RCD Espanyol were relegated from La Liga at the end of the 2019/20 season. Possessing the desire to excel in the 2020/21 Segunda División, the new manager Vincente Moreno was appointed to change the situation. And now, three matches have been played and they have gained seven points with two wins and one draw. They’ve scored five goals with no goals conceded. With these basic stats in mind, it’s worth taking a closer look at their offensive tactics this season.

In this tactical analysis, we will first give you some basic information about RCD Espanyol. Then we shall detail their offensive tactics in different stages of play in this scout report.

Overview

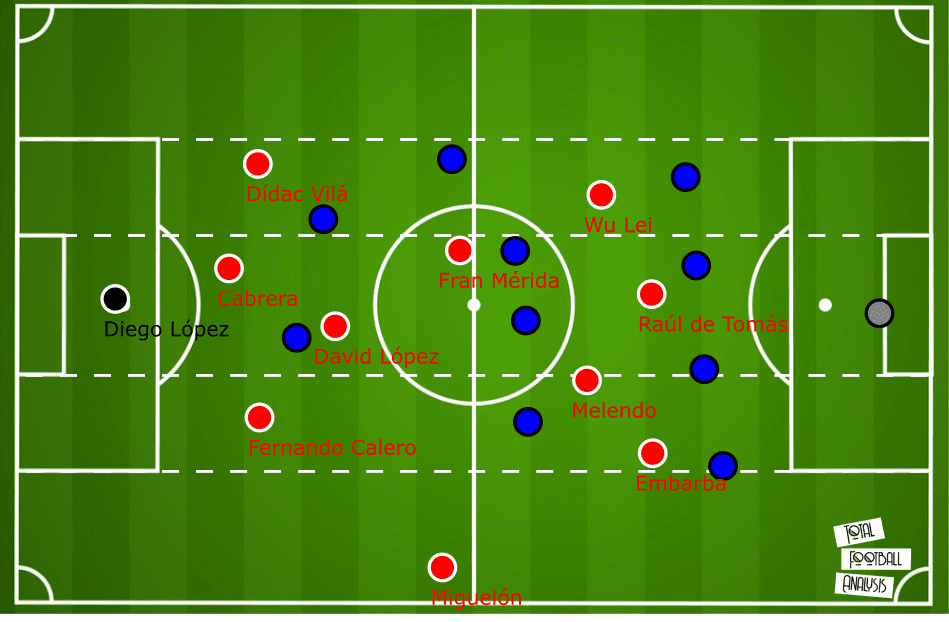

RCD Espanyol utilise the 1-4-3-2-1 system and according to each player’s role and responsibility in possession, the offensive shape will be more like an asymmetrical 1-3-3-4 as shown below:

In this system, they manage to play short-passing games in the league with 56.5% possession in their favour. Their average passing length is 18.98m, the shortest in the league, which means the support between players are good enough. And the support is created by the system and the traits of the regular starting 11.

The regular lineup that could bring passing support to the team would be: Diego López as the goalkeeper; Miguelón as the right-back; Fernando Calero and Leandro Cabrera both as the ball-playing defenders, crucial in the first stages. Dídac Vilá serves as the left-back and will join to form a three-back in playing out from the back; David López and Fran Mérida are two pivots, but López would take the role as a number six while Mérida is more like a number eight. Adri Embarba, Óscar Melendo, Wu Lei and Raúl de Tomás are the four-man attacking unit. Wu Lei is the inverted left-winger and Embarba is the right-winger who has the flexibility of inverting or providing width. They are crucial in supporting the first stages of attack. Melendo is the number 10 and De Tomás is the striker. The role of each player is important and will be detailed in the next sections.

The regular substitutes would be: Marc Roca replacing one of the pivots, Sergi Darder replacing Melendo to be the #10 and Matías Vargas replacing one of the wingers. These substitutes have different traits compared to the starting players and they can provide some tactical flexibility to the team in the second half, but we won’t delve into it in this analysis.

With the regular starting 11, they have played three matches and all were against 1-4-4-2 defensive shapes. They managed to score five goals and no goals were conceded with two wins and one draw. With all this information now known to us, we will now dissect RCD Espanyol’s offensive play and see how their offensive tactics affected the game in this analysis.

Playing out from the back

In this stage, the main objective is to find López, the number six player, who has the positional advantage of facing forwards without pressure. Then López will play safe to the number eight, Mérida, who later dictates the play and serves as the trigger for midfield penetration.

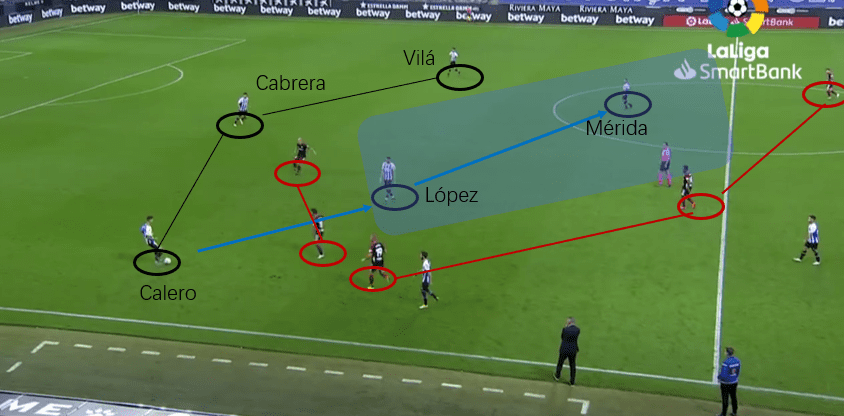

To achieve this, there are basically two patterns which are determined by ball-possession in different areas in the backline. The first patterns are activated by the ball going to the right side of their own half, mostly the right centre-back Calero. In this case, the left-back Vilá would stay to form a back-three in order to create a numerical advantage of 3v2 when against the 4-2 pressing block. The right-back Miguelón will push higher in front of the opponent’s midfield line as a simple pass option for the ball-carrier, but this passing pattern didn’t appear often.

The number six López would position himself near the three-man line, hiding a bit higher off the shoulder of the first two-man pressing line. This is to support the ball circulation in the backline. Then, the number eight player Mérida also stays in between the first two pressing lines, but his position is much higher than that of López. This is to “pin” the opponent’s midfield line to a higher place to create more space between the lines, for either López or Mérida to operate when they get the ball.

As the right centre-back Calero possesses the ball, if there are chances to receive the ball directly from Calero and face forwards with the first touch, López will shift towards the ball and find a pocket to receive.

As you can see from the above image, the position of each player is manifested clearly. The back-three was formed by Vilá joining the central defenders. López stayed close to the backline and Mérida was positioned much higher in front of the opponent’s midfield line, “pinning” them and creating huge openings between the lines.

In the above scenario, López managed to find a passing lane to split the front-two for their errant positioning. He opened his body in advance and scanned the pitch. With a huge opening between the lines, he was picked by Calero and turned to face forwards unpressed with his first touch. The first pressing line was bypassed and he then picked Mérida’s strong foot with his next touches.

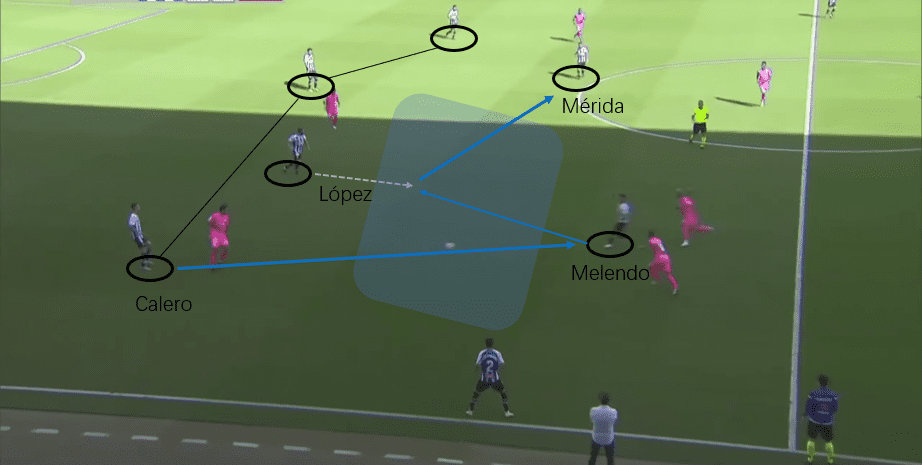

Nevertheless, if López can’t be reached directly and turn with his first touch, a crucial third player is used to activate the “facing forwards unpressed” scenario for López. The third player is Melendo. His original position is between the midfield and defensive lines near the half-space. His well-time dropping in front of the opponent’s midfield line and one-touch passes under pressure are great weapons to free López. His dropping will help change the angle of passing to López where the opponents are hard to cut off.

In the above example, Calero couldn’t find the passing angle and channel to López. Therefore, he enticed the opponent to press, creating more space for López to receive later. Melendo read the game and timed his run in front of the opponent midfield line. He then linked the play to López with one touch, and the dynamic of play was maintained as López could face forwards unpressed. López then picked Mérida with one touch and the play was brought into the next stage.

These are the first patterns that occur for most of the time in bringing the play into the next stage. And the second pattern will be developed in the left of the pitch, when the left centre-back Cabrera has the ball, but these patterns didn’t occur as many times as the first ones. In this situation, Mérida will drop to form the back-three. This helps free the left-back Vilá to push higher.

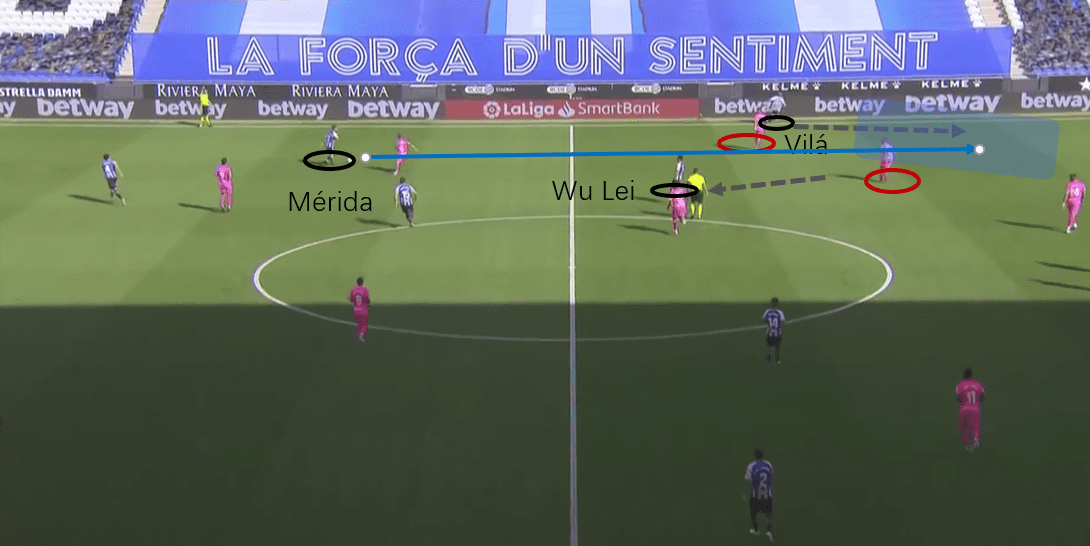

With Mérida playing like a regista to dictate play in the backline, Vilá will push higher behind the opposition midfield line, while the inverted winger Wu Lei will run towards the ball but still stay between the lines in a synchronised manner. These two runs shall provide Mérida with two forward passing options and generate confusion for the opponent’s winger and full-back because they don’t know whether to track players or protect space.

It also forces the opponent’s flank unit to communicate and if they fail to do so or hesitate in their decision-making, the play can be developed directly into the final stages to Vilá.

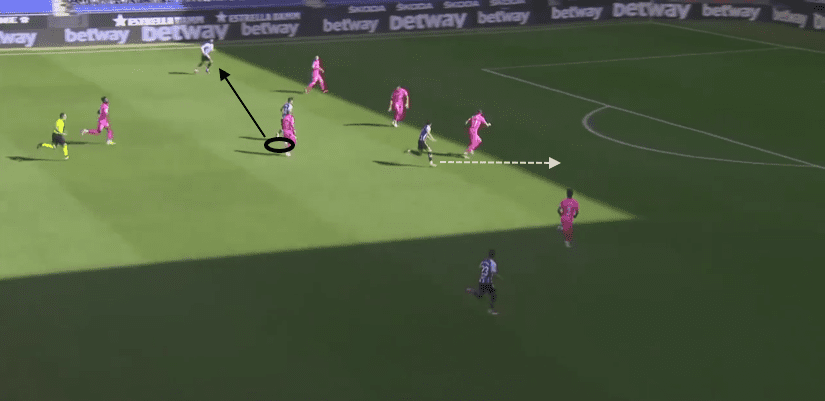

The above example shows us the pattern. Wu Lei dropped deeper, aiming to serve as a forward passing option, but his body shape was closed. His run drew the attention of the opponent right-back, creating space behind the defensive line for Vilá to attack into. The opponent’s right-back tracked Wu Lei for a few steps and hesitated since he didn’t know whether to follow him or not.

This gave Wu Lei space to receive from Mérida. On top of this, the opponent’s right-back and right-winger seemed to lack communication as the winger didn’t mark Vilá tight. As the right-back still hesitated on whether to drop to protect space or track Wu Lei, Mérida hit the pass over the lines to find Vilá in the space behind the defensive line. The play was brought into the final stages.

Midfield penetration

For most of the time, with Mérida receiving from López or Mérida orchestrating in the backline, the play is brought into the next stage – the midfield penetration. In this stage, two dropping inverted wingers, Wu Lei (often rotating with De Tomás) and Embarba are the main target players to bring the play into the next stage. Their touches are crucial in referencing the direction of the attack. Furthermore, occupying the half-space channel could also clear flank paths for full-backs to run into and add another option for Mérida to pick, and it’s much like the example we gave in the above section. So we won’t discuss finding the full-backs in this section.

Before dissecting the scenarios of how inverted wingers participate in this stage, a couple of details are worth mentioning. Firstly, as the inverted wingers drop towards the ball, they could utilise the closed body shape. An open body shape is no longer required. This is because the closed body orientation could hide the intention of how wingers are going to take the first touch, as the open body shape towards the inside/ outside would show the opponent where they are going to go next. This increases the unpredictability of the attack but it requires players to constantly scan the pitch to make the best decision. Secondly, all executions are ideally done with just one touch to exploit the dynamics and timing of the play.

Now let’s delve into two situations of finding inverted wingers through midfield penetration. The first one will be when the inverted winger latches onto the pass and takes his touches inside. In this scenario, the first option will be to find the number 10 player, who faces forwards and is ready to release final passes in the centre.

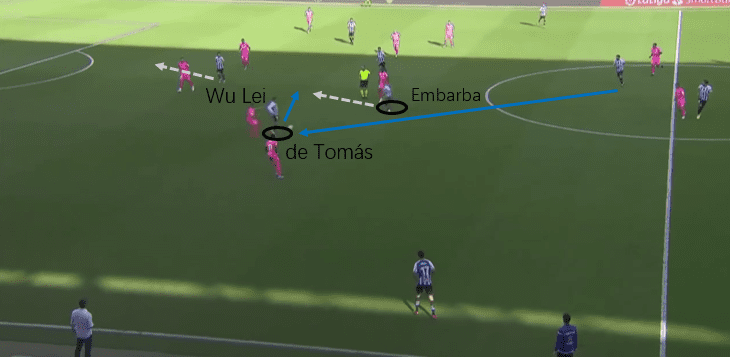

Above is an example of taking touches inside to find the attacking midfielder. In this scenario, the front-four rotated their positions with Wu Lei as the striker, De Tomás as the inverted left-winger and Embarba as the number 10. De Tomás latched onto the ball with a closed body shape, hiding the intention of his first touch. He scanned the pitch and saw Embarba running forwards, so he decided to lay off the ball to him, the number 10 in this scenario. Then Embarba received between the lines, ready to shoot on goal as Wu Lei ran behind the defensive line to stretch the play.

Also, the winger could switch the play after taking touches inside. This is normally done on the left half-space, switching to the right-back Miguelón. Miguelón could then hit a high-quality cross in a huge opening with the opponents still shifting blocks to restrict him.

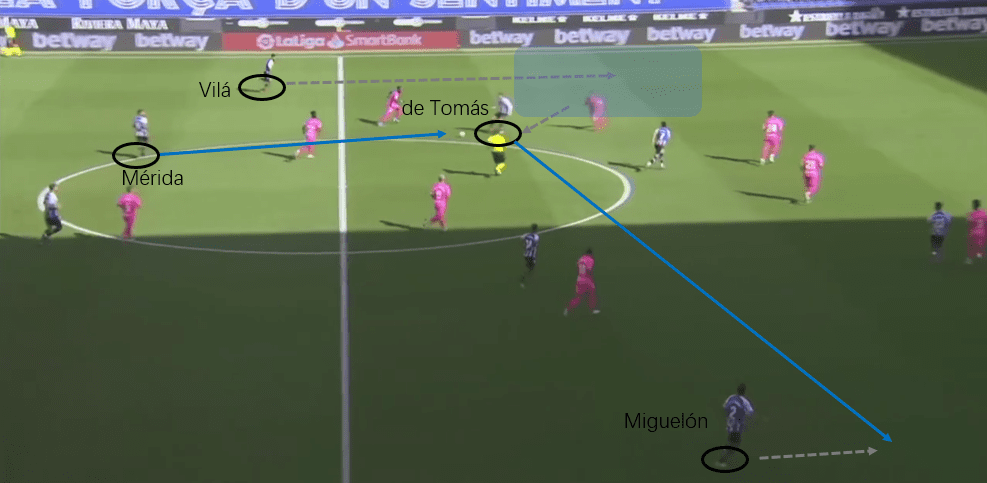

The above image shows us the scenario of taking the first touch inside to switch the play. Again De Tomás rotated with Wu Lei and served as the inverted left-winger. He ran towards the ball, freeing the space on the left-flank for Vilá to run into, who served as another forward passing option. Mérida picked De Tomás and he took his first touch inside, switching the play to find Miguelón in space with his next touch, creating a high-quality chance.

The first touch inside could create a lot of problems for the opponent, whereas the traits of players would adversely affect the level of threat in this tactic. For example, Wu Lei’s off-the-ball movements are well-timed, whereas he can’t execute one-touch passes to the number 10 when his first touch is towards the inside. He needs to take some extra touches to adjust and this kills the dynamic of play, as well as giving the opponent time to recover.

Then we’ll discuss the scenario of taking the first touch outside of the wingers. As the winger takes the first touch outside towards the flank, he’ll release a simple pass to the full-back on the same side. Though the end product is the same as Mérida directly picking the full-back, the amount of free space the full-back could utilise is of tremendous difference, due to the principle of “first centre, then the flank”. Using an inverted winger as the link player will naturally instigate the opponent to cluster in the centre, leaving the flank area free, while directly picking the full-back doesn’t enjoy such amount of time and space.

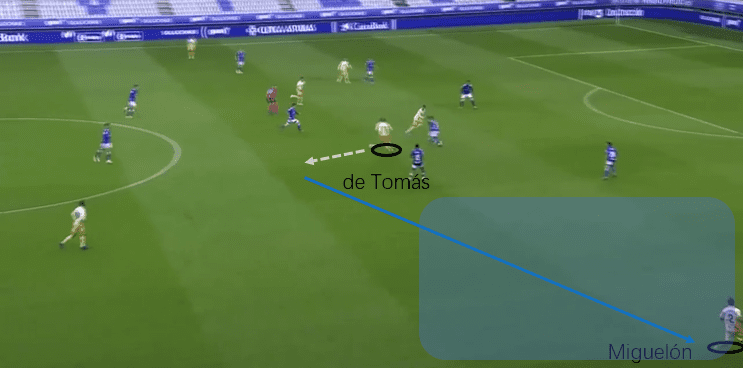

Above is an example of taking touches towards the flank. Though De Tomás, deployed as the right-winger in this scenario, took his first touch backwards, he managed to turn and connect with the right-back. There was a lot of time and space for right-back Miguelón to exploit due to the movement of the inverted winger. Miguelón was then able to cross accurately into the box.

Final passes and finishing stage

The aforementioned patterns imply that the majority of end products in midfield penetration will be finding full-backs to cross. In the final stages, the aim is to create an isolation in a 2v2 scenario inside the box. Crosses will be delivered early into the space between the defensive line and the goalkeeper. Also the crosses will be aimed at the far post, on the blindside of the whole defensive line.

This is determined by the characteristics of the front players. They are not tall but they are pacey and mobile enough to go for tap-ins with the likes of Wu Lei. Also, they want to clear the central spaces and remove the opponents to vacate the space in the box, where players like Wu Lei and De Tomás could have more room to accelerate and try to be the first to access the ball. On top of this, aiming at the blindside of the defensive line could force the opponent to make mistakes in defensive turning or positioning. Then Wu Lei and other players could take advantage of this.

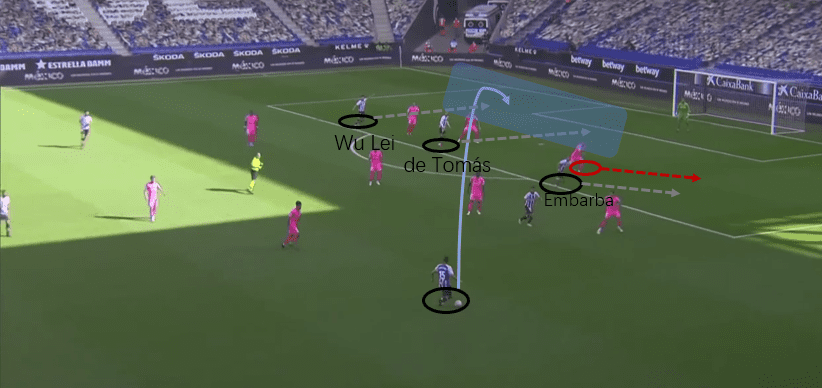

The above image is an illustration of this. Embarba ran diagonally to draw the opponent’s left centre-back out of position, clearing the box for Wu Lei and De Tomás to receive the crosses. Then the crosser aimed at the space between the defensive line and goalkeeper at the far post. Wu Lei started from the blindside of the right-back. He ran to fight for the first access to the ball and he managed to do it. He tried to put the ball in the centre but it unfortunately was cleared by the defender.

While the crosses are the major method for final passes, the actual effect is not very good but still decent as the accuracy is at 27%. Still, the lack of height in the opponent box is a big problem for Espanyol when the opponent tries to defend in a low-block.

However, let’s not forget the inside touch of the winger to find the number 10. If the number 10 gets the ball between the lines, usually it’s the trigger for giving penetrative passes to create finishing chances. However, the starting number 10 Melendo lacks the ability to give killer passes when he possesses the ball facing forwards between lines, as his key passes per 90 is 0.

From the above image, we can see that the front-four were in the final stages of the attack. Melendo was on the ball and Wu Lei was running onto space behind the defensive line, providing a final pass option. However, Melendo took his touch outside and it seemed that he lacked the confidence to give the penetrative final pass. He picked the player on his left and missed the opportunity to directly give a final pass.

Thus, Dader could be chosen instead as his key passes per 90 stand at 0.54, whereas his timing in dropping into space is poor. Hence, this is the trade-off that Moreno has to bear.

Final remarks

Vincente Moreno certainly brought a lot of changes to RCD Espanyol’s tactics. The flow of the play is fluent and the combination between players is good. However, as they only encountered a 1-4-4-2 defensive shape in these three matches, it’s still questionable whether the team could perform at a high level against different defensive shapes.

Recently, former Manchester City Academy player Nabil Touaizi was brought to the team. We could expect this newcomer to bring some changes to the team. As they are eager to go back to LaLiga to compete with teams like Real Madrid and Barcelona, we shall continue to see the changes in their offensive play over the course of the 2020/21 season.

Comments