Following a lengthy career as a player, Rhian Wilkinson, which resulted in her amassing 181 caps for her national side of Canada, then turned to coaching and worked with Canada’s youth teams before spending time as the assistant coach for national sides Canada, England and Great Britain.

Then, in 2022, she got her first gig as a first-team head coach with the Portland Thorns. However, despite winning the 2022 NWSL Championship, she left the club having ‘lost the dressing room.’

After a one-year hiatus in February 2024, Rhian Wilkinson was appointed as the new Wales head coach following Gemma Grainger’s appointment to the Norway national team.

Since then, Wilkinson has been in charge of two games against Kosovo and Croatia. In those two games, they scored ten goals and conceded none. Although this is a small sample size, we believe there are lots of positives to take away from these performances.

In this tactical analysis, we will provide an analysis of the tactics both in possession and out that have developed the Wales side in their recent matches.

In Possession

The first aspect we are going to examine is Wales’ possession. First of all, we need to set the scene by comparing Wales’ output over the past four years. In 2021-2023, Grainger managed Wales, and in 2024, Wilkinson managed it.

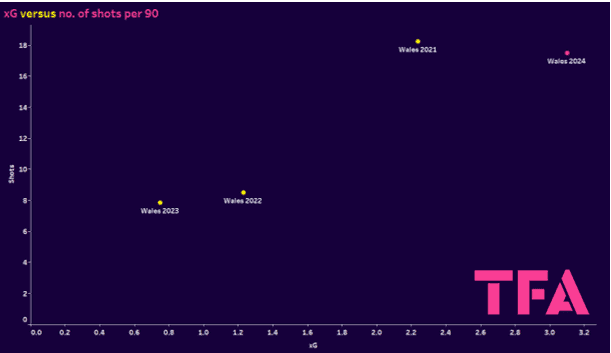

This first graph looks at a comparison between the average xG per 90 and the number of shots per 90. What instantly stands out is that the years 2021 and 2024 have a much higher attacking output than the years 2022 and 2023; we will look at this aspect in more detail in a moment.

However, you may also notice that in 2024, Wilkinson’s Wales has created the highest xG of 3.10 over any of the past four seasons and has done so with fewer shots than Wales in 2021, suggesting that the quality of shots being created is of a higher value.

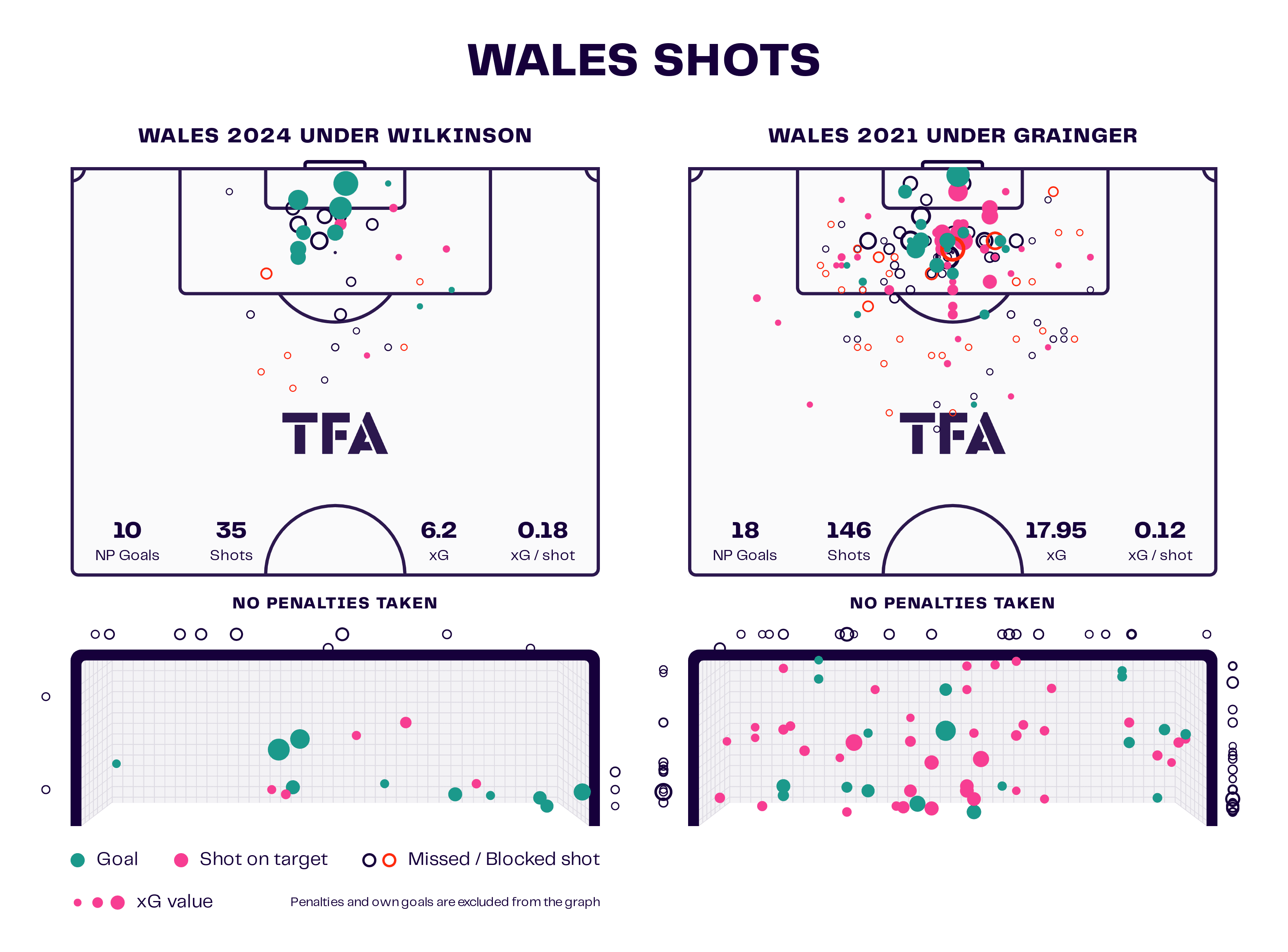

Here, you can see the difference between shot locations between the 2024 and 2021 sides. Although not a major difference, the 2021 data is taken from a larger sample size of eight games compared to the two from Wilkinson in 2024.

All this is considered to be the difference in 2021, with the xG per shot being 0.06 higher on average in comparison to 2021. This is a potential indicator of higher-quality box entries, creating higher-quality opportunities.

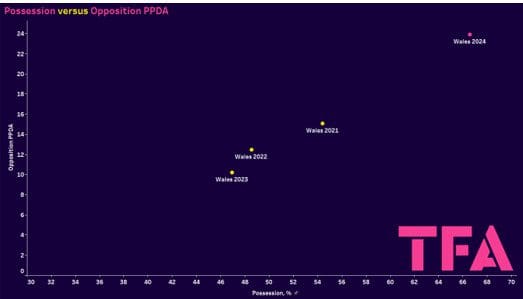

This graph here compares the average possession per 90 against the opposition’s PPDA. A high PPDA indicates a team with a less intense press. We wanted to use this as a potential indicator of the difference in the quality of opposition faced so far by Wales under Wilkinson. However, this is not the only answer; it is also potentially being affected by an increased quality of play in possession by Wales, the true likelihood being a bit of both.

However, Wales averaged 66.59% possession in 2024 compared to 54.42%, 48.56%, and 46.96% between 2021 and 2023, respectively. This suggests an improved quality and purpose in possession, which we will look at in more depth now.

One of the most obvious differences between Wilkinson’s approach to Grainger’s is their preferred formations. Wilkinson deployed some iteration of a 3-4-3 shape, while Grainger favoured a 4-2-3-1 or a 4-4-2 shape during her tenure.

This change in shape makes two key differences to Wales in possession. The first of which is the flexibility it offers Wales to switch between a 3-2-5 and 3-3-4 attacking shape. With this ability, Jessica Fishlock has to find space and play as a midfielder while also being effective in the final third as an attacker, which is particularly crucial.

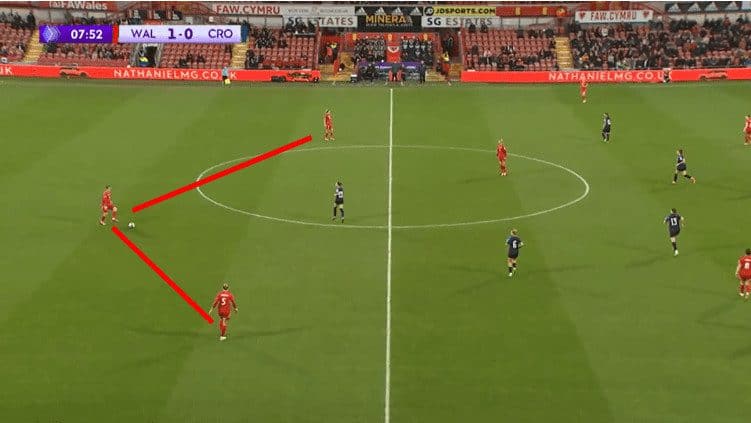

Here, you can see the 3-2-5 shape deployed by Wales. What this does is create real width over the field.

If we roll this clip forward, Wales are able to use this width to find a one-on-one match-up between Fishlock and the Kosovo defender where the ball falls to the on-rushing Rachel Rowe from midfield, who can finish off the opportunity for the opening goal of the game.

In this example, you can see the 3-3-4 shape that Wales looks to create in attack, with Rowe dropping as the left midfielder. This creates this diamond appearance for Wales as Sophie Ingle has the ball. Ingle is then able to play the ball into Fishlock, playing between the lines, who can turn and play through teammate Kayleigh Green, who is able to finish off for a goal.

The other advantage to this change in formation is the natural passing angles it creates for Wales players to play through the lines. With balls played into attackers receiving the ball between the lines in the half spaces being considerably more common than previously where the wingers were encouraged to play wider.

Here, you can see the natural passing angles that are being created. With the wing-back Lily Woodham hugging the touchline, she is able to receive the ball with an open body shape and play the ball around the defender towards Fishlock, playing between the lines, who can turn and play from there.

Contrast this Wales building from the back with the 4-2-3-1 shape. The wingers generally played with width, and as a result, Wales would be playing balls down the line that could be more readily blocked, prevented, and tracked by full-backs. This limits their ability to orient themselves to play quick, efficient balls, such as the wing-back in the previous example.

Out of possession

Having looked at the noted development in possession play by Wales, let’s now take a look at how they operate without the ball.

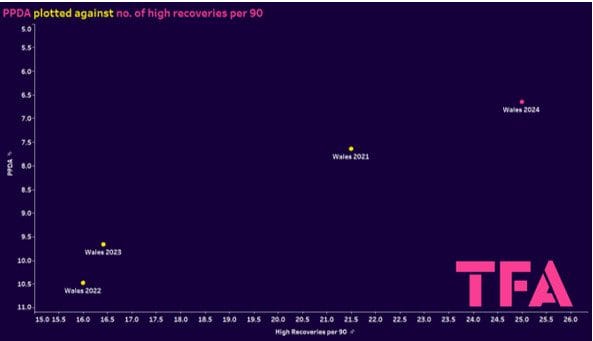

This graph here is to indicate Wales’ ability to be more aggressive in the press, with the suggestion being that a low PPDA suggests a more intense press, and then you combine that with a high number of high recoveries inside opposition territory to suggest a higher engagement line.

This graph shows that the 2024 iteration of Wales has the lowest PPDA of all four years, at 6.65, and it also has the highest number of high-ball recoveries, with an average of 25.00 per 90.

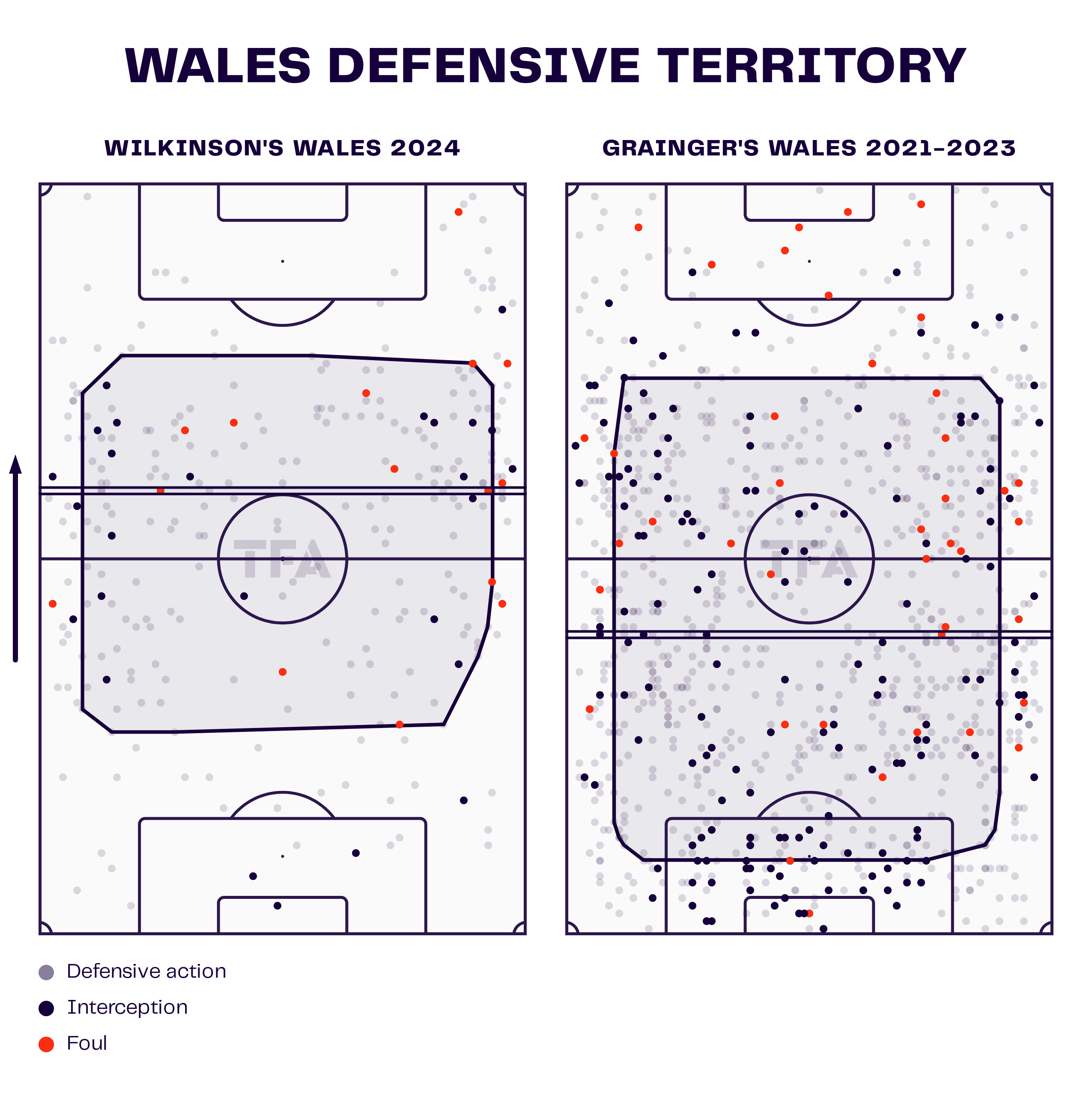

This defensive territory map compares the Grainger era to the start of the Wilkinson era. The first thing to draw your attention to is the average defensive line position, which is considerably higher and even in the opposition half during the Wilkinson era. The ball recoveries are more spread out across the field, and the average defensive line position is also much deeper. This supports the suggestion that Wilkinson has started to implement a higher press.

The first characteristic of this Wales side in possession is the aggression they have demonstrated to be aggressive in the press and prevent the opponents from playing out from the back. With them casting a net inviting their opponents to play into their pivots before condensing this space in an attempt to win the ball back high up the field and counter the opposition.

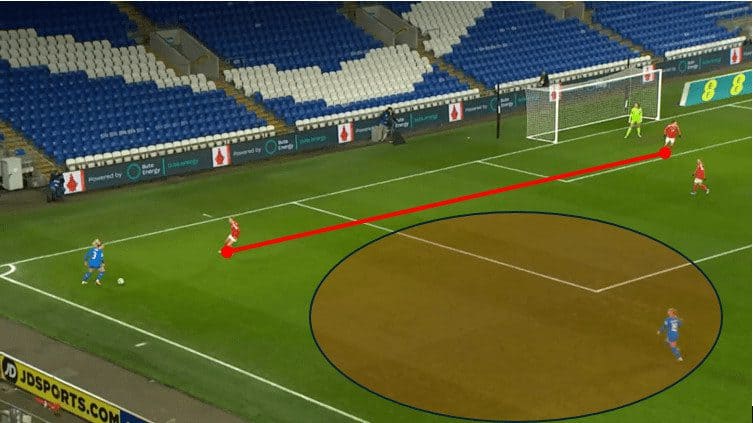

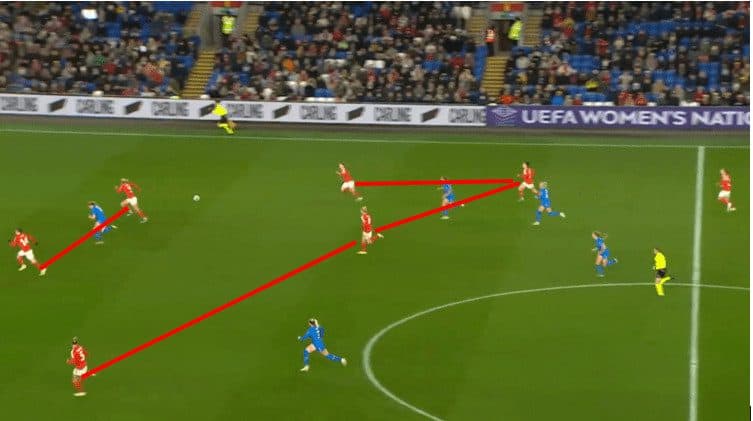

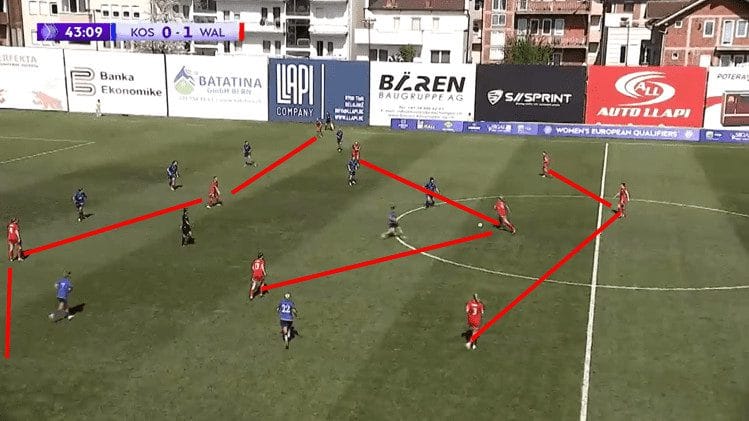

Here, you can clearly see the pressing net created by the Wales players, with Wales trying to bait Kosovo into playing centrally in their pressing trap.

However, Kosovo isn’t tempted and instead tries to play around with the shape. When this happens, Wales is able to condense the flanks, creating a five-versus-four defensive superiority in the wide channel. Then, all that’s left to do is make their numbers count.

The next aspect to look at is how switching to a 3-4-3 shape has created a bigger connection and solidity in central areas defensively. Wales can now condense the middle with a 5-3-1-1 defensive shape compared to what would often be a 4-2-2-2 defensive shape under Grainger, with the wingers often remaining too high to be effective.

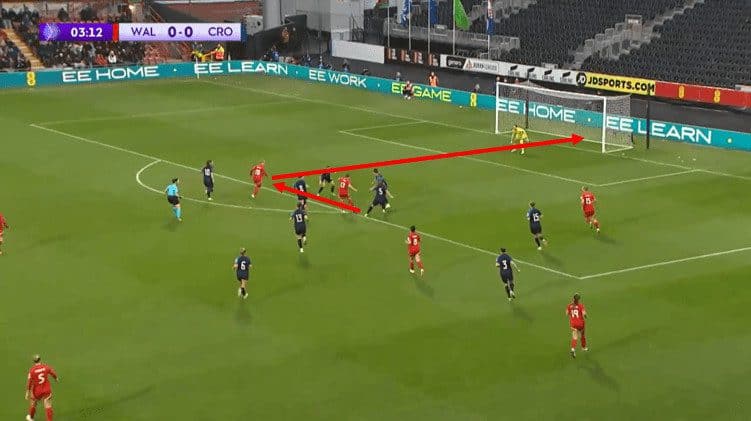

What you can see is the compactness that Wales are able to create with this 5-3 defensive shape. You can also see how condensed the midfield is with three Wales players staying and connected to each other.

Then contrast this to Wales under Grainger with their 4-2 defensive shape; note the disconnect that has been created. Also, note the space down the flanks as the Wales midfielders are forced to work across the field. Wales are then able to utilise this space and play a cross towards the back post, which causes disruption and eventually results in a goal for Iceland.

All this contributes to a more effective deep defensive shape which has limited its opponents to only 2.5 shots per game and only conceding an xG of 0.10 combined across the two games.

Transition

As previously noted, one of the key developments in the Wales side has been their ability to win the ball high up the field. They have also demonstrated an improved ability to be clinical in these areas once the ball has been won back.

The noticeable difference in approaches has been Wales’s intention to play quick, sharp balls into feet during defence-attack transitions. In contrast, previously, they would play longer, more aerial balls looking to cover a greater distance with each pass.

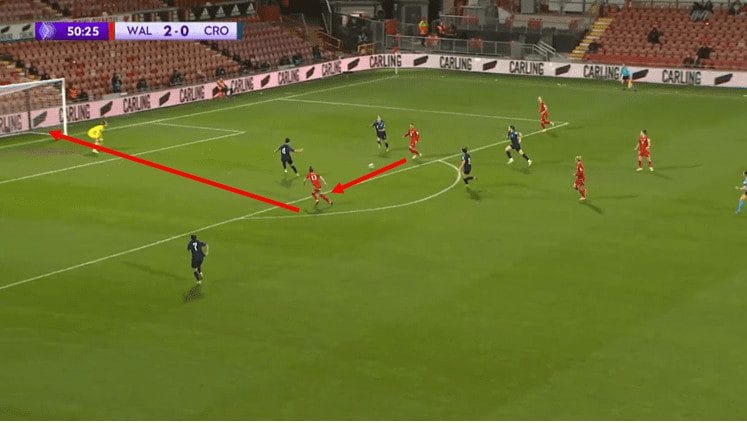

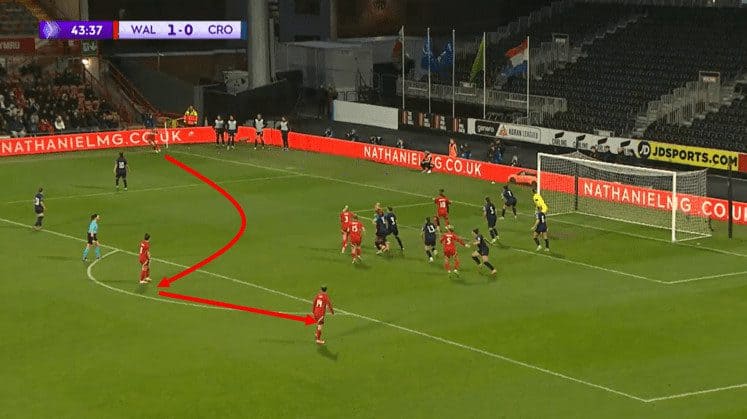

In this example, Wales wins the ball in Croatia’s half of the field, and Angharad James is then able to play the ball into Rowe’s feet. Rowe then turns and drives at the defence before drawing in four opponents towards her and playing Fishlock in one-on-one with the goalkeeper, which she duly finishes off.

Here, you can see Wales setting the midfield trap in the pressing game. Croatia plays the ball into that area, where James can step in and take the ball from her opponent, who is playing the ball into Fishlock’s feet. Fishlock then plays the ball to Rowe, who duly finishes off.

The other area that Wales has changed their approach is in their rest defence, previously utilising a 2-4 rest defensive shape; however, they are now utilising a 3-3 defensive shape, which often looks more like a 3-1 defensive shape with the wing-backs pushing forwards in attack.

This switches the point of attack for opponents, with Wales now better equipped to cover space across the backline. However, it does also open up the space in the midfield, often leaving Sophie Ingle isolated centrally.

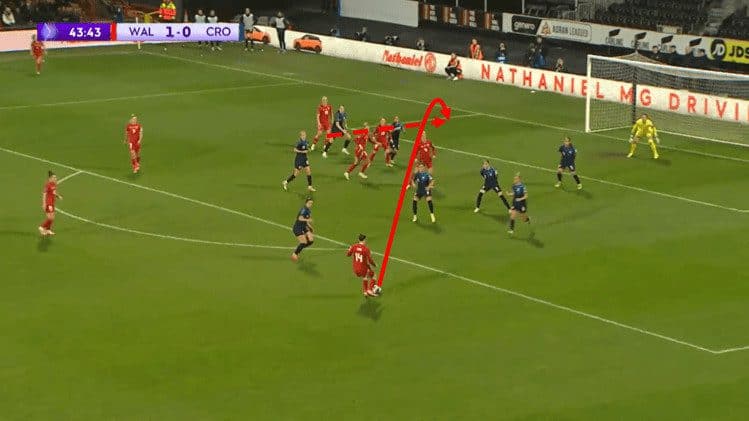

Here, you can see the 3-1 rest defence shape. Note how, should the ball be lost in the midfield, four Croatian players would occupy the space, which Ingle would have to deal with.

Here, you can see the 2-4 shape of the Wales side in attack-defence transition. What you will notice is that the space has now switched more so towards the space behind the full-backs in the wide channel.

Set Pieces

Another aspect that Wales has looked different under Wilkinson is from the different types of looks that they can produce at set piece time.

In this example, Rowe takes the corner with her right foot. The interesting variation is James’s movement. She initially stands wide, almost as if offering herself as a short option. She then feigns to go back before driving to the front post, where Rowe is able to find her, and James gets a shot on goal.

In this example, you have two players at the edge of the box. Rowe pulls the ball back to James at the edge of the box, who squares the ball to Hayley Ladd. Ladd plays the ball over the top of the defence to Elise Hughes on the back post, who is able to get a header away, which unfortunately goes over the bar.

These are just a couple of examples of how Wales can be creative at set piece time to change the point of attack.

Conclusion

In this scout report, we have outlined the key tactical changes that Wilkinson has made to develop this Wales side. We have demonstrated throughout how Wilkinson has been able to cultivate a positive and flexible football team who are aggressive in both phases of the game.

Now although this has come under a relatively small sample size against relatively weak sides, there will undoubtedly be tougher tests ahead however, there certainly are positive early signs for the future of the Wales national team under Rhian Wilkinson.

Comments