After suffering four straight defeats and going seven games without a win in all competitions, Julien Stéphan resigned from his role as Rennes manager on 1st March. Former Lyon manager Bruno Génésio, who most recently managed Chinese Super League side Beijing Sinobo Guoan, has now been set the unenviable task of succeeding Stéphan, who led Rennes to the UEFA Champions League for the first time in the club’s history and led them to their first Coupe de France win since 1971 in the 2018/19 season.

The 40-year-old evidently enjoyed plenty of success at Roazhon Park, however, while his tenure at the Brittany-based club will likely be remembered fondly, it’s clear that his final months in charge of Les Rouge et Noir were far below the standards that were set during his time at the club. Génésio is taking over a team that has fallen from a third-placed finish last season to 10th place just one season later, now sitting 21 points off the Champions League qualification places.

In addition to having the task of following Stéphan and the success he enjoyed at Rennes, Génésio must also try to reinvigorate this team, who are in the midst of one of the worst runs they’ve endured in recent years and get the ship steering back in the direction that Stéphan had them moving not that long ago.

In this tactical analysis, in the form of a scout report, we’re going to highlight three key areas in which Rennes have notably struggled of late. We’ll provide analysis of the main problems that caused their poor run in the lead-up to Stéphan’s departure, which will also be the key areas for Génésio to immediately address via his tactics on his Ligue 1 return.

Chance creation

The majority of Rennes’ trouble of late has come via their performance in front of the opposition’s goal, as opposed to their own goal. Les Rouge et Noir have scored just 33 goals in their 27 Ligue 1 games this term. Only five teams in France’s top-flight have scored fewer league goals than them, in total, at this stage of the season.

However, Rennes’ goalscoring record over the last 10 games makes for even worse reading. Firstly, only one team have earned fewer points than Rennes during this period, making them the joint-second worst performers in Ligue 1 over the last 10 games. They’ve scored just seven goals in those 10 games, though, which gives them the joint-worst goalscoring record for this period.

Evidently, their chance conversion hasn’t been anything to write home about of late, but their chance creation hasn’t been great either. At present, Rennes have got the eighth-lowest xG (36.51) of any Ligue 1 side for the 2020/21 campaign. Their failure to create many high-scoring chances isn’t for lack of trying, however, as they’ve also taken the third-highest number of shots per 90 (11.88) of any Ligue 1 side this season.

The issue is that while they’ve been taking lots of shots, their average shot hasn’t been given a relatively high xG value. Rennes have currently got the second-lowest xG per shot (0.107) in Ligue 1. This is down from their xG per shot of 0.119 from their successful 2019/20 season. This stat suggests that the average goalscoring chance that Rennes create during a game isn’t of very high quality, indicating that their poor performances in front of goal recently could be largely attributed to poor chance creation.

One method of chance creation that Rennes have relied on heavily this season has been crosses. In fact, Les Rouge et Noir have made more crosses per 90 (17.1) than any other Ligue 1 side in the 2020/21 campaign, maintaining the sixth-best cross accuracy (32.6%) of any Ligue 1 team in the process.

In this section, we’ll provide some analysis of Rennes’ crossing, examining examples of some of their more successful crosses and some unsuccessful ones, to try and determine how they could improve in this area to create better-quality chances more consistently.

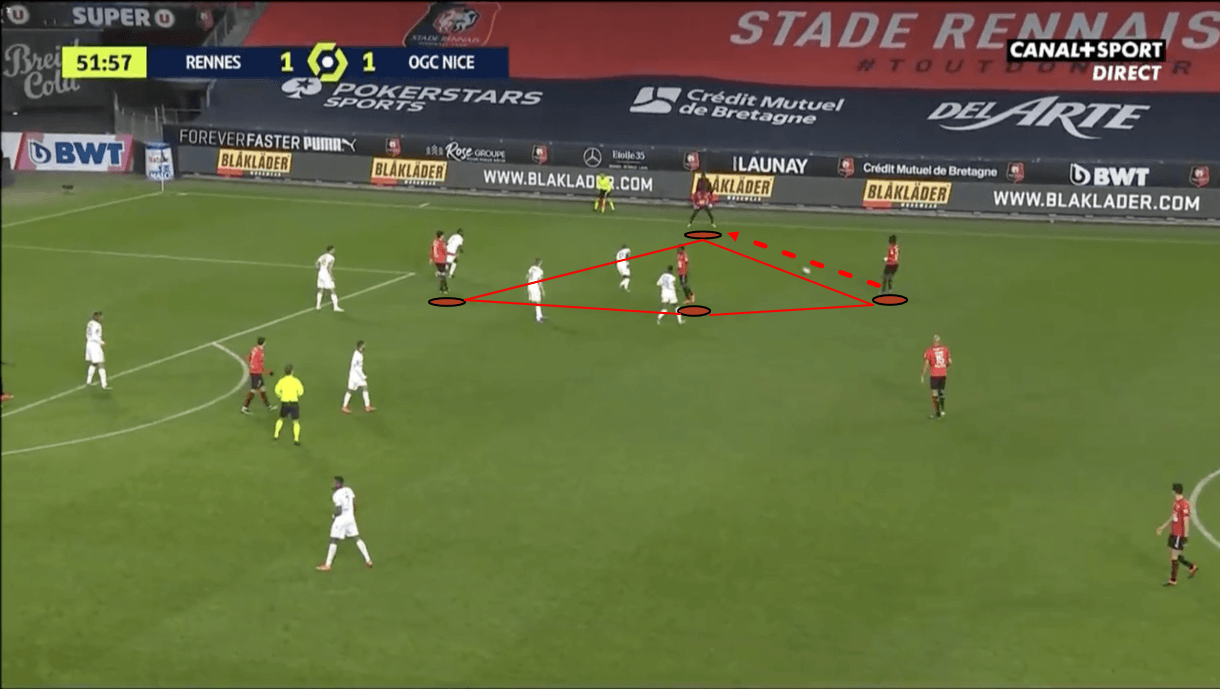

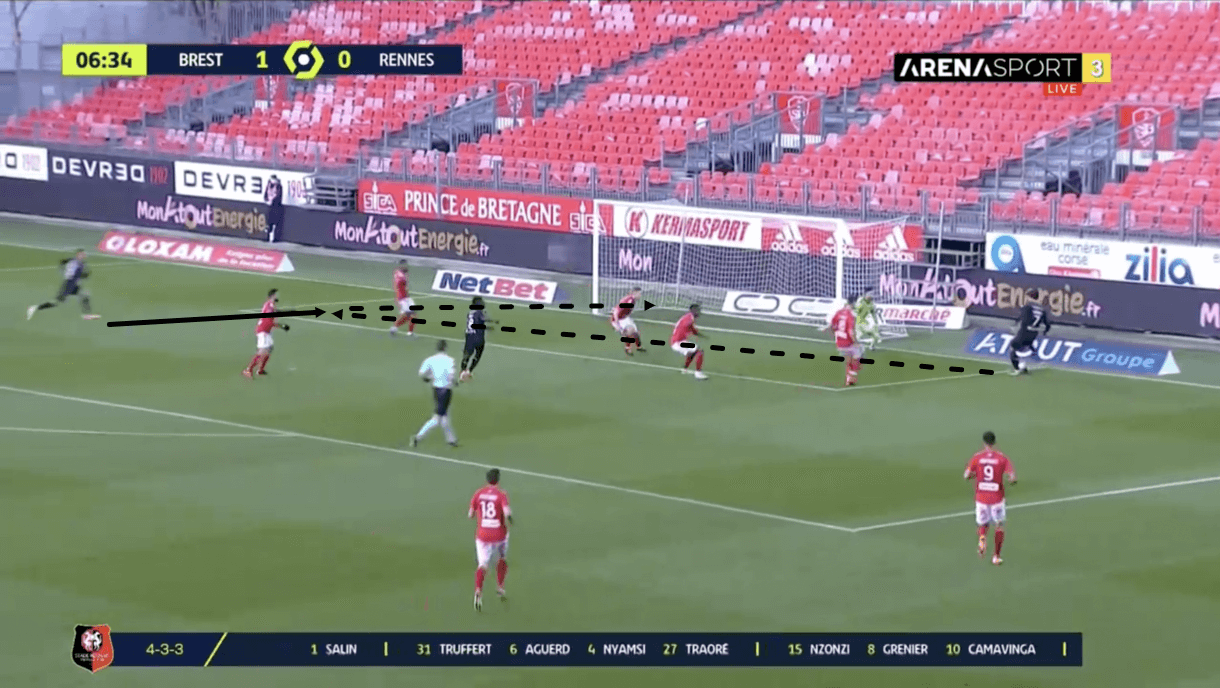

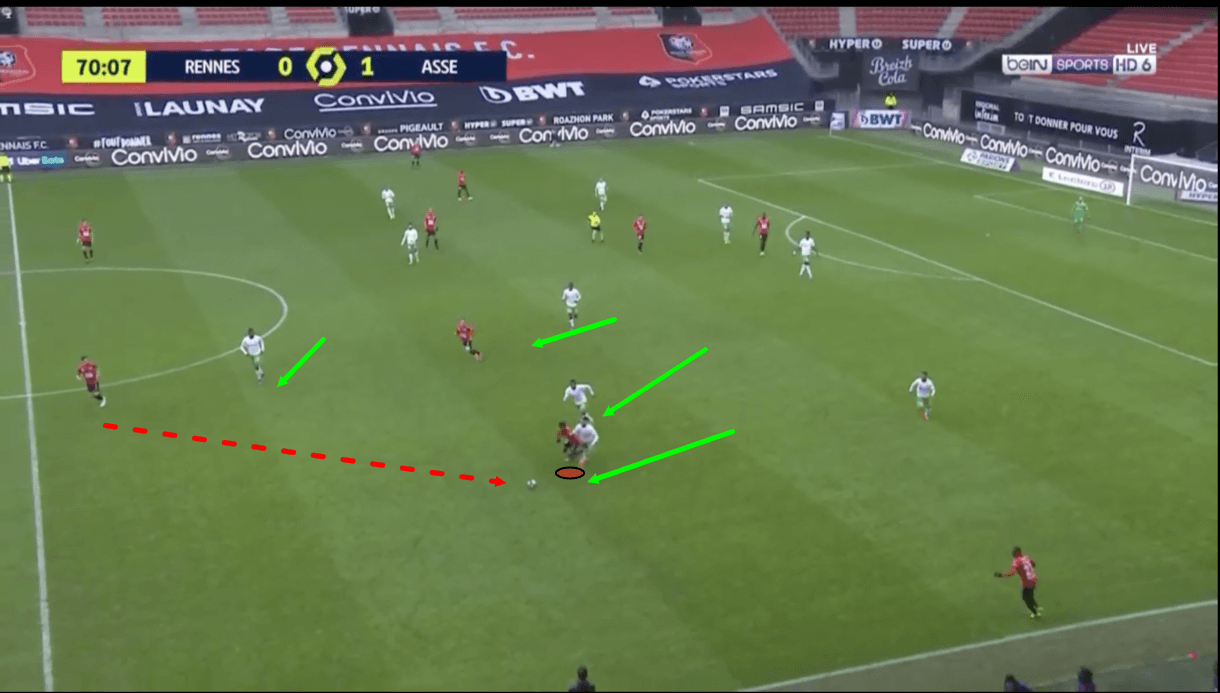

Rennes are generally very good at building into the final third and progressing play to the point where they can put the ball into the box. They’ve demonstrated plenty of creative tactics in possession to progress into the final third. One of these creative tactics involves Rennes forming a rhombus out wide to create an overload and safely progress into the final third, as we can see in figure 1.

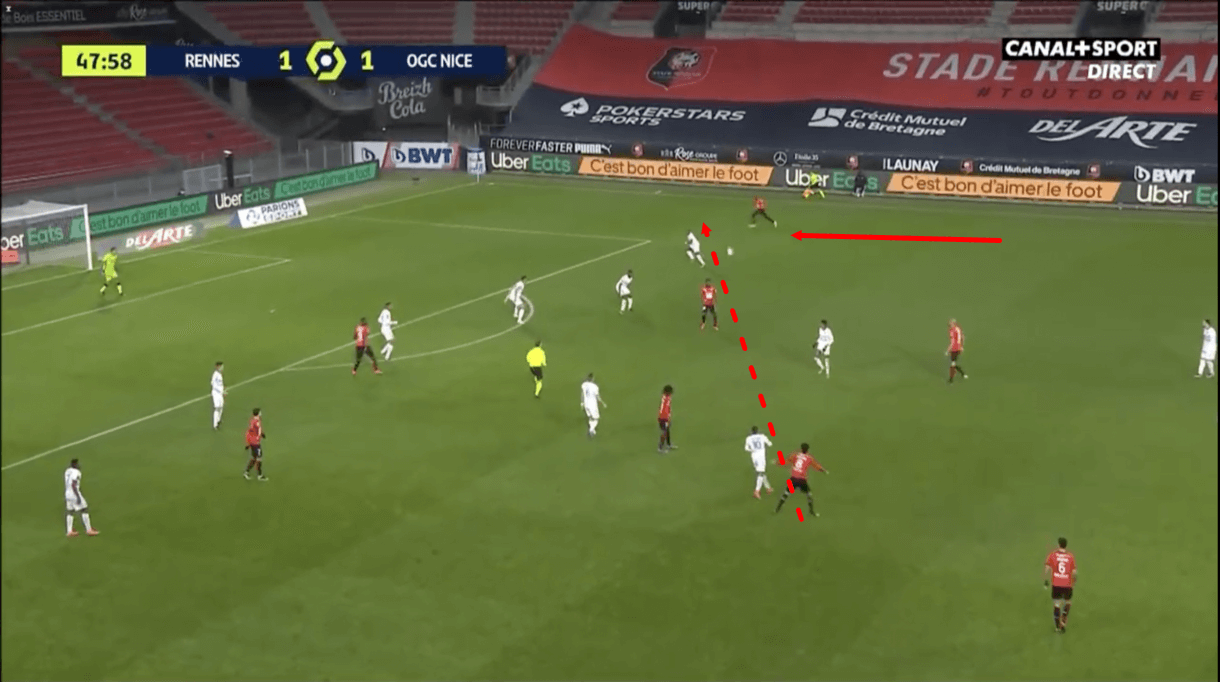

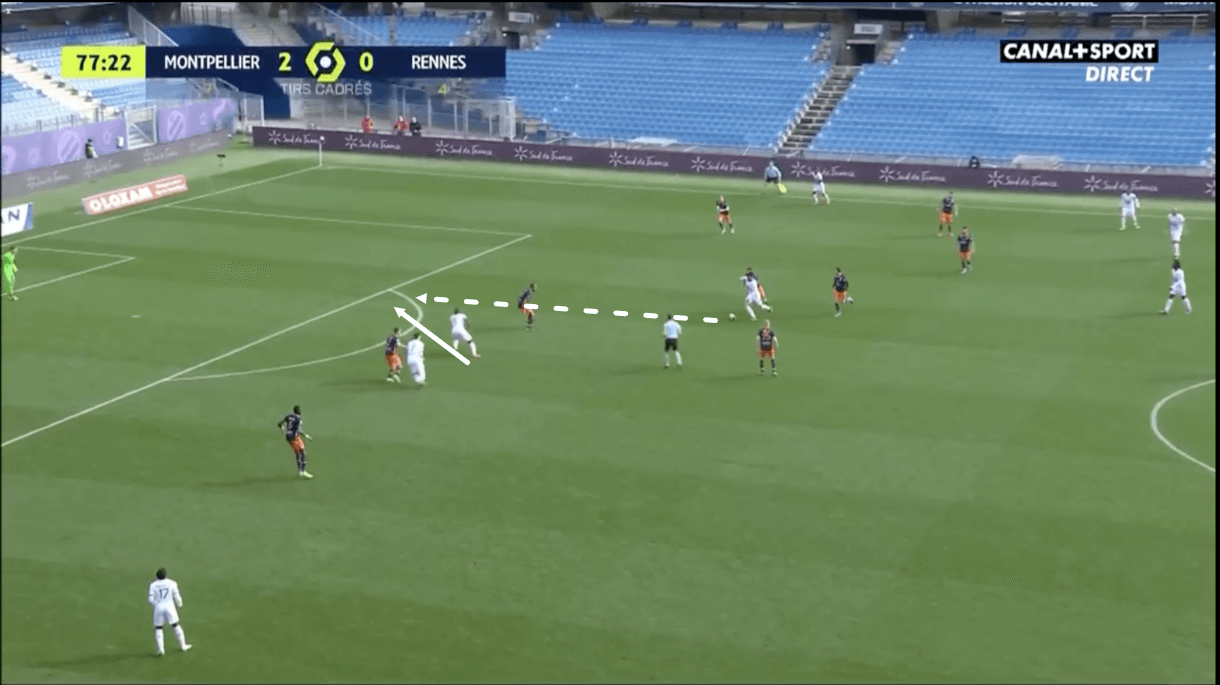

In figure 2, we can see an example of another creative way that Rennes commonly set up a crossing opportunity. Here, a crossfield ball is being played from a central midfielder on the left side of the pitch to the overlapping right-back. Rennes will attempt to pull this off on occasion if the space is there for the wide man and this quick switch of play can be very effective at quickly getting the crosser into position without giving the opposition much time to prepare for the incoming ball.

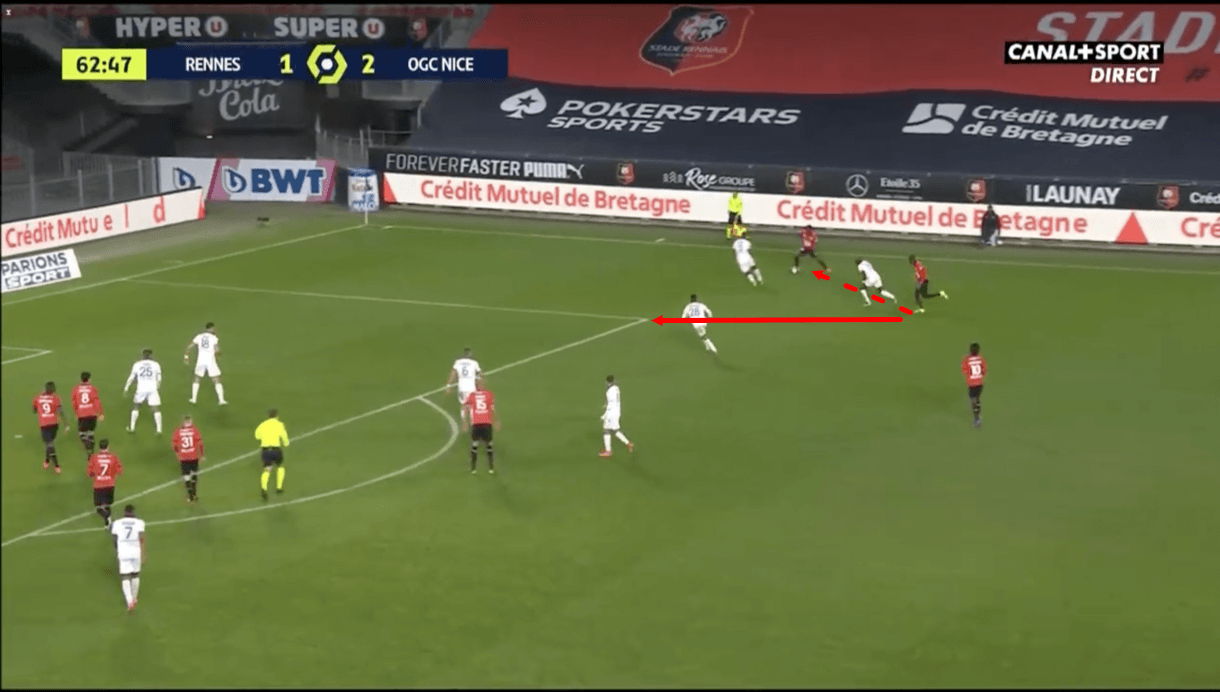

Lastly, figure 3 shows us one more example of a common way that Rennes build into the final third and into a crossing position. Here, we can see the right-back and right-winger linking up, with the right-back making an underlapping run. This movement is a regular feature of Rennes’ game and it’s proven to be a difficult one for plenty of their opponents to deal with.

These examples all show us that Rennes are a creative side in possession. They’re excellent at getting into the final third and into crossing positions, hence why they’ve played more crosses than any other Ligue 1 team this season. However, they’re often not as effective once they actually get into those crossing positions and attempt to get the ball into the box.

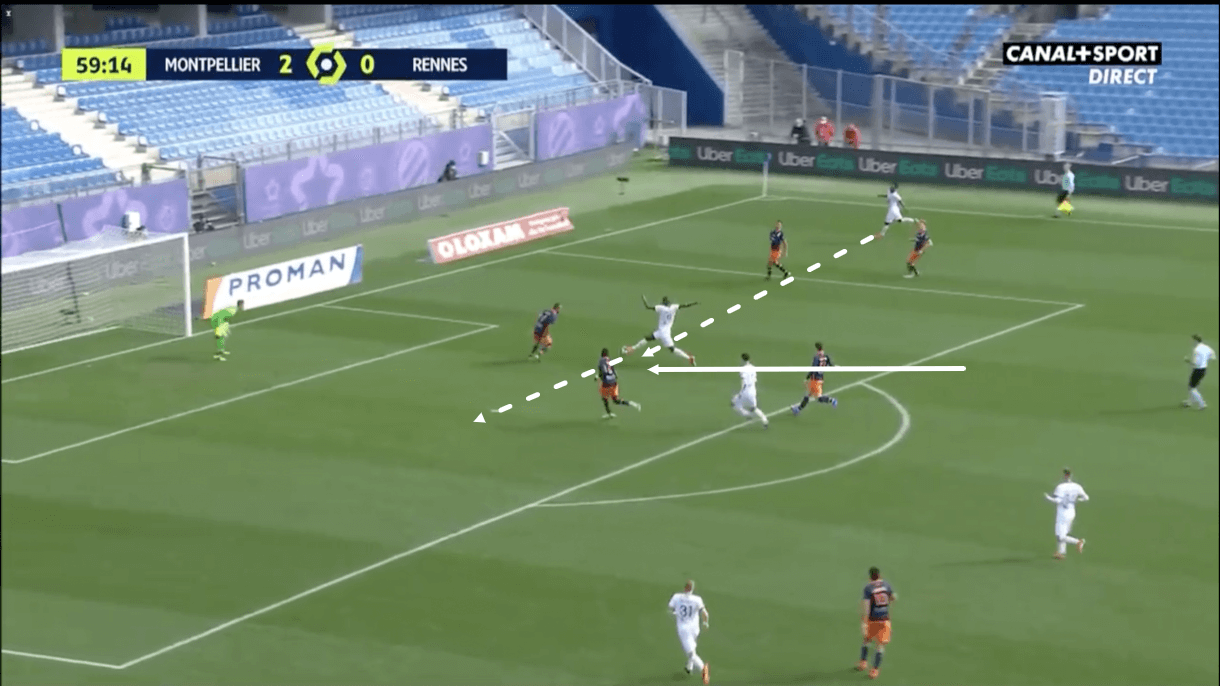

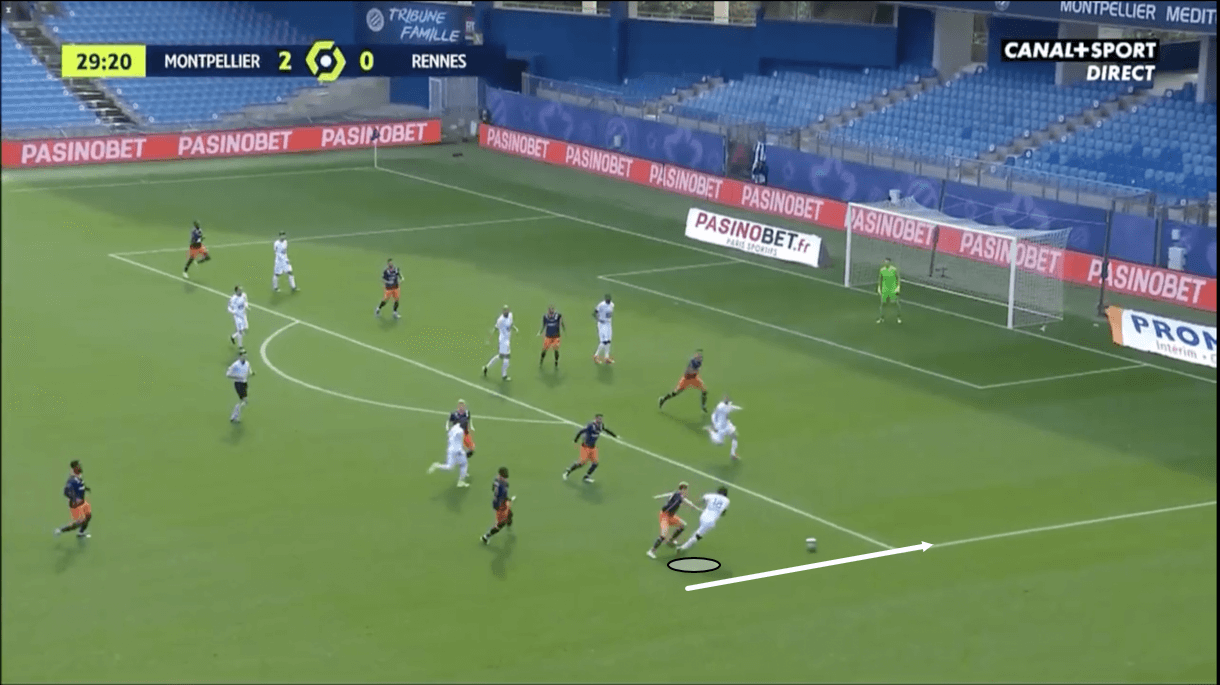

We can see one example of a Rennes cross not exactly going to plan in figure 4. Here, we can see right-winger Jérémy Doku playing the ball into the box and centre-forward Serhou Guirassy in the penalty box, attempting to get onto the end of his low cross.

However, Guirassy struggles to control the ball, which comes into the box at a significant pace. As a result, the opposition, Montpellier, manage to get out of danger by clearing the ball.

Low crosses like this, from the position in which Doku played this one and from even closer to the goal and inside the box, are a common feature of Rennes’ offensive tactics. They constantly look to progress the ball into the final third, get into positions like this or even further towards the byline, and play low crosses into the area at pace for one of the attackers to try and finish via a one/two-touch finish.

This sees Rennes progress the ball into the box fairly often, however, they don’t tend to take a lot of touches once the ball gets into the box. Their players tend to hit the ball first time once they get onto the end of these balls but these crosses rarely create free shooting opportunities in the centre of the box without obstacles in the way, so their first-time chances are often quite difficult, which may go some way to explaining why their average shot xG is so low.

Just before figure 5 was taken, this crosser was played through on goal from the edge of the box by his teammate. As he ran onto the end of the ball and finished up in this position, another teammate began making a run towards the back post, behind the opposition defenders where they couldn’t see him. This blindside run was effective, in that this player could arrive into the box late, unmarked, and get onto the end of the impending low cross, which he managed to finish.

Evidently, this is an example of one of Rennes’ successful low crosses and perhaps provides an example of one crucial element of how to succeed with these types of chances – off the ball movement. Initially, the eventual crosser demonstrated excellent off the ball movement by making the run that allowed his teammate to play him into this position and then the eventual goalscorer demonstrated excellent off the ball movement by timing his late run so well and sneaking in at the back post.

Intelligent movement is very important in these scenarios, however, oftentimes, Rennes’ attackers are already in the box and being marked tightly when the crosses are played, without any creative movement coming from deep, like this, to cause surprise and, ultimately, problems for the opposition. More movement in the box and more players making late runs into the box like this could help Rennes to be more dangerous from the crosses that they play so often, to boost their xG per shot and give themselves a better chance of scoring.

This type of movement has helped them to succeed in creating better chances than they normally do on several occasions this season, indicating that they could benefit from more of it.

Lastly, the vast majority of Rennes’ crosses come from the right-wing, where summer signing Doku generally plays. However, while Doku has been making a lot of Rennes’ crosses of late, along with the full-backs, who tend to make the bulk of Rennes’ crosses in general, a lot of his crossing has been ineffective.

Doku has got an average cross accuracy of 26.76% for the 2020/21 campaign, which is significantly lower than his team’s average cross accuracy percentage.

In figure 6, we can see Doku impressively carrying the ball past an opposition player and into the penalty area. This highlights Doku’s excellent dribbling quality. He has got a dribble success percentage of 59.32% for the 2020/21 season, which is better than Rennes’ average dribble success percentage of 53.8%.

However, as play moves on into figure 7, Doku’s cross at the end of this move leaves a lot to be desired and essentially puts his dribbling efforts to waste, as it misses everybody inside the box.

Doku has some room for improvement in the crossing department but his dribbling is very impressive. Given that Rennes cross so much and tend to generate relatively low-quality chances, perhaps Doku should be tasked with crossing less frequently and encouraged to continue carrying the ball on his own more often. Les Rouge et Noir have made fewer dribbles per 90 (25.88) than as many as 12 other Ligue 1 sides this season but they have the third-best dribble success percentage (53.8%) in France’s top-flight.

As a result, perhaps it would make sense for Rennes to try and create more via dribbling and considering that Doku’s dribbling is even more successful, on average, than the team’s impressive overall average level of success, he may be a good candidate to encourage to use this skill more.

Guirassy’s chances and Rennes’ use of through balls

In the previous section, we looked at an example of Guirassy failing to control one of Doku’s low crosses, resulting in a move breaking down. Unfortunately for Rennes, that’s not a totally uncommon sight since the centre-forward made his move from Amiens to Rennes last summer.

Guirassy has scored four goals in his 17 Ligue 1 appearances for Les Rouge et Noir this term. Last season, he bagged nine in 23 for Amiens, who were ultimately relegated from France’s top-flight.

The 24-year-old might have expected to increase his tally and receive better goalscoring opportunities this season, playing for a Champions League side, however, at present, Guirassy has scored 0.28 goals per 90 in the league this season, while last season he scored 0.4 goals per 90. Meanwhile, he had an xG of 0.39 last term and so far in the 2020/21 campaign, he has an xG of 0.34.

So, this indicates that Guirassy is not only scoring fewer goals than he did last season but he has had worse goalscoring opportunities than he had last season as well.

You could choose to view Guirassy’s less-than-stellar season as an indictment of his quality or as a case of Guirassy and his new team taking time to adapt to one another after simply failing to hit the ground running.

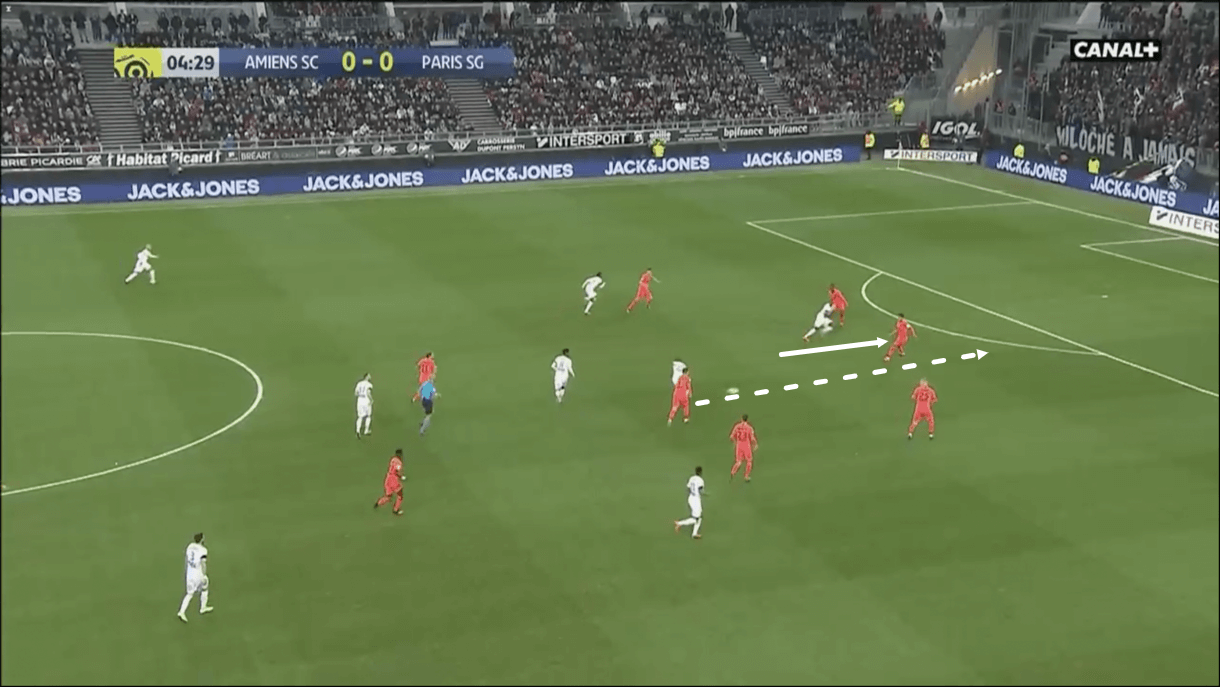

Figure 8 shows an example of one goal that Guirassy scored with Amiens last season versus 2019/20 Ligue 1 champions, PSG. To score this goal, Guirassy used what is arguably one of his greatest assets – his intelligent off the ball movement.

Guirassy is excellent at finding space and making runs. He’s constantly moving about up front to create space for himself and he’s generally reliable at making good, threatening runs. He’s especially effective at this when his team is attempting to play through balls and he can sit on the shoulder of the opposition defence and just peel away behind into space.

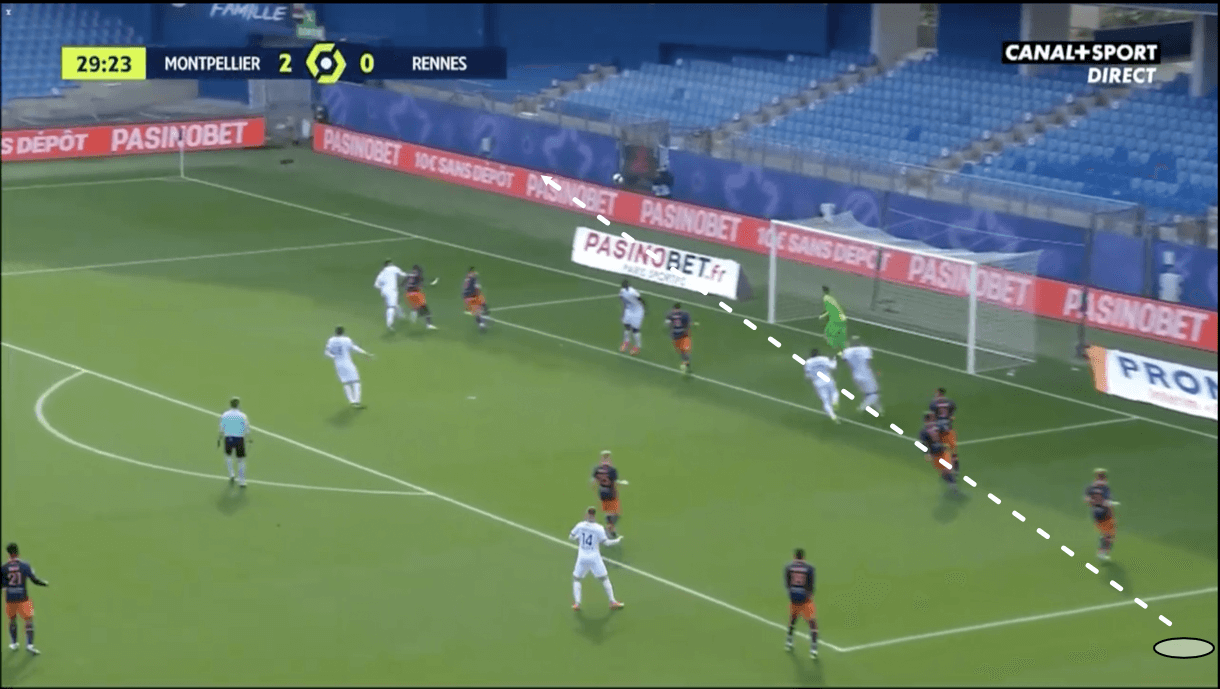

We saw Guirassy make a similar movement to score for Rennes recently versus Montpellier in a 2-1 loss. Figure 9 shows us how Clément Grenier was found, in between the lines, and played a through ball for Guirassy to pounce on as he moved between the defenders in behind the backline and into the penalty box.

It’s clear from these examples that Guirassy is effective at finding space between defenders, peeling away in behind the defensive line and getting onto the end of through balls before demonstrating composure by finishing the 1v1 with the ‘keeper, which requires different skills to what he’s typically been using at Rennes, when trying to get onto the end of low crosses, which requires him to react quickly and finish first time or high crosses which requires him to use his heading ability.

Only five Ligue 1 teams have played fewer through balls than Rennes (6.72) this season. However, they’ve got the third-best through ball success percentage (35.2%) in France’s top-flight. Rennes don’t attempt many through balls like the one Grenier played to set up Guirassy versus Montpellier, but they’ve been relatively successful with the ones they have played this term and they’ve got a striker who loves getting onto the end of them, so perhaps Rennes could get more out of Guirassy and ultimately improve their goalscoring record by trying to create more chances like this one via through balls.

Weakness at defending counterattacks and the targeting of Rennes’ holding midfielders

Broadly speaking, Rennes’ defence has not been their biggest concern this season. They’ve conceded 31 goals in 27 games so far this campaign, giving them the fifth-best defensive record in the league in terms of goals conceded, and they’ve faced the fourth-lowest number of shots per 90 (8.88) of any Ligue 1 side, indicating that they’ve been good at limiting their opponents’ goalscoring opportunities.

However, they’ve not handled defending counterattacks particularly well of late. In fact, plenty of their opponents this season have made a concerted effort to create counterattacking opportunities against Rennes and they’ve often succeeded via these tactics, exploiting Rennes’ weakness in this area.

One way in which teams have exploited Rennes on the counter is by defending deep, clearing the ball to a man on the edge of the area and taking advantage of the lack of pressure that has often been applied to this player as the transition occurs, allowing them to either carry the ball upfield or enjoy time to pick out a teammate via a pass.

Meanwhile, plenty of teams have also exploited Rennes’ tendency to play through the holding midfielders quite strictly during the build-up via intelligent pressing specifically targeting these players, resulting in a turnover and a dangerous counterattack. We’ll look at examples of both of those scenarios in this section of analysis.

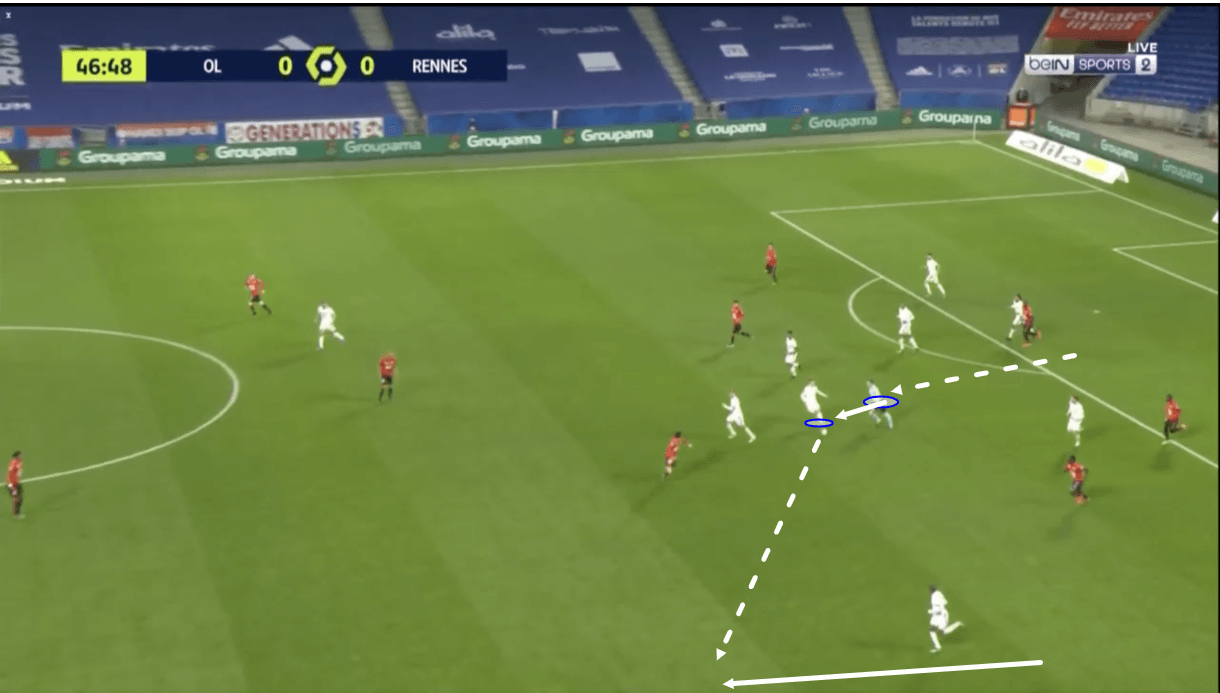

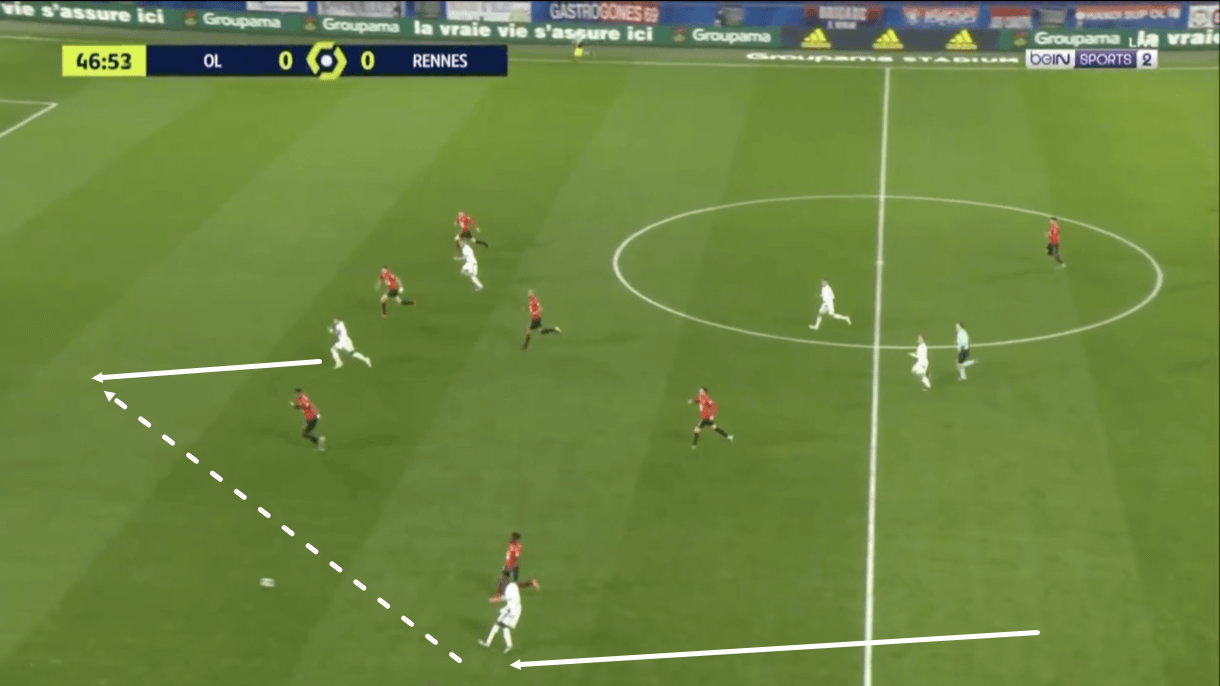

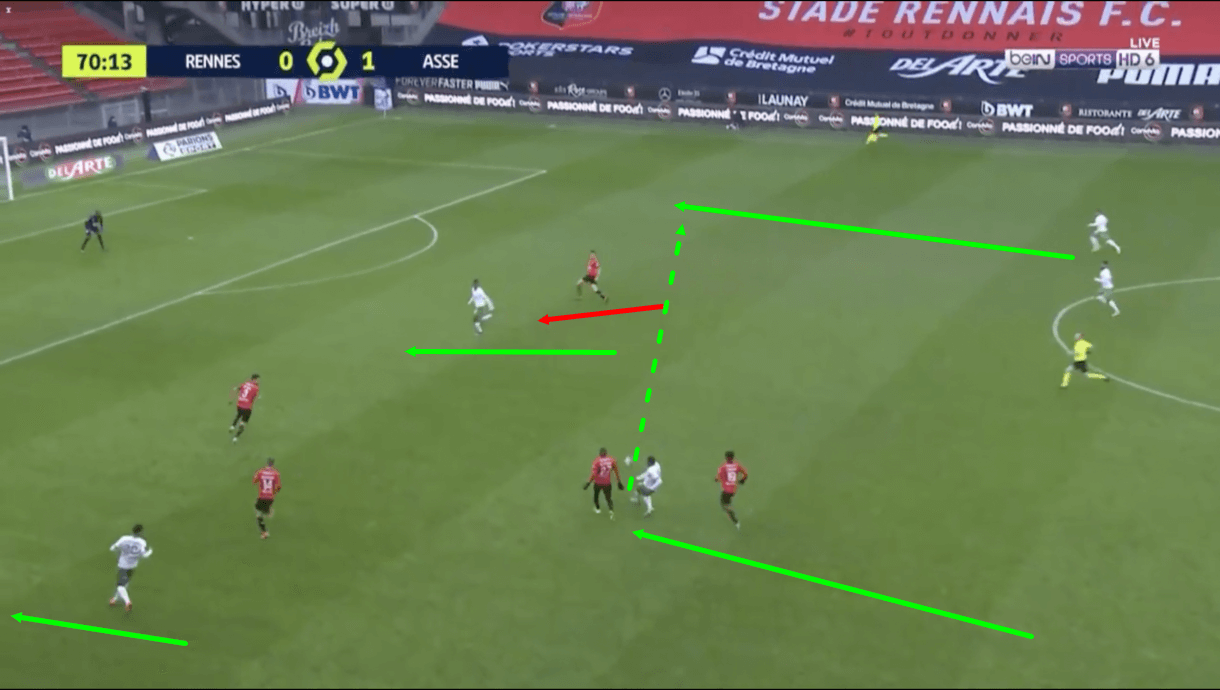

Firstly, figure 10 shows us an example of the first scenario we discussed above. Just before this image, Rennes were attacking the box of their opponents, Lyon. They had plenty of their team committed forward before Lyon managed to clear the ball out of the penalty area and to a free man on the edge of the box.

As this player received possession, he was able to turn, carry the ball a few steps forward and remain unchallenged while he casually picked out a pass to the winger beginning a threatening run down the left flank. We can see one Rennes player attempting to cut off this passing lane, which he ultimately fails to do, but the passer is in a lot of space and while Rennes had many men committed to the final third during their attack, we can see that five of them remain ahead of the ball and aren’t very urgent in their attempts to get back behind the ball as this Lyon counterattack begins.

This is a somewhat common sight for Rennes when it comes to defending against counterattacks. Their players often aren’t as urgent as the opposition’s in moments of transition and as a result, they can be punished on the counter as the opponent quickly transitions.

In figure 11, we see that as play moves on, the Lyon winger managed to carry the ball upfield and into Rennes’ half before finding Memphis Depay via a through ball. The Dutch attacker goes on to enjoy a close-range shooting opportunity when he gets onto the end of this ball.

This passage of play highlights just how easy it can be for teams to cut through Rennes once they do start their counter and perhaps it’s no major surprise that teams have been targeting them in this area. They must react quicker in moments of transition like this, either decreasing the time it takes for them to limit the space that attackers enjoy in the middle and final third on the counter or applying more pressure to the passer who initially begun the counterattack. By doing so, perhaps they could decrease the number of high-quality chances they concede on the counter.

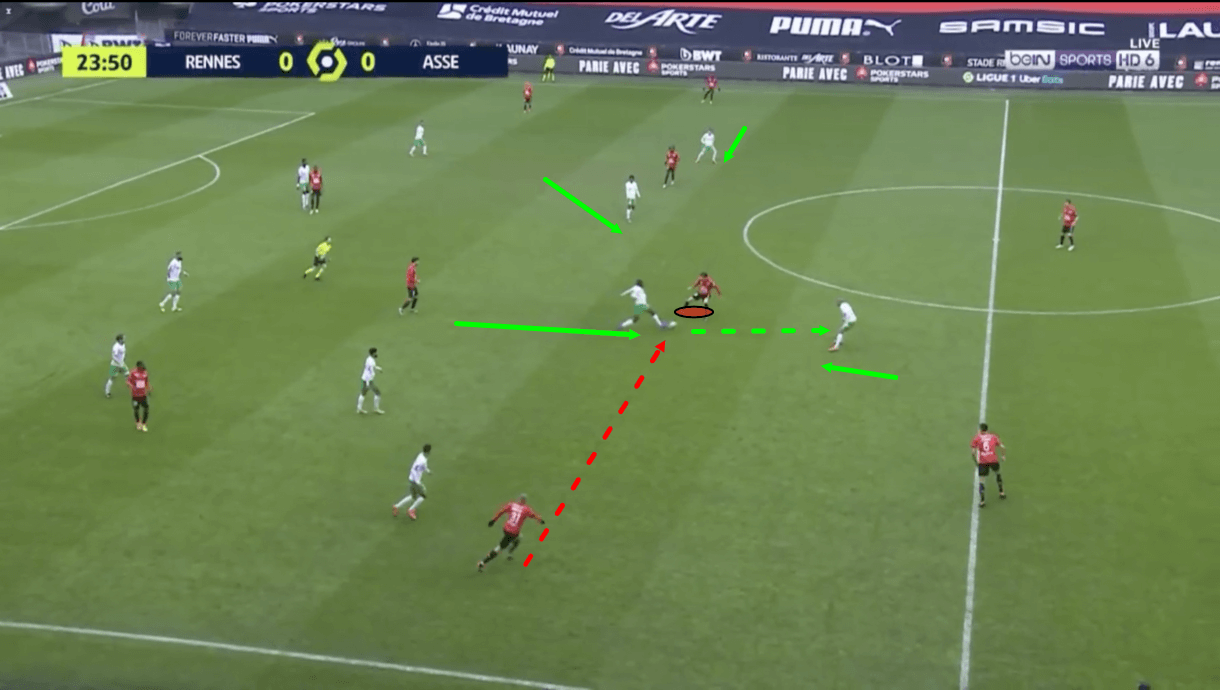

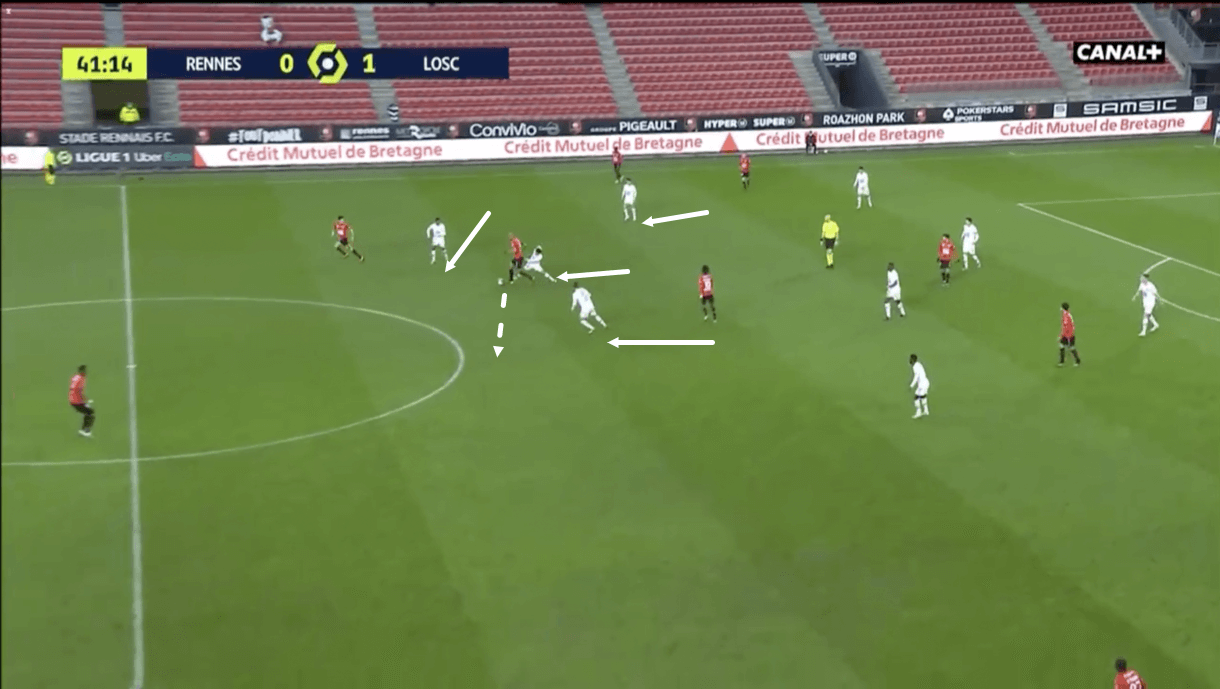

Next, we’ll provide analysis of how teams have effectively been targeting Rennes’ holding midfielders via pressing to create more dangerous chances on the counter. We see an example of one such case in figure 12, where Jonas Martin was playing the holding midfield role in Rennes’ 4-3-3 in their recent 2-0 loss at home to Saint-Étienne.

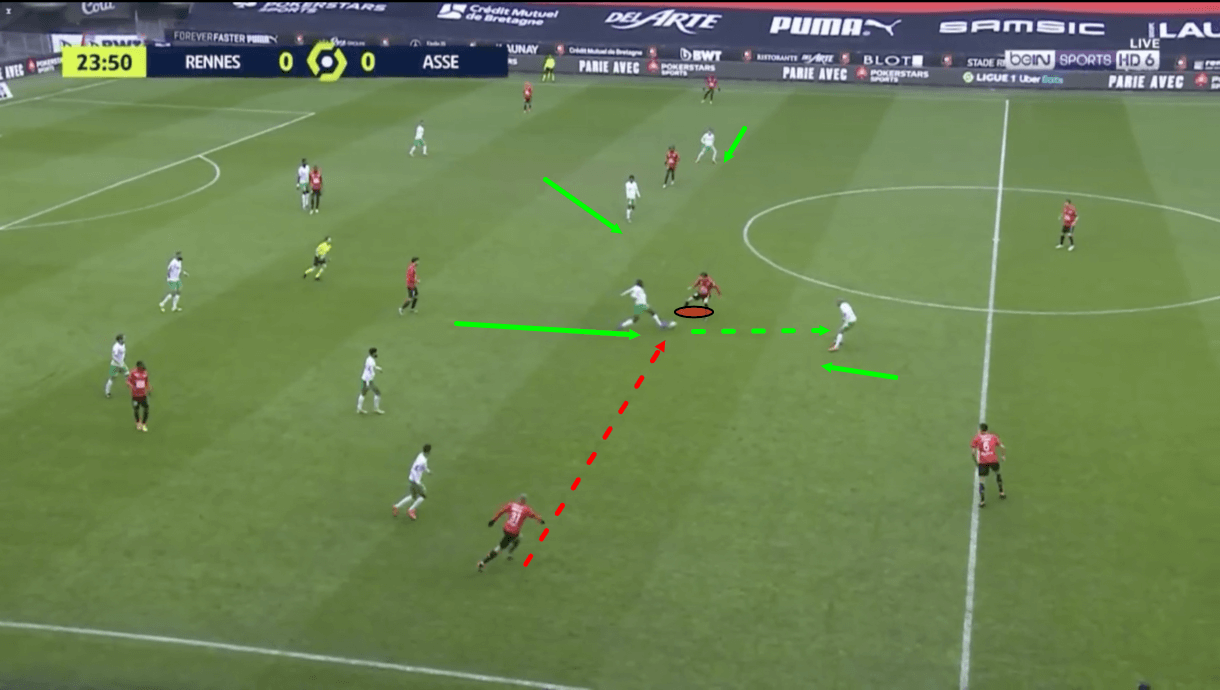

Firstly, it’s important to note that a lot of Rennes’ build-up play typically moves through the holding midfielder(s). This was quite a strict element of their game throughout Stéphan’s tenure at the club, leading to the holding midfielder, usually Steven Nzonzi, generally making the vast majority of passes for Rennes every game. This player performs an important role in switching play, providing a passing outlet to players under pressure in more advanced areas of the pitch and being the link between the defence and attack, via his central position from where he generally enjoys a broad passing range.

However, Rennes’ reliance on this player can be predictable and they failed to cope with that predictability being exploited by several of their opponents throughout the 2020/21 campaign.

In figure 3, left-back Adrien Truffert attempted to play the ball into Martin as he came under some pressure out wide, however, Saint-Étienne were waiting for that pass to be played and as it was, one midfielder sprung into action, quickly closing down Martin and actually managing to intercept the pass, setting his side off on a counter. We can see that other Saint-Étienne players also closed in around Martin as this pass was played, in case the interceptor was unable to immediately win the ball back so that they could limit Martin’s passing options and help apply pressure to him.

However, Saint-Étienne were able to win the ball back quickly and as play moves on, they managed to create a dangerous chance and test Rennes’ goalkeeper, Alfred Gomis, via a shot at the end of the move.

Saint-Étienne were particularly good at executing their gameplan of applying immediate pressure to Rennes’ deep midfielders as they received passes in this recent fixture, with figure 13 showing an example of substitute Yann Gboho suffering the same fate as Martin did in the previous passage of play. He was pressed by several Saint-Étienne players and dispossessed before he could settle on the ball.

As play moves on, we see how dangerous it can be for Rennes when they lose possession in these areas, because of how weak it leaves their backline and we already explained that, at times, their players in more advanced positions aren’t urgent enough in tracking back which can lead to the backline getting overloaded, as was the case in figure 14, as the man who won back possession plays the ball across to a free man running into space on the opposite wing. This passage of play highlights exactly why Saint-Étienne and many other like-minded teams have targeted Rennes in this way.

Figure 15 shows an example of current Ligue 1 leaders Lille successfully deploying this same strategy in their recent 1-0 win over Les Rouge et Noir. Several Lille players hounded around Nzonzi as he received the ball in midfield, limiting his immediate passing options and ultimately forcing a turnover that directly led to Lille creating a goalscoring opportunity.

We can see that this predictable element of Rennes’ game caused them issues towards the end of Stéphan’s tenure but this doesn’t necessarily mean that Génésio should take a completely different approach.

Rennes’ midfielders must be able to act quickly to avoid getting caught in possession and perhaps dropping another midfielder deep and positioning them relatively close to the other one during the build-up would make life easier for them and prevent the holding midfielder from becoming isolated. Moving a full-back into a narrow position, essentially becoming a second holding midfielder in this stage of play, could also be an option that would perform this role, potentially creating a central superiority for Rennes in this area and allowing them to build through the centre even if the holding midfielder is marked tightly.

Greater use of central rotations, combined with quick passing, could also help Rennes to stop getting caught in possession in this area, find free men in the centre and continue building through this area, as this would provide support to the holding midfielder and make it more difficult for the opposition to press as effectively as they would if the movement is more static in this area.

Conclusion

To conclude this tactical analysis piece, it’s clear that Génésio’s immediate main focus must be on getting Rennes’ attack firing once again. They’re struggling to create high-quality chances and they’ve got a centre-forward who is capable of better than he’s shown at Roazhon Park thus far.

As far as the other end of the pitch is concerned, while Rennes have been one of Ligue 1’s best at the back this season, improving their ability to defend against counterattacks would take them up another level again.

While they’ve not had a particularly great 2020/21 campaign, there’s still lots of quality in this Rennes side and if Génésio can harness it and get Les Rouge et Noir moving in the right direction, a positive end to the season is not out of the question and could inspire positivity at the Brittany-based club heading into the 2021/22 season.

Comments