Brighton have moved quickly to appoint a replacement for the departed Graham Potter — who became Chelsea’s new Head Coach on a five-year deal on September 9th — by hiring the promising young Italian manager, Roberto De Zerbi. De Zerbi has made quite a name for himself in his native Italy, with provocative football that has been applauded for its bravery and criticised for its perceived riskiness, both of which we’ll look at in this analysis.

De Zerbi’s first success came from winning the Copa Italia Lega Pro with Foggia in 2016 before being appointed manager of recent Serie A additions, Benevento, after a brief stint at Palermo. Despite being unable to save Benevento from relegation, he remained in Serie A when hired by Sassuolo, where he took a team that had finished in the bottom half of the table five times in the previous six seasons to back-to-back top-10 finishes. Finishing eighth in his last two seasons, Sassuolo narrowly missed out on Europa qualification by two goals to seventh-placed Roma at the end of the 2020/21 season — his final year with the club.

He departed his homeland to manage Ukrainian side Shakhtar Donetsk, taking over in May 2021, taking them to Super Cup success a few months later against arch-rivals Dynamo Kyiv in a Klasychne derby final. He managed the team for 18 games of the Ukrainian Premier League before the season was cancelled due to the conflict with Russia.

In this tactical analysis, we will take a look at De Zerbi’s approach, how it works, how it can be undone, and what to expect at Brighton.

Provoking the press

De Zerbi has drawn his fair share of plaudits for his attacking football, which relies heavily on his defenders patiently sharing possession and provoking a press from opposition forwards. He gets his players to stretch the opposition vertically as his own attacking line presses high up against the opposition defence, leaving space to be exploited in the midfield. When an opportunity occurs, a quick burst of tempo sees the ball played directly to the midfielders, who pick out the forwards with a penetrating pass or send the ball wide to overlapping midfielders who work the ball into the box.

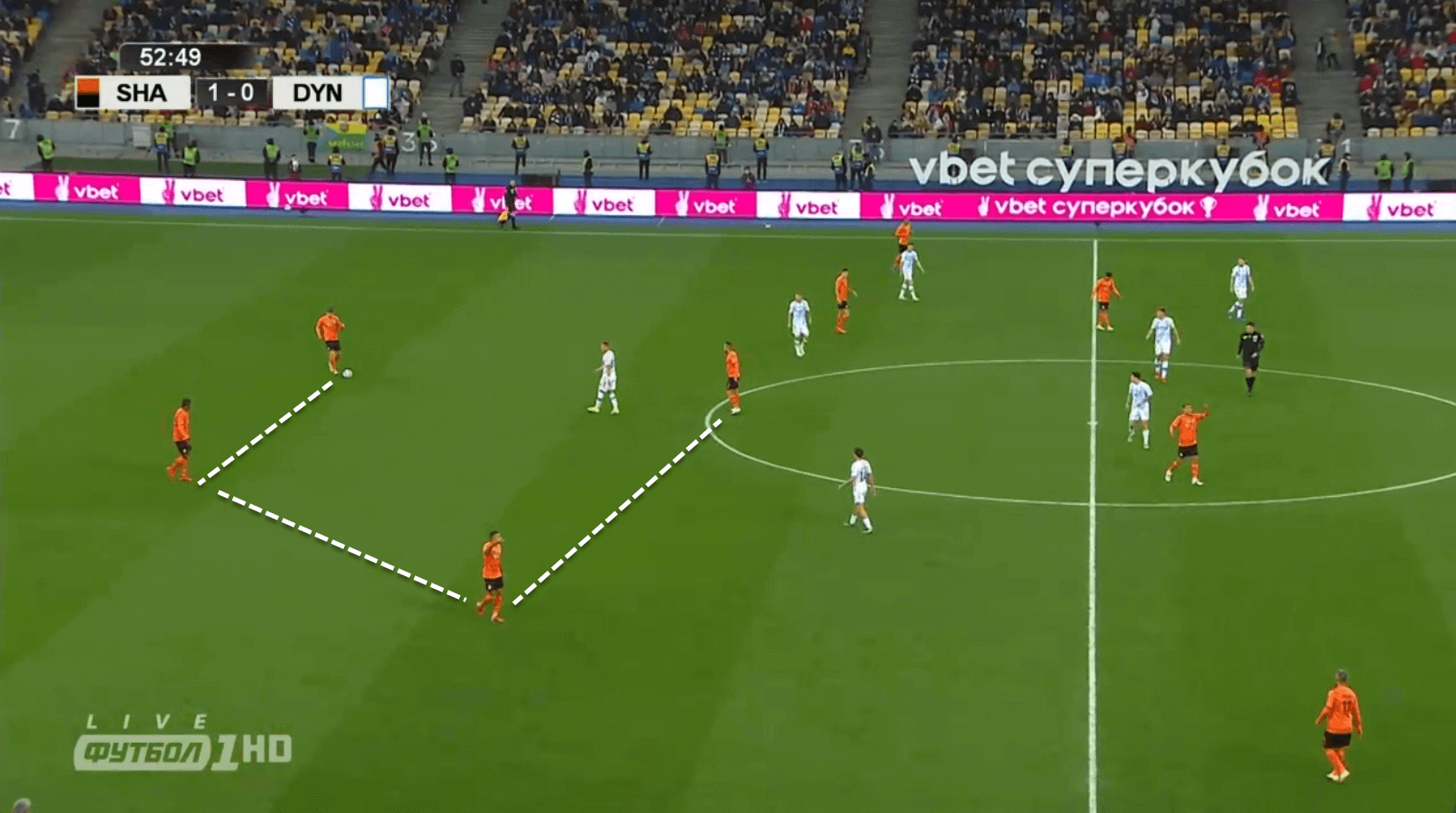

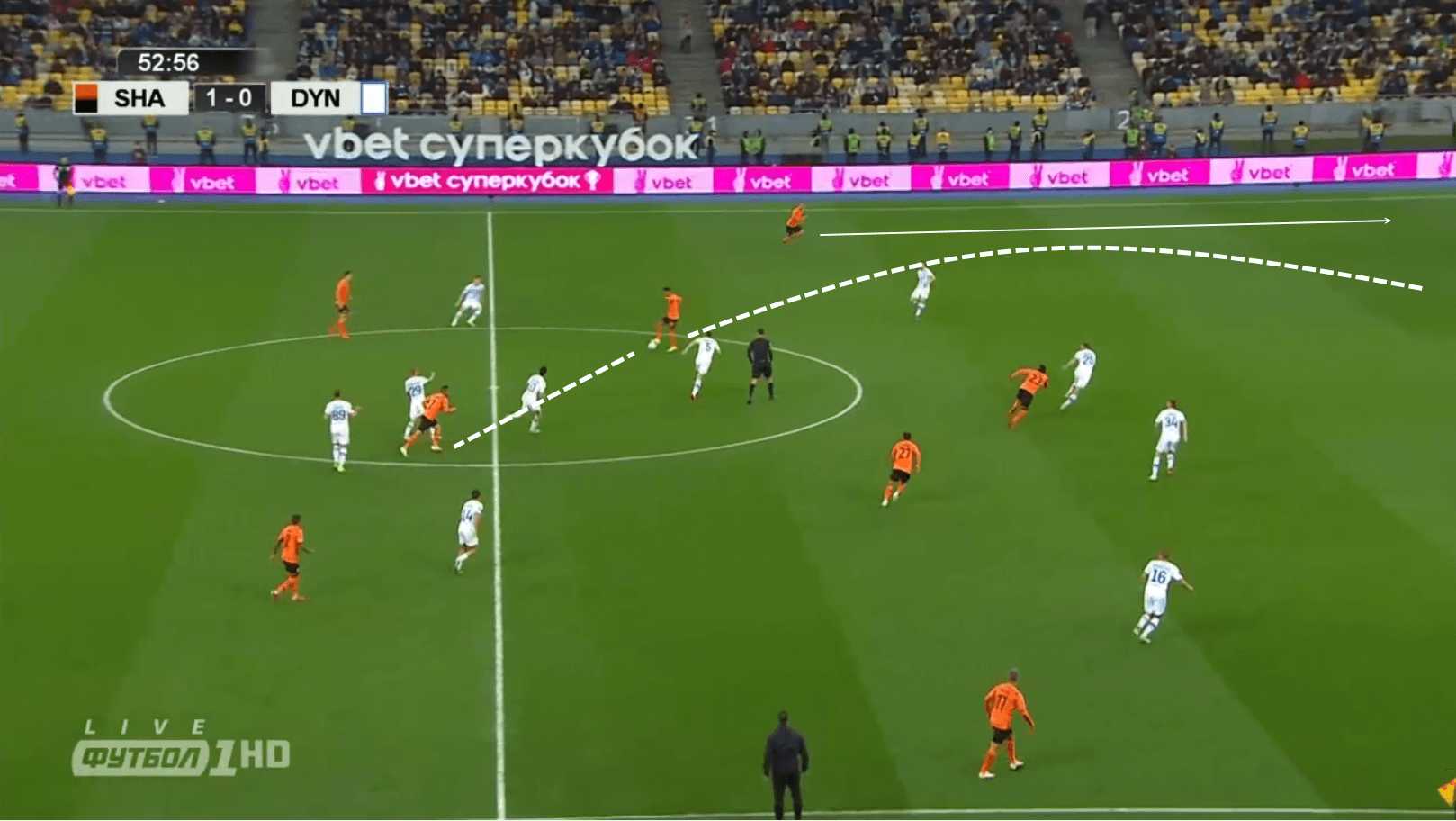

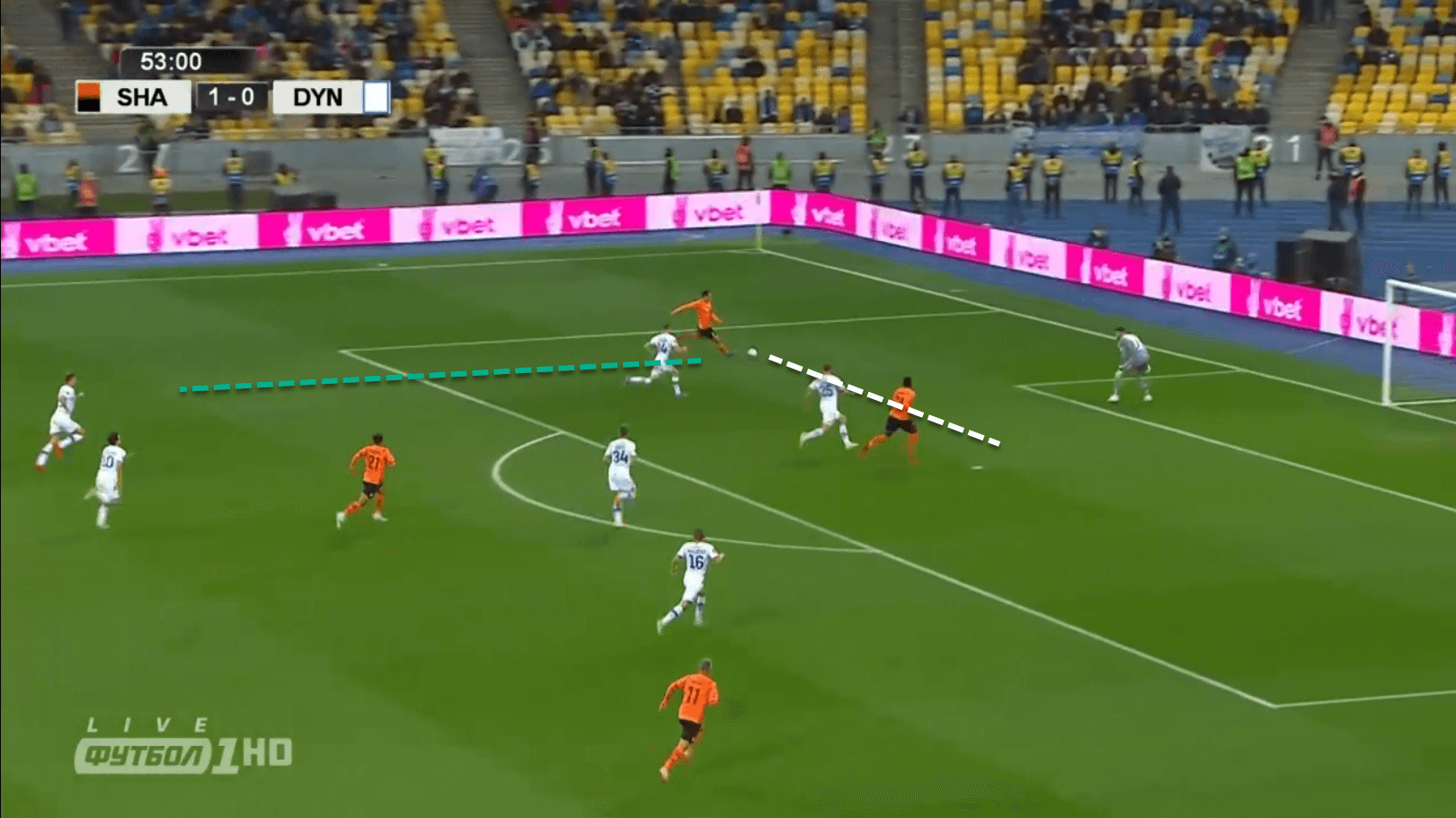

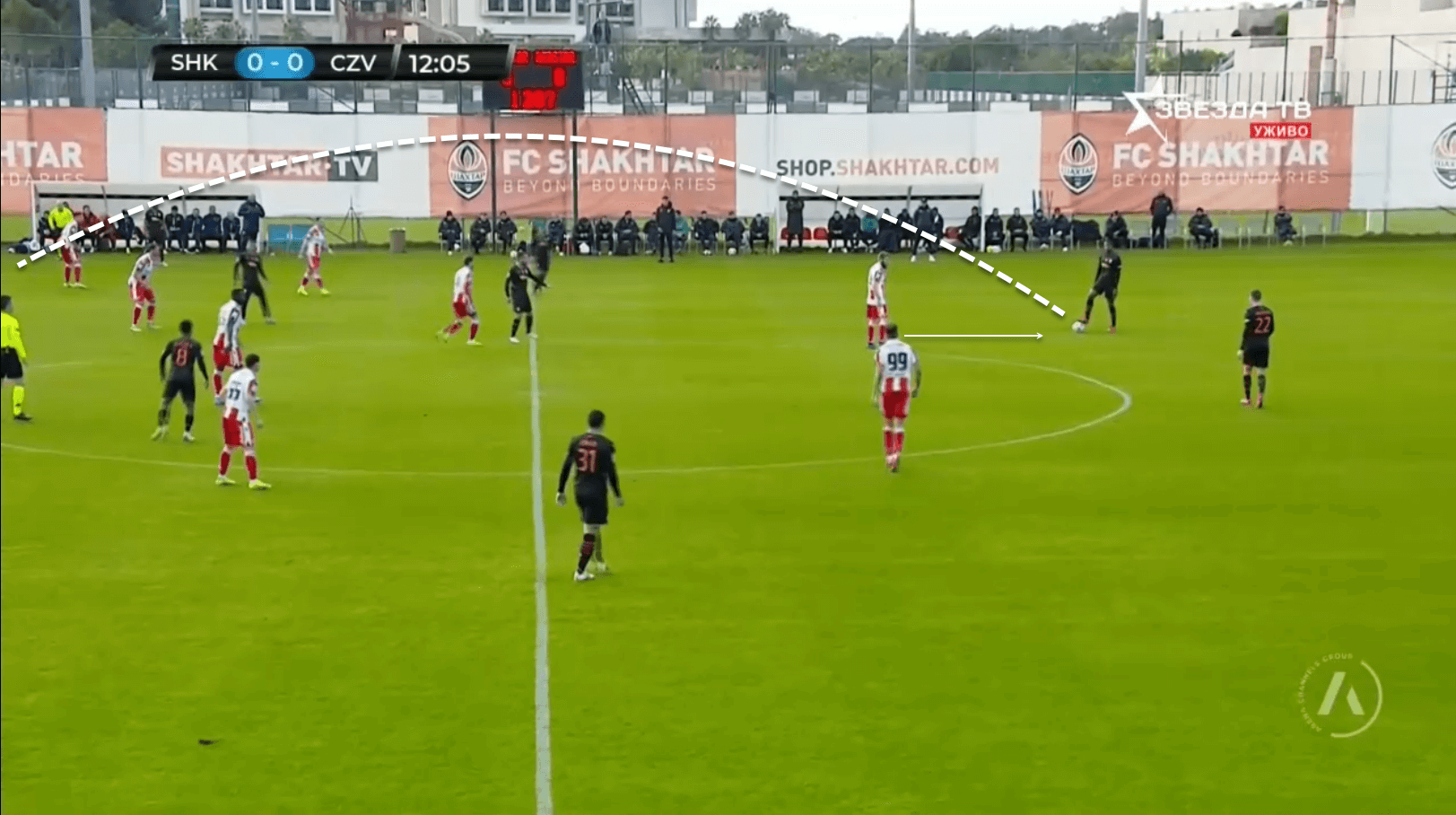

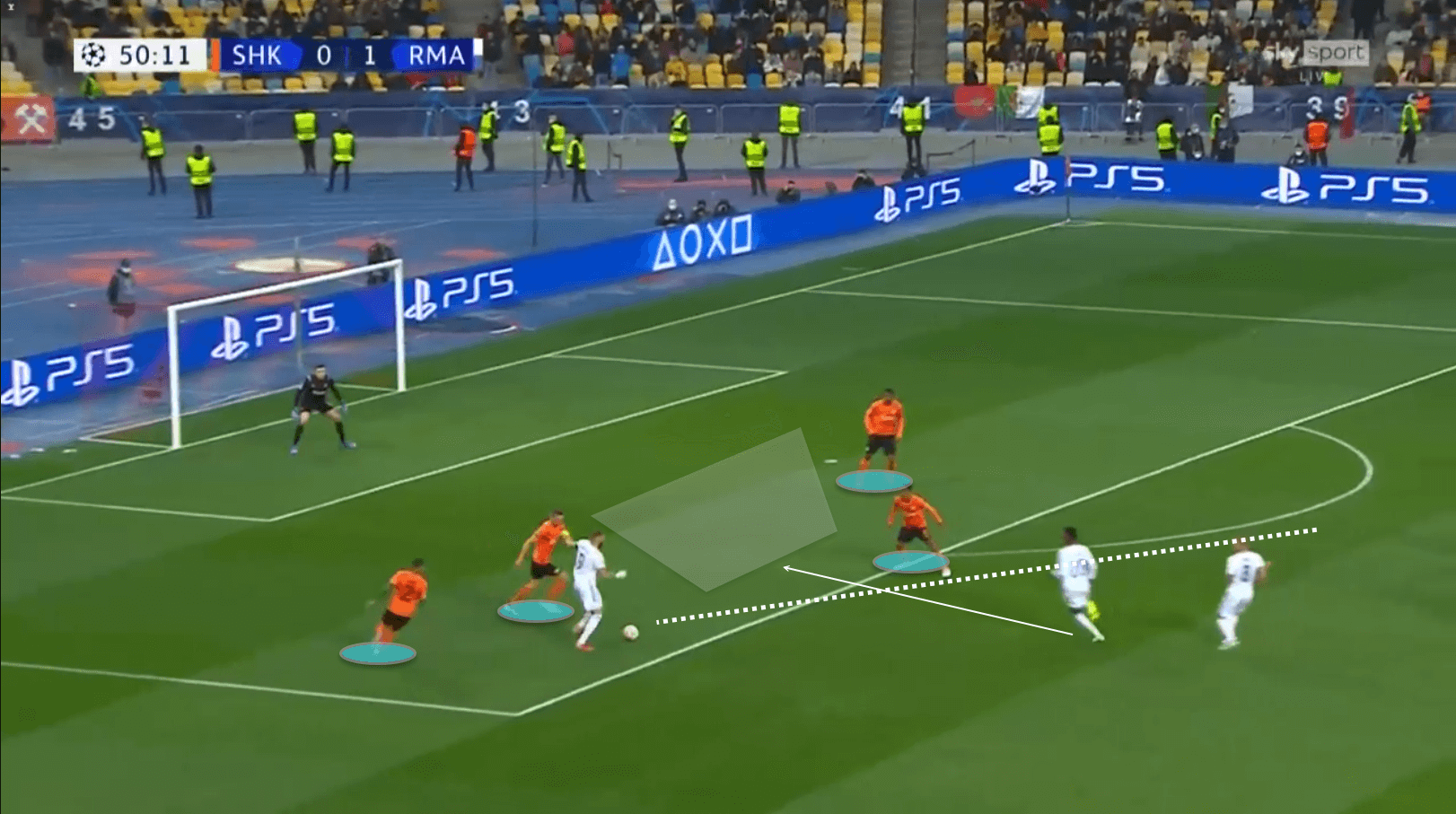

Rather than attempting to avoid the press by playing away from it, De Zerbi likes his teams to provoke a press so that the ball can be played over or around the opposition players in a quick build-up often mistaken for a counterattack. In the images below, you can see how Shakhtar initially use short passes between the defence before laying the ball off to one of the central midfielders, who launches a diagonal ball into space to be crossed in and converted by the attacker.

The images below demonstrate how closely the players in the low block stay to each other in order to pass the ball around the opposition once they initiate a press, beating the opposition with superior numbers. The first image shows Shakhtar’s Marlon holding onto the ball long enough to provoke a press from Benzema, who he immediately circumvents.

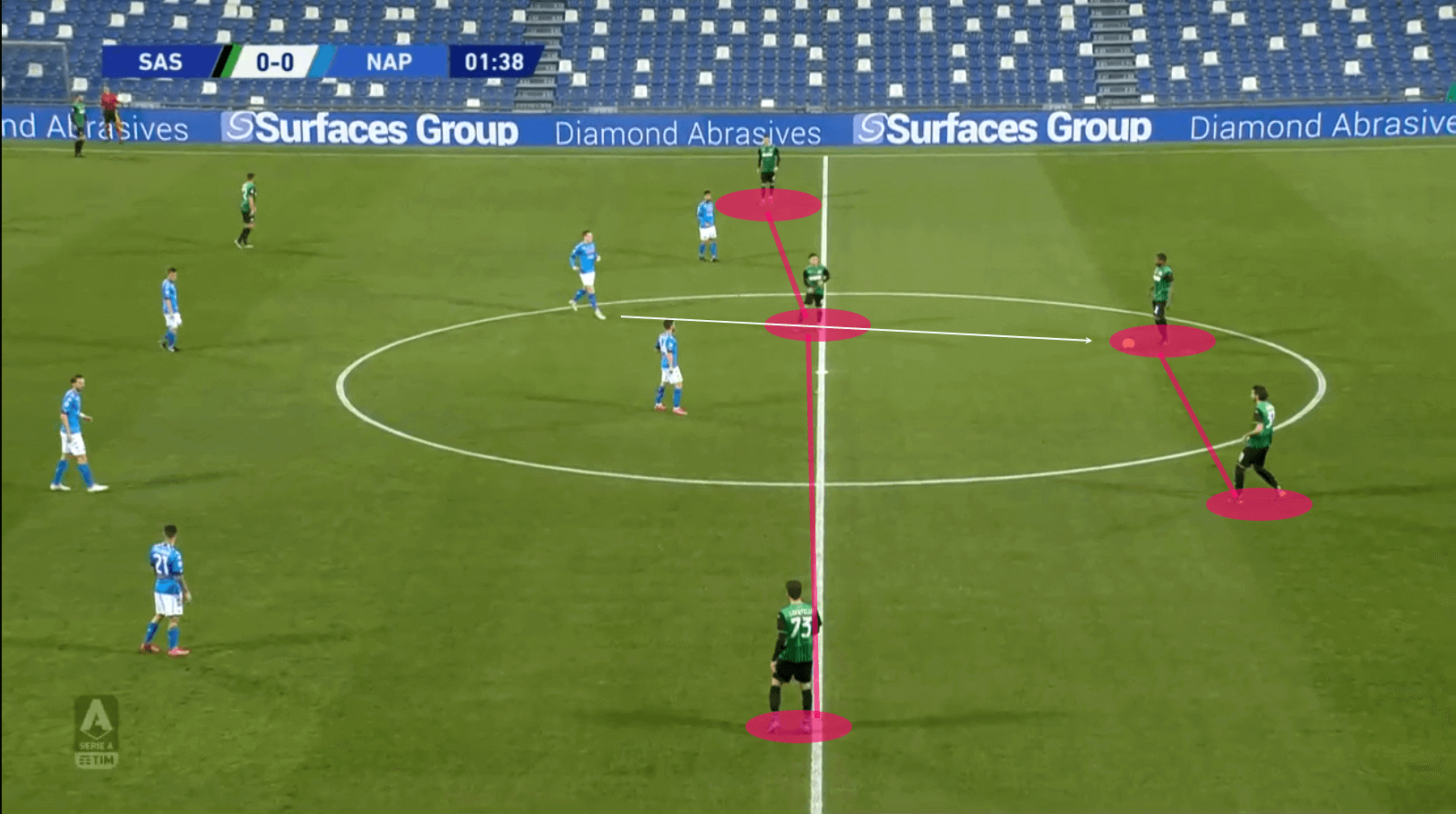

Below, Marlon, this time whilst playing for De Zerbi at Sassuolo, holds onto the ball long enough to provoke a reaction from the Napoli forward Piotr Zieliński, again, playing around him to exploit the gap he leaves in his pressing.

The below image is taken from a clip that shows Marlon holding onto the ball for a full 8 seconds in a friendly against Crvena Zvezda, controlling it with the sole of his foot and provoking a press from Aleksander Katai, before launching the ball into space for David Neres to attack, leading to a goal just seconds later.

De Zerbi is clearly an advocate of moving the opposition by keeping the ball stationary rather than moving the ball around a stationary opposition and has been quoted as saying that passing the ball is ‘gambling’.

This system-based approach relies on defenders recycling possession between themselves and the goalkeeper, often against the ‘keeper’s own goal line, inviting oncoming forwards to press the ball in order to play around them. This method was labelled ‘risky’ by some Italian journalists, as it involves having a very low block and encourages the opposition to press very near to the goal. But De Zerbi’s logic is that the closer the press is to his own goalkeeper, the less area of the pitch there is to defend.

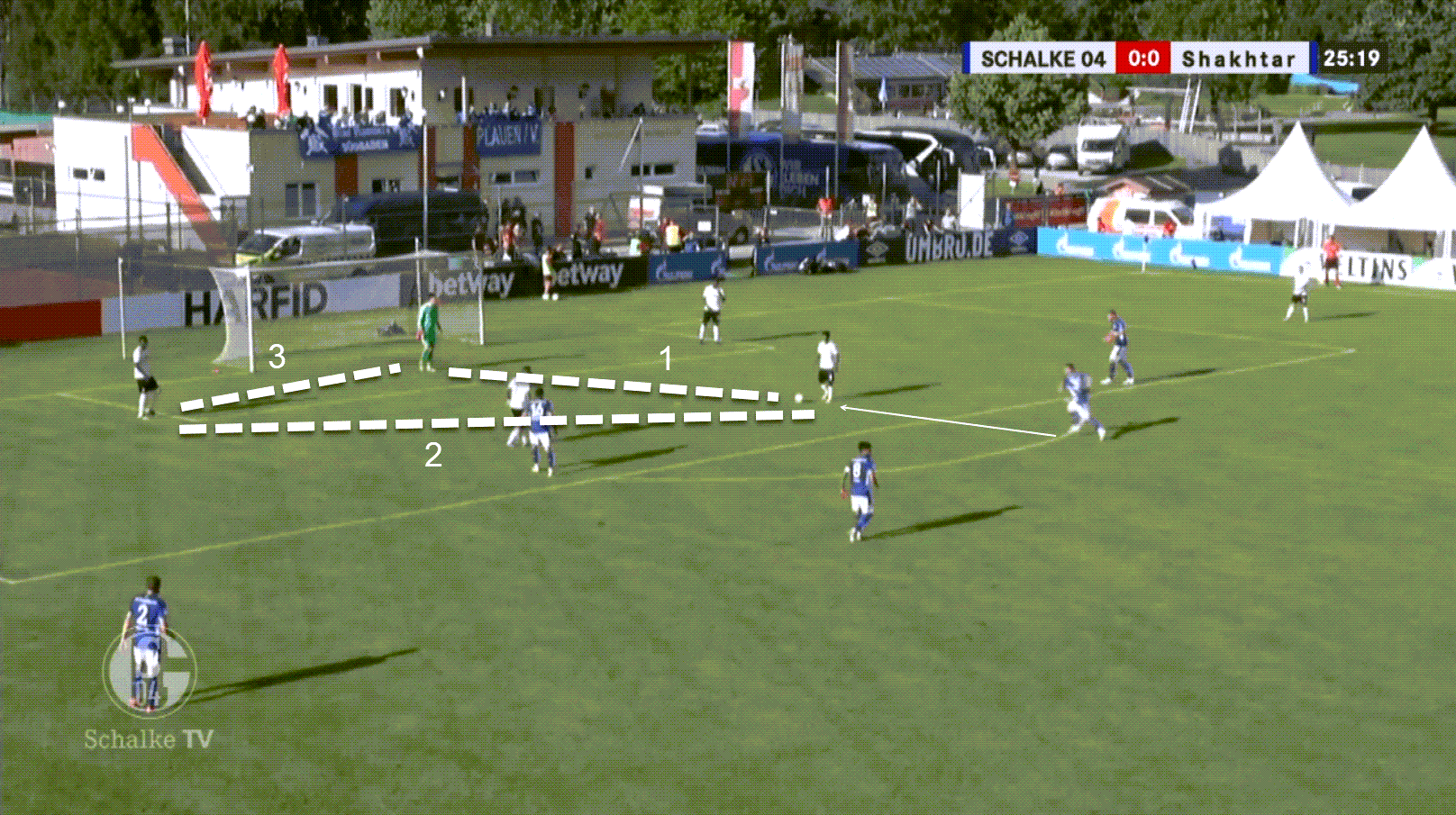

Below, we can see an example of this in a friendly against Schalke 04. The low block starts at the goal line. As Shakhtar goalkeeper, Trubin, passes to Marcos Antonio (1) to initiate a press from Idrizi. Antonio then passes to Marlon (2), who passes back to Trubin (3), which initiates a press from two Schalke players before he passes into space over the head of Antonio (4) for him to carry the ball into the opposition’s half.

On the attack

Despite attacking from wide and stretching the opposition defenders across their penalty area, Sassuolo didn’t rely on crosses into the box for goals, instead patiently passing the ball and probing the area waiting for the opportunity to make a through pass to someone better positioned. Wingers would stay wide, but only to stretch the opposition defence whilst the midfield joined the attack, usually ending up in a 2-3-5 shape. No other team in Italy had as many shots from inside the box as Sassuolo at the end of his first season, nor had made as many short passes.

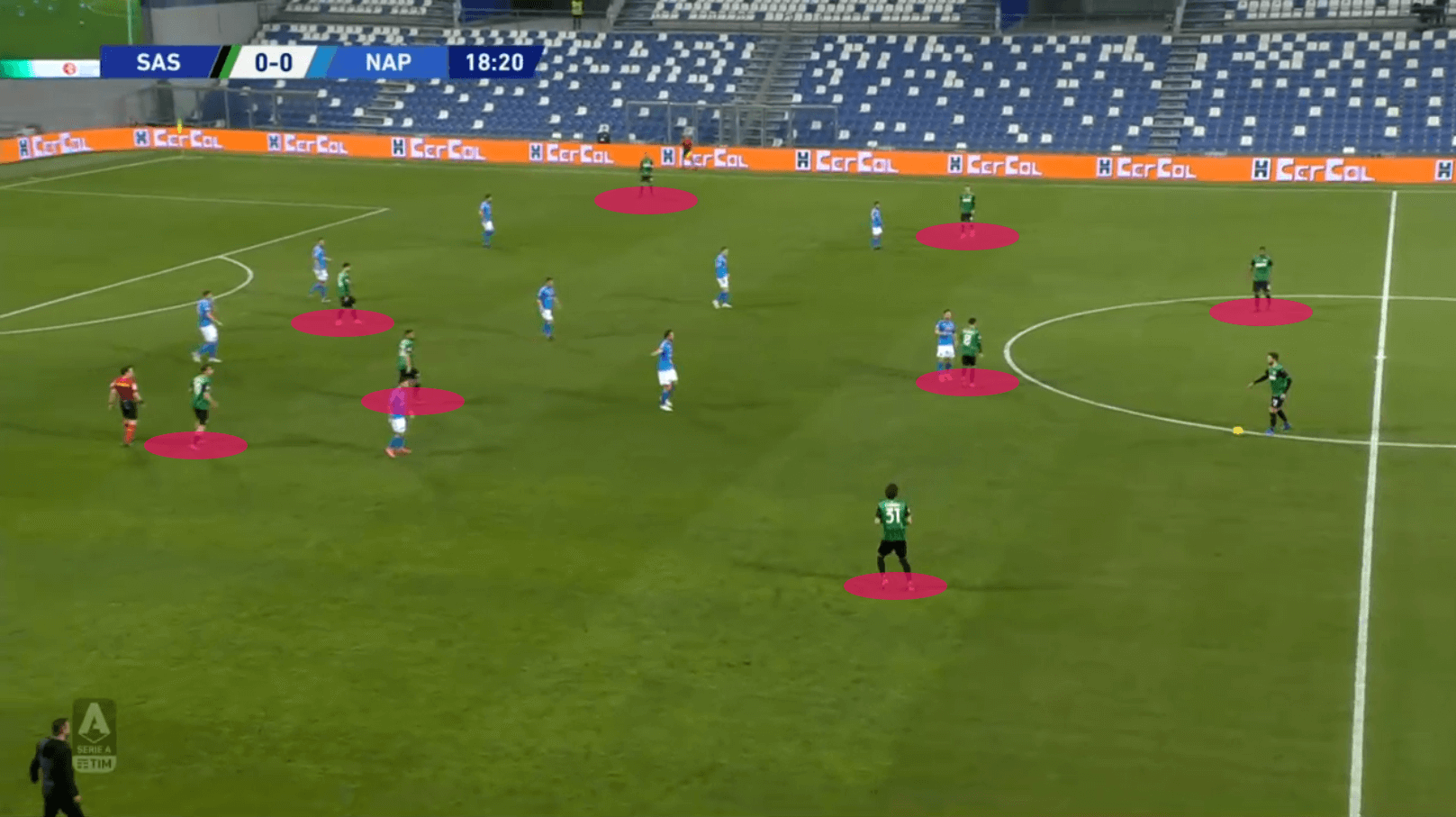

Below is an example of De Zerbi’s Sassuolo back line retaining possession in the opposition half and patiently waiting for opportunities to exploit space that opened once Napoli pressed; in this image, we can clearly see 8 players ahead of the ball that Gian Marco Ferrari can choose from.

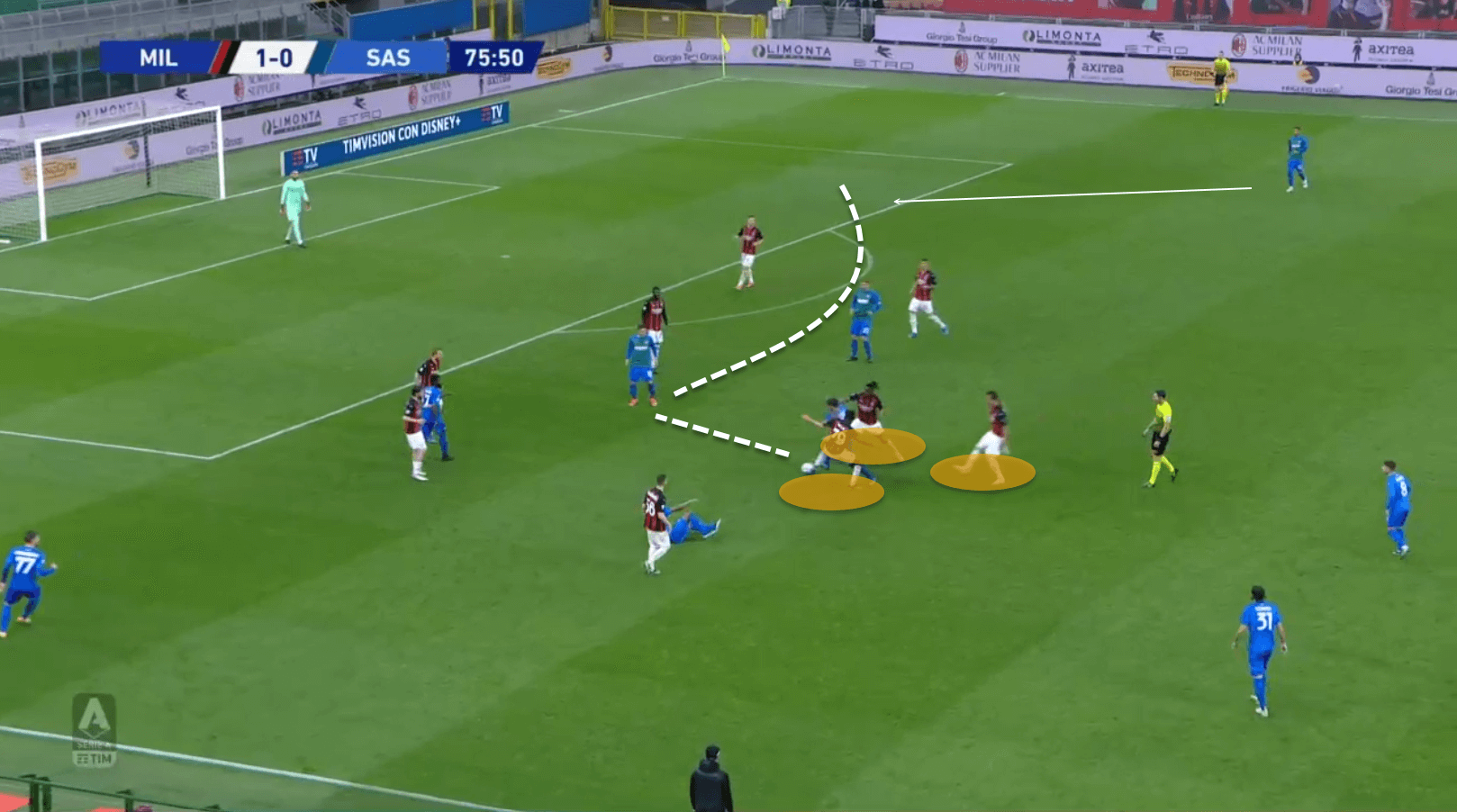

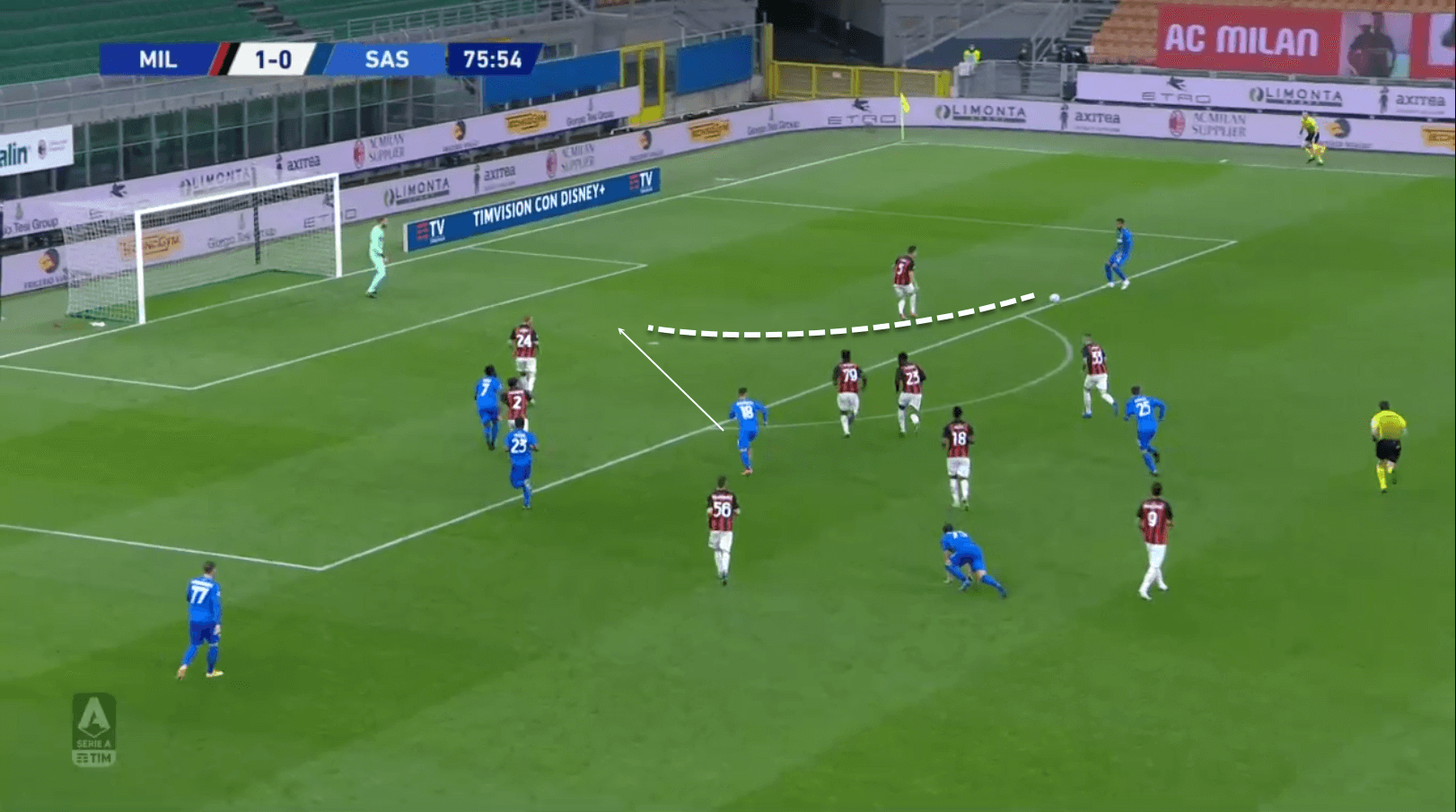

Again, De Zerbi can play around a press with his team’s strength in numbers and ability to exploit the gaps left by presses that pull the opposition’s formation out of shape. In Sassuolo’s 2-1 win over Milan, shown below, we can see Manuel Locatelli is swarmed by three Milan players, leaving space for Giacomo Raspadori to pass the ball out wide to an unmarked Jeremy Toljan, who can break into the box unchallenged to play a short pass back to Raspadori in the centre, who scores.

Defensive vulnerabilities

While De Zerbi gets his teams to play on the front foot and prioritise attack, overwhelming the opposition box with overlapping midfielders that stay high, this often led to the Sassuolo and Shakhtar defence being greatly exposed. In his 3 seasons as manager at Sassuolo, they conceded 179 goals with an average goal difference of just +2.3 per season. As Italian football has always taken pride in its defensive discipline, this led to criticism from journalists who claimed that his teams just couldn’t defend.

As De Zerbi has his teams constantly press the opposition on the wings, this can leave gaps to be exploited in the centre of the pitch and opposition players not being swarmed by Sassuolo often enjoyed lots of space. Once De Zerbi’s men regrouped to defend, they would stand off the opposition and would rely on the aerial abilities of the centre-backs to clear any crosses into the box.

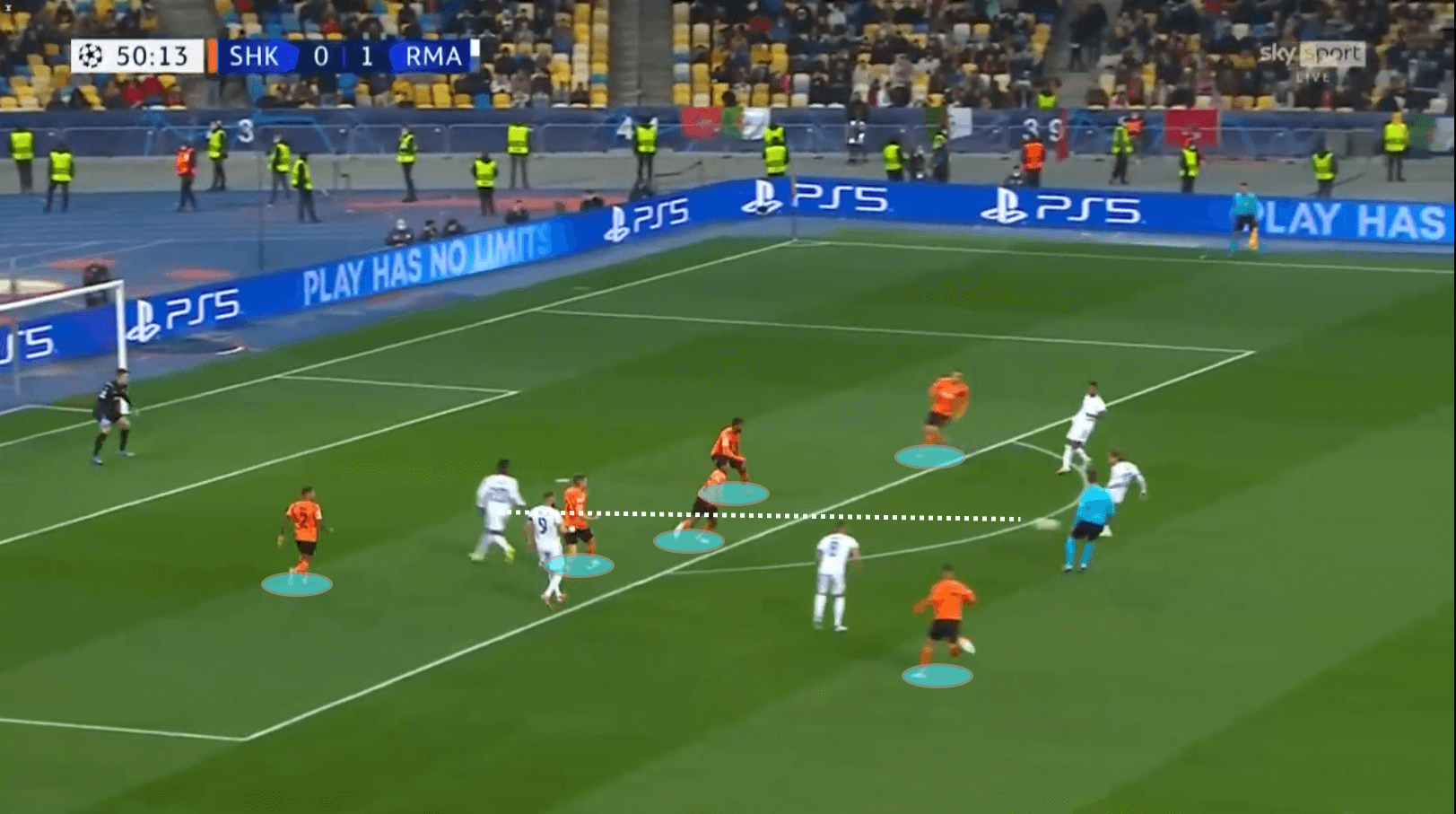

The images below from Shakhtar’s 5-0 Champions League loss to Real Madrid show gaps in the back line that Karim Benzema and Luca Modric exploit for Vinícius Jnr to score. The first shows all four Shakhtar players focussing solely on Benzema, unaware that Vinícius is already making a run into the space made by the defenders swarming towards the ball. The second image shows all six Shakhtar players looking toward Modric, now in possession, who cues up Vinícius to score a deft chip over Trubin. Both images show De Zerbi’s men ball-watching and leaving gaps from pressing in high numbers.

Adapting the Brighton players

It will be interesting to see how De Zerbi will use the players he has inherited at Brighton between now and the January transfer window. Potter left the Seagulls as a team that could use three defenders at the back, adapt their tactics depending on the opposition and rely on the skill and speed of midfielders Alexis MacAllister, Leonardo Trossard, and Pascal Groß.

Meanwhile, despite Tariq Lamptey’s patchy start to the season, we can expect to see him used in a similar way to how De Zerbi used Dominico Berardi on the right wing — someone who can use their pace to beat defenders and carry the ball once the opposition forwards have pressed and left gaps for him to exploit, stretching the defence.

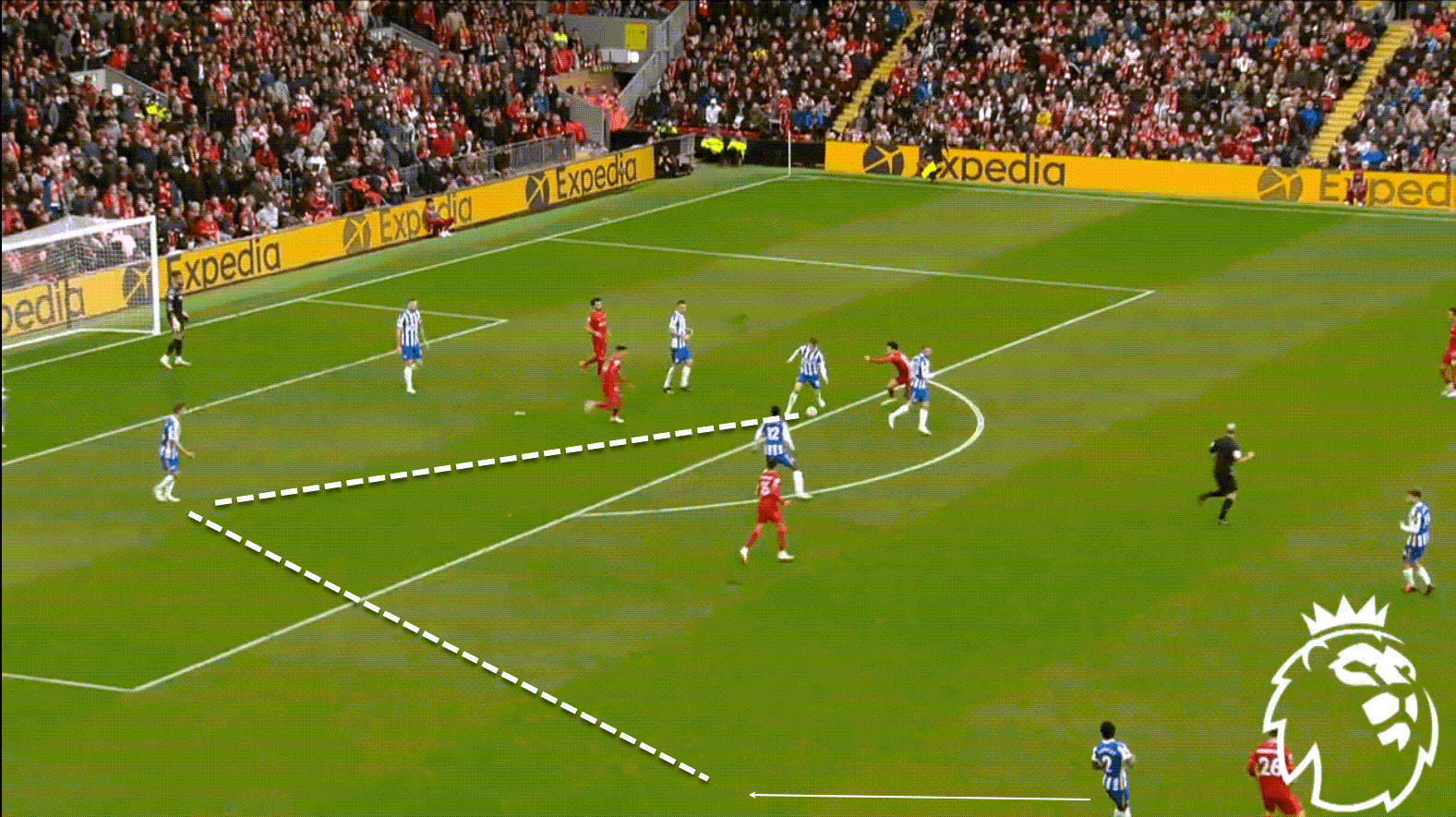

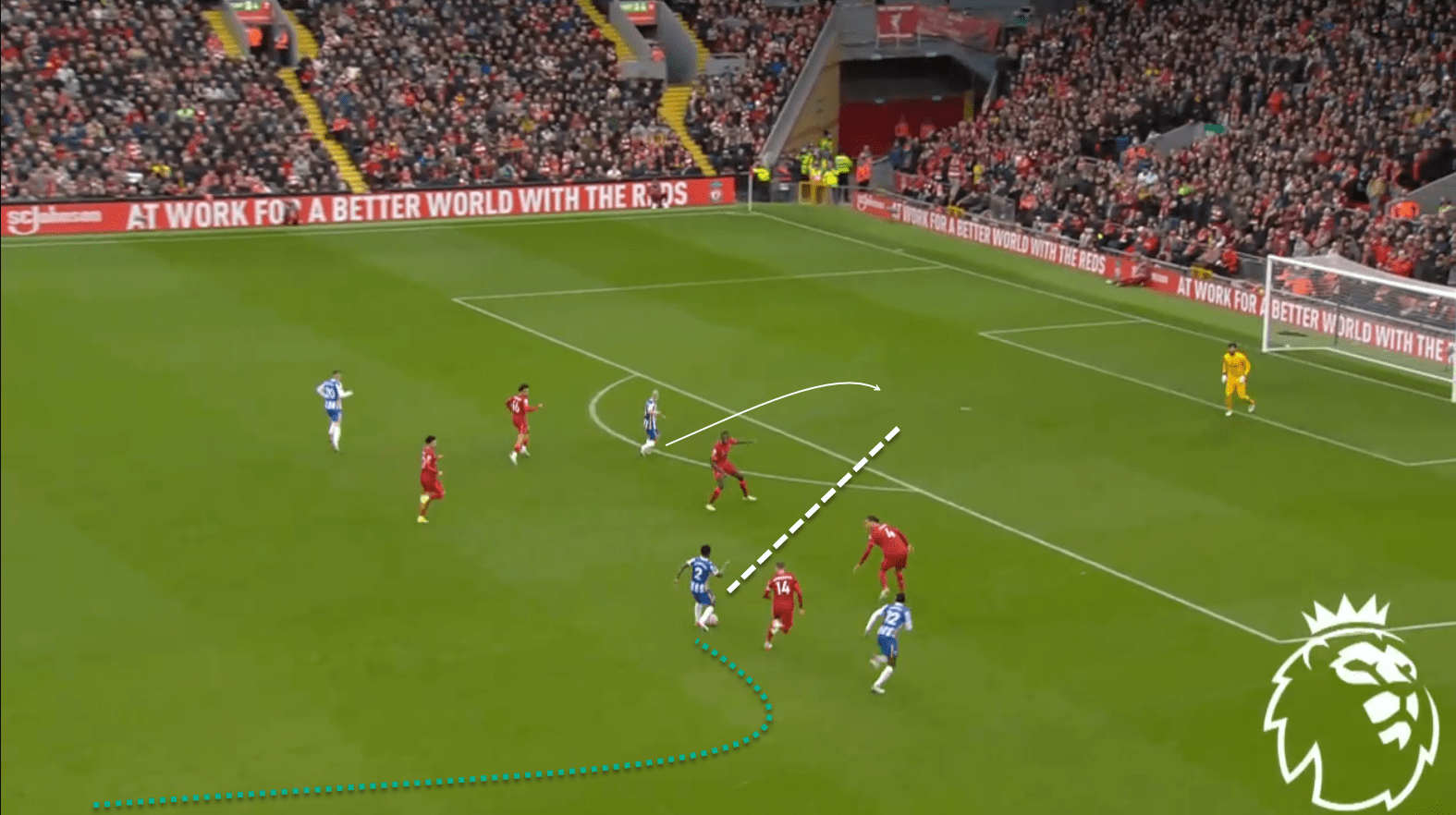

Below is a classic example of Lamptey’s physical play against Liverpool, where he peels off his marker as soon as Brighton regain possession in their box, plays a one-two with Adam Lallana, and carries the ball to the opposition box after and cutting inside to feed Trossard.

Because of the less athletic demands of Italian football and De Zerbi’s tactics stretching the opposition vertically, Sassuolo saw Berardi in a much higher position, often receiving the ball in the corner of the pitch from a diagonal ball or a midfielder who had carried the ball through the centre. Berardi would then go on to either play a through ball or cut inside for a shooting opportunity, rarely crossing the ball as per De Zerbi’s demands, as seen below against Milan.

Considered a box-to-box wing-back, Lamptey might have to curb his desire to make progressive runs as often as he does (ranked seventh at the end of the 2021/22 season), and although his crossing last year was fairly respectable with 19.8% accuracy, he will no doubt have to develop a more patient style of play under De Zerbi.

Conclusion

With his unique approach, De Zerbi has made lower reputation teams, such as Foggia and Sassuolo, overachieve, much like Potter did with Brighton. His football is not necessarily complex — stay compact, pass it short, play around the press to attack — and is not reliant on a team of superstars who can take multiple opponents on or play 40-yard passes. Potter left Brighton as a team that could use three defenders at the back, adapt their tactics depending on the opposition, and rely on the skill and speed of midfielders MacAllister, Trossard, and Groß.

All of this will suit De Zerbi, who has already been called a “natural fit” by Brighton owner, Tony Bloom. He has already promised to play brave football, use the talents of the current squad, and strive to keep Brighton in the top 10. Fans of the Premier League love to see coaches committed to exciting attacking football and, given De Zerbi’s record in just trying to score more than the opposition, we may see a gung-ho approach not seen since Kevin Keegan’s ‘Entertainers’ at Newcastle in the mid-90s.

Comments