It took Hajduk Split the sacking of two different coaches in a relatively short span of 45 games between Željko Kopić and his successor Zoran Vulić to finally get it right. Or at least so it would seem in a small sample of games the team has played under their new manager, the ex-B team coach Siniša Oreščanin.

Appointed at the end of the year, and having taken part in a total of 11 games so far (and two friendlies), Oreščanin aims to be the breath of fresh air the Croatian titan and the Master of the Sea needs right now. The changes he has implemented in a team that was desperate for some have had an immediate impact, granting Hajduk Split seven wins, only one loss and three draws in his short spell.

This tactical analysis will use statistics to dissect the difference in style that Siniša Oreščanin has brought with his appointment, and how it can translate to a (hopefully) better future for the club.

Overview and key elements

It didn’t take long for the players to start adopting the new boss’ ideas. Right from the get-go, and his very first game in charge, Oreščanin started reshaping the squad’s approach to the beautiful game. The very first change was on paper the simplest one: the preferred system of 4-3-3 was swapped for a more asymmetrical 4-3-1-2, which seems to be the one Siniša Oreščanin likes the most.

Hajduk Split played a total of 42% of all of their games in the 4-3-3 system but in the 11 competitive games Oreščanin has been on the bench, he used 4-3-1-2 a total of 10 times, only opting for a 4-3-3 once against Slaven Belupo in the domestic league campaign.

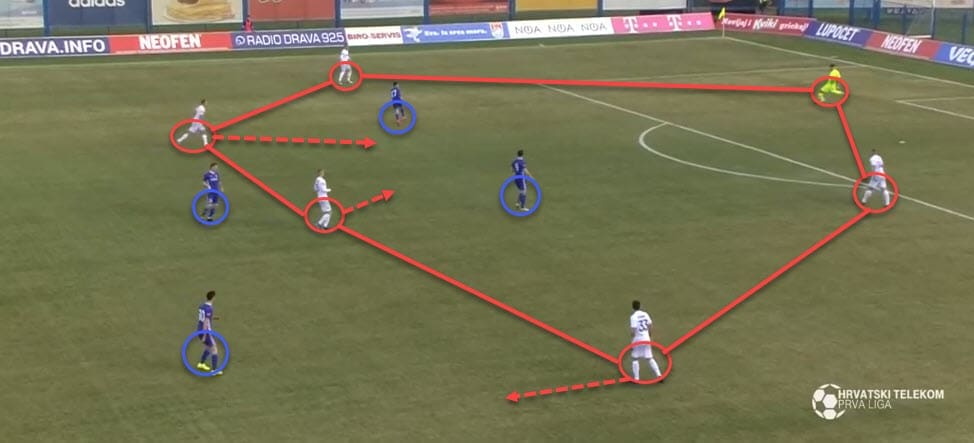

On paper, that should look something like the image above. The full-backs are always positioned high up the pitch. In the attacking phase, the centre-back pairing will set up a high defensive line, and basically, be the only players further back. The two forwards drift to the sides, opening up some space for the attacking midfielder to join the attack, and there is usually one defensive midfielder who connects the thirds, drops deeper and ventures forward depending on the situation.

One other thing Oreščanin successfully implemented in the attacking phase is the slower build-up from the back. Starting with the goalkeeper/centre-back tandem and the dropping midfielder, the full-backs are in an advanced position providing width and a long ball option in behind the defence.

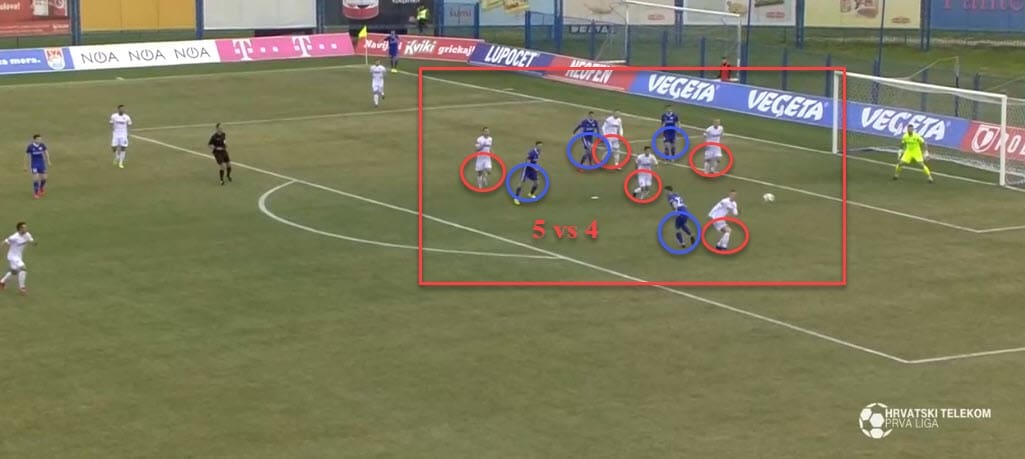

Upon losing the ball, Hajduk Split now aim to get it back as soon as possible by a good pressing technique and creating numerical superiorities even when entering the opponents’ final third. In doing this, they ensure that if the possession is to be retained, the team can immediately transition from defence to attack.

But numerical superiorities are used throughout the pitch and manipulated by smart player movements to create an advantageous position whenever possible. In those scenarios where Hajduk achieve the superiority and provide constant passing channels, they progress the ball through accurate forward passes, often breaking the lines in the process.

When defending, they utilise their high press when activated by special triggers but traditionally defend in a narrow 4-3-3 system. Once again, they focus on good man-marking and overcrowding in order to retain and recycle possession and continue the attack immediately after.

Attacking style of play

Hajduk Split’s attacking style of play has probably seen the biggest changes to its usual schematics as Siniša Oreščanin has completely reinvented the way the team’s attacking outlets work as a whole.

Prior to his mandate, the white team from Split was adamant in taking hold of the ball and keeping it for longer spells of time, but to no avail. This did earn them the most possession in the Croatian domestic league, 1. HNL, with 57% on average. The lack of any palpable results to accompany those possession stats though indicated that, more often than not, they had no idea what to do with the ball.

Both of Oreščanin’s predecessors were sacked due to bad short-term results, and the inability to turn the famed club into a highly competitive one once again. The new coach has taken a page from the books of some internationally proven managers and has implemented a lot of those foreign tactics into his own arsenal.

Building from the back was the first novelty to Hajduk Split’s attacking outlets as the team now regularly sets up a high defensive line, and pins the opposition back, as can be seen in the image above.

There are a couple of things to note in this phase of their attack. The centre-backs are positioned high and are the only ones making the defensive line for Hajduk, while the full-backs are used in a more aggressive manner, providing width higher up the pitch. Usually, one or two midfielders drop deeper to help connect the first and the second thirds.

But in situations when Hajduk Split are pressed and have to retreat all the way back to the goalkeeper, they use their numerical superiorities to create additional passing channels and get the ball forward without necessarily clearing it all the time.

Here, their goalkeeper Josip Posavec participates in the build-up by distributing the ball from the back. This is also a novelty of sorts implemented by Siniša Oreščanin as the club was not known for doing it prior to his appointment.

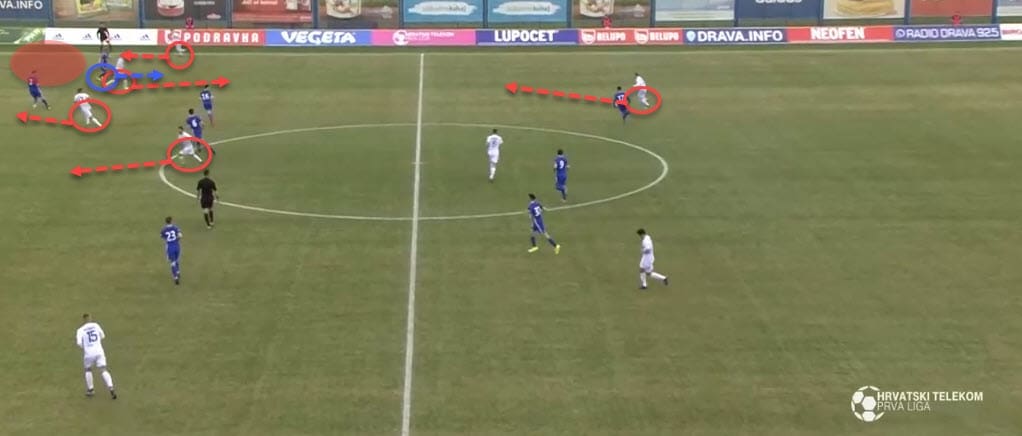

In the example above, which is against Slaven Belupo, Hajduk are pressed and forced to retreat but the opposition cannot follow through with their intentions since they are desperately outnumbered. Notice the difference in personnel and all the options presented to Posavec to distribute the ball.

This was the case throughout the majority of the match as Slaven just couldn’t press well enough to cause some sort of trouble for Hajduk Split. Once again, in the image below, apart from his defenders, the man between the sticks gets additional support from the dropping midfielder who serves as a new passing option, and the press is avoided successfully.

Starting from the back means that Hajduk have to cover a lot of ground before finally entering the final third but the access to it is opened in various ways. One thing that characterises their ability to do so is the tendency to disrupt the opposition ranks.

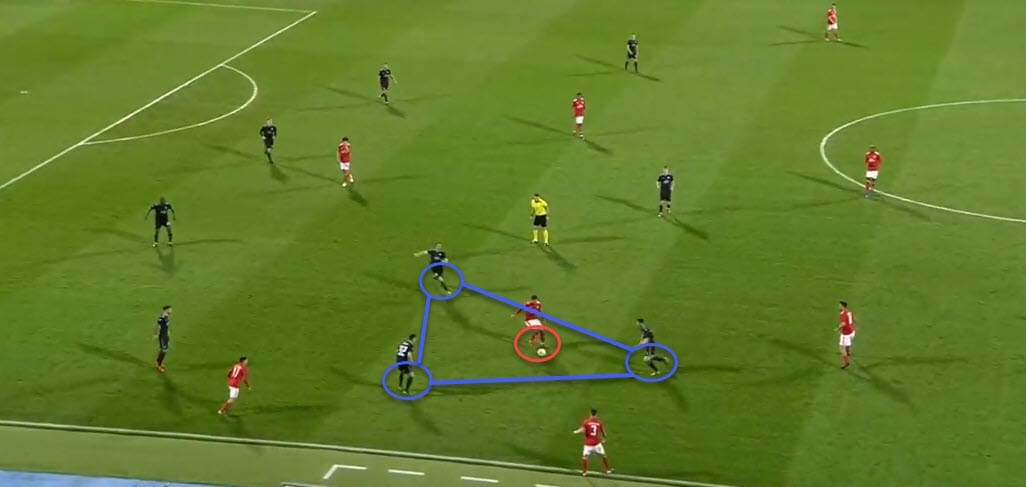

This is done by interchanging positions among their players and constant movement and swapping. Note in the image below how the centre-back carries the ball forward, and as soon as that happens, a series of other events come into fruition.

Firstly, the forward drops deeper, dragging his marker with him and opening some space for the right full-back to exploit, which he does by immediately stepping forward. Furthermore, by occupying that half-space instead of his usual position up front, the forward has given his number 10 a chance to venture higher up the pitch and assume the number nine role.

This constant interchanging dynamic between the players results in a completely disorganised system for the defending team, and it yields a good opportunity for the attackers to exploit. Unfortunately for them, the attack eventually breaks down due to a well-timed tackle by one of Slaven Belupo’s players.

The movement of the forwards plays a huge role in their build-up as it is a primary tool for opening the doors to the final third. Hajduk Split love long balls and they often send those aimed at their strikers, but they do have more elegant ways of reaching them.

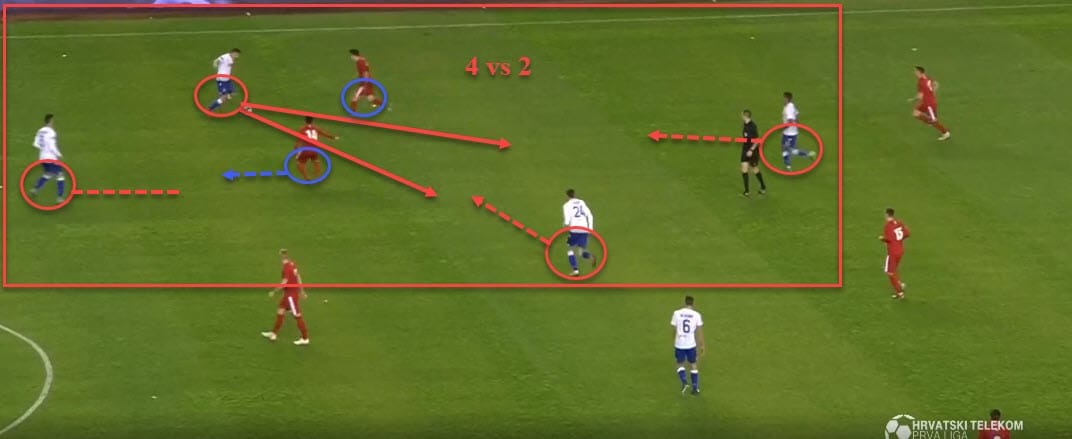

As we have stated before, numerical superiorities play a huge role in Siniša Oreščanin’s system. This is true for almost any situation they find themselves in, whether it’s in the attacking or the defensive phase. In the image above, we see how the movement of the forwards and midfielders creates an advantage for Hajduk Split.

The defenders try to collapse on the ball-carrier but he has multiple options presented to him as it’s a 4v2 situation and a clear-cut advantage for Hajduk’s troops. Entering the final third by bypassing the press with numbers is a highly effective technique if implemented correctly.

In a more default attacking formation, the two forwards will generally assume wider positions, leaving the space for the number 10 to step higher up the pitch, making it three attackers instead of two with the additional support of the overlapping full-backs. In those scenarios the attacking phase may even consist of five men up front, followed by three midfielders and two centre-backs covering their backs, which results in an asymmetrical 2-3-5 formation.

We’ve already stated their preference for long balls. On average, Hajduk Split send a total of 51.29 long balls with 56.8% accuracy. These long passes are usually used for two main purposes: finding their forwards, either when isolated or when running in behind the defensive line, or for quickly swapping sides and continuing the attack.

As Hajduk are often the team with more possession of the ball (59.88% on average), they will set up their defensive line really high up the pitch. The centre-backs will often be the ones distributing the ball forward, either through their dropping midfield connection or via a long ball to the forwards.

But this season, or rather now that Siniša Oreščanin has taken over the team, Hajduk are a squad that invites pressure and then disperses it impressively. In the image below, they have attracted most of the oppositions’ troops onto one side of the pitch, only for them to quickly swap the play to the other side, where their player is completely unmarked.

Defensive style of play

As far as the defensive spectrum goes, Siniša Oreščanin has implemented a couple of key changes there, as well. As a general rule of thumb, Hajduk Split defend in a very narrow 4-3-3 system, once again trying to minimise the area of operation for the opposition and thus achieving numerical superiority.

Since there is a lot of free-roaming movement in their lineup at all times, the formation rarely stays exclusively to what it says on paper. Instead, once the swapping and interchanging among teammates begin, so the system quickly changes.

In general, Hajduk Split won’t always press high up the pitch unless provoked to do so. What I mean by this is that they are happy to contest the long balls distributed by the opposition and winning them through duels, both aerial and on the ground. On average, they win more duels than their opposition with 24.6% – 21.3% ground duels and 46.6% – 43.6% aerial duels won.

However, if they get a chance to press the goalkeeper they will not shy away from it. They will try to force a mistake out of the opposition and get the ball in a dangerous position, or simply make their opponents clear it aimlessly and without much intent and precision.

In those scenarios, the high press is usually very well orchestrated as Hajduk Split try to close all the passing channels rather than rushing the keeper or the back line with numbers.

Numbers, however, do play quite a significant role in their defending phases, as well. Playing in an extremely narrow formation means that there will often be a lot of players in a relatively small area of the pitch. This is done in order to put multiple markers on the ball-carriers and in order to collapse on them with more success.

In the image below, we see how the opposition player is marked by three Hajduk Split players. The opponent making a run behind them is already cut off by the Hajduk player further down the pitch.

This tactic was present in most scenarios throughout the game, whether in trying to retain possession in the middle of the park or simply making sure the ball was cleared from their own box, as can be seen in the example below.

By putting numbers in certain areas of the pitch, Hajduk Split dictate the game and send the opposition where they want them to be, if the plan is executed correctly of course. If the midfield is too crowded, their opponents will try to find the solution down the wings and vice versa.

The main aspect to note here is the importance of the entire team executing their defensive duties. The forwards are often tasked to be the first line of defence by covering the channels to the sides and cutting off the options of progressing to the middle third.

The wide midfielders and the full-backs work closely together to create superiorities on the flanks and provide width to the defence when needed. It’s a fairly successful tactic but also one that requires a lot of focus, and equally importantly, risk-taking.

Weaknesses

It’s safe to say that this new and improved version of Hajduk Split under Siniša Oreščanin has definitely been playing better than before, which is evident in their most recent results. However, that is not to say that they are without weaknesses.

Oreščanin has implemented his strategies which included a big change to the system itself and rarely do we see players adopt those effortlessly and quickly. While this dynamic formation offers a lot of advantages, its main disadvantage is the vulnerability the team has shown in defending their wide areas and depth.

Since the team is often set up in an extremely narrow formation during defensive phases, if the opposition has enough quality to send long balls and switch sides, suddenly Hajduk Split are wide open for a deadly attack.

Their man-marking is usually on point when they surround the opposition and overcrowd them, but if their default setup is breached and they have to start improvising. That often leads to unpleasant situations in which the players themselves are not organised enough to react properly.

This is somewhat a structural flaw but also one that should be amended as times goes by once the players get fully accustomed to their new roles and the new formation Siniša Oreščanin has opted for.

Another problem that seems to be troubling the new coach is the lack of depth in the squad. Some players being irreplaceable is a normal thing in football but lacking the adequate substitute is something the board should assess sooner rather than later. Of course, players like Ante Palaversa or the forward tandem are difficult to replace when unfit or unavailable, but it is nonetheless something the club should make their priority in the foreseeable future.

Hajduk Split have also become dangerous through set pieces but it remains a question whether that was done on purpose or out of necessity. The latter reason can be caused by Hajduk’s inability to breach the low block their opposition often field against them.

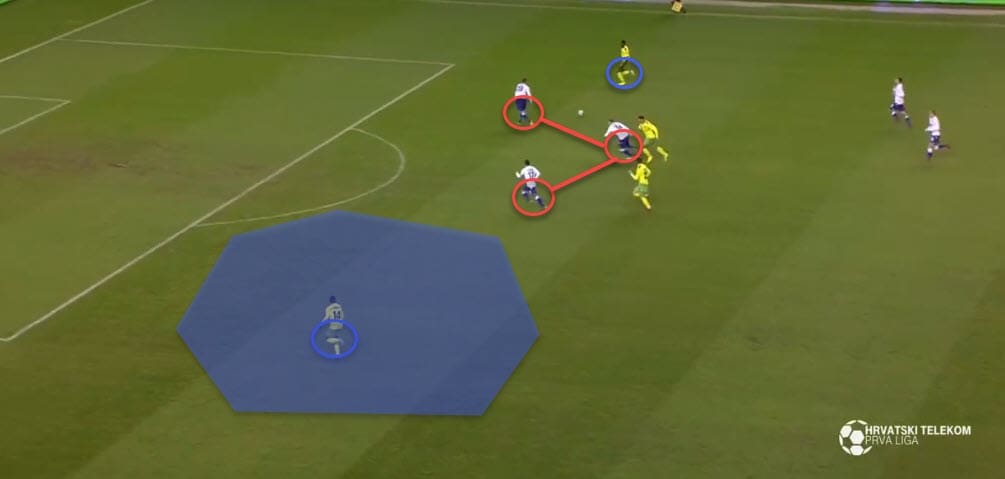

Finally, when the lack of coordination kicks in and the team’s press is bypassed, they are extremely vulnerable to quick transitions against teams that have the ability to send good through-balls and exploit the empty space often left behind.

In the image above, Hajduk piled all their bodies higher up the pitch, and their aggression is punished since no one was there to cover the left side of the pitch. After sending a through-ball into that free space, the opposition easily enter the final third practically unmarked, and without obstruction.

Conclusion

Even though a sample of 11 games is definitely too small to provide us with a clear estimation of the quality this Hajduk Split team under Siniša Oreščanin have, it does serve its purpose in giving us an insight into all the changes the club will face in the near future.

The fact that Oreščanin has managed to do so much in such little time is already a great sign for this titan of Croatian football. Once the players fully accept this new philosophy and a new style of play, their football will become that much better.

Of course, this Hajduk is far from being a finished product. Siniša Oreščanin has barely scratched the surface when it comes to solving the problems his predecessors left him and the team with. Nonetheless, early signs appear to be good; let’s hope they continue in that trend.

If you love tactical analysis, then you’ll love the digital magazines from totalfootballanalysis.com – a guaranteed 100+ pages of pure tactical analysis covering topics from the Premier League, Serie A, La Liga, Bundesliga and many, many more. Buy your copy of the March issue for just ₤4.99 here, or even better sign up for a ₤50 annual membership (12 monthly issues plus the annual review) right here.

Comments