How To Defend Corner Kicks

It is known that there are three methods of defending corner kicks:

- The man-marking system: This method relies on marking players individually, with only one or more players designated as zonal defenders.

- The zonal-marking system: This method relies entirely on defending specific zones. Each player stands in a designated area, awaiting the ball to strike if it enters his zone.

- The hybrid system: Currently predominant, this method involves a combination of zonal defenders and man markers to cover different areas and players effectively.

Defending zonally, even in open phases, requires some shifting when one defender moves outside of his position.

This affects all the positions of the others who try to adjust their positions due to the new situation according to a mutual reference between them.

The same thing happens in set-pieces, especially in the third kind, when a zonal defender is forced to leave his position due to certain situations.

Shifting is undesired in the zonal line during corners because if it isn’t done perfectly, it would be a problem, but sometimes it is a must.

In this tactical analysis, we will show the needed shiftings in cases where teams depend on many zonal defenders and in cases where teams use fewer zonal defenders.

We will also show that using more players in the zonal line reduces the need to shift, especially through the goalmouth, and vice versa.

More Zonal Defenders

Using more zonal defenders in the first zonal line makes everyone’s assigned area smaller, which reduces the need to shift through the goalmouth.

However, this may be needed before the near post or after the far post.

The problem is that every team wants to cover all of the six-yard with his zonal defenders, but that is nearly impossible because you may need more than 10 players in that without the short-option defender, the rebound defender and the man markers.

Hence, they rely only on covering the goalmouth.

Naturally, that leads to someone’s leaving to chase the ball if it lands in the flick area, before the near post, or after the far post.

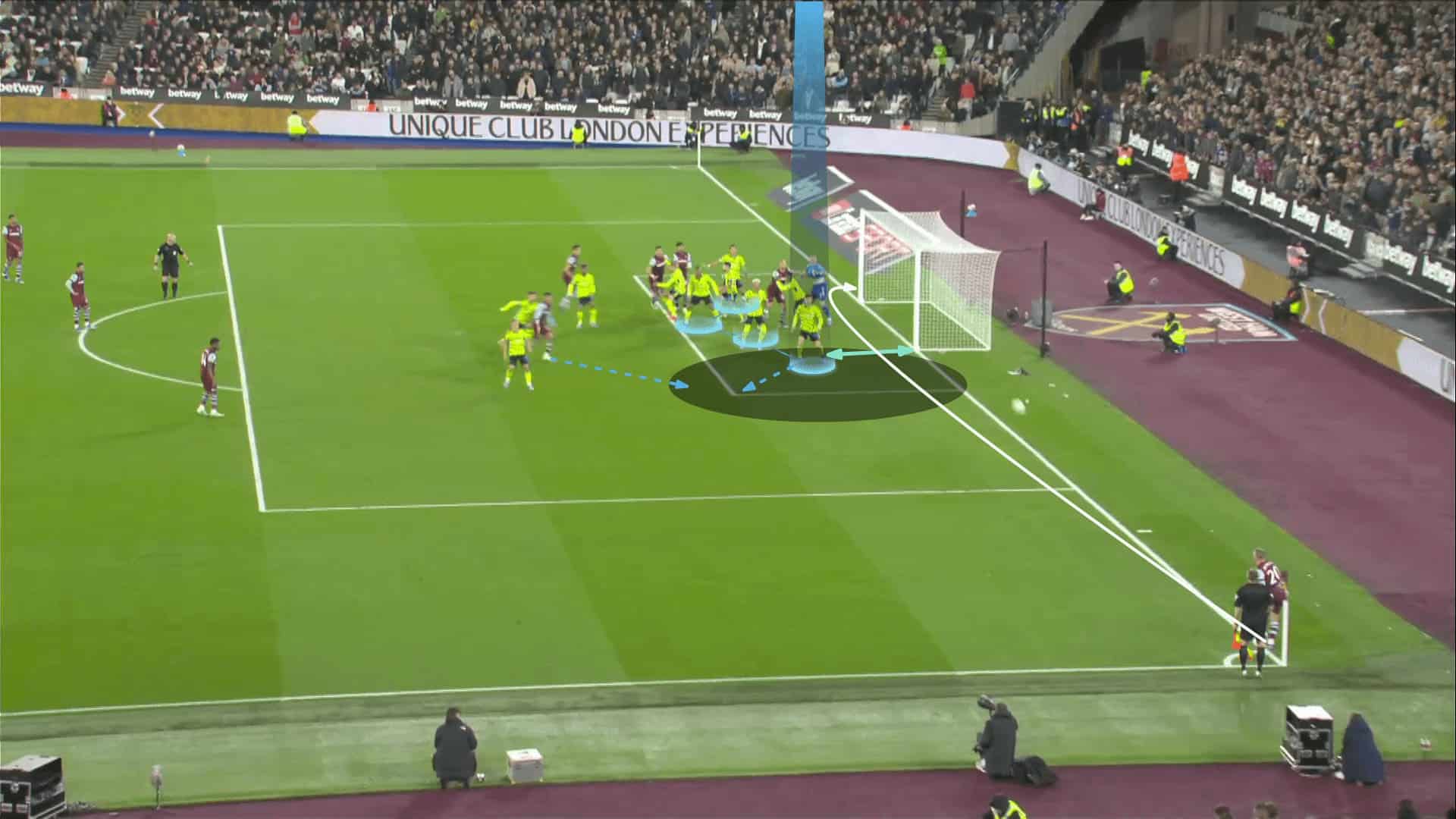

Let’s take Liverpool last season as an example.

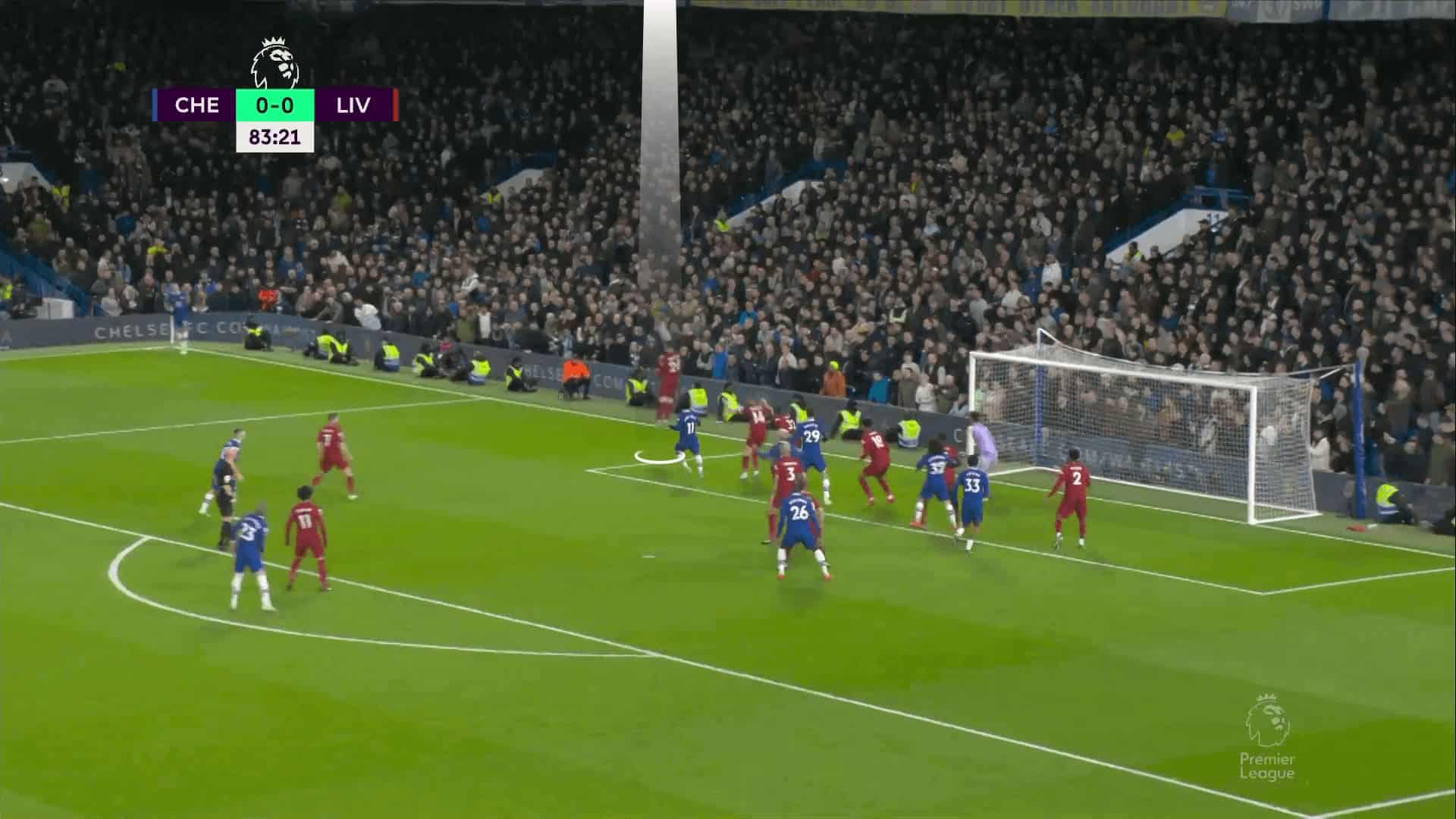

As shown below, they use a hybrid defending system with six zonal defenders, two man markers and a short-option defender who starts more inside the box, closing the direct grounded pass toward the penalty spot in case there is no short-option attackers near the taker and a player standing on the edge of the box for the rebound and maybe counterattacks.

The six-yard is crowded with zonal defenders, so you can predict that they don’t need shifting through the goalmouth.

Let’s start with the role of the first zonal defender, usually Andrew Robertson.

His role is to anticipate the cross while scanning around him, as in the photo below, to chase the ball, getting the first touch.

So you can see him standing in front of the other five zonal defenders, always checking his shoulders to defend the area in front of him to get the first touch, which could be a direct, headed shot or a flick.

This rule keeps the zonal line organised, giving Robertson orders to move while preventing the shifting in the goalmouth, which is still protected.

As shown below, he perfectly got the first touch with a good jump, scanning around him and, of course, measuring the point at which he could get the ball.

That is an important heading ability that fans may not know.

The strength of Liverpool is that they can anticipate any possible gap in their gaps, finding solutions for them before their opponents do, so you can find them having an answer to many difficult questions.

The first one is who will cover behind the first zonal defender when he goes forward to chase the first touch, filling the gap between him and the remaining five zonal defenders?

That one is the zonal defender who stands initially on the near post.

He will start as usual to defend the direct shot or cross towards this dangerous area on the near post, but after that, he will cover behind the first zonal defender when he sees the ball path.

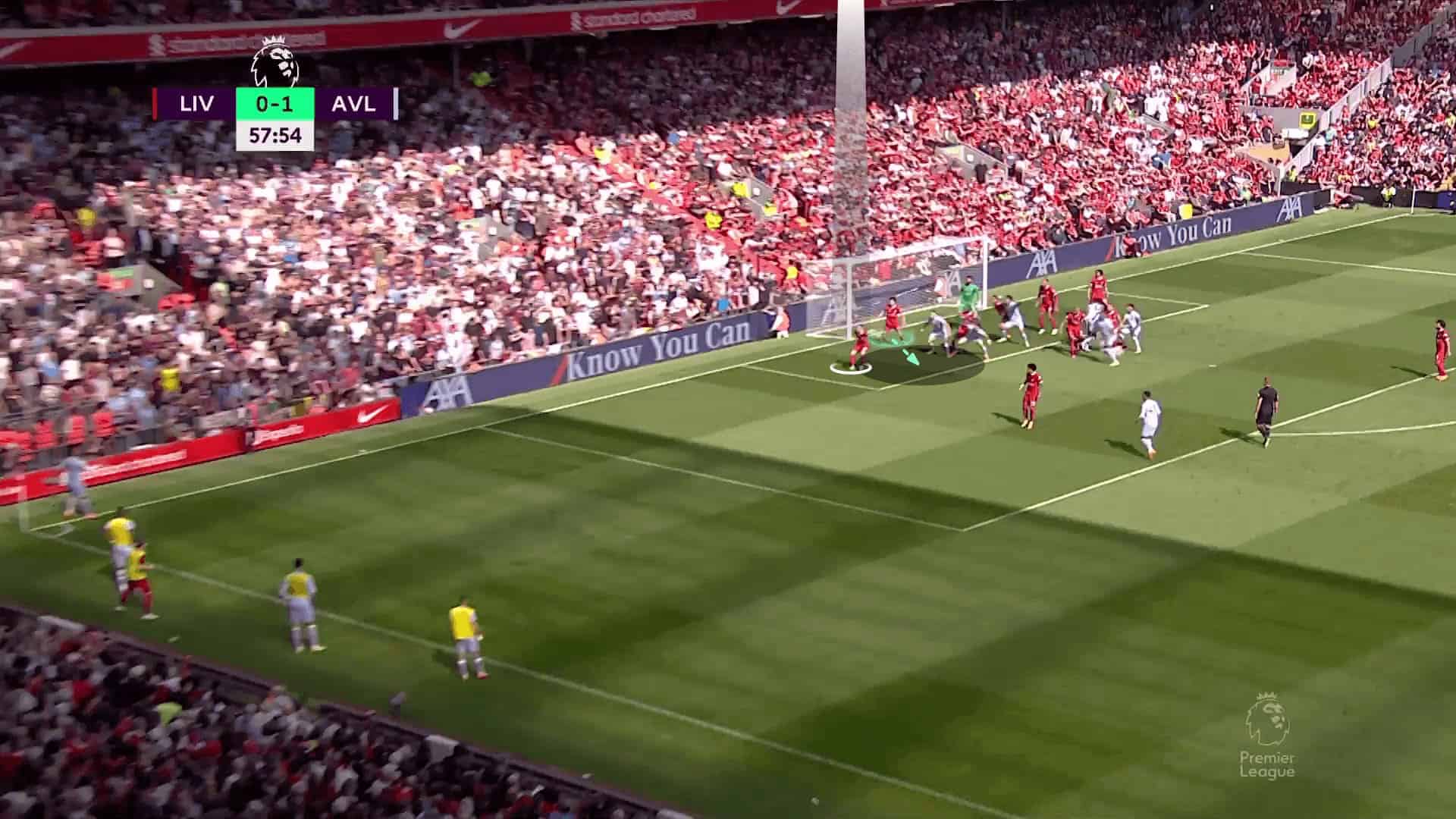

Below, you can see Aston Villa intending to target this area by a player blocking the zonal defender and the other to get the ball.

Still, Liverpool don’t give him this chance, as shown in the second photo below, in which the six-player zonal line is organised with no gaps.

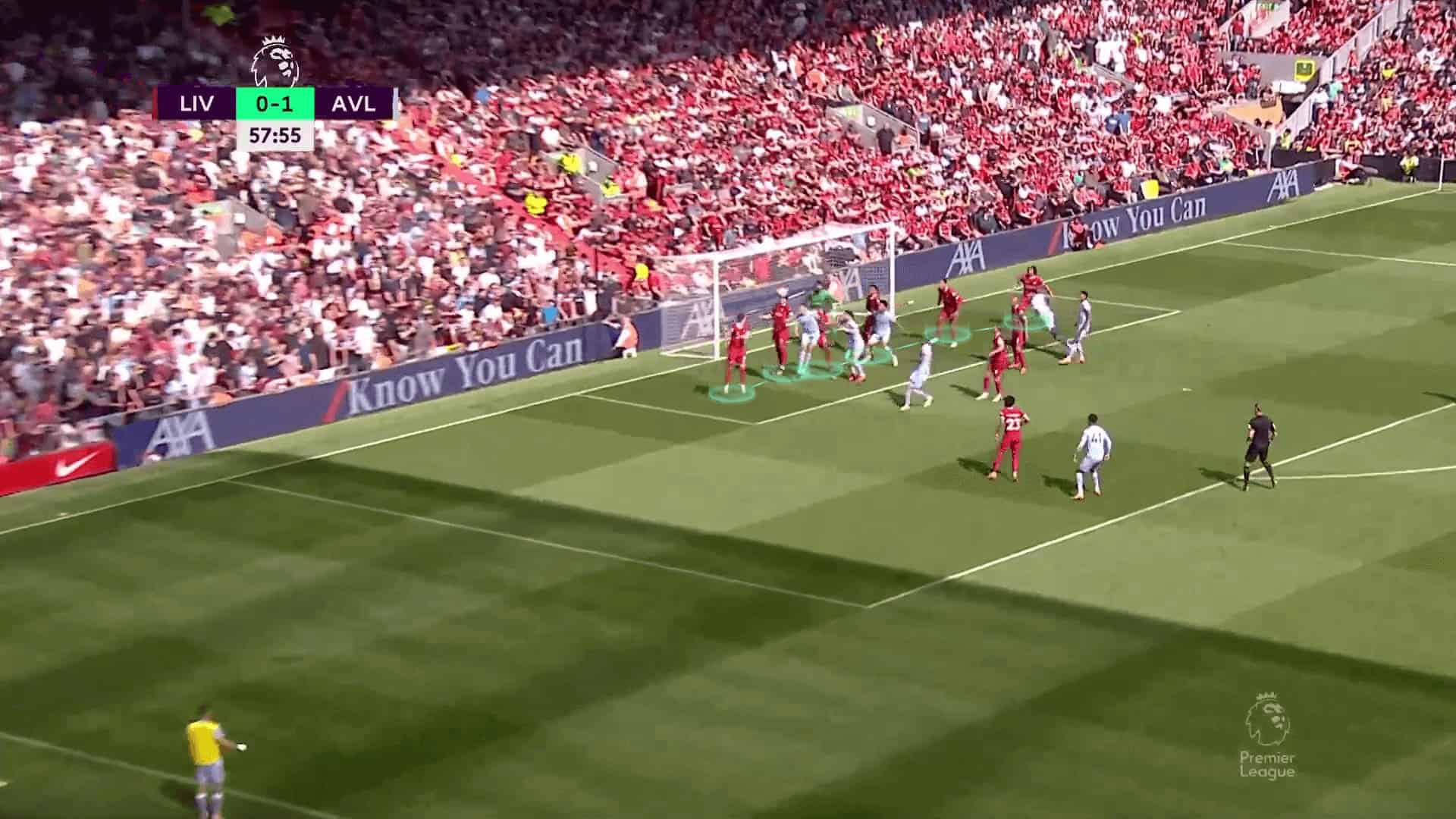

Despite this strong scheme, Brentford, in the prior season, found a good way to score a goal after some touches to prevent that needed shifting, and it was an inspiring idea despite the goal being considered an own goal.

In the two photos below, without going into many details, the key idea was to use two attackers.

One would move forward, dragging the first zonal line, while the other would block the zonal defender on the near post, preventing him from covering the area we talked about above.

Thus, the area would become empty and ready to be targeted using many different tactics.

Less Zonal Defenders

In this kind, previous shiftings are demanded in addition to other shifting through the goalmouth, which is dangerous, but let’s say that these teams depend more on man markers and the goalkeeper, who fills the gaps due to any shifting and claims the ball.

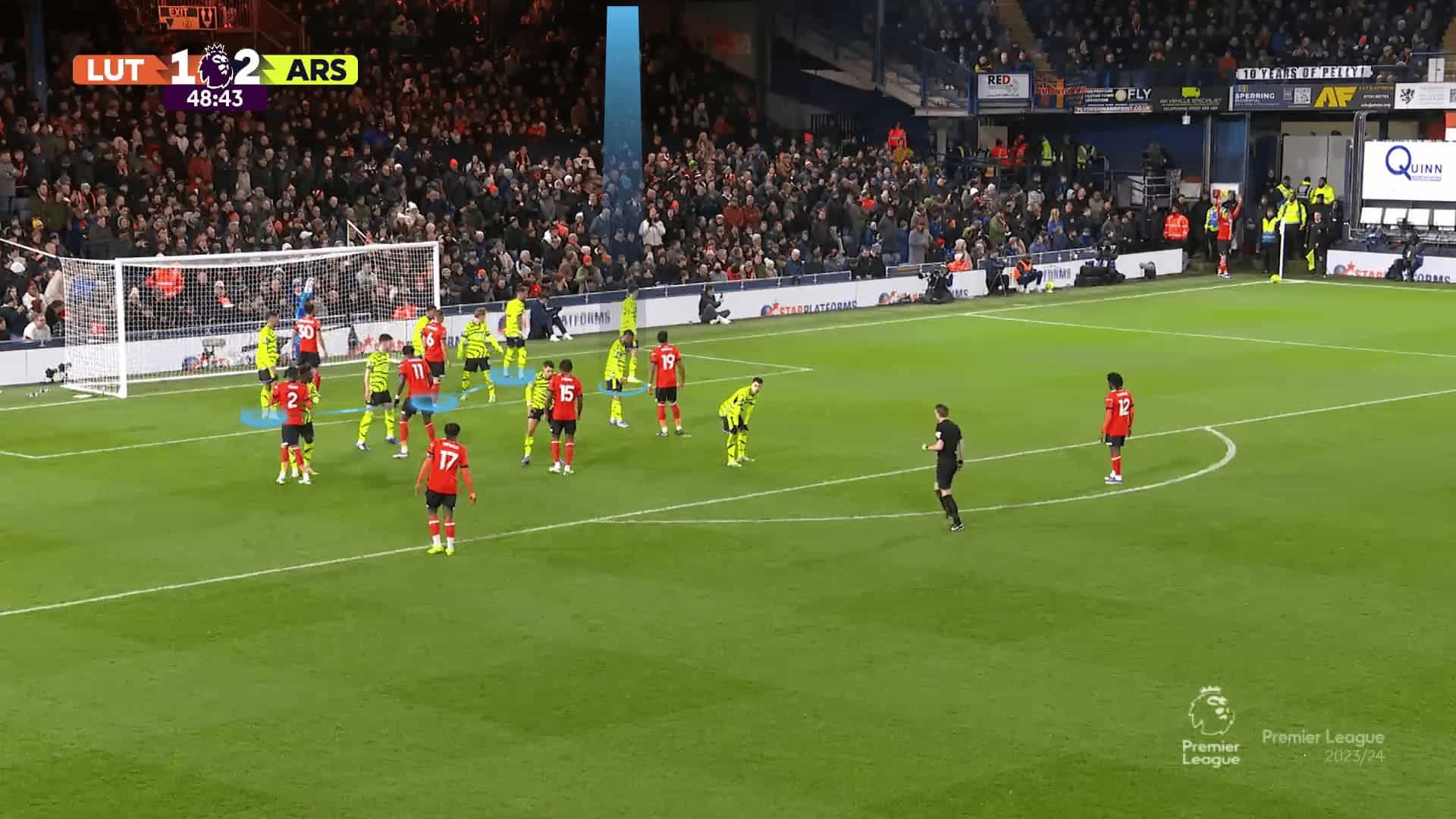

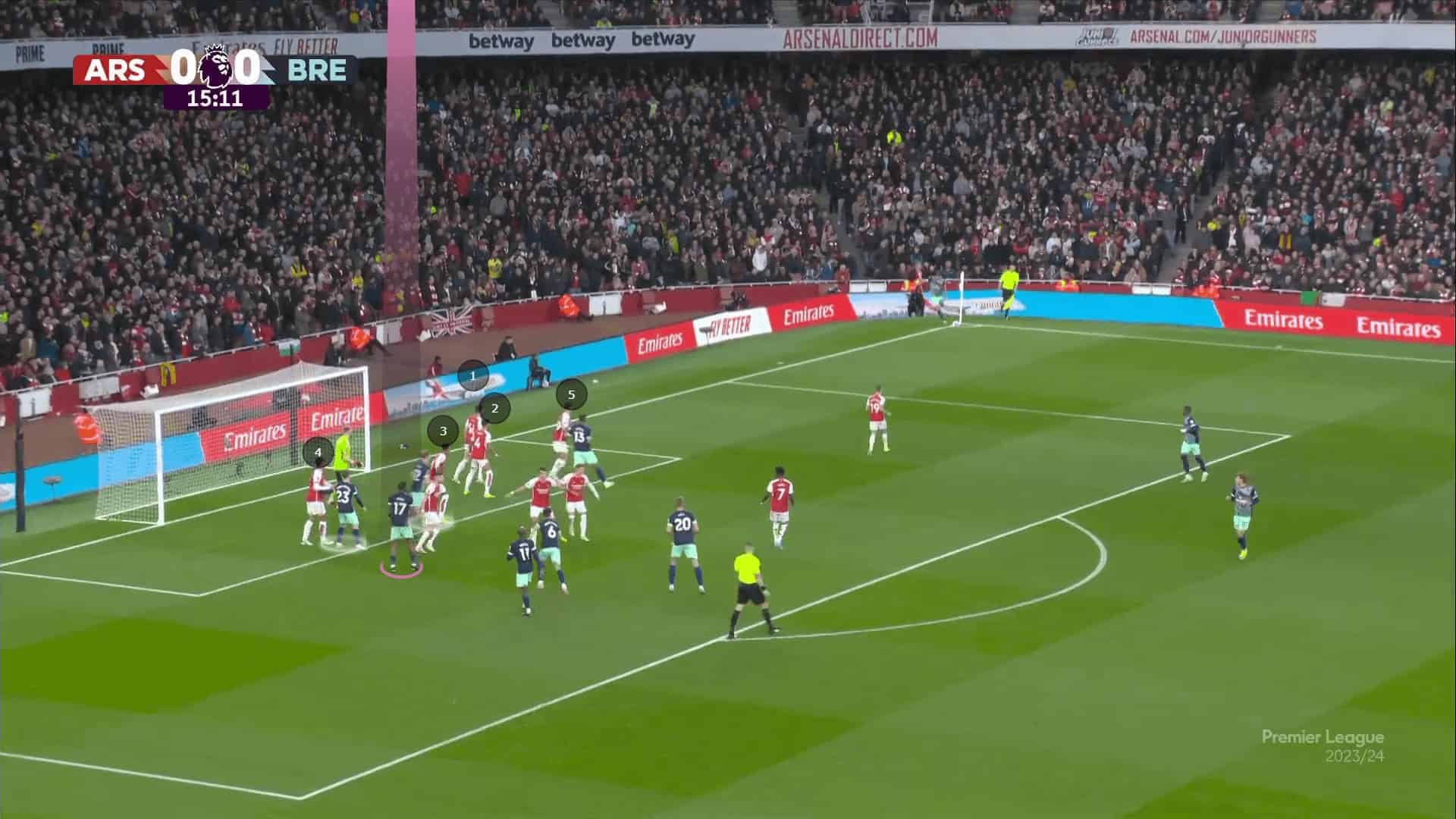

Let’s take Arsenal as an example.

In the photo below, Arsenal use only four zonal defenders, which makes the interspaces bigger.

That also usually makes them dispense with “Robertson’s role”, which forces the first zonal defender, Kai Havertz, to have a double role:

- Defending the near-post area

- Going to chase the ball to get the first touch before the opponent’s flick

In the end, they decide to make him stand with a different open body shape to track any attacker trying to get the first touch while also not sticking to the post because if he did, he would be late on getting the first touch before the attacker near the corner of the six-yard box.

West Ham exploits it by directly targeting this unprotected area with a deceptive run toward the flick area to ensure he will be dragged.

This shift empties the near post itself.

The second zonal defender, Ben White, is forced to step back to end with an own goal, as shown below.

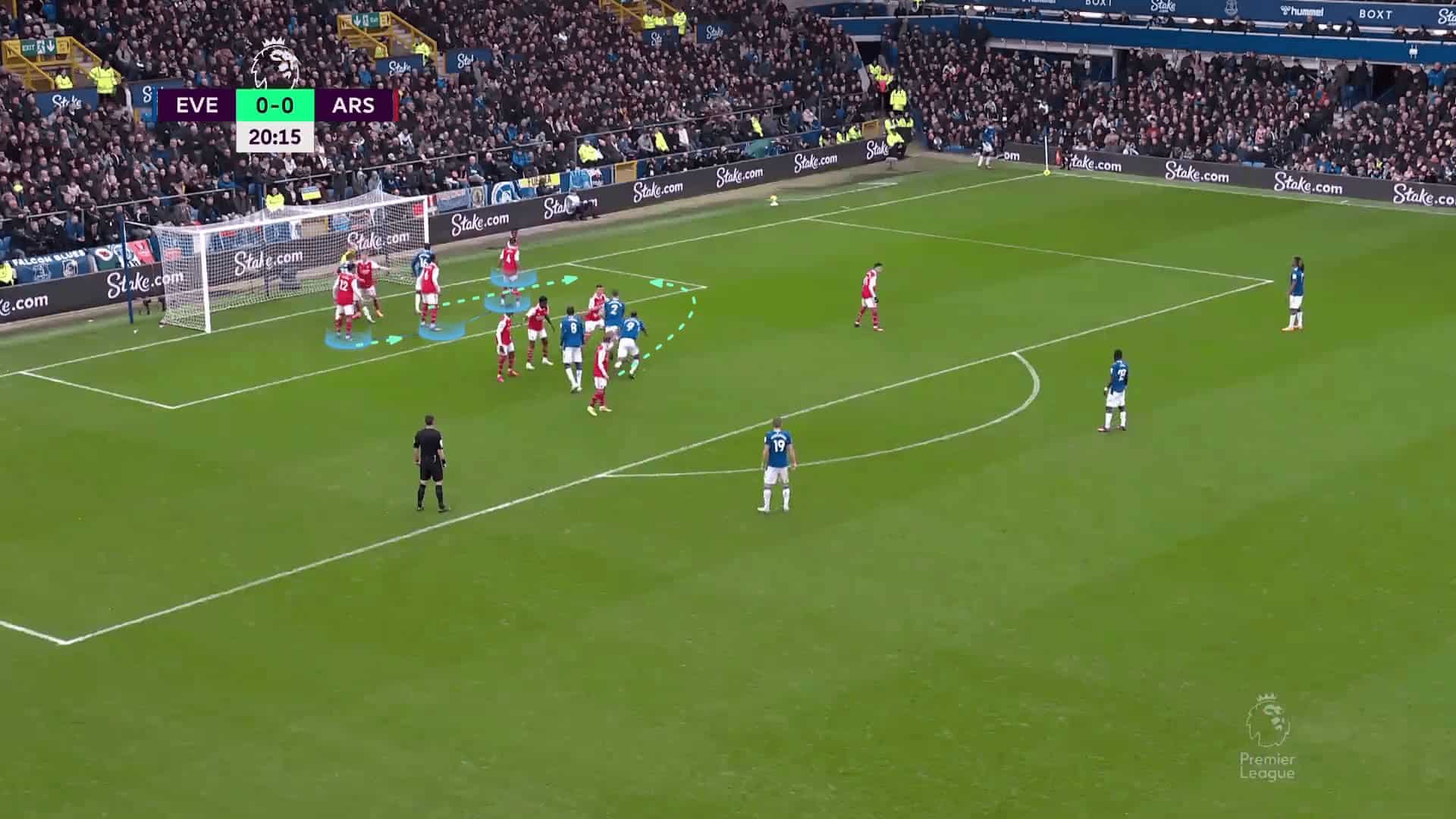

Continuing with this idea of a fake flick to target the near post, Man City were about to score a goal using a similar idea.

In the photo below, you can also notice the bigger interspaces than Liverpool’s case, while Man City initially put an attacker on the flick area to drag Havertz, and thus, the line moves a little forward.

Rodri, in green, will run to block the second zonal defender and motivate him to step more forward, increasing the gap between him and the third zonal defender, Gabriel Magalhães.

This gap is targeted by two different players from different angles.

Nathan Aké pushes his marker, Jorginho, coming from the back, leading to a dangerous chance, as shown below.

Now, you may think that they sacrificed the near post itself to get the first touch in the flick area.

You are right, but we should also mention that Havertz’s in-between starting positions sometimes make it longer to prevent the flick, especially when an opponent makes a deceptive run to take his attention momentarily.

In the photo below, the first white attacker moves to take Havertz’s attention while the second white attacker blocks the second zonal defender to make sure that he won’t behave and go to chase the ball.

All of that is to empty the corner of the six-yard for the targeted player in pink.

The plan works, as in the two following photos.

It may be predicted that it won’t be as effective as Robertson’s separated role, and this makes sense, but we should also mention that it is all about the coach’s perspective.

The second kind counts on using more man marking than the first kind, so the free attackers will be fewer while also mentioning the critical role of the goalkeeper to fill these gaps and claim the ball, especially David Raya.

Therefore, only excellent teams could exploit that shift with brilliant and well-prepared movements, and they have some ideas for defending against such brilliant teams during the season.

As shown below, the first solution is to make the four zonal defenders in a 3-1 shape, meaning that three players cover the goalmouth while Havertz plays Robertson’s role.

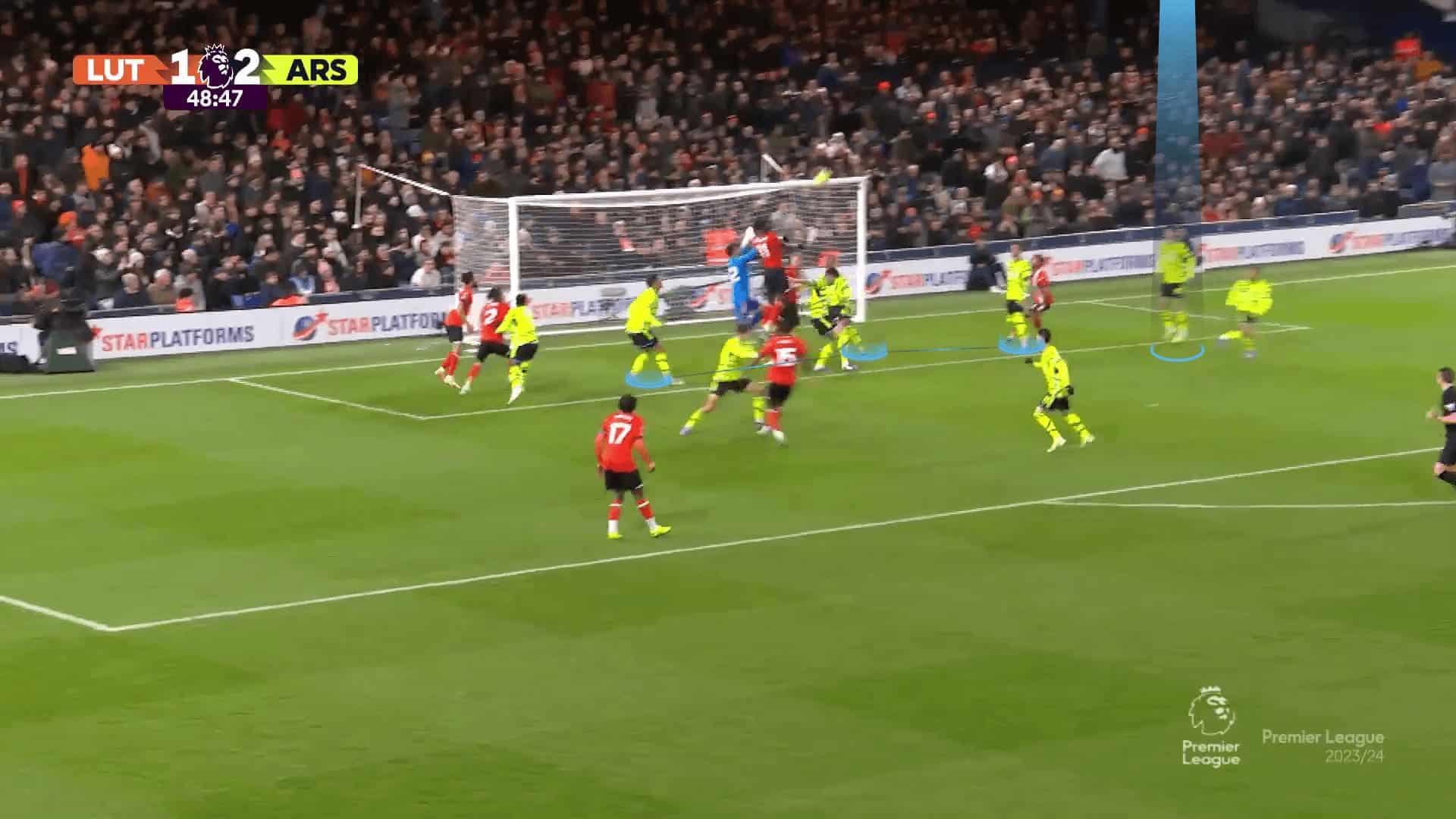

Luton Town used the same shifting principle to create a gap between the last two zonal defenders.

The attacker starts with the goalkeeper and then steps back to drag the last zonal defender a little back.

In contrast, the other white-highlighted attacker pushes Gabriel, the third zonal defender, forward to create the gap for the targeted player in pink, who can overcome his marker.

The plan works, and the result is a goal.

Here, we should mention that David Raya is brilliant at this job, but decreasing the zonal defenders increases the challenge on the goalkeeper and the man markers.

West Ham also found a good counter-idea to target the near-post, but at an outer position, the zonal defender comes late because he is dragged more inside because West Ham overloads the area behind the zonal line with two players.

We should also mention that the targeted player can escape from his marker, Oleksandr Zinchenko because the best defenders are in the zonal defenders, which is the dilemma.

The plan works, and the result is a goal.

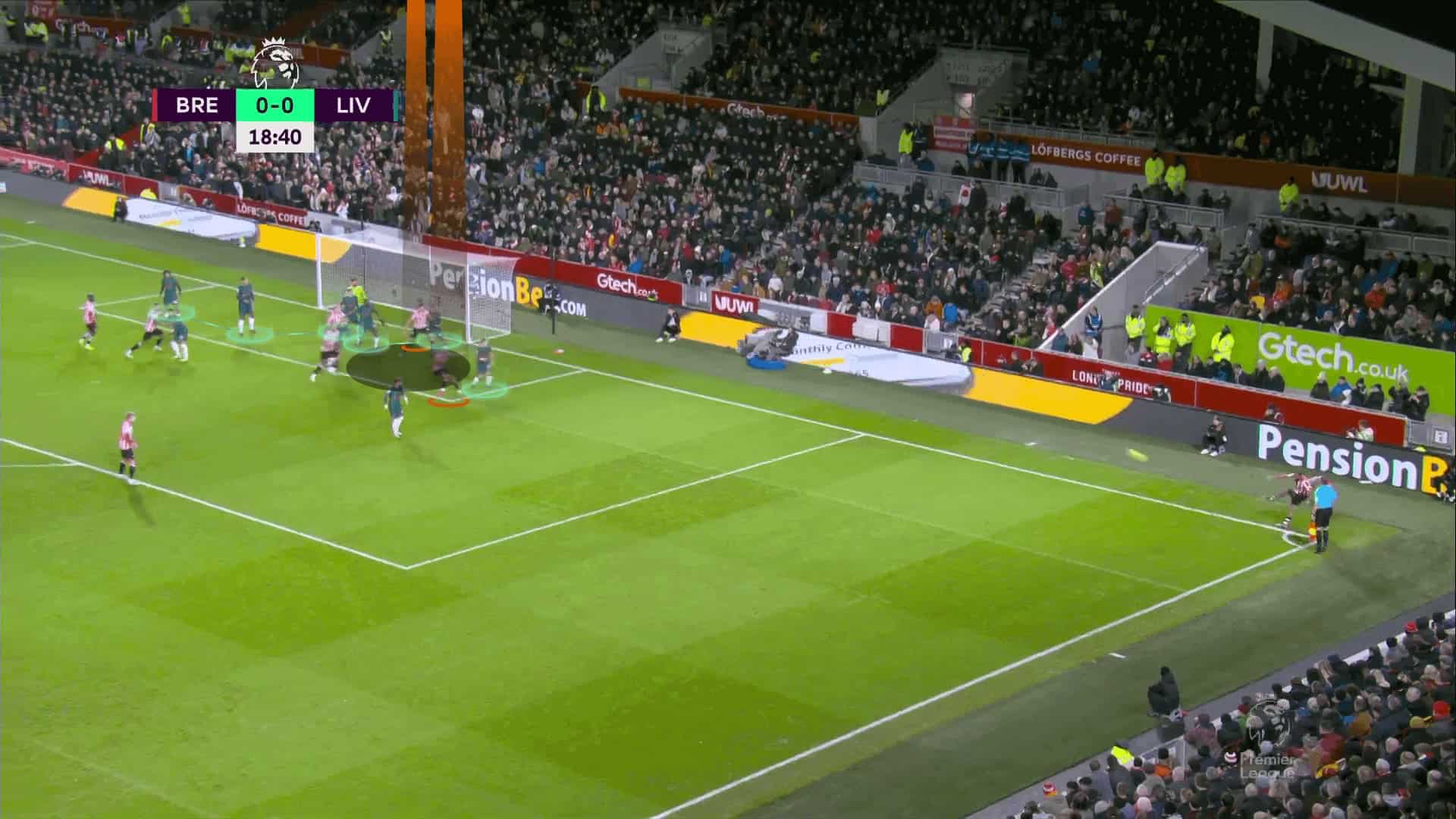

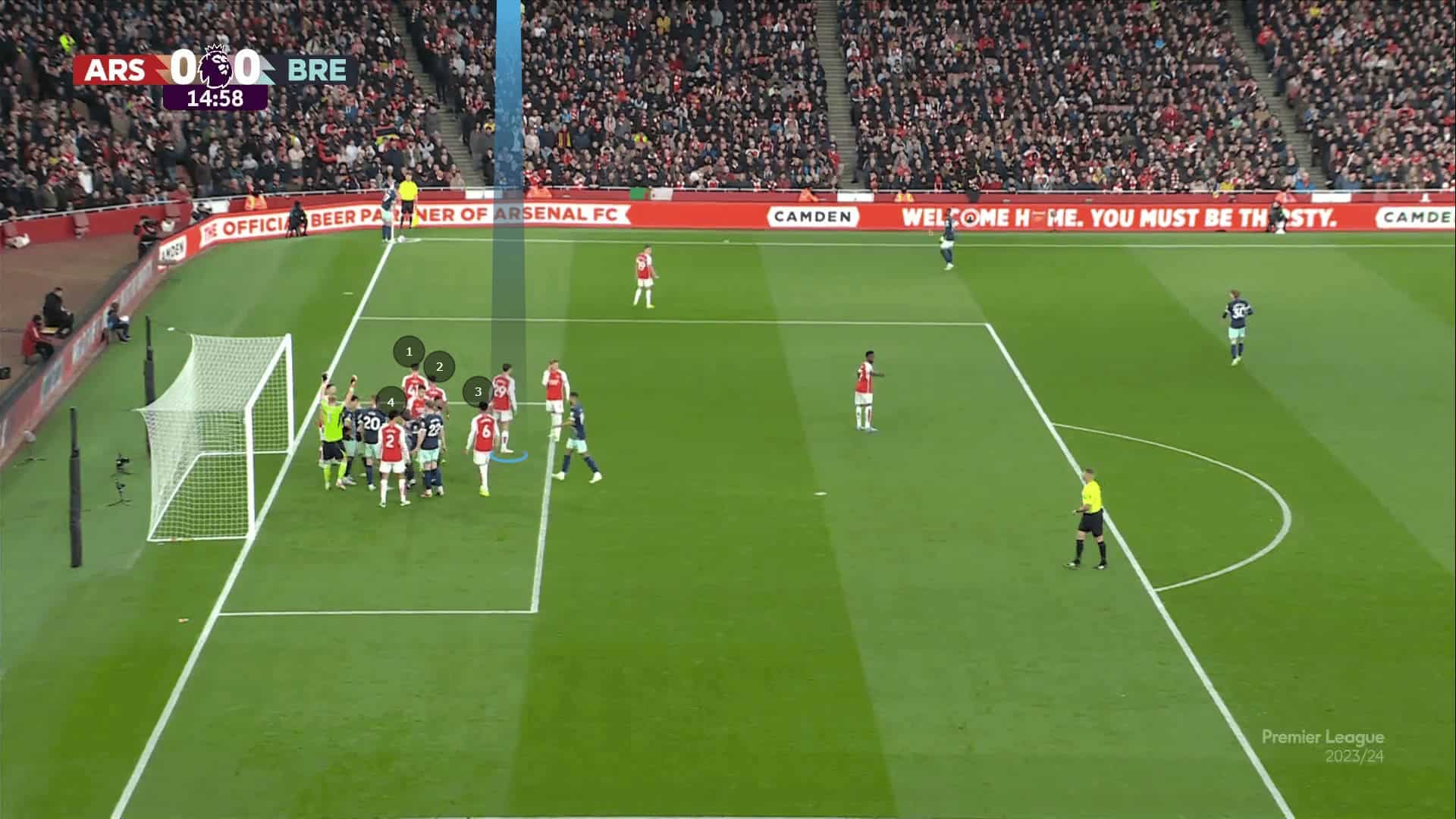

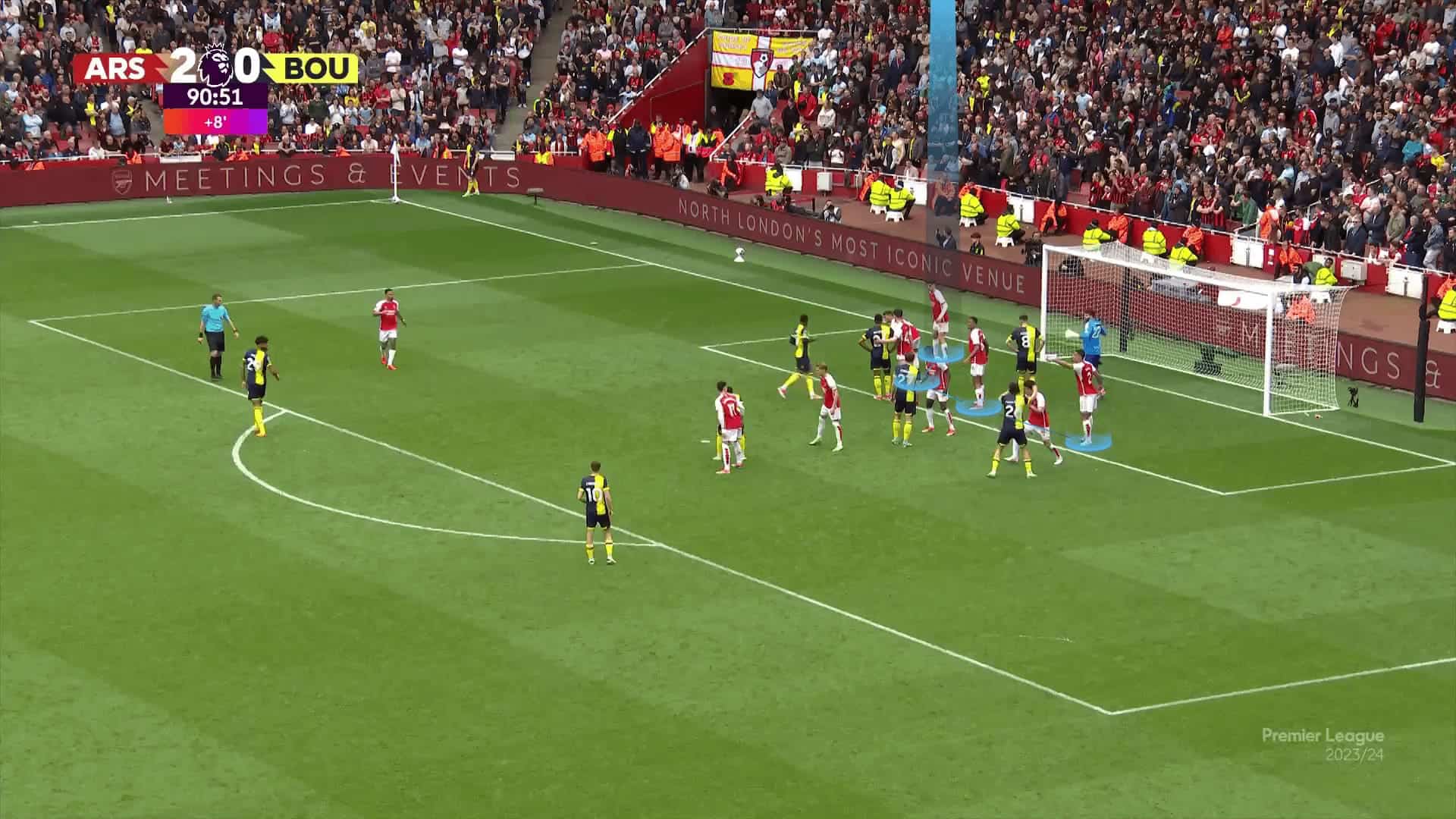

The second tactic they relied on when facing such tough opponents at targeting the near post was increasing a fifth zonal defender to play Robertson’s role while keeping the other four defenders near the goal, especially against teams that overload inside the six-yard line to drag the line inside.

Brentford’s runners start in the six-yard and then spread into their assigned positions to manipulate man markers.

That leads to the freedom of Ivan Toney because the three man markers are attracted to the far three attackers.

At the same time, two white blocks are done to the third and fourth defenders to create a gap, which will be the targeted area.

The plan works, but it ends with a dangerous chance.

The shifting may start on the far post and may affect it if every defender makes a step forward due to deceptive runs.

In the photo below, two green deceptive runs from different angles shift the whole line, which makes the last zonal defender.

When the last zonal defender realises the trap, he steps backwards, giving the targeted player an advantage, ending with a dangerous chance, as in the two following photos.

In the photo below, the last zonal defender gets the idea in the next corner, so he chases the ball in the area after the far post, but his mates are still in their positions.

This affects the gap between the third and fourth defenders, which would be dangerous if the targeted player managed to play the headed pass.

That far-post-affected shift is familiar, especially on teams who ask the line to shift more toward the near post from the beginning, prioritising the near post and the middle and depending on the goalkeeper to claim the ball before getting there.

At the end of the season, Arsenal is still convinced by the same idea, with Havertz’s only difference being a different body shape to make him more ready for both cases, as in the photo below.

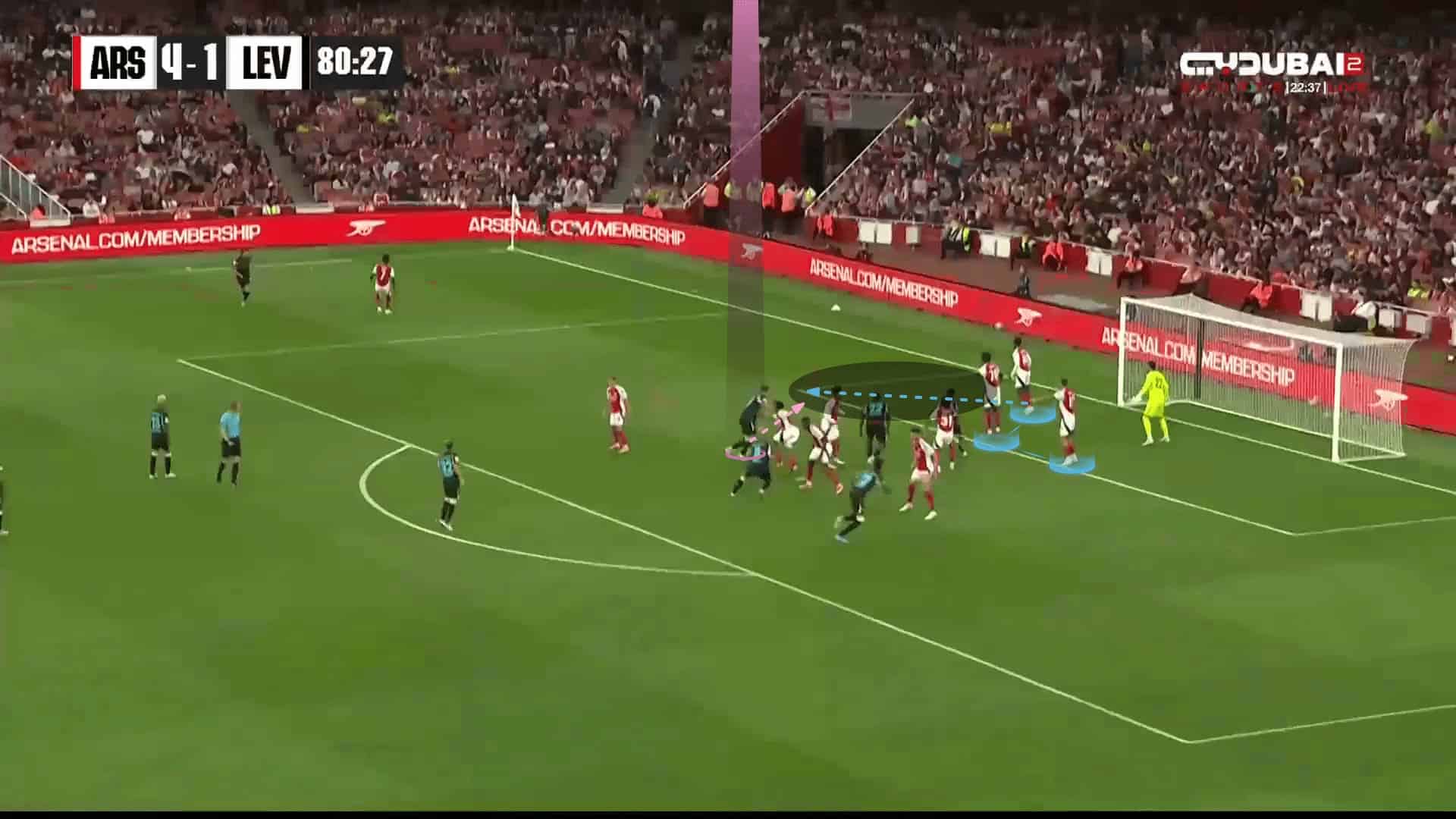

In this pre-season, Arsenal decided to depend more on man markers and the goalkeeper, decreasing the number of zonal defenders to three.

As we have mentioned, every perspective has its advantages and disadvantages, but we predict more suffers from shifting.

For example, the targeted player manages to reach the targeted area before the first zonal defender, who should cut a long distance to reach it, as in the photo below.

Let’s wait and see whether it will work with more dependence on the goalkeeper and man markers, or will they suffer?!

Conclusion

In this analysis, we have discussed the different reasons and results for zonal-line shifting during corners and shown its impact on various kinds of zonal lines.

In this set-piece analysis, we have also mentioned that the number of zonal defenders differs from one coach’s perspective to another, trying to show how much shifting is needed in each scheme.

Comments