As the Premier League drew to a close this season, so did Southampton‘s decade-long stay in England’s top flight.

Over the five years, the side have experienced a steady decline, from once participating in the UEFA Europa League to consistently finding themselves in the relegation battle.

Russell Martin‘s trajectory as a coach, in contrast, over the last five years has risen exponentially, with the former Premier League player excelling at MK Dons and most recently Swansea.

On and off the training ground, Martin has managed to instil belief in his players as well as the fans of both his previous clubs, through possession-based football and an evident passion for the game.

This tactical analysis will provide an analysis of Southampton’s tactics in possession and highlight the side’s key weaknesses in possession and how Russell Martin can improve this aspect of the side.

Southampton’s struggles in progression

Southampton in their most recent Premier League campaign finished with just 36 goals in the league, with this total being the third least in the entirety of the league.

This figure is not a result of poor finishing, as the side only underperformed their expected goals by three goals, which would still rank them among the bottom three teams in the league.

This suggests that the side, over the last season, struggled to even create chances which can also be seen through the fact that the side only managed 20.08 penalty area entries per game, the lowest in the league.

Before fully analysing the reason why Southampton struggle to create chances in the final third, their build-up play in the first two-thirds must be assessed.

Southampton in build-up

In their own third, Southampton build up with a back four with their full-backs advancing slightly and their double pivot of James Ward-Prowse as well as Roméo Lavia.

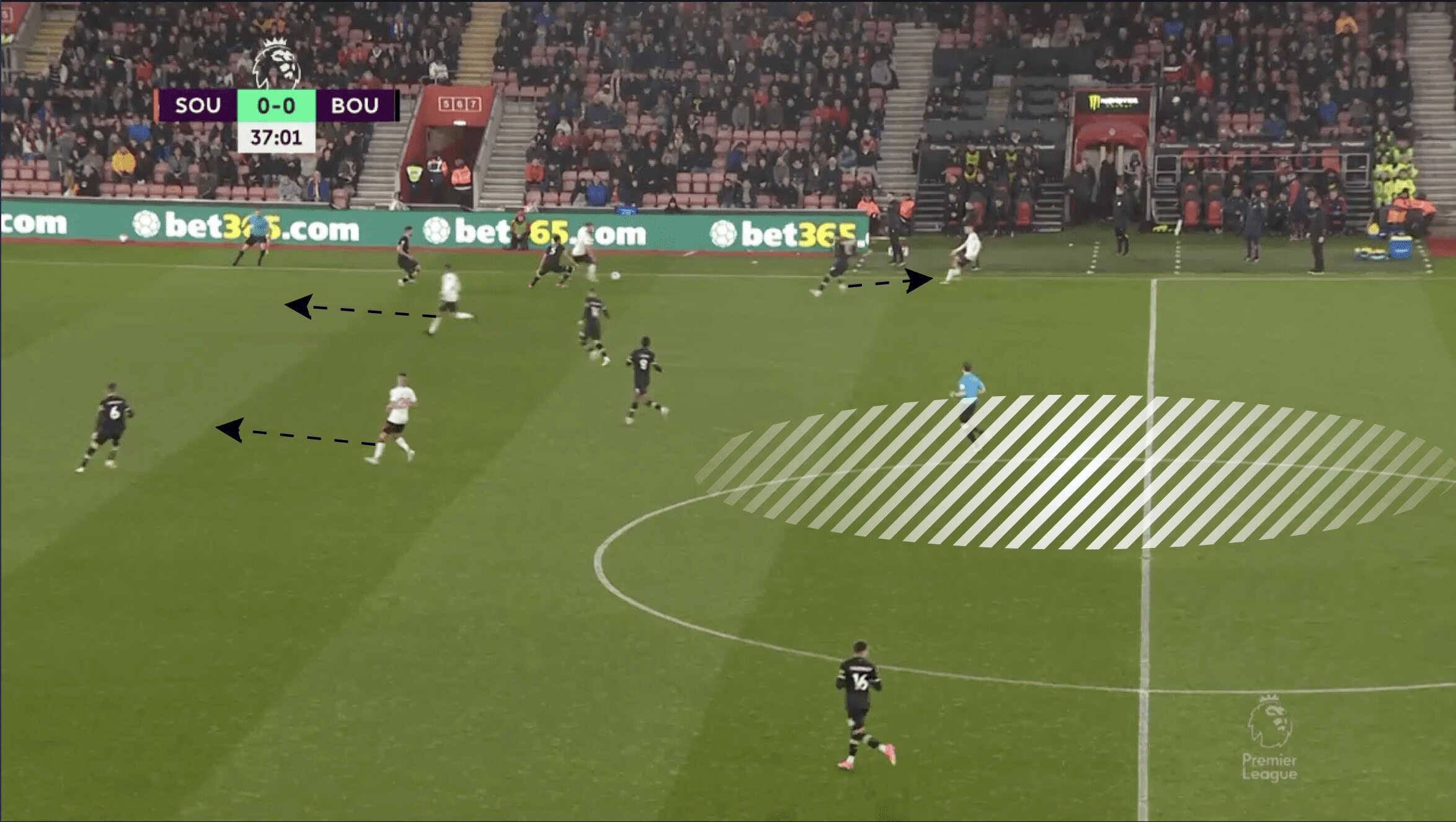

An example of this can be seen in the image below.

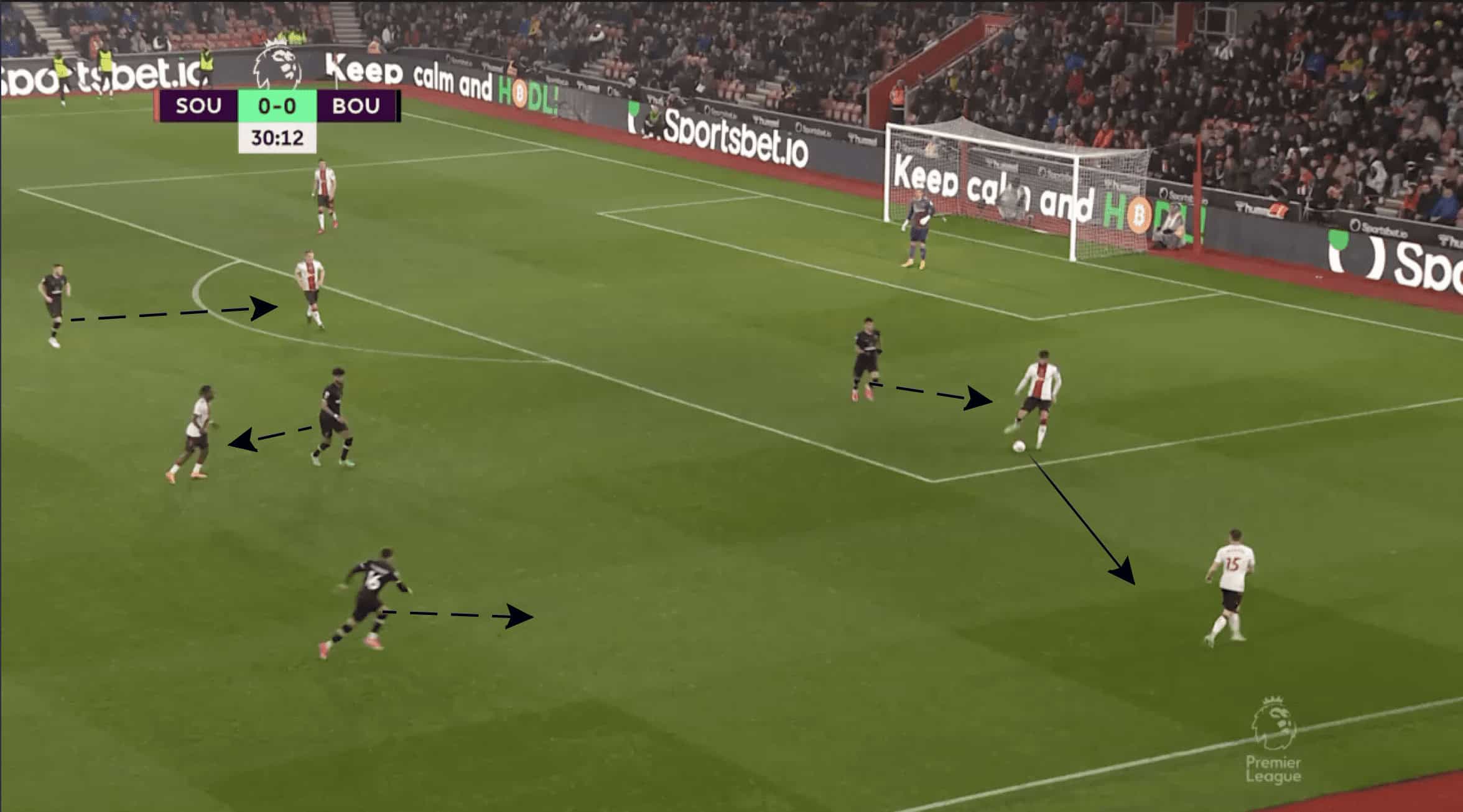

Southampton’s centre-backs from these positions will look to play passes to either Ward-Prowse or Lavia but due to the midfielders often facing aggressive opposition pressure, they are only able to play passes back to their defenders.

As a result of this, a large amount of Southampton’s play is directed towards the wide channels, with the centre-backs playing passes to the full-backs.

This can be seen in the example below, with the former Marseille defender Duje Ćaleta-Car playing a pass to Romain Perraud.

This sort of scenario causes two main issues for Southampton.

The first and most obvious is the fact that in the wide areas, players receiving the ball have a limited amount of space due to the touchline.

This means that when the full-backs receive the ball, their next actions can be somewhat predictable as there are only a handful of passes that can be played if the opposition supports each other well.

As shown in the image below, the opposition players have covered Ćaleta-Car as well as Lavia, meaning Perraud can only play a pass down the line.

When Adam Armstrong receives the ball, he then looks to play a pass inside, but the opposition players are in good positions to cover the Southampton players and are able to force a turnover.

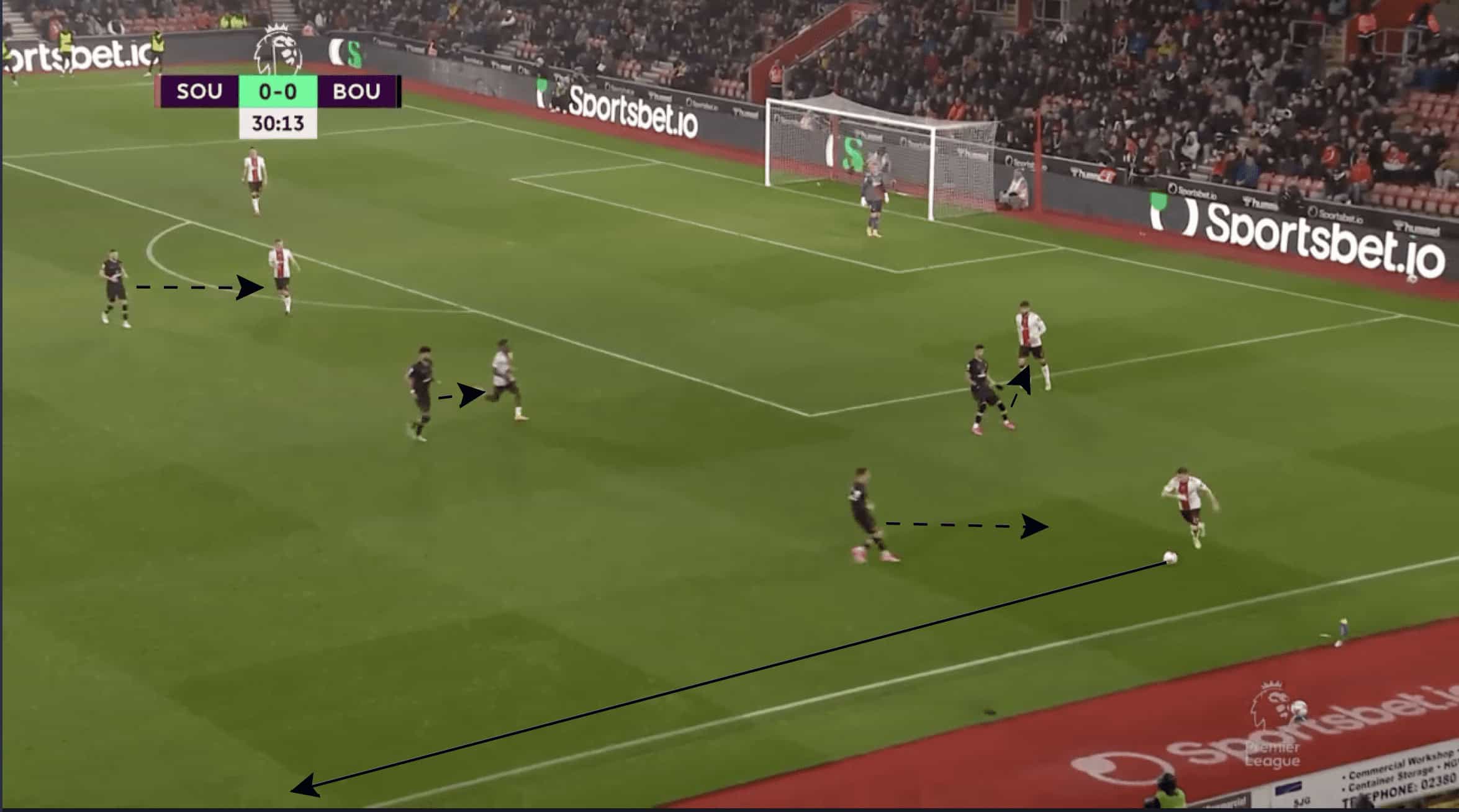

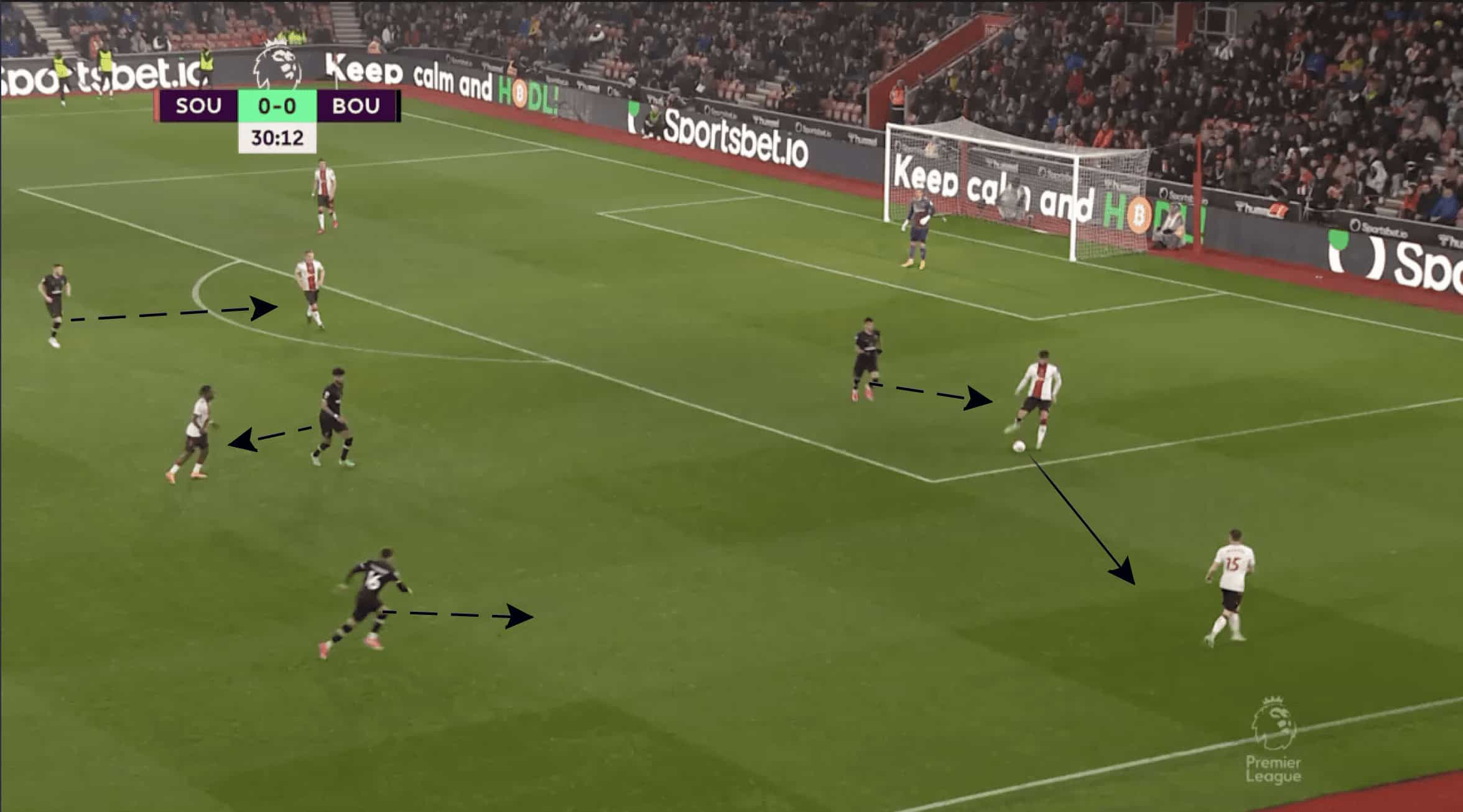

A second issue with the structure of Southampton’s build-up is the position of their full-backs.

Due to their method of progressing the ball in the wide areas, their full-backs are often times the recipient of passes from their centre-backs.

As a result, they often build up with a relatively flat back four.

If the opposition press is high, this creates easier situations for the opposition to press the Southampton players.

From the scenario below, the position of Perraud is deep enough to allow the opposition winger to protect the space behind him as well as have quick access to Perraud if a pass would be played to the full-back.

The opposition’s right winger is not forced to make any decisions in regard to his positioning.

If Perraud were to advance and the right winger was to drop deeper as a result, more space could be created for Ćaleta-Car to advance the ball, forcing the other opposition players into making a decision whether or not to press the centre-back, which would create space for other Southampton players.

The depth of their full-backs would not entirely be an issue if it were not for the distances between the midfielders in the double pivot and the two attacking midfielders.

This has the resulting effect of the side being disjointed and limits the number of passing options the side can access in the build-up.

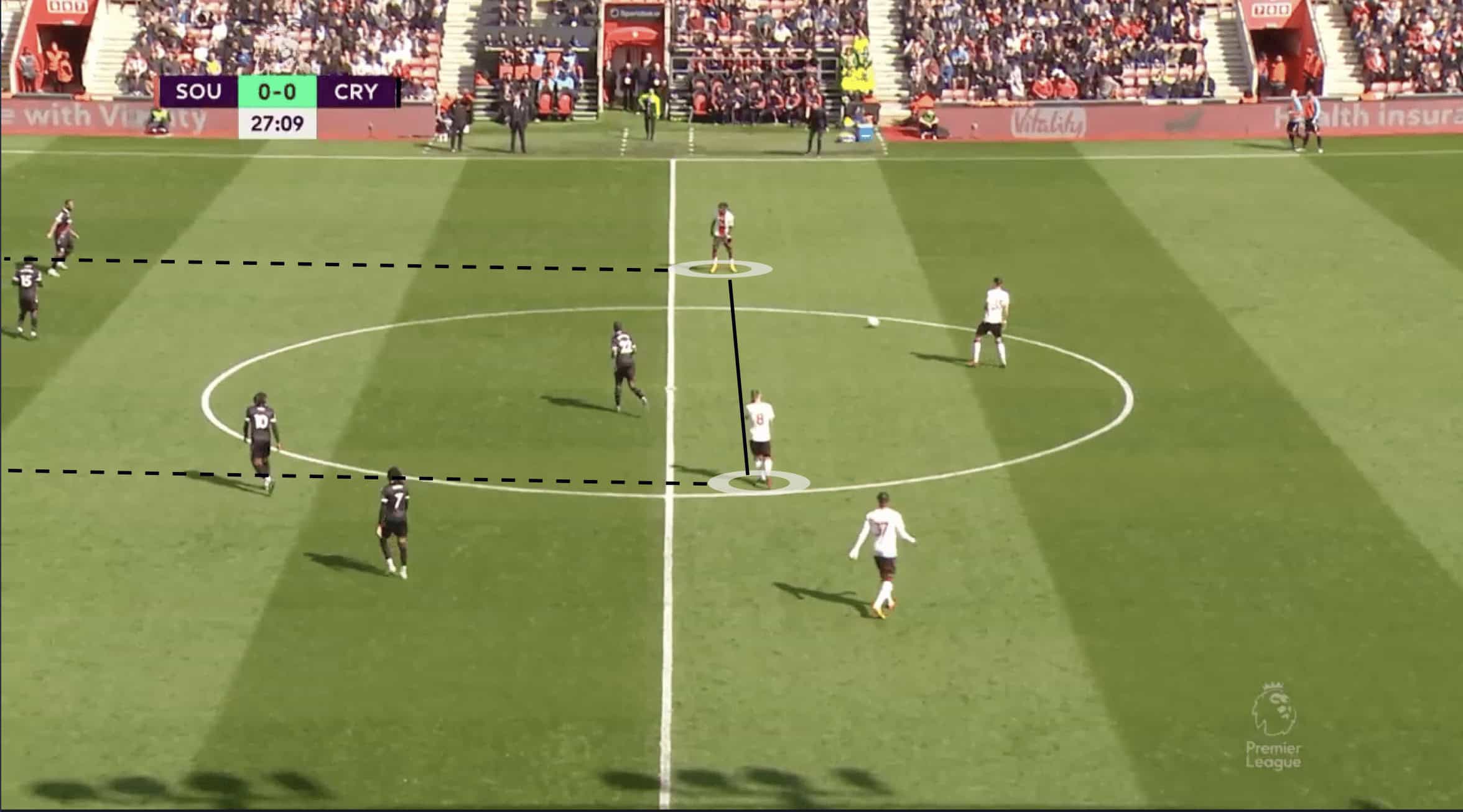

The relatively large distances between the attacking midfielders and double pivot can more clearly be seen further up the pitch in the middle third.

In the example below, Lavia as well as Ward-Prowse are only a couple of meters in front of the centre-backs with the rest of the attacking players in more advanced areas.

This once again creates a favourable situation for the opposition as with no threat directly in front of the midfield line of the opposition, they are not forced into making a decision over whether to press the ball carrier or cover Southampton’s attacking midfielders behind them.

This also creates an inability for Southampton to sustain attacks as well as pressure, which would give them more opportunities to enter the final third.

This can be seen in the image below with Armstrong receiving the ball on the right-hand side.

Theo Walcott as well as Carlos Alcaraz then attack the space created in the back line.

However, the midfield is left unoccupied.

With no support from behind the ball, Armstrong, with his back to goal, has limited options, reducing the ability of the side to sustain the attack and potentially take advantage of a promising situation.

As result of this, a large number of Southampton’s attacks are stifled before they even get a chance to enter the final third as well as the penalty area.

Russell Martin’s Swansea

It is highly likely that Martin will not look to copy and paste the game model he implemented at Swansea with this Southampton side but the principles of the game model can help suggest how he can improve this Southampton side.

From analysing Swansea’s build-up play, differences can already be seen in regard to the distances and connections between players.

Martin has stated that something he has particularly emphasised to his players has been close distances between them in both attack and defence, in order for players to support each other on and off the ball.

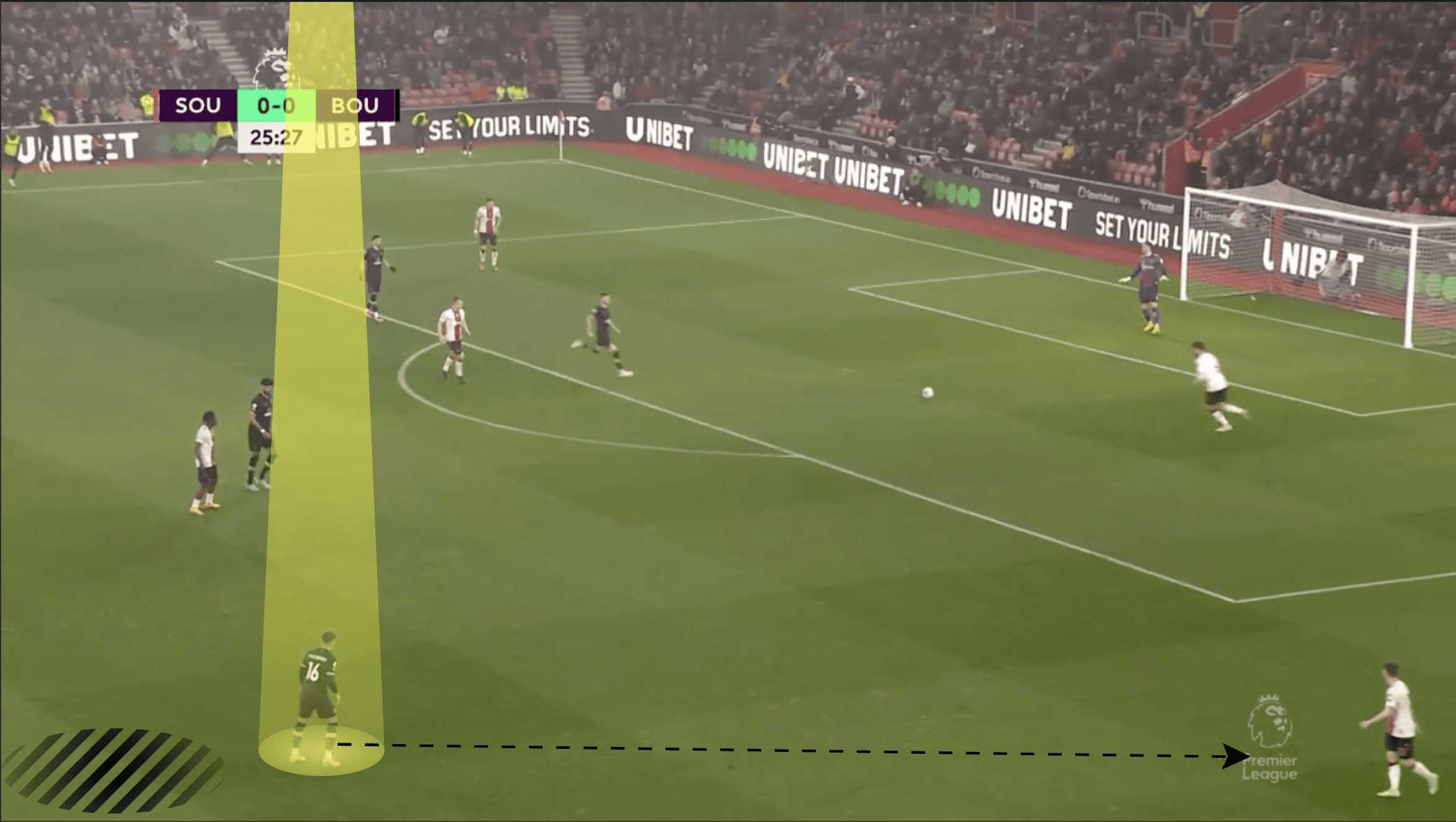

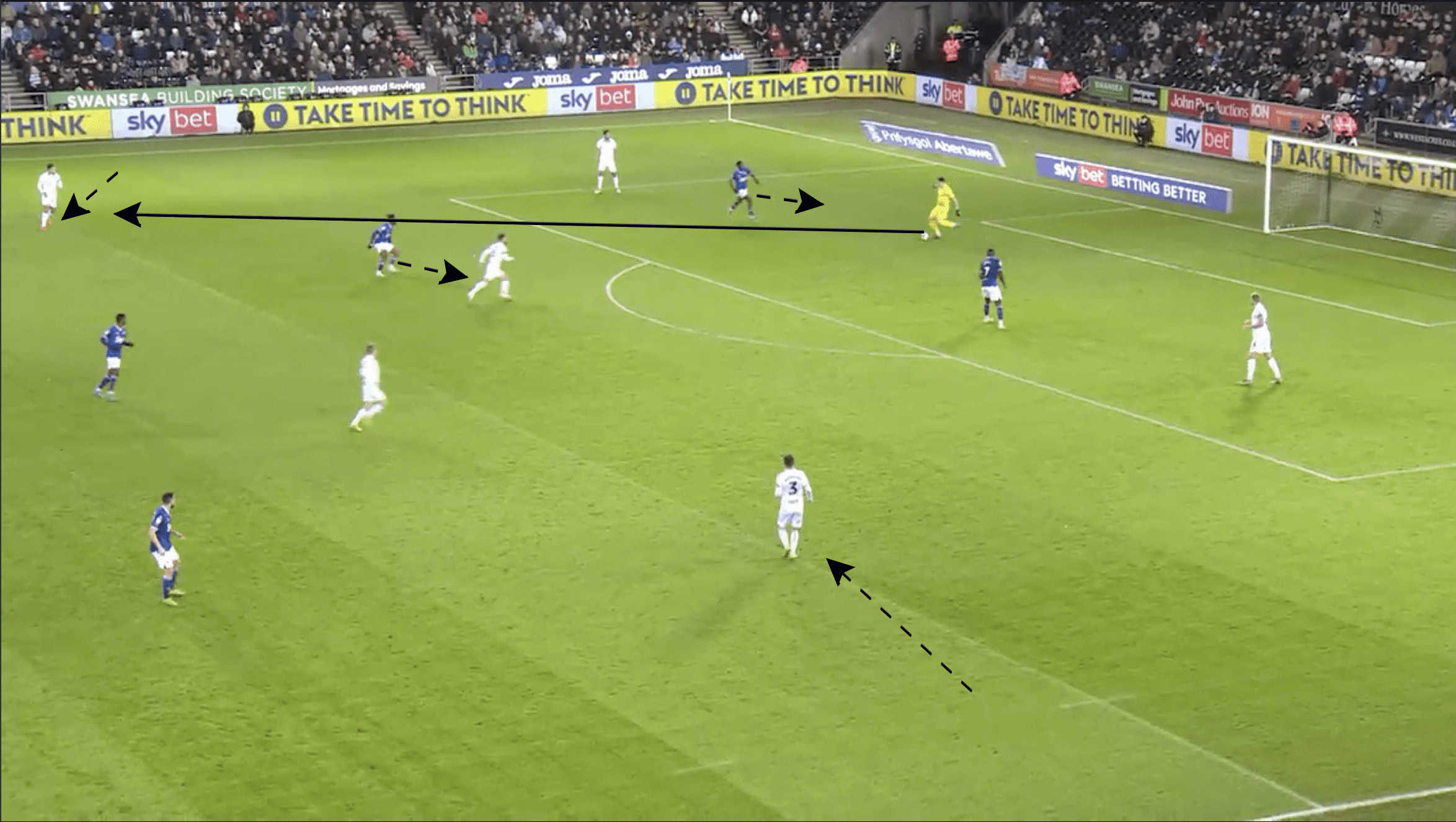

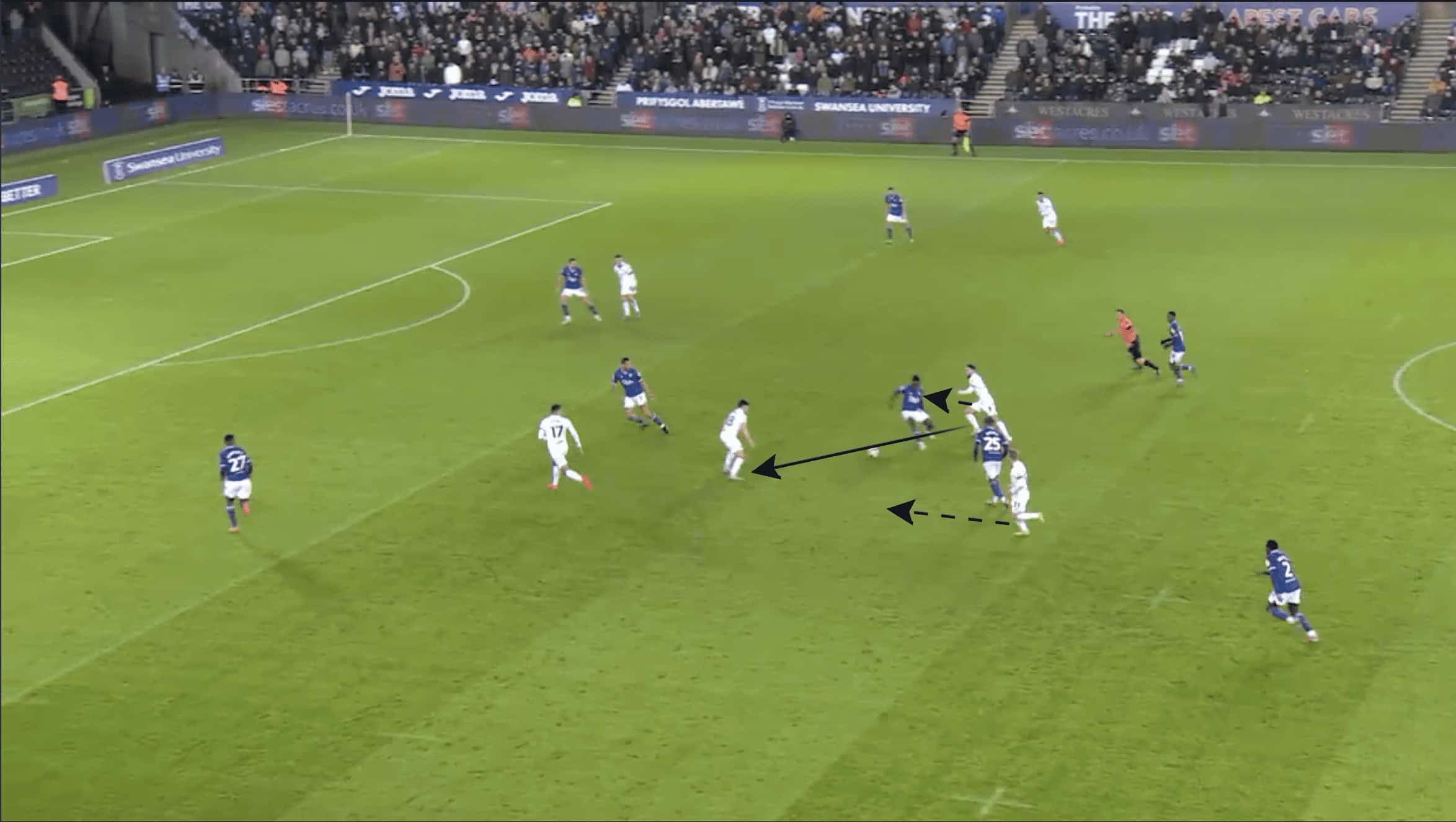

The example below shows Swansea’s structure in the build-up, with the side forming a 2-4-2-2.

Within this structure, Swansea have nine players in their own half and only two in the opposition half.

In addition to this, what is also particularly intriguing is the fact that full-backs utilise minimum width.

Minimum width is a concept whereby full-backs or wingers (in this case full-backs) do not look to hug the touchline but only move as far wide as needed for particular situations.

From Swansea’s perspective, in the build-up, full-backs will often adjust their positions in order to provide support for the centre-backs and goalkeeper and create new and different angles as well as passing lanes.

In the example below, as the Swansea double pivot moves towards the right in order to offer support to the goalkeeper, space is created on the right-hand side of the central area as the opposition players adjust their positions to the midfielders.

Joel Latibeaudiere, the right-back, recognises this and indents his position in order to give the goalkeeper an additional option for a pass.

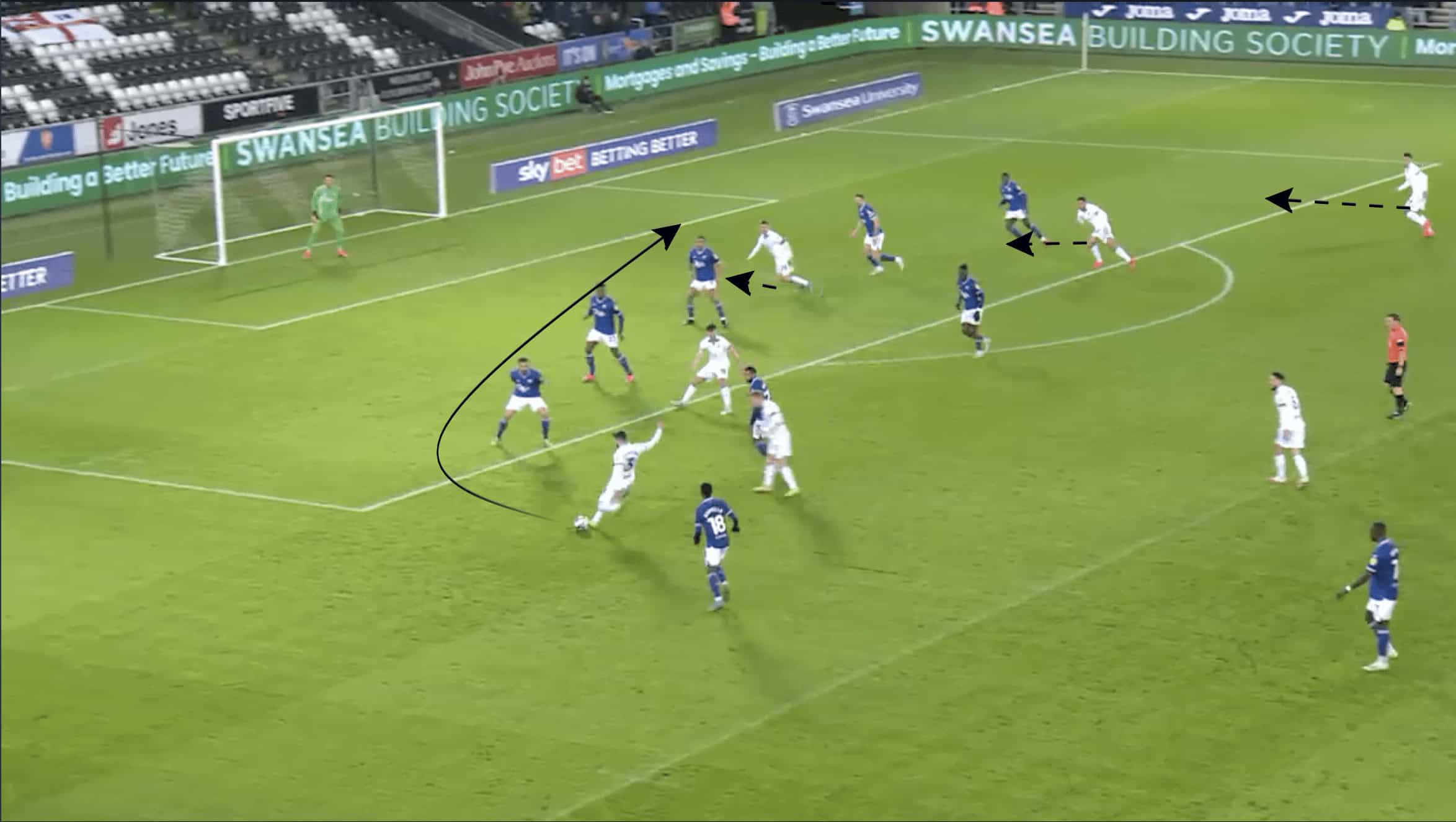

Another example of this can be seen in the image below, but this time, the left-back Ryan Manning moves from a wider position into the midfield.

This has a number of benefits as it directly ties into how Swansea look to progress the ball, with the side under Martin progressing the ball through central areas.

The movement of full-backs into more central spaces allows them to overload the centre and as a result, have a free man.

In the example below, as Matt Grimes drops deeper, opposition players adjust their positions in order to cover the midfielder, creating space between the first and second lines.

Due to the position of the advanced Swansea midfielders, the second line of the defence of the opposition is pinned back, giving Manning time and space to receive the ball.

What can also be seen in the previous example is the staggered nature of Swansea’s structure as well as the distance between each line.

As a result of both the staggering and distances, players are able to support the ball carrier, but in addition to this, Swansea are able to create and exploit the dilemmas faced by the opposition and progress the ball.

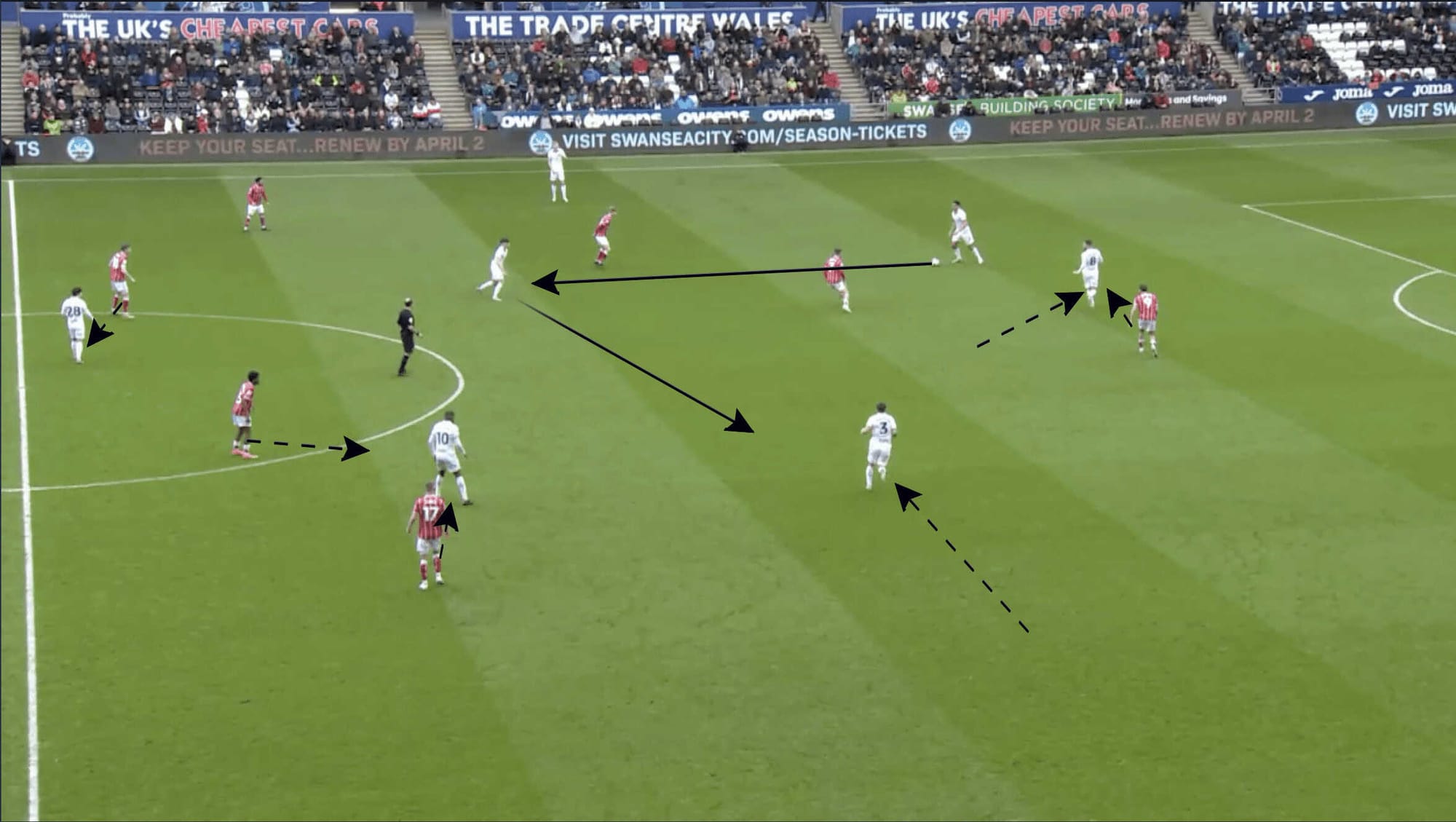

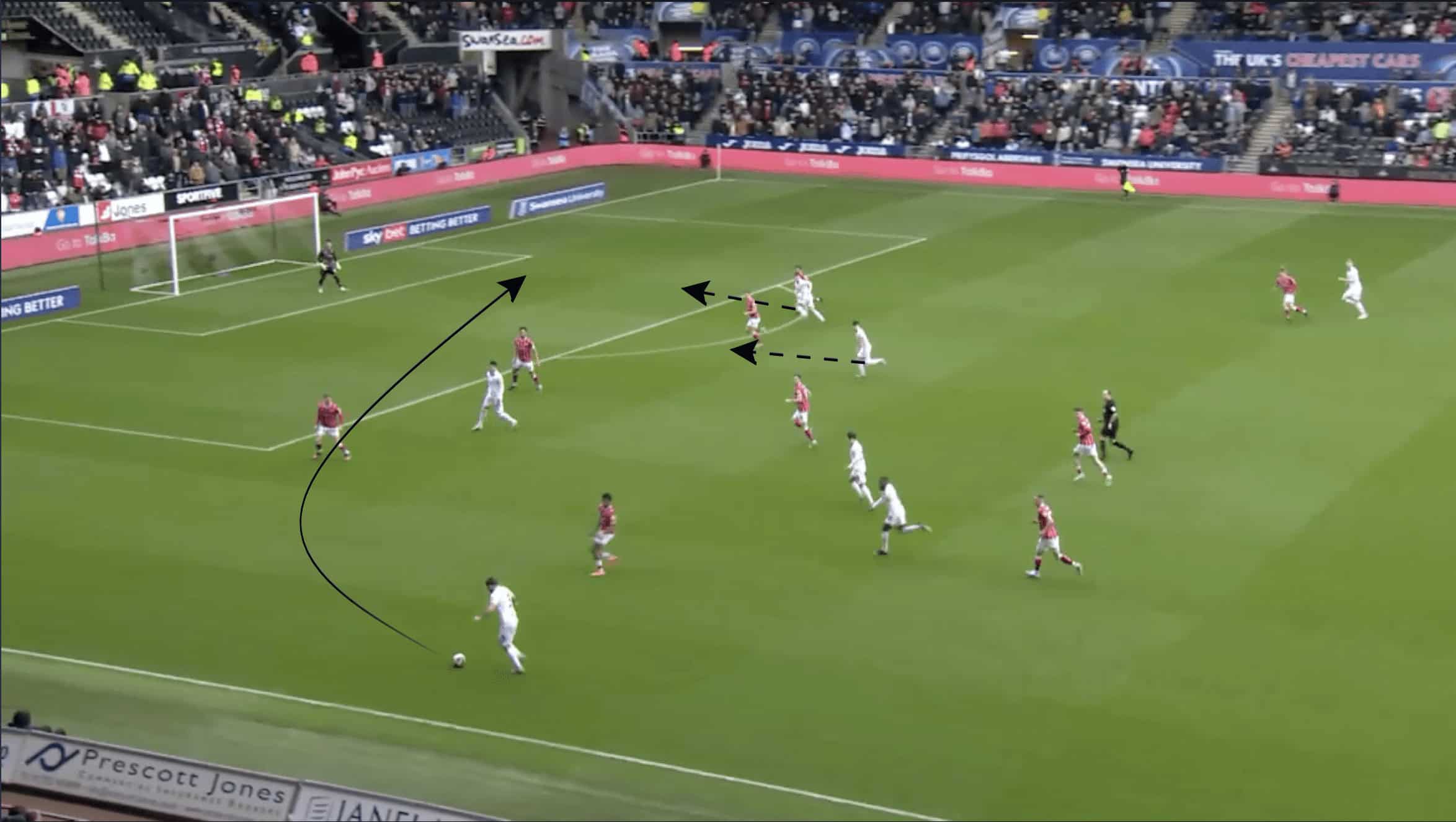

What can also be seen in Martin’s Swansea side is the dynamic occupation of space in more advanced areas, particularly by the advanced midfielders in the side.

There are shades of this dynamic occupation of space in the movements of full-backs in the early stages of build-up, but this can especially be seen in more advanced areas.

The advanced midfielders as well as strikers in the side look to receive the ball in between the lines and move in order to either receive the ball or create space for other players to receive the ball.

This can be seen in the example below with Manning on the ball in the central area.

Space is available in the left-hand channel.

Jamal Lowe, as a result of this, moves towards the left in order to provide width in the attack, with the opposition midfielder adjusting his position in order to cover Lowe, which creates more space in the centre.

Liam Cullen, the striker, then drops into the space created in the centre and receives the ball from Manning.

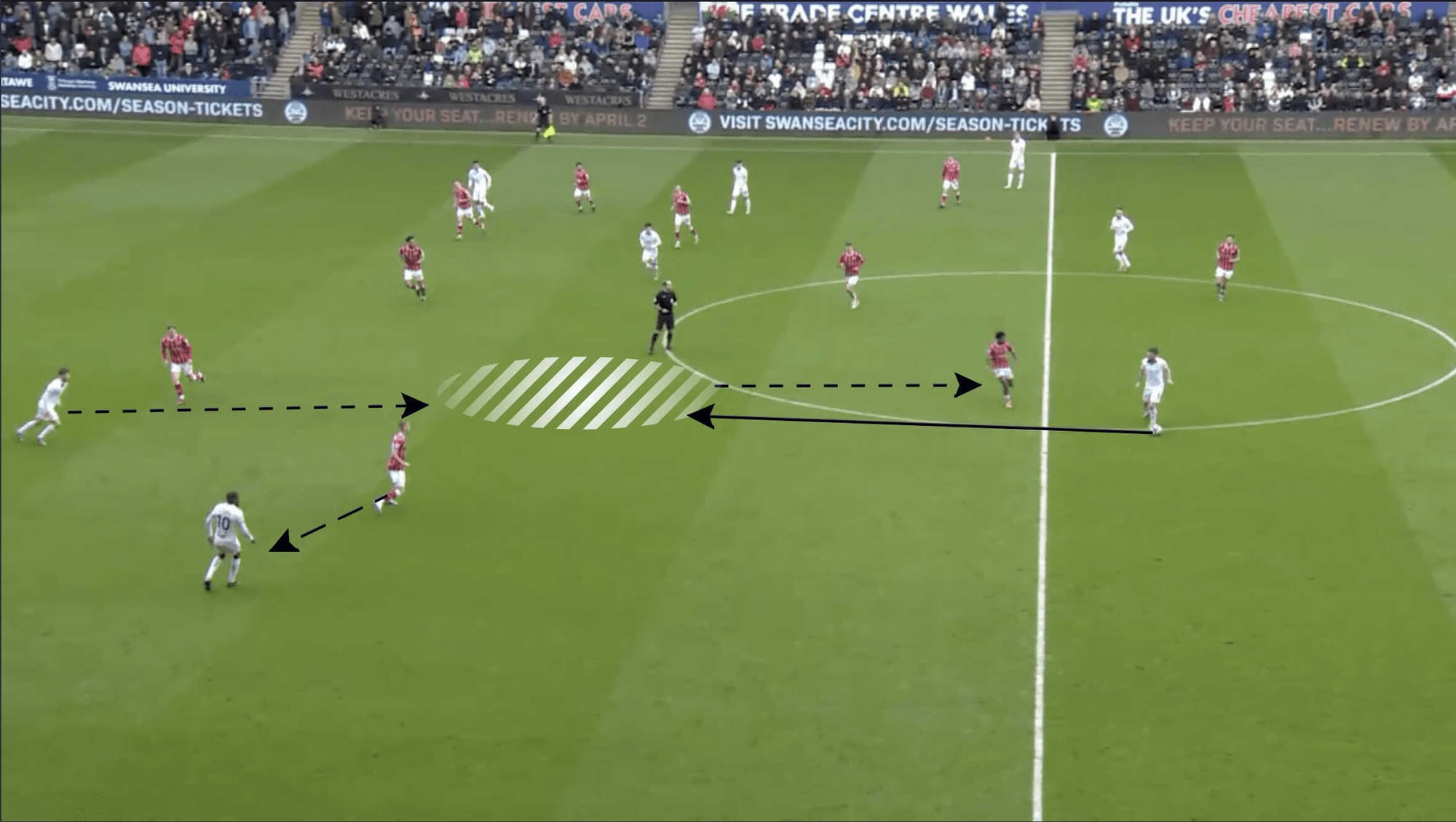

Another example of this can be seen below, with Manning once again on the ball and Grimes and Oliver Cooper, the midfielders, in more advanced positions.

From this position, Manning would play a pass to Luke Cundle which would be intercepted.

However, Grimes was in close enough proximity to reclaim the ball. From this position, Grimes would play a pass and then continue to advance forward into space with Cooper also advancing.

In contrast to the Southampton side, there is no disconnect between the midfielders and the players in more advanced areas, with the midfielders supporting the attack and playing the ball and moving into more advanced areas when the chance arises.

When in the final third, Swansea primarily look to play crosses into the box from the inside channels.

An example of this can be seen below with Manning in an inverted position playing the ball into the box.

Another example of this can be seen in the image below.

Unfortunately, Swansea at times are not able to penetrate the opposition box and create clear goal-scoring chances.

This can be seen by the fact that the side only averaged 25.81 entries into the box over the last season.

Conclusion

Southampton under the guidance of Russel Martin will truly be an exciting watch, with the side littered with talented players as well as having an experienced EFL Championship striker in Adam Armstrong.

However, at this point in time, it is unclear whether Southampton will be able to hold onto the talented members of their squad such as Kyle Walker-Peters as well as Tino Livramento.

Overallm it is likely that through some of Martin’s principles such as dynamic space occupation, minimum width as well as the staggering and distancing of the side in possession, Southampton will be able to progress the ball up the pitch on a more consistent basis.

However, there are still question marks over whether the side will be able to progress into the final third and penalty area on a consistent basis in order to create chances.

Comments