Set pieces have become an integral part of football, leading coaches, analysts, and even fans to become deeply passionate about all aspects related to them.

Fans might come across a clip showcasing a brilliant set piece execution that leaves them impressed, prompting them to share it with their friends and express their desire for their team to implement such a strategy.

At the same time, coaches and analysts are constantly learning from one another, sharing ideas and elevating each other’s set-piece game over time.

However, does the matter truly revolve solely around the idea? Is every concept feasible for your team to execute, and even if your team is capable of implementing it, can it be effectively executed against any opponent?

For fans, this may seem commonplace; however, the significant issue is that this mindset persists among some coaches and analysts who still believe that set pieces are merely an idea—preferably a new and deceptive one.

Such strategies do not succeed with the team — or only rarely succeed — leaving them to wonder about the disparity between their team’s performance and what they observe on television from sides like Arsenal or across the Premier League in general.

In this tactical analysis, we will illustrate through specific examples the differing perspectives on set-pieces from various teams worldwide, whether through case studies or principles and tactics that are trained and applied.

We will categorize teams into three levels based on their approach to set pieces, ranging from the least effective to the most effective.

We will also highlight the differences in their perspectives on set pieces, providing examples to illustrate these distinctions.

Level C

Most teams worldwide are at this level, where they implement good ideas that sometimes succeed and sometimes fail.

This happens because they don’t apply a full routine, giving every player a role and forming a game plan depending on the players’ ability and the opponent’s defending tactics.

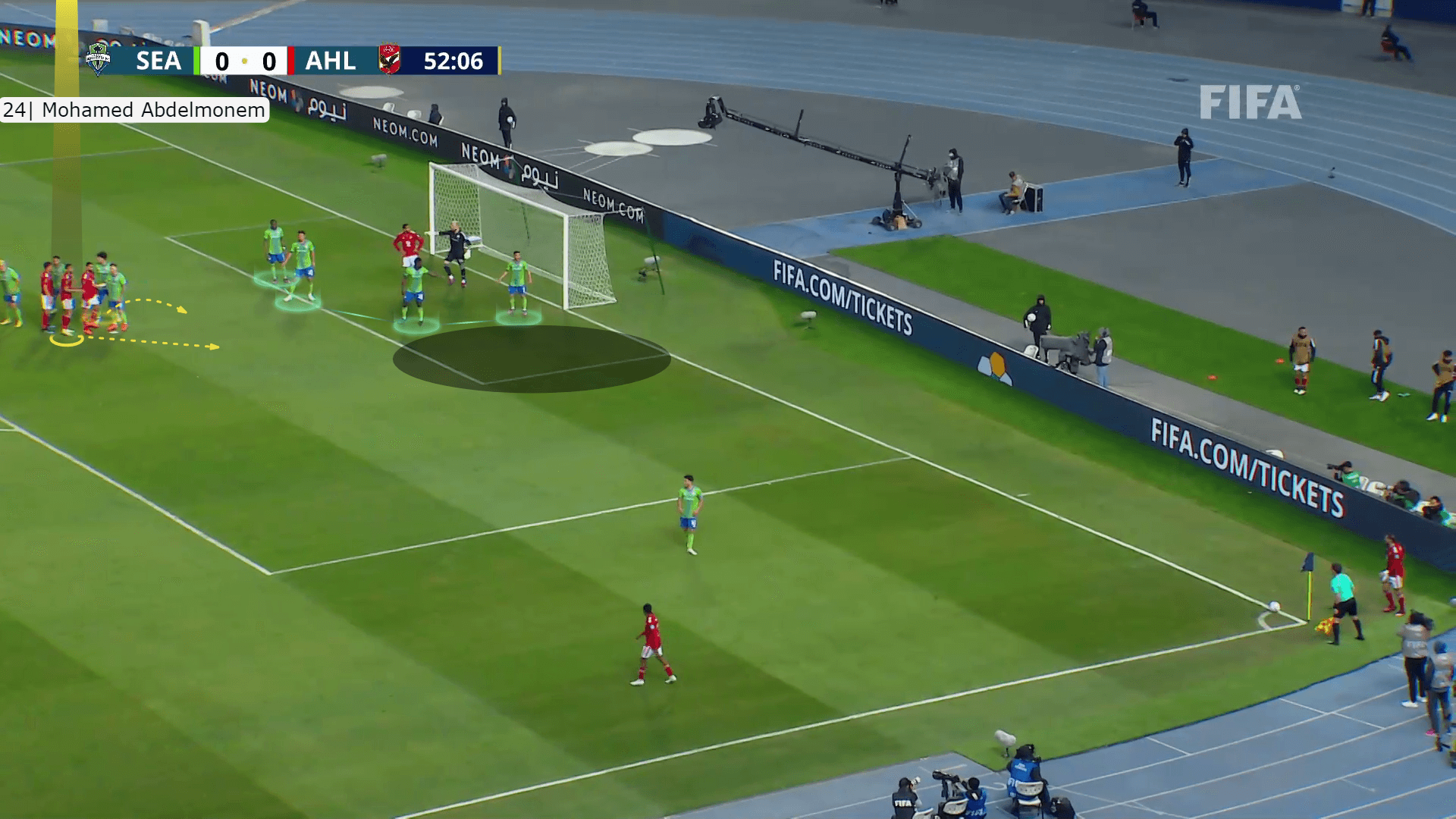

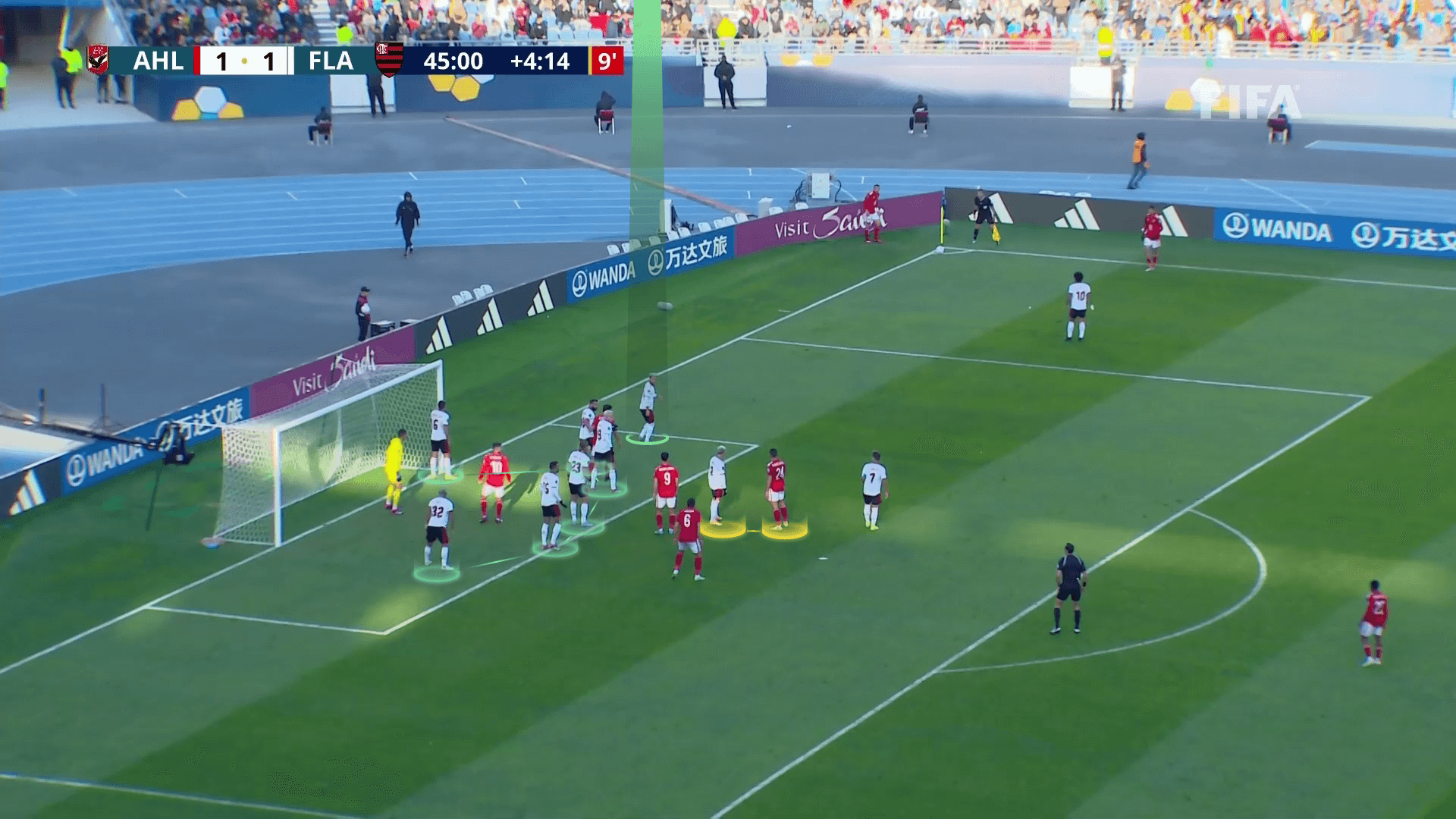

In the example below, Al Ahly have Mohamed Abdelmonem, now playing with OGC Nice in Ligue 1, who is incredibly good at heading.

He especially gets the first touch intelligently at the near post and the area ahead of it.

Then, he can flick the ball or target the goal directly.

Al Ahly depended heavily on targeting him to get the first contact in the area ahead of the near post (the black circle).

He exploited that his starting position from the middle made it harder for the first two zonal defenders to rack him while the ball was in the air, so he could come from their blind side and run all this distance, earning a dynamic advantage, too.

The second thing is that many teams leave this area empty from zonal defenders (green), asking one of the first two zonal defenders to go there to get the first touch, which makes him cut a long distance.

To free Mohamed Abdelmonem from his man marker, he stands in a three-member stack, which creates a kind of separation between him and the man marker.

Because he doesn’t know the direction he will run in, the marker waits horizontally, forcing him to take a curved, longer route to catch Mohamed Abdelmonem.

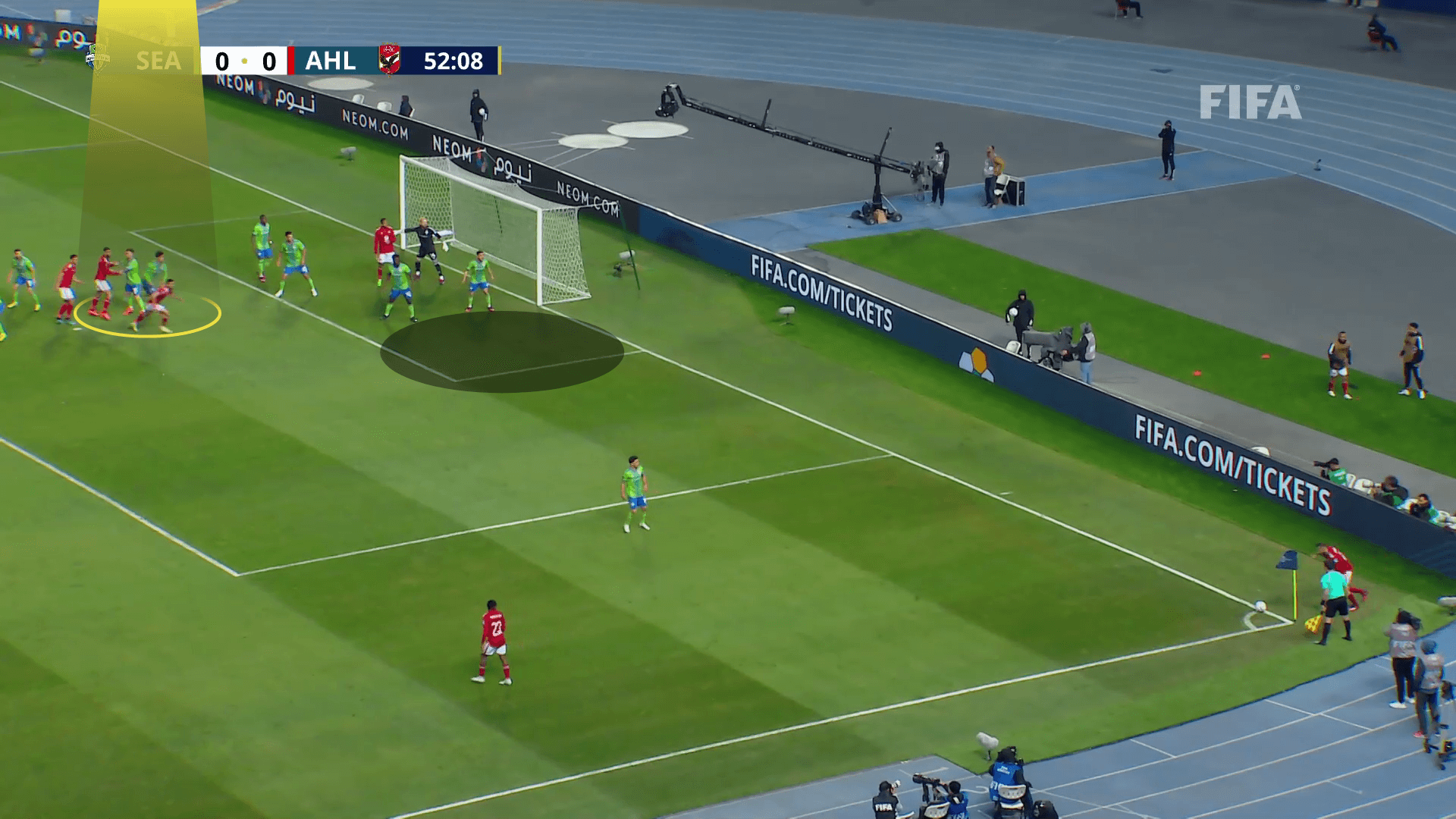

The separation is clear below, and if you make this separation for such a quick and strong player, you won’t catch him.

As shown below, Mohamed Abdelmonem could escape.

At the same time, his teammate in the stack blocks his marker, making sure that he won’t decide to go to Mohamed Abdelmonem, so he now comes from the zonal defender’s blind side, who is forced to take a long way to reach the targeted area.

The plan works while three players (circled in white) are waiting for the pass if he can’t target the ball directly, as shown below.

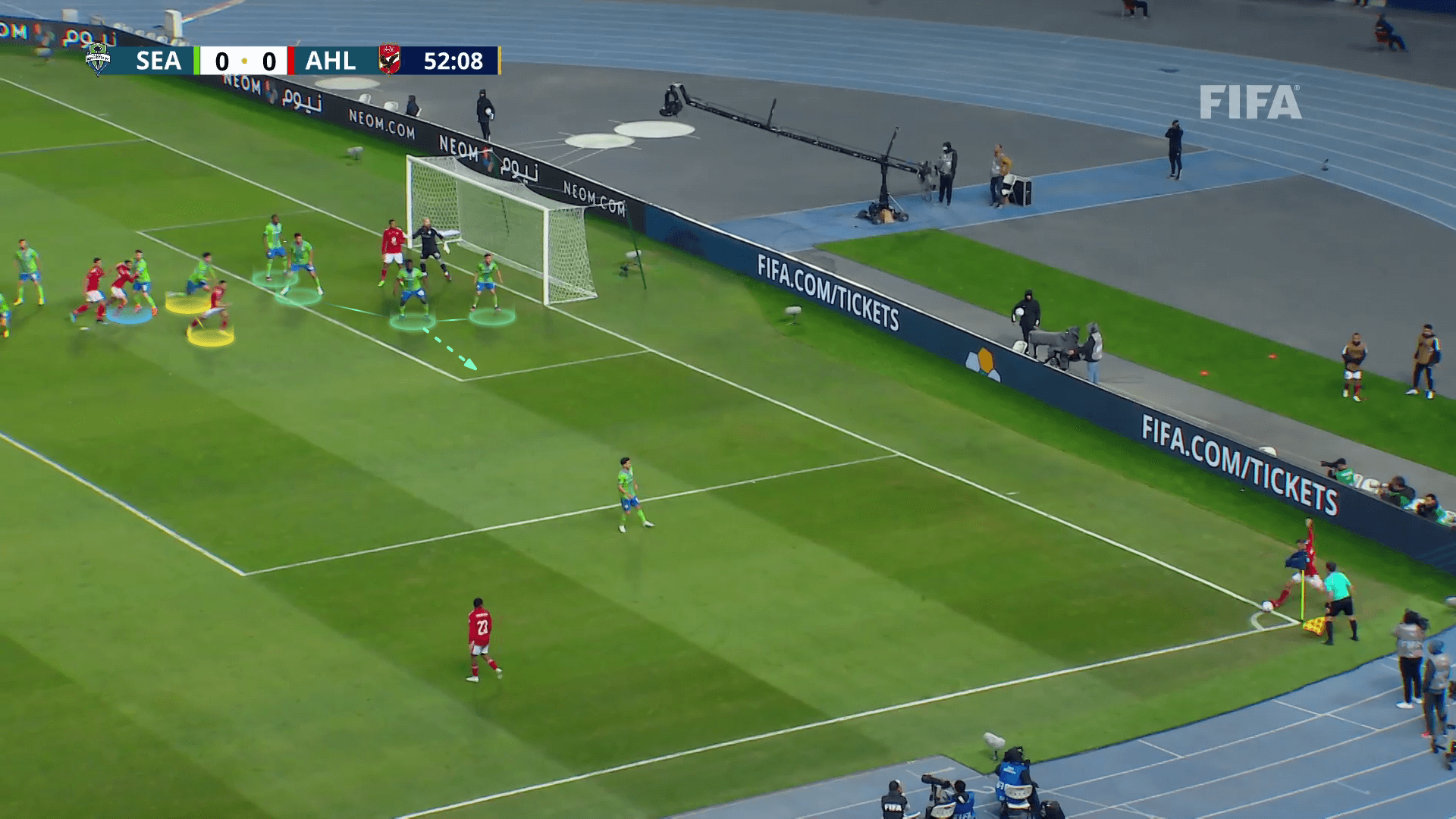

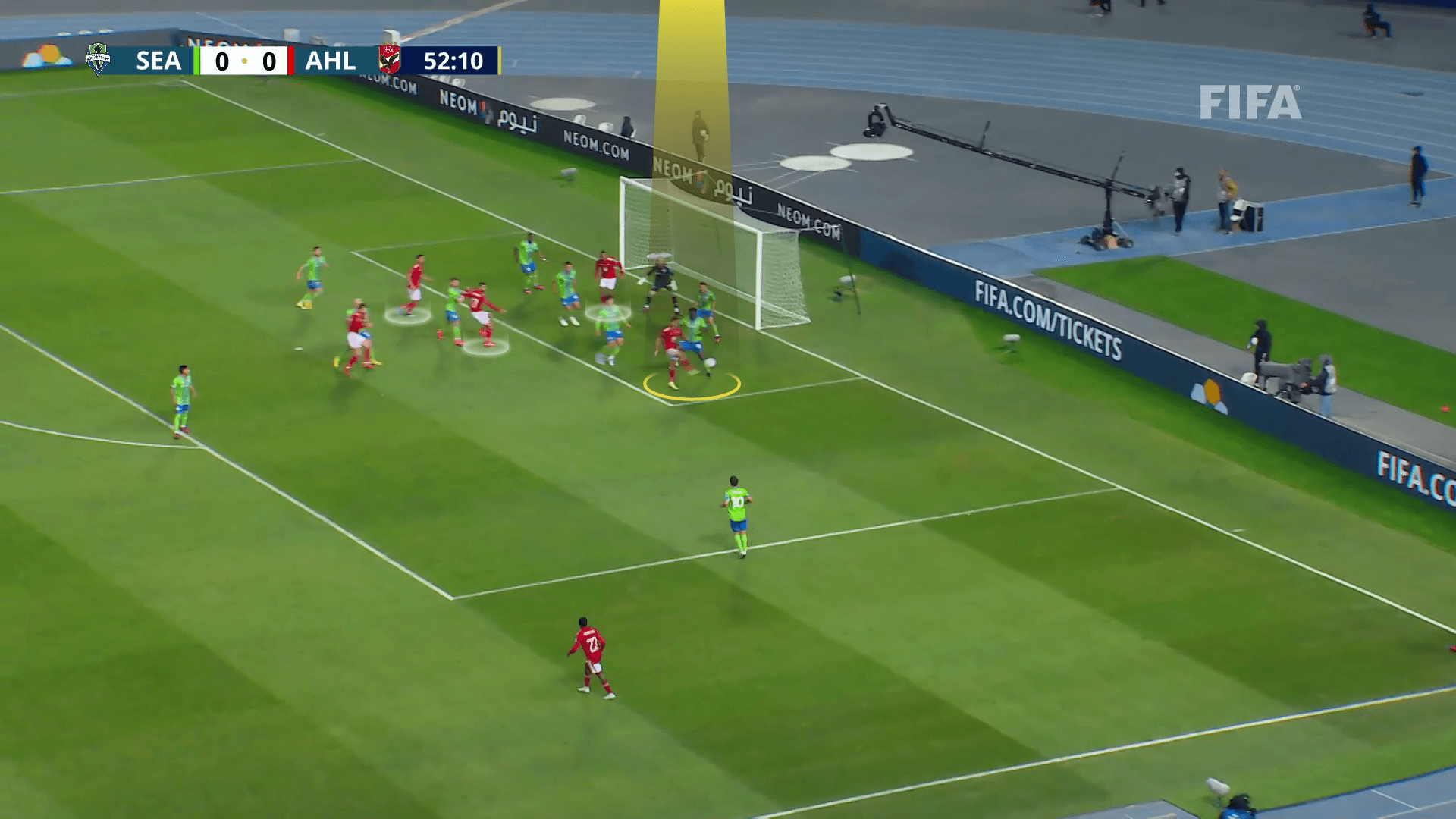

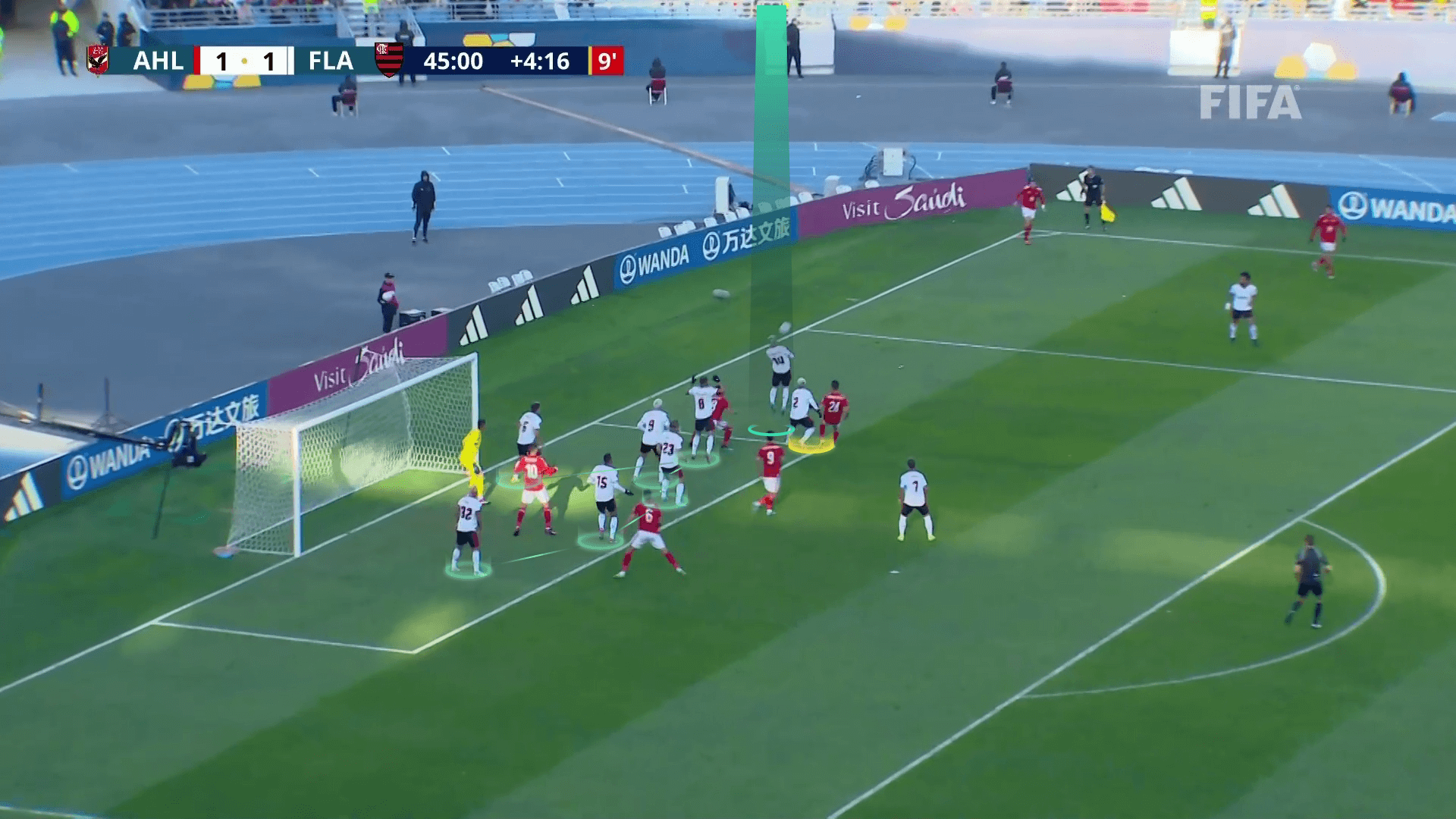

After that, they face a team that defends with seven zonal defenders (green) having the highlighted one whose usual job is to defend the usual targeted area, and you can see his body orientation waiting for anyone trying to cut into this area between the near post and the vertical line of the six-yard.

Now, you can ask about Al Ahly’s game plan against this defending scheme; the answer is that they will apply the same game plan.

In the end, Mohamed Abdelmonem brilliantly reaches his man marker, as usual.

Still, Al Ahly doesn’t take the opponent’s scheme into consideration to find a solution against this additional defender so he can easily clear the ball, as shown below.

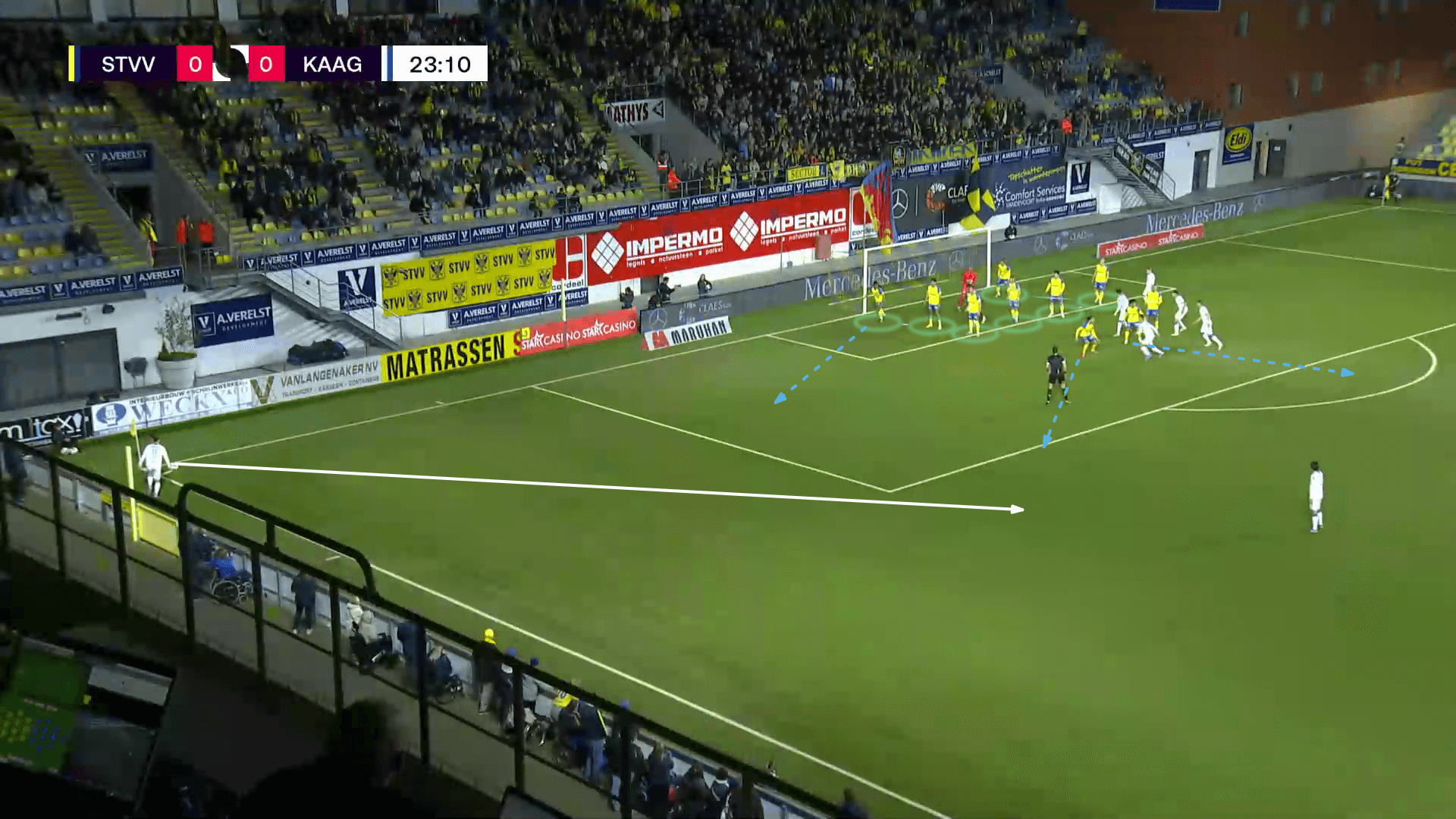

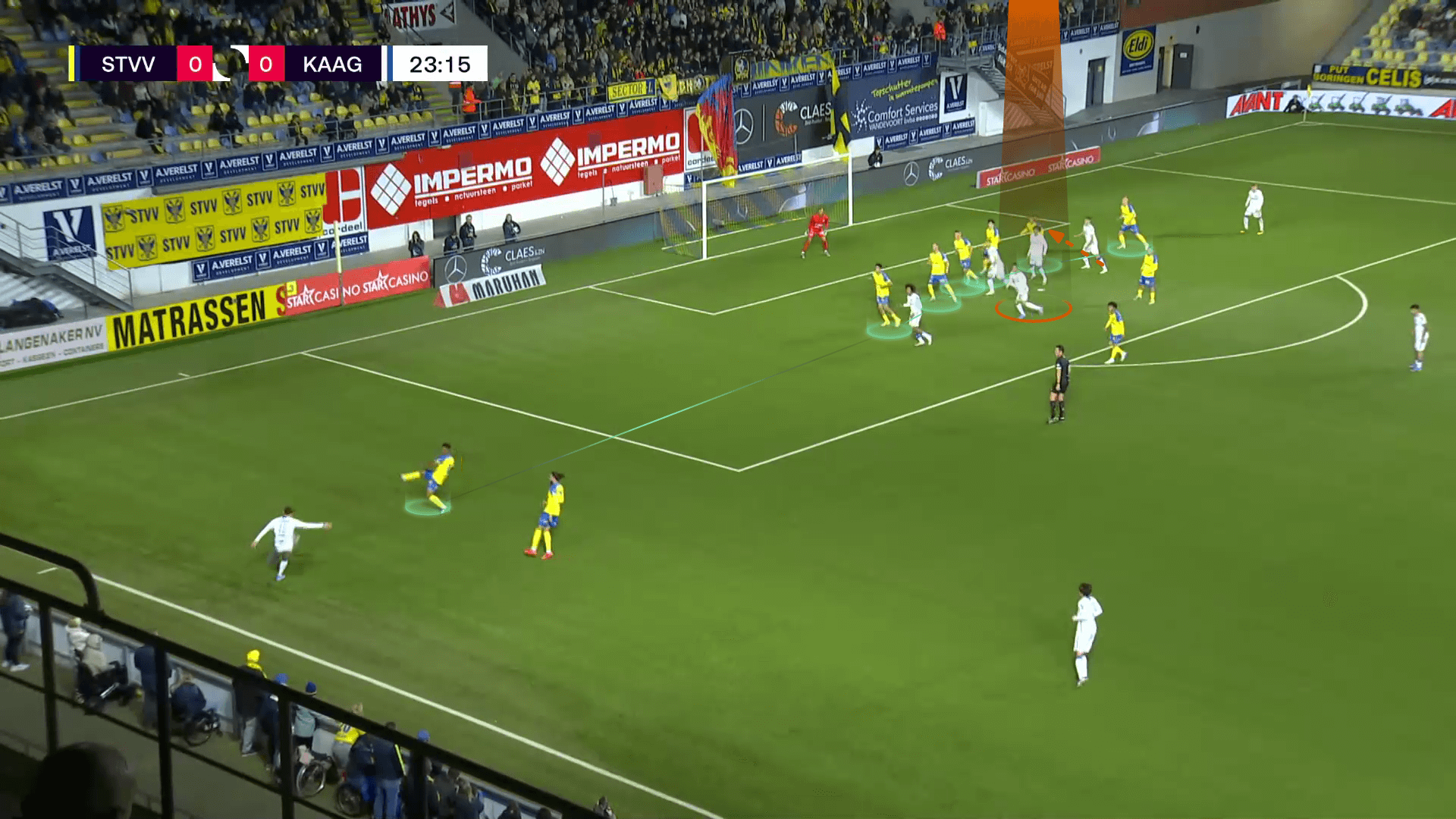

In another example from the Belgian Pro League, K.A.A. Gent have an excellent idea to implement quick short corners toward a player who comes suddenly from the back or the edge of the box with no short options in the beginning.

In their game against Sint-Truidense, they managed to implement it excellently.

In the photo below, the opponent defends with seven zonal defenders (green) and three-man markers because the edge-of-the-box defender joins the markers to help against the numerical superiority over them.

This sudden pass will force two players to go up, the first one of both the zonal defenders and the man markers, who take a long way to reach the short-option attacker who comes suddenly from the back.

Because they are two late, the short-option attacker has a great space to pass the ball to the taker again while the remaining two man markers go forward toward the edge of the box, as shown below.

The targeted player becomes free in the gap created in front of the zonal defenders, who now form a line behind the man markers, who go forward for different reasons, as mentioned.

The plan works, so the first targeted player flicks the ball toward the second one on the far post, who scores a goal.

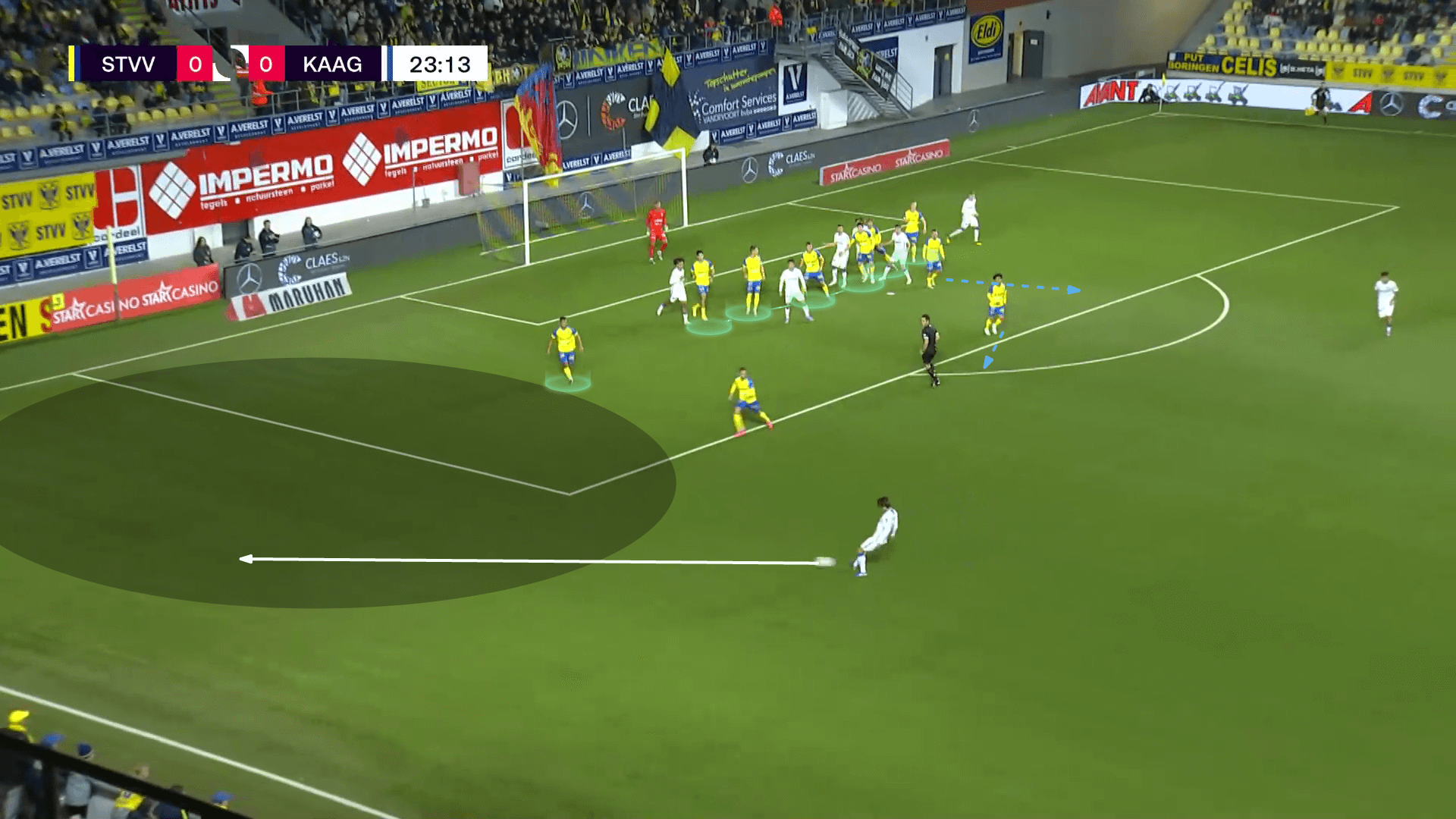

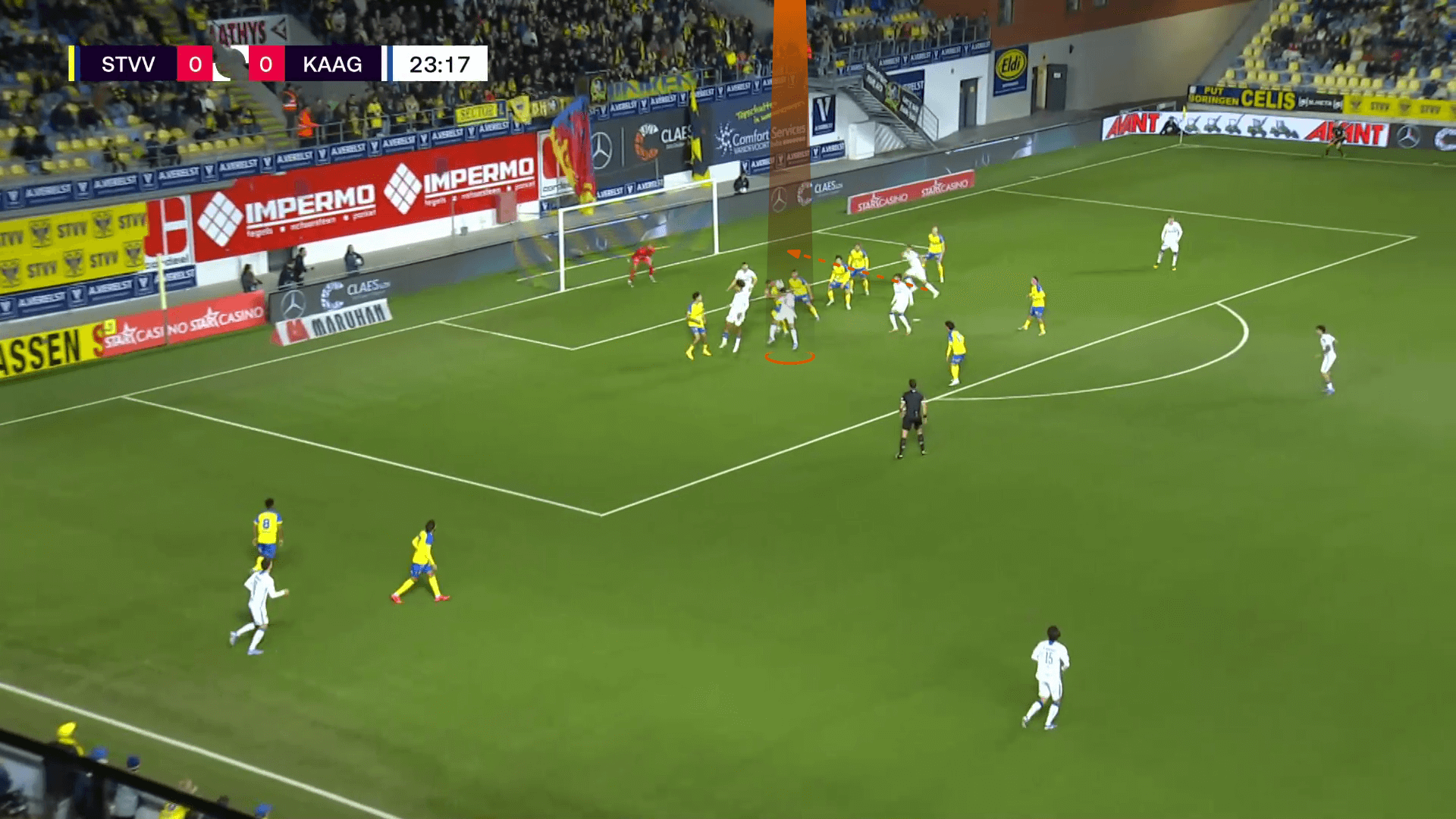

You may be impressed, but they don’t always seem brilliant, as in this case, because they also implement the same idea without considering and analysing the defending team’s reaction.

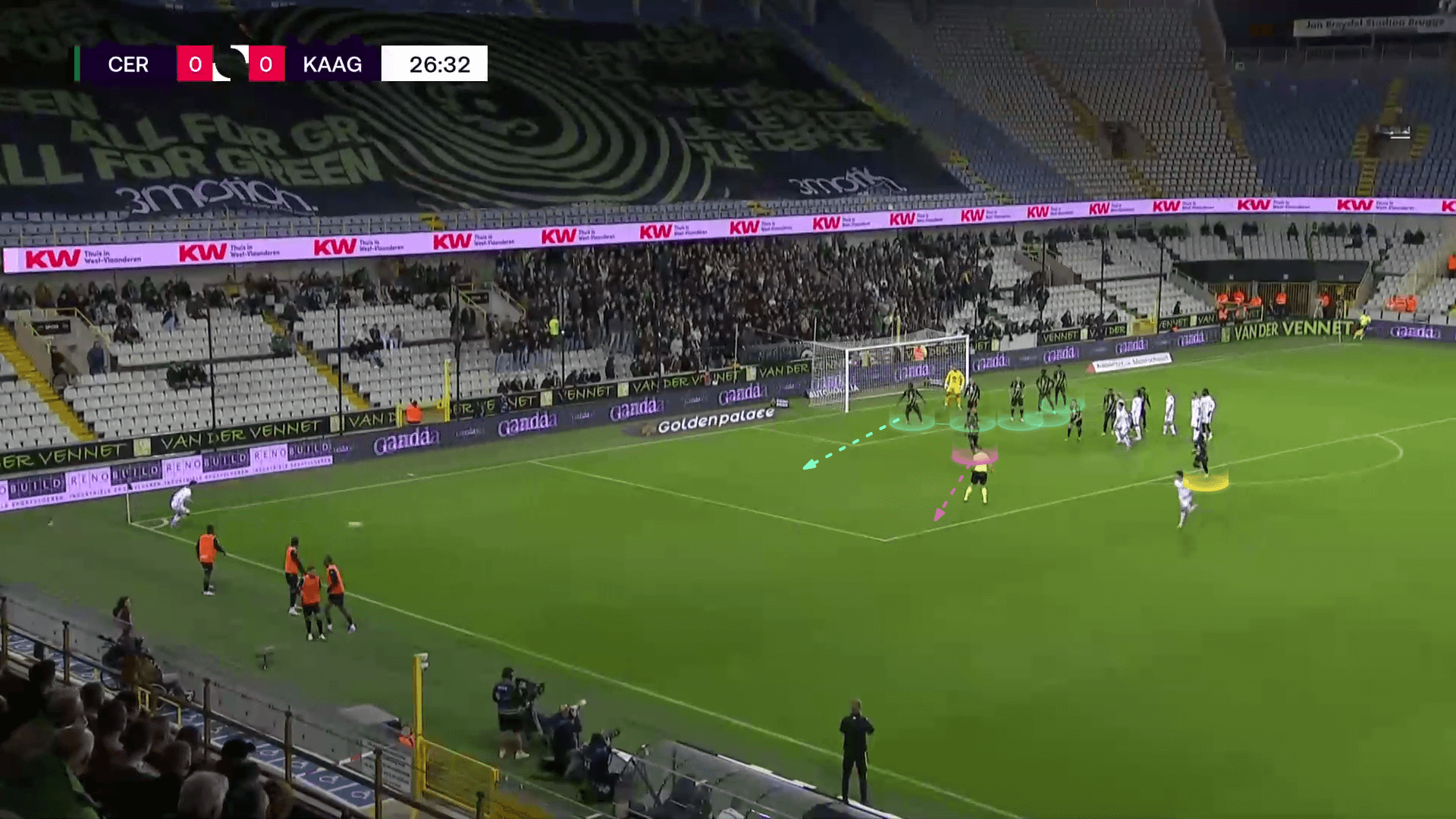

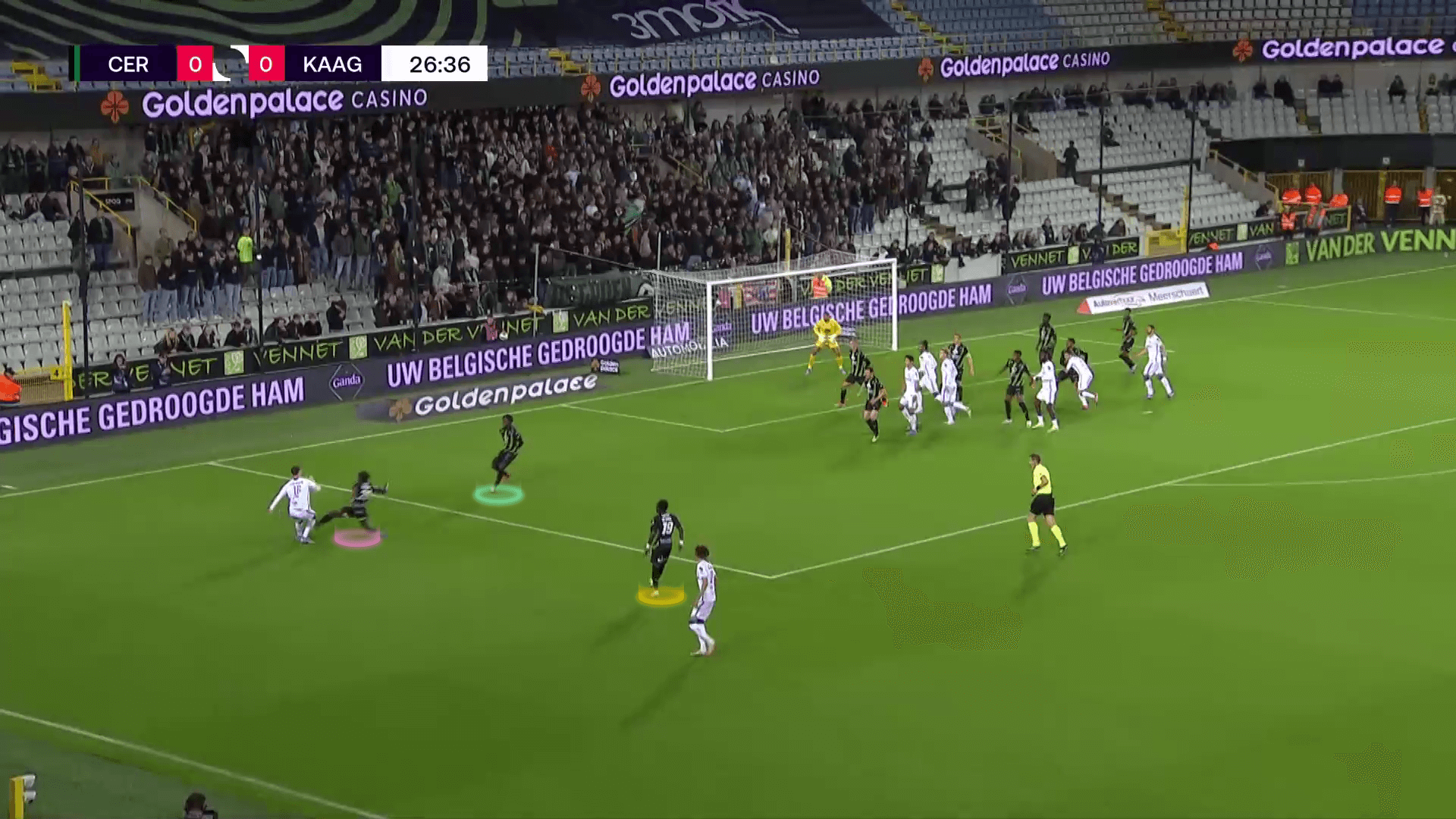

In the photo below, they try to follow a similar strategy, but Cercle Brugge defends with five zonal defenders (green), three-man markers, a short-option defender (Pink), and a standing player on the edge of the box (yellow).

In case of short corners, this team asks the short-option defender to go to the short-option attacker, followed by the first zonal defender.

The edge-of-the-box player isn’t dragged inside the box and is ready to run with this attacker, who suddenly moves horizontally toward the taker.

In the end, the plan fails because, as shown below, the taker doesn’t have the same space and time as in the previous case.

So, if you analyse the opponent’s dynamic reaction, you are supposed not to make that mistake.

Level B

At this level, excellent teams appear by forming an entire routine by informing the 10 players about everyone’s role and how, why and when everyone implements it according to their abilities and the defending tactics of the opponents by analysing them.

Aston Villa may be the best team at this level with their set-piece coach, the brilliant Austin MacPhee.

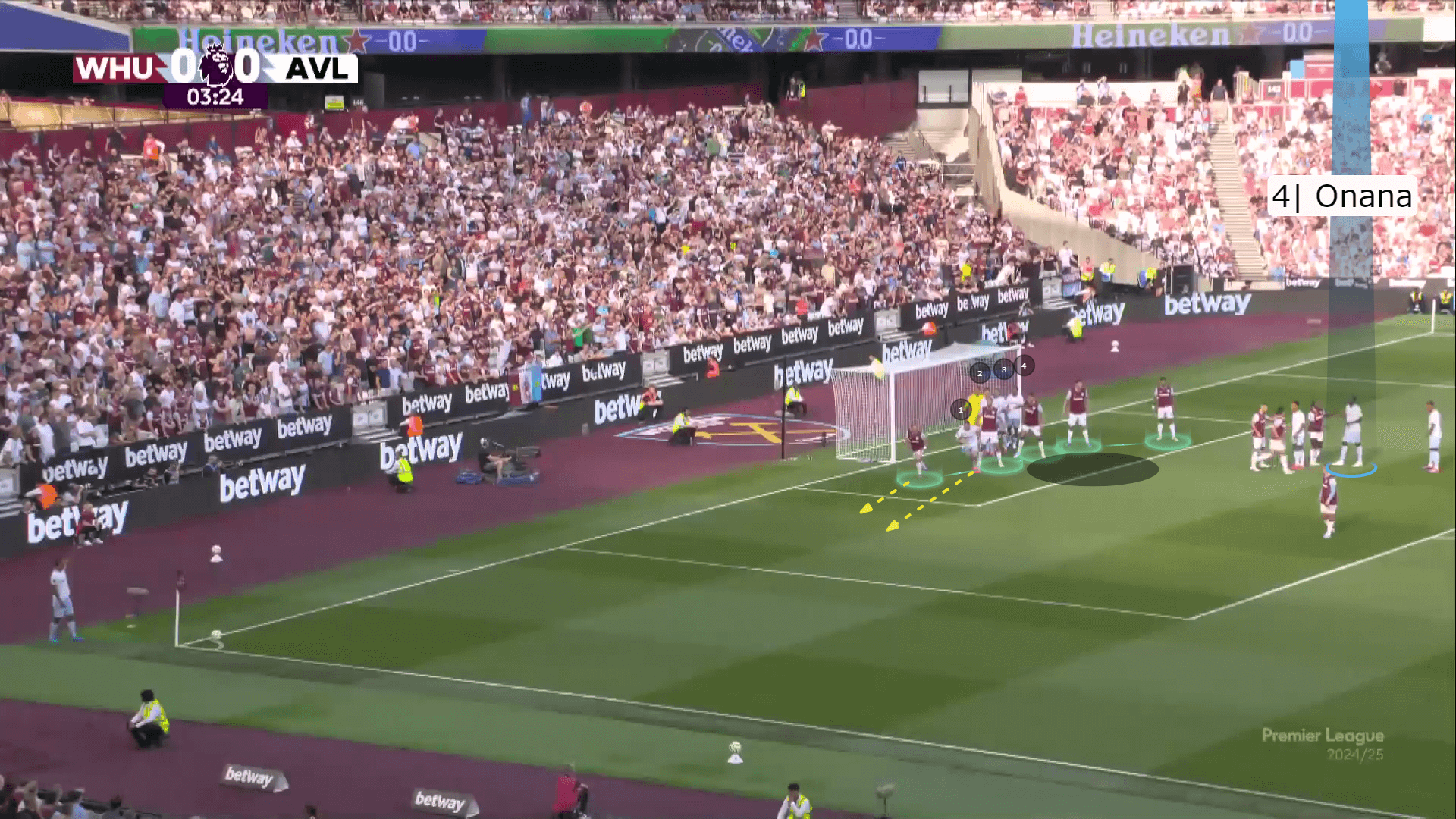

In the photo below, Unai Emery’s side faces West Ham United, which defends with five zonal defenders (green), three-man markers, a short-option defender, and a player on the edge of the box (out of the shot).

They want to target the middle area of the six-yard box by Amadou Onana, so they start to think by logic, finding the obstacles of the opponent’s scheme and then trying to find a solution by giving the ten players specific roles in a full routine.

The obstacles are the crowded zonal defenders, the goalkeeper who can go forward to claim the ball, and Onana’s man marker.

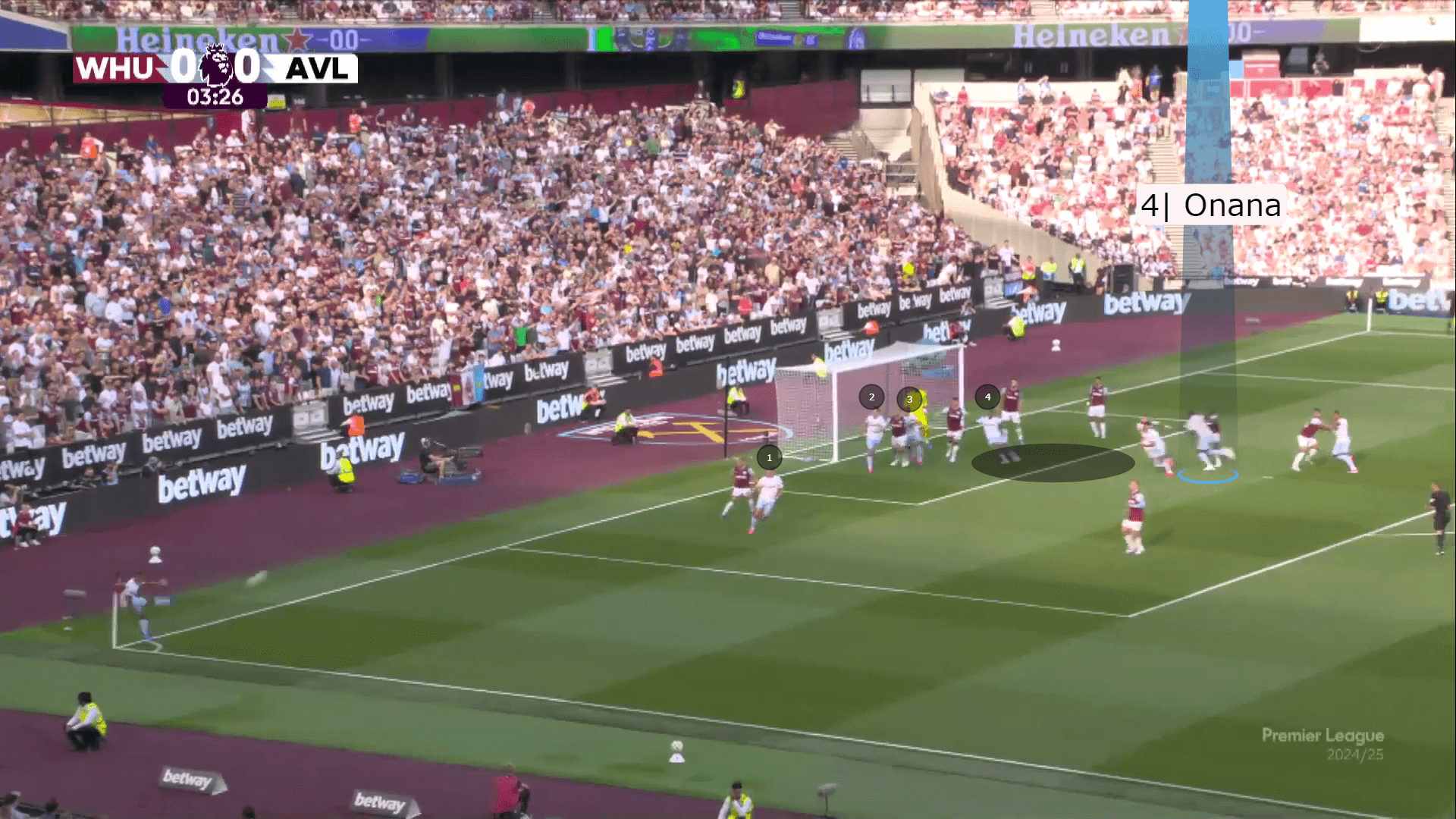

First of all, they depend on Amadou Onana’s physical ability to overcome his marker, which is known as a “mismatch”, and he also starts in a little far area to force his marker to give his back to the ball, making it difficult for him to keep tracking him and the ball at the same time, so he will be forced to turn around to follow him, as we will see later,

To deal with the first two obstacles, four players (numbered) start in front of the goalkeeper to distract his attention, limit his ability to move and be worried about them, so he won’t have time to think about going to claim the ball.

The second important thing regarding this traffic in this starting position is that the zonal line is forced to shift more inside, not leaving a huge space between the line and the goalkeeper, having four players in this space.

This leads to a good shift vertically to help in targeting this area.

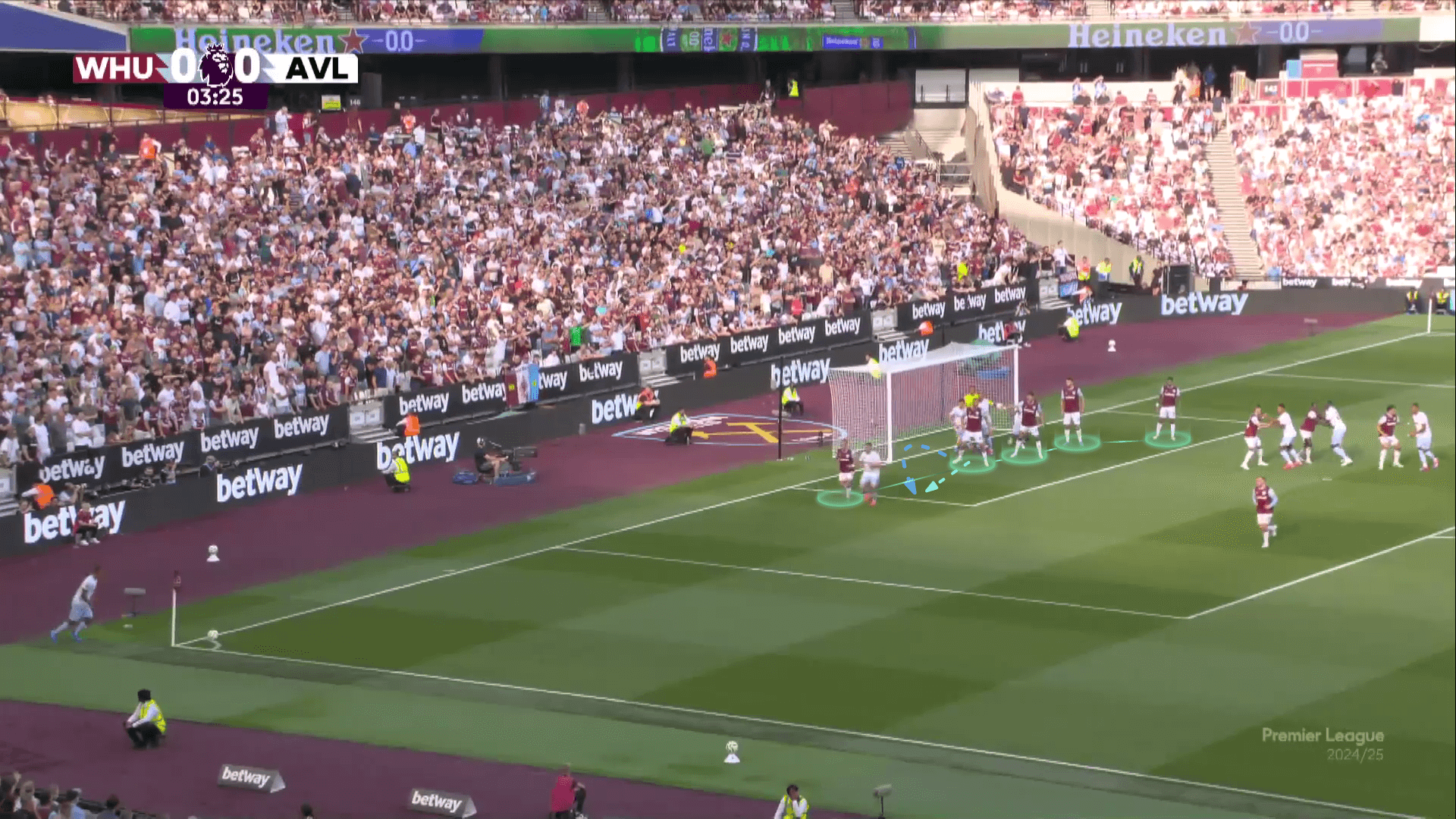

Horizontally, these four players will move in different ways to create a horizontal gap, so the first player goes forward in a decoy run to drag the first zonal defender.

The second and third attackers will do a sandwich for the second zonal defender, one runs pretending that he wants to exploit the created gap while the other runs behind the defender sticking to his back to prevent any trial of stepping back again.

The fourth player turns around the third zonal defender at the right moment to block him from his blind side.

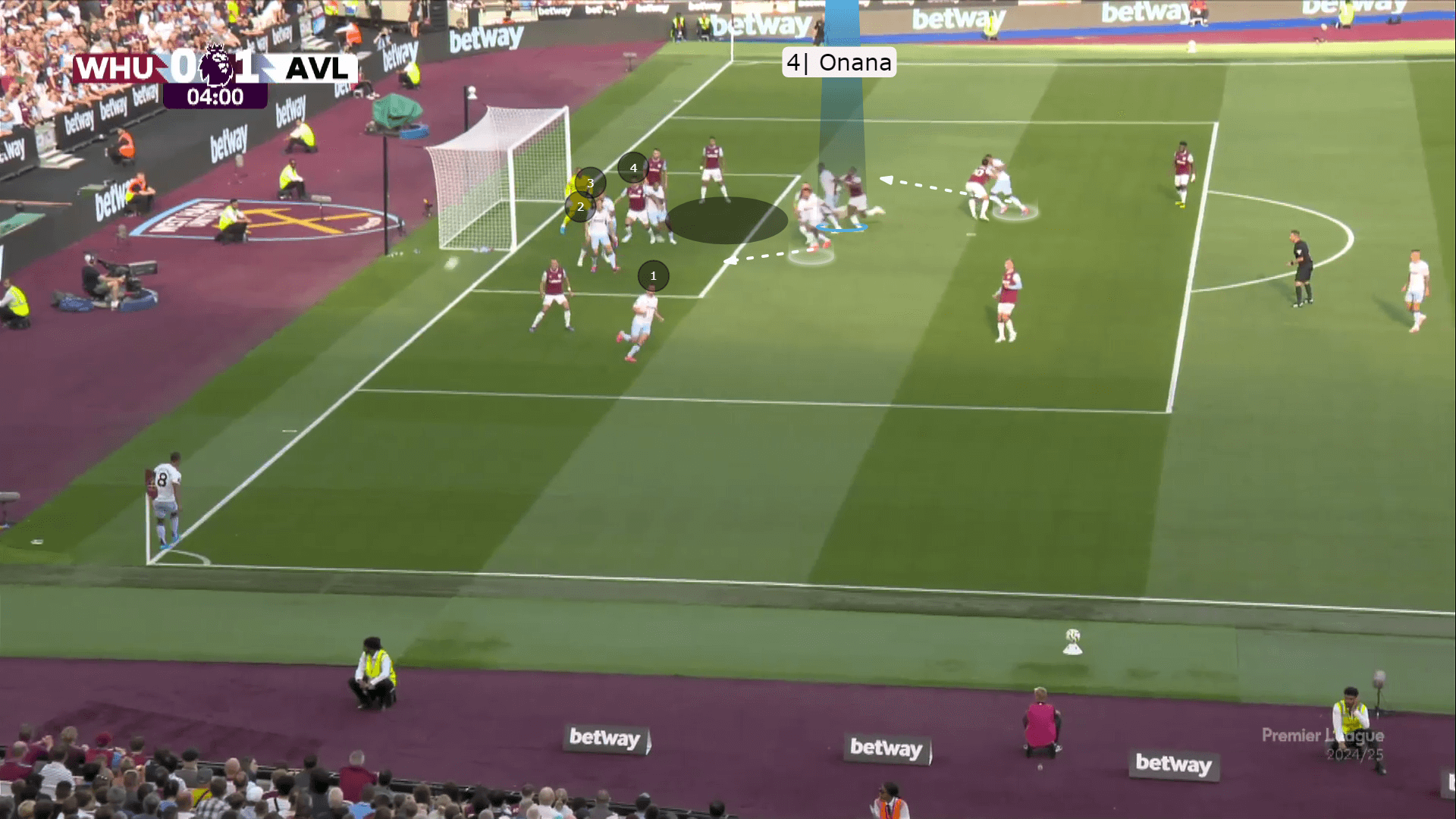

The space is now free for Onana while the two other runners run to the near and the far post to be ready if the cross is underhit or overhit and to follow the rebound ball from the goalkeeper if he saves the ball.

The plan works brilliantly, and the result is a goal.

Level A

Despite the excellent routine, you can ask why the previous case isn’t at level A.

We agreed that each player has a specific role and understands when, how, and why to execute it after a tactical analysis of our capabilities and the opponent’s defensive tactics, resulting in a cohesive and comprehensive routine.

However, teams in this classification, notably Arsenal, have demonstrated that approaching each match with totally different routines is not the optimal solution and then changing them in the next match.

Instead, they prefer that all their routines emerge from the same underlying principles.

You might consistently observe Arsenal in every goal or opportunity from a corner and feel that they are all based on the same base, experiencing a unified spirit in each set piece.

This is what we mean: all their routines stem from several core concepts, making them easier to explain, understand, and ultimately apply.

You may still find the discussion about the principles applied in set pieces somewhat vague, but it will become much clearer after we present the following example from the last match before the season began.

This will demonstrate how training players on these simple principles during pre-season leads to excellent results.

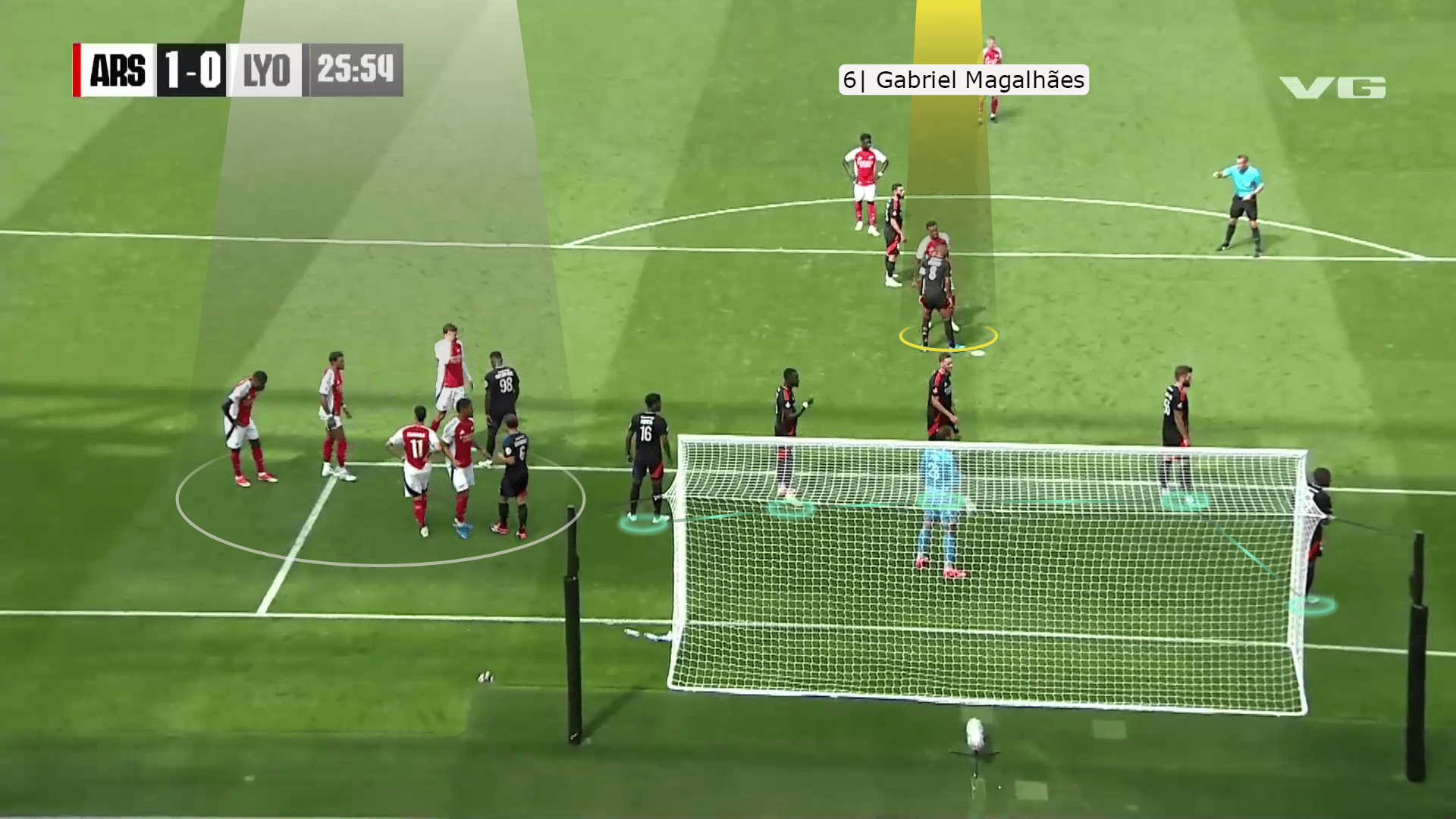

In the photo below, you can know that they are Arsenal even if we hide the colour of the shirts because of this famous pack beyond the far post, but what is the benefit?

Standing like this puts your players on the zonal defenders’ blind side (green), which causes them an orientation problem because they can’t track the attackers and the ball at the same time and don’t know what is happening behind them.

The same orientation problem appears when you see the two-man markers inside the spot because they are also against this choice of tracking the ball or the attacker, so they turn their backs to the ball, losing contact with it.

The second common thing is Gabriel Magalhães‘s starting position (the targeted player) near the penalty spot; in this case, he will target the far post.

Continuing with this five-player pack, you can find many common roles, with some changes in the individuals:

1- William Saliba (baby blue) goes to block the goalkeeper from his blind side as he is busy with the taker’s movement.

2- Two pink blocks (Thomas Partey and Ben White) are very easy because they come from the blind side, just pushing the defenders from their backs to prevent them from stepping back toward the targeted area

3- Gabriel Martinelli (green) stands in green to be ready if the ball passes Gabriel Magalhães (yellow).

At the same time, Kai Havertz (white) drags his marker away from the targeted area and then stands on the near post in case Gabriel can’t play it directly or the goalkeeper saves the ball to be ready for the rebound.

These two actions are a part of an important principle, which is framing the goal.

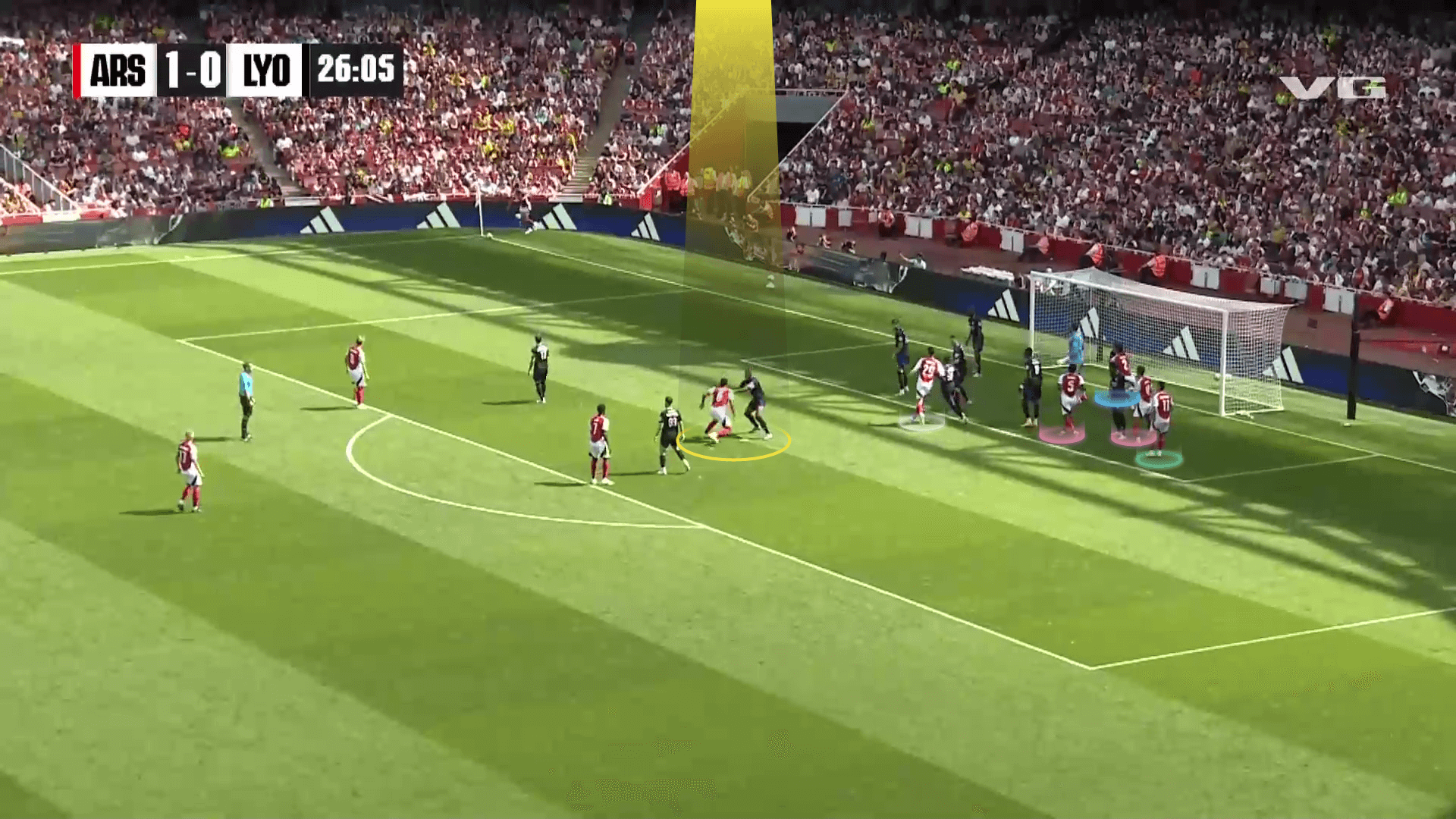

Going to Gabriel Magalhães, he starts at this position to fake a feint to the near post, then goes to the far post.

As shown below, this trick forces the marker to decide whether he will track the ball or Gabriel Magalhães and here, he chooses Gabriel, giving his back to the goal, and he will need to have a look at some point, which reduces his ability to track Gabriel who knows the plan running without hesitation and also has clear ability in 1v1 situations.

This is another use of the same orientation problem

Another principle is also applied by this starting position near the penalty spot, which is the dynamic mismatch.

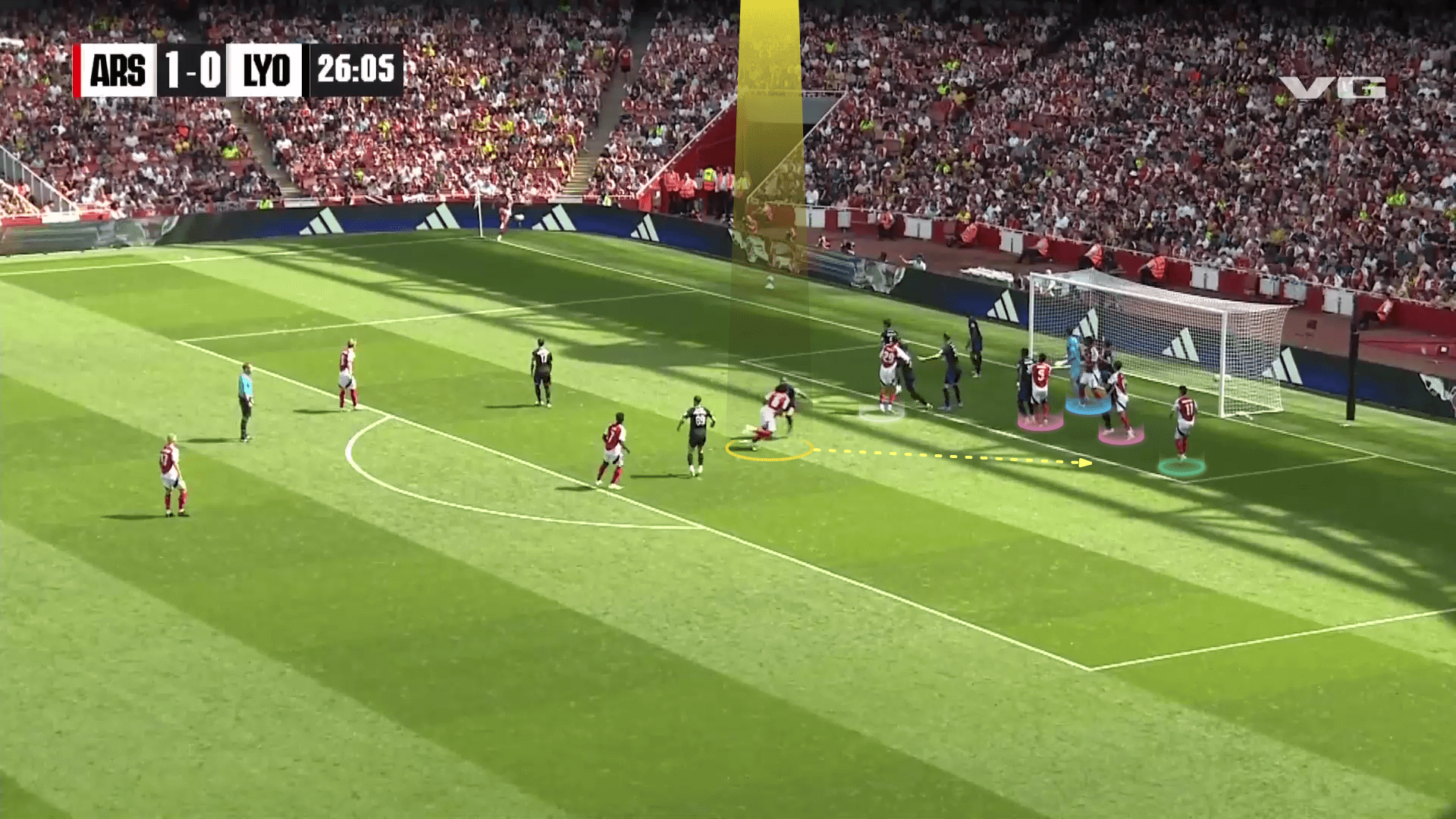

Running all that distance toward the zonal line gives him great momentum against the stationary zonal defenders, allowing him to jump much higher, and he is also excellent at that.

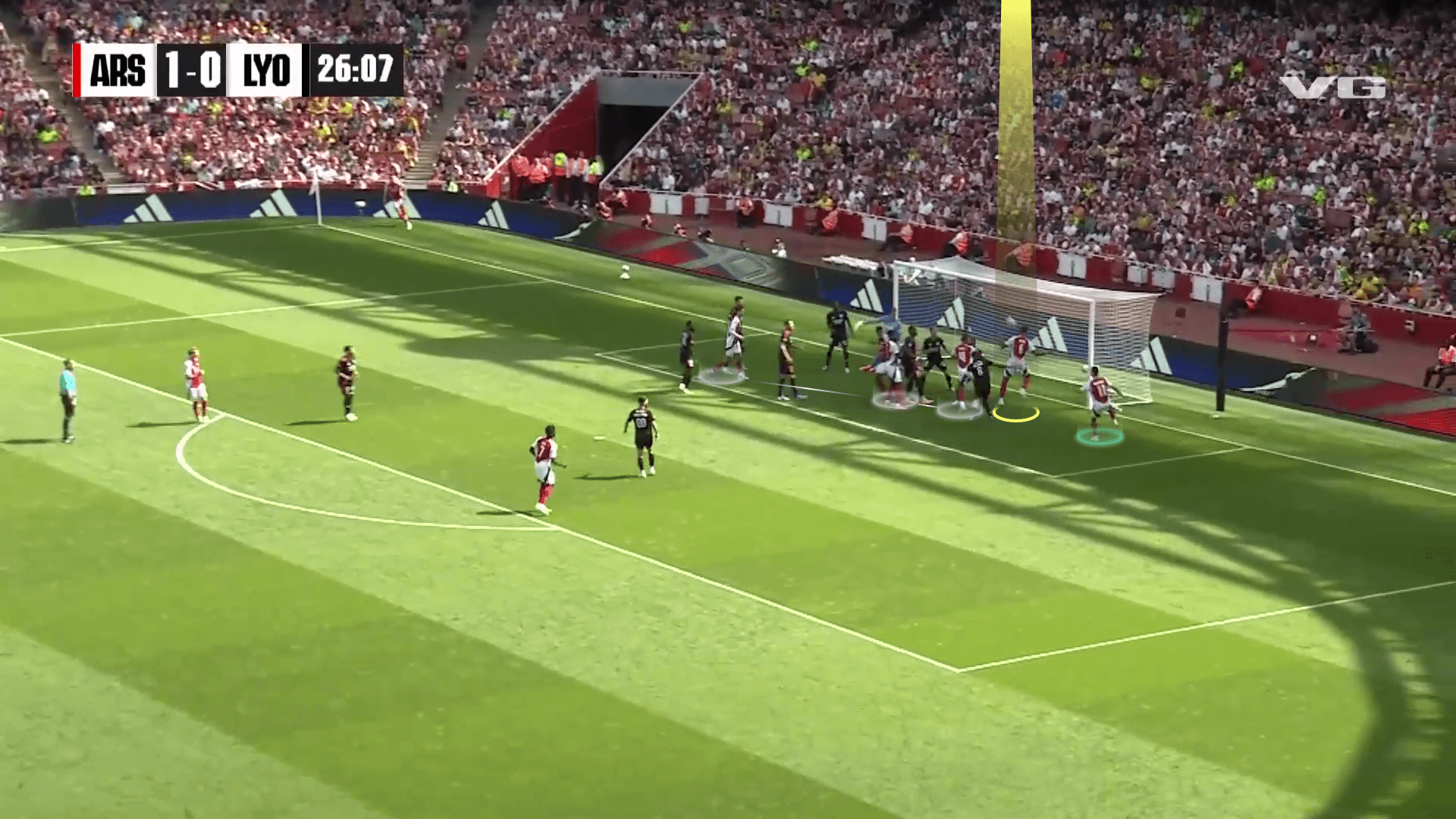

In the photo below, the dynamic advantage is clear in his great jump from movement, resulting in a goal.

The framing of the goal is also clear: Martinelli waits for the ball in case it passes Gabriel while the four remaining attackers stand horizontally in the six-yard.

Framing the goal by standing in valuable areas in the six-yard on the near, middle and far post increases your luck in getting the ball. If it passes the targeted player, he can’t play it well, or the goalkeeper saves the ball.

People would say they were lucky, as happened in the winning third goal against Leicester City, but Leandro Trossard‘s framing of the ball trajectory was the key factor, as Arsenal always do.

After explaining this case, you can apply all these principles to their goals this season.

For instance, you might recall their goal against Manchester City and feel it embodies the same principles.

This is very beneficial for the players, as it facilitates understanding and application, especially given the high number of corners or substitutions during matches.

Substitutes can easily grasp the routines because they understand the overarching principles that guide them.

It is also important to note that while the execution of these routines is extremely straightforward for your players, it can be very difficult for the opponent to predict.

A single minor change or switch of roles can lead to a completely different routine that the opponent struggles to counter.

Arsenal players handle this fluidly, which illustrates our point that all their routines emerge from similar principles that have been practised even for targeting the far or the near post.

Conclusion

In this analysis, we have explained the different set-piece perspectives that teams around the world hold and how this influences the quality and consistency of their execution.

In this set-piece analysis, we have outlined three distinct classifications, from our perspective, regarding how teams approach set pieces.

We have noted that most teams around the world still operate on the principle of ‘the idea,’ repeating it without considering variable factors such as the opponent.

In contrast, elite teams ensure that each of the ten outfield players understands his role, including when, how, and why to execute it in a full routine.

Furthermore, we highlighted that top-tier teams derive their routines from the same principles, which are easy to train, understand and apply.

Comments