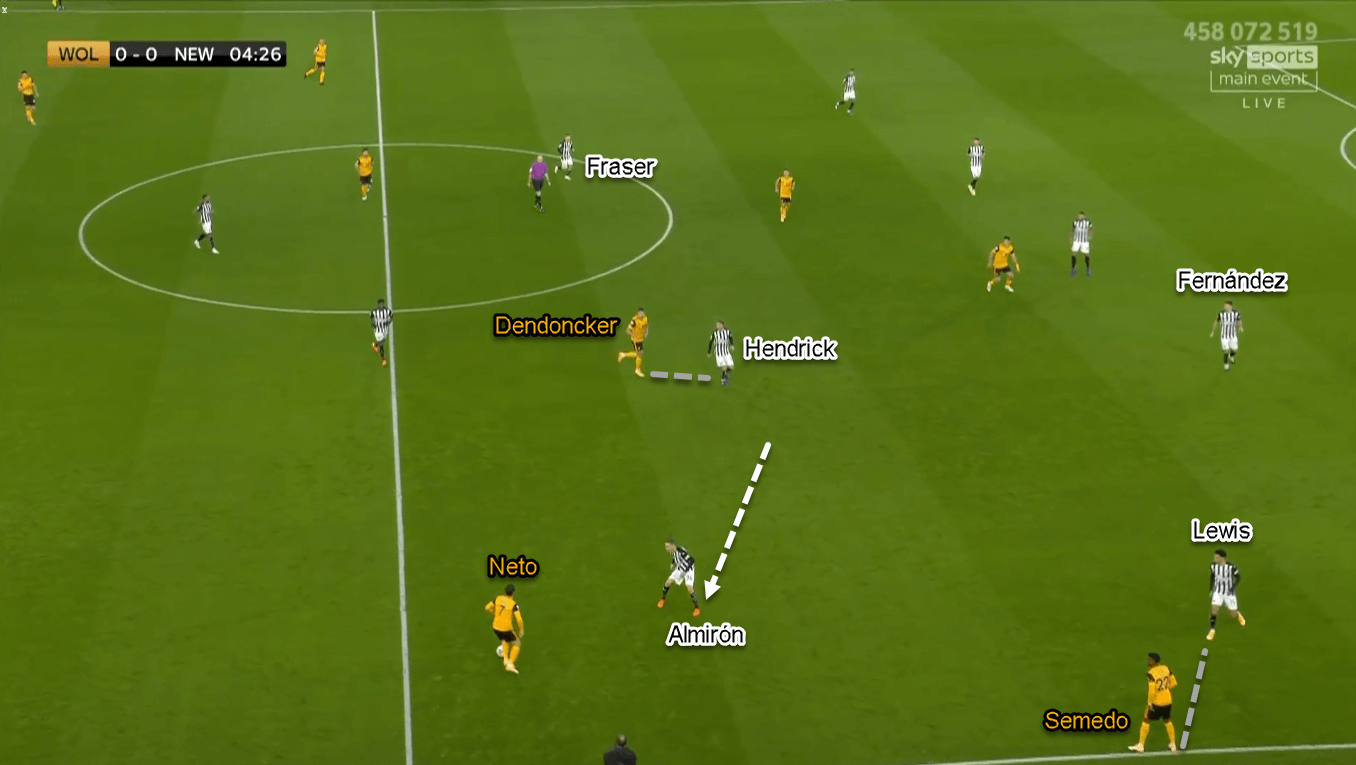

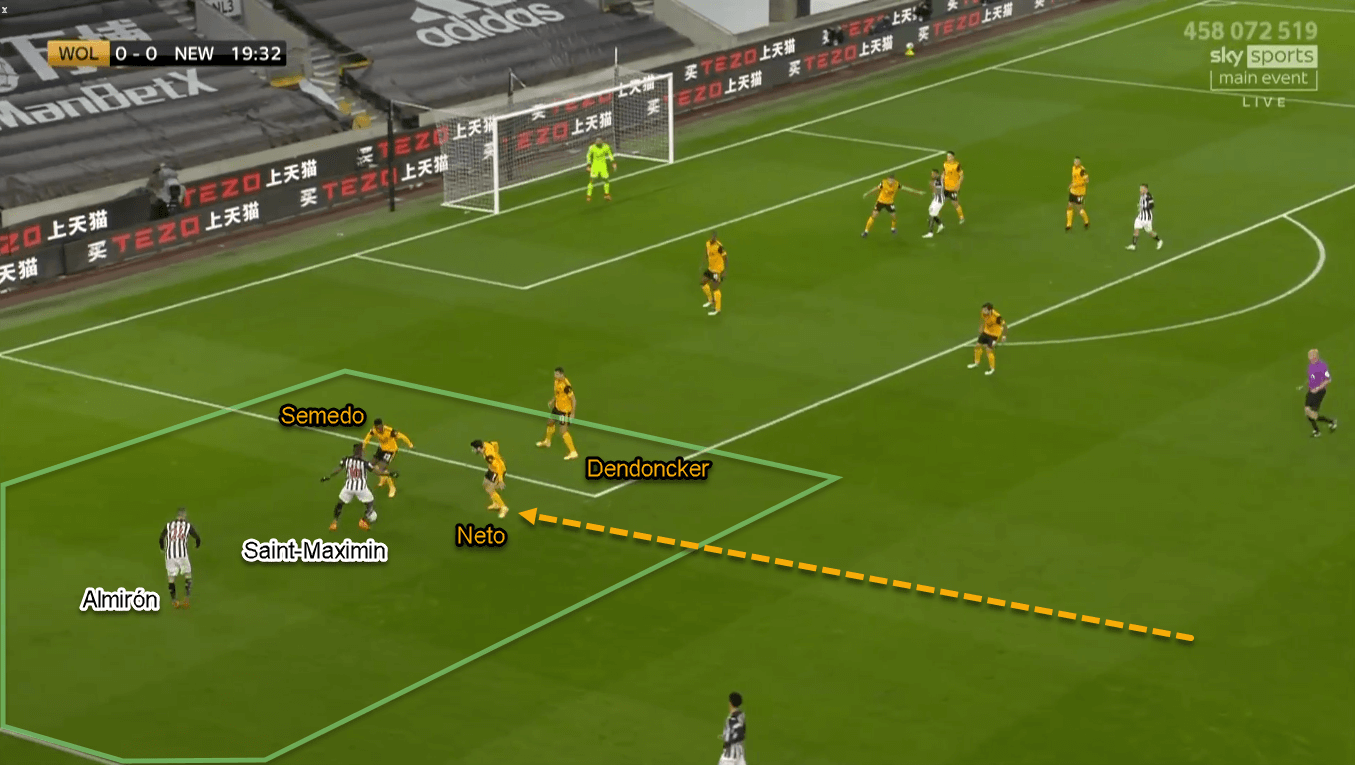

Wolves would drop to a mid-block 5–2–3 when they didn’t have the ball. The objectives were similar to their counterparts; to close central lanes and force Newcastle to attack through wide areas. If the Magpies tried to play from the flank, Wolves’ ball-side wing-back would step up and press the man in stripes. Then, the nearby central midfielder and/or centre-back would help him by closing the inside progressive passing option. This is quite similar to Newcastle’s defensive strategy.

If Newcastle tried to penetrate centrally, the nearest Wolves central midfielder would press his counterpart even before the Newcastle midfielder received the ball. In the process, either Rúben Neves or Dendoncker would leave his initial area up to the attacking line to quickly press Fraser or Almirón, while his partner stayed put. This is why both Fraser and Almirón made so many backwards passes: 19 to be exact.

Later on, Nuno asked his troops to shift a bit to a 5–4–1. This shape provided more protection on the flanks as the wingers now defend alongside the midfielders. The wingers’ defensive work rate — especially Neto — was crucial to help Wolves overload the flank and nullify Newcastle’s threat there. As per the stats, Neto competed in five defensive duels. That’s as many as Saïss, Neves, and Dendoncker’s tally.

Newcastle’s attacking plans

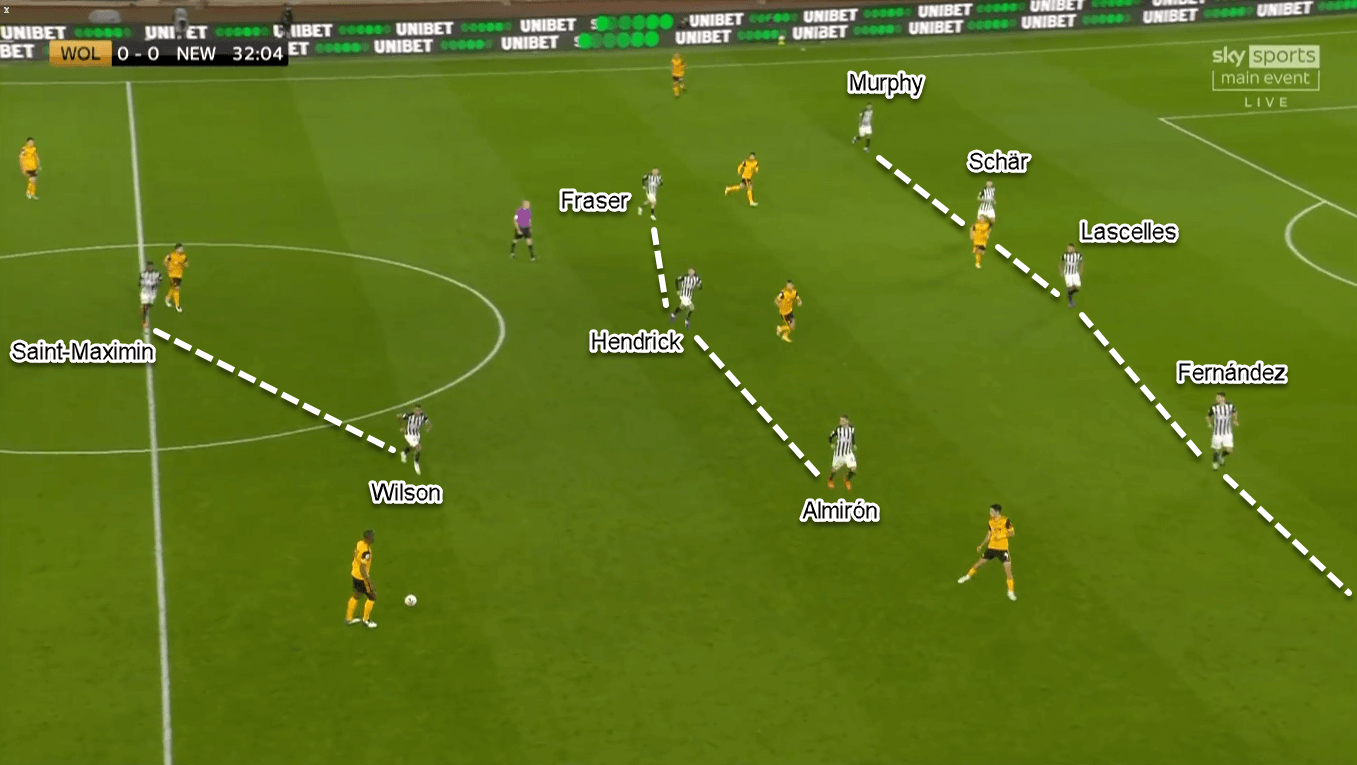

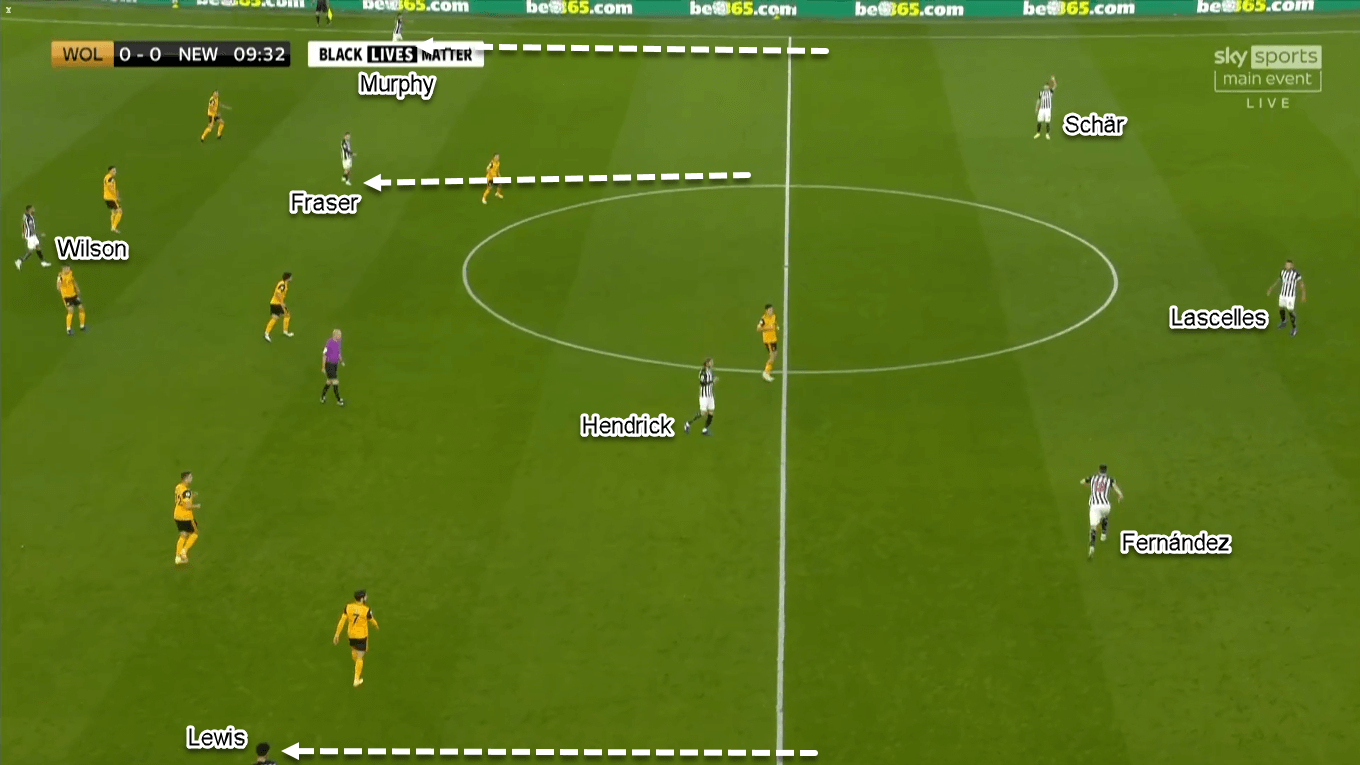

Newcastle did enjoy some minutes on the ball. When they did so, the Magpies would use 3–1–6/3–1–4–2-ish structure. In the process, both wing-backs would bomb forward and provide width in the flanks, while Fraser and Almirón step up to play closer to the forwards.

Wolves’ calculated defending in the middle prohibited Newcastle to penetrate centrally. To counter that, they would try to build their attacks near the touchline. Usually, Bruce would ask his ball-side central midfielder to drift wide and connect with the marauding wing-back easier. It’s not just that, though – both Fraser and Almirón were also given the task to overload the flank in the final third if necessary. It’s safe to say that Newcastle almost completely abandoned the central lanes when attacking.

Run, Wilson, run

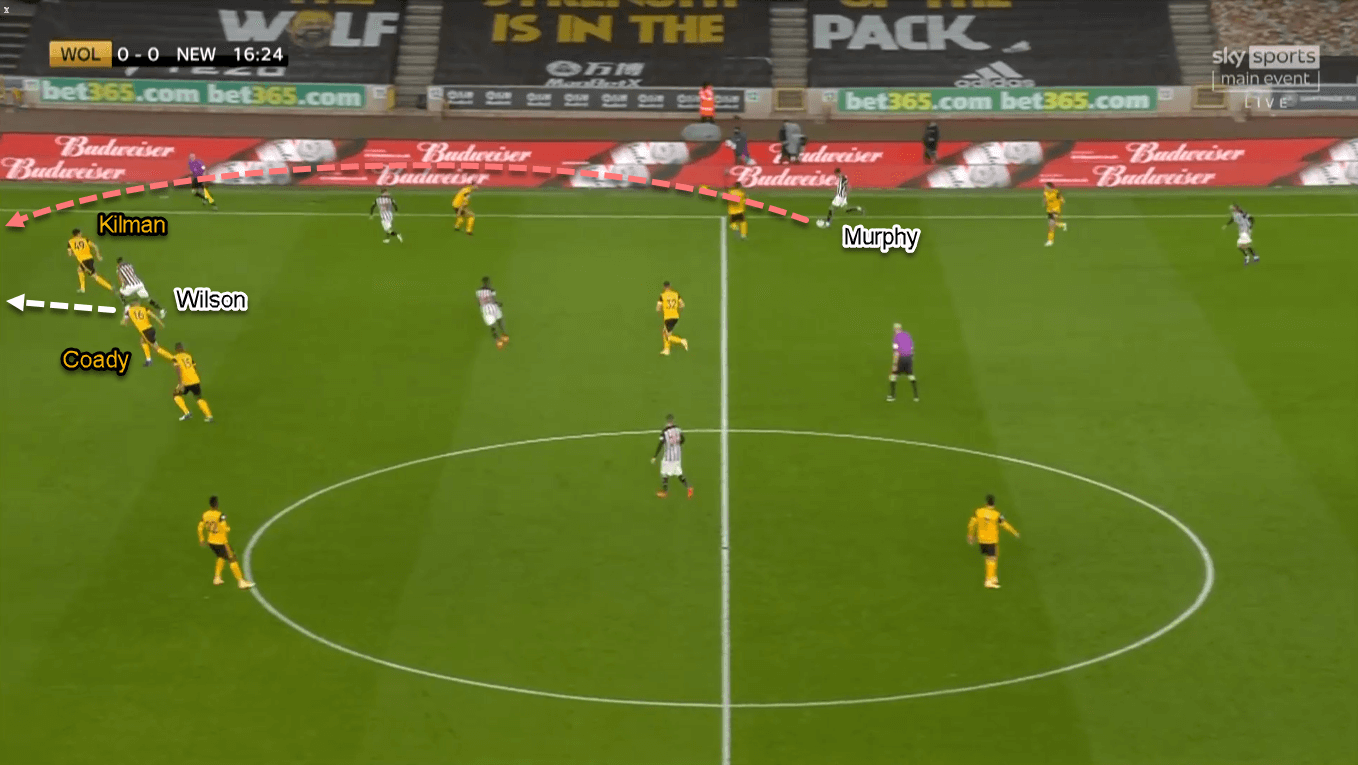

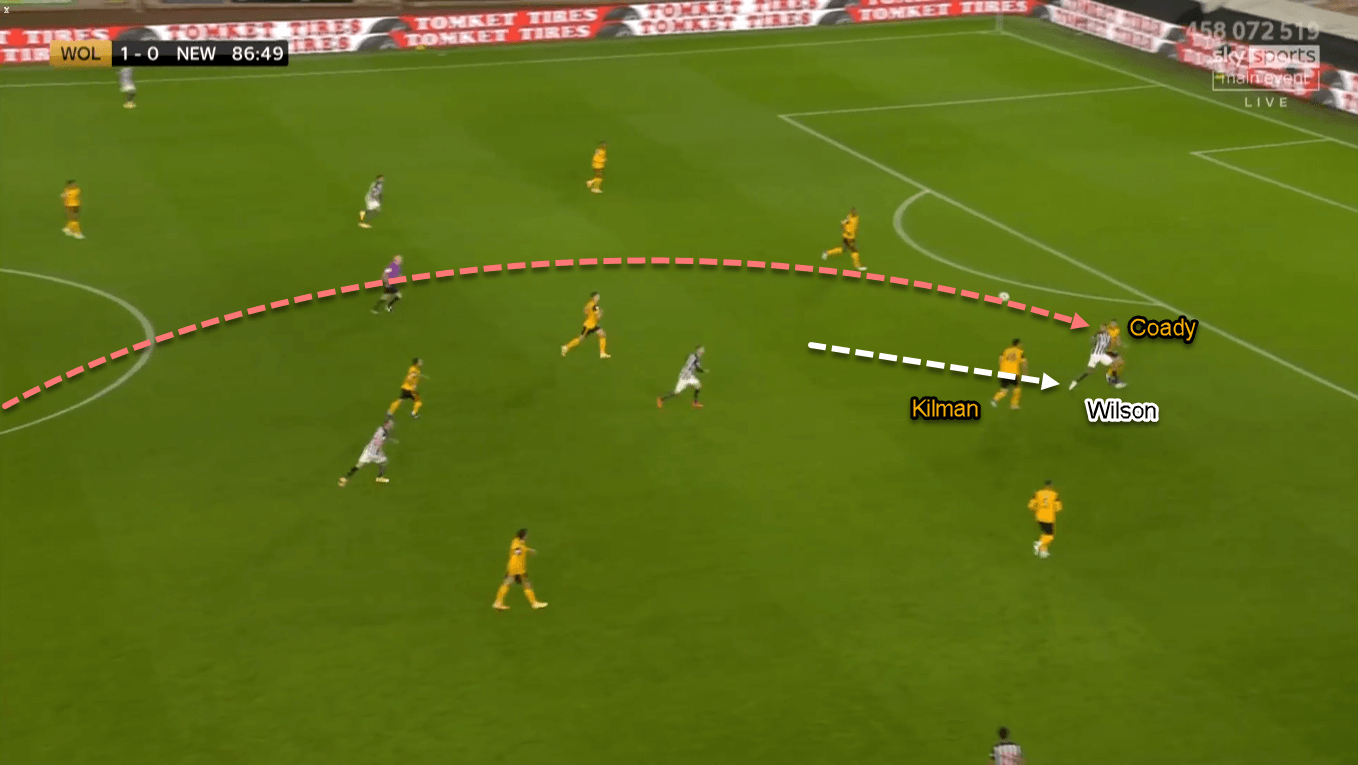

Despite the intricate movements, Newcastle’s biggest threats came from playing direct balls to Wilson. The main distributor in the first half was the right wing-back, Murphy. It’s no wonder why the majority (51.72%) of the visitors’ attacks came from his playing side. In the second half, Bruce gave the responsibility to Hendrick. This was partly because Wolves didn’t give much pressure on him when he got the ball.

Up front, Wilson wasn’t just running to chase the ball. First, he would start his run in between the centre-backs. This was important to confuse the defenders on who to close him down. Secondly, he would run diagonally and attack the blind-spot of the centre-back in front of him. Such a run would make him further from the far-side centre-back while also undetected for the defender in front of him, as Wilson made his run from the defender’s blind-spot. In fact, the equalising goal started from this approach.

Conclusion

For 80 minutes, this match only brought yawns after yawns for the viewers. If the blame must go to someone, it should go to Nuno and his men. Wolves were unable to break down the visitors despite the big defensive problem Newcastle had throughout the game.

For Bruce’s Newcastle, this result provides a good relief after a 0–4 battering from Manchester United last week. The experiment to play Fraser and Almirón in the midfield also proved fruitful, as the latter put a decent performance out of his natural position. Newcastle will face the league leaders Everton next week. Can they cause another upset?

Let’s just wait and see.

Comments