The top of the table clash in the Bundesliga this weekend saw RB Leipzig take on Bayer Leverkusen in Leipzig, with the clash seeing Julian Nagelsmann take on Peter Bosz once again. Clashes between the two managers are always tactically interesting, and I always make sure to cover them for the site, with Nagelsmann’s flexible pressing concepts usually making a good opponent for Bosz’s flexible build-up structures and patient possession game. This game was no exception really, and both teams pressed and built up well at times in the game to make it a very tight game, one which Peter Bosz described as a “top game, but not top football”, with the Dutchman blaming the pressing of both teams for the overall lack of chances in the game.

This tactical analysis will therefore focus on the pressing structures of both teams, as well as the solutions posed by both teams, before then examining Julian Nagelsmann’s decision to switch system and how this switch was a compromise which allowed Leipzig to win the game.

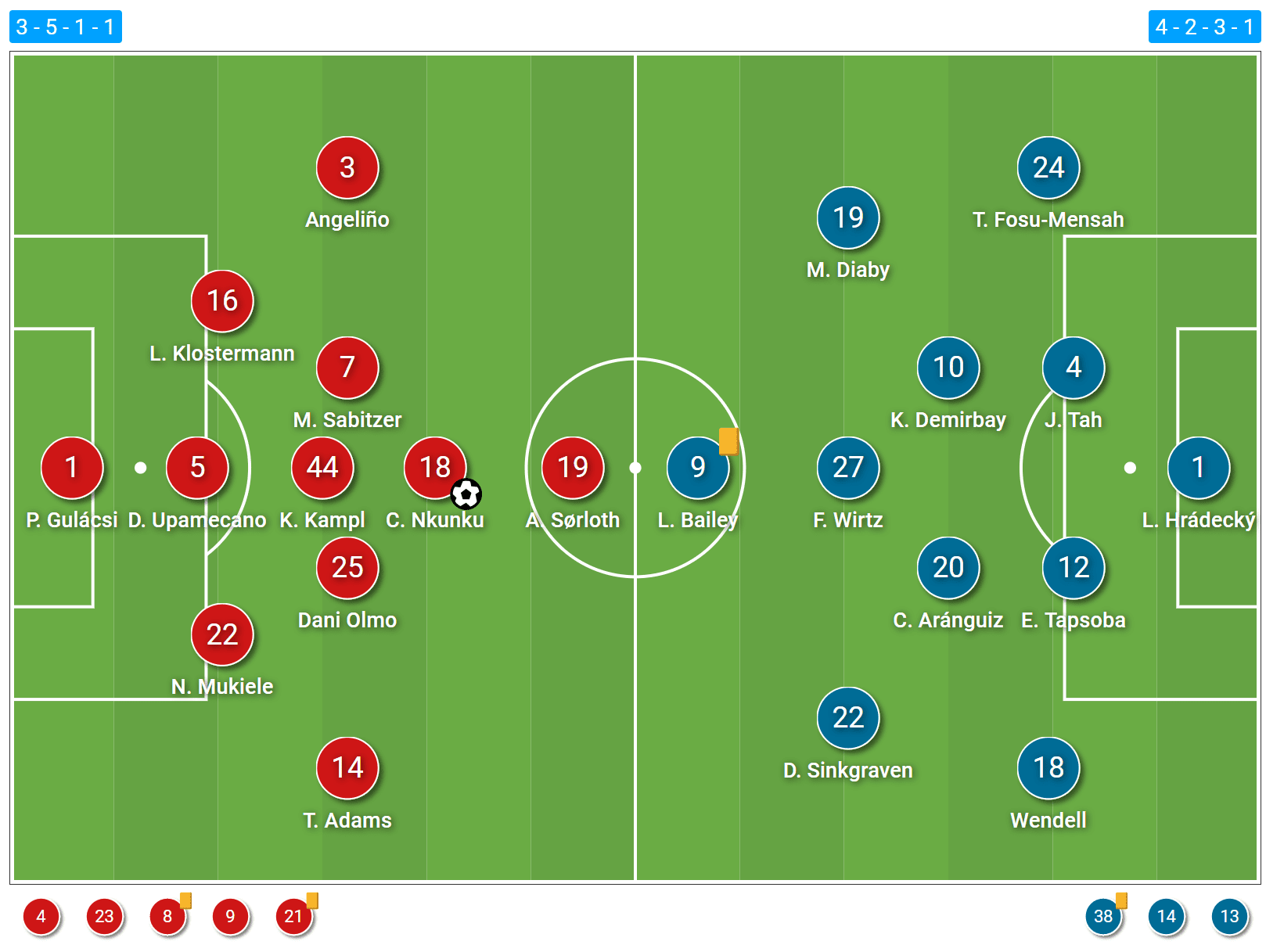

Lineups

The match started with the teams in both of these shapes below, but RB Leipzig’s shape was far more fluid, with player’s roles and positions changing when in or out of possession. The general formation for Leipzig was a 3-5-1-1, with an almost diamond midfield of Kevin Kampl (six), Tottenham linked Marcel Sabitzer, Dani Olmo (eights) and Christopher Nkunku (ten). This system rotated slightly out of possession, as I will cover in the analysis. Leverkusen went with a 4-2-3-1, with 17-year-old Florian Wirtz as a ten, with Kerem Demirbay and Charles Aránguiz forming a double pivot behind. Former Manchester United full-back Timothy Fos-Mensah started for Leverkusen also.

Leipzig’s 3-1-4-2 press

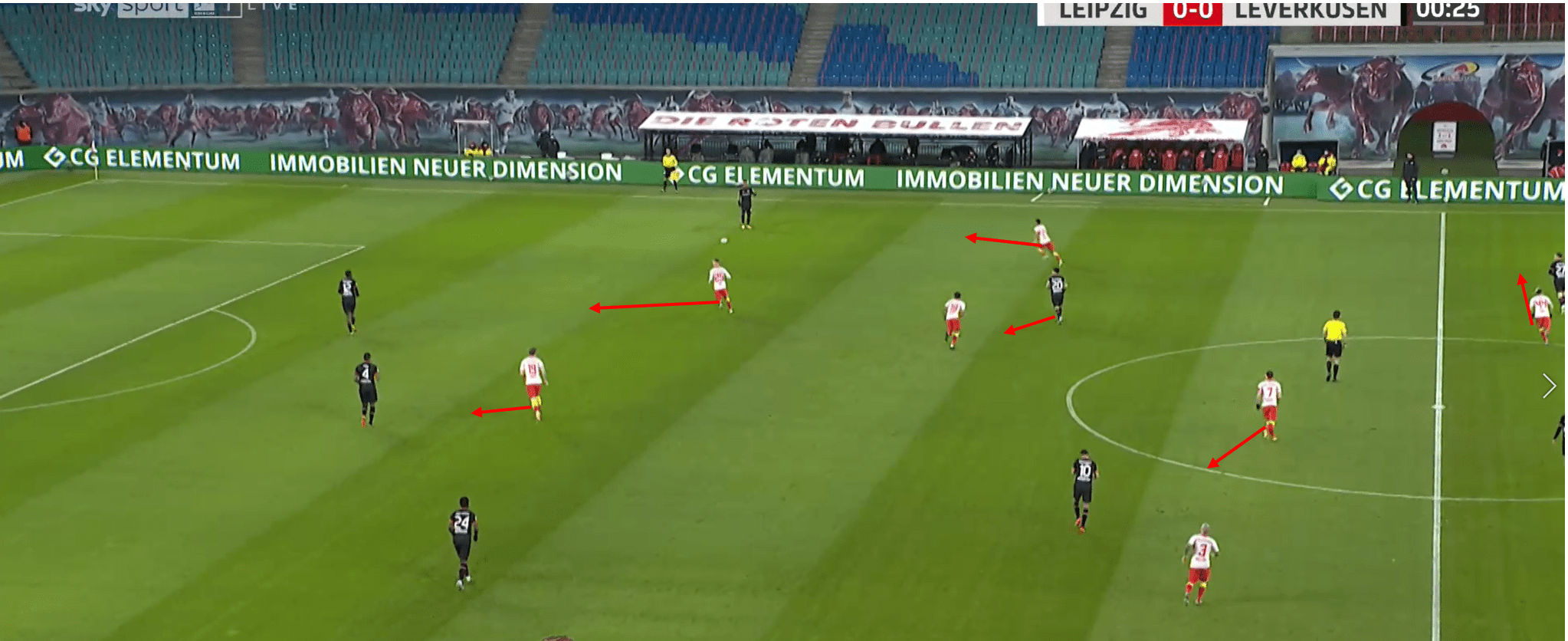

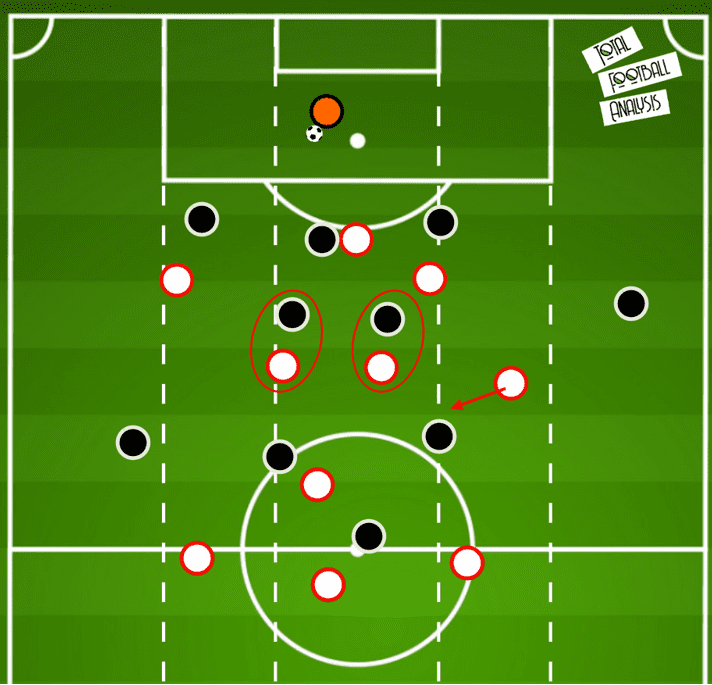

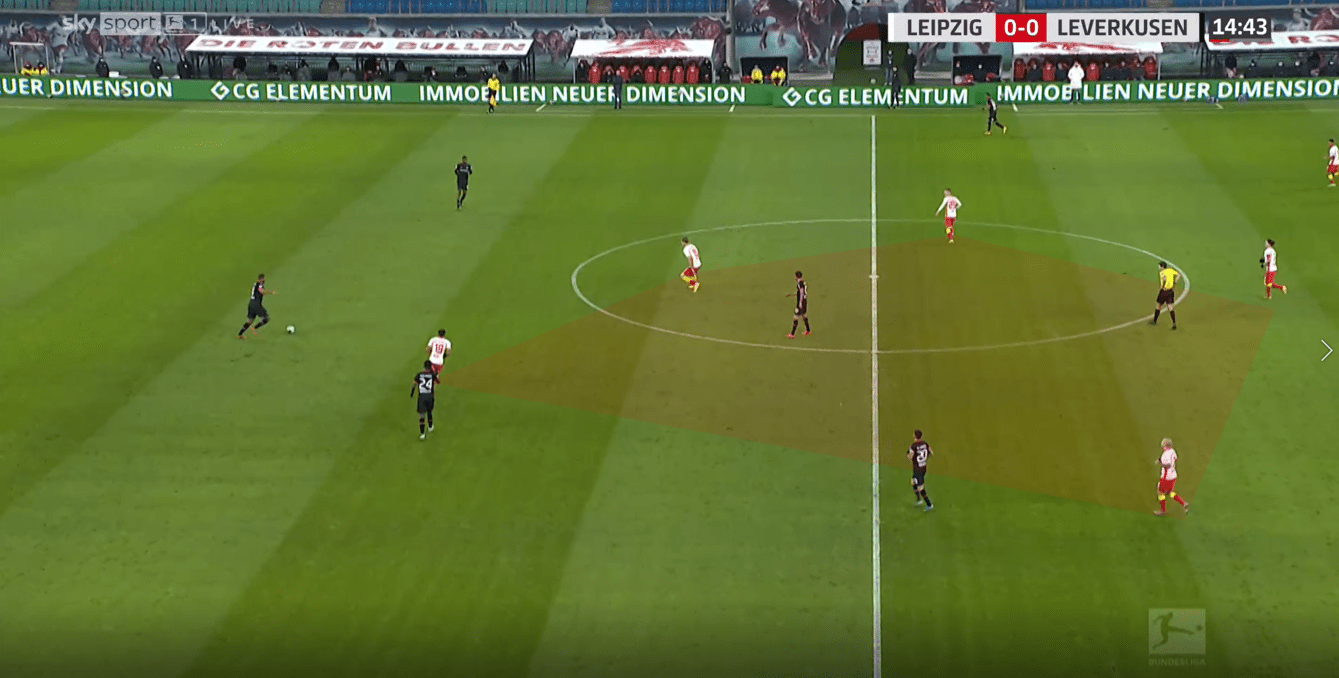

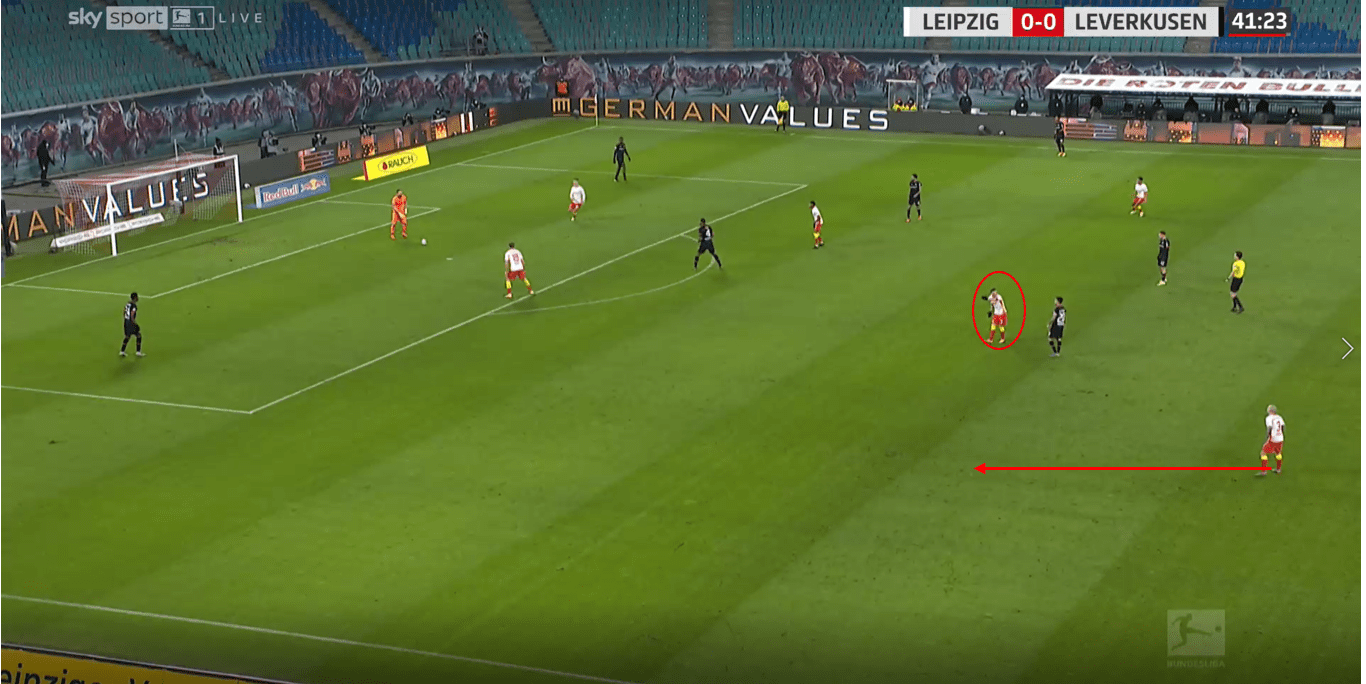

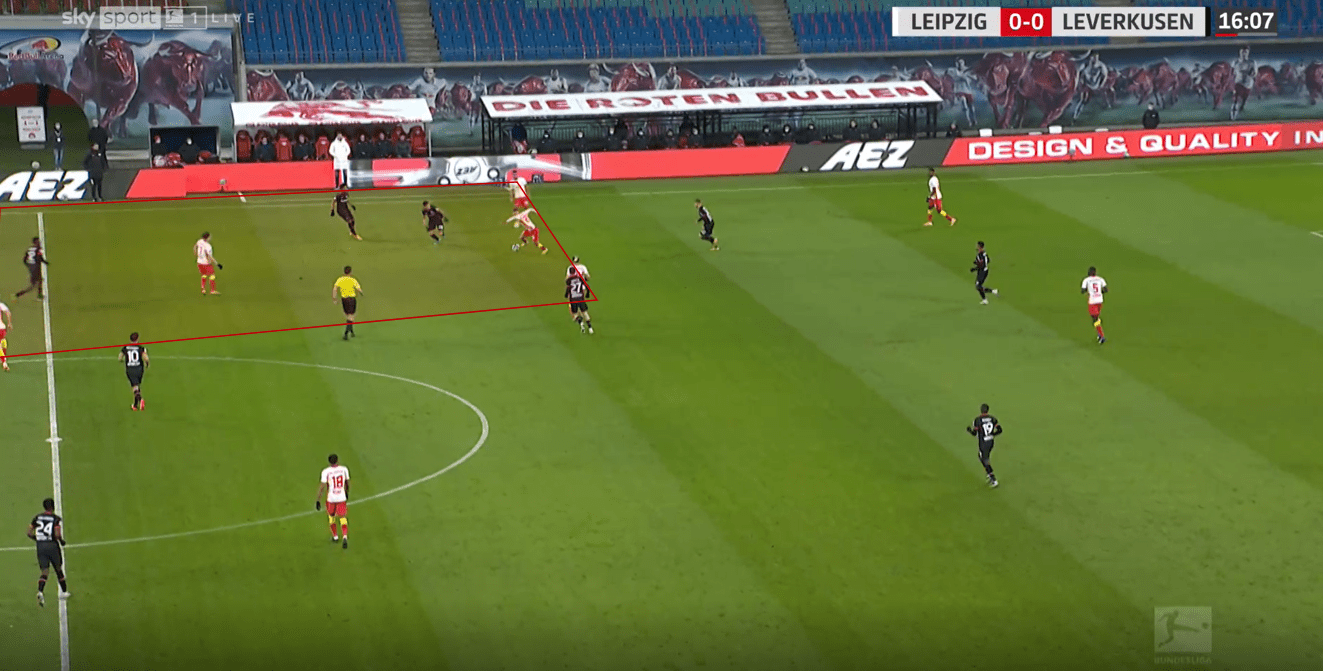

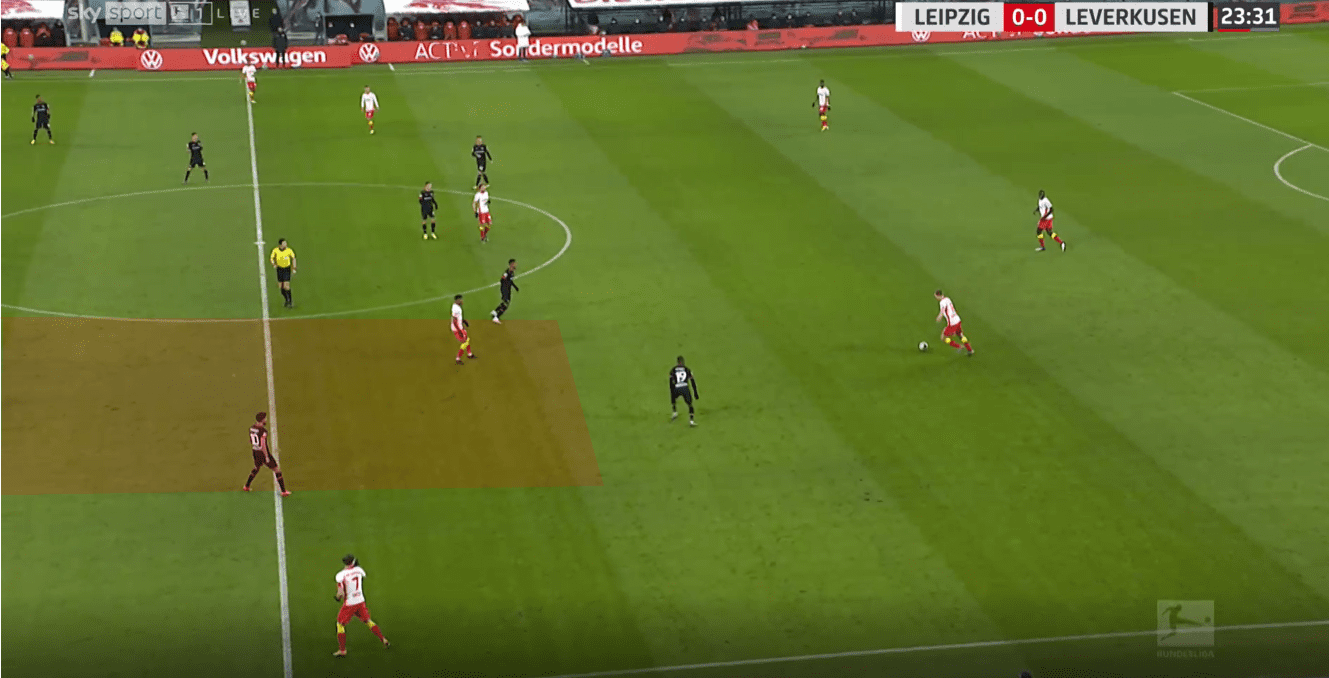

The early parts of the game saw Leipzig aggressive in their pressing, with the formation chosen by Nagelsmann allowing pressure to be maintained on the ball at all times high up the pitch. We can see this pressing scheme below and the roles occupied by each player. Dani Olmo pushed higher from central midfield to join the first line and press Leverkusen’s centre backs, pressing as a front two along with Alexander Sørloth. Leipzig’s wing-backs pressed very high against the Leverkusen wing-backs where possible. Even with Olmo pushing higher out of the midfield, Leipzig still had three central midfielders available to press Leverkusen, and they were helpfully staggered oppositely to Leverkusen’s 4-2-3-1, and so Kevin Kampl could mark the ten while the two eights could press the pivots.

Naturally then, with central midfielders pressed high and covered tightly, and centre backs pressured, the ball could be forced wide, which seems to be a general Nagelsmann principle this season. Pressure could then be applied on the full-back, and so there was little option other than to play long or into central areas. Due to the midfield three of Leipzig, playing into central areas became very difficult for Leverkusen, and so ball progression was a problem for Leverkusen.

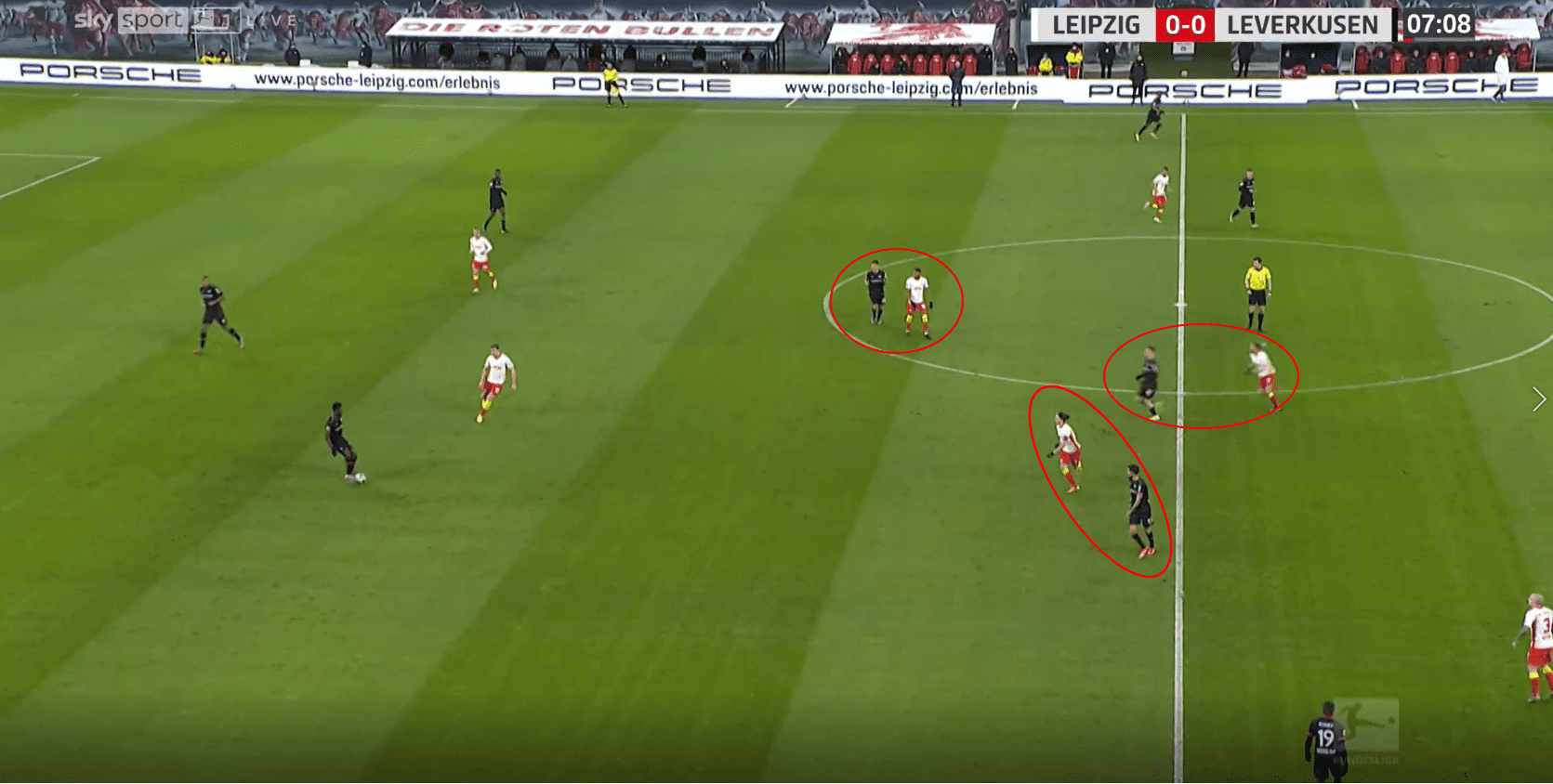

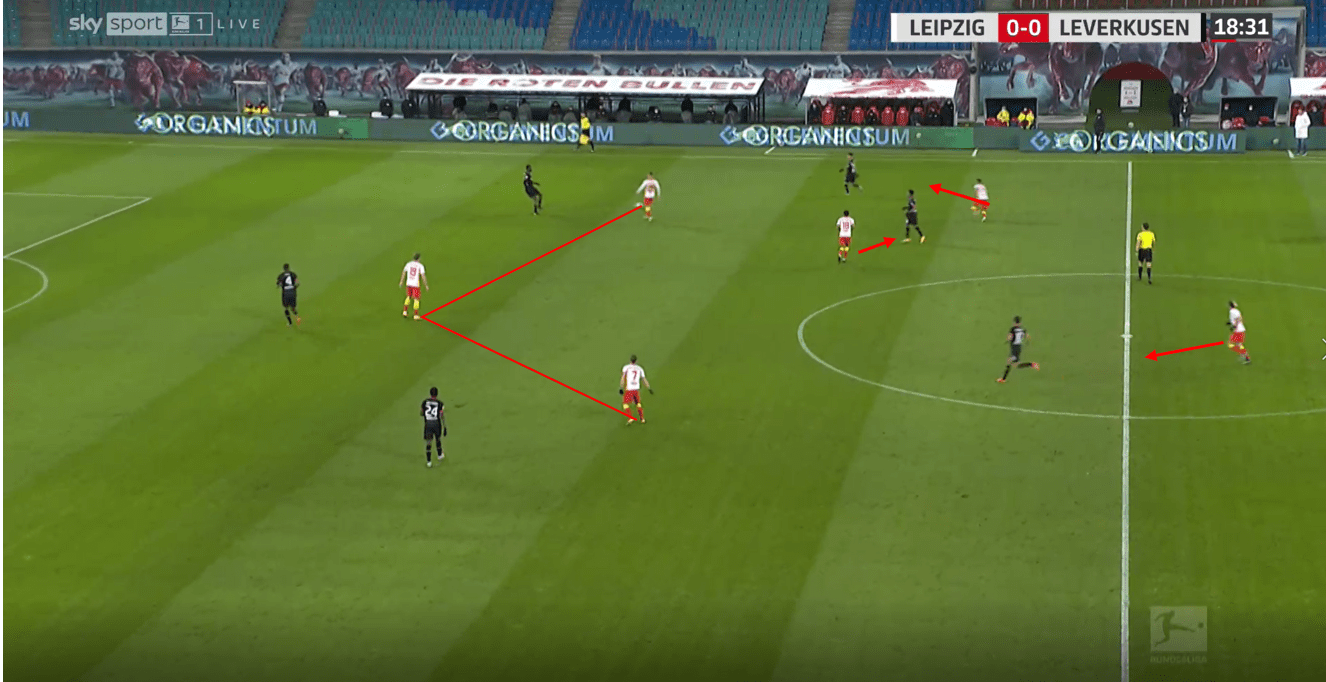

The use of the back three by Nagelsmann allowed an extra player for aggressive pressing high up the pitch, and the system seemed to be specifically chosen to prevent Bayer Leverkusen creating central overloads, with a three-man midfield difficult (but not impossible) to overload. We can see the midfield of Leipzig here covering Leverkusen’s central options well, with Sabitzer and Nkunku on the deeper midfielders while Kampl follows Wirtz higher. Leverkusen have formed a back three here, but Leipzig’s front two are able to apply pressure.

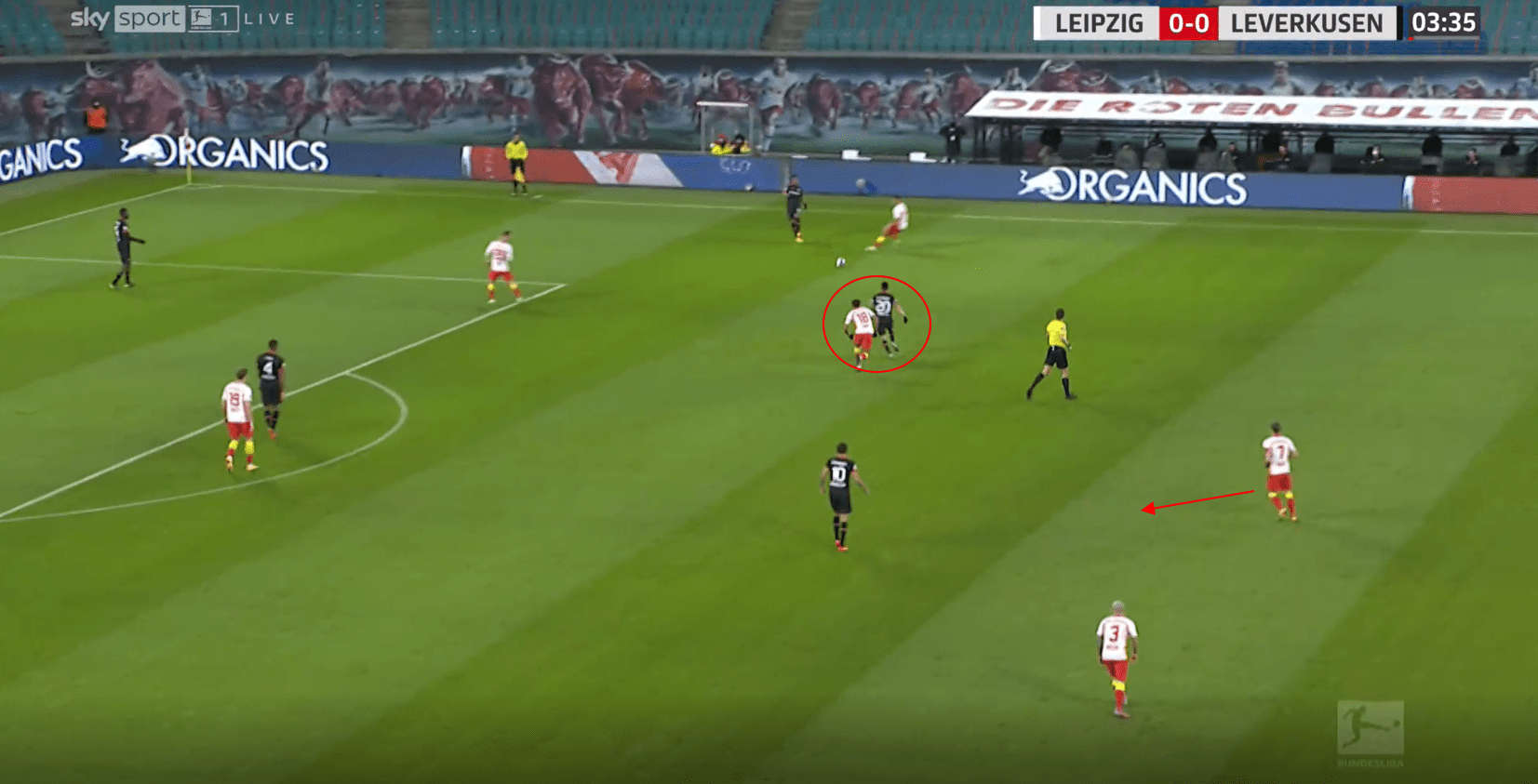

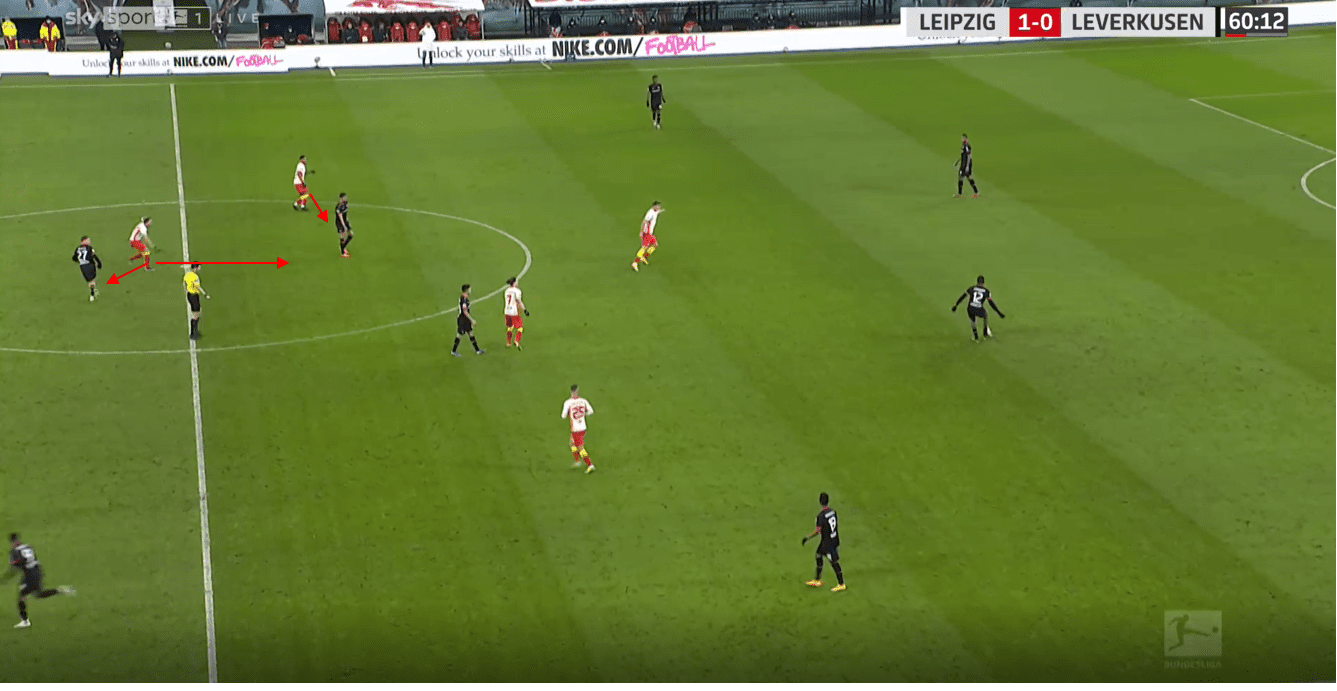

Kampl’s role initially seemed quite man-oriented around Florian Wirtz, and so if Wirtz dropped wide as he does here, Kampl would remain tight and follow the youngster wide. This of course leaves a space in the middle of the pitch, but with three players already committed to central areas, creating an overload in this area was difficult.

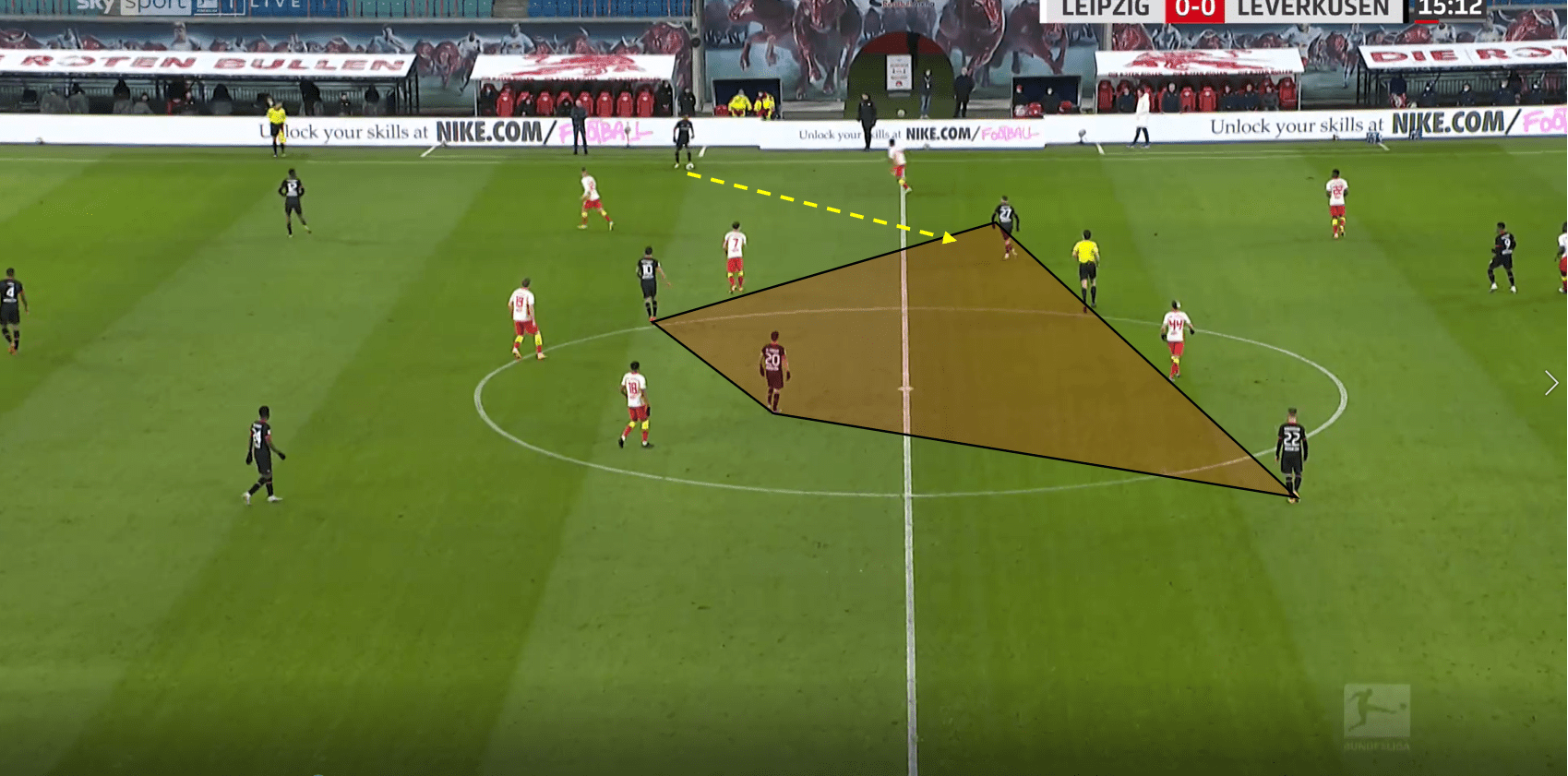

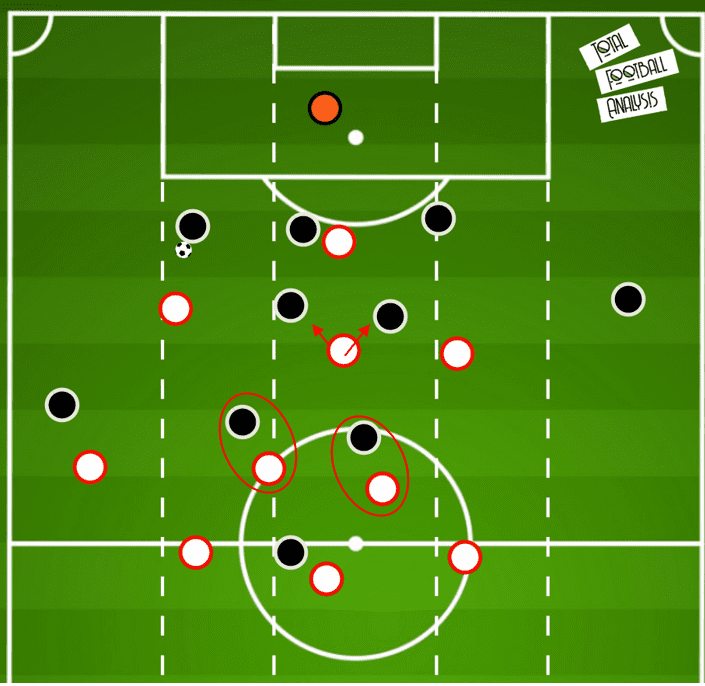

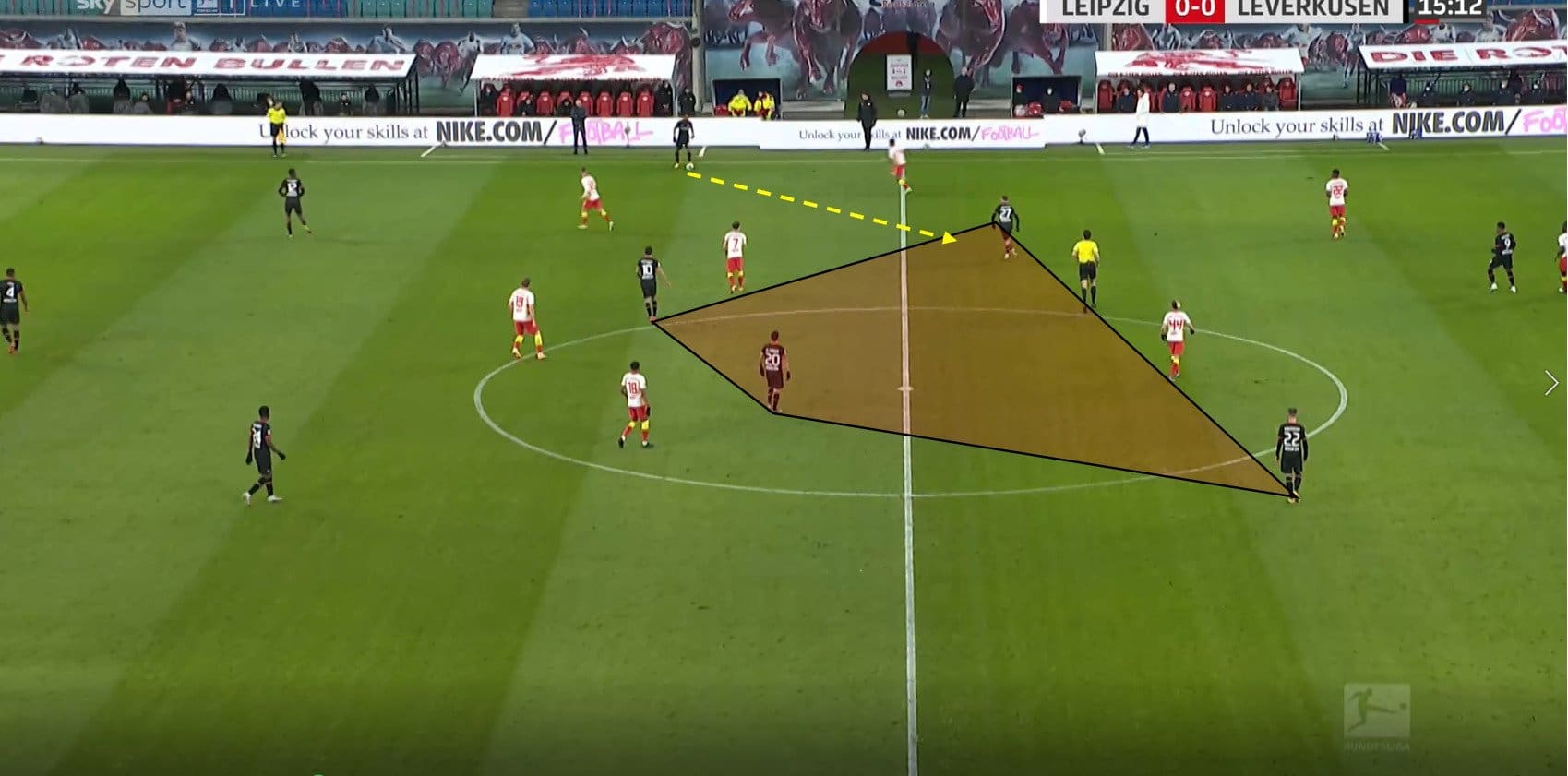

Leverkusen were able to test and exploit Kampl’s pressing at times though, and Daley Sinkgraven played a key role in the game as he looked to overload the ten space at times to overload Kampl. We can see here Sinkgraven (#22) who started as a left-winger is now on the right side and occupies Kampl in the centre. Florian Wirtz drops into the left half-space, and Kampl doesn’t follow, meaning Leverkusen can progress. This suggests it wasn’t a strict man-marking approach by Kampl, as otherwise you would suspect he would follow Wirtz (his player) and leave Sinkgraven. Kampl’s role then seemed to be more focused on the player within the ten space for Leverkusen, but this area was Leipzig’s biggest weakness early on.

Tyler Adams did a decent job of nullifying this overload movement by Sinkgraven as we can see here in this diagram. Florian Writz shifts across to the left side of the pitch (our left) and takes Kevin Kampl with him. Leverkusen create a more asymmetric structure with Fosu-Mensah tucking in, and so the far wing-back (Wendell) can push high and wide. Sinkgraven moves inside to overload the ten space, and Adams follows when the ball is played long by the goalkeeper, and so Adams can intercept the ball. We can see though that the potential for a wide overload is created by Adams coming so narrow, and so Leipzig had to manage this threat.

Leverkusen’s build-up and solutions

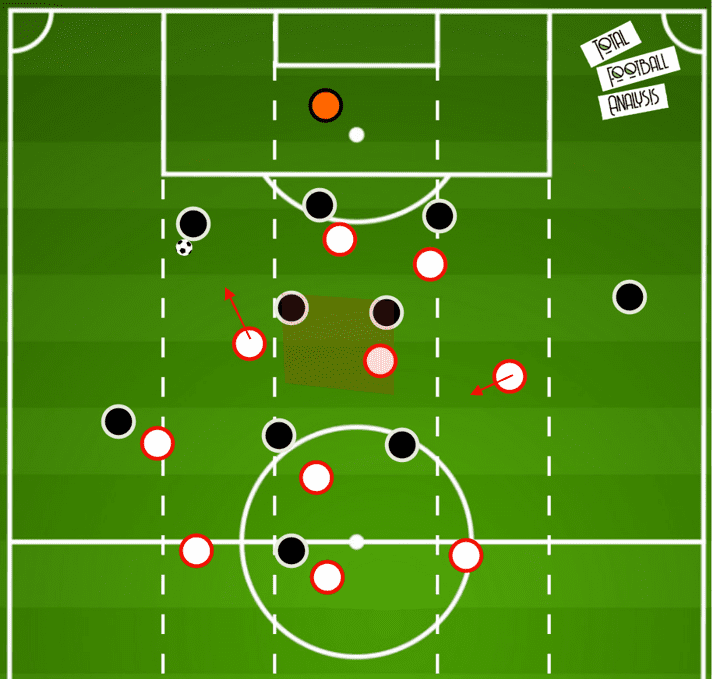

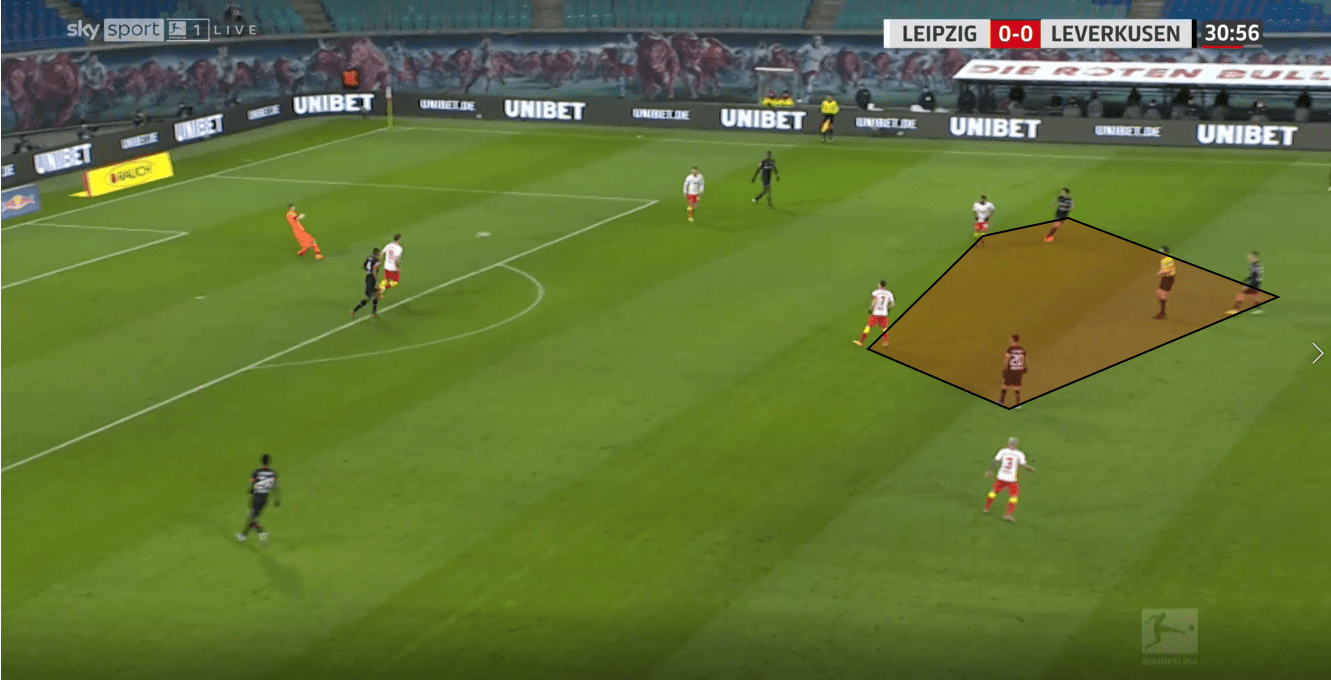

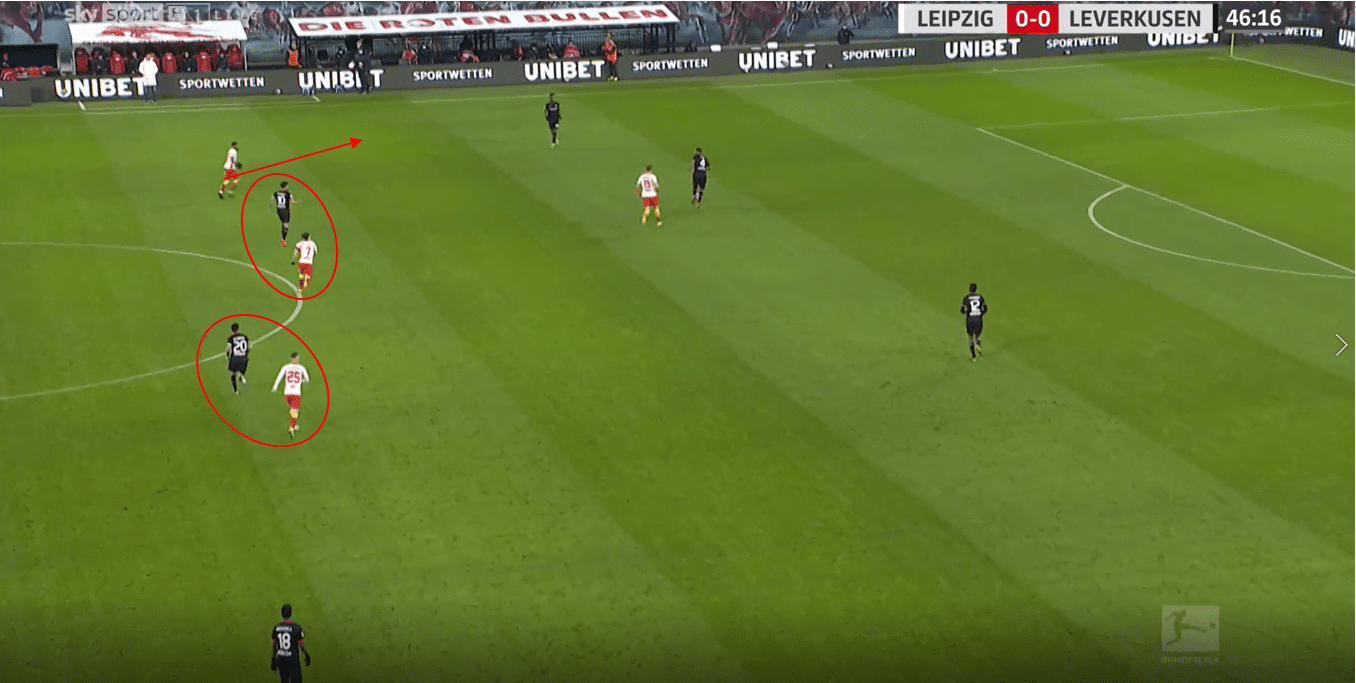

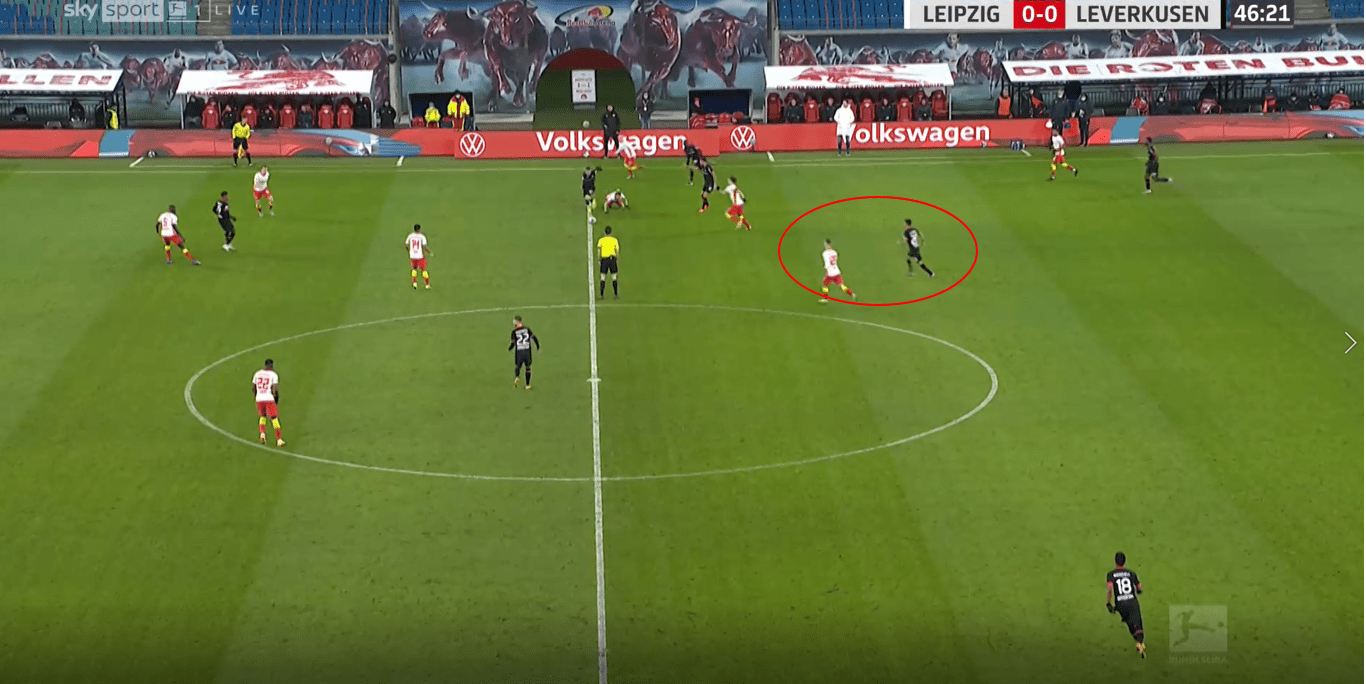

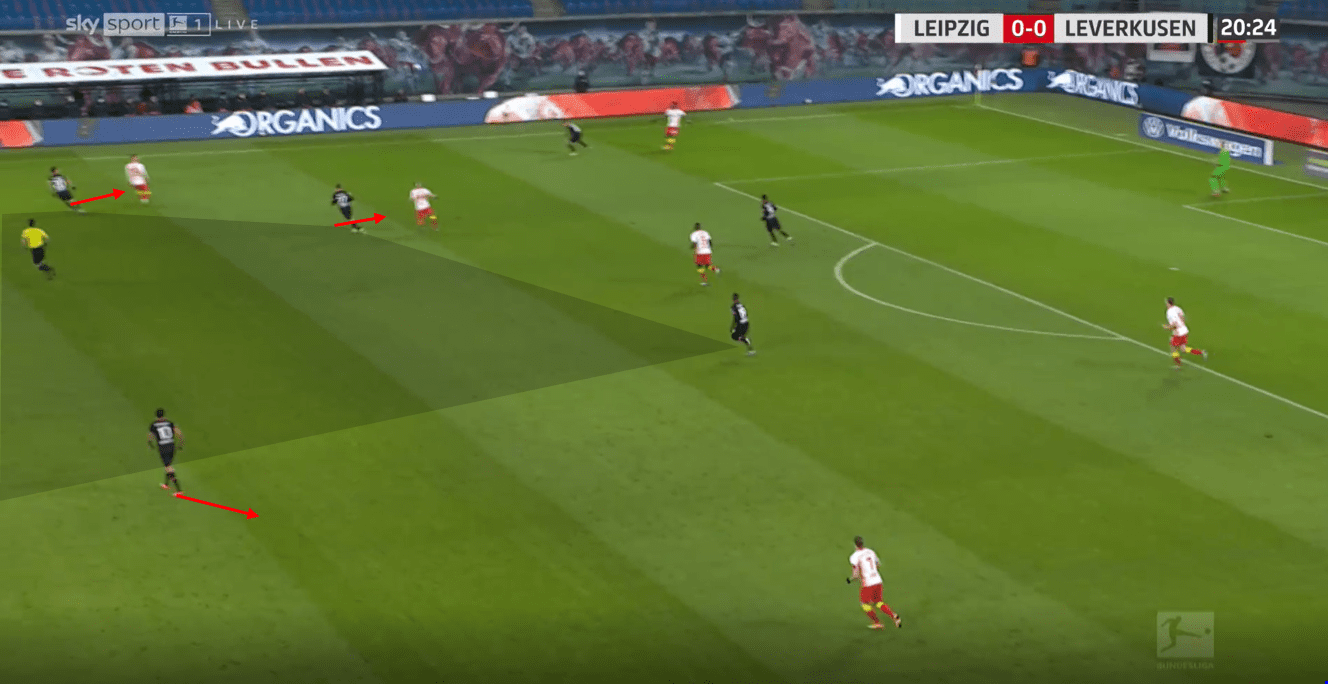

Leverkusen’s build-up varied between a back three and four,with the back three seeing Fosu-Mensah drop narrower and form that asymmetrical shape explained above. The aim of these varied numbers in the back line was to reduce pressure on the back line and look to disrupt Leipzig’s pressing scheme. We can see the potential implications of this asymmetrical back three here, with the ball switched into this narrow full-back here. Leverkusen looked to pin back the wing-back deeper, and so pressing the full-back then became the responsibility of the nearby midfielder. This opened the opportunity for an overload in midfield now, and if Sinkgraven inverted, suddenly it was a 4v2 in this area.

We can see here the use of the goalkeeper as well as Tah slightly higher creates this exact problem, with Angeliño not wanting to press high despite being told to by Sabitzer. We will come back to this image, as it takes place at an interesting part of the game tactically.

The same concept applies here, with Fosu Mensah’s narrow positioning tirggering a press from Nkunku. The single pivot of Demirbay now is free between the lines, and Sabitzer is sat deeper, and so Leipzig rely on the striker to cut the passing lane, something which isn’t one of Sørloth’s biggest strengths yet.

Leverkusen move into a more symetrical shape here, albeit with a rotation between a pivot and full-back. The ball is switched across from right to left, and Marcel Sabitzer steps higher to press, leaving a central midfielder free behind him. The pivot receives the ball in a wide area and is pressed by the wing-back on the opposite side, and the ball near central midfielder Nkunku covers the near pivot, however the far pivot must now be covered by Kampl, meaning the ten space is unoccupied. These moments of imbalance weren’t capitalised on too well by Leverkusen, but they were still a threat.

Leverkusen did persist with those overlaods in central positions however, and we can see a good example here where Wirtz drops while Sinkgraven pins Kampl.

Leverkusen would sometimes form more of a midfield box, and so Sinkgraven and Wirtz would position themselves either side of the narrow Leverkusen pivots. Here Leverkusen play more directly but look to still overload the ten space, with Wirtz and Sinkgraven on the same line receiving a long throw from the goalkeeper. Tyler Adams again does a good job of nullifying this threat, but this isn’t the ideal solution to the problem, as you are asking Adams to balance the overload constantly which is difficult.

How did Nagelsmann adjust?

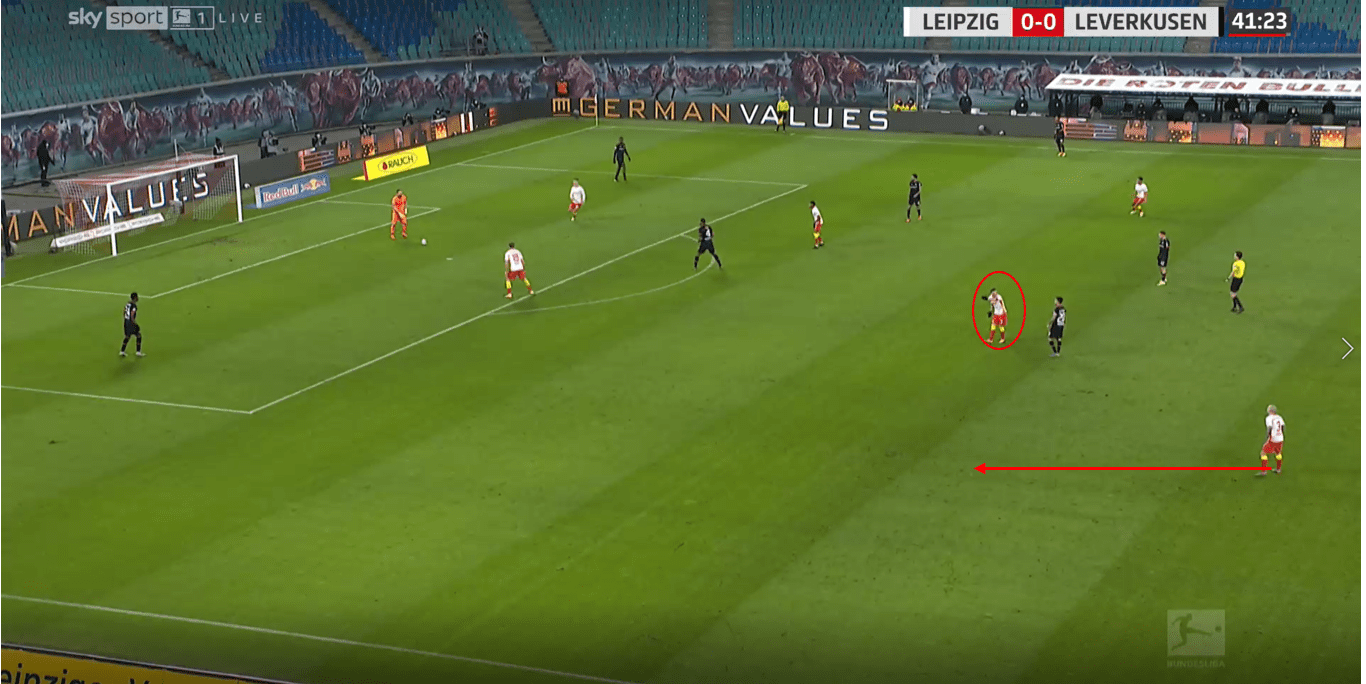

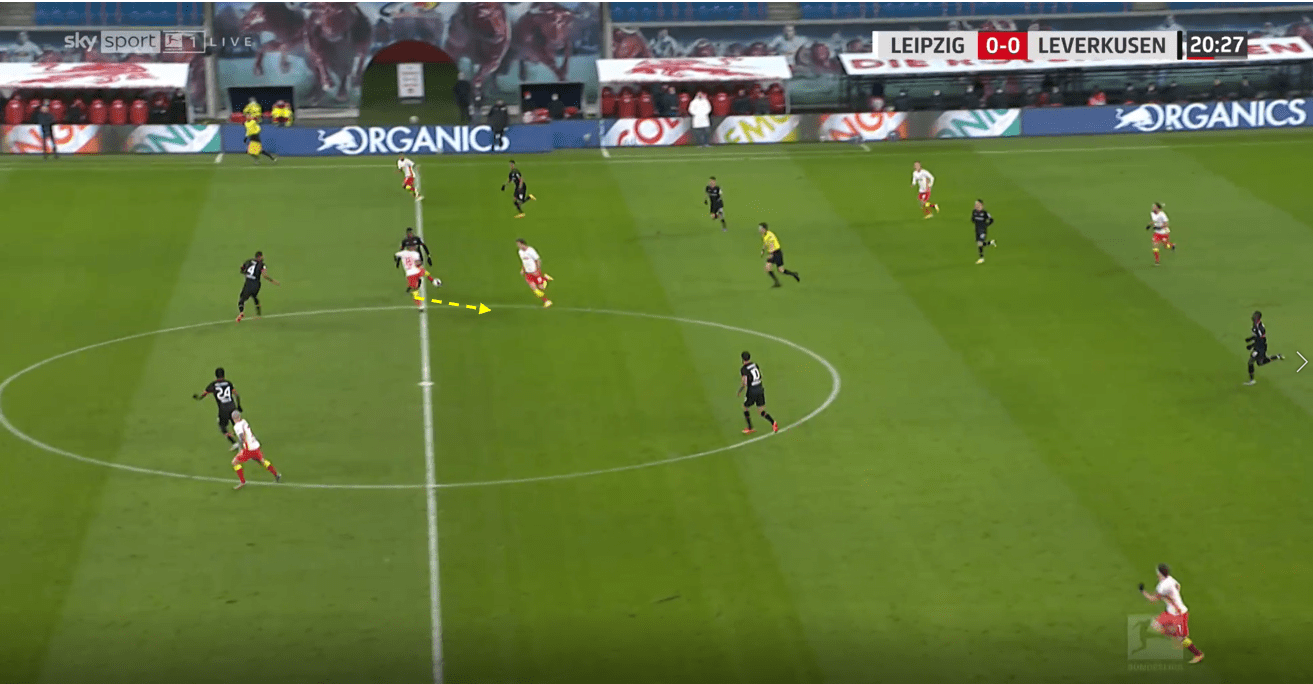

Midway through the first half the TV cameras picked up Nagelsmann handing Angeliño a note, something which was later discovered to be a note showing an instruction for the team to switch into a 4-2-3-1. Leipzig weren’t able to make this switch convincingly in the first half, and ended up in a kind of limbo between the two formations, but Nagelsmann got the message across fully in the second half.

If we go back to this scene here, we see the limbo the teams is in regarding formations. Nkunku was supposed to move to left wing and so would be responsible for pressing the full-back. As a result, Angeliño drops off to form a back four, as he’s the one who’s seen the note and has the best idea of what is supposed to be happening probably. Nkunku though resumes his earlier role of pressing a pivot, and so he acts as a central midfielder. Therefore, the full-back becomes open, prompting Sabitzer to tell Angeliño to push on. We can see Tyler Adams is still wide as a wing-back, as opposed to being in a double pivot as he was in the second half. Leipzig’s pressing got them through to half time safely, but they will want to get the message across better next time, as they had about 20 minutes of the first half left when the note was passed.

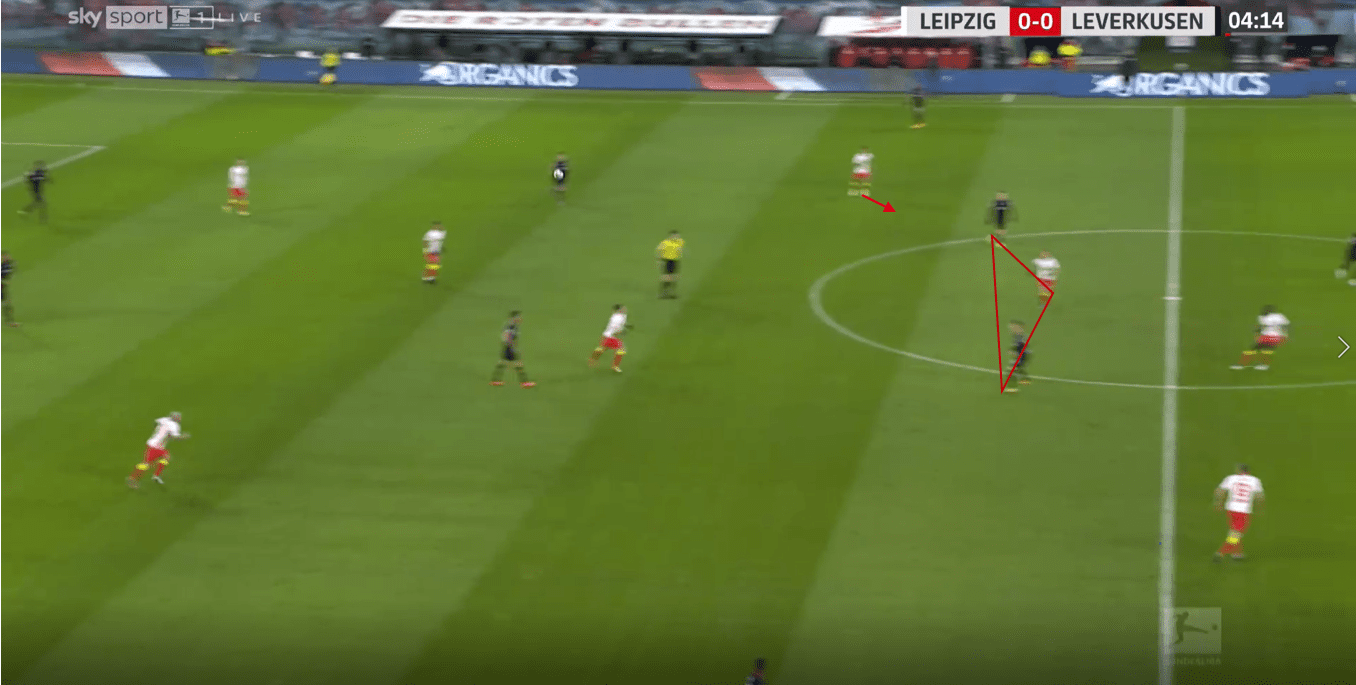

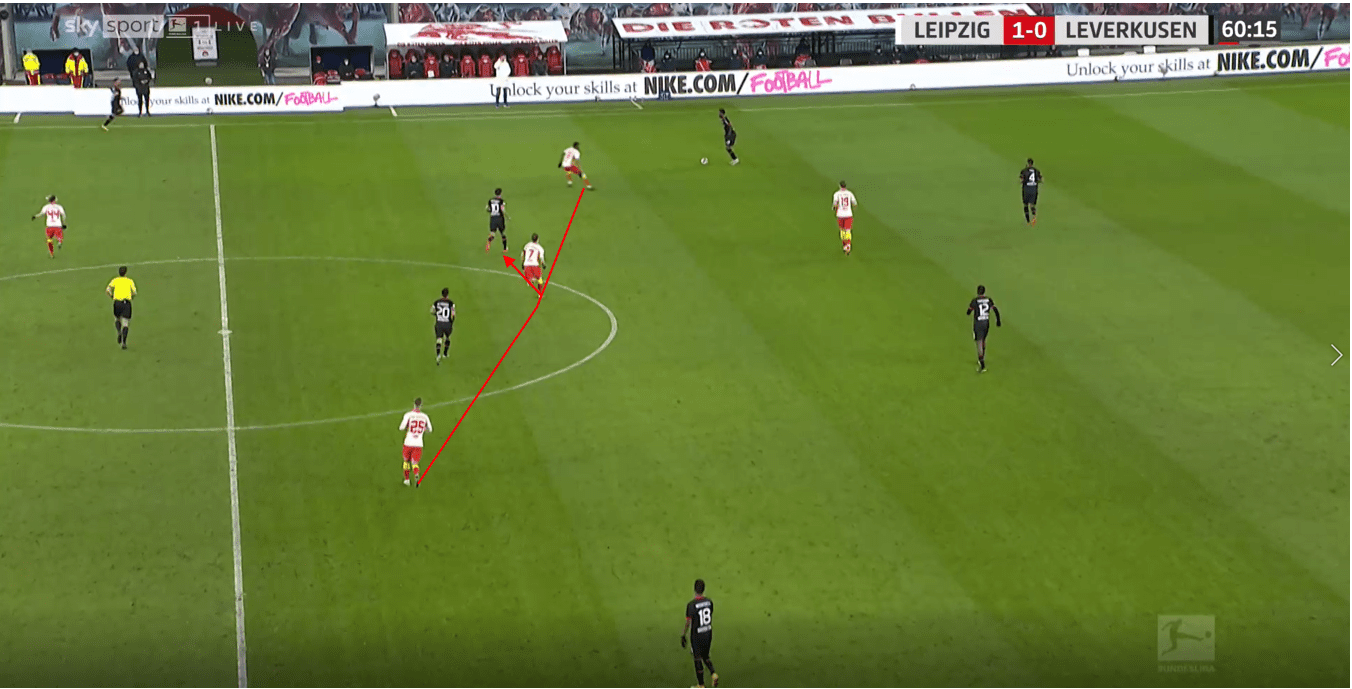

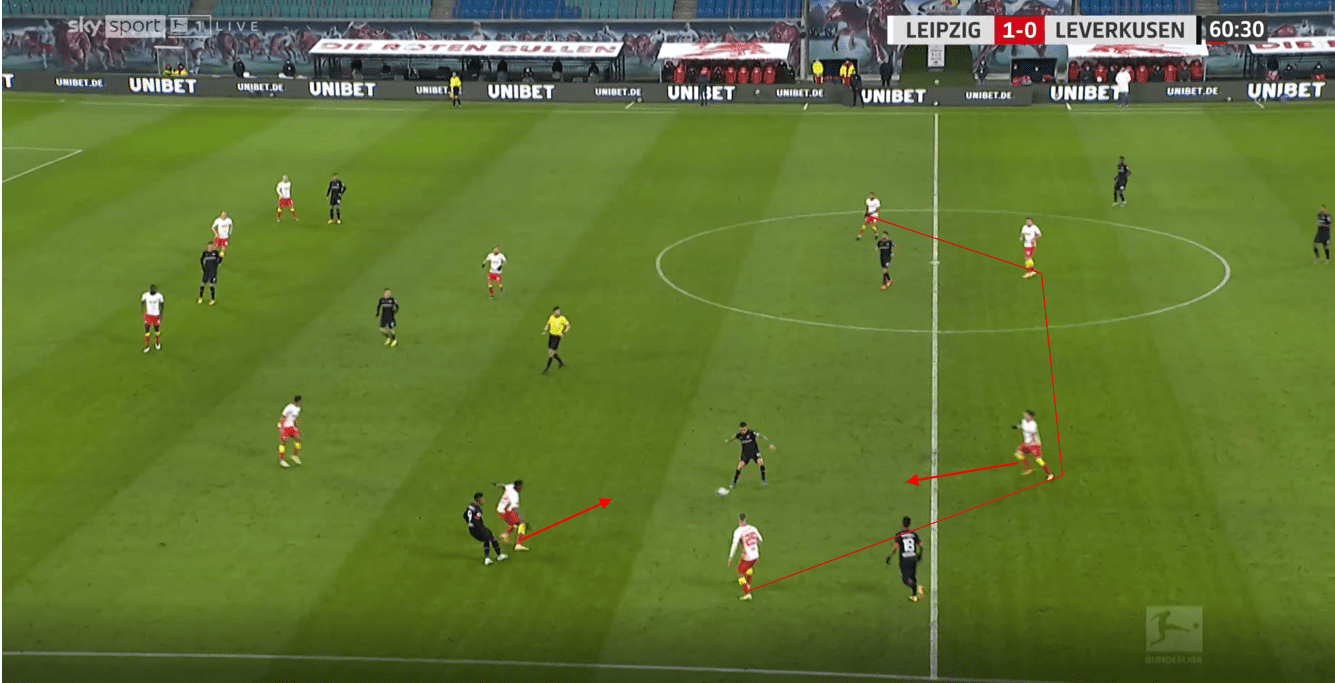

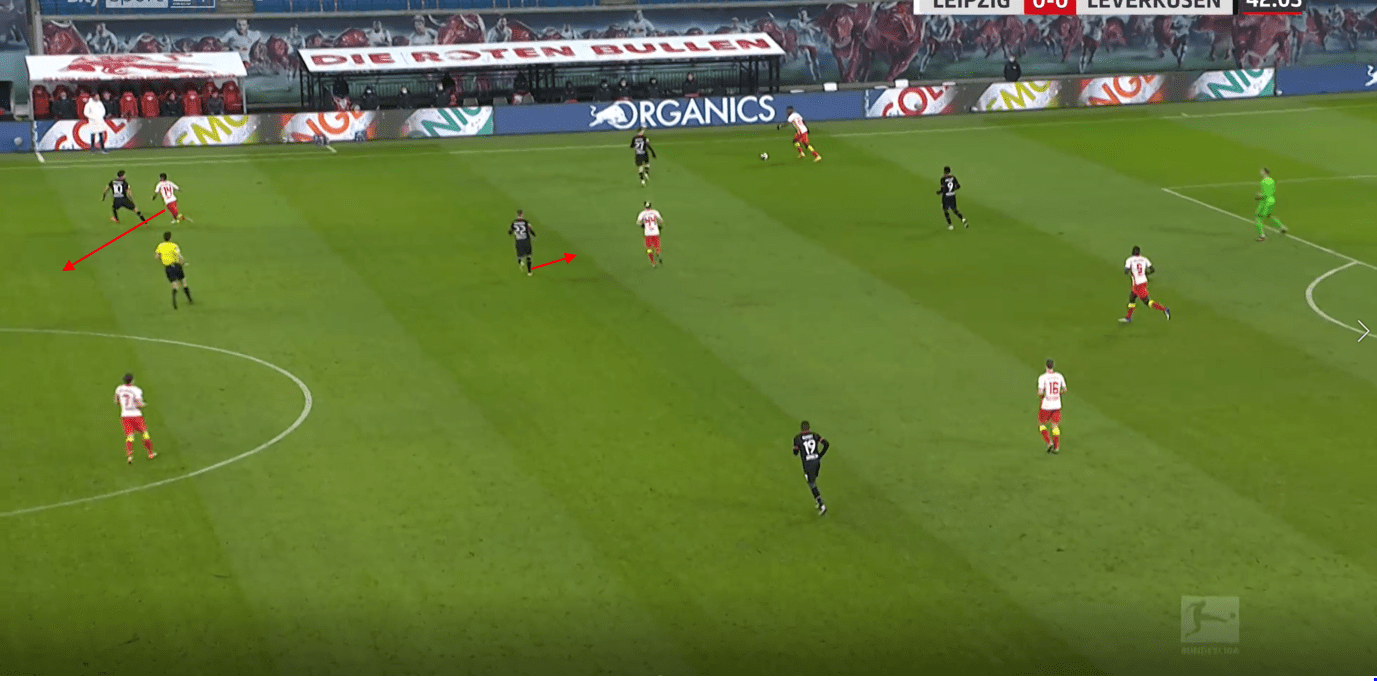

In the second half, the switch could be clearly seen, with Sabitzer moving higher as a pressing ten, with Olmo and Nkunku either side of him. The switch was made with the idea of both nullifying the central overloads and making a compromise. Here, we can see the ‘ideal’ situation for Leipzig, with the near pivot marked by Sabitzer and the far pivot able to be covered by the far winger, who tucks in narrower to ensure this. This is Leipzig’s most common shape that they have used this season.

Dropping into the 4-2-3-1 gave the advantage of now having a double pivot in the ten space, and so that overload that was being created around Kevin Kampl no longer existed. The overload was instead shifted by Naglesmann to be deeper for Leverkusen/ further from the Leipzig goal. As a result, the impact of this overload was lessened, and so Leverkusen’s ball progression suffered. Leipzig also sat into more of a mid block, which of course made them commit more numbers in deeper areas.

We can see the pressing scheme in action below, with the overload now created around Sabitzer. With the ball switching from side to side, Sabizter had to work hard to balance between either pivot, as did the far winger who would come across to mark the far pivot if needed. The mid block now means that the full-back doesn’t have to press as high, and so centre backs become less exposed.

With good,quick circulation of the ball, Leverkusen could access the overload, but as I’ve said, the danger posed by this overload of the pivot space is less compared to the ten space. Here we see Sabitzer covers the central pivot while another makes an early movement wide, and so cannot be covered. Leipzig are able to maintain a fairly stable structure thanks to the bodies back, and so Leverkusen struggle to create any chances.

Another advantage to this 4-2-3-1 shape was that even if the overload was created, it happened in front of the central midfielders, as opposed to behind them in the ten space. Because it is now visible and easier to spot, it becomes easier to balance between the two and jump forward if needed.

Leverkusen come up with a good solution here early on, where they commit both pivots far across to the right side, meaning that the far winger Olmo now tucks across far to cover the pivot. Leverkusen then switch the ball into an empty space, with the far winger nowhere near the full-back. Leverkusen didn’t do this anywhere near enough though, and had little solutions to the Leipzig shape, such as accessing the pivots with very central positioning for example, something which they are usually pretty good at. In the whole game, they only registered 0.5 xG, and the main bulk of this was a chance created in the second half created from direct play late on, rather than breaking down the Leipzig shape.

Leipzig on the other hand were able to create just over 2.0 xG, and much of this relied on their counter-attacking. We can see an example of a pressing trap which allows them to break with the ball and create a chance below. We can see Leverkusen play the ball wide and are then able to find the pivot. Sabitzer chases back quickly, while the full-back has pushed higher and is in a position to press the pivot also. Pressure is applied from both sides, and so Leipzig win the ball back, and because of their structure, they always have at least three players in higher positions usually to counter attack with. Leipzig were able to get their goal early in the first half and then relied on their sturdy defensive shape to get through the game.

Leipzig’s possession play

Leverkusen also used an aggressive high press in their 4-2-3-1 system, however Leipzig’s vertical and more direct play allowed them to overcome the press more than Leverkusen were able to. The system didn’t change between formations for Leipzig, and concepts such as overloading to isolate were used to good effect by Nagelsmann. We can see an example here where the right central midfielder, the pivot and left central midfielder all occupy one side of the pitch, while the ten Nkunku moves higher and wider to the other side. This overloads the left side of Leverkusen and forces a centre back to be engaged by a Leipzig central midfielder, and so when the ball is switched to Angeliño (off screen), he has acres of space to run into and combine with Nkunku.

Leipzig would also often exploit the orientation of the Leverkusen central midfielders, who would often be quite strict in their man to man pressing. We can see an example of this below, where Marcel Sabitzer drops wide and is followed by a central midfielder, leaving the half-space open for Nkunku to drop into. Leipzig basically had a midfield diamond at times, and so they could also overload the Leverkusen midfield.

Leipzig often looked to play more direct though, and so would attract the press from Leverkusen before going over it. Here we see Leverkusen get quite man oriented in midfield again and press very high, and so Mukiele lofts the ball over the top of the Leverkusen midfield. The Leipzig midfielders deliberately drop deeper to increase this space between Leverkusen’s lines.

Because of this space then, when the ball is played direct, a player can drop off and receive the ball freely, as Sørloth does here. Players such as Angeliño and Sabitzer are then ready to exploit the far side and get in behind with up, back, through combinations.

Here in the 4-2-3-1, Tyler Adams draws his marker forward and then spins to pick up the second ball from the striker, before then playing into Angeliño who is high and wide. These concepts allowed Leipzig to be more of a threat in the game than Leverkusen, but they also probably didn’t create as many chances as they would have liked in the game.

Conclusion

Overall then it was a bit of a signature Nagelsmann vs Bosz affair, with a key pressing battle and two teams stifling each other well with their tactics. Neither manager will have been upset with their teams performance, but Peter Bosz will certainly have been unhappy with the offensive aspect of his side’s play, as they just simply couldn’t find and execute solutions to Nagelsmann’s change in shape.

Comments