Relationism is one of the hottest topics in the tactical world of football, and with Real Madrid’s constant success in the UEFA Champions League, it only becomes more relevant. In last season’s campaign, Los Blancos shocked the world time after time, making historic comebacks against PSG, Chelsea, and Man City. Against some of the world’s best tacticians, Ancelotti’s men were unphased, with complete serenity amongst the chaos. In fact, from the positional perspective that we have become accustomed to, Real Madrid’s tactics are chaos.

While there is still the collective intention to determine the outcome of the game, looking to develop possession rather than gambling it to chance, the linear organisations we tend to look for are not there. Unlike Man City’s 3-2 build-up shape, for instance, Real’s structure is emergent and non-imposed.

In this philosophy, where the intelligible has the same power as the sensible, the players’ movement and positioning become much more relationist. In every way. Abandoning spatiotemporal demarcations as reference points, tactics give way to relations which resemble a metaphysical connection, whether that is relations between the players, or between the player and the game.

As we continue to explore this philosophy, the spectrum of our analysis grows. While a majority of the work done on relationism so far observes the collective, it is time to also explore its individual dimension. In today’s football, Real Madrid’s Rodrygo can perhaps be seen as the symbol of relationism. To quote Ancelotti, “Rodrygo is not a specialist of a position, but of attacking football.”

The Brazilian’s importance to Los Merengues continues to rise, and in order to understand Rayo’s role in Ancelotti’s side, we must look at it from a relationism point of view. In this scout report, our tactical analysis takes on a new level as we explore Rodrygo’s role in Carlo Ancelotti’s Real Madrid.

(Every)Where

In Brazil, there is a growing feeling that the heir to Seleção’s 10 is Rodrygo. More than the shirt number, Rodrygo assumes the historic role of a Brazilian 10, a playmaker without positional restrictions. Similar to Neymar with the Amarelinha, Rodrygo’s role in Real’s tactics is becoming a central one. The former Santos player has always been known as a winger; however, he is far from a typical wide player.

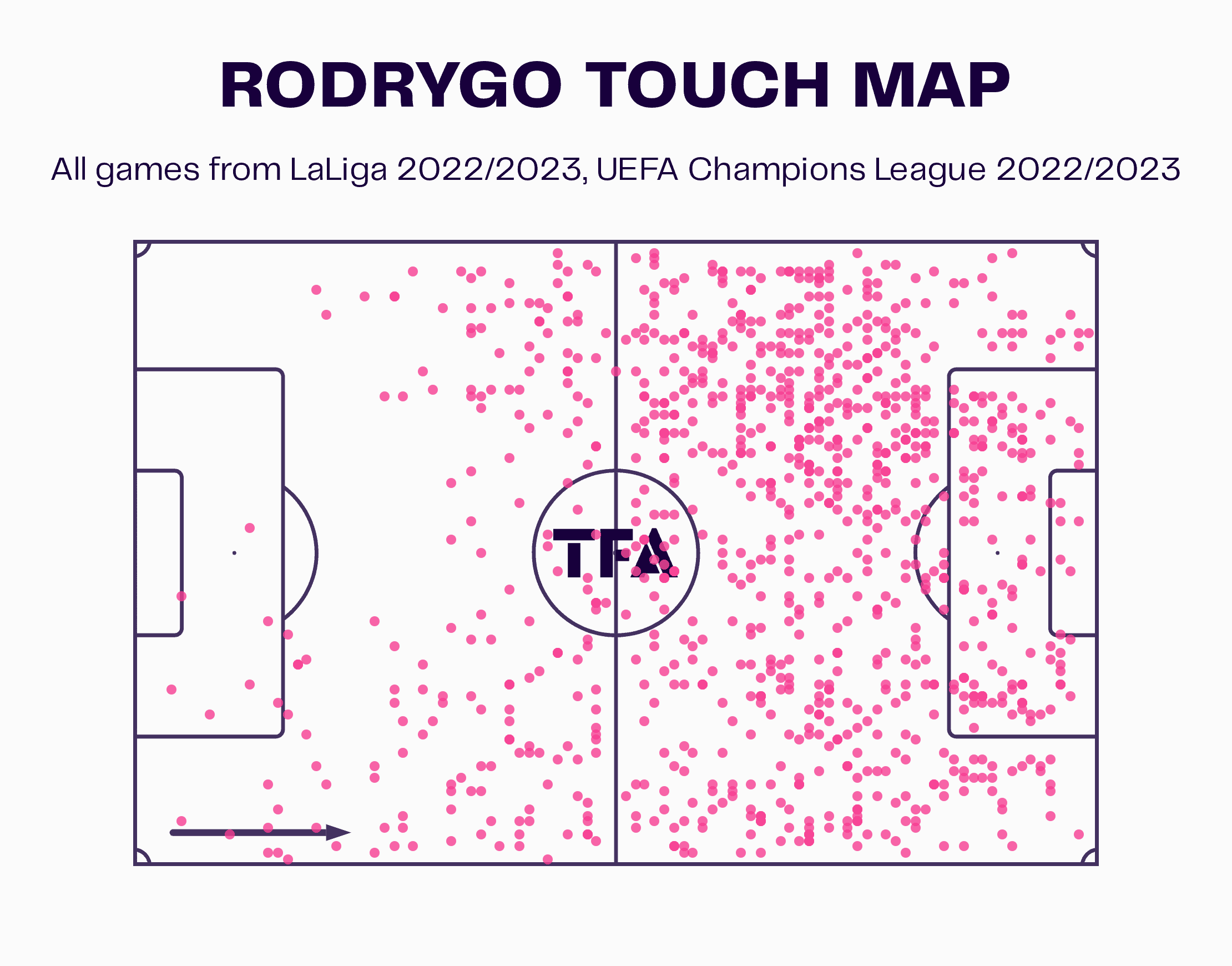

Looking at his touch map in this season’s La Liga and Champions League, Rodrygo roams throughout the entire attacking half. From Ancelotti’s loose 4-3-3, he either starts as a right or left winger — if we can call it that. When Los Blancos have possession, the 22-year-old roams the central lanes without much restriction or spatial reference.

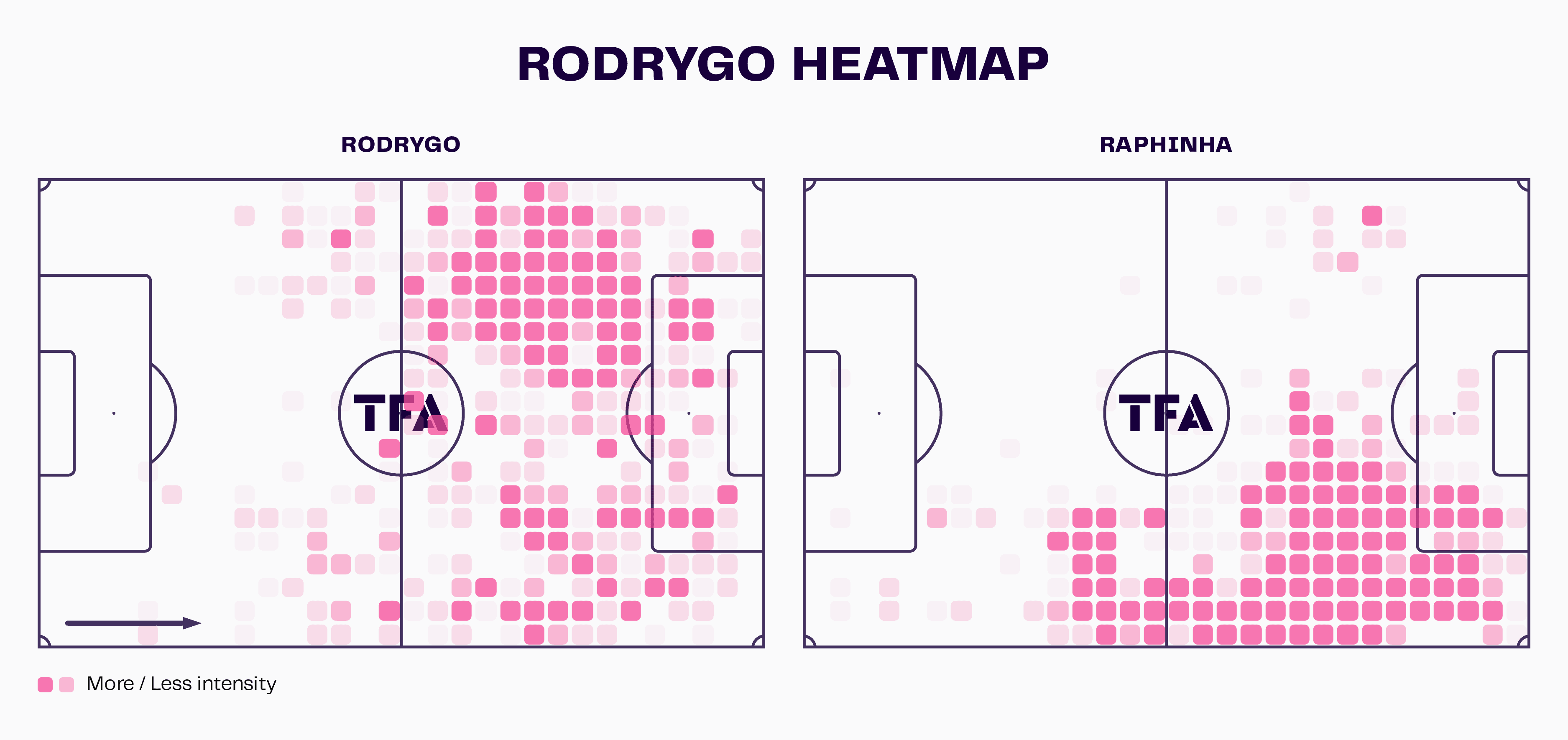

To paint a clearer picture, we can use another Brazilian in a completely different environment as a comparison. Raphinha’s transition to European football was the complete opposite of Rodrygo’s — away from the spotlight and Ancelotti’s guidance. Similarly, while Rodrygo plays in Real Madrid’s functional side, Raphinha is at Xavi’s Barcelona with textbook positional play.

On the left, Rodrygo’s heatmap tells a similar story to his touch map, one of roaming and positional freedom. On the other hand, on the right, Raphinha’s heatmap is completely different. The Barcelona winger’s movement is much more focused on the right-wing channel, slightly bleeding over into the half-space in some areas.

Rodrygo and Raphinha, despite being Brazilian, are entirely different players — a product of entirely different processes. When understanding a player’s positional characteristics, it is important to consider their path in football in addition to the tactical system they are a part of.

While one developed under functional schools and significant expectations, the other quietly developed his way through the European pyramid. This process has a monumental influence on their relationship with the game as a whole.

Moving over to the pitch, we can use a few examples to highlight how Rodrygo occupies spaces in possession. Despite how often he floats through the central channels, the Brazilian still has width and depth to his game. At times, he finds himself occupying the wide areas to stretch the pitch and make runs attacking the space behind the backline.

However, this behaviour is far from universal in possession. Whether Rodrygo sees this movement as appropriate or not depends on multiple factors, including where the ball and the players are, the situation of the game, and more.

On the other hand, and this is perhaps more intuitive to him, he frequently abandons his wide origin and drifts into the central channels. Against Villareal below, Rodrygo’s actual position in comparison to his theoretical position in a 4-3-3 is clearly illustrated. As he floats into the centre of the pitch, he is in search of support, making himself available to the game.

Almost 20 seconds later, Rodrygo continues to roam into the central channels without any sign of returning to the right wing. This has some obvious consequences when the defensive organisation is taken into account. His distant journey from the right wing often tends to make him the extra man, as he is in the midfield below for example. However, this movement isn’t a tactical strategy to create an overload, but rather a natural intuition to find the game and support his teammates.

Apoio

Apoio — or in English, support — is at the heart of Brazilian football. Thinking back to the historic Brazilian sides of 1970 or 1982, it was the idea of Joga Bonito that characterised those sides and, in general, Brazilian football. In this approach, the proximity between players was much closer, and in this structure, the interactions and relations were heightened.

In this close proximity, the team’s structure tends to become asymmetrical and emergent, without imposed shapes or organisations. These are features we are now assimilating to the likes of Real Madrid and Fluminense, or functional play.

With this cultural dimension, it is natural for Brazilian players to apoiar — or provide support; their movement is more ball-oriented and less structure-oriented. This is a trademark characteristic of Rodrygo’s role in Ancelotti’s tactics.

Take the instance below, against Chelsea for example. Los Blancos have the ball on the right wing as they try to break down Chelsea’s low block. Luka Modrić and Dani Carvajal are there while Rodrygo, the “right-winger”, finds himself in the box. The Brazilian immediately moves closer to the ball, looking to find a space to receive the ball and play with his teammates.

A few minutes later in the match, we can identify another instance where the Brazilian looks to provide support to his teammates. Rayo significantly moves from his right-wing position to the central lanes, where Toni Kroos, Karim Benzema, and Eduardo Camavinga are found. Kroos, the ball carrier, finds Rodrygo who performs a “parede”, or wall bounce, to Benzema.

However, it’s not all about moving towards the ball. Understanding the references around him (ball, opposition, teammates) allows Rodrygo to make the most appropriate movement. Below, for instance, Marco Asensio receives the ball in the left channel after a sequence of short passes between a few players. After receiving it, Asensio finds himself with space to attack and accelerates the play.

First, the space Asensio attacks is made available by Rodrygo. By moving across from the right wing, the 22-year-old occupies Villarreal’s midfielder and keeps him from moving over to close down Asensio. Secondly, as Asensio accelerates possession and makes it more vertical, Rodrygo moves accordingly and runs forward, away from the ball. This is crucial in allowing Asensio to continue his run without congesting or slowing down this vertical scenario.

Relate

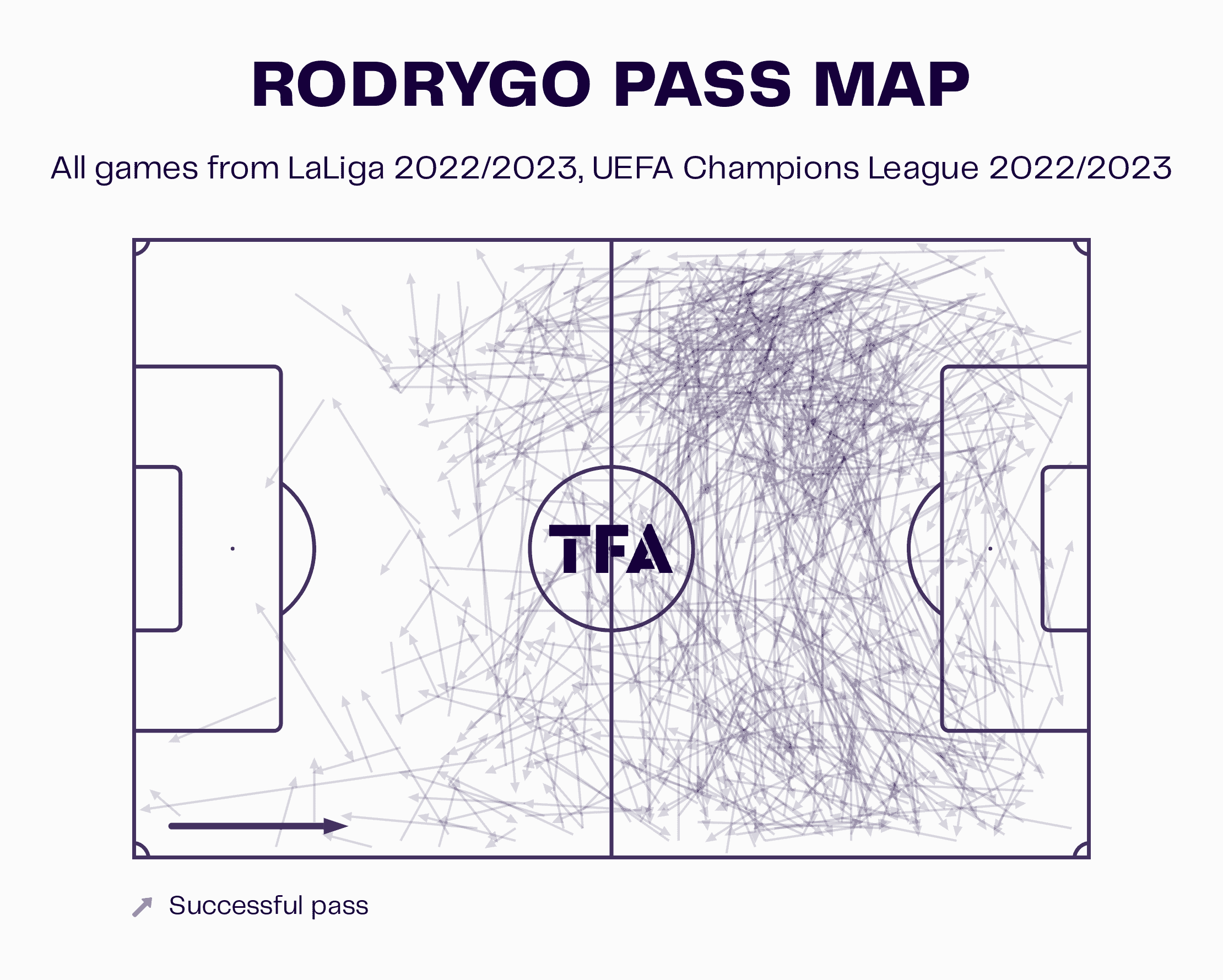

The fundamental purpose behind the Brazilian’s apoio (support) is to relate. Rodrygo essentially explores the pitch looking for opportunities to connect and interact with his teammates, and as a consequence, his pass map spreads all over the pitch. Observing the location of the passes, it resembles the pass map of an entire team — it is truly all over the attacking half.

Connecting this pass map with where his teammates more or less tend to be, we can visualise how this plays out. There is a slight superiority on the left side of the pitch, where Vini is. Los Merengues often tend to concentrate players on this side of the pitch, and the passing connection, consequently, tends to be shorter. On the other hand, on the right side, the passing distances increase and become more sporadic throughout the pitch.

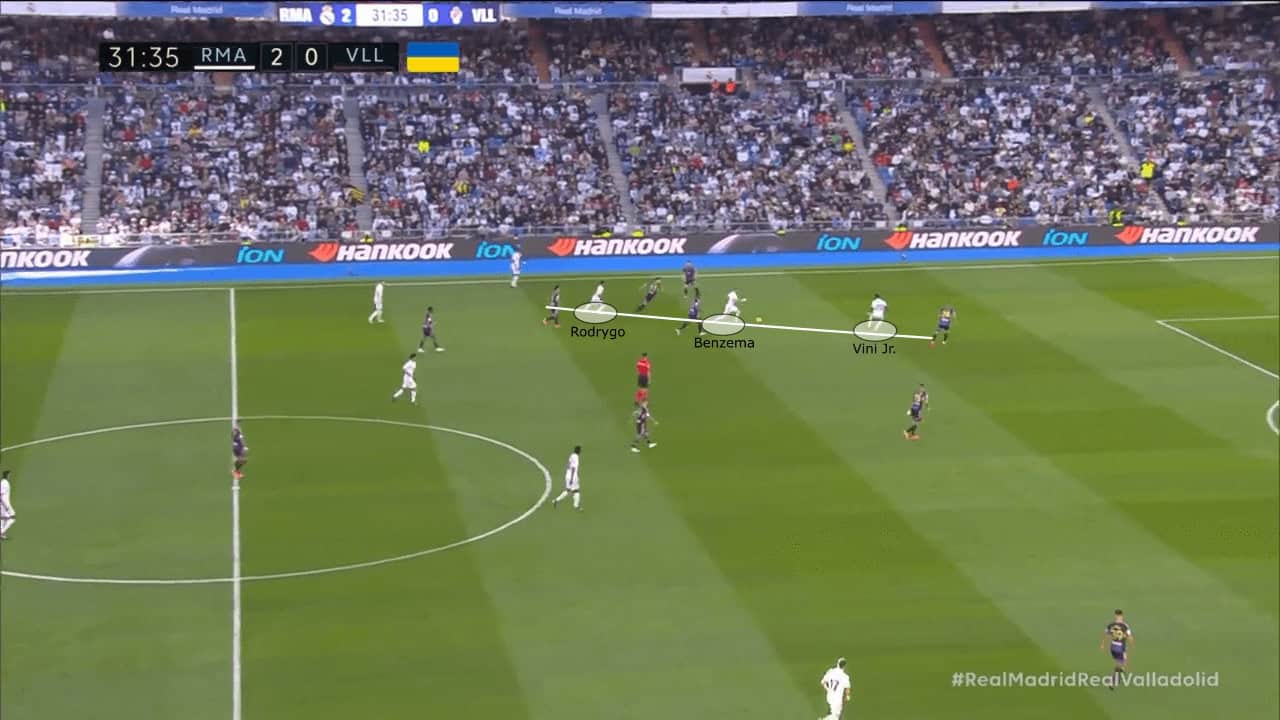

This tendency to concentrate on the left side of the pitch is significant, and it can be illustrated in the image below. Right off the bat, the asymmetrical structure is clear, alongside the non-linear nature of the player’s organisation. Once again, Rodrygo abandons the right side to support and relate with his teammates. Observing the image below, he is in immediate proximity to Camavinga who is making a forward run, Benzema behind him, and Asensio at a more obscure angle.

Vertical staircases — or as they are called in Brazil, escadinhas — are quite a common occurrence in Real Madrid’s structure. It is essentially when three or more players line up in a vertical or diagonal line. The more typical development to this structure is a vertical pass looking to skip the middleman, who can peel off to provide an immediate option as the furthest player receives the ball.

Another method of exploring this structure is through what is called a corta-luz in Brazil — or, simply, a dummy. Again the pass is looking to skip the middleman, but this time with more emphasis. There are multiple ways of exploring this, and it is completely situational, but the emergence of these vertical structures is quite common (and natural) in functional teams.

In the instance below, we can see how Rodrygo performs the middleman role as Dani Ceballos finds Benzema. Rodrygo clears up the passing lane before providing immediate support to Benzema as he receives it. After getting the layoff from the French striker, Rodrygo is carrying the ball facing the goal and attacking the backline, an ideal scenario.

These spontaneous relations with his teammates are a result of the close proximity in Madrid’s structures, and the development of these relations is extremely situational. Rodrygo plays a vital role in this functional approach to possession — and it plays directly into his culture and development as a player.

Conclusion

As Real Madrid continue to find success in the Champions League, the relevancy of Relationism continues to grow. With it, a new lens of analysis and tactics emerges, or rather re-emerges, from the 20th century.

Nonetheless, the concept continues to be explored by the analysis community and the philosophy transitions from an abstract state to a more concrete and explorable alternative for coaches and analysts around the world.

To continue this transition, it is important to broaden our analysis of Relationism to an individual perspective, and Real Madrid’s Rodrygo is the perfect example.

Comments