Grêmio and Renato Portaluppi (known as Renato Gaúcho) are inseparable. Other than one forgettable year playing for Serie A’s Roma, Renato spent most of his career playing in Brazil’s top clubs. Although his path began at Grêmio, his playing days are always associated with clubs from Rio de Janeiro, with spells at Botafogo, Flamengo, and Fluminense.

In his first few years as a manager, his love story with Rio continued, bouncing back and forth between Vasco da Gama and Fluminense. His managerial trajectory continued with insignificant stints throughout the country until 2016, when he took over Grêmio for the third time as a manager.

This was the beginning of a historic four and half year era, which included a Copa do Brasil and a remarkable Copa Libertadores title. The two parted ways at the beginning of 2021, and that same year, Grêmio were relegated to the second division.

Struggling for promotion in 2022, Grêmio called a familiar face, and Renato took over the Porto Alegre club for the fourth time. The 60-year-old led them back to the Série A, and after an incredible transfer window, which included the signing of former Barcelona and Liverpool marksman Luis Suárez, Grêmio have yet to lose in 2023.

In this tactical analysis, we will examine Grêmio’s tactics under Renato Gaúcho and identify how he’s turned them into one of the most exciting teams in South America. This analysis will not only provide a detailed breakdown of their tactics in possession but also take a look at how their aggressive defensive system is helping them dominate games.

Structure

Although there are occasional changes to the structure, since 2016, Portaluppi has predominantly used his favourite 4-2-3-1. One of the most common formations of the last decade, the 4-2-3-1 provides great balance vertically and laterally, and it is perfect for the way the Tricolor play. As we will examine in the next section, Renato’s tactics are very reminiscent of free-flowing Brazilian football, jogo funcional (functional play) in its essence.

It is not as extreme as Fernando Diniz’s Fluminense, and positional references are still quite significant, hence the 4-2-3-1 mention. However, it is still very much a jogo de aproximação (game of approximation), where passing distances are much shorter and immediate relations between the players are very common. The 4-2-3-1, curiously what Diniz also uses, allows for an initial distribution of players which facilitates this multidirectional approximation game.

Naturally, with such an approach, the overall structure tends to be extremely narrow. Going into individual sectors, we can identify some tendencies. The double-pivot moves in unison, always close to one another. The movement of the fullbacks has many variations. The left-back Reinaldo can move into the midfield as well as provide width. On the right, former Man United fullback Fábio tends to stay wide more often than not.

The central attacking midfielder is the centrepiece of the structure, always surrounded by various players. Often the most creative player, he is able to combine and instinctively interact with teammates nearby. In 2017, Luan was this number 10, and since leaving Renato, he has struggled to find his Grêmio form. Similarly, Ganso struggled to perform for years until finding Diniz.

Additionally, in this 2023 side, Bitello has been a free-roaming winger, which often leads to asymmetric structures as seen below. Although the positional references are still there, in cases like Bitello, there is great freedom to roam and occupy spaces based on the player’s live interpretation.

Renato Gaúcho’s Grêmio adopts a very narrow 4-2-3-1, encouraging multiple immediate passing lines, positional rotations and fluidity, and constant approximation. Some players will naturally roam the spaces more than others, but the core structure is usually maintained. Although it is not extreme as Diniz’s, it is still traditional Brazilian functional play. But how does it play out? Let’s take a look.

Functional play

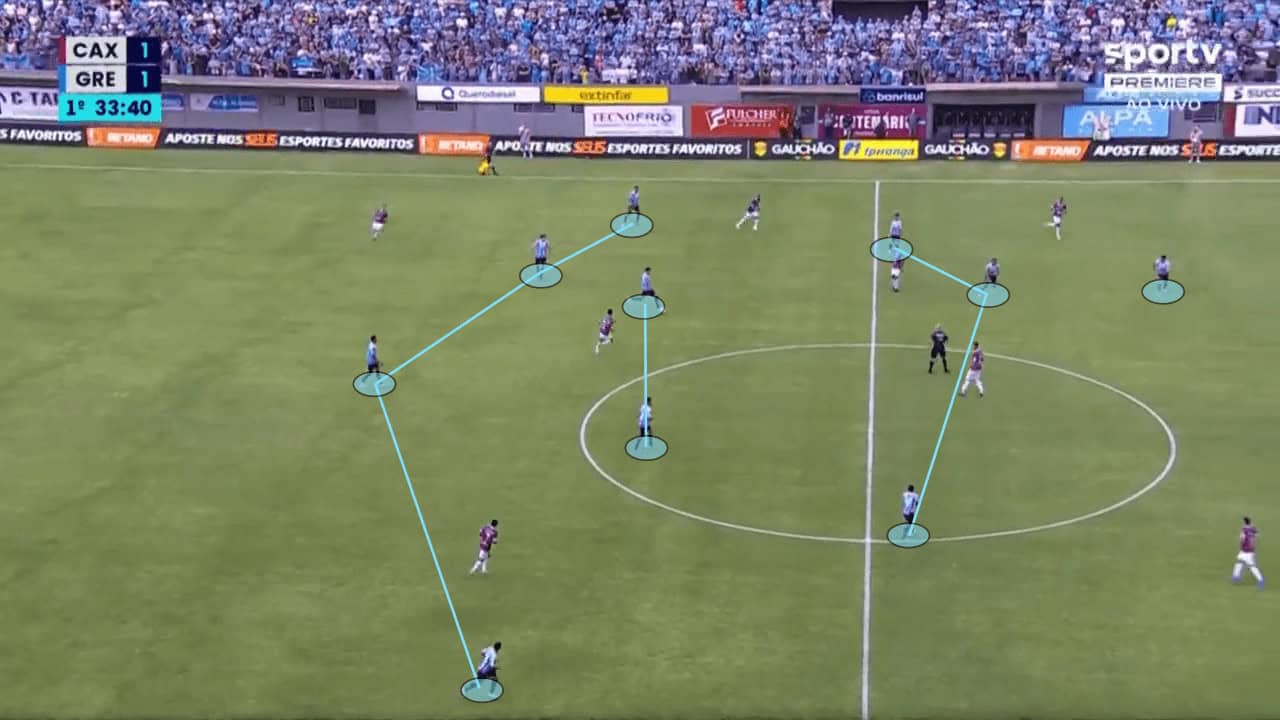

Given Grêmio’s stronger positional references, it is much easier to identify some dynamics of Renato’s side. As mentioned, the double pivot always moves in unison, and in the example below, it is no different. As the centre-back has the ball on the right side, the two shift to provide immediate support.

Ahead of them, the attacking midfielder drops in to provide further support. The right winger checks in to receive the ball while the right back maintains maximal width while pushing forward. Finally, Suárez also drops to create a more vertical passing lane.

With all of these players, the centre-back has six players ahead of him to collectively progress forward. He is able to find the more vertical option in Suárez, and as the Uruguayan controls the ball, he already has immediate options around him.

In another instance, we are able to see an emerging pattern. As the left-back has the ball, the attacking midfielder checks in before immediately checking out of that space. As he does this, Suárez checks in for a more vertical option, which was created by the 10’s movement to drag the defender.

The ball is the primary reference for the players and considering the opposition players, they will move in and out of spaces to create passing options. The initial approximation is obviously key, but the subsequent movement away for another player to appear is just as important. It maintains a fluid system where space is alive, appearing and disappearing.

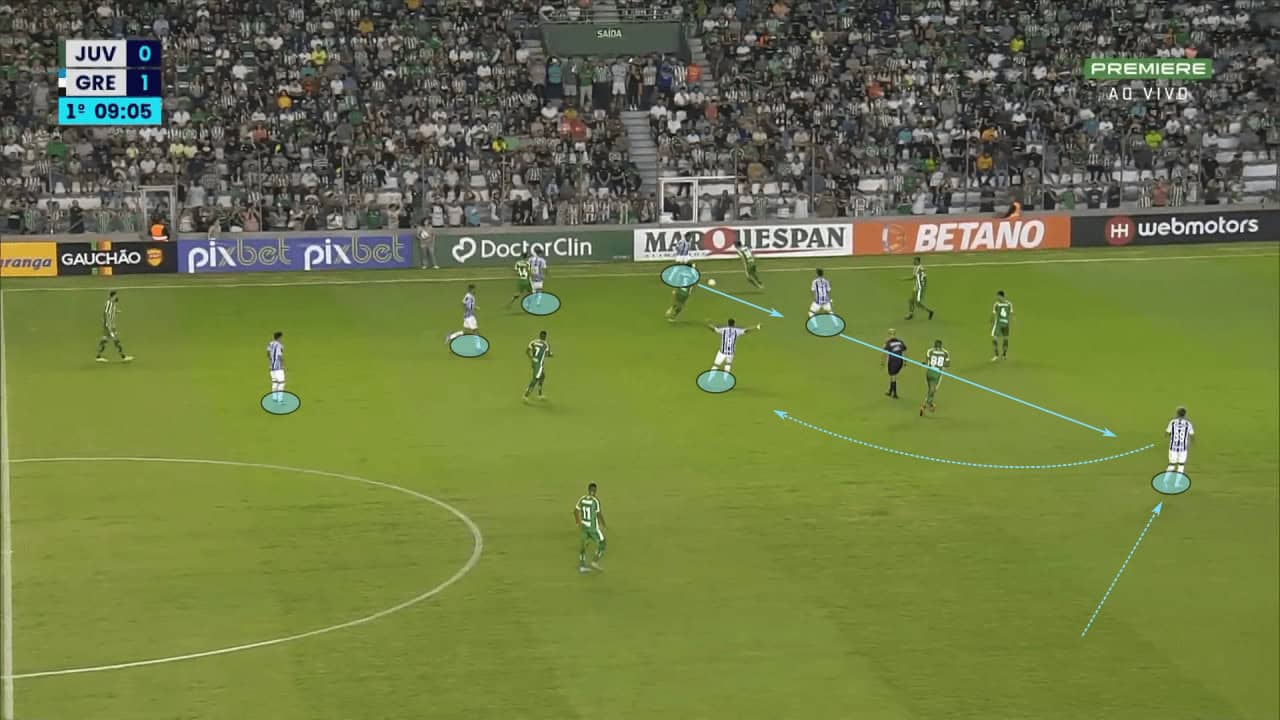

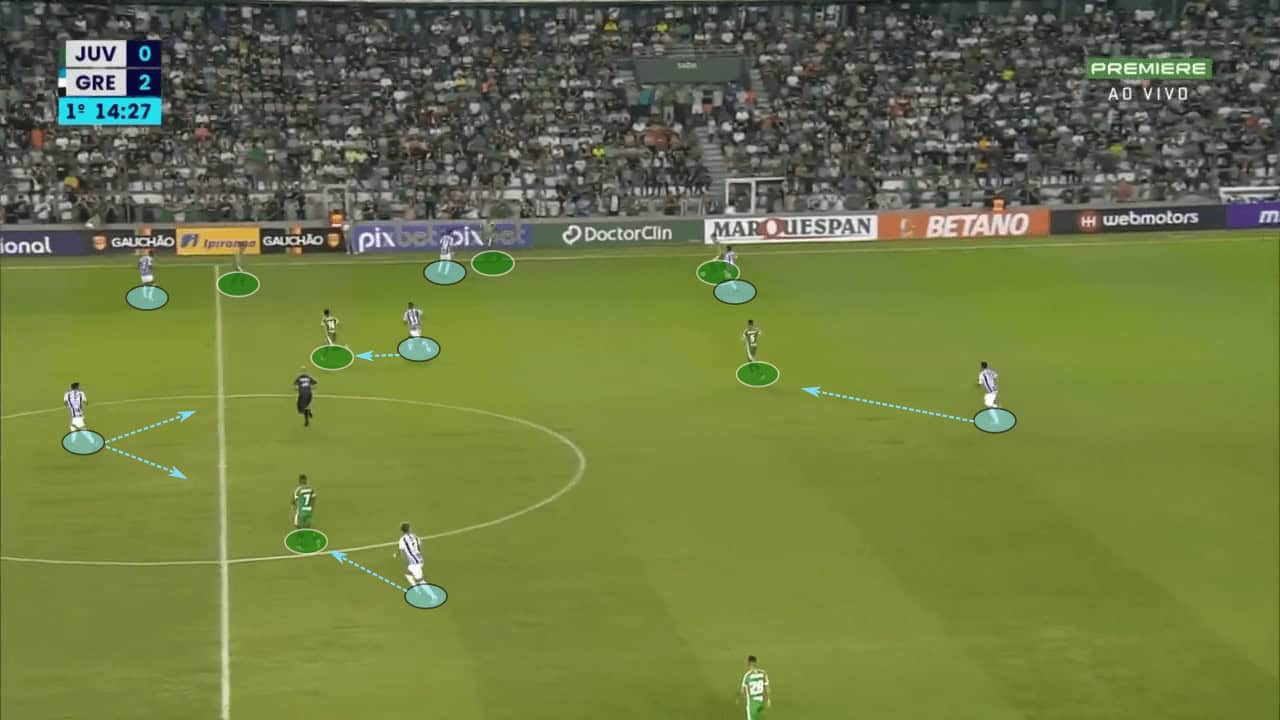

Against Juventude, there is a more extreme example of approximation. As they progress on the left wing, the ball carrier has four teammates around, including Suárez who has dropped in from his number nine position. The right winger, Bitello, moves up to occupy the space left by the Uruguayan.

The left-back, who is the ball carrier, finds the left winger, who then turns to find Bitello occupying the number nine position. Juventude have seven players in that area alone, so when Grêmio play out to Bitello, he is in a very dangerous situation.

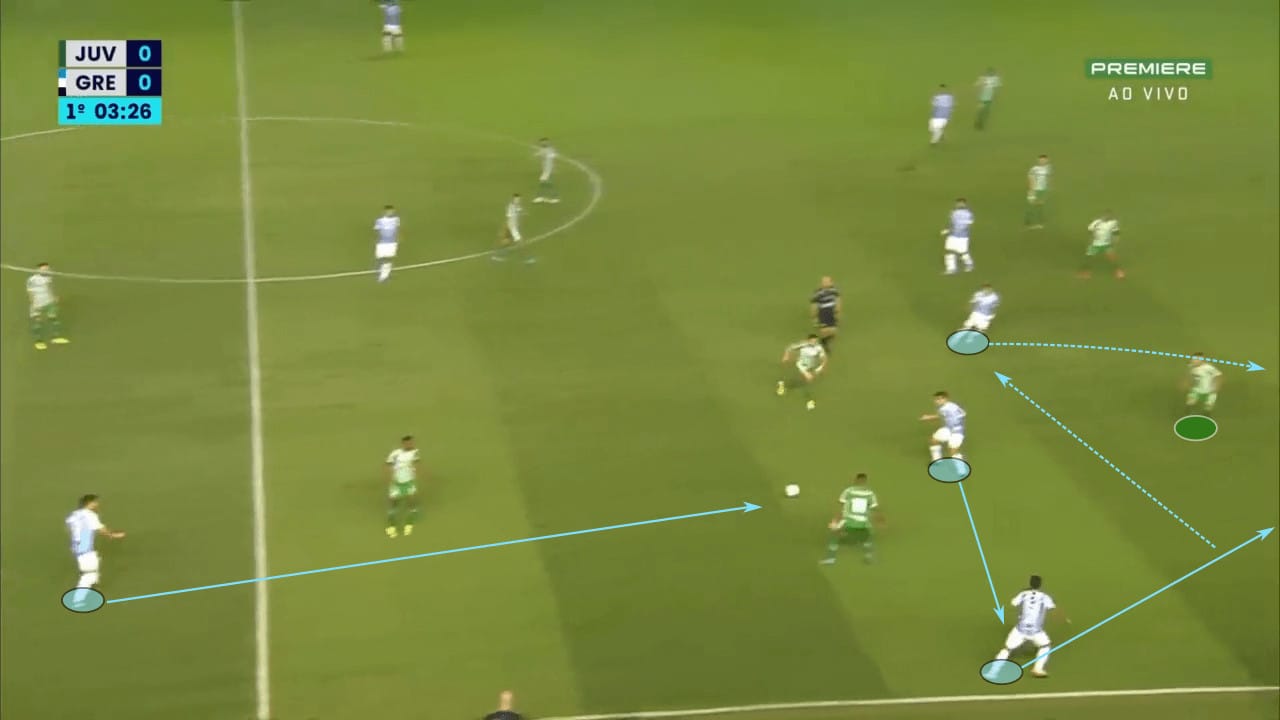

In this final example, we can see a clear example when they try to attack through the middle. One of the defensive midfielders has the ball while the other is right next to him. The two wingers are extremely narrow, splitting the number 10. Right next to him, Suárez is the number nine.

Such a minimal structure is quite unusual, but it is the essence of functional play – a significant concentration of players in a small area, where interpretive relations and movements are enhanced.

Wide dynamics

The wide fluctuations are another feature worth noting, and it dives into the topic of dynamic width. Often in football, we see a team maintaining width through the fixed position of a wide player, usually hugging the touchline. While static maximum width has its benefits, and it is something that Renato uses, dynamic width provides another alternative.

The wide players, especially the wingers, tend to fluctuate between the touchline and the edge of the half-space, going from minimal to maximal width and creating this dynamic width in advanced areas. This movement does not necessarily have a trigger or a predetermined pattern. It is based on the player’s live interpretation, using the ball and the opposition players as references.

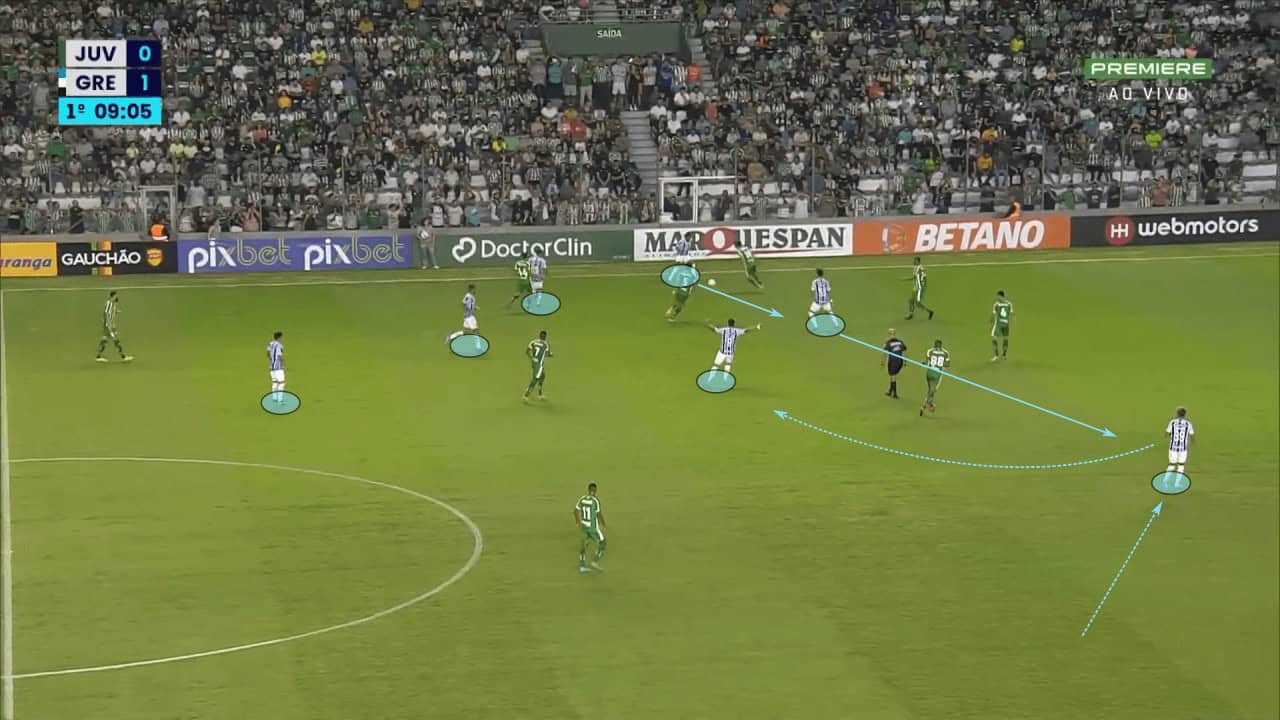

We can see an example of this against Juventude. The right winger drifts significantly inside, and the opposition’s fullback follows him. The attacking midfielder is able to find a vertical passing lane from the centre-back, and after receiving, he plays the right-back who is by the touchline. The right-back then plays the right winger in a diagonal run behind the backline.

In another instance, the right winger drops deep into the midfield to receive it from one of the defensive midfielders. Meanwhile, the other defensive midfielder moves forward to occupy the space left behind. The right winger receives it with time to turn and plays the defensive midfielder into the final third.

There is a lapse in communication between the Juventude defenders, and the fullback ends up coming inside to follow his man. Consequently, significant space is left behind and quickly attacked by Grêmio.

In this short segment, we can see a final example of this. Bitello once again fluctuates more centrally to play with two teammates. After a short combination, they find the right-back who has pushed up out wide. The opposition’s fullback is unwilling to initially commit wide, so Grêmio’s fullback receives the ball with time and space.

Once the fullback goes out to pressure Grêmio’s right-back, Bitello makes an underlapping run to receive it going into the opposition’s box. The inside fluctuations of the advanced wide player create a very interesting dynamic out wide, especially when combined with the wide fluctuation of other players from deep. This dynamic width creates uncertainty among the defenders and space to be attacked, often in optimal and dangerous angles. In order to be effective, this requires constant and fluid movement between the players.

Aggressive defending

In 2023, Grêmio have averaged an incredible PPDA of 6.75. Albeit against inferior opposition in the Rio Grande do Sul state championship, their aggressive defensive system is undeniable. Renato’s men press high and intensively from the very beginning, looking to win the ball back as soon as possible. This has helped them dominate games and average 58.4% possession this year.

This is done in a very flexible man-marking system, where their structure is often changing. To help 36-year-old Suárez up top, the attacking midfielder often joins the Uruguayan to press the two centre-backs. In other instances, one of the wingers can become this second centre-forward while the attacking midfielder stays in the midfield. It all depends on the opposition’s strengths, weaknesses, and structure.

In the image below, we can see Grêmio’s aggressive structure to press the opposition’s build-up. While some players have an immediate target, others have two possible ones. These are obviously farther away, and by the time the ball gets there, they will have teammates shifting over and providing cover.

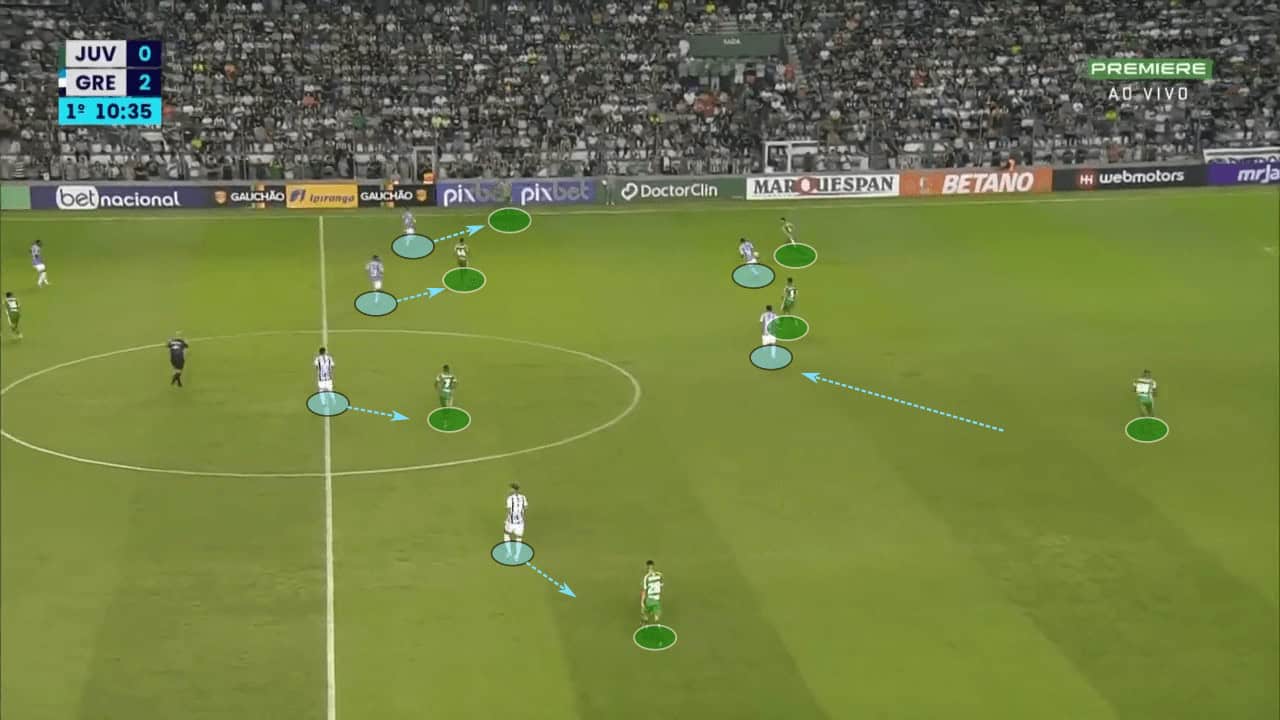

Against stronger opposition, such as Juventude, we can see a slight shift in approach. The front two now work together to mark three players, including the opposition’s defensive midfielder. Once the ball goes to one side, the opposite forward will shift inside to pick up the defensive midfielder.

This pattern can also be observed in a mid-block. As Juventude play to the right side, Grêmio shift their block to keep them boxed in and overwhelm them. To do this, the opposite forward drops in to pick up the defensive midfielder while everyone else has a player to mark.

In other instances, we can also see the opposite winger shifting inside to pick up the opposite central midfielder. This effort allows Grêmio to have an extra player in the midfield to provide cover, as highlighted below.

Grêmio’s defensive system is very flexible in its structure as it is very man-marking. The structure and patterns in marking heavily depend on the opposition. Nonetheless, some trends can still be observed, none more notable than its extremely aggressive nature.

Conclusion

In his fourth stint as Grêmio’s manager, Renato Portaluppi is assembling an extremely promising team for the 2023 season. Although it is their first season back in the top division, they have significantly invested in the squad and should be expected to challenge in the top half of the table.

It is no surprise that Renato’s tactics incorporate a traditional functional play, as it has throughout his whole career. Now with high quality at his disposal, this system will be extremely exciting to watch, perhaps one of the most interesting on the continent.

Comments