At the beginning of October, Sevilla’s board made the difficult decision to part ways with Julen Lopetegui after just over three years in charge of the La Liga club.

The now-Wolverhampton Wanderers boss certainly left his mark in Andalusia, guiding the Seville-based side into the UEFA Champions League in three consecutive campaigns while also putting Antonio Conte’s Internazionale to the sword in the UEFA Europa League final in 2020, lifting the continental crown for a record sixth time.

Unfortunately, performances and results had significantly dwindled by the end of the 2021/22 campaign and this hangover carried on into the current season. His sacking didn’t come as much of a surprise in the end.

Jorge Sampaoli replaced the former Real Madrid boss in the hot seat for his second stint with the historic club, having previously managed the team during the 2016/17 season before leaving to become the head coach of his native Argentina that summer.

The appointment made sense. Sampaoli had done an excellent job last season with Marseille in Ligue 1, helping the French giants to second place behind the obscenely affluent Paris Saint-Germain, which is certainly no failure.

Nevertheless, Sampaoli’s second term at Sevilla did not go as well as his first. The 63-year-old lost 39 percent of his games in charge, winning just 42 percent and, as of this week, has been dismissed from his post with the side sitting twelfth but merely three points above the drop zone.

This tactical analysis piece will be an analysis of why Sampaoli’s progressive tactics failed at the Ramón Sánchez Pizjuán Stadium.

Formations and tactical style

Sampaoli was a natural progression from Lopetegui. Where the latter implemented a system centred around positional play principles and the retention of the ball, the former’s philosophy was just a stone’s throw from his predecessor.

The Argentine coach was adamant on playing football in this same manner, although it was perhaps slightly less restricted than Lopetegui’s rigid set-up.

Unfortunately, Sevilla’s style became somewhat lethargic and tedious to watch, being heavily focused on having the ball, but not much was being done with it. Possession without purpose is pointless. As the late, great Johan Cruijff once said:

“Possession for itself is worthless if you don’t know what to do with the ball later.”

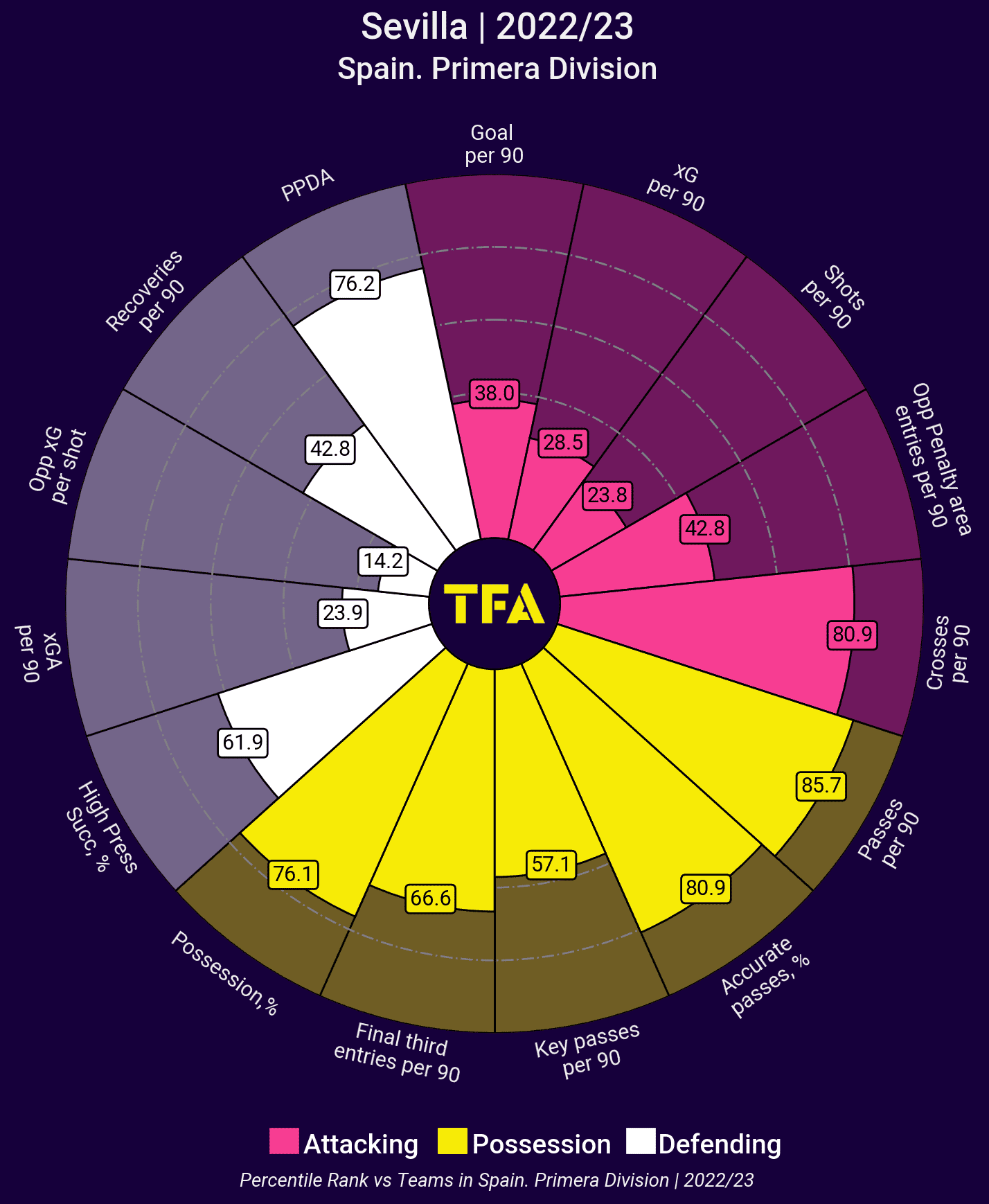

A look at Sevilla’s stats from this pizza chart tells the whole story without even deep-diving into any in-game tactical observations – although, don’t worry, we’ll get to those eventually in this team scout report!

Los Rojiblancos ranked extremely high compared to the rest of Spain’s top-flight division when observing metrics such as passes per 90, average possession, accurate passes as well as crosses per 90. Sadly, this didn’t translate into goals as Sevilla struggled to score goals, create much xG, get shots away and even get into the penalty area.

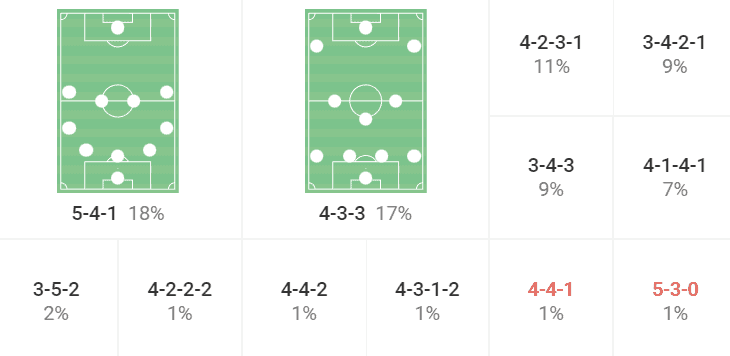

Lopetegui was particularly dogmatic with his approach during games, refusing to shy away from the 4-3-3 which had seen him have great success throughout his time in Andalusia. However, Sampaoli was slightly more flexible.

The two-time manager used a blend of a 4-3-3 and a 3-4-3 with Marseille during his reign eight months prior. Often, these two formations would become infused. For instance, if Marseille deployed a 4-3-3, it wasn’t uncommon for a midfielder, such as Boubacar Kamara, to drop into the backline during the attacking phase while the fullbacks advanced, creating this 3-4-3. At Sevilla, things were pretty much the same.

It isn’t a shocking revelation to find that the variations of the 3-4-3 (such as the 5-4-1 and the 3-4-2-1) and the 4-3-3 were the most utilised shapes by Sevilla this season.

But what is also evident is that because results were largely horrendous this season, Sampaoli switched formation countless times to more uncharacteristic and unfamiliar structures like a 4-4-2, a 4-4-2 diamond and a 4-2-2-2.

Nevertheless, if football coaching was as simple as deploying a formation, it would be the easiest job in the world. In the case of Sevilla, it was far more than mere telephone numbers – as Pep Guardiola calls formations – that led to the dismissal of Sampaoli so soon after his appointment.

Imbalance to the positional structure

The previous section referenced how Sampaoli’s football was a little less restrictive than under Lopetegui. But what exactly did this mean?

Essentially, Sevilla’s players had a tad bit more room to roam around the pitch. The positional structure wasn’t absolute in its distinction but could bend and be flexible depending on what spaces were available on the pitch.

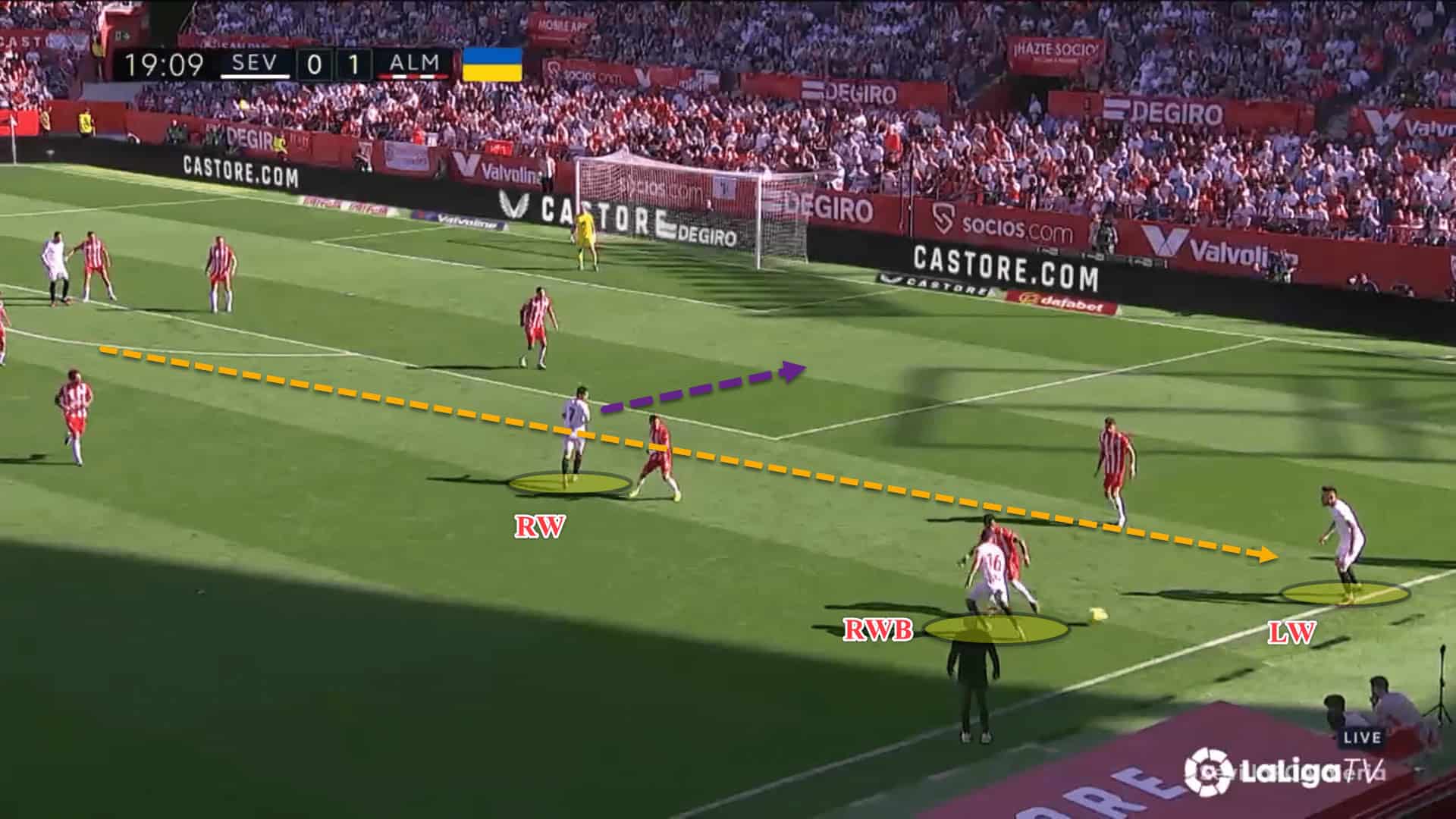

Sevilla set up in a 3-4-3 but it was more fluid than this. The 3-4-3 is merely a reference base. Players could drop in and out of different spaces to receive the ball, create overloads and link up with teammates. The system was fluid but often this left them unbalanced when the ball was turned over.

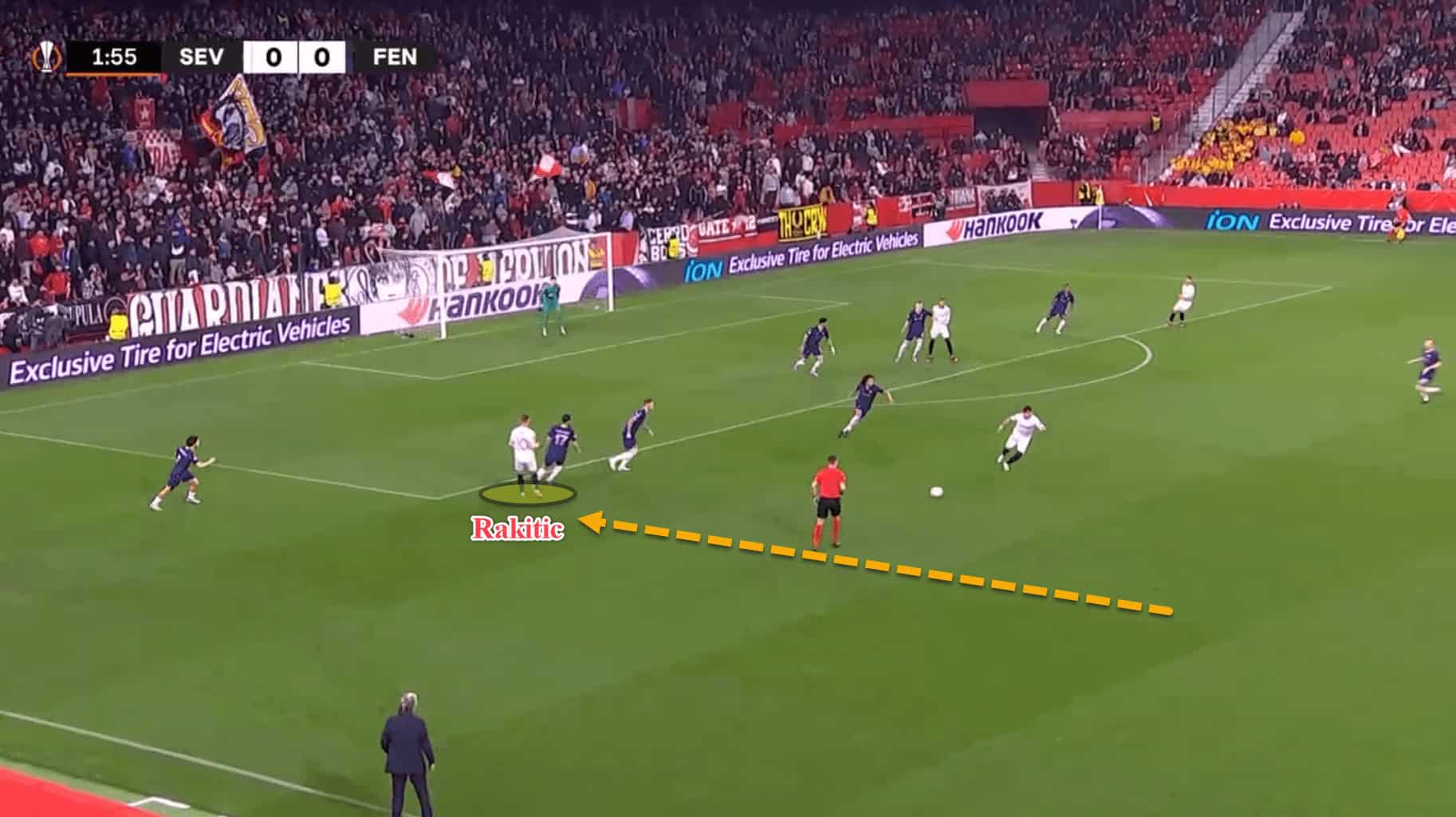

For instance, one of the key tactical patterns that Sevilla used under Sampaoli was having both wingers drift across to the same side.

Here, Lucas Ocampos, who started as the left winger in Sevilla’s 3-4-3, came all the way across the pitch over to the right side and formed a wide triangle with Jesús Navas at right-back and right-winger Suso.

This trio possess a lot of technical quality and combine relatively well with one another, playing one-twos, making runs in behind and using the third man to break down the opposition’s defensive block.

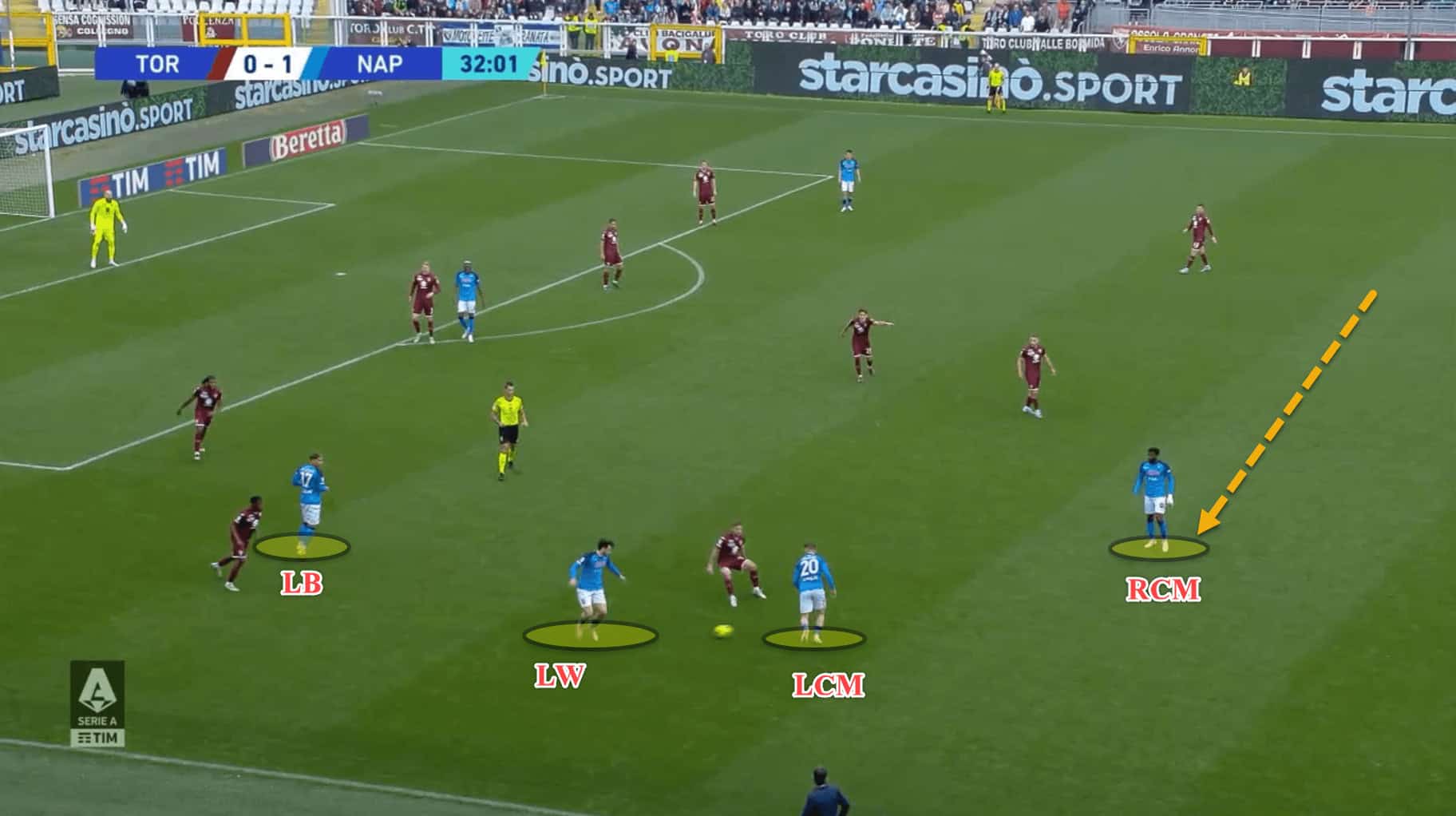

Napoli perform a variation of this but instead of having the two wingers in the same area, both central midfielders in the side’s 4-3-3 create an overload out wide with the fullback and the winger.

In this example, André-Frank Zambo Anguissa came over from the right to link up with left central midfielder Piotr Zieliński, left-back Mathías Olivera and left winger Khvicha Kvaratskhelia.

It is situations like these where tactics become ‘relationist’ as opposed to ‘positionist’. Sampaoli, like Napoli boss Luciano Spalletti, was fine with having some of his best technical players leave their set positions to combine with one another out wide to try and break down the opponent’s defensive block.

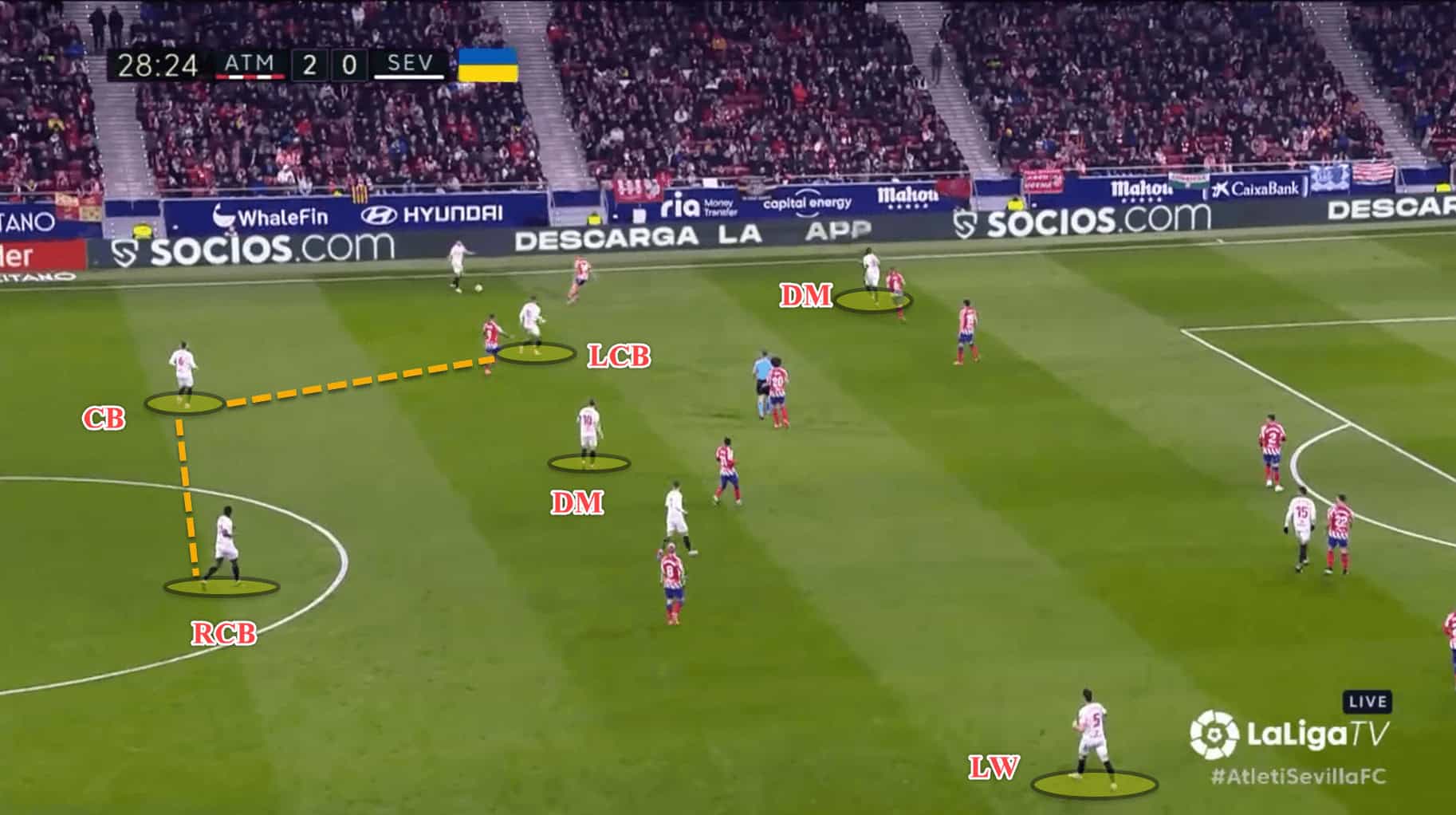

However, this does cause an imbalance in the team’s positional structure. As a result of having the two wingers on one flank, Sampaoli was having to try and plug the obvious gaps that were left on the other side. One way he did this was by having one of the double-pivot step forward into the left halfspace where the winger would normally be.

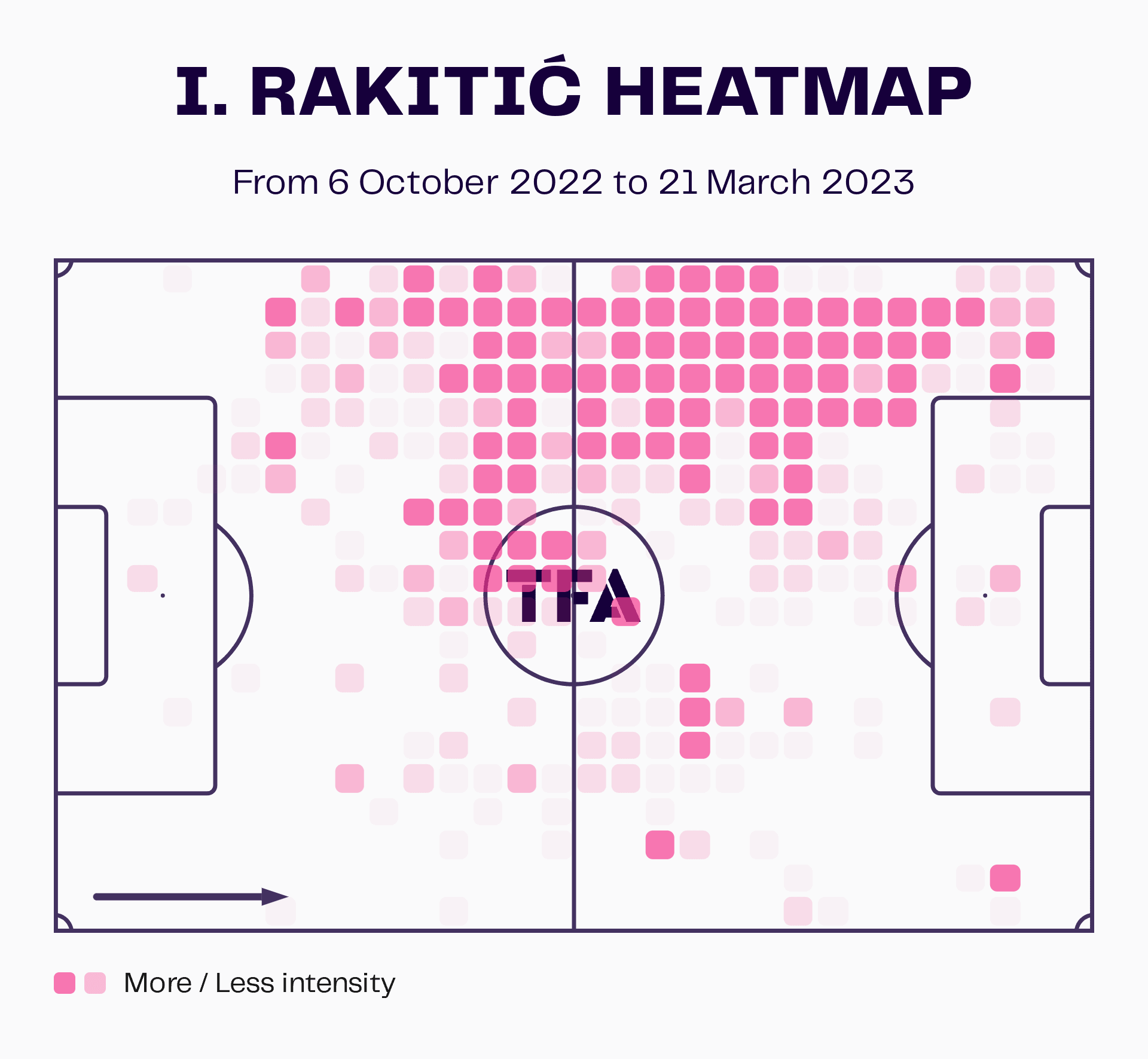

Ivan Rakitić primarily occupies these spaces at the request of his manager. Usually, a pivot player wouldn’t be positioned this high up the pitch, but the Croatian is comfortable in these areas, having played on the left of a 4-3-3, practically as a wide ‘10’, for most of his career at Barcelona and his second spell with Sevilla.

Even this season, when observing the experienced midfielder’s heat map, we can see that so much of his involvement comes in the higher areas, especially the left halfspace.

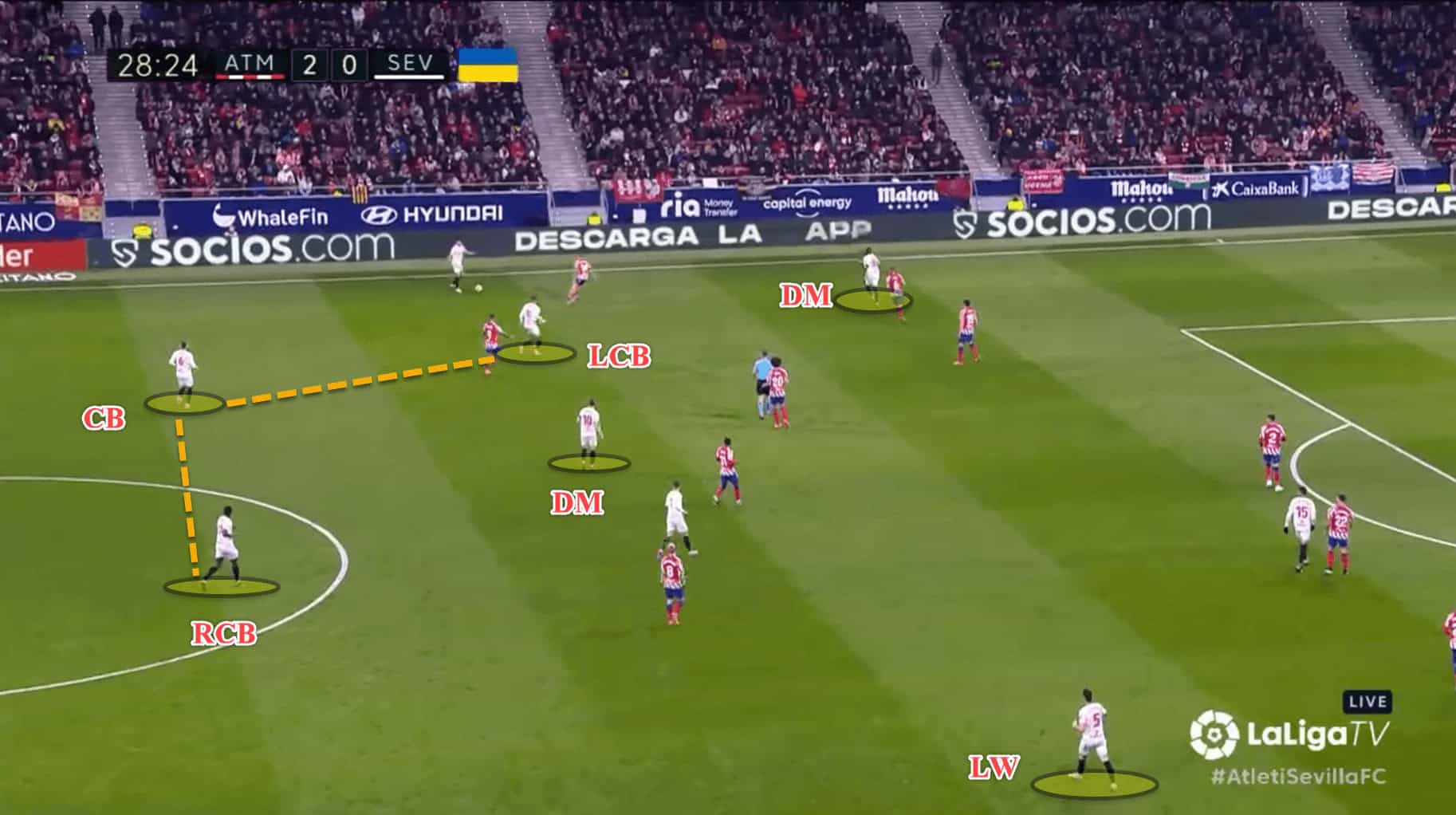

Nevertheless, having Rakitić in a higher position meant that a hole in the middle of the park had to be plugged as there was just one central midfielder left.

To do this, Sampaoli instructed one of his centre-backs to step into the midfield to offer a progressive passing option while the remaining two central defenders shifted across to the ball side.

In theory, this worked. The holes were plugged by the Argentine coach. However, the positional structure was still incredibly imbalanced.

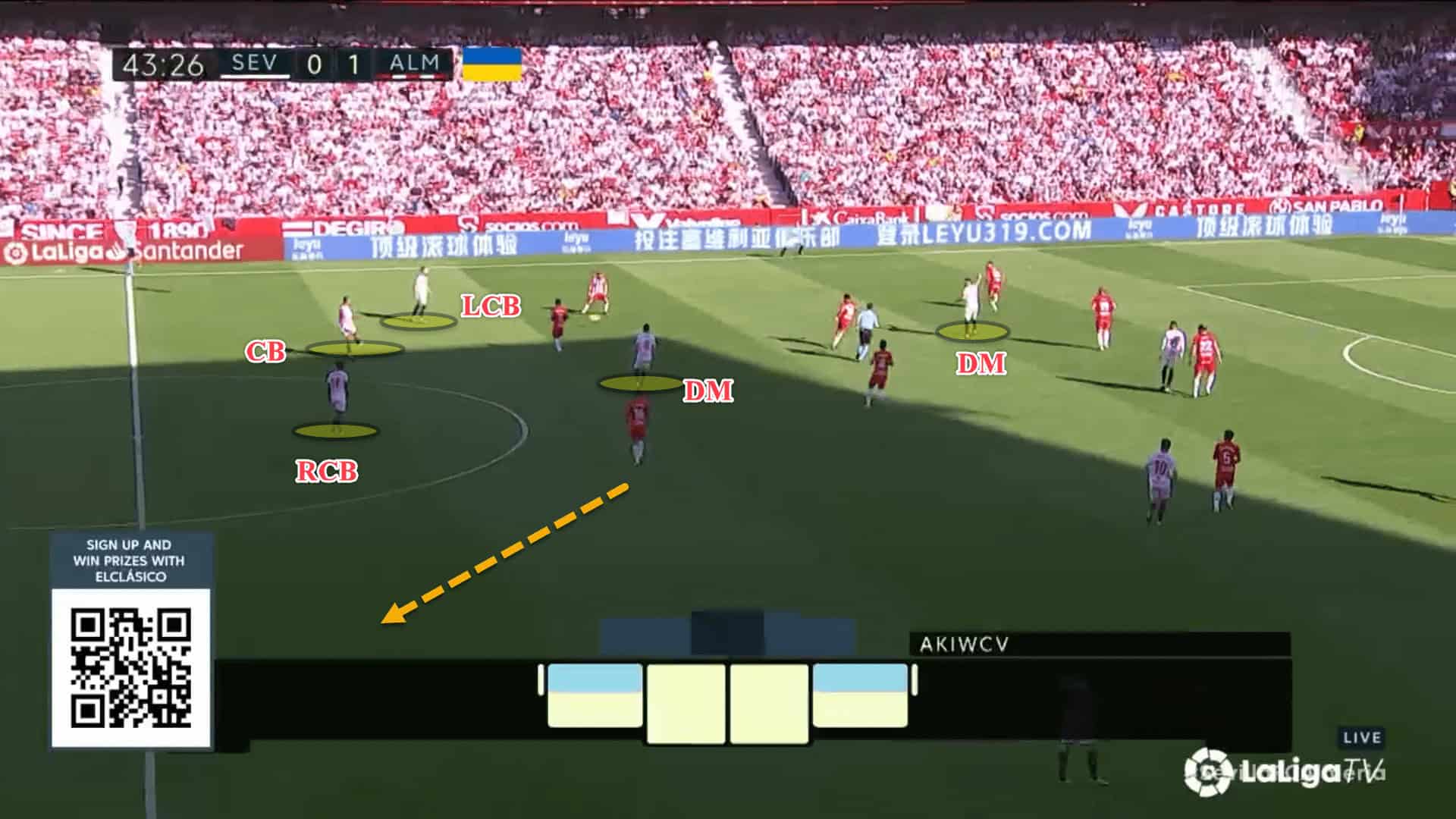

Since the wingbacks were both high and wide, one centre-back was in the midfield and the other two were positioned on one side, there was vast space on the opposite flank for the other team to exploit during transitions.

In this example, UD Almería fully took advantage of Sevilla’s peculiar and lopsided shape in possession. There was no positional cover on the right-hand side so that’s where the visitors focused most of their counterattacks. It led to a dangerous opportunity for La Liga’s minnows.

Ultimately, while Sampaoli wanted his tactics to be a little more fluid than his predecessor, it caused far too much disruption to the rest of the structure, particularly when players were on completely opposite flanks.

Struggling to create, struggling to score

Sevilla are the eighth-lowest goalscoring team in La Liga this season, or the twelfth-highest if you like to look at things with a positive perspective. Nevertheless, Lopetegui’s men were the sixth-highest last season.

Goals have really dried up for the Andalusian club but it’s important to analyse whether or not the issues stem from an inability to finish chances or if the food isn’t coming out of the kitchen in the first place – or potentially a bit of both.

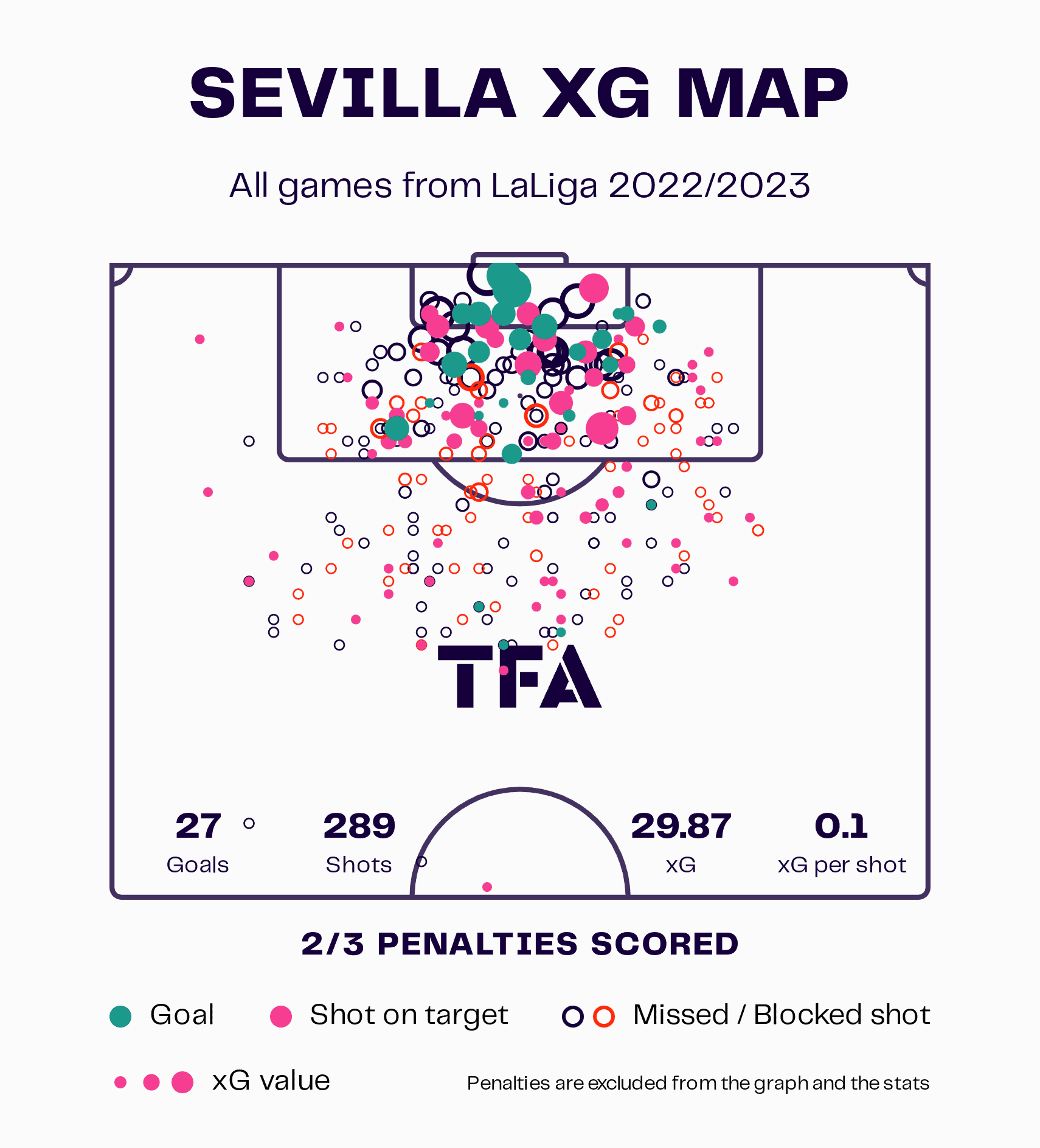

Over the course of the campaign so far, Sevilla have scored 29 goals, including 27 non-penalty strikes. With a mix of Lopetegui and Sampaoli, the side did underperform their xG of 29.87, but not by too significant an amount.

One of the primary reasons for this was that the team registered an xG per shot of merely 0.1 which is quite low and so most of Sevilla’s opportunities in front of goal were of low quality.

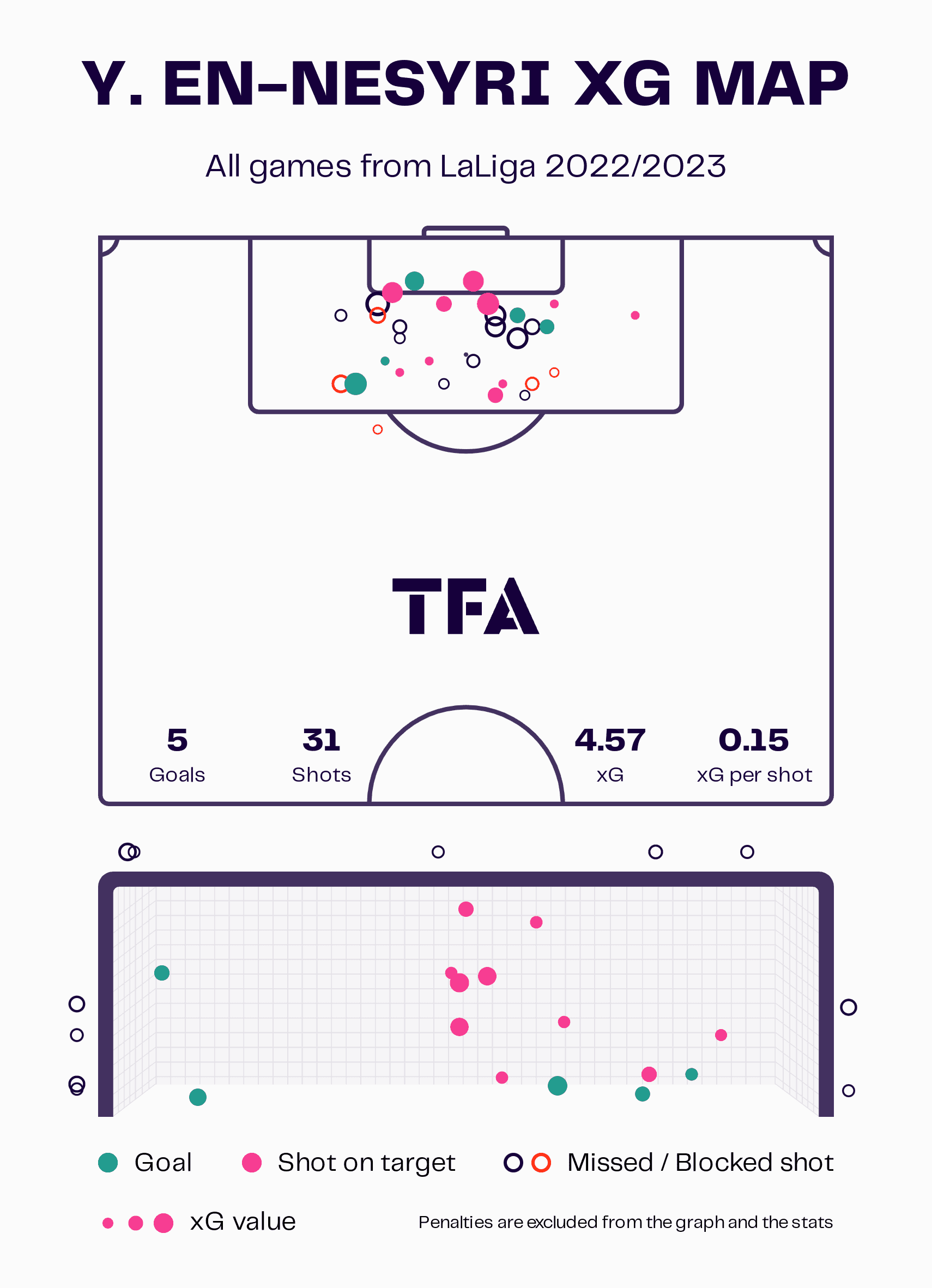

Neither Lopetegui nor Sampaoli had a prolific goalscorer in the number ‘9’ spot this season. Youssef En-Nesyri was primarily tasked with leading the line, but the Moroccan striker has scored just five league goals in the entire campaign.

Nonetheless, as we alluded to earlier, the food really isn’t coming out of the kitchen for Sevilla this season, and when it does, the taste is stale, off-putting and downright tasteless.

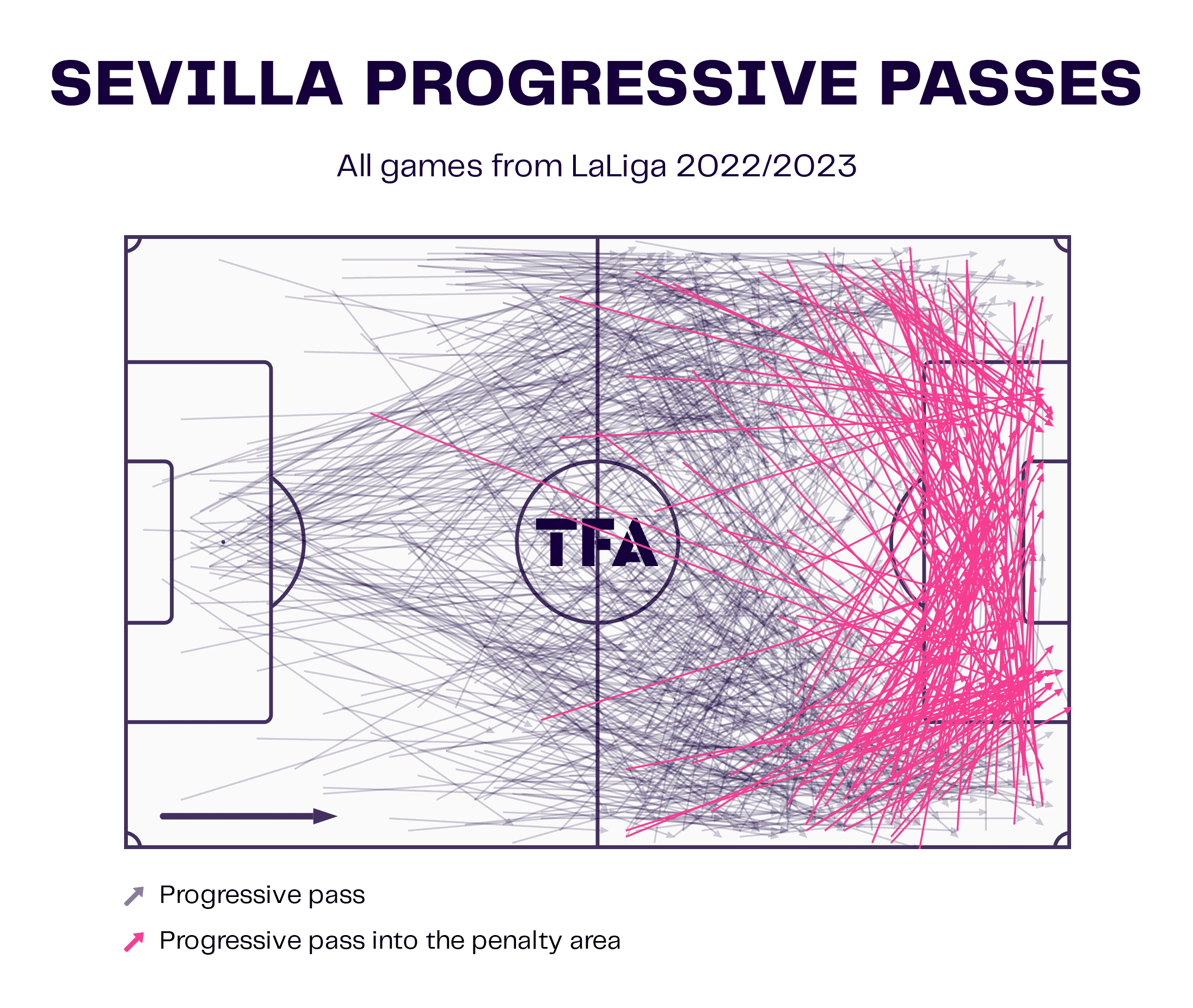

There is very little central penetration from Sevilla which has been a common theme across the whole season across both managers’ tenures. However, under Sampaoli, deep crosses from the flanks were the primary method used by the players to create opportunities.

Sevilla mainly cross the ball from this area which is located near the first corner of the penalty box and has previously been labelled as the Trent Alexander-Arnold zone. The wingbacks are the most important players to play these crosses into the box, with the wide playmakers coming close in second.

But there was a severe overreliance on whipping these early crosses in from the flanks under Sampaoli. Ultimately, these are low-quality chances and so poor opportunities were created as a result.

Sevilla’s patterns of play became far too predictable.

As we can see from the team’s progressive passes this season, there was a constant pattern to their attacks. The ball was being moved out wide and then played into the box through either inswinging or outswinging crosses, depending on who the crosser was.

Passes through the centre of the pitch create the chances with the highest quality and so the scarcity of penetration through the middle of the opposition’s defensive block contributed significantly to Sevilla’s lack of goalscoring threat.

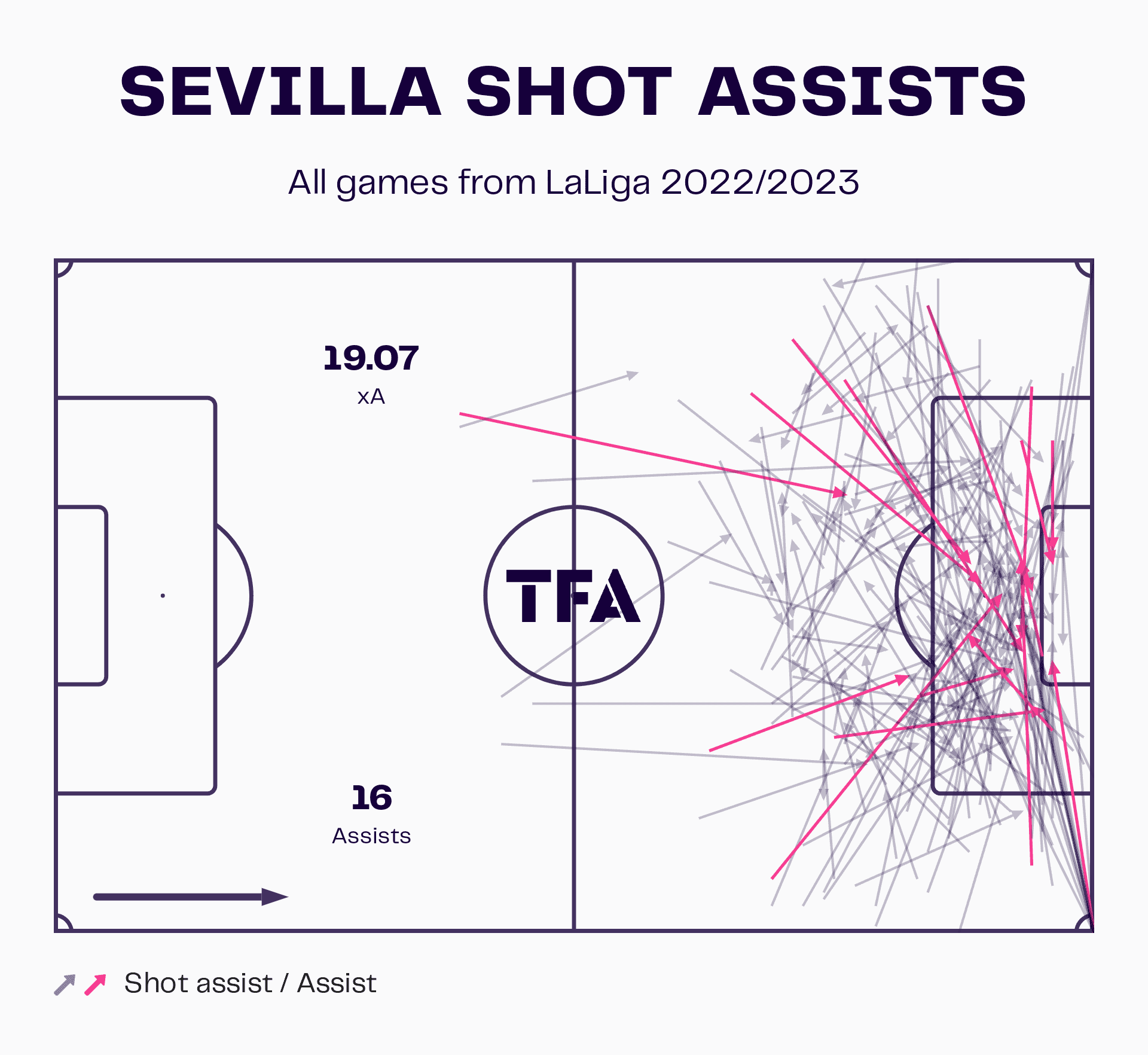

Again, from the team’s shot assists map this season, we can see that most of their created chances came from crosses out wide, whether it be from corners or open play.

Some innovation will be needed from the next manager. Sevilla cannot solely rely on crosses from the flanks to try and get En-Nesyri on the scoresheet. There needs to be more nuance in the final third if they are to pull away from the drop zone.

Work needed all over the pitch

When watching Sevilla this season, one of the most noticeable things that stand out is the sheer volume of isolated tactical and individual mistakes the team make in each game.

From errors in their build-up play to uncoordinated defending in a defensive block to a lack of effort, both the coaching staff and players need to take a large chunk of the blame for the team’s demise this season.

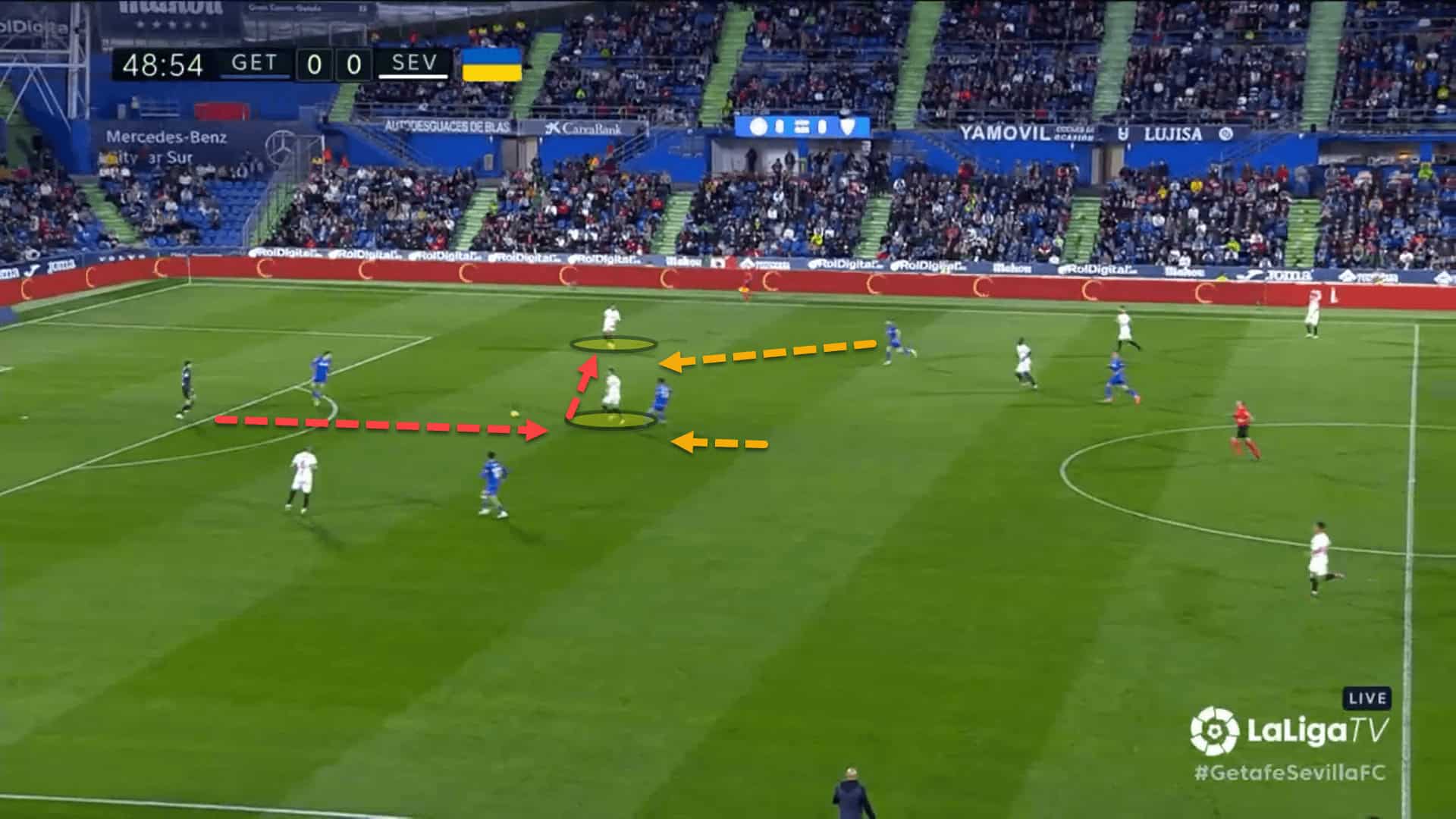

In the recent 2-0 defeat to Getafe, which ultimately cost Sampaoli his job, the game was lost because of a horrific pass made in the build-up phase.

Joan Jordán was under pressure, with the ball coming towards him after a pass from the goalkeeper. The midfielder acted as a wall pass and bounced it out wide – nice and simple. Unfortunately, the weight and accuracy of the pass were miscued.

The nearest Getafe man pounced on the misguided ball. As a result, the right centre-back, Nemanja Gudelj, had to come right across to try and cover the near-post, leaving his man at the back-stick.

As you can probably guess, the cross was driven low and hard to Rafa Mir at the back who tapped it home under no pressure. Sevilla went from being in no danger to being a goal down within seconds.

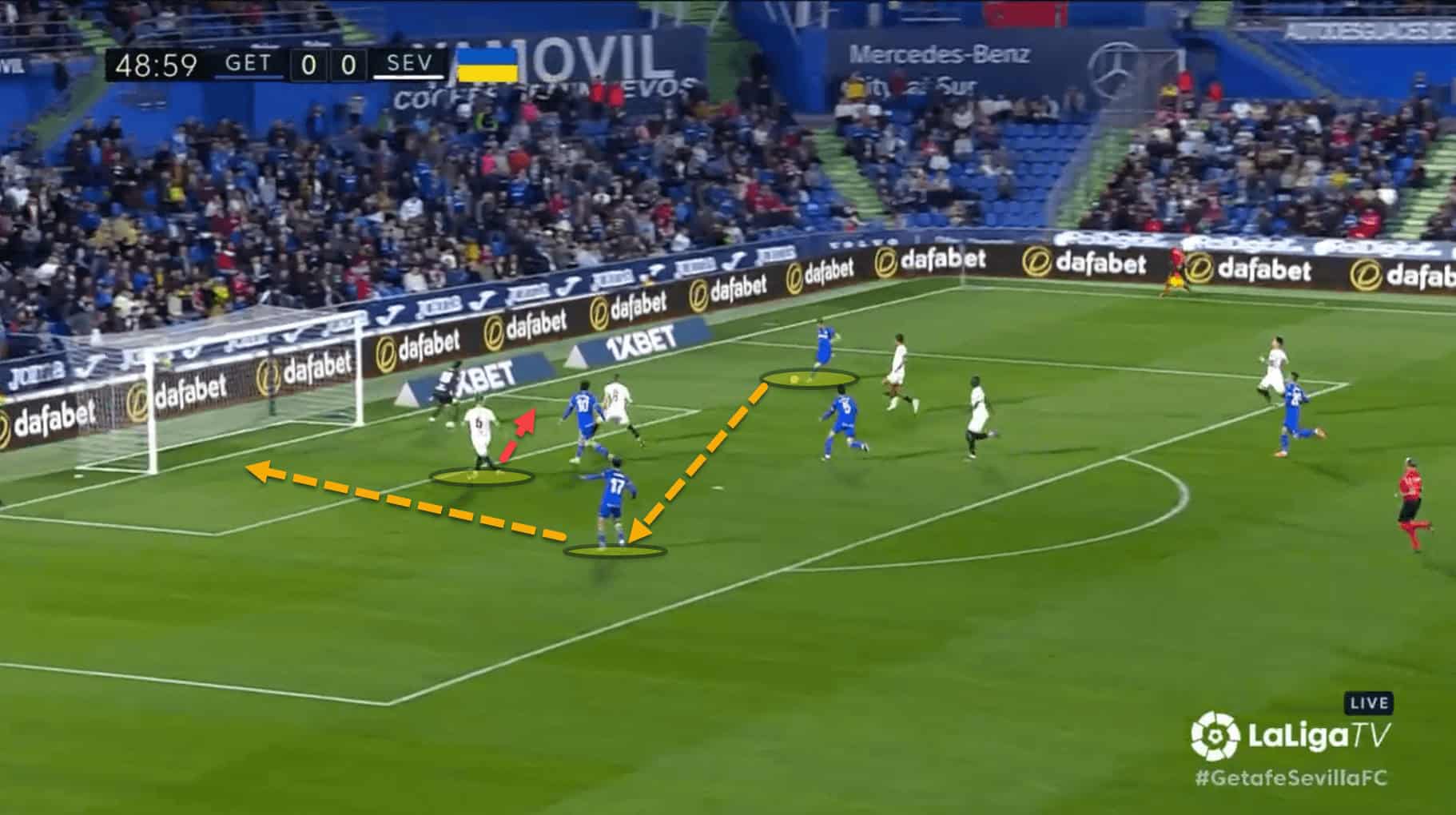

The backline in particular have had serious problems working as a unit this season which has led to many truly unforgivable goals being conceded.

Here, the central centre-back steps out of the backline to follow his man into a deeper area. The two wide defenders don’t squeeze together to close the gap, nor do they drop off to cover the depth.

The ball is slipped into the Almería forward running in behind before eventually being crossed at the back-post where an opposition player pokes home the opening goal within two minutes of play. Like the last goal, the furthest defender is forced to come around to the near-post as a first point of protocol, leaving the back-post free. Then, the goal is scored at the far side.

José Luis Mendilibar

In the aftermath of Sampaoli’s sacking, José Luis Mendilibar has been placed in charge as Sampaoli’s successor at Sevilla. We can expect the Rojiblancos to be far more defensively sound and well-structured, with far less emphasis being placed on principles in possession.

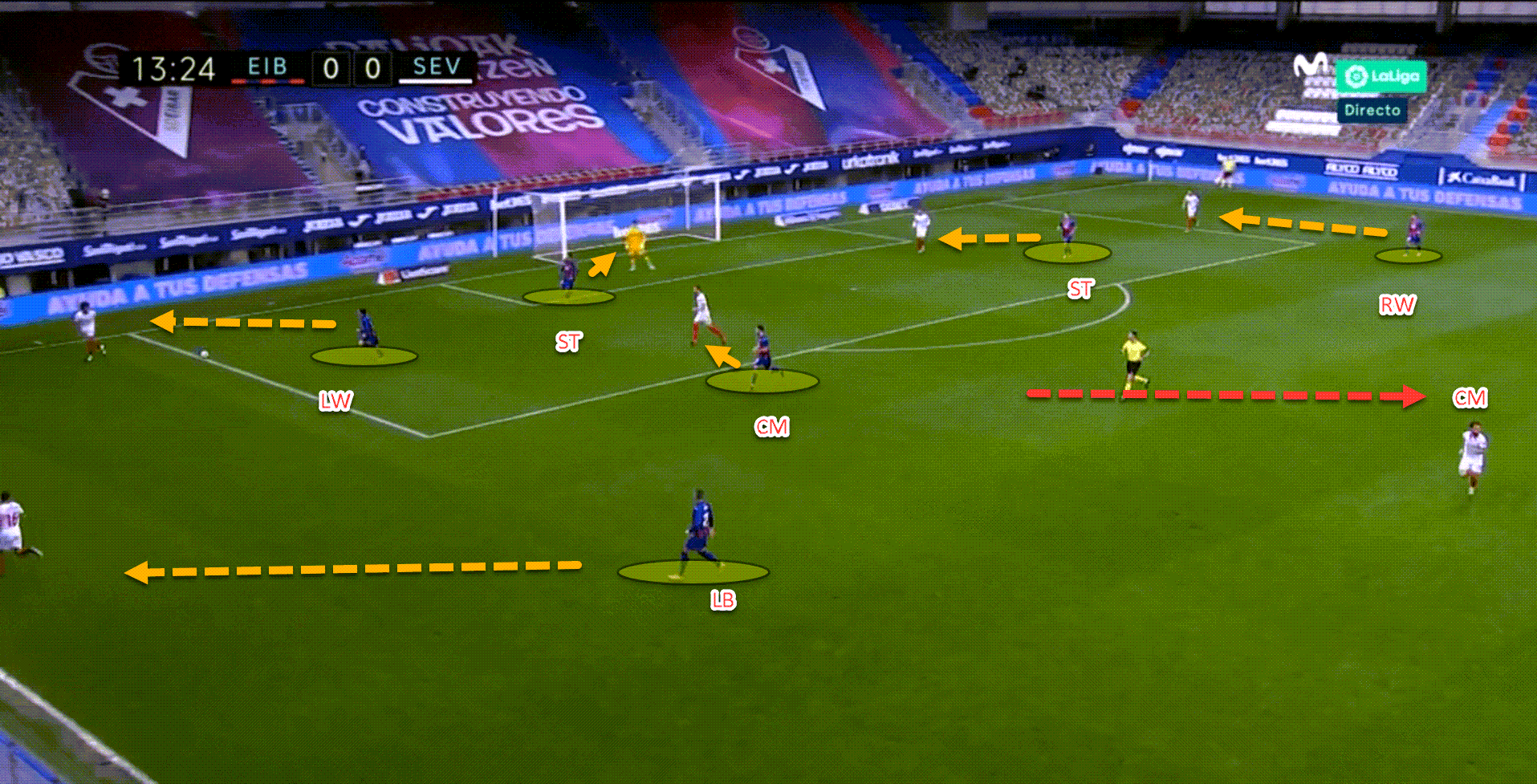

Mendilibar is a keen advocate for direct and high-energy football, particularly out of possession. His Eibar team during the 2020/21 season, despite being relegated, ranked as having the fourth-lowest Passes allowed Per Defensive Action in the top five European leagues with 8.98. Only Leeds United, Real Sociedad and Celta Vigo had fewer, but not by much.

Eibar also boasted the sixth-highest challenge intensity in Europe with 6.7, level with titans Bayern Munich. Challenge intensity measures how many defensive actions a team makes per minute of opposition possession.

Weighing up both these metrics, Eibar were one of the most intense pressing teams in European football

Eibar usually pressed in a 4-4-2 or a 4-1-4-1, using the striker to angle his pressure to force the opposition to play to one side of the pitch while cutting off access to the opposite side. Once this occured, the team ‘locked on’, going man-for-man to try and win the ball back in the final third and so we’ll likely see something similar during Mendilibar’s tenure in Seville.

Conclusion

While Mendilibar’s football may quite substantially different to the team’s previous two managers, his intense style may actually come as a relief to many inside the Ramón Sánchez Pizjuán, moving away from the typical positional play system which has dominated in Andalusia.

At the beginning, this had been the style that the Sevilla board longed so desperately to maintain, having seen its success under Unai Emery, Sampaoli during his first stint and later Lopetegui. However, by the end of Lopetegui’s reign, it was clear that a change in tactical style was needed.

Unfortunately, the board attempted one last throw at the dice with Sampaoli to see if he could reintegrate a more fluid possession-based system which was disastrous to say the least. Now, Mendilibar will be tasked with trying to implement his own style while getting instant results to keep the Spanish club in La Liga within eight weeks.

Who’d be a manager, eh?

Comments